Abstract

Major changes have emerged during the last few years in the therapy of patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC). Several direct acting antiviral agents (DAAs) have been developed showing potent activity against hepatitis C virus (HCV) and incrementally improving the rates of sustained virological response (SVR), even in difficult-to-treat CHC patients. Sofosbuvir, a new nucleotide analog, HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitor, represents the first key step towards the new era in the management of CHC, since it is the first approved DAA with excellent tolerability and favorable pharmacokinetic profile, limited potential for drug interactions, potent antiviral activity and high genetic barrier against all HCV genotypes. Sofosbuvir has recently become commercially available in combination with ribavirin, with or without pegylated interferon, achieving high SVR rates after 12-24 weeks of therapy. Finally, since interferon-free regimens are close to becoming the new standard of care in CHC patients, sofosbuvir has an ideal profile to be the cornerstone antiviral agent, especially in difficult-to-treat CHC patients, given in combination with other new DAAs. This review summarizes the main updated issues related to the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir-containing regimens in CHC patients.

Keywords: Sofosbuvir, hepatitis C, direct acting antiviral agents

Introduction

It is estimated that up to 170-200 million people (i.e. 3% of the world population) are chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) [1]. Chronic hepatitis C (CHC) infection can lead to cirrhosis and its complications, such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [2,3]. Epidemiological studies indicate that 350,000 people worldwide die from hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related chronic liver disease every year but it is projected to continue rising for another 20 years [2]. In addition, CHC is currently the most common indication for liver transplantation (LT) in almost all Western countries [4].

Early diagnosis and treatment are essential for the improvement of the long-term outcomes in CHC patients. The goal of HCV treatment is to achieve sustained virological response (SVR) defined as undetectable HCV RNA at 24 weeks or recently at 12 weeks after the end of therapy. Until 2011-2012, the combination of pegylated interferon-α (pegIFN) and ribavirin (RBV) was considered to be the standard of care (SOC) in CHC achieving SVR in approximately 40-50% of genotype 1 patients after 48 weeks of therapy and 70-80% for genotype 2 and 3 patients after 24 weeks of therapy [5,6]. During the last decade, intensive efforts focused on the development of direct acting antiviral agents (DAAs) that can block the activity of viral enzymes targeting either NS3-4A serine protease, which block HCV polyprotein processing, or HCV replication. The latter include several drug families, such as nucleoside/nucleotide and non-nucleoside inhibitors of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and inhibitors of the NS5A viral protein which has a regulatory role in HCV replication [7]. Potentially, each step of the viral cycle is a target for drug development [7].

Two NS3-4A serine protease inhibitors, boceprevir and telaprevir, were the first generation DAAs approved for clinical use in genotype 1 CHC patients in mid 2011. With the triple combination of pegIFN, RBV and boceprevir or telaprevir, the probability of SVR increased by 30% in naïve patients, by 50-60% in relapsers and by 25% in null responders [5]. However, these first generation DAAs have a low genetic barrier to resistance, their efficacy is limited to HCV genotype 1 and co-administration of pegIFN and RBV is needed. Thus, patients with contraindications to pegIFN and/or RBV cannot be treated with these agents. In addition, the triple regimens are associated with unfavorable tolerance and safety profiles, particularly in patients with underlying cirrhosis, i.e. those who would gain more from successful eradication of HCV [5]. In the CUPIC trial, there was a 44% risk of death or significant complications, such as hepatic decompensation or serious infection, with triple therapy in cirrhotic patients with a platelet count <100,000/mm3 and an albumin level <3.5 g/dL [8]. Finally, the pill burden is high (6 tablets for telaprevir and 12 tablets for boceprevir daily), while there are several potential drug interactions with these agents which may complicate the management of treated patients [9].

Sofosbuvir (Sovaldi®, Gilead Sciences) is a direct acting pyrimidine nucleotide analog representing the first NS5B HCV polymerase inhibitor [10]. It was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency and has become commercially available for the treatment of CHC in the US in late 2013 and in several European countries in early 2014 [9]. It is administered at a dosage of 400 mg once daily, taken with or without food, and has a potent activity against all HCV genotypes. Sofosbuvir is also being developed as a fixed-dose combination (co-formulation in one tablet) with ledipasvir, an HCV NS5A inhibitor, with potent anti-HCV activity.

Pharmacodymamics-pharmacokinetics of sofosbuvir

Sofosbuvir, originally termed as PSI-7977, is a nucleotide prodrug that undergoes intracellular metabolism to form the pharmacologically active uridine analog triphosphate (GS-461203), which can be incorporated into HCV RNA by the NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) acting as a chain terminator. Studies in replicon cells containing different HCV genotypes showed that sofosbuvir is active against all HCV genotypes without any antagonistic effect in co-administration of interferon or RBV [11].

Sofosbuvir results in rapid reduction of viral load. Although HCV variants with the S282T mutation causing reduced susceptibility against sofosbuvir have been identified in vitro, clinical studies demonstrated that sofosbuvir has a high resistance barrier, since no S282T mutation was detected in patients who relapsed after receiving sofosbuvir in combination with RBV with or without pegIFN or a second DAA [11]. This mutation was detected in one HCV genotype 2b patient at week 4 after treatment with sofosbuvir monotherapy in the ELECTRON phase II study indicating that sofosbuvir should not be used as monotherapy.

Sofosbuvir has a very favorable pharmacokinetic profile. Following oral administration, peak plasma concentrations of sofosbuvir and its major circulating metabolite GS-331007 are achieved after 0.5-2 and 2-4 h respectively [12], without being affected by food administration. It is approximately 61-65% bound to human plasma proteins and is eliminated mainly via renal clearance (78%) as GS-331007. The median terminal half-lives of sofosbuvir and GS-331007 are 0.4 and 27 h, respectively [13].

Based on the available data, the pharmacokinetics of sofosbuvir and GS-331007 do not seem to be significantly affected by other epidemiological factors, such as age, gender, body mass index, race or presence of cirrhosis. In patients with creatinine clearance >30 mL/min, no dose adjustment is required, while for those with creatinine clearance <30 mL/min or under hemodialysis, no dose recommendation can be given and thus sofosbuvir is contraindicated [14]. No dose adjustment of sofosbuvir is recommended for patients with moderate and severe hepatic dysfunction [12]. Pregnancy should be avoided in both female patients and female partners of male patients who receive any current sofosbuvir containing regimen and for at least 6 months following cessation of therapy.

Sofosbuvir has limited potential for interactions with other drugs because its metabolism is not linked to the hepatic CYP3A4 pathway. However, avoidance of a combination with carbazepine and rifabutin is recommended because these drugs are potent P-glycoprotein inducers and can significantly decrease sofosbuvir plasma concentrations leading to a reduced therapeutic effect. Importantly, interactions were not seen with other DAAs (e.g. NS5A inhibitors such as daclatasvir or ledipasvir, or NS3 protease inhibitors such as simeprevir), immunosuppressive agents, such as calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and cyclosporine), or several antiretroviral agents (e.g. efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir/raltegravir/ritonavir).

Safety profile of sofosbuvir

Sofosbuvir has an excellent tolerability and safety profile. This has been assessed in several clinical trials including more than 3000 CHC patients, with the majority of clinical adverse events being of grade 1 severity. Most severe adverse events have been observed in sofosbuvir combinations with RBV and/or pegIFN. In the clinical trials of sofosbuvir, the proportion of CHC patients who discontinued treatment due to adverse events was 4% in placebo groups, 1% in sofosbuvir plus RBV groups and 2% in sofosbuvir plus pegIFN and RBV groups [11]. Its excellent safety profile makes sofosbuvir an optimal choice for patients with decompensated cirrhosis and liver transplant recipients as well as for patients who cannot tolerate interferon and/or RBV.

Sofosbuvir and RBV with or without pegIFN in CHC patients

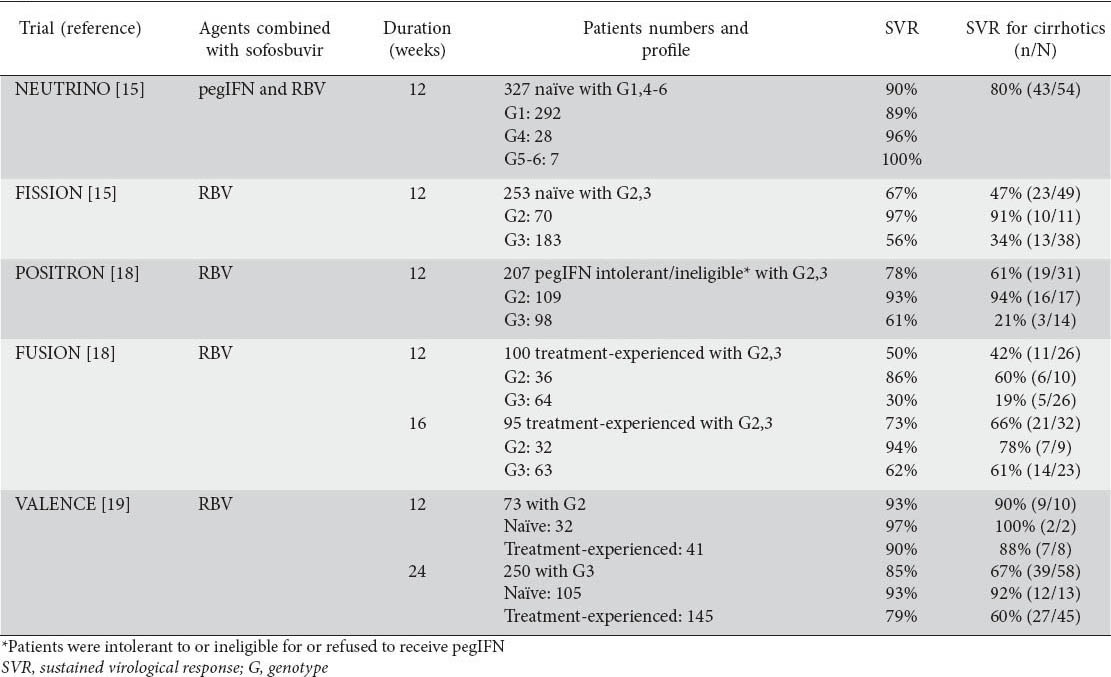

CHC genotype 1 (Table 1)

Table 1.

Phase III clinical trials with sofosbuvir plus ribavirin (RBV) with or without pegylated interferon-alfa (pegIFN) for patients with chronic hepatitis C

Treatment-naïve patients

The efficacy and safety of the combination of sofosbuvir, pegIFN and RBV in naïve CHC genotype 1 patients were evaluated in the NEUTRINO trial. This was a single arm phase III study including naive CHC patients with HCV genotype 1, 4, 5 or 6, who received sofosbuvir plus pegIFNa-2a (180 μg per week) and weight-based RBV (total daily dose of 1000 or 1200 mg for those with body weight ≤75 or >75 kg, respectively) for 12 weeks. Of the 327 patients, 17% had cirrhosis. Genotype 1 patients, who represented 89% of the patient population, achieved high SVR rate of 90% (1a: 92%; 1b: 82%). SVR rates were lower in cirrhotics than non-cirrhotics (80% vs. 93%), while they were not affected by race, gender, body mass index and baseline viral load. Only 1.5% of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events. No virological breakthroughs occurred during treatment and no resistance-associated variants were detected among patients who relapsed after the end of treatment [15].

Treatment-experienced patients

The combination of pegIFN and RBV has not been evaluated in phase III trials including treatment-experienced patients. In one arm of a phase II multicenter open-label study with 22 treatment arms (ELECTRON), sofosbuvir plus weight-based RBV for 12 weeks offered poor SVR rates in genotype 1 prior null responders to pegIFN and RBV (10% or 1/10) [16]. In a very recent report, however, sofosbuvir plus RBV and pegIFN, all given for 12 weeks, achieved SVR in 74% (37/50) of difficult to treat CHC patients with genotype 1 who had previously failed to respond to various triple or quadruple regimens containing pegIFN, RBV and 1-2 DAAs [17]. Such findings suggest that the combination of sofosbuvir with RBV for 12 weeks is not enough and perhaps sofosbuvir combined with pegIFN and RBV or another DAA is necessary to achieve acceptable rates of HCV eradication in genotype 1 treatment-experienced patients.

CHC genotype 2 and 3 (Table 1)

Treatment-naïve patients

In a phase III non-inferiority trial study named FISSION, nearly 500 genotype 2 or 3 naïve CHC patients were randomized to receive sofosbuvir plus weight-based RBV for 12 weeks (n=256) or SOC, i.e. pegIFN plus RBV (800 mg daily) for 24 weeks (n=243). Approximately 20% had cirrhosis and 29% had interleukin-28B (IL28B) CC genotype. The combination of sofosbuvir plus RBV achieved SVR in 97% of genotype 2 (78% with SOC) and 56% of genotype 3 patients (63% with SOC). SVR rates under sofosbuvir and RBV were lower in patients with cirrhosis (genotype 2: 91%, genotype 3: 34%) compared to those without cirrhosis (genotype 2: 98%, genotype 3: 61%) without significant difference from the SVR achieved by SOC in any subgroup. Sofosbuvir and RBV combination, compared to SOC, had significantly lower rates of adverse events and treatment discontinuation [15].

In another phase III, placebo-controlled trial named POSITRON, 278 patients with CHC genotype 2 or 3 who were interferon intolerant or ineligible or had refused pegIFN therapy were randomized to receive sofosbuvir plus weight-based RBV (n=207) or placebo (n=71) for 12 weeks. About 45% had IL28B CC genotype and 15% cirrhosis. SVR was achieved in 78% of patients in the sofosbuvir arm and 0% in the placebo arm. SVR rate was significantly higher in genotype 2 than genotype 3 patients (93% vs. 61%, P<0.001). The presence of cirrhosis did not affect the SVR rates in genotype 2 patients (94% vs. 92%), but it had a great impact on the SVR rates in genotype 3 patients (21% vs. 68%, P=0.002) [18].

In a third phase III trial named VALENCE including genotype 2 and 3 naïve CHC patients, sofosbuvir plus weight-based RBV was given for 12 weeks in genotype 2 (n=32) and for 24 weeks in genotype 3 patients (n=105). SVR was achieved in 97% of genotype 2 (non-cirrhotics: 97%, cirrhotics: 100%) and 93% of genotype 3 patients (non-cirrhotics: 94%, cirrhotics: 92%). The rates of discontinuation were negligible without evidence of viral resistance among the patients who relapsed after treatment [19].

Treatment-experienced patients

A phase III trial named FUSION included 195 genotype 2 or 3 CHC patients who had failed to achieve SVR after prior SOC treatment. These patients (75% prior relapsers, 25% prior non-responders) were randomized to receive sofosbuvir plus weight-based RBV for 12 (n=103) or 16 weeks (n=98). The 12-week and 16-week courses achieved SVR in 86% and 94% of genotype 2 and 30% and 62% of genotype 3 patients. The probability of SVR was high in both treatment arms of non-cirrhotic genotype 2 patients (96% and 100%), while the 16-week compared to the 12-week course achieved numerically higher SVR rates in genotype 2 patients with cirrhosis, but the patient numbers were too small for any valid statistical significance (78% or 7/9 vs. 60% or 6/10). In genotype 3 patients, however, 16 compared to 12 weeks of treatment achieved significantly higher SVR rates in both non-cirrhotic (63% or 25/40 vs. 37% or 14/38, P=0.040) and cirrhotic patients (61% or 14/23 vs. 19% or 5/26, P=0.004) [18].

In the VALENCE trial described above, 145 treatment-experienced CHC patients with genotype 3 were treated with sofosbuvir plus weight-based RBV for 24 weeks [19]. The overall SVR rate was 79% being higher than the 62% SVR rate achieved with the same combination given for 16 weeks in the FUSION trial. Keeping in mind that comparing response rates across different trials may not lead to valid conclusions, the 24-week course of sofosbuvir and RBV in the VALENCE trial compared to the 16-week similar course in the FUSION trial in genotype 3 treatment-experienced patients offered higher SVR rates in non-cirrhotic (87% vs. 63%) but not in cirrhotic cases (60% vs. 61%).

Because of the not very high SVR rates in genotype 3 patients treated with the combination sofosbuvir and RBV particularly for 12 weeks, the combination of sofosbuvir with RBV and pegIFN given for 12 weeks was also evaluated in genotype 2 or 3 treatment-experienced patients. In a single arm phase II trial named LONESTAR-2, such a triple combination offered SVR rates of 96% (22/23) in genotype 2 and of 83% (20/24) in genotype 3 patients [20].

CHC genotype 4, 5 and 6 (Table 1)

The NEUTRINO trial included 28 CHC patients with genotype 4 and 7 patients with genotype 5 or 6 who were treated with sofosbuvir plus pegIFN and weight-based RBV for 12 weeks. The SVR rates were 96% in genotype 4 and 100% in genotype 5-6 patients [15]. In a recently reported open label phase II study [21], 28 treatment-naïve, and 32-experienced Egyptian ancestry patients with genotype 4 were randomized to receive the combination of sofosbuvir plus weight-based RBV for 12 or 24 weeks. At baseline, 57% of them had high viremia (HCV RNA ≥6 log10 IU/mL) and 83% had IL28B non-CC genotype. At week 4 on treatment, 98% had HCV RNA was undetectable in 98% and 100% of patients at 4 weeks and at the end of therapy. The SVR rates were 79% and 59% in treatment-naïve and -experienced patients treated for 12 weeks. In addition, the SVR rates at 4 weeks post-treatment were 100% and 93% in the treatment-naïve and -experienced patients treated for 24 weeks, while the final SVR rates at 12 weeks post-treatment have not yet been reported for these subgroups.

All oral combination regimen of sofosbuvir with new DAAs

Several interferon-free combination studies are ongoing or have already reported their results of the efficacy and safety of sofosbuvir with other DAAs, mainly NS5A inhibitors. These efforts represent major progress in the drug development against HCV.

Major phase II trials

In an open-label phase II study named COSMOS, 167 CHC patients with genotype 1 received sofosbuvir plus simeprevir (a new NS3/4A protease inhibitor) with or without RBV for 12 or 24 weeks. These patients were either null responders to previous SOC therapy with mild to moderate fibrosis (Cohort 1, n=80) or patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis regardless of previous exposure to treatment (Cohort 2, n=87). The combination of sofosbuvir plus simeprevir achieved excellent SVR rates (usually >94%) in all subgroups, irrespectively of duration of therapy (12 or 24 weeks) or co-administration of RBV in this difficult to treat setting [22].

In another open-label, phase II study named LONESTAR, one tablet co-formulation of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir (NS5A inhibitor) with or without weight-based RBV were given for 8 or 12 weeks in 100 genotype 1 CHC patients who were treatment-naïve or had failed a course with triple combination including a 1st generation protease inhibitor. The SVR rates were 95-100% in all subgroups regardless of previous treatment history or presence of cirrhosis. Adverse events were rare and always mild (nausea, anemia and headache), while one patient in the RBV-containing arm developed severe anemia [23].

In the phase II AI444040 trial, the safety and efficacy of 24-week courses of sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir (another NS5A inhibitor) with or without RBV were evaluated in 211 non-cirrhotics CHC patients with genotype 1, 2 or 3. Of the genotype 1 patients, 126 were treatment-naïve and 41 had failed to respond to telaprevir- or boceprevir-based regimens. SVR was achieved in 92% of 26 genotype 2 and 89% of 18 genotype 3 patients. The SVR rates were 98% in genotype 1 patients irrespective of previous treatment history and without substantial differences in relation to the subgenotype (1a: 98%, 1b: 100%), IL28B genotypes (CC: 93%, non-CC: 98%) and the use of RBV (94% vs. 98%) [24].

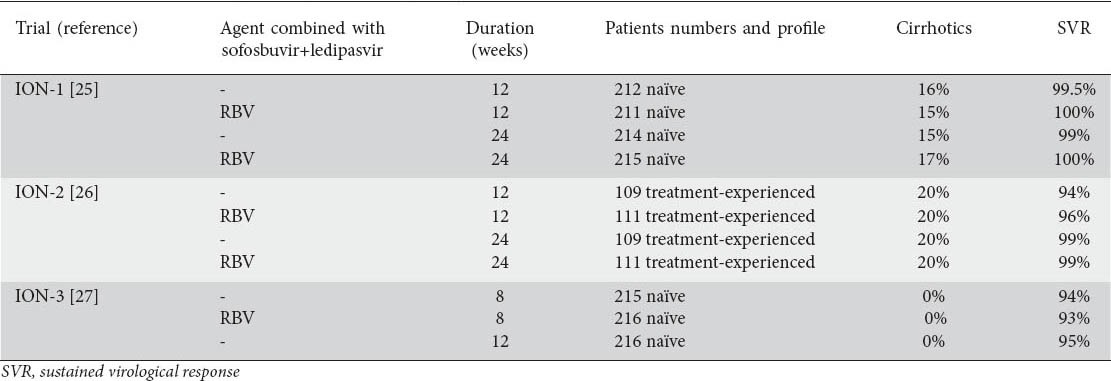

Phase III trials (Table 2)

Table 2.

Phase III trials of interferon-free combination of sofosbuvir with ledipasvir (one tablet co-formulation) with or without ribavirin (RBV) for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C patients with genotype 1

In an open-label phase III trial named ION-1, 865 treatment-naïve CHC patients with genotype 1 (genotype 1a: 67%, cirrhosis: 16%) were randomized to receive sofosbuvir-ledipasvir co-formulation with or without RBV for 12 or 24 weeks. Impressively high SVR rates (97-99%) were achieved in all treatment arms, while no patient discontinued sofosbuvir-ledipasvir due to an adverse event [25].

In another open-label phase III trial named ION-2, 440 treatment-experienced CHC patients with genotype 1 (genotype 1a: 79%, cirrhosis: 20%) were also randomized to receive sofosbuvir-ledipasvir co-formulation with or without RBV for 12 or 24 weeks. Patients included in this trial had failed to respond to pegIFN and RBV or to a triple regimen with a first generation protease inhibitor. Again, the SVR rates were impressively high (94-99%) across all treatment arms and no patient discontinued treatment due to a treatment-related adverse event [26].

Finally, in another open-label phase III trial named ION-3, the efficacy of shorter treatment duration with the sofosbuvir-ledipasvir combination was evaluated. In particular, 647 treatment-naïve non-cirrhotic CHC patients with genotype 1 (IL28B non-CC: 75%) were randomized to receive sofosbuvir-ledipasvir co-formulation with or without RBV for 8 or 12 weeks. SVR rates ranged from 93% to 95% in all treatment arms regardless of treatment duration and RBV co-administration. Only 3 patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events and 10 patients had serious adverse events but not related to treatment. Anemia was developed in 5% of all patients, but only in patients receiving RBV [27].

HCV decompensated cirrhosis and LT

HCV recurrence is universal in the liver graft after LT and is associated with an accelerated course. HCV RNA negativity at the time of operation most probably represents the most important factor to avoid HCV recurrence and graft loss. The first generation DAAs (telaprevir and boceprevir) cannot be easily given in candidates for LT, since they should be used in combination with the poorly tolerated pegIFN leading to high rates of serious adverse events including sepsis and death. In contrast, the new generation DAAs offer an opportunity for treatment in these difficult patients. In a recent open-label phase II study [28], 61 CHC patients with well compensated cirrhosis (Child-Pugh score ≤7) who were on the waiting list for LT because of HCC, received sofosbuvir (400 mg/day) and weight-based RBV for up to 48 weeks or until LT combination. Of 40 patients who underwent LT, 36 had undetectable HCV RNA (<25 IU/mL) at the time of LT. SVR was achieved in 18 (69%) of the 26 patients who had reached at least 12 weeks post-transplant follow up, while 7 (27%) patients experienced HCV recurrence and 1 (4%) patient died from liver graft dysfunction after re-LT. All but one patients with undetectable HCV RNA for at least 4 weeks before LT had no evidence of HCV recurrence after LT. Importantly, the tolerability was very good and only one patient developed a serious adverse event (anemia) attributable to the co-administration of RBV.

In a more recent randomized open label study [29], 40 CHC cirrhotics with genotypes 1-4 received sofosbuvir plus RBV for 48 weeks or were observed for 6 months and then crossed over to 48 weeks of treatment. All patients had portal hypertension with or without decompensated liver disease. The Child-Pugh score was 5-10 (20% were Child class B or C), while all patients had MELD score >13. The virological response rates at 4 and 12 weeks under treatment were 89% and 97%, respectively. No patient experienced treatment breakthroughs, the most common adverse events were nausea, fatigue and dizziness and one patient discontinued treatment due to adverse event. The final results of this study are awaited.

HCV recurrence after LT is associated with lower graft and patient survival, compared to those transplanted for other non HCV indications. Patients with recurrent HCV after LT have no effective treatment options, because they have poor tolerability or achieve low SVR rates with SOC or first generation protease inhibitors based regimens. The combination of sofosbuvir plus RBV with or without pegIFN was evaluated in 45 LT recipients with fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis due to HCV recurrence [30]. Sofosbuvir plus RBV was given in 36 (80%) and sofosbuvir plus RBV and pegIFN in 9 (20%) patients. At the end of follow up, the clinical condition improved in 32 (71%) and remained stable in 6 (13%) cases. Seven (16%) patients died due to progression of liver graft dysfunction or associated complications. There was no serious adverse event attributed to study drug.

In a second single-arm open-label pilot study [31], 40 treatment-naïve and experienced patients with HCV recurrence who were at least 6 months after LT received up to 24 weeks of sofosbuvir plus RBV given as ascending dosage starting at 400 mg daily. Thirty-three (83%) patients had genotype 1 and 9 patients were previously treated with telaprevir or boceprevir based regimens. By week 4 on treatment, all patients had HCV RNA <25 IU/mL, while the interim SVR rates at week 4 post-treatment was 81% (21/26). No episode of rejection was recorded and no dose adjustments of immunosuppression were required. The most common adverse events were fatigue, arthralgia and diarrhea and only 7 (18%) patients experienced mild to moderate anemia.

Discussion

The approval of sofosbuvir represents the first key step towards the new era in the management of CHC patients, since it is the first approved DAA with potent activity and high genetic barrier against all HCV genotypes [32]. In addition, its safety profile is excellent, even when it is given in patients with very advanced liver disease and high risk of complications (e.g. cirrhotics with portal hypertension, liver transplant recipients). It has an excellent pharmacokinetic profile allowing its administration as one tablet daily and has rather limited potential for drug-drug interactions. However, some issues remain to be elucidated including the reasons for HCV relapse after stopping a sofosbuvir-based regimen, the possible impact of host and viral factors associated with HCV eradication, the optimal duration in difficult-to-treat population, such as prior non-responders with cirrhosis and its use in patients with advanced decompensated cirrhosis.

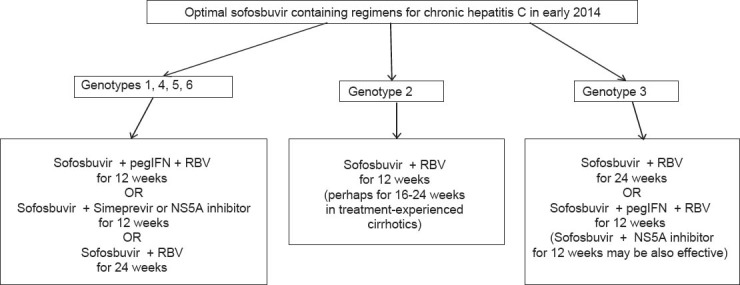

Based on the currently available data and according to the recently updated recommendations from the European Association from the Study of the Liver [33], the optimal sofosbuvir containing regimens in early 2014 are presented in Fig. 1 and briefly described below.

Figure 1.

Optimal sofosbuvir containing regimens for chronic hepatitis C in early 2014. Sofosbuvir is administered as one tablet of 400 mg daily, ribavirin (RBV) is administered as weight-based dosing (total daily dose of 1000 or 1200 mg for patients with body weight ≤75 or >75 kg, respectively) and pegylated interferon-alfa-2a (pegIFN) is administered as subcutaneous injections of 180 μg once weekly

-

a)

For patients with genotypes 1, 4, 5 and 6: triple combination with sofosbuvir plus pegIFN and weight-based RBV given for 12 weeks offers high SVR rates without any need for response guided therapy. Although strong data are not available, sofosbuvir plus weight-based RBV may be given for 24 weeks to patients with contraindications or intolerance to pegIFN.

-

b)

For patients with genotype 2: sofosbuvir plus weight-based RBV given for 12 weeks offers very high SVR rates in almost all subgroups. Whether treatment-experienced patients with genotype 2 and cirrhosis need longer treatment courses (16 or 24 weeks) is not clear yet.

-

c)

For patients with genotype 3, 24 weeks of sofosbuvir plus weight-based RBV are required for high SVR rates. Preliminary data have shown that the addition of pegIFN or another DAA will be necessary for allowing shortening of treatment duration to ≤12 weeks.

According to the data from the three ION trials and other recent phase II and III trials, the treatment of CHC is rapidly moving to interferon-free regimens, which are very close to becoming the new scientific standard of care for CHC patients [33]. In this concept, sofosbuvir represents an almost ideal backbone, especially in difficult-to-treat CHC patients with cirrhosis or liver impairment, liver transplant recipients, co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus and other co-morbidities. In particular, 8-12 week courses with the combination of sofosbuvir with a potent NS5A inhibitor (e.g. ledipasvir or daclatasvir) or NS3 protease inhibitor (e.g. simeprevir) have been shown to achieve SVR in almost all genotype 1 patients without safety and tolerability concerns. However, despite all such amazing scientific progress and the potential to cure HCV in all CHC patients regardless of the liver disease severity, the high cost of the new DAAs including sofosbuvir is raising discussions and public health debates about their optimal and most cost-effective use which may differ among different countries.

Biography

Medical School of Aristotle University, Hippokration General Hospital of Thessaloniki; Athens University Medical School, Laiko General Hospital, Athens, Greece

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Evangelos Cholongitas has served as an advisor and/or lecturer for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead and Novartis and has received research grants from Gilead; George Papatheodoridis has served as an advisor and/or lecturer for Abbvie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Glaxo-Smith Kleine, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Roche and has received research grants from Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, Roche

References

- 1.Lavanchy D. The global burden of hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2009;29(Suppl 1):74–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alter MJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2436–2441. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i17.2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maasoumy B, Wedemeyer H. Natural history of acute and chronic hepatitis C. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:401–412. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terrault N. Liver transplantation in the setting of chronic HCV. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:531–548. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexopoulou A, Papatheodoridis GV. Current progress in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6060–6069. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i42.6060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papatheodoridis GV, Cholongitas E. Chronic hepatitis C and no response to antiviral therapy: potential current and future therapeutic options. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:287–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2004.00522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis GV. Review article: novel therapeutic options for chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:866–884. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hezode C, Fontaine H, Dorival C, et al. Effectiveness of telaprevir or boceprevir in treatment-experienced patients with HCV genotype 1 infection and cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:132–142. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.051. e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pawlotsky JM. Hepatitis C virus: standard-of-care treatment. Adv Pharmacol. 2013;67:169–215. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-405880-4.00005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herbst DA, Jr, Reddy KR. Sofosbuvir, a nucleotide polymerase inhibitor, for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2013;22:527–536. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2013.775246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keating GM, Vaidya A. Sofosbuvir: first global approval. Drugs. 2014;74:273–282. doi: 10.1007/s40265-014-0179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirby B, Gordi T, Symonds W, Kearney B, Mathias A. Population pharmacokinetics of sofosbuvir and its major metabolite (GS-331007) in healthy and HCV infected adult subjects. Hepatology. 2013;58(Suppl 4):746A. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez-Torres M. Sofosbuvir (GS-7977), a pan-genotype, direct-acting antiviral for hepatitis C virus infection. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2013;11:1269–1279. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2013.855126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornpropst MT, Denning J, Clemons D, et al. The Effect of Renal Impairment and End Stage Renal Disease on the Single-Dose Pharmacokinetics of GS-7977. J Hepatol. 2012;56:S433. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1878–1887. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gane EJ, Stedman CA, Hyland RH, et al. Nucleotide polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:34–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pol S, Sulkowski M, Hassanein T, et al. Successful retreatment with sofosbuvir of HCV genotype-1 infected patients who failed prior therapy with peginterferon + ribavirin plus 1 or 2 additional direct-acting antiviral agents. J Hepatol. 2014;60(Suppl 1):S23. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobson IM, Gordon SC, Kowdley KV, et al. Sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 in patients without treatment options. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1867–1877. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeuzem S, Dusheiko G, Salupere R, et al. Sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for 12 or 24 weeks for patients with HCV genotype 2 or 3: the VALENCE trial. Hepatology. 2013;58(Suppl 4):733A. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawitz E, Poordad F, Brainanrd D, et al. Sofosbuvir in combination with PegIFN and ribavirin for 12 weeks provides high SVR rates in HCV-infected genotype 2 or 3 treatment experienced patients with and without compensated cirrhosis: results from the LONESTAR-2 study. Hepatology. 2013;58(Suppl 4):1380A. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raune P, Ain D, Riad J, et al. Sofosbuvir plus ribavirin in the treatment of chronic HCV genotype 4 infection in patients of Egyptian ancestry. Hepatology. 2013;58(Suppl 4):736A. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobson JM, Ghalib R, Rodriguez-Torres M, et al. SVR results of a once-daily regimen of simeprevir (TMC435) plus sofosbuvir (GS-7977) with or without ribavirin in cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic HCV genotype 1 traetment-naive and prior null responder patients: the COSMOS study. Hepatology. 2013;58(Suppl 4):1379A. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawitz E, Poordad FF, Pang PS, et al. Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir fixed-dose combination with and without ribavirin in treatment-naive and previously treated patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection (LONESTAR):an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:515–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sulkowski MS, Gardiner DF, Rodriguez-Torres M, et al. Daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir for previously treated or untreated chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:211–221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Afdhal N, Zeuzem S, Kwo P, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1889–1898. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Afdhal N, Reddy KR, Nelson DR, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1483–1493. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1316366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kowdley KV, Gordon SC, Reddy KR, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for 8 or 12 weeks for chronic HCV without cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1879–1888. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curry M, Forns X, Chung R, et al. Pretransplant sofosbuvir and ribavirin to prevent recurrence of HCV infection after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2013;58(Suppl 4):314A. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Afdhal N, Everson G, Calleja J, et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C with cirrhosis and portal hypertension with or without decompensation: early virologic response and safety. J Hepatol. 2014;60:S23. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forns X, Fontana RJ, Moonka D, et al. Initial evaluation of the sofosbuvir compassionate use program for patients with severe recurrent HCV following liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2013;58(Suppl 4):732A. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charlton E, Gane E, Manns MP, et al. Sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for established recurrent HCV infection after liver trans-plantation: preliminary results of a prospective, multicenter study. Hepatology. 2013;58(Suppl 4):1378A. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marino Z, van BF, Forns X, Berg T. New concepts of sofosbuvir-based treatment regimens in patients with hepatitis C. Gut. 2014;63:207–215. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C. 2014. http://files.easl.eu/easl-recommendations-on-treatment-of-hepatitis-C/index.html . [DOI] [PubMed]