Abstract

Background:

The larger size of the currently available transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) probes limits their use to relatively older infants undergoing cardiac surgery. In very young neonates and infants, epicardial echocardiogram is used to assess postoperative residual defects. Recently, a miniaturized microTEE probe compatible in neonates has been introduced for clinical use. We evaluated the use of this probe in small infants undergoing cardiac surgery.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty-three consecutive neonates and infants undergoing cardiac surgery at our institution were included in the study. Intraoperative echocardiography with Philips s8-3t microTEE probe done using IE33 platform was utilized to study the preoperative anatomy and assess postoperative results.

Results:

Thirty-three patients aged 3 days-2 years (mean 5.1 months) and weighing 2.5-11 kg (mean 4.4 kg) underwent perioperative evaluation using the microTEE probe. Good quality two-dimensional and color Doppler images were obtained in all patients. There were no complications related to the probe insertion or manipulation. The findings on microTEE led to revision of surgery in five patients. Certain echocardiographic parameters that could never be recorded with epicardial echocardiogram could be easily seen in microTEE.

Conclusion:

On preliminary evaluation, the microTEE probe provided good quality images in very small infants who were not amenable for transesophageal echocardiographic evaluation so far. The probe could be used safely in small infants without complications. It appears to be a promising imaging modality in the perioperative assessment of young infants undergoing cardiac surgery, in whom intraoperative epicardial echocardiography is currently the only tool.

Keywords: Cardiac surgery, echocardiography, micro-transesophageal probe, young infant

INTRODUCTION

Increasing health-care facilities and improved diagnostic modalities including fetal echocardiography have allowed detection of critical congenital heart diseases very early in the neonatal period and in early infancy. Congenital heart diseases that present early usually require immediate or early intervention. As a result, more and more neonates and young infants undergo complex open-heart surgery in the current era.

Complex neonatal and infant surgeries are associated with increased surgical morbidity. Suboptimal surgical repair translates directly to increased morbidity and mortality in the postoperative period. The impact of residual defects on the surgical outcome is more appreciated in neonates and small infants in whom residual lesions are tolerated poorly. The use of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) has been well documented to improve the outcomes of open-heart surgery.[1] The pediatric transesophageal probes available at present permits their use only in patients weighing more than 5 kg and very rarely has been successfully used in weights as low as 3.5 kg. Complications directly related to TEE have been reported mainly in smaller children.[2] As a result, many infants and neonates have been undergoing open-heart surgery either without any echocardiographic guidance or with the help of epicardial echocardiography which interrupts surgery and disturbs the surgical field. Hence, the prospect of intraoperative TEE remains attractive in this subgroup of patients. Technological advances have allowed the development of a miniaturized microTEE probe for use in neonates and young infants. This probe can be inserted in all babies weighing at least 2.5 kg. We report our initial experience with this probe in neonates and young infants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Population

All consecutive neonates and infants undergoing cardiac surgery at our tertiary care institution from November 2013 to February 2014 were included in the study. The indications for TEE were decided by the cardiothoracic surgeon and the cardiologist involved in the care of the patient. Exclusion criteria included standard contraindications to TEE including esophageal obstruction and tracheoesophageal fistula. None of the patients in our cohort were excluded. Informed written consent was obtained for the intraoperative use of the microTEE probe from the parents before the study. The procedure was performed in accordance with the Helsinki declaration and hospital ethical committee permitted use of this probe. Patients with weight below 7 kg were included in this study, as the regular pediatric transesophageal echocardiographic probe could be used in the patients weighing more than 7 kg.

The TEE probe

The S8-3t microTEE transducer is roughly one third the size of previous pediatric TEE transducers. The miniaturized multiplane microTEE probe (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA) has a shaft width of 5.2 mm, a transducer tip width of 7.5 mm, and a height of 5.5 mm. In comparison, the commonly used pediatric TEE probe has dimensions of 7.5 mm, 10.6 mm, and 8 mm, respectively. The microTEE transducer is a 32-element phased array transducer that is equipped with two-dimensional B mode echocardiography, color Doppler, pulse wave and continuous-wave Doppler, M-mode, and color flow M-mode features. It has a center frequency of 6 MHz on a bandwidth of 3.2-7.4 MHz. There is a 180° manual image plane control with angular display, anterior and posterior articulation, and an articulation brake. The transducer has tip temperature sensing and display for added safety.

Patient safety monitoring

After the induction of general anesthesia, the hemodynamic and ventilator parameters were recorded. The hemodynamic parameters noted were heart rate, systolic, diastolic, and mean systemic arterial pressures. Ventilatory parameters recorded included mean airway pressure and tidal volume. The senior anesthetist performed probe insertion and withdrawal. The depth of insertion was decided by visualization of the intracardiac structures. Hemodynamic and ventilator parameters were closely monitored during the probe insertion and also throughout the period when the probe was present in the patient's esophagus. After completing the TEE, all the hemodynamic and ventilator parameters were charted before and after removal of the probe.

Echocardiographic assessment

Senior cardiologists performed the preoperative and postoperative TEE assessments. The accuracy of the findings on TEE were confirmed by comparing with the surgical findings and or by a transthoracic echocardiogram performed later in the intensive care unit. All anatomical, hemodynamic parameters were recorded to assess the adequacy of surgery, presence of residual defects. Importance was paid to analysis of details of the atrioventricular and semilunar valves, regarding the structure of the annulus and leaflets, their support apparatus, and function. Similarly, importance was given to assessment of very small structures like left and right coronary arteries, their flow patterns. If any structure is not visible on microTEE, surgeon and cardiologist were prepared in all the patients to resort to epicardial echocardiogram to study the intracardiac anatomy.

RESULTS

Thirty-three patients underwent open-heart surgery with the guidance of intraoperative TEE using the microTEE probe in the study period. The median weight was 4.3 kg (range 2.5-11 kg) and the median age was 3 months (range 3 days-2 years). The microTEE probe insertion was simple and successful in all the intubated patients. The probe provided good quality two-dimensional, color Doppler, and spectral Doppler images in all the patients. There were no complications in any of the studied patients, which could be related to the microTEE probe. All the manipulations of the probe including insertion, flexion, and removal were well tolerated. None of the patients required premature withdrawal of the probe during the surgery. None of the patients had inadequate images to warrant utilization of epicardial echocardiography.

The patient characteristics and microTEE findings are summarized in Table 1. Among the eight patients who had undergone surgical closure of ventricular septal defects, anatomy, and flow through the defects were well demonstrated on microTEE. [Figures 1 and 2, Video 1 Patient No 11] Among the six babies who had undergone arterial switch operation, both the outflows including the site of anastomosis were imaged well by the microTEE. [Figure 3 and Video 2 Patient No 3] Both the left and right coronary arteries with their color flows could be delineated well after coronary artery transfer in these patients. [Figure 4 and Video 3 Patient No 27] We had never demonstrated coronary flows after coronary transfer in epicardial echocardiography in the past as the probe could never be placed well over the neoaortic root or neopulmonary root. One delayed presenter of transposition of great arteries with regressed left ventricle had severe postoperative left ventricular systolic dysfunction. [Video 4 Patient No 27] In this patient, demonstration of normal coronary flows enabled us to pinpoint the cause of severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction to afterload mismatch.

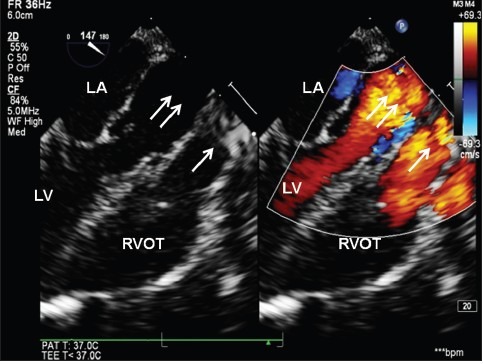

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and results

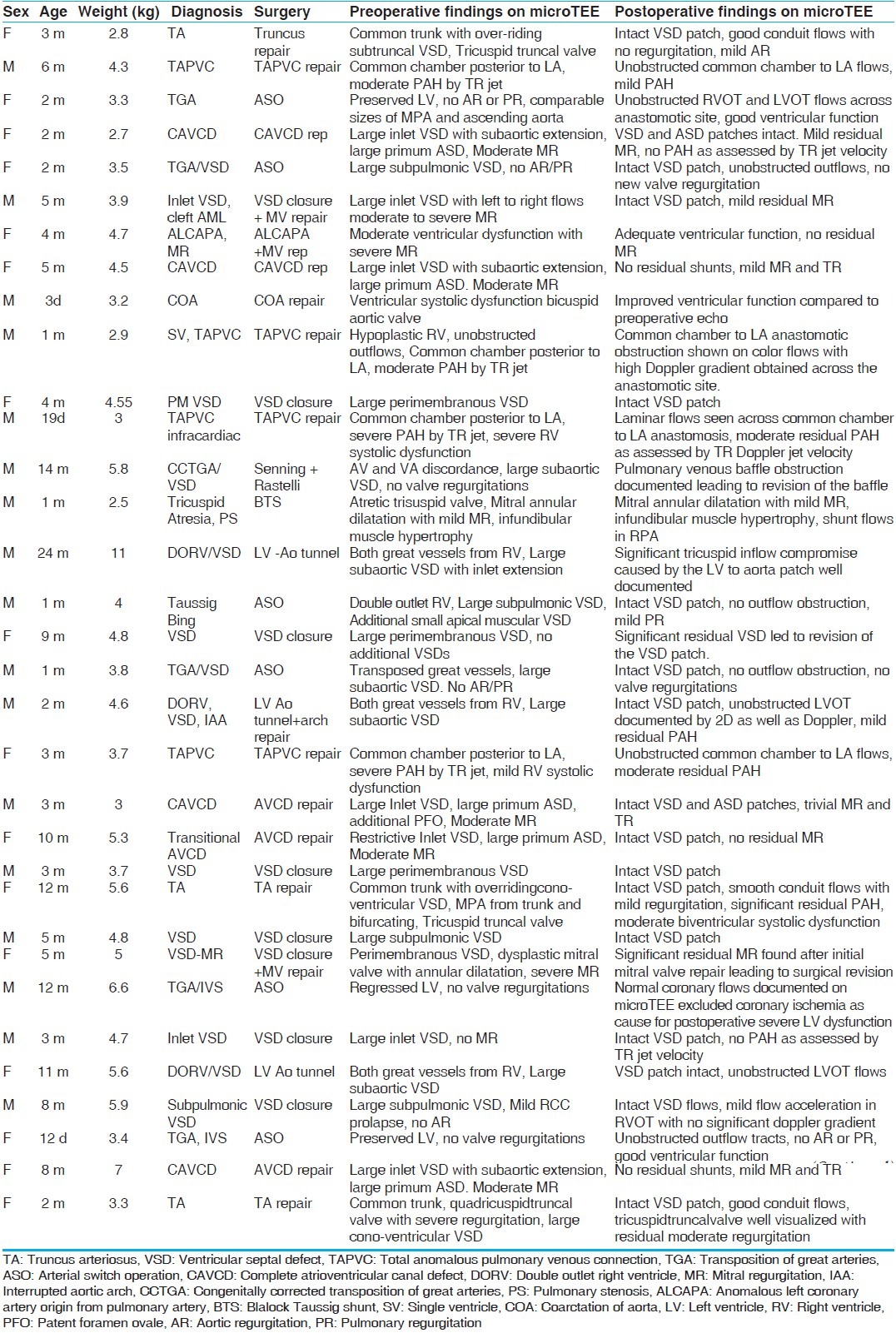

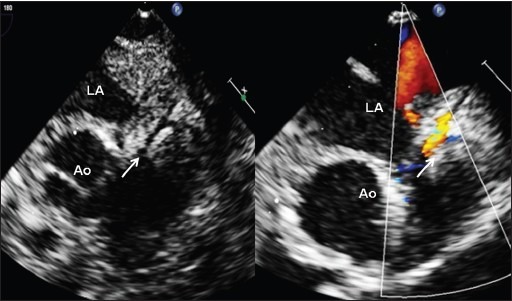

Figure 1.

Large perimembranous ventricular septal defect (VSD) (Video 1) measuring 8 mm shown by arrow and unobstructed right ventricular outflow in an infant weighing 4.8 kg. Note the high frame rates obtained by the microTEE probe RA: Right atrium, LA: Left atrium, RVOT: Right ventricular outflow tract

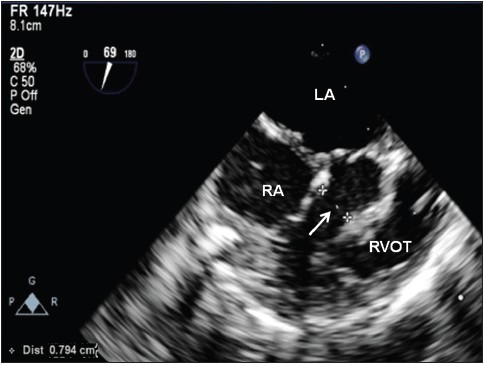

Figure 2.

Continuous wave Doppler across a residual VSD indicating interventricular gradient of 36 mmHg. Unlike epicardial echocardiography using a neonatal transthoracic probe with a higher frequency (5-12 MHz), the lower frequency of microTEE probe (4 MHz) permits accurate Doppler evaluation

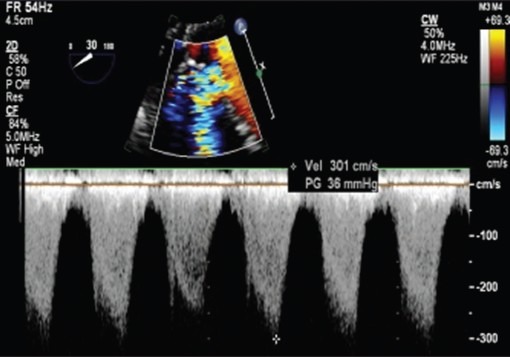

Figure 3.

Two-dimensional and color dopplerlong axis views (Video 2) demonstrating unobstructed left (double arrow) and right ventricular outflow (single) tracts after arterial switch operation ind-transposition of great arteries. LA-left atrium, LV-left ventricle, RVOT-right ventricular outflow tract

Figure 4.

Left coronary artery (arrow) with flows documented (Video 3) after arterial switch operation for d-transposition of great arteries. Significant postoperative left ventricular dysfunction with moderate mitral regurgitation (Video 4) was caused by afterload mismatch and coronary ischemia was excluded

None of the four infants who had undergone repair of atrioventricular canal defect, had residual lesions, significant enough to warrant revision. Two patients had successful mitral valve repair. Among the three babies with Truncus arteriosus, truncal valve repair including one conversion of a quadricuspid valve to tricuspid valve could be assessed well. Out of the three babies with double outlet right ventricle and ventricular septal defect, one patient had the presence of tricuspid valve tissue in the path of the prospective left ventricle to aorta pathway, which was well imaged by microTEE. The surgical findings confirmed the echocardiographic impressions. In this patient, even though a biventricular repair was attempted, the patch led to significant compromise of the tricuspid valve inflow which was well demonstrated by microTEE. Four babies had undergone surgical repair of total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage, anastamotic obstruction in one patient demonstrated by TEE was surgically revised. [Figure 5 and Video 5 Patient No 10] In a 14-month-old baby with corrected transposition of great arteries, large routable sub-aortic cono-ventricular ventricular septal defect, and severe pulmonary stenosis weighing 5.8 kg, a decision was taken to perform a biventricular anatomical repair. During the surgery that incorporated Senning surgery with Rastelli operation, the presence of significant posterior pulmonary venous baffle obstruction was identified on postoperative microTEE imaging.

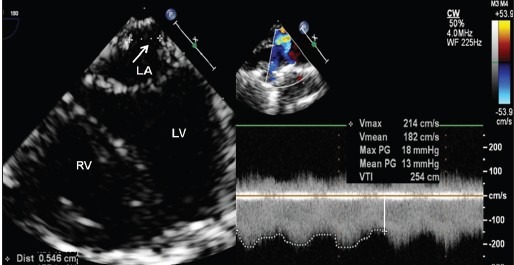

Figure 5.

Pulmonary venous anastomotic obstruction after surgical repair of total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage, seen on four chamber view (Video 5) in a 1-month-old baby weighing 2.9 kg. Doppler interrogation showed significant gradients of 13 mmHg across the obstruction

Surgical correlation and revisions

The findings on the preoperative microTEE directly correlated with surgical findings. The postoperative microTEE findings led to revision of surgery on a second run of cardiopulmonary bypass in five patients. These included common chamber to left atrium anastomotic obstruction after repair of total anomalous pulmonary venous connection, tricuspid inflow tract obstruction after left ventricle to aorta tunneling in a double outlet right ventricle with a large inlet ventricular septal defect, pulmonary venous baffle obstruction after Senning procedure, residual significant mitral valve regurgitation after mitral valve repair, and residual ventricular septal defect. The postsurgical findings correlated with transthoracic echocardiography findings done subsequently in the intensive care unit in the postoperative period.

DISCUSSION

Need for imaging in neonates

The use of TEE has become a standard practice for evaluation of surgical repair after open-heart surgery. The mean age and weight of patients being operated for congenital heart diseases are declining in the recent decade due to early diagnosis, improvements in surgical and anesthesia techniques and advances in intensive care facilities. More and more neonates and young infants undergo complex open-heart surgeries in the current era than in the past. This necessitates the use of newer imaging modalities that can be safely used in this subgroup of patients. Intraoperative evaluation of young infants weighing less than 4-5 kg has not been possible in the past due to the large size of the currently available pediatric TEE probes which makes it technically difficult to be inserted in small infants. There have been reports of inability to insert the probe, hemodynamic instability or airway compromise with the use of these relatively large size probes in small children.[2] The use of a small-sized microTEE probe may prove extremely useful in the intraoperative evaluation of infants and young very infants. Such an assessment of the surgical repair after weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass may prevent emergency reoperations, thereby reducing the morbidity and mortality and decreasing the cost of surgery.[3,4]

Safety of miniaturized probes

Increasing number of neonatal surgeries made various investigators to explore different options of use of miniaturized TEE probes in literature. The effect of miniaturized TEE probe insertion on hemodynamic variables were studied in 23 patients weighing 2-5 kg with a biplane pediatric TEE probe.[5] The study concluded that hemodynamic compromise is infrequent in small infants undergoing TEE with smaller biplane probe. While biplane probes permitted miniaturization, challenges are posed in minimizing size of multi-plane probes. In another study with 42 patients that included older patients (maximum of 6 years), microTEE probe gave excellent image quality in most patients.[6] They noted poor quality images in patients weighing more than 20 kg due to lack of contact of the TEE probe with the anterior wall of the esophagus. Bruce and colleagues[7] described the use of a miniaturized 5.5-10 MHz, phased-array, single longitudinal plane transducer mounted on a 3.3-mm diameter catheter for TEE in very small infants. This probe was placed successfully in 22 patients weighing less than 6 kg including 4 infants weighing less than 2.5 kg, and there were no cases of hemodynamic compromise or increasing airway resistance. This was the smallest probe that was proved feasible in infants weighing less than 2.5 kg inspite of its limitations of imaging in single longitudinal plane and lacking tip temperature sensing. Sinai et al. has recently reported excellent imaging with the microTEE probe in infants weighing less than 5 kg.[8] Kuberan et al. compared the images obtained by a microTEE probe with that of standard pediatric and adult probes. They found that microTEE probe images were excellent in patients weighing less than 10 kg. In older patients, standard pediatric TEE probes provided better images.[9] Some of these probes were withdrawn by the manufacturer later due to probe tip warming or spillage of oil from the miniaturized rotor within the probe. The current probe used in this study incorporates recent modifications to avoid the above mentioned complications from the probe.

Epicardial echo — Limitations

The alternative imaging option available currently is use of intraoperative epicardial echocardiography. Since there are no customized probes for this purpose, most centers resort to using the neonatal probe with bandwidth of 5-12 MHz with median operative frequency of 8 MHz for direct placement over the surface of the right ventricle. Any breach of the long sterile insulating sleeve might result in spill of the echocardiographic conducting jelly over the operative field and it could also affect the sterility of the operative room. Pressure of the probe over the surface of the right ventricle might cause hemodynamic compromise. Similar pressure could also alter the flows across the complex intraventricular tunnels after surgical repair of double outlet right ventricle and other defects. Posterior anastomosis like Senning pulmonary venous baffle and surgical anastomosis after repair of total anomalous pulmonary venous return were sometimes not very well visualized. Color Doppler and spectral Doppler imaging were suboptimal in the high frequency neonatal probes, but better with a pediatric probe (bandwidth of 3-8 MHz). So, switching between probes may be needed between neonatal probe for B mode resolution and pediatric probe for Doppler evaluation. Certain fine anatomic findings as coronary flows after arterial switch operations, morphology of the repaired truncal valve were never feasible with epicardial echocardiography consistently since pressure over the neoaortic root often compromised the hemodynamics and artificially induced aortic regurgitation.

Current role of epicardial echocardiography

However, epicardial echocardiography is widely used effectively in many centers around the world currently. It does not involve any costs since those probes are available in any pediatric cardiac center. This study was not designed to compare the superiority of imaging between the two modalities in the utility of post-operative assessment of the residual defects after neonatal heart surgery.

Limitations of the study

We have tried to evaluate the microTEE probe mostly in young infants with smaller weights. Our youngest patient weighed 2.5 kg, which is the recommended lower weight cut off by the manufacturer. We did not use in any patients under 2.5 kg in this study period. We have not tried the probe in bigger children for whom use of the regular pediatric TEE probe has been shown to give better quality images.

CONCLUSION

In our preliminary use of the new generation multiplane microTEE probe in the perioperative assessment of neonates and infants undergoing complex cardiac surgery, the probe was safe and provided good quality images of even smaller structures like coronary arteries. With certain limitations of epicardial echocardiography like compromise of operative field, sterility of the surgery, cumbersome change of probes, microTEE is an attractive new alternative imaging tool in young infant cardiac surgery.

Video available on www.annalspc.com

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Randolph GR, Hagler DJ, Connolly HM, Dearani JA, Puga FJ, Danielstin GK, et al. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography during surgery for congenital heart defects. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;124:1176–82. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.125816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stevenson JG. Incidence of complications in pediatric transesophageal echocardiography: Experience in 1650 cases. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1999;12:527e32. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(99)70090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bettex DA, Pretre R, Jenni R, Schmid ER. Cost-effectiveness of routine intraoperative transesophageal echocardiographyin pediatric cardiac surgery: A 10-year experience. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:1271–5. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000149594.81543.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ungerleider RM, Kisslo JA, Greeley WJ, Li JS, Kanter RJ, Kern FH, et al. Intraoperative echocardiography during congenital heart operations: Experience from 1,000 cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:S539–42. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00853-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andropoulos DB, Stayer SA, Bent ST, Campos CJ, Fraser CD. The effects of transesophageal echocardiography on hemodynamic variables in small infants undergoing cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2000;14:133–5. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(00)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scohy TV, Gommers D, Jan ten Harkel AD, Deryck Y, McGhie J, Bogers AJ. Intraoperative evaluation of micro multiplane transesophageal echocardiographic probe in surgery for congenital heart disease. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2007;8:241–6. doi: 10.1016/j.euje.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruce CJ, O’Leary P, Hagler DJ, Seward JB, Cabalka AK. Miniaturized transesophageal echocardiography in newborn infants. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:791–7. doi: 10.1067/mje.2002.120978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinai CZ, Girish SS, Geoffrey AF, Tain-Yen H, Scott MB, Andrew MA, et al. Initial experience with a miniaturized multiplane transesophageal probe in small infants undergoing cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:1990–4. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.01.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pushparajah K, Miller OI, Rawlins D, Barlow A, Nugent K, Simpson JS. Clinical application of a micro multiplane transoesophageal probe in congenital cardiac disease. Cardiol Young. 2011;22:170–7. doi: 10.1017/S1047951111000977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.