Abstract

Autobiographical memories of trauma victims are often described as disturbed in two ways. First, the trauma is frequently re-experienced in the form of involuntary, intrusive recollections. Second, the trauma is difficult to recall voluntarily (strategically); important parts may be totally or partially inaccessible—a feature known as dissociative amnesia. These characteristics are often mentioned by PTSD researchers and are included as PTSD symptoms in the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). In contrast, we show that both involuntary and voluntary recall are enhanced by emotional stress during encoding. We also show that the PTSD symptom in the diagnosis addressing dissociative amnesia, trouble remembering important aspects of the trauma is less well correlated with the remaining PTSD symptoms than the conceptual reversal of having trouble forgetting important aspects of the trauma. Our findings contradict key assumptions that have shaped PTSD research over the last 40 years.

Autobiographical memory is central to the understanding of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). According to a prevalent view, autobiographical memory of trauma victims is disturbed in at least two ways. First, victims of trauma have intrusive recollections of the traumatic event in which they vividly and repeatedly re-experience disturbing sensory impressions and emotions associated with the event. Second, at the same time they have difficulties remembering important parts of the event—a feature known as dissociative amnesia. These characteristics are not just observations made by PTSD researchers (For reviews see Brewin & Holmes, 2003; Dalgleish, 2004). They are also included as PTSD symptoms in the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Nonetheless, substantial disagreement exists as to how these disturbances should be understood at a theoretical level. Furthermore, some of the PTSD symptoms listed in the diagnostic manual have been criticized for being empirically unfounded, notably the dissociative amnesia component (e.g., Kihlstrom, 2006; McNally, 2003, 2009; Rubin, Berntsen & Bohni, 2008; Shobe & Kihlstrom, 1997). Here we examine two key assumptions in the PTSD literature. One is the assumption that emotional stress during encoding has differential effects on subsequent involuntary and voluntary recall, and the other is the assumption that voluntary recall of trauma is incomplete and fragmented. In order to appreciate how these two tenets are related, a brief historical review is needed.

The diagnosis of PTSD was introduced in DSM III in 1980 as a result of substantial political and social pressure (e.g., Jones & Wessely, 2007; Scott, 1990;Young, 1995, for reviews). The theory outlined in psychiatrist Mardi J. Horowitz’s (1976) seminal monograph Stress Response Syndromes had an enormous impact on how the diagnosis of PTSD was conceptualized and described in 1980 (see Berntsen et al., 2008), as well as in subsequent revisions (American Psychiatric Association, 1980; 1986; 1994; 2000).

Horowitz’s (1975, 1976) model for stress responses has two main tenets concerning the role of memory. One is that the memory of the stressful event tends to repeat itself in an involuntary and uncontrollable fashion. The second tenet is that voluntary (strategic and controlled) remembering of the event is considerably reduced. This leads to the paradoxical situation in which periods with vivid intrusive images of the event may be followed by partial or complete amnesia for the event. According to Horowitz, the underlying cause for both the enhanced involuntary remembering and the impaired voluntary access is incomplete cognitive processing of the traumatic event and defense mechanisms (e.g., repression and denial). Instead of a normal integration into the cognitive schemata of the person, the event is subsumed to an active memory storage – a hypothesized memory system that tends to repeat its own content until its processing has been completed. This memory system constitutes a direct explanation for the enhanced involuntary remembering, according to Horowitz’s theory. The impaired voluntary memory, on the other hand, is caused by defense mechanisms serving to protect against reliving the emotional stress as well as by a poor cognitive match between the trauma and preexisting schema-structures, which leads to faulty encoding of the event.

Although these ideas were formulated almost 40 years ago, and (as we shall review shortly) have little empirical support, many current theories of posttraumatic stress share these two tenets. In other words, they share the assumptions that the encoding of the traumatic event is faulty, that voluntary memory access therefore is impaired, whereas involuntary remembering is enhanced. In Ehlers and Clark’s (2000) theory of PTSD as well as in Brewin’s dual representation theory (Brewin, Dalgleish, & Joseph, 1996; Brewin, Gregory, Lipton, & Burgess, 2010) a shallow encoding of the trauma, focusing on sensory, perceptual and emotional aspects of the event at the cost of deeper conceptual processing and contextual integration is claimed to cause poor intentional recall, on the one hand, and vivid involuntary recollection, on the other. This view is summarized by Halligan, Clark and Ehlers (2002) as a “pattern of poor intentional recall and easy triggering of involuntary memories” (p. 74) and has been frequently repeated by other researchers. For example, Jelinek, Randjbar, Seifert, Kellner, and Moritz (2009) observe that “distorted trauma memories of trauma survivors with PTSD manifest in vivid and highly emotional unintentional recall, as well as incoherent intentional recall” (p. 288). Thus, as in Horowitz’s original theory (1975, 1976), the trauma is proposed to be incompletely processed and this lack of completion and integration leads to reduced intentional memory access and enhanced involuntary remembering.

Importantly, both tenets are reflected in the current diagnosis for PTSD in DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) as well as in the proposed revision of the diagnosis in DSM-5. First, the idea of reduced strategic recall is present in the C3 symptom describing an “inability to recall an important aspect of the trauma” (American Psychiatric Association, 2000, pp 467-468). This description is maintained in the proposed revision of the PTSD diagnosis in the coming DSM-5 and explicitly linked to dissociative amnesia in terms of an “inability to remember an important aspect of the traumatic event(s) (typically due to dissociative amnesia that is not due to head injury, alcohol, or drugs)” [retrieved from http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevisions/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=165]. Second, the assumption of involuntary remembering having privileged access to traumatic and stressful material is reflected in the listing of involuntary (intrusive) recollection as a symptom of PTSD with no mentioning of voluntary remembering -- except in terms of the C3 statement of impaired access (see Berntsen et al., 2008, for further discussion).

However, in spite of their long-lived influence on PTSD research, these assumptions are not well supported empirically. In the following we review and discuss evidence for the claims that (1) emotional stress during encoding has differential effects on subsequent involuntary and voluntary recall, and (2) that voluntary recall of trauma is incomplete and fragmented and more so in individuals suffering from higher levels of PTSD symptoms.

Does Emotional Stress have Differential Effects on Involuntary and Voluntary Recall?

The claim that involuntary (compared to voluntary) remembering has privileged access to stressful/traumatic material, or the related point that PTSD increases that privileged access, has little empirical support. Instead the data suggest that the memory enhancement associated with stressful/traumatic material concerns both involuntary and voluntary memory (e.g., Berntsen & Rubin, 2008, Hall & Berntsen, 2008) and that both involuntary and voluntary memories of the traumatic event are enhanced with higher levels of PTSD symptoms (Rubin, Boals, & Berntsen., 2008, Rubin, Dennis, & Beckham, 2011). Hall and Berntsen (2008) conducted a diary study to examine the frequency of involuntary and voluntary memories of previously presented emotionally negative pictures in a student population. Their findings showed that the emotional distress associated with the pictures at the time of encoding strongly predicted the frequency with which the memories were retrieved both involuntarily and voluntarily in the subsequent diary study. Similar findings were reported by Ferree and Cahill (2009) in a study using emotional films as memory material. Other studies have shown that involuntary and voluntary remembering are similarly affected by real life traumatic events and that the accessibility of the trauma increases for both types of recall with increasing levels of PTSD. In a diary study of undergraduates with either high or low levels of PTSD symptoms, Rubin, et al.(2008) found that undergraduates with high levels of PTSD symptoms recorded more memories related to their traumatic events than did participants with low symptom levels. However, this effect was found to the same extent for both voluntary and involuntary recall, thus the assumed duality between involuntary and voluntary recall was not found. Similar findings were more recently obtained in a sample of clinically diagnosed PTSD patients in comparison with a non-PTSD control group. The PTSD-group had more trauma-related memories, and again this was the case for both voluntary and involuntary recall (Rubin, et al., 2011). Thus, the findings from studies with student populations generalized to a clinical sample diagnosed with PTSD.

More broadly, evidence has accumulated over the last two decades showing that involuntary remembering is not specific to traumatic or stressful events. On the contrary, it is a common phenomenon in everyday life with a predominantly positive content (Berntsen, 2009, for a review). Diary studies and survey studies demonstrate that involuntary remembering of personal events happens at least as frequently as voluntary recollections (Rubin & Berntsen, 2009; Rasmussen & Berntsen, 2011).

Are Trauma Memories Incomplete, Fragmented, and Not Well Integrated?

Incomplete processing and faulty encoding of traumatic events is assumed to lead to reduced intentional access to the traumatic event, and more so in individuals suffering from higher levels of PTSD symptoms. The voluntary access to the trauma is claimed be reduced in at least two ways. First, in this view, the shallow processing of the traumatic event at encoding causes the trauma to be poorly integrated into the autobiographical knowledgebase (Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000; Ehlers & Clark, 2000) because of “little elaboration of the contextual and meaning elements of the event” and “an inability to establish a self-referential perspective” (Halligan et al.,2003, p. 420). This lack of integration is expected to be positively related to level of PTSD symptoms. In order to examine this question, Berntsen and Rubin (2006) developed the Centrality of Event Scale (CES), which measures the extent to which a traumatic event is perceived as central to the person’s life story and identity, and thereby, among other things, appreciated from a self-referential perspective. The CES contains such questions as “I feel that this event has become part of my identity.” “This event has become a reference point for the way I understand myself and the world.” “I feel that this event has become a central part of my life story.” “I often think about the effects this event will have on my future.” In contrast to the disintegration view, several studies have shown that the CES correlates positively (not negatively) with level PTSD symptoms. These studies include a variety of samples, including college students, combat veterans, women with a history of childhood sexual abuse, and community dwelling adults with a diagnosis of PTSD (Berntsen & Rubin, 2006, 2007, 2008; Brown, Antonius, Kramer, Root, & Hirst, 2010; Lancaster, Rodrigueza, & Westonb, 2011; Robinaugh & McNally, 2010, 2011; Smeets, Giesbrecht, Raymaekers, Shaw, Merckelbach, 2010; Schuettler, & Boals, 2011).

Second, the shallow processing at encoding is also claimed to cause internally fragmented memories, for example in terms of the remembered trauma missing important details and having an unclear temporal order. A number of studies have compared the coherence of memories for the traumatic event between individuals who have developed PTSD (or Acute Stress Disorder, ASD) and a no PTSD (or no ASD) group. Many such studies have found the trauma memory to be less coherent in the clinical group compared to the control group both when measured objectively and through self-reports (Amir, Stafford, Freshman, & Foa, 1998; Halligan et al., 2003; Harvey & Bryant, 1999; Jones, Harvery, & Bryant, 2007; Murray, Ehlers, & Mayou, 2002). However, all of these studies suffer from the lack of a non-trauma control memory, for which reason it cannot be excluded that the reduced coherence observed in the clinical group reflects a general deficit in verbal and/or cognitive abilities or other factors in the clinical group relative to the control group. This concern is especially relevant for factors such as education and intelligence, which are lower in samples with PTSD (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000), because Gray and Lombardo (2001) found that differences on memory coherence measures between individuals with versus without PTSD disappeared once cognitive abilities were controlled for.

Studies including non-traumatic control memories have indeed found that a pattern of reduced coherence (or increased fragmentation) in the PTSD-group is not specific to the memory for the traumatic events but generalizes to non-traumatic memories (Gray & Lombardo, 2001; Rubin, 2011; Rubin et al., 2011). Halligan et al. (2003; Study 2) interviewed assault victims about their trauma memory and a non-trauma memory within three months of their being assaulted and did follow-up assessments of PTSD three, six and nine months later. The trauma and non-trauma memories were generally quite coherent with a mean of .69 and .42, respectively, on a 0 to 4 rating of incoherence. Participants who qualified for PTSD at any of the follow up assessments rated their traumatic memory as subjectively less coherent than their non-traumatic control memory, whereas this difference was not present for participants who did not qualify for PTSD at any of the follow-up assessments. In addition to all memories being fairly coherent, a shortcoming of this study is that the diagnostic status of the participants at the time of the memory interview is unclear.

We have been able to identify only one study showing the expected interaction between group (PTSD versus no PTSD at the time of testing) and type of memory (traumatic versus other personal events). In a study of assault victims, Jelinek, Randjbar, Seifert, Kellner, and Moritz (2009) found that the trauma memories were less coherent in the PTSD group than in a control group of healthy adults, and that this reduced coherence was relatively more pronounced for the traumatic memories than for memories of a non-traumatic unpleasant control event. However, Jelinek et al., (2009) found this effect for only one of their three measures -an objectively coded, combined measure which included repetitions and disorganized thoughts minus organized thoughts (Halligan et al., 2003). They did not find it for their two remaining coherence measures that are closer to the concept of dissociative amnesia: an objective measure of global coherence and coherence as measured subjectively through questions designed to tap an experience of having difficulties with intentionally accessing the event and remembering key details (Halligan et al., 2003). It should also be noted that both the traumatic memory and the memory for the non-traumatic unpleasant event in both groups were found to be more coherent than memory for three non-autobiographical narratives in Jelinek et al.’s (2009) study. In general, the level of incoherence reported in these studies is low and not in a range to be invoked as a causal factor of clinical significance. For further discussions on the relation of dissociation and memory fragmentation, see Giesbrecht, Lynn, Lilienfeld, and Merckelbach (2008).

In spite of this poor empirical support, the C3 symptom in the current PTSD diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) is consistent with the idea of impaired integration and fragmentation of trauma memories in PTSD. It holds that there is an inability to recall an important aspect of the trauma. However, meta-analyses of studies reported in the PTSD literature have demonstrated that the C3 symptom is not as clearly associated with this disorder as are the other PTSD symptoms in that it has considerably lower loadings in factor analyses than the other 16 symptoms that make up the current diagnosis. Rubin et al., (2008, Table 4) reviewed studies containing 35 separate analyses investigating the underlying factor structure of the 17 symptoms. The studies included a wide variety of subject populations, including populations both with and without a clinical diagnosis of PTSD. Also different types of symptom measures were used, including both self-report measures and structured clinical interviews. The factor analyses were likewise varied with both exploratory and confirmatory analyses, and 2, 3, and 4 factor solutions. Across the studies, the results for the C3 symptom were similar: the magnitude of the loading of the C3 symptom in the majority of analyses had a rank of 15, 16, or 17 among the 17 symptoms. The C3 often had the lowest loading, often much lower and out of the range of the rest of the items.

A study by Foa, Riggs, and Gershuny (1995) could not be included in the set of 35 analyses because the C3 initially loaded on its own factor and so the authors removed it from their factor analysis. In one of the 35 studies reviewed (Stewart, Conrod, Pihl, & Dongier, 1999), the C3 ranked highest among the 17 symptoms. However, in this study the participants were selected because of substance abuse rather than PTSD, which provides another explanation for the C3’s success and suggests that studies that do not exclude substance abuse or other disorders, such as Borderline Personality Disorder, that might lead to endorsing the C3 may have inflated its loading. In a recent meta-analysis of 40 studies including 14,827 participants, Yufik and Simms found the same results for the C3’s loadings on their two preferred models (2010, Figures 1 and 2). For both models, the C3 loaded .53 whereas the remaining 16 symptoms loaded between .71 and .87, indicating that roughly half as much of the C3’s variance could be attributed to the underlying factor in each analysis.

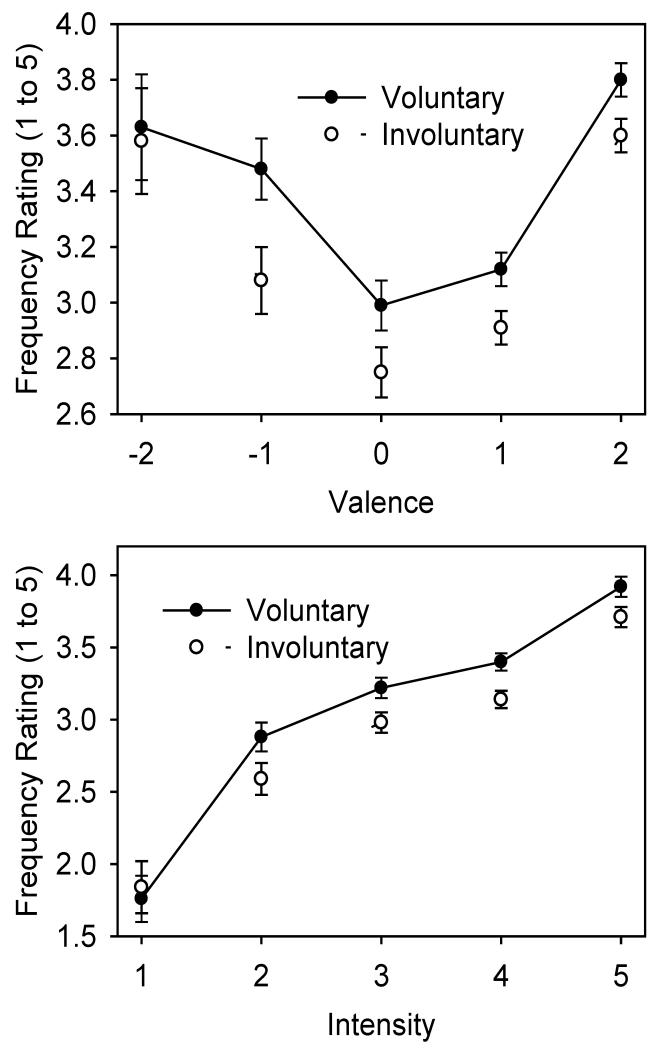

Figure 1.

Frequency rating of voluntary and involuntary memories as a function of valence in the top panel and intensity in the bottom panel (Experiment 1). Error bars are standard errors.

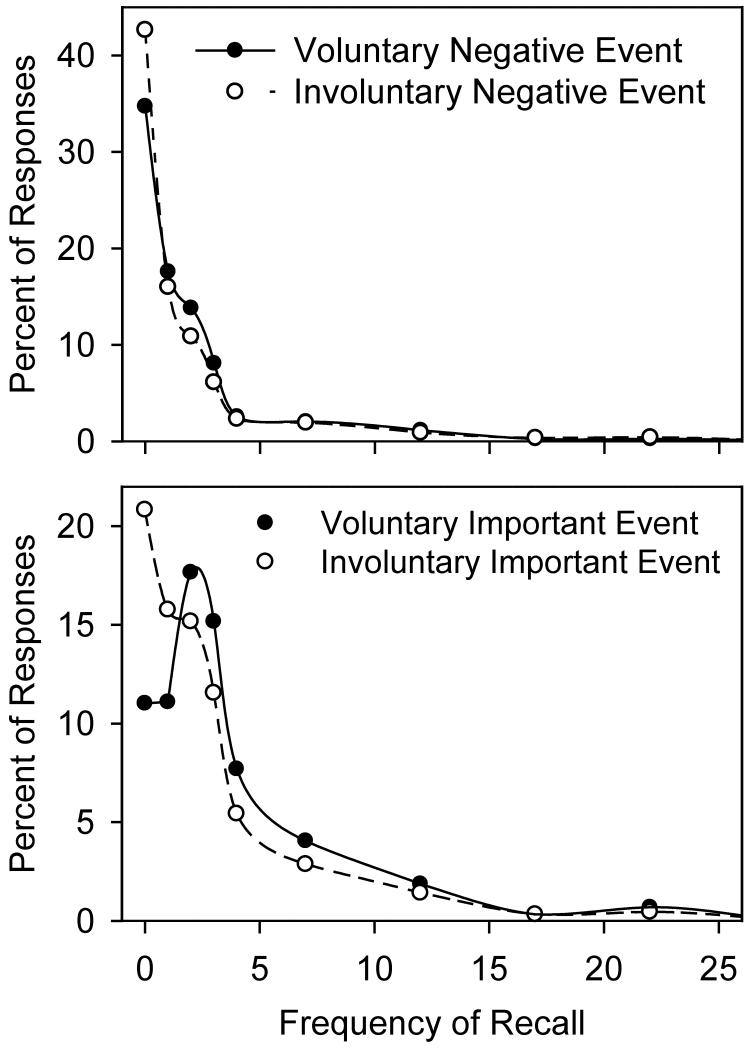

Figure 2.

Distribution of responses as a function of their reported frequency of recall in Experiment 2. The top panel is for negative events and the bottom panel is for important events

In short, across different analytical strategies—including analyses of the accessibility and rated self-relevance of trauma memories, their internal organization as well as psychometric analyses of PTSD measures—little evidence exists for the claim that trauma memories are fragmented and poorly integrated. Of special note, the evidence reviewed exists for both studies using analog samples and studies including participants with clinically diagnosed PTSD.

The Present Studies

The present studies examines the idea of a dissociation between voluntary and involuntary access to traumatic or stressful events as well as the related idea of dissociative amnesia as reflected in the description of the C3 symptom in the current diagnostic criteria for PTSD. In Study 1, involving a large, representative sample, we examine the proposed dissociation between involuntary and voluntary remembering for important events, analyzed in terms of their self-rated emotional content. In Study 2, we replicate and extend this line of research to memory for self-nominated highly negative events. In Study 2 we also examine the idea of dissociative amnesia as reflected in the description of the C3 symptom of PTSD. We directly examine the hypothesis that a reversal of C3 to having “difficulties forgetting central aspects of the trauma” will be better correlated with the remaining PTSD symptoms than the actual C3 referring to “difficulties remembering central aspects”. We use large samples of the general population and of undergraduates, because such populations are needed to answer general questions about involuntary versus voluntary memories and because they show a large variability in the level of PTSD symptoms as well as in the other measures of interest for the present studies. Also, following the spirit of the numerous trauma-analogue studies (e.g., Brewin & Saunders, 2001; Davies & Clark, 1998; Halligan, Clark & Ehlers, 2002; Holmes, Brewin & Hennessy, 2004; Horowitz, 1969, 1975; Pearson, Ross & Webster, 2012; Verwoerd, Wessel, & de Jong, 2012) as well as analyses of the latent structure of PTSD (Ruscio, Ruscio, & Keane, 2002), we rest on the assumption that differences between PTSD and subclinical manifestations of this disorder are quantitative, not qualitative, in nature.

Study 1

Method

Participants

As part of a larger study on the effects of age on involuntary memories (Rubin & Berntsen, 2009) a representative sample of 1013 Danes between 15 and 96 years were asked about an important event from the previous week. Of these 978 (538 female) provided answers to four questions of interest. Their mean age was 44 years (SD = 17, range 15 – 96). In Denmark, for research not involving sensitive topics, 15 year olds providing anonymous data can give consent and participate in survey research and are routinely sampled. Permission to include the data of the younger respondents was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects in Non-Medical Research.

Procedure

Data were collected as part of a telephone survey by TNS Gallup, Denmark. The response rate for the entire survey was 58%. The questions of relevance for the present study were preceded only by demographic questions in the survey. Respondents were read the following introductory instructions. “The following questions are part of research on how memory works. I will ask you some questions on how you remember. I will not ask about what you remember. Thus, I will not ask you to describe the contents of your memories. I will ask you to think back upon an important event that you can remember from last week. It has to be an event that you personally experienced on a particular day. If you do not think that you have had an important event within the last week, please choose a somewhat important event from the last week. Try to remember the event as well as you can. When you have brought the memory to mind, we will continue (here the interviewer paused for a few seconds).”

Following the instruction, all respondents were asked to rate their memories on five-point scales. Four ratings are of interest here. “The emotions I have when I recall the event are intense: not at all intense / vaguely intense / somewhat intense / intense /very intense. The emotions I have when I recall the event are: extremely negative / negative / neutral-mixed / positive / extremely positively. Since it happened, I have willfully thought back to the event in my mind and thought about it or talked about it: never / seldom / sometimes / often / very often. Has the memory of the event suddenly popped up in your thoughts by itself – that is, without you having attempted to remember it?: never / seldom / sometimes / often / very often.”

Results

There were 43, 112, 175, 339, and 309 memories at the five valence ratings of −2, −1, 0, 1, and 2, respectively. Thus, consistent with previous work, a clear dominance of emotionally positive events was found (Walker, Skowronski, & Thompson, 2003). There was also a dominance of memories rated as intense with 37, 112, 241, 316, and 272 memories at the five intensity ratings.

Figure 1 shows the frequency ratings of involuntary and voluntary recall as a function of the valence (top panel) and intensity ratings (bottom panel). An ANOVA corresponding to the means shown in the top panel of Figure 1 had a main effect of valence [F(4, 973) = 27.92, p < .0001, η2 = .08], voluntary versus involuntary recall [F(1, 973) = 28.32, p < .0001, η2 = .01], but no interaction [F(4, 973) = 1.30, p = .27, η2 = .00]. Linear contrasts over the 5 levels of valence for the voluntary and involuntary showed no effect (F(1, 973) = 0.00, p = .95, and F(1, 973) = 0.15, p = .70). Quadratic contrasts over the 5 levels of valence for the voluntary and involuntary retrieval support the claim that emotional intensity, as measured by the absolute level of valence (i.e., a valence of 0 became an intensity of 0, and a valence of ±1 and ±2 became an intensity of 1 and 2), results in more frequent recall (F(1, 973) = 32.71, p < .0001, and F(1, 973) = 49.35, p < .0001). An ANOVA corresponding to the means shown in the bottom panel of Figure 1 had a main effect of intensity [F(4, 973) = 55.22, p < .0001, η2 = .15], voluntary versus involuntary recall [F(1, 973) = 18.08, p < .0001, η2 = .00], but no interaction [F(4, 973) = 1.14, p = .49, η2 = .00]. Linear contrasts over the 5 levels of intensity for the voluntary and involuntary result in more frequent recall [F(1, 973) = 150.75, p < .0001, and F(1, 973) = 118.50, p < .0001], with smaller quadratic contrasts [F(1, 973) = 11.12, p < .001, and F(1, 973) = 2.65, p = .10].

Summary and Discussion

Involuntary and voluntary recall followed the same pattern with regard to the effects of emotion: For both kinds of recall, frequency ratings were higher for emotionally intense events. No effects on the frequency of recall for negative versus positive valence and no interaction effects were found. Overall voluntary recall was rated slightly more frequent than involuntary recall. Study 2 was undertaking in order to examine these questions more closely in relation to measures of self-nominated most negative events as well as well as in relation to measures of PTSD symptoms.

Study 2

In Study 2 we examine the rated frequency of voluntary and involuntary recall of a self-nominated most negative memory as well as a recent self-nominated important event in large sample of undergraduates. We include self-rated measures of PTSD symptoms and whether the stressful event satisfies the diagnostic A1 and A2 criteria for a traumatic event, in order to examine whether these measures show different relations with voluntary and involuntary recall, which we predict they will not.

Study 2 was also conducted to directly examine the idea that voluntary recall of trauma memories are hampered as reflected in the C3 symptom in the current diagnostic criteria for PTSD, which describes an “inability to recall an important aspect of the trauma” (American Psychiatric Association, 2000, pp. 467-468). This description is maintained in the proposed revision of the PTSD diagnosis in the coming DSM-5 and is explicitly linked to dissociative amnesia, as noted in the introduction. However, previous studies have shown that the C3 symptom has a much lower loading in factor analyses than the other PTSD symptoms. This has been shown across different psychometric measures and across different (clinical and non-clinical) populations (see Rubin et al., 2008, for a review). Here we examine the hypothesis that a conceptual reversal of C3 to having “difficulties forgetting central aspects of the trauma” will be better correlated with the remaining PTSD symptoms than the actual C3 referring to “difficulties remembering central aspects”. Such reversal is in line with the view that emotional arousal at the time of the event enhances subsequent memory access for both voluntary and involuntary recall (e.g., McGaugh, 2003, 2004) and that this enhanced memory accessibility is central to the understanding of PTSD (Berntsen & Rubin, 2006, 2007).

The difficulties remembering and difficulties forgetting measures are conceptually opposite with respect to the underlying issue of dissociative amnesia. Empirically, however, there is reason to expect a modest positive correlation between these measures in the present context in part because both are similarly worded items in a test that has no reversed scored items. In addition, the more one cannot forget important parts of an event, the more likely it is that the event has been repeatedly recalled and thought about. Such repeated recall can produce an illusion of partial amnesia stemming from an availability heuristic, in that a prolonged retrieval activity may lead people to realize that there are several details that they are unable to fully remember. This would be true for all events, including positive ones, consistent with previous work (Read & Lindsay, 2000). Finally, by probing cognitive difficulties both measures may be positively related to an underlying dimension of negative affectivity.

Method

Participants

Over four semesters, 1,325 Duke University undergraduates (860 female; mean age 18.92, SD = 1.04, range 18 – 23) completed the study.

Procedure

As part of a web based testing used at the beginning of each semester to screen students for later experiments in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience participants were asked to “please take a moment to think of what negative event or experience from your life is most troubling and stressful to you now”. In relation to that event, they completed the 17 item Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL, Weathers, Litz, Huska, & Keane, 1994), the seven-item version of the CES, and a self-report of whether their negative event satisfied the DSM-IV A1 and A2 trauma criteria, i.e., whether the event involved (A1) “actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others” as well as (A2) “intense fear, helplessness, or horror” (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; p. 467).

Immediately after the standard PCL items, we added one scale in exactly the same form as those on the PCL. This added scale is based on the C3 which asks participants to rate their “Trouble remembering important parts of a stressful experience from the past?” on a five point scale from “not at all” to “extremely.” In contrast, our question asked participants to rate their “Trouble forgetting any important parts of the stressful experience from the past?”

The participants were then asked to respond with a number between 0 and 99 to the following two questions about the event. “In the last week, I have willfully thought back to the event and thought about it or talked about it about _____ times. In the last week, the memory of the event suddenly popped up in your thoughts by itself – that is, without you having attempted to remember it about _____ times”. The questions were always asked in this order to clearly contrast involuntary recall from voluntary recall.

Later in the session, participants were asked to “please think back to the most important event of the previous week” and to answer the same two questions that were used for their negative event, except that the frequency was for occurrence during the last 24 hours. They were then asked to rate on a seven-point scale, “Was the event positive, neutral, or negative?” The extremes were anchored at “-3 extremely negative” and “+3 extremely positive”, with the middle labeled “0 neutral.”

Thus, we sampled two very different events: the most bothersome event from anytime in the participant’s life and the most important event from the last week.

Results

The mean (and SD) on the PCL and was 30.03 (10.98) with a median of 27, and a range from 17 to 72. Of the 1325 participants, 270 indicated that they had both an A1 traumatic event and an A2 emotion, 1039 did not, and 16 failed to answer at least one of these items.

The raw frequencies reported by the participants are shown in Figure 2. Because of the skewed nature of the frequency data, all calculations with the frequency data were made on the base 10 logarithm of one plus the frequency so that frequencies of 0, 9, and 99 were analyzed as 0, 1, and 2, respectively. The reported means and standard deviations were transformed back from these logarithms.

Negative Event

The reported frequency of voluntary memories and involuntary recall of the self-nominated most negative event were similar, with voluntary memories having higher means: mean (SD) of 1.76 (1.81) versus 1.49 (1.86) [F(1, 1324) = 24.80, p < .0001, η2 = .02]; but with both having medians of 1 and modes of 0. To ensure that the skewed distributions did not produce this effect, the frequency distributions were examined and are plotted in the top panel of Figure 2. Because there were few responses above a frequency of four and with most of these occurred at multiples of five or ten, we grouped frequencies above four into bins of five and show the average for the bins. There were 3.70 % voluntary and 3.25 % involuntary responses of 25 or greater not shown in the top panel of Figure 2. The correlation between the voluntary and involuntary frequencies was .74, p < .0001. The PCL correlated positively with both the frequency of voluntary and involuntary recall (rs = .41 and .49, respectively, ps <.0001), counter to the claim that the two kinds of recall follow different patterns and that voluntary recall is reduced with increased levels of PTSD symptoms. The correlations of the PCL with the frequency of voluntary and involuntary recall for those reporting a trauma, satisfying the A criteria, were .38 and .52 and for those not reporting an A trauma .41 and .48, ps <.0001).

Important Event

As shown in the bottom panel of Figure 2, the reported frequency of voluntary and involuntary recall of the same important event were largely similar, but consistent with Study 1, the voluntary recall was more frequent than involuntary recall with means (SDs) of 3.33 (1.34) versus 2.47 (1.53) [F(1, 1324) = 145.84, p < .0001, η2 = .10]; and with medians of 3 and 2 and modes of 2 and 0. There were 2.26 % voluntary and 2.34 % involuntary responses of 25 or greater not shown in the figure. The correlation between the voluntary and involuntary frequencies was .72, p < .0001.

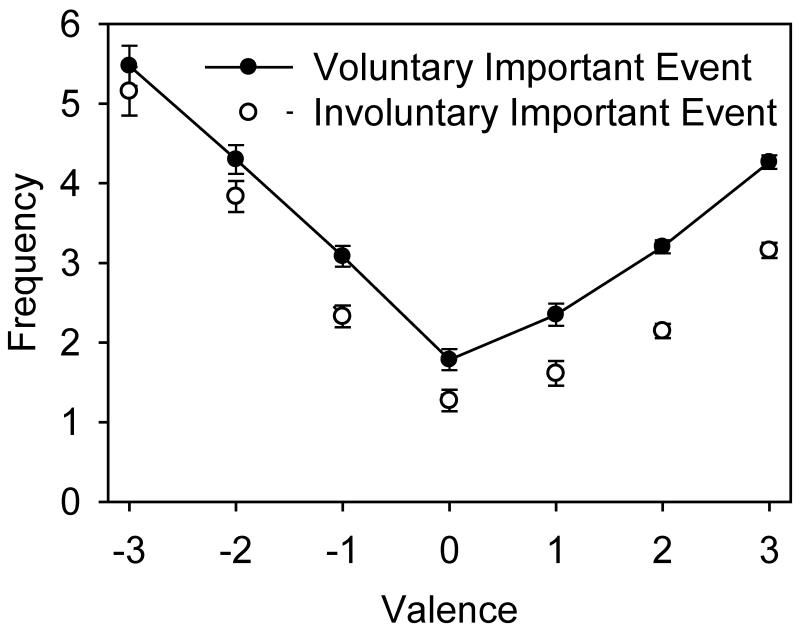

For the important memories, we had a seven-point rating scale of valence by which we could group the data. There were 60, 118, 160, 154, 134, 323, and 376 memories at the seven valence ratings of −3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, and 3. Thus, as in Study 1, a clear dominance of memories rated as positive was seen, consistent with previous work (Walker, et al., 2003). As shown in Figure 3, there were clear results concerning how frequently the participants had recalled the events. There was an effect of the ratings of valence (F(6, 1318) = 20.37, p < .0001, η2 = .07), whether the recall was voluntary or involuntary (F(1, 1318) = 77.29, p < .0001, η2 = .01) and none for the interaction of these factors, although a trend was observed (F(6, 1318) = 2.07, p = .053, η2 = .00). Linear contrasts over the 7 levels of valence for the voluntary and involuntary retrieval support the claim that negative events result in more frequent recall (F(1, 1318) = 10.38, p < .01, and F(1, 1318) = 27.89, p < .0001). Quadratic contrasts over the 7 levels of valence for the voluntary and involuntary retrieval support the claim that intensity, as measured by the absolute level of valence (i.e. a valence of 0 became an intensity of 0, and a valence of ±1, ±2, and ±3 became an intensity of 1, 2, and 3), results in more frequent recall (F(1, 1318) = 82.06, p < .0001, and F(1, 1318) = 85.02, p < .0001), respectively.

Figure 3.

The reported frequency of recall of voluntary and involuntary memories as a function of valence in Experiment 2. Error bars are .05 confidence intervals.

Trouble forgetting

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, reliabilities of the instruments and their correlations with the C3 item of the PCL and our added question. We also include the PCL and the avoidance scale of the PCL without the C3 item to eliminate the problem of predicting a measure with a sum score that includes it. The correlations of the PCL with the CES, BDI, self-reported A trauma and the PCL without the C3 were .50, .53, .11 and .99, respectively. The correlation of the CES and BDI was .29. The correlation of the C3 and the Trouble Forgetting modified item was .29. The correlation of all measures shown in the table with the Trouble Forgetting item was always higher than with the C3, as shown by the Hotelling’s t-test. If correlations were made separately for groups of participants reporting versus not reporting a stressful event satisfying the A trauma criteria, the average absolute difference between these groups in the correlations shown in Table 1 would be .05 (range .01 to .09) and no group difference would be significant (all ps > .10).

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, Reliabilities, and Correlations in Experiment 2.

| Correlations |

Hotellings t-tests |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | α | C3 | Trouble Forgetting |

|

| PCL B | 9.82 | 4.15 | .84 | .21 | .46 | 5.35**** |

| PCL C without C3 | 10.71 | 4.43 | .79 | .26 | .43 | 3.58*** |

| PCL D | 7.91 | 3.56 | .80 | .25 | .42 | 3.53*** |

| PCL without C3 | 28.45 | 10.67 | .91 | .27 | .50 | 5.25**** |

| CES | 2.63 | 1.15 | .93 | .19 | .34 | 2.87** |

| BDI-II | 5.06 | 5.95 | .88 | .14 | .31 | 3.16** |

| C3 | 1.59 | 0.98 | ||||

| Trouble Forgetting | 1.67 | 1.01 | ||||

Notes: all values based on an n =1325. All correlations shown are statistically significant at p <.0001. α is Cronbach’s Alpha. Hotellings T-test is for the difference between the C3 and Trouble Forget correlations.

= p <.01,

= p <.001,

= p < .0001;

To investigate the two items related to accessing important parts of the memory, we predicted them both using multiple regressions with the CES, BDI, self-reported A trauma, and the PCL with the C3 not included in the sum. We included all items using a best fit with no restrictions. The equations using standardized beta weights were C3 = .23 PCL + .14 trauma + .05 CES - .01 BDI, R2 =.10, and Trouble Forgetting = .41 PCL + .10 trauma + .10 CES + .06 BDI, R2 =.27.

In short, consistent with our predictions, we found that a conceptual reversal of the C3 to having “trouble forgetting central aspects of the trauma” was significantly better correlated with the remaining PTSD symptoms than the actual C3 referring to “trouble remembering central aspects”. This pattern was found across all categories of PTSD symptoms.

Summary and Discussion

The self-nominated most negative event showed the same overall distributions of frequency ratings for involuntary and voluntary recall, although voluntary recall was rated slightly more frequent. Both were positively correlated with level of PTSD symptoms. For the self-nominated important event, voluntary recall was rated as more frequent than involuntary recall. This agrees with Study 1 and previous studies showing that voluntary compared to involuntary memories tends to favor more self-relevant events, presumably due to a more top down schema-based search (Berntsen, 2009).

Participants’ ratings of how frequently they had voluntarily versus involuntarily recalled the events were examined as a function of ratings of the emotional valence of the events. This analysis showed that the two forms of recall followed the same pattern with emotionally intense events having been remembered more frequently than less intense events for both types of recall. In addition, negative events were remembered slightly more frequently than positive events for both types of recall. No interaction effects were observed.

The reversal of the C3 to trouble forgetting showed consistently higher correlations with the remaining PTSD symptoms as compared to the actual C3 referring to “trouble remembering central aspects” of traumatic or stressful event. This provided further evidence that traumatic events are easily accessed through both voluntary and involuntary recall.

General Discussion

We examined two key assumptions in the PTSD literature. One is the assumption that negative emotional stress during encoding has differential effects on subsequent involuntary and voluntary recall, and the other was the related assumption that voluntary recall of trauma is incomplete and fragmented, especially for individuals with higher levels of PTSD symptoms.

Our findings add to previous work showing that involuntary and voluntary recall follow the same pattern with regard to their ability at accessing emotional events. The findings contradict the idea that emotional arousal at the time of the event reduces voluntary while enhancing involuntary access. The methods used in the present studies are different from those used previously, but the conclusions are similar. For both involuntary and voluntary recall the emotional intensity of the remembered events is the key predictor for how frequently the events are recalled.

In Study 1, we showed that a large stratified population rated the frequency of voluntary and involuntary recall of their most important event as similar. When their most important life event was analyzed in terms of emotional valence, voluntary and involuntary recall ratings followed the same pattern: Extremely positive and extremely negative events were judged to be more rehearsed both voluntarily and involuntarily. This finding was replicated and extended in Study 2, which involved a large sample of undergraduates who rated voluntary and involuntary recall of their most negative event as well as their most important event from the last week. We found again that voluntary and involuntary memories followed the same pattern with emotionally intense events having been remembered more frequently than less intense events for both types of recall. In addition we found negative events being slightly more frequently remembered for both types of recall. Correlations with PTSD symptoms were similar for the two types of recall, and this pattern did not differ between participants who reported that their negative event satisfied, versus did not satisfy, the A diagnostic trauma criteria for PTSD.

In Study 2 we also used a different strategy to test our predictions. We found that ratings of difficulties forgetting central aspects of the trauma, a conceptual reversal of the C3 symptom in the current PTSD diagnostic, was significantly better correlated with the remaining PTSD symptoms than the actual C3 referring to difficulties remembering central aspects of the trauma. This finding supports the view that traumatic events are easily accessed through both voluntary and involuntary recall. It adds to previous work with both clinical and non-clinical populations showing that the C3 symptom – which is the only symptom directly addressing dissociative amnesia – is relatively poorly related to the remaining PTSD symptoms (Rubin et al., 2008; Yufik & Simms, 2010). Although both the C3 and the reversal of C3 were positively correlated with the remaining PTSD symptoms, the reversal of C3 showed consistently higher correlations than the actual C3 across all symptom groups, which indicates that having difficulties forgetting (rather than difficulties remembering) the traumatic event is a better conceptualization of the way memory works in relation to the other PTSD symptoms.

Although the actual C3 and the reverse C3 are conceptually opposite with respect to the underlying issue of dissociative amnesia, they correlated positively with one another. Such a correlation was expected for three reasons. First, both were similarly worded items in a test that has no reversed scored items. Second, having difficulties forgetting important parts is likely to imply prolonged retrieval activity (i.e., recurrent recall). Such prolonged retrieval activity has been found to produce an impression of partial amnesia by bringing people to realize that there are still several details of the event that they are unable to fully remember or that they may have recovered details which prior were inaccessible. This effect reflects a normal heuristics in the ways we tend to think about memory and is not limited to trauma (Read & Lindsay, 2000). Third, the positive correlation between the two items as well as the fact that they both correlate with PTSD symptoms may reflect a broader tendency for participants with higher levels of PTSD to perceive themselves as having cognitive and emotional difficulties and therefore be inclined to provide confirmative answers to both having trouble remembering and having trouble forgetting. In this interpretation, the correlation would reflect an underlying dimension of distress or negative affectivity influencing answers to both questions. These three reasons could also account in part for the moderate loading of the C3 that remains in factor analyses.

The present studies involved large samples of undergraduates and of the general population. Such populations show a larger variability in the level of PTSD symptoms compared to clinical populations, in which everyone would be expected to show high (albeit varying) symptom levels. In the present study, the PCL scores ranged from 17 to 72 (maximum range on the PCL is 17 to 85). In individuals with a clinical diagnosis of PTSD the range would be narrower with most scores above 43 on the PCL (Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996). The variability in symptom levels in the present sample can be viewed as an advantage in relation to the correlational analyses employed here, because the full range of the scale is being used. On the other hand, it may be suggested that the dissociation between involuntary and voluntary access to the traumatic event is only seen in extreme cases and therefore requires a clinical population. We consider this as being unlikely since the present findings coincide with what has been found in studies with clinical populations using a diary method for recording involuntary and voluntary memories as they occur in daily life (Rubin et al., 2011) as well as psychometric analyses of the C3 in relation to other PTSD symptoms (see Rubin et al., 2008, for a review). The finding that involuntary and voluntary recall accessed emotionally negative events with equal frequencies has also recently been replicated in a study involving clinically depressed individuals (Watson, Berntsen, Kuykens & Watkins, 2012). Also, psychometric analyses of the latent structure of PTSD support the view that PTSD reflects the high end of a continuum of stress response symptoms rather than a discrete clinical syndrome (Ruscio et al., 2002). Nonetheless, it is still possible that different levels of PTSD symptoms (e.g., mild, moderate and severe) would be differentially associated with other, external measures, following Flett, Vredenburg and Krames’ (2009) notion of phenomenological continuity. Future research should therefore extend the current methods to clinical populations.

In the light of the present findings, how should we explain the clinical observation that some PTSD patients have difficulties accessing important aspects of their trauma, while at the same time suffering from repetitive intrusive recollections of episodic details? First, given the many disorders that have strong comorbidity with PTSD, one possibility is that these observations are due to the presence of comorbid disorders, since disorganized thought in relation to autobiographical events exists in many clinical disorders, such as Borderline Personality Disorder (Jørgensen et al., 2012). This alternative explanation can be easily differentiated from disorganized memories of traumas as it would apply across different types of memories, and not just to trauma memories. Second, findings from research on overgeneral memories in depression and PTSD also suggest a possible explanation. Individuals with PTSD show a general reduced ability to retrieve specific autobiographical events in response to cue words (McNally et al., 1994) similar to the deficits observed in depression (Williams et al., 2007). The most likely explanation for this deficit, according to Williams et al. (2007), is reduced executive processes, in part due to rumination and worry or attempts at avoiding painful memories. To the extent trauma victims show this deficit, their ability to access discrete episodic details of the trauma and other autobiographical events may be reduced. At the same time recent findings with depressed individuals (Watson, Berntsen, Kuykens & Watkins, in press) suggest that this deficit does not generalize to involuntary recall of past autobiographical events, for which stable depressed individuals show no difference in memory specificity compared with recovered and never depressed individuals, presumably because the involuntary remembering involves less executive monitoring (Berntsen, Staugaard & Sørensen, in press). Thus, a PTSD patient with reduced executive functions may have difficulties intentionally accessing concrete episodic details of any past events, including (but not limited to) the traumatic experience, while at the same time have involuntary recollections of such details. More research on involuntary and voluntary autobiographical memories in PTSD is needed to examine this possibility.

In conclusion, the findings reported here contradict the view – dating back to the infancy of PTSD research – that involuntary remembering yields privileged access to traumatic events, and that voluntary access is hampered by the trauma memory being fragmented and poorly integrated. Instead, the findings support the alternative view that involuntary and voluntary remembering follow the same pattern with regard to the effects of emotion, that is, both are enhanced by emotional stress during encoding. Although the duality view introduced by PTSD pioneers (e.g., Horowitz, 1976) almost 40 years ago has been extremely influential and productive, time has come to reconsider this prevalent belief in the light of the accumulating evidence from the wealth of research it has spurred.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Danish National Research Foundation grant DNRF93, Danish Council for Independent Research: Humanities, and NIH grant R01MH066079 for support. We thank John F. Kihlstrom and Scott O. Lilienfeld for helpful comments.

Contributor Information

Dorthe Berntsen, Aarhus University.

David C. Rubin, Duke University, and Aarhus University

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. rev American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Text Revision American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Amir N, Stafford J, Freshman MS, Foa EB. Relationship between trauma narratives and trauma pathology. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1998;11:385–392. doi: 10.1023/A:1024415523495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen D. Involuntary autobiographical memories. An introduction to the unbidden past. Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen D, Rubin DC. The centrality of event scale: A measure of integrating a trauma into one’s identity and its relation to post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:219–231. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen D, Rubin DC. When a Trauma Becomes a Key to Identity: Enhanced Integration of Trauma Memories Predicts Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2007;21:417–431. [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen D, Rubin DC, Bohni KM. Contrasting models of PTSD. Reply to Monroe and Mineka. Psychological Review. 2008;115:1099–1107. doi: 10.1037/a0013730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen D, Staugaard SR, Sørensen LMT. Why am I remembering this now? Predicting the occurrence of involuntary (spontaneous) episodic memories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. doi: 10.1037/a0029128. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL) Behaviour, Research and Therapy. 1996;34:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:748–766. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Dalgleish T, Joseph S. A dual representation theory of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Review. 1996;103:670–686. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.103.4.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Gregory JD, Lipton M, Burgess N. Intrusive images in psychological disorders: Characteristics, neural mechanisms, and treatment implications. Psychological Review. 2010;117:210–232. doi: 10.1037/a0018113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Holmes EA. Psychological theories of posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:339–376. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Saunders J. The effect of dissociation at encoding on intrusive memories for a stressful film. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 2001;74:467–472. doi: 10.1348/000711201161118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AD, Antonius D, Kramer M, Root JC, Hirst W. Trauma centrality and PTSD in veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23:496–499. doi: 10.1002/jts.20547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgleish T. Cognitive approaches to Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: The evolution of multirepresentational theorizing. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:228–260. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies MI, Clark DM. Predictors of analogue post-traumatic intrusive cognitions. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1998;26:303–314. [Google Scholar]

- Ferree NK, Cahill L. Post-event spontaneous intrusive recollections and strength of memory for emotional events in men and women. Consciousness and Cognition. 2009;18:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS, Gershuny BS. Arousal, numbing, and intrusion: Symptom structure of PTSD following assault. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:116–120. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesbrecht T, Lynn SJ, Lilienfeld SO, Merckelbach H. Cognitive processes in dissociation: an analysis of core theoretical assumptions. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:617–647. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.5.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MJ, Lombardo TW. Complexity of trauma narratives as an index of fragmented memory in PTSD: A critical analysis. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2001;15:S171–S186. [Google Scholar]

- Hall NM, Berntsen D. The effect of Emotional Stress on Involuntary and Voluntary Conscious Memories. Memory. 2008;16:48–57. doi: 10.1080/09658210701333271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halligan SL, Clark DM, Ehlers A. Cognitive processing, memory, and the development of PTSD symptoms: two experimental analogue studies. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2002;33:73–89. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halligan SL, Michael T, Clark DM, Ehlers A. Posttraumatic stress disorder following assault: The role of cognitive processing, trauma memory, and appraisals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:419–431. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG, Bryant RA. A qualitative investigation into the organization of traumatic memories. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1999;38:401–405. doi: 10.1348/014466599162999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EA, Brewin CR, Hennessy RG. Trauma films, information processing, and intrusive memory development. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2004;133:3–22. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.133.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz MJ. Psychic trauma. Return of images after stress film. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1969;20:552–559. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1969.01740170056008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz MJ. Intrusive and repetitive thought after experimental stress. Archives of general psychiatry. 1975;32:1457–1463. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760290125015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz MJ. Stress response syndromes. Jason Aronson; New York: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Jelinek L, Randjbar S, Seifert D, Kellner M, Moritz S. The organization of autobiographical and nonautobiographical memory in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:288–298. doi: 10.1037/a0015633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C, Harvey AG, Brewin CR. The organization and content of trauma memories in survivors of road traffic accidents. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:151–162. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones E, Wessely S. A paradigm shift in the conceptualization of psychological trauma in the 20th century. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2007;21:164–175. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen CR, Berntsen D, Bech M, Kjølbye M, Bennedsen B, Ramsgaard S. Identity-related autobiographical memories and cultural life scripts in patients with Borderline Personality Disorder. Consciousness & Cognition. 2012;21:788–798. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihlstrom JF. Trauma and memory revisited. In: Uttl B, Ohta N, Siegenthaler AL, editors. Memory and Emotions: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Blackwell; New York: 2006. pp. 259–291. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster SL, Rodrigueza BF, Westonb R. Path analytic examination of a cognitive model of PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;49:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh JL. Memory and Emotion. The making of lasting memories. Columbia University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh JL. The amygdala modulates the consolidation of memories of emotionally arousing experiences. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2004;27:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ. Progress and controversy in the study of posttraumatic stress disorder. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:229–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ. Can we fix PTSD in DSM-V? Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:597–600. doi: 10.1002/da.20586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ, Litz BT, Prassas A, Shin LM, Weathers FW. Emotion priming of autobiographical memory in post-traumatic stress disorder. Cognition and Emotion. 1994;8:351–367. [Google Scholar]

- Murray J, Ehlers A, Mayou RA. Dissociation and post-traumatic stress disorder: Two prospective studies of road traffic accident survivors. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;180:363–368. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newby JM, Moulds ML. Intrusive memories of negative events in depression: Is the centrality of the event important? Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2011;42:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson DG, Ross FDC, Webster VL. The importance of context: Evidence that contextual representations increase intrusive memories. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2012;43:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen AS, Berntsen D. The Unpredictable Past: Spontaneous Autobiographical Memories Outnumber Memories Retrieved Strategically. Consciousness & Cognition. 2011;20:1842–1846. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JD, Lindsay DS. “Amnesia” for summer camps and high school graduation: Memory work increases reports of prior periods of remembering less. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000;13:2000. doi: 10.1023/A:1007781100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinaugh DJ, McNally RJ. Autobiographical memory for shame and guilt provoking events: Association with psychological symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48:646–665. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinaugh DJ, McNally RJ. Trauma centrality and PTSD symptom severity in adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of traumatic stress. 2011;24:483–486. doi: 10.1002/jts.20656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC. The coherence of memories for trauma: Evidence from posttraumatic stress disorder. Consciousness & Cognition. 2011;20:857–865. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC, Berntsen D. The Frequency of Voluntary and Involuntary Autobiographical Memories across the Lifespan. Memory & Cognition. 2009;37:679–688. doi: 10.3758/37.5.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC, Berntsen D, Bohni MK. A memory-based model of posttraumatic stress disorder: Evaluating basic assumptions underlying the PTSD diagnosis. Psychological Review. 2008;115:985–1011. doi: 10.1037/a0013397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC, Boals A, Berntsen D. Memory in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Properties of voluntary and involuntary, traumatic and non-traumatic autobiographical memories in people with and without PTSD symptoms. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2008;137:591–614. doi: 10.1037/a0013165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC, Dennis MF, Beckham JC. Autobiographical Memory for Stressful Events: The Role of Autobiographical Memory in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Consciousness and Cognition. 2011;20:840–856. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AM, Ruscio J, Keane TM. The latent structure of posttraumatic stress disorder: A taxometric investigation of reactions to extreme stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:290–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott WJ. PTSD in DSM-III. A Case in the politics of diagnosis and disease. Social problems. 1990;37:294–309. [Google Scholar]

- Schuettler D, Boals A. The path to posttraumatic growth versus PTSD: Contributions of event centrality and coping. Journal of Loss & Trauma. 2011;16:180–194. [Google Scholar]

- Shobe KK, Kihlstrom JF. Is traumatic memory special? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1997;8:70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Smeets T, Giesbrecht T, Raymaekers L, Shaw J, Merckelbach H. Autobiographical integration of trauma memories and repressive coping predict post-traumatic stress symptoms in undergraduate students. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2010;17:211–218. doi: 10.1002/cpp.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Conrod PJ, Pihl RO, Dongier M. Relations between posttraumatic stress symptoms dimensions and substance dependence in a community-recruited sample of substance-abusing women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13:78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Walker RW, Skowronski JJ, Thompson CP. Life is pleasant – and memory helps to keep it that way. Review of General Psychology. 2003;7:203–210. [Google Scholar]

- Watson LA, Berntsen D, Kuyken W, Watkins ER. The characteristics of involuntary and voluntary autobiographical memories in depressed and never depressed individuals. Consciousness and Cognition. 2012;21:1382–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson LA, Berntsen D, Kuyken W, Watkins ER. Involuntary and voluntary autobiographical memory specificity as a function of depression. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2012.06.001. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD checklist (PCL) Unpublished scale available from the National Center for PTSD. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Williams JMG, Barnhofer T, Crane C, Herman D, Raes F, Watkins E, Dalgleish T. Autobiographical memory specificity and emotional disorder. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:122–148. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verwoerd J, Wessel I, de Jong PJ. Fewer intrusions after an intentional bias modification training for perceptual reminders of analogue trauma. Cognition and Emotion. 2012;26:153–165. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2011.563521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young A. The harmony of illusions: Inventing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Princeton University Press; Princeton: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yufik T, Simms LJ. A Meta-Analytic Investigation of the Structure of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:764–776. doi: 10.1037/a0020981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]