Abstract

This paper presents a microfluidic device enabling culture of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) where extracellular matrix coating, VSMC seeding, culture, and immunostaining are demonstrated in a tubing-free manner. By optimizing droplet volume differences between inlets and outlets of micro channels, VSMCs were evenly seeded into microfluidic devices. Furthermore, the effects of extracellular matrix (e.g., collagen, poly-l-Lysine (PLL), and fibronectin) on VSMC proliferation and phenotype expression were explored. As a platform technology, this microfluidic device may function as a new VSMC culture model enabling VSMC studies.

I. INTRODUCTION

Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) are essential blood vessel components responsible for the regulation of vessel tones and their dysfunctions may lead to diverse vascular diseases1,2 (e.g., abdominal aortic aneurysm,3,4 atherosclerosis,5–7 and restenosis8,9). Current studies of VSMCs are based on conventional cell culture approaches (e.g., culture dish and flask),10,11 which allow no control over the spatial/temporal distribution of the cells and biomolecules and thus cannot recapitulate local in vivo microenvironments.

Microfluidics is the science and technology of manipulating and detecting fluids in the microscale.12,13 Due to its dimensional comparison with biological cells and capabilities of defining local biophysical, biochemical, and physiological cues, microfluidics has been used to construct more in vivo like cell culture models,14–16 enabling tumor,17,18 neuron,19 and vascular20,21 studies.

As to applications of microfluidics to vascular smooth muscle cell studies, preliminary studies were confined within three areas.22–43 As the first demonstration, soft lithography was used to form micro and nano patterned extracellular matrix proteins and geometrical topographies enabling the regulation of VSMC morphologies and phenotypes.22,23,27–31,36,37,39 Furthermore, microfluidics based gradient-compliance substrates were proposed to investigate durotaxis (migration from less stiff to more stiff substrates) of VSMCs.26,35 Meanwhile, three-dimensional culture of VSMCs based on layer-by-layer assemblies32,38 or circular micro channels42 were demonstrated for tissue engineering studies. However, the combination of microfluidics with vascular smooth muscle cells is still at an early stage and no systematic studies of on-chip VSMC culture were previously demonstrated.

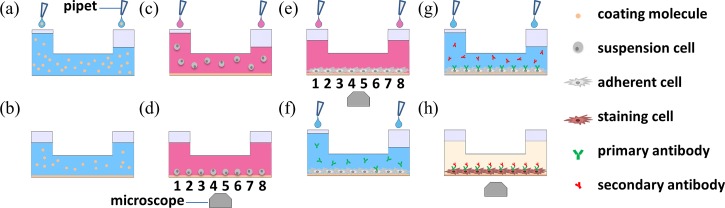

To address this issue, this paper proposed a microfluidic platform for VSMC culture where extracellular matrix coating (Figures 1(a) and 1(b)), VSMC seeding, culture and observation (Figures 1(c)–1(e)), and immunostaining (Figures 1(f)–1(h)) are demonstrated in a tubing-free manner. More specifically, the VSMC seeding evenness in microfluidic channels was investigated and the effects of extracellular matrix on VSMC phenotypes were explored. In addition, as gravity was used as the driving force for cell loading and immunostaining, this platform does not need external pumps and tubes, which can be operated in biological labs with low access requirements.

FIG. 1.

Schematic of the tubing-free microfluidic platform for vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) culture where gravity was used for extracellular matrix coating ((a) and (b)), VSMC seeding, culture and observation ((c)-(e)), and immunostaining ((f)-(h)).

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A. Materials

Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) was purchased from Hyclon and the other cell-culture reagents were purchased from Life Technologies. SU-8 photoresist (MicroChem) was used for mold master fabrication while collagen (Sigma), poly-l-Lysine (PLL) (Sigma), and fibronectin (Sigma) were used for glass surface coating. Materials for alpha actin immunostaining included 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma), primary antibody (Bioss), GTVision Detection System (Gene Technology), and goat serum (GIBCO).

B. Device design and fabrication

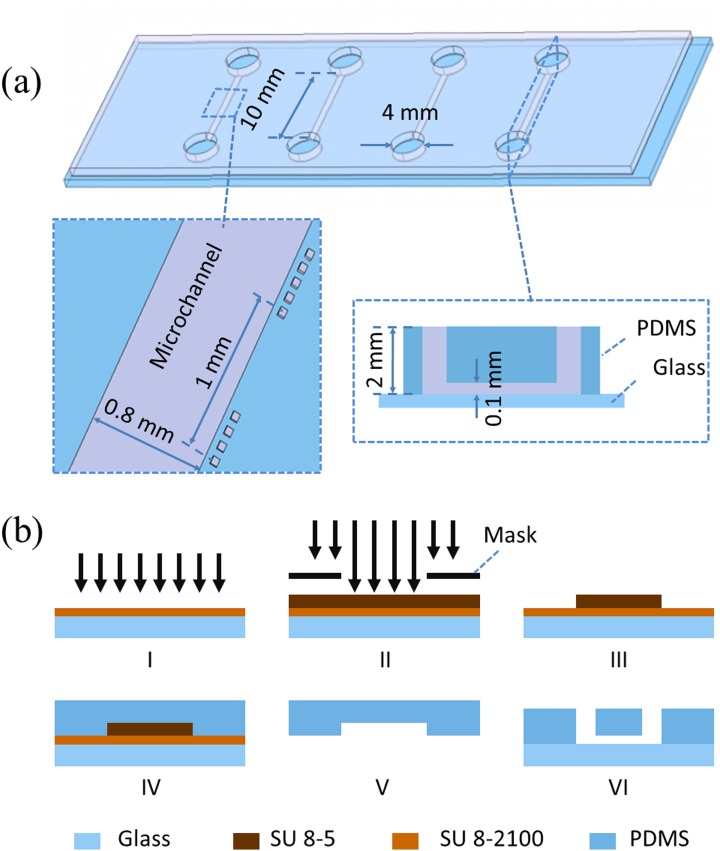

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) based microchannels with channel dimensions of 10.00 L × 0.80 W × 0.10 H (mm) were proposed in this study, where each channel was divided into eight observation windows (1.00 L × 0.80 W × 0.10 H (mm)) and labeled as 1 to 8 for cell distribution eveness evaluation. Two microchannel ports (channel inlet and outlet) with a diameter of 4 mm and a PDMS thickness of 2 mm were used in this study to facilitate liquid droplet manipulation. Four channels were included in one mask to characterize operation repeatability (see Figure 2(a)).

FIG. 2.

(a) Dimensions of microfluidic devices for VSMC culture (channel length: 10 mm, channel width: 0.8 mm, channel height: 0.1 mm, port diameter: 4 mm, PDMS thickness: 2 mm). (b) Microfluidic device fabrication flow chart including SU-8 5 based adhesive layer fabrication (I), channel mold master fabrication using SU-8 2100 (II, III), PDMS channel structure formation (IV, V), and PDMS-glass bonding (VI).

The PDMS device was replicated from a single-layer SU-8 mold based on the conventional soft lithography (see Figure 2(b)). Briefly, SU-8 5 was spin coated on a glass slide, flood exposed, post exposure baked, and hard baked (without development) to form an adhesive layer, followed by SU-8 2100 spin coating, exposure and development, forming the mold master with a height of 100 μm. PDMS prepolymers and curing agents were mixed, degassed, poured on channel masters, and baked in an oven. Cured PDMS channels were then peeled from the SU-8 masters with ports punched through and bonded to glass slides.

C. Cell culture

VSMCs of CRL-1999 (ATCC) were cultured with DMEM media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. Immediately prior to an experiment, cells were trypsinized, centrifuged, and resuspended in supplemented culture medium with a concentration of 1 × 106 cells per ml. Cell passage generations between p6 and P12 were used in the experiments.

D. Device operation and data analysis

The fabricated microfluidic devices were sterilized in a hood under ultraviolet (UV) overnight, followed by surface coating (PLL of 0.1 mg per ml, or fibronectin of 0.1 mg per ml or collagen of 1 mg per ml). As the first step, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solutions were flushed into the microfluidic devices by using micro pipets. Then, PBS solutions in two ports were replaced with coating solutions containing PLL, fibronectin, or collagen at a volume of 20 μl and 15 μl, respectively. Due to the gravity difference, the coating solutions were loaded into microfluidic channels for one-hour channel soaking. In the end, the coating solutions were removed by aspiration and the coated surfaces were rinsed with DMEM thoroughly.

The cell loading and observation protocol is as follows. DMEM solutions in two ports were removed and replaced with cell suspension solutions at 20 vs. 18 μl, 20 vs. 15 μl, 20 vs. 10 μl or 20 vs. 0 μl, respectively (1 × 106 cells per ml). After five minutes of cell loading, microscopic images were taken to evaluate the cellular seeding evenness. Then each microfluidic device was placed in a petri dish containing PBS to limit evaporation and osmolality shifts and then incubated in a cell incubator. DMEM was replaced every 12 h where solutions in two ports were removed and replaced with 20 μl fresh culture medium.

The on-chip immunostaining procedure is as follows. Cells within microfluidic devices were washed twice with PBS, fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde (15 min), permeabilized by 0.3% Triton X-100 (15 min), blocked with 10% goat serum (1 h). Then cells within microfluidic devices were incubated with primary antibodies (1:100) at 37 °C (1 h), secondary antibodies at 37 °C (1 h), and the Diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution (2 min), sequentially. Note that in all the steps requiring liquid handling, a setup of 20 vs. 10 μl was used where gravity was the driving force for liquid manipulation inside microfluidic devices.

In order to evaluate the cell loading evenness and the cellular proliferation status inside microfluidic channels, cell number analysis was conducted based on manual processing of phase-contrast images taken along the length of the micro channels at 0 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h (×10 magnification and 592 images in total).

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Microfluidic technologies hold great promise for the creation of advanced cell culture models.14–16 However, the majority of currently available microfluidic cell culture approaches are not compatible with existing laboratories since syringe pumps and plastic tubes are used for cell loading and liquid dispersion. In addition, these physical connections with microfluidic devices lead to cell seeding on tubing walls and medium instabilities due to tubing disturbances.44,45

To address this issue, Beebe et al.44–46 and Takayama et al.47–49 proposed the concept of tubing-free microfluidic cell culture where surface tension or gravity was used for cell loading and liquid manipulation. Based on surface tension, difference in menisci of unequal volumes of two drops is used to drive liquid flow, which was extensively optimized and demonstrated for cellular micro environment reconstructions.44–46 Meanwhile, although gravity based cell loading (relying on the height rather than menisci difference of drops for the channel inlet and outlet) was utilized for cell loading and characterization,47–49 corresponding operation optimization and condition investigation were not reported.

A. Cell loading distribution evaluation in microfluidic channels

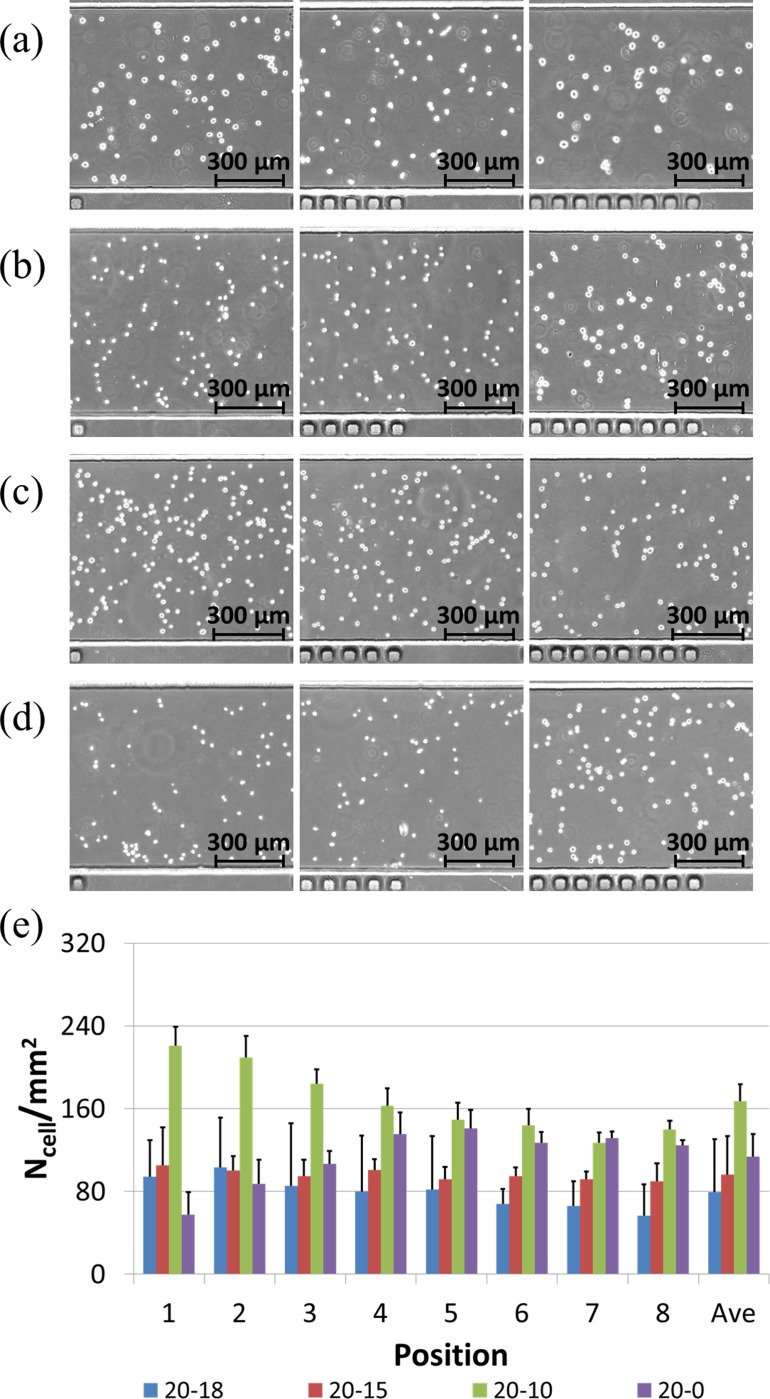

Figure 3 shows the effects of liquid volume differences (different gravity levels) between two ports on the cell distribution evenness within microfluidic channels. For the microfluidic channels with a total volume of ∼1 μl and a cell loading concentration of 1 million cells per ml, solutions within two ports were replaced with 20 vs. 18 μl, 20 vs. 15 μl, 20 vs. 10 μl, or 20 vs. 0 μl, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Microscopic pictures of seeded VSMCs at positions of 1, 5, and 8 (left to right) for 20 vs. 18 μl (a), 20 vs. 15 μl (b), 20 vs. 10 μl (c), and 20 vs. 0 μl (d), respectively, with quantified cell numbers (e). These results suggest an optimal choice of the 20 vs. 15 μl setup for even cell distribution.

Cell loading densities based on the setup of 20 vs. 18 μl were quantified as 94.2 ± 21.7/mm2 (position 1), 103.3 ± 23.6/mm2 (position 2), 85.4 ± 12.6/mm2 (position 3), 79.6 ± 20.7/mm2 (position 4), 81.7 ± 17.8/mm2 (position 5), 67.9 ± 10.4/mm2 (position 6), 65.8 ± 6.8/mm2 (position 7), 56.7 ± 4.8/mm2 (position 8), and 79.3 ± 21.7/mm2 in average.

A trend in cell density decrease from the port loaded with 20 μl to the port loaded with 18 μl was observed as 94.2 ± 21.7/mm2 (position 1) vs. 56.7 ± 4.8/mm2 (position 8) (Figures 3(a) and 3(e)). These experiments show that the 2 μl volume difference between two ports was not capable of pushing the cell solution through the whole microfluidic channel, which was confirmed by the observation of a significant decrease in concentrations of the suspended cells in the downstream of the microfluidic channel (positions 7 and 8).

Cell loading densities for the setup of 20 μl vs. 15 μl were quantified as 105.0 ± 18.1/mm2 (position 1), 100.2 ± 20.8/mm2 (position 2), 94.6 ± 13.7/mm2 (position 3), 100.9 ± 17.0/mm2 (position 4), 91.6 ± 16.3/mm2 (position 5), 94.6 ± 15.9/mm2 (position 6), 91.8 ± 9.7/mm2 (position 7), 89.6 ± 8.2/mm2 (position 8), and 96.0 ± 16.3/mm2 in average.

This is the optimal choice since the averaged cell density (96.0 ± 16.3/mm2) approaches the idea cell loading density of 100/mm2 and the ratio of standard deviation to average was the lowest among all the four setups (Figures 3(b) and 3(e)). In this setup, cell suspension solutions were assumed to replace the culture medium solutions inside microfluidic channels thoroughly as the first step, followed by cell seeding on the substrates.

Cell loading densities for the setup of 20 μl vs. 10 μl were quantified as 220.8 ± 36.7/mm2 (position 1), 209.2 ± 13.8/mm2 (position 2), 184.2 ± 15.9/mm2 (position 3), 162.5 ± 10.2/mm2 (position 4), 149.2 ± 12.3/mm2 (position 5), 143.7 ± 8.4/mm2 (position 6), 127.1 ± 7.4/mm2 (position 7), 140.0 ± 17.4/mm2 (position 8), and 167.1 ± 37.2/mm2 in average.

A trend in cell density decrease from the port loaded with 20 μl to the port loaded with 10 μl was observed (220.8 ± 36.7/mm2 (position 1) vs. 140.0 ± 17.4/mm2 (position 8)) (Figures 3(c) and 3(e)). In addition, the quantified averaged cell density number was much higher than the ideal cell loading density (167.1 ± 37.2/mm2 vs. 100/mm2). The 10 μl volume difference may lead to a prolonged cell flushing process. As the cell suspension solution was flushed from position 1 to position 8, there was a concentration decrease due to the concurrent cell seeding process, which results in lower cell seeding densities in the downstream of microfluidic channels compared to upstream counterparts.

Cell loading densities for the setup of 20 μl vs. 0 μl were quantified as 57.5 ± 35.5/mm2 (position 1), 87.2 ± 47.9/mm2 (position 2), 106.6 ± 60.7/mm2 (position 3), 135.3 ± 54.2/mm2 (position 4), 140.9 ± 51.5/mm2 (position 5), 126.9 ± 14.4/mm2 (position 6), 131.3 ± 23.8/mm2 (position 7), 124.7 ± 30.1/mm2 (position 8), and 113.8 ± 51.1/mm2 in average.

A trend in cell density increase from the port loaded with 20 μl to the port loaded with 0 μl was located (57.5 ± 35.5/mm2 (position 1) vs. 124.7 ± 30.1/mm2 (position 8)) (Figures 3(d) and 3(e)). It was speculated that the 20 μl volume difference lead to a prolonged cell flushing process, together with cellular seeding on micro channels. Due to the existence of the 20 μl volume difference, a higher flow rate compared to the setup of 20 μl vs. 10 μl was produced, which lead to cell settlement in the downstream rather than in the upstream of microfluidic channels. Thus a higher cell seeding density in position 8 than position 1 was recorded.

B. Effect of extracellular matrix on VSMC phenotypes

VSMCs have been demonstrated to have contractile or synthetic phenotypes.11,50 Contractile VSMCs are featured with limited proliferation capabilities while synthetic VSMCs are characterized by high proliferation and extracellular matrix secretion. In the local microenvironments of VSMCs, extracellular matrix of fibronectin and collagen were located and their effects on VSMC phenotypes were investigated in conventional cell culture models.51,52 This study was designed to investigate the effects of extracellular matrix on the phenotypes of VSMCs in the microfluidic environment.

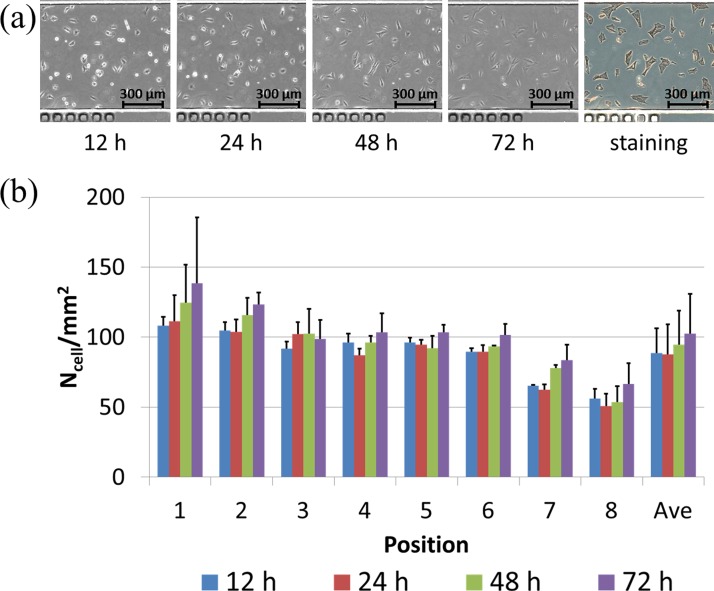

Figure 4(a) shows the microscopic images of VSMCs cultured on the glass substrate without modifications in a time sequence, followed by an endpoint immunostaining of alpha actin filaments. Based on the manual cell counting, the cell numbers were quantified as 88.5 ± 17.9/mm2 (12 h), 87.7 ± 21.6/mm2 (24 h), 94.5 ± 24.5/mm2 (48 h), and 102.4 ± 28.5/mm2 (72 h) (see Figure 4(b)).

FIG. 4.

(a) Microscopic pictures of VSMCs cultured on bare glass surfaces without modification in a time sequence (12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h (left to right)), followed by endpoint immunostaining of alpha actin filaments. (b) Cell numbers were quantified as 88.5 ± 17.9/mm2 (12 h), 87.7 ± 21.6/mm2 (24 h), 94.5 ± 24.5/mm2 (48 h), and 102.4 ± 28.5/mm2 (72 h).

Within the first 24 h of cell seeding, VSMCs were noticed to have limited surface spreading areas and no cellular proliferations (88.5 ± 17.9/mm2 (12 h) vs. 87.7 ± 21.6/mm2 (24 h)) due to the bare glass surface without extracellular matrix coating. Starting from 24 h after cell seeding, VSMCs were noticed to increase in surface spreading areas with noticeable cellular proliferations from 87.7 ± 21.6/mm2 (24 h) to 102.4 ± 28.5/mm2 (72 h).

It was speculated that within the first 24 h, VSMCs secreted extracellular matrix macromolecules on glass substrates as extracellular modifications, which lead to cellular proliferations from 24 h to 72 h. These results indicate that VSMCs maintained the synthetic phenotype during the on-chip culture process, featured with extracellular molecule secretions and cellular proliferations.

Figure 5(a) shows the microscopic images of VSMCs cultured on collagen coated glass substrates in a time sequence, followed by an endpoint immunostaining of alpha actin filaments. Based on the manual cell counting, the cell numbers were quantified as 93.4 ± 13.2/mm2 (12 h), 106.7 ± 12.9/mm2 (24 h), 112.7 ± 13.9/mm2 (48 h), and 111.3 ± 13.4/mm2 (72 h) (see Figure 5(b)).

FIG. 5.

(a) Microscopic pictures of VSMCs cultured on collagen coated glass substrates in a time sequence (12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h (left to right)), followed by endpoint immunostaining of alpha actin filaments. (b) Cell numbers were quantified as 93.4 ± 13.2/mm2 (12 h), 106.7 ± 12.9/mm2 (24 h), 112.7 ± 13.9/mm2 (48 h), and 111.3 ± 13.4/mm2 (72 h).

Within the first 48 h of cell seeding, noticeable VSMC proliferations were located with quantified cell numbers increased from 93.4 ± 13.2/mm2 (12 h) to 106.7 ± 12.9/mm2 (48 h), as an indicator of the synthetic phenotype. From 48 h to 72 h, no significant cellular proliferation was noticed (112.7 ± 13.9/mm2 (48 h) vs. 111.3 ± 13.4/mm2 (72 h)), suggesting that VSMCs change from the synthetic phenotype to the contractile phenotype.

Figure 6(a) shows the microscopic images of VSMCs cultured on PLL coated glass substrates in a time sequence, followed by an endpoint immunostaining of alpha actin filaments. Based on the manual cell counting, the cell numbers were quantified as 150.1 ± 33.2/mm2 (12 h), 166.2 ± 42.1/mm2 (24 h), 188.1 ± 70.2/mm2 (48 h), and 173.6 ± 62.9/mm2 (72 h) (Figure 6(b)).

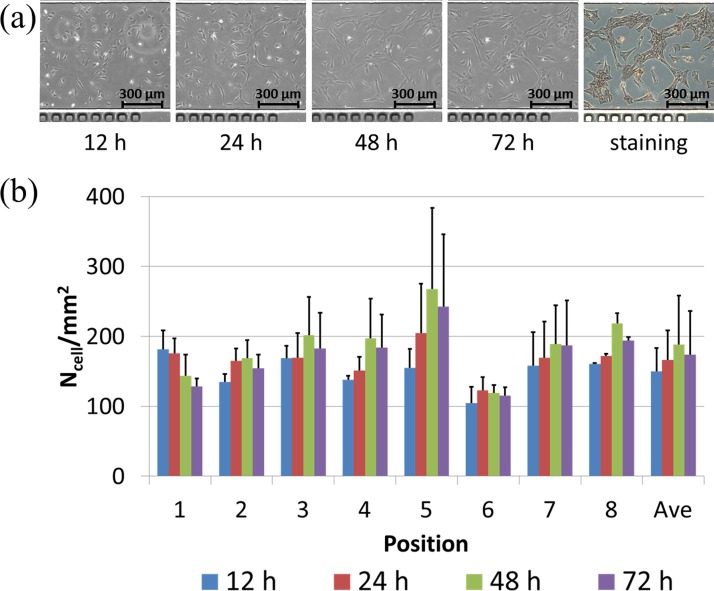

FIG. 6.

(a) Microscopic pictures of VSMCs cultured on PLL coated glass substrates in a time sequence (12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h (left to right)), followed by endpoint immunostaining of alpha actin filaments. (b) Cell numbers were quantified as 150.1 ± 33.2/mm2 (12 h), 166.2 ± 42.1/mm2 (24 h), 188.1 ± 70.2/mm2 (48 h), and 173.6 ± 62.9/mm2 (72 h).

Within the first 48 h of cell seeding, noticeable VSMC proliferations were located with quantified cell numbers increased from 150.1 ± 33.2/mm2 (12 h) to 188.1 ± 70.2/mm2 (48 h), as an indicator of the synthetic phenotype. From 48 h to 72 h, a decrease in cellular proliferation was noticed (188.1 ± 70.2/mm2 (48 h) vs. 173.6 ± 62.9/mm2 (72 h)), suggesting that VSMCs change from the synthetic phenotype to the contractile phenotype.

Figure 7(a) shows the microscopic images of VSMCs cultured on fibronectin coated glass substrates in a time sequence, followed by an endpoint immunostaining of alpha actin filaments. Based on the manual cell counting, the cell numbers were quantified as 111.9 ± 13.4/mm2 (12 h), 127.5 ± 18.0/mm2 (24 h), 118.8 ± 20.0/mm2 (48 h), and 120.6 ± 21.8/mm2 (72 h) (see Figure 7(b)).

FIG. 7.

(a) Microscopic pictures of VSMCs cultured on fibronectin coated glass substrates in a time sequence (12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h (left to right)), followed by endpoint immunostaining of alpha actin filaments. (b) Cell numbers were quantified as 111.9 ± 13.4/mm2 (12 h), 127.5 ± 18.0/mm2 (24 h), 118.8 ± 20.0/mm2 (48 h) and 120.6 ± 21.8/mm2 (72 h).

Within the first 24 h of cell seeding, noticeable VSMC proliferations were located with quantified cell numbers increased from 111.9 ± 13.4/mm2 (12 h) to 127.5 ± 18.0/mm2 (48 h), as an indicator of the synthetic phenotype. From 24 h to 48 h, a decrease in cellular proliferation was noticed (127.5 ± 18.0/mm2 (24 h) vs. 118.8 ± 20.0/mm2 (48 h)), suggesting that VSMCs change from the synthetic phenotype to the contractile phenotype, which was further confirmed by the following 24 h with no significant cellular proliferation (118.8 ± 20.0/mm2 (48 h) vs. 120.6 ± 21.8/mm2 (72 h)).

In summary, for VSMCs cultured in microfluidic channels coated with extracellular matrix (e.g., collagen, PLL, and fibronectin), cellular proliferations were initially noticed, followed by stable cell numbers without cell doubling, indicating that VSMCs changed from the synthetic phenotype to the contractile phenotype. Since cells in the middle areas of the microchannels with limited access to fresh medium (positions 4 and 5) and cells in the areas close to channel ports with easy access to fresh medium (positions 1 and 8) demonstrated similar trends (Figures 5(b), 6(b), and 7(b)), these proliferation rate variations and phenotype transitions have no relationship with nutrition transportation. Thus it was speculated that the height of microfluidic channels (100 μm) may provide geometry limitations53 or the thickness of PDMS (2 mm) may limit oxygen transportation,54 which was responsible for cellular proliferation and phenotype variations.

IV. CONCLUSION

This paper presented a tubing-free microfluidic platform for VSMC culture where extracellular matrix coating, VSMC seeding, culture and observation, and immunostaining were demonstrated. Based on operation optimization, even distributions of cells within microfluidic channels (96.0 ± 16.3/mm2) was realized. Compared to bare glass surface, extracellular matrix (e.g., collagen, PLL, and fibronectin) coated substrates lead to VSMC proliferations and phenotype variations in a time sequence. As a platform technology, this microfluidic device was confirmed to be capable of functioning as a new VSMC culture model for VSMC studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge financial support from National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, Grant No. 2014CB744602), Special Financial Grant from the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2013T60950), Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81261120561 and 61201077), National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program, Grant No. 2014AA093408) and Beijing NOVA Program.

References

- 1.Hedin U., Roy J., and Tran P. K., “ Control of smooth muscle cell proliferation in vascular disease,” Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 15, 559–565 (2004). 10.1097/00041433-200410000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clowes A. W., Clowes M. M., Fingerle J., and Reidy M. A., “ Regulation of smooth muscle cell growth in injured artery,” J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 14, S12–S15 (1989). 10.1097/00005344-198900146-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillis E., Laer L. V., and Loeys B. L., “ Genetics of thoracic aortic aneurysm: At the crossroad of transforming growth factor-beta signaling and vascular smooth muscle cell contractility,” Circ. Res. 113, 327–340 (2013). 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson R. W., Liao S., and Curci J. A., “ Vascular smooth muscle cell apoptosis in abdominal aortic aneurysms,” Coron. Artery Dis. 8, 623–631 (1997). 10.1097/00019501-199710000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudijanto A., “ The role of vascular smooth muscle cells on the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis,” Acta Medica Indonesiana 39, 86–93 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raines E. W. and Ross R., “ Smooth muscle cells and the pathogenesis of the lesions of atherosclerosis,” British Heart J. 69, S30–S37 (1993). 10.1136/hrt.69.1_Suppl.S30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gotlieb A. I., “ Smooth muscle and endothelial cell function in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis,” Can. Med. Assoc. J. 126, 903–908 (1982). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marx S. O., Totary-Jain H., and Marks A. R., “ Vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in restenosis,” Circ.: Cardiovasc. Interventions 4, 104–111 (2011). 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.957332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andres V., “ Control of vascular smooth muscle cell growth and its implication in atherosclerosis and restenosis (review),” Int. J. Mol. Med. 2, 81–89 (1998). 10.3892/ijmm.2.1.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proudfoot D. and Shanahan C., “ Human vascular smooth muscle cell culture,” Methods Mol. Biol. 806, 251–263 (2012). 10.1007/978-1-61779-367-7_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Absher M., Woodcock-Mitchell J., Mitchell J., Baldor L., Low R., and Warshaw D., “ Characterization of vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype in long-term culture,” In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.: J. Tissue Cult. Assoc. 25, 183–192 (1989). 10.1007/BF02626176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitesides G. M., “ The origins and the future of microfluidics,” Nature 442, 368–373 (2006). 10.1038/nature05058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wootton R. C. and Demello A. J., “ Microfluidics: Exploiting elephants in the room,” Nature 464, 839–840 (2010). 10.1038/464839a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sackmann E. K., Fulton A. L., and Beebe D. J., “ The present and future role of microfluidics in biomedical research,” Nature 507, 181–189 (2014). 10.1038/nature13118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young E. W. and Beebe D. J., “ Fundamentals of microfluidic cell culture in controlled microenvironments,” Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 1036–1048 (2010). 10.1039/b909900j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyvantsson I. and Beebe D. J., “ Cell culture models in microfluidic systems,” Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 1, 423–449 (2008). 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.113042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma H., Xu H., and Qin J., “ Biomimetic tumor microenvironment on a microfluidic platform,” Biomicrofluidics 7, 11501 (2013). 10.1063/1.4774070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wlodkowic D. and Cooper J. M., “ Tumors on chips: Oncology meets microfluidics,” Curr. Opin. Chem. Bio. 14, 556–567 (2010). 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soe A. K., Nahavandi S., and Khoshmanesh K., “ Neuroscience goes on a chip,” Biosens. Bioelectron. 35, 1–13 (2012). 10.1016/j.bios.2012.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong K. H., Chan J. M., Kamm R. D., and Tien J., “ Microfluidic models of vascular functions,” Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 14, 205–230 (2012). 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071811-150052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Meer A. D., Poot A. A., Duits M. H., Feijen J., and Vermes I., “ Microfluidic technology in vascular research,” J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2009, 823148 (2009). 10.1155/2009/823148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goessl A., Bowen-Pope D. F., and Hoffman A. S., “ Control of shape and size of vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro by plasma lithography,” J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 57, 15–24 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thakar R. G., Ho F., Huang N. F., Liepmann D., and Li S., “ Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cells by micropatterning,” Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 307, 883–890 (2003). 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)01285-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thapa A., Webster T. J., and Haberstroh K. M., “ Polymers with nano-dimensional surface features enhance bladder smooth muscle cell adhesion,” J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A 67A, 1374–1383 (2003). 10.1002/jbm.a.20037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller D. C., Thapa A., Haberstroh K. M., and Webster T. J., “ Endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cell function on poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) with nano-structured surface features,” Biomaterials 25, 53–61 (2004). 10.1016/S0142-9612(03)00471-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaari N., Rajagopalan P., Kim S. K., Engler A. J., and Wong J. Y., “ Photopolymerization in microfluidic gradient generators: Microscale control of substrate compliance to manipulate cell response,” Adv. Mater. 16, 2133–2137 (2004). 10.1002/adma.200400883 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glawe J. D., Hill J. B., Mills D. K., and McShane M. J., “ Influence of channel width on alignment of smooth muscle cells by high-aspect-ratio microfabricated elastomeric cell culture scaffolds,” J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A 75A, 106–114 (2005). 10.1002/jbm.a.30403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarkar S., Dadhania M., Rourke P., Desai T. A., and Wong J. Y., “ Vascular tissue engineering: microtextured scaffold templates to control organization of vascular smooth muscle cells and extracellular matrix,” Acta Biomater. 1, 93–100 (2005). 10.1016/j.actbio.2004.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yim E. K. F., Reano R. M., Pang S. W., Yee A. F., Chen C. S., and Leong K. W., “ Nanopattern-induced changes in morphology and motility of smooth muscle cells,” Biomaterials 26, 5405–5413 (2005). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen J. Y., Chan-Park M. B., Feng Z. Q., Chan V., and Feng Z. W., “ UV-embossed microchannel in biocompatible polymeric film: Application to control of cell shape and orientation of muscle cells,” J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part B 77B, 423–430 (2006). 10.1002/jbm.b.30449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen J. Y., Chan-Park M. B., He B., Zhu A. P., Zhu X., Beuerman R. W.et al. , “ Three-dimensional microchannels in biodegradable polymeric films for control orientation and phenotype of vascular smooth muscle cells,” Tissue Eng. 12, 2229–2240 (2006). 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng J., Chan-Park M. B., Shen J., and Chan V., “ Quick layer-by-layer assembly of aligned multilayers of vascular smooth muscle cells in deep microchannels,” Tissue Eng. 13, 1003–1012 (2007). 10.1089/ten.2006.0223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plouffe B. D., Njoka D. N., Harris J., Liao J., Horick N. K., Radisic M.et al. , “ Peptide-mediated selective adhesion of smooth muscle and endothelial cells in microfluidic shear flow,” Langmuir 23, 5050–5055 (2007). 10.1021/la0700220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung S., Sudo R., Mack P. J., Wan C.-R., Vickerman V., and Kamm R. D., “ Cell migration into scaffolds under co-culture conditions in a microfluidic platform,” Lab Chip 9, 269–275 (2009). 10.1039/b807585a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isenberg B. C., Dimilla P. A., Walker M., Kim S., and Wong J. Y., “ Vascular smooth muscle cell durotaxis depends on substrate stiffness gradient strength,” Biophys. J. 97, 1313–1322 (2009). 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thakar R. G., Cheng Q., Patel S., Chu J., Nasir M., Liepmann D.et al. , “ Cell-shape regulation of smooth muscle cell proliferation,” Biophys. J. 96, 3423–3432 (2009). 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cao Y., Poon Y. F., Feng J., Rayatpisheh S., Chan V., and Chan-Park M. B., “ Regulating orientation and phenotype of primary vascular smooth muscle cells by biodegradable films patterned with arrays of microchannels and discontinuous microwalls,” Biomaterials 31, 6228–6238 (2010). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rayatpisheh S., Poon Y. F., Cao Y., Feng J., Chan V., and Chan-Park M. B., “ Aligned 3D human aortic smooth muscle tissue via layer by layer technique inside microchannels with novel combination of collagen and oxidized alginate hydrogel,” J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A 98A, 235–244 (2011). 10.1002/jbm.a.33085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams C., Brown X. Q., Bartolak-Suki E., Ma H., Chilkoti A., and Wong J. Y., “ The use of micropatterning to control smooth muscle myosin heavy chain expression and limit the response to transforming growth factor β1 in vascular smooth muscle cells,” Biomaterials 32, 410–418 (2011). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez-Rodriguez R., Munoz-Berbel X., Demming S., Buttgenbach S., Herrera M. D., and Llobera A., “ Cell-based microfluidic device for screening anti-proliferative activity of drugs in vascular smooth muscle cells,” Biomed. Microdevices 14, 1129–1140 (2012). 10.1007/s10544-012-9679-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li J., Zhang K., Yang P., Liao Y., Wu L., Chen J.et al. , “ Research of smooth muscle cells response to fluid flow shear stress by hyaluronic acid micro-pattern on a titanium surface,” Exp. Cell Res. 319, 2663–2672 (2013). 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi J. S., Piao Y., and Seo T. S., “ Circumferential alignment of vascular smooth muscle cells in a circular microfluidic channel,” Biomaterials 35, 63–70 (2014). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.09.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y., Ng S. S., Wang Y., Feng H., Chen W. N., Chan-Park M. B.et al. , “ Collective cell traction force analysis on aligned smooth muscle cell sheet between three-dimensional microwalls,” Interface Focus 4, 20130056 (2014). 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Puccinelli J. P., Su X., and Beebe D. J., “ Automated high-throughput microchannel assays for cell biology: Operational optimization and characterization,” J. Assoc. Lab. Autom. 15, 25–32 (2010). 10.1016/j.jala.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meyvantsson I., Warrick J. W., Hayes S., Skoien A., and Beebe D. J., “ Automated cell culture in high density tubeless microfluidic device arrays,” Lab Chip 8, 717–724 (2008). 10.1039/b715375a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walker G. and Beebe D. J., “ A passive pumping method for microfluidic devices,” Lab Chip 2, 131–134 (2002). 10.1039/b204381e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takayama S., McDonald J. C., Ostuni E., Liang M. N., Kenis P. J. A., Ismagilov R. F.et al. , “ Patterning cells and their environments using multiple laminar fluid flows in capillary networks,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96, 5545–5548 (1999). 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takayama S., Ostuni E., LeDuc P., Naruse K., Ingber D. E., and Whitesides G. M., “ Subcellular positioning of small molecules,” Nature 411, 1016 (2001). 10.1038/35082637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takayama S., Ostuni E., LeDuc P., Naruse K., Ingber D. E., and Whitesides G. M., “ Selective chemical treatment of cellular microdomains using multiple laminar streams,” Chemistry and Biology 10, 123–130 (2003). 10.1016/S1074-5521(03)00019-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weissberg P. L., Cary N. R., and Shanahan C. M., “ Gene expression and vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype,” Blood Pressure, Suppl. 2, 68–73 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hayward I. P., Bridle K. R., Campbell G. R., Underwood P. A., and Campbell J. H., “ Effect of extracellular matrix proteins on vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype,” Cell Biol. Int. 19, 839–846 (1995). 10.1006/cbir.1995.1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stegemann J. P., Hong H., and Nerem R. M., “ Mechanical, biochemical, and extracellular matrix effects on vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype,” J. Appl. Physiol. 98, 2321–2327 (2005). 10.1152/japplphysiol.01114.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu H., Meyvantsson I., Shkel I. A., and Beebe D. J., “ Diffusion dependent cell behavior in microenvironments,” Lab Chip 5, 1089–1095 (2005). 10.1039/b504403k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leclerc E., Sakai Y., and Fujii T., “ Cell culture in 3-Dimensional microfluidic structure of PDMS (polydimethylsiloxane),” Biomed. Microdevices 5, 109–114 (2003). 10.1023/A:1024583026925 [DOI] [Google Scholar]