Summary

Neuregulins (NRGs) comprise a large family of growth factors that stimulate ERBB receptor tyrosine kinases. NRGs and their receptors ERBBs have been identified as susceptibility genes for diseases such as schizophrenia (SZ) and bipolar disorder. Recent studies have revealed complex Nrg/Erbb signaling networks that regulate the assembly of neural circuitry, myelination, neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity. Evidence indicates there is an optimal level of NRG/ERBB signaling in the brain and deviation from it impairs brain functions. NRGs/ERBBs and downstream signaling pathways may provide therapeutic targets for specific neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Introduction

Neuregulins (NRGs) comprise a large family of widely expressed epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like proteins that have been implicated in neural development and brain activity homeostasis. NRG1 was the first member of the family to be discovered, 22 years ago, for very different biological functions, including activation of ERBB receptors, stimulation of Schwann cell growth and induction of acetylcholine receptor expression (Falls, 2003; Mei and Xiong, 2008). Since then, five additional NRG genes (NRG2-6) have been identified (Figure 1). Each NRG gene gives rise to multiple splice isoforms (>30 for NRG1 and >15 for NRG3, for example) (Kao et al., 2010; Mei and Xiong, 2008). Immature NRGs are transmembrane proteins, which release (upon proteolytic processing) soluble N-terminal moieties that contain the EGF-like signaling domain (Figure 2). NRGs and related EGF domain-containing proteins interact with and activate receptor tyrosine kinases of the ErbB family, each of which initiates intracellular signaling pathways in a specific way, including non-canonical mechanisms (Figures 1 and 2). Nrg/Erbb signaling has been implicated in neural development including circuitry generation, axon ensheathment, neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity. Several members of this signaling network are encoded by susceptibility genes of psychiatric disorders like SZ, bipolar disorder or depression.

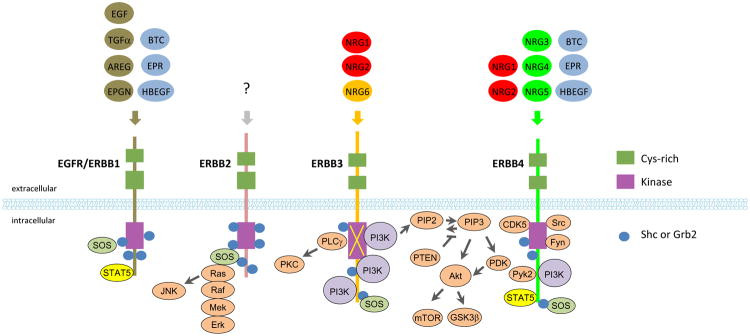

Figure 1. NRG-ERBB canonical signaling.

NRGs are encoded by six individual genes NRG1-6 (Carraway et al., 1997; Chang et al., 1997; Harari et al., 1999; Howard et al., 2005; Kanemoto et al., 2001; Kinugasa et al., 2004; Uchida et al., 1999; Watanabe et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 1997). NRG1 has six Types (I-VI), each with a distinct N-terminus, Ig domain and/or cysteine-rich domain. NRG1 Type I was identified as heregulin, neu differentiation factor (NDF), and ARIA (acetyl choline receptor inducing activity) (Holmes et al., 1992; Peles et al., 1992). Type II and III were identified as GGF (for ‘glial growth factor’) (Lemke and Brockes, 1984) and SMDF (for ‘sensory and motor neuron derived factor’), respectively (Ho et al., 1995). NRG5 is also called tomoregulin or TMEFF1 (transmembrane protein with EGF-like and two follistatin-like domains 1); whereas NRG6 could be referred as neuroglycan C, CSPG5 (chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 5) or CALEB (chicken acidic leucine-rich EGF-like domain containing brain protein). NRGs are synthesized as transmembrane proteins and display an extracellular EGF-like domain, which is essential for ERBB receptor binding. ERBB tyrosine kinases have four members: EGFR/ERBB1, ERBB2, ERBB3 and ERBB4, each of which has a unique group of ligands except ERBB2 whose ligand remains unknown. ERBB3 kinase activity is impaired (indicated by a cross). Ligand binding causes dimerization and activation of ERBBs, and subsequent phosphorylation of the intracellular domains (ICDs), and creates docking sites for adapter proteins including Grb2 and Shc for Erk activation and for p85 for PI3K activation, and for Src kinases, Pyk2 and Cdk5, and PLCγ. Ligands and ERBBs are color-matched, those in light blue bind both to EGFR and ERBB4 and those in red bind both to ERBB3 and ERBB4.

Abbreviations. AREG, amphiregulin; BTC, β-cellulin; CSPG5, chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 5; CTF, C-terminal fragment; CALEB, chicken acidic leucine-rich EGF-like domain containing brain protein; ECD, extracellular domain; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, EGF receptor; EPGN, epigen; EPR, epiregulin; Grb2, growth factor receptor-bound protein 2; HBEGF, heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor; ICD, intracellular domain; Ig, immunoglobin; LDLR-B, LDL receptor class B; Shc, SRC-homology domain-containing; Stat5, signal transducer and activator of transcription 5; TGFα, transforming growth factor-α.; TMEFF1, transmembrane protein with EGF-like and two follistatin-like domains 1.

Figure 2. Nrg1 non-canonical signaling.

Nrg1 is cleaved by extracellular proteases including BACE1 (or disintegrin or ADAM) (Hu et al., 2006; Luo et al., 2011; Savonenko et al., 2008; Velanac et al., 2012; Willem et al., 2006) and neuropsin to release soluble, mature Nrg1 that contains the EGF-like domain (Tamura et al., 2012). Soluble Nrg1 binds and activates Erbb kinases to activate the canonical pathways although soluble Nrg1-induced endocytosis of GABA-A receptor α1 was independent of Erbb4 kinase (Mitchell et al., 2013) (Box I) (see Figure 1). Pro-Nrg1 and mature Type III may function as receptor of soluble, extracellular domain of Erbb4 to initiate backward signaling (Hancock et al., 2008; Zhong et al., 2008) (Box II). Transmembrane Nrg1s could directly interact with transmembrane Erbb4 or other proteins to signal in a cell-adhesion dependent manner, some of which may be kinase-independent (Chen et al., 2010a; Chen et al., 2008; Del Pino et al., 2013; Fazzari et al., 2010; Krivosheya et al., 2008)(Box III). Cleavage of Nrg1- or Erbb4-C-terminal fragments (CTFs) give rise to respective intracellular domains (ICDs) that are believed to signal into the nucleus (Bao et al., 2004; Bao et al., 2003) (Lee et al., 2002; Ni et al., 2001; Sardi et al., 2006) (Box IV and V).

Here we review recent progress in identifying Nrg/Erbb signaling functions in the developing and adult nervous system, the involvement of the human NRG and ERBB genes in neuropsychiatric diseases, and suggested pathophysiological mechanisms of abnormal NRG/ERBB signaling. For comprehensive reviews on the molecular diversity of the NRG/ERBB network, see also (Britsch, 2007; Buonanno and Fischbach, 2001; Corfas et al., 2004; Esper et al., 2006; Falls, 2003; Mei and Xiong, 2008; Nave and Salzer, 2006; Rico and Marin, 2011).

Assembly of neuronal circuitry

In the developing cortex, most glutamatergic neurons are born in ventricular and subventricular zones and populate the cortex via radial migration. This is in contrast to GABAergic interneurons which are generated in ganglionic eminences and migrate tangentially for their destination (Corbin et al., 2001; Franco and Muller, 2013; Ghashghaei et al., 2007; Marin and Rubenstein, 2003; Metin et al., 2006; Nadarajah and Parnavelas, 2002). After migration, both types of neurons differentiate to generate axons and dendrites that form an increasingly complex circuitry in the brain. Nrg/Erbb signaling is involved at multiple stages of cortical circuit development. First, we will focus on their roles in assembling the GABAergic circuit. We will then discuss their implications in building the glutamatergic circuit.

Nrg and Erbb kinases, in particular Erbb4, are critical for the assembly of the GABAergic circuitry including interneuron migration, axon and dendrite development, and synapse formation (Figure 3). As early as E13 in the mouse, Erbb4 is present on progenitors in the median ganglionic eminence (MGE) where interneurons are born, and later in the migratory streams in cells positive for Dlx, a marker of tangentially migrating neurons (Yau et al., 2003). In adult brains, Erbb4 transcripts have been localized to regions where interneurons are enriched (Lai and Lemke, 1991; Woo et al., 2007). The protein is found in hippocampal neurons that are GAD positive (Huang et al., 2000) and neurons that express parvalbumin (PV) and somatostatin (Abe et al., 2011; Fazzari et al., 2010; Fox and Kornblum, 2005; Neddens and Buonanno, 2011; Vullhorst et al., 2009; Woo et al., 2007; Yau et al., 2003). Recent studies suggest that Erbb4 is expressed exclusively in interneurons and not at all in excitatory neurons (Vullhorst et al., 2009; Fazzari et al., 2010). At the subcellular level, Erbb4 was shown to be in axonal terminals of interneurons by electron microscopy or immunofluorescence staining (Fazzari et al., 2010; Woo et al., 2007) although this notion was challenged (Neddens and Buonanno, 2011; Neddens et al., 2009). Erbb4 has also been found on the postsynaptic site of excitatory and inhibitory synapses in GABAergic interneurons (Fazzari et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2001; Krivosheya et al., 2008; Vullhorst et al., 2009; Woo et al., 2007) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Nrg1 and Erbb4 in neural circuitry assembly.

A, Regulation of migration and differentiation of GABAergic interneurons, including development of neuronal processes and synapse formation.

B, Schematic diagram of inhibitory and excitatory circuitries.

C, Cellular mechanisms of Nrg1 and Erbb4 in forming inhibitory and excitatory synapses onto inhibitory and excitatory neurons. tmNrg1, transmembrane Nrg1 including Type III Nrg1 and proNrg1; sNrg, soluble Nrg1. See text for details.

Two models have been proposed to explain how Nrg1 may participate in interneuron migration during cortical development. In one, Erbb4-expressing interneurons, in response to attractive, soluble Nrg1 Type I in the cortex, migrate on a permissive corridor of Nrg1 Type III through the developing striatum (Flames et al., 2004). In the other, Nrg1 and Nrg3 act as repellants that funnel interneurons as they migrate from the MGE to cortical destinations (Li et al., 2012a). Regardless, GABAergic interneurons are reduced in the cortex of Erbb4 mutant mice, which supports a role for Erbb4 in tangential migration (Fisahn et al., 2009; Flames et al., 2004; Li et al., 2012a; Schmucker et al., 2003). It remains unclear, however, if genesis and/or survival of interneurons are altered in the mutant. Intriguingly, viral deletion of the floxed Erbb4 gene at E13.5 has little effect on the number and distribution of interneurons in cortical layers (Fazzari et al., 2010). This may be due to a critical time window (prior to E13.5) for Erbb4 regulation of interneuron migration or to a slow turnover of Erbb4 protein after gene deletion.

In addition to their role in regulating aspects of interneuron migration, Nrg1/Erbb4 signaling mechanisms have also been suggested to contribute to axon and dendrite development of GABAergic neurons, at least in vitro. Treating hippocampal cultures (from Gad65-GFP transgenic mice) with recombinant Nrg1 promotes axon elongation and branching of labeled interneurons (Fazzari et al., 2010). Nrg1 stimulates dendritic arborization of wildtype (but not ErbB4-deficient) hippocampal neurons, in a manner that requires the activity of Erbb4 and downstream PI3 kinase (Krivosheya et al., 2008). A recent report indicates that interneuronal Erbb4 colocalizes with kalirin-7, a dendritic Rac-GEF, and phosphorylates kalirin-7 on Y1663 via Src kinase (Cahill et al., 2012). Mutation of Y1663 in kalirin-7 blocks Nrg1-mediated increase of dendritic length, suggesting the involvement of kalirin-7 signaling in dendritic development. These observations also suggest that Nrg1, via Erbb4, promotes migration and development of processes in interneurons (Figure 3Ca).

Nrg/Erbb signaling also contributes to synapse formation in these circuits. It promotes the formation and maturation of excitatory synapses on GABAergic interneurons, as quantified by PSD-95 and GluA1-positive puncta and mEPSC frequency (Abe et al., 2011; Del Pino et al., 2013; Ting et al., 2011) (Figure 3B, 3Ca). Erbb4 overexpression and inactivation in GAD65+ interneurons increases and decreases, respectively, the staining intensity of synaptophysin and vGlut1, both markers of excitatory axon terminals (Krivosheya et al., 2008). In vivo genetic deletion of Erbb4 in interneurons (using Dlx5/6-Cre, PV-Cre, Lhx6-Cre mice) reduces mEPSC frequency and the density of vGlut-1+ terminals in PV+ interneurons of the hippocampus (Del Pino et al., 2013; Fazzari et al., 2010; Ting et al., 2011). However, in the medial prefrontal cortex, Erbb4 is required only for maturation, but not initial formation, of glutamatergic synapses on PV+ fast-spiking neurons in vivo (Yang et al., 2013b), perhaps reflecting a regional difference. The effect of Erbb4 on excitatory synapses may be mediated by stabilizing PSD-95 (Ting et al., 2011), which is known to promote the maturation of glutamatergic synapses (El-Husseini et al., 2000) (Figure 3B, 3Ca). In addition, postsynaptic Erbb4 may regulate presynaptic differentiation by trans-synaptic interaction with transmembrane Nrg1 or another binding partner (Krivosheya et al., 2008) (Figure 3Ca).

Likewise, Erbb4 in interneurons also promotes the formation and maintenance of GABAergic synapses onto pyramidal neurons. Chandelier cells lacking Erbb4 make fewer synapses onto the axon initial segments of pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus in vivo (Del Pino et al., 2013; Fazzari et al., 2010). Additionally, the density of interneuron axonal boutons of chandelier cells is increased by overexpressing Nrg1 Type III in pyramidal neurons (Fazzari et al., 2010). This effect, which was not observed on PV+ basket cell synapses (Del Pino et al., 2013), may be mediated by presynaptic Erbb4 interacting with Nrg1 Type III (Fazzari et al., 2010) (Figure 3B, 3Cb).

On the other hand, the role of Nrg1/Erbb4 signaling in synaptogenesis between interneurons is largely unknown. In cultures of hippocampal GABA-positive neurons, Nrg1 had no effect on puncta number and size of gephyrin, a postsynaptic scaffold protein of inhibitory synapses (Ting et al., 2011). However, ectopic expression and shRNA-mediated knockdown of Erbb4 in hippocampal GABAergic neurons were shown to increase and decrease, respectively, the intensity, but not density of vGAT-positive puncta or Syn clusters in Gad65+ neurons (Krivosheya et al., 2008). This suggests that ErbB4 may be necessary for maturation of GABAergic synapses in hippocampal interneurons, presumably via interacting with presynaptic, transmembrane Nrg1 (or other ligands) of another interneuron (Krivosheya et al., 2008) (Figure 3B and 3Cc). In a recent in vivo study, however, Erbb4 was shown to be dispensable for the formation and maturation of GABAergic synapses on PV+ fast-spiking basket cells in medial PFC (Yang et al., 2013b).

Nrg1/Erbb signaling is thought to regulate many stages of glutamatergic circuit assembly including radial migration of pyramidal neurons, neurite development and formation of excitatory synapses. Recent genetic studies have called for revisiting some established models and provided insight into underlying mechanisms. Soluble Nrg1 Type II, originally identified as ‘glial growth factor’, was thought to stimulate radial glia formation and thus promote radial neuronal migration. In imprint assays in vitro, Type II promotes cortical neuronal migration on radial glia (Anton et al., 1997). In co-culture with astroglia, cerebellar granule cells release Nrg1 to induce radial glial morphogenesis and promote the migration of granule cells along radial glia (Rio et al., 1997). In vivo, deletion of Nrg1 in multipotential progenitors of embryonic forebrains (E12.5, by Emx-Cre), in new born projection neurons of the cortex (E12.5, by NEX-Cre), or in the developing central nervous system (CNS) (E11.5, by nestin-Cre) has no effect on cortical lamination and hippocampal formation (Brinkmann et al., 2008). Moreover, the development of radial glial and astrocytes is normal in mutant mice in which Erbb2 and Erbb4 were both ablated in neural precursors at E8.5, E10.5, and E13.5 (by Nestin8-Cre, EMX1-Cre, and hGFAP-Cre, respectively) (Barros et al., 2009). Like Erbb2 or Erbb4 single mutants, these mice exhibit no abnormality in laminal structure of the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum, or loss of neuronal density in any cortical layer (Barros et al., 2009; Pitcher et al., 2008). Thus, loss-of-function studies in vivo suggest that Nrg1/Erbb signaling is dispensable for radial glia differentiation and radial migration of cortical neurons.

Nrg1 has also been shown to stimulate neurite outgrowth of excitatory neurons including hippocampal neurons and cerebellar granule cells (Gerecke et al., 2004; Murphy and Bielby-Clarke, 2008; Rio et al., 1997). This effect only occurs in Erbb4+ neurons (Cahill et al., 2012; Krivosheya et al., 2008), which are mostly GABAergic interneurons (see above) (Figure 3Ca). This may explain why viable (“heart-rescued”) Erbb4 mutant mice or conditional Erbb2/Erbb4 double mutants (using hGFAP-Cre to target neural precursors) showed normal dendritic morphology of cortical and hippocampal neurons (Barros et al., 2009). Perturbed basal dendrites and axon elaboration in cortical neurons in Nrg1 Type III mutant mice are thought to be mediated by the intracellular domain (ICD) in so-called backward signaling (Chen et al., 2010a; Chen et al., 2008)(Figure 3Cd). Although the mechanisms for this effect are unknown, the ICD of Nrg1 can regulate gene expression (Bao et al., 2004; Bao et al., 2003).

Regarding excitatory synapse formation on pyramidal neurons, conditional deletion of Erbb2 and Erbb4 in single and double mutant mice (generated by hGFAP-Cre) reduced dendritic spine density in hippocampal and cortical neurons (Barros et al., 2009). Morevoer, lentiviral infection of hippocampal slices to knockdown Erbb4 impairs spine formation (Li et al., 2007). These results are indicative of a necessary role of Nrg1/Erbb signaling. As discussed above, Erbb4 expression in the brain is restricted to interneurons in adult animals (Fazzari et al., 2010; Vullhorst et al., 2009). Besides, deletion of Erbb4 in pyramidal neurons of floxed Erbb4 mice (by retroviral Cre) or by CaMKII-Cre did not alter the density of dendritic spines or mEPSC (Fazzari et al., 2010; Yin et al., 2013b) and Erbb4 knockdown in cultured hippocampal neurons had no effect on Nrg1 induction of spines (Cahill et al., 2013). Spine reduction in mice where Erbb4 was knocked out by hGFAP-Cre or in hippocamapal slices by lentivirus may be due to a homeostatic mechanism to compensate hyperactivity of pyramidal neurons (because of hypofunction of GABAergic circuitry) (see below). In support of this notion, spines are reduced in mice that lack Erbb4 in PV+ interneurons (Del Pino et al., 2013; Yin et al., 2013b).

Nrg1 has been implicated in synthesis of neurotransmitter receptors. First identified as an acetylcholine receptor inducing activity (ARIA), it was thought to control synapse-specific gene expression and formation of the peripheral synapse (Falls et al., 1993; Sandrock et al., 1997). However, in mice lacking Nrg1 in motoneurons, muscle fibers or both cell types, Achr expression and clusters are normal (Jaworski and Burden, 2006). Moreover, mice that lack Erbb2 and Erbb4 in muscle fibers in vivo are able to form mature endplates (Escher et al., 2005; Schmidt et al., 2011). Thus, in knock-out mouse models, Nrg1/Erbb signaling is dispensable for neuromuscular junction development and its biological function remains to be defined. Long-term treatment of brain slices or neurons with Nrg1 has also been shown to alter the expression or activity of NMDA receptors, metabotropic glutamate receptors, GABA-A receptors, and neuronal Achr in cultured neurons or slices (Liu et al., 2001; Okada and Corfas, 2004; Ozaki et al., 1997; Rieff et al., 1999; Schapansky et al., 2009). However double knockout of Erbb2 and Erbb4 by hGFAP-Cre or by BACa6-Cre had no effect on expression of NMDA receptors or GABA-A receptors in vivo (Barros et al., 2009; Gajendran et al., 2009).

Myelination of axonal processes

Nrg1/ErbB signaling, which is key to neuronal circuit formation, is also important for the communication of projection neurons with axon-associated glial cells for the purpose of myelination. Myelin serves the rapid axonal impulse propagation, which is essential for long-range connectivity. To achieve myelination, oligodendrocytes (in the CNS) and Schwann cells (in the PNS) engage in complex interactions with axonal segments that become spirally enwrapped (Snaidero et al., 2014), resulting in the formation of electrically insulated ‘internodes’, separated only by widely spaced nodes of Ranvier (Emery, 2010; Nave, 2010). In higher vertebrates, myelin sheaths provide the physical basis for “saltatory” impulse propagation, which is essential for normal motor and sensory functions. In addition, myelinating glia help maintain the functional integrity and survival of axons (Griffiths et al., 1998), possibly by directly supporting the axonal energy balance (Funfschilling et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2012). Fine-tuning of myelin sheath thickness and conduction velocity is critical to maintain the temporal precision of long-range connectivity in the brain in the millisecond range. This may explain why human psychiatric diseases have been repeatedly associated with myelin and white matter abnormalities (Fields, 2008; Nave and Ehrenreich, 2014). An important research goal is to better understand the mechanisms by which glial cells select axons for myelination and are instructed to wrap the optimal number of myelin membrane layers such that the correct g-ratio (axonal diameter/myelinated fiber diameter) is reached and maintained.

At least in the PNS, axonal Nrg1 is a key signaling molecule that regulates the behavior of myelinating Schwann cells. When Schwann cells are maintained in culture, they can be stimulated by purified axonal membranes to proliferate (McCarthy and Partlow, 1976; Salzer and Bunge, 1980; Wood and Bunge, 1975). The responsible factor, glia growth factor or Nrg1 Type II, was purified and found to cause fibroblasts, Schwann cells and astrocytes to divide (Lemke and Brockes, 1984) (Figure 1). Also recombinant soluble Nrg1 Type I maintains the survival of cultured Schwann cells (Dong et al., 1995) and can be used in the laboratory for Schwann cell expansion in vitro. In vivo, however, the critical Schwann cell growth factor is Nrg1 Type III, a protein that remains associated with axonal membranes by means of a second membrane anchor. By in situ hybridization, Type III is indeed the most prominent Nrg1 isoform in motoneurons of the spinal cord and sensory neurons of dorsal root ganglia.

As Nrg1 null mutant mice die with a developmental heart failure at E11 (Meyer and Birchmeier, 1995), i.e. without informative pathology of the nervous system, the first in vivo evidence for a critical function of Nrg1/Erbb signaling in the PNS came from mutant mice lacking Erbb3 (Riethmacher et al., 1997). Some mutant embryos develop to term, but die shortly after with breathing defects that constitutes a lethal ‘neuropathy’ phenotype. Interestingly there was not only a complete lack of Schwann cells from mutant nerves, but also a loss of the majority of sensory dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons and spinal motor neurons, which are Erbb3 negative. This suggested a potential neurotropic function of Schwann cells for the survival of associated neurons.

Schwann cells express both Erbb2 and Erbb3, but not Erbb4. While Erbb2 has a strong kinase domain, it lacks receptor functions and requires hetero-dimerization with Erbb3 for Nrg1 signal transduction. Erbb3, in turn, is a functional receptor but weak kinase (Figure 1). In a first gene targeting experiment, the floxed Erbb2 gene was selectively eliminated in Schwann cells that had matured enough to express a Krox20-Cre transgene (Garratt et al., 2000). At this stage, neurons and Schwann cells are no longer mutually dependent for survival (Meier et al., 1999). Thus, the resulting neuropathy phenotype was no longer lethal, but severe enough to confirm the critical role of Erbb2 signaling for Schwann cell expansion and therefore myelination. Interestingly, when the floxed Erbb3 gene was inactivated in Cnp-Cre mice, peripheral dysmyelination was much more severe (Brinkmann et al., 2008), suggesting that a lack of Erbb2 from Schwann cells can be partially compensated for by the presence of Erbb3, but not vice versa. This is in agreement with a recent report of low but significant kinase activity of Erbb3 that is sufficient for autophosphorylation (Shi et al., 2010).

Nrg1 Type III is targeted into long axonal projections where it has multiple functions. This isoform has been implicated in axonal pathfinding of TrkA+ sensory neurons in response to Sema3A, a guidance cue in the developing spinal cord and in the periphery (Hancock et al., 2011) and in regulating functional TRPV1 along sensory neuron axons for heat sensing (Canetta et al., 2011). Its most important function is the control of Schwann cell development and peripheral myelination. Mutant embryos that lack selectively this membrane-associated isoform develop to term (Wolpowitz et al., 2000), but perinatal death in these mice is associated with a striking lack of Schwann cells and a severe reduction of DRG and motor neurons, similar to observations in Erbb3 mutants. This implicates the Nrg1 Type III isoform as essential for normal Schwann cell development. However, is there also a direct role in myelination?

The first ‘gain-of-function’ experiments, in which in vitro myelination by DRG/Schwann cell co-cultures was assessed in the presence of soluble Nrg1, reported a striking “demyelination” phenotype (Zanazzi et al., 2001). In hindsight, this may have been caused by an unphysiological presentation of Nrg1 as a soluble factor and/or the overstimulation of one of several second messenger pathways in Schwann cells (Syed et al., 2010). When Nrg1 was neuronally overexpressed in transgenic mice as an axonal surface signal and at later developmental stages, it emerged as a myelination promoting signal (Michailov et al., 2004). Moreover, by comparing transgenic mice expressing either Type I or Type III cDNA transgenes (both under control of the Thy1 promoter in DRG and motoneurons) only Nrg1 Type III emerged as the regulator of myelination. Its overexpression caused Schwann cells to ‘hypermyelinate’ axons in peripheral nerves (Figure 4), as demonstrated by g-ratio quantification. In turn, loss of gene dosage (in either heterozygous Nrg1 null or heterozygous Nrg1 Type III-null mice) caused significant ‘hypomyelination’. This suggests that in axons of the PNS, the steady-state level of Nrg1 is mainly regulated at the transcriptional level, and that Nrg1 Type III expression is rate-limiting for peripheral myelination. In contrast, heterozygosity of Erbb2 reduced the expression level of this receptor, but had no effect on myelination, in line with observations in the neurotrophin field that reduced levels of ligands (not receptors) often limit transcellular signaling. Together, these observations identified an important developmental function of Nrg1 Type III. According to this model, the total amount of Nrg1 Type III that is presented on the axonal surface provides the information about axon size to associated Schwann cells (Michailov et al., 2004). The strength of this signal determines the amount of myelin membrane synthesis that matches axon caliber and yields the ‘optimal’ g-ratio for nerve conduction. A major unresolved question is how the rate of neuronal Nrg1 expression is regulated in the first place, i.e. as a function of axon caliber and length, and how axonal Nrg1 TypeIII affects expression of the glial Erbb gene itself (Schulz et al., 2014) and thus Schwann cell responsiveness.

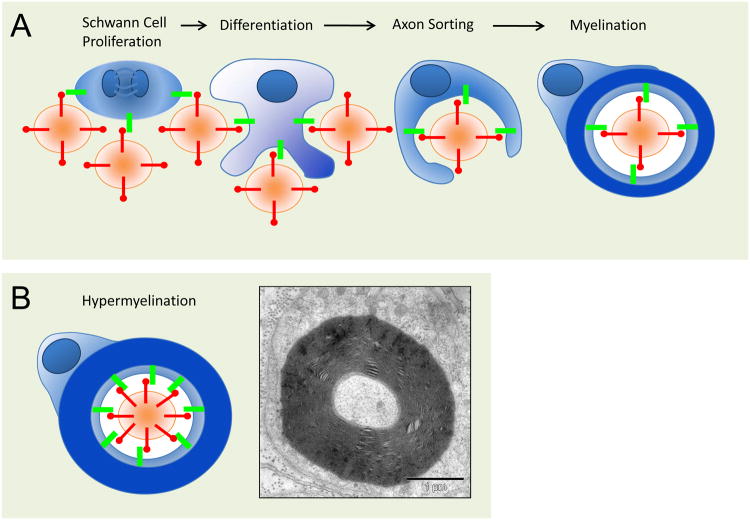

Figure 4. Nrg1 Type III in Schwann cell myelination.

A, Schematic depiction of Schwann cells and their precursors (in blue) stimulated by axons (in cross section, brown) through all stages of the Schwann cell lineage, i.e. from the proliferating precursors (left) to myelinating Schwann cells (right). Glial Erbb receptors (green) integrate Nrg1 Type III (red) signals from the axon surface, generating intracellular second messenger signals as surrogates of axon size. Thus threshold levels of axonal NRG1 initiate myelination once the axon caliber measures about 1 μm. B, Transgenic overexpression of Nrg1 Type III increases the density of this ligand on the axon surface causing significant hypermyelination, without increase of axon caliber.

In PNS development, large axons are sorted and individually myelinated by associated Schwann cells, whereas C-fiber axons with a diameter < 1 μm are engulfed in groups (‘Remak bundles’) by so-called ‘non-myelinating’ Schwann cells. This sorting is determined by axon size, as demonstrated in a classic experiment (Voyvodic, 1989), in which sympathetic C-fiber axons of the submandibular salivary gland became artificially enlarged after hemisection of the nerve (and increased neurotropic supply to the surviving axons). This radial growth of sympathetic axons triggered the associated Schwann cells to sort and myelinate them. Expression level of axonal Nrg1 may provide information about axon size. In co-cultures of non-myelinated sympathetic ganglion neurons from Nrg1 Type III null mutant mice and Schwann cells, the viral overexpression of Nrg1 Type III in neurons causes Schwann cells to ensheath individual axons (Taveggia et al., 2005). Conversely, in Nrg1 Type III isoform-specific heterozygous mice, a greater proportion of small caliber axons remained unsorted, and in Nrg1 Type III null mutants even large-caliber axons remain completely unensheathed (Taveggia et al., 2005). Although continued Nrg1/Erbb signaling is not required once myelination has been completed (Atanasoski et al., 2006; Fricker et al., 2009), myelin repair in the peripheral nerves of adult mice recapitulates some of the developmental steps and depends on Nrg1/Erbb signaling, but is considerably more complex (see below).

Nrg1/Erbb-dependent second messenger pathways in Schwann cells

In PNS development neuronal Nrg1 TypeIII molecules are presented on the axon surface where they stimulate the associated Schwann cell to initiate sorting and myelination. It is therefore puzzling that 20 or more C-fiber axons (<1 μm in diameter) can be associated with a single Schwann cell (in a ‘Remak bundle’) without reaching in sum the ‘threshold level’ of stimulation that is obviously reached by a single axon > 1 μm in diameter. This paradox might be explained by Erbb2/Erbb3 downstream mechanisms that initiate membrane outgrowth by altering actin and membrane dynamics, and that act locally at each axon-glia interface (Sparrow et al., 2012). For example the activity of PI3K at the cell membrane (Heller et al., 2014) is likely regulated by the polarity of myelinating Schwann cells towards a single axon, which Remak cells may not show as such towards the many axons they engulf. In other systems PI3K-dependent elevation of phosphoinositide-3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) recruits proteins that establish cell polarity, such as Par3, which is essential for myelination (Chan et al., 2006). Interestingly, Par3 localizes at the axonal interface of Schwann also as a result of BDNF signaling, i.e. possibly independent of Nrg1/Erbb signaling (Tep et al., 2012).

The response of Schwann cells to axonal Nrg1 is complex. The Erbb2 kinase has been shown to associate with Erbin, a PDZ-domain scaffold protein with multiple leucine-rich repeats (Borg et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2001), and this interaction may regulate Nrg1 signaling by regulating Erbb2 stability or MAP kinase pathway (Huang et al., 2003; Tao et al., 2009).Erbin has also has been implicated in myelin formation and remyelination after injury (Liang et al., 2012; Tao et al., 2009). Another ErbB-associated scaffolding protein required for myelination is Grb2-Associated Binder-1 (Gab1) (Shin et al., 2014).

ErbB receptor activation triggers multiple second messengers in Schwann cells (for details see also Colognato and Tzvetanova, 2011; Taveggia et al., 2010). Activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway (Maurel and Salzer, 2000; Taveggia et al., 2005), the Shp2/Erk/MAPK pathway (Grossmann et al., 2009; Newbern et al., 2011), and the PLC/Calcineurin/NFAT pathway (Kao et al., 2009) are all critical for myelination (Figure 1). These pathways affect Schwann cells and their gene expression program rather globally. In contrast, Nrg1/Erbb-dependent and integrin-mediated stimulation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and the small GTPases Cdc42 and Rac1 provide additional local signals at the axon-glial interface. These enhance actin dynamics underneath the Schwann cell membrane and enable the very first steps of myelination, i.e. radial sorting of axons (Grove et al., 2007) and initial membrane outgrowth (Benninger et al., 2007; Nodari et al., 2007).

Indeed, experimental elevation of the lipid phosphatidylinositol-(3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) in mutant Schwann cells that lack the lipid phosphatase PTEN is associated with hypermyelination of small axons. Moreover, there is abnormal wrapping of C-fiber axons but this ‘myelin’ is not compacted (Goebbels et al., 2010). C-fiber wrapping is not seen when a constitutive active form of Akt is overexpressed in Schwann cells (Flores et al., 2008). Thus, enhanced PI3K signaling is clearly only part of the complex Schwann cell response to Nrg1 Type III. By itself elevated PIP3 may promote membrane outgrowth and wrapping but, in the absence of Erk/MAPK stimulation, not the entire program of myelination. In the same PTEN-deficient conditional mouse mutants, larger axons develop abnormal myelin hypergrowth (‘tomacula’) with all the features of human tomacular neuropathy (Goebbels et al., 2012). Taken together, careful regulation of the (Nrg1 Type III-dependent) PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway is also important in adult mice in that PTEN puts a local ‘brake’ on abnormal myelin synthesis (Cotter et al., 2010). Interestingly, activation of the Erk/MAPK pathway, which plays a major role in Nrg1 induced peripheral myelination (Newbern and Birchmeier, 2010), can cause hypermyelination under experimental conditions, without corresponding changes of myelin gene transcription. This suggests a major role of posttranscriptional regulation of myelin growth (Sheean et al., 2014).

Processing of Nrg1 activates a myelination signal

Biologically active Nrg1 is generated by proteolytic processing from a larger membrane-bound precursor protein, which prompted the analysis of neuronal metalloproteases as candidate “sheddases” (Figure 2). These experiments identified β-secretase BACE1, already well known for its ability to process the amyloid precursor protein, as a critical enzyme for the activation of Nrg1. Indirect evidence included the abundance of ‘full-length’ Nrg1 in the brains of Bace1 null mutant mice, which have a hypomyelinated phenotype specifically in the PNS (Hu et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2006; Luo et al., 2011; Treiber et al., 2012; Willem et al., 2006). Myelin sheath thickness is an easily quantifiable readout for Nrg1 activity and its modulation by prior protein processing. Bace1 is likely not the only relevant protease, because in Bace1 null mutant mice there is a residual presence of processed Nrg1 isoforms (Velanac et al., 2012). As for Type III, it is still unclear whether the proteolytic processing is essential for biological activity, or whether pro-Nrg1 can stimulate Schwann cells to some extent. Additional complexity of Nrg1 processing emerged with the finding that the metalloprotease TACE1 (‘tumor necrosis factor-alpha converting enzyme’/ADAM17) also digests membrane-bound Nrg1 (Montero et al., 2000), but closer to the EGF-like domain and presumably antagonizing the role of BACE1 as a myelination-promoting factor (La Marca et al., 2011). At least in the PNS, the β1 splice variant of Nrg1 (Falls, 2003) is by far the most abundant one. Other isoforms of the juxtamembrane region have not been analyzed in detail, and it is possible that these sequence differences affect proteolytic processing. Finally, the zinc protease Nardilysin (‘N-Arginine dibasic convertase’/NRDc) activates other metalloproteases, i.e. TACE1 (Nishi et al., 2006) and BACE1 (Ohno et al., 2009) and thus promotes Nrg1 processing and myelination, as evidenced by the hypomyelinated phenotype of NRDc mutant mice. The discovery that ‘activated’ Nrg1 Type III can be further processed leading to the release of the EGF dimain (Fleck et al., 2013) suggests that the paracrine signal may also diffuse in the periaxonal space before binding to Erbb receptors on the adaxonal Schwann cell surface.

Given that the shedding of Nrg1 from axons can also be regulated by glial-derived neurotrophins, developmentally regulated Nrg1 processing is clearly complex. We assume that similar neuronal proteases activate synaptic Nrg1/Erbb signaling (see below) but this has not been formally shown. Equally important, the relevant subcellular compartments in which Nrg1 processing takes place, remain to be defined and this may be different for neuron-to-neuron and neuron-to-glia signaling.

Schwann cell-derived Nrg1 Type I promotes myelin repair

When maintained in culture, Schwann cells express Nrg1 Type I (but not Type II or Type III), but the function of the Type I isoform has remained obscure. Autocrine stimulation by Nrg1 Type I can be observed in lung cancer cells that also express Erbb2/Erbb3 receptors (Gollamudi et al., 2004) and similarly in neoplastic growth of Schwann cells (Stonecypher et al., 2006). Forced Nrg1 Type III overexpression can induce Schwann cell transformation (Danovi et al., 2010). Could an “autocrine loop” of Nrg1/Erbb signaling also support Schwann cell survival during development or following nerve injury? When injured axons undergo Wallerian degeneration and quickly disintegrate, the associated Schwann cells follow with a rapid de- differentiation program (Arthur-Farraj et al., 2012). At this stage they lack normal axonal contact and Nrg1 Type III stimulation, and begin to transiently upregulate Nrg1 Type I expression. Exposure to axonal Nrg1 Type III suppresses this expression of Nrg1 by Schwann cells, depending on glial Erbb receptors and MAPK signaling (Stassart et al., 2013). Specific deletion of Nrg1 from Schwann cells has no obvious effect on normal development and myelin growth. However, the remyelination of crushed nerves becomes inefficient in these conditional mutants (Stassart et al., 2013). Schwann cell survival is not affected, suggesting that Nrg1 autoregulation promotes rapid remyelination in the transient absence of this axonal growth factor (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Nrg1 in remyelination of the PNS after nerve injury.

In intact nerves, axonal Nrg1 Type III controls myelination and inhibits Nrg1 Type I expression by Schwann cells. Following Wallerian degeneration, Schwann cells are detached and the axonal Nrg1 Type III signal is lost. At this stage, expression of Nrg1 Type I by Schwann cells is ‘de-repressed’ and promotes Schwann cell differentiation and remyelination in a transient autocrine/paracrine signaling loop (from Stassart et al., 2013 with permission to be obtained).

Schwann cell-derived Nrg1 may also contribute to axonal regeneration itself (Joung et al., 2010), but whether this is a direct or indirect effect awaits further analysis. A recent report that remyelination (after crush injury of the sciatic nerve) is possible in adult mice that were made to completely lack Nrg1 from virtually all cells by β-actin controlled Cre expression and tamoxifen-induced gene targeting is surprising (Fricker et al., 2013). The responsible growth factor that might compensate for axonal Nrg1 remains to be defined. However, precedent for Nrg1-independent myelination comes from the CNS.

Distinct roles in PNS and CNS myelination

Myelinated neurons in both the PNS and CNS express Nrg1 Type III. With respect to Nrg1 receptors Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes differ by expressing Erbb2/Erbb3 and Erbb3/Erbb4, respectively (Vartanian et al., 1997). Despite these similar expression patterns and even though axons that enter and exit the spinal cord are clearly myelinated in both PNS and CNS, unexpectedly, the axonal control of myelination is remarkably dissimilar in the PNS and CNS. Earlier studies with spinal cord explant cultures from mid-gestation (E9.5) Nrg1 null mutant mice had shown that the failure of oligodendrocyte differentiation in vitro could be rescued by adding recombinant Nrg1 to the culture medium (Vartanian et al., 1999). Surprisingly, experimental perturbations of Nrg1 signaling in vivo revealed only minor differences. The conditional inactivation of Nrg1 expression in mice, using various neuron-specific Cre driver lines, was compatible with normal CNS myelination (Brinkmann et al., 2008). Specifically, deletion of Nrg1 in pyramidal neurons of the cortex (by CaMKII-Cre), in projection neurons of the cortex (by NEX-Cre), in multipotential progenitors of the embryonic forebrain (by Emx-Cre), or in the entire CNS (by nestin-Cre) had no quantifiable effect on the myelination of axons in the corpus callosum and within the neocortex, or on the branching and morphology of oligodendrocytes (Brinkmann et al., 2008). Likewise, Erbb3 and Erbb4 receptors were not required for the timely differentiation of oligodendrocytes and CNS myelination (Brinkmann et al., 2008; Schmucker et al., 2003; Tidcombe et al., 2003), but these double mutant mice could only be followed for the first postnatal weeks.

It is currently unclear why the complete lack of Nrg1 expression in conditional mutants shows less effect on CNS myelination than mere reduction of Erbb signaling does. The 50% gene dosage in Nrg1 TypeIII-specific heterozygous mice (Wolpowitz et al., 2000) reportedly causes mild hypomyelination of the CNS (Taveggia et al., 2008) and mice that overexpress a truncated (dominant-negative) version of the Erbb4 receptor in oligodendrocytes show signs of cortical hypomyelination (Roy et al., 2007). Recently, the same group associated reduced Nrg1-Erbb signaling within a “critical period” of myelination in the prefrontal cortex (PFC). Mice separated from their mothers during early postnatal life (“social isolation stress”) showed reduced Nrg1 expression and this was reminiscent of PFC hypomyelination in conditional mouse mutants lacking Erbb3 from mature oligodendrocytes after tamoxifen induction (Makinodan et al., 2012). Social isolation may reduce the spiking activity of PFC neurons, thereby perturbing Nrg1-Erbb signaling and myelination. The alternative possibility must be considered that isolation-associated stress is co-responsible for perturbing oligodendrocyte differentiation (Banasr et al., 2007; Czeh et al., 2007);reviewed in (Edgar and Sibille, 2012). Elevated cortisol levels have been found to inhibit myelination in the postnatal brain (Alonso, 2000; Chari et al., 2006). While social isolation has been independently linked to altered oligodendrocyte differentiation (Liu et al., 2012), the mechanism by which electrical activity would regulate Nrg1 expression awaits to be determined. In fact, an alternate model has been suggested based on cell culture data in that Nrg1 triggers the responsiveness of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPC) to electrical activity and glutamatergic signaling by axons both of which promotes myelination. In co-cultures of DRG neurons with OPC, soluble Nrg1-mediated myelination is dependent on neuronal activity and is associated with NMDAR upregulation on oligodendrocyte lineage cells (Lundgaard, et al 2014).

The biological function of neuronal/axonal Nrg1 in the CNS and for Erbb3 and Erbb4 receptors expressed by oligodendrocytes has remained difficult to define by conventional loss-of-function experiments. In contrast, transgenic overexpression of Nrg1 Type III (and unexpectedly also Type I) in CNS neurons under control of the Thy1.2 promoter caused significant hypermyelination and some precocious myelination, when quantified in the optic nerve of early postnatal mice (Brinkmann et al., 2008). Thus, oligodendrocytes respond to Nrg1 stimulation in vivo. However, in these experiments Nrg1 overexpression levels were very high (5-fold at the RNA and >10 fold at the protein level), drawing into question the specificity of this observation. Stimulation of other receptor systems in oligodendrocytes that likewise activate PI3K and MAPK pathway exerts similar effects (Lundgaard et al., 2014). CNS hypermyelination has been observed many years earlier in transgenic mice that overexpress IGF1 under control of a ubiquitously active promoter (Carson et al., 1993).

Regulation of neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity

Once postnatal brain development has been completed, Nrg1/Erbb expression continues in the adult nervous system most likely with functions in neurotransmission and neuroplasticity. In adult brain, Nrg1 and Erbb kinases remain widely expressed (Mei and Xiong, 2008), and postsynaptic Erbb4 in particular is enriched at excitatory synapses where it interacts with PSD-95 (Garcia et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2000). Indeed, the treatment of adult hippocampal slices with soluble Nrg1 (the EGF-like signaling domain synthesized as a polypeptide) rapidly suppresses, in a concentration-dependent manner, the induction of long-term potentiation (LTP) at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses (Huang et al., 2000). The effect is abolished by genetic deletion of Erbb4 (Chen et al., 2010b; Pitcher et al., 2008). Moreover, neutralization of endogenous Nrg1 and mutation of Erbb4 both enhance hippocampal LTP, indicating that synaptic plasticity is regulated by Nrg1 in vivo (Chen et al., 2010b; Pitcher et al., 2008; Agarwal et al., 2014).

Glutamate has two major inotropic receptors a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPAR) and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR). There is a general consensus that Nrg1 does not change basal synaptic transmission, such as AMPAR- or NMDAR-induced currents in hippocampal CA1 neurons (Bjarnadottir et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2010b; Huang et al., 2001; Iyengar and Mott, 2008) or in cultured cerebellar granule neurons (Fenster et al., 2012). Nevertheless, Nrg1 was shown to reduce AMAPR EPSCs at potentiated synapses, presumably by increasing AMPAR endocytosis in hippocampal neurons. This effect was thought to be a responsible mechanism of LTP reversal by Nrg1 detected 20 min after theta-burst stimulation (TBS) (Kwon et al., 2005). However, established LTP cannot be reversed by Nrg1 when applied 30 min after TBS (Pitcher et al., 2011), which may suggest time-dependence of the effect. Nrg1 could also attenuate NMDA receptor currents in PFC neurons in vitro (Gu et al., 2005). Whether and how these observations relate to a physiological mechanism by which Nrg1 regulates synaptic plasticity require further investigation (see below).

Erbb4 is expressed in dopaminergic neurons of the midbrain (Abe et al., 2009; Neddens and Buonanno, 2011; Steiner et al., 1999; Zheng et al., 2009). Injection of Nrg1 just dorsal to the substantia nigra increases dopamine levels in the midbrain (Yurek et al., 2004). Delivery of Nrg1 into the dorsal CA1 region increased local dopamine levels within 2 minutes (Kwon et al., 2008). Thus, Nrg1 can acutely promote dopaminergic transmission. This effect was blocked by pharmacological inhibitors of Erbb4 kinase. How Nrg1 promotes dopamine release remains unclear because Erbb4 was undetectable on dopaminergic fibers in the hippocampus or on Gad67+ or TH+ neurons in the VTA (Kwon et al., 2008). Nrg1 may elevate dopamine release via a disinhibitory circuit consisting of Erbb4-positive interneurons (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Nrg1 in neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity.

A, B, Schematic diagrams of circuitry in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Ca, Nrg1 activates Erbb4 in interneurons and promotes GABA release by altering excitability and/or vesicle release to suppress LTP. Cb, Nrg1 inhibits Src activation in pyramidal neurons to suppress LTP. Cc, Nrg1 stimulates dopamine release in the hippocampus and suppresses LTP in a manner that requires D4R. Cd, Transmembrane Nrg1 (tmNrg1) such as Type III initiates backward signaling to promote presynaptic α7-AChR expression which is required for converting short term potentiation (STP) to LTP at cortico-BLA synapses. See text for details.

In adult brain, ErbB4 receptors are localized at excitatory synapses on interneurons (Fazzari et al., 2010; Ting et al., 2011). They are also present in terminals of PV+ basket and chandelier interneurons (Fazzari et al., 2010; Woo et al., 2007) although some reports have disputed this view (Neddens and Buonanno, 2011; Vullhorst et al., 2009). One function of Erbb4 is to promote GABA release, which can be increased by soluble Nrg1 (Chen et al., 2010b; Woo et al., 2007). This effect cannot be blocked by inhibition of various neurotransmitter receptors, suggesting that Nrg1 acts directly on interneurons (Woo et al., 2007). Importantly, treatment with a neutralizing peptide (or deletion of the Erbb4 gene) reduces GABAergic transmission, increases the firing of pyramidal neurons, and enhances LTP in brain slices (Chen et al., 2010b; Pitcher et al., 2008; Wen et al., 2010; Woo et al., 2007). These observations suggest that GABAergic activity may be under control of endogenous Nrg1. By regulating GABAergic neurotransmission, which is known to be critical for controlling and synchronizing the activity of pyramidal neurons, Nrg1 may be involved in a wide spectrum of brain functions, from autonomic control of blood pressure (Matsukawa et al., 2013) to cognition (see below). In agreement, gamma oscillation in slices was reduced in Erbb4-null mutant slices (Fisahn et al., 2009). Additionally, neuronal activity associated with limbic seizure increases Nrg1-Erbb4 signaling (Tan et al., 2012). Loss of Erbb4 from PV+ interneurons promotes kindling progression and leads to an increase of spontaneous seizures (Li et al., 2012b; Tan et al., 2012).

How Nrg1 stimulates GABA release from interneurons warrants further investigation. One hypothesis posits that the activation of presynaptic Erbb4 at axon terminals increases GABA release, because Nrg1 treatment of purified synaptosomes increases GABA secretion (Woo et al., 2007). Alternatively, Nrg1 was shown to elevate the excitability of fast spiking PV+ interneurons in mouse cortical layers 2-3, presumably by inhibiting Kv1.1 in an Erbb4-dependent manner (Li et al., 2012b). However, such effect was not observed in dissociated Erbb4-expressing neurons of the hippocampus (Janssen et al., 2012) or granule cells that respond to Nrg1 (Yao et al., 2013). Instead, Nrg1 was shown to decrease voltage-gated sodium channel activity in hippocampal interneurons and thus to reduce their excitability (Janssen et al., 2012). A recent study reported that Erbb4 promotes endocytosis of GABAARa1 in cultured interneurons, in a manner independent of its kinase activity (Mitchell et al., 2013).

Acute treatment with Nrg1 is unable to suppress LTP in the hippocampus when Erbb4 is ablated in PV+ cells (Chen et al., 2010b; Shamir et al., 2012). In comparison, deletion of the same Erbb4 gene in pyramidal neurons has little effect on LTP induction or suppression of LTP by Nrg1 (Chen et al., 2010b). Clearly, Erbb4 in interneurons plays a key role in regulating LTP, but how? A few models have emerged from recent studies (Figure 6). In the first model, Nrg1 via activating Erbb4 in interneurons promotes GABAergic transmission and thus inhibits the firing of pyramidal neurons (Wen et al., 2010) and suppresses LTP (Chen et al., 2010b) (Figure 6Ca). This model explains Nrg1 suppression of LTP in the absence of GABA-Aantagonists (Bjarnadottir et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2010b). The acute LTP inhibiting effect of Nrg1 was also observed when GABA-A receptor was blocked (Kwon et al., 2005; Pitcher et al., 2011). This could suggest the involvement of a GABA-A receptor-independent mechanism or differences in preparation or sensitivity to GABA-A receptor blockade.

In the second model, Nrg1/Erbb4 signaling is thought to inhibit Src kinase and thereby block the enhancement of NMDAR function in pyramidal neurons that are injected with a Src-activating peptide (Pitcher et al., 2011) (Figure 6Cb). This study is provocative because in most if not all occasions, Erbb activation stimulates, but does not inhibit, Src or Src-like kinases (Kim et al., 2005; Olayioye et al., 1999). In fact, Erbb4 has been shown to interact with and thus activate Fyn, a Src-like kinase, in response to Nrg1 stimulation (Bjarnadottir et al., 2007). Moreover, Nrg1/Erbb4 activates Src to phosphorylate kalirin-7 in interneurons (Cahill et al., 2012). Therefore, it would be necessary to know whether Nrg1-mediated blockade of NMDAR activity enhancement requires Erbb4 in pyramidal neurons or interneurons. If Erbb4 in interneurons is required, Src inhibition by Nrg1 may result from a circuitry event, i.e., GABA release from interneurons (Figure 6Cb).

A third model implicates dopamine and D4 dopamine receptor (D4R) in regulation of LTP (Figure 6Cc). Nrg1-mediated reversal of hippocampal LTP is attenuated by pharmacological inhibition or genetic deletion of D4R (Kwon et al., 2008). D4R belongs to inhibitory D2-like dopamine receptor (Kebabian and Calne, 1979) and is expressed in not only pyramidal and GABAergic interneurons, but also dopamine neuron axon terminals as well (Noain et al., 2006; Svingos et al., 2000). Postsynaptic D4R suppresses firing and excitability of pyramidal neurons (Rubinstein et al., 2001); D4R activation augments the inactivation of synaptic NMDAR-mediated currents during LTP induction (Herwerth et al., 2012). DA released by Nrg1 may inhibit LTP through D4R in pyramidal neurons. However, this mechanism would not explain why DA selectively activates D4R to suppress LTP, but not D1-type receptors that promote LTP (Frey et al., 1991; Huang and Kandel, 1995; Lisman and Grace, 2005; Otmakhova and Lisman, 1996). Future work is needed to determine whether Erbb4 is necessary (and in what neurons) for induced dopamine release and to determine whether D4R regulates dopamine release in the hippocampus. A recent study indicates that D4R and Erbb4 immunoreactivity overlap in a subset of PV+ interneurons in the CA3 region (Andersson et al., 2012). Because dopamine can promote GABA release (Harsing and Zigmond, 1997), D4R may regulate LTP by boosting the function of PV+ GABAergic neurons.

At the level of cortical–amygdala neural circuits, high-frequency electrical stimulation of cortical inputs and TBS together with nicotine exposure elicits LTP. This plasticity is impaired in Nrg1 Type III heterozygous mice (Jiang et al., 2013). Here Nrg1 Type III is believed to target nicotinc α7 AChR to the presynaptic terminal in cortical projection neurons (Hancock et al., 2008; Zhong et al., 2008) and thus modulate excitatory plasticity at cortical-amygdala synapses (Chen et al., 2008; Jiang et al., 2013) (Figure 6Cd). In slices, the addition of soluble Erbb4-ECD partially rescues LTP deficits although it is unclear whether the backward signaling is via interaction with Erbb4 on interneurons or through some other mechanism or both.

Susceptibility genes for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression

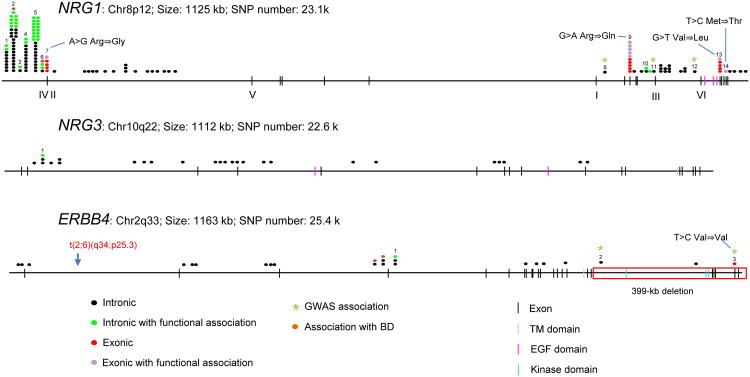

Given the broad-range functions of Nrg/Erbb signaling networks in key neural circuits in the brain, both during development and in the adult, it can be assumed that Nrgs and Erbbs may also contribute to neuropsychiatric diseases. Indeed, many NRGs and ERBBs have been suggested to play a role in schizophrenia (SZ), and other psychiatric disorders, including bipolar disorder and major depression. In this section, we will review the evidence in support of this link. SZ is a ‘complex’ disease with 80% heritability, but except for DISC1 in one pedigree virtually no SZ “disease gene” shows Mendelian genetics, high penetrance or, in association studies, major odd ratios. Identification of a locus on chromosome 8p21-p22 by genetic linkage and subsequent fine mapping and haplotype-association analysis in schizophrenic patients from Iceland led to the identification of NRG1 as a candidate gene (Stefansson et al., 2002). Independently, a study of Chinese Han SZ family trios revealed additional SZ-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on NRG1 (Yang et al., 2003). The genetic association between NRG1 and SZ has been supported by most but not all studies and meta-analyses in various populations (Li et al., 2006; Munafo et al., 2006; Norton et al., 2006; Petryshen et al., 2005) including recent genome wide association studies (GWAS) (Agim et al., 2013; Athanasiu et al., 2010; Shi et al., 2009; Sullivan et al., 2008) [see also (Mei and Xiong, 2008)]. The human NRG 1 gene is very large, spanning 1,125 kb and harboring 23,094 SNPs, ∼40 of which have been associated with SZ so far. Most of these SNPs are intronic or in the 5′ or 3′ non-coding regions, except a few in exons (Figure 7). Increasingly ‘phenotype-based genetic association studies’ (PGAS) have provided biological and pathophysiological insight into SZ ‘risk’ genes (Ehrenreich and Nave, 2014), including NRG1.

Figure 7. NRG1, NRG3 and ERBB4 SNPs and association with psychiatric disorders.

Chromosome location, size, and the total number of SNPs of NRG1, NRG3 and ERBB4 are described under each gene name. Each oval represents a case study. Colors indicate intronic or exonic SNPs with or without functional association, or SNPs associated with bipolar disorder. *, SNPs implicated by GWAS. For Nrg1, 1, rs73235619/Snp8nrg221132; 2, rs35753505/SNP8NRG221533; 3, rs4623364/SNP8NRG222662; 4, rs62510682/SNP8NRG241930; 5, rs6994992/SNP8NRG243177; 6, rs7014762; 7, SNP8NRG433E1006; 8, rs4316112; 9, rs3924999; 10, rs2439272; 11, rs10095694; 12, rs16879809; 13, rs10503929; and 14, rs74942016. For Nrg3, 1, rs10748842. For ErbB4, 1, rs7598440; 2, rs1851196; and 3, rs3748962.

In SZ patients, intronic SNPs, including those in the original Icelandic “at risk” haplotype (in particular SNP8NRG221533 and SNP8NRG243177) have been associated with reduced prepulse inhibition (PPI), a measure of inhibitory sensorimotor gating, and alterated activity of frontal and temporal lobes, higher risk for development of psychotic symptoms and reduction in premorbid IQ (Hall et al., 2006; Hong et al., 2008; Roussos et al., 2011). Individuals who carry the SNP8NRG243177 (T/T) genotype develop psychosis or express more unusual thoughts during conflict-related interactions, suggesting that this SNP is related to the onset of positive symptoms (Keri et al., 2009; Papiol et al., 2011). In healthy subjects, SNP8NRG221533 is associated with decreased verbal fluency (Kircher et al., 2009; Schmechtig et al., 2010), whereas SNP8NRG243177 relates to reduced spatial working memory capacity (Kattoulas et al., 2011). Interestingly, compared to other SZ patients, carriers of both SNPs have been associated with increased brain activity, better creativity or intellectual achievement (Keri, 2009; Krug et al., 2008; Krug et al., 2010). Moreover, both SNPs have been associated with a reduced volume of white and grey matter or increased lateral ventricle volume in minimally medicated patients experiencing first episode of SZ (Barnes et al., 2012; Cannon et al., 2012; Mata et al., 2010). Similarly, the SZ risk allele ‘C’ of SNP8NRG221533 is associated with decreased fractional anisotropy (a measure of white matter integrity) in subcortical white matter of the frontal lobe (Winterer et al., 2008) and SNP8NRG243177 relates to reduced structural connectivity in the internal capsule (McIntosh et al., 2008). These results are compatible with the idea that NRG1 SNPs contribute to the risk for SZ, in part, by affecting some aspect of human myelination that could not be modeled in Nrg1 mutant mice (Brinkmann et al., 2008).

Because the SNPs of the Icelandic haplotype are intronic and reside in the NRG1 5′ region, it is plausible that they affect gene expression by transcriptional or epigenetic modifications. NRG1α and Type I in the brain or Ig-NRG1 in serum were reported to be lower in SZ patients (Bertram et al., 2007; Parlapani et al., 2010; Shibuya et al., 2010). However, there are more studies reporting increased mRNA levels of NRG1 Type I, II, and IV in the PFC and/or hippocampus of autopsy material from SZ patients (Hashimoto et al., 2004; Law et al., 2006; Parlapani et al., 2010; Weickert et al., 2012) as well as in neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells of SZ patients (Brennand and Gage, 2012). Increases in Type I and IV mRNA relate to SNP8NRG221132 and SNP8NRG243177, respectively (Law et al., 2006; Moon et al., 2011). The picture for Type III expression is less clear. In one study, a SNP in the NRG1 5′ core promoter region (rs7014762) was associated with SZ and significantly predicted reduced NRG1 Type III mRNA levels in a US Caucasian population (Nicodemus et al., 2009). In another, the Icelandic haplotype was associated with increased Type III mRNA expression in the PFC in an Australian cohort of SZ patients (Weickert et al., 2012). NRG1 Type III transcripts amplified from peripheral leukocytes are higher in SZ patients (Petryshen et al., 2005). Importantly, the increase in NRG1 transcript and protein levels in patients did not correlate with antipsychotics treatment (Chong et al., 2008; Law et al., 2006; Weickert et al., 2012), suggesting the association is indeed with the disorder and not medication. Notice that NRG1 Type III mRNA is more abundant than Types I and IV mRNAs in human brains (Liu et al., 2011). At a global level, changes in absolute mRNA copy number for Type I and IV in SZ patients are expected to be smaller than those of Type III. However, the situation may be different at the single cell level or in a specific brain region. Abundantly expressed isoforms (such as Type III) may be more resilient in biological consequences to small expression changes. In addition to higher NRG1 levels in postmortem PFC of SZ patients, a marked increase was observed in NRG1-induced phosphorylation of ERBB4 kinase (Hahn et al., 2006). This suggests NRG1 signaling activity is indeed increased in relevant brain regions of schizophrenic patients.

Four NRG1 exonic SNPs are nonsynonymous. SNP8NRG433E1006 changes Arg to Gly in the Type II-specific N-terminal region, whereas rs3924999, rs10503929, and rs74942016 affect amino acids in the Ig, stalk and transmembrane domains, respectively, which are contained in many isoforms (Falls, 2003; Mei and Xiong, 2008). These changes have been associated with reduced PPI or cognition deficits in SZ patients or with schizotypal personality disorder (Hong et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2005; Roussos et al., 2011). Intriguingly, rs10503929, which specifies a missense mutation (V321L) in the C-terminal transmembrane domain (Walss-Bass et al., 2006), impairs γ-secretase cleavage of Nrg1 (Dejaegere et al., 2008) and therefore perturbs Nrg1 Type III singaling via the intracellular domain and Nrg1 ‘back signaling’ (Chen et al., 2010a).

NRGs and ERBB kinases show considerable crosstalk within this family of ligands and receptors. SZ-associated SNPs have been identified not only in NRG1, but also in NRG2, NRG3 and NRG6 as well as in all ERBB genes, i.e. EGFR, ERBB2, ERBB3 and ERBB4 (Benzel et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009; Mei and Xiong, 2008). ERBB3 was reported to be lower in postmortem brain of SZ patients (Aston et al., 2004). Among them, NRG3 and ERBB4 have been better characterized. Fine mapping of chromosome 10q22, a SZ susceptibility locus, led to the identification of three intronic SNPs in intron 1 of NRG3 that were associated with delusion symptom severity in patients with SZ of Ashkenazi Jewish decent (Chen et al., 2009). Association of these SNPs with SZ was observed in a family-based study (Kao et al., 2010). Subsequently, more than 20 SNPs in NRG3 have been identified by case control studies and studies of rare copy-number variants (Meier et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2009) (Figure 7). Some are significantly associated with psychotic symptoms and attention performance SZ (Kao et al., 2010; Meier et al., 2012) or prefrontal cortical physiology in working memory (Tost et al., 2014; Rasetti et al., 2011), whereas others relate to better performance in the ‘degraded-stimulus continuous performance’ task, suggesting that NRG3 may regulate attention processes for perceptual sensitivity and vigilance (Morar et al., 2011). A risk SNP that lies within a DNA ultra-conserved element strongly predicts elevated brain expression of NRG3 splice isoforms in SZ patients and normal controls (Kao et al., 2010). In mice, Nrg3 expression in the prefrontal cortex and knockout increased and decreased, respectively, impulsivity, a symptom of schizophrenia (Loos et al., 2014).

Many ERBB4 SNPs have been associated with SZ in genetic association (Lu et al., 2010; Nicodemus et al., 2010; Silberberg et al., 2006) and in GWAS (Agim et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2009) (Figure 7). Partial deletion of the ErbB4 kinase domain in a schizophrenic patient has been identified by genome-wide copy number analysis (Walsh et al., 2008). However, ERBB4 transcript as well as protein is higher in the PFC of schizophrenic patients (Chong et al., 2008; Law et al., 2007; Silberberg et al., 2006) (Joshi et al., 2014). Notably, the isoform with the extracellular JMa domain (that contains a proteolytic site) and the CYT-1 domain (that contains the sole binding site for PI3K) is overexpressed in the postmortem dorsal lateral PFC (DLPFC) (Law et al., 2007; Silberberg et al., 2006). This increase is associated with the ERBB4 risk haplotype of three SNPs (rs7598440, rs839523, and rs707284) (Law et al., 2007). Of particular interest is rs7598440, which predicts cortical GABA concentration in healthy subjects in a magnetic resonance spectroscope study (Marenco et al., 2011) and GABA levels in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (Luykx et al., 2012). The effect of ERBB4 was independent of GAD67 (also known as GAD1) SNPs previously shown to predict GABA levels in same cohort (Marenco et al., 2010). Elevated ERBB4 mRNA is related to interneuron deficits in the PFC in SZ patients (Joshi et al., 2014). Together, these results of SZ patients suggest GABAergic pathway as a target of ERBB4 mutation, in agreement with studies of mouse models that reveal critical roles of ERBB4 in development and function of the GABA circuitry (as discussed above). The ERBB4 risk haplotype is associated with high levels of PIK3CD/p110δ, another SZ risk gene, and reduced Akt activity in brains and B lymphocytes of SZ patients, suggesting a potentially affected downstream pathway (Law et al., 2012). Recently, a novel 6-kb haplotype block of 4 SNPs, located within intron 19 of the ERBB4 gene, has been associated with SZ in a Caucasian population (Agim et al., 2013).

Significant gene-gene interaction was observed between NRG1 and NRG2, NRG3, NRG6 or ERBB4, and also between NRG2 and EGFR (Benzel et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009; Nicodemus et al., 2010; So et al., 2010). Additionally, NRG and ERBB genes and activity could interact with other SZ susceptibility genes such as DISC1 and a7 ACHR (Mata et al., 2010; Mathew et al., 2007; Seshadri et al., 2010) or genes involved in Alzheimer's disease such as BACE1 (Marballi et al., 2012). Collectively, these findings underscore a likely contribution of the NRG-ERBB signaling at several levels to SZ etiology. It is plausible that these gene mutations may play complementary or synergistic roles in SZ pathogenesis.

Considering the many roles of NRG1 in neural development and synaptic plasticity, it is perhaps not surprising that NRG1 and ERBB4 genes have been implicated also in other brain disorders. NRG1 SNPs including those defining the original Icelandic haplotype are associated with bipolar disorders and major depressive disorder (Goes et al., 2009; Green et al., 2005; O'Donovan et al., 2008; Prata et al., 2009; Thomson et al., 2007; Walker et al., 2010). Likewise, NRG3 has been suggested as a candidate gene for ADHD (Sonuga-Barke et al., 2008) and Alzheimer disease (Wang et al., 2014), and rs6584400 confers genetic susceptibility to cognitive deficits in bipolar disorder (Meier et al., 2012). Whether NRG1 is associated with Alzheimer's disease is controversial (Go et al., 2005; Middle et al., 2010), perhaps awaiting better sub-phenotypes as readouts. Both NRG1 and NRG3 genes have been identified as susceptibility genes of Hirschsprung's disease, a congenital disorder characterized by absence of enteric ganglia in distal intestine (Garcia-Barcelo et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2013a), but whether this relates like other causes of this disease to Schwann cell functions in the neural crest lineage is unclear. A de novo reciprocal translocation t(2;6)(q34;p25.3) (with breakpoint between exons 1 and 2) in the ERBB4 gene was found in a patient with early myoclonic encephalopathy and profound psychomotor delay (Backx et al., 2009). There is no evidence yet for a link of NRG1 to autism although impaired hippocampal LTP and contextual fear memory deficits in mice modeling Angelman syndrome, a disorder related to the autism spectrum, can be reversed by ErbB inhibitors (Kaphzan et al., 2012). Recently, NRG3 and ERBB4 SNPs have been associated with nicotine dependence and with successful smoking cessation (Loukola et al., 2014; Turner et al., 2013). This is intriguing because smoking is more prevalent among schizophrenic patients than in the general population.

Pathophysiology of abnormal Nrg/ErbB signaling

While several genetic studies have suggested a link between the NRG/ERBB signaling network and brain disorders, the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying these disease connections are only starting to be explored in animal models. Both reduced and increased NRG or ERBB level and/or activity has been associated with SZ in postmortem studies of human brains (see above). In animal models, mice lacking one copy of the Nrg1, Erbb2, Erbb3, or Erbb4 gene exhibit various behavioral deficits including hyperactivity in open field and impairment in PPI, latent inhibition, reduced fear conditioning, reduced working memory, and/or abnormal social behavior (Boucher et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2008; Duffy et al., 2008; Ehrlichman et al., 2009; Gerlai et al., 2000; Karl et al., 2007; Moy et al., 2009; O'Tuathaigh et al., 2006; Rimer et al., 2005; Stefansson et al., 2002). Likewise, mice missing Nrg1 processing enzymes such as BACE1 or neuropsin showed relevant behavioral deficits (Savonenko et al., 2008; Tamura et al., 2012). Moreover, mutation of Erbb4 alone or together with Erbb2 leads to hyperactivity and impairment in PPI, fear conditioning, and learning/memory (Barros et al., 2009) (Chen et al., 2010b; Golub et al., 2004; Shamir et al., 2012; Stefansson et al., 2002). Noticeably, many of these deficits are observed in mutant mice in which Erbb4 has been specifically ablated in interneurons (Chen et al., 2010b; Del Pino et al., 2013; Shamir et al., 2012; Wen et al., 2010), suggesting that interneurons are the target of abnormal Nrg1 signaling.

In terms of increased Nrg1 signaling, transgenic mice overexpressing neuronal Nrg1 Type I exhibited hyperactivity, reduced PPI, impaired working memory, contextual fear conditioning and social interaction (Deakin et al., 2009; Deakin et al., 2012; Kato et al., 2010; Luo et al., 2013; Yin et al., 2013a). Importantly, switching off Nrg1 expression in pyramidal neurons of adult mice diminishes behavioral deficits and synaptic dysfunction (Luo et al., 2013; Yin et al., 2013a). This provides compelling evidence that high levels of Nrg1 are pathogenic and suggests that effects of abnormal development can be overcome. Conversely, increase of Nrg1 in adult mice appears to be sufficient to impair glutamatergic transmission and behavior (Yin et al., 2013a; Agarwal et al., 2014). These observations suggest that overexpression-induced deficits require continuous Nrg1 abnormality in adulthood and that schizophrenia patients might benefit from a therapeutic adjustment of NRG1 signaling.

Theoretically, there are two different pathophysiological consequences of NRG1/ERBB4 loss of function mutations. The mutation may lead to a loss or reduction of physiological NRG1/ERBB4 functions in neural development and synaptic transmission. Alternatively (or in addition), the loss of function may results in a homeostatic compensatory effect that by itself perturbs normal brain functions. For example, lack of Erbb4 in PV+ interneurons impairs the assembly and function of GABAergic circuitry and as a result, excitatory neurons in the circuitry down-regulate synapse number or function (Cooper and Koleske, 2011; Del Pino et al., 2013; Yin et al., 2013b). However, effects of Erbb4 mutations on interneuron firing are inconsistent in the literature. Firing of interneurons was reportedly increased in the hippocampus of Lhx6-Cre;Erbb4-/- mice, but reduced in mPFC of Dlx6-Cre;Erbb4-/- mice (Del Pino et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2013). This discrepancy may result from differences in brain regions, Cre lines used, or recording conditions (such as ramp stimulation intensity) and warrants further studies. Nevertheless, Erbb4 deletion in interneurons alters cortical excitability and oscillatory activity and disrupts synchrony across cortical regions (Del Pino et al., 2013; Fazzari et al., 2010; Wen et al., 2010).

Elevated levels or activity of NRG1 or ERBB4 may augment the physiological function of NRG1 signaling. On the other hand, perhaps in addition, high levels of NRG1 or ERBB4 may be pathogenic via distinct, unrelated mechanisms, some of which could be cell autonomous. For example, elevated Erbb4 levels increase the spine density in neonatal, organotypic hippocampal slices (Li et al., 2007). LIM kinase 1 (Limk1) is recruited into synaptosomes following overexpression of Nrg1 (Yin et al., 2013a). LIMK1 is among the 25 genes deleted in Williams syndrome (Tassabehji et al., 1996), and the gene is duplicated in some patients with autism (Sanders et al., 2011) or SZ (Kirov et al., 2012). Subcutaneous injection of Nrg1 into neonatal mice decreases latent inhibition and PPI by promoting dopaminergic function (Kato et al., 2011) and chronic treatment with Nrg1 impairs long-term depression of hippocampal inhibitory synapses by reducing 2-arachidonoylglycerol, a major endocannabinoid (Du et al., 2013). Upon activation, Erbb4 recruits and activates PI3 kinase (Figure 1). PI3KCD/p110δ, a catalytic subunit of PI3 kinase, is increased in the brain of SZ patients (Law et al., 2012); and inhibition of p110δ increases Akt activity, attenuates behavioral effects of amphetamine, and reverses PPI deficits in SZ animal models. Likewise, truncation Erbb4 mutants may have dominant negative effects, in addition to loss of function (Chen et al., 2003; Roy et al., 2007).

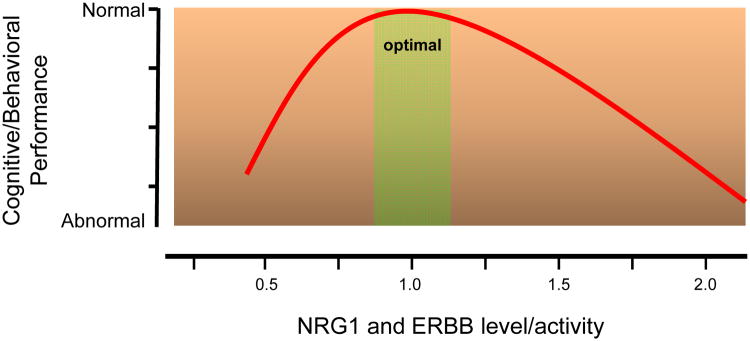

Evidently, both Nrg1 heterogyzous mouse mutants and transgenic overexpressors exhibit synaptic dysfunctions and behavioral deficits. This suggests a model in which there is an “optimal” range for NRG1/ERBB signaling in the brain (Bjarnadottir et al., 2007; Tamura et al., 2012). Thus, the level and activity of NRG1 isoforms, ERBB kinases and partners must be tightly regulated to maintain normal synaptic function and behavior (Figure 8) (Marin and Rico, 2013; Role and Talmage, 2007). According to this model, either too much or too little NRG1/ERRB signaling is sufficient to impair neural development and synaptic plasticity, and may lead to hypofunction of glutamatergic or GABAergic pathways, both of which being implicated in schizophrenia (Lewis and Moghaddam, 2006; Tsai and Coyle, 2002).

Figure 8. Inverted U-curve illustrating the relationship between NRG1/ERBB level and activity and cognitive/behavioral performance.

Y axis shows cognitive/behavioral performance; darker color indicates poorer performance. X axis shows NRG1 and ERBB level and activity with 1 as normal. Green shade indicates the optimal range.

Conclusion

The NRG-ERBB signaling in the brain is highly unusual because a small group of ligands (NRG1-6) and receptor genes (ERBB2-4) creates a vastly complex network of signaling proteins with multiple expression domains and divergent functions in the developing and adult nervous system. Not surprisingly, genetic association studies are providing growing evidence that NRG and ERBB genes are associated with complex brain disorders, such as SZ, bipolar disorder, and depression. Phenotype-based association studies (PGAS) are revealing biological functions of NRGs and ERBBs and pathophysiological mechanisms associated with mutations. Moreover, in vivo mouse studies indicate that the Nrg-Erbb network plays a critical role in circuit assembly, peripheral myelination and homeostasis of CNS synaptic functions. Mouse models that mimick either increased or decreased levels of NRG1 (or ERBB4) in development exhibit relevant behavioral deficits, suggesting altered signaling intensity as a pathophysiological mechanism.

While NRG1/ERBB signaling in axon-glia interaction and myelination appears straight-forward, the role of these genes in neuronal communiction raises new questions. First,despite the association of SNPs in NRG1 and ERBB4 with several brain disorders, evidence is tangential that they are “causal” and little is known about how these SNPs alter the expression of NRGs and ERBBs in SZ patients. It is also unclear how they interact with other SZ risk factors. Second, almost all pro-Nrgs isoforms are transmembrane proteins and, following a complex proteolytic cleavage, release soluble Nrgs. This processing is not well understood yet, but Nrg production is thought to be coregulated by neuronal activity. An answer to this question would also contribute to a better understanding of cell-adhesion-like of NRGs and ERBBs. Third, interneuron abnormality is thought to cause cognitive deficits in SZ patients. Intriguingly, there is evidence that in the cortex, ERBB4 is expressed specifically in interneurons and perhaps is the only receptor tyrosine kinase with interneuron expression preference. In particular, ERBB4 is expressed in PV+ cells that control the output of projection neurons. Moreover, SNPs and mRNA of ERBB4 are associated with GABA levels or interneuron deficits. Indeed, cognitive function is impaired in mutant mice that lack Erbb4 in PV+ cells. These observations suggest ERBB4 as an important target of abnormal NRG signaling. In addition to PV+ cells, Erbb4 is also detected in other interneurons. Whether their function is regulated by Nrg signaling remains unknown. Is ERBB4 a marker of a new group of interneurons that are vulnerable in SZ pathology? Future studies will be warranted to understand the function of these Erbb4+ interneurons and their circuitry. Finally, SZ-relevant behavioral deficits in mice that overexpress Nrg1 could be ameliorated by reducing Nrg1 levels. This suggests that patients with relevant symptoms may benefit from therapeutic intervention aimed at restoring NRG1 signaling to the optimal level. Being strategically expressed in interneurons, ERBB4 may serve as an ideal target for drug development. Such drugs could specifically renovate GABAergic activity with fewer side effects.

Acknowledgments