Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are the most frequent mesenchymal tumors of the digestive tract. Extraintestinal locations (EGIST) have been described showing similar pattern of immunohistochemical markers than GIST. Inhibitors of tyrosine kinases such as Imatinib or Sunitinib are the mainstay treatment in the management of advanced or metastatic GIST. Complete pathological response to these agents is an extremely rare event, especially in the case of EGIST due to its more aggressive behavior reported.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

Here we describe the case of a 61 years old woman, with an advanced GIST, who was operated after 10 months of Imatinib mesylate. The biopsy demonstrated the extra intestinal location of the tumor and a complete pathological response was confirmed.

DISCUSSION

Complete pathological response to Imatinib is a rare event. To our knowledge, this is the first report of complete response in an EGIST. New clinical, radiological and metabolic criteria of tumoral response to neoadjuvant treatment are revised.

CONCLUSION

EGIST complete pathological response to Imatinib can be achieved. However, recommendation of systematic neoadjuvant therapy with Imatinib remains investigational and more studies are warranted in the future.

Keywords: EGIST, GIST, Imatinib, Complete pathological response

1. Background

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are the most frequent mesenchymal tumors of the alimentary tract, accounting for only 0.2% of all gastrointestinal tumors. Extra intestinal locations (EGIST) have been rarely described,1 showing similar pattern of immunohistochemical markers than GIST.

Inhibitors of tyrosine kinases (TKI) such as Imatinib or Sunitinib are the mainstay treatment in the management of advanced or metastatic GIST patients.2 Complete pathological response to these agents is an extremely rare event,3 especially in the case of EGIST due to its more aggressive behavior reported.4

2. Presentation of case

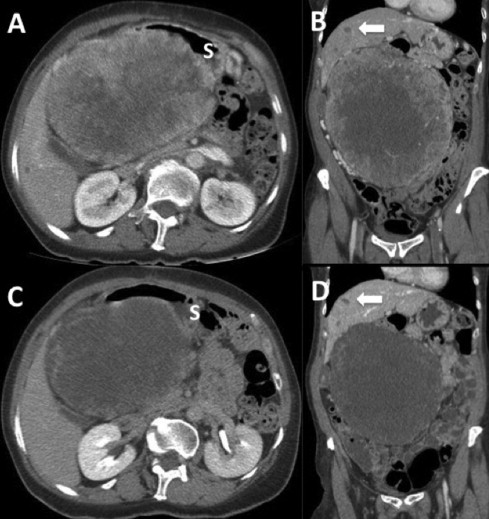

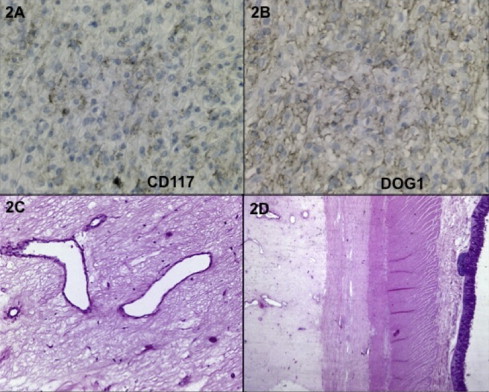

We report the case of a 61 year-old woman with no relevant past medical history who was initially evaluated in a center without experience in oncological cases. She complained of abdominal distension, 12 kg weight loss and early satiety eight months before first medical evaluation. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and colonoscopy were normal. Contrast-enhanced abdominopelvic Computed Tomography (CT) scan showed a 20 cm highly vascular intraabdominal tumor with central necrosis and gastric compression. Also small hepatic nodules were observed, consistent with metastases. She was submitted to an exploratory laparotomy showing an unresectable giant tumor, thus only an incisional biopsy was performed and then she was derived to our center. After oncological committee evaluation, a new CT scan was performed (Fig. 1A and B). The paraffin embedded biopsy retrieved was further studied with immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses, which showed low expression of CD117, high CD34 and partial DOG-1 expression, with negative Desmin and S100 expressions (Fig. 2A and B). The morphologic and IHC analyses were compatible with a GIST. Since the high risk of dissemination after the open biopsy added to the large size of tumor and the presence of images suspicious of liver metastases, Imatinib mesylate 400 mg per day was started. The treatment was well tolerated, with no grade 3 adverse events. After 10 months of Imatinib, CT scan showed a 2 cm decrease in tumor size and diminishment of contrast enhancement (Fig. 1C and D). The case was discussed again in committee and resective surgery was proposed.

Fig. 1.

Intravenous contrast-enhanced abdominopelvic CT scan. (A) and (B) Sagittal and coronal slides after open laparotomic biopsy showing a 20 cm abdominal mass with heterogeneous contrast enhancement and central necrosis. Arrow shows liver nodules suspicious of metastases; S denotes stomach. (C) and (D) Sagittal and coronal slides after 10 months of treatment with Imatinib. Note the reduction in tumoral contrast enhancement, a minor decrease in size and stability of liver lesions.

Fig. 2.

Pre and postoperative biopsies. (A) Immunohistochemistry performed in the material obtained in the initial biopsy and showed low intensity CD117-positive staining and in (B) a positive DOG1 expression. Picture (C) and (D) show the postoperative biopsy of the tumor resected demonstrating hyaline fibrosis with intense connective tissue without tumoral cells. Picture (D) shows no continuity with the muscularis propia of the bowel, suggesting an EGIST.

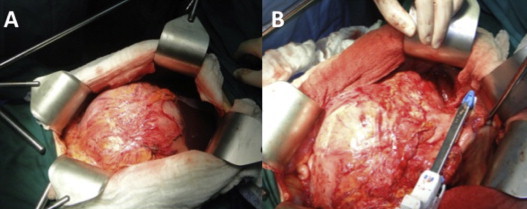

On re-laparotomy the tumor was adherent to the gastric antrum and transverse colon, with no clear dissection plane. An en-block stapled distal gastrectomy and a transverse colectomy was performed (Fig. 3). Gastrectomy was reconstructed with a transmesocolic Roux-Y gastrojejunostomy and the colon was primarily anastomosed. The liver was explored and two small whitish nodules on segments IVa and V were identified and resected. No other lesions were observed in the intraoperative ultrasound. Frozen biopsies informed calcium granulomas.

Fig. 3.

Surgical findings after one year of Imatinib. (A) On laparotomy a large tumor was seen with intense adherences to stomach and transverse colon. (B) A stapled distal gastrectomy was performed with negative surgical margin.

On fifth postoperative day patient evolved with fever and a CT-scan showed a subhepatic abscess. She was taken to the operating room and a leak from the duodenal stump was confirmed. Abscess was drained and drains were placed near the duodenal stump. Thereafter she had an uneventful recovery and was discharged on 21th postoperative day with oral antibiotics.

The final biopsy specimen showed a 20 cm × 16 cm mass and 2734 g weight, constituted by a highly vascularized fibro-connective tissue with hialin fibrosis and cavities with hemorrhagic content. No evidence of tumor cells was seen in any sample. Also there was no contact between the mass and the stomach or the colon surface (Fig. 2C and D).

The oncological committee evaluated the case after surgery and two more years of Imatinib was proposed. At three months of surgery, patient is asymptomatic and has not presented any adverse events.

3. Discussion

Since the first description of a dramatic and sustained response of a GIST patient on 20013 it is recognized that TKI such as Imatinib are the mainstay treatment in the management of advanced or metastatic GIST patients. These agents block signaling via KIT or Platelet Derived Grow Factor Receptor Alpha (PDGFRa) by binding to the ATP-binding pocket required for phosphorylation and activation of the receptor. In our case, CD117 (c-Kit) showed low expression, nevertheless DOG-1 (an abbreviation of Discovered on GIST-1)5 was positive. This marker can differentiate a CD117 negative GIST from competing diagnoses in order to choose the appropriate treatment.

A guideline from the National Cancer Comprehensive Network (NCCN) recommends the use of Imatinib 400 mg in advanced or metastatic GIST in all patients. However, if molecular diagnosis is available and an exon 9 KIT mutation is positive, to augment the dose to 800 mg is a possibility due to lesser response to standard doses compared to exon 11 KIT mutation patients.6–8 In contrast, the European Society of Medical Oncology suggests performing molecular testing to all patients.9

Surgery is the only potentially cure for GIST. In borderline resectable primary tumors, preoperative Imatinib is a possible option but there are no randomized trials assessing the benefit of neoadjuvant treatment. Eisenberg et al.10 published a prospective study with 63 patients receiving preoperative Imatinib for 8–12 weeks. Only 7% of primary resectable GIST achieved a partial response and 83% presented a stable disease.10 Whether this poor objective response might be improved prolonging the period of treatment is currently unknown. In another study,2 the authors observed that the time needed to achieve a maximal response was 4–6 months, suggesting long-term treatment until one year on these patients.3

On the other hand, the best method to assess response to neoadjuvant treatment in GIST is still controversial. The current Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) use standard images as CT as the gold standard for measuring target lesions in solid tumors.11 However, its use in the context of newer molecular therapy is controversial.12 In some GIST responding tumors, size may actually increase in size during early treatment as a consequence of intratumoral hemorrhage, necrosis or myxoid degeneration. An alternative response criteria has been proposed, including an early decrease in tumor density on CT scan or decrease of3 10% of size or no new lesions and no obvious progression of non-measurable disease. The so-called Choi criteria13 outperforms the RECIST criteria in the analysis of specific oncologic endpoints in one report14 but not in another.15 In addition a recent report showed that the metabolic response, measured by the change of SUV uptake using 18F-FDG PET at baseline and days after the start of Imatinib, might select patients with greater likelihood of response.16

Guidelines from the NCCN recommend biopsy prior to Imatinib initiation.8 Probably an endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy was a better option in this particular case, nevertheless the oncologic principles of biopsy were not considered and an open laparotomic biopsy was performed which theoretically could spread tumor in the abdominal cavity, which fortunately does not occur. The tumor showed a partial response according to Choi criteria13 and therefore it seemed reasonable to explore the chance of resectability, which was completely performed.

According to the final biopsy there are two further points to discuss. First, it is uncertain the origin of this tumor since histologically there was no obvious contact between the tumor and serosal or muscular layer of the stomach or colon. Primary Extra-Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (EGIST) have been described with immuno-histochemical analyses showing that most of them express KIT and 50% express CD34.1 Thus it is probably that Cajal's cells are not the only origin for GISTs. EGIST seems to behave more aggressively, more resembling of an intestinal than a gastric GIST.4 Considering that the benefit of long-term Imatinib has been mainly demonstrated in high-risk patients17 it seems reasonable to offer a total of three years of treatment to our patient.

The other issue to discuss in this case is the complete pathological response (pCR) observed in the final biopsy, which represents a rare event reported. The only prospective report evaluating the benefit of neoadjuvant treatment, did not describe its pCR rate,10 but several retrospective studies (Table 1) and case reports (not shown in table) are able to estimate that up to 10% of patients will developed a pCR after the use of Imatinib. As we mentioned above, the use of standard response criteria such as RECIST, may not be useful in this setting. In one study, CT scan inaccurately predicts treatment response in 30% of patients.18 In fact, in our case CT evaluation after Imatinib was consistent with stable disease failing to anticipate the diagnosis of pCR. In other primary tumors (e.g. breast carcinoma), the occurrence of pCR has been able to predict long-term outcome in several neoadjuvant studies and is therefore a potential surrogate marker for survival.19 However, the low incidence of this disease and the small experience in neoadjuvant treatment in this group of patients, make such analysis impossible to perform at this time. Whether the pCR rate may be further improved by prolonging duration of treatment or not is currently unknown. Another advantage of preoperative systemic therapy is that allows the evaluation dynamically and in vivo of potential biomarkers to predict response.

Table 1.

Comparison of studies using Imatinib as neoadjuvant therapy in gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

| Study | Number of patients | Median time of neoadjuvant treatment (months) | Complete surgical resection (%) | Complete pathological response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eisenberg10 | 52a (30 non-metastatic) | 2 (1–3) | 38.5% | Not reported |

| Andtbacka et al.20 | 46 (11 non-metastatic) | 12.9 (2.8–31.8) | 48% (100% in non-metastatic) | 6.5% (9.0% in non-metastatic) |

| Bonvalot et al.21 | 180 (5 non-metastatic) | 12 (1–30) | 12% | 9.0% |

| Raut et al.22 | 69 | Not reported | 39.1% | Not reported |

| Scaife et al.18 | 126 | 10 (2–16) | 13.5% | 12% |

| Machlenkin et al.23 | 9b,c | 1–6 | 66.6% | 16.7% |

| Jakob et al.24 | 16b,c | 14 (6–60) | 93.7% (one patient refused surgery) | Not reported |

| Tielen et al.25 | 22b,c | 9 (2–53) | 77% | Not reported |

| Gronchi et al.26 | 38d | 17 (7–39) | 73.7% | 26.3% (>90% of histological response) |

| Bauer et al.27 | 90 (all metastatic) | 12.2 (6.1–25) | 12.2% | 8.3% |

| Rutkowski et al.28 | 141 | 15 (4–32) | 18.4% | 8.3% |

We included only analyzable patients.

We excluded patients who did not receive neoadjuvant Imatinib.

Study includes only patients with rectal GIST.

We considered only operable patients.

4. Conclusion

EGIST complete pathological response to Imatinib can be achieved. However, recommendation of systematic neoadjuvant therapy with Imatinib remains investigational and more studies are warranted in the future.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Nicolás Quezada, Francisco Acevedo, Andrés Marambio, Felipe León, Hector Galindo, Juan Carlos Roa and Nicolás Jarufe have no funding sources to declare.

Ethical approval

The Ethical committee of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile approved this study.

Author's contribution

Nicolás Quezada, Nicolás Jarufe and Francisco Acevedo were the major contributors in writing the case report and they were involved in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. Nicolás Jarufe and Andrés Marambio provided clinical care of the patient during his treatment and supervised the writing of the case report and were involved in the review and preparation of the manuscript. Héctor Galindo, Juan Roa and Felipe León contributed by drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Images were courtesy of the Department of Radiology and Pathology, with patient consent. All authors read and approved the final manuscript, with Felipe León and Nicolás Jarufe giving the final approval of the manuscript for submission.

Key learning points

-

•

EGIST is a rare and more aggressive tumor than traditional GIST.

-

•

They are susceptible to treatment with inhibitors of tyrosine kinases as Imatininb.

-

•

Complete pathological response is exceptional.

References

- 1.Miettinen M., Monihan J.M., Sarlomo-Rikala M., Kovatich A.J., Carr N.J., Emory T.S. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors/smooth muscle tumors (GISTs) primary in the omentum and mesentery: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1109–1118. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199909000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verweij J., Casali P.G., Zalcberg J., LeCesne A., Reichardt P., Blay J.Y. Progression-free survival in gastrointestinal stromal tumours with high-dose imatinib: randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1127–1134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joensuu H., Roberts P.J., Sarlomo-Rikala M., Andersson L.C., Tervahartiala P., Tuveson D. Effect of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 in a patient with a metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1052–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reith J.D., Goldblum J.R., Lyles R.H., Weiss S.W. Extragastrointestinal (soft tissue) stromal tumors: an analysis of 48 cases with emphasis on histologic predictors of outcome. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:577–585. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West R.B., Corless C.L., Chen X., Rubin B.P., Subramanian S., Montgomery K. The novel marker, DOG1, is expressed ubiquitously in gastrointestinal stromal tumors irrespective of KIT or PDGFRA mutation status. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:107–113. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63279-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heinrich M.C., Corless C.L., Demetri G.D., Blanke C.D., von Mehren M., Joensuu H. Kinase mutations and imatinib response in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4342–4349. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heinrich M.C., Owzar K., Corless C.L., Hollis D., Borden E.C., Fletcher C.D. Correlation of kinase genotype and clinical outcome in the North American Intergroup Phase III Trial of imatinib mesylate for treatment of advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor: CALGB 150105 Study by Cancer and Leukemia Group B and Southwest Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5360–5367. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demetri G.D., von Mehren M., Antonescu C.R., DeMatteo R.P., Ganjoo K.N., Maki R.G. NCCN Task Force report: update on the management of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(Suppl. 2):S1–S41. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0116. quiz S42–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:49–55. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenberg B.L., Harris J., Blanke C.D., Demetri G.D., Heinrich M.C., Watson J.C. Phase II trial of neoadjuvant/adjuvant imatinib mesylate (IM) for advanced primary and metastatic/recurrent operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): early results of RTOG 0132/ACRIN 6665. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:42–47. doi: 10.1002/jso.21160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tirkes T., Hollar M.A., Tann M., Kohli M.D., Akisik F., Sandrasegaran K. Response criteria in oncologic imaging: review of traditional and new criteria. Radiographics. 2013;33:1323–1341. doi: 10.1148/rg.335125214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishino M., Jagannathan J.P., Krajewski K.M., O'Regan K., Hatabu H., Shapiro G. Personalized tumor response assessment in the era of molecular medicine: cancer-specific and therapy-specific response criteria to complement pitfalls of RECIST. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:737–745. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi H., Charnsangavej C., Faria S.C., Macapinlac H.A., Burgess M.A., Patel S.R. Correlation of computed tomography and positron emission tomography in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor treated at a single institution with imatinib mesylate: proposal of new computed tomography response criteria. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1753–1759. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benjamin R.S., Choi H., Macapinlac H.A., Burgess M.A., Patel S.R., Chen L.L. We should desist using RECIST, at least in GIST. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1760–1764. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dudeck O., Zeile M., Reichardt P., Pink D. Comparison of RECIST and Choi criteria for computed tomographic response evaluation in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor treated with sunitinib. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1828–1833. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van den Abbeele A.D., Gatsonis C., de Vries D.J., Melenevsky Y., Szot-Barnes A., Yap J.T. ACRIN 6665/RTOG 0132 phase II trial of neoadjuvant imatinib mesylate for operable malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor: monitoring with 18F-FDG PET and correlation with genotype and GLUT4 expression. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:567–574. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.094425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joensuu H., Eriksson M., Sundby Hall K., Hartmann J.T., Pink D., Schütte J. One vs three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1265–1272. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scaife C.L., Hunt K.K., Patel S.R., Benjamin R.S., Burgess M.A., Chen L.L. Is there a role for surgery in patients with “unresectable” cKIT+ gastrointestinal stromal tumors treated with imatinib mesylate? Am J Surg. 2003;186:665–669. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Minckwitz G., Untch M., Blohmer J.U., Costa S.D., Eidtmann H., Fasching P.A. Definition and impact of pathologic complete response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1796–1804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andtbacka R.H., Ng C.S., Scaife C.L., Cormier J.N., Hunt K.K., Pisters P.W. Surgical resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors after treatment with imatinib. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:14–24. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonvalot S., Eldweny H., Pechoux C.L., Vanel D., Terrier P., Cavalcanti A. Impact of surgery on advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) in the imatinib era. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1596–1603. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raut C.P., Posner M., Desai J., Morgan J.A., George S., Zahrieh D. Surgical management of advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors after treatment with targeted systemic therapy using kinase inhibitors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2325–2331. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Machlenkin S., Pinsk I., Tulchinsky H., Ziv Y., Sayfan J., Duek D. The effect of neoadjuvant Imatinib therapy on outcome and survival after rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:1110–1115. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakob J., Mussi C., Ronellenfitsch U., Wardelmann E., Negri T., Gronchi A. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the rectum: results of surgical and multimodality therapy in the era of imatinib. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:586–592. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2647-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tielen R., Verhoef C., van Coevorden F., Reyners A.K., van der Graaf W.T., Bonenkamp J.J. Surgical management of rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:320–323. doi: 10.1002/jso.23223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gronchi A., Fiore M., Miselli F., Lagonigro M.S., Coco P., Messina A. Surgery of residual disease following molecular-targeted therapy with imatinib mesylate in advanced/metastatic GIST. Ann Surg. 2007;245:341–346. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000242710.36384.1b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bauer S., Hartmann J.T., de Wit M., Lang H., Grabellus F., Antoch G. Resection of residual disease in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors responding to treatment with imatinib. Int J Cancer. 2005;117:316–325. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rutkowski P., Nowecki Z., Nyckowski P., Dziewirski W., Grzesiakowska U., Nasierowska-Guttmejer A. Surgical treatment of patients with initially inoperable and/or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) during therapy with imatinib mesylate. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:304–311. doi: 10.1002/jso.20466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]