Abstract

Background

Human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are being employed in clinical trials, but the best protocol to prepare the cells for administration to patients remains unclear. We previously demonstrated that MSCs could be pre-activated to express therapeutic factors by culturing the cells in 3D. Here we compared the activation of MSCs in 3D in fetal bovine serum (FBS) containing medium and in multiple xeno-free media formulations.

Methods

MSC aggregation and sphere formation was studied using hanging drop cultures with medium containing FBS or with various commercially available stem cell media with or without human serum albumin (HSA). Activation of MSCs was studied with gene expression and protein secretion measurements and with functional studies using macrophages and cancer cells.

Results

MSCs did not condense into tight spheroids and express a full complement of therapeutic genes in MEMα or several commercial stem-cell media. However, we identified a chemically-defined xeno-free media that when supplemented with HSA from blood or recombinant HSA, resulted in compact spheres with high cell viability, together with high expression of anti-inflammatory (PGE2, TSG-6) and anti-cancer molecules (TRAIL, IL-24). Furthermore, spheres cultured in this medium showed potent anti-inflammatory effects in an LPS-stimulated macrophage system, and suppressed the growth of prostate cancer cells by promoting cell-cycle arrest and cell death.

Discussion

We demonstrated that cell activation in 3D depends critically on the culture medium. The conditions developed here for 3D culture of MSCs should be useful in further research on MSCs and their potential therapeutic applications.

Keywords: MSC, sphere, xeno-free, pre-activation, 3D, stem cell

INTRODUCTION

Mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells (MSCs) are being employed in clinical trials for a large number of diseases. Currently, there are over 100 registered clinical trials (www.clinicaltrials.gov) with MSCs or related cells. Also, over half a dozen biotech companies are in Phase II and III trials in efforts to commercialize the cells [1]. The results from some of the trials are encouraging but few have provided universally accepted data on efficacy [2]. One of the hurdles encountered have been questions as to how to best prepare the cells for administration to patients: Should the cells be extensively expanded in confluent cultures, or expanded at low densities to a limited number of passages and population doublings so that the cells retain most of their stem cell like characteristics? [3] Should fetal bovine serum (FBS) be removed from medium formulations and replaced with chemically-defined factors? [4] Should the cells be administered from freshly thawed frozen vials or as cells directly isolated from tissue culture? [5] Should the cells be preconditioned in culture to activate therapeutic genes before administration? [6–9]

MSCs are traditionally isolated and expanded as adherent monolayers on tissue culture plastic that is commonly used to culture mammalian cells and that has been treated with proprietary protocols to increase the oxygen content of the surfaces and thereby increase cell adherence and spreading [10,11]. There has been increasing interest however in culturing cells in non-adherent conditions in which most cells remain viable and form spheres/spheroids. One of the advantages of culturing cells in 3D as spheres is that it more closely reproduces the in vivo environment including the delicate cell-to-cell and cell-to-matrix signaling networks [12,13]. A number of investigators have demonstrated that MSCs will form spheroids if incubated in hanging drops or other conditions that prevent their adhesion to planar surfaces [14–31]. Assembly into spheres improved many properties of the cells linked to their therapeutic potentials such as differentiating into hepatocyte-like cells [14], supporting migration and survival of endothelial cells [16], enhancing cardiac function [15,17], differentiating into insulin producing cells [19], differentiating into chondrocytes [31], enhancing cartilage repair [25], supporting expansion of hematopoietic cells [26], anti-cancer effects [20], and suppressing inflammation [27,29,30]. However the properties of the spheroid MSCs vary with the culture conditions such as cell concentration, and the time in culture [30]. We previously demonstrated that if prepared with FBS containing medium that was optimized for expansion of MSCs in monolayers, spheroid MSCs significantly decreased in size (to about ¼ of the volume of adherent MSCs) and fewer cells were entrapped in the lungs of mice after IV injection of the cells when compared to standard preparations of the cells [30]. Also, MSCs in spheroids significantly increased their production of PGE2, a potent inflammatory mediator; TSG-6, a protein that modulates the inflammatory responses; and STC-1, a calcium/phosphate regulating protein that reduces reactive oxygen species when compared to adherent MSCs [27,29,30,32,33]. As the cells assembled into spheroids, there was increased activation of caspases that drove the activation of IL-1 signaling which, in turn, drove secretion of TSG-6 and STC-1 [27]. The activation of both IL-1 and contact-dependent Notch signaling was required for secretion of PGE2 [27]. Moreover, the cells were more effective in suppressing inflammation in a zymosan-induced model for peritonitis [30] and in promoting transition of LPS-stimulated macrophages from a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to an anti-inflammatory M2 phenoptype [29].

Since the culture medium components are important in determining the properties of MSCs and since the use of animal components in the medium to prepare cells results in lot-to-lot variations and limits the therapeutic uses of the cells, we tested a series of different media for culture of MSCs in hanging drops. In the process we identified a chemically defined xeno-free medium that optimized sphere formation and pre-activation of MSCs to express and secrete several therapeutic molecules. Therefore the procedure employed here offers novel and effective methods for preparing pre-activated MSCs for research and clinical trials.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

MSC culture

Human MSCs, isolated from three adult bone marrow aspirates and cultured as previously described [30], were obtained from the Center for the Preparation and Distribution of Adult Stem Cells (http://medicine.tamhsc.edu/irm/msc-distribution.html). Briefly, 1–4 ml of bone marrow aspirate was obtained from the iliac crest of normal adult donors. Nucleated cells, obtained by density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque; GE Healthcare), were resuspended in complete culture medium (CCM) consisting of α-Minimum Essential Medium (MEMα, Gibco) supplemented with 17% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals), 100 units/ml penicillin (Gibco), 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Gibco), and 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco), seeded in 175 cm2 flasks (Nunc), and subsequently culture at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. After 24 h, non-adherent cells were discarded. Adherent cells were incubated 4–11 days until approximately 70% confluent, harvested with 0.25% trypsin and 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, Gibco) for 5 min at 37°C, and re-plated at 50 cells/cm2 in an intercommunicating system of culture flasks (Nunc). The cells were incubated for 7–12 days until approximately 70% confluent, harvested with trypsin/EDTA, and frozen as passage 1 cells in MEMα containing 30% FBS and 5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma). Frozen vials of each donor-derived passage 1 MSCs were thawed, suspended in CCM. and plated on a 152 cm2 culture dish (Corning). After 24 h, cells were harvested using trypsin/EDTA. The cells were plated at 100 cells/cm2, and expanded for 7 days before freezing as passage 2 cells. For the experiments described here, a vial of passage 2 MSCs were recovered by plating in CCM on a 152 cm2 culture dish for a 24 h period, re-seeded at 100–150 cells/cm2 and incubated for 6–8 days in CCM. Culture medium was changed every 2–4 days and 1 day before harvest. Characteristics of the MSCs used in the study are described in Supplemental Table 1.

Generation of spheroids and sphere-derived cells

To generate spheroids [30], MSCs were plated in hanging drops on an inverted culture dish lid in 35 µl of culture medium at 25,000 cells/drop. The lid was then rapidly re-inverted onto the culture dish that contained PBS to prevent evaporation of the drops. The hanging drop cultures were incubated for 3 days at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The MSCs in hanging drops were cultured in various media including CCM, αMEM, MesenCult XF (Stem Cell Technologies), MSCGM (Lonza), and StemPro XF (Life Technologies). In some experiments, the media were supplemented with either research grade or clinical grade HSA (1×, 4.3 mg/ml; 3×, 13 mg/ml; 6×, 26 mg/ml; 9×, 39 mg/ml) isolated from human blood (Gemini, Baxter) or recombinant HSA expressed in rice or yeast (Sigma). To obtain sphere-derived cells, spheroids were collected from the tissue culture dish lid using a cell lifter (Corning), washed in PBS, then incubated with trypsin/EDTA at 37°C for approximately 10 min with pipetting every 2–3 min. Spheroid-derived cells were collected by centrifugation at 453×g for 10 min.

Conditioned medium and cell lysate harvest

Spheroids and conditioned medium were collected from the tissue culture dish lid using a cell lifter and centrifuged at 453×g for 5 min. The supernatant was clarified by centrifugation at 10,000×g for 10 min and stored at −80°C. To obtain sphere cell lysates, spheres were centrifuged at 453×g for 5 min, washed with PBS, centrifuged at 453×g for 5 min, and lysed with RLT buffer from RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). In some experiments, intact spheres from 3 day hanging drop cultures were transferred to 6-well low adherent dishes (Costar) for 6 h in MEMα supplemented with 2% FBS, Pen-Strep, and L-glutamine.

Viability Assays

Cell viability was measured by flow cytometry (FC500, Beckman Coulter) using Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit (Sigma). Approximately 100,000 cells were incubated for 10 min with 0.5 µg/ml annexin V-FITC and 2 µg/ml propidium iodide (PI) in 300 µl of 1× binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, 0.14 M NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2). The cells were immediately placed on ice and analyzed. Cell fragments were removed by morphological gating. Cells negative for annexin V-FITC and PI were considered viable, annexin V-FITC positive and PI negative considered apoptotic, and annexin V-FITC positive and PI positive considered necrotic.

Spheroid-Derived Cell Sizing

The sizes of MSCs derived from adherent monolayers, or from dissociated spheroids, were determined by microscopy and flow cytometry as described previously [30]. For microscopic analysis, the cells were transferred into chambers of a Neubauer improved disposable hemocytometer (inCyto) and images captured on a Nikon Eclipse Ti-S inverted microscope using a Ds-Fi1 camera (Nikon). Cell diameters of more than 40 cells were determined using NIS-Elements AR 3.0 software. For flow cytometric analysis of cell size, 200,000 MSCs were re-suspended in 400 µl MEMα containing 2% FBS then incubated for 20 min with 100 nM of the live cell viability dye calcein AM (Molecular Probes) and 10 min with 5 µg/ml of the dead cell nuclear label 7AAD (Sigma). Cell sizes were estimated from the viable population (Calcein-bright/7AAD−) by comparing forward scatter (FS) properties of the cells and beads with a known diameter of 6, 10, and 15 µm (Life Technologies). Brackets were applied to the scatter plot at locations corresponding to the respective bead size. Gates established based on bead size FS properties were used to group the cells into four populations (<6 µm, 6–10 µm, 10–15 µm, and >15 µm).

Microarrays

MSCs cultured at 100 cells/cm2 for 7 days in CCM and in hanging drops for 3 days in CCM, MesenC, StemP, or StemP HSA were harvested for total RNA using RNeasy Mini Kit with Qiashredder columns (Qiagen) and DNase digestion (Qiagen). RNA was quantified with Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) and total of 2 µg of RNA from each sample was applied for microarrays using Whole Transcript Sense Target Labeling Assay protocol (Affymetrix) according to manufacturer’s directions. Total of 5.5 µg of cDNA was fragmented, labeled, and then hybridized (GeneChip Hybridization Oven 640, Affymetrix) on to Human Exon 1.0 ST arrays (Affymetrix). Arrays were washed, stained (GeneChip Fluidics Station 450, Affymetrix) and scanned with GeneChip Scanner (Affymetrix) and the raw data files (CEL-files) were transferred into Partek Genomics Suite 6.4 (Partek). The data were normalized using robust multi-array (RMA) algorithm and gene level analysis was performed with the Partek software. Data from spheres were compared to data from standard adherent cells to obtain fold changes.

Real-time PCR assays

Total RNA was converted into cDNA with High-Capacity cDNA RT Kit (Applied Biosystems). Real-time RT PCR was performed in triplicate for GAPDH, COX-2 (PTGS2), TSG-6 (TNFAIP6), TRAIL, IL-24, IL1A, and IL1B using Taqman® Gene Expression Assays (Life Technologies) and Taqman® Fast Master Mix (Life Technologies). Total of 10–20 ng of cDNA was used for each 20 µl reaction. Thermal cycling was performed with 7900HT System (Applied Biosystems) by incubating the reactions at 95°C for 20 s followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 1 s and 60°C for 20 s. Data were analyzed with Sequence Detection Software V2.3 (Applied Biosystems) and relative quantities (RQs) were calculated with comparative critical threshold (CT) method using RQ Manager V1.2 (Applied Biosystems).

PGE2 ELISA

Conditioned medium samples were diluted 1:50–1:100 for the PGE2 assay by ELISA kit (R&D Systems). Optical density was determined on a plate reader (FLUOstar Omega; BMG Labtech) at an absorbance of 450 nm with wavelength correction at 540 nm to correct for the optical imperfections in the plate.

TSG-6 ELISA

TSG-6 levels were determined as previously described [27] with some modifications. Briefly, wells of a 96-well plate (Costar) were coated for 6–8 h with 10 µg/ml of TSG-6 monoclonal antibody (clone A38.1.20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in 100 µl of PBS. The wells were washed 3 times with 400 µl of 1× wash buffer (R&D Systems), blocked with 100 µl of PBS containing 0.5% BSA (Thermo), then incubated on an orbital shaker (300 rpm) with 100 µl of sample (1:20 dilution) or recombinant human TSG-6 protein standards (R&D Systems) prepared in PBS containing a 1:20 dilution of non-conditioned medium (MEMα supplemented with 2% FBS, Pen-Strep, and L-glutamine). After 3 h, wells were sequentially washed, incubated for 2 h with 0.5 µg/ml biotinylated polyclonal goat anti-human TSG-6 (R&D Systems) in 100 µl of blocking solution, washed again, then incubated for 20 min with streptavidin-HRP (R&D systems). Following a final wash step, 100 µl of substrate solution (R&D Systems) was added to each well. The colorimetric reaction was terminated after 10 min with 2 N sulfuric acid (R&D systems). Optical density was determined using the plate reader.

Macrophage inflammatory assay

As previously described [29], J774A.1 mouse macrophages (ATCC) were expanded on 15 cm diameter petri dishes (Falcon) in high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS, and sub-cultured every 2–3 days at a ratio of 1:6–1:12. For the inflammatory assay, macrophages were harvested, centrifuged at 250×g for 5 min, and stimulated with LPS (Sigma). After 5 min, non-stimulated or stimulated macrophages were transferred at 25,000 – 50,000 cells/cm2 onto 12-well culture plates containing sphere-conditioned medium. The final concentration of LPS was 100 ng/ml. Sphere-conditioned medium was used at a final dilution of 1:100–1:500. After 12–24 h, medium conditioned by the macrophages was collected and clarified by centrifugation at 500×g for 5 min. Levels of mouse TNFα and IL10 were assayed with ELISA kits (R&D systems) per manufacturer’s instructions.

Mixed lymophocyte reaction

Immune response was assessed by mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) of unfractionated murine splenocytes prepared from male BALB/c mice (Jackson Laboratories). All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Texas A&M Health Science Center and in accordance with guidelines set forth by the National Institutes of Health. The spleens from the mice were excised and pushed through a 70 µm strainer into a petri dish. The cells that passed through the strainer were collected and cleared of erythrocytes by incubation for 10 minutes in red blood cell lysis solution (eBiosciences). For the assay, the splenocytes were suspended to 106 cells/ml in complete RPMI consisting of RPMI-1640 (ATCC) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Atlanta Boilogicals), 100 units/ml penicillin (Gibco), 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Gibco), and 2-mercaptoethanol (Gibco), then stimulated with an anti-CD3e antibody (eBioscience). After 5 min, 106 non-stimulated or stimulated splenocytes were transferred onto 12-well culture plates containing sphere-conditioned medium (final dilution 1:20). After 24 h, medium conditioned by the splenocytes was collected and clarified by centrifugation at 500×g for 5 min. Levels of mouse IL-2 and IFNγ were assayed with ELISA kits (R&D systems) per manufacturer’s instructions.

Culture of prostate cancer cells

LNCaP prostate cancer cells were purchased from ATCC and cultured on flasks (Corning) in complete RPMI growth medium, RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and Pen-Strep, in a humidified 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. Before reaching confluency, the cells were lifted with trypsin-EDTA and sub-cultured at a ratio of 1:3–1:6.

CyQUANT assay

LNCaP cells were mixed in the complete RPMI growth medium with 25% of CCM, StemP HSA, or sphere conditioned medium either from CCM or StemP HSA hanging drop cultures. Total of 5,000 cells in 120 µl of the mixture were seeded per well of a 96-well dish in quadruplicate. After 72 h, medium was aspirated and the dish was placed into a −80°C freezer for CyQUANT Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Life Technologies). After a minimum of 3 h, the dish was thawed and the cells on the plate were lyzed with 100 µl of buffer containing 1× Cell-lysis buffer (Life Technologies), 180 mM NaCl (Sigma), 1mM EDTA (Life Technologies), and 0.2 mg/ml RNase A (Qiagen). Known amounts of LNCaP cells were lyzed as above for the preparation of a standard curve. After 1 h, 100 µl of 1× Cell lysis buffer containing 1:100 dilution (4×) of CyQUANT (Life Technologies) was added. Fluorescence at 480 nm excitation and 520 nm emission wavelengths was measured after 5 min using the plate reader. Amount of LNCaP cells in each well was calculated based on the standard curve after the subtraction of fluorescence amount in medium only wells.

MTT assay

The 96-well dishes with LNCaP cells were prepared as for CyQUANT assay and used for MTT assay with CellTiter 96 Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Promega). After 72 h, 15 µl of the Dye Solution was added to each well and the dish was placed back into the incubator. After 4 h, 100 µl of Solubilization Solution/Stop Mix was added to each well and the plate was incubated in room temperature for 1 h. The contents of the wells were mixed and absorbance at 570 nm was measured using the microplate reader. To correct for background, absorbance values at 700 nm were subtracted from the readings.

Cell cycle analyses and viability assays of LNCaP cells

LNCaP cells were mixed in complete RPMI growth medium with 25% of non-conditioned or conditioned medium. Total of 150,000 cells in 2 ml of the mixture were added onto each well of the 6-well dish in triplicate. After 72 h, images were captured on a Nikon Eclipse Ti-S inverted microscope using a Ds-Fi1 camera (Nikon). Floating and adherent LNCaP cells were harvested and manually counted. For cell cycle analysis, cells were suspended in 1 ml of ice cold PBS and fixed by rapid addition of 3 ml cold absolute ethanol (Sigma). The cells were incubated for 1 h in 4 ml of 75% ethanol to complete fixation, washed 2 times in PBS, and then pelleted by centrifugation at 500×g for 7 min. Cells were incubated for 4–6 h at 4°C in 1 ml of PBS containing 30 U/ml RNase A (Qiagen) and 50 µg/ml propidium iodide. DNA content was measured with a flow cytometer and data analyzed using MultiCycle software (Phoenix Flow Systems). The viability of the LNCaP cells was determined as described for MSCs.

Data analysis

Data are summarized as mean ± SD. One-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test was used to calculate the levels of significance (ns, p ≥ .05; *, p < .05; **, p < .01; ***, p < .001) for data with at least 3 samples. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software).

RESULTS

Culture of MSCs in 3D under chemically defined xeno-free conditions

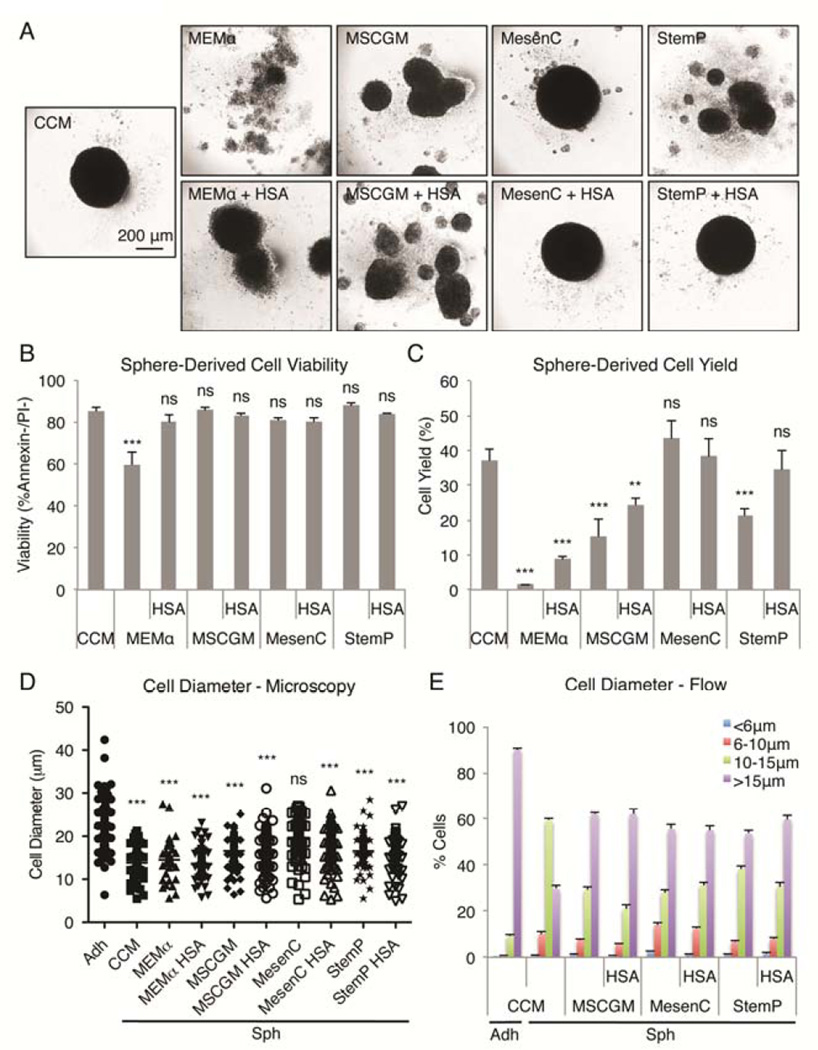

As we reported previously [27,29,30], compact spheres were formed when MSCs were suspended in hanging drops for 3 days in CCM that was previously optimized for rapid expansion of the cells as monolayers [34] (Fig. 1A). In the current work, we were interested in the effects of medium composition on MSC sphere formation and properties. Also, CCM contains 17% FBS that limits some applications of the cells because it is xenogenic for human MSCs, it is internalized by the cells, shows batch-to-batch variations, and is not desirable for some human therapies [4]. Therefore we tested the effects of various chemically defined xeno-free media preparations under the same conditions in the hanging drop cultures. In protein-free MEMα, the cells formed loose aggregates (Fig. 1A). Addition of human serum albumin (HSA), in amounts that reflected the estimated total protein content (3 times the albumin content, designated as 3×) of 17% FBS, produced aggregates of sphere-like structures that did not fuse within 3 days. Similar structures formed in the presence of one chemically defined serum-free medium (MSCGM) with or without addition of HSA. In contrast, compact single spheres formed with two other chemically defined serum-free media (MesenC and StemP) if the media were supplemented with HSA (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. Effects of medium on sphere formation by MSCs in hanging drops.

(A) Images of MSC aggregates/spheres formed in 3 day hanging drop cultures using various media formulations. Scale bar 200 µm. (B) Sphere-derived cell viability after enzymatic dissociation of the aggregates. Values are mean ± SD (n = 3). (C) Sphere-derived cell yield. Values are mean ± SD (n = 4). (D) Sphere-derived cell diameter measured by microscopy. Individual cell diameters are shown with mean (n = 40–120). (E) Sphere-derived cell diameter measured by flow cytometry. MSC sizes were estimated from forward scatter properties of the viable population (calceinAM+/7AAD−) relative to beads with known diameter (6, 10, and 15 µm). Values are mean ± SD (n = 4). ns, p ≥ .05; **, p < .01; ***, p < .001 compared to sphere-derived cell viability from CCM spheres in (B), compared to yield from CCM spheres in (C), and compared to cell diameter of adherent monolayer MSCs in (D). Abbreviations: Adh, adherent monolayer MSCs; CCM, complete culture medium; HSA, human serum albumin; MEMα, α-minimum essential medium; MesenC, Mesen Cult XF medium; MSCGM, MSC growth medium; Sph, sphere MSCs; StemP, StemPro XF medium.

Some of the MSCs in hanging drops began to die quickly resulting in minor reduction in the viability of the cells derived from spheroids [30]. The various media formulations influenced the viability and the yields of cells recovered from the aggregates after enzymatic digestion. The viability of sphere-derived cells was at least 80% in all the medium formulations except in MEMα that showed less than 60% viability (Fig. 1B). Because of the cell death, cell senescence, and cell loss in sphere harvesting, the cell yield from 3 day MSC spheres is typically less than 50% of the cell input after digestion and processing [30]. Here, the yields of cells after dissociation were lowest after digestion of the looser structures formed in MEMα and one of the chemically defined medias (MSCGM) and improved only slightly when the media were supplemented with HSA (Fig. 1C). In contrast, the yields were comparable to the yields from cultures in CCM when another chemically defined medium (MesenC) was used with or without addition of HSA, and with the third chemically defined medium (StemP) supplemented with HSA (Fig. 1C).

We have shown previously that the size of MSCs was reduced dramatically during sphere formation in CCM hanging drop cultures and the cells were able to escape lung entrapment more efficiently than MSCs from adherent cultures [30]. To study the effect of medium on the size reduction of MSCs when cultured in hanging drops, single cell suspension from digested spheres was prepared and the cell sizes measured by microscopy (Fig. 1D, S1) and flow cytometry (Fig. 1E. S2). Microscopy analysis showed that MSC sizes were different between each medium studied but in all conditions the average size was smaller than in MSCs from adherent cultures (Fig. 1D). Spheres formed in CCM and MEMα had MSCs with the smallest average size whereas the cells with the biggest average size were found in MesenC spheres (Fig. 1D, S1). Spheres prepared in StemP medium had cells with intermediate sizes. Addition of HSA to the different media had only a minor effect on MSC size (Fig. 1D). Analysis of thousands of cells by flow cytometry, based on forward scatter properties and known bead sizes, confirmed the microscopy results demonstrating that the MSCs in spheres in all the mediums tested were smaller than the cells obtained from adherent monolayer cultures (Fig. 1E, S2). Over 90% of the cells from adherent monolayer cultures had at least a 15 µm diameter whereas in all the sphere preparations only 30–60% of the cells had a diameter of at least 15 µm (Fig. 1E, S2). Furthermore, many more very small cells (less than 10 µm in diameter) were found in spheres (Fig. 1E, S2). These results demonstrated that spheres with high cell viability, high cell yield, and small cell size could be prepared in StemP chemically defined xeno-free medium supplemented with HSA.

Gene expression changes in MSCs in chemically defined 3D xeno-free conditions

As noted previously [27,29,30], there was increased expression of several potentially therapeutic genes in spheroid MSCs when prepared with CCM. The up-regulated genes included genes for immunomodulatory factors, anti-cancer factors, and IL-1 signaling molecules. Microarray assays indicated that the same genes were up-regulated and most to approximately the same levels in hanging drop cultures prepared in the CCM and in chemically defined StemP medium supplemented with HSA (Table 1). In contrast, up-regulation of the same genes did not occur or was more modest in hanging drop cultures prepared in MesenC or StemP chemically defined media without addition of HSA (Table 1). Real-time PCR assays confirmed the microarray results for COX-2, TSG-6, and IL-24, showing high up-regulation in spheres prepared in CCM, MEMα with HSA, and StemP with HSA (Fig. S3). TRAIL gene expression profile was more complex and was very high in all the spheres except ones prepared in MSCGM medium with or without HSA (Fig. S3). Furthermore, we detected significant up-regulation of IL-1 signaling molecules (IL1A and IL1B) important in activation of the anti-inflammatory molecule production by MSCs in spheres (Fig. S3) [27]. These results demonstrated that MSCs could be activated to express high levels of therapeutic genes in chemically defined xeno-free conditions using StemP medium supplemented with HSA.

Table 1.

Selected gene expression changes in MSC spheres formed in various media.

| Gene | Fold change in spheres compared to adherent monolayer cells | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCM | MesenC | StemP | StemP HSA | |

| Immunomodulatory factors | ||||

| TSG-6 | 877 | 99 | 221 | 760 |

| COX-2 | 75 | 1 | 4 | 65 |

| STC-1 | 33 | −2 | 10 | 29 |

| IL1RA | 11 | 1 | 1 | 20 |

| TSLP | 10 | 2 | 3 | 16 |

| Anti-cancer factors | ||||

| TRAIL | 32 | 36 | 39 | 30 |

| IL-24 | 29 | −2 | 1 | 11 |

| CD82 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 |

| IL-1 signaling molecules | ||||

| IL-1A | 90 | 1 | 2 | 108 |

| IL-1B | 121 | 1 | 3 | 103 |

| IL-1R1 | 18 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| IRAK2 | 22 | 6 | 16 | 24 |

| Other | ||||

| CXCR4 | 102 | 1 | 2 | 11 |

| SOD2 | 48 | 2 | 9 | 40 |

| GDF15 | 39 | 8 | 41 | 45 |

| MMP1 | 18 | −5 | 1 | 17 |

| IL-6 | 16 | −6 | −6 | 24 |

| PTHLH | 11 | −2 | 2 | 3 |

| SFRP1 | 8 | −2 | 3 | 3 |

| LIF | 7 | −4 | −2 | 7 |

| HGF | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| TWIST1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

Anti-inflammatory effects of MSC spheres cultured in chemically defined xeno-free conditions

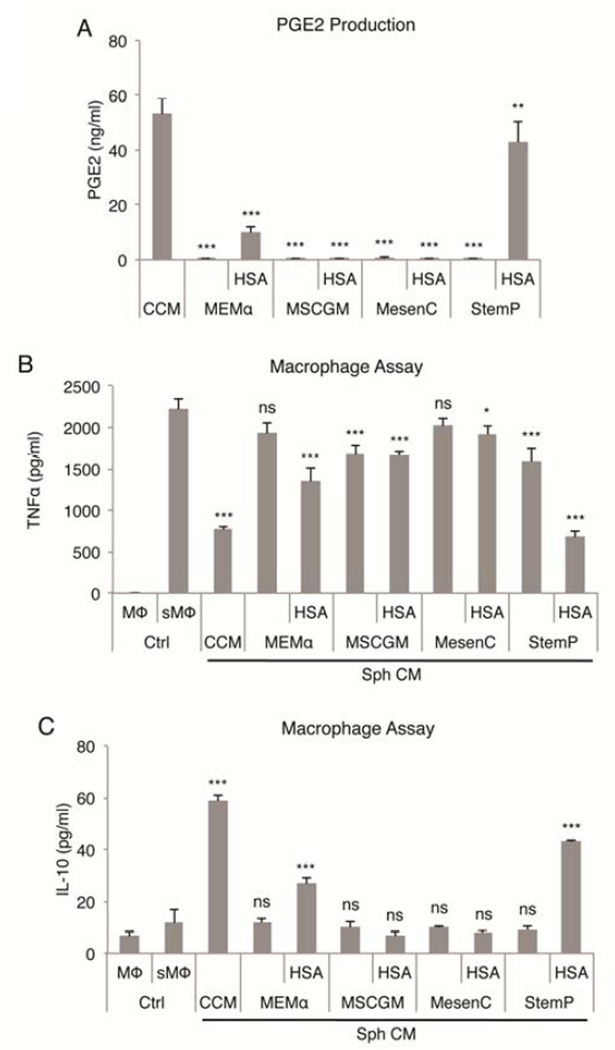

One of the striking features of spheroid MSCs cultured in CCM was large secretion of the immunomodulatory factor PGE2 [27,29]. There was little secretion of PGE2 from the loose aggregates of MSCs formed in hanging drop cultures prepare in MEMα or MSCGM with or without addition of HSA (Fig. 2A). Surprisingly, there was only barely detectable levels of PGE2 secreted by the compact spheres prepared in MesenC with addition of HSA. In contrast, high levels were seen in the compact spheres prepared in StemP with HSA (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Effects of medium on anti-inflammatory properties of MSC spheres.

(A) Secretion of PGE2 by MSC spheres after 3 day culture in hanging drops in CCM or in chemically defined xeno-free conditions. (B,C) Anti-inflammatory effects of MSC sphere conditioned medium using various chemically defined xeno-free medium preparations measured as reduction in TNFα and increase in IL-10 secretion by LPS-stimulated macrophages. Values are mean ± SD (n = 4). ns, p ≥ .05; *, p < .05; **, p <.01; ***, p < .001 compared to conditioned medium from spheres cultured in CCM in (A) and compared to stimulated macrophage control in (B) and (C). Abbreviations: CCM, complete culture medium; CM, conditioned medium; HSA, human serum albumin; MEMα, α-minimum essential medium; MesenC, Mesen Cult XF medium; MSCGM, MSC growth medium; MΦ, macrophage; sMΦ, stimulated macrophage; Sph, sphere MSCs; StemP, StemPro XF medium.

To study the anti-inflammatory effects of the various spheres, we used a system of LPS-stimulated macrophages treated with conditioned medium from sphere cultures [29]. We had previously shown that the secretion of PGE2 by MSC spheres cultured in CCM decreased the secretion of pro-inflammatory TNFα and increased the secretion of anti-inflammatory IL-10 by the stimulated macrophages [29]. As expected, similar effects were seen with spheroid MSCs prepared in StemP with HSA but not in the other media (Fig. 2B, 2C).

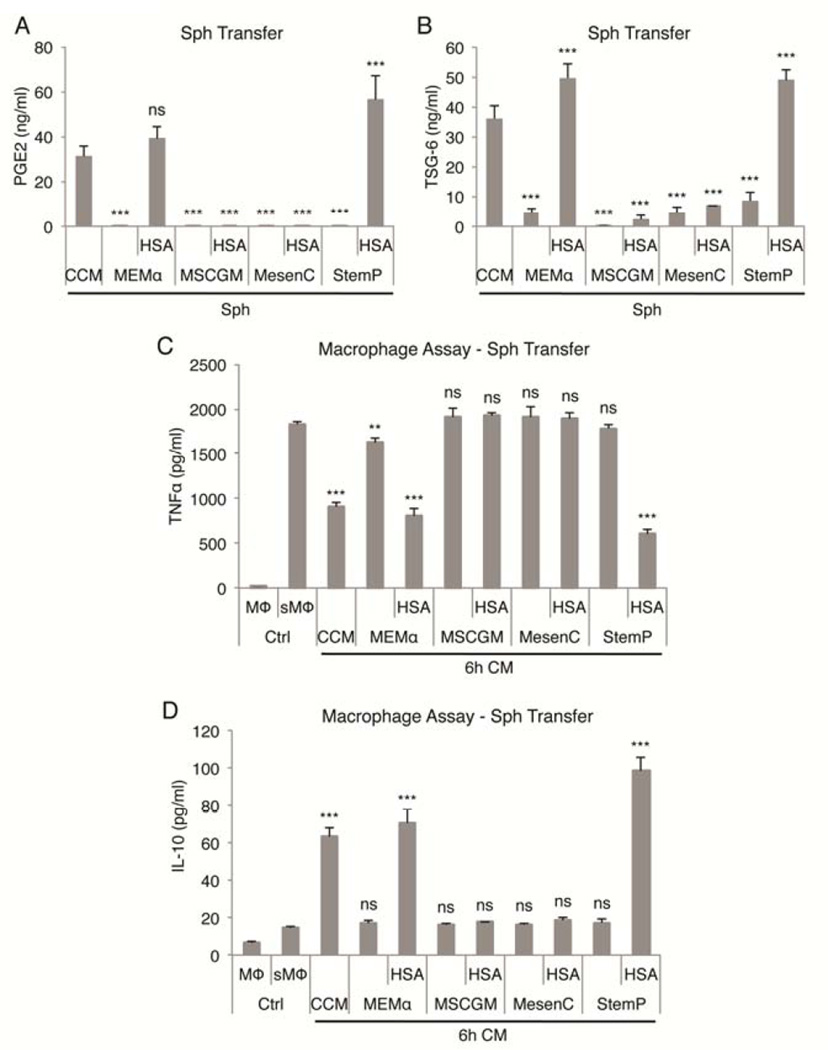

To study if the anti-inflammatory effects were maintained after sphere formation, spheres were transferred into fresh low-protein medium for 6 h. Only spheres formed in CCM, MEMα with HSA, and StemP with HSA secreted high amounts of PGE2 and TSG-6 (Fig. 3A, 3B). Accordingly, the biggest reduction in TNFα and increase in IL-10 secretion was detected in macrophages cultured with medium conditioned by spheres prepared in CCM, MEMα with HSA, and StemP with HSA demonstrating the potent anti-inflammatory effects of these MSC sphere preparations (Fig. 3C, 3D). Conditioned medium from CCM and StemP HSA cultures also suppressed the activation of T-cells demonstrated by the reduction of IL-2 and IFN-γ secretion by CD3 stimulated splenocytes in a mixed lymphocyte reaction (Fig. S4).

Figure 3. Continuous secretion of anti-inflammatory factors PGE2 and TSG-6 by MSC spheres from chemically defined xeno-free cultures.

(A,B) Secretion of PGE2 and TSG-6 by MSC spheres from chemically defined xeno-free conditions after 6 h transfer into low-protein medium. (C,D) Anti-inflammatory effects of low-protein medium conditioned by MSC spheres from chemically defined xeno-free hanging drop cultures measured as reduction in TNFα and increase in IL-10 secretion by LPS-stimulated macrophages. Values are mean ± SD (n = 4). ns, p ≥ .05; **, p < .01; ***, p < .001 compared to 6 h transfer conditioned medium from spheres cultured in CCM in (A) and (B) and compared to stimulated macrophage control in (C) and (D). Abbreviations: CCM, complete culture medium; CM, conditioned medium; Ctrl, macrophage only controls; HSA, human serum albumin; MEMα, α-minimum essential medium; MesenC, Mesen Cult XF medium; MSCGM, MSC growth medium; MΦ, macrophage; sMΦ, stimulated macrophage; Sph, sphere MSCs; StemP, StemPro XF medium.

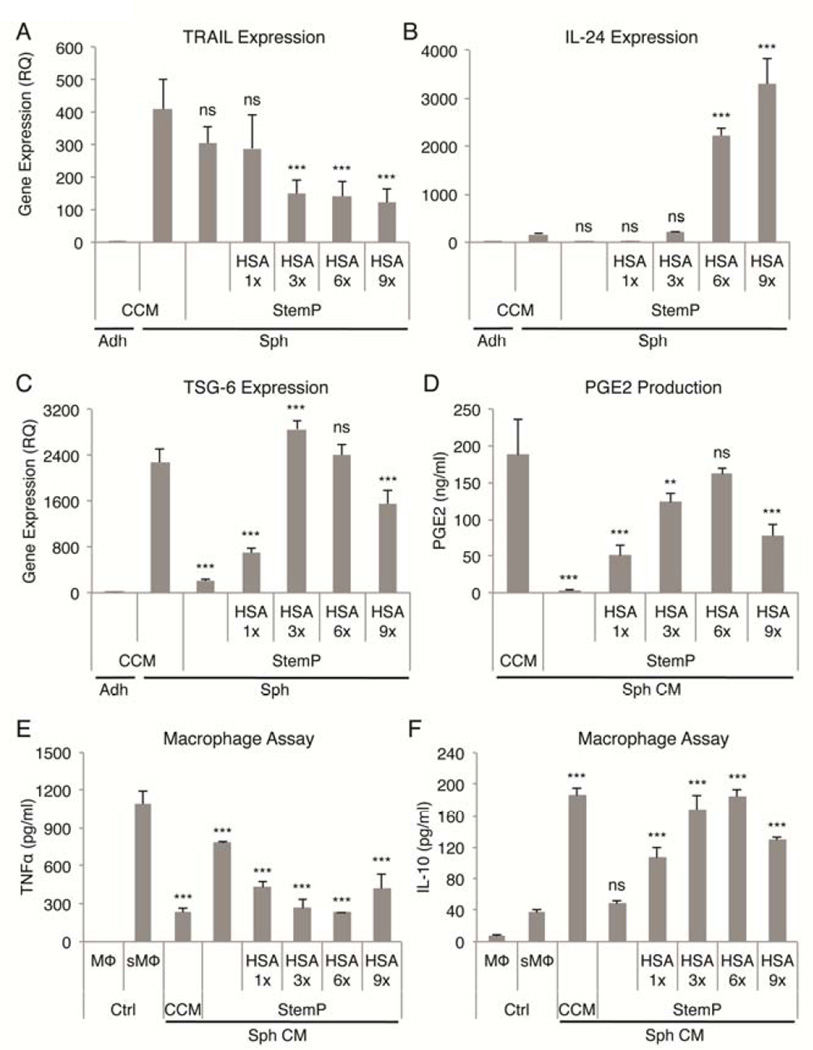

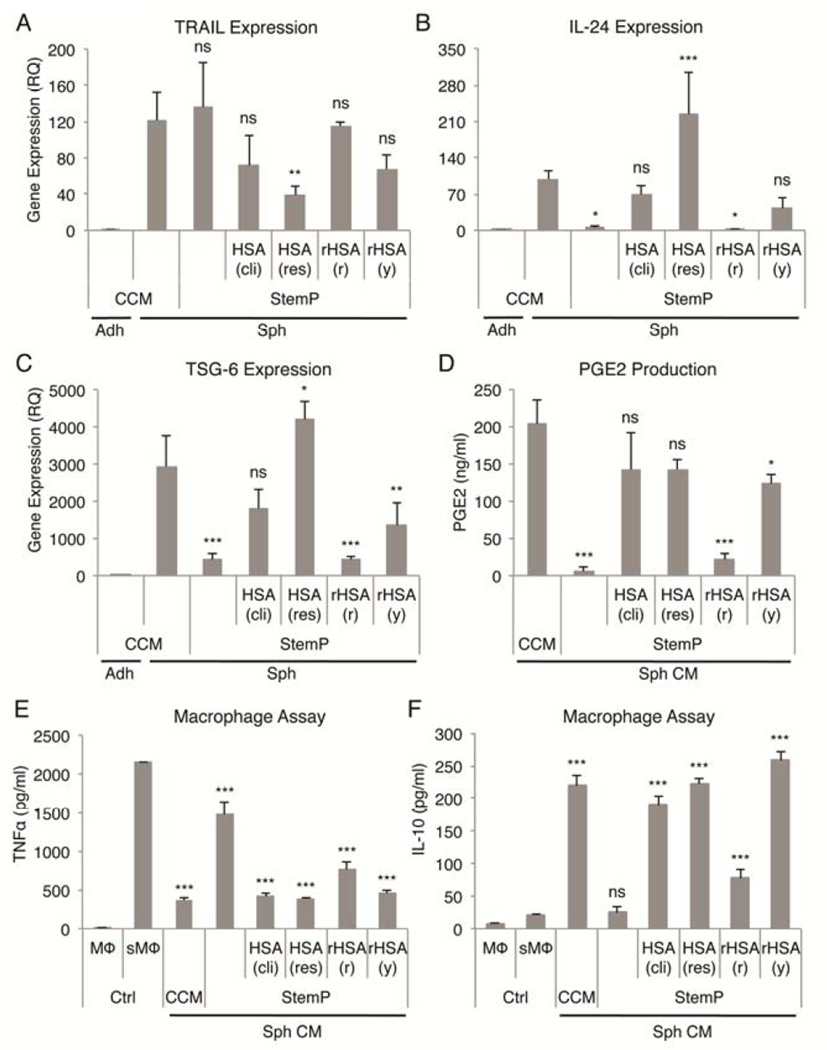

HSA supplemented StemP medium supports activation of MSCs in 3D cultures

Since the optimal chemically defined xeno-free 3D conditions (high activation status, compact spheres, high viability) were achieved with StemP medium supplemented with HSA (designated as 3×), we tested if the amount of HSA would affect the activation of MSCs. Interestingly, TRAIL expression was not increased by the addition of HSA (Fig. 4A), whereas IL-24 expression was up-regulated with increased amounts of HSA and was much higher than in spheres cultured in CCM (Fig. 4B). TSG-6 expression was the highest with 3× HSA reaching similar up-regulation levels as in CCM and decreased with higher doses (Fig. 4C). COX-2 expression increased with additional HSA until reaching plateau at 6× HSA concentration at which point the expression was higher than in CCM (Fig. S5). Similarly, PGE2 secretion increased with addition of HSA until reaching the peak at 6× HSA concentration (comparable level to expression in CCM) and declining with 9× HSA concentration (Fig. 4D). As expected, the most potent anti-inflammatory effects were observed with 3× and 6× HSA, amounts that were comparable to effects seen with conditioned medium from spheres cultured in CCM (Fig. 4E, 4F).

Figure 4. HSA dose effect on activation of MSCs in chemically defined 3D xeno-free cultures.

(A–C) Real-time PCR data of TRAIL, IL-24, and TSG-6 expression in MSC spheres cultured with various doses of HSA (1×, 3×, 6×, 9×) in chemically defined StemP xeno-free medium. Relative quantities were determined comparing to adherent monolayer MSCs cultured in CCM. (D) PGE2 secretion by MSC spheres formed in StemP medium supplemented with various HSA doses. (E,F) Anti-inflammatory effects of sphere conditioned medium from 3D cultures with StemP medium supplemented with various HSA doses measured as reduction in TNFα and increase in IL-10 secretion by LPS-stimulated macrophages. Values are mean ± SD (n = 4). ns, p ≥ .05; **, p < .01; ***, p < .001 compared to MSC spheres cultured in CCM in (A), (B), and (C), compared to conditioned medium from MSC spheres cultured in CCM in (D), and compared to stimulated macrophage control in (E) and (F). Abbreviations: Adh, adherent monolayer MSCs; CCM, complete culture medium; CM, conditioned medium; Ctrl, macrophage only controls; HSA, human serum albumin; MΦ, macrophage; RQ, relative quantity; sMΦ, stimulated macrophage; Sph, sphere MSCs; StemP, StemPro XF medium.

In the experiments up to this point, both research grade (HSA res) and clinical grade (HSA cli) HSA products had been used interchangeably but not directly compared. Furthermore, we wanted to test if use of recombinant HSA expressed in rice [rHSA (r)] and yeast [rHSA (y)] would achieve the same level of activation in MSCs as the HSA products isolated from human blood. As demonstrated before (Fig. S3), addition of HSA was not required for the up-regulation of TRAIL expression in MSC spheres (Fig. 5A). However, HSA was required for the up-regulation of IL-24 expression, which was highest with research grade HSA and did not change with StemP only or StemP supplemented with recombinant HSA from rice (Fig. 5B). TSG-6 expression followed a similar pattern to the IL-24 expression with only minimal up-regulation detected with StemP only and StemP supplemented with recombinant HSA from rice (Fig. 5C). COX-2 expression levels (Fig. S6) and PGE2 secretion (Fig. 5D) were similar in CCM and StemP supplemented with clinical or research grade HSA and recombinant HSA expressed in yeast. The most potent anti-inflammatory effects were observed with conditioned medium from spheres cultured in CCM or StemP supplemented with clinical grade HSA, research grade HSA, or recombinant HSA expressed in yeast (Fig. 5E, D). These results demonstrated that supplementation of StemP medium with either HSA isolated from blood or recombinant HSA expressed in yeast resulted in the optimal activation status of MSCs.

Figure 5. Comparison of different HSA preparations in activating MSCs in chemically defined 3D xeno-free cultures.

(A–C) Real-time PCR data of TRAIL, IL-24, and TSG-6 expression with StemP medium supplemented with different HSA preparations. Relative quantities were determined comparing to adherent monolayer MSCs. (D) PGE2 secretion by MSC spheres formed in StemP medium supplemented with various HSA preparations. (E,F) Anti-inflammatory effects of sphere conditioned medium from 3D cultures with StemP medium supplemented with various HSA preparations measured as reduction in TNFα and increase in IL-10 secretion by LPS-stimulated macrophages. Values are mean ± SD (n = 3–4). ns, p ≥ .05; *, p < .05; ***, p < .001 compared to MSC spheres cultured in CCM in (A), (B), and (C), compared to conditioned medium from MSC spheres cultured in CCM in (D), and compared to stimulated macrophage control in (E) and (F). Abbreviations: Adh, adherent monolayer MSCs; CCM, complete culture medium; CM, conditioned medium; Ctrl, macrophage only controls; HSA (cli), clinical grade human serum albumin isolated from blood; HSA (res), research grade human serum albumin isolated from blood; rHSA (r), recombinant human serum albumin expressed in rice; rHSA (y), recombinant human serum albumin expressed in yeast; MΦ, macrophage; sMΦ, stimulated macrophage; Sph, sphere MSCs; StemP, StemPro XF medium.

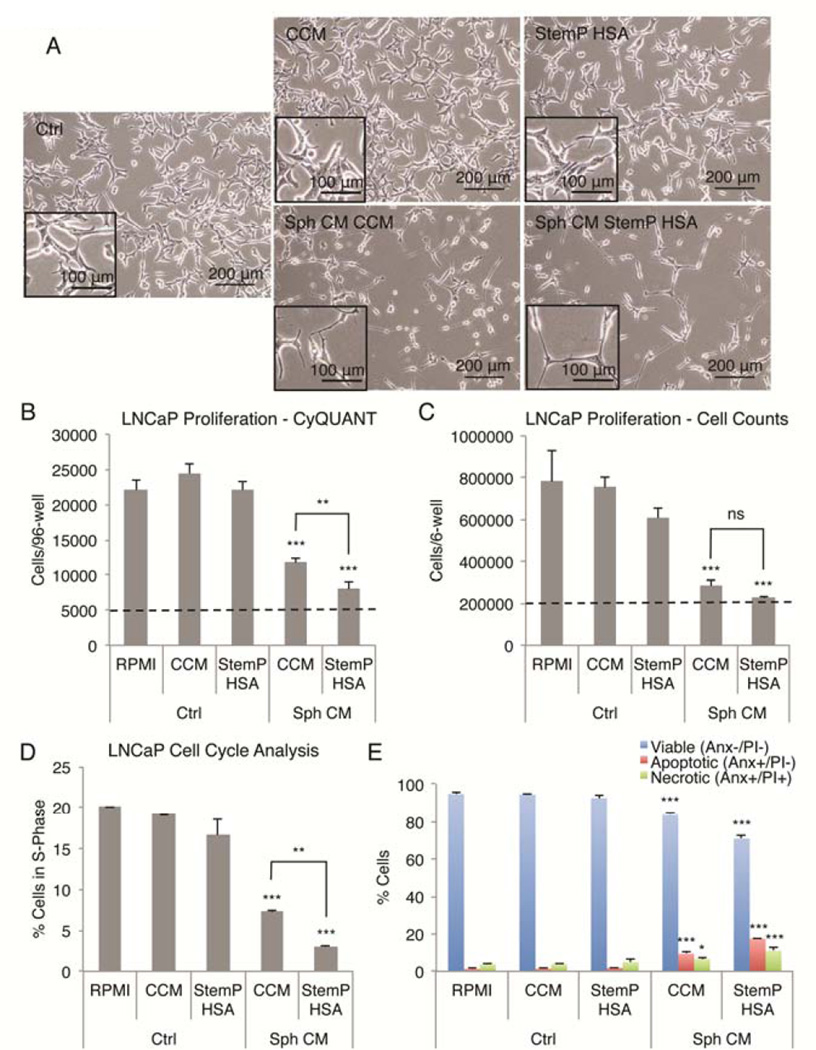

Pre-activated MSCs suppress the growth of prostate cancer cells

Studies by us [30] and others [20] have suggested that 3D activated MSCs possess anti-cancer properties. Recently, 3D activated MSCs were shown to suppress the growth of a prostate cancer cell line (LNCaP) and this effect was suggested to be mediated by IL-24 [20]. Since 3D activated MSCs expressed IL-24 and other anti-cancer molecules, we wanted to study the proposed anti-cancer effects in more detail using the LNCaP cells. When LNCaP cells were treated with conditioned medium (1:4 dilution) from spheres cultured in either CCM or chemically defined xeno-free medium (StemP) supplemented with HSA, the cells appeared to shrink their cell bodies and form thin, branched processes (Fig. 6A). This phenomenon has been termed neuroendoderm differentiation of the LNCaP cells [35]. In addition, less LNCap cells were recovered from three-day cultures with conditioned medium from MSC sphere cultures as in the control medium demonstrated by CyQUANT (Fig. 6B) and MTT (Fig. S7) assays and manual cell counts (Fig. 6C). In all the assays, suppression of LNCaP cell growth was more effective when using the conditioned medium obtained from spheres cultured in StemP medium supplemented with HSA than the conditioned medium from spheres cultured in CCM (Fig, 6B, C, and S7).

Figure 6. Reduction of prostate cancer cell growth by MSC spheres prepared in chemically defined xeno-free conditions.

(A) Images of LNCaP prostate cancer cells treated with various non-conditioned and conditioned medium preparations. Cells decreased in size and developed long and thin extensions in the conditioned medium from spheroids. Scale bar 200 µm (inset 100 µm). (B.C) MSC sphere conditioned medium reduces the growth of LNCaP cells measured with CyQUANT assay and manual cell counts after 3-day culture. Initial cell number is shown with a dashed line. (D) Sphere conditioned medium treatment of LNCaP cells results in cell cycle arrest with decrease in cells in S phase. (E) Sphere conditioned medium treatment causes LNCaP cell death with increase in both apoptotic and necrotic cells. Values are mean ± SD (n = 3–4). **, p < .01; ***, p < .001 compared to appropriate medium controls and to each other in (B,C, and D). Abbreviations: Anx, Annexin V; CCM, complete culture medium; CM, conditioned medium; Ctrl, non-conditioned medium controls; HSA, human serum albumin; PI, propidium iodide; RPMI, cancer cell medium control; Sph, sphere MSCs; StemP, StemPro XF medium.

The suppression of LNCaP cell growth could be explained by cell cycle arrest and/or killing of the cancer cells by the conditioned medium. To distinguish between these two phenomena, we studied the cell cycle profiles and the viability of the LNCaP cells after co-culture with MSC sphere-conditioned medium. DNA content analysis demonstrated that approximately 20% of the LNCaP cells were in S-phase and actively dividing under normal conditions (Fig. 6D, S8). When conditioned medium was added, approximately 7% of the LNCaP cells were in the S-phase with sphere-conditioned medium from CCM cultures and only approximately 3% of the LNCap cells were in S-phase with conditioned medium from StemP HSA cultures (Fig. 6D, S8). When the viability of the LNCaP cells was studied, reduction in the number of viable cells was observed with sphere-conditioned medium, whereas the percentage of apoptotic and necrotic LNCaP cells was increased (Fig. 6E, S9). Furthermore, the conditioned medium from StemP HSA cultures was more effective in causing cell cycle arrest and cell death of the LNCaP cells than the conditioned medium from the hanging drop cultures using CCM (Fig. 6, S8, S9). Altogether, these results suggested that MSC sphere-conditioned medium (CCM and StemP HSA) suppressed the LNCaP cell growth by cell cycle arrest and reduced the viability of the cells by increasing the apoptosis and necrosis of the cancer cells.

DISCUSSION

One of the intriguing features of MSCs is the multiple ways in which they respond to different microenvironments [2,3,36]. Their responsiveness or plasticity probably explains their ability to produce improvements in a variety of animal models in which they respond to paracrine, hormonal, and neural signals to secrete molecules and microvesicles or make cell-to-cell contacts that can transfer mitochondria [37,38]. As a result the cells can modulate inflammation and acquired immunity, enhance proliferation and differentiation of progenitor cells, and alter apoptosis. The same plasticity of MSCs makes them highly sensitive to culture conditions so that there are differences in the properties of culture-expanded MSCs dependent on conditions such as the composition of the medium, density of the cells at plating and harvesting, and the population doublings the cells undergo [3].

Culture of MSCs in non-adherent culture conditions so that they form spheres minimizes some of the variables introduced by expansion of MSCs in culture [14–31]. Also it more closely reproduces the state of the cells in vivo [12,13]. In optimal medium for expansion of MSCs as monolayers, the cells in hanging drops aggregate into a single sphere and condense to about one-fourth their volume in 3 days [30]. The cells cease proliferating as they aggregate into spheres, but show a high proliferative capacity after a brief delay and a high differentiation ability if the spheres are dissociated and plated as monolayers [30]. If the size of the sphere is limited to about 25,000 cells, there is little necrosis or apoptosis during incubation for 3 days but signaling triggered by caspases, Notch, IL-1, and other molecules that induce production of therapeutic molecules such as TSG-6, STC-1, and COX2 [27,29]. The results here demonstrated that the spheres can also be formed in chemically defined xeno-free medium but the composition of the medium is critical for assembly of the cells into compact spheres and the patterns of the genes expressed. Addition of HSA appears critical for formation of compact spheres with high viability MSCs and for expression and secretion of potentially therapeutic anti-inflammatory (TSG-6, PGE2) and anti-cancer (IL-24) molecules. However, HSA did not appear to be necessary for activation of TRAIL expression. HSA not only increases the total protein content of the medium but likely also stabilizes other molecules in the chemically defined xeno-free medium that could partake in the MSC activation process. Also, addition of another xeno-free source of growth factors, such as human platelet lysate, might provide similar results to HSA in 3D activation of MSCs. Clearly different components exist in various commercially available xeno-free media, as demonstrated by the difference in sphere formation, viability, and activation state. It is unclear though, which components are responsible for each function and thus further work is required to define the critical molecules for MSC activation in 3D cultures.

Therefore the results suggest that assembly of MSCs into spheres in xeno-free conditions after they have been expanded as monolayers may provide an important protocol for preparing activated MSCs for research and some clinical applications. Although hand-generated hanging drop cultures were employed here, the protocol can likely be automated by using laser-based, inkjet-based, or valve-based printing techniques that can deposit MSCs with precise quantity and high viability in a high throughput manner [39].

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported in part by NIH grant P40RR17447 and CPRIT grant RP110553-P1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions: JHY: conception and design, provision of study material or patients, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript; TJB: conception and design, provision of study material or patients, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript; AT: provision of study material or patients, collection and/or assembly of data; DJP: financial support, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript.

DISCLOSURE OF INTEREST

DJP is chair of the scientific advisory committee of a biotech (Temple Therapeutics LLC) with an interest in MSCs. He has a small equity position in the company. The other authors have no commercial, proprietary or financial interest in the products or companies described in this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Evans JB, Syed BA. New hope for dry AMD? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:501–502. doi: 10.1038/nrd4038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keating A. Mesenchymal stromal cells: new directions. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:709–716. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prockop DJ, Kota DJ, Bazhanov N, et al. Evolving paradigms for repair of tissues by adult stem/progenitor cells (MSCs) J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:2190–2199. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spees JL, Gregory CA, Singh H, et al. Internalized antigens must be removed to prepare hypoimmunogenic mesenchymal stem cells for cell and gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2004;9:747–756. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francois M, Copland IB, Yuan S, et al. Cryopreserved mesenchymal stromal cells display impaired immunosuppressive properties as a result of heat-shock response and impaired interferon-gamma licensing. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:147–152. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2011.623691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee RH, Yoon N, Reneau JC, et al. Preactivation of human MSCs with TNF-alpha enhances tumor-suppressive activity. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:825–835. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waterman RS, Henkle SL, Betancourt AM. Mesenchymal stem cell 1 (MSC1)-based therapy attenuates tumor growth whereas MSC2-treatment promotes tumor growth and metastasis. Plos One. 2012;7:e45590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Betancourt AM. New Cell-Based Therapy Paradigm: Induction of Bone Marrow-Derived Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cells into Pro-Inflammatory MSC1 and Anti-inflammatory MSC2 Phenotypes. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/10_2012_141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waterman RS, Tomchuck SL, Henkle SL, et al. A new mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) paradigm: polarization into a pro-inflammatory MSC1 or an Immunosuppressive MSC2 phenotype. Plos One. 2010;5:e10088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teare DO, Emmison N, Ton-That C, et al. Effects of Serum on the Kinetics of CHO Attachment to Ultraviolet-Ozone Modified Polystyrene Surfaces. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2001;234:84–89. doi: 10.1006/jcis.2000.7282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen M, Horbett TA. The effects of surface chemistry and adsorbed proteins on monocyte/macrophage adhesion to chemically modified polystyrene surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;57:336–345. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20011205)57:3<336::aid-jbm1176>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Achilli TM, Meyer J, Morgan JR. Advances in the formation, use and understanding of multicellular spheroids. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012;12:1347–1360. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.707181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Page H, Flood P, Reynaud EG. Three-dimensional tissue cultures: current trends and beyond. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;352:123–131. doi: 10.1007/s00441-012-1441-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qihao Z, Xigu C, Guanghui C, et al. Spheroid formation and differentiation into hepatocytelike cells of rat mesenchymal stem cell induced by co-culture with liver cells. Dna Cell Biol. 2007;26:497–503. doi: 10.1089/dna.2006.0562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potapova IA, Doronin SV, Kelly DJ, et al. Enhanced recovery of mechanical function in the canine heart by seeding an extracellular matrix patch with mesenchymal stem cells committed to a cardiac lineage. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H2257–H2263. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00219.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potapova IA, Gaudette GR, Brink PR, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells support migration, extracellular matrix invasion, proliferation, and survival of endothelial cells in vitro. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1761–1768. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang CC, Chen CH, Hwang SM, et al. Spherically symmetric mesenchymal stromal cell bodies inherent with endogenous extracellular matrices for cellular cardiomyoplasty. Stem Cells. 2009;27:724–732. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang W, Itaka K, Ohba S, et al. 3D spheroid culture system on micropatterned substrates for improved differentiation efficiency of multipotent mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2705–2715. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie QP, Huang H, Xu B, et al. Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into insulin-producing cells upon microenvironmental manipulation in vitro. Differentiation. 2009;77:483–491. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frith JE, Thomson B, Genever PG. Dynamic three-dimensional culture methods enhance mesenchymal stem cell properties and increase therapeutic potential. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2009;16:735–749. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2009.0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saleh FA, Whyte M, Genever PG. Effects of endothelial cells on human mesenchymal stem cell activity in a three-dimensional in vitro model. Eur Cell Mater. 2011;22:242–257. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v022a19. discussion 257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saleh FA, Genever PG. Turning round: multipotent stromal cells, a three-dimensional revolution? Cytotherapy. 2011;13:903–912. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2011.586998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jing Y, Jian-Xiong Y. 3-D spheroid culture of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell of rhesus monkey with improved multi-differentiation potential to epithelial progenitors and neuron in vitro. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2011;39:808–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2011.02560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baraniak PR, McDevitt TC. Scaffold-free culture of mesenchymal stem cell spheroids in suspension preserves multilineage potential. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:701–711. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1215-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki S, Muneta T, Tsuji K, et al. Properties and usefulness of aggregates of synovial mesenchymal stem cells as a source for cartilage regeneration. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R136. doi: 10.1186/ar3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isern J, Martin-Antonio B, Ghazanfari R, et al. Self-renewing human bone marrow mesenspheres promote hematopoietic stem cell expansion. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1714–1724. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartosh TJ, Ylostalo JH, Bazhanov N, et al. Dynamic Compaction of Human Mesenchymal Stem/Precursor Cells Into Spheres Self-Activates Caspase-Dependent IL1 Signaling to Enhance Secretion of Modulators of Inflammation and Immunity (PGE2, TSG6, and STC1) Stem Cells. 2013;31:2443–2456. doi: 10.1002/stem.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sart S, Tsai AC, Li Y, et al. Three-dimensional Aggregates of Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Cellular Mechanisms, Biological Properties, and Applications. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2013.0537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ylostalo JH, Bartosh TJ, Coble K, et al. Human mesenchymal stem/stromal cells cultured as spheroids are self-activated to produce prostaglandin E2 that directs stimulated macrophages into an anti-inflammatory phenotype. Stem Cells. 2012;30:2283–2296. doi: 10.1002/stem.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartosh TJ, Ylostalo JH, Mohammadipoor A, et al. Aggregation of human mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) into 3D spheroids enhances their antiinflammatory properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13724–13729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008117107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arufe MC, De la Fuente A, Fuentes-Boquete I, et al. Differentiation of synovial CD-105(+) human mesenchymal stem cells into chondrocyte-like cells through spheroid formation. J Cell Biochem. 2009;108:145–155. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Block GJ, Ohkouchi S, Fung F, et al. Multipotent stromal cells are activated to reduce apoptosis in part by upregulation and secretion of stanniocalcin-1. Stem Cells. 2009;27:670–681. doi: 10.1002/stem.20080742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee RH, Pulin AA, Seo MJ, et al. Intravenous hMSCs improve myocardial infarction in mice because cells embolized in lung are activated to secrete the anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sekiya I, Larson BL, Smith JR, et al. Expansion of human adult stem cells from bone marrow stroma: conditions that maximize the yields of early progenitors and evaluate their quality. Stem Cells. 2002;20:530–541. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.20-6-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abrahamsson PA. Neuroendocrine differentiation in prostatic carcinoma. Prostate. 1999;39:135–148. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19990501)39:2<135::aid-pros9>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernardo ME, Fibbe WE. Mesenchymal stromal cells: sensors and switchers of inflammation. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:392–402. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spees JL, Olson SD, Whitney MJ, et al. Mitochondrial transfer between cells can rescue aerobic respiration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1283–1288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510511103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Islam MN, Das SR, Emin MT, et al. Mitochondrial transfer from bone-marrow-derived stromal cells to pulmonary alveoli protects against acute lung injury. Nat Med. 2012;18:759–765. doi: 10.1038/nm.2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Faulkner-Jones A, Greenhough S, King JA, et al. Development of a valve-based cell printer for the formation of human embryonic stem cell spheroid aggregates. Biofabrication. 2013;5 doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/5/1/015013. 015013-5082/5/1/015013. Epub 2013 Feb 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.