Abstract

This study examined the social impact of being a typical peer model as part of a social skills intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Participants were drawn from a randomized-controlled-treatment trial that examined the effects of targeted interventions on the social networks of 60 elementary-aged children with ASD. Results demonstrated that typical peer models had higher social network centrality, received friendships, friendship quality, and less loneliness than non-peer models. Peer models were also more likely to be connected with children with ASD than non-peer models at baseline and exit. These results suggest that typical peers can be socially connected to children with ASD, as well as other classmates, and maintain a strong and positive role within the classroom.

Keywords: Peer Models, Autism, Social Networks

Despite an increased focus on inclusion in regular education classrooms to improve social functioning (Kasari & Rotheram-Fuller, 2007), children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are often less included in their classroom’s social structure (Chamberlain, Kasari, & Rotheram-Fuller, 2007; Kasari, Locke, Gulsrud, & Rotheram-Fuller, 2011; Rotheram-Fuller, Kasari, Chamberlain, & Locke, 2010). In an effort to improve these social relationships, researchers have employed typical classmates of children with ASD as part of their social skills interventions. Previous research has shown that peer-mediated interventions can effectively increase the social and communication skills of targeted children with ASD (Haring & Breen, 1992; Kamps, Potucek, Lopez, Kravits, & Kemmerer, 1997; Laushey & Heflin, 2000; Pierce & Schreibman, 1997; Sainato, Goldstein, & Strain, 1992); although there are often problems with the generalization of acquired skills to different peers for children with ASD (Laushey & Heflin, 2000) as well as to new contexts (Bellini, et al., 2007). McConnell (2002) suggests that peer mediated approaches are the largest, and best developed group of social interaction interventions for children with ASD. While it appears that using peer models is a promising technique to improve the social inclusion of children with ASD in mainstreamed classrooms (Kasari, Rotheram-Fuller, Locke & Gulsrud, in press), the characteristics of and benefits to peer models for participation in these programs have rarely been explored. Thus, this study had two overarching goals: 1) to examine the characteristics of typically developing peer models of children with ASD; and 2) to examine the changes in the social behavior of typically developing peer models in comparison to a matched cohort of non-peer models.

Inclusion of Children with ASD in Regular Education Classrooms

Although inclusion of children with ASD has often been advocated by parents and professionals because of the exposure to typical peers within the classroom (Kasari, Freeman, Bauminger, & Alkin, 1999; Symes & Humphrey, 2010), there is considerable evidence to suggest that inclusion alone is insufficient to socially include children with ASD into the social networks of their classrooms (Chamberlain, et al., 2007; Kasari & Rotheram-Fuller, 2007; Ochs, Kremer-Sadlik, Solomon, & Sirota, 2001; Ferraioli & Harris, 2011). A large body of literature has examined the peer relationships of children with ASD and has shown some specific social difficulties children with ASD face in school. In particular, researchers have found that children with ASD have fewer friendships, report more loneliness and poorer friendship quality, and are less socially included and accepted into their classroom’s social structure as compared to their typically developing classmates (Bauminger & Kasari, 2000; Chamberlain, et al., 2007; Kasari, et al., 2011). Furthermore, these social discrepancies are exacerbated with increasing grade level (Rotheram-Fuller et al., 2010). Due to these challenges, several interventions have been tested in the school setting to improve the social relationships of children with ASD (Laushey & Heflin, 2000; Bellini, Peters, Benner, & Hopf, 2007; Kasari, et al., in press). One commonly employed strategy to support children with ASD has been enlisting the help of typically developing children or peer buddies/models who provide assistance, instruction, feedback, and reinforcement to children with ASD (Jackson & Campbell, 2009; Bass & Mulick, 2007).

Success of Peer Mediated Approaches

Despite the pervasive socialization deficits in children with ASD and the negative impact that such deficits have on other aspects of children’s development, only preliminary evidence is available regarding the efficacy of psychosocial intervention approaches to remediate children’s social skill sets and peer relationships (Bellini, et al., 2007; Williams-White, Keonig, & Scahill, 2007; Rao, Beidel, & Murray, 2008). A number of promising studies have found that using typical peer models can increase the social and communication skills of children with ASD (Roeyers, 1996; Kamps et al., 1997; Bass & Mulick, 2007; Jung, Sainato, & Davis, 2008; Owen-DeSchryver, Carr, Cale, & Blakeley-Smith, 2008; Kasari, et al., in press). In particular, peer models have been trained to use a) augmentative communication systems (Kamps, et al., 1997); b) pivotal response techniques (Pierce & Schreibman, 1997); c) social interaction initiation and engagement strategies (Kasari, et al., in press); and d) peer buddy systems (Laushey & Heflin, 2000), to name a few. Although many studies have demonstrated that targeted skills can be improved in children with ASD by training typically developing peers, less is known about the specific social characteristics that make children effective peer models and whether these children have positive social outcomes as a result of their role as peer buddy/model.

Selection of Peer Models

Since teachers rarely supervise children during unstructured play times such as recess and lunch, they most often select children as peer models based on their classroom characteristics. These children are generally compliant with adult requests, academically strong, and regular school attendees (Campbell & Marino, 2009). However, Jackson and Campbell (2009) reported that teachers also select peer buddies who are popular, prosocial, and considered self-confident leaders in the classroom. It is evident that children selected to be peer models are considerably different than their non-buddy counterparts in both classroom and social domains. However, the specific qualities that differentiate peer buddies from non-buddies are less clear.

Potential Challenges for Peer Models

Although incorporating typically developing peers has been largely used for increasing social interaction for children with ASD (McConnell, 2002; Jones & Schwartz, 2004), there are some potential challenges that peer models face when selected to help children with ASD. With time, serving as peer models for children with ASD may prove a burden for typically developing children, owing to various difficulties and pressures they experience, which in turn may lead to burnout (Reiter & Vitani, 2007). Field experiences and observations reported by Reiter and Vitani (2007) indicate that over time, typically developing peers, who in early elementary school showed willingness and enthusiasm to include children with ASD, became less willing to do so in later years – these children gradually showed a process of detachment and negative attitudes towards children with ASD (Reiter & Vitani, 2007). Thus, pressure and burnout may pose great challenges for typically developing peer models.

Additionally, the social and academic outcomes for typical peers in classrooms with children with ASD can pose a significant concern to teachers, administrators, and parents (Ferraioli & Harris, 2011). Given the precarious nature of social relationships, there is concern that typically developing peer models will experience negative social consequences as a result of their association and interaction with children with ASD (Ferraioli & Harris, 2011). Since peer modeling programs for children with ASD have shown success in integrating children with ASD, it is important to explore ancillary consequences of these programs on the social outcomes for peer models.

Purpose of the Study

We aimed to expand the existing literature on typically developing peer models by examining: (a) specific and common social characteristics (i.e. social network centrality, friendship reciprocity and connectedness, friendship quality, and loneliness) of children who are most often nominated as peer models and (b) the stability of social behavior of typically developing peer models in comparison to a matched cohort of non-peer models at the end of treatment. Using the abovementioned friendship characteristics as markers for social adeptness, we predicted that peer models will have higher social network status, friendship reciprocity, and quality of friendships, less loneliness, and more connections to both children with ASD as well as other classmates as compared to non-peer models. It is also anticipated that those friendship connections and quality will be stable throughout the intervention, such that peer models will maintain their social success despite participation in the intervention.

Methods

Participants

Participants were drawn from a randomized-controlled treatment trial conducted in 56 classrooms in 30 public schools in a large urban school district that examined the effects of targeted interventions on the peer relationships and social networks of 60 elementary-age children with ASD (Kasari et al., in press). From this study, 107 typically developing children (52 females and 55 males; Mage = 7.92, SD =1.42 years old) were nominated by their teachers to be peer models for children with ASD included in regular first through fifth grade classrooms. An additional 107 typically developing children (57 females and 50 males) were randomly selected using a random numbers generated list and matched on classroom, grade, age and gender, when possible, to be in a comparison group. Matched peers were an average of 7.91 ± 1.40 years old. In three classrooms, more females consented than males and therefore we could not always match by gender.

During the second data collection point (after six weeks of intervention), three peer models had missing data (two students had moved schools and one student had incomplete data), and nine non-peer models had missing data (seven students had moved schools and two students were absent on the day of data collection).

Measures

Friendship Survey

Children were asked to identify who they like to hang out with (friends) and who they do not like to hang out (rejects) in their classrooms. This free recall list of friends determined the child’s number of friendship nominations. From this list, children were instructed to circle their top three friendships and star their best friend. Participating students were asked: “Are there kids in your class who like to hang out together? Who are they?” (Cairns, Cairns, Neckerman, Gest, & Gariepy, 1988). Children listed the names of all children within their classroom who liked to hang around together in groups. Children were reminded to include themselves in groups as well as students of both genders. Young children with reading and writing difficulties were interviewed individually.

Coding Indegrees, Outdegrees, Connects, and Rejects

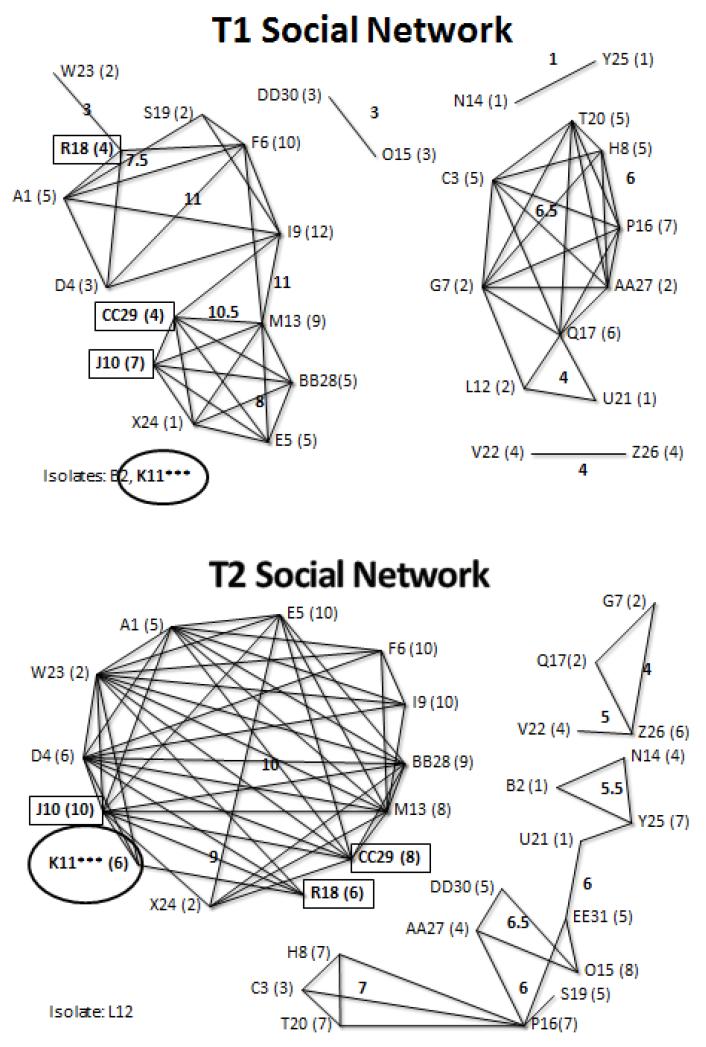

All of the following variables were coded from the Friendship Survey. Indegrees were coded as the total number of received friendship nominations from peers, whereas outdegrees were coded as the total number of outward friendship nominations by the child. Children’s connection scores were coded as the total number of peers that were significantly linked to the child on the social network map. See Figure 1. Lastly, rejections were coded as the total number of times children were identified as someone other children “did not like to hang out with.”

Figure 1. Sample social network map at baseline and exit of a classroom that received the peer-mediated treatment. ID numbers circled and starred denote children with ASD and ID numbers bolded in rectangular boxes denote peer models. The child’s ID is denoted by a letter and a number (i.e. H8), the number in parentheses next to the ID (e.g. H8 (7)) is that child’s individual centrality, and the number inside the clusters are the child’s group centrality (e.g. 7 for child H8).

Coding Friendship Reciprocity

Children were considered to have reciprocal friendships if they selected each other as their top three or best friends within the classroom. A conservative method of determining reciprocal friendships was used, such that when one of the students nominated was absent, or did not complete the measure, it was coded as missing data instead of a non-reciprocated friendship.

Coding Social Network Centrality (Cairns & Cairns, 1994; Kasari, et al., 2011)

Following Cairns and Cairns (1994) a series of social network analyses were conducted in order to obtain each student’s social network centrality score. Social network centrality refers to the prominence of each individual in the overall classroom social structure. Three related scores are calculated in order to determine a student’s level of involvement in the classroom’s social network: 1) the student’s “individual centrality,” 2) the group’s “cluster centrality,” and 3) the student’s “social network centrality.” Using methods developed by Cairns and Cairns (1994), the first two types of centrality are used to determine the third (Cairns, Gariepy, & Kindermann, 1990; Farmer & Farmer, 1996). Based on categorizations by Farmer and Farmer (1996), four levels of SNC are possible: isolated, peripheral, secondary, and nuclear. These four levels of involvement in the classroom’s social structure, ranging from isolated to nuclear, were coded from 0 to 3, to provide a system for describing how well children with ASD are integrated in their informal peer networks.

Friendship Qualities Scale (FQS; Bukowski, Boivin, & Hoza, 1994)

The FQS is a 23-item questionnaire that examines five features of friendship quality: a) companionship, b) help (encompassing both aid and protection from victimization), c) security (including trust and the idea the relationship will transcend specific problems), d) closeness (consisting of both the child’s feelings toward the partner and his or her perceptions of the partner’s feelings), and e) conflict. Children rate how true a sentence description is of one of their friendships (typically the best friendship), using a 5-point Likert scale (1=never to 5=always).

Peer Network Dyadic Loneliness Scale (Hoza, Bukowski, & Beery, 2000)

This 16-item self-report questionnaire assesses individuals’ feelings of dyadic and network loneliness on a scale from 1-4. Eight items focus on individuals’ feelings of dyadic loneliness (e.g. “Some kids hardly ever feel lonely because they have a best friend” but “Other kids wish they had a best friend so they wouldn’t feel so lonely”, etc.) and eight items focus on individuals’ feelings of network loneliness (e.g. “Some kids feel like they really fit in with other kids” but “Other kids don’t feel like they fit in very well with other kids, etc.). Children were asked to circle the sentence that best described them and to place a check mark if the sentence is “sort of true” or “really true.”

Procedure

Once target families completed the informed consent process and met criteria for inclusion in the larger randomized controlled treatment study (see Kasari, et al., in press), research personnel contacted the target child’s school and obtained a letter of agreement to participate from the study. Subsequently, research personnel visited the participant’s classroom at school, and distributed consent forms to all children in the class. Children were informed that their classroom was selected to participate in a research study examining children’s friendships and social skills. Target children with ASD were randomized to four different treatment conditions: target mediated, peer-mediated, both target- and peer-mediated (combined), and control (inclusion only; Kasari, et al., in press). Children who were randomized to the control treatment received one of the three active interventions after the three month follow-up. Thus, participants from this study were selected from the initial peer-mediated and combined treatment conditions as well as the delayed peer-mediated and combined treatment conditions.

The peer-mediated intervention was designed such that three typically developing children from the target child’s classroom were trained to work with children with social difficulties in the class (the child with ASD was not directly identified to protect confidentiality) twice a week for six weeks during recess or lunch periods (See Kasari et al., in press). Specifically, three peer models were taught skills and strategies that would help engage the child with ASD (e.g. initiating a game, building conversation, sustaining engagement, delivering praise, etc.). All three children were taught simultaneously using direct instruction, modeling, role-playing, and rehearsal. Between each session, all three peer models were given “missions” to practice learned skills on the yard with children with ASD or other children from their classrooms. All measures were administered before and after the intervention.

Statistical Analysis

We first report descriptive data characterizing typically developing peer models and non-peer models on the following variables at baseline and exit: social network centrality, classroom connections, friendship nominations (i.e. indegrees, outdegrees, friendship reciprocity, and rejections), friendship quality, and loneliness ratings. Next, we report differences in the aforementioned variables between peer models and non-peer models to determine whether there are differences in those children most often nominated by teachers to be peer models relative to those that are not selected. Lastly, we report differences in perceived relationships with children with ASD between peer models and non-peer models. A one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model was constructed for continuous outcomes to determine whether characteristics of friendship were different between peer models and non-peer models at baseline and exit. In each model, we tested for group (peer models and non-peer models) and grade-related differences. Where ever appropriate (i.e. indegrees, outdegrees, connections, and rejections), we controlled for class size as well. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 17.

Results

Social Network Centrality

Means and standard deviations for all variables from the Friendship Survey for typically developing peer models and non-peer models at baseline and exit are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations for friendship variables for peer models and non-peer models at baseline and exit.

| Baseline | Exit | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer Model | Non-Peer Model | Peer Model | Non-Peer Model | |

| Social Network Centrality | 2.27 (.68)* | 2.06 (.88) | 2.38 (.70)** | 2.01 (.89) |

| Indegrees | 3.53 (1.95)* | 2.92 (1.85) | 3.87 (2.16)** | 3.02 (2.03) |

| Outdegrees | 5.46 (2.78) | 5.10 (2.58) | 5.68 (2.99) | 5.42 (2.51) |

| Reciprocal Friendships (%) | 62.76 (40.62) | 52.71 (41.80) | 60.74 (39.37) | 52.86 (42.19) |

| Received Rejections | 1.08 (1.29) | 1.28 (1.69) | 1.20 (1.36) | 1.58 (1.70) |

| Classroom Connections | 5.09 (4.02) | 4.81 (4.00) | 5.65 (3.82) | 5.25 (3.87) |

| Connections with ASD | .29 (.46)* | .15 (.36) | .32 (.49)* | .19 (.44) |

Note.

p<.05,

p<.01

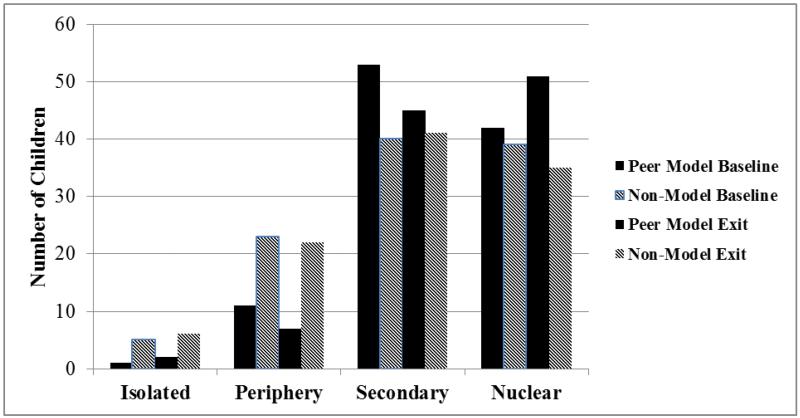

Overall, 88.8% of peer models and 73.8% of non-peer models were secondary or nuclear in their classroom social structure at baseline. These classifications were stable at exit with 89.8% of peer models and 72.1% of non-peer models with secondary or nuclear status. See Figure 2. The ANCOVA indicated that typically developing peer models had significantly higher social network centrality status within their classrooms as compared to non-peer models at baseline, F(1, 211) = 3.99, p = .047 and at exit, F(1, 206) = 11.26, p = .001. Grade was not significant in either model.

Figure 2. Social network centrality classifications for peer models and non-peer models at baseline and exit.

Received Friendship Nominations

Typically developing peer models had significantly more classmates select them as a friend (received friendship nominations, or indegrees) than non-peer models at baseline, F(1, 210) = 5.78, p = .017 and exit, F(1, 205) = 9.83, p = .002 over and above class size F(1, 210) = 5.94, p = .02 and F(1, 205) = 24.08, p = .000. Grade was not significant in either model.

Nominations of Friendships

Despite observed differences in received friendship nominations, typically developing peer models were not significantly different from non-peer models with regard to the number of outward friendship nominations (outdegrees) at baseline, F(1, 208) = .94, p = .33 or exit, F(1, 197) = .48, p = .49 after controlling for grade and class size.

Friendship Reciprocity

Although typically developing peer models had higher mean percentage of reciprocal friendships as compared to non-peer models, these differences were not statistically significant at baseline, F(1, 193) = 2.68, p = .10 or exit, F(1, 185) = 1.72, p = .19.

Rejections

Typically developing peer models were not significantly different from non-peer models with regard to the number of received rejection nominations at baseline, F(1, 210) = .93, p = .34 or exit, F(1, 205) = .65, p = .42.

Classroom Connections

The total number of connections to classmates did not significantly differ between peer models and non-peer models at baseline, F(1, 210) = .23, p = .63 or exit, F(1, 205) = 3.16, p = .08.

Friendship Quality

All children identified a best friend prior to completing the Friendship Qualities Scale. Five domains of friendship quality were examined about each child’s relationship with their best friend, including companionship, help, closeness, security, and conflict. Overall, both groups of children showed stable friendship quality at baseline and exit, although differences between the groups were observed in some domains. See Table 2.

Table 2. Means and standard deviations for friendship quality and loneliness for peer models and non-peer models at baseline and exit.

| Baseline | Exit | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer Model | Non-Peer Model | Peer Model | Non-Peer Model | |

| Friendship Quality | ||||

| Companionship | 15.44 (2.74)*** | 13.73 (3.13) | 15.48 (3.61)** | 13.98 (3.30) |

| Closeness | 22.56 (2.59)** | 20.99 (3.74) | 22.05 (3.86) | 21.60 (3.40) |

| Help | 20.36 (4.11)** | 18.29 (5.00) | 19.69 (5.00)** | 17.57 (5.32) |

| Security | 17.71 (3.46) † | 16.76 (4.18) | 17.81 (3.97) † | 16.71 (4.10) |

| Conflict | 8.73 (3.55) | 8.62 (3.28) | 8.38 (3.49) | 8.40 (3.56) |

| Loneliness | ||||

| Network Loneliness | 14.75 (4.70)* | 16.06 (5.10) | 14.07 (4.45) | 14.97 (4.92) |

| Dyadic Loneliness | 13.68 (4.43)** | 15.87 (4.90) | 14.77 (4.88) | 14.22 (4.94) |

| Total Loneliness | 28.43 (7.73)** | 31.93 (9.05) | 28.84 (8.59) | 29.20 (9.14) |

Note.

p<.01,

p<.001,

= p = .06 - .07

After controlling for grade, typically developing peer models reported significantly higher quality relationships with their best friend than non-peer models in the domains of companionship, F(1, 210) = 18.14, p = .000, help F(1, 210) = 10.89, p = .001, and closeness, F(1, 210) = 12.35, p = .001 at baseline. At exit, peer models were significantly higher in two domains of friendship quality in comparison to non-peer models: companionship, F(1, 194) = 9.13, p = .003 and help, F (1, 195) = 8.31, p = .004. There was a trend toward higher feelings of security at baseline, F(1, 210) = 3.25, p = .07 and at exit, F(1, 195) = 3.65, p = .057 for peer models in comparison to non-peer models. There were no significant differences in conflict for both groups which suggests that peer models and non-peer models reported similar levels of conflict in their best friendships.

Loneliness

Typically developing peer models reported significantly less network, dyadic, and total loneliness than non-peer models at baseline, F(1, 210) = 3.77, p = .05, F(1, 210) = 11.67, p = .001, F(1, 210) = 9.17, p = .003, respectively. However, there were no significant differences in network, dyadic, and total loneliness between typically developing peer models and non-peer models at exit. Typically developing peer models reported relatively low levels of network, dyadic, and total loneliness at baseline and at exit, whereas non-peer models decreased there loneliness at exit. See Table 2.

Connections to Children with ASD

The average number of connections to children with ASD is relatively low for both peer models and non-peer models; however, typically developing peer models were more connected to children with ASD than non-peer models at baseline (29% of peer models, 15% of non-peer models), F(1, 211) = 6.26, p = .013, and exit (32% for peer models, 19% for non-peer models), F(1, 206) = 4.12, p = .04, after controlling for grade.

Peer Models – Within Group Differences

When examining within-group differences between baseline and exit for peer models, we found that the average number of connections to children with ASD increases over time from .21 at baseline to .45 at exit, t(104) = −4.20, p = .000. We also found that children with ASD were more likely to choose a peer model as a friend at exit (.46) as compared to baseline (.33), t (105) = −2.16, p = .016. At baseline, we found that 22 out of 107 peer models selected the child with ASD as a friend (three selected the child with ASD as their best friend, seven selected the child with ASD as a top three best friend, and 12 selected the child with ASD as a friend), 16 peer models rejected the child with ASD, and 69 peer models neither selected nor rejected the child with ASD. On the contrary, 35 out of 107 peer models were selected by children with ASD as a friend (10 as best friends, 15 as top three best friends, and 10 as a friend), peer models were rejected by children with ASD, and 62 peer models were neither selected nor rejected by children with ASD.

At exit, 47 out of 105 peer models selected the child with ASD as a friend (four selected the child with ASD as their best friend, 16 selected the child with ASD as a top three best friend, and 27 selected the child with ASD as a friend), 11 peer models rejected the child with ASD, and 47 peer models neither selected nor rejected the child with ASD. On the contrary, 49 out of 105 peer models were selected by children with ASD as a friend (15 as best friends, 22 as top three best friends, and 12 as a friend), five peer models were rejected by children with ASD, and 53 peer models were neither selected nor rejected by children with ASD. See Table 3.

Table 3. Frequency of friendship nominations by peer models and children with ASD at baseline and exit.

| Baseline | Exit | |

|---|---|---|

| Peer Models | ||

| Selected a Child with ASD as a Friend (%age) | .21 (.41) | .45 (.50) |

| Best Friend | 3 | 4 |

| Top 3 Best Friend | 7 | 16 |

| Friend | 12 | 27 |

| Rejected a Child with ASD | 16 | 11 |

| Neither Selected nor Rejected | 69 | 47 |

|

| ||

| Children with ASD | ||

| Selected a Peer Model as a Friend (%age) | .33(.47) | .46 (.50) |

| Best Friend | 10 | 15 |

| Top 3 Best Friend | 15 | 22 |

| Friend | 10 | 12 |

| Rejected a Peer Model | 10 | 5 |

| Neither Selected nor Rejected | 62 | 53 |

Figure 1 shows an example of a social network map of a child with ASD (denoted K11 and starred and circled in the map) who received the peer-mediated treatment with three typically developing peer models (denoted J10, R18, CC29 in the map). At baseline, child K11 was not nominated by peer- or self-report to any peer group on the Friendship Survey and was thereby coded as “isolated” in her classroom’s social structure. After six weeks of treatment, however, child K11 successfully moved into social clusters with her classmates including J10, R18 (both peer models), W23, and D4 (but not CC29 – the third peer model) and raised her social network centrality status to “secondary.”

Discussion

This study examined the social and relationship characteristics of typically developing children who participated in a peer-mediated intervention for children with ASD in comparison to a matched cohort of typically developing non-peer models. Overall, the results demonstrated that typically-developing peer models were more socially adept and connected to children with ASD than non-peer models at the start and end of the intervention. These findings suggest that there is a specific type of child that is often selected as a peer model, and directly challenges the common notion that there are deleterious social outcomes associated with being a peer buddy/model to a child with ASD.

The results of this study specifically highlight some of the differences in social functioning between children selected as peer models for children with ASD and a matched cohort of non-peer models. While many of the measures utilized pertain to social networking and friendship, these are core constructs that are critical in children’s social development at school. Although peer models and non-peer models were no different on several friendship variables including the number of outward friendship nominations (outdegrees), received rejections, classroom connections, and friendship reciprocity, there were some key differences between the groups that underline potential reasons why certain children are selected as peer models while others are not.

First, typically developing peer models were secondary or nuclear in their social network centrality ratings at both baseline (89%) and exit (91%), which suggests that peer models have stable connections and salience (popularity) within their classroom social structure. Non peer models in the class had significantly lower, but still high levels of connections and popularity in the class, and were also stable in these connections from baseline (74%) to exit (73%). Peer models had significantly higher social network centrality ratings and received more friendship nominations (indegrees) as compared to non-peer models at both baseline and exit. These results suggest that teachers often select students as peer models who are more often socially competent at the beginning of the intervention. These children tended to be more connected to other children in the classroom and were perceived as more “popular”, which may be instrumental in social skills interventions for children with ASD. One study found that in contrast to sociometrically average and rejected children, neglected children reported more negative attitudes toward children with ASD and less willingness to engage with them than popular children (Campbell, Ferguson, Herzinger, Jackson, & Marino, 2005). Using peer models’ with higher social standing may also influence other children’s perceptions of the child with ASD. Children with ASD who are connected to a child with high status within the classroom may increase their own acceptance and social engagement just by affiliation.

Second, peer models had more connections to children with ASD than non-peer models at baseline and at exit. These results suggest that perhaps teachers are also looking for students to be peer models who already have some interest and connection to children with ASD. It may imply that the peer model is one with more empathy or understanding of the child, even before becoming a peer model, or at least more willingness to engage with the child socially when other children may not make that effort.

Peer models also had higher friendship quality in several different categories (at baseline and exit) and reported fewer feelings of loneliness (at baseline only) than non-peer models. These results suggest that the typically developing peers selected to be models for children with ASD appear more self-assured in their feelings regarding relationships with others. Those feelings of security within their peer relationships may offer them reassurance that they can be supportive to other children who may be more rejected (as children with ASD are often more rejected and neglected within the classroom; Church et al., 2000; Kasari, et al, 2011), without losing those strong friendships that they have already formed.

Non-peer models reduced their loneliness over the course of the intervention period, such that there were no differences between peer models and non-peer models in loneliness at the end of treatment. This suggests that while there was little room for peer models to decrease their levels of loneliness, non-peer models did show these reductions as their friendships developed over the course of the six weeks. It is unknown whether this was a result of the intervention, or of naturally occurring relationships, but suggests that all students in the class were feeling more connected to friends at the end of the intervention period, instead of just those who were selected to be peer models at the beginning.

In response to concerns of teachers, administrators, and parents surrounding the social outcomes of typically developing children who act as peer buddies/models for children with ASD (Ferraioli & Harris, 2011), we found that the social status of peer models remains stable and consistently positive over time and does not appear to be affected by participating in a social skills intervention for children with ASD. Although we expected that typically developing peer models may benefit from participating in a peer-mediated intervention, there were no notable social gains for peer models. There are several potential explanations for this finding. First, with regard to children’s self-reports, typically developing peer models were reporting high outdegrees and friendship quality as well as low levels of loneliness prior to participating in the intervention (which remained consistent at the end of intervention). There may not have been enough room to improve as a result of the intervention for these children who were already doing well socially. Similarly, with regard to peer nominations and sociometric ratings, typically developing peer models were receiving high indegrees and social network centrality rankings prior to participating in the intervention (which also remained consistent at the end of intervention). Second, potential intervention gains may not have been adequately captured by the measures used in this study. Many of the intervention modules used with the peer models focused on increasing patience, empathy, prosocial behavior, and understanding of differences, which were not captured in the measures collected. Future studies should consider incorporating these measures to determine whether children gain benefits from serving as peer models for children with ASD.

Limitations

While various sources of information were gathered from children, there were some limitations to this study. First, independent playground observations were not conducted on peer and non-peer models. Observing children during unstructured play periods would provide: a) quantitative and qualitative data on the playground engagement and social/communicative behavior of peer and non-peer models (e.g. what activities they typically engage in, who they engage with, what prosocial skills they demonstrate, etc. and if those behaviors changed over time); b) cross-validation of children’s reports of social network connectivity (e.g. do they indeed “hang out” with children with ASD on the playground as reported on the survey instruments); and c) a basis for selection of peer models (e.g. those with strong playground skills may be ideally suited to act as intervention agents during recess and lunch periods, differences in playground behavior between peer models and non-peer models, etc.). There is some evidence to suggest that despite having a friend children with ASD are often not socially engaged on the playground (Kasari, et al., 2010). Thus, facilitating opportunities between typically developing children and children with ASD on the playground may increase joint and sustained engagement for children with ASD.

There was also no information gathered from teachers on the specific rationale for peer model selection. While commonalities are found among these students in the data collected, teachers’ perspectives in future research should be included to provide a context for future teachers to use in selecting students themselves. This information could suggest underlying characteristics of what makes a ‘good’ peer model, and allow teachers to look for and develop those specific characteristics among their students.

Another limitation to this study involves the lack of follow-up data to examine the stability of children’s social outcomes over time. Although in the randomized controlled treatment trial from which these participants were drawn, data were gathered at a 12-week follow-up period; those data were not available for many of the participants in this study (Kasari, et al., in press). Twenty-four children with ASD switched classrooms or moved to different schools at the 12-week follow-up in the original study, so data were missing for a number of typically-developing peer models and non-peer models. As a result, follow-up analyses were not conducted.

Conclusions

While there is an extensive body of literature examining the efficacy of peer-mediated interventions on targeted outcomes for children with ASD (Bass & Mulick, 2007; Prendeville, Prelock, Unwin, 2005), few studies have examined the characteristics of peer models and whether these children experience negative consequences from participating in treatment programs. Since peer-mediated treatments are currently considered best practice in remediating the social skill sets of children with ASD (Bellini et al., 2007; Williams-White et al., 2007; Rao et al., 2008), a better understanding of children who participate as peer models in these interventions may potentially inform future intervention methodologies and techniques for this population. Future studies that consider the positive impact (or at least lack of negative impact) that children may gain as peer models may help to increase participation from parents of peers in research studies, as well as to simply inform teachers of who might be best to provide support to their peers within the classroom. Given the overwhelming demands within the classroom, having peers look out for one another offers a positive and cost-effective way to increase social interaction and potentially improve social outcomes for all.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH 5-U54-MH-068172 (co-funded by NIMH, NICHD, NINDS, NIDCD, and NIEHS) and HRSA UA3MC11055, clinical trials number NCT00095420. We thank the children, parents, schools and teachers who participated, and the graduate students who contributed countless hours of assessments, intervention, data collection, and coding, Amanda Gulsrud, Laudan Jahromi, Lisa Lee, Eric Ishijima, Kelly Goods, Nancy Huynh, Mark Kretzmann, Tracy Guiou, and Steve Johnson.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: Text revision. 4th ed., rev. Author; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bass JD, Mulick JA. Social play skill enhancement of children with autism using peers and siblings as therapists. Psychology in the Schools Special Issue: Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2007;44:727–735. [Google Scholar]

- Bauminger N, Kasari C. Loneliness and friendship in high-functioning children with autism. Child Development. 2000;71:447–456. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellini S, Peters JK, Benner L, Hopf A. A meta-analysis of school-based social skills interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Remedial and Special Education. 2007;28:153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Hoza B, Boivin M. Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence: The development and psychometric properties of the Friendship Qualities Scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. Special Issue: Children’s Friendships. 1994;11:471–484. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns R, Cairns B. Lifelines and risks: Pathways of youth in our time. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RB, Cairns BD, Neckerman HJ, Gest SD, Gariepy JL. Social networks and aggressive behavior: Peer support or peer rejection? Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:815–823. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RB, Gariépy J-L, Kindermann TA. Identifying social clusters in natural settings. University of North Carolina and Chapel Hill; Chapel Hill, NC: 1990. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JM, Ferguson JE, Herzinger CV, Jackson JN, Marino C. Peers’ attitudes toward autism differ across sociometric groups: An exploratory investigation. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 2005;17:281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JM, Marino CA. Brief report: Sociometric status and behavioral characteristics of peer nominated buddies for a child with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:1359–1363. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0738-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain B, Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E. Involvement or isolation? The social networks of children with autism in regular classrooms. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37:230–242. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer TW, Farmer EMZ. Social relationships of students with exceptionalities in mainstream classrooms: Social networks and homophily. Exceptional Children. 1996;62(5):431–450. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraioli SJ, Harris SL. Effective educational inclusion of students on the autism spectrum. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2011;41:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Haring T, Breen C. A peer mediated social network intervention to enhance the social integration of persons with moderate and severe disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:319–333. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B, Bukowski WM, Beery S. Assessing peer network and dyadic loneliness. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2000;29:119–128. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2901_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JN, Campbell JM. Teachers’ peer buddy selections for children with autism: Social characteristics and relationship with peer nominations. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:269–277. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0623-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CD, Schwartz IS. Siblings, peers, and adults: Differential effects of models for children with autism. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2004;24:187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Jung S, Sainato DM, Davis CA. Using high-probability request sequences to increase social interactions in young children with autism. Journal of Early Intervention. 2008;30:163–187. [Google Scholar]

- Kamps DM, Potucek J, Lopez A, Kravits T, Kemmerer K. The use of peer networks across multiple settings to improve social interaction for students with autism. Journal of Behavioral Education. 1997;7:335–357. [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Freeman SFN, Bauminger N, Alkin MC. Parental perspectives on inclusion: Effects of autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1999;29(4):297–305. doi: 10.1023/a:1022159302571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Locke J, Gulsrud A, Rotheram-Fuller E. Social networks and friendships at school: Comparing children with and without autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2011;41 doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E. Peer Relationships of Children with Autism: Challenges and Interventions. In: Hollander E, Anagnostou E, editors. Clinical Manual for the Treatment of Autism. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; Washington, DC: 2007. pp. 235–257. [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E, Locke J, Gulsrud A. Making the connection: Randomized controlled trial of social skills at school for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02493.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laushey KM, Heflin LJ. Enhancing social skills of kindergarten children with autism through the training of multiple peers as tutors. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30:183–193. doi: 10.1023/a:1005558101038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell SR. Interventions to facilitate social interaction for young children with autism: Review of available research and recommendations for educational intervention and future research. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2002;32:351–372. doi: 10.1023/a:1020537805154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochs E, Kremer-Sadlik, Solomon O, Sirota KG. Inclusion as social practice: views of children with autism. Social Development. 2001;10:399–419. [Google Scholar]

- Owen-DeSchryver JS, Carr ED, Cale SI, Blakeley-Smith A. Promoting social interactions between students with autism spectrum disorders and their peers in inclusive school settings. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2008;23:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce K, Schreibman L. Multiple peer use of pivotal response training social behaviors of classmates with autism: Results from trained and untrained peers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:157–160. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendeville J, Prelock PA, Unwin G. Peer play interventions to support the social competence of children with autism spectrum disorders. Seminars in Speech and Language. 2005;27:32–46. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-932437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao PA, Beidel DC, Murray MJ. Social skills interventions for children with Asperger’s Syndrome or high-functioning autism: A review and recommendations. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38:353–361. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0402-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter S, Vitani T. Inclusion of pupils with autism: The effect of an intervention program on the regular pupils’ burnout, attitudes, and quality of mediation. Autism. 2007;11:321–333. doi: 10.1177/1362361307078130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeyers H. The influence of nonhandicapped peers on the social interactions of children with a pervasive developmental disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1996;26(3):303–320. doi: 10.1007/BF02172476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Fuller E, Kasari C, Chamberlain B, Locke J. Grade related changes in the social inclusion of children with autism in general education classrooms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51(11):1227–1234. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02289.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainato DM, Goldstein H, Strain PS. Effects of self-evaluation on preschool children’s use of social interaction strategies with their classmates with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:127–141. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symes W, Humphrey N. Peer-group indicators of social inclusion among pupils with autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) in mainstream secondary schools: A comparative study. School Psychology International. 2010;31:478–494. [Google Scholar]

- Williams-White S, Keonig K, Scahill L. Social skills development in children with autism spectrum disorders: A review of the intervention research. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37:1858–1868. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0320-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]