Abstract

Objectives.

This study extends previous work on longitudinal patterns of spousal associations between functional impairments and psychological well-being in older couples in 3 important ways: By examining Mexican Americans, by considering a broader range of functional limitations, and by assessing the role of health status, social integration, and socioeconomic resources in these associations.

Method.

Drawing on data from 6 waves of the Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly (1993–2007), we employed growth curve models to investigate the implications of the spouse’s functional limitations for the respondent’s age trajectories of depressive symptoms in older Mexican American couples. Models were run separately for husbands and wives.

Results.

The spouse’s functional limitations were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms in the respondent. Personal resources can both ameliorate and intensify the adverse implications of the spouse’s functional limitations for the respondent’s depressive symptomatology. The interplay among these factors can vary by gender and the type of the spouse’s functional impairment.

Discussion.

Future studies would benefit by examining caregiving patterns in older couples, by distinguishing between different dimensions of social support available to them, and by considering changes in couples’ marital quality and social ties over time.

Key Words: Couples, Depressive symptoms, Functional limitations, Growth curve models, Mexican Americans, Older adults.

Elevated depressive symptomatology in old age is a significant public health concern because it is linked to higher levels of disability, morbidity, and mortality, increased health care costs, and poorer overall quality of life (Blazer, 2003). Psychological well-being of older adults can be contingent on the social context, such as marriage. For example, in addition to individual risk factors, functional decline of one spouse can contribute to the other spouse’s psychological distress for several reasons. In older couples, functional limitations in one spouse can lead to lower marital quality, decreases in family and other social activities and interactions, financial stress, role adjustments, and caregiver strain in the other spouse (Kim, Duberstein, Sorensen, & Larson, 2005;Pinquart & Sörenson, 2011).

Indeed, prior research demonstrates that older spouses’ well-being can be interdependent within and across different health domains (for review of the literature, see Meyler, Stimpson, & Peek, 2007; Walker & Luszcz, 2009). At the same time, wives tend to be more affected by husband’s health than vice versa (Ayotte, Yang, & Jones, 2010; Peek, Stimpson, Townsend, & Markides, 2006). Only a few previous studies, however, have focused on spousal associations between functional status and depressive symptoms in later life (Hoppmann, Gerstorf, & Hibbert, 2011; Robb, Small, & Haley, 2008; Siegel, Bradley, Gallo, & Kasl, 2004). Although some of the latter research was based on longitudinal data (Hoppmann et al., 2011; Siegel et al., 2004), it provides little guidance on the age-related dynamics in these associations. The age differences in spousal interrelatedness between various health outcomes can be shaped by such factors as expectations for aging, personal health issues, marital quality, burden of spousal caregiving, lifestyle changes, financial concerns, and personality characteristics (Beach, Schulz, Yee, & Jackson, 2000; Pecchioni, 2012). For instance, the adverse effect of the spouse’s functional limitations on the individual’s psychological well-being can diminish at older ages because physical health decline is normative and expected with increasing age (Covinsky, Lindquist, Dunlop, & Yelin, 2009; Fried & Guralnik, 1997; Stineman et al. 2013). Alternatively, the detrimental consequences of the spouse’s functional impairments can become stronger with advancing age because dealing with personal health issues can make spousal caregiving more challenging and stressful as individuals get older (McGhan, Loeb, Baney, & Penrod, 2013; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2011). Yet, the implications of the spouse’s functional limitations can be equally consequential for the individual’s mental health across age groups among older adults, albeit, as discussed earlier, for different reasons at different ages.

In addition, prior longitudinal research on spousal associations between functional impairments and depressive symptoms did not specifically investigate whether the impact of the spouse’s functional limitations is dependent on individuals’ resources such as health, social integration, and socioeconomic status and whether gender plays a role in the interplay between these factors. Yet, cross-sectional research in this area indicates that among spouses of individuals with functional limitations, coping resources, such as personality traits, can matter for their psychological well-being and can vary by gender (Robb et al., 2008). Furthermore, available studies in this area have not examined older married Mexican American couples. However, Hispanics in the United States, nearly two thirds of whom are Mexican Americans, are the largest ethnic minority group (16% of the total population; Ennis, Ríos-Vargas, & Albert, 2011). Moreover, the largest rate of growth for the U.S. elderly population (i.e., aged 65 and older) is expected among the Hispanic elderly population, which is estimated to increase from its current level of 6% to 17% by 2050 (PEW Hispanic Center, 2008). Also, the role of individuals’ own health, social integration, and socioeconomic status in spousal associations of health outcomes can be particularly crucial for older Mexican Americans because of their relatively poorer health, greater reliance on informal social support, and more limited socioeconomic resources (Chiriboga, Black, Aranda, & Markides, 2002; Markides et al., 1999; Zsembik, Peek, & Peek, 2000).

This study employs growth curve models separately for husbands and wives to examine whether in older Mexican American couples, the impact of the spouse’s functional limitations on the other spouse’s trajectories of depressive symptoms in older age is contingent on the level of individuals’ own health, social integration, and socioeconomic resources. Drawing on six waves of the Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly (H-EPESE), this study also extends prior research in this area by considering a broader range of functional limitations. We assess two self-reported measures and one performance-based measure in order to see whether the role of coping resources in spousal associations of health outcomes varies by the type of functional impairments. The self-reported measures include limitations in activities of daily living (ADL) and in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), whereas the performance-based measure comprises limitations captured by the performance-oriented mobility assessment (POMA). Previous studies examined only IADL limitations (Hoppmann et al., 2011) or a combined measure of ADL and IADL limitations (Robb et al., 2008; Siegel et al., 2004).

The Implications of Different Measures of Functional Limitations

Both ADL and IADL are self-reported measures, and they represent activities that are important for independent living. Yet, these measures have some differences that can lead to their differential effect on the other spouse’s psychological well-being and on the importance of coping resources available to individuals. ADL refer to the everyday basic tasks such as dressing or eating that are essential to personal self-care (Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson, & Jaffe, 1963), whereas IADL measure more complex tasks, including shopping, handling money, or doing light housework (Lawton & Brody, 1969). ADL limitations can be related to a greater risk for institutionalization and represent a more advanced stage of functional decline than IADL limitations (Keddie, Peek, & Markides, 2005). Compared with IADL limitations, ADL impairments can necessitate more intensive hands-on daily assistance. At the same time, IADL tend to require physical and cognitive capacities and, therefore, can reflect not only individuals’ functional ability but also certain skills (Keddie et al., 2005). Moreover, unlike ADL, IADL are not necessary for individuals’ everyday functioning.

The measure of POMA limitations is based on direct observation of the respondent’s physical mobility, balance, and lower body function by a trained interviewer (Guralnik, Branch, & Cummings, 1989). Both self-reported and observed measures of functional limitations can provide an accurate assessment of individuals’ physical functioning although the former measures can be susceptible to response bias (Caporaso, Pulkovski, Sprott, & Mannion, 2012). Self-reported and performance-based measures can each make a unique contribution to the evaluation of physical status (Coman & Richardson, 2006). For example, as self-reported measures, ADL and IADL can reflect individuals’ perceptions of everyday implications of living with functional limitations. In contrast, the performance-observed measure of POMA limitations might not capture individuals’ evaluation of day-to-day problems related to functional limitations. Individuals’ self-assessments of physical impairments, however, can be more sensitive to differences in their social context, including personal resources (Guralnik & Ferrucci, 2003).

Importance of Resources

Prior research on older couples show that regardless of gender, functional limitations in one spouse are predictive of the other spouse’s depressive symptomatology (Hoppmann et al., 2011; Robb et al., 2008; Siegel et al., 2004). A family stress theory (McCubbin & Patterson, 1983) suggests that individuals’ adjustment to and coping with stressful life circumstances such as family members’ functional decline depend, among other things, on resources available to them. In particular, the impact of stressors on individuals’ psychological well-being can be contingent on their health, social integration (i.e., social support, social networks, and social involvement), and socioeconomic resources. For example, better health status, including cognitive functioning, self-reported health, and chronic conditions, has beneficial implications for people’s psychological well-being (Black, Markides, & Miller, 1998; Djernes, 2006; Schnittker, 2005). Furthermore, research on spousal caregivers demonstrates that good health is associated with a lower level of psychological distress among individuals whose spouses experience health issues (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2011).

Social support can minimize the adverse effects of the spouse’s health problems because it is important for sustaining and improving older adults’ psychological well-being (Zunzunegui, Béland, & Otero, 2001) and for reducing their caregiving burden and stress (Pinquart, & Sörensen, 2011). Mental health can also be contingent on social networks and social involvement (Berkman & Glass, 2000). For instance, the availability of children, coresidence with children and others, and church attendance can facilitate older adults’ access to additional support and resources and provide them with opportunities for maintaining and developing social relationships (Choi & Bohman, 2007; Smits, van Gaalen, & Mulder, 2010). In addition, the literature suggests that a high degree of interaction with individuals from their own ethnic group can be a protective factor for the well-being of older Mexican Americans because ethnically homogeneous social networks are linked to greater levels of social support and better access to social resources among Hispanics (Hahn, Kim, & Chiriboga, 2011; Ostir, Eschbach, Markides, & Goodwin, 2003). Research also demonstrates that greater socioeconomic resources such as education, income, financial satisfaction, and health insurance coverage can be beneficial for older adults’ emotional well-being because they are associated, in addition to other advantages, with better coping strategies and skills (Cairney & Krause, 2005).

A greater availability of resources, however, may not only minimize but also increase the adverse psychological impact of the spouse’s functional impairments on the other spouse. Namely, among individuals with functionally impaired spouses, higher levels of resources may lead to lower levels of psychological well-being. Under certain circumstances, better health, greater social integration, and higher socioeconomic status may become themselves sources of stress for individuals whose spouses have functional limitations.

For example, the spouse’s functional decline and related increases in the other spouses’ family responsibilities can restrict social interactions and community involvement for both partners and, as a result, can contribute to individuals’ lower psychological well-being (Hoppman, Gerstorf, & Luszcz, 2008; Korporaal, Broese van Groenou, & van Tilburg, 2008). Yet, the loss or reduction in social engagement can be linked to even greater distress among those spouses of physically impaired persons who themselves have adequate physical health and socioeconomic resources to actively participate in social activities because these individuals may experience lower life satisfaction and stronger feelings of resentment and frustration. Similarly, greater social integration, such as strong informal networks or intergenerational coresidence, can constitute a resource, but it can also be linked to more stress (Markides & Krause, 1985; Tiedt, 2010). Despite being beneficial for psychological well-being because of greater availability of support, higher levels of social embeddedness can lead to even more reciprocal responsibilities and demands, in addition to caregiving, among individuals with physically impaired spouses.

Following prior research in this area, we hypothesize that the spouse’s functional limitations will be associated with more depressive symptoms in the other spouse across age. We also predict that resources available to the other spouse will make a difference in this associations. However, because previous research provides little guidance for the pattern of moderation, we do not formulate specific hypotheses regarding whether the spouse’s functional limitations will be linked to fewer or more depressive symptoms when we take into account the other spouse’s resources.

Gender

Prior research suggests that spousal associations in health outcomes and individuals’ coping resources can vary by gender. In general, older women, including Mexican American women, tend to report poorer psychological well-being than older men (Black et al., 1998; Djernes, 2006). Although available research on spousal associations in functional limitations and depressive symptoms does not provide evidence for gender differences (Hoppmann et al., 2011; Robb et al., 2008; Siegel et al., 2004), several studies that consider the impact of other dimensions of the spouse’s physical health on individuals’ depressive symptomatology or that examine spousal concordance in psychological distress demonstrate that regardless of race/ethnicity, the husband’s well-being can be a stronger predictor of the wife’s well-being than vice versa (Ayotte et al., 2010; Peek et al., 2006). Also, functional disabilities are likely to require caregiving and spouses usually serve as primary caregivers for older adults (Pinquart & Sörenson, 2011). Research on spousal caregiving suggests, however, that it is more detrimental for women’s psychological and physical health than for men’s (Burton, Zdaniuk, Schulz, Jackson, & Hirsch, 2003).

The literature offers several explanations for the gender differences in spousal interdependencies in health outcomes and in the implications of spousal caregiving. Due to gender role socialization and traditional marital roles, women can be more emotionally attuned to their spouse’s well-being and, therefore, at greater risk for psychological distress (Barnet & Baruch, 1987). This can be particularly true for older cohorts and for Mexican Americans who are more likely to adhere to traditional gender roles (Parrado, Flippen, & McQuiston, 2005). Also, the literature on caregiving indicates that women caregivers are less likely than men to practice preventive health behaviors, participate in respite care, and ask for support from informal and formal caregivers (Navaie-Waliser, Spriggs, & Feldman, 2002). In contrast, men might be more likely to seek help with caregiving because they tend to be less prepared by socialization or experience for caregiving tasks (Stoller, 1990). In general, research on spousal caregiving indicates that regardless of race/ethnicity, husbands with functional limitations tend to rely solely on their wives for assistance whereas functionally impaired wives are more likely to depend on their adult children and other relatives for support than on their husbands (Feld, Dunkle, Schroepfer, & Shen, 2010). In addition, research on Mexican Americans demonstrates that due to their traditional gender role socialization, women of Mexican descent believe that they are supposed to provide care to their family members with little support from others (Adams, Aranda, Kemp, & Takagi, 2002; Herrera, Lee, Palos, & Torres-Vigil, 2008).

As mentioned earlier, prior research on spousal interdependencies in health that specifically examines gender differences in individuals’ coping resources is scarce. Yet, Robb and colleagues (2008) found gender differences in the effect of personality traits on spousal associations between functional limitations and depressive symptoms. Following prior research, we examine spousal associations between functional limitations and depressive symptoms separately for husbands and wives in order to explore the role of gender in these associations and in individuals’ coping resources.

Data and Methods

This research draws on data from six waves of the H-EPESE. The H-EPESE was based on an area probability, multistage sample of noninstitutionalized Mexican Americans aged 65 and older, residing in five southwestern states—Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and California. About 85% of Mexican American older adults reside in these states. The baseline data were collected in 1993–1994 on 3,050 individuals, with a response rate of 83% (Markides et al., 1999).

For the purposes of our analysis, we used information from original intact couples first interviewed at Wave 1. We excluded interviews with proxies, which were obtained when the sampled respondents could not be interviewed directly due to their illness, hospitalization, or temporary absence. We also did not include couples in which at least one of the spouses had missing information on depressive symptoms at each specific wave. Information on the number of interviewed respondents, proxies, attrition, intact couples, and missing data on depressive symptoms by wave is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Attrition of Couples Across Six Waves of the H-EPESE, 1993–2007

| Total N | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | Wave 5 | Wave 6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993–1994 | 1995–1996 | 1998–1999 | 2000–2001 | 2004–2005 | 2006–2007 | |||||||

| 3,050 | 2,438 | 1,980 | 1,682 | 1,167 | 921 | |||||||

| Husbands | Wives | Husbands | Wives | Husbands | Wives | Husbands | Wives | Husbands | Wives | Husbands | Wives | |

| Individuals | ||||||||||||

| Interviewed | 553 | 553 | 448 | 450 | 353 | 387 | 287 | 350 | 184 | 266 | 136 | 218 |

| Without proxies | 484 | 514 | 391 | 415 | 295 | 356 | 249 | 326 | 144 | 229 | 103 | 177 |

| Died | 51 | 35 | 148a | 102a | 211a | 139a | 314a | 206a | 367a | 256a | ||

| Refused | 19 | 21 | 16 | 18 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 28 | 11 | 22 | ||

| Lost to follow-up | 34 | 47 | 35 | 45 | 37 | 48 | 40 | 52 | 38 | 57 | ||

| Couples | ||||||||||||

| Intact | 553 | 407 | 289 | 227 | 130 | 85 | ||||||

| Without proxies | 457 | 332 | 227 | 193 | 93 | 50 | ||||||

| Without missing data on CES-Db | 448 | 299 | 206 | 175 | 86 | 46 | ||||||

Notes. CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; H-EPESE = Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly.

aCumulative deaths across waves.

bThe number of couples that was used for each wave in the analyses.

Source: Hispanic Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly.

In order to deal with panel attrition in the growth curve models, we used maximum likelihood estimation that enables us to incorporate all respondents observed at least once. Because attrition due to death was associated with more depressive symptoms among respondents, we included a dummy variable Died (0 = no, 1 = yes; for a similar approach, see Warner & Brown, 2011). Preliminary analyses (not shown) revealed that the inclusion of this indicator did not substantially change the results. The final data file represents 1,260 couple periods, with each couple contributing up to six observations.

Measures

Dependent Variable

Depressive symptoms of each spouse were measured at each wave with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). This scale contains 20 items: 16 negative affects (e.g., I felt lonely) and 4 positive affects (e.g., I was happy). Respondents reported how often they had a certain feeling in the last week (0 = rarely or none of the time, 4 = most or all of the time). The responses for the positive affect items were reverse coded. The total score of the CES-D was used as a continuous measure (range from 0 to 53). The scale had high internal consistency (husbands: α = .84–.96, wives: α = .87–.94, depending on wave).

Independent Variables and Control Variables

Education, income, health insurance, number of children, social network, immigrant, and duration of marriage came from Wave 1 and were used as time-invariant variables because they were not measured at all waves. The rest of the measures were treated as time-variant variables measured at each wave. To facilitate interpretation of the growth curve models, several continuous and ordinal variables were centered to the mean and median, respectively, so that zero indicated the average value on each measure (Singer & Willett, 2003). As discussed in more detail subsequently, we centered to the mean or the median the variables that did not contain a meaningful value of 0 (i.e., self-reported health, social support, church attendance, difficulty with bills, and duration of marriage) and those variables that had a real value of 0 but there was another more meaningful value (i.e., age, cognitive functioning, chronic conditions, number of children, education, and income). Missing values on all independent and control variables were handled using the Stata command ICE for multiple imputation. Most variables had less than 2% of missing values.

Trajectories of depressive symptoms were modeled as a function of age. Age was measured in years and centered at 65, the lowest observed age.

Functional limitations.

Three measures captured different types of functional or mobility limitations at each wave: ADL limitations, IADL limitations, and POMA limitations. These measures were used as dependent and independent variables.

ADL limitations were a summed indicator measuring whether respondents could not perform the following seven tasks without help: Walk across a small room, bathe, take care of personal grooming, dress, eat, transfer from a bed to a chair, and use the toilet (husbands: α = .87–.94, wives: α = .82–.98, depending on wave). ADL limitations ranged from 0 to 7, with higher scores indicating more functional disability.

IADL limitations were calculated by summing older adults’ responses to 10 items assessing whether they could not perform the following tasks without assistance: Use the phone, drive a car or travel alone on buses or taxis, go shopping for groceries or clothes, prepare meals, do light housework, take medicine, handle money, do heavy work around the house, walk up and down the stairs to the second floor, and walk half a mile (husbands: α = .76–.87, wives: α = .69–.87, depending on wave). IADL limitations ranged from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating more impairments.

POMA limitations were calculated by summing responses to the POMA, which was designed to measure physical mobility, balance, and lower body function among older adults (Guralnik et al., 1989). During the interview, respondents were asked to stand with the feet in several positions (side-by-side, semitandem, tandem, and full tandem), to rise from a chair without use of arms five consecutive times, and to walk 8 feet at a normal pace. Individuals could get a total possible score of 12, with higher scores indicating better physical functioning (husbands: α = .75–.86, wives: α = .65–.88, depending on wave).

Health.

Cognitive functioning was measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination scores (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975). The scale ranged from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating better cognition. It was mean centered on 25. Self-reported health captured respondents’ ratings of their overall health on a 4-point scale (1 = poor, 4 = excellent). It was mean centered on “2 = fair.” Chronic conditions measured whether a physician had ever told respondents they had any of the following conditions: Heart attack, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, cancer, and arthritis (range: 0–6). It was mean centered on 1. Similar chronic conditions have been used in research based on other surveys (Ayotte et al., 2010).

Social integration.

Social support was constructed as a mean scale from two items that asked how often the respondent could count on and talk about problems with family or friends in times of need (α = .69–.86, wives: α = .78–.86, depending on wave). All responses were reverse coded so that higher values indicated greater perceived support (1 = hardly ever, 3 = most of the time). This variable was centered on its median “3 = most of the time.” Number of children was a continuous measure that captured how many biological children, adopted children, foster children, or stepchildren the respondent had. This measure was mean centered on 5. Child in household and others in household were constructed from information provided in household rosters (0 = no, 1 = yes). Social network was constructed as a dichotomous variable from two questions at Wave 1 capturing whether throughout their adult life, respondents’ neighbors and close personal friends had been 0 = mostly Anglos or equal numbers of Anglos and Mexicans or 1 = mostly Mexican Americans (husbands: α = .72, wives: α = .78 at baseline). Church attendance captured how often the respondent went to religious services (1 = never or almost never, 5 = more than once a week). It was centered on its median “3 = once or twice a month.”

Socioeconomic resources.

Education was measured in years and was mean centered on 5. Income captured household income at Wave 1, and it was logged in the analyses to correct for skewness. It was also mean centered. Difficulty with bills captured whether the respondent had problems paying monthly bills at each wave (1 = a great deal, 4 = none). This measure was centered on its median “2 = some.” Health insurance assessed whether the respondent had health insurance coverage from any source at Wave 1 (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Sociodemographic characteristics.

This study takes into account immigrant status and duration of marriage because prior research indicates that these factors can make a difference in older adults’ depressive symptomatology (Butterworth & Rodgers, 2006; Stimpson, Eschbach, & Peek, 2007). Immigrant was a dichotomous variable (0 = no, 1 = yes). Duration of marriage was measured in years and was mean centered on 46.

Analytic Strategy

Descriptive statistics for the repeated observations of all study variables are presented in Table 2 separately for husbands and wives. Zero-order correlations (not shown) confirmed that none of the correlations among the independent and control variables exceeded .60.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics by Gender for All Variables, H-EPESE Pooled Sample, 1993–1994 (1,260 Couple Periods)

| Pooled range | Husbands | Wives | x 2/t test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| %/M (SD) | %/M (SD) | |||

| Depressive symptomsa | 0–(51) 53 | 6.51 (7.61) | 8.13 (8.51) | *** |

| Agea | 65–97 | 76.72 (6.20) | 74.09 (5.55) | *** |

| Functional impairments | ||||

| ADLa | 0 (no disability)–7 | 0.44 (1.43) | 0.40 (1.28) | |

| IADLa | 0 (no limitations)–10 | 1.57 (2.69) | 1.73 (2.46) | |

| POMAa | 0 (disabled)–12 | 7.33 (3.42) | 6.98 (3.20) | ** |

| Health | ||||

| Cognitive functioninga | 0 (low)–30 (high) | 24.00 (4.65) | 24.72 (4.30) | *** |

| Self-reported healtha | 1(poor)–4 (excellent) | 2.42 (0.86) | 2.28 (0.87) | *** |

| Chronic conditionsa | 0 (no chronic conditions)–6 | 1.30 (1.11) | 1.48 (1.09) | *** |

| Social integration | ||||

| Social supporta | 1 (hardly ever)–3 (most of the time) | 2.73 (0.51) | 2.77 (0.48) | *** |

| Number of childrenb | 0–(16) 18 | 5.47 (3.18) | 5.44 (3.29) | |

| Child in householda | 0 = no, 1 = yes | 27.70 | 27.62 | |

| Others in householda | 0 = no, 1 = yes | 15.56 | 15.95 | |

| Social networkb | 0 = mostly Anglos or equal number of Anglos and Mexicans, 1 = mostly Mexican Americans | 91.43 | 90.32 | *** |

| Church attendancea | 1 (never)–5 (more than once a week) | 3.07 (1.31) | 3.38 (1.23) | *** |

| Socioeconomic resources | ||||

| Education (in years)b | 0–17 | 5.09 (3.80) | 5.40 (3.78) | ** |

| Income (logged)b | 0–2.08 | 0.97 (0.41) | 0.92 (0.43) | *** |

| Difficulty with billsa | 1 (a great deal)–4 (none) | 2.42 (1.01) | 2.41 (1.02) | |

| Health insuranceb | 0 = no, 1 = yes | 95.32 | 93.81 | *** |

| Control variables | ||||

| Immigrantb | 0 = no, 1 = yes | 42.38 | 38.25 | *** |

| Duration of marriageb | (2) 1–66 | 45.72 (9.81) | 45.66 (9.91) | |

| Died | 0 = no, 1 = yes | 51.59 | 31.75 | *** |

Notes. Percentages and means/standard deviations are for original, noncentered, variables. ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; H-EPESE = Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly; POMA = performance-oriented mobility assessment.

aTime-variant measures.

bTime-invariant measures, measured at Wave 1.

**p < .01. ***p < .001.

Source: Hispanic Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly.

To examine the impact of the spouse’s functional limitations and respondents’ own factors on the respondents’ age trajectories of depressive symptoms, we employ growth curve models because they are appropriate for analyzing data collected on the same individuals over multiple points in time. This analytic approach takes into account the clustering of observations by estimating a single model that describes data at two levels—within-respondent and between-respondent (Singer & Willett, 2003). The level 1 model specifies individual trajectories of change and contains both an intercept (i.e., an average level of depressive symptoms at age 65) and a slope (i.e., an average rate of change in depressive symptoms with increasing age). The level 2 model accounts for variability in trajectories of change between individuals and includes random effects for the intercept and slope that indicate whether respondents vary in their levels of depressive symptoms at age 65 and/or the rate of change in their depressive symptomatology with increasing age, respectively. General linear mixed models were estimated applying the xtmixed procedure in Stata.

We begin with a linear change trajectory model of depressive symptoms of individual i at time t (Y ti), as a function of age (Ageti). We then add our main independent variable, a relevant measure of the spouse’s functional limitations (FLti). We also included the interaction term between age and the measures of the spouse’s functional limitations to investigate whether the effect of the spouse’s functional impairments on the respondent’s psychological well-being can vary by age. The level 1 equation was as follows:

where π0i is the intercept of the growth trajectory representing the average number of depressive symptoms at age 65 (the youngest age), π1i is the linear component of the slope of the trajectory representing the average rate of change in depressive symptoms with each additional year of change, π2i represents change associated with functional limitations, π3i represents age-dependent change associated with functional limitations, and εti is the within-individual error term.

In the level 2 models, the coefficients πs in the level 1 model are modeled as dependent variables. In addition, the level 2 models examine whether variations in the intercept are predicted by a set of k covariates (β01 X 1i … β0k X ki). Because the focus of our analysis is the impact of spousal functional limitations, the slope of age does not depend on level 2 covariates. The two models of the intercept π0i and the linear rate of change π1i were written at the level 2 as follows:

where β00 and β10 are the average intercept and the average linear slope of the age trajectory, respectively, ς0i is the random error term of the average intercept, and ς1i is the random error term of the average linear slope.

The combined model of the observed repeated measures of respondents’ depressive symptoms adds the level 1 and level 2 models together. This model is presented in Model 4 in Tables 3–5.

Table 3.

Results from Growth Curve Models Estimating the Impact of Spousal ADL Limitations on the Other Spouse’s Depressive Symptoms Over Time, H-EPESE, 1993–2007 (1,260 Couple Periods)

| Husbands | Wives | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 5.43*** | 5.34*** | 8.89*** | 5.50*** | 7.23*** | 6.60*** | 5.04*** | 7.50*** | 7.44*** | 9.93*** | 6.24*** | 8.71*** | 8.19*** | 7.48*** |

| Linear slope (Age) | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.08* | −0.06 | −0.10* | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.05 | −0.14** | −0.12** | −0.12* | −0.07 | −0.05 |

| Spousal ADL | 0.36* | 0.68 | 0.57 | 0.09 | 0.73† | 1.09 | 0.90 | 0.42* | 0.62† | 0.59† | 0.22 | 0.71† | 0.87 | 1.40† |

| Spousal ADL × Age | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.04† | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.01 | ||

| Health | ||||||||||||||

| Cognitive functioning | −0.20*** | −0.14** | −0.24*** | −0.19** | −0.13* | −0.16** | ||||||||

| Self-reported health | −1.42*** | −1.06*** | −1.71*** | −1.93*** | −1.56*** | −1.91*** | ||||||||

| Chronic conditions | 0.30 | 0.18 | 0.38† | 0.58* | 0.55* | 0.63* | ||||||||

| Spousal ADL × Cognitive functioning | −0.01 | −0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal ADL × Self-reported health | 0.38* | −0.25 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal ADL × Chronic conditions | −0.16 | −0.16 | ||||||||||||

| Social integration | ||||||||||||||

| Social support | −1.73*** | −1.43*** | −1.72*** | −2.17*** | −1.50*** | −2.33*** | ||||||||

| Number of children | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.15† | −0.14 | −0.19* | 0.03 | ||||||||

| Child in household | −0.98† | −0.82† | −1.51** | 0.11 | 0.42 | −0.11 | ||||||||

| Others in household | −0.34 | −0.39 | −0.28 | −0.40 | −0.09 | −0.38 | ||||||||

| Social network | −2.12* | −1.57* | −1.08 | −1.88* | −0.97 | −1.37 | ||||||||

| Church attendance | −0.43** | −0.30* | −0.59** | −0.27 | −0.09 | −0.51* | ||||||||

| Spousal ADL × Social support | −0.21 | 0.30 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal ADL × Number of children | −0.01 | −0.04 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal ADL × Child in household | 0.62 | 0.85* | ||||||||||||

| Spousal ADL × Others in household | −0.31 | −0.18 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal ADL × Social network | −0.69 | −0.11 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal ADL × Church attendance | 0.07 | −0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Socioeconomic resources | ||||||||||||||

| Education | −0.07 | −0.11 | −0.15† | 0.12 | 0.15† | 0.04 | ||||||||

| Income | −0.66 | −0.25 | −1.74* | −0.73 | −0.47 | −1.33† | ||||||||

| Difficulty with bills | −0.56* | −0.33 | −0.75** | −0.70** | −0.47* | −1.09*** | ||||||||

| Health insurance | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.68 | 0.52 | 0.43 | 0.53 | ||||||||

| Spousal ADL × Education | −0.02 | 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal ADL × Income | 1.51** | −0.41 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal ADL × Difficulty with bills | 0.09 | 0.12 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal ADL × Health insurance | 0.13 | −1.11 | ||||||||||||

| Own ADL | 0.91*** | 0.84*** | ||||||||||||

| Spousal depressive symptoms | 0.31*** | 0.39*** | ||||||||||||

| Control variables | ||||||||||||||

| Immigrant | 0.45 | 0.44 | −0.30 | −0.43 | 0.19 | 0.15 | −0.35 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.15 | 0.55 | 0.31 | 0.66 | 0.39 |

| Duration of marriage | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Died | 2.52*** | 2.51*** | 1.79*** | 1.00* | 1.87*** | 2.28*** | 2.59*** | 3.13*** | 3.13*** | 2.24*** | 1.83** | 2.52*** | 2.87*** | 3.09*** |

| Random effects | ||||||||||||||

| Intercept SD | 3.81 | 3.80 | 3.11 | 2.68 | 3.11 | 3.61 | 3.53 | 4.84 | 4.82 | 3.84 | 3.36 | 4.18 | 4.50 | 4.71 |

| Slope (Age) SD | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Residual SD | 6.47 | 6.48 | 6.30 | 5.84 | 6.43 | 6.39 | 6.43 | 6.90 | 6.90 | 6.80 | 6.36 | 6.83 | 6.88 | 6.83 |

| Goodness of fit | ||||||||||||||

| Log likelihood | −4284.77 | −4284.41 | −4217.72 | −4109.70 | −4241.31 | −4260.52 | −4262.45 | −4403.33 | −4403.16 | −4337.77 | −4242.10 | −4360.92 | −4384.35 | −4388.08 |

| df | 9 | 10 | 23 | 25 | 16 | 22 | 18 | 9 | 10 | 23 | 25 | 16 | 22 | 18 |

| AIC | 8587.54 | 8588.81 | 8481.45 | 8269.40 | 8514.62 | 8565.05 | 8560.90 | 8824.66 | 8826.31 | 8721.53 | 8534.21 | 8753.84 | 8812.71 | 8812.15 |

| BIC | 8633.79 | 9640.20 | 8599.64 | 8397.87 | 8596.85 | 8678.10 | 8653.40 | 8870.91 | 8877.70 | 8839.73 | 8662.68 | 8836.06 | 8925.76 | 8904.65 |

Notes. ADL = activities of daily living; AIC = Akaike Information Criterion; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion; H-EPESE = Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. †p < .10.

Table 5.

Results From Adjusted Growth Curve Models Estimating the Impact of Spousal Mobility (POMA) Limitations on the Other Spouse’s Depressive Symptoms Over Time, H-EPESE, 1993–2007 (1,260 Couple Periods)

| Husbands | Wives | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 8.93*** | 11.27*** | 14.26*** | 12.11*** | 13.64*** | 11.38*** | 11.73** | 10.22*** | 11.20*** | 13.72** | 10.24*** | 12.91*** | 10.41*** | 10.77*** |

| Linear slope (Age) | −0.06 | −0.23** | −0.30*** | −0.23** | −0.33*** | −0.25** | −0.24** | −0.08† | −0.18† | −0.30** | −0.29** | −0.26** | −0.24* | −0.13 |

| Spousal POMA | −0.44*** | −0.78*** | −0.71*** | −0.26* | −0.77*** | −0.90** | −0.87* | −0.33*** | −0.46** | −0.46** | −0.13 | −0.52*** | −0.25 | −0.36 |

| Spousal POMA × Age | 0.03* | 0.03** | 0.02* | 0.03** | 0.03** | 0.03** | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02† | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||

| Health | ||||||||||||||

| Cognitive functioning | −0.20*** | −0.13** | −0.38*** | −0.19** | −0.14* | −0.09 | ||||||||

| Self−reported health | −1.37*** | −0.91*** | −1.27* | −1.94*** | −1.43*** | −3.00*** | ||||||||

| Chronic conditions | 0.35† | 0.10 | 0.41 | 0.61* | 0.53* | 0.40 | ||||||||

| Spousal POMA × Cognitive functioning | 0.02 | −0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal POMA × Self-reported health | −0.03 | 0.14 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal POMA × Chronic conditions | −0.01 | 0.03 | ||||||||||||

| Social integration | ||||||||||||||

| Social support | −1.71*** | −1.34*** | −2.44** | −2.14*** | −1.57*** | −2.29* | ||||||||

| Number of kids | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.07 | −0.13 | −0.17* | 0.01 | ||||||||

| Child in household | −0.91† | −0.82† | −0.19 | 0.20 | 0.61 | 1.01 | ||||||||

| Others in household | −0.20 | −0.12 | 0.40 | −0.26 | −0.02 | −3.14† | ||||||||

| Social network | −2.23* | −1.54* | −3.13 | −1.99* | −1.19 | 0.49 | ||||||||

| Church attendance | −0.37* | −0.28† | −1.16** | −0.25 | −0.07 | −0.83* | ||||||||

| Spousal POMA × Social support | 0.09 | 0.02 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal POMA × Number of children | 0.01 | −0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal POMA × Child in household | −0.14 | −0.09 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal POMA × Others in household | −0.07 | 0.38† | ||||||||||||

| Spousal POMA × Social network | 0.23 | −0.28 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal POMA × Church attendance | 0.10* | 0.05 | ||||||||||||

| Socioeconomic resources | ||||||||||||||

| Education | −0.06 | −0.10 | −0.40* | 0.12 | 0.18* | 0.23 | ||||||||

| Income | −0.43 | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.48 | −0.34 | −3.45* | ||||||||

| Difficulty with bills | −0.51* | −0.20 | 0.24 | −0.64** | −0.51* | −0.87 | ||||||||

| Health insurance | 0.37 | 0.45 | −0.39 | 0.46 | 0.35 | −0.19 | ||||||||

| Spousal POMA × Education | 0.04† | −0.02 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal POMA × Income | −0.13 | 0.30† | ||||||||||||

| Spousal POMA × Difficulty with bills | −0.14* | −0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal POMA × Health insurance | 0.15 | 0.03 | ||||||||||||

| Own POMA | −0.54*** | −0.34*** | ||||||||||||

| Spousal depressive symptoms | 0.29*** | 0.37*** | ||||||||||||

| Control variables | ||||||||||||||

| Immigrant | 0.44 | 0.45 | −0.20 | −0.11 | 0.29 | 0.16 | −0.22 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.34 | 0.68 | 0.32 | 0.77 | 0.50 |

| Duration of marriage | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| Died | 2.59*** | 2.54*** | 1.83*** | .84† | 1.93*** | 2.34*** | 2.62*** | 3.05*** | 3.04*** | 2.17*** | 1.81** | 2.42*** | 2.85*** | 2.89*** |

| Random effects | ||||||||||||||

| Intercept SD | 3.71 | 3.72 | 3.07 | 2.47 | 3.10 | 3.59 | 3.51 | 4.68 | 4.64 | 3.66 | 3.23 | 3.96 | 4.32 | 4.54 |

| Slope (Age) SD | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Residual SD | 6.39 | 6.37 | 6.21 | 5.78 | 6.33 | 6.26 | 6.34 | 6.90 | 6.91 | 6.80 | 6.41 | 6.84 | 6.89 | 6.86 |

| Goodness of fit | ||||||||||||||

| Log likelihood | −4265.67 | −4265.33 | −4199.94 | −4086.55 | −4222.96 | −4237.77 | −4246.25 | −4395.52 | −4394.89 | −4330.09 | −4243.61 | −4351.42 | −4376.71 | −4382.54 |

| df | 9 | 10 | 23 | 25 | 16 | 22 | 18 | 9 | 10 | 22 | 25 | 16 | 22 | 18 |

| AIC | 8549.34 | 8544.67 | 8445.87 | 8223.11 | 8477.91 | 8519.56 | 8528.50 | 8809.04 | 8809.78 | 8706.19 | 8537.23 | 8734.84 | 8797.41 | 8801.08 |

| BIC | 8595.59 | 8596.06 | 8564.07 | 8351.58 | 8560.13 | 8632.61 | 8621.00 | 8855.29 | 8861.17 | 8824.38 | 8665.70 | 8817.07 | 8910.47 | 8893.58 |

Notes. AIC = Akaike Information Criterion; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion; H-EPESE = Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly; POMA = performance-oriented mobility assessment.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. †p < .10.

The three measures of functional limitations were highly correlated. Therefore, we conducted growth curve models separately with each of these three measures of the spouse’s functional limitations as an independent variable. All models controlled for immigrant status, duration of marriage, and whether the respondent died during the course of the survey.

Model 1 estimated the direct effect of a particular measure of the spouse’s functional limitations on the respondent’s trajectory of depressive symptoms. In Model 2, we added the interaction term between age and the relevant measure of the spouse’s functional impairment in order to examine whether the effect of the spouse’s functional limitations on the respondent’s depressive symptoms varies with age. To investigate the impact of personal resources on the trajectory of depressive symptoms, Model 3 included the measures of the respondent’s health, social integration, and socioeconomic status. Prior research points to spousal concordance in mental and physical health outcomes between respondents and their spouses in older couples (Meyler et al., 2007; Walker & Luszcz, 2009). Accordingly, the relevant measure of the respondent’s own functional limitations and the measure of the spouse’s depressive symptoms were included in Model 4 to consider their effect on the trajectory of the respondent’s depressive symptoms. Models 5–6 examined whether the impact of the spouse’s functional limitations on the respondent’s depressive symptoms is contingent on the level of the respondent’s resources. The latter models added separately each set of measures of the respondent’s resources in combination with the interaction terms between the relevant measure of the spouse’s functional limitations and these resources. The models were run separately for husbands and wives.

Results from Growth Curve Models

ADL Limitations

Table 3 examines the role of the spouse’s ADL limitations in the age trajectories of depressive symptoms among the respondents. Model 1 for both husbands and wives indicates that the spouse’s ADL limitations are related to more depressive symptoms in the respondent. In Model 2 for both husbands and wives, the nonsignificant interaction terms between the spouse’s ADL limitations and age suggest that the effect of this type of the spouse’s impairments on the respondent’s psychological well-being does not vary by age. However, the effect of the wife’s ADL limitations on the husband’s depressive symptoms becomes nonsignificant.

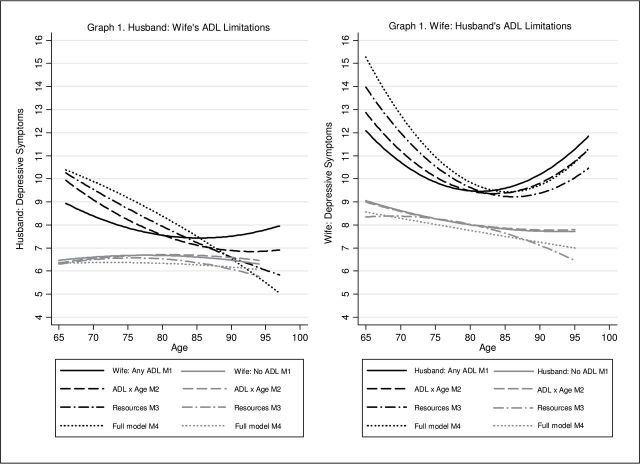

Model 3 presents the results for the age trajectories of depressive symptoms net of respondents’ resources. Regardless of gender, better cognitive functioning, better self-reported health, greater perceived availability of social support from family and friends, having friends and neighbors mostly of Mexican ancestry, and fewer problems with paying monthly bills are associated with fewer depressive symptoms among older adults of Mexican descent. The presence of chronic conditions, however, is related to higher depressive symptomatology only among wives. In contrast, husbands have better psychological well-being if they coreside with adult children or if they attend religious services often. With the inclusion of the respondent’s resources in Model 3, the effect of the wife’s ADL limitations on the husband’s psychological well-being is reduced, whereas the effect of the husband’s impairment on the wife’s depressive symptoms remains practically unchanged. Model 4 demonstrates that with the inclusion of the respondent’s own ADL limitations and the spouse’s depressive symptoms, the adverse effect of the spouse’s ADL limitations on the respondent’s psychological well-being is considerably decreased, regardless of gender. Moreover, this effect on the wife’s mental health is reduced to nonsignificance. On the basis of Models 1–4 in Table 3, Figure 1 shows that the differences in trajectories of depressive symptoms between individuals whose spouses have and do not have ADL limitations are statistically diminished or eliminated with increasing age for husbands, but these differences remain for wives.

Figure 1.

Age trajectories of depressive symptoms: The role of spousal activities of daily living (ADL) limitations and other factors.

Models 5–7 test moderating effects of the respondent’s resources. Model 5 for husbands shows that among men whose wives have more ADL limitations, reporting better health is related to higher levels of depressive symptoms than reporting poorer health. In contrast, there is no evidence to support the contention that the wife’s health measures can make a difference in the associations between her psychological well-being and the husband’s ADL limitations. The interactions of the spouse’s ADL limitations by measures of social integration in Model 6 for husbands are not statistically significant. However, among older women whose spouses have more ADL limitations, coresidence with adult children is related to lower psychological well-being than living in a separate household (Model 6 for wives). Model 7 for husbands indicates that among men whose wives have more ADL limitations, higher income is associated with more depressive symptoms than lower income. At the same time, none of the measures of socioeconomic resources have moderating effects on the associations between the spouse’s ADL limitations and depressive symptoms among wives.

IADL Limitations

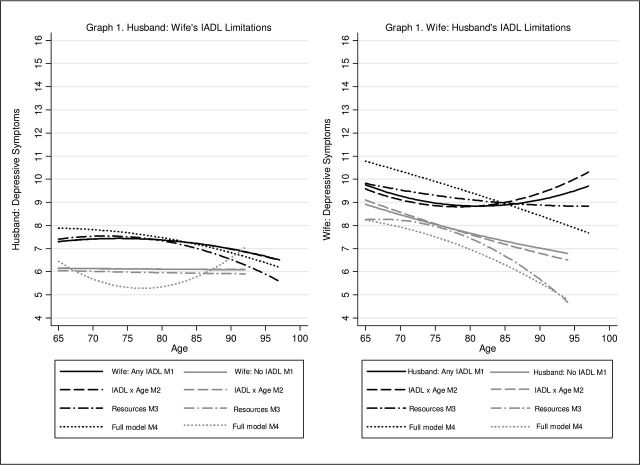

The implications of the spouse’s IADL limitations are presented in Table 4. Model 1 for both husbands and wives demonstrates that the spouse’s IADL limitations predict lower psychological well-being of the respondent. In Model 2, the interactions between the spouse’s IADL limitations and age are not statistically significant. The effect of the spouse’s IADL limitations remains statistically significant in Model 2 for husbands, whereas it is reduced to nonsignificance in Model 2 for wives. Model 3 shows that the same personal resources that were predictive of the respondent’s depressive symptoms in Model 3 in Table 3 for the spouse’s ADL limitations are related to the respondent’s psychological well-being when the spouse’s IADL impairments are taken into account. Also, in Model 3 for husbands, the effect of the spouse’s IADL limitations is reduced to nonsignificance. Consistent with the results for ADL limitations, Model 4 for both husbands and wives indicates that with the inclusion of the respondent’s IADL impairments and the spouse’s depressive symptoms, the adverse effect of the spouse’s IADL limitations is further reduced. On the basis of Models 1–4 in Table 4, Graph 1 in Figure 2 shows that net of personal resources, the differences in trajectories of depressive symptoms between the husbands whose wives have IADL limitations and those whose wives do not have these impairments are reduced with increasing age. In contrast, Graph 2 in Figure 2 demonstrates that the differences in trajectories of psychological well-being between the wives whose spouses have IADL limitations and those whose spouses do not have these impairments are not diminishing with increasing age, even when the respondent’s resources are accounted for.

Table 4.

Results From Growth Curve Models Estimating the Impact of Spousal IADL Limitations on the Other Spouse’s Depressive Symptoms Over Time, H-EPESE, 1993–2007 (1,260 Couple Periods)

| Husbands | Wives | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 5.21*** | 5.20*** | 8.81*** | 5.38*** | 6.93*** | 5.41*** | 3.27* | 7.38*** | 7.58*** | 10.06*** | 6.18*** | 8.91*** | 8.49*** | 6.54*** |

| Linear slope (Age) | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.10* | −0.09* | −0.11* | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.07 | −0.10† | −0.17** | −0.13** | −0.15** | −0.11* | −0.09† |

| Spousal IADL | 0.34*** | 0.34† | 0.20 | −0.05 | 0.30 | 1.00** | 1.48* | 0.25** | 0.09 | 0.02 | −0.25 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.74† |

| Spousal IADL × Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| Health | ||||||||||||||

| Cognitive functioning | −0.20*** | −0.09* | −0.21*** | −0.18** | −0.11* | −0.18** | ||||||||

| Self-reported health | −1.40*** | −0.77** | −1.48*** | −1.91*** | −1.32*** | −1.82*** | ||||||||

| Chronic conditions | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.24 | 0.60* | 0.47* | 0.51† | ||||||||

| Spousal IADL × Cognitive functioning | −0.02 | 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal IADL × Self-reported health | −0.04 | −0.14 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal IADL × Chronic conditions | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||||||||||||

| Social integration | ||||||||||||||

| Social support | −1.74*** | −1.50*** | −1.38** | −2.16*** | −1.45** | −2.49*** | ||||||||

| Number of children | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.17† | −0.14 | −0.17* | 0.01 | ||||||||

| Child in household | −0.94† | −0.81† | −2.04** | 0.08 | 0.51 | −0.13 | ||||||||

| Others in household | −0.36 | −0.43 | −0.11 | −0.46 | −0.12 | −0.54 | ||||||||

| Social network | −2.13* | −1.66* | 0.33 | −1.97* | −0.83 | −1.47 | ||||||||

| Church attendance | −0.40* | −0.23 | −0.51* | −0.25 | −0.05 | −0.34 | ||||||||

| Spousal IADL × Social support | −0.24† | 0.16 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal IADL × Number of children | −0.01 | −0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal IADL × Child in household | 0.46* | 0.19 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal IADL × Others in household | −0.18 | 0.07 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal IADL × Social network | −0.96** | −0.05 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal IADL × Church attendance | −0.01 | −0.07 | ||||||||||||

| Socioeconomic resources | ||||||||||||||

| Education | −0.06 | −0.11† | −0.09 | 0.13 | 0.16* | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Income | −0.59 | −0.16 | −2.37** | −0.77 | −0.44 | −1.54† | ||||||||

| Difficulty with bills | −0.56* | −0.22 | −0.61* | −0.70** | −0.55* | −1.24*** | ||||||||

| Health insurance | 0.41 | 0.43 | 2.22 | 0.67 | 0.09 | 1.78 | ||||||||

| Spousal IADL × Education | −0.04 | 0.03 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal IADL × Income | 0.68** | 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal IADL × Difficulty with bills | −0.04 | 0.14 | ||||||||||||

| Spousal IADL × Health insurance | −1.07† | −0.76* | ||||||||||||

| Own IADL | 0.81*** | 0.58*** | ||||||||||||

| Spousal depressive symptoms | 0.32*** | 0.40*** | ||||||||||||

| Control variables | ||||||||||||||

| Immigrant | 0.35 | 0.35 | −0.33 | −0.36 | 0.13 | 0.06 | −0.36 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.20 | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.67 | 0.37 |

| Duration of marriage | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| Died | 2.51*** | 2.51*** | 1.81*** | 0.55 | 1.89*** | 2.26*** | 2.67*** | 3.09*** | 3.10*** | 2.24*** | 1.67** | 2.52*** | 2.78*** | 3.04*** |

| Random effects | ||||||||||||||

| Intercept SD | 3.75 | 3.75 | 3.12 | 2.72 | 3.13 | 3.57 | 3.56 | 4.81 | 4.85 | 3.90 | 3.27 | 4.20 | 4.57 | 4.76 |

| Slope (Age) SD | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Residual SD | 6.46 | 6.46 | 6.29 | 5.68 | 6.43 | 6.34 | 6.40 | 6.90 | 6.89 | 6.78 | 6.35 | 6.83 | 6.86 | 6.76 |

| Goodness of fit | ||||||||||||||

| Log likelihood | −4276.49 | −4276.49 | −4255.58 | −4078.57 | −4237.67 | −4246.24 | −4255.58 | −4402.81 | −4402.38 | −4338.01 | −4231.67 | −4361.06 | −4385.04 | −4384.74 |

| df | 9 | 10 | 18 | 25 | 15 | 22 | 18 | 9 | 10 | 23 | 25 | 16 | 22 | 18 |

| AIC | 8570.98 | 8572.97 | 8469.05 | 8205.14 | 8507.38 | 8536.48 | 8547.15 | 8823.62 | 8824.76 | 8722.02 | 8513.35 | 8754.13 | 8814.08 | 8805.48 |

| BIC | 8617.22 | 8624.35 | 8582.09 | 8335.59 | 8589.56 | 8649.52 | 8639.64 | 8869.87 | 8876.15 | 8840.21 | 8641.80 | 8836.35 | 8927.13 | 8897.98 |

Notes. IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; AIC = Akaike Information Criterion; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion; H-EPESE = Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. †p < .10.

Figure 2.

Age trajectories of depressive symptoms: The role of spousal instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) limitations and other factors.

Model 5 for both husbands and wives does not provide evidence that personal health measures matter for the associations between the spouse’s IADL limitations and the respondent’s depressive symptoms. Model 6 for husbands demonstrates that some aspects of social integration can make a difference in the psychological well-being of men whose wives have more IADL limitations. For this group of older Mexican American men, greater perceived social support and having friends and neighbors mostly of Mexican ancestry are related to fewer depressive symptoms, whereas coresidence with children is predictive of lower psychological well-being. In contrast, there are no statistically significant interactions between the spouse’s IADL limitations and measures of social integration in Model 6 for wives. Model 7 tests the moderating effects of the respondent’s socioeconomic resources. Among husbands whose wives have more impairments in IADL, higher income is related to greater levels of depressive symptomatology than lower income. Regardless of gender, individuals whose spouses have more IADL limitations report fewer depressive symptoms if they have health insurance.

POMA Limitations

Table 5 presents the results for the spouse’s physical mobility measured by POMA. Higher scores on the measure of POMA indicate better physical functioning. Model 1 shows that better physical mobility of the spouse is related to greater psychological well-being of the respondent, regardless of gender. In Model 2 for husbands, the statistically significant interaction term between the spouse’s POMA limitations and age suggests that the effect of the wife’s POMA limitations on the husband’s psychological well-being varies by age. The interaction between the spouse’s POMA limitations and age is not significant in Model 2 for wives. The effect of the spouse’s POMA limitations in Model 2 for both husbands and wives remains statistically significant.

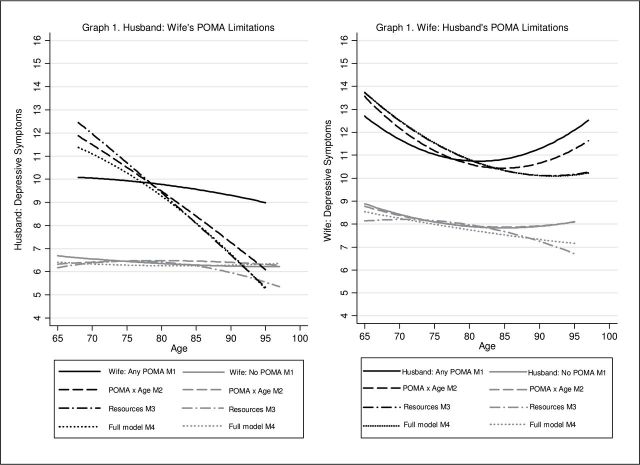

Model 3 for both husbands and wives reveals the importance of the same personal resources that were related to the respondent’s psychological well-being in Model 3 in Tables 3 and 4 for ADL and IADL limitations, respectively. There is one exception, however. More chronic conditions are associated with more depressive symptoms in Model 3 for husbands. With the inclusion of the respondent’s own POMA limitations and the spouse’s depressive symptoms in Model 4, the effect of the spouse’s POMA limitations on the respondent’s psychological well-being is reduced but remains statistically significant for husbands. On the basis of Models 1–4 in Table 5, Figure 3 shows that with increasing age, the spouse’s POMA limitations become less important for the psychological well-being of husbands only, in particular when other factors are taken into account.

Figure 3.

Age trajectories of depressive symptoms: The role of spousal performance-oriented mobility assessment (POMA) limitations and other factors.

Regardless of gender, the interactions between the spouse’s POMA limitations and the respondent’s health measures are not statistically significant in Model 5. Model 6 for husbands demonstrates that more frequent church attendance is related to fewer depressive symptoms among older Mexican American men whose wives have more POMA limitations. Model 6 for wives suggests that among older Mexican American women whose husbands have more POMA impairments, coresidence with others is linked to better psychological well-being. Model 7 for husbands shows that among older men whose wives have more POMA limitations, higher levels of education are related to better mental health, whereas fewer difficulties with paying monthly bills are associated with greater depressive symptomatology. Model 7 for wives indicates that among older women whose husbands have more POMA impairments, higher income is predictive of fewer depressive symptoms than lower income.

A formal test of gender differences including three-way interactions and chi-square tests (not shown) indicated that the strength of associations between the spouse’s functional limitations and the respondent’s age trajectories of depressive symptoms is similar for husbands and wives, regardless of the type of functional impairments.

Discussion

Despite numerous studies on spousal interrelatedness of health outcomes in older couples, the role of personal resources in the association between functional limitations in one spouse and the other spouse’s depressive symptomatology received only limited scholarly attention. This study contributes to a small but growing body of research that has investigated longitudinal patterns of spousal interdependencies in functional impairments and psychological well-being in older couples (Hoppmann et al., 2011; Siegel et al., 2004). This study extends previous work in this area in three major ways: By examining Mexican American couples, by considering a broader range of functional limitations, and by assessing the implications of individuals’ resources for spousal linkages in functional impairments and depressive symptoms. In addition, this study takes into account the role of gender in the interplay among these factors.

Corroborating prior research on spousal associations within and across various dimensions of health in older couples, this study underscores the importance of considering both spouses in the examination of individuals’ physical and psychological health (Ayotte et al., 2010; Stimpson et al., 2007). In particular, consistent with previous studies on other racial/ethnic groups (Hoppmann et al., 2011; Robb et al., 2008; Siegel et al., 2004), the findings of this study demonstrate that in older Mexican American couples, functional limitations in one spouse are related to higher levels of depressive symptoms in the other spouse. Because functional limitations typically require some assistance, caregiving burden can be one of the key plausible explanations for these findings. We did not consider caregiving patterns because this information is not available in the data. Future research in this area would benefit by examining patterns of informal and formal caregiving in older couples.

With one exception, this study indicates that across age groups, individuals whose spouses have more functional limitations persistently report more depressive symptoms than do their counterparts whose spouses have fewer impairments. In other words, the effect of the spouse’s functional limitations on the individual’s mental health does not vary by age. Yet, the adverse effect of wives’ POMA limitations on husbands’ psychological well-being diminishes with increasing age. One possible explanation for the latter finding can include aging expectations regarding health issues in later life. Because physical impairments are more normative at older ages (Covinsky et al., 2009; Fried & Guralnik, 1997; Stineman et al. 2013), they can have a less detrimental effect on individuals’ depressive symptomatology with advancing age. In addition, spousal caregiving patterns can be responsible for this finding. In particular, wives are usually the sole caregivers of functionally disabled husbands, whereas husbands of functionally impaired wives can routinely count on adult children and other relatives for assistance with caregiving tasks (Feld et al., 2010). Furthermore, POMA as an assessment-based measure may not capture individuals’ evaluation of everyday problems related to functional limitations (Coman & Richardson, 2006; Guralnik & Ferrucci, 2003). Individuals may be less aware and, as a result, less vocal about objectively assessed health issues. However, because of gender role socialization and traditional marital roles, women are more likely to recognize their spouse’s decline in well-being even if the latter do not voice any complaints (Barnet & Baruch, 1987). In line with this contention, some prior research indicates that wives are more likely to be affected by their husband’s health than vice versa (Ayotte et al., 2010; Peek et al., 2006).

In addition, the findings show that regardless of gender, better cognitive functioning, better self-reported health, ethnically homogeneous social networks, greater availability of social support, and lower financial strain are predictive of fewer depressive symptoms among older Mexican Americans. More chronic conditions are consistently related to elevated depressive symptomatology only among women, whereas coresidence with adult children and frequent attendance of religious services are beneficial only for husbands’ psychological well-being. Also, regardless of gender, older adults of Mexican descent are at risk for elevated depressive symptomatology if they themselves experience more functional limitations or if their spouses report lower psychological well-being. The findings on the importance of resources are consistent with research on caregivers of older adults indicating that the key factors that explain lower well-being among caregivers are poor health and low social support, including financial assistance (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2011). Furthermore, the present study suggests that when the respondents’ own functional impairments and their spouses’ depressive symptoms are taken into account, the adverse effect of the spouse’s functional limitations is substantially diminished. Another study in this area also indicates that the spouse’s depressive symptoms can mediate the relationship between the spouse’s functional disability and the respondent’s depressive symptoms (Siegel et al., 2004).

This study reveals that higher levels of social integration and socioeconomic resources can weaken the deleterious effect of spousal functional limitations on the other spouse’s psychological well-being. Namely, greater perceived social support and having neighbors and friends mostly of Mexican descent predict better psychological well-being among men whose wives have higher levels of IADL limitations, whereas frequent church attendance serves as a protective factor for those men whose wives have more POMA limitations. These findings are in line with prior research demonstrating that because older men tend to have fewer sources of informal support and weaker social ties than older women, individual differences in social connectedness may be particularly critical for husbands’ mental health when wives experience health issues (Robb et al., 2008; Shumaker & Hill, 1991).

The present research also shows that coresidence with others is beneficial for the psychological well-being of older Mexican American women whose husbands have more POMA limitations. Other people in the household can act as sources of care, support, and companionship (Choi & Bohman, 2007; Smits et al., 2010). Compared with men, women, including Mexican Americans, are less likely to turn to others for formal or informal help with caregiving tasks (Adams et al., 2002; Herrera et al., 2008; Navaie-Waliser et al., 2002). Hence, coresidence can be particularly crucial for the well-being of older women whose spouses have higher levels of functional impairments because additional people in the household can potentially provide immediate relief from caregiving responsibilities without even being asked.

Consistent with prior research on the importance of higher socioeconomic status for older adults’ mental health (Cairney & Krause, 2005; Chiriboga et al. 2002), this study reveals that regardless of gender, availability of health insurance coverage minimizes the adverse implications of higher levels of IADL limitations in one spouse for the psychological well-being of the other spouse. In addition, among individuals whose spouses have more POMA impairments, psychological well-being is enhanced by greater educational attainment among men and by higher income among women. Higher socioeconomic status tends to be linked to greater access to various types of resources and information as well as better problem-solving skills and stress-coping strategies (Feinstein, 1993).

The findings also indicate that some resources can be associated with a stronger detrimental impact of the spouse’s functional decline on the individual’s psychological well-being. Namely, better self-reported health, higher income, and fewer problems with paying monthly bills can be related to lower psychological well-being among men whose wives have higher levels of certain functional limitations than among their counterparts whose wives have lower levels of these limitations. These findings are not necessarily counterintuitive. As discussed earlier, prior research demonstrated that in older couples, decreased social involvement accompanying functional decline in one of the partners can lead to feelings of social isolation and loneliness in both spouses (Hoppman et al., 2008; Korporaal et al., 2008). Restrictions on or lack of engagement in social interactions can be particularly detrimental for mental health of those individuals who cannot take advantage of their own resources, such as good health and sufficient socioeconomic resources, to stay socially active (Manne, Alfieri, Taylor, & Dougherty, 1999). It can be especially true for older men who have to relinquish their plans for getting engaged in specific social and leisure activities after retirement because of their wives’ deteriorating health.

Compared with living in a separate household, coresidence with adult children is linked to lower psychological well-being among women whose husbands have more ADL limitations and among men whose wives have more IADL limitations. Intergenerational households have its benefits and challenges. Coresidence can facilitate exchanges of assistance and caregiving (Choi & Bohman, 2007; Smits et al., 2010). However, aging parents may worry about becoming a burden to their children, despite filial expectations among Mexican Americans that the younger generation should provide care and support to older generations (Johnson, Schwiebert, Alvarado-Rosenmann, Pecka, & Shirk, 1997). Thus, regardless of gender, older adults of Mexican ancestry can experience increased distress when they become more dependent on their children. Moreover, aging parents can face more demands and responsibilities in intergenerational households because they can also be formed in response to the needs of the younger generation (Ward, Logan, & Spitze, 1992). As a result, due to the gendered nature of caregiving, coresidence can be especially disadvantageous for the well-being of older women because they have more responsibilities in these households in addition to caring for their ailing husbands (Ikeda et al., 2009; Michael, Berkman, Colditz, & Kawachi, 2001).

This study has several limitations. We did not examine caregiving patterns, different types of social support (e.g., financial, emotional, and instrumental), and changes in couple’s marital quality, social activities, and social relationships over time because this information was not available in the survey. Also, income, health insurance coverage, and composition of social network were used as time-invariant variables because they were not measured at all the waves.

In spite of its limitations, this study contributes to our understanding of the age patterning in the associations between functional limitations and depressive symptoms in older couples. The findings demonstrate that individuals’ resources such as health, social integration, and socioeconomic status matter for older Mexican Americans’ psychological well-being. Personal resources can both ameliorate and strengthen the adverse implications of the spouse’s functional limitations. The interplay among these factors can vary by gender and the type of the spouse’s functional impairment. The insights from this study suggest that effective interventions for these older couples can include support groups, respite services, information on available formal services, and programs focusing on physical health.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (5 T32 AG000270).

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments on earlier versions of this paper. M. A. Monserud planned the study, conducted the statistical analyses, wrote and revised the paper. M. K. Peek planned the study, helped with the data analysis and interpretation of the findings, and contributed to editing and revising the paper.

References

- Adams B., Aranda M. P., Kemp B., Takagi K. (2002). Ethnic and gender differences in distress among Anglo American, African American, Japanese American, and Mexican American spousal caregivers of persons with dementia. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology, 8, 279–301. :10.1023/A:1019627323558 [Google Scholar]

- Ayotte B. J., Yang F. M., Jones R. N. (2010). Physical health and depression: A dyadic study of chronic health conditions and depressive symptomatology in older couples. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 65, 438–448. :10.1093/geronb/gbq033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnet R. C., Baruch G. K. (1987). Social roles, gender, and psychological distress. In Barnett R. C., Biener L., Baruch G. K. (Eds.), Gender and stress (pp. 122–143). New York, NY: Free Press [Google Scholar]

- Beach S. R., Schulz R., Yee J. L., Jackson S. (2000). Negative and positive health effects of caring for a disabled spouse: Longitudinal findings from the caregiver health effects study. Psychology and Aging, 15, 259–271. :10.1037//0882-7974.15.2.259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman L. F., Glass T. (2000). Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In Berkman L. F., Kawachi I. (Eds.), Social epidemiology (pp. 137–173). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Black S. A., Markides K. S., Miller T. Q. (1998). Correlates of depressive symptomatology among older community dwelling Mexican Americans: The Hispanic EPESE. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 53, 198–208. :10.1093/geronb/53B.4.S198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer D. G. (2003). Depression in late life: Review and commentary. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, 58, 249–265. :10.1093/gerona/58.3.M249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton L. C., Zdaniuk B., Schulz R., Jackson S., Hirsch C. (2003). Transitions in spousal caregiving. The Gerontologist, 43, 230–241. :10.1093/geront/43.2.230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth P., Rodgers B. (2006). Concordance in the mental health of spouses: Analysis of a large national household panel survey. Psychological Medicine, 36, 685–697. :10.1017/S0033291705006677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairney J., Krause N. (2005). The social distribution of psychological distress and depression in older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 17, 807–835. :10.1177/0898264305280985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso F., Pulkovski N., Sprott H., Mannion A. F. (2012). How well do observed functional limitations explain the variance in Roland Morris scores in patients with chronic non-specific low back pain undergoing physiotherapy? European Spine Journal, 21, S187–S195. :10.1007/s00586-012-2255-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiriboga D. A., Black S. A., Aranda M., Markides K. S. (2002). Stress and depressive symptoms among Mexican American elders. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 57, 559–568. :10.1093/geronb/57.6.P559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi N. G., Bohman T. M. (2007). Predicting the changes in depressive symptomatology in later life: How much do changes in health status, marital and caregiving status, work and volunteering, and health-related behaviors contribute? Journal of Aging and Health, 19, 152–177. :10.1177/0898264306297602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coman L., Richardson J. (2006). Relationship between self-report and performance measures of function: A systematic review. Canadian Journal of Aging, 25, 253–270. :10.1353/cja.2007.0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky K. E., Lindquist K., Dunlop D. D., Yelin E. (2009). Pain, functional limitations, and aging. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57, 1556–1561. :10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02388.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djernes J. K. (2006). Prevalence and predictors of depression in populations of elderly: A review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 113, 372–387. :10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00770.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis S. R., Ríos-Vargas M., Albert N. G. (2011). The Hispanic population: 2010. 2010 census briefs. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein J. S. (1993). The relationship between socioeconomic status and health: A review of literature. Milbank Quarterly, 71, 279–322. :10.2307/3350401 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feld S., Dunkle R. E., Schroepfer T., Shen H. W. (2010). Does gender moderate factors associated with whether spouses are the sole providers of IADL care to their partners? Research on Aging, 32, 499–526. :10.1177/0164027510361461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M. F., Folstein S. E., McHugh P. R. (1975). “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12, 189–198. :10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199805)13:5<285::AID-GPS753>3.3.CO;2-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried L. P., Guralnik J. M. (1997). Disability in older adults: Evidence regarding significance, etiology, and risk. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 45, 92–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik J. M., Branch L. G., Cummings S. R. (1989). Physical performance measures in aging research. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, 44, 141–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik J. M., Ferrucci L. (2003). Assessing the building blocks of function: Utilizing measures of functional limitation. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 25, 112–121. :10.1016/S049- 3797(03)00174-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn E. A., Kim G., Chiriboga D. A. (2011). Acculturation and depressive symptoms among Mexican American elders new to the caregiving role: Results from the Hispanic-EPESE. Journal of Aging and Health, 23, 417–432. :10.1177/0898264310380454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera A. P., Lee J., Palos G., Torres-Vigil I. (2008). Cultural influences in the patterns of long-term care use among Mexican American family caregivers. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 27, 141–165. :10.1177/0733464807310682 [Google Scholar]