Abstract

AIM: To describe a population of outpatients in China infected by hepatitis B virus (HBV) and/or hepatitis C virus (HCV), and assess their current management status.

METHODS: A multicenter, cross-sectional study of HBV- and/or HCV-infected patients was conducted from August to November, 2011 in western China. Patients ≥ 18 years of age with HBV and/or HCV infections who visited outpatient departments at 10 hospitals were evaluated, whether treated or not. Data were collected on the day of visit from medical records and patient interviews.

RESULTS: A total 4010 outpatients were analyzed, including 2562 HBV-infected and 1406 HCV-infected and 42 HBV/HCV co-infected patients. The median duration of documented infection was 7.5 years in HBV-infected and 1.8 years in HCV-infected patients. Cirrhosis was the most frequent hepatic complication (12.2%), appearing in one-third of patients within 3 years prior to or at diagnosis. The HCV genotype was determined in only 10% of HCV-infected patients. Biopsy data were only available for 54 patients (1.3%). Antiviral medications had been received by 58.2% of patients with HBV infection and 66.6% with HCV infection. Nucleos(t)ide analogs were the major antiviral medications prescribed for HBV-infected patients (most commonly adefovir dipivoxil and lamivudine). Ribavirin + pegylated interferon was prescribed for two-thirds of HCV-infected patients. In the previous 12 mo, around one-fifth patients had been hospitalized due to HBV or HCV infection.

CONCLUSION: This observational, real-life study has identified some gaps between clinical practice and guideline recommendations in China. To achieve better health outcomes, several improvements, such as disease monitoring and optimizing antiviral regimens, should be made to improve disease management.

Keywords: Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, Clinical characteristics, Treatment

Core tip: This observational, real-life study has identified some gaps between current clinical practice and guideline recommendations for the treatment of hepatitis B and C infections in China. To achieve better health outcomes, the findings of the study point to various improvements that need to be made to align clinical practice more closely with treatment guidelines, including: (1) routine screening for infections so that patients are diagnosed earlier; (2) more thorough evaluation of hepatitis B virus (HBV)/hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected patients; and (3) the use of more effective antiviral agents for both anti-HBV and anti-HCV therapy and adjustment of the treatments according to the response.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B and hepatitis C caused by infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), respectively, remain serious health problems worldwide, affecting around 2 billion people globally in the case of HBV and 130-170 million in the case of HCV[1-3]. HBV infection is potentially life-threatening and is the more serious type[1,4]. An estimated 600000 people die each year due to the acute or chronic consequences of this infection[1,5,6]. In China, hepatitis B is one of the top 3 infectious diseases reported by the Ministry of Health[7], and about 30 million people are chronically infected with HBV[8]. Every year, around 300000 people die from HBV-related diseases in China, which accounts for 40%-50% of the total HBV-related deaths worldwide[9,10].

The burden of HCV infection is also significant in China. In 1992, a nationwide survey estimated the prevalence of HCV infection in China at 3.2%[11]. Following acquisition of HCV, chronic infection develops in 75%-85% of infected individuals. Cirrhosis develops in up to 20% of those with chronic infections, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) develops in 3%-4% of people with HCV-associated cirrhosis each year[12-14].

In view of the serious socioeconomic consequences of HBV and HCV infection, identifying patient characteristics and current treatment practice for these diseases will enhance regulation of their medical management. The present study was designed to provide real-life data on HBV/HCV infection in China in an effort to improve the quality of treatment and public health practice in controlling the diseases. As there are no data on the management of HBV/HCV infections in routine clinical practice in China, the objective of the study was to understand the characteristics of patients with these infections and the current treatment regimens employed, in order to identify gaps between current clinical practice and guideline recommendations[15-19].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We undertook an observational, cross-sectional, epidemiological study at the outpatient departments of 10 hospitals in western China during the period 15 August, 2011 to 22 November, 2011. Patients with HBV and/or HCV infection who visited outpatient hepatitis departments or infectious disease physicians at the 10 participating hospitals during the study period were evaluated, whether they were currently receiving treatment or not. The study was performed in compliance with the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) guideline on Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practice. Approval for the study was provided by either a Central Ethics Committee (Tangdu Hospital) or Ethics Committees at the hospitals where the study was performed, according to local hospital policies. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients.

Patients

Male or female patients who were ≥ 18 years of age and had documented hepatitis B and/or hepatitis C infection were eligible for inclusion in the study. Hepatitis B infection was defined as a positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) test, while hepatitis C infection was defined as a positive anti-HCV antibody test and HCV RNA test result above the limit of detection when the infection was diagnosed. Exclusion criteria included pending, inconclusive or unknown HBV or HCV test results, previous antiviral treatments for hepatitis B and/or hepatitis C that terminated > 12 mo previously, and hepatitis infection considered by the investigator as cured.

Study procedures

Investigators screened HBV/HCV outpatients continuously in their routine consultation activities at each site and enrolled eligible HBV- or HCV-infected patients. The investigators were required to complete a case report form (CRF) during the outpatient visit. Data collected from the CRFs included demographic information, vaccination history, comorbidities, diagnosis of HBV/HCV infection, concomitant infections, the most recent laboratory tests and results, the presence of hepatic complications, previous and current antiviral treatments, and other/alternative treatments taken.

As patients with HCV infection are much fewer in number than those with HBV infection, to achieve sufficient HCV patients for analysis, the investigators were requested to ensure that about one-third of the total population enrolled were HCV-infected. A total of 8361 outpatients with either HBV or HCV infection were screened for inclusion in the study, 78.0% (6524/8361) of whom had HBV infection, 21.4% (1789/8361) had HCV infection, and 0.6% (48/8361) had both. Of these, 4010 patients were enrolled in the study, including 2562 with HBV infection and 1406 with HCV infection and 42 with HBV and HCV co-infection.

Statistical analysis

Data were displayed descriptively for each patient group. Continuous variables were described as numbers, medians, minimum and maximum values, and means ± SD. Categorical variables were described as numbers and percentages for each modality. Two-sided 95%CI were calculated for prevalence data.

Data monitoring and analysis, including confirmation of eligibility and adherence to the study protocol, were conducted by an independent contract research organization and approved by the principal investigator.

RESULTS

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics of the hepatitis virus infections

A total of 4010 patients (mean age, 41.4 years; range, 18-89 years) who met the inclusion/exclusion criteria and agreed to participate were enrolled in the study (Table 1). HBV infection (without HCV) was present in 2562 patients (63.9%), HCV infection (without HBV) in 1406 (35.1%), and co-infection with both HBV and HCV in 42 (1.0%). One HBV-infected patient (0.02%) had hepatitis D virus co-infection, and 8 (0.2%) were human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive, 7 of whom had HCV infection and 1 HBV infection.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the analyzed patient population with hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus infections n (%)

| Characteristic | HBV (n = 2562) | HCV (n = 1406) | HBV and HCV (n = 42) | All patients (n = 4010)1 |

| Age, yr (mean ± SD) | 38.3 (± 12.4) | 46.9 (± 13.6) | 45.5 (± 11.4) | 41.4 (± 13.5) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1696 (66.2) | 652 (46.4) | 22 (52.4) | 2370 (59.1) |

| Female | 866 (33.8) | 754 (53.6) | 20 (47.6) | 1640 (40.9) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Han | 2431(94.9) | 1205 (85.7) | 37 (88.1) | 3673 (91.6) |

| Urghur | 26 (1.0) | 126 (9.0) | 2 (4.8) | 154 (3.8) |

| Hui | 46 (1.8) | 27 (1.9) | 2 (4.8) | 75 (1.9) |

| Other | 59 (2.3) | 48 (3.4) | 1 (2.4) | 108 (2.7) |

| Domicility | ||||

| Urban/suburban | 1831 (71.5) | 1212 (86.2) | 33 (78.6) | 3076 (76.7) |

| Rural | 731(28.5) | 194 (13.8) | 9 (21.4) | 934 (23.3) |

| Alcohol consumption | 78 (3.5) | 38 (2.7) | 0 | 116 (2.9) |

| Medical complications | 331 (12.9) | 394 (28.0) | 12 (28.6) | 737 (18.4) |

| Diabetes | 40 (1.6) | 97 (6.9) | 2 (4.8) | 139 (3.5) |

| Liver gallstones | 70 (2.7) | 50 (3.6) | 1 (2.4) | 121 (3.0) |

| Alcoholic liver disease | 41 (1.6) | 26 (1.8) | 1 (2.4) | 68 (1.7) |

| Respiratory disease | 24 (0.9) | 26 (1.8) | 3 (7.1) | 53 (1.3) |

| Coronary artery disease | 10 (0.4) | 40 (2.8) | 1 (2.4) | 51 (1.3) |

| Hepatic complications2 | ||||

| Hepatic cirrhosis | 302 (11.8) | 180 (12.8) | 9 (21.4) | 491 (12.2) |

| Jaundice | 178 (7.0) | 66 (4.7) | 4 (9.5) | 248 (6.2) |

| Ascites | 94 (3.7) | 46 (3.3) | 2 (4.8) | 142 (3.5) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 27 (1.1) | 15 (1.1) | 2 (4.8) | 44 (1.1) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 11 (0.4) | 13 (0.9) | 1 (2.4) | 25 (0.6) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 4 (0.2) | 11 (0.8) | 1 (2.4) | 16 (0.4) |

| HBV vaccination status | ||||

| Never | 2009 (78.4) | 743 (52.8) | 26 (61.9) | 2778 (69.3) |

| Childhood | 122 (4.8) | 136 (9.7) | 3 (7.1) | 261 (6.5) |

| Adult | 43 (1.7) | 149 (10.6) | 0 | 192 (4.8) |

| Unknown | 388 (15.2) | 378 (26.9) | 13 (31.0) | 779 (19.4) |

| Pregnant | 146 (5.7)3 | 47 (3.3) | 2 (4.8) | 195 (4.9) |

One patient had HDV infection;

Includes previous complications (3 years prior to at diagnosis) and complications occurring after diagnosis;

Number includes 1 patient of unknown pregnancy status.

Patients with HCV infection tended to be slightly older than those with HBV infection (mean, 46.9 vs 38.3 years) and were more commonly female (53.6% vs 33.8%) (Table 1). The majority of patients were of Han ethnicity (91.6%), and most lived in urban or suburban areas (76.7%). The proportion who were of Urghur ethnicity was much higher in patients with HCV infection than in those with HBV infection (9.0% vs 1.0%, respectively). Medical complications were present in 18.4% of the total population. The patients’ vaccination histories indicated that 165 (6.4%) HBV-infected patients had received HBV vaccination, most commonly in childhood (Table 1).

The median duration of documented HBV infection was 7.5 years [range, 0-46.6 years; interquartile range (IQR), 2.7-13.8 years], which was longer than that of documented HCV infection, which was 1.8 years (range, 0-28.7 years; IQR, 6.3 mo to 4.8 years). Although around 75% of the patients had medical insurance, 87% self-paid to cover outpatient treatment costs.

Potential routes of infection and hepatic complications

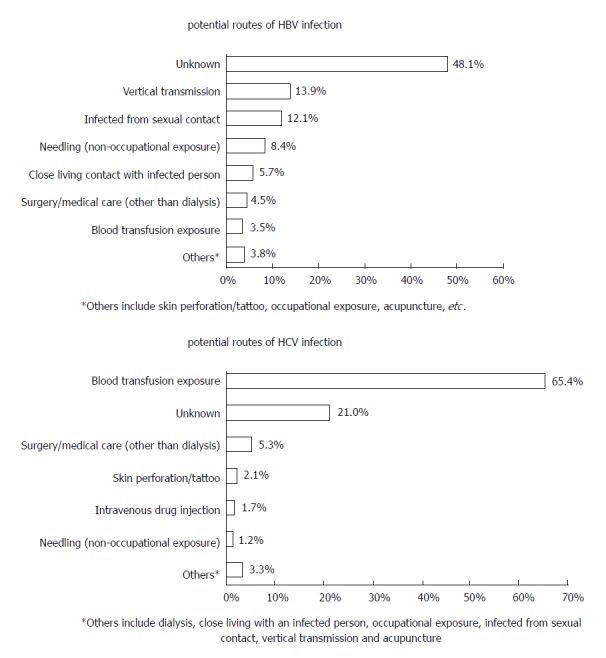

In response to questioning regarding the most likely route of acquiring the infection, 1231 HBV-infected patients (48.1%) and 295 HCV-infected patients (21.0%) were unable to answer this question. Among patients who did answer, blood transfusion/exposure was the most likely route of infection in HCV-infected patients (65.4%), while in HBV-infected patients, vertical transmission and infection from a family or sexual contact were the most likely routes of infection (13.9% and 12.1%, respectively) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Most likely routes of hepatitis B virus/hepatitis C virus infection in the analyzed patient population (n = 4010).

Cirrhosis was the most frequent hepatic complication, presenting in 12.2% of patients overall, one-third of them within 3 years prior to or at diagnosis. Cirrhosis was slightly more common in patients with HCV infection than in those with HBV infection (12.8% vs 11.8%, respectively). HCC and hepatic encephalopathy were detected in 0.6% and 0.4% of patients overall (Table 1).

Laboratory assessments

Results of the most recent laboratory tests in the study population indicated that HBeAg and HBeAb were positive in 45.5% and 50.4% of HBV-infected patients with test records, respectively (Table 2); the median time from performance of these tests to the index outpatient visit was 0.5 mo (IQR, 0-4.1). More than half of the patients (55.9%) had positive HBV DNA test results in the most recent tests.

Table 2.

Laboratory assessments and anti-hepatitis B virus treatments administered to patients with hepatitis B virus infection, and the responses to treatment n (%)

| HBV (n = 2562) | HBV and HCV (n = 42) | |

| Laboratory assessments: | ||

| HBsAg positive1 | 2195/2207 (99.5) | 32/35 (91.4) |

| HBeAg positive1 | 971/2137 (45.4) | 5/34 (14.7) |

| HBeAb positive1 | 1056/2092 (50.4) | 26/32 (81.3) |

| HBV DNA positive1 | 1278/2286 (55.9) | 313/38 (34.2) |

| ALT abnormal | 944 (36.8) | 19 (45.2) |

| AST abnormal | 740 (28.9) | 16 (38.1) |

| AFP abnormal | 142/866 (16.3) | 4/22 (18.2) |

| Received antiviral treatment | 1490 (58.2) | 22 (52.4) |

| Latest antiviral therapies | (n = 1490) | (n = 22) |

| Interferon (IFN) | 109 (7.3) | 2 (9.1) |

| PEG-IFN | 99 (6.6) | 14 (63.6) |

| Lamivudine | 467 (31.3) | 4 (18.2) |

| Telbivudine | 238 (16.0) | 1 (4.5) |

| Adefovir dipivoxil | 691 (46.4) | 4 (18.2) |

| Entecavir | 230 (15.4) | 2 (9.1) |

| Duration of completed treatment, months, median (IQR) | (n = 1309) | (n = 21) |

| 11.2 (0-187.8) | 7.8 (0.6-69.6) | |

| Responses to treatment | (n = 801) | (n = 12) |

| Virological response2 | 645 (80.5) | 11 (91.7) |

| Biochemical response3 | 465 (58.1) | 5 (41.7) |

| Serological response4 | 105 (13.1) | 2 (16.7) |

| Treatment status5 | ||

| Sustained response6 | 5/38 (13.2) | 0 |

| Virological breakthrough | 20/801 (2.5) | 0 |

Patients with records from the most recent tests;

Includes HBV DNA not detected or below lower limit of detection, or HBV DNA decreased by ≥ log10 IU/mL vs baseline;

ALT and AST returned to normal;

Includes HBeAg negative or seroconversion and HBsAg negative or seroconversion;

Excludes patients in whom treatment was terminated and patients not yet evaluated due to ongoing treatment;

Sustained response: patients who achieved and had a sustained response for at least 6 mo after completing therapy. AFP: α-Fetoprotein; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; HBeAb: Hepatitis B e antibody; HBeAg: Hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; IQR: Interquartile range; NA: Nucleos(t)ide analog; PEG-IFN: Pegylated interferon.

In patients with HCV infections, the most recent HCV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test results were positive in 99.3% (1366/1375) (Table 3), and the median time from this test to the study visit was 1.3 mo. Liver function tests [alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST)] were abnormal in one-third of HBV- or HCV-infected patients, the proportions being slightly higher in patients with HCV infection and highest in patients with HBV/HCV co-infection (Tables 2 and 3). Around 30% of patients had never had an α-fetoprotein (AFP) test. Among those who did, the AFP result was abnormal in 16.9% of patients (232/1374) overall (16.3%, 17.7% and 18.2% in patients with HBV infection, HCV infection, and HBV/HCV co-infection, respectively) (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 3.

Laboratory assessments and anti-hepatitis C virus treatments administered to patients with hepatitis C virus infection, and the responses to treatment n (%)

| HCV (n = 1406) | HCV and HBV (n = 42) | |

| Laboratory assessments: | ||

| HCV PCR positive1 | 1366/1375 (99.3) | 38/40 (95.0) |

| ALT abnormal2 | 575 (40.9) | |

| AST abnormal2 | 499 (35.5) | |

| AFP abnormal | 86/486 (17.7) | |

| Received antiviral treatment | 936 (66.6) | 22 (52.4) |

| Number of treatments | (n = 936) | (n = 23) |

| First | 751 (80.2) | 20 (87.0) |

| Second | 140 (15.0) | 3 (13.0) |

| Third | 45 (4.8) | 0 |

| Antiviral agents used in first-time antiviral treatments | (n = 750) | (n = 20) |

| Interferon (IFN) | 232 (30.9) | 5 (25.0) |

| PEG-IFN | 514 (68.5) | 15 (75.0) |

| Ribavirin | 702 (93.6) | 15 (75.0) |

| Duration of completed treatment, months (median, range) | (n = 277) | (n = 3) |

| 11.8 (0.1-139) | 11.9 (5-11.9) | |

| Responses to treatment3 | ||

| Quick response4 | 125/425 (29.4) | 4/10 (40.0) |

| Early response5 | 126/349 (36.1) | 2/6 (33.3) |

| Response at end of treatment6 | 38/276 (13.8) | 2/5 (40.0) |

| Sustained response7 | 24/121 (19.8) | 0 |

| No response | 20/276 (7.2) | 0 |

Results were unknown or unchecked for 2.2% of patients;

Results were unknown or unchecked for 10.8%-18.4% of patients;

Excludes patients in whom treatment was terminated early and patients not yet assessed due to ongoing treatment;

Quick response (HCV RNA negative on PCR after 4 wk of treatment): calculated in patients who had received at least 4 wk therapy;

Early response (HCV RNA negative on PCR negative or decreased by ≥ 2 log10 (IU/mL) after 12 wk of treatment): calculated in patients who had received at least 12 wk therapy;

Response rate at end of treatment: the proportion of the patients who had received at least 24 wk therapy achieved response;

Sustained response: patients who had a sustained response for at least 24 wk after completing therapy. AFP: α-Fetoprotein; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction; PEG-IFN: Pegylated interferon.

Genotyping

HBV DNA typing was performed in 46 HBV-infected patients (1.8%), 26 of whom (56.5%) demonstrated type B, 18 (39.1%) type C, and 2 (4.3%) type G. In HCV-infected patients, the HCV genotype was determined in 144 (10.2%), 82 of whom (56.9%) demonstrated type 1, 30 (20.8%) type 2, 20 (13.9%) type 3, and 12 (8.3%) type 6.

Ultrasound, biopsy and fibrosis assessments

Ultrasound assessments were performed relatively frequently in both HBV- and HCV-infected patients (43.1% of patients overall). Liver cancer was suspected or detected in 39 of the 1729 patients who underwent ultrasound assessments (2.3%). Slightly higher proportions of patients with HCV infection and HBV/HCV co-infection had evidence of liver cancer in comparison with patients with HBV infection (3.0% and 7.1% vs 1.9%, respectively).

Biopsy data were only available for 54 patients (1.3% of the study population), including 47 HBV-infected patients, 6 HCV-infected patients, and 1 with HBV/HCV co-infection. Non-invasive methods for assessing liver fibrosis, principally Fibroscan®, were employed in 13.3% of patients (534/4010).

Treatments administered and responses

Anti-HBV treatments (Table 2): At the time of the study visit, slightly over half of the patients with HBV infection (1490; 58.2%) had previously received antiviral treatments; 80.5% (1199/1490) of these patients had only ever received nucleos(t)ide analogs (NAs), while 19.5% (291/1490) had received interferon (IFN) regimens (including pegylated interferon [PEG-IFN]) or IFN + NA therapy. More than half of the treated patients had received adefovir dipivoxil (52.3%; 780/1490), while 40.1% (598/1490) had received lamivudine.

Analysis of the most recent (176; 11.8%) or ongoing (1314; 88.2%) antiviral treatments received indicated that 86.1% (1283/1490) of those who had been prescribed anti-HBV therapy were receiving NA monotherapy, 8.9% (132) were receiving IFN monotherapy, and 5.0% (75) were receiving IFN and NA combination therapy. The most commonly used NAs were adefovir dipivoxil (46.4%) and lamivudine (31.3%) (Table 2). The median duration of treatment in 161 patients who had completed their antiviral treatment was 1 year (range, 0-8 years).

Of the 1380 patients who were prescribed anti-HBV medications at the index outpatient visit, 88.6% (n = 1222) continued on their present treatments without modification, 3.3% (n = 45) had dosage or medication changes, and 8.2% (n = 113) had anti-HBV treatment prescribed for the first time at this visit.

Treatment responses were evaluable in 801 HBV-infected patients (53.8%) who received antiviral treatment. A virological response [HBV DNA undetectable or decreased by ≥ log10 (IU/mL) vs baseline] was achieved in 80.5% of these patients, a biochemical response (AST and ALT levels returned to normal) in 58.1%, and a serological response (HBeAg or HBsAg negative or seroconversion) in 13.1%. A sustained virological response was noted in only 5 of 38 patients (13.2%) who were followed for at least 6 mo after completing therapy, while relapse of HBV infection occurred in 11 of 73 patients (15.1%) who had completed treatment and were evaluated, failure of primary treatment occurred in 8 of 542 patients (1.5%) who had received antiviral therapy for at least 6 mo, and virological breakthrough occurred in 20 of 801 patients who were evaluated (2.5%).

Anti-HCV treatments (Table 3): Two-thirds of the patients with HCV infection (n = 936; 66.6%) had previously received anti-HCV therapy, the majority of whom (n = 751; 80.2%) had received 1 course of antiviral therapy, while 140 (15.0%) had received 2 courses, and 45 (4.8%) had received 3 courses. The most commonly prescribed anti-HCV agents were ribavirin + PEG-IFN or ribavirin + conventional IFN. Ribavirin + PEG-IFN was prescribed for 66.4% (498/750), 70.7% (99/140), and 73.3% (33/45) of patients for the first, second, and third treatment courses, respectively, and conventional IFN was prescribed for 30.9% (232/750), 28.6% (40/140), and 20.0% (9/45) of patients for the first, second, and third treatment courses, respectively. In patients who had completed their antiviral treatment (n = 277), the median duration of treatment was 1 year (range, 0-11.6 years).

Among 674 patients who were prescribed anti-HCV medications at the index outpatient visit, 86.5% (n = 583) continued on their present treatment without modification, 4.2% (n = 28) had dosage or medication changes, and 4.5% (n = 63) had anti-HCV treatment prescribed for the first time at this visit.

Among evaluable patients, 29.4% demonstrated a quick response (HCV RNA negative on PCR after 4 wk of therapy), 36.1% had an early response [HCV RNA negative on PCR or decreased by ≥ 2 log10 (IU/mL) after 12 wk], and 19.8% had a sustained response after 24 wk (Table 3). However, 7.2% of patients had no response.

Other treatments

Traditional Chinese herbal medicines were taken by 40.7% of patients (1632/4010) overall (48.3% of those with HBV infection and 27.0% of those with HCV infection), while 15.8% (635/4010) took other Chinese traditional medicines (other than herbs), and 2.7% (108/4010) took vitamin preparations.

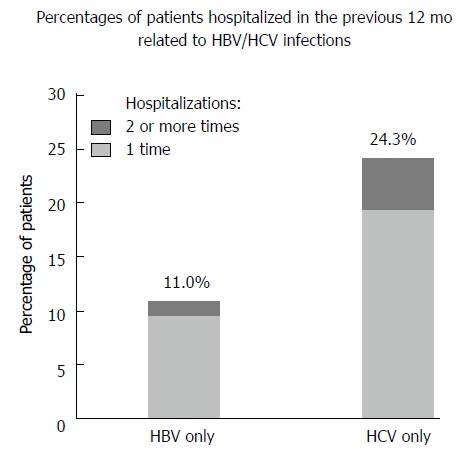

Hospitalizations

In the 12 mo prior to the study, a total of 770 patients (19.2%) had been hospitalized 1 or more times. Individuals with HCV infection or HBV/HCV co-infection were 2 or 3 times more likely to be hospitalized due to their infections than those with HBV infection (24.3% and 35.7% vs 11.0%, respectively). Percentages of patients who were hospitalized once and 2 or more times related to HBV/HCV infections are shown in Figure 2. The median duration of hospitalization in the total study population was 14 d (range, 2-90 d).

Figure 2.

Percentages of patients with hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus infection hospitalized in the previous 12 mo related to hepatitis B virus/hepatitis C virus infections.

DISCUSSION

Despite its short-term observational nature, this cross-sectional study provides important real-time data on the clinical characteristics of hepatitis infections in outpatients and on current management practice in China. Although numerous studies of the outcome of treatments for HBV/HCV infections have been conducted in China, few studies have attempted to profile the clinical characteristics of patients with these infections or patients’ acceptance of and responses to the antiviral treatments administered. Consequently, the data obtained are valuable in helping to understand how patients are currently being managed in China, and where efforts to improve the overall quality of management need to be directed.

The HBV-infected patients in this study had a longer duration of disease from the time of diagnosis (median, 7.5 vs 1.8 years) but a lower average age (38.3 vs 46.9 years) compared with the HCV-infected patients, in agreement with other studies that have generally described HCV patients as being older[20,21]. Liver cirrhosis was the most frequent complication in the patients we studied, and one-third of the cirrhosis cases were identified either before or at diagnosis, which suggests that some patients did not have a timely diagnosis. As current guidelines recommend screening for HBV infection in high prevalence countries, and screening for HCV infection in high-risk populations[17,19], establishing an effective routine screening program for HBV or HCV infections could benefit the patients’ prognoses (since this is influenced by early diagnosis and treatment), and also help to reduce disease transmission.

Although the likely route of transmission was unclear in a proportion of patients, particularly those with HBV infection, the transmission routes that were recorded were similar to those reported in other studies, in that HBV infection was principally transmitted by perinatal, percutaneous and sexual exposure, whereas HCV infection was mainly caused by exposure to infectious blood[17,19]. Intravenous drug use and skin perforations/tatoos were identified as potential routes of infection in only 1.7% and 2.1% of HCV-infected patients, respectively.

The proportion of patients in whom genotyping was performed was much higher in HCV-infected patients than in HBV-infected patients (10.2% vs 1.8%, respectively), probably because knowledge of the HCV genotype is helpful to guide antiviral treatment, but the proportion in whom HCV genotyping was performed was significantly lower than expected. The current guideline[19] recommends that HCV RNA should be determined by a highly sensitive quantitative assay shortly before or at the initiation of treatment, and thereafter at week 12 of therapy so that treatment can be adjusted according to both the response and the individual genotype. Our findings indicate that HCV genotyping is, to some extent, neglected in clinical practice in China and that more attention needs to be paid to such testing. The predominant genotypes in the HCV-infected patients in our study were genotype 1 (56.9%) and genotype 2 (20.8%), which was similar to the findings of previous studies[22,23].

Biopsies can help to assess the degree of the liver damage and make decisions on therapy, and current guidelines recommend biopsies in patients who do not meet clear-cut guidelines for treatment[15,17,19]; however, patients are often reluctant to accept a biopsy in China because of its invasive nature, and the proportion of patients in this study who had ever received a liver biopsy was only 1.3%. In patients who do not agree to undergo a biopsy, noninvasive tests are useful in defining the presence or absence of advanced fibrosis in those with chronic hepatitis infection[19], and these tests have become more practical in clinical practice in China, although it is appreciated that non-invasive tests should not replace liver biopsies in routine clinical practice. Our data indicate that the proportion of patients who underwent non-invasive tests to assess fibrosis (principally Fibroscan®) was only 13.3%, and this test should have been more widely used.

In terms of antiviral treatment, our study showed that around 58% of HBV-infected and 67% of HCV-infected patients had received or were receiving ongoing antiviral treatment. In comparison, a study conducted in Belgium found that 25% of HBV carriers and 54% of newly diagnosed patients with HCV infection were receiving antiviral therapy[20]. In the United States, another study reported that antiviral therapy was being received by 57.9% of HBV-infected patients and 79.9% of HCV-infected patients[24].

In HBV-infected patients who were receiving antiviral treatment, nucleos(t)ide analogs (NAs) were the most commonly used antiviral agents for ongoing therapy; adefovir dipivoxil was received by 46% of patients and lamivudine by 31%. In comparison, conventional IFN or PEG-IFN was received by only 14%. The higher proportion of NA use is probably due to their greater convenience and better tolerability, which makes them more easily accepted by both patients and clinicians. However, NAs do have some shortcomings such as the requirement for life-time use and the emergence of resistance. Moreover, they have been associated with a lower HBe seroconversion rate than IFN in clinical trials[18]. Only around 54% of our HBV-infected patients who were receiving antiviral therapy were evaluable for treatment responses, but the remainder were not able to be evaluated, mainly because their treatment course was still ongoing and they hadn’t reached the right time to evaluate their treatment or they might not have been evaluated on time.

On the basis of the most recent evaluation, 58% of HBV-infected patients in this study achieved normal ALT/AST levels; 80% had undetectable HBV DNA or a decrease of ≥ log10 (IU/mL), and 13% had a serological response, which are slightly lower response rates than those reported in clinical trials[18]. These lower response rates could be explained by the real-life nature of this study. Firstly, real-life populations are much more complex than those in clinical trials, and secondly, many other factors that may impact on efficacy are not as strictly controlled as in clinical trials, such as the treatment duration, dosages of antiviral agents, and adherence to treatment. In addition, adefovir dipivoxil, which had the highest usage rate in our study, has been associated with the lowest treatment response rates[18], and the proportion of patients who were receiving IFN was very low. We also noted that the sustained response rate (i.e., in patients who were followed for at least 6 mo after completing their course of treatment) was only 13%, which was lower than expected, as previous reports from clinical trials have indicated that the sustained response rate at 6 mo post-treatment was 31% to 45% for PEG-IFN therapy and 17% to 31% for lamivudine monotherapy, and sustained response rates at 12 mo to 2-5 years were only slightly lower[25-27].

In HCV-infected patients, PEG-IFN + ribavirin is recommended as the standard therapy[19]. In our study, the proportion of HCV-infected patients receiving PEG-IFN + ribavirin for first-time therapy was around 66%, and the proportion receiving conventional IFN + ribavirin was around 31%. In patients receiving treatment who were able to be evaluated, a quick response at 12 wk was achieved in 30%, an early response at 24 wk was achieved in 36%, and a sustained viral response (SVR) was achieved in only 20% of the patients who had a response at the end of treatment and were followed for at least 24 wk. In clinical trials, an SVR at 48 wk of treatment of 53% to 56% for PEG-IFN + ribavirin and 30% to 40% for conventional IFN + ribavirin has been reported[28]. The reason for the lower response rates to anti-HCV treatment in our real-life population is largely related to the fact that around one-third of the patients received conventional IFN instead of PEG-IFN because of its lower cost.

Except for the reasons cited above, we did not perform assays for HBV or HCV in this study, and this may have impacted on the quality of treatment monitoring and influenced the evaluation of treatment and the strategies employed, such as whether to discontinue treatment at appropriate time according to test results.

Around 20% of the HBV- or HCV-infected patients in our study had hepatitis-related hospitalizations within the previous 12 mo. Notably, one-fifth of HCV-infected patients who had ever been hospitalized had multiple hospitalizations in the previous year. The median duration of hospitalization was 2 wk on each occasion. Our data also showed that although 75% of the patients in the study had medical insurance, the average self-pay rate for HBV or HCV treatment in outpatient departments was 87%, which reflects the heavy burden of HBV/HCV infections to both individual patients and society.

This observational, real-life study has identified some gaps between clinical practice and guideline recommendations in China. In order to achieve better health outcomes, several improvements need to be made to align clinical practice more closely to treatment guidelines, including: (1) routine screening for HBV/HCV infections so that patients are diagnosed earlier; (2) more thorough evaluation of HBV/HCV-infected patients tests, such as implementing fibrosis evaluations, genotype testing, and biochemical assessments to guide the therapeutic strategy; and (3) considering the use of more effective or recommended agents for both anti-HBV and anti-HCV therapy and adjusting treatments according to the response.

Our study has some limitations including the fact that information on previous treatments and tests were collected from outpatient records, and some data may therefore have been missed due to incomplete or lost medical records. Also, in the overall assessment of disease management, we did not analyze the data for various subgroups of patients, and this could be undertaken in future studies.

In conclusion, the findings of this study from the western region of China provide the basis for a national longitudinal study to better characterize the clinical and treatment profiles of patients with HBV and HCV infection, and facilitate development of improved public health practice. Among the 4010 patients who were selected for inclusion in the study, analysis of disease assessment procedures and the treatments administered revealed limitations in the current management of patients with these infections that departed from current Asia-Pacific and international guideline recommendations. These limitations need to be addressed, e.g., by paying more attention to the monitoring of patients, using more effective agents for treatment, and screening patients for HBV/HCV infections in order to improve health outcomes and reduce the burden of these diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Editorial assistance was provided by Content Ed Net, Shanghai Co. Ltd.

COMMENTS

Background

Hepatitis B and hepatitis C caused by infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), respectively, remain serious health problems worldwide. In China, about 30 million people are chronically infected with HBV, and around 300000 die from HBV-related diseases every year. Likewise, the burden of HCV infection is also significant in China. A nationwide survey conducted in 1992 estimated the prevalence of HCV infection at 3.2%. Following acquisition of HCV, chronic infection develops in 75%-85% of infected individuals, and in these patients, cirrhosis develops in up to 20%. In patients with HCV-associated cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma develops in 3%-4% each year.

Research frontiers

In view of the major socioeconomic consequences of HBV and HCV infection, identifying patient characteristics and current treatment practice for these diseases assumes major importance for improving the quality of treatment and public health practices in controlling them. The objective of this multicenter, cross-sectional, outpatient study was to provide important information on patients with HBV or HCV infections in China to identify gaps in their management and whether treatment practices differ from Asia-Pacific and international guideline recommendations.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Despite its short-term, observational nature, the study provides important real-time data on the clinical characteristics of hepatitis infections in Chinese outpatients and on current management practice in China. Although numerous studies of the outcome of treatments for HBV/HCV infections have been conducted in China, few have attempted to profile the clinical characteristics of patients with these infections or patients’ acceptance of and responses to the antiviral treatments administered. Consequently, the data obtained are valuable in helping to understand how patients are currently being managed in China, and where efforts to improve the overall quality of management need to be directed.

Applications

The study’s findings point to a number of improvements that need to be made to align clinical practice more closely with current treatment guidelines for HBV and HCV infections. These include: (1) routine screening for infections so that patients are diagnosed earlier; (2) more thorough evaluation of HBV/HCV-infected patients, such as implementing fibrosis evaluations, genotype testing, and biochemical assessments to guide the therapeutic strategy; and (3) considering the use of more effective antiviral agents for both anti-HBV and anti-HCV therapy and adjusting treatments according to the response.

Peer review

This is an interesting study with a large cohort of patients.

Footnotes

Supported by Financial support for this study was provided by Merck Sharp and Dohme (China) Ltd

P- Reviewer: Sporea I, Wu WJ S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Du P

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Hepatitis B. Fact Sheet No. 204. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/index.html.

- 2.World Health Organization. Hepatitis C. Fact Sheet No. 164. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/

- 3.Baldo V, Baldovin T, Trivello R, Floreani A. Epidemiology of HCV infection. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:1646–1654. doi: 10.2174/138161208784746770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Locarnini S. Molecular virology of hepatitis B virus. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24 Suppl 1:3–10. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCaughan GW, Omata M, Amarapurkar D, Bowden S, Chow WC, Chutaputti A, Dore G, Gane E, Guan R, Hamid SS, et al. Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver consensus statements on the diagnosis, management and treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:615–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shepard CW, Simard EP, Finelli L, Fiore AE, Bell BP. Hepatitis B virus infection: epidemiology and vaccination. Epidemiol Rev. 2006;28:112–125. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxj009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zou L, Zhang W, Ruan S. Modeling the transmission dynamics and control of hepatitis B virus in China. J Theor Biol. 2010;262:330–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu GT, Si CW, Wang QH, Chen LH, Chen HS, Xu DZ, Zhang LX, Wang BE, Wang LT, Li Y. Comments on the prevention and research of chronic hepatitis in China. Zhonghua Yixue Zazhi. 2002;82:74–76. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jia JD, Zhuang H. The overview of the seminar on chronic hepatitis B. Zhonghua GanZangBing ZaZhi. 2004;12:698–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstein ST, Zhou F, Hadler SC, Bell BP, Mast EE, Margolis HS. A mathematical model to estimate global hepatitis B disease burden and vaccination impact. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:1329–1339. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xia GL, Liu C, Cao H, Bi S, Zhan M, Su C, Nan J, Qi X. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infections in the general Chinese population. Results from a nationwide cross-sectional seroepidemiological study of hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E virus infections in China, 1992. Int Hepatol Communicat. 1996;5:62–73. [Google Scholar]

- 12.NIH Consensus Statement on Management of Hepatitis C: 2002. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2002;19:1–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rustgi VK. The epidemiology of hepatitis C infection in the United States. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:513–521. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strader DB, Wright T, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2004;39:1147–1171. doi: 10.1002/hep.20119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liaw YF, Leung N, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, Gane E, Han KH, Guan R, Lau GK, Locarnini S. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2008 update. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:263–283. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9080-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorrell MF, Belongia EA, Costa J, Gareen IF, Grem JL, Inadomi JM, Kern ER, McHugh JA, Petersen GM, Rein MF, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: management of hepatitis B. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:104–110. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-2-200901200-00100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661–662. doi: 10.1002/hep.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:227–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335–1374. doi: 10.1002/hep.22759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Vroey B, Moreno C, Laleman W, van Gossum M, Colle I, de Galocsy C, Langlet P, Robaeys G, Orlent H, Michielsen P, et al. Hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections in Belgium: similarities and differences in epidemics and initial management. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:613–619. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835d83a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spradling PR, Rupp L, Moorman AC, Lu M, Teshale EH, Gordon SC, Nakasato C, Boscarino JA, Henkle EM, Nerenz DR, et al. Hepatitis B and C virus infection among 1.2 million persons with access to care: factors associated with testing and infection prevalence. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1047–1055. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu L, Nakano T, He Y, Fu Y, Hagedorn CH, Robertson BH. Hepatitis C virus genotype distribution in China: predominance of closely related subtype 1b isolates and existence of new genotype 6 variants. J Med Virol. 2005;75:538–549. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui Y, Jia J. Update on epidemiology of hepatitis B and C in China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28 Suppl 1:7–10. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moorman AC, Gordon SC, Rupp LB, Spradling PR, Teshale EH, Lu M, Nerenz DR, Nakasato CC, Boscarino JA, Henkle EM, et al. Baseline characteristics and mortality among people in care for chronic viral hepatitis: the chronic hepatitis cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:40–50. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piratvisuth T, Lau G, Chao YC, Jin R, Chutaputti A, Zhang QB, Tanwandee T, Button P, Popescu M. Sustained response to peginterferon alfa-2a (40 kD) with or without lamivudine in Asian patients with HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:102–110. doi: 10.1007/s12072-007-9022-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fung SK, Wong F, Hussain M, Lok AS. Sustained response after a 2-year course of lamivudine treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:432–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2004.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong VW, Wong GL, Yan KK, Chim AM, Chan HY, Tse CH, Choi PC, Chan AW, Sung JJ, Chan HL. Durability of peginterferon alfa-2b treatment at 5 years in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;51:1945–1953. doi: 10.1002/hep.23568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu ML, Chuang WL. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in Asia: when East meets West. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:336–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]