Abstract

Red blood cells (RBCs) possess a unique capacity for undergoing cellular deformation to navigate across various human microcirculation vessels, enabling them to pass through capillaries that are smaller than their diameter and to carry out their role as gas carriers between blood and tissues. Since there is growing evidence that red blood cell deformability is impaired in some pathological conditions, measurement of RBC deformability has been the focus of numerous studies over the past decades. Nevertheless, reports on healthy and pathological RBCs are currently limited and, in many cases, are not expressed in terms of well-defined cell membrane parameters such as elasticity and viscosity. Hence, it is often difficult to integrate these results into the basic understanding of RBC behaviour, as well as into clinical applications. The aim of this review is to summarize currently available reports on RBC deformability and to highlight its association with various human diseases such as hereditary disorders (e.g., spherocytosis, elliptocytosis, ovalocytosis, and stomatocytosis), metabolic disorders (e.g., diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, obesity), adenosine triphosphate-induced membrane changes, oxidative stress, and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Microfluidic techniques have been identified as the key to develop state-of-the-art dynamic experimental models for elucidating the significance of RBC membrane alterations in pathological conditions and the role that such alterations play in the microvasculature flow dynamics.

I. INTRODUCTION

Red blood cells (RBCs) possess a unique capacity for undergoing cellular deformation to navigate across various human microcirculation vessels, enabling them to pass through capillaries that are smaller than their diameter and to carry out their role as gas carriers between blood and tissues.1–4 Pathological alterations in RBC deformability have been associated with various diseases5 such as malaria,6,7 sickle cell anemia,8 diabetes,9 hereditary disorders,10 myocardial infarction,11 and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).12 Because of its pathophysiological importance, measurement of RBC deformability has been the focus of numerous studies over the past decades.2,13–15

Several comprehensive reviews have been published related to this issue,2,16–18 and the most recent have focused on the characterization of biomechanical properties of pathological RBCs, particularly involving sickle cell disease and Plasmodium falciparum-induced malaria.8,16,18–21 It is hence not the aim of this work to provide another detailed review of these pathologies but rather to highlight the need to provide further insight into specific pathological conditions. Reports on pathological RBCs are currently limited and, in most cases, not expressed in terms of well-defined cell membrane parameters such as elasticity and viscosity. Hence, it is often difficult to integrate these results into the basic understanding of RBC behaviour, as well as into clinical applications. Nevertheless, there is growing evidence that RBC deformability is a potential indicator of specific pathological conditions and may provide a label-free biomarker for determining cell status and properties of clinical relevance.

This review article will present data on RBC deformability in specific human diseases and is organized as follows. Section II discusses the rheological properties of healthy RBCs, which are the major determinants of cell deformability, whereas Sec. III presents a short reference to the most widely used experimental measuring methods. The next sections describe experimental studies on the deformation of single cells and/or cell populations for the following diseases: hereditary disorders (Sec. IV), metabolic disorders (Sec. V), adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-induced membrane changes (Sec. VI), oxidative stress (Sec. VII), and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (Sec. VIII). Sec. IX includes the concluding remarks and future research directions.

II. BIOMECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF HEALTHY RBCs

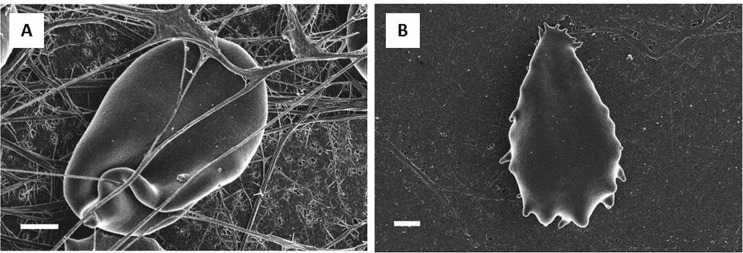

RBC deformability plays an essential role in the delivery of oxygen to tissues.5 Under physiological conditions, RBC deformability allows the flow of a single, biconcave disk-shaped RBC (Figure 1(A)), with dimensions of approximately 8 μm in diameter and ∼2 μm in thickness, through capillaries with diameters not more than 3–5 μm, thus supplying oxygen to tissues of the body. As RBCs pass through the spleen, which acts as a highly effective filter, these cells are required to traverse extremely narrow endothelial slits with a diameter of 0.5–1.0 μm. In the case of impaired RBC deformability due to pathological factors, splenic sequestration and destruction of RBCs are observed.2,13

FIG. 1.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) micrographs of a typical healthy RBC (scale = 1 μm) (A) and of the RBC membrane, showing globular structure (scale = 100 nm) (B). Adapted from Ref. 27.

The deformability of an erythrocyte is attributed to three factors: (i) The large surface area-to-volume ratio of the biconcave disc, which presents a mean cell volume (MCV) of ∼90 fl and a mean surface area (MSA) of ∼135 μm2, which is significantly greater than the surface area (97 μm2) of a sphere enclosing a volume of 90 fl;22 (ii) the viscosity of the intracellular fluid (i.e., cytoplasmic viscosity), dominated by the presence of haemoglobin; (iii) the viscoelastic properties of the cell membrane, which is a composite material consisting of three layers, a carbohydrate-rich glycocalyx on the outer surface, a lipid bilayer capable of resisting bending, and an underlying protein network, which serves as the membrane skeleton that is responsible for its deformability, flexibility, and durability and aids in recovering the discoid shape.2,14,23 The RBC surface membrane presents a globular structure (Figure 1(B)) that reflects the skeletal integrity of the cell membrane. The latter, which is measured as surface roughness, is an indicator of the functional status of the cell,9,24 changing during a disease state or in the presence of environmental stimuli such as drugs.24–26

The combination of the three factors listed above allows RBCs to undergo deformation, which facilitates their flow across the microvasculature. An abnormal increase in RBC rigidity has been associated with a change in any one or a combination of these factors.28–31 The mechanical behaviour of the RBC membrane is expressed in terms of three fundamental moduli: (a) the shear elastic modulus; (b) the area compressibility modulus; and (c) the bending modulus. The former is associated with a constant area of elongation or shear of the membrane. Area compressibility modulus, characterizing the resistance to area compression or expansion, is defined by the simple linear relation between isotropic membrane tension and relative area expansion T = K ΔA/ΔA0,2,32 and corresponds to the surface dilation without either shear or bending. Bending modulus, representing the curvature of RBC membrane, is important in driving rest shape changes, without either shear or expansion.33,34

When transient conditions occur, such as in relaxation experiments to model vascular bifurcations and changes in vessels cross section, it is possible to measure the RBC relaxation time constant, defined as the time that a deformed RBC takes to recover its original biconcave shape. It is given by the ratio of the elastic shear modulus and the membrane surface viscosity, which represents the delay of shape change due to internal friction.35–37

Another elastic modulus often used in the atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurements38,39 is Young's modulus, which is the measure of the stiffness of an elastic isotropic material and is defined as the ratio between the stress along a certain axis and the strain along the same axis.40

The experimental methods used so far to measure the membrane moduli and the other RBC properties are described in Sec. III.

III. TECHNIQUES FOR MEASURING THE BIOMECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF RBCs

Several methods have been developed to measure the membrane properties of RBCs; however, most investigators are continuously challenged with the need to develop models that simulate blood circulation in physiological conditions. The available experimental methods can be divided into two categories: instruments that measure whole blood or diluted RBC suspensions, and single-cell techniques.

The former, which include the rotational viscometer41 and ektacytometer,31,42,43 are considered as high-throughput methods; however, these do not take into account heterogeneity or size differences within the sample population of cells. Rotational viscometers have been used in determining RBC cytoplasmic viscosity by studying red cell suspensions in fluids of different viscosities such as high-molecular weight dextran;41 however, it does not provide information on geometry and membrane properties of RBCs. A rheoscope, which consists of a counter-rotating cone and plate rheometer that allows microscopic observation of blood samples placed in a flow chamber, is suitable for the study of the microrheology of blood cells and for estimating the relaxation time constant of RBCs.44–46 In this microrheologic approach, density-separated cells are subjected to graded levels of shear, which measures the steady-state elongation and the time of shape recovery after an abrupt cessation of the imposed shear. In ektacytometry, a laser diffraction viscometer, RBCs’ deformability is measured as a function of suspending medium osmolality. The deformability index (DI) curves contain information on RBC surface area, surface/volume ratio and internal viscosity. DI (often called Elongation index, EI) is defined as the ratio (L − W)/(L + W), where L and W are respectively the major and minor axes of an ellipse that represents a RBC.47,48 The curve for normal blood samples reaches a maximum at 290 mOsm/kg, indicating that normal RBCs have an optimal deformability when exposed at the tonicity to which they are normally exposed. The DI max represents an equilibrium value between the surface/volume ratio and the intracellular viscosity. When the suspending medium osmolality decreases, DI decreases too, reaching a minimum at about 135 mOsm/kg. DI min indicates the maximum possible volume that a cell can reach before hemolysis. Pathological blood samples are characterized by differences in the shape of the profile DI vs osmolality as compared to the normal one. These kinds of instruments do not provide a direct measure of the viscoelastic constants, although the output of some parameters could be related to RBC deformability.

Single-cell experimental methods include micropipette aspiration,36,49–51 optical tweezers,52–58 flickering analysis,59–63 AFM,64 and, recently, microfluidics4,65,66 and ultrasounds.67 Micropipette aspiration (Figure 2(A)) was one of the first techniques used to measure either RBC geometric (surface area and volume) or viscoelastic (surface viscosity, relaxation time constant, and shear, bending and area compressibility moduli) properties. These measurements are affected by the dependence on the size of the pipette used in the experiments (reliable comparisons can only be made between samples measured with the same pipette) and, in general, on the conditions of the experiments. Flickering analysis of RBC membrane is based on the large fluctuations of the cell shape, and is correlated to RBC mechanical properties, such as bending modulus, membrane tension and cytosolic viscosity. A recent study combines RBC membrane flickering with micro-Raman analysis, with the aim to study how oxygenation and hydration state can affect RBC mechanics.59 RBC geometric parameters have also been studied using the hanging cells method (Figure 2(B)), where single RBCs68 or blood droplets22 are hanging off the edge of the underside of a glass coverslip. Optical tweezers (Figure 2(E)), optical trapping, and other microscope-based techniques have been widely used to determine RBC membrane properties. AFM, a powerful technique for high-resolution imaging of any surface including those of cells, allows the characterization of the mechanical, electrical, and magnetic properties of cells,69,70 as well as the measurement of cell deformability in terms of the Young's modulus (Figure 2(D))39 and of membrane surface roughness.9,25,26 In addition, full-field laser interferometry,71 a non-invasive optical technique, has been used to quantify the material properties of living cells at the nanometer and millisecond scales. In particular, this technique has been used to retrieve the RBC membrane properties by quantifying RBC membrane fluctuations71,72 (Figure 2(B)).

FIG. 2.

Overview of methods for characterizing the biomechanical properties of RBCs. (A) Aspiration of an RBC into a micropipette.51 (B) Topography of a healthy RBC by full-field laser interferometry. The scale bar is 2 μm, and the colorbar scales are in μm. Adapted from Ref. 71. (C) Three-dimensional (3D) topographical image of an RBC as measured by AFM.39 (D) The distribution of the magnitude of the acoustic velocity around a levitated cell (undeformed). The acoustic velocity magnitude is in m/s. Adapted from Ref. 67. (E) Optical tweezers stretch an RBC that was loaded using a force ranging from 0 to 340 pN. From left to right: experimental observations, computed contour maps of the constant maximum principal strain distribution and one half of the full 3D biconcave shape (simulations with the cytosol). Adapted from Ref. 58. (F) Microcapillary flow (diameter = 10 μm): RBC transient shape at start-up using the same experimental conditions. Flow is from left to right. Adapted from Ref. 35.

Earlier, single cell-based methods allow the estimation of membrane properties that affect RBC deformability; however, these are also associated with specific disadvantages such as being low-throughput and static techniques. The stress imposed on the cells during analysis may not fully represent the actual conditions occurring during microcirculation, thus making it more difficult to evaluate the results in terms of clinical relevance. An alternative way to apply mechanical stresses to deform cells is based on ultrasonic radiation force that acts directly to the cell membrane. The cell can be osmotically swelled before the experiments, in order to obtain a spherical shape, that makes small deformations easier to detect67 (Figure 2(D)).

Recently, the development of microcapillary flow techniques (Figure 2(F)) and microfluidic devices (Figure 3) have successfully circumvented the problems associated with single-cell characterizations, combining high-throughput analysis and physiologically relevant flow fields.4,73–75 Microfluidics originated from an experimental program that was performed in the ‘90 s by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) of the US Department of Defense, with the aim of developing microsystems that could be used as detectors for chemical and biological threats.76

FIG. 3.

Microfluidic experimental studies of RBC flow using microcirculation-mimicking models. (A) RBC membrane elastic modulus and surface viscosity are measured by using a converging-diverging geometry. Adapted from Ref. 65 and Reproduced by permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry. (B1) Low- and (B2) high-magnification images of deformed erythrocytes in glass microchannels. Adapted from Ref. 83. (C) Flowing of RBCs in channels of different widths.89 (D1) Schematic diagram of a chamber unit for RBC deformability measurement (SiCMA chip), and (D2) Fabricated SiCMA chip with an enlarged view of the chamber array.86

Microfluidic devices, coupled with automated image analysis, are suitable for point-of-care applications,77 allowing to test a large number of cells by using microcirculation-mimicking patterns,78 transparent substrata such as polydimethylsiloxane and glass, and video microscopy.

Examples include visualizations of cell deformation as a function of pressure drop, in which the classical parachute-like shape observed in vivo was observed in in vitro experiments as well,66,79–84 estimations of cell membrane viscoelastic properties such as RBC shear elastic modulus and surface viscosity by using diverging channels,65 measurements of the RBC time recovery constant in start-up experiments,35 cell characterization by electric impedance microflow cytometry,85 and single-cell microchamber array (SiCMA) technology86,87 (Figures 3(D1) and 3(D2)). The latter applies a dielectrophoretic force to deform RBCs and used image analysis to analyse RBCs shape changes, allowing the evaluation the deformability of single RBCs in terms of Elongation Index %, defined as (x − y)/(x + y) × 100, where x and y are RBC major and minor axes, respectively. Dielectrophoretic force has been also used for the real-time separation of blood cells for a droplets of whole blood.88

Recently, RBC geometrical parameters such as RBC volume, surface area, and distribution width (RDW), which are a measurement of the size variation as well as an index of the heterogeneity that can be used as a significant diagnostic and prognostic tool in cardiovascular and thrombotic disorders,90 have been measured in microcapillary flow using high-speed microscopy.81,91,92

The use of different techniques leads to various measured values, meaning that deformation of RBCs deeply depend on the deformation protocol. This fact has been widely discussed in recent papers which state that the mechanical response of RBC is not linear.93,94 The wide discrepancies resulting from the use of different techniques can be observed in the large standard deviation of the values presented in Table I, where the average values of the geometric and mechanical properties of healthy RBCs present in the literature are reported together with their related experimental techniques.

TABLE I.

Geometric and mechanical properties of RBCs.

| Healthy RBC | Techniques | |

|---|---|---|

| Volume (μm3) | 89.4 ± 17.6 | Micropipette,95–98 hanging cells,22,68 flow channel,99 microscopic holography,100 microcapillary flow81 |

| Surface area (μm2) | 113.8 ± 27.6 | Micropipette,95–98 hanging cells,22,68 flow channel99 microscopic holography,100 microcapillary flow81 |

| Cytoplasmic viscosity (mPa/s) | 6.07 ± 3.8 | Rotational viscometer,41,101 cylindrical micropores,101 magnetic field102 |

| Surface viscosity (μN s/m) | 0.7 ± 0.2 | Micropipette,32,36,103–105 ektacytometry,37 microfluidic device65 |

| Shear elastic modulus (μN/m) | 5.5 ± 3.3 | Micropipette,49,103–106 optical tweezers,52,107 ektacytometry37 |

| Bending elastic modulus (×10−19 Nm) | 1.15 ± 0.9 | Micropipette,33,108 reflection interference contrast micrograph,109,110 AFM,111 flickering analysis,59,108,112 optical trapping,113 optical tweezers114 |

| Relaxation time constant (s) | 0.17 ± 0.08 | Optical tweezers,52 micropipette,36,103,105 optical trapping,113 rheoscope,45,115 microcapillary flow,35 microfluidic device65 |

| Area compressibility modulus (mN/m) | 399 ± 110 | Micropipette32,104,116 |

| Young's modulus (KPa) | 26 ± 7 | AFM39 |

In order to identify which technique has been used to measure the RBCs biomechanical properties, in Figure 4, eight categories have been reported, such as micropipette, flickering, viscometry, microcapillary flow/microfluidics, ektacytometry, AFM, optical tweezers, and other, where the voice “other” includes reflection interference contrast micrograph, microscopic holography, hanging cells, flow channel, magnetic field, laminar flow system, and optical interferometric technique. Data from both healthy and pathological RBCs (Hereditary membrane disorders, metabolic disorders and ATP-induced membrane changes, oxidative stress, PNH, Malaria, and Sickle cell anemia) have been considered to realize Figure 4.

FIG. 4.

Techniques used to measure a specific RBC biomechanical property.

IV. HEREDITARY MEMBRANE DISORDERS

Hereditary disorders involving the erythrocyte membrane include spherocytosis (HS), elliptocytosis (HE), ovalocytosis, and stomatocytosis (HSt). These syndromes are caused by a deficiency or dysfunction of one of the membrane skeletal proteins and constitute an important group of inherited haemolytic anemias.10,117–119 HS and HE are characterized by the presence of spherical-shaped erythrocytes and elliptical, cigar-shaped erythrocytes, respectively, and are the most common disorders of RBC membranes, affecting 1 in 2000 people of North American and Northern European countries, at a prevalence of 1 in 5000.117 Southeast Asian ovalocytosis (SAO), which is characterized by rounded elliptic or ovaloid red cells, is an uncommon variant of HE that occurs in some parts of Southeast Asia. All these diseases result from mutations in genes that code for different erythrocyte membrane proteins such as spectrin (alpha and beta), ankyrin, glycophorin C, band 3 protein, and proteins 4.1 and 4.2.21,118,120–122 RBC membrane properties in hereditary disorders have been mostly evaluated by ektacytometry,47,123–125 which does not provide direct measurements and is limited to descriptions of shifts in the DI curve vs osmolality relative to the control. Ektacytometry results (Figure 5 and Table II) suggest that hereditary disorders (HS,10,126 HE,10 SAO,10,127 and HSt10) cause a decrease in the deformability of the RBC membrane, shown by the shift in the pathological DI vs Osm curve relative to that of the control.

FIG. 5.

Microscopy imaging of RBCs (top panel) and ektacytometry curves, in which grey and black lines pertain to control and patient cells, respectively (bottom panel), for: (A) Hereditary spherocytosis. Black arrows indicate the typical spherocytic shape, red arrows indicate acanthocytes (RBCs with spiked membranes), and blue arrows indicate basophilic red cell due to the anemic state; (B) elliptocytic (red arrows) and ovalocytic red cells (blue arrows); (C) stomatocytic red cells (black arrows). Adapted from Ref. 10.

TABLE II.

Mechanical properties of RBCs affected by hereditary spherocytosis, elliptocytosis, ovalocytosis, and stomatocytosis.

| Control | HS | HE | SAO | HSt | Techniques | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shear elastic modulus (μN/m) | 5.4 ± 3.4 | 5.04 ± 1.32 | 6.5 ± 2.1 | … | … | Micropipette129–131 |

| Relaxation time constant (s) | 0.19 ± 0.086 | 0.086 ± 0.06 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | … | … | Micropipette129–131 |

| DImax | 0.45 ± 0.05 | 0.3 ± 0.27 | 0.65 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.05 | 0.51 | Ektacytometry 10,47,125–127,132 |

| Young's modulus (KPa) | 26 ± 7 | 43 ± 21 | … | … | … | AFM39 |

Decreasing in surface area are characterized by a decrease of DI max and by a general shifting of the curve in the direction of the increasing osmolality, in particular, DI min is found at higher osmolality values (Figure 5(A)). However, decreased values of DI max not always indicate reduced surface area. An increased membrane shear modulus tends to reduce the maximum DI, and, in general, a slight shift of the whole curve to lower osmolality is present (Figures 5(B) and 5(C)). Cynober et al.47 described the changes in membrane surface area, surface area-to-volume ratio, and cell volume of RBCs based on the osmotic profile in both non-splenectomized and splenectomized patients with HS; their study detected a decrease in membrane surface area in all of the studied patients and suggested that the percentage of microcytes may serve as a good indicator of disease severity.

The spectrin-dependent behaviour of the DI has also been studied,128 which showed that DImax (maximum osmotic profile as a function of osmolality) is associated with the spectrin content of cells, and that DImax decreases with the severity of spectrin deficiency. Waugh129–131 obtained similar results using micropipette experiments and suggested that spectrin deficiency is one of the causes of membrane abnormalities. Spectrin is regarded as the main energy-storing molecule of the RBC membrane and is responsible for elastic shear deformation. The shear modulus of the RBC membrane thus largely depends on the surface density of spectrin in the membrane. In the same studies, membrane shear modulus and viscoelastic time recovery constant were evaluated for HS and HE.

Membrane shear modulus was slightly smaller for HS and HE cells compared to the control, whereas viscoelastic recovery time constant values were similar to that of the control (Table II). These two parameters are available for HS and HE only, because SAO and HSt are very rare pathologies, and thus, it is more difficult to find donors.

In the past few years, AFM39 has been used in studies involving the mechanical properties of erythrocytes from patients with HS in terms of Young's modulus. This parameter was higher in HS erythrocytes compared to normal cells, indicating possible changes in the organization of the RBC cytoskeleton.

Currently, osmotic gradient ektacytometry is the best diagnostic reference technique for hereditary disorders. Flow cytometry has also been used but can often generate false positive results, which are often circumvented by microscopy analysis of cellular morphology. Thus, because microscopy analysis is considered as the most important step in the diagnosis of hereditary disorders, a novel system such as a microfluidic device that combines RBC image analysis and the quantification of membrane properties such as the three fundamental membrane moduli (the shear elastic modulus, the area expansion modulus, and the bending modulus) and the relaxation time constant could be a novel tool in the diagnosis of hereditary disorders and could help to establish the relationship between membrane defects and the clinical status of the patient. The initial steps have been conducted towards this goal through the application of a microfluidic-based method, the SICMA86,87 technology, that is able to measure the Elongation Index of individual cells in a heterogeneous population, allowing the recognition of subpopulations of pathological cells by the comparison with the healthy ones. A 30% reduction in RBC deformability has been observed in spherocytosis by using SICMA technology.86

V. METABOLIC DISORDERS

A metabolic disorder occurs when abnormal chemical reactions disrupt normal metabolism, which is the process that converts food to energy at the cellular level. Metabolic diseases affect the ability of a cell to perform essential biochemical reactions involving the transport and/or processing of proteins, carbohydrates, or lipids. The most common metabolic diseases include diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and obesity, which are recognized as multiplex risk factors for cardiovascular disease.133

A. Diabetes

Type II diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycaemia and results from either low insulin levels or insulin resistance. It is the most frequent cause of renal failure and legal blindness, and one of the major risk factors of cardiovascular diseases.134,135 Several studies have shown that diabetes can be associated with enhanced plasma and whole blood viscosity and abnormal RBC membrane architecture, in which the diabetic state can cause a reduced level of cell deformability, as well as complications such as microvascular disease and microangiopathy.136–139

It has been observed that RBC cytoplasmic viscosity largely depends on the physicochemical properties of haemoglobin140 such as glycosylation, whose increase is due to diabetic-related hyperglycaemia. Thus, altered membrane lipid-protein interactions and increased glycosylation could alter RBC membrane viscoelastic properties that contribute to diabetic progression.141–143 Abnormalities in the RBC membrane in diabetic patients involve an elongated shape with membrane folding around spontaneously formed fibrin fibres (Figures 6(A)) and a smooth membrane (Figure 6(B)).9

FIG. 6.

SEM images of diabetic RBCs: (A) RBC showing lengthened ultrastructure; (C) RBC showing smooth membrane (Scale = 1 μm). Adapted from Ref. 9.

In the 1970s and 1980s, filtration144–148 and micropipette139 experiments showed that diabetic RBCs present an impaired deformability,149 and that these take more time to recover their discoidal shape. On the other hand, rheoscope analysis115 did not detect any differences between control and diseased cells in terms of the time required for shape recovery.

La Celle150 and Sewchand et al.151 also did not observe any abnormalities in diabetic RBC deformability. More reliable and systematic measurements on RBC deformability were performed by Tsukada et al.83 by using a simple glass microfluidic device as a model for microvessels (Figures 3(B1) and 3(B2)). The classical RBC parachute shape in flow was characterized in terms of a DI (Deformability Index), which is defined as the ratio between cell length and width. The RBC DI of diabetic patients was smaller than that of healthy donors, thus indicating an impaired deformability. Recently, Brown et al.152 used a filtration technique to describe the DI as the rate of filtration of a dilute suspension of RBCs through membranes with straight channels under a constant negative pressure, compared to the rate of filtration of an equal volume of buffer. Their study detected impairments in RBC deformability in diabetic patients. In the last decade, a disposable ektacytometer153,154 equipped with a laser diffraction system and slit rheometer has been developed to measure RBC deformability in terms of DI (referred to as EI in Refs. 153 and 154). Also, in this case, an impaired RBC deformability was observed in diabetic patients compared to non-diabetic controls.

Despite the incidence of diabetes and the extent of impairment in RBC membrane properties that may affect blood flow in microcirculation and tissue oxygen supply in vascular diabetic complications, only a few reports have described quantitative measurements of RBC deformability in diabetes.

One of the most important consequences of impaired RBC deformability is the impaired perfusion at the tissue level, which is a complication of diabetes mellitus.155,156 The development of high-throughput techniques to obtain quantitative data on viscoelastic properties of RBC membranes could be important to delineate the correlation of impaired RBC deformability with the complications of diabetes, such as microvascular disease, microangiopathy, and nephropathy, which are not well understood at the moment. Moreover, such high-throughput techniques could be used to test the effect of drugs for reduce whole blood viscosity at the microcirculation level, since it is significantly enhanced in diabetes.135

B. Hypercholesterolemia

Hypercholesterolemia is a metabolic disorder characterized by high levels of cholesterol in the blood, which is transported in the plasma as lipoproteins. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol is recognized as a risk factor of atherosclerosis, hypertension, and coronary heart disease.157–159 The direct effects of cholesterol on blood flow include growth of atherosclerotic plaques that reduce the lumen of coronary arteries, as well as blunted endothelium-dependent vasodilation at the coronary microcirculation level that leads to an impairment of myocardial perfusion. Indirect effects of hypercholesterolemia involve blood rheology; in fact, a high level of cholesterol may affect whole blood viscosity, platelet activation, and RBC deformability, leading again to impaired coronary circulation.160 By applying the laser diffractometric method,160,161 the responses of deformed RBCs to shear stress at increased flow speeds have been measured in hypercholesterolemic patients, which have revealed a decrease in RBC deformability. Unfortunately, this work, as well as filtration-based studies,112 did not provide a direct measure of the viscoelastic constants, but the output was instead based on some parameters that were related to RBC deformability. On the other hand, micropipette experiments162 provided measurements of the intrinsic viscoelastic properties of both cholesterol-enriched and cholesterol-depleted RBCs. The former showed a flat, pancake-shaped RBC, as previously observed by Cooper et al.,163 with an irregular contour (Figure 7) and a diameter bigger than that of the controls. The latter showed a smaller diameter than the control cells, and some cells presented a stomatocyte-like shape.

FIG. 7.

SEM images of cholesterol-enriched RBCs. Adapted from Ref. 163.

Thus, by using this technique, any significant alteration in the shear elastic modulus and surface viscosity has been considered as a consequence of the changes in the membrane cholesterol content. EI164 as measured by using a Rheodyn (described in Sec. III) has been measured in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. The results showed that patients had lower EI values than the controls. Recently, Forsyth et al.165 utilized a microfluidic flow-focusing device to examine the relationship between cholesterol and ATP release from RBCs and showed that changes in membrane cholesterol can cause alterations in RBC deformability and, thereby, disruptions in ATP release. Because of the limited and inconsistent reports regarding hypercholesterolemic RBC membrane properties, further work is needed to establish the significance of RBC membrane alterations in this disease, as well as on blood flow at the coronary microcirculation level.

C. Obesity

Obesity is a widespread metabolic disorder associated with several cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes, arterial hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. Because of the presence of different degrees of obesity and diverse methodologies, contradictory results have been published regarding RBC deformability in obese patients.166–169 Some studies describe an increase in membrane cholesterol/phospholipid ratio, whereas only one study involved patients with morbid obesity.170–173 A recent study focused on the evaluation of RBC deformability in a group of patients with severe and morbid obesity without other cardiovascular risk factors.174 RBC DI was measured using laser diffractometric techniques in terms of the EI, although it seems that RBC deformability does not decrease in obese patients without other concomitant cardiovascular risk factors. Thus, for obesity, as well as for hypercholesterolemia, there is a need to further investigate the correlation between obesity and alterations in the RBC membrane.

VI. ATP-INDUCED MEMBRANE CHANGES

Several studies175–177 have shown that the shape of RBCs is influenced by metabolic activities that regulate the intracellular concentration of ATP (adenosine triphosphate, an energy supplying molecule)178 based on the fact that some sites of the RBC skeleton, such as the spectrin network, may absorb chemical energy from its contact with ATP.16 The mechanistic links involved in ATP release induced by RBC deformation have been also recently reviewed.179 Modifications in RBC shape could be related to changes in ATP levels, and different experimental techniques have been proposed to clarify the relationship between RBC flow dynamics and ATP.104,114,165,178,180,181 Filtration experiments were conducted to determine the effects of ATP depletion on membrane deformability, which showed that the RBC membrane properties were influenced by the metabolic state of the cell, which in turn is regulated by ATP.180 Simulation of a hemispherical deformation of the RBC membrane using a 3-μm micropipette has shown that ATP-depleted cells have a decreased level of deformability. The ATP-depleted cells may be unable to pass through narrow capillaries in the microcirculation and spleen, which contain 3-μm pores. By microscopic observation, an increase in RBC rigidity has been observed in ATP-depleted blood, suggesting the key role of ATP in the maintenance of RBC membrane properties.180 Micropipette experiments provided data on the shear elastic modulus, the area compressibility modulus, and the surface shear viscosity for ATP-depleted RBC membranes;104 however, no significant differences between fresh and ATP-depleted RBCs have been observed. No dependence on ATP has been also observed by measuring the change in RBC membrane fluctuations combining microscopy and image processing.63

Recently, optical tweezers114 have been used to study the membrane-cytoskeleton interactions in terms of RBC membrane fluctuations; an increase in the RBC membrane bending modulus has been identified as the mechanism responsible for the reduction in membrane fluctuations. However, few years later, fluctuations analysis and optical traps94 gave opposite results. Quantitative evidence obtained using full-field laser interferometry techniques71 shows that ATP facilitates the dynamic fluctuations in the RBC membrane. One of the factors influencing the structure and the mechanical integrity of the spectrin network and the overall shape of the RBC is the remodelling of the coupled membranes powered by ATP.71,72

Despite the number of works present in the literature, the dependence of RBC deformation on ATP is still controversial. This is probably due to the complex cell mechanics and, consequently, to the cell deformation protocol. Indeed, although information on the mechanical properties of RBCs in relation to ATP are essential in understanding specific medical conditions such as hypertension and efficacy of blood transfusions, a physiologically relevant regime of deformation is not completely understood.

VII. OXIDATIVE STRESS

Under physiological conditions, RBCs are able to defend against the continuous exposure to oxidative stress, by the intervention of antioxidant molecules that inactivate reactive oxygen molecules and enzymes that convert toxic compounds in forms that can be excreted by cells.182 However, abnormal response of cells to oxidative stress can cause toxic effects through the production of peroxides and free radicals, leading to damages in RBC skeleton, in normal mechanisms of cellular signaling, in membrane fluidity, and, consequently, it can affect the passage through the microcirculatory network. Thus, impaired RBCs deformability caused by the damages to the structural components of the membrane worsen some pathological situations related to high oxidative stress, such as diabetes, and to microcirculation, such as heart failure and myocardial infarction.183,184

Several investigators measured impaired RBC deformability in presence of oxidative stress by using techniques such as ektacytometry.185–190 To overcome the classical limitations related to ekracytometry measurements (i.e., poor accuracy and quantification of the amount of rigid cells in the sample), studies on single cell response to oxidative stress have been carried out in the last years. By the analysis of the membrane thermal fluctuation spectrum, mechanical properties of RBC, such as bending and elastic moduli, have been evaluated, reporting changes in the elastic constant of RBCs exposed to oxidative stress in vitro.191

More recently, a microfluidic approach has been proposed, demonstrating the presence of RBCs damaged by oxidative stress in terms of cortical tension,192 with the aim to discriminate between good stored and bad stored RBCs for transfusion, an important issue of clinical interest. Thus, although this approach does not give information about the relevant membrane parameters, such as bending and elastic moduli, relaxation time constant, and surface viscosity, it provides a cost-effective, high throughput, and reproducible method for measuring RBC deformability in presence of oxidative stress, and opens the way for further microfluidic studies.

VIII. PAROXYSMAL NOCTURNAL HEMOGLOBINURIA

PNH is a rare (1–2 new cases per million per year and affects less than 200 000 people in the US population, according to the Office of Rare Diseases of the National Institutes of Health) acquired clonal disorder caused by a mutation in the X-linked phosphatidylinositol glycan class A (PIG-A) gene that leads to absence of protective proteins on the RBC membrane.193 PNH is characterized by complement-mediated haemolysis, venous thrombosis, and bone marrow suppression.194,195 PNH erythrocytes are quite vulnerable to complement-mediated lysis because of a reduction or complete absence of two complement regulators, CD55 and CD59, both of which are GPI-anchored.195,196 Despite the importance of membrane viscoelastic properties in the survival of RBCs,129,180,197 only one study, to my knowledge, has examined the RBC membrane properties in PNH. Smith12 utilized micropipette techniques in measuring the elastic modulus, viscosity, and time constant of RBCs affected by PNH. The mechanical properties of abnormal RBCs are impaired compared to normal cells, as shown in Table III.

TABLE III.

Mechanical properties of PNH erythrocytes.

IX. CONCLUDING REMARKS

In this article, mechanical properties of both healthy and diseased RBCs have been reviewed, focusing on the role of impaired RBC deformability in various pathologies such as hereditary disorders (spherocytosis, elliptocytosis, ovalocytosis, stomatocytosis), metabolic disorders (diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, obesity), ATP-induced membrane changes, and Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. In vitro experimental models that are commonly used to measure RBC deformability have also been described. RBC membrane properties in hereditary disorders have been mostly measured by ektacytometry,47,123–125 a laser diffraction-based method that does not provide direct measurements and is limited to describing membrane properties in terms of shifts in the DI curve vs osmolality from the control. Thus, based on these measures, an impaired RBC deformability has been characterized. The case is different with metabolic disorders because reports describing this association are limited and traditional measurement techniques have been used in the few published reports on this matter, which may have contributed to the generation of conflicting results. In some cases, as for example, for PNH, only one study12 has examined the RBC membrane properties, finding an impaired cell deformability.

The role of RBC deformability has thus been established in only a few disorders.

One major disadvantage of the experimental methods used for the evaluation of RBC biomechanical properties is that the stress imposed on the cells is far from the one actually experienced during in microcirculation. This fact may distort the results, which in turn may decrease the clinical relevance of the study. Although enormous progress has been made, our understanding of the role of RBCs deformability in such diseases is still far from complete. Despite the number of complications generated from a decrease in RBC deformability such as impaired blood flow in vascular complications of the diseases, particularly at the microcirculation level, a quantitative knowledge of RBC membrane properties is needed.

Therefore, it is necessary to develop state-of-the-art dynamic experimental models for elucidating the significance of RBC membrane alterations in pathological conditions and the role that such alterations play in the microvasculature flow dynamics by using well controlled and physiologically relevant mechanical environments. Since many traditional biochemical and biological assays such as flow cytometry,198–201 DNA extraction,202,203 and polymerase chain reaction,203,204 have already been transferred onto integrated microfluidic devices to provide multi-parameter information to target cells, it is possible to develop a novel high-throughput system, based on microfluidics techniques, for the measurement of RBC membrane properties. Such a system should allow high-speed/high-magnification observations of the flow of RBCs in model systems that well represent the human microvasculature. Recent reports have focused on the healthy cell65 and on a few pathologies, i.e., malaria205–207 and sickle cell anaemia.208,209 On the other hand, data are limited related to the biomechanical properties of RBCs in common pathologies such as hereditary and metabolic disorders that involve severe complications in blood circulation at the microvasculature level due to impaired RBCs deformability. Thus, additional experimental studies are needed to extensively examine the mechanical properties of RBCs in various diseases to establish the correlation between RBC mechanical properties and patients clinical status.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding from the Italian Ministry of University and Research (PRIN Program 2010–2011, Project No. 20109PLMH2), and from the Regione Campania (MICROEMA Project, 220 APQ-RT02 2008) is acknowledged. This study is related to the activity of the European network action COST MP1106 “Smart and green interfaces—from single bubbles and drops to industrial, environmental, and biomedical applications.” The author thanks Professor S. Guido for useful discussions and A. Perazzo for helping in reference collection.

References

- 1.Wang C. and Popel A., “ Effect of red blood cell shape on oxygen transport in capillaries,” Math. Biosci. 116(1), 89–110 (1993). 10.1016/0025-5564(93)90062-F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guido S. and Tomaiuolo G., “ Microconfined flow behavior of red blood cells in vitro,” C. R. Phys. 10, 751–763 (2009). 10.1016/j.crhy.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson P. C., “ Overview of the microcirculation,” Microcirculation ( Academic Press, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng Y., Nguyen J., Wei Y., and Sun Y., “ Recent advances in microfluidic techniques for single-cell biophysical characterization,” Lab Chip 13(13), 2464–2483 (2013). 10.1039/c3lc50355k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shattil S., Furie B., Cohen H., Silverstein L., Glave P., and Strauss M., Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice ( Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hosseini S. M. and Feng J. J., “ How malaria parasites reduce the deformability of infected red blood cells,” Biophys. J. 103(1), 1–10 (2012). 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu T. and Feng J. J., “ Simulation of malaria-infected red blood cells in microfluidic channels: Passage and blockage,” Biomicrofluidics 7(4), 044115 (2013). 10.1063/1.4817959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barabino G. A., Platt M. O., and Kaul D. K., “ Sickle cell biomechanics,” Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 12, 345–367 (2010). 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-070909-105339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buys A. V., Van Rooy M.-J., Soma P., Van Papendorp D., Lipinski B., and Pretorius E., “ Changes in red blood cell membrane structure in type 2 diabetes: A scanning electron and atomic force microscopy study,” Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 12, 25 (2013). 10.1186/1475-2840-12-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa L. Da, Galimand J., Fenneteau O., and Mohandas N., “ Hereditary spherocytosis, elliptocytosis, and other red cell membrane disorders,” Blood Rev. 27(4), 167–178 (2013). 10.1016/j.blre.2013.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vayá A., Rivera L., Espriella R. de laet al. , “ Red blood cell distribution width and erythrocyte deformability in patients with acute myocardial infarction,” Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. (published online 2013). 10.3233/CH-131751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith B., “ Abnormal erythrocyte fragmentation and membrane deformability in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria,” Am. J. Hematol. 20(4), 337–343 (1985). 10.1002/ajh.2830200404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McHedlishvili G. and Maeda N., “ Blood flow structure related to red cell flow: Determinant of blood fluidity in narrow microvessels,” Jpn. J. Physiol. 51(1), 19–30 (2001). 10.2170/jjphysiol.51.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohandas N. and Gallagher P. G., “ Red cell membrane: Past, present, and future,” Blood 112(10), 3939–3948 (2008). 10.1182/blood-2008-07-161166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fung Y. C., Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues ( Springer-Verlag, New York, 1993). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diez-Silva M., Dao M., Han J., Lim C.-T., and Suresh S., “ Shape and biomechanical characteristics of human red blood cells in health and disease,” Mrs. Bull. 35(5), 382–388 (2010). 10.1557/mrs2010.571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suresh S., Spatz J., Mills J. P., Micoulet A.et al. , “ Connections between single-cell biomechanics and human disease states: Gastrointestinal cancer and malaria,” Acta Biomater. 1, 15–30 (2005) 10.1016/j.actbio.2004.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee G. Y. H. and Lim C. T., “ Biomechanics approaches to studying human diseases,” Trends Biotechnol. 25(3), 111–118 (2007). 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rees D. C., Williams T. N., and Gladwin M. T., “ Sickle-cell disease,” Lancet 376(9757), 2018–2031 (2010). 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61029-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dondorp A. M., Kager P. A., Vreeken J., and White N. J., “ Abnormal blood flow and red blood cell deformability in severe malaria,” Parasitol. Today 16(6), 228–232 (2000). 10.1016/S0169-4758(00)01666-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suresh S., “ Mechanical response of human red blood cells in health and disease: Some structure-property-function relationships,” J. Mater. Res. 21(8), 1871–1877 (2006). 10.1557/jmr.2006.0260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canham P. B. and Burton A. C., “ Distribution of size and shape in populations of normal human red cells,” Circ. Res. 22(3), 405–422 (1968). 10.1161/01.RES.22.3.405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chasis J. and Shohet S., “ Red cell biochemical anatomy and membrane properties,” Annu. Rev. Physiol. 49, 237–248 (1987). 10.1146/annurev.ph.49.030187.001321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pretorius E., “ The adaptability of red blood cells,” Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 12, 63 (2013). 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Girasole M., Pompeo G., Cricenti A.et al. , “ Roughness of the plasma membrane as an independent morphological parameter to study RBCs: A quantitative atomic force microscopy investigation,” Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 1768(5), 1268–1276 (2007). 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Girasole M., Dinarelli S., and Boumis G., “ Structure and function in native and pathological erythrocytes: A quantitative view from the nanoscale,” Micron 43(12), 1273–1286 (2012). 10.1016/j.micron.2012.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bester J., Buys A. V., Lipinski B., Kell D. B., and Pretorius E., “ High ferritin levels have major effects on the morphology of erythrocytes in Alzheimer's disease,” Front. Aging Neurosci. 5, 88 (2013) 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chien S., “ Principles and techniques for assessing erythrocyte deformability,” in Red Cell Rheology, edited by Bessis M., Shohet S., and Mohandas N. ( Springer; Berlin Heidelberg, 1978), pp. 71–99 [Google Scholar]

- 29.LaCelle P. L., “ Alteration of membrane deformability in hemolytic anemias,” Semin. Hematol. 7(4), 355–371 (1970). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meiselman H. J., “ Morphological determinants of red cell deformability,” Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 41, 27–34 (1981) 10.3109/00365518109097426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohandas N., Clark M. R., Jacobs M. S., and Shohet S. B., “ Analysis of factors regulating erythrocyte deformability,” J. Clin. Invest. 66(3), 563–573 (1980). 10.1172/JCI109888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evans E. A., Waugh R., and Melnik L., “ Elastic area compressibility modulus of red cell membrane,” Biophys. J. 16(6), 585–595 (1976). 10.1016/S0006-3495(76)85713-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evans E. A., “ Bending elastic modulus of red blood cell membrane derived from buckling instability in micropipet aspiration tests,” Biophys. J. 43(1), 27–30 (1983). 10.1016/S0006-3495(83)84319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hochmuth R. and Waugh R., “ Erythrocyte membrane elasticity and viscosity,” Annu. Rev. Physiol. 49, 209–219 (1987). 10.1146/annurev.ph.49.030187.001233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomaiuolo G. and Guido S., “ Start-up shape dynamics of red blood cells in microcapillary flow,” Microvasc. Res. 82(1), 35–41 (2011). 10.1016/j.mvr.2011.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hochmuth R., Worthy P., and Evans E., “ Red cell extensional recovery and the determination of membrane viscosity,” Biophys. J. 26(1), 101–114 (1979). 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85238-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bazzoni G. and Rasia M., “ Effects of an amphipathic drug on the rheological properties of the cell membrane,” Blood Cells, Mol., Dis. 24(4), 552–559 (1998). 10.1006/bcmd.1998.0219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maciaszek J. L., Andemariam B., and Lykotrafitis G., “ Microelasticity of red blood cells in sickle cell disease,” J. Strain Anal. Eng. Des. 46(5), 368–379 (2011). 10.1177/0309324711398809 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dulinska I., Targosz M., Strojny W.et al. , “ Stiffness of normal and pathological erythrocytes studied by means of atomic force microscopy,” J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 66(1–3), 1–11 (2006). 10.1016/j.jbbm.2005.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skalak R., Tozeren A., Zarda R. P., and Chien S., “ Strain energy function of red blood cell membranes,” Biophys. J. 13(3), 245–264 (1973). 10.1016/S0006-3495(73)85983-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dintenfass L., “ Internal viscosity of the red cell and a blood viscosity equation,” Nature 219, 956–958 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bessis M., Mohandas N., and Feo C., “ Automated ektacytometry: A new method of measuring red cell deformability and red cell indices,” Blood Cells 6(3), 315–327 (1979). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shin S., Ku Y. H., Park M. S., Moon S. Y., Jang J. H., and Suh J. S., “ Laser-diffraction slit rheometer to measure red blood cell deformability,” Rev. Sci. Instrum. 75(2), 559–561 (2004). 10.1063/1.1641162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sutera S., Seshadri V., Croce P., and Hochmuth R., “ Capillary blood flow. II. Deformable model cells in tube flow,” Microvasc. Res. 2(4), 420–433 (1970). 10.1016/0026-2862(70)90035-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sutera S. P., Gardner R. A., Boylan C. W.et al. , “ Age-related changes in deformability of human erythrocytes,” Blood. 65(2), 275–282 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmid-Schönbein H., Gosen J. V., Heinich L., Klose H. J., and Volger E., “ A counter-rotating ‘rheoscope chamber’ for the study of the microrheology of blood cell aggregation by microscopic observation and microphotometry,” Microvasc. Res. 6(3), 366–376 (1973). 10.1016/0026-2862(73)90086-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cynober T., Mohandas N., and Tchernia G., “ Red cell abnormalities in hereditary spherocytosis: Relevance to diagnosis and understanding of the variable expression of clinical severity,” J. Lab. Clin. Med. 128(3), 259–269 (1996). 10.1016/S0022-2143(96)90027-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baskurt O. K., Hardeman M. R., Uyuklu M., Ulker P., Cengiz M., Nemeth N., Shin S., Alexy T., and Meiselman H. J., “ Parameterization of red blood cell elongation index – Shear stress curves obtained by ektacytometry,” Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 69(7), 777–788 (2009). 10.3109/00365510903266069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Evans E., “ New membrane concept applied to the analysis of fluid shear- and micropipette-deformed red blood cells,” Biophys. J. 13(9), 941–954 (1973). 10.1016/S0006-3495(73)86036-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Engstrom K. G. and Meiselman H. J., “ Analysis of red blood cell membrane area and volume regulation using micropipette aspiration and perfusion,” Biorheology 32, 115–116 (1995). 10.1016/0006-355X(95)91960-B [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hochmuth R. M., “ Micropipette aspiration of living cells,” J. Biomech. 33, 15–22 (2000). 10.1016/S0021-9290(99)00175-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hénon S., Lenormand G., Richert A., and Gallet F., “ A new determination of the shear modulus of the human erythrocyte membrane using optical tweezers,” Biophys. J. 76(2), 1145–1151 (1999). 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77279-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mills J., Qie L., Dao M., Lim C., and Suresh S., “ Nonlinear elastic and viscoelastic deformation of the human red blood cell with optical tweezers,” Mech. Chem. Biosyst. 1(3), 169–180 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suresh S., “ Biomechanics and biophysics of cancer cells,” Acta Mater. 55(12), 3989–4014 (2007). 10.1016/j.actamat.2007.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Luca A., Rusciano G., Ciancia R.et al. , “ Spectroscopical and mechanical characterization of normal and thalassemic red blood cells by Raman tweezers,” Opt Express. 16(11), 7943–7957 (2008). 10.1364/OE.16.007943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang H. and Liu K. K., “ Optical tweezers for single cells,” J. R. Soc. Interface 5(24), 671–690 (2008). 10.1038/nature04268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brandão M. M., Fontes A., Barjas-Castro M. L., Barbosa L. C., Costa F. F., Cesar C. L., and Saad S. T. O., “ Optical tweezers for measuring red blood cell elasticity: Application to the study of drug response in sickle cell disease,” Eur. J. Haematol. 70(4), 207–211 (2003). 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2003.00027.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dao M., Lim C. T., and Suresh S., “ Mechanics of the human red blood cell deformed by optical tweezers,” J. Mech. Phys. Solids 51(11–12), 2259–2280 (2003). 10.1016/j.jmps.2003.09.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoon Y.-Z., Hong H., Brown A.et al. , “ Flickering analysis of erythrocyte mechanical properties: Dependence on oxygenation level, cell shape, and hydration level,” Biophys. J. 97(6), 1606–1615 (2009). 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.06.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brochard F. and Lennon J. F., “ Frequency spectrum of the flicker phenomenon in erythrocytes,” J. Physique. 36(11), 1035–1047 (1975). 10.1051/jphys:0197500360110103500 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zilker A., Ziegler M., and Sackmann E., “ Spectral analysis of erythrocyte flickering in the 0.3-4- μm−1 regime by microinterferometry combined with fast image processing,” Phys. Rev. A 46(12), 7998–8001 (1992). 10.1103/PhysRevA.46.7998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Popescu G., Ikeda T., Goda K.et al. , “ Optical measurement of cell membrane tension,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 97(21), 218101 (2006). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.218101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Evans J., Gratzer W., Mohandas N., Parker K., and Sleep J., “ Fluctuations of the red blood cell membrane: Relation to mechanical properties and lack of ATP dependence,” Biophys. J. 94(10), 4134–4144 (2008). 10.1529/biophysj.107.117952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuznetsova T. G., Starodubtseva M. N., Yegorenkov N. I., Chizhik S. A., and Zhdanov R. I., “ Atomic force microscopy probing of cell elasticity,” Micron. 38(8), 824–833 (2007). 10.1016/j.micron.2007.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tomaiuolo G., Barra M., Preziosi V., Cassinese A., Rotoli B., and Guido S., “ Microfluidics analysis of red blood cell membrane viscoelasticity,” Lab Chip. 11(3), 449–454 (2011). 10.1039/c0lc00348d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abkarian M., Faivre M., Horton R., Smistrup K., Best-Popescu C., and Stone H., “ Cellular-scale hydrodynamics,” Biomed. Mater. 3(3), 034011 (2008). 10.1088/1748-6041/3/3/034011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mishra P., Hill M., and Glynne-Jones P., “ Deformation of red blood cells using acoustic radiation forces,” Biomicrofluidics 8(3), 034109 (2014). 10.1063/1.4882777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jay A. W., “ Geometry of the human erythrocyte. I. Effect of albumin on cell geometry,” Biophys J. 15(3), 205–222 (1975). 10.1016/S0006-3495(75)85812-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bremmell K. E., Evans A., and Prestidge C. A., “ Deformation and nano-rheology of red blood cells: An AFM investigation,” Colloids Surfaces B. 50(1), 43–48 (2006). 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu Y., Hu Y., Cai J.et al. , “ Time-dependent surface adhesive force and morphology of RBC measured by AFM,” Micron. 40(3), 359–364 (2009). 10.1016/j.micron.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Park Y., Best C. A., Auth T.et al. , “ Metabolic remodeling of the human red blood cell membrane,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107(4), 1289–1294 (2010). 10.1073/pnas.0910785107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li J., Lykotrafitis G., Dao M., and Suresh S., “ Cytoskeletal dynamics of human erythrocyte,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104(12), 4937–4942 (2007). 10.1073/pnas.0700257104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sackmann E. K., Fulton A. L., and Beebe D. J., “ The present and future role of microfluidics in biomedical research,” Nature 507(7491), 181–189 (2014). 10.1038/nature13118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hou H. W., Gan H. Y., Bhagat A. A. S., Li L. D., Lim C. T., and Han J., “ A microfluidics approach towards high-throughput pathogen removal from blood using margination,” Biomicrofluidics 6(2), 024115 (2012). 10.1063/1.4710992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zheng Y., Chen J., Cui T., Shehata N., Wang C., and Sun Y., “ Characterization of red blood cell deformability change during blood storage,” Lab Chip 14(3), 577–583 (2014). 10.1039/c3lc51151k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Whitesides G. M., “ The origins and the future of microfluidics,” Nature 442(7101), 368–373 (2006). 10.1038/nature05058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gong M. M., Macdonald B. D., Nguyen T. Vu, Van Nguyen K., and Sinton D., “ Field tested milliliter-scale blood filtration device for point-of-care applications,” Biomicrofluidics 7(4), 44111 (2013). 10.1063/1.4817792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sherwood J. M., Dusting J., Kaliviotis E., and Balabani S., “ The effect of red blood cell aggregation on velocity and cell-depleted layer characteristics of blood in a bifurcating microchannel,” Biomicrofluidics 6(2), 024119 (2012). 10.1063/1.4717755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tomaiuolo G., Preziosi V., Simeone M.et al. , “ A methodology to study the deformability of red blood cells flowing in microcapillaries in vitro,” Ann. Ist. Super Sanita. 43(2), 186–192 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tomaiuolo G., Simeone M., Martinelli V., Rotoli B., and Guido S., “ Red blood cell deformability in microconfined shear flow,” Soft Matter. 5, 3736–3740 (2009). 10.1039/b904584h [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tomaiuolo G., Rossi D., Caserta S., Cesarelli M., and Guido S., “ Comparison of two flow-based imaging methods to measure individual red blood cell area and volume,” Cytometry, Part A 81(12), 1040–1047 (2012). 10.1002/cyto.a.22215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tomaiuolo G., Lanotte L., Ghigliotti G., Misbah C., and Guido S., “ Red blood cell clustering in Poiseuille microcapillary flow,” Phys. Fluids. 24(5), 051903–051908 (2012). 10.1063/1.4721811 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tsukada K., Sekizuka E., Oshio C., and Minamitani H., “ Direct measurement of erythrocyte deformability in diabetes mellitus with a transparent microchannel capillary model and high-speed video camera system,” Microvasc. Res. 61(3), 231–239 (2001). 10.1006/mvre.2001.2307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lanotte L., Tomaiuolo G., Misbah C., Bureau L., and Guido S., “ Red blood cell dynamics in polymer brush-coated microcapillaries: A model of endothelial glycocalyx in vitro,” Biomicrofluidics 8(1), 014104 (2014). 10.1063/1.4863723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Du E., Ha S., Diez-Silva M., Dao M., Suresh S., and Chandrakasan A. P., “ Electric impedance microflow cytometry for characterization of cell disease states,” Lab Chip 13(19), 3903–3909 (2013). 10.1039/c3lc50540e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Doh I., Lee W. C., Cho Y.-H., Pisano A. P., and Kuypers F. A., “ Deformation measurement of individual cells in large populations using a single-cell microchamber array chip,” Appl. Phys. Lett. 100(17), 173702 (2012). 10.1063/1.4704923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lee W. C., Rigante S., Pisano A. P., and Kuypers F. A., “ Large-scale arrays of picolitre chambers for single-cell analysis of large cell populations,” Lab Chip. 10(21), 2952–2958 (2010). 10.1039/c0lc00139b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liao S.-H., Chang C.-Y., and Chang H.-C., “ A capillary dielectrophoretic chip for real-time blood cell separation from a drop of whole blood,” Biomicrofluidics. 7(2), 024110 (2013). 10.1063/1.4802269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shevkoplyas S., Gifford S., Yoshida T., and Bitensky M., “ Prototype of an in vitro model of the microcirculation,” Microvasc. Res. 65(2), 132–136 (2003). 10.1016/S0026-2862(02)00034-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Montagnana M., Cervellin G., Meschi T., and Lippi G., “ The role of red blood cell distribution width in cardiovascular and thrombotic disorders,” Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 50, 635 (2012) 10.1515/cclm.2011.831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sutton N., Tracey M. C., Johnston I. D., Greenaway R. S., and Rampling M. W., “ A novel instrument for studying the flow behaviour of erythrocytes through microchannels simulating human blood capillaries,” Microvasc. Res. 53(3), 272–281 (1997). 10.1006/mvre.1997.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schonbrun E., Malka R., Caprio G., Schaak D., and Higgins J. M., “ Quantitative absorption cytometry for measuring red blood cell hemoglobin mass and volume,” Cytometry, Part A. 85(4), 332–338 (2014). 10.1002/cyto.a.22450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yoon Y.-Z., Kotar J., Yoon G., and Cicuta P., “ The nonlinear mechanical response of the red blood cell,” Phys. Biol. 5(3), 036007 (2008). 10.1088/1478-3975/5/3/036007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yoon Y. Z., Kotar J., Brown A. T., and Cicuta P., “ Red blood cell dynamics: From spontaneous fluctuations to non-linear response,” Soft Matter. 7(5), 2042–2051 (2011). 10.1039/c0sm01117g [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Waugh R. E., Narla M., Jackson C. W., Mueller T. J., Suzuki T., and Dale G. L., “ Rheologic properties of senescent erythrocytes: Loss of surface area and volume with red blood cell age,” Blood 79(5), 1351–1358 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Linderkamp O., Wu P. Y., and Meiselman H. J., “ Geometry of neonatal and adult red blood cells,” Pediatr. Res. 17(4), 250–253 (1983). 10.1203/00006450-198304000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Linderkamp O., Friederichs E., and Meiselman H. J., “ Mechanical and geometrical properties of density-separated neonatal and adult erythrocytes,” Pediatr. Res. 34(5), 688–693 (1993). 10.1203/00006450-199311000-00024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Linderkamp O. and Meiselman H. J., “ Geometric, osmotic, and membrane mechanical properties of density- separated human red cells,” Blood 59(6), 1121–1127 (1982). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nash G. B. and Meiselman H. J., “ Red cell and ghost viscoelasticity. Effects of hemoglobin concentration and in vivo aging,” Biophys J. 43(1), 63–73 (1983). 10.1016/S0006-3495(83)84324-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Evans E. and Fung Y., “ Improved measurements of the erythrocyte geometry,” Microvasc. Res. 4(4), 335–347 (1972). 10.1016/0026-2862(72)90069-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Secomb T. and Hsu R., “ Analysis of red blood cell motion through cylindrical micropores: Effects of cell properties,” Biophys J. 71(2), 1095–1101 (1996). 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79311-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Haik Y., Pai V. N., and Chen C. J., “ Apparent viscosity of human blood in a high static magnetic field,” J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 225(1–2), 180–186 (2001). 10.1016/S0304-8853(00)01249-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Evans E. and Hochmuth R., “ Membrane viscoelasticity,” Biophys. J. 16(1), 1–11 (1976). 10.1016/S0006-3495(76)85658-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Meiselman H. J., Evans E. A., and Hochmuth R. M., “ Membrane mechanical properties of ATP-depleted human erythrocytes,” Blood. 52(3), 499–504 (1978). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hochmuth R. M., Buxbaum K. L., and Evans E. A., “ Temperature dependence of the viscoelastic recovery of red cell membrane,” Biophys. J. 29(1), 177–182 (1980). 10.1016/S0006-3495(80)85124-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lee J. C. and Discher D. E., “ Deformation-enhanced fluctuations in the red cell skeleton with theoretical relations to elasticity, connectivity, and spectrin unfolding,” Biophys. J. 81, 3178–3192 (2001) 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75954-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lenormand G., Hénon S., Richert A., Siméon J., and Gallet F., “ Direct measurement of the area expansion and shear moduli of the human red blood cell membrane skeleton,” Biophys. J. 81(1), 43–56 (2001). 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75678-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hwang W. C. and Waugh R. E., “ Energy of dissociation of lipid bilayer from the membrane skeleton of red blood cells,” Biophys J. 72(6), 2669–2678 (1997). 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78910-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Strey H., Peterson M., and Sackmann E., “ Measurement of erythrocyte membrane elasticity by flicker eigenmode decomposition,” Biophys. J. 69(2), 478–488 (1995). 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79921-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zilker A., Engelhardt H., and Sackmann E., “ Dynamic reflection interference contrast (RIC-) microscopy: A new method to study surface excitations of cells and to measure membrane bending elastic moduli,” J. Phys. (France) 48(12), 2139–2151 (1987). 10.1051/jphys:0198700480120213900 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Scheffer L., Bitler A., Ben-Jacob E., and Korenstein R., “ Atomic force pulling: probing the local elasticity of the cell membrane,” Eur Biophys J. 30(2), 83–90 (2001). 10.1007/s002490000122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zeman K., Engelhard H., and Sackmann E., “ Bending undulations and elasticity of the erythrocyte membrane: Effects of cell shape and membrane organization,” Eur. Biophys. J. 18(4), 203–219 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bronkhorst P., Streekstra G., Grimbergen J., Nijhof E., Sixma J., and Brakenhoff G., “ A new method to study shape recovery of red blood cells using multiple optical trapping,” Biophys. J. 69(5), 1666–1673 (1995). 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80084-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Betz T., Lenz M., Joanny J.-F., and Sykes C., “ ATP-dependent mechanics of red blood cells,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106(36), 15320–15325 (2009). 10.1073/pnas.0904614106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Williamson J. R., Gardner R. A., Boylan C. W.et al. , “ Microrheologic investigation of erythrocyte deformability in diabetes mellitus,” Blood 65(2), 283–288 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Waugh R. E. and Evans E. A., “ Thermoelasticity of red blood cell membranes,” Biophys. J. 26, 115–131 (1979). 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85239-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gallagher P. G., “ Red cell membrane disorders,” Hematology. 2005(1), 13–18 10.1182/asheducation-2005.1.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.An X. and Mohandas N., “ Disorders of red cell membrane,” British J. Haematology 141(3), 367–375 (2008). 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07091.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Iolascon A., Avvisati R. A., and Piscopo C., “ Hereditary spherocytosis,” Transfus. Clin Biol. 17(3), 138–142 (2010). 10.1016/j.tracli.2010.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gallagher P. G. and Forget B. G., “ Hematologically important mutations: Spectrin and ankyrin variants in hereditary spherocytosis,” Blood Cells, Mol., Dis. 24(4), 539–543 (1998). 10.1006/bcmd.1998.0217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Perrotta S., Gallagher P. G., and Mohandas N., “ Hereditary spherocytosis,” Lancet 372(9647), 1411–1426 (2008). 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61588-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Agre P., Orringer E. P., Chui D. H., and Bennett V., “ A molecular defect in two families with hemolytic poikilocytic anemia: Reduction of high affinity membrane binding sites for ankyrin,” J. Clin. Invest. 68(6), 1566–1576 (1981). 10.1172/JCI110411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Nakashima K. and Beutler E., “ Erythrocyte cellular and membrane deformability in hereditary spherocytosis,” Blood. 53(3), 481–485 (1979). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Chasis J. A., Agre P., and Mohandas N., “ Decreased membrane mechanical stability and invivo loss of surface-area reflect spectrin deficiencies in hereditary spherocytosis,” J. Clin. Invest. 82(2), 617–623 (1988). 10.1172/JCI113640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Delaunay J., “ The molecular basis of hereditary red cell membrane disorders,” Blood Rev. 21(1), 1–20 (2007). 10.1016/j.blre.2006.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Costa L. Da, Mohandas N., Sorette M., Grange M. J., Tchernia G., and Cynober T., “ Temporal differences in membrane loss lead to distinct reticulocyte features in hereditary spherocytosis and in immune hemolytic anemia,” Blood 98(10), 2894–2899 (2001). 10.1182/blood.V98.10.2894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Mohandas N., Injo L.-L. E., Friedman M., and Mak J. W., “ Rigid membranes of Malayan ovalocytes: A likely genetic barrier against malaria,” Blood 63(6), 1385–1392 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Eber S. and Lux S. E., “ Hereditary spherocytosis—Defects in proteins that connect the membrane skeleton to the lipid bilayer,” Semin. Hematol. 41(2), 118–141 (2004). 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2004.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Waugh R. E. and Celle P. L. La, “ Abnormalities in the membrane material properties of hereditary spherocytes,” J. Biomech. Eng. 102(3), 240 (1980). 10.1115/1.3149580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Waugh R. E., “ Effects of inherited membrane abnormalities on the viscoelastic properties of erythrocyte-membrane,” Biophys. J. 51(3), 363–369 (1987). 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83358-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Waugh R. E. and Agre P., “ Reductions of erythrocyte-membrane viscoelastic coefficients reflect spectrin deficiencies in hereditary spherocytosis,” J. Clin. Invest. 81(1), 133–141 (1988). 10.1172/JCI113284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Silveira P., Cynober T., Dhermy D., Mohandas N., and Tchernia G., “ Red blood cell abnormalities in hereditary elliptocytosis and their relevance to variable clinical expression,” Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 108(4), 391–399 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Grundy S. M., Brewer H. B., Cleeman J. I., Smith S. C., and Lenfant C., “ Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the national heart, lung, and blood institute/American heart association conference on scientific issues related to definition,” Proceedings of NHLBI/AHA [Circulation 109(3), 433–438 (2004)]. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Devehat C. Le, Khodabandehlou T., and Vimeux M., “ Impaired hemorheological properties in diabetic patients with lower limb arterial ischaemia,” Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 25(2), 43–48 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Cho Y. I., Mooney M. P., and Cho D. J., “ Hemorheological disorders in diabetes mellitus,” J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2(6), 1130–1138 (2008). 10.1177/193229680800200622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Cecchin E., Demarchi S., Panarello G., and Deangelis V., “ Rheological abnormalities of erythrocyte deformability and increased glycosylation of hemoglobin in the nephrotic syndrome,” Am. J. Nephrol. 7(1), 18–21 (1987). 10.1159/000167423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Macrury S. M., Lockhart J. C., Small M., Weir A. I., Maccuish A. C., and Lowe G. D. O., “ Do rheological variables play a role in diabetic peripheral neuropathy,” Diabetic Med. 8(3), 232–236 (1991). 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1991.tb01578.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.McMillan D. E., “ Plasma protein changes, blood viscosity, and diabetic microangiopathy,” Diabetes. 25(2 Suppl), 858–864 (1976). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.McMillan D. E., Utterback N. G., and Puma J. L., “ Reduced erythrocyte deformability in diabetes,” Diabetes 27(9), 895–901 (1978). 10.2337/diab.27.9.895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Norton J. M., Barker N. D., and Rand P. W., “ Effect of cell geometry, internal viscosity, and pH on erythrocyte filterability,” Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 166(3), 449–456 (1981). 10.3181/00379727-166-41089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Brownlee M. and Cerami A., “ The biochemistry of the complications of diabetes mellitus,” Annu. Rev. Biochem. 50, 385–432 (1981). 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.002125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Brownlee M., Vlassara H., and Cerami A., “ Nonenzymatic glycosylation and the pathogenesis of diabetic complications,” Ann. Intern. Med. 101(4), 527–537 (1984). 10.7326/0003-4819-101-4-527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Watala C., Witas H., Olszowska L., and Piasecki W., “ The association between erythrocyte internal viscosity, protein nonenzymatic glycosylation and erythrocyte-membrane dynamic properties in juvenile diabetes-mellitus,” Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 73(5), 655–663 (1992). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Schonbein S.-H. and Volger E., “ Red-cell aggregation and red-cell deformability in diabetes,” Diabetes 25(2 Suppl), 897–902 (1976). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Dintenfass L., “ Blood viscosity factors in severe nondiabetic and diabetic retinopathy,” Biorheology 14(4), 151–157 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]