Abstract

The current study evaluated the efficacy of a single session brief motivational enhancement (BME) interview to increase treatment compliance and reduce recidivism rates in a sample of 82 recently adjudicated male perpetrators of intimate partner violence (IPV). Batterer intervention program attendance and completion as well as re-arrest records served as the primary outcome measures and were collected 6 months post adjudication. Results indicated that BME was associated with increases in session attendance and treatment compliance. BME was not directly associated with reductions in recidivism. The relationship between BME and treatment compliance was moderated by readiness to change such that BME participants with low readiness to change attended more sessions and were more likely to be in compliance with the terms of a treatment than control participants with low readiness while participants with high readiness attended sessions equally, regardless of study condition. Results indicate that outcomes may be improved through treatment efforts that consider individual differences, such as one’s readiness to change, in planning interventions for IPV perpetrators.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, Motivational Interviewing, readiness to change

Offenders adjudicated on misdemeanor intimate partner violence (IPV) charges are typically mandated to complete a probationary period and attend a batterer intervention program (BIP) (e.g., Babcock, Green, & Robie, 2004; Jackson et al., 2003). BIPs utilize psychoeducational material, cognitive change techniques, and skills training within various theoretical frameworks over the course of 12-52 weekly sessions to reduce violent recidivism (Babcock, Green, & Robie, 2004; Pence & Paymar, 1993; Sonkin, Martin, & Walker, 1985). BIP success is evaluated by session attendance and recidivism as indicators of the program’s ability to effectively modify behavior in order to prevent future acts of violence. Findings suggest that BIPs may not be effective at reducing or eliminating IPV and that multiple factors may contribute to the overall weak effects, including high attrition, failure to assess or acknowledge individual differences in treatment planning, and the usage of specific intervention techniques that may impede behavior change (for a review, see Eckhardt et al., in press). The current study investigated the effectiveness of a brief motivational enhancement intervention to influence treatment outcomes among a sample of male IPV offenders court-mandated to attend BIPs, and examined whether offender readiness to change moderated the effectiveness of the brief intervention.

Research has not generally been supportive of BIP effectiveness or of the offenders’ ability to comply with BIP requirements. In fact, prior reviews suggest that treatment effects on recidivism are generally small and non-significant. Feder and Wilson (2005) concluded that BIPs had no overall effect on subsequent IPV according to victim reports and a small effect according to official criminal reports (d = 0.1 and .26, respectively). Similarly, Babcock and colleagues (2004) reviewed 22 studies using police or partner reports of violence recidivism, and reported small effect sizes for BIP completion and IPV cessation, with d’s ranging from .09 to .34. In a recent review of all controlled studies of BIPs, Eckhardt et al. (in press) similarly concluded that there is as much evidence in favor of the effectiveness of BIPs as there is against, with most studies of BIP effectiveness suffering from substantial methodological limitations. Poor attendance and high attrition have been implicated as pervasive problems that may contribute to the ineffectiveness of BIPs, as only between 10% and 60% of men fully comply with treatment requirements and the majority of drop outs occur after a single session (Cadsky et al., 1996; Daly & Pelowski, 2000; Pirog-Good & Stets, 1986; Rosenfeld, 1992). This is concerning because perpetrators who drop out in the first three months demonstrate significantly higher rates of IPV reoffending relative to those who complete a BIP (Babcock & Steiner, 1999; Bennett et al., 2007; Gondolf, 2000).

Stuart and colleagues (2007) observed these BIP outcomes and speculated that low, purely external motivation among mandated offenders may contribute to treatment resistance and failure, which may then contribute to recidivism. The researchers suggested an examination of individual factors that may serve to internally motivate offenders to be more active and invested in their own treatment, with the ultimate goal of encouraging prosocial, non-violent behavior. One such factor that has received initial empirical support represents the degree to which a client is prepared to take the steps necessary for change, a concept referred to as “readiness to change” (Miller & Rollnick, 2002; Norcross, Krebs, & Prochaska, 2011), and has been described using five stages ranging from early, precontemplative stages to later action and maintenance stages (for a more detailed discussion, see Eckhardt, Babcock, & Homack, 2004; Murphy & Baxter, 1997). Norcross and colleagues (2011) recently conducted a meta-analysis of 39 studies to report a small-to-medium mean effect size between stages of change and psychotherapy outcomes, suggesting that advanced pretreatment readiness to change predicted therapeutic progress over the course of treatment.

Prochaska and colleagues (1992) offered a potential moderator of the relationship between readiness to change and therapeutic outcomes in reporting that successful change requires a fit between the specific techniques used to facilitate behavior change and the client’s motivation to make use of those techniques in their current stage of the change process. The most common BIP model is based upon the “Duluth” intervention approach, in which male perpetrators participate in a didactic group treatment designed to reduce coercive conflict tactics by confronting perpetrators’ misogynistic attitudes, identifying beliefs related to male power or control, and promoting egalitarian relationship behaviors (Pence & Paymar, 1993). The mandatory nature of BIPs, the abrasive style of many program facilitators, and individual factors ranging from intellectual capacity to long-held attitudes towards the use of violence may well reduce an IPV client’s readiness to change in treatment (Murphy & Meis, 2008; Musser, Semiatin, Taft, & Murphy, 2008; Scott & Wolfe, 2003). Murphy and Eckhardt (2005) provide a detailed formulation of motivation to, and ambivalence toward, change across the stages experienced by IPV perpetrators under the framework of motivational interviewing and enhancement.

Motivational interviewing (MI; Miller, 1983; Miller & Rollnick, 2002) is a versatile set of techniques that have been widely applied to, and empirically validated for, a host of mental health disorders and maladaptive behaviors (Burke et al., 2003; Miller & Rollnick, 2002). MI assumes that most individuals who engage in maladaptive behaviors are aware of associated disadvantages but feel a degree of ambivalence regarding the discontinuation of the behavior. In the context of IPV, ambivalence to change is often observed in the earlier stages of the change process and may result from the conflicting motivation to discontinue violent behavior while continuing to justify abuse or remaining uncertain about one’s ability to remain non-violent (Murphy & Eckhardt, 2005). Thus, ambivalence may reflect either uncertainty about the relative costs and benefits of reducing violent behavior or apathy towards the severity of an abusive event. The client’s decision to change is conceptualized as a tipping of the balance between perceived benefits and consequences to violence. The therapist’s objective is to help the client resolve ambivalence in a manner that promotes therapeutic change in a non-demanding, nonjudgmental manner. The confrontational style of many BIPs may provoke the client to justify and defend their aggressive behaviors, which stands in stark contrast to the spirit of MI that emphasizes therapeutic collaboration and client autonomy (Brehm & Brehm, 1981; Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Nevertheless, an emerging literature suggests a connection between the integration of MI techniques into existing IPV interventions and improved treatment outcomes.

Several studies have evaluated the effects of a brief motivational enhancement treatment (BME), a rapid form of MI delivered over a short period of time, on the behavior of IPV perpetrators. Taft and colleagues (2001) assigned 189 males engaged in a BIP to either a 12-week treatment as usual condition or a 10-week treatment retention group that was supplemented with motivational enhancement techniques. Males in the treatment retention condition evidenced greater attendance and program completion relative to males in the treatment as usual condition. Kistenmacher and Weiss (2008) examined the self-reports of 33 male IPV offenders and determined that those randomly assigned to a 2-session BME condition reported greater readiness to change and decreased attributions of blame for abuse relative to a non-BME control group. Among 108 randomly assigned IPV males, Musser and colleagues (2008) found that a 2-session BME regimen improved compliance with treatment expectations, group participation, outside help-seeking behavior, and marginally decreased violent recidivism over control procedures. Woodin and O’Leary (2010) reported that a 2-session BME treatment reduced physical aggression more significantly than a minimal feedback condition among a college sample of 50 dating couples (d = 0.56).

Initial evidence supports the effectiveness of BME to encourage compliance with treatment, promote cognitive change consistent with non-violent behavior, and contribute to reductions in IPV recidivism. MI techniques may be particularly advantageous in reducing IPV recidivism, as they are designed to facilitate client investment in and compliance with treatment through the non-abrasive diffusion of anger regarding mandated treatment, aid in establishing therapeutic rapport, provide therapists with a framework for rolling with resistance, and enhance the client’s expectation of benefiting from a BIP with the goal of facilitating change (Murphy & Eckhardt, 2005).

Previous research has examined the effects of at least two BME sessions on attendance and recidivism. High rates of failure to attend and attrition following the first BIP session highlight the importance of early motivational enhancement either during or prior to the first treatment session (e.g., Daly & Pelowski, 2000). The current study sought to investigate the value of a cost and time efficient single BME session that can be implemented before individual or group treatment involvement to increase a perpetrator’s compliance with a BIP and reduce recidivism among 82 adjudicated male IPV perpetrators prior to entry into a mandatory 26-week batterer intervention program. We hypothesized that: 1) Participants randomly assigned to receive a single-session pre-BIP motivational enhancement intervention would, relative to men assigned to a control condition, have higher rates of BIP treatment compliance as indexed by time to intake, session attendance, and active participation in treatment; 2) The same BME sample would, relative to control participants, show fewer incidents of post-adjudication criminal recidivism; and, 3) BIP attendance outcomes would be moderated by preprogram readiness to change, such that individuals low in readiness to change would attend more BIP sessions if they were randomly assigned to the MET condition relative to a control condition.

Method

Sample

Eighty-two adjudicated male IPV offenders were recruited from the Marion County, IN probation department, which includes the urban Indianapolis area.1 Eligible participants were males who: 1) were adjudicated on a domestic violence-related offense involving an intimate partner no more than 2 weeks prior to study recruitment; 2) were 18 years of age or older; and 3) consented to participate in the research study. Female offenders were both infrequently charged with IPV-related offenses and/or infrequently referred to BIP in this jurisdiction. As a result, it was not practical to include female IPV offenders for participation in this study. An additional 8 males were approached and refused to participate in the study, citing conflicting appointments or a lengthy wait time as reasons for nonparticipation.

Procedures

Recruitment

Over a 6-month period, eligible IPV perpetrators were recruited by male researchers immediately after the completion of mandated probation intake procedures. Study personnel introduced themselves as researchers from a local university (not probation) and provided a brief overview of the single-session study. Interested participants completed a written consent form that had been approved by the Purdue University Institutional Review Board, underwent random assignment to the treatment (BME) or control condition, and completed all measures as well as the assigned intervention in the probation office on the same day.

Initial assessment

All measures were presented to participants verbally. Assessment measures included sociodemographic variables (age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, etc.), relationship behaviors, and an assessment of readiness to change. When available and appropriate, shortened versions of assessment instruments were used to reduce session length.

Selected items from the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996) were used to assess physical IPV (6 items), injury (2 items), psychological IPV (4 items), and sexual coercion (2 items). The full CTS2 is the most widely used domestic violence assessment instrument and consists of 39 perpetration and 39 victimization items assessing the frequency and severity of IPV over the previous year. Participants are instructed provide item responses that range from “never” to “more than 20 times.” The CTS subscales have strong reliability (α = .79-.95) and the measure has demonstrated strong construct validity (Straus et al., 1996). The 14 perpetration items selected for the current study demonstrated high internal consistency (α = .81) and were inversely correlated with relationship satisfaction (r = −.24, p = .03).

The Dyadic Adjustment Scale – 4 (DAS-4; Sabourin, Valois, Lussier, 2005) is a valid and internally consistent (α = .81-.92), 4-item version of the widely-used 32-item measure of relationship satisfaction. The measure has also demonstrated comparable construct and superior predictive validity to the DAS-32 (Sabourin et al., 2005). Item responses are selected from a scale ranging from either “never” or “extremely unhappy” to “always “ or “extremely happy” and were aggregated into a single relationship adjustment score. The DAS-4 proved reliable in the current sample (α = .85) and correlated with baseline IPV as expected.

The Safe At Home Scale (SAH; Begun et al., 2003) is a 35-item measure of the Precontemplation, Contemplation, and Action stages of change with strong psychometric properties (α = .67 - .87; Eckhardt & Utschig, 2007). SAH items do not specifically refer to IPV perpetration but predict IPV-related outcomes, such as changes in self-efficacy resulting from reduced physical IPV (Begun et al., 2003). The readiness to change summary index from the SAH, which was calculated by subtracting Precontemplation subscale scores from the sum of the Contemplation and Action subscales, was assessed as a moderator of the effects of study condition on treatment compliance in the current study (α = .79).

Pre-Program Condition

Males were randomly assigned (via computer generated random number) to one of two different pre-BIP intervention conditions: a BME condition or a control condition. In the control condition, males received additional information about their specific terms of probation and completed an unrelated computer task designed to standardize the duration of sessions between the two conditions. Trained project researchers delivered each condition in 45-55 minutes. All participants were given the opportunity to ask any questions prior to the termination of the session. When this concluded, participants were compensated $20 and escorted out of the probation office.

The BME session was adapted from a treatment manual that illustrates the application of MI techniques to IPV perpetrators (Murphy & Eckhardt, 2005). An advanced clinical psychology graduate student conducted all BME interviews following the use of multiple methods to assimilate standard MI training procedures, including a review of relevant manuals (e.g., Murphy & Eckhardt, 2005; Rollnick & Heather, 1992), rehearsal of BME techniques through role-playing exercises, and continued discussion of each strategy over the course of two weeks (1-2 hours per weekday) with an MI scholar and experienced BME therapist. Finally, eight sessions (16.7%) were recorded, transcribed, and reviewed by an impartial reviewer for adherence to MI standards and techniques using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) Code system, version 3.1.1 (Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Miller, & Ernst, 2010). Randomly sampled segments of each tape concluded that the graduate counselor had achieved 92% adherence to MI standards. This exceeds the beginning proficiency level of 90% and is consistent with rates of adherence reported in similar MI studies (e.g., Musser, Semiatin, Taft, & Murphy, 2008).

The graduate student counselor implemented a BME interview following the administration of all assessment measures. In the absence of change talk during the initial assessment, BME sessions began with a brief description of the abusive event in the participant’s own words and open ended questions as well as reflections were used to elicit ambivalence and change talk. Otherwise, the sessions began with a review of the participant’s responses to 1-2 items from the SAH that evidenced acceptance of problems related to IPV or a desire to change aggressive behavior. The therapist affirmed the thoughts and feelings of the clients and strategically reflected verbal content in a manner consistent with MI. When clients demonstrated a willingness to change, the interview concluded with the completion of a standardized change plan worksheet detailing the manner in which the client foresaw change occurring.

Outcome Measures

All outcome data were collected exactly 6-months after each participant’s intervention session using electronic files created and maintained by the probation department.

BIP Compliance

Compliance was assessed with a set of four outcome variables. First, the amount of time that lapsed between the probationer’s date of initial BIP referral and attendance at a BIP intake session was assessed and rounded to the nearest week. Second, successful (versus unsuccessful) attendance of a BIP intake was dichotomously coded. Third, BIP attendance was assessed using the number of sessions attended within the 6-month follow-up period. Six participants were excluded from BIP session analyses as available data indicated only active involvement in or termination from treatment. Finally, overall treatment compliance was also dichotomously assessed. Due to procedural and individual delays, most participants were unable to complete all required programming within the 6-month time frame. However, the 6-month window provided ample opportunity to evaluate the degree to which offenders were actively involved and making progress towards completing the judicially mandated BIP, or whether they were unable to conform to this demand. Thus, we coded participants as either being; 1) in good standing with and actively involved in the process of completing the program (63.7%), or 2) officially terminated from treatment for attendance problems, failure to pay, probation violations, or incarceration (36.3%). Two participants had recently completed a BIP and were not mandated to attend additional treatment, and thus were not included in BIP compliance analyses.

Recidivism

Few BME or control participants were arrested for violating a no-contact order (2 and 4, respectively) or for domestic battery (1 and 4, respectively), thus negating any analysis of IPV-specific recidivism. BME sessions, however, broadly focused on improving relationship quality through lifestyle changes that included relationship behaviors and egalitarian beliefs, reinforcing statements of emotion control and non-violent reactions to conflict, promoting reductions in unstable behavior that may impact the individual and his relationship (e.g., criminal activity), and reinforcing the negative effects of substance use on close relationships. Therefore, a categorical recidivism variable was created and each participant was classified as: 1) an aggressive re-offender (9.9%; e.g. assault, robbery), 2) a non-aggressive re-offender (24.7%; e.g. probation violation, substance use), or 3) not a reoffender (65.4%). The number of probation violations (substance use, failure to report to appointments, and failure to pay court/treatment fees) was also recorded and examined to assess possible treatment effects.

Analytic Plan

Chi-square analyses were utilized to examine differences between treatment and control groups on dichotomous variables, including overall compliance, attendance at intake and 4 specific sessions throughout treatment, and reoffending status. The effect of study condition on lapse between referral and intake, number of sessions attended, and number of probation violations acquired were assessed with the Mann-Whitney U test.2 The readiness to change moderator was tested using a binary logistic regression model for BIP program compliance and hierarchical regression for session attendance.3 Self-reported IPV perpetration (CTS2), relationship satisfaction (DAS-4), and ethnicity were entered as covariates in all regression analyses.

Results

Random Assignment Validation

There were no significant differences between BME and control groups on participant age, ethnicity, relationship duration with the current partner, marital status, or pre-manipulation readiness to change scores (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic Data for Participants in the Treatment and Control Groups.

| Study Conditions |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n=34) | Treatment (n=48) | |||||||

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | df | p | d |

| Age | 33.9 | 12.0 | 34.0 | 11.8 | −0.01 | 80 | .99 | .01 |

| Relationship Length | 84.7 | 98.0 | 85.3 | 98.0 | −0.03 | 80 | .98 | .01 |

| Number of Children | 2.8 | 1.6 | 3.3 | 1.8 | −0.12 | 80 | .22 | .29 |

| Satisfaction | 16.8 | 4.7 | 17.1 | 5.0 | −0.30 | 80 | .77 | .06 |

| Readiness to Change | ||||||||

| Precontemplation | 28.9 | 5.1 | 28.5 | 4.7 | 0.43 | 80 | .67 | −.08 |

| Contemplation | 23.7 | 7.9 | 23.3 | 7.7 | 0.23 | 80 | .82 | −.05 |

| Preparedness | 13.8 | 3.9 | 14.5 | 3.7 | −0.89 | 80 | .38 | .19 |

| Maintenance | 14.0 | 5.3 | 14.6 | 4.7 | −0.56 | 80 | .58 | .12 |

| Partner Violence | ||||||||

| Physical | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.1 | −0.39 | 80 | .70 | .09 |

| Verbal | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1.04 | 80 | .30 | −.20 |

| Psychological | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.44 | 80 | .66 | −.09 |

| Sexual | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | −1.68 | 80 | .10 | .21 |

| Frequency Data | Control | Treatment | χ 2 | df | p | d | ||

|

| ||||||||

| % Married | 41.2 | 25.0 | 2.40 | 1 | .12 | −.41 | ||

| % Caucasian* | 58.8 | 37.5 | 3.38 | 1 | .07 | −.48 | ||

| % African American | 41.2 | 60.4 | ||||||

Note: SD = Standard Deviation;

One treatment participant reported “other” minority status.

BIP Compliance

The percentage of BIP-compliant participants differed by study condition, χ2 (1, N = 80) = 4.4, p = .04, d = 0.47 (see Table 2). A greater percentage of BME condition participants (72.9%) had either successfully completed their BIP or remained in good standing 6-months post-adjudication, relative to control participants (50.0%). A larger percentage of BME participants (97.9%) attended the first intake session compared to those in the control condition (83.9%). BME participants, relative to controls, were more likely to attend an intake session (OR = 8.5; χ2(1, N = 79) = 5.30, p = .03, d = 0.50)4 and their 6th BIP session (OR = 2.9; χ2(1, N = 74) = 4.78, p = .03, d = 0.52). BME participants did not significantly differ from control participants on attendance at session 13 (OR = 2.4; χ2(1, N = 74) = 1.33, p = .25, d = 0.27), session 20 (OR = 1.7; χ2(1, N = 74) = .54, p = .46, d = 0.17), or session 26 (OR = 1.2; χ2(1, N = 74) = .04, p = .84, d < 0.01). BME participants attended their initial intake session significantly sooner (M = 3.19 weeks, SD = 0.34 weeks) than control participants (M = 5.88 weeks, SD = 0.95 weeks), U = 357.5, z = 2.44, p = .02 (d = −4.05). BME participants also attended more sessions (M = 12.2, SD = 1.5) than control participants (M = 8.3, SD = 1.8), U = 499.5, z = 1.71, p = .09, (d = 2.39). Hypothesis 1 was therefore partially confirmed: IPV offenders assigned to pre-BIP BME showed greater compliance with court-mandated BIP relative to control participants.

TABLE 2.

Outcome Data for Participants in the Treatment and Control Groups.

| Study Condition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Treatment | ||||||

| Variable | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | z | p | d |

| Intake lapse | 5.88 (0.95) | 24 | 3.19 (0.34) | 46 | 2.44 | .02 | −4.05 |

| Sessions Attended | 8.34 (9.89) | 29 | 12.24 (10.18) | 45 | 1.71 | .09 | 2.39 |

| Probation Violations | 3.24 (0.76) | 34 | 3.13 (0.56) | 48 | 0.37 | .71 | −0.14 |

| % | n | % | n | χ 2 | df | p | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| BIP Compliant | 50.0 | 32 | 72.9 | 48 | 4.36 | 1 | .04 | 0.47 |

| Intake | 83.9 | 31 | 97.9 | 48 | 5.30 | 1 | .03 | 0.50 |

| Session 6 | 48.3 | 29 | 73.3 | 45 | 4.78 | 1 | .03 | 0.52 |

| Session 13 | 31.0 | 29 | 44.4 | 45 | 1.33 | 1 | .25 | 0.27 |

| Session 20 | 17.2 | 29 | 24.4 | 45 | 0.54 | 1 | .46 | 0.17 |

| Session 26 | 13.8 | 29 | 15.6 | 45 | 0.04 | 1 | .84 | <0.01 |

| Recidivated | 39.4 | 33 | 25.0 | 48 | 1.90 | 1 | .17 | −0.31 |

Recidivism

There were no significant differences in recidivism between intervention conditions on aggressive, non-aggressive, and non-recidivism outcomes (χ2(2, N = 81) = 2.24, p = .33, d = 0.22). Arrest data were subsequently collapsed to form two categories: reoffenders and nonreoffenders (χ2(1, N = 81) = 1.90, p = .17, d = 0.31). Treatment (M = 3.13, SD = 0.56) and control (M = 3.24, SD = 0.76) participants received an equivalent number of violations, U = 779.5, z = .37, p = .71 (d = −0.14). Reoffenders (M = 3.00, SD = 4.91) attended significantly fewer BIP sessions than non-reoffenders (M = 14.91, SD = 9.76), U = 195.0, z = 5.04, p < .01, d = −1.63, suggesting that either non-compliance resulted in arrest, or that arrest precluded session attendance. Therefore, hypothesis 2 was not supported.

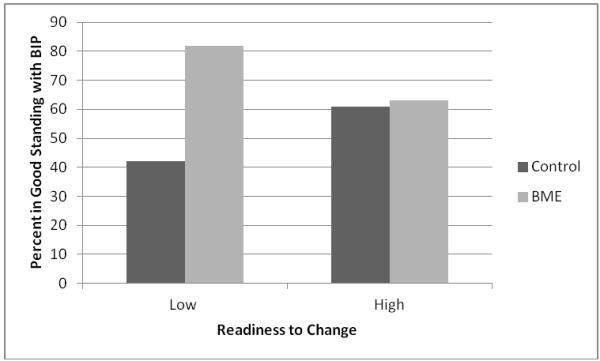

Readiness to Change

The final overall logistic regression model predicting BIP compliance/failure from treatment condition, readiness to change, and the interaction between condition and readiness, with baseline IPV perpetration, relationship satisfaction, and ethnicity serving as covariates, was significant, χ2(3) = 7.63, p = .05. Thus, the model accurately distinguished between those who had completed or were in good standing with their BIP from those who were noncompliant 67.5% of the time. Condition significantly discriminated between the two groups (z = 6.7, p = .01), and the interaction between treatment condition and readiness to change approached significance (z = 3.1, p = .08). Analysis of this trend in the data revealed that BME (82.6%), relative to control (41.2%), participants low in readiness to change were more likely to be compliant with treatment, χ2(1, N = 40) = 7.38, p = .01, d = 0.95. Males high in readiness to change were equally likely to be compliant with treatment regardless of BME (64.0%) or control (60.0%) condition, χ2(1, N = 40) = 0.06, p = .80, d = 0.09 (See Figure 1). However, these effects should be interpreted with caution due to the marginal significance of the interaction term. Readiness to change alone was not predictive of BIP compliance (z = 1.1, p = .29).

Figure 1.

Readiness to Change and Study Condition as Predictors of BIP Compliance

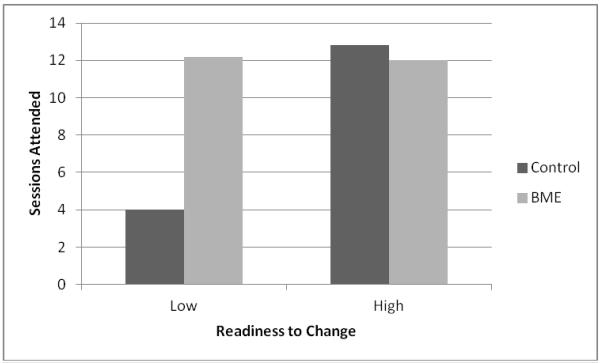

In the hierarchical regression analysis, number of sessions attended was regressed onto covariates (baseline IPV perpetration, relationship satisfaction, and ethnicity) in step 1, study treatment condition and readiness to change in step 2, and their interaction in step 3. Readiness to change predicted the number of sessions attended, β = 9.97, t(73) = 2.75, p < .01, and explained a non-significant portion of variance in session attendance, R2 = .04, F(1, 73) = 2.71, p = .10. Intervention condition, β = 8.58, t(73) = 2.69, p < .01, explained a marginally significant portion of the variance, R2 = .07, F(2, 73) = 2.57, p = .08. The condition-readiness interaction predicted session attendance, β = −10.38, t(73) = −2.24, p = .03, and explained significant variance, R2 = .13, F(3, 73) = 3.49, p = .02. BME participants low in readiness attended more sessions (M = 12.45, SD = 9.53) than control participants low in readiness (M = 3.88, SD = 6.56), U = 76.00, z = 2.97, p < .01 (d = 1.01). Among those high in readiness to change, attendance among BME (M = 12.04, SD = 10.97) and control (M = 13.84, SD = 10.72) participants was comparable, U = 132.50, z = −0.56, p = .58 (d = −0.17) (see Figure 2). Hypothesis 3 was therefore confirmed: pre-BIP BME has its greatest effects on individuals low in readiness to change.

Figure 2.

Readiness to Change and Study Condition as Predictors of Session Attendance

Discussion

The current investigation evaluated the utility of BME as a method to augment the generally weak effects of BIPs on two important outcomes: 1) program attendance and compliance, and 2) criminal recidivism. Overall, participants who received BME were significantly more likely to be in compliance with court-mandated BIP requirements, and more likely to attend intake and initial sessions than those assigned to the control group. There were no significant differences in general criminal recidivism rates between participants who did and did not receive a BME session. Finally, BME had its greatest effects on those commencing BIP with reported ambivalence about, or disinterest in, changing their behavior.

BIP Compliance

The current results indicated that men who received a single BME session had more successful BIP compliance. Control participants took nearly twice as long to begin treatment than BME participants. Relative to control participants, those in the BME condition attended more treatment sessions. Further analysis revealed that differences between treatment conditions were the most pronounced early in treatment, with BME participants more likely to attend the initial 6 BIP sessions and to consistently, but not significantly, exhibit higher rates of attendance throughout the remaining 20 sessions relative to control participants. These findings suggest that BME may exert its greatest effects early in treatment and that these effects may begin to dissipate over time and because of prolonged involvement in the MI-inconsistent methods utilized in standard treatment. In general, BME participants were more likely than control participants to be in compliance with BIP requirements over the 6-month follow-up period.

Though BME’s specific mechanisms of change are not fully understood, it is possible that motivational enhancement effects the manner in which offenders perceive the information presented in treatment, minimizing the perceived confrontational style of counselors and promoting a collaborative therapeutic alliance (Stuart, Temple, & Moore, 2007). Evidence suggests that a single session of MI may be sufficient to partially resolve a client’s ambivalence towards harmful behaviors and increase the likelihood of complying with treatment as a means to achieve self-change goals (Miller & Rollnick, 2002; Musser et al., 2008). However, the present data would suggest that this effect is likely to decay following BIP commencement, possibly underscoring the conflicting principles of MI and the less collaborative methods present in most BIPs. That is, MI is a non-judgmental set of therapeutic techniques that aim to help the client reduce ambivalence toward change by promoting the desire and capacity for self-enhancement; BIPs are, by their nature, a more coercive approach that carries the weight of the criminal justice system and legal mandates to effect change (Murphy & Eckhardt, 2005).

Previous studies have described the benefits of using MI with a partner violent sample, including increased group attendance, BIP completion, increased readiness to change, decreased attributions of blame, greater homework compliance, and greater group participation (Kristenmacher & Weiss, 2008; Musser et al., 2008; Taft et al., 2001). The current study is unique in that a clinical sample received the briefest MI treatment supplement to date and still evidenced positive therapeutic outcomes relative to a control sample. The clinical implications of the current study indicate that adding even a single BME session, or integrating MI techniques into the early stages of BIP intervention, may serve to improve initial treatment retention with minimal effort and training on the part of the BIP counselor or probation personnel.

Results further suggest that clinical interventions may be better informed by identifying readiness to change as a potential moderator of how IPV probationers respond to the initial stages of treatment, both in terms of their involvement in BIP as well as their likelihood of conforming with probationary guidelines. BME participants low in readiness to change prior to the BME session were more likely to comply with treatment and attend a greater number of sessions compared to those in the control group with low readiness to change. Perhaps not surprisingly, participants with high levels of readiness to change were compliant with BIP at the 6-month follow-up regardless of study condition. These participants, by definition, had entered the active stages of change prior to involvement in the study and had likely already committed to and/or commenced with satisfying legal mandates and treatment needs. Thus, for participants high in readiness to change, BME would likely only serve to reinforce the process they had already begun. BME may be ideally suited, however, to motivate participants low in readiness to change to view treatment as a resource in reaching personalized goals, or at the very least, as a requirement in accordance with the broader judicial mandate.

Given the observed interaction, it is not surprising that participants’ pre-intervention readiness to change had no unique effect on BIP compliance, which is consistent with Eckhardt and colleagues’ (2008) finding that stage of change clusters were not uniquely predictive of BIP completion variables at follow-up. All conceptualizations of readiness to change clusters support a distinction between early and late-stage clients (Murphy & Eckhardt, 2005). Early stage clients possess a victim-mind set and often appear uncooperative (Prochaska et al., 1992). Later-stage clients are in the process of actively seeking change and are more likely to comply with and explore treatment options. With a positive correlation between readiness to change and BIP attendance (Eckhardt, Babcock, & Homack, 2004), the current results further support MI as an intervention that may improve treatment outcomes through enabling the progression of hostile and resistant clients to later stages of change. Further research into the interaction between readiness to change and motivational enhancement is strongly encouraged.

Recidivism

Despite the effects of BME on treatment compliance that resulted in a more complete “dose” of treatment, there were no observed differences between groups on general recidivism variables. The only other IPV BME investigation to examine recidivism outcomes also reported non-significant results (Musser et al., 2008). These findings may speak to the challenges of reducing something as intractable as aggressive behavior in a single session, especially when considering the generally poor evidence regarding the effects of much longer treatment programs (BIP) on IPV reduction (see Babcock et al., 2004; Feder & Wilson, 2005). In addition, IPV reoffending had a low base rate of occurrence; in the current sample of criminally convicted IPV perpetrators, fewer than 5% were arrested for a new IPV offense within 6 months. Thus, while we conclude that BME may not reduce general recidivism, it is worth noting that it was not possible to conclude that BME was ineffective at reducing IPV because of the infrequency of IPV in both treatment and control groups during the follow-up period. The effects of BME and subsequent BIP sessions on general as well as IPV-specific recidivism may require a larger sample, a longer follow-up period, and/or methods of data collection that include intimate partner reports of IPV.

Limitations and future directions

First, external validity was restricted by an all-male sample. Second, intake sessions were conducted within the probation department. Participants may have associated researchers with probation personnel and edited their responses accordingly, despite preventative measures taken by the research team to avoid such associations. Third, collateral reports of violence from relationship partners were not solicited and the follow-up period was limited to 6-months due to time, budgetary, legal, and ethical concerns. Finally, in an effort to limit the burden placed upon participants and probation personnel, several assessment measures that would have allowed for additional moderator analyses and an examination of immediate shifts in readiness to change scores were omitted from the 1-hour intervention session. Future studies should 1) integrate female offenders, 2) evaluate whether the location influences observed BME effects, 3) include various sources for compliance and recidivism outcomes (e.g., Musser et al., 2008), 4) extend the follow-up period to account for inevitable criminal justice system delays and to allow time for the occurrence of IPV-specific recidivism, 5) assess changes in readiness following MI sessions, and 6) consider whether moderating factors other than those assessed in the current research, such as the severity and type of violence perpetration (e.g., intimate terrorism or common couple violence) may influence the association between BME and treatment. Additionally, we recommend that future studies include a second MI booster session midway through the treatment program given our findings that rates of compliance between BME and control participants became more similar as a function of time since adjudication. Thus, a timely booster may represent a minimal effort approach to reinforce the belief that treatment will help facilitate a desired behavior change (Taft et al., 2001).

Concluding Remarks and Clinical Implications

The current study indicates that exposure to a single-session BME as a supplement to a standard BIP serves to improve compliance with treatment and to perhaps put IPV offenders on “the path” to full compliance. However, there was little evidence that the single BME session significantly reduced rates of general criminal recidivism as measured by probation violations and arrest data. Results strongly indicate that treatment outcomes may be improved through efforts that consider individual differences, such as one’s stage in the change process, in planning interventions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant from the Clifford B. Kinley Trust, Purdue University. We would like to thank Matthew Miller and the personnel of the Marion County Probation Department, including Robert Bingham, Rick Britton, Christine Kerl, and Leonard Simpson.

Footnotes

Given that MI-based interventions demonstrate a moderate effect size of d = .50 across a variety of health-related behaviors (Burke et al., 2003), and with alpha = .05, power of .75 may be obtained with a sample size of N = 80 (Cohen & Cohen, 1983).

The treatment (Shapiro-Wilk W(46) = .87, p < .001) and control (Shapiro-Wilk W(24) = .87, p < .01) samples failed to demonstrate normally distributed lapse between BIP referral and intake session. The sample of treatment (Shapiro-Wilk W(45) = .93, p < .01) and control (Shapiro-Wilk W(29) = .80, p < .001) participants did not have normally distributed patterns of session attendance, nor did the treatment (Shapiro-Wilk W(48) = .80, p < .001) and control (Shapiro-Wilk W(34) = .76, p < .001) groups demonstrate a normal distribution of probation violations. The distributions were visually confirmed by deviations from expected values in Q-Q plots, a highly skewed histogram for the complete sample on lapse (skewness of 1.78, SD = .29), a moderately skewed histogram for sessions attended (skewness of 0.68, SD = 0.28), and a highly skewed histogram for probation violations (skewness of 1.16, SD = .27).

Each participant received a composite readiness to change index (RCI) score based upon their responses to the SAH. This composite score was calculated by summing the participants’ ratings on the scales depicting later stages of change (contemplation, preparation, and maintenance) and then subtracting the precontemplation score (Begun et al., 2003). The composite score was then dichotomized into high and low readiness to change to reflect clients in early and late stages, the most universally recognized distinction in readiness to change clusters (Murphy & Eckhardt, 2005).

A single participant in the treatment condition failed to attend an intake session, resulting in one cell of the 2×2 table with a value below 5. Fisher’s exact test was used in this case to obtain a p-value that accounts for the small cell.

Contributor Information

Cory A. Crane, Department of Psychological Sciences, Purdue University; Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York.

Christopher I. Eckhardt, Department of Psychological Sciences, Purdue University

REFERENCES

- Babcock J, Green C, Robie C. Does batterers’ treatment work? A meta-analytic review of domestic violence treatment. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;23:1023–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2002.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock J, Steiner R. The relationship between treatment, incarceration, and recidivism of battering: A program evaluation of Seattle’s coordinated community response to domestic violence. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Begun A, Murphy C, Bolt D, Weinstein B, Strodthoff T, Short L, Shelley G. Characteristics of the Safe at Home instrument for assessing readiness to change intimate partner violence. Research on Social Work Practice. 2003;13:80–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett L, Stoops C, Call C, Flett H. Program completion and rearrest in a batterer intervention system. Research on Social Work Practice. 2007;17:42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Burke B, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. JCCP. 2003;71:843–861. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadsky O, Hanson R, Crawford M, Lalonde C. Attrition from a male batterer treatment program: Client-treatment congruence and lifestyle instability. Violence and Victims. 1996;11:51–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Daly J, Pelowski S. Predictors of dropout among men who batter: A review of studies with implications for research and practice. Violence and Victims. 2000;17:137–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt C, Babcock J, Homack S. Partner assaultive men and the stages and processes of change. Journal of Family Violence. 2004;19:81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt C, Holtzworth-Munroe A, Norlander B, Sibley A, Cahill M. Readiness to change, partner violence subtypes, and treatment outcomes among men in treatment for partner assault. Violence and Victims. 2008;23:446–475. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.4.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt CI, Murphy C, Whitaker D, Sprunger J, Dykstra R, Woodard K. The effectiveness of intervention programs for perpetrators and victims of intimate partner violence: Findings from the Partner Abuse State of Knowledge Project. Partner Abuse. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt C, Utschig A. Assessing readiness to change among perpetrators of intimate partner violence: Analysis of two self-report measures. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Feder L, Wilson D. A meta-analytic review of court-mandated batterer intervention programs: Can courts affect abusers’ behavior? Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2005;1:239–262. [Google Scholar]

- Gondolf E. A 30-month follow-up of court-referred batterers in four cities. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2000;44:111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Monroe A, Stuart G. Typologies of male batterers: Three subtypes and the differences among them. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:476–497. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson S, Feder L, Forde D, Davis R, Maxwell C, Taylor B. Batterer intervention programs. National Institute of Justice; Washington DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kistenmacher B, Weiss R. Motivational interviewing as a mechanism for change in men who batter: A randomized controlled trial. Violence and Victims. 2008;5:558–570. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.5.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behavioral Psychotherapy. 1983;11:147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Miller W, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. 2nd ed Guilford; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers T, Martin T, Manuel J, Miller W, Ernst D. The Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Code: Version 3.1.1. 2010 Available on the World Wide Web at: http://casaa.unm.edu/codinginst.html.

- Murphy C, Eckhardt C. Treating the Abusive Partner: An individualized, cognitive-behavioral approach. Guilford; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C, Meis L. Individual treatment of intimate partner violence perpetrators. Violence and Victims. 2008;23:173–186. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musser P, Semiatin J, Taft C, Murphy C. Motivational interviewing as a pre-group intervention for partner violent men. Violence and Victims. 2008;23:539–557. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.5.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcross J, Krebs P, Prochaska J. Stages of change. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2011;67:1–12. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence E, Paymar M. Education groups for men who batter: The Duluth model. Springer; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pirog-Good J, Stets J. Programs for abusers: Who drops out and what can be done. Response to the Victimization of Women & Children. 1986;9:17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska J, DiClemente C, Norcross J. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld B. Court-ordered treatment for spouse abuse. Clinical Psychology Review. 1992;12:205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Sabourin S, Valois P, Lussier Y. Development and validation of a brief version of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale with a nonparametric item analysis model. Psychological Assessment. 2005;17:15–27. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott K, Wolfe D. Readiness to change as a predictor of outcome in batterer treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:879–889. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonkin D, Martin D, Walker L. The male batterer: A treatment approach. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Straus M, Hamby S, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman D. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS-2) Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G, Temple J, Moore T. Improving batterer intervention programs through theory-based research. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298:560–562. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft C, Murphy C, Elliott J, Morrel T. Attendance enhancing procedures in group counseling for domestic violence abusers. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2001;48:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Woodin E, O’Leary D. A brief motivational intervention for physically aggressive dating couples. Prevention Science. 2010;11:371–383. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]