Abstract

Protein S-nitrosylation, the nitric oxide-mediated posttranslational modification of cysteine residues, has emerged as an important regulatory mechanism in diverse cellular processes. Yet, knowledge about the S-nitrosoproteome in different cell types and cellular contexts is still limited and many questions remain regarding the precise roles of protein S-nitrosylation and denitrosylation. Here we present a novel strategy to identify reversibly nitrosylated proteins. Our approach is based on nitrosothiol capture and enrichment using a thioredoxin trap mutant, followed by protein identification by mass spectrometry. Employing this approach, we identified more than 400 putative nitroso-proteins in S-nitrosocysteine-treated human monocytes and about 200 nitrosylation substrates in endotoxin and cytokine-stimulated mouse macrophages. The large majority of these represent novel nitrosylation targets and they include many proteins with key functions in cellular homeostasis and signaling. Biochemical and functional experiments in vitro and in cells validated the proteomic results and further suggested a role for thioredoxin in the denitrosylation and activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase and the protein kinase MEK1. Our findings contribute to a better understanding of the macrophage S-nitrosoproteome and the role of thioredoxin-mediated denitrosylation in nitric oxide signaling. The approach described here may prove generally useful for the identification and exploration of nitroso-proteomes under various physiological and pathophysiological conditions.

Protein S-nitrosylation, the covalent addition of a nitric oxide (NO)1 group to a cysteine thiol, constitutes a widespread regulatory mechanism involved in various biological processes, such as control of cell growth, metabolism, differentiation, and apoptosis (1–4). S-nitrosylation is known to modulate the functional properties of a large number of proteins and thereby influence normal cell function and emerging evidence implicates aberrant protein S-nitrosylation in multiple pathological conditions, including cardiovascular disease, neurodegeneration, and cancer (5, 6). Although significant advances have been made in the field of S-nitrosylation, there is still limited knowledge regarding the constituents of the proteome that become nitrosylated (that is, the nitrosoproteome) across different cell types and conditions. Therefore, much remains unknown about the specific roles and functional significance of S-nitrosylation in cellular function and disease. In addition, there is a need to better understand the mechanisms and consequences of denitrosylation, both for individual proteins and on a systems level.

Protein denitrosylation is substantially mediated by two cellular denitrosylating systems, namely the glutathione and S-nitrosoglutathione reductase (GSH/GSNOR) and the thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase (Trx/TrxR) systems, with the latter representing a direct mechanism of protein denitrosylation (7–11). Trx/TrxR-mediated denitrosylation has been specifically linked to several cellular processes, including apoptosis (7), cell adhesion (12), exocytosis (13) and heme protein maturation (14). Despite recent progress in characterizing protein nitrosylation and denitrosylation, the dynamic cellular nitrosoproteome remains relatively unexplored, particularly under physiologically relevant conditions. This may be in part because of methodological challenges inherent to the proteomic analysis of S-nitrosylation and denitrosylation (See Discussion and (15–17)).

The disulfide and nitrosothiol (SNO) reductase activities of Trx depend on a highly conserved Cys-Gly-Pro-Cys active site (8, 18). Recent evidence suggests that, similar to reduction of disulfides, SNO reduction occurs in a two-step mechanism (7, 8). First, the more N-terminal cysteine (Cys32 in human Trx1) attacks the sulfur atom on the SNO moiety of the substrate protein, thereby displacing NO (formally, NO−) and generating an intermolecular disulfide between Trx and the substrate. The second step entails an intramolecular attack by the second active site cysteine (Cys35, known as the “resolving cysteine”) on the mixed disulfide intermediate, thus releasing the reduced target protein and the oxidized Trx. The normally transient disulfide intermediate formed in the first step is stabilized in a reaction that involves a Trx mutant that lacks the resolving cysteine. This so-called “trap mutant” has been employed in the identification of disulfide targets of Trx in several cell systems (19–22). However, the utility and value of such a trapping approach in the context of nitrosylation proteomics has not been evaluated.

In this study we adapted the Trx trapping strategy for global profiling of cellular nitrosylation and denitrosylation processes. Using this approach, we report the identification of hundreds of potential new nitrosylated targets in monoctyes and macrophages, followed by validation using biochemical and functional assays. The findings presented herein greatly expand our knowledge of the monocyte and macrophage nitrosoproteome and suggest multiple roles for nitrosylation and denitrosylation in macrophage activation and function. The approach employed in this study may be applied to exploring nitrosoproteomes in different cells and under various physiological and pathological conditions.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies and Reagents

The following antibodies were used throughout this study. Anti-Trx1 (catalogue number 559969) was from BD Biosciences. Anti-ERK1/2 (sc-94), anti-phosphorylated ERK1/2 (sc-7383), anti-MEK-1 (sc-219), anti-STAT3 (sc-483), and anti-iNOS (sc-651) were from Santa-Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-PRMT-1 (2453) was from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Anti-TrxR (ab-16840) was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Polyclonal anti-PA28β and monoclonal anti-GFP antibody were a kind gift of Ariel Stanhill (Technion, Haifa, Israel). Auranofin, a TrxR inhibitor, was from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY). 1400W, an iNOS inhibitor, was from Cayman Chemical Co (Ann Arbor, MI). Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was from Carlo Erba Reagents (Milan, Italy). ATP and NADPH were from Roche Diagnostics. S-Nitrosocysteine (CysNO) was synthesized by combining an equimolar concentration of l-cysteine with sodium nitrite in 0.2 N HCl and used within 1 h. A plasmid encoding for human Trx (wild-type and Cys mutants), dually tagged with His6 and streptavidin binding peptide (SBP) in pQE60 expression vector was kindly provided by Tobias Dick (German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany). His6-MEK1 in pRSETA vector and MEK1 fused to a green fluorescent protein (GFP-MEK1) in pEGFP-N1 vector were kindly provided by Rony Seger (Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel). His6-ERK1 in pET15b vector was kindly provided David Engelberg (the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel). Human TrxR1 (GenBank accession number BC018122, IMAGE clone ID 3883490) in the vector pCMV-SPORT6 was from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Recombinant rat TrxR1 (specific activity of 28 units/mg) was kindly provided by Elias Arnér (Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden). Recombinant mouse interferon-γ was from R&D systems. Tissue culture media and reagents were from Biological Industries (Beit Haemek, Israel). Other materials were obtained from Sigma unless otherwise indicated.

Cell Culture, Transfection and Treatment

Human embryonic kidney 293 cells (HEK293 cells) and RAW264.7 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin and streptomycin at 37 °C under 5% CO2. THP-1 cells were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin and streptomycin at 37 °C under 5% CO2. HEK293 cells were transfected using jetPEI (PolyPlus) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Typically, cells grown in 10 cm plates were transfected with a total of 20 μg DNA. In co-transfection assays, equal amount of plasmid DNA was used for each of the different plasmids. Where necessary, the DNA was kept constant by using the corresponding empty vector. Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed 48 h after transfection. In experiments that assessed MEK/ERK activity, cells were serum starved (0.1% serum) for 16 h prior to stimulation. In experiments involving induction or overexpression of iNOS, 1 mm l-arginine was added to the culture medium.

Generation of Cell Lines Expressing Tetracycline-inducible WT Trx and Trx(C35S)

A tetracycline-regulated expression system (T-Rex system; Invitrogen) was used. cDNAs of GST-Trx1(WT) and GST-Trx(C35S) were subcloned from a pEBG vector (23) into a pcDNA4/TO vector. The pcDNA4/TO constructs were transfected into a HEK293 cell line stably expressing the Tet repressor from pcDNA6/TR plasmid (T-Rex-293). T-Rex-293 cell lines stably expressing tetracycline-inducible GST-Trx1(WT) and GST-Trx(C35S) in pcDNA4/TO were generated by dual selection using zeocin (250 μg/ml) and blasticidin (5 μg/ml). The expression levels of GST-Trx1(WT) and GST-Trx(C35S) were assayed by immunoblotting at 24 h and 48 h after addition of tetracycline (1.5 μg/ml). Clones that showed high, comparable expression levels of GST-Trx1(WT) and GST-Trx(C35S) and tight control by tetracycline were used in this study.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

His-tagged proteins (Trx1, MEK1 and ERK1) were expressed and purified from Escherichia coli BL21 cells using nickel affinity chromatography. In brief, BL21 cells expressing His-tagged proteins were cultured in 500 ml of LB and induced by the addition of isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (0.5 mm) for 3–4 h at 37 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, resuspended in 10 ml of extraction buffer (300 mm KCl, 50 mm KH2PO4, 5 mm imidazole, with protease inhibitors, pH 7.4), and disrupted by ultrasonication. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was applied to nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (Thermo Scientific) overnight at 4 °C. The beads were washed with extraction buffer containing imidazole (10 mm), and finally, the protein was eluted with 250 mm imidazole. Elution fractions were dialyzed overnight in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.5). Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, pooled, and stored at −80 °C. Protein purity was at least 95% as judged by SDS-PAGE.

Thioredoxin-based Substrate Trapping

The trapping procedure was based on the protocol described by Schwertassek et al. (22). In brief, after various treatments, THP-1 or RAW264.7 cells were harvested and permeabilized by incubation with 0.01% digitonin in Tris-buffered saline (TBS, pH 7.5) for 10 min at 4 °C on a rotating wheel, followed by centrifugation for 15 min at 4 °C to clear the lysate. In parallel, streptavidin agarose beads (Thermo Scientific) were loaded with recombinant Trx proteins (50 μg) in the presence of 20 mm DTT for 1 h at 4 °C and subsequently washed to remove the reductant. The beads were then incubated with supernatants of digitonin-permeabilized cells (∼3 mg protein) for 1 h at 4 °C. In selected cases, prior to this step, cell lysates were exposed to UV light to photolyze SNO bonds as described elsewhere (24). The trapping reaction was quenched with N-ethyl maleimide (NEM, 100 mm) for 15 min at room temperature and thereafter the beads were washed extensively at 4 °C as follows: twice in TBS containing 1% Triton X-100, 10 mm NEM, and 1 m NaCl (pH 7.5), once with TBS containing 1% Triton X-100, 10 mm NEM, once with TBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (pH 7.5), and twice with TBS (pH 7.5). Trapped proteins were eluted with 100 mm DTT in TBS (pH 7.5) for 30 min at room temperature and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Gels were stained with Krypton Infrared Protein Stain (Pierce, Waltham, MA) and proteins visualized using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LICOR Biosciences, Cambridge, UK). For proteomic analysis the above procedure was scaled-up 4-fold.

Mass Spectrometry

Samples representing equal amounts of starting material were separated by a short SDS-PAGE run and the gel was subsequently stained with Coomassie Blue. After staining, the stained gel lanes were sliced to two pieces and the gel slices were processed for in-gel tryptic digestion. The proteins in the gel were reduced with 2.8 mm DTT for 30 min at 60 °C, modified with 8.8 mm iodoacetamide in 100 mm ammonium bicarbonate in the dark for 30 min at room temperature, and digested with modified trypsin (Promega) in 10% acetonitrile and 10 mm ammonium bicarbonate at a 1:10 enzyme-to-substrate ratio overnight at 37 °C. The resulting tryptic peptides from the liquid phase were analyzed by LC-MS/MS using an Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) fitted with a capillary HPLC (Eksigent). The peptides were loaded in solvent A (0.1% formic acid in water) onto a C18 trap column (0.3 × 5 mm, LC-Packings) connected on-line to a homemade capillary column (75 micron ID) packed with Reprosil C18-Aqua (Dr Maisch GmbH, Germany). The peptide mixture was resolved using a (5 to 40%) linear gradient of solvent B (95% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) for 94 min, followed by 95% solvent B for 12 min, using a flow rate of 0.25 μl/min. Mass spectrometry was performed in a positive mode (m/z 350–2000, resolution 60,000) using repetitively full MS scan (measured in the Orbitrap detector) followed by collision-induced dissociation (CID, measured in the linear trap with 35% normalized collision energy) of the seven most intense ions (>1 charges) that were selected from the first MS scan. The AGC settings were 5 × 105 for the full MS and 1 × 104 for the MS/MS scans. The intensity threshold for triggering MS/MS analysis was 3 × 104. A dynamic exclusion list was enabled with exclusion duration of 30 s.

Data Analysis

The mass spectrometry raw data was analyzed by the MaxQuant software (version 1.4.1.2, http://www.maxquant.org) (25) for peak picking and quantitation, followed by identification using the Andromeda search engine, searching against the mouse UniProt database (release May 2013, 42901 entries) or the human UniProt database (release August 2013, 89676 entries) with mass tolerance of 20 ppm for the precursor masses and 0.5 Da for the fragment ions. Methionine oxidation, N-ethylmaleimide on cysteine, carbamidomethyl on cysteine, N-ethylmaleimide+H2O on cysteine or lysine and protein N terminus acetylation were set as variable post-translational modifications. Minimal peptide length was set to six amino acids and a maximum of two miscleavages was allowed. Peptide- and protein-level false discovery rates (FDRs) were filtered to 1% using the target-decoy strategy. Protein tables were filtered to eliminate the identifications from the reverse database and from common contaminants. The maximum posterior error probability (PEP) for peptides was set to 1 and at least two unique peptides were required for protein identification. Sets of protein sequences which could not be discriminated based on identified peptides were listed together as protein groups and are fully reported in the supplemental Tables S1 and S2 (each row in the tables contains the group of proteins, referred to by their proteins IDs, that could be reconstructed from a set of peptides including homologous proteins that do not have an additional unique peptide) (25). The MaxQuant software was used for label-free semi-quantitative analysis, based on extracted ion currents (XICs) of peptides enabling quantitation from each LC/MS run for each peptide identified in any of experiments. Briefly, for every peptide, corresponding total signals from multiple runs were compared with determine peptide ratios. Pair-wise peptide ratios were only determined when the corresponding peak was detected in both LC-MS runs. A robust estimation of the protein ratio was calculated as the median of pair-wise peptide ratios interpolated with the square root of the ratio of summed-up intensities. The analysis, performed using the MaxQuant platform, was done after recalibration of the retention times. Only proteins that were identified with at least two peptides in one of the samples are listed in Tables S1 and S2. The missing intensity values (those below background levels) were replaced with an arbitrary value of 10000. Maximum ratio (between sample intensities) was limited to 100 and higher ratios were replaced with 100. The obtained values were log2 transformed. Proteins were considered to represent putative nitrosylation targets if their corresponding log2 ratio was >1 when comparing the CysNO or LPS/IFN-γ samples to their respective controls, in both replicate experiments. To assess functional enrichment, the lists of putative nitrosylation targets were submitted to GeneCodis (26), a web-based tool for the ontological analysis of large lists of genes and proteins. GeneCodis assesses if an input list of proteins results in combinations of annotations that are significantly enriched. For this analysis, the GO Biological Process was selected. “Fold enrichment” was defined as the number of proteins detected in the sample compared with the total number of proteins expected in the mouse or human proteome in each GO biological process.

Detection of Protein S-nitrosylation

Detection of S-nitrosylation was performed using the SNO-RAC method (27) with minor modifications as follows. In brief, cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mm Hepes, 1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1 mm diethylenetriamine pentaacetate, 50 mm NEM with protease inhibitors, pH 7.5). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 13,000g for 15 min at 4 °C. A total of 3 mg of protein was used for each experimental condition. Thiol blocking with 40 mm NEM was performed for 30 min at 50 °C with frequent vortexing. To remove excess NEM, proteins were precipitated with three volumes of acetone at −20 °C for 20 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 5000g for 5 min and the pellet was washed three times with three volumes of 70% acetone and resuspended in HENS buffer (100 mm Hepes, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1 mm neocuproine, and 1% SDS, pH 7.7). The resuspended samples were added to 80 μl thiopropyl Sepharose resin (GE Healthcare) in the presence or absence of sodium ascorbate (final concentration 40 mm). Samples were rotated in the dark for 1.5 h at room temperature and then overnight at 4 °C. Thereafter, the resin was washed four times with 1 ml of HENS buffer and twice with 1 ml of HENS/10 buffer (HENS diluted 1:10). Captured proteins were eluted with 30 μl HENS/10 containing 100 mm 2-mercaptoethanol for 20 min at room temperature and analyzed by Western blotting using specific antibodies. Protein bands were detected and quantified with the Odyssey system.

MEK1 Activity Assay

HEK293 cells, transfected with GFP-MEK1, were maintained in 0.1% serum for 16 h and then stimulated with EGF (50 ng/ml) for 5 min. Thereafter, the cells were washed, lysed, and immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP antibody coupled to protein A-agarose beads (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed with buffer A (50 mm β-glycerophosphate, 1.5 mm EGTA, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1 mm sodium vanadate, pH 7.3) then with 50 mm Hepes, 150 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100 (pH 7.5), and twice with 0.5 m LiCl in 0.1 m Tris (pH 8.0). Where indicated, the MEK1 pull-down was treated with 500 μm CysNO for 15 min and then washed three times with buffer A. Thereafter, the beads were incubated with 30 μl of reaction mix (30 mm MgCl2, 75 mm β-glycerolphosphate, 0.15 mm sodium vanadate, 3.75 mm EGTA, pH 7.3) supplemented with 0.1 mm ATP and 0.5 μg recombinant ERK1 for 10 min at 30 °C. Finally, phosphorylation of ERK was determined by immunoblotting with a phospho-specific ERK antibody. Prior to the assay, the ERK1 substrate was dephosphorylated by treatment with lambda protein phosphatase (BioLabs) for 30 min at 30 °C.

Assessment of the Interaction of MEK1 with Trx in vitro

Recombinant MEK1 (50 μg) was treated with 50 mm DTT for 20 min at room temperature and then incubated with or without CysNO (500 μm) for 15 min at room temperature. After each step, excess DTT or CysNO was removed by Amicon Ultra-0.5 ml centrifugal filters (3 kDa cutoff) according to the manufacturer's protocol (Millipore). Thereafter, MEK was incubated with 50 μg Trx(C35S) for 1 h at 4 °C. After pull-down with streptavidin beads and elution with DTT (50 mm, 30 min), the samples were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MEK1 antibody.

Coimmunoprecipitation of MEK1 with Trx

HEK293 cells that stably express Trx(C35S) were transfected with GFP-MEK1 and iNOS or empty vector for 48 h. Tetracycline (1.5 μg/ml) was added 24 h post-transfection to induce expression of Trx(C35S). Then, the cells were treated with or without CysNO (500 μm) and lysed with buffer A. Lysates were incubated with anti-GFP antibody coupled to Protein A-agarose. After pull-down, the beads were treated with 50 mm DTT for 30 min at room temperature and supernatants were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-Trx1 antibody.

Immunodepletion of Trx

Anti-Trx1 antibody (10 μg) was incubated with protein A-agarose beads in PBS for 1 h at 4 °C. Antibody-bound beads were washed three times with PBS to remove unbound antibody. Freshly prepared HEK293 cell extracts (1 mg in 0.5 ml volume) was added to the beads and incubated with constant rotation for 1 h at 4 °C. The beads were pelleted at 1000 × g for 2 min and the supernatants were removed and used for determination of iNOS activity.

iNOS Activity Assay

After cell transfection and/or treatment as described in figure legends, cells were lysed with 0.01% digitonin in PBS. A total of 150 μg protein per sample was used to determine iNOS activity employing a NOS colorimetric assay kit (Oxford Biomedical Research) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, lysates were incubated with l-arginine and NADPH for 2 h at 37 °C. Thereafter, nitrate reductase was added and samples were incubated for 20 min at room temperature, prior to quantitation of nitrite using Griess reagent.

RESULTS

Thioredoxin-mediated Trapping of Cellular Nitrosylated Proteins

Previously, we used the Trx trapping mutant, Trx(C35S), to demonstrate a nitrosylation-dependent interaction between Trx and a particular substrate, caspase-3 (7). Here, we investigated the applicability of a trapping-based strategy for identification and analysis of cellular nitrosylated proteins. To this end, we used recombinant human Trx proteins, either wild-type (WT) or the C35S mutant, each harboring a C-terminal dual affinity tag composed of a streptavidin-binding peptide (SBP) and a hexahistidine tag. In these Trx proteins, the three non-catalytic cysteines (residues 62, 69 and 73) were replaced with alanine in order to prevent thiol-disulfide exchange reactions during the trapping procedure (22).

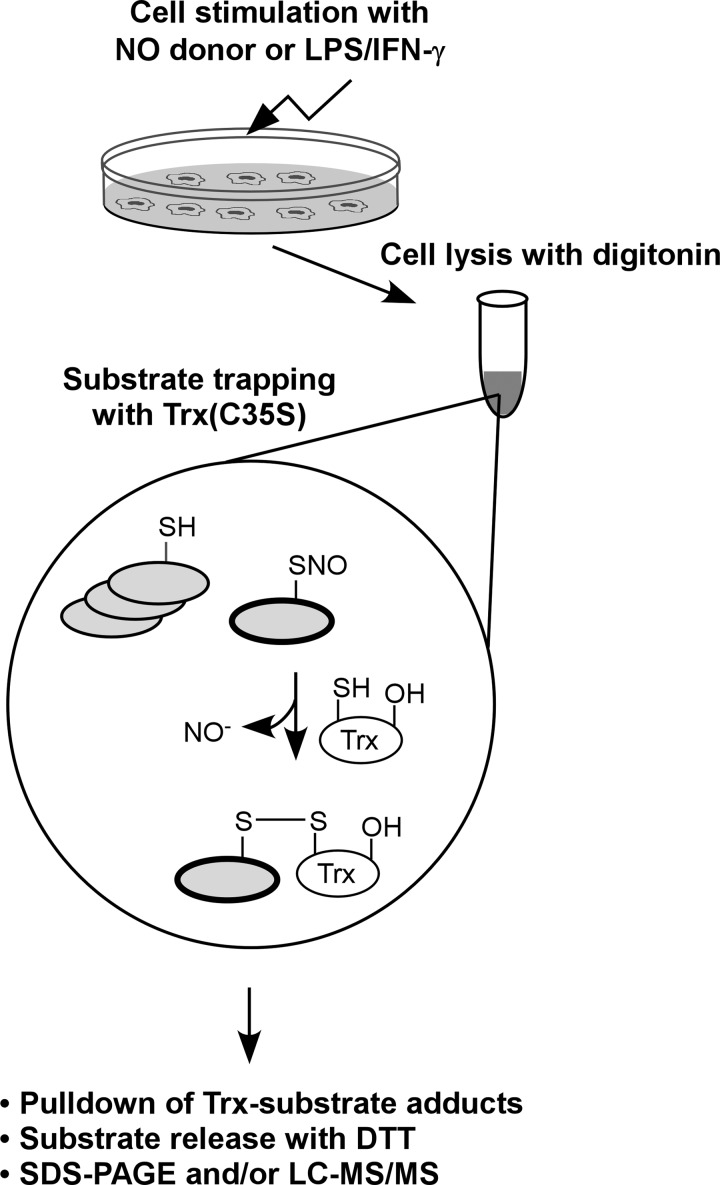

In the tapping experiments that follow we used two cell-based systems: THP-1 human monocytic cells exposed to exogenous NO/SNO donor and RAW264.7 murine macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide plus interferon-γ (LPS/IFN-γ), hereafter respectively referred to as the “THP system” and the “RAW system”. The trapping procedure is schematically depicted in Fig. 1 and detailed under “Experimental Procedures.” In brief, cytosol-enriched fractions were prepared from untreated and treated cells and in parallel Trx proteins (WT or C35S) were coupled to avidin agarose. Thereafter, the cell lysates were incubated with Trx proteins under native conditions. After extensive washing steps, proteins captured by Trx were pulled down, released with DTT, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the substrate-based identification of S-nitrosylated proteins. Digitonin cell lysates, obtained from monocytes/macrophages treated with a nitric oxide (NO) donor or lipopolysaccharide plus interferon-γ (LPS/IFN-γ), are incubated with a thioredoxin (Trx) trap mutant, Trx(C35S). In the trap mutant the resolving cysteine is replaced by serine (-OH). The protein also contains a streptavidin binding tag (not shown). Trx(C35S) forms mixed disulfide bonds with nitrosylated substrates and the resulting complexes are pulled-down using avidin agarose. Captured proteins are released from the complex with dithiothreitol (DTT) and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE or liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

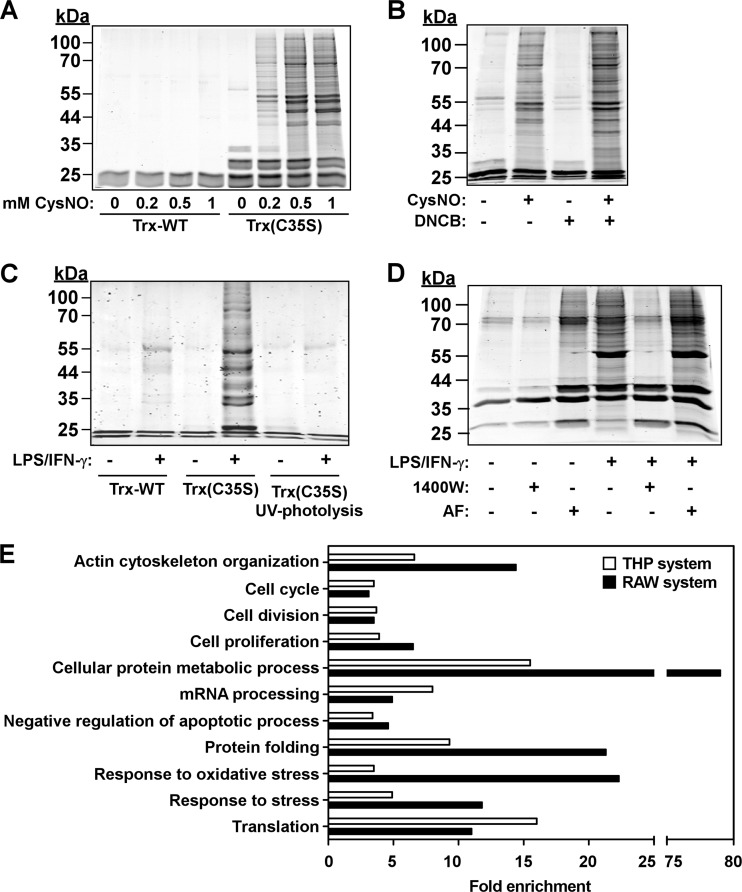

Employing this procedure, we found that Trx(C35S), but not Trx-WT, pulled down many THP-1 proteins and that this apparent protein trapping was increased with increasing concentrations of CysNO (200–1000 μm) (Fig. 2A). Despite these initial promising results we suspected that the endogenous Trx system may limit the number of trapped proteins because it may (1) rapidly denitrosylate cellular proteins prior to the trapping step, or (2) cleave the disulfide formed between Trx(C35S) and target proteins during the trapping step. Consistent with this notion, pretreatment of cells with the TrxR inhibitor 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (DNCB) resulted in a marked increase in the number and amount of proteins pulled down by Trx(C35S) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Thioredoxin-mediated trapping of cellular nitrosylated proteins. A, THP-1 cells were treated with or without S-nitrosocysteine (CysNO) for 15 min and thereafter digitonin lysates were incubated with Trx proteins. Proteins captured by Trx were released by DTT and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Gels were stained with Krypton fluorescent protein stain and visualized using the Odyssey infrared imaging system. B, THP-1 cells were treated with or without the TrxR inhibitor DNCB (10 μm, 1 h) followed by exposure to CysNO (200 μm, 15 min). Trx(C35S)-mediated capture of cellular proteins was performed as in A. C, RAW264.7 cells were treated with or without lipopolysaccharide plus interferon-γ (LPS/IFN-γ) for 16 h and analyzed for Trx(C35S)-mediated trapping as in A. Where indicated, lysates were exposed to UV light prior to incubation with Trx. D, RAW264.7 cells were treated with LPS/IFN-γ for 16 h with or without the iNOS inhibitor 1400W (16 h, 100 μm) or the TrxR inhibitor auranofin (AF, 2 μm added for the final 1 h). Protein captured by Trx(C35S) were analyzed as in A–C. E, Overrepresented Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes among the identified candidate nitroso-proteins. Shown are enriched processes that are common to both the THP and RAW systems (see Experimental Procedures for details). Proteins were classified into different categories based on GO annotations and using the Genecodis algorithm (26) (see also supplemental Table S5).

We considered the possibility that the observed substrate trapping was due not only to thiol S-nitrosylation but also to thiol S-oxidation (mainly disulfides). However, exposure of the cell lysates to UV light, which photolytically cleaves NO groups from SNOs, effectively abolished CysNO-induced protein trapping (supplemental Fig. S1A). In addition, cell treatment with H2O2 elicited very little trapping, even at a much higher concentration compared with CysNO (2 mm versus 0.2 mm) (supplemental Fig. S1B). Together, these data suggested that, under conditions of elevated cellular NO/SNO, Trx(C35S) trapped mainly S-nitrosylated proteins rather than S-oxidized proteins.

Next, we examined the applicability of the trapping approach in the context of inducible NO synthase (iNOS)-dependent S-nitrosylation, specifically in RAW264.7 macrophages stimulated with LPS/IFN-γ. We found that Trx(C35S) pulled down very few proteins from resting macrophages but captured multiple proteins from stimulated macrophages (Fig. 2C). As in the THP system, here too, trapping was practically negligible when employing Trx-WT or UV-irradiated samples (Fig. 2C). Additional experiments showed that cell exposure to the TrxR inhibitor auranofin (AF), either alone or in combination with LPS/IFN-γ, increased the number of trapped proteins and, conversely, treatment with 1400W, a specific iNOS inhibitor, markedly decreased protein trapping (Fig. 2D). Overall, the results obtained in the two cell systems point to the trapping approach as being useful for general profiling of endogenous nitrosylation events.

Large-Scale Identification of Candidate S-Nitrosylated Proteins

We proceeded to identify specific proteins captured by Trx(C35S) by coupling the trapping protocol with mass spectrometry (MS)-based analysis. In the THP system we used the following experimental conditions: (1) control, (2) CysNO, (3) DNCB, and (4) DNCB plus CysNO. Two biological replicates of enriched proteins were in-gel digested and analyzed using a nano-LC-LTQ Orbitrap mass spectrometer platform. MS/MS analysis of the gel slices allowed identification of over 500 proteins with at least two distinct peptides and a false discovery rate (FDR) below 1%, with 488 proteins being identified in both replicate experiments (all identified proteins and peptides are listed in supplemental Tables S1A and S1B; see also supplemental Fig. S2). Only proteins that were identified in both experiments were considered for further analyses. Ranking by the total number of unique peptides and proteins identified in each sample clearly indicated that substrate trapping was CysNO-dependent, with the largest number of identified peptides and proteins found in the DNCB/CysNO sample. This trend agreed with the results of our gel-based analysis noted above (see Fig. 2B). To better assess CysNO dependence, a semi-quantitative analysis was performed using the MaxQuant software (25) (see Experimental Procedures and supplemental Tables S1A and S1B). Based on this analysis and using a threshold of 2-fold change, trapping of 447 proteins (corresponding to 91% of total) was determined to be CysNO-dependent. We consider these proteins to represent putative nitrosylation targets.

In the RAW system we employed MS to analyze Trx-mediated trapping from untreated and LPS/IFN-γ-challenged cells. Across two biological replicates we identified in the Trx pull-down over 200 proteins with 192 proteins being identified in both replicate experiments (supplemental Tables S2A and S2B; supplemental Fig. S2). Noteworthy, semi-quantitative analysis of the MS data (as above) revealed that trapping of nearly all of these proteins (190 out of 192) was LPS/IFN-γ-dependent. Of further note, the human homologs of nearly half of the proteins within the RAW data set were also included in the THP data set. These common targets (listed in supplemental Table S3) may represent a set of proteins highly susceptible to undergo S-nitrosylation.

The MS data sets contained about two dozen proteins that were previously shown to be regulated by S-nitrosylation, including CDK2 and 5, HDAC2, exportin-1/CRM1, and EGLN1/PHD2 (see supplemental Table S4). Detection of these proteins supports that validity of the proteomic approach and raises the idea that Trx functionally regulates these proteins. Also validating the proteomic results, we identified several known S-nitrosylated substrates of Trx, including caspase-3 (7), GAPDH (7, 13, 14), and NF-κB (28). Importantly, however, the large majority of proteins identified in both the THP and RAW systems have not been previously shown to be modified by S-nitrosylation, thus representing potential novel S-nitrosylated proteins. By virtue of the method employed, the data also suggest that denitrosylation of these proteins can be mediated by Trx.

To gain insight into the cellular processes that are mostly affected by reversible nitrosylation we submitted the lists of putative nitrosylated targets to gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis using GeneCodis program (26). We identified 18 GO biological processes as being significantly enriched in the RAW data set (FDR corrected p value < 0.01, chi-square test) (supplemental Table S5). Eleven of those were also enriched in the THP-1 data set, which may point to cellular processes tightly regulated by reversible nitrosylation, including translation, cell division and proliferation, and cytoskeleton organization (Fig. 2E and supplemental Table S5). This analysis also revealed differences between the RAW and THP systems. For example, the GO biological processes “innate immune response” and “glycolysis” were found to be enriched in the RAW system but not in the THP system, and, conversely, the terms “purine nucleotide biosynthetic process” and “RNA splicing” were enriched in the THP system but not in the RAW system (supplemental Table S5).

Validation of the Proteomic Findings

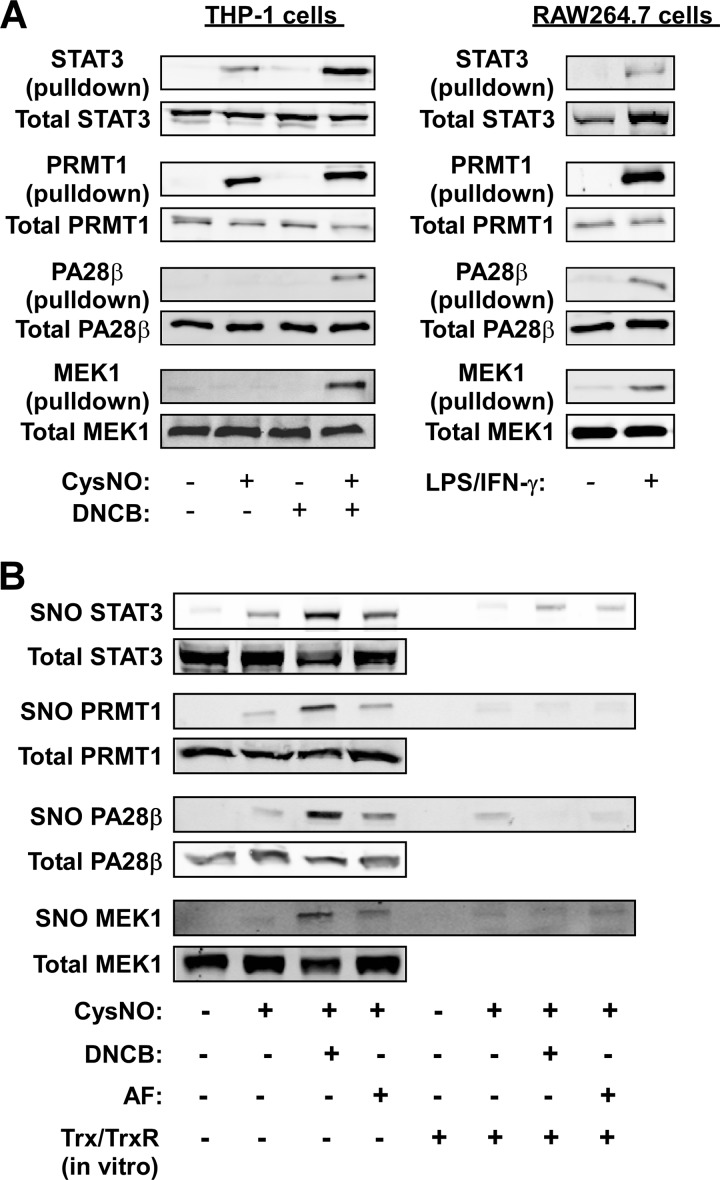

To further evaluate and validate the proteomic results we focused on four proteins that were identified in either or both of the cell systems, specifically, the transcription factor STAT3, the arginine methyltransferase PRMT1, the proteasomal regulator, PA28β, and the protein kinase, MEK1. Using the trapping procedure we found that Trx(C35S) pulled-down STAT3 and PRMT1 from THP-1 cells exposed to CysNO, and that this trapping was augmented by DNCB (Fig. 3A). In the case of PA28β and MEK1, significant trapping was observed only after co-treatment of cells with CysNO and DNCB (Fig. 3A). In the RAW system, Trx(C35S) pulled-down all four proteins in a LPS/IFN-γ-dependent manner (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Validation of proteomic results for selected proteins. A, THP-1 or RAW264.7 cells were exposed to different treatments and subjected to the trapping procedure as described in Fig. 1 and 2. The presence of STAT3, PRMT1, PA28β and MEK1 in the Trx pull-down was determined by immunoblotting. B, THP-1 cells were treated with or without the TrxR inhibitors 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (DNCB, 10 μm) or auranofin (AF, 2 μm) for 1 h followed by incubation with CysNO (500 μm) for 30 min. Thereafter, cell lysates were incubated with or without a recombinant Trx system (5 μm Trx, 0.1 μm TrxR, 200 μm NADPH) for 20 min at 37 °C. Nitrosylation of STAT3, PRMT1, PA28β and MEK1 was determined by resin-assisted capture (SNO-RAC).

These above results implied that endogenous STAT3, PRMT1, PA28β and MEK1 were subject to Trx-regulated S-nitrosylation. To verify this further, we assayed nitrosylation of the proteins in THP-1 cells treated with CysNO in the absence or presence of TrxR inhibitors. Using the SNO-RAC method (27) we found that all four proteins were nitrosylated to varying degrees in CysNO-treated cells and that nitrosylation was enhanced by DNCB or AF (Fig. 3B). Moreover, incubating the cell lysates with recombinant Trx system resulted in denitrosylation of all four proteins (Fig. 3B). These proteins were also nitrosylated in RAW264.7 cells stimulated with LPS/IFN-γ and became denitrosylated upon incubation of cell lysates with the Trx system (supplemental Fig. S3). These data strongly suggest that STAT3, PRMT1, PA28β and MEK1 are S-nitrosylated targets of Trx.

Regulation of MEK1 by S-Nitrosylation

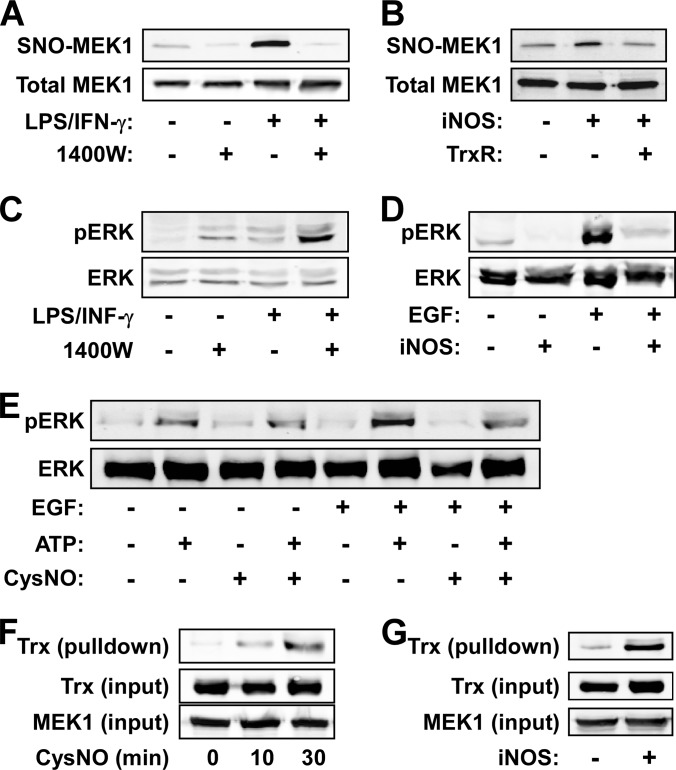

We proceeded to characterize in greater detail the nitrosylation and denitrosylation of MEK1, an essential kinase in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade (29). As shown in Fig. 4A, nitrosylation of MEK1 in macrophages was dependent on iNOS activity as it was abolished by 1400W. Consistent with this finding, overexpression of iNOS in HEK293 cells also induced the nitrosylation of MEK1 (Fig. 4B). Notably, coexpression of TrxR in this setting reversed the nitrosylation (Fig. 4B). In a time-course experiment we found that overexpression of TrxR accelerated the denitrosylation of MEK1 after cell exposure to CysNO (see 20 min time point, supplemental Fig. S4A). These data thus show that MEK1 can be nitrosylated by both endogenous and exogenous sources of NO and that the Trx system mediates its denitrosylation.

Fig. 4.

Regulation of MEK by S-nitrosylation. A, RAW264.7 cells were treated for 16 h with LPS/IFN-γ in the presence or absence of the iNOS inhibitor 1400W. Nitrosylation of MEK1 was assessed by SNO-RAC. B, HEK293 cells were transfected for 48 h with inducible NO synthase (iNOS) and/or Trx reductase 1 (TrxR1) and nitrosylation of MEK1 was determined by SNO-RAC. C, RAW264.7 cells were treated for 16 h with LPS/IFN-γ in the presence or absence of 1400W. Phosphorylation of ERK was determined by immunoblotting with a phospho-specific ERK antibody. D, HEK293 cells were transfected with iNOS or control DNA for 48 h and then stimulated for 5 min with epidermal growth factor (EGF, 50 ng/ml). Phosphorylation of ERK was determined by immunoblotting. E, HEK293 cells were transfected with GFP-MEK1 for 48 h and then stimulated with EGF. MEK1 was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates, exposed to vehicle or CysNO (500 μm, 15 min), and finally assayed for ERK phosphorylation. F, HEK293 cells that express Trx(C35S) under the control of tetracycline were transfected with GFP-MEK1 and after 48 h treated with CysNO (500 μm). Whole-cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-GFP antibody. The presence of Trx in the MEK1 pull-down was determined by immunoblotting. G, HEK293 cells that express Trx(C35S) were transfected for 48 h with GFP-MEK1 and iNOS or control DNA. The interaction of Trx with MEK1 was assessed as in F.

To examine if nitrosylation influences MEK1 function we analyzed the effect of exogenous or endogenous NO/SNO on stimulus-dependent phosphorylation of the MEK substrate, ERK. In macrophages, LPS/IFN-γ-induced activation of ERK was augmented by 1400W (Fig. 4C) possibly implying that endogenous NO/SNO inhibits MEK1 activity. Concordant with this notion, transfection of iNOS to HEK293 cells suppressed epidermal growth factor (EGF)-induced ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 4D), and this was correlated with diminished MEK1 activity (supplemental Fig. S4B). Furthermore, overexpression of TrxR partially reversed the iNOS-dependent inhibition of ERK phosphorylation (supplemental Fig. S4C). Similar to the effect of iNOS, brief exposure of HEK293 cells to CysNO abrogated EGF-dependent ERK phosphorylation (supplemental Fig. S4D). Finally and importantly, CysNO treatment of MEK1, which was immunopurified from EGF-stimulated cells, inhibited its kinase activity in vitro (Fig. 4E). Thus, the suppressive effects of NO/SNO on ERK phosphorylation appear to be mediated by inhibitory S-nitrosylation of MEK1.

In light of these results we examined if MEK1 and Trx interacted in a cellular context using HEK293 cells in which expression of Trx(C35S) was controlled by tetracycline. Cell transfection with MEK1 coupled to pull-down experiments revealed that MEK1 interacted with Trx(C35S) and that this interaction was dependent on treatment of cells with CysNO or expression of iNOS (Figs. 4F and 4G). SNO-dependent interaction was confirmed with purified recombinant MEK1 and Trx(C35S) (supplemental Fig. S4E), suggesting a direct interaction between these two proteins. Put together, our data support the conclusion that Trx functionally regulates MEK1 by means of denitrosylation.

Regulation of iNOS by Thioredoxin

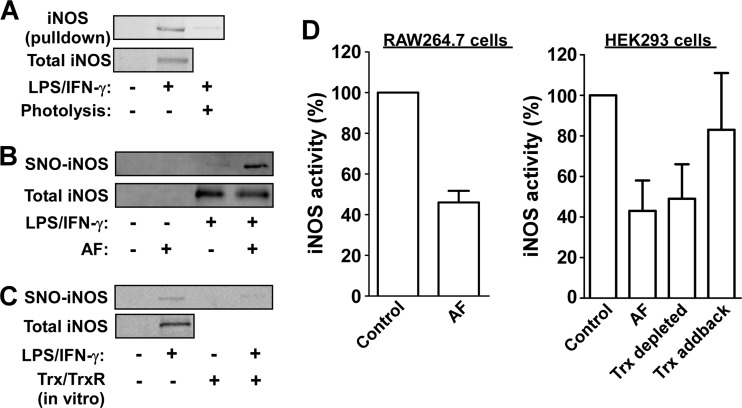

Our proteomic analysis identified iNOS, a major source of NO/SNO produced by macrophages, as a potential target of Trx (supplemental Tables S2A and S2B). Previous studies have shown that iNOS is inactivated by S-nitrosylation and that GSH can promote its denitrosylation (30–32). However, whether Trx also regulates iNOS nitrosylation and activity is unknown. In line with the proteomic results we found that Trx(C35S) pulled-down iNOS from RAW264.7 cells that were stimulated with LPS/IFN-γ (Fig. 5A). Further, iNOS trapping was prevented by UV pretreatment of the lysates (Fig. 5A). In addition, we found that endogenous iNOS nitrosylation was augmented by treatment of cells with AF while it was reversed by treatment of cell lysates with Trx/TrxR (Fig. 5B and 5C). These data suggest that Trx/TrxR mediate iNOS denitrosylation.

Fig. 5.

Regulation of iNOS nitrosylation and activity by thioredoxin. A, Lysates derived from RAW264.7 cells were either untreated or SNO-photolyzed and then subjected to the trapping procedure as described in Figs. 1–3. The presence of iNOS in the Trx pull-down was determined by immunoblotting. B, RAW264.7 cells were treated with LPS/IFN-γ in the absence or presence of the TrxR inhibitor auranofin (AF, added for the final 1 h). Nitrosylation of iNOS was determined by SNO-RAC. C, RAW264.7 cells were either left untreated or stimulated with LPS/IFN-γ. Thereafter, cell lysates were incubated with or without a recombinant Trx system (5 μm Trx, 0.1 μm TrxR, 200 μm NADPH) for 20 min at 37 °C. Nitrosylation of iNOS was determined using SNO-RAC. D, Cell extracts, derived from LPS/IFN-γ-stimulated RAW264.7 cells or HEK293 cells transfected with iNOS, were incubated with NADPH and l-arginine in the presence or absence of AF. Where indicated, Trx was specifically immunodepleted from the lysate using anti-Trx antibody. For the addback sample, after immunodepletion, recombinant Trx was added to a final concentration of 5 μm. The activity of iNOS in the different samples was determined by measuring nitrite/nitrate accumulation. Results shown represent mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

We assessed if inhibition of Trx/TrxR affects iNOS activity, measured in lysates derived from stimulated macrophages or from iNOS-transfected HEK293 cells. Strikingly, we found that adding AF to the lysates resulted in over 2-fold reduction in iNOS activity (Fig. 5D). In a second approach, we observed that immunodepletion of Trx from cell lysates also lead to markedly reduced iNOS activity and that adding back recombinant Trx restored the activity (Fig. 5D). Altogether, these data suggest that Trx contributes to maintaining iNOS in a denitrosylated, active state.

DISCUSSION

Reversible S-nitrosylation is known to play important roles in normal cellular function and emerging evidence links dysregulated nitrosylation to cellular dysfunction (1–6). To date, proteome-level analysis of S-nitrosylation has mainly relied upon the biotin switch method (or adaptations of it) along with recent developments including the use of an organomercury resin for SNO enrichment (33) or the use of protein microarrays (34, 35). The strengths and caveats of these methods have been previously discussed (15–17, 36–39). Despite these technical advances, there is still limited knowledge regarding the number and identity of proteins that undergo nitrosylation and denitrosylation across tissue and cell types and under various physiological and pathological conditions. The low stoichiometry (or occupancy) of SNOs (∼ 1% of the thiol proteome in activated macrophages (40)) as well as their rapid turnover and labile nature presents a significant challenge for large-scale profiling of S-nitrosylation, particularly under physiologically relevant conditions. The challenge is even more daunting when considering the identification of low abundant proteins.

The substrate trapping approach presented here effectively enabled the identification hundreds of proteins that are candidates for regulation by S-nitrosylation and denitrosylation both in SNO-treated monocytes as well as in LPS/IFN-γ-stimulated macrophages. The inherent ability of Trx to recognize nitrosylated protein thiols among the vast majority of reduced thiols and the use of native conditions during the trapping and enrichment procedure are two factors that likely contribute to the effectiveness of the present method. Our data suggest that under conditions of increased levels of intracellular NO/SNO, Trx(C35S) captures mainly nitrosoproteins, whereas trapping of S-oxidized proteins is minimal. The sensitivity and strength of the current proteomic approach is supported by the finding that many of the targets identified in the THP and RAW systems are proteins that are endogenously expressed at low levels such as STAT3, NF-κB, and CDK5. In fact, ∼20% of the proteins in our data sets are known to be expressed at relatively low levels in human or mouse cells (41, 42).

Our THP and RAW data sets contain multiple proteins that are unique to one of the two systems (e.g. caspase-3 and iNOS being identified as SNO targets specific to the THP and the RAW systems, respectively) as well as a common set of proteins (supplemental Table S3). Identification of system-specific proteins is likely because of differences between the two types of cells and as well as to employing distinct activation states (affecting the expressed proteomes). Another important difference between the two systems is the source of NO, namely exogenous versus endogenous. Reassuringly, we identified about two dozen proteins whose activity was previously shown to be regulated by S-nitrosylation; however, for most of these SNO targets, the mechanism of denitrosylation was unknown. Proteins in this category included CDK2 and 5, EGLN1/PHD2, exportin-1 and peroxiredoxin 1 and 2 (supplemental Table S4) suggesting the possibility that Trx-mediated denitrosylation is involved in the regulation of processes such as cell cycle progression, hypoxia signaling, protein trafficking and peroxide metabolism.

Notwithstanding the above observations, it is important to emphasize that the majority of identified proteins (over 400) represent potentially novel nitrosylation targets. These targets are implicated in a wide range of cellular pathways and processes. Bioinformatics analysis applied to these target proteins uncovered several overrepresented cellular processes, such as protein translation and folding, cell division and proliferation, and ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation (Fig. 2E and supplemental Table S5). These results suggest extensive regulation of these processes by reversible S-nitrosylation and they may also help explain some of the known biological effects of NO, such as inhibition of protein translation (43) and modulation of proteasome function (44). We note that many of the proteins and pathways that we identified in the analysis of the macrophage nitrosoproteome overlap with the recently identified iNOS interactome (45) consistent with recent evidence that nitrosylation occurs in a localized manner and facilitated by protein-protein interactions (3, 46–49). Finally, although it remains to be investigated more thoroughly, we anticipate that most of the proteins identified here represent SNO substrates of Trx. As such, this study paves the way to a better understanding of the mechanisms and roles of Trx-mediated denitrosylation (8, 50).

The MEK/ERK pathway is a central signaling cascade that regulates a wide range of biological processes including innate immunity (51), but how it is regulated by NO remains obscure. Here, we showed that either exogenous or endogenous NO/SNO induced the nitrosylation MEK1 and blunted EGF-induced ERK activation. Similarly, endogenous NO inhibited LPS/IFN-γ-induced ERK activation. Importantly, we demonstrated that SNO directly inhibited the kinase activity of MEK1 and that Trx interacted with and denitrosylated MEK1. Together, these data suggest that MEK1 is a bona fide nitrosylation substrate and a target for Trx. Additional studies are needed to unravel the functional implications of MEK1 regulation by reversible S-nitrosylation. Such studies of MEK1 and other signaling proteins identified here should facilitate elucidation of redox-based mechanisms that control immune and inflammatory responses (52, 53).

We provide new evidence on the redox regulation of iNOS. Previous research has shown that iNOS is nitrosylated in activated macrophages (30). It was also found that iNOS auto-nitrosylation targets the Zn2+ tetrathiolate motif leading to enzyme inactivation and that GSH can promote reactivation (30–32). Our findings suggest that the Trx system may also contribute to maintaining iNOS in a denitrosylated, active state. Our data also support the idea that Trx promotes iNOS activity by denitrosylating and activating signaling proteins involved in the transcriptional activation of iNOS, such as MEK1 and NF-κB (28, 54). It should be noted that Trx can also promote iNOS activity via the recently reported GAPDH-heme insertion mechanism (14). Collectively, the previous and present findings suggest a complex role of the Trx system in regulating cellular S-nitrosylation. On the one hand, Trx directly reverses the nitrosylation of many proteins; on the other hand, it sustains iNOS activity, which may result in increased nitrosylation. The balance between these seemingly opposing effects of Trx could be critical in determining the nitrosylation state of different proteins. From a broader perspective, the findings support the idea that Trx not only protects the macrophage from nitrosative stress (8) but may also contribute to its cytotoxic function.

In summary, the current study expands our knowledge and insight into the nitrosoproteome of the inflammatory cell and its regulation by Trx. This report lays a foundation for future exploration of the roles of nitrosylation and denitrosylation in regulating the function of many proteins. We propose that the SNO trapping strategy may be useful for profiling and characterizing nitrosoproteomes in diverse biological contexts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Elias Arnér, Tobias Dick, Rony Seger, David Engelberg and Ariel Stanhill for providing valuable reagents and Michael Fry and Herman Wolosker for critically reading of the manuscript. We acknowledge the PRIDE team for the deposition of our data to the ProteomeXchange Consortium. The MS data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD001001 (55).

Footnotes

Author contributions: S.B. and M.B. designed research; S.B., T.Z., and P.W. performed research; S.B., T.Z., P.W., and M.B. analyzed data; S.B., T.Z., A.A., and M.B. wrote the paper.

* This work was supported by grants from the Israel Science Foundation, the Israel Cancer Association, the Israel Cancer Research Fund and the FP7 European Commission (Marie Curie) grant program (to M.B.).

This article contains supplemental material.

This article contains supplemental material.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- NO

- nitric oxide

- AF

- auranofin

- CysNO

- S-nitrosocysteine

- DNCB

- 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene

- EGF

- epidermal growth factor

- IFN-γ

- interferon-γ

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- NEM

- N-ethylmaleimide

- iNOS

- inducible nitric oxide synthase

- SNO

- S-nitrosothiol

- SNO-RAC

- resin-assisted capture of S-nitrosothiols

- Trx

- thioredoxin

- TrxR

- thioredoxin reductase

- 1400W

- N-[[3-(aminomethyl)phenyl]methyl]-ethanimidamide, dihydrochloride.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hess D. T., Matsumoto A., Kim S. O., Marshall H. E., Stamler J. S. (2005) Protein S-nitrosylation: purview and parameters. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 150–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jaffrey S. R., Erdjument-Bromage H., Ferris C. D., Tempst P., Snyder S. H. (2001) Protein S-nitrosylation: a physiological signal for neuronal nitric oxide. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 193–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marozkina N. V., Gaston B. (2012) S-Nitrosylation signaling regulates cellular protein interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1820, 722–729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gould N., Doulias P. T., Tenopoulou M., Raju K., Ischiropoulos H. (2013) Regulation of protein function and signaling by reversible cysteine s-nitrosylation. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 26473–26479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Foster M. W., Hess D. T., Stamler J. S. (2009) Protein S-nitrosylation in health and disease: a current perspective. Trends Mol. Med. 15, 391–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nakamura T., Tu S., Akhtar M. W., Sunico C. R., Okamoto S., Lipton S. A. (2013) Aberrant protein s-nitrosylation in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuron. 78, 596–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Benhar M., Forrester M. T., Hess D. T., Stamler J. S. (2008) Regulated protein denitrosylation by cytosolic and mitochondrial thioredoxins. Science 320, 1050–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Benhar M., Forrester M. T., Stamler J. S. (2009) Protein denitrosylation: enzymatic mechanisms and cellular functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 721–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Benhar M., Thompson J. W., Moseley M. A., Stamler J. S. (2010) Identification of S-nitrosylated targets of thioredoxin using a quantitative proteomic approach. Biochemistry. 49, 6963–6969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stoyanovsky D. A., Tyurina Y. Y., Tyurin V. A., Anand D., Mandavia D. N., Gius D., Ivanova J., Pitt B., Billiar T. R., Kagan V. E. (2005) Thioredoxin and lipoic acid catalyze the denitrosation of low molecular weight and protein S-nitrosothiols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 15815–15823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sengupta R., Holmgren A. (2012) The role of thioredoxin in the regulation of cellular processes by S-nitrosylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1820, 689–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thom S. R., Bhopale V. M., Milovanova T. N., Yang M., Bogush M. (2012) Thioredoxin reductase linked to cytoskeleton by focal adhesion kinase reverses actin S-nitrosylation and restores neutrophil beta(2) integrin function. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 30346–30357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ito T., Yamakuchi M., Lowenstein C. J. (2011) Thioredoxin increases exocytosis by denitrosylating N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 11179–11184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chakravarti R., Stuehr D. J. (2012) Thioredoxin-1 regulates cellular heme insertion by controlling S-nitrosation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 16179–16186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Raju K., Doulias P. T., Tenopoulou M., Greene J. L., Ischiropoulos H. (2012) Strategies and tools to explore protein S-nitrosylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1820, 684–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lopez-Sanchez L. M., Lopez-Pedrera C., Rodriguez-Ariza A. (2014) Proteomic approaches to evaluate protein s-nitrosylation in disease. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 33, 7–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Diers A. R., Keszler A., Hogg N. (2014) Detection of S-nitrosothiols. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1840, 892–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lillig C. H., Holmgren A. (2007) Thioredoxin and related molecules–from biology to health and disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 9, 25–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Verdoucq L., Vignols F., Jacquot J. P., Chartier Y., Meyer Y. (1999) In vivo characterization of a thioredoxin h target protein defines a new peroxiredoxin family. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 19714–19722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Motohashi K., Kondoh A., Stumpp M. T., Hisabori T. (2001) Comprehensive survey of proteins targeted by chloroplast thioredoxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 11224–11229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Balmer Y., Koller A., del Val G., Manieri W., Schurmann P., Buchanan B. B. (2003) Proteomics gives insight into the regulatory function of chloroplast thioredoxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 370–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schwertassek U., Balmer Y., Gutscher M., Weingarten L., Preuss M., Engelhard J., Winkler M., Dick T. P. (2007) Selective redox regulation of cytokine receptor signaling by extracellular thioredoxin-1. EMBO J. 26, 3086–3097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hwang C. Y., Ryu Y. S., Chung M. S., Kim K. D., Park S. S., Chae S. K., Chae H. Z., Kwon K. S. (2004) Thioredoxin modulates activator protein 1 (AP-1) activity and p27Kip1 degradation through direct interaction with Jab1. Oncogene. 23, 8868–8875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Forrester M. T., Foster M. W., Benhar M., Stamler J. S. (2009) Detection of protein S-nitrosylation with the biotin-switch technique. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 46, 119–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cox J., Mann M. (2008) MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carmona-Saez P., Chagoyen M., Tirado F., Carazo J. M., Pascual-Montano A. (2007) GENECODIS: a web-based tool for finding significant concurrent annotations in gene lists. Genome Biol. 8, R3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Forrester M. T., Thompson J. W., Foster M. W., Nogueira L., Moseley M. A., Stamler J. S. (2009) Proteomic analysis of S-nitrosylation and denitrosylation by resin-assisted capture. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 557–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kelleher Z. T., Sha Y., Foster M. W., Foster W. M., Forrester M. T., Marshall H. E. (2014) Thioredoxin-mediated denitrosylation regulates cytokine-induced NF-κB activation. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 3066–3072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shaul Y. D., Seger R. (2007) The MEK/ERK cascade: from signaling specificity to diverse functions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1773, 1213–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mitchell D. A., Erwin P. A., Michel T., Marletta M. A. (2005) S-Nitrosation and regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Biochemistry. 44, 4636–4647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smith B. C., Fernhoff N. B., Marletta M. A. (2012) Mechanism and kinetics of inducible nitric oxide synthase auto-S-nitrosation and inactivation. Biochemistry. 51, 1028–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rosenfeld R. J., Bonaventura J., Szymczyna B. R., MacCoss M. J., Arvai A. S., Yates J. R., 3rd, Tainer J. A., Getzoff E. D. (2010) Nitric-oxide synthase forms N-NO-pterin and S-NO-cys: implications for activity, allostery, and regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 31581–31589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Doulias P. T., Greene J. L., Greco T. M., Tenopoulou M., Seeholzer S. H., Dunbrack R. L., Ischiropoulos H. (2010) Structural profiling of endogenous S-nitrosocysteine residues reveals unique features that accommodate diverse mechanisms for protein S-nitrosylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 16958–16963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Foster M. W., Forrester M. T., Stamler J. S. (2009) A protein microarray-based analysis of S-nitrosylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 18948–18953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee Y. I., Giovinazzo D., Kang H. C., Lee Y., Jeong J. S., Doulias P. T., Xie Z., Hu J., Ghasemi M., Ischiropoulos H., Qian J., Zhu H., Blackshaw S., Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M. (2014) Protein microarray characterization of the s-nitrosoproteome. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 13, 63–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Seth D., Stamler J. S. (2011) The SNO-proteome: causation and classifications. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 15, 129–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maron B. A., Tang S. S., Loscalzo J. (2013) S-nitrosothiols and the S-nitrosoproteome of the cardiovascular system. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 270–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Evangelista A. M., Kohr M. J., Murphy E. (2013) S-nitrosylation: specificity, occupancy, and interaction with other post-translational modifications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 19, 1209–1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Murray C. I., Uhrigshardt H., O'Meally R. N., Cole R. N., Van Eyk J. E. (2012) Identification and quantification of S-nitrosylation by cysteine reactive tandem mass tag switch assay. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 11, M111.013441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Eu J. P., Liu L., Zeng M., Stamler J. S. (2000) An apoptotic model for nitrosative stress. Biochemistry. 39, 1040–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schwanhausser B., Busse D., Li N., Dittmar G., Schuchhardt J., Wolf J., Chen W., Selbach M. (2011) Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature 473, 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Beck M., Schmidt A., Malmstroem J., Claassen M., Ori A., Szymborska A., Herzog F., Rinner O., Ellenberg J., Aebersold R. (2011) The quantitative proteome of a human cell line. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim Y. M., Son K., Hong S. J., Green A., Chen J. J., Tzeng E., Hierholzer C., Billiar T. R. (1998) Inhibition of protein synthesis by nitric oxide correlates with cytostatic activity: nitric oxide induces phosphorylation of initiation factor eIF-2 alpha. Mol. Med. 4, 179–190 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kapadia M. R., Eng J. W., Jiang Q., Stoyanovsky D. A., Kibbe M. R. (2009) Nitric oxide regulates the 26S proteasome in vascular smooth muscle cells. Nitric Oxide. 20, 279–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Foster M. W., Thompson J. W., Forrester M. T., Sha Y., McMahon T. J., Bowles D. E., Moseley M. A., Marshall H. E. (2013) Proteomic analysis of the NOS2 interactome in human airway epithelial cells. Nitric Oxide. 34, 37–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kornberg M. D., Sen N., Hara M. R., Juluri K. R., Nguyen J. V., Snowman A. M., Law L., Hester L. D., Snyder S. H. (2010) GAPDH mediates nitrosylation of nuclear proteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 1094–1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nakamura T., Lipton S. A. (2013) Emerging role of protein-protein transnitrosylation in cell signaling pathways. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 239–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Smith B. C., Marletta M. A. (2012) Mechanisms of S-nitrosothiol formation and selectivity in nitric oxide signaling. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 16, 498–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Martinez-Ruiz A., Araujo I. M., Izquierdo-Alvarez A., Hernansanz-Agustin P., Lamas S., Serrador J. M. (2013) Specificity in S-Nitrosylation: A Short-Range Mechanism for NO Signaling? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 19, 1220–1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wu C., Parrott A. M., Fu C., Liu T., Marino S. M., Gladyshev V. N., Jain M. R., Baykal A. T., Li Q., Oka S., Sadoshima J., Beuve A., Simmons W. J., Li H. (2011) Thioredoxin 1-mediated post-translational modifications: reduction, transnitrosylation, denitrosylation, and related proteomics methodologies. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 15, 2565–2604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Arthur J. S., Ley S. C. (2013) Mitogen-activated protein kinases in innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 679–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wink D. A., Hines H. B., Cheng R. Y., Switzer C. H., Flores-Santana W., Vitek M. P., Ridnour L. A., Colton C. A. (2011) Nitric oxide and redox mechanisms in the immune response. J. Leukoc. Biol. 89, 873–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Brune B., Dehne N., Grossmann N., Jung M., Namgaladze D., Schmid T., von Knethen A., Weigert A. (2013) Redox control of inflammation in macrophages. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 19, 595–637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kleinert H., Pautz A., Linker K., Schwarz P. M. (2004) Regulation of the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 500, 255–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vizcaino J. A., Cote R. G., Csordas A., Dianes J. A., Fabregat A., Foster J. M., Griss J., Alpi E., Birim M., Contell J., O'Kelly G., Schoenegger A., Ovelleiro D., Perez-Riverol Y., Reisinger F., Rios D., Wang R., Hermjakob H. (2013) The PRoteomics IDEntifications (PRIDE) database and associated tools: status in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D1063–D1069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.