Abstract

Background

Therapy for childhood acute myeloid leukemia (AML) has historically included chemotherapy with or without autologous bone marrow transplant (autoBMT) or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (alloBMT). We sought to compare health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL) outcomes between these treatment groups.

Procedure

Five-year survivors of AML diagnosed before age 21 and enrolled and treated from 1979 to 1995 on one of 4 national protocols were interviewed. These survivors or proxy caregivers completed a health questionnaire and an HRQOL measure.

Results

Of 180 survivors, 100 were treated with chemotherapy only, 26 with chemotherapy followed by autoBMT, and 54 with chemotherapy followed by alloBMT. Median age at interview was 20 years (range 8 to 39). Twenty-one percent reported a severe or life-threatening chronic health condition (chemotherapy-only 16% vs. autoBMT 21% vs. alloBMT 33%; p=0.02 for chemotherapy-only vs. alloBMT). Nearly all (95%) reported excellent, very good or good health. Reports of cancer-related pain and anxiety did not vary between groups. HRQOL scores among 136 participants ≥ 14 years of age were similar among groups and to the normative population, though alloBMT survivors had a lower physical mean summary score (49.1 alloBMT vs. 52.2 chemotherapy-only; p=0.03). Multivariate analyses showed the presence of severe chronic health conditions to be a strong predictor of physical but not mental mean summary scores.

Conclusions

Overall HRQOL scores were similar among treatment groups, although survivors reporting more health conditions or cancer-related pain had diminished HRQOL. Attention to chronic health conditions and management of cancer-related pain may improve QOL.

Keywords: pediatric, bone marrow transplantation, acute myeloid leukemia, late effects, chronic health condition, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Although many studies have assessed health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in cancer survivors, few have focused exclusively on survivors of acute myeloid leukemia (AML).[1] From 1979 to 1995, legacy Children's Oncology Group (COG) therapeutic protocols for AML consisted of chemotherapy followed by allogeneic bone marrow transplant (alloBMT) for patients with a matched related donor.[2] Patients without a matched related donor received either chemotherapy-only or chemotherapy including high dose chemotherapy followed by autologous BMT (autoBMT).

All therapeutic strategies for AML involve intensive chemotherapy. Previous trials suggested an overall survival advantage for patients who received alloBMT, thus alloBMT has historically been recommended for children and adolescents with AML and a matched sibling donor.[3, 4] AutoBMT is no longer routinely utilized in treatment of AML. AlloBMT for those without a matched related donor has been recommended in more recent years for patients with higher risk disease who have an available matched unrelated donor or following relapse.[5]

AlloBMT has been associated with a wide variety of potential long-term complications including endocrine dysfunction, cardiopulmonary abnormalities, and osteoporosis.[6] Most allogeneic BMT survivors will have impaired fertility and some will face secondary malignancies. Chronic graft versus host disease (cGVHD) is a specific potential complication that may result in functional limitations. Any of these late effects may affect the patient's quality of life. Although some studies have assessed medical late effects in adult patients following BMT, fewer studies have assessed them in survivors who underwent BMT during childhood or adolescence. [1]

Mulrooney et al.[7] and Molgaard-Hansen[8] et al. have described medical and social outcomes in survivors of childhood AML who received chemotherapy-only. However, the physical and psychosocial implications of intensive therapies such as BMT necessitate careful evaluation of the late effects associated with any form of treatment for childhood AML.

This study sought to assess the prevalence of chronic health conditions and measure HRQOL as defined by the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) (©1994–2013 RAND Corp.), to determine which demographic and treatment characteristics and medical conditions decreased health-related quality of life in survivors of childhood AML.

METHODS

Study Participants

Subjects were eligible for this study if diagnosed with AML when younger than 21 years of age and treated on one of 4 legacy COG AML trials (CCG-251, 213, 2861 and 2891). Those who survived at least 5 years following diagnosis were contacted by telephone for participation. Participants who provided consent completed several questionnaires by telephone and mail. For participants in this study who were also participants in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS), results of the CCSS baseline questionnaire were shared between studies (see below). Telephone interviews were conducted by four trained, experienced interviewers. All interviewers were certified on the specific instruments. Telephone monitoring and quality control checks were done. For telephone interviews, each subject was called a total of 6 times with messages left after calls 3 and 6. If no response was obtained from these attempts, this was considered a refusal.

Previous Treatment

Detailed AML treatment information has been previously described and is summarized in Supplemental Table 1.[9–14] A Spanish-speaking interviewer was provided for Spanish-speaking participants. All participants provided informed consent/assent and protocols were reviewed and approved by the local Human Subjects Committees. Clinical data were obtained from the COG Statistical and Data Center. All AML induction regimens in this analysis included cytarabine and an anthracycline. Post-induction treatment consisted of chemotherapy or BMT, as determined by the availability of a matched sibling donor. BMT preparatory regimens included total body irradiation (TBI) with cyclophosphamide, or busulfan with cyclophosphamide.

CCSS Baseline Questionnaire

The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) baseline questionnaire is a measure of late effects based in part on the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Its use in the childhood cancer survivor population has been extensively reported.[15–17] This measure assesses late effects in a variety of physical and psychosocial domains, including specific medical conditions, socioeconomic status, and need for health care interventions. The presence of chronic health conditions, education and employment were ascertained via the CCSS questionnaire using self or proxy report based on age. The CCSS questionnaire health conditions section states: “The next series of questions relate to medical conditions that have ever occurred in your lifetime. Please indicate by filling in the circle if a doctor or medical professional has ever told you that you have any of the following medical conditions.” These answers were used to determine chronic medical conditions. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using self-reported height and weight. The CCSS baseline questionnaire is available at http://ccss.stjude.org/docs/ccss/survey-baseline.pdf.

Chronic health conditions

Scoring of chronic health conditions was performed according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 3) as described by Oeffinger et al.[18] Using this methodology, 137 health conditions were scored as: grade 1 (mild); grade 2 (moderate); grade 3 (severe); grade 4 (life threatening or disabling); or grade 5 (fatal). For this analysis, grades 3 and 4 were considered severe.

HRQOL Measure

HRQOL was assessed by telephone interview using the SF-36, a validated measure of HRQOL for those 14 years of age and older. The SF-36 includes 2 summary scores in the physical health and mental health domains. Using norm-based scoring as in this analysis, the population norm is 50, with a standard deviation of 10. Higher scores indicate higher HRQOL. A difference of 4 to 10 points from the mean is considered to represent a moderate effect.[19]

Statistical Analysis

Demographic differences between two treatment groups were analyzed using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables (ages and time since diagnosis); chi-squared tests or Fisher's exact tests were used to compare treatment groups for categorical variables. In univariate analyses of summary scores (SF-36), mean summary scores between 2 treatment groups were compared using two-sample t-tests, assuming equal variances except when the F-test for equality of variance had p value <0.05. Univariate analysis of summary scores of SF-36 on a potential predictor with two levels was performed using two-sample t-test; for predictors with more than two levels, F-test from linear regression was used. Multivariate linear regression models were used to examine the mean summary score from SF-36 between treatment groups with adjustment of other factors (sex, household income, presence of chronic health conditions) as covariates; the effect of a characteristic compared to the reference group, with adjustment for other covariates, was tested by Wald test. Based on previous literature, education, employment status and household income were considered potential confounders and thus were included in the analysis. Patients with missing values in the independent variable or missing values in the covariates for the multivariate analyses were excluded from the individual analysis. Two-sided analyses were used in all comparisons and a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. No multiple comparison adjustments were made.

RESULTS

Demographics

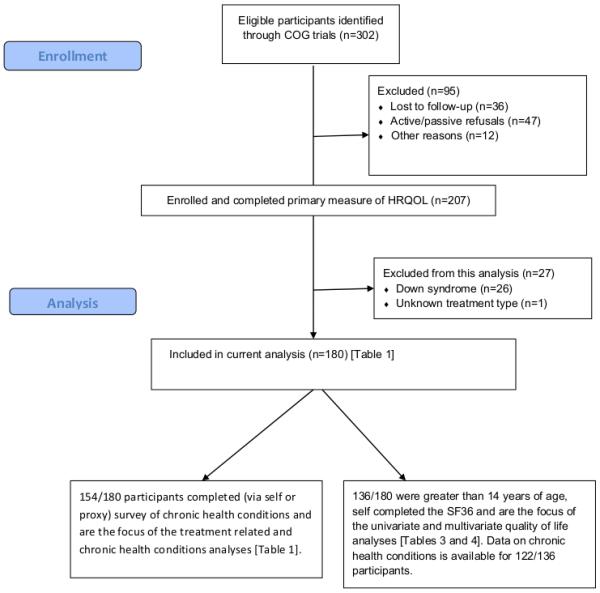

Of participants enrolled on the included treatment protocols and treated at participating institutions, 298 potentially eligible subjects were identified and contacted by the coordinating center (Supplemental Figure 1). Of these, 91 did not complete the interview (36 not located, 35 active refusals, 12 passive refusals, 2 unable to complete interview due to language barrier, 6 ineligible) resulting in a participation rate of 68.5%. Of the 207 patients who completed the interview, one patient lacked adequate treatment information for analysis and 26 patients had Down syndrome and were excluded from this analysis.

Of eligible participants, 180 survivors without Down syndrome completed an age appropriate measure of HRQOL and are the focus of the overall and chronic health conditions analyses (Tables 1). Of these, 100 underwent chemotherapy-only, 26 underwent autoBMT, and 54 underwent alloBMT. Most (88%) were white and 53% were female. Forty-five of the subjects enrolled in this study also participated in the CCSS and completed the baseline questionnaire as a part of that study. The remaining participants completed the CCSS questionnaire as a part of this study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Characteristics | All (N=180) | Chemotherapy only Patients (N=100) | AutoBMT Patients (N=26) | AlloBMT Patients (N=54) | P value$ (Chemo vs. autoBMT) | P value$ (Chemo vs. alloBMT) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment | ||||||

| Median (Range) in years | 20 (8 – 39) | 21 (8 – 39) | 13.5 (8 – 25) | 21.5 (8 – 38) | 0.0009* | 0.70* |

| Age at diagnosis of AML | ||||||

| Median (Range) in years | 4 (0 – 20) | 4 (0 – 19) | 3 (0 – 16) | 8 (0 – 20) | 0.93* | 0.008* |

| Time since diagnosis of AML | ||||||

| Median (Range) in years | 13.5 (6 – 22) | 15 (7 – 21) | 10 (7 – 13) | 12.5 (6 – 22) | <0.0001* | 0.01* |

| Gender | 0.58 | 0.35 | ||||

| Male | 85 (47%) | 44 (44%) | 13 (50%) | 28 (52%) | ||

| Female | 95 (53%) | 56 (56%) | 13 (50%) | 26 (48%) | ||

| Race | 0.95** | 0.87 | ||||

| White (Including Hispanic) | 159 (88%) | 88 (88%) | 23 (88%) | 48 (89%) | ||

| Others or Unknown | 21 (12%) | 12 (12%) | 3 (12%) | 6 (11%) | ||

| Treatment Protocol | ||||||

| CCG251 (1979–1983) | 43 (24%) | 29 (29%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (26%) | ||

| CCG213 (1985–1989) | 55 (31%) | 44 (44%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (20%) | ||

| CCG2861 (1988–1999) | 8 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (19%) | 3 (6%) | ||

| CCG2891 (1989–1995) | 74 (41%) | 27 (27%) | 21 (81%) | 26 (48%) | ||

| Education | 0.69 | 0.76 | ||||

| High school (not graduate) or less | 93 (55%) | 52 (57%) | 13 (52%) | 28 (54%) | ||

| High school (graduate) or some college | 76 (45%) | 40 (43%) | 12 (48%) | 24 (46%) | ||

| Current Employment status (age ≥25 years) | 1.00** | 1.00 | ||||

| Employed | 23 (49%) | 14 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (50%) | ||

| Not employed | 24 (51%) | 14 (50%) | 1 (100%) | 9 (50%) | ||

| Household income | 0.74 | 0.67 | ||||

| <$20,000 | 21 (14%) | 14 (16%) | 3 (16%) | 4 (10%) | ||

| $20,000–60,000 | 82 (56%) | 46 (53%) | 12 (63%) | 24 (59%) | ||

| ≥$60,000 | 44 (30%) | 27 (31%) | 4 (21%) | 13 (32%) | ||

| History of chronic GVHD (among alloBMT only) | ||||||

| Yes | 11 (28%) | |||||

| No | 28 (72%) | |||||

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 0.49 | 0.05 | ||||

| <18.5 | 29 (21%) | 15 (18%) | 1 (7%) | 13 (32%) | ||

| 18.5–24.9 | 74 (53%) | 44 (52%) | 7 (50%) | 23 (56%) | ||

| >25 | 36 (26%) | 25 (30%) | 6 (43%) | 5 (12%) | ||

| Any chronic health condition | 0.29 | 0.0006 | ||||

| Yes | 85 (55%) | 40 (44%) | 11 (58%) | 34 (76%) | ||

| No | 69 (45%) | 50 (56%) | 8 (42%) | 11 (24%) | ||

| Any severe chronic health condition | 0.51** | 0.02 | ||||

| Yes | 33 (21%) | 14 (16%) | 4 (21%) | 15 (33%) | ||

| No | 121 (79%) | 76 (84%) | 15 (79%) | 30 (67%) | ||

| ≥2 chronic health conditions | 0.89 | 0.004 | ||||

| Yes | 58 (38%) | 27 (30%) | 6 (32%) | 25 (56%) | ||

| No | 96 (62%) | 63 (70%) | 13 (68%) | 20 (44%) | ||

| ≥3 chronic health conditions | 0.73** | 0.005 | ||||

| Yes | 36 (23%) | 16 (18%) | 2 (11%) | 18 (40%) | ||

| No | 118 (77%) | 74 (82%) | 17 (89%) | 27 (60%) | ||

| Reports general health | 1.00** | 1.00** | ||||

| Excellent, very good or good | 144 (95%) | 84 (94%) | 18 (95%) | 42 (95%) | ||

| Fair or poor | 8 (5%) | 5 (6%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (5%) | ||

| Cancer-related pain | 0.07** | 1.00** | ||||

| Yes | 8 (5%) | 3 (4%) | 3 (16%) | 2 (5%) | ||

| No | 140 (95%) | 82 (96%) | 16 (84%) | 42 (95%) | ||

| Cancer-related anxiety | 0.72** | 0.80 | ||||

| Yes | 19 (13%) | 11 (13%) | 3 (16%) | 5 (11%) | ||

| No | 129 (87%) | 74 (87%) | 16 (84%) | 39 (89%) | ||

| Has health insurance | 1.00** | 0.77** | ||||

| Yes | 144 (94%) | 85 (94%) | 18 (95%) | 41 (93%) | ||

| No | 9 (6%) | 5 (6%) | 1 (5%) | 3 (7%) | ||

| Relapse | 0.75** | 0.75 | ||||

| Yes | 25 (14%) | 13 (13%) | 4 (15%) | 8 (15%) | ||

| No | 155 (86%) | 87 (87%) | 22 (85%) | 46 (85%) | ||

| TBI (among alloBMT only) | ||||||

| Yes | 25 (46%) | |||||

| No | 29 (54%) |

Based on Chi-square test except specified otherwise;

Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test;

Fisher's Exact Test

Among participants, chemotherapy-only recipients and alloBMT recipients were similar in age at the time of interview (chemotherapy-only: median 21 years, range 8–39; alloBMT: median 21.5, range 8–38), but recipients of autoBMT were younger (median 13.5 years, range 8–25). This was expected based on the calendar years during which autoBMT was used in legacy COG protocols. Those who underwent alloBMT were older at the time of diagnosis compared to those who underwent chemotherapy-only (8 years vs. 4 years, p=0.008), as would be expected based on the availability of a matched related donor. Recipients of chemotherapy-only, autoBMT, and alloBMT were similar with regard to education, employment and household income.

Chronic health conditions

Overall, slightly more than half (55%) of participants reported at least one chronic health condition (Table 1). Chronic health conditions were significantly more common among recipients of alloBMT (alloBMT 76%, autoBMT 58%, chemotherapy-only 44%; p=0.0006 for chemotherapy-only vs. alloBMT; p=0.29 for chemotherapy-only vs. autoBMT). Twice as many alloBMT as chemotherapy-only survivors reported at least one severe chronic health condition (33% vs. 16%, p=0.02). AlloBMT survivors were also more likely to have 2 or more chronic health conditions (56% alloBMT vs. 30% chemotherapy-only p=0.004). Body mass index also varied by treatment group with 32% of alloBMT recipients reporting BMI < 18.5.

Although chronic health conditions were considerably more common among alloBMT recipients, participants in each treatment group were equally likely (94–95%) to report their general health as excellent, very good, or good vs. fair or poor (Table 1). In addition, alloBMT recipients were no more likely to report cancer-related pain or cancer-related anxiety and were equally likely to report employment and having health insurance as those in other treatment groups (Table 1). Fourteen percent of survivors experienced a relapse; this did not vary by treatment group. Twenty-eight percent of subjects who underwent alloBMT had a history of cGVHD, as documented by COG follow-up records.

Commonly-reported chronic health conditions included decreased sense of touch (n=17, grade 1), cataracts (n=16, grade 1) and hypothyroidism (n=11, grade 2). Grades 3 or 4 (severe or life-threatening) chronic conditions were reported in 21% of survivors; one-third of these reports were of ovarian failure. Twice as many reports of ovarian failure were noted in the alloBMT group than in other treatment groups. Nine survivors were considered legally blind, 5 in the chemotherapy only group and 4 in the alloBMT group. No secondary malignant neoplasms were reported in any survivors. The estimated 15-year cumulative incidence of chronic health conditions was 48.1% for any chronic health condition and 21.3% for severe chronic health conditions.

HRQOL results

One hundred thirty-six participants were at least 14 years of age and self-completed the SF-36 and are the focus of the HRQOL analyses.

To determine if enrollment bias affected our HRQOL results, participants >14 years of age who completed the SF-36 were compared with those among the 302 selected patients that were alive and > 14 years of age but did not complete the interview (Table 2). No socioeconomic indicators were available for non-participants. No significant differences in available demographic variables were revealed except a higher proportion of participants are white than non-participants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of study participants ≥14 years of age who completed SF-36 vs. eligible non-participants not enrolled in the current study

| Characteristics | SF-36 (N=136) | Non-participants (n=72) | P value$ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment of L9704 | |||

| Median (Range) in years | 22 (14–39) | 23 (14–38) | 0.61* |

| Age at diagnosis of AML | |||

| Median (Range) in years | 9 (0–20) | 10 (0–19) | 0.79* |

| Time since diagnosis of AML | |||

| Median (Range) in years | 16 (6–22) | 14 (6–21) | 0.19* |

| Gender | 0.66 | ||

| Male | 60 (44%) | 35 (49%) | |

| Female | 76 (56%) | 37 (51%) | |

| Race | 0.008 | ||

| White (Including Hispanic) | 121 (89%) | 53 (74%) | |

| Others or Unknown | 15 (11%) | 19 (26%) | |

| Treatment Protocol | 0.58** | ||

| CCG251 (1979–1983) | 42 (31%) | 21 (29%) | |

| CCG213 (1985–1989) | 55 (40%) | 24 (33%) | |

| CCG2861 (1988–1999) | 5 (4%) | 4 (6%) | |

| CCG2891 (1989–1995) | 34 (25%) | 23 (32%) | |

| History of chronic GVHD (among alloBMT only) | 0.89 | ||

| Yes | 9 (33%) | 5 (42%) | |

| No | 18 (67%) | 7 (58%) | |

| Relapse | 0.88 | ||

| Yes | 17 (12.5%) | 8 (12%) | |

| No | 119 (87.5%) | 58 (88%) | |

| TBI (among alloBMT only) | 0.84 | ||

| Yes | 25 (61%) | 10 (62.5%) | |

| No | 16 (39%) | 6 (37.5%) |

Based on Chi-square test except specified otherwise

Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test

Fisher's Exact Test

In unadjusted analyses, chemotherapy-only, autoBMT, and alloBMT recipients had similar mean SF-36 mental/psychosocial summary scores. AlloBMT survivors who completed the SF-36 scored lower on the physical summary scale (49.1 vs. 52.2; p=0.03), suggesting worse physical functioning than those who underwent chemotherapy-only. None of the subscale differences reached statistical significance.

Univariate (Table 3) and multivariate (Table 4) analyses were restricted to participants 14 years of age and older who self-completed the SF-36. In the univariate analysis, females scored worse in both physical and mental domains. Age at diagnosis, age at interview, education and household income were not significant predictors of HRQOL. Non-white ethnicity was associated with a higher physical mean summary score indicating better function (54.8 vs. 50.6; p=0.006). Those with cancer-related pain reported lower physical mean summary scores (41.2 vs. 51.7; p=0.05). Cancer-related anxiety was associated with a lower mental mean summary score (46.8 vs. 52.1; p=0.04). In an analysis restricted to alloBMT recipients, those who received TBI had similar physical and mental mean summary scores compared to those who did not (physical 48.6 vs. 49.8; p=0.65 and mental 49.8 vs. 54.3; p=0.10).

Table 3.

Univariate mean HRQOL (SF-36) scores for patients ≥14 years of age by potential predictor characteristics

| Potential Predictors | Physical summary score Mean (SD) | P value | Mental summary score Mean (SD) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.04 | 0.03 | ||

| Female (n=76) | 49.9 (6.9) | 49.4 (11.8) | ||

| Male (n=60) | 52.5 (7.9) | 53.1 (8.1) | ||

| Age at interview | 0.19 | 0.81 | ||

| 14–25 (n=88) | 51.7 (6.7) | 51.2 (10.2) | ||

| ≥25 (n=48) | 49.9 (8.6) | 50.7 (11.1) | ||

| Age at diagnosis | 0.27 | 0.29 | ||

| <10 (n=71) | 51.8 (6.8) | 50.1 (11.0) | ||

| ≥10 (n=65) | 50.3 (8.1) | 52.0 (9.9) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.006 | 0.77 | ||

| White (including Hispanic) (n=121) | 50.6 (7.6) | 51.1 (10.6) | ||

| Non-white (n=15) | 54.8 (4.6) | 50.3 (9.4) | ||

| Education | 0.79 | 0.46 | ||

| High school (not graduate) or less (n=69) | 51.2 (7.7) | 50.4 (10.6) | ||

| High school (graduate) or some college (n=57) | 50.9 (7.4) | 51.8 (9.9) | ||

| Household income | 0.28 | 0.32 | ||

| <$20,000 (n=20) | 51.5 (7.0) | 48.5 (14.0) | ||

| $20,000–60,000 (n=64) | 51.5 (6.1) | 52.2 (8.8) | ||

| ≥$60,000 (n=32) | 48.9 (10.2) | 51.9 (7.7) | ||

| Employment status (age≥25) | 0.57 | 0.38 | ||

| Ever Employed (n=24) | 49.6 (8.7) | 50.2 (10.1) | ||

| Never employed (n=23) | 51.0 (8.3) | 52.7 (10.0) | ||

| Current employment status (age≥25) | 0.81 | 0.77 | ||

| Employed (n=23) | 49.9 (8.7) | 51.0 (9.5) | ||

| Not employed (n=24) | 50.5 (8.3) | 51.9 (10.7) | ||

| Has health insurance | 0.38 | 0.79 | ||

| Yes (n=112) | 50.7 (7.7) | 51.3 (9.8) | ||

| No (n=9) | 53.0 (5.6) | 52.2 (9.0) | ||

| BMI | 0.56 | 0.49 | ||

| <18.5 (n=16) | 51.2 (5.8) | 48.0 (10.7) | ||

| 18.5–24.9 (n=64) | 51.3 (8.2) | 51.1 (9.8) | ||

| >25 (n=33) | 49.5 (7.7) | 51.5 (10.7) | ||

| Any chronic health condition | 0.0009 | 0.10 | ||

| Yes (n=68) | 49.0 (8.7) | 49.9 (11.2) | ||

| No (n=54) | 53.3 (4.8) | 52.7 (7.8) | ||

| Any severe chronic health condition | 0.006 | 0.19 | ||

| Yes (n=30) | 46.5 (10.4) | 49.1 (11.9) | ||

| No (N=92) | 52.3 (5.6) | 51.8 (9.1) | ||

| Two or more chronic health conditions | 0.01 | 0.08 | ||

| Yes (n=47) | 48.5 (9.6) | 49.0 (12.2) | ||

| No (n=75) | 52.4 (5.3) | 52.5 (7.9) | ||

| Three or more chronic health conditions | 0.001 | 0.17 | ||

| Yes (n=30) | 45.9 (9.6) | 48.6 (12.4) | ||

| No (n=92) | 52.5 (5.9) | 52.0 (8.8) | ||

| Reports general health | 0.09 | 0.25 | ||

| Excellent, very good or good (n=113) | 51.4 (6.7) | 52.0 (8.8) | ||

| Fair or poor (n=7) | 41.5 (13.0) | 43.8 (16.7) | ||

| Cancer-related pain | 0.05 | 0.58 | ||

| Yes (n=8) | 41.2 (12.8) | 53.4 (9.2) | ||

| No (n=109) | 51.7 (6.5) | 51.5 (9.5) | ||

| Cancer-related anxiety | 0.15 | 0.04 | ||

| Yes (n=15) | 47.0 (11.1) | 46.8 (11.5) | ||

| No (n=103) | 51.6 (6.7) | 52.1 (9.1) | ||

| TBI (among alloBMT patients only) | ||||

| Yes (n=25) | 48.6 (8.1) | 0.65 | 49.8 | 0.10 |

| No (n=16) | 49.8 (7.1) | 54.3 |

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of quality of life scores from SF-36 by potential predictor characteristics

| Potential Predictors | Estimated difference (SE) in physical summary score | P value | Estimated difference (SE) in mental summary score | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | ||||

| Chemotherapy-only | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| AlloBMT | −1.51 (1.56) | 0.34 | 1.80 (2.09) | 0.39 |

| AutoBMT | −3.39 (2.55) | 0.19 | 5.09 (3.41) | 0.14 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| Female | −1.84 (1.39) | 0.19 | −1.86 (1.85) | 0.32 |

| Household income | ||||

| <$20,000 | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| $20,000–60,000 | −0.32 (1.85) | 0.86 | 3.35 (2.47) | 0.18 |

| ≥60,000 | −2.43 (2.05) | 0.24 | 3.45 (2.74) | 0.21 |

| Any severe chronic health condition | ||||

| Yes | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| No | 4.82 (1.66) | 0.004 | 2.06 (2.21) | 0.36 |

Chronic health conditions were associated with diminished HRQOL as measured by the physical mean summary score (Table 3). Those with any chronic health condition reported a physical mean summary score of 49.0 compared with 53.3 among those without a chronic health condition (p=0.0009). The presence of at least one severe (grade 3 or 4) chronic health condition was associated with a poorer physical mean summary score (46.5 vs. 52.3; p=0.006) as was the presence of two or more chronic health conditions (48.5 vs. 52.4; p=0.01).

In the multivariate analysis used to assess the role of treatment, gender, household income and chronic health conditions, only the presence of a severe chronic health condition was associated with a diminished physical mean summary score (Table 4). Participants without a severe chronic health condition had an estimated difference of 4.82 in the physical mean summary score, suggesting a clinically significant increase in physical functioning compared to participants with a severe chronic health condition but the same treatment, gender, and household income (p=0.004). Treatment type, gender and household income were not significant independent predictors for physical or mental mean summary scores in the adjusted analysis.

In a univariate analysis restricted to alloBMT survivors, cGVHD was associated with a lower mental mean summary score (54.0 vs. 44.7; p=0.03) but not a lower physical mean summary score. This difference was not significant in the multivariate analysis. Among alloBMTsurvivors, the presence of a severe chronic health condition was associated with a lower physical mean summary score (p=0.04).

DISCUSSION

We studied the prevalence of chronic health conditions and health-related quality of life in survivors of childhood and adolescent AML treated with chemotherapy-only, autoBMT, or alloBMT on one of four legacy COG clinical trials. In aggregate, HRQOL varied little among these therapeutic groups. Multivariate analysis did not reveal any effect of therapeutic group on HRQOL. Among these patients, 55% reported a chronic health condition and 21% reported a severe chronic health condition. The presence of chronic health conditions was predictive of HRQOL. Despite the prevalence of chronic health conditions, nearly all survivors reported their health as excellent, very good or good. Very few reported cancer-related pain or anxiety.

Mulrooney et al. found a high prevalence of chronic health conditions in survivors of AML who received chemotherapy-only.[7] In that analysis, 50% of survivors reported a chronic health condition compared with 38% of their siblings; 16% reported a severe chronic health condition compared with 6% of siblings. Endocrine and cardiovascular late effects were most common.[7] Our data on chronic health condition are similar to those reported in the overall CCSS cohort (Diller et al 2009) although the cumulative incidence of chronic health conditions in this young and intensively-treated population may increase with time.

Among these AML survivors HRQOL scores were similar to scores in healthy populations (mean = 50). Meeske et al.[20] have reported similar findings, noting that HRQOL scores for pediatric cancer survivors attending a long-term follow-up clinic were similar to scores reported for healthy children. Subgroups at higher risk included those with brain tumors and those with fatigue, pain or more severe late effects.[20] Another study assessed the quality of life of survivors 15 to 37 years of age using the SF-36 self-report instrument and noted that fewer survivors than population controls reported good or excellent general health (adjusted odds ratio 0.61; 95% CI: 0.51, 0.71), and that survivors had lower physical mean summary scores than controls. [21]

Our results for alloBMT survivors are similar to those noted in a study of HRQOL in survivors of hematopoietic cell transplant performed for multiple indications.[22] In this study, survivors treated for AML had poorer outcomes on the SF-36 physical summary score than did survivors who had received transplantation for other malignancies or hematological disorders.[22] Our results and these reports suggest that late complications and diminished physical functioning may be problematic for AML survivors following BMT.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study include our long-term follow-up of a large cohort of AML survivors assigned to alloBMT by virtue of having a matched related donor or assigned to autoBMT or additional chemotherapy if no matched related donor was available. Data include detailed and reliable treatment information, age-appropriate and validated measures of HRQOL, and current medical and psychosocial information. Chronic health conditions were scored using previously-described methodologies for comparisons to other cohorts and better reproducibility. This paper contributes to the understanding of late effects faced by survivors of alloBMT and extends those results to include the impact of such treatment on their quality of life. AlloBMT is one of the most intensive therapies used to treat childhood cancer. This study attempts to illuminate the extent and intensity of these late effects of treatment for AML. Although these therapeutic protocols were administered up to 30 years ago, the chemotherapy and BMT regimens are similar to those used today, thus our results are relevant to current patients, families and treating physicians.

Limitations of our study include the difficulty of comparing results between age groups, leading to smaller subgroups for analysis. We have not adjusted for multiple comparisons. In addition, due to the small number of non-white participants in the cohort, we are unable to fully ascertain the effects of race/ethnicity on HRQOL or the prevalence of chronic health conditions in larger non-white groups.

Also, in this as in many studies, available datasets did not adequately capture if any survivors who relapsed later underwent either matched sibling donor or alternative donor alloBMT. Thus, this study best assesses quality of life and chronic health conditions by initial treatment group with limited data on later transplantation for late recurrence. As this is expected to have occurred only rarely within this set of survivors, the effect of this limitation on the conclusions is expected to be small.

In any study of HRQOL, ascertainment bias is a potential concern. Those survivors with diminished HRQOL may have been less likely to participate. To assess for this, we compared our largest population (those >14 years of age who completed the SF-36) to non-participating children treated on identical protocols and found no differences in available variables.

We systematically assessed HRQOL in adolescent and adult survivors of childhood AML who underwent chemotherapy-only, autoBMT or alloBMT. We found that overall scores on the physical and mental health summary scales of the SF-36 were similar between treatment groups, although survivors with more chronic health conditions or with cancer-related pain had diminished HRQOL as measured by the physical mean summary scores. Many of the chronic health conditions may be related to the intensity of treatment for AML. This study highlights the ongoing challenge to move toward increasingly efficacious therapies while minimizing chronic toxicities. Management of cancer-related pain in AML survivors also merits careful attention.

We hope this analysis of multidisciplinary outcomes following therapy for childhood AML will lead to the development of interventions both during and after therapy to reduce the presence of chronic health conditions, help survivors cope with chronic health conditions and optimize their quality of life. Future studies will assess how wellness interventions and psychosocial support during the treatment period might affect long-term quality-of-life outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Enrollment and analysis flow

Acknowledgements

We thank Michelle Roesler, Cynthia Ford and Jan Sheaffer for their assistance in manuscript preparation. We thank Children's Cancer Research Fund, Children's Oncology Group and the National Cancer Institute (U24CA55727, 5U10 CA07306 and 1R01CA78960), and the participating survivors and their families for their support of this research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare no affiliations with any organization that has a direct interest in the subject matter contained herein. They have no conflicting financial interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Redaelli A, Stephens JM, Brandt S, et al. Short- and long-term effects of acute myeloid leukemia on patient health-related quality of life. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30:103–117. doi: 10.1016/S0305-7372(03)00142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nesbit ME, Jr, Woods WG. Therapy of acute myeloid leukemia in children. Leukemia. 1992;6(Suppl 2):31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonzo TA, Wells RJ, Woods WG, et al. Postremission therapy for children with acute myeloid leukemia: The children's cancer group experience in the transplant era. Leukemia. 2005;19:965–970. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith FO, Alonzo TA, Gerbing RB, et al. Long-term results of children with acute myeloid leukemia: A report of three consecutive phase III trials by the Children's Cancer Group: CCG 251, CCG 213 and CCG 2891. Leukemia. 2005;19:2054–2062. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hale GA, Tong X, Benaim E, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in children failing prior autologous bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27:155–162. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leung W, Hudson MM, Strickland DK, et al. Late effects of treatment in survivors of childhood acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3273–3279. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.18.3273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulrooney DA, Dover DC, Li S, et al. Twenty years of follow-up among survivors of childhood and young adult acute myeloid leukemia: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2008;112:2071–2079. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molgaard-Hansen L, Glosli H, Jahnukainen K, et al. Quality of health in survivors of childhood acute myeloid leukemia treated with chemotherapy only: A NOPHO-AML study. Pediatr Blood & Cancer. 2011;57:1222–1229. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells RJ, Woods WG, Buckley JD, et al. Treatment of newly diagnosed children and adolescents with acute myeloid leukemia: A Children's Cancer Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:2367–2377. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.11.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wells RJ, Woods WG, Lampkin BC, et al. Impact of high-dose cytarabine and asparaginase intensification on childhood acute myeloid leukemia: A report from the Children's Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:538–545. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nesbit ME, Jr, Buckley JD, Feig SA, et al. Chemotherapy for induction of remission of childhood acute myeloid leukemia followed by marrow transplantation or multiagent chemotherapy: A report from the Children's Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:127–135. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woods WG, Kobrinsky N, Buckley JD, et al. Timed-sequential induction therapy improves postremission outcome in acute myeloid leukemia: A report from the Children's Cancer Group. Blood. 1996;87:4979–4989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woods WG, Neudorf S, Gold S, et al. A comparison of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, autologous bone marrow transplantation, and aggressive chemotherapy in children with acute myeloid leukemia in remission. Blood. 2001;97:56–62. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woods WG, Kobrinsky N, Buckley J, et al. Intensively timed induction therapy followed by autologous or allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for children with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome: A Childrens Cancer Group pilot study. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1448–1457. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.8.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robison LL. The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: A resource for research of long-term outcomes among adult survivors of childhood cancer. Minn Med. 2005;88:45–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robison LL, Green DM, Hudson M, et al. Long-term outcomes of adult survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer. 2005;104:2557–2564. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD, et al. Study design and cohort characteristics of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: A multi-institutional collaborative project. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38:229–239. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Karvouni A, Kouri I, Ioannidis JP. Reporting and interpretation of SF-36 outcomes in randomised trials: Systematic review. BMJ. 2009;338:a3006. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meeske KA, Patel SK, Palmer SN, et al. Factors associated with health-related quality of life in pediatric cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:298–305. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maunsell E, Pogany L, Barrera M, et al. Quality of life among long-term adolescent and adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2527–2535. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.9297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanders JE, Hoffmeister PA, Storer BE, et al. The quality of life of adult survivors of childhood hematopoietic cell transplant. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:746–754. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.