Abstract

Mendelian disorders of RANKL/OPG/RANK signaling feature the extremes of aberrant osteoclastogenesis and cause either osteopetrosis or rapid turnover skeletal disease. The patients with autosomal dominant accelerated bone remodeling have familial expansile osteolysis, early-onset Paget’s disease of bone, expansile skeletal hyperphosphatasia, or panostotic expansile bone disease due to heterozygous 18-, 27-, 15-, and 12-bp insertional duplications, respectively, within exon 1 of TNFRSF11A that encodes the signal peptide of RANK. Juvenile Paget’s disease (JPD), an autosomal recessive disorder, manifests extremely fast skeletal remodeling, and is usually caused by loss-of-function mutations within TNFRSF11B that encodes OPG. These disorders are ultra-rare. A 13-year-old Bolivian girl was referred at age 3 years. One femur was congenitally short and curved. Then, both bowed. Deafness at age 2 years involved missing ossicles and eroded cochleas. Teeth often had absorbed roots, broke, and were lost. Radiographs had revealed acquired tubular bone widening, cortical thickening, and coarse trabeculation. Biochemical markers indicated rapid skeletal turnover. Histopathology showed accelerated remodeling with abundant osteoclasts. JPD was diagnosed. Immobilization from a femur fracture caused severe hypercalcemia that responded rapidly to pamidronate treatment followed by bone turnover marker and radiographic improvement. No TNFRSF11B mutation was found. Instead, a unique heterozygous 15-bp insertional tandem duplication (87dup15) within exon 1 of TNFRSF11A predicted the same pentapeptide extension of RANK that causes expansile skeletal hyperphosphatasia (84dup15). Single nucleotide polymorphisms in TNFRSF11A and TNFRSF11B possibly impacted her phenotype. Our findings: i) reveal that JPD can be associated with an activating mutation within TNFRSF11A, ii) expand the range and overlap of phenotypes among the mendelian disorders of RANK activation, and iii) call for mutation analysis to improve diagnosis, prognostication, recurrence risk assessment, and perhaps treatment selection among the monogenic disorders of RANKL/OPG/RANK activation.

Keywords: bone remodeling, deafness, osteolysis, osteoprotegerin, tooth loss, vascular calcification

II) INTRODUCTION

Identification of the RANKL/OPG/RANK signaling pathway as the principal regulator of osteoclast (OC) formation and action began during 1997–1998 with the discovery of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL), its “decoy” receptor osteoprotegerin (OPG), and its receptor RANK within the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily.(1) Soon after, genetically altered mice revealed that osteoclastogenesis is accelerated or slowed by binding of RANKL to RANK versus OPG, respectively.(2) Then, their importance for humans became certain when mutations within TNFSF11 (RANKL), TNFRSF11A (RANK), and TNFRSF11B (OPG) explained disorders that resemble Paget’s disease of bone (PDB1: OMIM #167250)(3) with enhanced osteoclastogenesis and accelerated skeletal remodeling, or are osteopetroses that feature diminished osteoclastogenesis and failure of bone resorption.(4)

First, in 2000, Hughes et al.(5) discovered that autosomal dominant (AD) familial expansile osteolysis (FEO: OMIM # 174810)(3) reflects a heterozygous 18-base pair (bp) insertional tandem duplication (84dup18) within exon 1 of TNFRSF11A that encodes the signal peptide of RANK. FEO features accelerated bone turnover that can lead to osteolytic lesions that expand major long bones (causing pain, fracture, and deformity), deafness in childhood, osteoporosis (OP), and osteogenic sarcoma.(6) Also, Hughes et al(5) showed that a similar 27-bp tandem duplication (75dup27) explained AD early-onset PDB in a Japanese family (PDB2: OMIM # 602080).(3) Transfection studies indicated that FEO-RANK and PDB2-RANK sequester intracellularly and enhance NF-κB signaling.(5)

In 2002, Whyte and Hughes(7) discovered that AD expansile skeletal hyperphosphatasia (ESH)(8) results from a heterozygous 15-bp insertional tandem duplication (84dup15) within exon 1 of TNFRSF11A that too would extend the signal peptide of RANK. ESH features deafness in infancy followed in childhood by accelerated bone remodeling, painful expanded phalanges in the hands, episodic hypercalcemia, and hyperostotic widening of major long bones.(8, 9)

In 2014, Shafer et al(10) delineated in a young man the most severe form of RANK activation, panostotic expansile bone disease (PEBD), featuring early-onset deafness and a massive benign jaw tumor caused by a 12-bp insertional tandem duplication (90dup12) in TNFRSF11A.

Juvenile Paget’s disease (JPD: OMIM # 23900)(3) features the most rapid bone remodeling, and by early childhood leads to deafness, tooth loss, bone pain, fractures, deformities, and sometimes later to osteosarcoma.(4) In 2002, Whyte et al(11) and Cundy et al(12) discovered that this autosomal recessive (AR) disorder can be caused by loss-of-function mutations within TNFRSF11B that encodes OPG. Typically, unique homozygous TNFRSF11B mutations represent a “founder” in different geographical regions.(13) This OPG deficiency form of JPD uniquely leads to vascular microcalcification (VMC)(14) that perhaps explains carotid aneurysms in childhood(15) and retinopathy with blindness in adult life.(16, 17) A genetic basis for other instances of JPD remains presumptive.(4)

Finally, in 2007 and 2008, AR loss-of-function mutations in TNFSF11 encoding RANKL and TNFRSF11A encoding RANK were discovered by Sobacchi et al(18) and Guerrini et al,(19) respectively, to cause “OC poor” forms of osteopetrosis.(20)

Here, we report a 13-year-old Bolivian girl diagnosed at age 3 years with JPD who has no mutation of TNFRSF11B, but instead carries a unique heterozygous 15-bp insertional tandem duplication (87dup15) in exon 1 of TNFRSF11A encoding RANK.

III) MATERIALS AND METHODS

A) Case Report

This 13-year-old Bolivian girl was referred at 3 years-of-age for unexplained dento-osseous disease. One week before birth, ultrasonography detected a short and bowed right femur. Otherwise, the pregnancy and full-term delivery were uneventful. Birth weight was 3.6 kg. Her deformed right thigh was expected to straighten spontaneously. First radiographs were at age 1 month (see Radiological Findings).

She walked at age 1½ years. At nearly age 2 years, her right radius and ulna fractured during a fall. The casted bones healed over one month. Bilateral deafness had been documented by audiometry, but hearing aides were not helpful.

Beginning at age 3 years, several anterior maxillary and mandibular teeth fractured, loosened, and were shed painlessly (Supplementary Appendix, Figure 1). A dentist found early resorption of the primary tooth roots and hypoplasia of permanent teeth (see Dental Findings). She was intelligent, consumed copious milk, and had no chronic pain. Her right thigh was short, which caused limping. Height was 100 cm (z-score + 1.5), weight 18 kg (z-score + 1.4), and head circumference 50 cm (z-score + 0.2). Mineral homeostasis was intact, but bone turnover markers (BTMs) were substantially elevated (see Biochemical Findings). A radiographic skeletal survey most closely resembled JPD (see Radiological Findings), which became her diagnosis. Ophthalmologic examination to search for retinal VMC(17) associated with JPD was unremarkable. Her healthy mother and father, ages 29 and 32 years, respectively, were not consanguineous. A paternal 2-year-old half-brother seemed well. The mother mentioned a bone disease, but no known deafness, in her estranged husband’s family.

At nearly 4 years-of-age and five days after two 3-day courses of oral doxycycline (15 mg/kg/day), her right femur diaphysis was biopsied (see Histopathological Findings) causing a fracture. She became non-weight bearing in a spica cast. Fifteen days later, headache and vomiting accompanied hypercalcemia of 15.5 mg/dl (repeated 16.4 mg/dl) (Nl, 8.8 – 10.6). Pamidronate (PMD), 0.5 mg/kg/day intravenously (iv) on two consecutive days, corrected the hypercalcemia after four days. Vitamin D (400 IU) was administered daily. Subsequently, she received “cycles” of PMD consisting of three sequential daily iv infusions. The first cycle was 0.75, 1, and 1 mg/kg body weight. Further cycles consisted of 1 mg/kg/day. The first two cycles were separated by four months, and the 3rd – 9th cycles occurred about yearly (see Biochemical Findings). She also received 500 mg calcium carbonate orally each day during, and for one week after, each cycle. A goal was reduction of BTMs to near or within their normal ranges.

B) Radiological Studies

All radiographs were reviewed representing ages 1 month and 1, 1¾, 3, and 4 years (before PMD), and age 9 years (5 years of PMD therapy). Computed tomography (CT) of the petrous bones was performed at age 3 years. Yearly panorex radiographs began at age 4 years. Whole body bone scintigraphy was obtained at ages 4, 6, and 9 years. Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) was performed at age 7 years.

C) Mutation Analyses

Genomic DNA from the patient and parents was isolated using the Gentra Puregene kit (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA, USA) from leukocytes in whole blood sent in 2004 from Buenos Aires, Argentina to St. Louis, USA.

Because her diagnosis was JPD, we first examined TNFRSF11B that encodes OPG.(11) All coding exons and adjacent mRNA splice sites were amplified by PCR and sequenced in both directions. When no TNFRSF11B mutation was found in these individuals (see Results), we studied exon 1 of TNFRSF11A (RANK) amplified by PCR and sequenced in both directions.(10) After preliminary evidence of a TNFRSF11A duplication in exon 1, this exon was re-amplified by PCR, the amplicon was sub-cloned (Topo Cloning Kit, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and the individual clones were sequenced. Then, we examined for the patient all exons and splice sites of TNFRSF11A and also TNFSF11 encoding RANKL.(20) To confirm the patient’s seemingly sporadic TNFRSF11A duplication (see Results), new blood samples from her and from her mother were obtained in 2007 (the father was unavailable for a second specimen).

Finally, we examined all TNFRSF11A and TNFSF11 exons and splice sites of our two unrelated JPD patients for whom we reported in 2002 no TNFRSF11B mutations.(11)

IV) RESULTS

A) Mutation Analyses

No mutation in TNFRSF11B (OPG) was identified in our patient or her parents. However, she was homozygous (Asn) for a non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in exon 1 (Lys3Asn, rs2073618) (see Discussion).

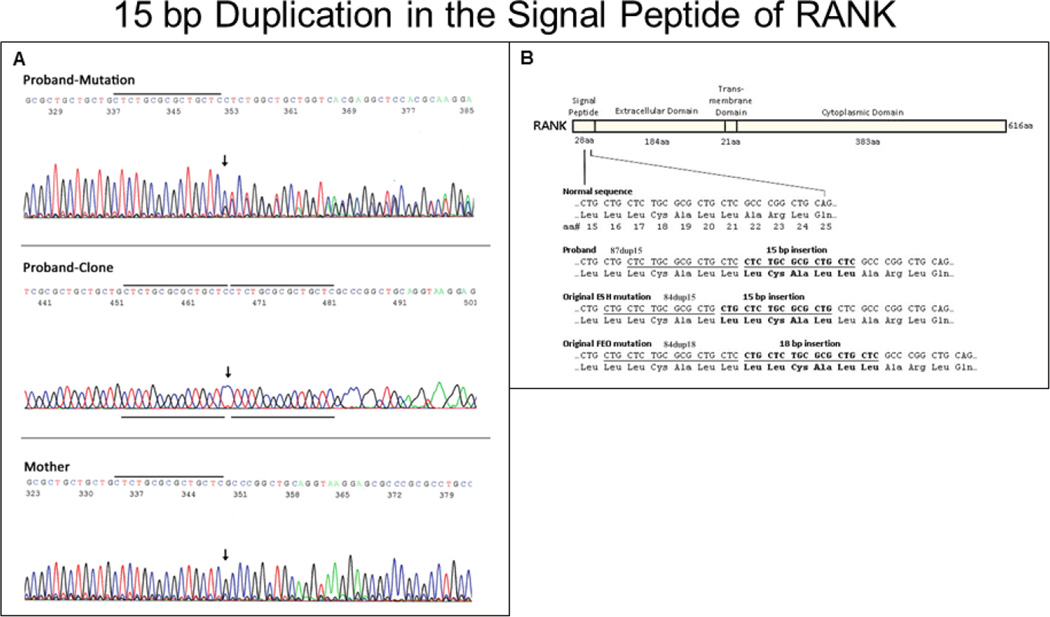

Instead, a heterozygous insertional tandem duplication mutation in exon 1 of TNFRSF11A (RANK) was discovered in her two separate DNA samples (Figure 1A). This 15-bp duplication (87dup15) predicted an in-frame five amino acid extension (i.e. “pentapeptide”) in the signal peptide of RANK. The duplication was “shifted” 3-bp from the 15-bp duplication identified in ESH (84dup15),(7) but would encode the identical pentapeptide addition (Leu-Cys-Ala-Leu-Leu) (Figure 1B). Homozygosity for this mutation, or compound heterozygosity for a second TNFRSF11A defect, was excluded by the sequence analysis. Furthermore for RANK, we identified two non-synonymous SNPs [rs35211496 (exon 4, homozygous C/His) and rs1805034 (exon 6, homozygous C/Ala)] that perhaps influenced our patient’s phenotype (see Discussion). Three additional RANK SNPs [rs7238731 (heterozygous G/A, 5’UTR), rs1805033 (heterozygous T/C, 5’UTR), and synonymous SNP rs8092336 (homozygous G, Thr311Thr)] were also found.

Figure 1. TNFRSF11A Mutation Studies.

DNA sequence electropherograms A show (upper panel) the patient’s TNFRSF11A 15-bp duplication (87dup15), which is absent in her mother (lowest panel). Arrows indicate the beginning of the duplication. The PCR amplicon from the patient was cloned and re-sequenced to show the 15-bp duplication within one allele (middle panel). Black lines designate the duplicated sequence. RANK protein B is shown schematically with important domains above, and the domain sizes in amino acids (aa) below. Normal and mutant sequence of the signal peptide is provided below. The patient’s 15-bp tandem duplication and the duplications of our original ESH(7) and FEO(6) probands are illustrated in bold. Duplicated sequences are underlined. Boxed Leu indicates single amino acid difference between proband and ESH vs. the common FEO mutation.

Our patient also carried two SNPs in TNFSF11 encoding RANKL [rs2296533 (heterozygous T/C, synonymous) and rs2277439 (homozygous A, intronic)] that were considered inconsequential.

Her TNFRSF11A duplication was not found in the two DNA samples from her mother, and in the one DNA sample from her father.

In our two JPD patients reported in 2002 without TNFSF11B (OPG) mutations,(11) we found no mutation in TNFRSF11A (RANK) or TNFRSF11 (RANKL).

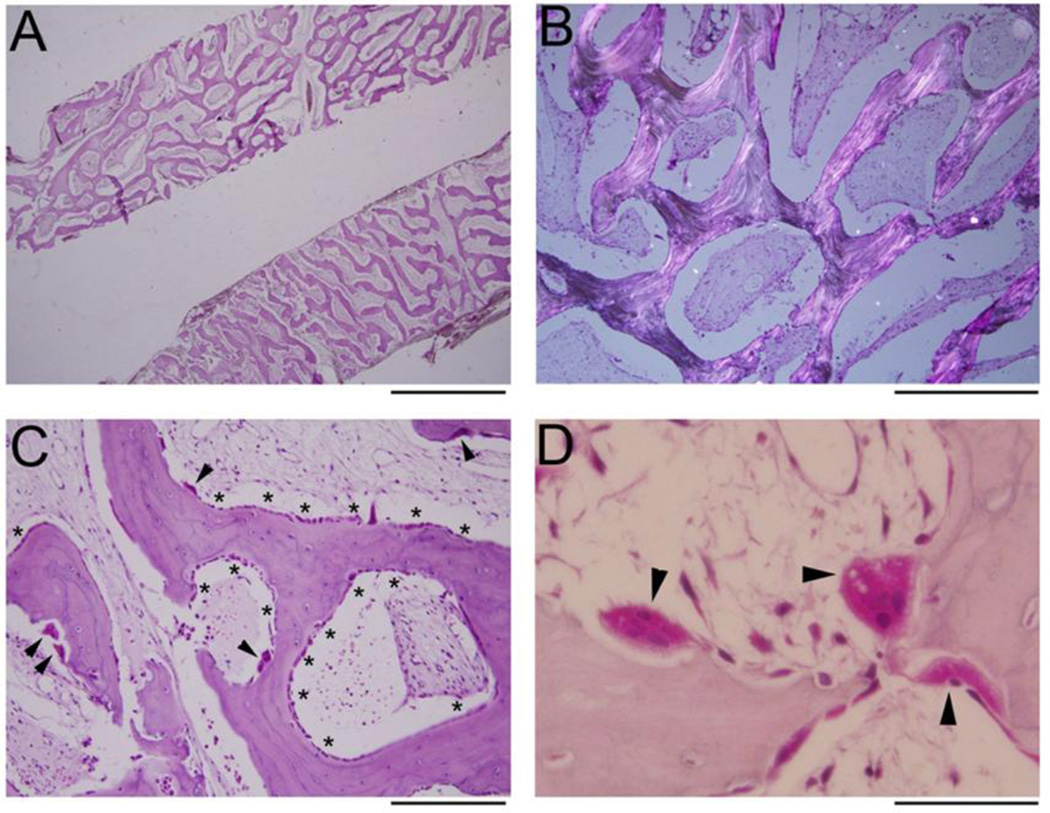

B) Histopathological Findings

The femur biopsy showed changes consistent with JPD, including no clear demarcation between cortical and trabecular bone (Figure 2A). There was no particular pattern, i.e., no parallel alignment,(21) of the trabeculae. Polarization microscopy showed mostly lamellar bone (Figure 2B). The network of osseous tissue was primarily covered by cuboidal osteoblasts (OBs) as well as by increased numbers of OCs (Figure 2C). No hematopoietic marrow was seen. Instead, the medullary space contained a richly vascularized, loose, and hypocellular fibroblastic stroma. The OCs showed appropriate cellular polarization and abundant ruffled borders (Figure 2D). Most OCs appeared adherent to bone, although in some areas retraction artifact was prominent. OC multinucleation did not appear increased (most had 2–5 nuclei). Overall, there was a highly porous interconnected meshwork of rapidly remodeling yet largely lamellar bone with active OBs and OCs. However, fluorescence labels were not observed, perhaps because doxycycline fluoresces poorly (Supplementary Appendix, Table 2).(22)

Figure 2. Femur Histopathology.

H&E stained sections of the decalcified femoral core biopsy show a meshwork of porous bone without distinction between cortical and trabecular bone A. Polarization demonstrates that the bone is mostly lamellar B and covered by osteoblasts (OBs, *s) and osteoclasts (OCs, arrowheads), with intervening hypocellular fibrous stroma C. OCs (arrowheads) are normally polarized and do not show hypermultinuclearity D. Scale bar 2 mm (A), 500 µm (B), 200 µm (C), 50 µm (D).

C) Pamidronate Therapy

PMD treatment spanned seven years (ages 4 – 11 years), involved nine cycles (Supplementary Appendix, Table 1), and was well tolerated except for one day of fever after the 3rd infusion. The yearly dose averaged approximately 2.7 – 3.0 mg/kg and, therefore, was considerably less than the 9 mg/kg/year that has been used for osteogenesis imperfecta in children.(23) With PMD treatment, our patient became less tired and had no fractures. However, yearly audiometry showed no improvement in her deafness, and by age 5 years she had prematurely lost four anterior teeth (two maxillary and two mandibular incisors) (see Dental Findings). At age 13 years, she no longer required a 1 cm shoe lift or limped, and she enjoyed gymnastics. She always grew at ~90th centile (Supplementary Appendix, Figure 2), and had not reported skeletal pain before, during, or after the PMD treatment.

D) Biochemical Findings

BTMs, usually assayed just before each PMD cycle, improved with the PMD treatment, but remained elevated (Supplementary Appendix, Table 1).

E) Radiological Findings

At 1 month-of-age, vertebral endplates were slightly dense (Supplementary Appendix, Figure 3A) and the right femur was short and bowed with some irregularity of the provisional zones of calcification best seen in the distal femur. There was some right tibial new bone formation likely from trauma (3B,C). However, the findings were not yet those of JPD.

At 1 year-of-age, “sandwich vertebrae” (dense end-plates) were apparent (Supplementary Appendix, Figure 4), but later this finding resolved. At age 1¾ years, fractures of the right radius and ulna involved abnormal bones. Radiographs at age 3 years showed both breaks had healed.

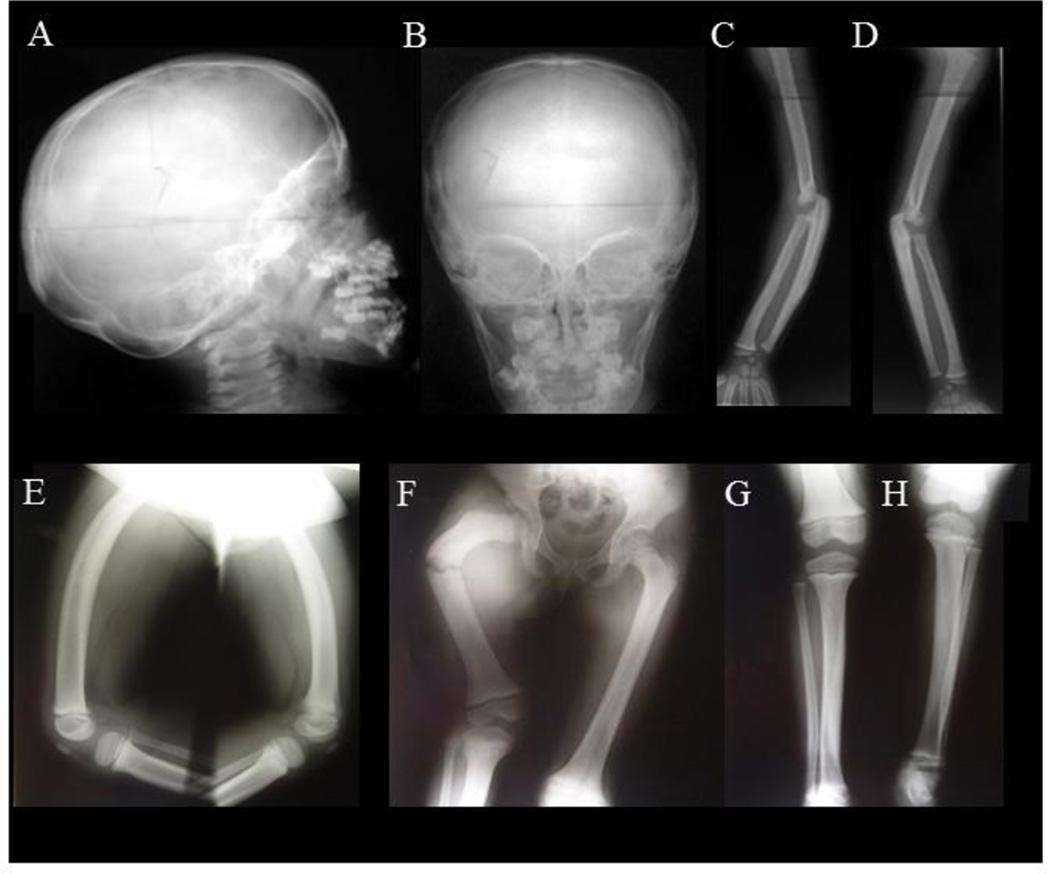

At 3 and 4 years-of-age (before PMD treatment), the skeletal changes became consistent with JPD. The skull showed thickening of its diploic space and sclerosis of its base and especially the orbital roofs and sphenoid (Figure 3A,B). The spine and ribs were mildly sclerotic, and the iliac bones were sclerotic medially. The long tubular bones had become wide with marked cortical thickening (“hyperostosis”) and coarse trabeculae (“osteosclerosis”) (Figure 3C–H).(24) In the upper limbs, cortical thickening was not uniform (Figure 3C). The medullary cavities were narrow. The olecranon fossas were shallow. The short tubular bones in the hands were hyperostotic and osteosclerotic, but without osteolytic expansions (Supplementary Appendix, Figure 4C). The lower extremity long bones had some bowing, but the cortical thickening was not uniform and was greatest at the deformity (Figure 3E–H).

Figure 3. Radiographic Findings Of JPD.

At age 3–2/12 years, lateral A and AP B radiographs of the patient’s skull show thickened diploic space, and sclerosis of the base and especially orbital roofs and sphenoid bones. In the limbs, between ages 2–5/12 and 3–2/12 years-of-age, the hands (Supplemental Appendix, Figure 4C) and portions of forearms developed overall sclerosis C,D. The cortices became thicker, the medullary cavities of the metacarpals narrower, and there was decreased tubulation in the metacarpals and phalanges. At age 3–2/12 years, the phalanges, radius, and ulna were more osteosclerotic with loss of differentiation between the cortex and medullary space. At age 3–8/12 years, the forearm long bones showed osteosclerosis, coarse trabeculae, cortical thickening, and narrow medullary cavities (most notable in the ulna). The proximal ulna was expanded. The olecranon fossa are shallow. Lateral views E show the femurs to be widened with anterior bowing, thickened cortices, and coarse trabeculation. At age 4 years, fracture occurred during biopsy of the short right femur F. The cortex had thickened considerably, and the medullary cavities were narrow in both femurs, tibias, and fibulas. Cortical thickening in the right femur is far greater than with “congenital short femur” G,H. The bones overall are osteosclerotic.

At age 9 years (after five years of PMD therapy), a skeletal survey showed significant overall improvement (Supplementary Appendix, Figure 5).

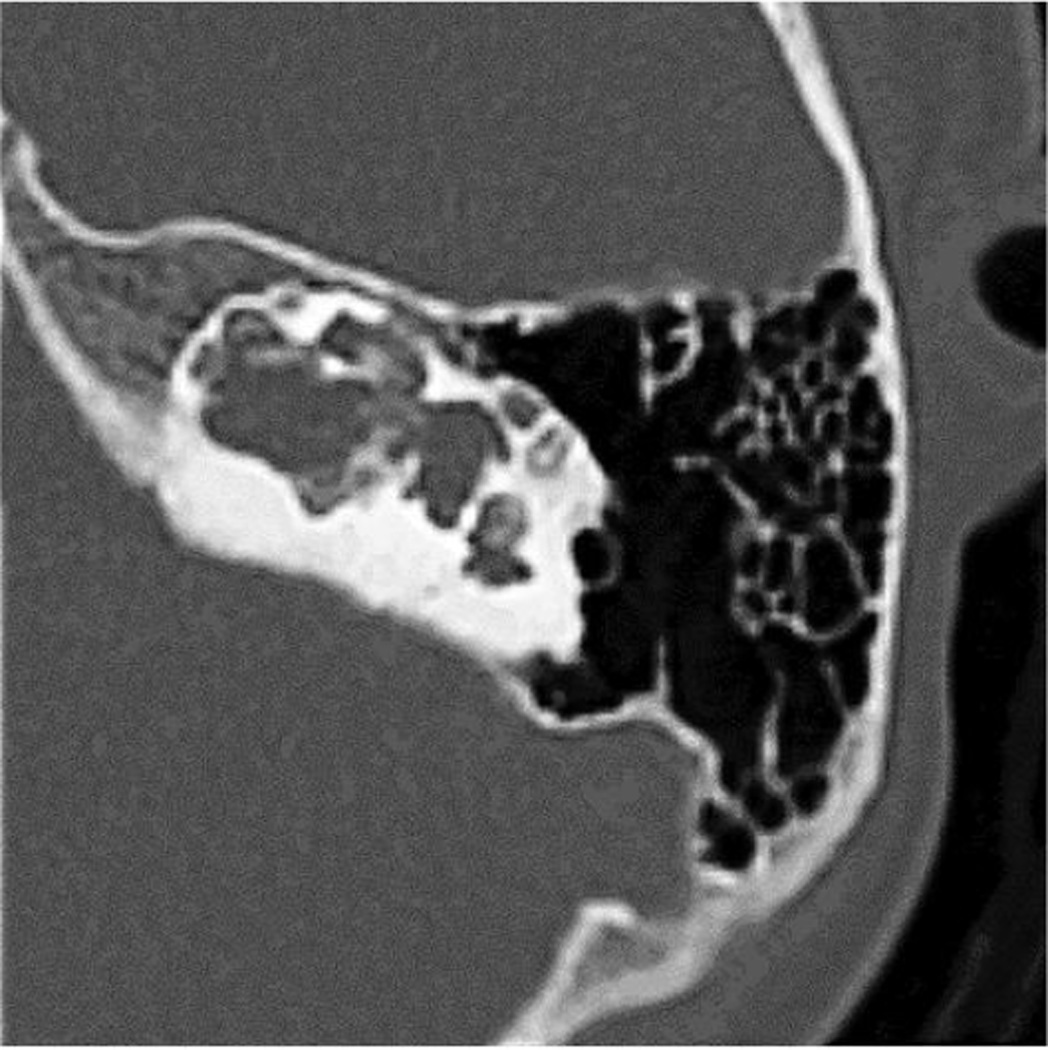

Bone scintigraphy at 3 years-of-age revealed increased tracer uptake in the upper maxilla, diffusely the radii, ulnae, femora, and tibiae, and a left rib focally (perhaps due to an old fracture) consistent with JPD (Supplementary Appendix, Figure 6A). However, at 6 and 10 years-of-age, follow-up studies were unremarkable (6B). DXA at age 7 years showed an unremarkable L2-L4 spine BMD z-score of + 0.38. Temporal bone CT studies at 7 and 11 years-of-age revealed a large dysplastic common cavity for the cochlea and vestibule (Figure 4). The middle ear cavities were large and contained tiny malformed ossicles. The posterior portions of the internal auditory canal were dilated, and the semicircular canal had a beaded appearance.

Figure 4. Computed Tomography.

Temporal bone CT studies at 7 and 11 (illustrated here) years-of-age show dysplastic, cystic changes of the inner ear.

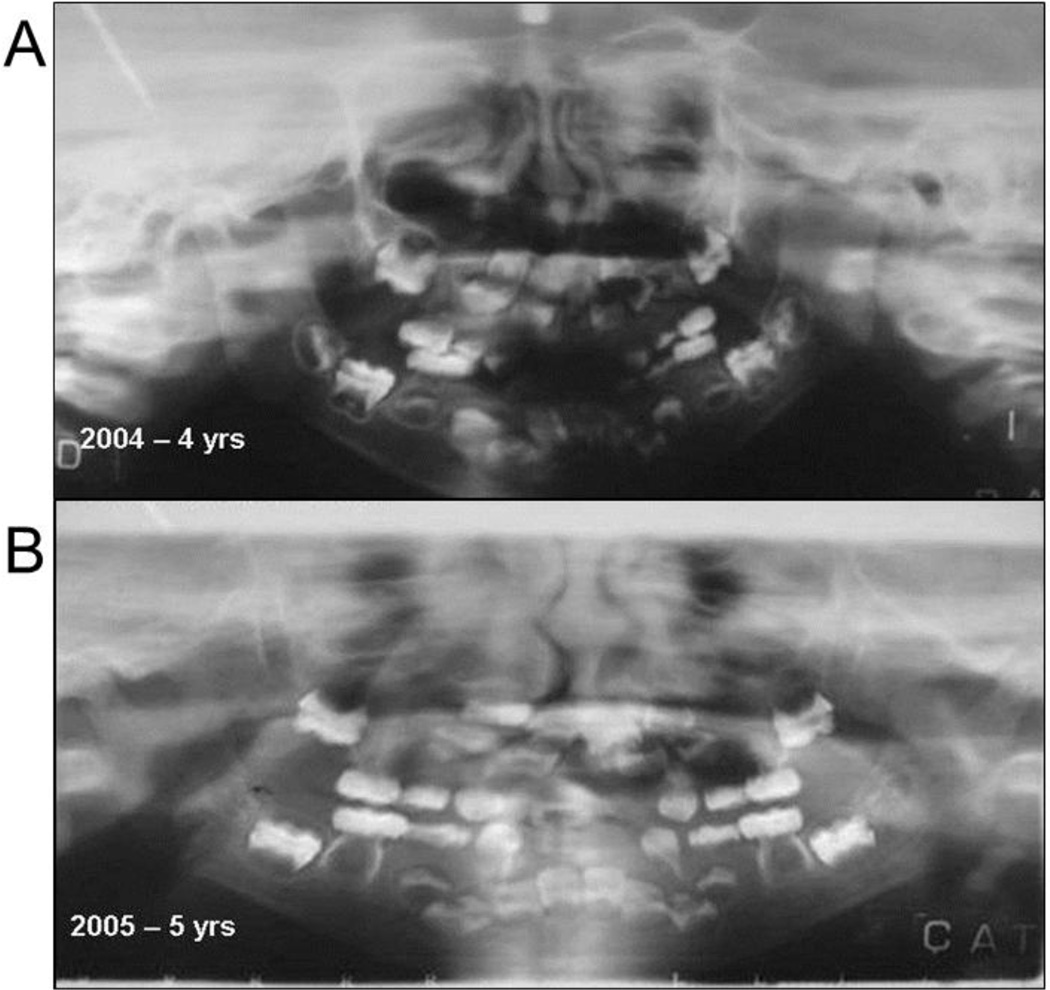

F) Dentition

Panorex examination at age 4 years showed incomplete tooth buds (Figure 5A). The roots appeared hypoplastic, although the periodontal membrane was present. Subsequently, malformed teeth, tooth roots, and tooth buds were absorbed. The first deciduous molars were resorbed, and the second deciduous molars had thin roots. The permanent teeth were un-erupted, diffusely shaped, poorly mineralized, and had large pulp chambers. The first permanent molars, that typically begin calcification near birth, were most affected. The lower permanent incisors showed hypomineralization. A fixed prosthesis (requested by a speech therapist) included steel crowns on the second deciduous molars where a palatal arch supported the replacements for her prematurely lost deciduous incisors. Both deciduous and permanent teeth were undergoing resorption.

Figure 5. Dental Findings.

Panorex radiographs of the patient at age 4 years A and 5 years (B) show progressive absorption of the apices and cervical portion (between the root and crown) of the teeth, with enlargement of pulp chambers.

At age 5 years, the prosthesis was removed because permanent teeth had erupted (Figure 5B). Due to rapid breakdown of tooth structures that caused severe pain, a permanent molar and both permanent upper incisors were extracted before complete eruption, but no histopathology was performed. One tooth with hypercementosis was extracted with part of the outer cortex at age 9 years (Supplementary Appendix, Figure 7).

At age 9 years, the remaining teeth manifested cervical and root resorption. Histology at age 10 years showed an incisor with crown destruction. External resorption was observed with erosional surfaces showing OCs and “compensatory cementosis”. The histopathological findings were consistent with JPD.

At age 11 years, there was no excessive tooth mobility in the remaining teeth. Severe resorption of the dentin and cementum involved the first molars, roots of the upper lateral incisors, and other teeth that had not erupted, including the mandibular canines and right lateral incisor. Bone tissue appeared to invade dental tissues. The patient was nearly edentulous. At age 13 years, she received complete dentures.

V) DISCUSSION

Our patient has no mutation in her TNFRSF11B (OPG) alleles, and yet her dento-osseous disease phenocopies JPD. Most JPD is caused by AR loss-of-function defects within TNFRSF11B,(13) but otherwise the etiology is unknown.(4) Instead, she carries a unique heterozygous 15-bp insertional tandem duplication within TNFRSF11A (RANK) that the related “exonic” disorders FEO, PDB2, ESH, and PEBD identify as gain-of-function.(4, 10) Our findings reveal for JPD a second genetic basis (i.e.; “JPD1” and now “JPD2”) and the potential for AD inheritance, and for the disorders of constitutive RANK activation a broader phenotype. Below, we discuss the implications of our observations for the diagnosis, prediction of recurrence risks and complications, and perhaps treatment choices among the mendelian disorders that represent activation of RANKL/OPG/RANK signaling.

A) Disorders of Constitutive RANK Activation

As a group, the disorders of constitutive RANK activation (FEO, PDB2, ESH, PEBD) can present from infancy to adult life.(4) Potential complications due to the enhanced osteoclastogenesis and rapid skeletal remodeling include deafness from destruction of middle ear bones,(25) episodic hypercalcemia,(26, 27) expansile osteolytic lesions that resemble advancing PDB1,(6) and high-turnover OP.(6) There can also be resorption of adult teeth(6) and osteosarcoma,(28, 29) and perhaps massive jaw tumors.(10)

In FEO, the clinical hallmark is a “wave” of osteolysis within one or more major long bones that gradually expands the entire structure causing pain, fracture, and deformity.(6) Eventually, this resorptive process “burns out”,(6) further resembling PDB1,(30) but instead produces a shell-like fat-filled bone(6) that is radiographically and histopathologically different from the hyperostotic and osteosclerotic “mosaic” bone of advanced PDB1.(30) Notably, all five reported FEO families carry the identical tandem duplication (84dup18) in TNFRSF11A. However, the family from Germany characterized in 1979 by Enderle and colleagues(28, 29) and from Northern Ireland reported in 2000 by Hughes et al(5) developed severe polyostotic osteolytic disease sometimes with sarcomatous degeneration, the American kindred detailed in 2002 by Whyte et al(6) was mildly affected and manifested mono-ostotic lytic disease without sarcoma, and the Spanish kindred described in 2002 by Palenzuela et al(31) rarely had focal osteolysis. Perhaps the American and Spanish FEO patients had better vitamin D status that restrained PTH secretion and OC activation compared to the German and Irish patients.(6) The two unrelated American women with FEO reported in 2003 by Johnson-Pais et al(32) had an expanded tibia from a novel 18-bp duplication in TNFRSF11A (83dup18), shifted 1-bp from the 84dup18 mutation, that nevertheless predicted the same hexapeptide extension in RANK common to all FEO patients. Most recently, an Iranian kindred with the 84dup18 mutation was reported in 2007 by Elahi et al.(33) They manifested skull and hand involvement, and hearing loss delineated in 2005 by Daneshi et al.(34) Haplotyping of FEO families indicated independent origins for the 84dup18 mutations.(33)

In contrast to FEO, PDB2 and ESH do not involve expansile osteolysis of major tubular bones, and there can be episodic hypercalcemia.(26, 27) PDB2 in Japan is caused by a 27-bp duplication (75dup27) in TNFRSF11A(5) and presents during puberty or early adult life with mild hearing impairment and tooth loss together with progressive radiologic changes(27) that resemble polyostotic PDB1.(30) There is also expansion of tubular bones in the hands, and striking sclerosis and widening of the maxilla and mandible.(27) Consideration of PDB2 as a distinct entity gained support in 2009 when Ke et al(35) reported a Chinese kindred with clinical features like Japanese PDB2,(27) but manifesting somewhat later in life, also with a 27-bp but novel tandem duplication (78dup27) in TNFRSF11A that would insert a unique nonapeptide into the signal sequence of RANK.

In contrast to FEO and PDB2, ESH is caused by a 15-bp tandem duplication (84dup15) in TNFRSF11A.(7) ESH features deafness as early as infancy together with widening (“undertubulation”), hyperostosis, and osteosclerosis of major long bones beginning during late childhood.(8) Soon after, there is loss of adult teeth from external cervical and apical resorption, as in FEO.(9)

Finally, panostotic expansile bone disease (PEBD), reported in a 32-year-old man from Mexico, is caused by a heterozygous 12-bp insertional tandem duplication (90dup12) in exon 1 of TNFRSF11A.(10) PEBD features early-onset deafness, bone deformities beginning in early childhood, massive benign jaw tumor formation during adolescence, and extraordinary expansion of the entire skeleton

B) Constitutive RANK Activation

RANK signaling in FEO, PDB2, and ESH has been investigated using transfection studies.(5, 36, 37) In 2000, Hughes et al(5) reported that diminished cleavage of the signal peptide from FEO-RANK (84dup18) and PDB2-RANK (75dup27) led to intracellular sequestration of the mutated receptor and enhanced NF-κB signaling. In 2011, Crockett et al(36, 37) confirmed that FEO-RANK (84dup18), PDB2-RANK (75dup27), and ESH-RANK (84dup15) resist signal peptide cleavage, showed that these altered receptors localized differently within the organized smooth endoplasmic reticulum (perhaps somehow explaining the distinctive clinical phenotypes), and were unresponsive to extracellular RANKL. Additionally, they found that overexpression of these mutated RANKs would activate NF-κB, whereas physiologic levels did not enhance down-stream RANK signaling, including NF-κB.(36, 37) In fact, these altered RANKs, when homozygous, inactivated such signaling. Crockett et al(37) offered that in FEO, PDB2, and ESH perhaps mixed trimers of mutant and wild type RANK interacted somehow to enhance RANK activity, although the mechanism for the differing phenotypes remained unknown.

C) Juvenile Paget’s Disease

Our findings add JPD as a fifth phenotype possible from constitutive activation of RANK, and therefore below we call JPD from OPG deficiency “JPD1” and from RANK activation “JPD2”.

The highest BTMs and the fastest skeletal remodeling of all disease seems to be found in JPD.(4, 21) Navajos with JPD1 are “OPG knockouts” from selective, complete, homozygous deletion of TNFRSF11B, and their skeletal problems featuring osteopenia, fractures, and deformities can manifest at birth and cause cardiopulmonary collapse by early adult life.(11) Other JPD1 patients present in childhood with somewhat more mild skeletal disease.(4, 16) This range in JPD expressivity is now understood to reflect the variety of mutations identified within the different functional domains of TNFRSF11B.(13, 38, 39)

In JPD, long bones during infancy can be osteopenic and expanded (“osteoectasia”), but later become hyperostotic and osteosclerotic.(4) The skeletal disease may lead to conductive and sensorineural deafness, bone pain, fractures, and osteosarcoma.(4) Although described only briefly in case reports,(40–49) dental disease too seems common in JPD.(4) Normal teeth have been reported,(41) but more often there are missing incisors,(43, 44) resorbed(45) or loose teeth, loss of lamina dura,(14, 46) premature exfoliation of deciduous teeth,(44) or delayed eruption of the dentition.(47–49) Dental abnormalities also accompany the apparently distinctive but unexplained form of JPD associated with mental retardation.(40) However, only JPD1 among the mendelian disorders of RANKL/OPG/RANK signaling leads to VMC,(4) which resembles this complication of pseudoxanthoma elasticum(14) (OMIM #177850, #254800)(3) and generalized arterial calcification of infancy(50) (OMIM #208000, #614473).(3) In JPD1, VMC causes retinal blindness in early adult life,(16) and perhaps carotid artery aneurysms during childhood.(15)

Most reports of JPD(4) (~ 60) predate the 2002 discovery of causal TNFRSF11B mutations.(11, 12) Subsequent publications, including several in which JPD patients were re-studied,(13, 16) typically revealed TNFRSF11B defects.(13, 38, 39, 51) Thus, JPD1 seems to be the most prevalent JPD.(4) However, we found here in our two unrelated JPD patients negative for TNFRSF11B (OPG) mutations,(11) no TNFRSF11A (RANK) or TNFSF11 (RANKL) defects. Accordingly, further genetic heterogeneity for JPD seems likely, perhaps involving genes downstream of RANK.

D) Our Patient Phenocopies JPD

Our patient’s unique 15-bp insertional duplication in TNFRSF11A (87dup15) predicts the RANK pentapeptide extension found in ESH,(7) yet her dento-osseous disease presented considerably earlier than in ESH, FEO, PDB2, and perhaps PEBD, and seemed destined without effective treatment to be more severe than these disorders. Her disease phenotype is, instead, most consistent with JPD.(4, 11) The daughter with ESH reportedly lost a tooth prematurely at age 4 years, but no dental problems were apparent at age 11 years when we described her teeth to be in good condition.(8) Cervical resorption of her teeth began after mouth trauma at age 12 years, when the dental histology resembled JPD.(9) Also, her skeletal disease presented at age 10 years when soon after a traumatic forearm fracture bone pain and “joint” swelling in her hands proved to be phalangeal expansion.(8) Notably, Chosich et al(26) reported in 1991 that her mother with ESH had mild JPD based primarily on radiographic and biochemical findings at age 30 years when hypercalcemia began while she breast-fed her daughter. The mother’s deafness began in infancy, and she had prematurely lost deciduous teeth, but her skeletal disease was discovered at age 11 years when hypercalcemia occurred during periods of illness or immobilization.(26) Then, she had increasing deafness, bone pain, and progressive thickening and deformity of her phalanges, femora, and tibiae that resembled JPD radiographically.(26) At age 28 years, root resorption prompted extraction of all her teeth.

In contrast to ESH, our patient’s skeletal problems, like her deafness, began early in life. Congenital bowing of her right femur suggested a fracture in utero, but the dysostosis proximal focal femoral deficiency or congenital short bowed femur (Gillespie & Torode, Group 1) was possible.(52) However, by 3 years-of-age radiographic findings consistent with JPD had appeared, absence of middle ear ossicles on CT explained her deafness, and severe symptomatic hypercalcemia had accompanied immobilization. By then, she also lacked some teeth or had resorption of entire tooth roots. Serum ALP determinations before PMD treatment were 1784, 2207, and 1394 IU/L (Nl, 150 – 550), and other BTMs were also several fold elevated, and therefore resembled JPD better than ESH. In fact, our three JPD1 patients (all homozygous for different TNFRSF11B mutations) had pretreatment serum ALP levels of 2716 IU/L (Nl, 110 – 320), 1232 IU/L (Nl, 150 – 420), and 720 IU/L (Nl, 185 – 383) at ages 1, 7, and 3 years, respectively, whereas the ESH daughter’s ALP at age 11 years was 778 IU/L (Nl, 130 – 550) although her other BTMs could be two fold elevated. (8)

E) SNP Modification of JPD2?

Although seemingly distinctive diseases can occur from different loss-of-function or gain-of-function mutations within a single gene,(53, 54) our patient’s TNFRSF11A duplication is predicted to insert the identical pentapeptide into RANK that causes ESH. Post-zygotic mosaicism seems unlikely because her skeletal disease was symmetrical and more severe than in ESH. Hence, we considered whether her several SNPs in TNFRSF11B and TNFRSF11A could be influencing her skeletal phenotype. In TNFRSF11B (OPG), she has a homozygous C/Asn at the Lys3Asn SNP (rs2073618) in exon 1. The G allele encoding Lys at this codon predisposes to sporadic PDB and familial PDB not caused by SQSTM1 mutation, and may pose a higher risk for females.(55, 56) Furthermore, this G allele is associated with lower BMD and increased risk for OP.(57, 58) These findings suggested functional differences for OPG with either Lys or Asn at amino acid #3. Our patient has, however, the “opposite” haplotype (homozygous C/Asn) that perhaps is protecting against PDB and low BMD. In contrast, her homozygous Asn OPG variant may be synergizing with her RANK mutation to exacerbate her dentoosseous disease. In TNFRSF11A (RANK), she carries two non-synonymous SNPs (rs35211496 His141Tyr and rs1805034 Ala192Val) considered potential risk factors for PDB.(59) She is homozygous for both alleles (C/His and C/Ala) associated with developing PDB. Other genetic variants linking TNFRSF11A with PDB(60) lie beyond the coding region/mRNA splice sites, and thus were not studied by our analysis.

F) Treatment

Once PMD therapy began for our patient at age 3 years, the natural history of her disease was “lost”. However, she carries no TNFRSF11B mutation, and therefore she should not develop the VMC from OPG deficiency featured in JPD1.(16) In FEO, ESH, PDB2, or PEBD involving constitutive activation of RANK, VMC has not been reported(4) Furthermore, amino-BP treatment has improved FEO,(6) PDB2,(61) ESH,(9) PEBD,(10) and JPD1,(16) and PMD therapy rapidly corrected our patient’s immobilization hypercalcemia, and long term treatment was associated with considerable skeletal improvement assessed with BTMs and radiographically. Unfortunately, her dental disease and deafness were apparently too advanced to benefit from anti-resorptive treatment, but we are uncertain if earlier intervention would have helped. Importantly, mutation analysis can now diagnose FEO, PDB2, ESH, PEBD, JPD1, and JPD2, and therefore preventative treatment seems possible.

Recently, the anti-RANKL monoclonal human antibody denosumab (Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA) has been given for JPD1 as a “substitute” for OPG.(62, 63) In one patient, severe hypocalcemia preceded favorable biochemical changes of skeletal remodeling.(62) Unfortunately, post-natal injections of recombinant OPG in OPG knockout mice did not prevent VMC,(64) and thus denosumab might not treat the VMC of JPD1. Denosumab is approved in the pediatric age group only for giant-cell tumors,(65) yet has been given for polyostotic fibrous dysplasia,(66) osteogenesis imperfecta,(67) and hypercalcemia following marrow cell transplantation for osteopetrosis.(68) For children, a worry has been the lymph node dysgenesis observed in RANKL knockout mice.(69) Furthermore, it is uncertain whether JPD2 and the other disorders of constitutive RANK activation will respond to denosumab. Intracellular trapping of the mutated RANKs in FEO, PDB2, ESH, PEBD, and JPD2 could resist extracellular denosumab,(36, 37) but one TNFRSF11A allele is intact in these disorders, and therefore some healthy RANK molecules should respond. In the future, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation or siRNA knock-down of mutated RANK(70) might treat these disorders.

G) Conclusions

Now, five seemingly distinctive “exonic” disorders are caused by constitutive activation of RANK: FEO, PDB2, ESH, PEBD, and JPD2. Each involves an insertional tandem duplication within exon 1 of TNFRSF11A that encodes the signal peptide of RANK. Whether additional duplications (e.g., 3-bp, 6-bp, 9-bp, 30-bp) will broaden or add to the number of phenotypes awaits discovery of such defects accompanied by detailed investigation of the patients and families.

When a patient of at least middle-age acquires deafness, tooth loss, focal osteolysis, and biochemical evidence of accelerated bone remodeling, PDB1 remains the likely explanation. However, if younger and with generalized high-turnover skeletal disease, mutation analysis of TNFRSF11A or TNFRSF11B will be important. Positive results would clarify the diagnosis, recurrence risks, and whether VMC might develop, and perhaps guide the choice of antiresorptive treatment that could possibly preserve hearing and teeth if started early in affected families.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Activating duplication of TNFRSF11A encoding RANK can associate with juvenile Paget’s disease.

Mutation analysis improves diagnosis, prognostication, etc. of heritable OPG/RANK disorders.

We expand the range of clinical phenotypes among the disorders of constitutive RANK activation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Ms. Vivienne McKenzie, Ms. Sharon McKenzie, and Mr. Vinieth Bijanki helped prepare our manuscript. Ms. Margaret Huskey assisted with the gene analyses.

Supported by the Shriners Hospitals for Children, The Clark and Mildred Cox Inherited Metabolic Bone Disease Research Fund, The Hypophosphatasia Research Fund, and The Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number DK067145. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Acronyms and Abbreviations

- AD

autosonial dominant

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- AR

autosomal recessive

- bp

base pair

- BTM

bone turnover marker

- CRT

creatinine

- DPD

deoxypyridinoline

- ESH

expansile skeletal hyperphosphatasia

- FEO

familial expansile osteolysis

- JPD

juvenile Paget’s disease

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-kappa B

- Nl

normal

- OP

osteoporosis

- OPG

osteoprotegerin

- PDB

Paget’s disease of bone

- PEBD

panostotic expansile bone disease

- PMD

pamidronate

- RANK

receptor activator of NF-κB

- RANKL

RANK ligand

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TNFSF11

TNF superfamily, member 11

- TNFRSF11A

TNF receptor superfamily, member 11A

- TNFRSF11B

TNF receptor superfamily, member 11B

- VMC

vascular microcalcification

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented in part at the 30th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, September 12 – 16, 2008, Montreal, Canada (J Bone Miner Res 23:S134, 2008).

Disclosures: The authors have no conflict of interest.

Contributions: All authors helped write and approved the manuscript. MPW coordinated patient data interpretation and manuscript creation. CT diagnosed, treated, and studied the patient. WHM detailed the radiological findings. XZ assisted with mutation analysis. DV and ES-A characterized the bone histopathology. VP delineated and treated the dental complications. SM performed mutation analyses, defined the TNFRSF11A defect, and helped discuss the molecular pathogenesis.

Contributor Information

Cristina Tau, Email: cristinatau1@yahoo.com.ar.

William H. McAlister, Email: mcalisterw@mir.wustl.edu.

Xiafang Zhang, Email: xiafang@prodigy.net.

Deborah V. Novack, Email: xiafang@prodigy.net.

Virginia Preliasco, Email: alfredo.preliasco@speedy.com.ar.

Eduardo Santini-Araujo, Email: santiniaraujo@laborpat.com.ar.

Steven Mumm, Email: smumm@dom.wustl.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Martin TJ. Paracrine regulation of osteoclast formation and activity: Milestones in discovery. J Musculoskel Neuron Interact. 2004;4:243–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyce BF, Xing L. Functions of RANKL/RANK/OPG in bone modeling and remodeling. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;473:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, OMIM®. McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD) 2014 May 10; World Wide Web URL: http://omim.org/

- 4.Whyte MP. Mendelian disorders of RANKL/OPG/RANK signaling. In: Thakker RV, Whyte MP, Eisman J, Igarashi T, editors. Genetics of Bone Biology and Skeletal Disease. San Diego, CA: Elsevier (Academic Press); 2013. pp. 309–324. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes AE, Ralston SH, Marken J, Bell C, MacPherson H, Wallace RG, Van Hul W, Whyte MP, Nakatsuka K, Hovy L, Anderson DM. Mutations in TNFRSF11A, affecting the signal peptide of RANK, cause familial expansile osteolysis. Nat Genet. 2000;24:45–48. doi: 10.1038/71667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whyte MP, Reinus WR, Podgornik MN, Mills BG. Familial expansile osteolysis (excessive RANK effect) in a 5-generation American kindred. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002;81:101–121. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whyte MP, Hughes AE. Expansile skeletal hyperphosphatasia is caused by a 15-base pair tandem duplication in TNFRSF11A encoding RANK and is allelic to familial expansile osteolysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:26–29. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whyte MP, Mills BG, Roodman GD, Reinus WR, Podgornik MN, Eddy MC, Gannon FH, McAlister WH. Expansile skeletal hyperphosphatasia: a new familial metabolic bone disease. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:2330–2344. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.12.2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsen CB, Tanghaitrong K, Chippendale I, Graham HK, Dahl HM, Stockigt JR. Tooth root resorption associated with a familial bone dysplasia affecting mother and daughter. Pediatr Dent. 1999;21:363–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schafer AL, Mumm S, Ivan El-Sayed I, McAlister WH, Horvai AE, Tom AM, Schaefer FV, Hsiao ED, Collins MT, Anderson MS, Whyte MP, Shoback DM. Panostotic expansile bone disease with massive jaw tumor formation and a novel mutation in the signal peptide of RANK. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:911–921. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whyte MP, Obrecht SE, Finnegan PM, Jones JL, Podgornik MN, McAlister WH, Mumm S. Osteoprotegerin deficiency and juvenile Paget's disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:175–184. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cundy T, Hegde M, Naot D, Chong B, King A, Wallace R, Mulley J, Love DR, Seidel J, Fawkner M, Banovic T, Callon KE, Grey AB, Reid IR, Middleton-Hardie CA, Cornish J. A mutation in the gene TNFRSF11B encoding osteoprotegerin causes an idiopathic hyperphosphatasia phenotype. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2119–2127. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.18.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mumm S, Banze S, Pettifor J, Tau C, Schmitt K, Ahmed A, Whyte MP. Juvenile Paget’s disease: molecular analysis of TNFRSF11B encoding osteoprotegerin indicates homozygous deactivating mutations from consanguinity as the predominant etiology. (abstract) J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:S388. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitsudo SM. Chronic idiopathic hyperphosphatasia associated with pseudoxanthoma elasticum. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53:303–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen CA, Hart BL, Taylor CL, Clericuzio CL. Bilateral cavernous internal carotid aneurysms in a child with juvenile Paget disease and osteoprotegerin deficiency. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:7–8. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whyte MP, Singhellakis P, Petersen MB, Davies M, Totty WG, Mumm S. Juvenile Paget’s disease: the second reported, oldest patient is homozygous for the TNFRSF11B “Balkan” mutation (966_969deltgacinsctt) which elevates circulating immunoreactive osteoprotegerin levels. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:938–946. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerr NM, Cassinelli HR, DiMeglio LA, Tau C, Tüysüz B, Cundy T, Vincent AL. Ocular manifestations of juvenile Paget disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:698–703. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sobacchi C, Frattini A, Guerrini MM, Abinun M, Pangrazio A, Susani L, Bredius R, Mancini G, Cant A, Bishop N, Grabowski P, Del Fattore A, Messina C, Errigo G, Coxon FP, Scott DI, Teti A, Rogers MJ, Vezzoni P, Villa A, Helfrich MH. Osteoclast-poor human osteopetrosis because of mutations in the gene encoding RANKL. Nat Genet. 2007;39:960–962. doi: 10.1038/ng2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guerrini MM, Sobacchi C, Cassani B, Abinun M, Kilic SS, Pangrazio A, Moratto D, Mazzolari E, Clayton-Smith J, Orchard P, Coxon FP, Helfrich MH, Crockett JC, Mellis D, Vellodi A, Tezcan I, Notarangelo LD, Rogers MJ, Vezzoni P, Villa A, Frattini A. Human osteoclast-poor osteopetrosis with hypogammaglobulinemia due to TNFRSF11A (RANK) mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sobacchi C, Schulz A, Coxon FP, Villa A, Helfrich MH. Osteopetrosis: genetics, treatment and new insights into osteoclast function. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9:522–536. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salmon P. Loss of chaotic trabecular structure in OPG-deficient juvenile Paget's disease patients indicates a chaogenic role for OPG in nonlinear pattern formation of trabecular bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:695–702. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pautke C, Vogt S, Kreutzer K, Haczek C, Wexel G, Kolk A, Imhoff AB, Zitzelsberger H, Milz S, Tischer T. Charachterization of eight different tetracyclines: advances in fluorescence bone labeling. J Anat. 2010;217:76–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whyte MP, McAlister WH, Novack DV, Clements KL, Schoenecker PL, Wenkert D. Bisphosphonate-induced osteopetrosis: novel bone modeling defects, metaphyseal osteopenia, and osteosclerosis fractures after drug exposure ceases. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1698–1707. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frame B, Honasoge M, Kottamasu SR. Osteosclerosis, hyperostosis, and related disorders. Elsevier Science Publishing Co.; 1987. pp. 1–375. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esselman GH, Goebel JA, Wippold FJ., II Conductive hearing loss caused by hereditary incus necrosis: a study of familial expansile osteolysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;114:639–641. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989670260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chosich N, Long F, Wong R, Topliss DJ, Stockigt JR. Post-partum hypercalcemia in hereditary hyperphosphatasia (juvenile Paget’s disease) J Endocrinol Invest. 1991;14:591–597. doi: 10.1007/BF03346877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakatsuka K, Nishizawa Y, Ralston SH. Phenotypic characterization of early onset Paget's disease of bone caused by a 27-bp duplication in the TNFRSF11A gene. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1381–1385. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.8.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Enderle A, von Gumppenberg S. Osteitis deformans (Paget) — or a tarda-type of a hereditary hyperphosphatasia. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1979;94:127–134. doi: 10.1007/BF00433578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Enderle A, Willert HG. Osteolytic-expansive type of familial Paget’s disease (osteitis deformans) Pathol Res Pract. 1979;166:131–139. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(79)80014-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whyte MP. Paget’s disease of bone (clinical practice) N Engl J Med. 2006;355:593–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp060278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palenzuela L, Vives-Bauza C, Fernández-Cadenas I, Meseguer A, Font N, Sarret E, Schwartz S, Andreu AL. Familial expansile osteolysis in a large Spanish kindred resulting from an insertion mutation in the TNFRSF11A gene. J Med Genet. 2002;39:e67. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.10.e67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson-Pais TL, Singer FR, Bone HG, McMurray CT, Hansen MF, Leach RJ. Identification of a novel tandem duplication in exon 1 of the TNFRSF11A gene in two unrelated patients with familial expansile osteolysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:376–380. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elahi E, Shafaghati Y, Asadi S, Absalan F, Goodarzi H, Gharaii N, Karimi-Nejad MH, Shahram F, Hughes AE. Intragenic SNP haplotypes associated with 84dup18 mutation in TNFRSF11A in four FEO pedigrees suggest three independent origins for this mutation. J Bone Miner Metab. 2007;25:159–164. doi: 10.1007/s00774-007-0748-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daneshi A, Shafeghati Y, Karimi-Nejad MH, Khosravi A, Farhand F. Hereditary bilateral hearing loss caused by total loss of ossicles: a report of familial expansile osteolysis. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26:237–240. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200503000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ke YH, Yue H, He JW, Liu YJ, Zhang ZL. Early onset Paget's disease of bone caused by a novel mutation (78dup27) of the TNFRSF11A gene in a Chinese family. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2009;30:1204–1210. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crockett JC, Mellis DJ, Scott DI, Helfrich MH. New knowledge on critical osteoclast formation and activation pathways from study of rare genetic diseases of osteoclasts: focus on the RANK/RANKL axis. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crockett JC, Mellis DJ, Shennan KI, Duthie A, Greenhorn J, Wilkinson DI, Ralston SH, Helfrich MH, Rogers MJ. Signal peptide mutations in RANK prevent downstream activation of NF-κB. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1926–1938. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chong B, Hegde M, Fawkner M, Simonet S, Cassinelli H, Coker M, Kanis J, Seidel J, Tau C, Tuysuz B, Yuksel B, Love D, Cundy T International hperphosphatasia collaborative group. Idiopathic hyperphosphatasia and TNFRSF11B mutations: relationships between phenotype and genotype. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:2095–2104. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.12.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naot D, Choi A, Musson DS, Kiper POS, Utine GE, Boduroglu K, Peacock M, DiMeglio LA, Cundy T. Novel mutations in the osteoprotegerin gene TNFRSF11B in two patients with juvenile Paget’s disease. Bone. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.07.034. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Golob DS, McAlister WH, et al. Juvenile Paget disease: life-long features of a mildly affected young woman. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:132–142. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650110118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eroglu M, Taneli NN. Congenital hyperphosphatasia (juvenile Paget's disease). Eleven years follow-up of three sisters. Annales de Radiologie. 1977;20:145–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Temtamy SA, El-Meligy MR, et al. Hyperphosphatasia in an Egyptian child. Birth defects original article series. 1974;10:196–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blanco O, Stivel M, et al. Familial idiopathic hyperphosphatasia: a study of two young siblings treated with porcine calcitonin. J Bone J Surg Br. 1977;59B:421–427. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.59B4.562883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eyring EJ, Eisenberg E. Congenital hyperphosphatasia. A clinical, pathological, and biochemical study of two cases. J Bone J Surg Am. 1968;50:1099–1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sreejan CK, Gopakumar N, Babu GS. Familial Chronic idiopathic hyperphosphatasias with unusual dental findings – A case report. J Clin Exp Dent. 2012;4:e313–e316. doi: 10.4317/jced.50878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caffey J. Familial hyperphosphatasemia with ateliosis and hypermetabolism of growing membranous bone; review of the clinical, radiographic and chemical features. Bul Hospital Joint Dis. 1972;33:81–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cassinelli HR, Mautalen CA, et al. Familial idiopathic hyperphosphatasia (FIH): response to longterm treatment with pamidronate (APD) Bone and Mineral. 1992;19:175–184. doi: 10.1016/0169-6009(92)90924-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Horwith M, Nunez EA, et al. Hereditary bone dysplasia with hyperphosphatasaemia: response to synthetic human calcitonin. Clinical Endocrinology. 1976;5(Suppl):341S–352S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1976.tb03843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tau C, Mautalen C, et al., editors. Chronic idiopathic hyperphosphatasia: normalization of bone turnover with cyclical intravenous pamidronate therapy. Bone. United States. 2004 doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Otero JE, Gottesman GS, McAlister WH, Mumm S, Madson KL, Kiffer-Moreira T, Sheen C, Millan JL, Ericson KL, Whyte MP. Severe skeletal toxicity from protracted etidronate therapy for generalized arterial calcification of infancy. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:419–430. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saki F, Karamizadeh Z, Nasirabadi S, Mumm S, McAlister WH, Whyte MP. Juvenile Paget’s disease in an Iranian kindred with vitamin D deficiency and novel homozygous TNFRSF11B mutation. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:1501–1508. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gillespie R, Torode IP. Classification and management of congenital abnormalities of the femur. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Br) 1983;65:557–568. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.65B5.6643558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Campeau PM, Lu JT, Sule G, Jiang MM, Bae Y, Madan S, Hogler W, Shaw NJ, Gibbs RA, Whyte MP, Lee BH. Whole exome sequencing identifies mutations in the nucleoside T-transporter gene SLC29A2 in dysosteosclerosis, a form of osteopetrosis. Human Molecular Genetics. 2012;21:4904–4909. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ozono K. Recent advances in molecular analysis of skeletal dysplasia. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1997;39:491–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.1997.tb03626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Daroszewska A, Hocking LJ, McGuigan FE, Langdahl B, Stone MD, Cundy T, Nicholson GC, Fraser WD, Ralston SH. Susceptibility to Paget's disease of bone is influenced by a common polymorphic variant of osteoprotegerin. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1506–1511. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beyens G, Daroszewska A, de Freitas F, Fransen E, Vanhoenacker F, Verbruggen L, Zmierczak HG, Westhovens R, Van Offel J, Ralston SH, Devogelaer JP, Van Hul W. Identification of sex-specific associations between polymorphisms of the osteoprotegerin gene, TNFRSF11B, and Paget's disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1062–1071. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.García-Unzueta MT, Riancho JA, Zarrabeitia MT, Sañudo C, Berja A, Valero C, Pesquera C, Paule B, González-Macías J, Amado JA. Association of the 163A/G and 1181G/C osteoprotegerin polymorphism with bone mineral density. Horm Metab Res. 2008;40:219–224. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1046793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao HY, Liu JM, Ning G, Zhao YJ, Zhang LZ, Sun LH, Xu MY, Uitterlinden AG, Chen JL. The influence of Lys3Asn polymorphism in the osteoprotegerin gene on bone mineral density in Chinese postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:1519–1524. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1865-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chung PY, Beyens G, Riches PL, Van Wesenbeeck L, de Freitas F, Jennes K, Daroszewska A, Fransen E, Boonen S, Geusens P, Vanhoenacker F, Verbruggen L, Van Offel J, Goemaere S, Zmierczak HG, Westhovens R, Karperien M, Papapoulos S, Ralston SH, Devogelaer JP, Van Hul W. Genetic variation in the TNFRSF11A gene encoding RANK is associated with susceptibility to Paget's disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2592–2605. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Albagha OM, Visconti MR, Alonso N, Langston AL, Cundy T, Dargie R, Dunlop MG, Fraser WD, Hooper MJ, Isaia G, Nicholson GC, del Pino Montes J, Gonzalez-Sarmiento R, di Stefano M, Tenesa A, Walsh JP, Ralston SH. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CSF1, OPTN and TNFRSF11A as genetic risk factors for Paget's disease of bone. Nat Genet. 2010;42:520–524. doi: 10.1038/ng.562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Riches PL, Imanishi Y, Nakatsuka K, Ralston SH. Clinical and biochemical response of TNFRSF11Amediated early-onset familial Paget disease to bisphosphonate therapy. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008;83:272–275. doi: 10.1007/s00223-008-9177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grasemann C, Schundeln M, Wieland R, Bergmann C, Wieczorek D, Zabel B, Schweiger B, Hauffa BP. Effects of RANK-ligand antibody (denosumab) treatment on bone turnover markers in a girl with juvenile Paget’s disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:3121–3126. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Polyzos SA, Singhellakis PN, Naot D, Adamidou F, Malandrinou FC, Anastasilakis AD, Polymerou V, Kita M. Denosumab treatment for juvenile Paget’s disease: results from two adult patients with osteoprotegerin deficiency (“Balkan” mutation in the TNFRSF11B gene) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:703–707. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Min H, Morony S, Sarosi I, Dunstan CR, Capparelli C, Scully S, Van G, Kaufman S, Kostenuik PJ, Lacey DL, Boyle WJ, Simonet WS. Osteoprotegerin reverses osteoporosis by inhibiting endosteal osteoclasts and prevents vascular calcification by blocking a process resembling osteoclastogenesis. J Exp Med. 2000;192:463–474. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Karras NA, Polgreen LE, Ogilvie C, Manivel JC, Skubitz KM, Lipsitz E. Denosumab treatment of metastatic giant-cell tumor of bone in a 10-year-old girl. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:e200–e202. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.4255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boyce AM, Chong WH, Yao J, Gafni RI, Kelly MH, Chamberlain CE, Bassim C, Cherman N, Ellsworth M, Kasa-Vubu JZ, Farley FA, Molinolo AA, Bhattacharyya N, Collins MT. Denosumab treatment for fibrous dysplasia. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:1462–1470. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Semler O, Netzer C, Hoyer-Kuhn H, Becker J, Eysel P, Schoenau E. First use of the RANKL antibody denosumab in osteogenesis imperfecta type VI. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2012;12:183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shroff R, Beringer O, Rao K, Hofbauer LC, Schulz A. Denosumab for post-transplantation hypercalcemia in osteopetrosis (letter to editor) N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1766–1767. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1206193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kong YY, Yoshida H, Sarosi I, Tan HL, TImms E, Capparelli C, Morony S, Oliveira dSA, Van G, Itie A, Khoo W, Wakeham A, Dunstan CR, Lacey DL, Mak TW, Boyle WJ, Penninger JM. OPGL is a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis, lymphocyte development and lymph-node organogenesis. Nature. 1999;397:315–323. doi: 10.1038/16852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Téletchéa S, Stresing V, Hervouet S, Baud'huin M, Heymann M-F, Bertho G, Charrier C, Ando K, Heymann D. Novel RANK antagonists for the treatment of bone-resorptive disease: theoretical predictions and experimental validation. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:1466–1477. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.