Abstract

Background

Individual response to medications varies significantly among different populations, and great progress in understanding the molecular basis of drug action has been made in the past 50 years. The field of pharmacogenomics seeks to elucidate inherited differences in drug disposition and effects. While we know that different populations and ethnic groups are genetically heterogeneous, we have not found any pharmacogenomics information regarding minority groups, such as the Tajik ethnic group in northwest China.

Results

We genotyped 85 Very Important Pharmacogene (VIP) variants selected from PharmGKB in 100 unrelated, healthy Tajiks from the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and compared our data with HapMap data from four major populations around the world: Han Chinese (CHB), Japanese in Tokyo (JPT), Utah Residents with Northern and Western European Ancestry (CEU), and Yorubia in Ibadan, Nigeria (YRI). We found that Tajiks differed from CHB, JPT and YRI in 30, 32, and 32 of the selected VIP genotypes respectively (p < 0.005), while differences between Tajiks and CEU were found in only 6 of the genotypes (p < 0.005). Haplotype analysis also demonstrated differences between the Tajiks and the other four populations.

Conclusion

Our results contribute to the pharmacogenomics database of the Tajik ethnic group and provide a theoretical basis for safer drug administration that may be useful for diagnosing and treating disease in this population.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12863-014-0102-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pharmacogenomics, Genetic polymorphism, Haplotype, Tajik, Ethnic difference

Background

To date, pharmacogenomic studies have focused on candidate genes involved in drug pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics. Many of these genes contain functional polymorphisms that are obvious pharmacological choices for investigation in appropriate clinical populations [1,2]. For some drugs, genetic information is important to avoid drug toxicity and to optimize response [2,3]. Pharmacogenomic studies are rapidly elucidating the inherited nature of differences in drug disposition and effects, thereby enhancing drug discovery and providing a stronger scientific basis for optimizing drug therapy on an individual basis [4].

Tajiks are an ethnic group with a worldwide population of 15 to 20 million; they live mostly in Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region [4]. According to the 2010 census, approximately 51,000 Tajiks live in China, mostly in the Tashkurgan Tajik Autonomous County, which is located in the eastern part of the Pamir Plateau.

The Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base (PharmGKB: http://www.pharmgkb.org) is devoted to disseminating primary data and knowledge in pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics and has annotated genes that are important for drug response. This information is presented in the form of Very Important Pharmacogene (VIP) summaries, pathway diagrams, and curated literature [5]. It currently contains information for more than 3000 drugs, 3000 diseases, and 26,000 genes with genotyped variants [4].

We systematically genotyped 85 VIP variants selected from PharmGKB VIP in 100 Tajiks from Xinjiang [6]. We compared genotype frequencies and haplotype construction with those in Han Chinese (CHB), Japanese in Tokyo (JPT), Utah Residents with Northern and Western European Ancestry (CEU), and Yorubia in Ibadan, Nigeria (YRI). Our goals were to identify differences and determine their extent and provide a theoretical basis for safer drug administration and better therapeutic treatment in the Tajik population.

Methods

Ethics statement

All participants recruited and genotyped in the present study had at least three generations of paternal ancestry in their ethnic group, and each subject provided written informed consent. The Ethics Committees of Xinjiang University and Northwest University approved the use of human samples in this study.

Study participants

We recruited a random sample of 100 healthy, unrelated Tajiks (50 males and 50 females) from Tashkurgan Tajik Autonomous County between July and October 2010 using detailed recruitment and exclusion criteria. All of the chosen subjects were Tajik Chinese living in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and DNA sequencing

We successfully genotyped 85 VIP variants in 37 pharmacogenomic genes in 100 participants. Genomic DNA from whole blood was isolated using the GoldMag® nanoparticles method according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and DNA concentration was measured by spectrometry (DU530 UV/VIS spectrophotometer, Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA, USA). We designed primers for amplification and extension reactions using Sequenom MassARRAY Assay Design 3.0 Software [6] and used a Sequenom MassARRAY RS1000 to genotype the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) using the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. Sequenom Typer 4.0 Software was used for data management and analysis [6,7].

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA, USA) and SPSS 16.0 statistical package (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). All p values in this study were two-sided, and p ≤ 0.005 after Bonferroni correction was considered the statistical significance threshold [8]. We calculated and compared the genotype frequencies of Tajiks and four other populations (CHB, JPT, CEU, and YRI) using chi-squared tests [9]. We used the Haploview software package (version 4.2) for analysis of linkage disequilibrium (LD), haplotype construction, and genetic associations at polymorphic loci [10-12]. Our method excluded SNPs with minor allele frequency < 0.001 for SNPs with lower frequencies that have little power to detect LD. We also ignored SNPs with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) p values < 0.001 for their small probability that their deviation from HWE could be explained by chance. The D’ values on the square is a measure of the LD extent for each pair of SNPs, squares in red without D’ values indicate the two sites are in complete LD (D’ = 1). We constructed haplotypes using the common sites of the selected SNPs and sites downloaded from HapMap for the VDR gene and derived the haplotype frequencies in all five populations.

Results

We successfully sequenced 85 VIP pharmacogenomic variant genotypes from 100 Tajiks. The PCR primers used for the selected variants are listed in Additional file 1. Table 1 lists the basic characteristics of the selected variants, including gene name, chromosome number and position, and their allele frequencies in Tajiks.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the selected variants

| SNP ID | Genes | Chromosome | Position | Allele | Allele frequencies | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | A(%) | B(%) | ||||

| rs1801131 | MTHFR | 1 | 11854476 | C | A | 35.0 | 65.0 |

| rs1801133 | MTHFR | 1 | 11856378 | T | C | 19.2 | 80.8 |

| rs890293 | CYP2J2 | 1 | 60392494 | G | T | 48.5 | 51.5 |

| rs3918290 | DPYD | 1 | 97915614 | G | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs6025 | F5 | 1 | 169519049 | C | A | 100 | 0 |

| rs20417 | PTGS2 | 1 | 186650320 | G | C | 97.0 | 3.0 |

| rs689466 | PTGS2 | 1 | 186650750 | A | G | 85.4 | 14.7 |

| rs4124874 | UGT1A10 | 2 | 234665659 | C | A | 42.8 | 57.2 |

| rs10929302 | UGT1A10 | 2 | 234665782 | G | A | 73.5 | 26.5 |

| rs4148323 | UGT1A10 | 2 | 234669144 | A | G | 3.5 | 96.5 |

| rs7626962 | SCN5A | 3 | 38620907 | G | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs1805124 | SCN5A | 3 | 38645420 | G | A | 29.0 | 71.0 |

| rs6791924 | SCN5A | 3 | 38674699 | G | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs3814055 | NR1I2 | 3 | 119500034 | C | T | 58.0 | 42.0 |

| rs2046934 | P2RY12 | 3 | 151057642 | T | C | 90.0 | 10.0 |

| rs1065776 | P2RY1 | 3 | 152553628 | T | C | 6.1 | 93.9 |

| rs701265 | P2RY1 | 3 | 152554357 | G | A | 20.0 | 80.0 |

| rs975833 | ADH1A | 4 | 100201739 | G | C | 74.2 | 25.8 |

| rs2066702 | ADH1B | 4 | 100229017 | C | T | 97.5 | 2.5 |

| rs1229984 | ADH1B | 4 | 100239319 | G | A | 70.5 | 29.5 |

| rs698 | ADH1C | 4 | 100260789 | A | G | 67.0 | 33.0 |

| rs17244841 | HMGCR | 5 | 74607099 | A | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs3846662 | HMGCR | 5 | 74615328 | T | C | 48.5 | 51.5 |

| rs17238540 | HMGCR | 5 | 74619742 | T | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs1042713 | ADRB2 | 5 | 148206440 | G | A | 60.5 | 39.5 |

| rs1042714 | ADRB2 | 5 | 148206473 | G | C | 34.0 | 66.0 |

| rs1800888 | ADRB2 | 5 | 148206885 | C | T | 98.0 | 2.0 |

| rs1142345 | TPMT | 6 | 18130918 | G | A | 0 | 100 |

| rs1800460 | TPMT | 6 | 18139228 | A | G | 0 | 100 |

| rs2066853 | AHR | 7 | 17379110 | G | A | 82.5 | 17.5 |

| rs1045642 | ABCB1 | 7 | 87138645 | T | C | 57.1 | 42.9 |

| rs2032582 | ABCB1 | 7 | 87160617 | G | T | 42.7 | 57.3 |

| rs2032582 | ABCB1 | 7 | 87160617 | G | A | 86.4 | 13.6 |

| rs2032582 | ABCB1 | 7 | 87160617 | T | A | 92.7 | 7.4 |

| rs1128503 | ABCB1 | 7 | 87179601 | T | C | 58.1 | 41.9 |

| rs10264272 | CYP3A5 | 7 | 99262835 | C | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs776746 | CYP3A5 | 7 | 99270539 | G | A | 89.5 | 10.5 |

| rs4986913 | CYP3A4 | 7 | 99358459 | C | T | 99.0 | 1.0 |

| rs4986910 | CYP3A4 | 7 | 99358524 | T | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs4986909 | CYP3A4 | 7 | 99359670 | C | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs12721634 | CYP3A4 | 7 | 99381661 | T | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs2740574 | CYP3A4 | 7 | 99382096 | A | G | 98.5 | 1.5 |

| rs3815459 | KCNH2 | 7 | 150644394 | A | G | 40.5 | 59.5 |

| rs36210421 | KCNH2 | 7 | 150644428 | G | T | 99.0 | 1.0 |

| rs12720441 | KCNH2 | 7 | 150647304 | C | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs3807375 | KCNH2 | 7 | 150667210 | A | G | 43.0 | 57.0 |

| rs4986893 | CYP2C19 | 10 | 96540410 | G | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs4244285 | CYP2C19 | 10 | 96541616 | G | A | 92.5 | 7.5 |

| rs1799853 | CYP2C9 | 10 | 96702047 | C | T | 100 | 0 |

| rs1801252 | ADRB1 | 10 | 115804036 | G | A | 20.2 | 79.8 |

| rs1801253 | ADRB1 | 10 | 115805055 | C | G | 79.8 | 20.2 |

| rs5219 | KCNJ11 | 11 | 17409572 | C | T | 56.1 | 43.9 |

| rs1695 | GSTP1 | 11 | 67352689 | A | G | 77.0 | 23.0 |

| rs1138272 | GSTP1 | 11 | 67353579 | T | C | 9.0 | 91.0 |

| rs1800497 | DRD2 | 11 | 113270828 | T | C | 17.9 | 82.1 |

| rs6277 | DRD2 | 11 | 113283459 | G | A | 61.5 | 38.5 |

| rs4149056 | SLCO1B1 | 12 | 21331549 | T | C | 90.5 | 9.5 |

| rs7975232 | VDR | 12 | 48238837 | C | A | 49.0 | 51.0 |

| rs1544410 | VDR | 12 | 48239835 | G | A | 66.0 | 34.0 |

| rs2239185 | VDR | 12 | 48244559 | T | C | 51.0 | 49.0 |

| rs1540339 | VDR | 12 | 48257326 | G | A | 67.2 | 32.8 |

| rs2239179 | VDR | 12 | 48257766 | A | G | 56.5 | 43.5 |

| rs3782905 | VDR | 12 | 48266167 | C | G | 70.0 | 30.0 |

| rs2228570 | VDR | 12 | 48272895 | T | C | 34.5 | 65.5 |

| rs10735810 | VDR | 12 | 48272895 | C | T | 66.5 | 33.5 |

| rs11568820 | VDR | 12 | 48302545 | G | A | 77.3 | 22.7 |

| rs1801030 | SULT1A2 | 16 | 28617485 | A | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs3760091 | SULT1A1 | 16 | 28620800 | C | G | 54.1 | 45.9 |

| rs7294 | VKORC1 | 16 | 31102321 | C | T | 67.0 | 33.0 |

| rs9934438 | VKORC1 | 16 | 31104878 | G | A | 50.5 | 49.5 |

| rs28399454 | CYP2A6 | 19 | 41351267 | G | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs28399444 | CYP2A6 | 19 | 41354190 | A | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs1801272 | CYP2A6 | 19 | 41354533 | T | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs28399433 | CYP2A6 | 19 | 41356379 | G | T | 10.5 | 89.5 |

| rs3745274 | CYP2B6 | 19 | 41512841 | G | T | 64.0 | 36.0 |

| rs28399499 | CYP2B6 | 19 | 41518221 | T | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs3211371 | CYP2B6 | 19 | 41522715 | C | T | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| rs12659 | SLC19A1 | 21 | 46951555 | C | T | 56.6 | 43.4 |

| rs1051266 | SLC19A1 | 21 | 46957794 | G | A | 55.7 | 44.3 |

| rs1131596 | SLC19A1 | 21 | 46957915 | T | C | 60.6 | 39.4 |

| rs4680 | COMT | 22 | 19951271 | A | G | 53.5 | 46.5 |

| rs59421388 | CYP2D6 | 22 | 42523610 | C | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs28371725 | CYP2D6 | 22 | 42523805 | G | A | 90.0 | 10.0 |

| rs16947 | CYP2D6 | 22 | 42523943 | G | A | 74.1 | 25.9 |

| rs5030656 | CYP2D6 | 22 | 42524175 | AAG | delAAG | 99.5 | 0.5 |

| rs61736512 | CYP2D6 | 22 | 42525134 | C | / | 100 | 0 |

| rs28371706 | CYP2D6 | 22 | 42525772 | C | T | 99.0 | 1.0 |

Table 2 lists the genotype frequencies in Tajiks and identifies significant variants in Tajiks compared with the other four populations (p < 0.005), all variant data are shown in Additional file 2. We also categorized the genes into different families and phases related to pharmacogenomics, the statistically significant values are shown in red (p < 0.05). We found that Tajiks differed from CHB, JPT, and YRI in 30, 32, and 32 selected VIP genotypes, respectively. These genes encode phase I drug metabolic enzymes (VCORC1, MTHFR, and CYP3A5), a phase II drug metabolic enzymes (COMT), and transporters, channel proteins, and receptors (e.g., ADRB1, KCNH2, and VDR, respectively). However, the difference between Tajiks and CEU was much smaller; just six SNP genotypes were different, and these were randomly distributed on genes such as CYP2C9, which encodes a phase I enzyme. For genes such as ADH1B and PTGS2, we observed differences between Tajiks and the other four populations.

Table 2.

Genotype frequencies in Tajiks compared with four other populations

| SNP ID | Gene | Category | Allele | Tajik genotype frequencies | p values against four populations (after Bonferroni correction) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Phase | A | B | AA(%) | AB(%) | BB(%) | CHB | JPT | CEU | YRI | ||

| rs1045642 | ABCB1 | ABC transporters | others | T | C | 34.3 | 45.5 | 20.2 | 8.49E-03 | 3.42E-02 | 3.10E-01 | 2.17E-18 |

| rs1128503 | ABCB1 | ABC transporters | others | T | C | 32.3 | 51.5 | 16.2 | 3.09E-02 | 8.73E-01 | 1.69E-02 | 3.03E-19 |

| rs2032582 | ABCB1 | ABC transporters | others | G | T | 18 | 49.4 | 32.6 | 9.02E-01 | 6.07E-01 | 8.24E-02 | - |

| rs975833 | ADH1A | alcohol dehydrogenase | phase I | G | C | 55.6 | 37.4 | 7.1 | 4.86E-16 | 3.45E-14 | 6.46E-01 | 5.79E-01 |

| rs1229984 | ADH1B | alcohol dehydrogenase | phase I | G | A | 48 | 45 | 7 | 3.76E-12 | 7.23E-11 | 9.18E-11 | 1.26E-10 |

| rs2066702 | ADH1B | alcohol dehydrogenase | phase I | C | T | 95 | 5.1 | 0 | 2.97E-01 | 2.97E-01 | 1.94E-01 | 1.61E-11 |

| rs698 | ADH1C | alcohol dehydrogenase | phase I | A | G | 44.3 | 45.4 | 10.3 | 1.21E-09 | 3.22E-09 | 1.24E-02 | 7.40E-11 |

| rs1801252 | ADRB1 | adrenergic receptors | others | G | A | 3 | 34.3 | 62.6 | 1.22E-05 | 1.52E-05 | - | 2.53E-06 |

| rs1801253 | ADRB1 | adrenergic receptors | others | C | G | 63.6 | 32.3 | 4 | 6.12E-01 | 3.88E-01 | 5.87E-02 | 4.12E-04 |

| rs1042713 | ADRB2 | adrenergic receptors | others | G | A | 36 | 49 | 15 | 4.49E-03 | 5.67E-01 | 7.34E-01 | 6.05E-02 |

| rs1042714 | ADRB2 | adrenergic receptors | others | G | C | 14 | 40 | 46 | 1.26E-03 | 3.39E-05 | 2.70E-02 | 9.85E-03 |

| rs2066853 | AHR | AHR | others | G | A | 69 | 27 | 4 | 1.18E-05 | 7.65E-08 | 6.87E-02 | 9.06E-08 |

| rs4680 | COMT | COMT | phase II | A | G | 31 | 45 | 24 | 9.95E-05 | 1.56E-05 | 5.25E-01 | 3.15E-05 |

| rs28399454 | CYP2A6 | cytochrome P450 | phase I | G | / | 100 | 0 | 0 | - | - | 1.00E + 00 | 7.81E-07 |

| rs3745274 | CYP2B6 | cytochrome P450 | phase I | G | T | 46 | 36 | 18 | 1.07E-03 | 2.03E-03 | 5.17E-02 | 1.50E-01 |

| rs28399499 | CYP2B6 | cytochrome P450 | phase I | T | / | 100 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | 2.04E-06 |

| rs4244285 | CYP2C19 | cytochrome P450 | phase I | G | A | 85 | 15 | 0 | 1.00E-03 | 1.56E-05 | 4.07E-02 | 8.50E-02 |

| rs1799853 | CYP2C9 | cytochrome P450 | phase I | C | T | 100 | 0 | 0 | - | - | 6.25E-05 | - |

| rs776746 | CYP3A5 | cytochrome P450 | phase I | G | A | 81 | 17 | 2 | 2.78E-05 | 8.74E-05 | 2.58E-02 | 1.23E-34 |

| rs10264272 | CYP3A5 | cytochrome P450 | phase I | C | / | 100 | 0 | 0 | 1.00E + 00 | 1.00E + 00 | - | 8.95E-09 |

| rs6277 | DRD2 | G-protein-coupled receptor | others | G | A | 38 | 47 | 15 | 7.41E-08 | 1.01E-07 | 1.98E-02 | 6.51E-11 |

| rs1800497 | DRD2 | G-protein-coupled receptor | others | T | C | 3.1 | 29.6 | 67.4 | 8.59E-06 | 1.43E-05 | 7.19E-01 | 2.25E-06 |

| rs1695 | GSTP1 | glutathione S-transferase | phase II | A | G | 59 | 36 | 5 | 5.70E-01 | 1.96E-03 | 2.32E-04 | 1.50E-03 |

| rs1138272 | GSTP1 | glutathione S-transferase | phase II | T | C | 0 | 18 | 82 | 3.00E-03 | 2.00E-03 | 9.22E-01 | 2.28E-03 |

| rs3846662 | HMGCR | HMGCR | phase I | T | C | 18 | 61 | 21 | 2.49E-01 | 7.26E-01 | 2.12E-02 | 2.79E-24 |

| rs3807375 | KCNH2 | eag | others | A | G | 19 | 48 | 33 | 6.73E-07 | 8.34E-12 | 4.02E-01 | 1.13E-11 |

| rs3815459 | KCNH2 | eag | others | A | G | 16 | 49 | 35 | 6.04E-06 | 2.69E-09 | - | 6.88E-01 |

| rs1801131 | MTHFR | methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase | phase I | C | A | 7 | 56 | 37 | 9.07E-03 | 5.46E-04 | 2.32E-01 | 7.36E-09 |

| rs1801133 | MTHFR | methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase | phase I | T | C | 4 | 30.3 | 65.7 | 3.13E-07 | 1.21E-03 | 1.92E-02 | 9.34E-03 |

| rs3814055 | NR1I2 | nuclear receptor | others | C | T | 30 | 56 | 14 | 8.60E-03 | 2.15E-03 | 1.00E-01 | 1.32E-03 |

| rs701265 | P2RY1 | G-protein coupled receptor | others | G | A | 4 | 32 | 64 | 7.61E-02 | 3.04E-01 | 9.33E-01 | 2.96E-25 |

| rs2046934 | P2RY12 | G-protein coupled receptor | others | T | C | 82 | 16 | 2 | 5.69E-02 | 4.97E-02 | 4.49E-03 | 6.23E-03 |

| rs20417 | PTGS2 | nuclear receptor | others | G | C | 97 | 0 | 3 | 5.43E-04 | 1.57E-03 | 3.65E-07 | 4.82E-17 |

| rs689466 | PTGS2 | nuclear receptor | others | A | G | 73.7 | 23.2 | 3 | 3.68E-11 | 4.34E-07 | 7.13E-01 | 1.12E-01 |

| rs1805124 | SCN5A | sodium channel gene | others | G | A | 9 | 40 | 51 | 1.23E-04 | 7.59E-04 | 7.80E-03 | 4.96E-01 |

| rs6791924 | SCN5A | sodium channel gene | others | G | / | 100 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | 2.00E-03 |

| rs7626962 | SCN5A | sodium channel gene | others | G | / | 100 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | 1.24E-03 |

| rs1051266 | SLC19A1 | solute carrier | others | G | A | 29.9 | 51.6 | 18.6 | 3.65E-01 | 8.28E-02 | 8.36E-01 | 2.83E-06 |

| rs4149056 | SLCO1B1 | solute carrier | others | T | C | 82 | 17 | 1 | 2.30E-01 | 7.68E-01 | 1.47E-01 | 2.66E-04 |

| rs4124874 | UGT1A10 | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase | phase II | C | A | 14.4 | 56.7 | 28.9 | 1.64E-02 | 6.88E-02 | 3.31E-01 | 2.73E-23 |

| rs4148323 | UGT1A10 | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase | phase II | A | G | 0 | 7 | 93 | 7.23E-08 | 3.22E-03 | 9.00E-02 | 9.00E-02 |

| rs10929302 | UGT1A10 | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase | phase II | G | A | 53 | 41 | 6 | 2.58E-03 | 3.31E-03 | 9.38E-01 | 4.91E-02 |

| rs1540339 | VDR | nuclear receptor | others | G | A | 47.5 | 39.4 | 13.1 | 1.60E-10 | 1.42E-11 | 7.78E-01 | 1.80E-02 |

| rs1544410 | VDR | nuclear receptor | others | G | A | 40 | 52 | 8 | 3.05E-12 | 2.03E-06 | 1.75E-02 | 2.50E-01 |

| rs2239179 | VDR | nuclear receptor | others | A | G | 31 | 51 | 18 | 4.01E-04 | 6.14E-05 | 3.63E-02 | 8.58E-03 |

| rs2239185 | VDR | nuclear receptor | others | T | C | 22 | 58 | 20 | 2.86E-04 | 1.55E-01 | - | 4.37E-01 |

| rs3782905 | VDR | nuclear receptor | others | C | G | 46 | 48 | 6 | 1.20E-01 | 6.72E-04 | 3.92E-01 | 7.74E-02 |

| rs7975232 | VDR | nuclear receptor | others | C | A | 20 | 58 | 22 | 9.30E-05 | 2.13E-03 | 1.92E-02 | 2.44E-02 |

| rs10735810 | VDR | nuclear receptor | others | C | T | 48.4 | 36.3 | 15.4 | 8.17E-02 | 8.74E-01 | 2.72E-01 | 4.64E-03 |

| rs11568820 | VDR | nuclear receptor | others | G | A | 60.6 | 33.3 | 6.1 | 1.12E-04 | 4.25E-05 | 6.86E-01 | 8.35E-38 |

| rs7294 | VKORC1 | VKORC1 | phase I | C | T | 44 | 46 | 10 | 8.00E-10 | 1.09E-06 | 7.69E-01 | 1.59E-04 |

| rs9934438 | VKORC1 | VKORC1 | phase I | G | A | 26 | 49 | 25 | 1.29E-17 | 4.64E-14 | 1.01E-01 | 9.39E-25 |

We counted the variants in each family, excluding those that belonged to none of the families or were not significantly different between Tajiks and the other four populations. The remaining 71 sites belonged to 26 genes in 12 families (Table 3). We found that the difference between Tajiks and CEU existed in only one site in the nuclear receptor family and 0 site in adrenergic receptors family respectively. However, in the nuclear receptor family, Tajiks differed from CHB, JPT, and YRI in 66.7%, 75%, and 33.3% of selected sites, respectively. In the adrenergic receptor family, Tajiks differed from CHB, JPT, and YRI in 60%, 40%, and 40% of selected sites, respectively. For genes in ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, Tajiks differed from YRI in 66.7% of the selected sites, but there was no difference between Tajiks and CHB, JPT, CEU.

Table 3.

Numbers and frequencies of significant variants

| Family | Variants (n) | Significant variants, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHB | JPT | CEU | YRI | ||

| Adrenergic receptors | 5 | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (40.0) |

| Alcohol dehydrogenase | 4 | 3 (75.0) | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) |

| ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters | 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (66.7) |

| Cytochrome P450 | 24 | 3 (24.9) | 3 (24.9) | 1 (8.3) | 4 (16.7) |

| Eag | 4 | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.0) |

| Glutathione S-transferase | 2 | 1 (50.0) | 2 (100) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (100) |

| G-protein coupled receptor | 5 | 2 (40.0) | 2 (40.0) | 1 (20.0) | 3 (60.0) |

| Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase | 2 | 1 (50.0) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50.0) |

| Nuclear receptor | 12 | 8 (66.7) | 9 (75.0) | 1 (8.3) 0) |

4 (33.3) |

| Sodium channel gene | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (66.7) |

| Solute carrier | 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (50.0) |

| UDP-glucuronosyltransferase | 3 | 2 (33.7) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) |

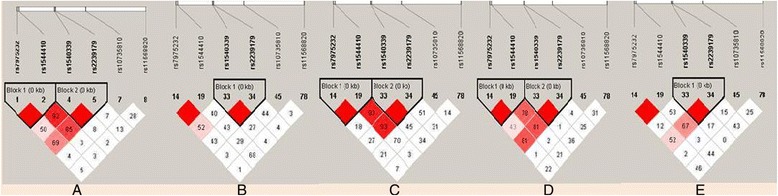

We performed LD analysis using Haploview to define blocks and haplotypes. Using the common sites of our study and those from HapMap in the VDR gene, we identified two LD blocks in Tajiks, JPT, and CEU and one LD block in CHB and YRI (Figure 1). The block identified in all five populations spans 0.4 kb and consists of two complete LD markers (rs1540339 and rs2239179) with a D’ value equal to 1. The block identified in Tajiks, JPT, and CEU spans 0.9 kb and also consists of two complete LD markers (rs7975232 and rs1544410) with a D’ value equal to 1.

Figure 1.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis of VDR in five populations. LD is displayed by standard color schemes, with bright red for very strong LD (LOD > 2, D’ = 1), light red (LOD > 2, D’ < 1) and blue (LOD < 2, D’ = 1) for intermediate LD, and white (LOD < 2, D’ < 1) for no LD. A. Tajiks, B. CHB, C. JPT, D. CEU, E. YRI.

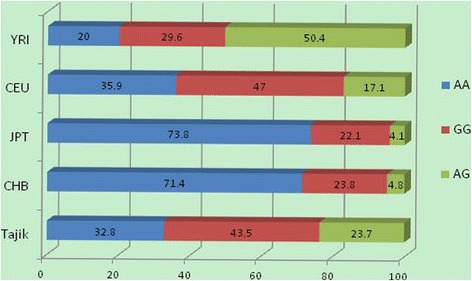

Haplotype analysis results are shown in Figure 2. For the common block comprised of rs1540339 and rs2239179, three kinds of haplotypes were identified in all five populations, but they differed in frequency. Three colors of bars indicate the three kinds of haplotypes. The highest and lowest frequencies of haplotype “AA” were found in JPT (73.8%) and YRI (20.0%). The highest and lowest frequencies of haplotype “GG” were observed in CEU (47.0%) and JPT (22.1%). The highest and lowest frequencies of haplotype “GA” were found in YRI (50.4%) and JPT (4.1%). The haplotype constitutions and frequencies show that there are relatively minimal differences between Tajik and CEU, CHB, and JPT, whereas the differences between YRI and the other four populations seem obvious. These findings are in accordance with the results shown in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Haplotype analysis results of rs1540339 and rs2239179 in VDR .

Discussion

With the rapid development of pharmacogenetics, serious attention has been given to interethnic and interracial differences in drug responses [13]. Here, we genotyped 85 variants related to pharmacogenomics in the Tajik ethnic group for the first time and compared the results with other ethnic populations around the world. We found that 30, 32, 32, and 6 VIP variants differed from CHB, JPT, YRI, and CEU respectively (p < 0.005). These findings corroborate the current opinion that polymorphisms with varying frequencies occur among different populations.

Vitamin D receptor (VDR) is a gene whose function has been widely reported. Epithelial cells convert the primary circulating form of vitamin D to its active form, which binds VDR to regulate a variety of genes that keep cellular proliferation and differentiation within normal ranges to prevent malignant transformation [14]. That is to say, the active form of vitamin D can induce apoptosis and prevent angiogenesis by binding VDR, which reduces the survival potential of malignant cells. Studies have demonstrated that rs10735810 and rs1544410 SNPs in VDR might modulate the risk of breast, skin, and prostate cancers, as well as other forms [15,16]. An Italian study reported that GA and AA rs1544410 genotypes were associated with decreased cutaneous malignant melanoma (CMM) risk (odds ratio = 0.78 and 0.75, respectively) compared with the GG genotype [16]. A study in Japan found that head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients with the TT rs10735810 genotype was associated with poor progression-free survival compared with CC or CT genotype patients (log-rank test, p = 0.0004; adjusted hazard ratio, 3.03; 95% confidence interval, 1.62 to 5.67; p = 0.001), and the A-T-G (rs11568820-rs10735810-rs7976091) haplotype showed a significant association with a higher progression rate (p = 0.02). [14] We found that the GA and AA genotype frequencies of rs1544410 in Tajiks were as much as 52% and 8% respectively, which is different from those in CHB and JPT (data not shown), suggesting that Tajiks may have decreased susceptibility to CMM.

The gene alcohol dehydrogenase 1B (ADH1B) produces a key protein for alcohol metabolism that determines blood acetaldehyde concentrations after drinking [17]. This member of the alcohol dehydrogenase family also metabolizes a wide variety of substrates besides ethanol, including retinol, other aliphatic alcohols, hydroxysteroids, and lipid peroxidation products. The minor allele “A” of rs1229984 encodes a super-active allozyme that is reportedly associated with lower rates of alcohol dependence in numerous association studies, and its frequency varies widely across different populations. It is 69% (19-91%) in normal Asian normal populations, 5.5% (1-43%) in normal European populations, and just 3% (2-7%) in normal Mexican populations [18]. Other studies have shown that rs1229984 may influence alcohol consumption behavior and is associated with upper aerodigestive (UADT) cancers [19-24]. A genome-wide association study found that the “A” allele of rs1229984 was associated with decreased UADT risk (p = 7 × 10−9) [19]. The data in our study is in accordance with previous findings; we found that the “A” allele frequency of rs1544410 in Tajiks was 29.5%, which was significantly different (p < 0.05) from 76.67%, 73.86%, 0%, and 0% in CHB, JPT, CEU, and YRI respectively, suggesting that Tajiks have an intermediate susceptibility to UADT cancer.

The catechol-o-methyltransferase gene (COMT) is responsible for eliminating dopamine from the synaptic cleft in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) [25]. Variations in the COMT gene exert complex effects on susceptibility to depression through various intermediate phenotypes, such as impulsivity and executive function [26]. The common functional COMT polymorphism rs4680 has been shown to affect enzyme activity and, consequently, intrasynaptic dopamine content. The “G” allele is associated with 40% higher enzymatic activity in the human brain compared to the “A” allele, leading to more efficient elimination of dopamine from the synaptic cleft; therefore, the GG genotype is associated with reduced synaptic dopamine in the PFC, and in turn, more active striatal dopamine neurotransmission [25,27-29]. A study in northern Italy reported an association between the GG genotype and the risks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and its precursor, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [30]. The GG genotype frequency in our study was just 24% in Tajiks, compared with 51.2%, 50%, and 46% in CHB, JPT, and YRI respectively (p < 0.05). This suggests that Tajiks may be less vulnerable to diseases related to dopamine content, including AD and MCI.

Our study also found significant differences in genotype frequencies between Tajiks and other populations in genes such as DRD2 and F5. Polymorphisms in these genes have been shown to be associated with dyskinesia induced by levodopa therapy in Parkinson’s disease patients and coronary artery disease, respectively [31,32].

The Tajiks speak a western Indo-Iranian language and their presence in China dates to the 10th-century Muslim invasion, suggesting they are descendants of eastern Indo-Iranian speakers [33]. This may explain the smaller differences between Tajiks and CEU compared to other three populations we investigated.

However, intrinsic limitations still exist in our study. Our sample size is relatively not big enough, thus further investigation related to pharmacogenomics gene polymorphisms in a larger Tajik population is necessary to ascertain the results obtained in the current study.

Conclusions

These results provide the first pharmacogenomics information in Tajiks and illustrate the difference of selected genes between Tajiks and four other populations. Present-day China is a nation with 56 distinct ethnic groups. Our study provides a theoretical basis for safer drug administration and better therapeutic treatments in this unique population, and may also be applied in the diagnosis and prognosis of specific diseases in Tajiks.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National 863 High-Technology Research and Development Program (No. 2012AA02A519).

Additional files

PCR primers for the selected variants.

Genotype frequencies in Tajiks compared with four other populations.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. No conflict of interest exits in the submission of this manuscript, and manuscript is approved by all authors for publication. I would like to declare on behalf of my co-authors that the work described was original research that has not been published previously, and not under consideration for publication elsewhere, in whole or in part. All the authors listed have approved the manuscript that is enclosed.

Authors’ contributions

JZ and TJ designed the study, carried out the molecular genetic studies, and participated in the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. ZY and XL participated in molecular genetic studies and statistical analysis. TG and HG participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. YC conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. CC conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination, and funded the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Jiayi Zhang and Tianbo Jin joint first authors.

Contributor Information

Jiayi Zhang, Email: jiayi0313_com@163.com.

Tianbo Jin, Email: jintianbo@gamil.com.

Zulfiya Yunus, Email: zulfiya_yunus@163.com.

Xiaolan Li, Email: 392310535@qq.com.

Tingting Geng, Email: 24057967@qq.com.

Hong Wang, Email: 26005572@qq.com.

Yali Cui, Email: yalicui@nwu.edu.cn.

Chao Chen, Email: cchen898@nwu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Roden DM, Altman RB, Benowitz NL, Flockhart DA, Giacomini KM, Johnson JA, Krauss RM, McLeod HL, Ratain MJ, Relling MV, Ring HZ, Shuldiner AR, Weinshilboum RM, Weiss ST. Pharmacogenomics: challenges and opportunities. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:749–757. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinshilboum R. Inheritance and drug response. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:529–537. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans WE, McLeod HL. Pharmacogenomics–drug disposition, drug targets, and side effects. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:538–549. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans WE, Relling MV. Pharmacogenomics: translating functional genomics into rational therapeutics. Science. 1999;286:487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sangkuhl K, Berlin DS, Altman RB, Klein TE. PharmGKB: understanding the effects of individual genetic variants. Drug Metab Rev. 2008;40:539–551. doi: 10.1080/03602530802413338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabriel S, Ziaugra L, Tabbaa D. SNP genotyping using the Sequenom MassARRAY iPLEX platform. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2009;Chapter 2:Unit 2 12. doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg0212s60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas RK, Baker AC, Debiasi RM, Winckler W, Laframboise T, Lin WM, Wang M, Feng W, Zander T, MacConaill L, Lee JC, Nicoletti R, Hatton C, Goyette M, Girard L, Majmudar K, Ziaugra L, Wong KK, Gabriel S, Beroukhim R, Peyton M, Barretina J, Dutt A, Emery C, Greulich H, Shah K, Sasaki H, Gazdar A, Minna J, Armstrong SA, et al. High-throughput oncogene mutation profiling in human cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:347–351. doi: 10.1038/ng1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song MK, Lin FC, Ward SE, Fine JP. Composite variables: when and how. Nurs Res. 2012;62:45–49. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182741948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adamec C. Example of the use of the nonparametric test. Test X2 for comparison of 2 independent examples. Cesk Zdrav. 1964;12:613–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi YY, He L. SHEsis, a powerful software platform for analyses of linkage disequilibrium, haplotype construction, and genetic association at polymorphism loci. Cell Res. 2005;15:97–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawley ME, Kidd KK. HAPLO: a program using the EM algorithm to estimate the frequencies of multi-site haplotypes. J Hered. 1995;86:409–411. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zand N, Tajik N, Moghaddam AS, Milanian I. Genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 enzymes 2C9 and 2C19 in a healthy Iranian population. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:102–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hama T, Norizoe C, Suga H, Mimura T, Kato T, Moriyama H, Urashima M. Prognostic significance of vitamin D receptor polymorphisms in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raimondi S, Johansson H, Maisonneuve P, Gandini S. Review and meta-analysis on vitamin D receptor polymorphisms and cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1170–1180. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gandini S, Raimondi S, Gnagnarella P, Dore JF, Maisonneuve P, Testori A. Vitamin D and skin cancer: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:634–641. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gianfagna F, De Feo E, van Duijn CM, Ricciardi G, Boccia S. A systematic review of meta-analyses on gene polymorphisms and gastric cancer risk. Curr Genomics. 2008;9:361–374. doi: 10.2174/138920208785699544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li D, Zhao H, Gelernter J. Strong association of the alcohol dehydrogenase 1B gene (ADH1B) with alcohol dependence and alcohol-induced medical diseases. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70:504–512. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKay JD, Truong T, Gaborieau V, Chabrier A, Chuang SC, Byrnes G, Zaridze D, Shangina O, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Lissowska J, Rudnai P, Fabianova E, Bucur A, Bencko V, Holcatova I, Janout V, Foretova L, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Benhamou S, Bouchardy C, Ahrens W, Merletti F, Richiardi L, Talamini R, Barzan L, Kjaerheim K, Macfarlane GJ, Macfarlane TV, Simonato L, et al. A genome-wide association study of upper aerodigestive tract cancers conducted within the INHANCE consortium. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macgregor S, Lind PA, Bucholz KK, Hansell NK, Madden PA, Richter MM, Montgomery GW, Martin NG, Heath AC, Whitfield JB. Associations of ADH and ALDH2 gene variation with self report alcohol reactions, consumption and dependence: an integrated analysis. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:580–593. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolstrup JS, Nordestgaard BG, Rasmussen S, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Gronbaek M. Alcoholism and alcohol drinking habits predicted from alcohol dehydrogenase genes. Pharmacogenomics J. 2008;8:220–227. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuccolo L, Fitz-Simon N, Gray R, Ring SM, Sayal K, Smith GD, Lewis SJ. A non-synonymous variant in ADH1B is strongly associated with prenatal alcohol use in a European sample of pregnant women. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:4457–4466. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo X, Kranzler HR, Zuo L, Wang S, Schork NJ, Gelernter J. Diplotype trend regression analysis of the ADH gene cluster and the ALDH2 gene: multiple significant associations with alcohol dependence. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:973–987. doi: 10.1086/504113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hashibe M, McKay JD, Curado MP, Oliveira JC, Koifman S, Koifman R, Zaridze D, Shangina O, Wünsch-Filho V, Eluf-Neto J, Levi JE, Matos E, Lagiou P, Lagiou A, Benhamou S, Bouchardy C, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Menezes A, Dall'Agnol MM, Merletti F, Richiardi L, Fernandez L, Lence J, Talamini R, Barzan L, Mates D, Mates IN, Kjaerheim K, Macfarlane GJ, Macfarlane TV, et al. Multiple ADH genes are associated with upper aerodigestive cancers. Nat Genet. 2008;40:707–709. doi: 10.1038/ng.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J, Lipska BK, Halim N, Ma QD, Matsumoto M, Melhem S, Kolachana BS, Hyde TM, Herman MM, Apud J, Egan MF, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR. Functional analysis of genetic variation in catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT): effects on mRNA, protein, and enzyme activity in postmortem human brain. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:807–821. doi: 10.1086/425589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pap D, Gonda X, Molnar E, Lazary J, Benko A, Downey D, Thomas E, Chase D, Toth ZG, Mekli K, Platt H, Payton A, Elliott R, Anderson IM, Deakin JF, Bagdy G, Juhasz G. Genetic variants in the catechol-o-methyltransferase gene are associated with impulsivity and executive function: Relevance for major depression. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2012;159B:928–940. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer-Lindenberg A, Kohn PD, Kolachana B, Kippenhan S, McInerney-Leo A, Nussbaum R, Weinberger DR, Berman KF. Midbrain dopamine and prefrontal function in humans: interaction and modulation by COMT genotype. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:594–596. doi: 10.1038/nn1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bilder RM, Volavka J, Lachman HM, Grace AA. The catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphism: relations to the tonic-phasic dopamine hypothesis and neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1943–1961. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tunbridge EM, Harrison PJ, Weinberger DR. Catechol-o-methyltransferase, cognition, and psychosis: Val158Met and beyond. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lanni C, Garbin G, Lisa A, Biundo F, Ranzenigo A, Sinforiani E, Cuzzoni G, Govoni S, Ranzani GN, Racchi M. Influence of COMT Val158Met polymorphism on Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in Italian patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;32:919–926. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang W, Schwienbacher C, Lopez LM, Ben-Shlomo Y, Oudot-Mellakh T, Johnson AD, Samani NJ, Basu S, Gögele M, Davies G, Lowe GD, Tregouet DA, Tan A, Pankow JS, Tenesa A, Levy D, Volpato CB, Rumley A, Gow AJ, Minelli C, Yarnell JW, Porteous DJ, Starr JM, Gallacher J, Boerwinkle E, Visscher PM, Pramstaller PP, Cushman M, Emilsson V, Plump AS, et al. Genetic associations for activated partial thromboplastin time and prothrombin time, their gene expression profiles, and risk of coronary artery disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rieck M, Schumacher-Schuh AF, Altmann V, Francisconi CL, Fagundes PT, Monte TL, Callegari-Jacques SM, Rieder CR, Hutz MH. DRD2 haplotype is associated with dyskinesia induced by levodopa therapy in Parkinson’s disease patients. Pharmacogenomics. 2012;13:1701–1710. doi: 10.2217/pgs.12.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heyer E, Balaresque P, Jobling MA, Quintana-Murci L, Chaix R, Segurel L, Aldashev A, Hegay T. Genetic diversity and the emergence of ethnic groups in Central Asia. BMC Genet. 2009;10:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-10-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]