Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Pythiosis is a serious life- and limb-threatening infection endemic to Thailand, but rarely seen in the Western hemisphere. Here, we present a unique case of vascular pythiosis initially managed with limb-sparing vascular bypass grafts complicated by a pseudoaneurysm in our repair.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

The patient is a 17 year-old Jamaican male with severe aplastic anemia. He sustained a minor injury to his left leg while fishing in Jamaica, which evolved to become an exquisitely tender inguinal swelling. His physical exam and imaging were significant for arteriovenous fistula with limb ischemia. Pathology obtained during surgery for an extra-anatomic vascular bypass showed extensive invasion by Pythium insidiosum. He later developed a pseudoaneurysm at the site of proximal anastomosis and required urgent intervention.

DISCUSSION

This patient presented with a rare, but classic case of vascular pythiosis, which was unrecognized at the time of presentation. A variety of therapeutic modalities have been used to treat this disease, including antibiotics, antifungals, and immunotherapy, but the ultimate management of vascular pythiosis is surgical source control.

CONCLUSION

A high index of suspicion in susceptible patients is needed for timely diagnosis of vascular pythiosis to achieve optimal source control.

Keywords: Pythium insidiosum, Pythiosis, Vascular bypass, Pseudoaneurysm

1. Introduction

First described by veterinarians,1 pythiosis is a serious life- and limb-threatening infection endemic to Thailand, but rarely seen in the Western hemisphere.2 Known to infect immunocompetent horses, dogs, and other large animals,2, 3 Pythium infection was first reported in humans in 1989 in association with thalassemic hemoglobinopathy.4, 5 Human pythiosis is known to present in one of four clinical entities: subcutaneous, ocular, vascular, and disseminated.6 Here, we present a unique case of vascular pythiosis managed with limb-sparing vascular bypass grafts complicated by pseudoaneurysm formation.

2. Presentation of case

The patient is a 17 year-old Jamaican male with a history of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria and severe aplastic anemia refractory to horse anti-thymoglobulin treatment, which was transfusion-dependent. One month prior to admission at our institution, he went fishing in a fresh water pond in Jamaica and his left lower leg was caught in a bush. On the following day, he noticed a small bullae with a black center and later developed severely painful left inguinal swelling. He was admitted to a local hospital for the next several weeks, where all diagnostic testing performed was unremarkable. His pain persisted despite antibiotic and antifungal therapy, and he was later transferred to our institution for consideration of bone marrow transplant.

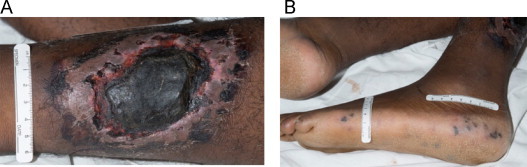

On admission, he was a febrile with a white blood cell count of 6.2 (K/μL) and platelet count of 18 (K/μL) and was complaining of severe left leg pain. He had a 9 × 8 cm2 soft tissue defect with overlying escar on the posterior aspect of his left leg (Fig. 1A), and his exam was also notable for an exquisitely tender and erythematous left inguinal mass. Motor and sensory exam were intact in both lower extremities without pain upon passive hip flexion. Several small, dark macules were noted along the lateral aspect of his left foot (Fig. 1B) and his left dorsalis pedis pulse was weaker than the right. Most significantly, he exhibited pain out of proportion to exam findings.

Fig. 1.

(A) Ischemic ulcer with overlying escar and (B) distal emboli.

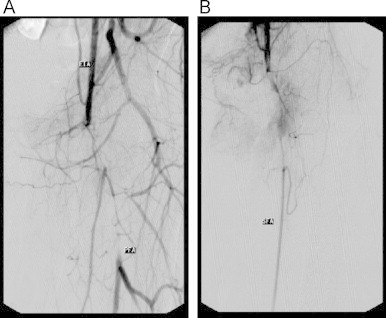

MRI showed a T2 bright left groin mass with edema along the fascial planes, and lower extremity angiogram demonstrated occlusion of the left common femoral artery with distal profunda femoris and mid-superficial femoral artery reconstitution (Fig. 2). Due to the length of the diseased vessel, the patient was not a candidate for percutaneous intervention, and was taken to the operating room for exploration. Visual inspection of the common femoral artery after exposure was significant for several patches of necrotic vessel wall. Initial attempt with thrombectomy was unsuccessful, as the Fogarty catheter actually perforated the anterior wall at the areas of necrosis. The patient ultimately received an extra-anatomic left external iliac to superficial femoral artery bypass using a nonreversed greater saphenous vein graft, as the external iliac was the closest available inflow that did not visually appear to be involved with the infection.

Fig. 2.

(A) Left common femoral artery occlusion with distal profunda femoris reconstitution with (B) small and underperfused superficial femoral artery with mid-vessel reconstitution.

Intraoperative wound cultures were positive for Pythium insidiosum and the patient was started on a combination of voriconazole, terbinafine, and amphotericin B. Given his critical condition, an emergency Investigational New Drug request was drafted for permission to administer a P. insidiosum antigen vaccine available for compassionate use from the Pan American Veterinary Laboratories. The vaccine was given once daily in one-week intervals in conjunction with subcutaneously injected interferon gamma (IFN-γ), for a total of four weeks. Iron chelation therapy was also started as adjunctive treatment.

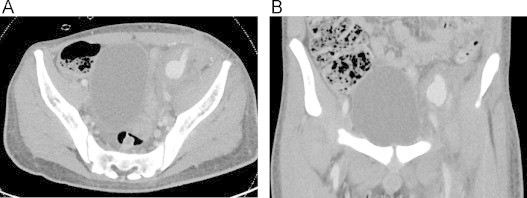

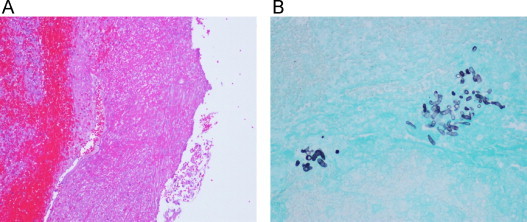

Three weeks after his initial surgery, the patient developed new sites of pain along the graft site and repeat imaging showed a 2.5 cm pseudoaneurysm at the proximal anastomosis to the external iliac artery with contrast extravasation (Fig. 3). He was taken to the operating room for an extra-anatomic left common iliac artery to the previous femoral popliteal bypass graft using a reverse saphenous vein graft. Staining of intraoperative tissue demonstrated an extremely high burden of fungal elements (Fig. 4), indicating that the pythium infection remained uncontrolled. The patient later developed a polymicrobial superinfection of his wounds, and his vascular repair continued to break down leading to increased ischemic pain. After several multidisciplinary discussions with the family that all medical interventions were exhausted, and that even highly aggressive surgical measures including hip disarticulation or hemipelvectomy could not guarantee source control, conservative measures were initiated and ultimately, the patient expired.

Fig. 3.

Left external iliac artery pseudoaneurysm (A) axial and (B) coronal section.

Fig. 4.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of pseudoaneurysm wall shown at 10× demonstrating extensive vessel wall necrosis and (B) Grocott's methenamine silver stain of pseudoaneurysm showing clusters of Pythium.

3. Discussion

This patient presented a major diagnostic challenge, and his disease process and subsequent management were previously unknown to our hospital. In retrospect, he presented with a classic case of vascular pythiosis, with an antecedent history of exposure to surface water and exam findings of vascular insufficiency, including pain out of proportion to exam, distal emboli, and an ischemic ulcer. The correct infectious diagnosis was not made until 1 month after exposure, after a vascular bypass was already performed. Indeed, in a large multi-institutional study from Thailand with a total of 102 cases of pythiosis,7 60 patients received a diagnosis of vascular pythiosis, and only the patients who had undergone amputation survived. Further review of the literature for reports of vascular pythiosis demonstrated that the majority of patients were treated with amputation without any signs of recurrence, and were followed for 5 to 35 months post-operatively.4, 6, 8, 9 In our case, complete source control was not achieved during the first operation since the common femoral artery and the proximal portion of the superficial femoral artery were oversewn and left in place, standard practice for the treatment of peripheral arterial disease. Incomplete source control eventually led to development of a pseudoaneurysm at the proximal anastomosis and additional surgery. While the second repair was cited in previously uninvolved tissue planes, it did not protect against further infection, likely because P. insidiosum is known to invade through proteinase secretion.10 The authors could find no reported cases of confirmed vascular pythiosis treated with limb-sparing procedures.2, 7, 11, 12

Medical therapy in the treatment of vascular pythiosis involves antifungal agents, immunotherapy, and iron chelation therapy.13 Much of the difficulty in eradicating this organism stems from its complicated phylogenesis;2, 6, 14 it shares features with true fungi at the same time it is phylogenetically more closely related to algae and diatomeae.14 P. insidiosum develops mycelium like fungi, but its cell walls do not contain chitin and its cytoplasmic membrane lacks ergosterol,2 both of which are important targets of traditional antifungal drugs. Despite this, drugs that affect cellular permeability, including amphotericin B, terbinafine, and the azoles, have been used with some clinical success.2, 15

More recently, immunotherapy has been used as an adjunct to surgery and antimycotics. Immunotherapy was first successfully used in humans in 1998 in a patient with a vascular P. insidiosum infection refractory to surgery and antifungals.2, 16 A P. insidiosum vaccine delivered twice with a two-week interval resulted in a cure 1 year later. Data collected from clinical trials and other reports estimate vaccine efficacy to be 55–60%.2, 17 The proposed mechanism of action of the P. insidiosum vaccine is to shift host adaptive immune response from a predominantly T helper 2 (Th2) response to a T helper 1 (Th1) response.2, 17 Pythium exoantigens are typically processed by antigen presenting cells (APCs) and presented to naïve CD4+ helper T cells (Th0). This induces Th0 cells to adopt a Th2 phenotype secreting IL-4 and IL-5, which trigger many downstream effects, including mast cell and eosinophil migration to the site of infection with subsequent degranulation, releasing inflammatory mediators and causing tissue damage. Loss of tissue architecture then creates a more favorable environment for these pathogenic hyphae to take hold. Conversion of a Th2 to Th1 response would favor secretion of IFN-γ and IL-2, leading to increased cytotoxic T lymphocyte recruitment and therefore, direct killing of P. insidiosum. In this case, the purpose of injecting IFN-γ subcutaneously was to augment a Th1 response, and co-administration of GM-CSF was to increase the efficiency of exoantigen presentation to APCs.

Another treatment modality used to control this infection is iron chelation therapy. Given the association between pythium infection in patients with hemoglobinopathies with a long-standing history of blood transfusions4, 7 and the discovery of a ferrochelatase gene in P. insidiosum,18 other research efforts have focused on elucidating the role of iron overload in P. insidiosum pathogenesis.13 There is evidence that iron overload from transfusions contributes to derangements in host immunity by impairing lymphocyte function and altering phagocytosis, leading to a more susceptible state for infection6, 19 and is in fact, a key virulence factor for the survival of P. insidiosum in the host.13 Correcting iron overload has been cited as a treatment in infections common in thalassemia,20 and has also been used in pythiosis. In our patient, iron chelation with deferasirox seemed to achieve some symptom relief.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, this patient's vascular P. insidiosum infection was refractory to optimized medical treatment, immunotherapy with cytokine injections, and surgery. Attempted source control with limb salvage necessitating vascular bypass was unsuccessful in treating this case of vascular pythiosis.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's guardian for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Key learning points

-

•

Clinicians should maintain a high level of suspicion for vascular pythiosis when presented with a patient with an underlying hemoglobinopathy, exposure to flat water, and exam findings of vascular insufficiency.

-

•

The most important part in managing vascular pythiosis limb infection is adequate source control with amputation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Health, National Cancer Institute.

References

- 1.Smith F. The pathology of bursattee. Vet J. 1884;19:16–17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaastra W., Lipman L.J., De Cock A.W., Exel T.K., Pegge R.B., Scheurwater J. Pythium insidiosum: an overview. Vet Microbiol. 2010;146(1–2):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Cock A.W., Mendoza L., Padhye A.A., Ajello L., Kaufman L. Pythium insidiosum sp. nov., the etiologic agent of pythiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25(2):344–349. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.2.344-349.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sathapatayavongs B., Leelachaikul P., Prachaktam R., Atichartakarn V., Sriphojanart S., Trairatvorakul P. Human pythiosis associated with thalassemia hemoglobinopathy syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1989;159(2):274–280. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thianprasit M. Fungal infection in Thailand. Jpn J Dermatol. 1986;96:1343–1345. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laohapensang K., Rutherford R.B., Supabandhu J., Vanittanakom N. Vascular pythiosis in a thalassemic patient. Vascular. 2009;17(4):234–238. doi: 10.2310/6670.2008.00073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krajaejun T., Sathapatayavongs B., Pracharktam R., Nitiyanant P., Leelachaikul P., Wanachiwanawin W. Clinical and epidemiological analyses of human pythiosis in Thailand. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(5):569–576. doi: 10.1086/506353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sudjaritruk T., Sirisanthana V. Successful treatment of a child with vascular pythiosis. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keoprasom N., Chularojanamontri L., Chayakulkeeree M., Chaiprasert A., Wanachiwanawin W., Ruangsetakit C. Vascular pythiosis in a thalassemic patient presenting as bilateral leg ulcers. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2012;2:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ravishankar J.P., Davis C.M., Davis D.J., MacDonald E., Makselan S.D., Millward L. Mechanics of solid tissue invasion by the mammalian pathogen Pythium insidiosum. Fungal Genet Biol. 2001;34(3):167–175. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.2001.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMullan W.C., Joyce J.R., Hanselka D.V., Heitmann J.M., Amphotericin B. for the treatment of localized subcutaneous phycomycosis in the horse. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1977;170(11):1293–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendoza L., Alfaro A.A. Equine pythiosis in Costa Rica: report of 39 cases. Mycopathologia. 1986;94(2):123–129. doi: 10.1007/BF00437377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zanette R.A., Alves S.H., Pilotto M.B., Weiblen C., Fighera R.A., Wolkmer P. Iron chelation therapy as a treatment for Pythium insidiosum in an animal model. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(5):1144–1147. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin F.N., Tooley P.W. Phylogenetic relationships among Phytophthora species inferred from sequence analysis of mitochondrially encoded cytochrome oxidase I and II genes. Mycologia. 2003;95(2):269–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shenep J.L., English B.K., Kaufman L., Pearson T.A., Thompson J.W., Kaufman R.A. Successful medical therapy for deeply invasive facial infection due to Pythium insidiosum in a child. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(6):1388–1393. doi: 10.1086/515042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thitithanyanont A., Mendoza L., Chuansumrit A., Pracharktam R., Laothamatas J., Sathapatayavongs B. Use of an immunotherapeutic vaccine to treat a life-threatening human arteritic infection caused by Pythium insidiosum. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(6):1394–1400. doi: 10.1086/515043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendoza L., Newton J.C. Immunology and immunotherapy of the infections caused by Pythium insidiosum. Med Mycol. 2005;43(6):477–486. doi: 10.1080/13693780500279882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krajaejun T., Khositnithikul R., Lerksuthirat T., Lowhnoo T., Rujirawat T., Petchthong T. Expressed sequence tags reveal genetic diversity and putative virulence factors of the pathogenic oomycete Pythium insidiosum. Fungal Biol. 2011;115(7):683–696. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker E.M., Jr., Walker S.M. Effects of iron overload on the immune system. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2000;30(4):354–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wanachiwanawin W. Infections in E-beta thalassemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22(6):581–587. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200011000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]