Abstract

Based on demonstrated favourable risk–benefit profiles, taxanes remain a key component in the first-line standard of care for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (nsclc) and nsclc subtypes. In 2012, a novel taxane, nab-paclitaxel (Abraxane: Celgene Corporation, Summit, NJ, U.S.A.), was approved, in combination with carboplatin, for the first-line treatment of locally advanced or meta-static nsclc. The approval was granted because of demonstrated improved antitumour activity and tolerability compared with solvent-based paclitaxel–carboplatin in a phase iii trial. This review focuses on the evolution of first-line taxane therapy for advanced nsclc and the new options and advances in taxane therapy that might address unmet needs in advanced nsclc.

Keywords: Docetaxel, elderly patients, nab-paclitaxel, paclitaxel, squamous cell carcinoma

1. INTRODUCTION

Non-small-cell lung cancer (nsclc) is a heterogeneous disease with multiple subtypes, including squamous cell carcinoma (scc), which accounts for 20%–30% of all nsclcs1,2. A large number of patients with nsclc are elderly, and 30% or more have a poor Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ecog) performance status (≥2)1,3,4. Outcomes for patients with advanced nsclc remain poor, with the 5-year survival rate being less than 4%1. The goals of treating advanced nsclc are therefore to prolong survival and to palliate symptoms.

Platinum-based doublet regimens, the current standard of care for the treatment of advanced nsclc, yield a 1-year survival rate of 30%–40% and are superior to single-agent therapy5,6. However, a plateau in efficacy has been reached with current standard-of-care options, and no single standard-of-care regimen is superior in the treatment of advanced nsclc7–10. Thus, physicians rely on numerous factors to optimize treatment strategies, including histology, age, performance status, cost, tolerability, and convenience. The combination of a platinum agent with a taxane—either solvent-based (sb) paclitaxel (Taxol: Bristol–Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ, U.S.A.) or docetaxel (Taxotere: Sanofi–Aventis, Bridgewater, NJ, U.S.A.)—has a proven efficacy and safety profile in advanced nsclc6. The sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin regimen is among those most commonly used for the first-line treatment of advanced nsclc in the United States11.

Recently, nab-paclitaxel, a 130-nm albumin-bound (“nab”) form of paclitaxel designed to use endogenous albumin pathways to increase intratumoural concentrations of the active drug, demonstrated improved antitumour activity and tolerability compared with sb-paclitaxel when both were used in combination with carboplatin in the first-line treatment of patients with advanced nsclc12. Based on the results of a phase iii trial, nab-paclitaxel in combination with carboplatin was approved in 2012 as first-line therapy for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic nsclc in patients who are not candidates for curative surgery or radiation therapy12,13. The present review summarizes the clinical experience to date with taxanes in the first-line treatment of nsclc.

2. DISCUSSION

2.1. Taxane–Platinum Combinations

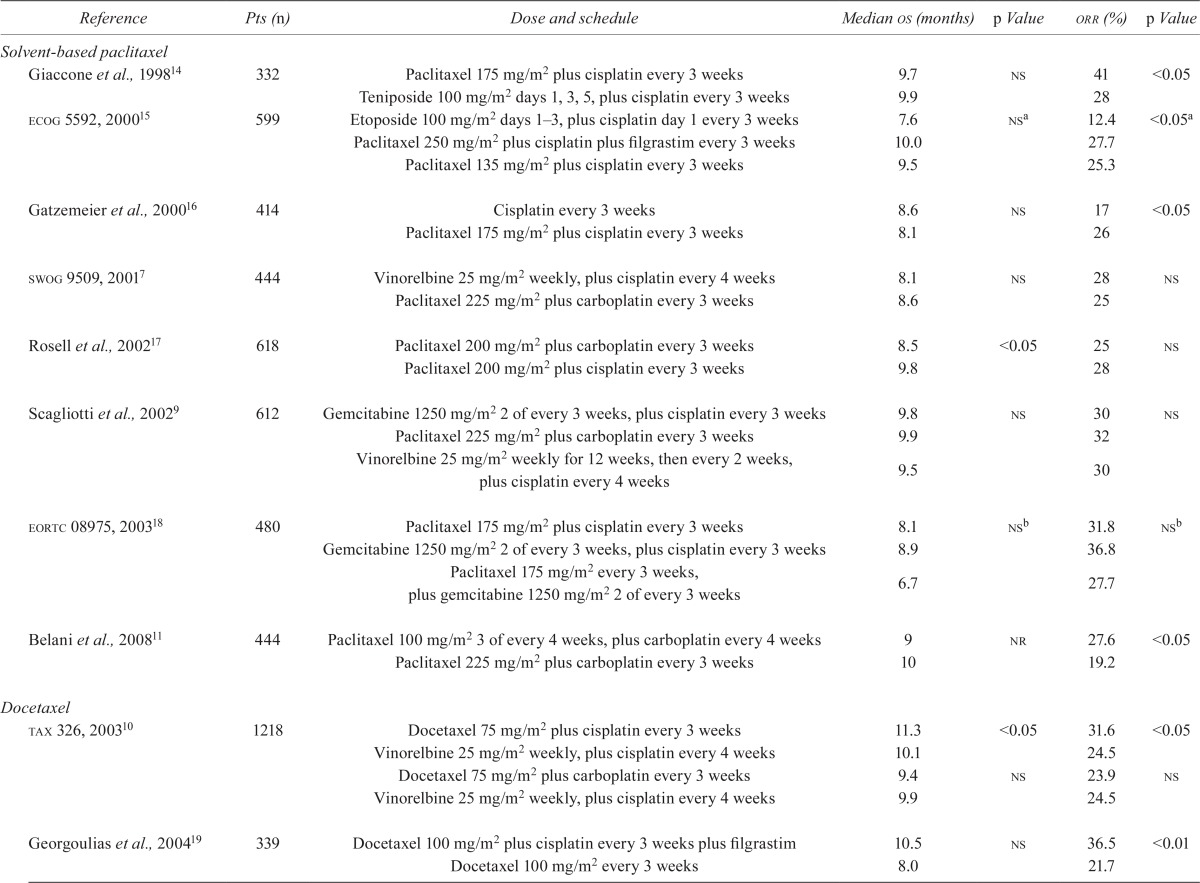

In landmark nsclc studies, overall response rates (orrs) were higher with taxane–platinum combinations than with other chemotherapy regimens (Table i). Historically, sb-paclitaxel given in combination with carboplatin or cisplatin demonstrated a median overall survival (os) of 7.7–10 months and an orr of 17%–41%7–9,11,14,16–18,22.

TABLE I.

Landmark studies of taxanes in the first-line treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer

| Reference | Pts (n) | Dose and schedule | Median os (months) | p Value | orr (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent-based paclitaxel | ||||||

| Giaccone et al., 199814 | 332 | Paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 plus cisplatin every 3 weeks | 9.7 | ns | 41 | <0.05 |

| Teniposide 100 mg/m2 days 1, 3, 5, plus cisplatin every 3 weeks | 9.9 | 28 | ||||

| ecog 5592, 200015 | 599 | Etoposide 100 mg/m2 days 1–3, plus cisplatin day 1 every 3 weeks | 7.6 | nsa | 12.4 | <0.05a |

| Paclitaxel 250 mg/m2 plus cisplatin plus filgrastim every 3 weeks | 10.0 | 27.7 | ||||

| Paclitaxel 135 mg/m2 plus cisplatin every 3 weeks | 9.5 | 25.3 | ||||

| Gatzemeier et al., 200016 | 414 | Cisplatin every 3 weeks | 8.6 | ns | 17 | <0.05 |

| Paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 plus cisplatin every 3 weeks | 8.1 | 26 | ||||

| swog 9509, 20017 | 444 | Vinorelbine 25 mg/m2 weekly, plus cisplatin every 4 weeks | 8.1 | ns | 28 | ns |

| Paclitaxel 225 mg/m2 plus carboplatin every 3 weeks | 8.6 | 25 | ||||

| Rosell et al.,200217 | 618 | Paclitaxel 200 mg/m2 plus carboplatin every 3 weeks | 8.5 | <0.05 | 25 | ns |

| Paclitaxel 200 mg/m2 plus cisplatin every 3 weeks | 9.8 | 28 | ||||

| Scagliotti et al., 20029 | 612 | Gemcitabine 1250 mg/m2 2 of every 3 weeks, plus cisplatin every 3 weeks | 9.8 | ns | 30 | ns |

| Paclitaxel 225 mg/m2 plus carboplatin every 3 weeks | 9.9 | 32 | ||||

| Vinorelbine 25 mg/m2 weekly for 12 weeks, then every 2 weeks, plus cisplatin every 4 weeks | 9.5 | 30 | ||||

| eortc 08975, 200318 | 480 | Paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 plus cisplatin every 3 weeks | 8.1 | nsb | 31.8 | nsb |

| Gemcitabine 1250 mg/m2 2 of every 3 weeks, plus cisplatin every 3 weeks | 8.9 | 36.8 | ||||

| Paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 every 3 weeks, plus gemcitabine 1250 mg/m2 2 of every 3 weeks | 6.7 | 27.7 | ||||

| Belani et al., 200811 | 444 | Paclitaxel 100 mg/m2 3 of every 4 weeks, plus carboplatin every 4 weeks | 9 | nr | 27.6 | <0.05 |

| Paclitaxel 225 mg/m2 plus carboplatin every 3 weeks | 10 | 19.2 | ||||

| Docetaxel | ||||||

| tax 326, 200310 | 1218 | Docetaxel 75 mg/m2 plus cisplatin every 3 weeks | 11.3 | <0.05 | 31.6 | <0.05 |

| Vinorelbine 25 mg/m2 weekly, plus cisplatin every 4 weeks | 10.1 | 24.5 | ||||

| Docetaxel 75 mg/m2 plus carboplatin every 3 weeks | 9.4 | ns | 23.9 | ns | ||

| Vinorelbine 25 mg/m2 weekly, plus cisplatin every 4 weeks | 9.9 | 24.5 | ||||

| Georgoulias et al., 200419 | 339 | Docetaxel 100 mg/m2 plus cisplatin every 3 weeks plus filgrastim | 10.5 | ns | 36.5 | <0.01 |

| Docetaxel 100 mg/m2 every 3 weeks | 8.0 | 21.7 | ||||

| Kubota et al., 200420 | 311 | Docetaxel 60 mg/m2 plus cisplatin every 3–4 weeks | 11.3 | <0.05 | 37.1 | <0.01 |

| Vindesine 3 mg/m2 3 of every 4 weeks, plus cisplatin every 4 weeks | 9.6 | 21.2 | ||||

| btog 1, 200621 | 433 | Docetaxel 75 mg/m2 plus carboplatin every 3 weeks | 9.5 | ns | 32 | ns |

| micor mvpc every 3 weeks | 8.7 | 32 | ||||

| Solvent-based paclitaxel and docetaxel | ||||||

| ecog 1594, 20028 | 1207 | Paclitaxel 135 mg/m2 plus cisplatin every 3 weeks | 7.8 | nsd | 21 | nsd |

| Gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 days 1, 8, 15, plus cisplatin every 4 weeks | 8.1 | 22 | ||||

| Docetaxel 75 mg/m2 plus cisplatin every 3 weeks | 7.4 | 17 | ||||

| Paclitaxel 225 mg/m2 plus carboplatin every 3 weeks | 8.1 | 17 |

No significant difference was observed between either paclitaxel arm and etoposide, but the orr for both paclitaxel arms was significantly higher than that for the etoposide arm.

Two pairwise comparisons were performed.

Patients received either micor mvp.

Comparison with the paclitaxel–cisplatin arm.

Pts = patients; os = overall survival; orr = overall response rate; ns = nonsignificant; ecog = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; swog = formerly the Southwest Oncology Group; eortc = European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; nr = not reported; btog = British Thoracic Oncology Group; mic = mitomycin, ifosfamide, cisplatin; mvp = mitomycin, vinblastine, cisplatin.

The efficacy of sb-paclitaxel–cisplatin was established in several large phase iii trials in advanced nsclc14–16. The efficacy and safety of sbpaclitaxel–cisplatin and sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin were compared in a large phase iii trial in patients with advanced nsclc17. In that trial, both regimens demonstrated similar response rates [28% vs. 25%, p = nonsignificant (ns)], the primary study endpoint, and manageable toxicity. Overall survival was longer with sb-paclitaxel–cisplatin than with sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin [median: 9.8 months vs. 8.5 months; hazard ratio (hr): 1.2; 90% confidence interval (ci): 1.03 to 1.40]. Based on that survival advantage, the authors recommended sb-paclitaxel–cisplatin for the treatment of advanced nsclc, with sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin as a viable alternative based on its safety profile and ease of administration.

First-line docetaxel plus cisplatin or carboplatin has also demonstrated efficacy, with a median os of 7.4–11.3 months and an orr of 17%–37% in phase iii trials in patients with advanced nsclc8,10,19–21. In the tax 326 trial, docetaxel in combination with cisplatin or carboplatin was compared with vinorelbine (Navelbine: Píerre Fabre Médicament, Boulogne, France) plus cisplatin (Table i)10. The orrs in the docetaxel–cisplatin, docetaxel–carboplatin, and vinorelbine–cisplatin arms were 32%, 24%, and 25% respectively; the difference in response was significant only for docetaxel–cisplatin compared with vinorelbine–cisplatin (p = 0.029). Additionally, docetaxel–cisplatin was associated with improved survival compared with vinorelbine–cisplatin (median os: 11.3 months vs. 10.1 months, p = 0.044); however, docetaxel–carboplatin did not show a survival advantage over vinorelbine–cisplatin (median os: 9.4 months vs. 9.9 months, p = ns). The docetaxel–platinum arms were also associated with improved tolerability, resulting in fewer grades 3 and 4 adverse events (aes) than resulted with vinorelbine–cisplatin. Those findings were consistent with findings in other phase iii trials comparing docetaxel–platinum combinations with other chemotherapy regimens8,10,19–21. The most common grades 3 and 4 aes reported with docetaxel–platinum combinations were neutropenia, leucopenia, and nausea and vomiting8,10,19–21.

The relative clinical benefit of various taxane–platinum regimens was evaluated in the landmark phase iii study ecog 1594, which compared the efficacy and safety of sb-paclitaxel plus cisplatin or carboplatin, docetaxel–cisplatin, and gemcitabine–cisplatin8. Although no survival advantage was noted for any of the 4 arms, the rate of aes was lower with sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin than with the other regimens8. Based on those findings, the sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin regimen became the reference regimen for future phase iii studies.

The effect of the taxane schedule on outcomes and tolerability has also been evaluated in the setting of advanced nsclc. Although an every-3-weeks schedule is indicated for sb-paclitaxel in the treatment of advanced nsclc23, a lower incidence of myelosuppression and neuropathy has been reported with weekly regimens. Thus, the weekly schedule might allow for delivery of a higher dose intensity of paclitaxel with less toxicity. Additionally, low-dose sb-paclitaxel has demonstrated proapoptotic and antiangiogenic effects in vitro24. Evidence from several phase ii/iii trials comparing the every-3-weeks and weekly schedules of sb-paclitaxel and docetaxel have demonstrated no significant difference in orr or survival in patients with advanced nsclc11,25–30. In those studies, the weekly schedule of sb-paclitaxel resulted in a higher incidence of anemia, and the every-3-weeks schedule resulted in a higher incidence of neuropathy11,25,29. Similarly, no difference in outcomes was noted between the every-3-weeks and weekly schedules of docetaxel in the second-line setting in patients with advanced nsclc, but hemato-logic events were more common in the every-3-weeks arms, with the exception of anemia in one study26–28.

2.2. Taxanes in Combination with Other Third-Generation Chemotherapy Agents

The advent of newer therapies has opened up a greater number of options for patients. Accordingly, the efficacy and safety of taxanes in combination with other third-generation chemotherapy agents such as gemcitabine and vinorelbine have also been assessed31–35.

No difference in efficacy outcomes were reported in a phase iii trial comparing sb-paclitaxel–gemcitabine with sb-paclitaxel–vinorelbine in patients with advanced nsclc, but more patients in the vinorelbine arm than in the gemcitabine arm experienced severe leucopenia, neutropenia, and febrile neutropenia (p < 0.001)32. Similarly, no survival advantage has been reported in phase iii trials comparing gemcitabine–carboplatin, gemcitabine–sb-paclitaxel, and sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin as first-line treatment for patients with advanced nsclc33,34.

In general, the incidence of grades 3 and 4 aes was higher with gemcitabine–carboplatin than with other regimens, but sb-paclitaxel–containing regimens resulted in a higher incidence of grades 3 and 4 sensory neuropathy34.

Current evidence suggests that a taxane plus gemcitabine is as effective as taxane–platinum doublets in the first-line treatment of advanced nsclc. However, the ae profiles of taxane doublets vary by agent and should be considered when a first-line therapy is chosen. In general, a taxane plus gemcitabine can be considered when a platinum agent is contraindicated6,31.

2.3. Taxanes in Combination with Molecularly Targeted Agents

The addition of molecularly targeted agents to taxane–platinum regimens, including agents targeting the angiogenesis pathway or known mutations associated with advanced nsclc, has been evaluated in several studies36–41.

In a phase ii trial of patients with advanced nsclc, the addition of bevacizumab to sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin resulted in a median os of 17.7 months compared with 14.9 months with sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin alone40. Toxicity was greater overall with the addition of bevacizumab, and a greater number of life-threatening pulmonary hemorrhagic events was observed, especially in patients with scc. Thus, patients with scc were excluded from the subsequent phase iii ecog 4599 trial37. In that trial, the addition of bevacizumab to sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin significantly improved median os (12.3 months vs. 10.3 months with the chemotherapy alone, p = 0.003), but was associated with greater toxicity and a greater incidence of treatment-related deaths. Based on those results, bevacizumab was approved for patients with nonsquamous nsclc42. More recently, a large open-label phase iii trial (PointBreak) evaluated the addition of bevacizumab to first-line sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin or pemetrexed–carboplatin with respect to survival outcomes in patients with advanced nonsquamous nsclc43. No significant difference in os was observed (median: 12.6 months in the pemetrexed arm vs. 13.4 months in the sb-paclitaxel arm; hr: 1.00; 95% ci: 0.86 to 1.16; p = 0.949), the primary endpoint of the study. However, a statistically significant improvement in progression-free survival (pfs) favouring the pemetrexed arm was noted (median pfs: 6.0 months vs. 5.6 months; hr: 0.83; 95% ci: 0.71 to 0.96; p = 0.012). The orr (34.1% vs. 33.0%) and the disease control rate (65.9% vs. 69.8%) were similar in the treatment arms. Patients whose disease did not progress after first-line treatment received maintenance therapy with pemetrexed–bevacizumab in the pemetrexed arm (n = 292); patients in the sb-paclitaxel arm received bevacizumab as a single agent (n = 298). In a prespecified noncomparative survival analysis of patients who received maintenance therapy in the pemetrexed and sb-paclitaxel arms, median os was 17.7 months and 15.7 months respectively, and median pfs was 8.6 months and 6.9 months respectively. Toxicity profiles in the two regimens differed, with significantly more (p ≤ 0.025) treatment-related grades 3 and 4 anemia (14.5% vs. 2.7%), thrombocytopenia (23.3% vs. 5.6%), and fatigue (10.9% vs. 5.0%) in the pemetrexed arm and significantly more grades 3 and 4 neutropenia (40.6% vs. 25.8%), febrile neutropenia (4.1% vs. 1.4%), sensory neuropathy (4.1% vs. 0%) and grades 1 and 2 alopecia (36.8% vs. 6.6%) in the sb-paclitaxel arm. Altogether, those findings demonstrate similar activity for pemetrexed and sb-paclitaxel when used in combination with carboplatin–bevacizumab in the first-line treatment of patients with advanced nonsquamous nsclc.

Results from trials of cetuximab (Erbitux: Bristol–Myers Squibb) in combination with taxane–carboplatin have been mixed38,39. In the BMS099 trial, patients received sb-paclitaxel or docetaxel, both in combination with carboplatin, with or without cetuximab as first-line therapy39. The median pfs (primary endpoint) was similar for treatment with or without cetuximab (4.4 months vs. 4.2 months, p = ns). An improved orr was observed with cetuximab added to chemotherapy (26% vs. 17% with chemotherapy alone, p = 0.007). The median os for cetuximab plus chemotherapy was 9.7 months; it was 8.4 months with chemotherapy alone (p = ns). Treatment-related grades 3 and 4 aes occurred more often with cetuximab. In the swog (formerly the Southwest Oncology Group) S0342 study, in which patients received either first-line sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin with concurrent cetuximab and maintenance cetuximab afterward, or sequential sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin followed by cetuximab, the orrs were similar in the treatment arms (concurrent: 32%; sequential: 30%; p = ns), as were the median oss (concurrent: 10.9 months; sequential: 10.7 months; p = ns)38. Compared with sequential therapy, concurrent therapy was associated with significantly greater rates of grades 3 and 4 toxicities (p = 0.002).

The foregoing studies demonstrated that the taxane–platinum combination plus a targeted agent was efficacious in patients with advanced nonsquamous nsclc; however, the addition of targeted agents was associated with an increased risk of toxicity.

2.4. A New Taxane for the Treatment of NSCLC

The rationale for the development of nab-paclitaxel stemmed from the observation that although sbpaclitaxel is effective, the solvent used in the formulation (Kolliphor el, formerly known as Cremophor el) could lead to severe hypersensitivity reactions and peripheral neuropathy44–46. In addition, Kolliphor el can reduce the availability of paclitaxel to tumours by entrapping paclitaxel in micelles46,47. Compared in preclinical models with sb-paclitaxel, nab-paclitaxel reached a mean maximum blood concentration of free paclitaxel that was higher by a factor of 10 and an intratumoural concentration that was 33% higher in patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumours48,49. Enhanced transport across endothelial cell layers was also demonstrated for nab-paclitaxel compared with sb-paclitaxel49. Because of its unique albumin formulation, nab-paclitaxel can be administered safely at doses higher than are possible with sb-paclitaxel13,47. Compared with sb-paclitaxel, nabpaclitaxel also requires a shorter infusion time13,23. Furthermore, sb-paclitaxel requires premedication to prevent hypersensitivity reactions; because of its solvent-free formulation, nab-paclitaxel does not13,23.

In several trials, nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin demonstrated antitumour activity12,50,51. A phase i/ii study of nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin identified the maximum tolerated dose of single-agent nab-paclitaxel as 125 mg/m2 administered in the first 3 weeks of a 4-week cycle51. The median os was 11 months, the orr was 30%, and the most common treatment-related toxicities were grades 3 and 4 neutropenia and grade 3 leucopenia, sensory neuropathy, fatigue, diarrhea, and anemia. Patients who experienced grade 3 sensory neuropathy generally experienced improvement to grade 2 or less within 60 days. A subsequent dose-finding study revealed that nab-paclitaxel 100 mg/m2 weekly, plus every-3-weeks carboplatin, had a favourable efficacy and safety profile in patients with advanced nsclc50. The 100 mg/m2 3-of-4-weeks regimen resulted in an orr of 48% and a median os of 11.3 months. Furthermore, compared with an every-3-weeks schedule of nab-paclitaxel, the former regimen was associated with a lower rate of grade 3 or greater aes and with significant reductions in the incidence of peripheral neuropathy, myalgia, arthralgia, and alopecia. Thus, the 100 mg/m2 3-of-4-weeks dose and schedule was chosen for a phase iii trial. In the randomized registered trial comparing that schedule of nab-paclitaxel with an every-3-weeks sb-paclitaxel schedule (both with carboplatin), the nab-paclitaxel combination demonstrated a significantly higher orr (33% vs. 25%, p = 0.005), the primary endpoint of the study; a 0.5-month longer median pfs (6.3 months vs. 5.8 months; hr: 0.902; 95% ci: 0.767 to 1.060; p = 0.214); and a greater than 1-month-longer median os (12.1 months vs. 11.2 months; hr: 0.922; 95% ci: 0.797 to 1.066; p = 0.271) as first-line treatment for patients with advanced nsclc12. The nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin combination was associated with more thrombocytopenia and anemia, but with significantly less sensory neuropathy, neutropenia, arthralgia, and myalgia. Additionally, patients receiving nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin experienced a faster time to improvement in sensory neuropathy: median time to improvement from grade 3 or greater sensory neuropathy to grade 1 was 38 days for nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin and 104 days for sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin. Compared with sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin, nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin was also associated with statistically and clinically significant reductions in patient-reported neuropathy, neuropathic pain in the hands and feet, and hearing loss assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Taxane instrument12,52.

2.5. Taxanes and Histology

Targeted therapies including bevacizumab, cetuximab, and the thymidylate synthase inhibitor pemetrexed (Alimta: Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, U.S.A.) have demonstrated benefit in some patient populations, but the observed benefit has been mixed and often dictated by histology37,53–57. Some patients with nonsquamous nsclc derive greater benefit from those agents than from the standard of care, whereas no benefit compared with chemotherapy might be observed for patients with scc37,53,54. Thus, treatment options for the latter patients are limited. Use of bevacizumab is limited to patients with nonsquamous histology42. Pemetrexed is also currently not indicated for scc because of a lack of efficacy54,58, possibly related to higher expression of thymidylate synthase in scc tumours59. Furthermore, some nsclc tumours present with mixed histology (for example, adenosquamous)55; other tumours might be poorly differentiated, potentially containing a heterogeneous population of cells55,60. Until recently, histology was not generally considered when treatment decisions were made5. Few phase iii studies have assessed outcome by histology; however, subanalyses of such trials are beginning to surface in light of histology’s growing importance (Table ii)33,56,61.

TABLE II.

Efficacy outcomes from select histologic analyses of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with taxane-containing regimens

| Reference | Histologic subtype | Regimen |

os(months)

|

hr | 95% ci | orr (%) | 95% ci | or | 95% ci | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pts (n) | Median | 95% ci | |||||||||

| Scagliotti et al., 200957,a | |||||||||||

| Squamous | 187 | 11.9 | nr | nr | nr | nr | |||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 310 | 8.8 | nr | ||||||||

| Large cell | 54 | 9.5 | nr | ||||||||

| Other | 65 | 10.6 | nr | ||||||||

| Tan et al., 200961 | |||||||||||

| Squamous | |||||||||||

| Vinorelbine–cisplatin | 65b | 8.9 | 6.4 to 12.8 | nr | 24.6 | nr | |||||

| Docetaxel–cisplatin | 64b | 9.8 | 8.4 to 12.2 | 29.1 | |||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | |||||||||||

| Vinorelbine–cisplatin | 79b | 11.7 | 8.7 to 16.5 | 28.1 | |||||||

| Docetaxel–cisplatin | 75b | 11.6 | 9.7 to 15.7 | 22.7 | |||||||

| Treat et al., 201033 | |||||||||||

| Squamous | |||||||||||

| Gemcitabine–carboplatin | 67 | 6.6 | 5.1 to 9.5 | 1.4 | 0.93 to 1.99 | 25.4 | 15.5 to 37.5 | 0.40c | 0.18 to 0.88 | ||

| Gemcitabine–paclitaxel | 74 | 10.2 | 7.7 to 13.7 | 1.1 | 0.75 to 1.55 | 35.1 | 24.4 to 47.1 | 0.65 | 0.31 to 1.33 | ||

| Paclitaxel–carboplatin | 61 | 10.3 | 8.7 to 12.0 | Reference | 45.9 | 33.1 to 59.2 | Reference | ||||

| Nonsquamous | |||||||||||

| Gemcitabine–carboplatin | 67 | 8.2 | 7.3 to 9.5 | 0.96 | 0.81 to 1.13 | 25.3 | 20.6 to 30.5 | 0.93 | 0.65 to 1.34 | ||

| Gemcitabine–paclitaxel | 74 | 8.4 | 7.2 to 9.8 | 0.97 | 0.82 to 1.14 | 31.4 | 26.2 to 36.9 | 1.3 | 0.88 to 1.77 | ||

| Paclitaxel–carboplatin | 61 | 8.3 | 7.3 to 9.8 | Reference | 26.7 | 22.0 to 32.0 | Reference | ||||

Values reflect the combined treatment arms (patients received gemcitabine–cisplatin, paclitaxel–carboplatin, or vinorelbine–cisplatin).

Reflects enrolled patients; number of evaluable patients was not given.

p < 0.05.

Pts = patients; os = overall survival; ci = confidence interval; hr = hazard ratio; orr = overall response rate; or = odds ratio; nr = not reported.

Recently, a phase iii trial conducted by Treat and colleagues in patients with advanced nsclc treated with gemcitabine–carboplatin, gemcitabine–sbpaclitaxel, or sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin was retrospectively analyzed33,34. No difference in orr was noted for patients with nonsquamous histology, but compared with gemcitabine–carboplatin, sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin was associated with a significantly greater orr in patients with scc (46% vs. 25%, p = 0.02)33. Across treatment groups, no significant differences by histology were noted with regard to os or time to progression. Additionally, no significant differences were noted in grades 3 and 4 aes between scc and nonsquamous histologies.

The role of histology was also assessed in a retrospective analysis of a phase iii trial of first-line vinorelbine–cisplatin compared with sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin and with gemcitabine–cisplatin56. No significant difference by histology was observed in the efficacy of these regimens; however, overall, a survival advantage was observed for patients with scc compared with those with adenocarcinoma (p = 0.0021). In the phase iii Global Lung Oncology Branch trial 3, patients with advanced nsclc were treated with first-line vinorelbine–cisplatin or with docetaxel–cisplatin61. In patients with scc, median os was 9.8 months in the docetaxel arm and 8.9 months in the vinorelbine arm; the respective orrs were 28% and 25%. Median os was similar between the arms for patients with adenocarcinoma (11.6 months vs. 11.7 months); the orr was 23% in the docetaxel arm and 29% in the vinorelbine arm.

In patients with scc, nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin demonstrated an orr of 41% compared with 24% for sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin (p < 0.001, Table iii)12,62. In patients with nonsquamous histology, nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin was as efficacious as sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin in terms of response (26% vs. 25%, p = ns), and compared with sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin, nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin also demonstrated a nonsignificantly higher orr in patients with large-cell carcinoma (33% vs. 15%, p = ns) and in those with un-differentiated histology (24% vs. 15%, p = ns). In both arms, patients with adenocarcinoma experienced a similar orr (26% vs. 27%, p = ns). The antitumour activity and safety of nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin were also assessed in patients who were ineligible for bevacizumab (scc, history of thrombotic or embolic events or hemoptysis, or cavitary lung lesions)64. Results demonstrated an orr of 41% and a median os of 9.7 months in evaluable patients. The most common grades 3 and 4 toxicities were febrile neutropenia, infection, dyspnea, and dehydration.

TABLE III.

Efficacy outcomes from the phase iii trial of paclitaxel formulations with carboplatin in the first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer

|

Outcome

|

Regimen

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Type |

(A) Nab-paclitaxel and carboplatin

|

(B) Paclitaxel

a

and carboplatin

|

|||||||

| (n) | (%) | 95% ci | (n) | (%) | 95% ci | hr or rrr | 95% ci b | p Valuec | ||

| Intention-to-treat12 | 521 | 531 | ||||||||

| Median os (months) | 12.1 | 10.8 to 12.9 | 11.2 | 10.3 to 12.6 | 0.922 | 0.797 to 1.066 | ns | |||

| Overall response | 170 | 33 | 28.6 to 36.7 | 132 | 25 | 21.2 to 28.5 | 1.313 | 1.082 to 1.593 | 0.005 | |

| Complete response | 0 | 1 | <1 | |||||||

| Partial response | 170 | 33 | 131 | 25 | ||||||

| Stable diseased | 104 | 20 | 128 | 24 | ||||||

| Progressive disease | 83 | 16 | 84 | 16 | ||||||

| Squamous subset62 | 229 | 221 | ||||||||

| Median os (months) | 10.7 | 9.4 to 12.5 | 9.5 | 8.6 to 11.6 | 0.890 | 0.719 to 1.101 | ns | |||

| Overall response | 94 | 41 | 34.7 to 47.4 | 54 | 24 | 18.8 to 30.1 | 1.680 | 1.271 to 2.221 | <0.001 | |

| Nonsquamous subset62 | 292 | 310 | ||||||||

| Median os (months) | 13.1 | nr | 13.0 | nr | 0.950 | nr | nr | |||

| Overall response | 76 | 26 | 21.0 to 31.1 | 78 | 25 | 20.3 to 30.0 | 1.034 | 0.788 to 1.358 | ns | |

| Age ≥70 subset63 | 74 | 82 | ||||||||

| Median os (months) | 19.9 | 12.7 to 22.3 | 10.4 | 8.6 to 13.6 | 0.583 | 0.388 to 0.875 | 0.009 | |||

| Overall response | 25 | 34 | 23.0 to 44.6 | 20 | 24 | 15.1 to 33.7 | 1.385 | nr | ns | |

| Age <70 subset63 | 447 | 449 | ||||||||

| Median os (months) | 11.4 | 10.3 to 12.6 | 11.3 | 10.3 to 12.9 | 0.999 | 0.855 to 1.167 | ns | |||

| Overall response | 145 | 32 | 28.1 to 36.8 | 112 | 25 | 20.9 to 28.9 | 1.300 | NR | 0.013 | |

Solvent-based.

Calculated for rrrs according to the asymptotic 95% ci of the relative risk of regimen A to regimen B.

By chi-square test.

Defined as 16 weeks or more.

ci = confidence interval; hr = hazard ratio; rrr = response rate ratio; os = overall survival; ns = nonsignificant; nr = not reported.

The molecular mechanism or mechanisms explaining the antitumour activity of nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin in patients with scc remain unknown; however, several hypotheses have been put forward. Many are focused on mechanisms that could lead to greater intratumoural paclitaxel accumulation. Compared with other tumour types, scc tumours occur in close proximity to major blood vessels, which might allow for greater access to the bloodstream65. Moreover, pharmacokinetic studies have demonstrated a higher systemic exposure to free paclitaxel in patients receiving nab-paclitaxel than in those receiving sb-paclitaxel, and thus more free paclitaxel might be available to scc tumours48. Nab-paclitaxel might avoid the limitations of sbpaclitaxel (entrapment of free paclitaxel in Kolliphor el micelles) because it is albumin-bound46–48. Furthermore, albumin crosses endothelial cells by cell surface receptor–mediated transcytosis66. In preclinical studies, nab-paclitaxel crossed endothelial cell layers more efficiently (by a factor of more than 4) than sb-paclitaxel did49. Synergy between nab-paclitaxel and other chemotherapy agents has been suggested; thus, it is also possible that nabpaclitaxel acts in synergy with carboplatin67–69.

First-line nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin in combination with bevacizumab has also been assessed in patients with advanced nonsquamous nsclc70. The orr was 31%, and the median os was 16.8 months. The most common grades 3 and 4 aes were neutropenia, fatigue, febrile neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and neuropathy (with no grade 4 neuropathy being observed). Those results indicate that the nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin combination holds promise for the treatment of patients with advanced nonsquamous nsclc.

Nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin has demonstrated antitumour activity in patients with scc (for whom there is an unmet need) and in patients with nonsquamous histology in combination with bevacizumab. Future trials of nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin in combination with other targeted agents could reveal interesting findings in select patient populations.

2.6. Taxanes in the Elderly

The median age at diagnosis of lung cancer is approximately 70 years1. Unfortunately, many elderly patients are undertreated because of toxicity concerns, comorbidities, and poor performance status3. Elderly patients are often underrepresented in clinical trials, and their treatment options are limited for the mentioned reasons3,71. With increasing emphasis on the identification of the appropriate treatment for elderly patients, many subanalyses have been performed. Single-agent and platinum-based therapies have a historical median os of 8–13 months in phase iii studies in elderly patients with nsclc6,71–75.

In a phase iii trial (ifct-0501), elderly patients (70–89 years of age) with advanced nsclc and a World Health Organization performance status of 0–2 were randomized to sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin or single-agent vinorelbine or gemcitabine71. The sbpaclitaxel–carboplatin combination demonstrated a median os of 10.3 months compared with 6.2 months for monotherapy (p < 0.0001). Grades 3 and 4 aes occurred more frequently in the platinum doublet arm and included neutropenia, anemia, febrile neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, asthenia, and anorexia. Despite the increased toxicity, the survival benefits lend support for the use of doublet therapy in elderly patients. In a subanalysis of the ecog 4599 trial, the addition of bevacizumab to sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin resulted in a greater orr in patients 70 years of age or older (29% vs. 17% with sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin alone, p = ns), but no improvement in median os (11.3 months vs. 12.1 months, p = ns) and a higher degree of toxicity76.

Elderly patients treated with docetaxel–cisplatin in the tax 326 trial had a median os of 12.6 months; the os in the vinorelbine–cisplatin arm was 9.9 months; it was 9.0 months in the docetaxel–carboplatin arm72. More elderly patients in the vinorelbine arm than in either docetaxel arm experienced grades 3 and 4 aes, and more grades 3 and 4 aes occurred with docetaxel–carboplatin than with docetaxel–cisplatin. Regardless of treatment, more neurotoxicity, pulmonary events, infection, anorexia, dehydration, and neuromotor issues were experienced by elderly patients in the study than by younger patients. In two phase ii trials of docetaxel–carboplatin in elderly patients (median age: 74–75 years), the median os ranged from 9.9 months to 13.1 months, and the orr was approximately 47% in both trials77,78. Common grades 3 and 4 toxicities in both trials included neutropenia and anemia. Recent preliminary results from a phase iii trial of gemcitabine compared with docetaxel–gemcitabine in elderly patients revealed no significant differences in survival or response79.

Compared with sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin, nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin recently demonstrated improved outcomes in a subgroup of elderly patients (70 years of age and older) enrolled in a phase iii trial (Table iii)12,63, with a median os of 19.9 months compared with 10.4 months (p = 0.009). A higher orr was also observed in the elderly patients treated with nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin (34% vs. 24% with sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin, p = ns). Toxicities were similar in patients less than 70 and 70 or more years of age, and scores on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Taxane instrument revealed significant treatment effects favouring nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin for neuropathy (p < 0.001), pain in hands and feet (p < 0.001), edema (p = 0.004), and hearing loss (p = 0.022).

The underlying mechanisms contributing to the antitumour activity of nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin in those elderly patients remain unknown. It is possible that the improvement in toxicity with nab-paclitaxel compared with sb-paclitaxel, particularly in neuropathy and neutropenia, might allow for higher dose delivery and intensity12. Treatment-related aes can affect patient quality of life and can lead to dose reductions and delays, which can affect treatment outcomes. In elderly patients with advanced nsclc, greater chemotherapy dose intensity was demonstrated to correlate with better survival outcomes80.

Finally, among elderly patients in the aforementioned phase iii trial, a greater percentage receiving nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin than receiving sbpaclitaxel–carboplatin went on to receive second-line therapy, which has been demonstrated to improve survival over best supportive care or placebo63,81,82. Further studies are warranted to determine the reasons for the improved os demonstrated by nab-paclitaxel–carboplatin in elderly patients.

3. CONCLUSIONS

The efficacy and safety profiles of taxanes have remained consistent over the years since their introduction. In patients with advanced nsclc, sbpaclitaxel–carboplatin has long been considered the cornerstone of first-line therapy. More recently, compared with sb-paclitaxel–carboplatin, nabpaclitaxel–carboplatin has demonstrated improved response rates, manageable toxicity, and statistically and clinically significant reductions in patient-reported taxane-related symptoms. Those clinical benefits have also been observed in elderly patients and in patients with scc histology62,63. Thus, clinicians now have a new option in this class of drugs that, based on the current evidence, could offer improved benefit to patients with advanced disease, including those who are elderly or who have scc histology.

4. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing assistance was provided by Christopher Carter, phd, MediTech Media, funded by Celgene Corporation. The author is fully responsible for the content and editorial decisions with respect to this manuscript.

5. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

MAS has received honoraria from Celgene, Genentech, and Eli Lilly. He has received research grants from Celgene, Genentech, Merrimack Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Synta Pharmaceuticals, and Eli Lilly.

6. REFERENCES

- 1.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al., editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations) Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society . Learn About Cancer > Lung Cancer–Non-Small Cell > Detailed Guide > What is non-small cell lung cancer? [Web resource] Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2012. [Current version available at: http://www.cancer.org/Cancer/LungCancer-Non-SmallCell/DetailedGuide/non-small-cell-lung-cancer-what-is-non-small-cell-lung-cancer; cited May 15, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quoix E. Optimal pharmacotherapeutic strategies for elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Drugs Aging. 2011;28:885–94. doi: 10.2165/11595100-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lilenbaum RC, Cashy J, Hensing TA, Young S, Cella D. Prevalence of poor performance status in lung cancer patients: implications for research. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:125–9. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181622c17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azzoli CG, Baker S, Jr, Temin S, et al. on behalf of the American Society of Clinical Oncology American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update on chemotherapy for stage iv non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6251–66. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.5622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (nccn) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Ver 3.2014. Fort Washington, PA: NCCN; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly K, Crowley J, Bunn PA, Jr, et al. Randomized phase iii trial of paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin in the treatment of patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3210–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:92–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scagliotti GV, De Marinis F, Rinaldi M, et al. on behalf of the Italian Lung Cancer Project Phase iii randomized trial comparing three platinum-based doublets in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4285–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fossella F, Pereira JR, von Pawel J, et al. Randomized, multinational, phase iii study of docetaxel plus platinum combinations versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the tax 326 study group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3016–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belani CP, Ramalingam S, Perry MC, et al. Randomized, phase iii study of weekly paclitaxel in combination with carboplatin versus standard every-3-weeks administration of carboplatin and paclitaxel for patients with previously untreated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:468–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Socinski MA, Bondarenko I, Karaseva NA, et al. Weekly nab-paclitaxel in combination with carboplatin versus solvent-based paclitaxel plus carboplatin as first-line therapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: final results of a phase iii trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2055–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Celgene Corporation . Abraxane [package insert] Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giaccone G, Splinter TA, Debruyne C, et al. Randomized study of paclitaxel–cisplatin versus cisplatin–teniposide in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Lung Cancer Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2133–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.6.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonomi P, Kim K, Fairclough D, et al. Comparison of survival and quality of life in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with two dose levels of paclitaxel combined with cisplatin versus etoposide with cisplatin: results of an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:623–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gatzemeier U, von Pawel J, Gottfried M, et al. Phase iii comparative study of high-dose cisplatin versus a combination of paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3390–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.19.3390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosell R, Gatzemeier U, Betticher DC, et al. Phase iii randomised trial comparing paclitaxel/carboplatin with paclitaxel/cisplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a cooperative multinational trial. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1539–49. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smit EF, van Meerbeeck JP, Lianes P, et al. Three-arm randomized study of two cisplatin-based regimens and paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase iii trial of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Lung Cancer group—eortc 08975. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3909–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Georgoulias V, Ardavanis A, Agelidou A, et al. Docetaxel versus docetaxel plus cisplatin as front-line treatment of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized, multicenter phase iii trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2602–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubota K, Watanabe K, Kunitoh H, et al. Phase iii randomized trial of docetaxel plus cisplatin versus vindesine plus cisplatin in patients with stage iv non-small-cell lung cancer: the Japanese Taxotere Lung Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:254–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Booton R, Lorigan P, Anderson H, et al. A phase iii trial of docetaxel/carboplatin versus mitomycin C/ifosfamide/cisplatin (mic) or mitomycin C/vinblastine/cisplatin (mvp) in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised multicentre trial of the British Thoracic Oncology Group (btog1) Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1111–19. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belani CP, Lee JS, Socinski MA, et al. Randomized phase iii trial comparing cisplatin–etoposide to carboplatin–paclitaxel in advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1069–75. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bristol–Myers Squibb . Taxol [package insert] Princeton, NJ: Bristol–Myers Squibb; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vacca A, Ribatti D, Iurlaro M, et al. Docetaxel versus paclitaxel for antiangiogenesis. J Hematother Stem Cell Res. 2002;11:103–18. doi: 10.1089/152581602753448577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuette W, Blankenburg T, Guschall W, et al. Multicenter randomized trial for stage iiib/iv non-small-cell lung cancer using every-3-week versus weekly paclitaxel/carboplatin. Clin Lung Cancer. 2006;7:338–43. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2006.n.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuette W, Nagel S, Blankenburg T, et al. Phase iii study of second-line chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with weekly compared with 3-weekly docetaxel. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8389–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Camps C, Massuti B, Jiménez A, et al. Randomized phase iii study of 3-weekly versus weekly docetaxel in pretreated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a Spanish Lung Cancer Group trial. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:467–72. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gridelli C, Gallo C, Di Maio M, et al. A randomised clinical trial of two docetaxel regimens (weekly vs 3 week) in the second-line treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. The distal 01 study. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1996–2004. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Socinski MA, Ivanova A, Bakri K, et al. A randomized phase ii trial comparing every 3-weeks carboplatin/paclitaxel with every 3-weeks carboplatin and weekly paclitaxel in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:104–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kosmidis P, Mylonakis N, Skarlos D, et al. Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) plus carboplatin (6 auc) versus paclitaxel (225 mg/m2) plus carboplatin (6 auc) in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (nsclc): a multicenter randomized trial. Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group (hecog) Ann Oncol. 2000;11:799–805. doi: 10.1023/A:1008389402580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chu Q, Vincent M, Logan D, Mackay JA, Evans WK, on behalf of the Lung Cancer Disease Site Group of Cancer Care Ontario’s Program in Evidence-Based Care Taxanes as first-line therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and practice guideline. Lung Cancer. 2005;50:355–74. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kosmidis PA, Fountzilas G, Eleftheraki AG, et al. Paclitaxel and gemcitabine versus paclitaxel and vinorelbine in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. A phase iii study of the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group (hecog) Ann Oncol. 2011;22:827–34. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Treat JA, Edelman MJ, Belani CP, et al. on behalf of the Alpha Oncology Research Network A retrospective analysis of outcomes across histological subgroups in a three-arm phase iii trial of gemcitabine in combination with carboplatin or paclitaxel versus paclitaxel plus carboplatin for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2010;70:340–6. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Treat JA, Gonin R, Socinski MA, et al. on behalf of the Alpha Oncology Research Network A randomized, phase iii multi-center trial of gemcitabine in combination with carboplatin or paclitaxel versus paclitaxel plus carboplatin in patients with advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:540–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu Y, Xu X, Du Z, Shi M. Non-platinum regimens of gemcitabine plus docetaxel versus platinum-based regimens in first-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis on 9 randomized controlled trials. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69:1265–75. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1833-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herbst RS, Prager D, Hermann R, et al. on behalf of the tribute Investigator Group tribute: a phase iii trial of erlotinib hydro-chloride (OSI-774) combined with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5892–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxel–carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herbst RS, Kelly K, Chansky K, et al. Phase ii selection design trial of concurrent chemotherapy and cetuximab versus chemotherapy followed by cetuximab in advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: Southwest Oncology Group study S0342. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4747–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.9356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lynch TJ, Patel T, Dreisbach L, et al. Cetuximab and first-line taxane/carboplatin chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results of the randomized multicenter phase iii trial BMS099. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:911–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson DH, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny WF, et al. Randomized phase ii trial comparing bevacizumab plus carboplatin and paclitaxel with carboplatin and paclitaxel alone in previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2184–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herbst RS, Giaccone G, Schiller JH, et al. Gefitinib in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase iii trial—intact 2. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:785–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Genentech . Avastin [package insert] South San Francisco, CA: Genentech; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel J, Socinski MA, Garon EB, et al. A randomized, open-label, phase 3, superiority study of pemetrexed (Pem)+carboplatin (Cb)+bevacizumab (B) followed by maintenance Pem+B versus paclitaxel (Pac)+Cb+B followed by maintenance B in patients (pts) with stage iiib or iv non-squamous nonsmall cell lung cancer (ns-nsclc) [abstract LBPL1]. Presented at the 2012 Chicago Multidisciplinary Symposium in Thoracic Oncology; Chicago, IL. September 7, 2012; [Available online at: http://www.abstractsonline.com/Plan/ViewAbstract.aspx?sKey=af961e0dedd2-4b48-a08a-86579c4faf1a&cKey=167003ad-7c51-45e0-97a4-d48cb494f743&mKey={E968B2E9-DA03-409D-9B81-7EFE158EB9C1}; cited July 25, 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiss RB, Donehower RC, Wiernik PH, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions from Taxol. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1263–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.7.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gelderblom H, Verweij J, Nooter K, Sparreboom A. Cremophor el: the drawbacks and advantages of vehicle selection for drug formulation. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:1590–8. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00171-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.ten Tije AJ, Verweij J, Loos WJ, Sparreboom A. Pharmacological effects of formulation vehicles: implications for cancer chemotherapy. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:665–85. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sparreboom A, van Zuylen L, Brouwer E, et al. Cremophor el–mediated alteration of paclitaxel distribution in human blood: clinical pharmacokinetic implications. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1454–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gardner ER, Dahut WL, Scripture CD, et al. Randomized crossover pharmacokinetic study of solvent-based paclitaxel and nab-paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4200–5. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Desai N, Trieu V, Yao Z, et al. Increased antitumor activity, intratumor paclitaxel concentrations, and endothelial cell transport of Cremophor-free, albumin-bound paclitaxel, ABI-007, compared with Cremophor-based paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1317–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Socinski MA, Manikhas GM, Stroyakovsky DL, et al. A dose finding study of weekly and every-3-week nab-paclitaxel followed by carboplatin as first-line therapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:852–61. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181d5e39e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rizvi NA, Riely GJ, Azzoli CG, et al. Phase i/ii trial of weekly intravenous 130-nm albumin-bound paclitaxel as initial chemotherapy in patients with stage iv non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:639–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hirsh V, Okamoto I, Hon JK, et al. Patient-reported neuropathy and taxane-associated symptoms in a phase 3 trial of nabpaclitaxel plus carboplatin versus solvent-based paclitaxel plus carboplatin for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:83–90. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scagliotti GV, Novello S, von Pawel J, et al. Phase iii study of carboplatin and paclitaxel alone or with sorafenib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1835–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, et al. Phase iii study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3543–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Langer CJ, Besse B, Gualberto A, Brambilla E, Soria JC. The evolving role of histology in the management of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5311–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.8126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scagliotti GV, De Marinis F, Rinaldi M, et al. The role of histology with common first-line regimens for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a brief report of the retrospective analysis of a three-arm randomized trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1568–71. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c06980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scagliotti GV, Hanna N, Fossella F, et al. The differential efficacy of pemetrexed according to nsclc histology: a review of two phase iii studies. Oncologist. 2009;14:253–63. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eli Lilly and Company . Alimta [package insert] East Hanover, NJ: Eli Lilly and Company; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ceppi P, Volante M, Saviozzi S, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the lung compared with other histotypes shows higher messenger rna and protein levels for thymidylate synthase. Cancer. 2006;107:1589–96. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.D’Addario G, Früh M, Reck M, Baumann P, Klepetko W, Felip E, on behalf of the esmo Guidelines Working Group Metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: esmo clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 5):v116–19. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tan EH, Rolski J, Grodzki T, et al. Global Lung Oncology Branch trial 3 (glob3): final results of a randomised multinational phase iii study alternating oral and i.v. vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus docetaxel plus cisplatin as first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1249–56. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Socinski MA, Okamoto I, Hon JK, et al. Safety and efficacy by histology of weekly nab-paclitaxel in combination with carboplatin as first-line therapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2390–6. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Socinski MA, Langer CJ, Okamoto I, et al. Safety and efficacy of weekly nab-paclitaxel in combination with carboplatin as first-line therapy in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:314–21. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bertino EM, Villalona–Calero MA, Nana–Sinkam SP, et al. Phase 2 trial of nab-paclitaxel plus carboplatin for advanced nsclc in patients at risk of bleeding from vegf directed therapies [abstract LB-225] Cancer Res. 2012;72(suppl 1) doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2012-LB-225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wistuba II, Gazdar AF. Pathology of lung cancer. In: Syrigos KN, Nutting CM, Roussos C, editors. Tumors of the Chest. New York, NY: Springer; 2006. pp. 93–105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.John TA, Vogel SM, Tiruppathi C, Malik AB, Minshall RD. Quantitative analysis of albumin uptake and transport in the rat microvessel endothelial monolayer. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L187–96. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00152.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frese KK, Neesse A, Cook N, et al. Nab-paclitaxel potentiates gemcitabine activity by reducing cytidine deaminase levels in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:260–9. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schwartzberg LS, Arena FP, Mintzer DM, Epperson AL, Walker MS. Phase ii multicenter trial of albumin-bound paclitaxel and capecitabine in first-line treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2012;12:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Von Hoff DD, Ramanathan RK, Borad MJ, et al. Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel is an active regimen in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase i/ii trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4548–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.5742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reynolds C, Barrera D, Jotte R, et al. Phase ii trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel, carboplatin, and bevacizumab in first-line patients with advanced nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1537–43. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c0a2f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Quoix E, Zalcman G, Oster JP, et al. Carboplatin and weekly paclitaxel doublet chemotherapy compared with monotherapy in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: ifct-0501 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1079–88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60780-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Belani CP, Fossella F. Elderly subgroup analysis of a randomized phase iii study of docetaxel plus platinum combinations versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin for first-line treatment of advanced nonsmall cell lung carcinoma (tax 326) Cancer. 2005;104:2766–74. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lilenbaum RC, Herndon JE, 2nd, List MA, et al. Single-agent versus combination chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (study 9730) J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:190–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Langer CJ, Manola J, Bernardo P, et al. Cisplatin-based therapy for elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: implications of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 5592, a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:173–81. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.3.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chun SH, Lee JE, Park MH, et al. Gemcitabine plus platinum combination chemotherapy for elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective analysis. Cancer Res Treat. 2011;43:217–24. doi: 10.4143/crt.2011.43.4.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ramalingam SS, Dahlberg SE, Langer CJ, et al. Outcomes for elderly, advanced-stage non small–cell lung cancer patients treated with bevacizumab in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel: analysis of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial 4599. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:60–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim HJ, Kim TG, Lee HJ, et al. A phase ii study of combination chemotherapy with docetaxel and carboplatin for elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2010;68:248–52. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yoshimura N, Kudoh S, Kimura T, et al. Phase ii study of docetaxel and carboplatin in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:371–5. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31819846e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Karampeazis A, Vamvakas L, Pallis AG, et al. Docetaxel (D) plus gemcitabine (G) compared with G in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (nsclc): preliminary results of a randomized phase iii Hellenic Oncology Research Group trial [abstract 7605] J Clin Oncol. 2010. p. 28. [Available online at: http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/42372-74; cited July 26, 2014]

- 80.Luciani A, Bertuzzi C, Ascione G, et al. Dose intensity correlate with survival in elderly patients treated with chemo-therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2009;66:94–6. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2095–103. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]