Highlights

-

•

Long thoracic nerve injury is a potential complication of rib fracture fixation.

-

•

Long thoracic nerve injury from rib fracture fixation has not been reported.

-

•

Long thoracic nerve injury can be corrected surgically by pectoralis major transfer.

Keywords: Medial, Scapular, Winging, Rib fractures, Rib plating, Pectoralis major transfer

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Rib plating is becoming increasingly common as a method for stabilizing a flail chest resulting from multiple rib fractures. Recent guidelines recommend surgical stabilization of a flail chest based on consistent evidence of its efficacy and lack of major safety concerns. But complications of this procedure can occur and are wide ranging.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

We report an interesting case of a 58-year-old male patient that worked as a long-distance truck driver and had a flail chest from multiple bilateral rib fractures that occurred when his vehicle was blown over in a wind storm. He underwent open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF) of the bilateral rib fractures and they successfully healed. However, he had permanent long thoracic nerve injury on the side with the most severe trauma. This resulted in symptomatic scapular winging that impeded him from long-distance truck driving. The scapular winging was surgically corrected nearly two years later with a pectoralis major transfer augmented with fascia lata graft. The patient had an excellent final result.

DISCUSSION

We report this case to alert surgeons who perform rib fracture ORIF that long thoracic nerve injury is a potential iatrogenic complication of that procedure or might be a result of the chest wall trauma.

CONCLUSION

Although the specific cause of the long thoracic nerve injury could not be determined in our patient, it was associated with chest wall trauma in the setting of rib fracture ORIF. The scapular winging was surgically corrected with a pectoralis major transfer.

1. Introduction

Rib plating is becoming increasingly common as a method for stabilizing a flail chest resulting from multiple rib fractures. Studies have shown that when patients undergo open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF) of rib fractures they require shorter periods of ventilator support, which in turn reduces morbidity and mortality associated with mechanical ventilation, and reduces risk of contracting infections or septicemia.1,2 Complications of this procedure include fracture nonunion, infection (including osteomyelitis), pneumothorax, hardware prominence, failure or loss of fixation, and post-operative chest wall “stiffness”, “rigidity”, or pain necessitating plate removal.3–8 We report an interesting case of a patient that underwent ORIF for bilateral rib fractures that successfully healed, but was complicated by permanent long thoracic nerve injury that resulted in scapular winging. The scapular winging was surgically corrected with a pectoralis major transfer and the patient had an excellent result.

2. Informed consent

The patient was informed and consented that data concerning the case would be submitted for publication.

3. Presentation of case

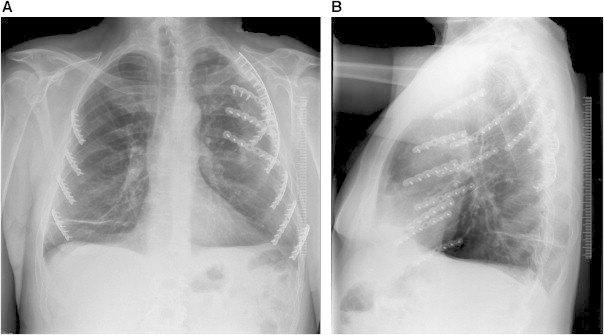

The patient is a 58 year-old, right-hand-dominant male who was in a work-related motor vehicle accident in February 2011. He was in a roll-over truck accident and sustained bilateral closed rib fractures with pneumothoraces and a closed left mid-shaft clavicle fracture. Chest tubes were placed and the left ribs (3–7), where the injuries were more severe, were plated on the next day. The right ribs (3–6) were plated one day later (Fig. 1). The left clavicle fracture was treated non-operatively.

Fig. 1.

Anterior–posterior (AP) and lateral chest radiographs showing the ribs with metal plates and screws. Note that there are more plates on the left side for the more extensive injuries there. The winging also occurred on this side (the patient's left side is the right side of AP radiograph).

Despite healing of the clavicle and all of the rib fractures, the patient reported difficulty driving a semi truck because of pain associated with lifting his left arm up to the steering wheel. He noted shoulder weakness and a sense of instability. Electrodiagnostic testing (electromyography and nerve conduction studies) was done six months later and showed left-side long thoracic nerve injury without evidence of reinnervation. Our clinical examination showed medial winging of the left scapula. Magnetic resonance (MR) scans also showed a possible anterior glenoid labral tear of the same shoulder.

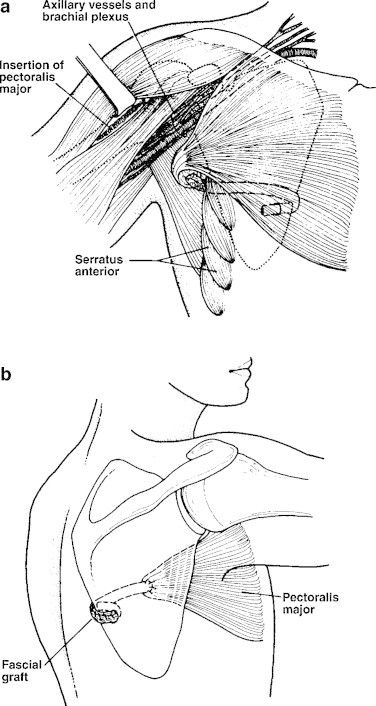

The patient was then first seen in our clinic 21 months after the trauma. His scapular winging and other left upper extremity complaints had not improved. His pre-operative Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) score was 64 (0 = best, 100 = worst).9 At 23 months after the trauma, the patient underwent a pectoralis major transfer to the left inferior scapula. The tendon of the pectoralis major was augmented with an autogenous fascia lata graft. The muscle tendon transfer surgery was done in accordance with the description of Perlmutter and Leffert10 (Fig. 2a and b). Arthroscopic left shoulder surgery was also done at the same setting and the torn anterior glenoid labrum was arthroscopically repaired.

Fig. 2.

(A) Illustration of chest (anterior view) showing passage of the lengthened tendon between the scapula and the chest wall, medial to the axillary vessels and the brachial plexus, to the medial border of the scapula. (B) Illustration of lateral chest showing fixation of the graft into the hole made in the medial aspect of the scapula. The graft is sutured to itself with several non-absorbable sutures.

Images reproduced from Perlmutter and Leffert10 with permission of The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, Inc.

In accordance with the general recommendations of Perlmutter and Leffert,10 the patient started formal physical therapy at eight weeks after the operation. This was continued for 3 months. Physical therapy emphasized active range-of-motion exercises and strengthening of the rotator cuff and the trapezius. A home exercise program was then continued for three additional months. The patient was advised against returning to manual labor or sports activities for six months after the operation.

The DASH score at one year post-operation had markedly improved and was 10 (pre-operation: 64). At his final follow up, 14 months after muscle transfer surgery, the scapular winging was no longer present. He was also able to drive a truck for 12 h without any discomfort. He was very satisfied with his final result.

4. Discussion

We could not locate a case report of the association of the long thoracic nerve injury with rib fracture plating. It could not be determined if the nerve injury in our patient was an iatrogenic complication occurring during the surgical procedure or was caused by the rib fractures. Support for the possibility that our patient's long thoracic nerve injury was caused by the trauma include the greater severity of the injuries on the involved side, including the clavicle fracture and the greater number of fractured ribs. Additional, through less direct, support for the possibility that the trauma caused our patient's long thoracic nerve injury is suggested by Gozna and Harris.11 Three of their 14 patients with scapular winging due to trauma also suffered from fractures on the ipsilateral side (one with fracture of the scapula, one with fracture of the humerus, and one with fracture of the clavicle). Long thoracic nerve injury is also a known complication of chest wall trauma without any fractures12,13 and also with rib fractures.14,15 The patient described by Rasyid et al.14 had scapular winging with an ipsilateral mid-shaft clavicle fracture and flail chest. The scapular winging in their patient improved “immediately after” surgical fixation (ORIF) of the clavicle fracture. This contrasts with our patient who had persistent scapular winging despite healing of his ipsilateral mid-shaft clavicle fracture.

In contrast to these prior studies, to our knowledge, long thoracic nerve injury has not been described as the direct result of rib fracture ORIF. One reason for reporting this case is to alert surgeons who perform rib fracture ORIF that long thoracic nerve injury is a potential complication of that procedure or might result from more direct injury from the chest wall trauma. In either case the winging would most likely not be recognized pre-operatively because of the recumbency of these patients. But patients that are able to receive informed consent could be informed that long thoracic nerve might be present prior to rib fracture ORIF. Another important aspect of our patient's post-operative course was that our patient was in physical therapy for 12 weeks, which is double that recommended by Perlmutter and Leffert.10 The increased duration of physical therapy likely reflects the relatively advanced age of our patient (58 years old) when compared to other patients (124 cases with average age 33 years old) who have had this procedure for post-traumatic winging and have been reported in the literature.10,16–28

5. Conclusion

Whether caused by chest wall trauma or rib fracture ORIF, long thoracic nerve injury with resulting scapular winging can be surgically corrected with a pectoralis major transfer augmented with fascia lata graft.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contributions

Each of the five authors participated in each of the following capacities: study design, data collections, data analysis and writing.

Contributor Information

John G. Skedros, Email: jskedrosmd@uosmd.com, teambone@gmail.com.

Chad S. Mears, Email: chadmears330@gmail.com.

Tanner D. Langston, Email: tannerlangston1@gmail.com.

Don H. Van Boerum, Email: Don.vanboerum@imail.org.

Thomas W. White, Email: tom.white@imail.org.

References

- 1.Nirula R., Allen B., Layman R., Falimirski M.E., Somberg L.B. Rib fracture stabilization in patients sustaining blunt chest injury. Am Surg. 2006;72(4):307–309. doi: 10.1177/000313480607200405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Althausen P.L., Shannon S., Watts C., Thomas K., Bain M.A., Coll D. Early surgical stabilization of flail chest with locked plate fixation. J Orthop Trauma. 2011;25(11):641–647. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318234d479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gardenbroek T.J., Bemelman M., Leenen L.P. Pseudarthrosis of the ribs treated with a locking compression plate. A report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(6):1477–1479. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paris F., Tarazona V., Blasco E., Canto A., Casillas M., Pastor J. Surgical stabilization of traumatic flail chest. Thorax. 1975;30(5):521–527. doi: 10.1136/thx.30.5.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lardinois D., Krueger T., Dusmet M., Ghisletta N., Gugger M., Ris H.B. Pulmonary function testing after operative stabilisation of the chest wall for flail chest. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;20(3):496–501. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)00818-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reber P.U., Kniemeyer H.W., Ris H.B. Reconstruction plates for internal fixation of flail chest. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66(6):2158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hellberg K., de Vivie E.R., Fuchs K., Heisig B., Ruschewski W., Luhr H.G. Stabilization of flail chest by compression osteosynthesis – experimental and clinical results. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1981;29(5):275–281. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1023495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nirula R., Mayberry J.C. Rib fracture fixation: controversies and technical challenges. Am Surg. 2010;76(8):793–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.SooHoo N.F., McDonald A.P., Seiler J.G., 3rd, McGillivary G.R. Evaluation of the construct validity of the DASH questionnaire by correlation to the SF-36. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27(3):537–541. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.32964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perlmutter G.S., Leffert R.D. Results of transfer of the pectoralis major tendon to treat paralysis of the serratus anterior muscle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(3):377–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gozna E.R., Harris W.R. Traumatic winging of the scapula. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61(8):1230–1233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gregg J.R., Labosky D., Harty M., Lotke P., Ecker M., DiStefano V. Serratus anterior paralysis in the young athlete. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61(6A):825–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foo C.L., Swann M. Isolated paralysis of the serratus anterior. A report of 20 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1983;65(5):552–556. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.65B5.6643557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasyid H.N., Nakajima T., Hamada K., Fukuda H. Winging of the scapula caused by disruption of “sternoclaviculoscapular linkage”: report of 2 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(2):144–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atasoy E., Majd M. Scapulothoracic stabilisation for winging of the scapula using strips of autogenous fascia lata. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(6):813–817. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.82b6.10187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iceton J., Harris W.R. Treatment of winged scapula by pectoralis major transfer. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69(1):108–110. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.69B1.3029135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Streit J.J., Lenarz C.J., Shishani Y., McCrum C., Wanner J.P., Nowinski R.J. Pectoralis major tendon transfer for the treatment of scapular winging due to long thoracic nerve palsy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(5):685–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galano G.J., Bigliani L.U., Ahmad C.S., Levine W.N. Surgical treatment of winged scapula. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(3):652–660. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0086-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noerdlinger M.A., Cole B.J., Stewart M., Post M. Results of pectoralis major transfer with fascia lata autograft augmentation for scapula winging. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(4):345–350. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.124525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warner J.J., Navarro R.A. Serratus anterior dysfunction. Recognition and treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;349:139–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Post M. Pectoralis major transfer for winging of the scapula. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4(1 Pt 1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(10)80001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Connor P.M., Yamaguchi K., Manifold S.G., Pollock R.G., Flatow E.L., Bigliani L.U. Split pectoralis major transfer for serratus anterior palsy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;341:134–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiater J.M., Flatow E.L. Long thoracic nerve injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;368:17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinmann S.P., Wood M.B. Pectoralis major transfer for serratus anterior paralysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(6):555–560. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(03)00174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Litts C.S., Hennigan S.P., Williams G.R. Medial and lateral pectoral nerve injury resulting in recurrent scapular winging after pectoralis major transfer: a case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(4):347–349. doi: 10.1067/mse.2000.106081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marmor L., Bechtol C.O. Isolated paralysis of serratus anterior due to an electrical injury. Calif Med. 1961;94:241–242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tauber M., Moursy M., Koller H., Schwartz M., Resch H. Direct pectoralis major muscle transfer for dynamic stabilization of scapular winging. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(Suppl. 1):29S–34S. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Durman D.C. An operation for paralysis of the serratus anterior. J Bone Joint Surg. 1945;27:380–382. [Google Scholar]