Abstract

Upregulation of the ERK1 and ERK2 (ERK1/2) MAP kinase (MAPK) cascade occurs in >30% of cancers1, often through mutational activation of receptor tyrosine kinases or other upstream genes, including KRAS and BRAF 2. Efforts to target endogenous MAPKs are challenged by the fact that these kinases are required for viability in mammals3,4. Additionally, the effectiveness of new inhibitors of mutant BRAF has been diminished by acquired tumor resistance through selection for BRAF-independent mechanisms of ERK1/2 induction2,5,6. Furthermore, recently identified ERK1/2-inducing mutations in MEK1 and MEK2 (MEK1/2) MAPK genes in melanoma confer resistance to emerging therapeutic MEK inhibitors, underscoring the challenges facing direct kinase inhibition in cancer7,8. MAPK scaffolds, such as IQ motif–containing GTPase activating protein 1 (IQGAP1)9,10, assemble pathway kinases to affect signal transmission11–13, and disrupting scaffold function therefore offers an orthogonal approach to MAPK cascade inhibition. Consistent with this, we found a requirement for IQGAP1 in RAS-driven tumorigenesis in mouse and human tissue. In addition, the ERK1/2-binding14 IQGAP1 WW domain peptide disrupted IQGAP1-ERK1/2 interactions, inhibited RAS- and RAF-driven tumorigenesis, bypassed acquired resistance to the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib (PLX-4032) and acted as a systemically deliverable therapeutic to significantly increase the lifespan of tumor-bearing mice. Scaffold-kinase interaction blockade acts by a mechanism distinct from direct kinase inhibition and may be a strategy to target overactive oncogenic kinase cascades in cancer.

Intracellular scaffold proteins interact with kinases and other signaling molecules to control signal transduction11–13. IQGAP1 is a scaffold that is known to interact with RAF, MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 MAPK cascade kinases, as well as with a host of other proteins9,10,15. Some studies have suggested a role for IQGAP1 in enhancing tumorigenesis16–19, but Iqgap1 knockout mice are viable and fertile20, do not show any defects in normal epithelium and heal wounds normally (Supplementary Fig. 1). Thus, IQGAP1 is a potential tumor-required scaffold protein that is dispensable for homeostasis.

To further explore this possibility functionally, we examined the susceptibility of Iqgap1-null mice to tumor formation in a model of RAS-driven cancer. We observed that Iqgap1 knockout mice were resistant to Hras-driven chemical carcinogenesis21 (Fig. 1a,b and Supplementary Fig. 2). Iqgap1 heterozygotes showed an intermediate phenotype, suggesting an Iqgap1 gene-dosage effect on tumor susceptibility (Fig. 1). Iqgap1 knockout mice also had a sixfold reduction in premalignant epidermal hyperplasia in response to acute Ras-MAPK induction22 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Expression profiling of the skin of these mice demonstrated that Iqgap1 is required for Ras-driven induction of genes enriched in cellular metabolism Gene Ontology terms (Supplementary Fig. 4) that are characteristic of early Ras-MAPK–driven tumorigenesis23. Iqgap1 knockout mice did not differ substantially from wild-type mice in the expression of known Iqgap1 binding partners, suggesting that Iqgap1 is not required for their expression (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Diminished tumorigenesis in Iqgap1 knockout mice. (a) Representative clinical appearance of tumors in mice wild type (left), heterozygous (middle) or null (right) for Iqgap1 over time as indicated (two mice in each group are shown at each time point). Scale bar, 5 mm. (b) Quantification of the formation of the tumors in a over time. Color bars denote tumor volume, as indicated in the legend; abortive papillomas <1 mm3 are not shown (n = 7 mice per genotype). TPA, 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate.

We then assessed Iqgap1 expression in spontaneous human epidermal cancers to examine the corresponding human skin cancer. Iqgap1 protein was strongly expressed in 45% of human squamous cell carcinomas (n = 60) (Supplementary Fig. 5), consistent with reports in other cancers24,25. In a mouse model26 of human KRAS-driven pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma27, we found that the amount of Iqgap1 protein is increased in pre-neoplasms and advanced tumors (Supplementary Fig. 6). To further explore the effects of Iqgap1 in human tissue, we depleted Iqgap1 in RAS-driven organotypic human epidermal neoplasia28, a setting that reflects corresponding human cancers, and found that Iqgap1 depletion impaired basement membrane degradation and neoplastic invasion (Fig. 2a). Similarly to in mice, IQGAP1-deficient human epidermis was normal, in contrast to the severe hypoplasia seen in ERK1/2-deficient tissue (Supplementary Fig. 7). Although hypoplasia induced by loss of ERK1/2 has been shown to be associated with reduced cyclin B1 and c-Fos expression leading to G2/M arrest4, their expression remains unchanged with Iqgap1 loss. Total ERK1/2 depletion led to hypoplastic tissue collapse in RAS-driven organotypic neoplasia, whereas depletion of Iqgap1 preserved tissue morphology (Fig. 2b). Although both total and activated phosphorylated ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) were absent in ERK1/2-depleted tissue, IQGAP1-deficient tissue retained some pERK1/2, indicating that Iqgap1 loss down-regulates pERK1/2 but does not eliminate it (Fig. 2b), an effect that is rescued by Iqgap1 re-expression (Supplementary Fig. 8). Further, Iqgap1 depletion diminished downstream ERK1/2 cascade activity (Supplementary Fig. 9). Iqgap1 depletion thus lowers the amounts of active ERK1/2 and impedes neoplasia without inducing tissue catastrophe.

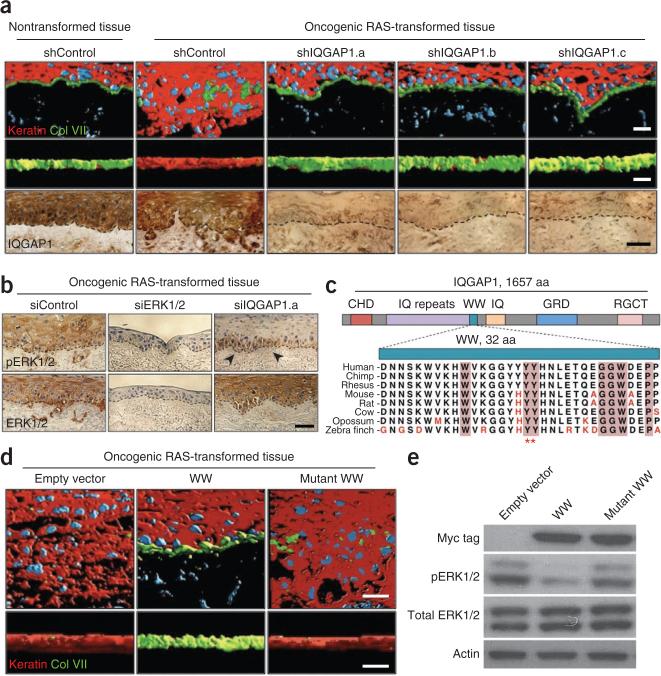

Figure 2.

The ERK-binding WW domain of IQGAP1 inhibits RAS-driven invasion in human tissue. (a) Confocal stack images showing the expression of keratin (red), basement membrane protein type VII collagen (Col VII; green) and the nuclei of keratinocytes and fibroblasts (blue) of RAS-driven organotypic human epidermal neoplasia treated with shRNAs targeting scrambled control (shControl) or IQGAP1 (shIQGAP1.a, shIQGAP1.b and shIQGAP1.c). The images are shown on the x-y plane (top) or the z-x plane (middle); note the blockade of invasive destruction of the basement membrane by tissue depletion of IQGAP1. Scale bars (top and middle), 25 μm. On the bottom is immunohistochemistry staining for IQGAP1. The black dashed lines denote the basement membrane separation of the epidermis and underlying dermis. Scale bar (bottom), 25 μm. (b) Immunohistochemistry staining for pERK1/2 (top) and total ERK1/2 (bottom) of the tissue in a treated with siRNAs targeting a nonfunctional control (siControl), ERK1/2 (siERK1/2) or IQGAP1 (siIQGAP1.a) sequence. Black arrowheads denote residual pERK staining in siIQGAP1.a-treated tissue. The black dashed lines denote the basement membrane. Scale bar, 25 μm. (c) Cross-species conservation of the IQGAP1 WW domain; divergent amino acids are listed in red. Pink shading indicates highly conserved residues across the WW domains from multiple proteins. Red asterisks denote residues mutated in the mutant WW domain construct. aa, amino acids. (d) Confocal stacks colored as in a after treatment with lentivirus corresponding to empty vector control, the IQGAP1 WW domain (WW) or the WW domain mutant with mutation of the two tyrosine residues noted in c (mutant WW). Scale bars, 25 μm. (e) Immunoblots for the Myc tag, pERK1/2 and total ERK1/2 in the cells in d. Cell lysates were also probed with antibodies to actin to verify equal loading.

The effects of Iqgap1 on pERK1/2 suggested that the anti-neoplastic effects of Iqgap1 loss may occur through alterations in ERK1/2. Iqgap1 binds ERK1/2 through its highly conserved WW domain (Fig. 2c). Although other Iqgap1 domains are known to bind multiple partners in other signaling pathways15, ERK1/2 are the only known proteins that have been confirmed to bind the IQGAP1 WW sequence14. Moreover, WW-deleted Iqgap1 mutants do not rescue IQGAP1-mediated effects on pERK1/229. Similarly to scaffold loss, increased scaffold concentrations can also alter signaling pathways by titrating binding partners away from one another12,13, and both overexpression and knockdown of IQGAP1 show similar effects on signal transduction29. We therefore used the ERK1/2-binding WW sequence as an approach to target IQGAP1-ERK1/2 interactions. Similarly to IQGAP1 depletion, lentiviral expression of a Myc-tagged WW sequence inhibited neoplastic invasion in organotypic neoplasia (Fig. 2d,e and Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9). Substitution of two conserved WW-domain tyrosines to alanine (Fig. 2c) abolished this effect (Fig. 2d,e and Supplementary Fig. 8).

To characterize the action of the IQGAP1 WW domain in additional cancer cell types, we delivered it by lentivirus to cancer cell lines with mutational RAS-MAPK pathway activation (MDA-MB-468, HCT-116 and COLO-829), as well as to cancer cell lines with a wild-type MAPK module (T-47D, COLO-320DM and CHL-1) (Supplementary Fig. 10a,b). The WW domain markedly impaired the proliferation of breast, colorectal and melanoma tumor cells characterized by EGFR overexpression, KRAS mutation and BRAF mutation, respectively, without affecting wild-type MAPK lines (Supplementary Fig. 10c,d). Moreover, the WW domain impaired migration of the MAPK mutant lines with no effect on wild-type lines (Supplementary Fig. 10e–h). We did not find any changes in IQGAP1, IQGAP2 or IQGAP3 expression levels in these cells (Supplementary Fig. 11). To further explore selectivity, we used melanoma cancer cell lines previously characterized to express either the BRAFV600E or NRASQ61L mutant (COLO-829 and MM-485, respectively), as well as a control melanoma line with wild-type BRAF and NRAS (CHL-1). IQGAP1 WW domain delivery impaired tumorigenesis in the BRAF- and NRAS-mutant cells but not in RAS-MAPK wild-type tumor cells (Supplementary Fig. 12), again suggesting a selective inhibitory effect on neoplasias characterized by mutations upstream of ERK1/2 in the RAS-MAPK pathway. We then performed intratumoral lentiviral injection to determine whether the WW domain can act on established tumors. Subcutaneous tumors derived from human MAPK-mutant breast and melanoma skin cancer cell lines (MDA-MB-468 and COLO-829, respectively) treated with WW lentivirus ceased to grow, whereas control lentivector–injected tumors continued to expand (Supplementary Fig. 13). The IQGAP1 WW sequence thus exerts anti-neoplastic effects on not only MAPK pathway–mutant early stage tumors but also established tumors.

To test the antitumor activity of the IQGAP1 WW peptide itself, we rendered the 32-residue WW peptide cell and tissue penetrating by adding eight arginine residues in an approach that mimics HIV TAT sequence function30. WW peptide, but not scrambled peptide control, abolished neoplastic invasion in RAS-driven organotypic neoplasia (Fig. 3a). The WW peptide reduced the amounts of pERK1/2 in oncogenic RAS-transformed keratinocytes and MAPK-mutant cancer cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 14) and impaired the growth of human pancreatic cancer cell lines characterized by mutant KRAS (Supplementary Fig. 15). Further, systemic WW peptide delivery by osmotic pump impaired tumorigenesis in mice bearing SK-Mel-28 melanoma tumors, as well as those bearing MDA-MB-468 breast tumors (Supplementary Fig. 16). We did not find any morbidity or substantial laboratory abnormalities in WW peptide–treated mice (Supplementary Table 2).

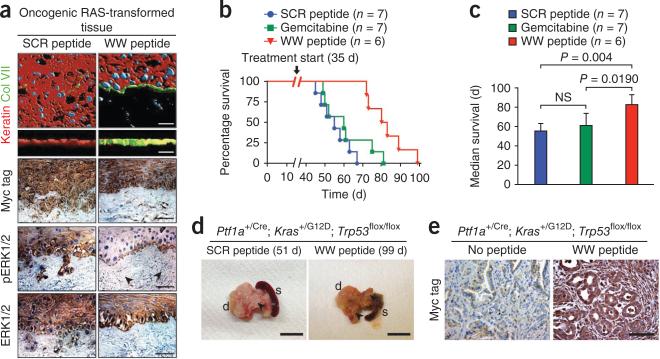

Figure 3.

Exogenous WW peptide delivery inhibits neoplastic invasion and diminishes tumorigenesis in vivo. (a) Expression of keratin (red), basement membrane protein type VII collagen (green) and the nuclei of keratinocytes and fibroblasts (blue) of RAS-driven organotypic human epidermal neoplasia treated with 10 μM Myc-tagged scrambled control (SCR peptide) or 10 μM Myc-tagged IQGAP1 WW (WW peptide) daily. Images are shown in the x-y plane (first row) or the z-x plane (second row). Also shown is immunohistochemistry staining for the Myc tag (third row), pERK1/2 (fourth row) and total ERK1/2 (fifth row). Black arrowheads denote residual pERK staining in WW peptide tissue. All scale bars, 25 μm. (b) Survival of 35-day-old Ptf1a+/Cre; Kras+/G12D; Trp53flox/flox mice with established tumor burden and palpable pancreas mass randomized to receive WW peptide (WW), scrambled peptide placebo (SCR) or gemcitabine by intraperitoneal injection. (c) Median survival of the mice in b. Statistical significance was calculated by log-rank test. NS, not significant. Data are shown as the mean ± s.d. (d) Clinical images of tumors from the mice in b. Scale bars, 1 cm. Black arrowheads denote tumor nodules. s, spleen; d, duodenum. The WW peptide–treated tumor is from day 99, and the SCR-treated control tumor is from day 51. (e) Immunohistochemistry staining for the Myc tag of tissue from the mice in b along with an untreated control mouse.

We next treated Ptf1a+/Cre; Kras+/G12D; Trp53flox/flox mutant mice, which develop lethal pancreatic cancer26, with the WW peptide starting at 35 days of age, when palpable tumor mass was present. Compared to treatment with scrambled peptide or gemcitabine, which is commonly used in human pancreatic cancer, WW treatment significantly extended lifespan (Fig. 3b,c and Supplementary Table 3). Visual and histopathological analysis indicated that although WW-treated mice eventually die from pancreatic tumors, these tumors show reduced amounts of pERK1/2, suggesting that the WW peptide sustains inactivation of the Ras-MAPK pathway (Fig. 3d,e and Supplementary Fig. 17). Thus, systemically delivered Iqgap1 WW peptide shows marked antitumor activity without detectable toxicity.

The newly available kinase inhibitor vemurafenib (PLX-4032) targets mutant BRAFV600E MAP3K in melanoma; however, its long-term effectiveness has been hindered by acquired resistance through bypass mechanisms that can restore ERK1/2 activation2,5,6,8. If the WW domain acts in a mechanistically distinct fashion from direct kinase inhibition, then the effects of the WW peptide should be unaltered by acquired resistance to BRAF inhibition. We therefore compared the impact of the WW peptide on PLX-4032–sensitive and –resistant melanoma lines. Three PLX-4032–sensitive BRAFV600E-expressing parental human melanoma cancer cell lines, which are all sensitive to the WW peptide (Fig. 4a,b; COLO-829, SK-Mel-28 and A375), were rendered resistant to PLX-4032 as described5,6. Resistance of the resulting subclones to PLX-4032–mediated growth inhibition (Fig. 4c,d) was accompanied by alterations that have been previously associated with the emergence of PLX-4032 resistance5,6, including alterations of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1-R), platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β (PDGFR-β), NRAS and COT (also called MAP3K8) (Supplementary Fig. 18). In all cases, the WW peptide inhibited the growth of PLX-4032–resistant melanoma subclones (Fig. 4c) similarly to in PLX-4032–sensitive parental cells (Fig. 4a), indicating that the WW domain acts in a non-redundant fashion to direct kinase inhibition.

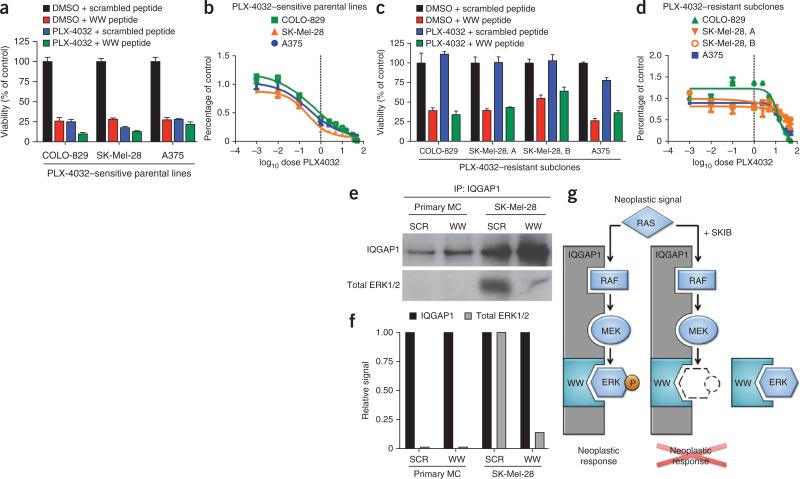

Figure 4.

Exogenous WW peptide bypasses PLX-4032 resistance. (a) Viability of PLX-4032–sensitive BRAFV600E melanoma parental cell lines treated with DMSO, 5 μM PLX-4032, 10 μM scrambled peptide or 10 μM WW peptide, as indicated. (b) Dose response of the cells in a to increasing doses of PLX-4032 (0–50 μM). (c) Viability of PLX-4032–resistant subclones derived from the parental lines in a treated with DMSO, 5 μM PLX-4032, 10 μM scrambled peptide or 10 μM WW peptide, as indicated. (d) Dose response of the cells in c to increasing doses of PLX-4032 (0–50 μM). Data (a–d) are shown as the mean ± s.d. (e) Immunoprecipitation (IP) of IQGAP1 protein and associated ERK1/2 from human primary melanocytes (MC) or BRAFV600E SK-Mel-28 melanoma cells after daily treatment with 10 μM scramble control (SCR) or WW peptide for 6 d. (f) Quantification of the relative amounts of ERK1/2 as a function of the immunoprecipitated IQGAP1 in e. (g) Model of WW-mediated SKIB action in RAS-MAPK–hyperactive cancer. In untreated cancer cells (left), Iqgap1 scaffolds RAF, MEK and ERK MAPKs and facilitates neoplasia-enabling signal transduction. In the presence of WW SKIB (right), ERK MAPK is sequestered away from the IQGAP1 scaffold, the amounts of pERK1/2 are diminished and neoplastic response is attenuated.

To further explore the mechanism of WW peptide action, we next characterized its effects on IQGAP1-ERK binding in primary melanocytes and BRAFV600E-expressing human melanoma cancer cells. The WW peptide substantially decreased the amounts of total ERK1/2 bound to IQGAP1 in cancer cells (Fig. 4e,f). Notably, very little ERK1/2 was associated with IQGAP1 in primary cells, whereas there was much more ERK1/2 bound to IQGAP1 in cancer cells (Fig. 4e,f and Supplementary Fig. 19). The Iqgap1 WW sequence thus blocks scaffold-kinase interactions between IQGAP1 and ERK1/2.

Here we show that the IQGAP1 scaffold is required for tumorigenesis but is dispensable for homeostasis and the IQGAP1 WW sequence blocks neoplasia without inducing the tissue collapse accompanying ERK1/2 ablation. We also present a working model of the resulting scaffold-kinase interaction blockade (SKIB) in cancer (Fig. 4g). The WW peptide inhibited tumorigenesis in cells from diverse tissues, all of which were characterized by RAS-MAPK pathway activation at a variety of pathway levels, ranging from upstream receptor tyrosine kinases to commonly mutated RAS and RAF genes. Exogenous WW peptide bypassed acquired resistance to vemurafenib (PLX-4032)5,6, a recently approved treatment of BRAFV600E melanoma, suggesting that this approach may be explored in tumors with acquired resistance to RAS-MAPK pathway–targeted drugs. Systemic delivery of a tissue- penetrating Iqgap1 WW peptide impaired growth of established tumors and increased the lifespan of tumor-bearing mice without detectable toxicity. These data support future efforts at therapeutic targeting of scaffold-kinase interactions as a tumor-selective strategy to inhibit oncogenic signaling in cancer.

ONLINE METHODS

Mouse handling and genotyping

All mouse husbandry and experimental procedures were performed in accordance and compliance with policies approved by the Stanford University Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care (Khavari lab protocol #9863 or Sage lab protocol #13565). Mice were housed and bred under standard conditions with food and water provided ad libitum and maintained on a 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle. Iqgap1 knockout mice were maintained in a C57BL/6 and 129 mixed background20. Genotyping was performed using genomic DNA isolated from mouse tails in Direct PCR lysis regent (Viagen). The primers used for gene amplification were p5, 5′-TTGCAGTCTGTGGCATGTG-3′ and p3, 5′-CCTGCTGACAGGTCAATGAT-3′ for the wild-type Iqgap1 allele or p5, 5′-TTGCAGTCTGTGGCATGTG-3′ and pNeo, 5′-CCTGCTCTTTACTGAAGGCT-3′ for the neomycin cassette, as previously described20. K14-ER:RAS transgenic mice, Jax stock number 006403, were kept in a 129/SvEv background22. This line was crossed to Iqgap1 knockout mice and subsequently backcrossed to C57BL/6 and 129 wild-type mice. The ER:RAS transgene was detected with the following primers: forward, 5′-CACCACCAGCTCCACTTCAGCACATT-3′ and reverse, 5′-CGCACCAACGTGTAGAAGGCATCCTC-3′. KRAS+/LSL–G12D (ref. 31), Ptf1a+/Cre (ref. 32) and p53flox/flox (ref. 33) mice were maintained as previously described.

Wound healing

Two round, full-thickness excision wounds 6 mm in diameter were made on the dorsal skin of anesthetized 6- to 8-week-old mice using sterile biopsy punches. Untreated wounds were measured for closure and photographed at least once every 3 d. Percentage wound closure was calculated as the wound area remaining over the initial wound size.

7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA) and TPA chemical carcino-genesis

Skin carcinogenesis was as previously described34. Briefly, the backs of anesthetized 8- to 10-week-old mice were shaved and treated two times (3 d apart) with application of DMBA (Sigma; 10 μg in 100 μl acetone) followed by twice weekly application of TPA (Sigma; 12.5 μg in 100 μl acetone). Tumors were observed twice per week for 30 weeks and recorded by photography and caliper measurements of length, width and height. Tumor volume was estimated using the formula 4/3π(r1r2r3), where r1 is the radius of length, r2 is the radius of width and r3 is the radius of height. Gender-matched littermates were used for all experiments.

Acute oncogenic RAS

Exposure to acute oncogenic RAS was as previously described22. Briefly, the lower backs of anesthetized 6- to 8-week-old mice were shaved and treated for 6 d with once-daily application of 1 mg 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT; Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.1 ml ethanol to activate the ER:RAS transgene. Relative hyperproliferation was quantified by the thickness of the interfollicular epidermis from the basal layer to the top of the cornified layer using a micrometer and measured ten times across three independent fields of view. Values were normalized to control untreated wild-type mouse skin. Gender-matched littermates were used for all experiments.

Gene expression profiling

Fragmented complementary RNA was hybridized to the Mouse Gene 1.0 ST Array (Affymetrix). For microarray gene expression analysis, arrays were robust multiarray average (RMA) normalized, and differential expression was defined using a fold change of at least four after 6 d of topical treatment with 4-OHT compared to untreated samples. A total of 402 genes were identified as the most significantly differentially expressed between K14-ER:HRASG12V Iqgap1+/+ and Iqgap1–/– mice. Pathway analysis was then performed using DAVID. Gene expression data are deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession code GSE44967.

Isolation and culture of primary human cells and human cancer cell lines

Primary human epidermal keratinocytes and melanocytes as well as dermal fibroblasts were isolated from discarded neonatal surgical specimens and cultured as previously described28. Human cancer cell lines were maintained in DMEM or RPMI (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS or FCS according to recommendations from ATCC.

Human tissue model system

Human tissue was regenerated as previously described28. Briefly, stromal primary human fibroblasts were seeded onto devitalized human dermis and subsequently elevated to a sterilized annular dermal support (ADS) tissue culture insert device28. Primary keratinocytes were transduced with viral constructs as previously described28. These cells were then seeded to the air-liquid interface of the upper chamber of the ADS insert, with the medium changed daily. In response to 4-OHT (Sigma; 100 nM in ethanol), cells expressing inducible ER-HRASG12V invaded into the underlying dermis within ~5 d. Immunofluorescence was performed as previously described3. Microscopy was performed on an Olympus FV1000 scanning laser confocal microscope. For each sample, 30 sequential Z sections were taken in three channels (DAPI: 405 nm/450 nm (excitation/emission); FITC: 488 nm/ 512 nm; and TRITC: 540 nm/570 nm), allowing for subsequent three-dimensional reconstruction analysis. Image analysis and three-dimensional reconstruction were performed using Improvision Volocity software (PerkinElmer). The x-y planes are shown in three-color images (red, green and blue), and the z-x planes are restricted to two colors (red and green) for ease of viewing effects on the basement membrane. The relative invasion index was quantified as the number of keratin-positive epithelial cells below the collagen-positive basement membrane measured ten times across three independent fields of view.

IQGAP1 knockdown vectors

The siRNA oligonucleotides targeting IQGAP1 were designed and synthesized by Dharmacon: siIQGAP1.a, 5′-GAACGUGGCUUAUGAGUACUU-3′ and 5′-GUACUCAUAAGCCACGUUCUU-3′ and siIQGAP1.b, 5′-CCUCUCGCUCUGAUGGGACAUUUGU-3′ and 5′-ACAAAUGUCCCAUCAGAGCGAGAGG-3′ targeting the 3′ untranslated region of endogenous IQGAP1. ERK1/2 and nontargeting control siRNAs were synthesized as previously described4. One million early passage neonatal keratinocytes were electroporated with 2 nM total siRNA using Amaxa nucleofection reagents according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The vectors for pGIPZ shRNA targeting IQGAP1 were designed and purchased through Open Biosystems, cat nos. V2LHS-86779 (shIQGAP1.a), V2LHS-86781 (shIQGAP1.b) and V2LHS-259635 (shIQGAP1.c).

Western blots

Cells were lysed after treatment as indicated in NP-40 buffer plus phosphatase and protease inhibitors (Roche). Immunoblots were performed as previously described3 with the following antibodies: rabbit antibody to ERK1/2 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling, 9102), rabbit antibody to pERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204; 1:1,000, Cell Signaling, 9101), rabbit antibody to ERK2 (1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 153), mouse antibody to IQGAP1 (1:400, Upstate, 05-504), rabbit antibody to IQGAP1 (1:500, Abcam, 86064), rabbit antibody to Myc (1:500, Abcam, 9106), rabbit antibody to PDGFR-β (1:1,000, Cell Signaling, 3169), rabbit antibody to IGF1-R (1:1,000, Cell Signaling, 3018) and mouse antibody to hemagglutinin (HA) (1:2,000, Covance, MMS-101P).

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

At the indicated time points, RNA was harvested from cells by treatment with TRIzol according to the standard Invitrogen protocol. Relative mRNA expression was determined by qRT-PCR analysis using a Stratagene Mx3000P thermocycler and Brilliant II SYBR Green qRT-PCR one-step master mix reagents. The primer concentration was 200 nM with 100 ng RNA. Samples were run in triplicate and normalized to the levels of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) or 18S mRNA for each reaction. The following primers were used for this study: IQGAP1: forward, 5′-TTCGCCACTACCCAGACCTTGTTT-3′ and reverse, 5′-CCTGTCTTGGATGTGGCCTTTGG-3′; IQGAP2: forward, 5′-TCTGTGCCACTTAGAGGAAGCCAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-CACTGGACGGTATTATCTGTGTGTCGAA-3′; IQGAP3: forward, 5′-AGGGCAAGGC AGCCCAGACT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCCGTTGGCACAGTCGGGAA-3′; Myc- tagged WW: forward, 5′-GATAATAACAGCAAGTGGGTG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGGTCTCCAGATTGTGGTAATAA-3′; Myc-tagged mutant WW: forward, 5′-TTCTGAAGAAGATCTGGATA-3′ and reverse, 5′-CCAGATTGTGGGCAG CATAA-3′; and COT: forward, 5′-CAAGTGAAGAGCCAGCAGTTT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCAAGCAAATCCTCCACAGTTC-3′ (previously described6)

Rescue

Primary human keratinocytes were infected with pLEX-ER: HRASGV12, and after puromycin selection, cells were treated with either empty virus control or pLEX-HA-IQGAP1. After site-directed mutagenesis to remove an internal BamH1 site in the host pCR-BluntII-TOPO Iqgap1 (Open Biosystems, cat. no. MHS4426-99626202) vector, full-length IQGAP1 was PCR amplified with 5′ BamH1 and 3′ Xho1 primers and cloned in frame into pLEX–N-terminal–HA–tagged vector. Seventy-two hours after infection, cells were nucleofected with siRNA targeting a control sequence or IQGAP1.b. Seventy-two hours after nucleofection, cells were harvested for western blot analysis. Samples were immunoblotted as described above.

Immunoprecipitation-kinase assay

Cell Signaling p44/42 MAP Kinase Assay Kit immunoprecipitation-kinase assays were used to evaluate perturbations to ERK1/2 MAPK biochemical signaling after ablation of ERK MAPK scaffolds according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, genetically modified cells were lysed under non-denaturing conditions at defined time points after treatment. Cell lysates were incubated overnight at 4 °C in the presence of immobilized monoclonal primary antibody to pERK1/2. Immunoprecipitated complexes were then mixed with an ELK-1 fusion protein and cold ATP. Samples were analyzed by gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting for mouse pELK-1 (Ser383; 1:1,000, Cell Signaling, 9186).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described3 with the following antibodies: rabbit antibody to pERK (Thr202/Tyr204; 1:25, Cell Signaling, 4370), rabbit antibody to ERK (1:100, Cell Signaling, 4695), mouse antibody to IQGAP1 (1:25, Invitrogen, 33-8900), rabbit antibody to Myc (1:100, Abcam, 9106) and rabbit antibody to cleaved caspase 3 (1:400, Cell Signaling, 9664). The skin cancer and normal tissue microarrays SK208 and SK2081 (Biomax) were scored blindly on the basis of IQGAP1 stain.

Coimmunoprecipitation

Cells were crosslinked with 1 ml of 20 mM dithiobis[succinimidyl propionate] (DSP) (Thermo Scientific) for 1 h at 4 °C, and the reaction was quenched with washes in 50 mM Tris. Cells were lysed in 20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% NP-40 and 10% glycerol, with 0.5 mM dTT and protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche) added directly before use (buffer 1) for 1 h at 4 °C but not pelleted. One milligram lysate in 500 μl was combined with 5 μg of mouse antibody to IQGAP1 (Millipore, 05-504) in buffer 1 and rocked overnight at 4 °C. Thirty microliters of protein G sepharose 4 fast flow (GE Healthcare) was washed in buffer 1 and combined with lysate for 1 h at 4 °C. Supernatant was removed to check for immunodepletion. Beads were washed three times in 20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl and 1% Triton X-100, with protease and phosphatase inhibitors added directly before use (buffer 2). Immunoprecipitate was eluted from beads in 4× LDS sample buffer in buffer 1 plus 5% Mercaptoethanol. Samples were immunoblotted as described above.

Cloning, mutagenesis and peptide production of the IQGAP1 WW domain

The pLEX-Myc WW clone was PCR amplified from pCR-BluntII-TOPO IQGAP1 (Open Biosystems, cat. no. MHS4426-99626202) using the following primers: forward, 5′-GCTCGCGGATCCACCATGGAACAAAAACTTATTTCTGAAGAAGATCTGGATAATAACAGCAAGTGGGTGAAGCAC-3′ and reverse, 5′-ATAAGTGCGGCCGCTTATGGGGGTTCATCCCATCCTCCTTCCTG-3′. PCR products were subsequently digested with BamH1 and Not1 restriction enzymes and ligated into the LentiORF pLEX-MCS vector (Open Biosystems, cat. no. OHS4735). To generate the pLEX mutant WW clone, QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) was used. The following primers were used to mutate Tyr696 and Tyr697 to alanine: forward, 5′-GGTGAAGCACTGGGTAAAAGGTGGATATTATGCTGCCCACAATCTGGAGACC-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGTCTCCAGATTGTGGGCAGCATAATATCCACCTTTTACCCAGTGCTTCACC-3′. Peptides corresponding to octo-arginine Myc-tagged scrambled control ((d-arginine)(d-arginine) (d-arginine)(d-arginine)(d-arginine)(d-arginine)(d-arginine)(d-arginine)) EQKLISEEDLSHGNQWDWKYLGNYKVTGNEVYEDKGYEPHWP), to octo-arginine Myc-tagged WW domain ((d-arginine)(d-arginine) (d-arginine)(d-arginine)(d-arginine)(d-arginine)(d-arginine)(d-arginine) EQKLISEEDLDNNSKWVKHWVKGGYYYYHNLETQEGGWDEPP)) and to octo-arginine Myc-tagged mutant WW domain ((d-arginine)(d-arginine) (d-arginine)(d-arginine)(d-arginine)(d-arginine)(d-arginine)(d-arginine)EQKLISEEDLDNNSKWVKHWVKGGYYAAHNLETQEGGWDEPP)) were synthesized by Biomatik, CSBio and Stanford Biomaterials and Advanced Drug Discovery laboratories in acetate salt and resuspended in water to a 2.5–5 mM working solution. Peptide was added directly into the medium of tissue culture or into osmotic pumps at the concentrations indicated.

Cell viability assay

Genetically modified adherent cancer cell lines were seeded in equivalent, low-density cultures in duplicate in 24-well plates. Twenty-four hours after seeding, the medium was removed and replaced with 500 μl of a 5:1 mixture of cell medium and cell titer blue reagent (Promega). Cultures were incubated with this mixture for 2 h at 37 °C in the dark. Fluorescence (560 nm/590 nm (emission/excitation)) for 100 μl in triplicates for each sample was recorded. Incubation with cell titer blue reagent and fluorescent readings were repeated every 2 d for a total of 12 d. Values plotted correspond to readings taken while control samples were still growing exponentially. For pancreatic cancer cell lines (Panc1, CFPac1 and AsPc1), WW or SCR peptide was added at a concentration of 20 μM. The MTT cell proliferation assay (Roche) was performed in triplicate according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For PLX-4032–resistant subclones (adapted from ref. 6), cultured cells were seeded into 96-well plates (250–3,000 cells per well). Twenty-four hours after seeding, serial dilutions of PLX-4032 were prepared in DMSO and added to cells, yielding final drug concentrations ranging from 0 to 50 μM PLX-4032, with the final volume of DMSO not exceeding 1%. Cells were treated daily and incubated for 72 h after the addition of drug. Data from growth-inhibition assays were modeled using a nonlinear regression curve fit with a sigmoid dose response. These curves were displayed, and half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were generated using Prism 5 (GraphPad). Sigmoid-response curves that crossed the 50% inhibition point at or above 20 μM have IC50 values designated as >20 μM.

Migration assay

Ibidi silicone culture inserts were used to evaluate migration without variable scratching and physical wounds to cells and used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were seeded at 25,000–50,000 cells per chamber and allowed to attach overnight. Twenty-four hours later, the culture inserts were removed, and the cells were treated with mitomycin C to inhibit proliferation. Cells were cultured under normal conditions, and images were acquired at the time points indicated until control samples had fully migrated into the opening. Light microscopy images were acquired (three per well and three replicates per sample). Images were analyzed using automated image analysis software (Ibidi, Wimasis), and migration was quantified relative to empty vector control.

Xenografts, in vivo treatments and measurements

One-million transduced cancer cells engineered were suspended in a volume of 200 μl containing 50% Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and injected with a 27-G needle into the subcutaneous space of hairless 6- to 8-week-old severe combined immuno-deficient (SCID) mice (SHO stock, Charles Rivers). For melanoma tumor growth experiments, cells were transduced with luciferase and empty vector or WW before injection. For intratumoral injection experiments, cells were transduced with luciferase, and xenografts were allowed to grow untreated for 3 weeks. Subsequently, tumors were measured and equally divided depending on size into two groups. Each group received five treatments of 200 μl lentiviral empty vector or WW intratumorally injected every 3 d over the course of 2 weeks. For osmotic pump experiments, cells were transduced with luciferase, and xenografts were allowed to grow untreated for 1–2 weeks. Subsequently, tumors were measured and equally divided depending on size into two to three groups. Osmotic pumps (Alzet) loaded with 20 mg ml–1 peptide were implanted into the subcutaneous space of the mice. In all conditions, tumors were observed at least twice per week and recorded by photography and caliper measurements of length, width and depth. Tumor volume was estimated using the formula 4/3π(r1r2r3), where r1 is the radius of length, r2 is the radius of width and r3 is the radius of height. Bioluminescence imaging was performed using an IVIS-200 imaging system (Xenogen Corporation). After anesthesia with 2.5% isofluorane, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 150 mg per kg body weight D-luciferin in PBS. Plateau phase–emitted light was captured with an open emission filter as the average radiance (photons per second per cm2 per steradian). For pancreatic cancer in vivo models, mice were treated with either the WW peptide (50 mg per kg body weight twice daily), a control scrambled peptide (50 mg per kg body weight twice daily) or 100 mg per kg body weight of gemcitabine (Sigma) dissolved in saline with scrambled peptide by intraperitoneal injection. Gemcitabine was used on a Q3D×4 schedule (every third day for four cycles) as previously described35.

Chemical and hematological parameters

Whole blood was obtained by cardiac puncture under isoflurane anesthesia before euthanasia and submitted for routine hematologic and biochemical analysis.

Derivation of PLX-4032–resistant tumors

Cells were made resistant to PLX-4032 as previously described5,6. Briefly, BRAFV600E cancer cell lines were grown in low doses of PLX-4032 (1 μM in DMSO; Active Biochem) for 6–8 weeks until the amounts of pERK were increased and cells were no longer sensitive to increased doses of PLX-4032 (5 μM). From these resistant stocks, cells were plated in limiting dilution in 96-well plates to isolate single cell colonies. These colonies were then assayed for resistance to PLX-4032, as well as recognized mechanisms of resistance, and used for subsequent proliferation assays after treatment with peptide as indicated.

DNA sequencing reactions

RNA was isolated from PLX-4032–sensitive parental and resistant subclones using TRIzol and converted to complementary DNA (cDNA). The cDNA was used as a template to amplify NRAS using NRAS forward (5′-CTGAGTACAAACTGGTGGTGGTT-3′) and reverse (5′-GGCTTGTTTTGTATCAACTGTCC-3′) primers, as well as the following protocol: a single step at 94 °C for 3 min and then 35 cycles of amplification (94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min). PCR products were gel purified and submitted for Sanger sequencing (5′-GTACAAACTGGTGGTGGTTGG-3′).

Statistics

Each data panel is representative of at least three independent replicate experiments or multiple independent mice, as indicated. The s.d. was used for all analyses. Further analysis of variance and subsequent post hoc comparisons used Student’s t tests. Kaplan-Meier survival data were reanalyzed using a log-rank test.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.L.J. conceived the study and developed crucial proof-of-concept studies.

K.L.J. also performed and designed all IQGAP1 knockout in vivo characterization, IQGAP1 RNAi tissue and cell studies, designed and constructed the WW lentivirus, performed WW peptide validation in cells, tissue and in vivo mouse models and did immunoprecipitation studies. K.L.J. contributed to PLX-4032–resistant experiments, clinical chemistry data analysis and pancreatic cancer studies. Additionally, K.L.J. coordinated all aspects of the project, interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. P.K.M. performed and designed the pancreatic cancer studies and edited the manuscript. A.M.Z. performed and designed PLX-4032–resistant experiments, contributed to cell studies, pancreatic cancer studies, bioinformatics analysis and clinical chemistry data analysis and edited the manuscript. J.Z. performed bioinformatics analysis and edited the manuscript. B.Z. performed IQGAP1 rescue experiments and contributed to immunoprecipitation studies. J.S. supervised the pancreatic cancer studies, interpreted data and helped write the manuscript. P.A.K. supervised the project, interpreted data and wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormick F. Cancer therapy based on oncogene addiction. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011;103:464–467. doi: 10.1002/jso.21749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scholl FA, et al. MEK1/2 MAPK kinases are essential for mammalian development, homeostasis, and Raf-induced hyperplasia. Dev. Cell. 2007;12:615–629. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dumesic PA, Scholl FA, Barragan DI, Khavari PA. ERK1/2 MAP kinases are required for epidermal G2/M progression. J. Cell Biol. 2009;185:409–422. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200804038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nazarian R, et al. Melanomas acquire resistance to B-RAFV600E inhibition by RTK or N-RAS upregulation. Nature. 2010;468:973–977. doi: 10.1038/nature09626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johannessen CM, et al. COT drives resistance to RAF inhibition through MAP kinase pathway reactivation. Nature. 2010;468:968–972. doi: 10.1038/nature09627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nikolaev SI, et al. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent somatic MAP2K1 and MAP2K2 mutations in melanoma. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:133–139. doi: 10.1038/ng.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagle N, et al. Dissecting therapeutic resistance to RAF inhibition in melanoma by tumor genomic profiling. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:3085–3096. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White CD, Brown MD, Sacks DB. IQGAPs in cancer: a family of scaffold proteins underlying tumorigenesis. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1817–1824. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson M, Sharma M, Henderson BR. IQGAP1 regulation and roles in cancer. Cell Signal. 2009;21:1471–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolch W. Coordinating ERK/MAPK signalling through scaffolds and inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:827–837. doi: 10.1038/nrm1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrell JE., Jr. What do scaffold proteins really do? Sci. STKE. 2000;2000:pe1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2000.52.pe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Good MC, Zalatan JG, Lim WA. Scaffold proteins: hubs for controlling the flow of cellular information. Science. 2011;332:680–686. doi: 10.1126/science.1198701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roy M, Li Z, Sacks DB. IQGAP1 binds ERK2 and modulates its activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:17329–17337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White CD, Erdemir HH, Sacks DB. IQGAP1 and its binding proteins control diverse biological functions. Cell Signal. 2012;24:826–834. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark EA, Golub TR, Lander ES, Hynes RO. Genomic analysis of metastasis reveals an essential role for RhoC. Nature. 2000;406:532–535. doi: 10.1038/35020106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jadeski L, Mataraza JM, Jeong HW, Li Z, Sacks DB. IQGAP1 stimulates proliferation and enhances tumorigenesis of human breast epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:1008–1017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Z, et al. IQGAP1 plays an important role in the invasiveness of thyroid cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010;16:6009–6018. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato A, et al. Association of RNase L with a RAS GTPase-activating-like protein IQGAP1 in mediating the apoptosis of a human cancer cell-line. FEBS J. 2010;277:4464–4473. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li S, Wang Q, Chakladar A, Bronson RT, Bernards A. Gastric hyperplasia in mice lacking the putative Cdc42 effector IQGAP1. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;20:697–701. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.697-701.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujiki H, et al. Codon 61 mutations in the c-Harvey-RAS gene in mouse skin tumors induced by 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene plus okadaic acid class tumor promoters. Mol. Carcinog. 1989;2:184–187. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940020403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarutani M, Cai T, Dajee M, Khavari PA. Inducible activation of RAS and Raf in adult epidermis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:319–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reuter JA, et al. Modeling inducible human tissue neoplasia identifies an extracellular matrix interaction network involved in cancer progression. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:477–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nabeshima K, Shimao Y, Inoue T, Koono M. Immunohistochemical analysis of IQGAP1 expression in human colorectal carcinomas: its overexpression in carcinomas and association with invasion fronts. Cancer Lett. 2002;176:101–109. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00742-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sugimoto N, et al. IQGAP1, a negative regulator of cell-cell adhesion, is upregulated by gene amplification at 15q26 in gastric cancer cell lines HSC39 and 40A. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;46:21–25. doi: 10.1007/s100380170119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hingorani SR, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:437–450. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins MA, et al. Oncogenic KRAS is required for both the initiation and maintenance of pancreatic cancer in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:639–653. doi: 10.1172/JCI59227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ridky TW, Chow JM, Wong DJ, Khavari PA. Invasive three-dimensional organotypic neoplasia from multiple normal human epithelia. Nat. Med. 2010;16:1450–1455. doi: 10.1038/nm.2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roy M, Li Z, Sacks DB. IQGAP1 is a scaffold for mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;25:7940–7952. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.7940-7952.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rothbard JB, et al. Conjugation of arginine oligomers to cyclosporin A facilitates topical delivery and inhibition of inflammation. Nat. Med. 2000;6:1253–1257. doi: 10.1038/81359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson EL, et al. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-RAS. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3243–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawaguchi Y, et al. The role of the transcriptional regulator Ptf1a in converting intestinal to pancreatic progenitors. Nat. Genet. 2002;32:128–134. doi: 10.1038/ng959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marino S, Vooijs M, van Der Gulden H, Jonkers J, Berns A. Induction of medulloblastomas in p53-null mutant mice by somatic inactivation of Rb in the external granular layer cells of the cerebellum. Genes Dev. 2000;14:994–1004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toftgard R, Roop DR, Yuspa SH. Proto-oncogene expression during two-stage carcinogenesis in mouse skin. Carcinogenesis. 1985;6:655–657. doi: 10.1093/carcin/6.4.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olive KP, et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science. 2009;324:1457–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.1171362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]