Summary

Our intestinal microbiota harbors a diverse microbial community, often containing opportunistic bacteria with virulence potential. However, mutualistic host-microbial interactions prevent disease by opportunistic pathogens through poorly understood mechanisms. We show that the epithelial interleukin-22 receptor IL-22RA1 protects against lethal Citrobacter rodentium infection and chemical-induced colitis by promoting colonization resistance against an intestinal opportunistic bacterium, Enterococcus faecalis. Susceptibility of Il22ra1−/− mice to C. rodentium was associated with preferential expansion and epithelial translocation of pathogenic E. faecalis during severe microbial dysbiosis and was ameloriated with antibiotics active against E. faecalis. RNA sequencing analyses of primary colonic organoids showed that IL-22RA1 signaling promotes intestinal fucosylation via induction of the fucosyltransferase Fut2. Additionally, administration of fucosylated oligosaccharides to C. rodentium-challenged Il22ra1−/− mice attenuated infection and promoted E. faecalis colonization resistance by restoring the diversity of anaerobic commensal symbionts. These results support a model whereby IL-22RA1 enhances host-microbiota mutualism to limit detrimental overcolonization by opportunistic pathogens.

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Il22ra1−/− mice succumb to enterococcal dissemination during C. rodentium infection

-

•

E. faecalis expands during C. rodentium-induced dysbiosis and invades epithelial cells

-

•

Organoid IL-22RA1 RNA-seq reveals diverse antimicrobial and glycosylation factors

-

•

Intestinal fucosylation enhances colonization resistance to E. faecalis

Host-commensal interactions prevent disease by opportunistic pathogens through poorly understood mechanisms. Pham et al. show that IL-22RA1 signaling can control the mucosal proliferation and subsequent epithelial translocation of an opportunistic pathogen by promoting intestinal fucosylation and thus enhancing beneficial nutrient interactions between the epithelium and commensal microbes.

Introduction

The mammalian gastrointestinal tract harbors a dense and diverse microbial community that is essential for host nutrient acquisition, immune development, and pathogen defense. In health, the microbiota consists mainly of obligate anaerobes and can act as an effective barrier to prevent colonization and access of pathogenic microbes to host tissues. Colonization resistance to enteric pathogens is thought to involve mutualistic interactions between the host immune system and the commensal microbiota through mechanisms that remain poorly understood. Moreover, while many host-commensal associations are considered symbiotic, the microbiota also contains indigenous opportunistic microbes, which can potentially trigger intestinal or systemic pathology particularly during perturbations of the intestinal ecosystem (Stecher and Hardt, 2008). In most healthy individuals, however, these opportunistic pathogens fail to replicate to sufficient levels to colonize the mucosal surface or to invade the host systemic organs, suggesting the importance of mechanisms to restrict their overcolonization and virulence expression.

Interleukin-22 (IL-22) is an important cytokine for maintaining homeostasis at various mucosal barriers, including the gastrointestinal tract (Sonnenberg et al., 2011). During infection with enteropathogens such as Salmonella Typhimurium and Citrobacter rodentium, IL-22 is highly upregulated, leading to induction of multiple antimicrobial and inflammatory factors (Raffatellu et al., 2008; Zheng et al., 2008). The protective function of IL-22 is evident by the observations that Il22−/− mice are susceptible to Gram-negative pathogens, including C. rodentium and Klebsiella pneumoniae (Aujla et al., 2008; Zheng et al., 2008). In contrast, IL-22 deficiency is not associated with enhanced susceptibility to Neisseria gonorrhoea, Listeria monocytogenes, or the pathogenic protozoan Toxoplasma gondii (Feinen and Russell, 2012; Graham et al., 2011; Wilson et al., 2010), and IL-22 can even promote S. Typhimurium colonization (Behnsen et al., 2014). These findings suggest that the effects of IL-22 on pathogen colonization resistance are highly complex and varied depending on the inflammatory stimuli and the indigenous microbiota.

IL-22 signals through a heterodimeric receptor complex consisting of a ubiquitously expressed IL-10Rβ subunit and an IL-22RA1 subunit, which has a remarkably tissue-specific distribution. IL-22RA1 expression is limited to a few organs (e.g., liver, kidney) and barrier surfaces such as the skin and gastrointestinal tract, where it is thought to mediate the effects of IL-22 in maintaining barrier homeostasis (Wolk et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2008). Given the complex antimicrobial function of IL-22, in the present study we set out to elucidate the impact of IL-22RA1 on the resident microbiota and the maintenance of pathogen colonization resistance.

Results

IL-22RA1 Limits Systemic Bacterial Dissemination during Intestinal Inflammation

We generated Il22ra1−/− mice homozygous for the targeted Il22ra1tm1a(KOMP)Wtsi allele (Skarnes et al., 2011) and confirmed that within the gastrointestinal tract, endogenous Il22ra1 expression is restricted to the epithelium (Figures S1A and S1B, available online). By a global phenotyping approach (White et al., 2013), we found no obvious systemic or intestinal pathology in specific pathogen-free (SPF) Il22ra1−/− mice (Figures S1C–S1E). 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing revealed no significant difference in the diversity and community structure of the baseline microbiota between wild-type (WT) and Il22ra1−/− mice (Figures S1F and S1G). Next, we infected Il22ra1−/− mice with pathogens to discern the role of IL-22RA1 in systemic and intestinal host defenses. IL-22RA1 is not required for protection against systemic Salmonella Typhimurium, as all Il22ra1−/− mice survived intravenous Salmonella infection and were able to clear the bacteria in a manner similar to that of WT mice (Figures S2A–S2C). By contrast, similarly to Il22−/− mice (Zheng et al., 2008), Il22ra1−/− mice were highly susceptible to the attaching-effacing enteropathogen C. rodentium (Figures S2D and S2E).

We next examined the impact of IL-22RA1 on mucosal immunity to C. rodentium. Infected Il22ra1−/− mice had significantly higher transcript and protein expression of proinflammatory Th1-type cytokines (interferon gamma [IFNγ], IL-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α]) and Th17-type cytokines (IL-17a, IL-17f, IL-21, IL-22) in the cecal tissues and isolated colonic lamina propria (cLP) leukocytes (Figure S3A). This is consistent with an ∼3-fold accumulation of IFNγ- and IL-17a-producing CD4+ T cells in the cLP of infected Il22ra1−/− mice (Figures S3B–S3D), whereas B cells, Foxp3+ regulatory T cells, neutrophils, and inflammatory macrophages were at frequencies similar to that of WT (Figures S3E and S3F). We also detected similar titers of total and Citrobacter-specific immunoglobulin A (IgA) in the intestine of Il22ra1−/− mice compared to WT mice at day 9 postinfection (p.i.) (Figure S3G). Thus, susceptibility of Il22ra1−/− mice to C. rodentium is not associated with an insufficient mucosal immune response.

Notably, infected Il22ra1−/− mice showed a high systemic burden of C. rodentium, accompanied by elevated serum titers of Citrobacter-specific IgG (Figures 1A and 1B). Furthermore, serum levels of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α were significantly increased (Figure 1C), suggesting dissemination of gut bacteria and systemic inflammation. To characterize this microbial dissemination, we performed nonselective, unbiased aerobic and anaerobic culturing together with 16S rRNA sequencing to identify bacterial isolates from the systemic organs. Interestingly in addition to C. rodentium, we identified substantial and consistent breakthrough of Enterococcus faecalis—a normal commensal of the mouse and human microbiota (Figures 1D and 1E and Table S1). Dissemination of E. faecalis was detectable from day 5 p.i., and at day 9 the systemic burden of E. faecalis was comparable to that of C. rodentium among infected Il22ra1−/− mice (Figures 1D and 1E and Table S1). Importantly, E. faecalis was not recovered from the organs of infected WT mice (Table S1) or of infected Il22ra1−/− mice without signs of morbidity (data not shown).

Figure 1.

IL-22RA1 Limits Systemic Bacterial Dissemination during Intestinal Disease

(A) C. rodentium cfus in systemic organs.

(B) Serum anti-C. rodentium EspA IgG titer.

(C and D) TNF-α and IL-6 cytokines (C) and E. faecalis cfus (D) in systemic organs of infected WT and Il22ra1−/− mice. Shown are mean ± SEM in five independent infections (n = 4–6 each); ∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

(E and F) Profile of systemic bacterial isolates from (E) WT (n = 10) and Il22ra1−/− mice infected with C. rodentium (n = 28) and (F) DSS-treated WT and Il22ra1−/− mice (n = 8–10). Numbers indicate total number of isolates assigned to a particular bacterial taxon in 3–8 independent experiments. See also Figure S2 and Tables S1 and S2.

We further examined the dissemination of enterococci in Il22ra1−/− mice using a noninfectious model of intestinal inflammation, which involves treatment with dextran sodium sulfate (DSS). DSS-treated Il22ra1−/− mice showed significantly higher weight loss and susceptibility compared to WT littermates (Figures S2F and S2G). Similarly to the C. rodentium infection model, we noted a high E. faecalis bacterial load in the livers and spleens of DSS-treated Il22ra1−/− mice (Figure 1F and Table S2). Our data suggest that IL-22RA1 plays a role in controlling the systemic dissemination of intestinal bacteria, particularly a potential opportunistic E. faecalis species, during infectious and noninfectious intestinal injuries.

An Opportunistic E. faecalis Species Displays In Vivo and Genetic Virulence Potential

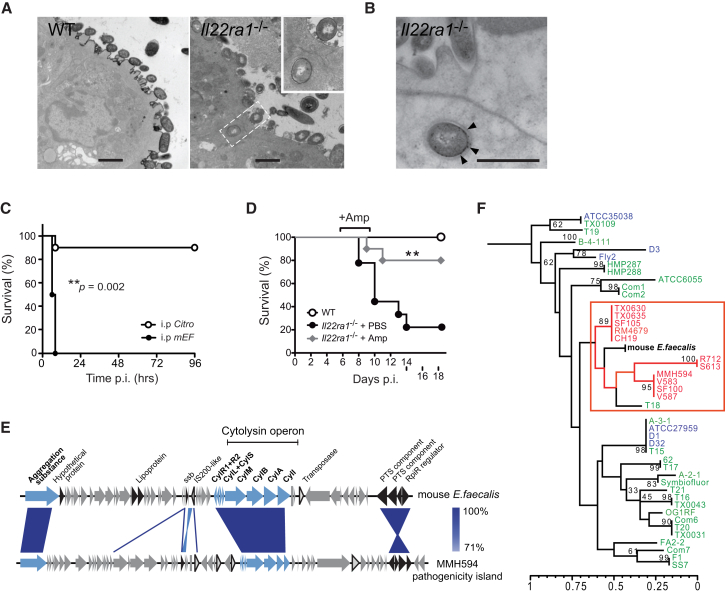

To examine the process of enterococcal dissemination from the gut of Il22ra1−/− mice, we performed transmission electron microscopy and immunogold labeling to identify bacteria at the intestinal mucosa during C. rodentium infection. At day 9 p.i., enterococci were found in contact with the epithelial surface of Il22ra1−/− mice and within membrane-bound compartments of enterocytes (Figures 2A and 2B). By contrast, C. rodentium-infected WT mice showed no epithelial association or invasion of E. faecalis (Figure 2A). This result suggests that E. faecalis can directly invade the intestinal epithelium of Il22ra1−/− mice during inflammation.

Figure 2.

A Pathogenic Enterococcus faecalis Isolate Harbors Virulence Factors, Translocates Intracellularly in Il22ra1-Deficient Mice, and Causes Lethal Septicemia

(A) Transmission electron micrographs of C. rodentium-infected WT and Il22ra1−/− mice cecal tissues, showing translocation of a coccal bacterium.

(B) Enterococcus-specific immunogold labeling (arrows) of an intracellular bacterium. Scale bar, 500 nm.

(C) Survival of WT mice infected i.p. with either C. rodentium or E. faecalis (n = 10–12).

(D) Survival C. rodentium-infected WT mice and Il22ra1−/− mice given i.p. ampicillin or PBS. Log-rank p value of two independent experiments (n = 5 each).

(E) Schematic alignment of the cytolysin operon and flanking genes of mEF and the E. faecalis pathogenicity island. Blue, cytolysin and aggregation substance; black, other pathogenicity island-associated genes; triangles, transposase and IS elements. rpiR, family transcriptional regulator; PTS, phosphotransferase system; CylI, cytolysin immunity protein; CylA, cytolysin activator; CylB, cytolysin B ABC-type transporter; CylM, cytolysin subunit modifier; CylL+S, cytolysin subunits L–S; CylR1+R2, cytolysin regulators R1 and R2.

(F) MLST-based phylogenetic relationship between mEF and nosocomial (red), community/probiotic (green), and animal (blue) E. faecalis strains. See also Figure S4 and Table S3.

Next, we determined the systemic virulence of the E. faecalis species recovered from Il22ra1−/− mice (termed mEF) in vivo, using a previously established enterococcal peritonitis model (Bourgogne et al., 2008). Intraperitoneal administration of mEF led to a higher mortality rate and a greater systemic inflammatory response (characterized by elevated serum IL-6 and TNF-α levels) compared to equivalent administration of C. rodentium (Figures 2C and S4A). This finding led us to determine the relative contribution of enterococci to the susceptibility of Il22ra1−/− mice to C. rodentium infection by administering clinically relevant doses of ampicillin intraperitoneally from day 5 p.i. Ampicillin is an antibiotic commonly used for enterococcal septicemia in humans and is active against mEF (minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC] = 1.6 μg/ml), but not C. rodentium (MIC > 125 μg/ml). Ampicillin-treated Il22ra1−/− mice showed substantially less weight loss and improved survival, associated with decreased intestinal colonization and systemic dissemination of E. faecalis (Figures 2D, S4B, and S4C), despite no alteration in the colonization levels of C. rodentium (Figure S4D). This suggests that dissemination of opportunistic E. faecalis can contribute to the susceptibility of Il22ra1−/− mice.

The ability of human pathogenic E. faecalis isolates to cause infections has been shown to involve virulence genes that enhance host colonization and adherence (Jett et al., 1994). We sequenced and annotated the complete mEF genome by comparative analysis with the previously sequenced E. faecalis pathogenicity island (Shankar et al., 2002) and the genome of E. faecalis V583, a hospital outbreak isolate (Figure S4E) (Paulsen et al., 2003). Interestingly, we identified multiple virulence factors implicated in the pathogenesis of invasive enterococcal infections (Figure S4E and Table S3). Notably, the mEF genome includes a chromosome-encoded cytolysin operon (Figures 2E and S4E), which encodes a membrane-targeting toxin often expressed by nosocomial E. faecalis isolates (Huycke et al., 1991). Next, using the multilocus sequence typing (MLST) of previously sequenced E. faecalis isolates from diverse human and animal origins (McBride et al., 2007), we assessed the genetic relatedness of mEF to 43 representative commensal and pathogenic E. faecalis strains (Table S4A). This analysis revealed a close phylogenetic relationship between mEF and several hospital-associated strains, including E. faecalis V583 (Figure 2F). Taken together, our results suggest that a genetically distinct E. faecalis species in Il22ra1−/− mice possesses the genetic virulence potential to cause systemic infection.

IL-22RA1 Restricts Expansion of Opportunistic E. faecalis during Intestinal Dysbiosis

Microbial dysbiosis often occurs during intestinal inflammation and can potentially impair colonization resistance to pathogens (Stecher and Hardt, 2011). We hypothesized that during C. rodentium-induced dysbiosis, IL-22RA1 could prevent dissemination of E. faecalis by restricting its intestinal overgrowth. By 16S rRNA pyrosequencing, we analyzed the microbiota composition of WT and Il22ra1−/− mice during infection. While the microbiota of WT and Il22ra1−/− mice were similarly diverse at baseline, C. rodentium infection resulted in a global reduction of species richness and diversity (shown by the Shannon index and rarefaction curves) that was significantly exacerbated in Il22ra1−/− mice (Figures 3A and S5A). Clustering analysis further showed that the microbial community structure of WT and Il22ra1−/− mice underwent distinct shifts during infection (Figure 3B). Unlike WT equivalents, the microbiota of infected Il22ra1−/− mice was characterized by a much higher population of C. rodentium (54% ± 34.9% compared to 11.4% ± 7.3% in WT controls; p value < 10−7) and severe depletion of the health-associated Lactobacillaceae, Bifidobacteriaceae, and Ruminococcaceae families (Figures 3B and S5B). Notably, all infected Il22ra1−/− mice displayed a clear and consistent overgrowth of Enterococcus spp., which was not detectable in WT equivalents (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

IL-22RA1 Signaling Restricts Intestinal Dysbiosis and Enterococcus faecalis Overcolonization during C. rodentium Infection

(A) Shannon diversity index of the fecal microbiota of WT and Il22ra1−/− mice (mean ± SEM) before C. rodentium infection (day 0) and at day 9 p.i. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

(B) Cluster dendogram of the microbial community structures of WT and Il22ra1−/− (KO) fecal and cecal microbiota (n = 3) before infection (day 0) and at day 9 p.i. at the operational taxonomic unit (OTU) level. Bar graphs represent proportional abundance.

(C) Immunofluorescence of C. rodentium and Enterococcus spp. in the cecum of infected WT and Il22ra1−/− mice. DAPI, cell nuclei. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(D) Fecal Enterococcus shedding of WT and Il22ra1−/− mice (n = 6–15) by selective plating, showing significant overgrowth during C. rodentium infection.

(E) Selective plating and 16S rRNA sequencing profile of enterococci in the feces and cecal mucosa of infected WT (n = 15) and Il22ra1−/− mice (n = 40) in five independent experiments, showing preferential expansion of E. faecalis (red) relative to other intestinal enterococci (E. gallinarum, gray). Shown are numbers of Enterococcus sequences matched to a species ID.

See also Figure S5.

Using group-specific qPCR and selective plating, we independently confirmed that Il22ra1−/− mice were colonized by a higher abundance of Enterobacteriaceae and Enterococcus spp., both within the intestinal lumen and at the mucosa (Figures S5C and S5D). Immunofluorescence labeling further revealed greater adherence of these pathogens to the colonic crypts of infected Il22ra1−/− mice (Figure 3C). Notably, by monitoring Enterococcus colonization over the course of C. rodentium infection, we detected a remarkable (∼3 log-fold) increase among Il22ra1−/− mice compared to WT equivalents (Figure 3D). Similarly, during DSS-induced colitis, we observed a much greater expansion of Enterococcus spp. in the lumen and mucosa of Il22ra1−/− mice (∼2 log-fold relative to WT littermates) (Figure S5E).

Intestinal dysbiosis can generally enhance the growth of facultative anaerobes such as the Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae (Lupp et al., 2007; Winter et al., 2013). Therefore, among the facultative anaerobic Enterococcus spp., we next sought to determine the expansion dynamics of E. faecalis specifically. By analyzing the 16S rRNA sequences of single enterococcal colonies, we identified a predominant expansion of E. faecalis among various enterococci in the microbiota of Il22ra1−/− mice (from 16% to 70% in the feces and 82% in the cecal mucosa) (Figure 3E). The vast majority of other enterococcal species in the mouse microbiota were identified as E. gallinarum, a common animal commensal rarely known to causes disease (Arias and Murray, 2012). By contrast, no significant change in the proportion of E. faecalis was detected in WT mice infected with C. rodentium (WT versus Il22ra1−/− mice: p < 0.01). Similarly, during DSS-induced colitis, Il22ra1−/− mice had a significantly greater expansion of E. faecalis than WT littermates (Figure S5F). Thus, the absence of IL-22RA1 appears to allow overcolonization by E. faecalis in relation to other Enterococcus spp. during intestinal inflammation.

To further exclude the possibility that the expansion of E. faecalis observed may be influenced by the presence of multiple subspecies, which cannot be detected by 16S rRNA gene sequencing, we isolated 30 independent E. faecalis isolates from different WT and Il22ra1−/− mice colonies over time (Table S4B). Whole-genome sequencing and in vitro hemolytic assays indicated that the microbiota of WT and Il22ra1−/− mice contained the same E. faecalis isolate and that this isolate was recovered repeatedly in the feces, livers, and spleens of Il22ra1−/− mice (Table S4B). Taken together, our results demonstrate that IL-22RA1 plays a role in limiting intestinal colonization and dissemination of a particular virulent E. faecalis isolate.

Epithelial IL-22RA1 Signaling Mediates Diverse Antimicrobial and Glycosylation Factors

The cytokine IL-22 has been shown to enhance pathogen defense by inducing the bactericidal lectin RegIIIγ (Zheng et al., 2008), which can inhibit various Gram-positive microbes in vitro (Cash et al., 2006), and limit colonization of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (VRE) in the small intestine (Kinnebrew et al., 2010). During C. rodentium infection, Il22ra1−/− mice indeed showed diminished expression levels of RegIIIγ (Figure S6A). To directly determine whether RegIIIγ mediates resistance to opportunistic E. faecalis in vivo, we infected RegIIIγ-/- mice orally with C. rodentium. RegIIIγ deficiency does not appear to influence the colonization of C. rodentium or E. faecalis in the feces or cecal lumen (Figures 4A–4D). However, mucosal colonization of E. faecalis at day 9 p.i. increased among RegIIIγ−/− mice (Figure 4D). This is consistent with an inhibitory activity of RegIIIγ against adherence by Gram-positive microbes (Vaishnava et al., 2011). However, all RegIIIγ−/− mice (n = 14) survived the infection, showing a level of intestinal histopathology similar to that of WT and no evidence of systemic bacterial dissemination (Figures 4E and S6B). Thus, additional factors downstream of IL-22RA1 may be necessary for the maintenance of intestinal colonization resistance.

Figure 4.

RegIIIγ−/− Mice Did Not Show Enhanced Susceptibility to C. rodentium

(A–E) WT and RegIIIγ−/− mice were infected orally with 109C. rodentium. (A) Shedding of C. rodentium and (B) E. faecalis over the course of infection. Bacterial load of (C) C. rodentium and (D) E. faecalis in the cecal lumen and mucosal tissues, determined by selective plating. (E) Cecal histopathology of C. rodentium-infected WT and RegIIIγ−/− mice at day 9 p.i., showing similar submucosal edema (asterisks) and inflammatory infiltrates (arrows). Scale bar, 100 μm. Results are from three independent experiments (n = 6–8 each).

To interrogate IL-22RA1 signaling specifically at the intestinal epithelium, we derived primary colonic organoids from WT and Il22ra1−/− mice (Sato et al., 2011) and evaluated their global transcriptomes by deep RNA sequencing. Il22ra1−/− organoids displayed a normal morphology, characterized by columnar enterocytes with microvilli, tight junctions, and mucus-producing goblet cells (Figures 5A and S6C). Consistent with the epithelial expression of IL-22RA1, in vitro stimulation with IL-22 led to an induction of the known antimicrobials RegIIIβ, RegIIIγ, S100a8, and S100a9 in WT and Il22−/− organoids, but not Il22ra1−/− organoids (Figure S6D). Next, hierarchical clustering of RNA-seq data from WT and Il22ra1−/− organoids upon IL-22 stimulation demonstrated their distinct genome-wide expression profiles (Figure 5B). Factors involved in inflammatory response, antimicrobial processes, and wound healing were significantly upregulated, consistent with the previously established functions of the IL-22/IL-22RA1 pathway (Figures 5C and S6E and Tables S5A–S5C). Conversely, genes encoding cellular metabolic processes and DNA replication were downregulated (Figure S6E and Table S5D). Notably, a variety of proteases (e.g., Prss22, Prss27, Slpi) and peroxidases (e.g., Gpx2, Duox1, Duox2, Duoxa2) with antimicrobial activity, together with innate recognition molecules (Tmem173, Zbp1), were also induced by IL-22RA1 signaling, highlighting the unexpectedly diverse antimicrobial function of this pathway (Figure S6F).

Figure 5.

RNA-Seq of IL-22RA1 Signaling in Colonic Epithelial Organoids Identifies Factors Associated with Host-Microbe Interactions

(A) LacZ staining of WT and Il22ra1−/− organoids (scale bar, 100 μm) (left) and transmission electron microscopy of an Il22ra1−/− organoid with microvilli (Mv), tight junctions (arrowheads), and goblet cell (G) (right; scale bar, 1 μm).

(B) RNA-seq transcriptomes of colonic organoids from wild-type (WT) and Il22ra1−/− (KO) mice (n = 4) treated with IL-22 or untreated (Ctrl) in technical replicates, showing hierarchical clustering. Colors indicate levels of correlation (low, light green-yellow; high, dark green-blue).

(C) Enriched biological processes among upregulated (orange) and downregulated (blue) genes downstream of IL-22RA1 signaling, with selected genes associated with glycosylation.

(D) Stat3-focused interaction network of genes induced by IL-22RA1 signaling (p < 10−12), 18 of which are associated with human susceptibility to chronic inflammatory diseases (gold). Lines indicate protein-protein interactions (dark/light blue), coexpression (black), colocalization (gray), and shared protein domains (cyan). See also Figure S6.

Among genes upregulated by IL-22RA1 signaling, we further identified a range of susceptibility genes to inflammatory bowel disease (Sec1, Fut2, Muc1, Prdm1, Xbp1, Nupr1, Erbb3, Efemp2, Chac1, Ppbp, Cxcl5, Stat3, Slc9a3, Bcl2l15) (Jostins et al., 2012), psoriasis (Rel, Nos2), and rheumatoid arthritis (Stom, Ptpn22) (Eyre et al., 2012) represented by a Stat3-focused cluster (Figure 5D). This finding underlines the complex involvement of the IL-22/IL-22RA1 axis in human inflammatory diseases linked to pathological host-microbial interactions and supports the utility of intestinal organoids for dissecting the functional consequences of IL-22RA1 signaling. Finally, we observed a high enrichment of protein glycosylation genes induced by IL-22RA1 (p < 10−4; Figures 5C and S6E and Tables S5A–S5C), which suggests a role for epithelial glycosylation in intestinal pathogen resistance.

Fucosylated Glycan Expression Enhances Colonization Resistance in Il22ra1−/− Mice

Glycoconjugates produced by the intestinal epithelium provide a rich source of host-derived complex carbohydrates that can impact the microbiota structure and function (Becker and Lowe, 2003). Among IL-22RA1-induced genes linked to epithelial glycosylation, Fut2 encodes an α1,2-fucosyltransferase highly expressed in the distal gut (Bry et al., 1996). The FUT2 enzyme is responsible for the expression of ABO histo-blood group antigens at the intestinal mucosa (Kelly et al., 1995). Importantly, Fut2 expression may influence the microbiota (Kashyap et al., 2013) and host susceptibilities to various bacterial pathogens (e.g., Campylobacter jejuni and Helicobacter pylori) and autoimmune disorders (e.g., Crohn’s disease) (Ilver et al., 1998; McGovern et al., 2010; Ruiz-Palacios et al., 2003). We found that Fut2 is highly upregulated by IL-22RA1 signaling both in cultured organoids (p = 2.21 × 10−188) and during C. rodentium infection in vivo (Figure 6A and Table S5). Accordingly, the intestinal mucosa of C. rodentium-infected Il22ra1−/− mice showed reduced staining with the fucose-binding Lotus tetragonolobus lectin compared to WT equivalents (Figure 6B), indicating a decreased fucosylation level in the absence of IL-22RA1 signaling.

Figure 6.

IL-22RA1-Mediated Fucosylated Glycan Expression Contributes to Host Defense

(A) Cecal Fut2 transcripts of WT and Il22ra1−/− mice (n = 9–12) at day 9 p.i. with C. rodentium.

(B) Immunofluorescence staining of WT and Il22ra1−/− cecal tissues with Lotus tetragonolobus lectin (green).

(C–E) WT mice and groups of Il22ra1−/− littermates were treated orally with 2′-fucosyllactose (2′FL), blood group H disaccharide (or H antigen; H-Ag), lactose, or PBS between days 5 and 8 p.i. during C. rodentium infection. Shown are (C) survival (left) and weight loss (right), (D) histopathology (scale bar, 200 μm), and (E) total number of cLP leukocytes at day 9 p.i.

(F and G) qPCR of (F) Th1 cytokines (IFNγ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and (G) Th17-associated cytokines (IL-17a, IL-17f, IL-21, IL-22) in the cecal tissues at day 9 p.i.

To test if induction of epithelial fucosylation mediated by IL-22RA1 may contribute to intestinal host defense, we administered physiologically relevant doses of 2′-fucosyllactose (2′FL), an α1,2-fucosylated oligosaccharide, orally to Il22ra1−/− mice during C. rodentium infection. Treatment with 2′FL from day 4 p.i. significantly attenuated the early morbidity and mortality of infected Il22ra1−/− mice (Figure 6C). Administration of blood group H disaccharide (another α1,2-fucosylated molecule similar to the mucosal antigen mediated by the FUT2 enzyme) similarly led to attenuation of the infection outcome in Il22ra1−/− mice, while administration of lactose alone did not (Figure 6C).

We next investigated the beneficial effect of fucosylated glycans in Il22ra1−/− mice by assessing their histopathology, inflammatory responses, and bacterial colonization. 2′FL treatment did not appear to significantly reduce intestinal pathology or the Th1/Th17 inflammation in Il22ra1−/− mice at day 9 p.i. (Figures 6D–6G). We also observed similar C. rodentium colonization between 2′FL-treated and PBS controls (Figure 7A). However, luminal and mucosal colonization of E. faecalis significantly decreased among the 2′FL-treated group (Figure 7B). This correlates with lower levels of E. faecalis dissemination and of systemic IL-6 and TNF-α (Figures 7C and 7D), indicating that intestinal abundance of fucosylated molecules may play a role in the restriction of E. faecalis in the microbiota.

Figure 7.

Fucosylated Glycan Expression Enhances Colonization Resistance to E. faecalis

(A–D) C. rodentium-infected WT mice and groups of Il22ra1−/− littermates were treated orally with 2′-fucosyllactose (2′FL) or PBS. Shown are (A) C. rodentium shedding, (B) E. faecalis cfus in the colonic lumen and mucosa (gray area, detection limit), (C) E. faecalis cfus in the liver and spleen, and (D) serum IL-6 and TNF-α levels at day 9 p.i. Mean ± SEM of data from three independent experiments (n = 3–5 each); ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

(E) Shannon diversity index of the fecal microbiota before infection (day 0) and at day 9 p.i.

(F) Cluster dendogram of the fecal microbiota community structures of 2′FL-treated Il22ra1−/− mice and PBS-treated controls (Ctrl). Bar graphs represent proportional abundance.

Within the intestinal microbiota, some obligate anaerobes such as the Ruminococcaceae and Bacteroides spp. may benefit from host-derived fucosylated glycans (Marcobal et al., 2011; Martens et al., 2008). We reasoned that fucosylated glycans in the intestine could restrict colonization by opportunistic pathogens (e.g., E. faecalis) in part by enhancing the growth of some commensals. By 16S rRNA sequencing, we compared the microbiota diversity and composition of Il22ra1−/− mice treated with 2′FL to PBS-treated littermate controls during C. rodentium infection. While no significant difference was observed in the baseline microbiota between both groups, 2′FL treatment resulted in an increase of bacterial species richness and diversity (shown by the Shannon diversity index) by day 9 p.i. (Figure 7E). Furthermore, analyses based on the community structure revealed a remarkable shift in the microbial composition upon 2′FL treatment (weighted UniFrac; p < 0.001) (Figure 7F). In particular, we detected a significantly greater abundance of Bacteroides spp. (2.4-fold; p < 0.0001) and Ruminococcaceae (7.9-fold; p < 0.0001) in the 2′FL-treated group. Thus, our results suggest that IL-22RA1-mediated production of intestinal fucosylated conjugates plays a role in colonization resistance by restoring the anaerobic commensal diversity.

Discussion

Given that IL-22 dysregulations are implicated in many human diseases linked to pathological host-microbiota interactions (Sabat et al., 2014), and Il22 deficiency can lead to different infection susceptibility phenotypes (Feinen and Russell, 2012; Graham et al., 2011), we reasoned that the indigenous microbiota could be a critical factor for disease induction. Although absence of IL-22 has been reported to associate with a colitogenic microbiota (Behnsen et al., 2014; Zenewicz et al., 2013), we found that our Il22ra1−/− mice harbor a microbiota highly similar (in both diversity and community structure) to that of WT controls. This difference underscores the potential impact of animal husbandry conditions in different facilities and suggests that factors besides a healthy SPF microbiota might be necessary for disease induction in Il22ra1−/− mice.

We observed that Il22ra1 deficiency predisposes mice to a severe disseminated bacterial infection upon disruption of the microbiota by C. rodentium infection or DSS colitis. Although extraintestinal spread of C. rodentium has been reported in Il22−/− mice (Zheng et al., 2008), the contribution of invasion by C. rodentium or other intestinal bacteria to host susceptibility has not been fully explored. We identified that an E. faecalis isolate was the predominant intestinal bacterium that disseminates among susceptible Il22ra1−/− mice and that this E. faecalis isolate possesses a range of important virulence factors relevant for nosocomial disease in humans. Notably, E. faecalis possesses a functional cytolysin associated with bacterial invasion and virulence (Huycke et al., 1991) and is capable of invading the intestinal epithelium in a manner similar to that of the human pathogen E. faecalis V583 (Benjamin et al., 2013). Furthermore, mice are highly susceptible to systemic E. faecalis infection, and C. rodentium-infected Il22ra1−/− mice may be rescued through antibiotic inhibition of E. faecalis. Thus, E. faecalis represents an opportunistic pathogen capable of disease induction in the Il22ra1−/− host.

Intestinal dysbiosis often acts as a predisposing factor to infectious diseases, as diverse bacterial pathogens such as S. Typhimurium and Clostridium difficile may exploit disruptions of the microbiota to establish replicative niches (Lawley et al., 2012; Stecher et al., 2007). Here we found that while WT mice were able to maintain a low level of colonization by E. faecalis (∼104–105 colony-forming units [cfu]/g of feces), Il22ra1−/− mice were predisposed to unrestricted E. faecalis proliferation (107–109 cfu/g) during both C. rodentium- and DSS-induced dysbiosis. Moreover, we noted a preferential expansion of a pathogenic E. faecalis variant in comparison to other commensal enterococci (i.e., E. gallinarum). Thus, although intestinal inflammation is thought to generally promote the growth of facultative anaerobes, our result highlights the importance of assessing intestinal dysbiosis at the species level to potentially distinguish between disease-causing and commensal microbes belonging to the same bacterial taxa.

The antimicrobial response of IL-22 to bacterial pathogens has been shown to involve RegIIIγ, which is highly expressed in the small intestine and bactericidal against Gram-positive bacteria (Cash et al., 2006; Kinnebrew et al., 2010). Interestingly, while we found that RegIIIγ−/− mice had increased levels of mucosa-associated E. faecalis, their expansion in the luminal microbiota and translocation to systemic organs were unaffected. Thus, together with the diverse network of antimicrobial factors uncovered by our RNA-seq analysis of epithelial organoids, this finding underlines the multifactorial nature of IL-22RA1 signaling in host-microbiota interactions.

By our organoid transcriptomic approach, we further identified the α1,2-fucosyltransferase gene Fut2 as a candidate factor regulated by IL-22RA1 signaling. Fut2 is critically involved in regulating the fucose nutrient environment of the microbiota (Kashyap et al., 2013) as well as host susceptibility to bacterial and viral pathogens (Ilver et al., 1998; Lindesmith et al., 2003; Ruiz-Palacios et al., 2003). Interestingly, fucosylated glycans typically increase during gut maturation (Bry et al., 1996) and infection (Deatherage Kaiser et al., 2013), a process that is thought to beneficially enhance bacterial colonization. Here we found that epithelial expression of Fut2 is directly induced by IL-22RA1 signaling, which is consistent with a lower level of fucosylated glycans at the colonic mucosa of Il22ra1−/− mice during infection.

We further observed that restoration of fucosylated molecules in the intestine can attenuate the susceptibility of Il22ra1−/− mice and decrease E. faecalis colonization at the intestinal lumen and mucosa. Although 2′FL administration did not appear to have an anti-inflammatory effect, we detected a clear impact on the microbiota diversity and composition, characterized by an increased abundance of some anaerobic commensal populations. Interestingly, colonization resistance to VRE has been shown to involve Barnesiella spp., which are Gram-negative saccharolytic commensals belonging to the family Porphyromonadaceae (Ubeda et al., 2013). In agreement with this study, we observed a higher colonization of Porphyromonadaceae in the 2′FL-treated group (1.5-fold). Moreover, the fucose-utilizing, anaerobic Ruminococcaceae and Bacteroides spp. were remarkably enriched (7.9-fold and 2.4-fold, respectively), which further supports the notion that intestinal fucosylation provides a nutrient foundation for symbiotic commensals (Hooper and Gordon, 2001).

The intestinal microbiota represents a complex and highly controlled nutrient network that is crucial for colonization resistance to diverse bacterial pathogens. For example, upon depletion of commensal microbes, S. Typhimurium can upregulate its fucose utilization operon (Deatherage Kaiser et al., 2013) and exploit the increased abundance of fucose and sialic acids to colonize the intestine (Ng et al., 2013). Therapeutic modulation of the microbiota, by dietary intake of prebiotic substances or administration of health-associated bacteria, therefore provides an attractive opportunity for the management of intestinal infections (Lawley et al., 2012). Here, our data support a mechanistic model whereby the IL-22RA1/Fut2 axis is involved in the maintenance of a diverse healthy microbiota, which in turn promotes intestinal colonization against the opportunistic pathogen E. faecalis. Further insights into the molecular interactions between IL-22RA1-mediated glycosylation pathways and symbiotic members of the intestinal microbiota could potentially yield opportunities for the treatment of intestinal dysbiosis in infectious and autoimmune diseases.

Experimental Procedures

Mouse Infection

Il22ra1tm1a/tm1a, RegIIIγtm1a/tm1a, and WT C57BL/6N mice were maintained and phenotyped by the Sanger Mouse Genetics Programme (White et al., 2013). Endogenous Il22ra1 expression was detected by overnight incubation with 0.1% (w/v) X-gal (Invitrogen). All animals were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions, and colony sentinels tested negative for Helicobacter spp. Mice were infected orally with 109 cfu of Kanamycin (Kan)- and nalidixic acid (Nal)-resistant luminescent Citrobacter rodentium ICC180 (Wiles et al., 2006) or intravenously (i.v.) with 105 cfu Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium M525 TETc (Clare et al., 2003). Where indicated, C. rodentium-infected mice were administered intraperitoneal (i.p.) ampicillin (50 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich), oral 2′-fucosyllactose, H disaccharide, lactose (2 mg/day; Carbosynth), or PBS controls. DSS colitis was induced by administering 2% (w/v) DSS (MP Biomedicals) in drinking water for 7 days, followed by normal autoclaved water. The care and use of mice were in accordance with the UK Home Office regulations (UK Animals Scientific Procedures Act 1986) and were approved by the Sanger Institute’s Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body.

C. rodentium Immunoglobulin ELISA

NUNC Maxisorp ELISA plates were coated overnight with 100 μg/well Citrobacter EspA protein and blocked with 3% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich). Serum and fecal supernatant samples were added in 1:5 serial dilutions for 1 hr at 37°C. We detected immunoglobulin levels with HRP-conjugated rabbit α-mouse total IgG or IgA antibodies (1/1,000; Invitrogen).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from mouse cecal tissues using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Quantitative real-time PCR was conducted with a 7900HT RealTime PCR system (Applied Biosystems), using ABsolute Blue Rox Mix (Thermo Scientific), TaqMan primers, and probes as detailed in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

16S rRNA-Based Identification of Bacterial Species

To identify microbial species from the livers and spleens of mice, we homogenized mouse tissues aseptically under laminar flow. Organ lysates were immediately cultured in nonselective Luria-Bertani (LB), BHI (Brain Heart Infusion), and FAA (Fastidious Anaerobe Agar) media under aerobic and anaerobic conditions for 36–48 hr. All colonies from each plate, or within a defined section, were picked in an unbiased manner for DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene sequencing using the universal primers: 7F, 5′-AGAGTTTGATYMTGGCTCAG-3′; 926R, 5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′. Bacterial identifications were performed using the 16S rRNA NCBI Database for Bacteria and Archeae.

Bacterial Genomic and Phylogenetic Analysis

Genomic DNA from Enterococcus faecalis isolates were prepared from overnight cultures using a standard phenol-chloroform extraction procedure and sequenced by Illumina MiSeq 2000. We performed genome assembly and comparative genomics with the previously sequenced E. faecalis V583 genome (Paulsen et al., 2003) and the E. faecalis MMH594 pathogenicity island (GenBank accession number AF454824) (Shankar et al., 2002). To profile the diversity of enterococci in the mouse microbiota, we sequenced the 16S rRNA gene of single enterococcal colonies on selective Bile Esculin Azide agar (Sigma-Aldrich) in an unbiased manner. Representative Enterococcus faecalis isolates were selected for whole-genome sequencing, generating ∼50× genome coverage/isolate. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the previously published full and draft genomes of 43 E. faecalis strains collected from diverse human and animal sources (McBride et al., 2007). See also Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Microbiota Analyses

Bacterial DNA was obtained using the FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil (MBio) and FastPrep Instrument (MPBiomedicals). V5-V3 regions of bacterial 16S rRNA genes were PCR amplified with high-fidelity AccuPrime Taq Polymerase (Invitrogen) and primers: 338F, 5′-CCGTCAATTCMTTTRAGT-3′; 926R, 5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′. Libraries were sequenced by 454 (Roche) or MiSeq (Illumina). Analyses were performed with the mothur software (Schloss et al., 2009), using quality filtering and analysis parameters as described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures. For quantification of group-specific bacteria, we used the following primers: F, 5′-ATGGCTGTCGTCAGCTCGT-3′; R, 5′-CCTACTTCTTTTGCAACCCACTC-3′ (for Enterobacteriaceae) and F, 5′-CCCTTATTGTTAGTTGCCATCATT-3′; R, 5′-ACTCGTTGTACTTCCCATTGT-3′ (for Enterococcus spp.).

Intestinal Organoid Transcriptomics

Organoids from mouse colons were isolated and cultured in vitro as described (Sato et al., 2011). For RNA-seq, 1-week-old organoids of WT and Il22ra1−/− mice (n = 4) were treated with IL-22 (50 ng/ml) or controls in complete growth medium. mRNA libraries were prepared using the Illumina TruSeq protocol and sequenced by Illumina HiSeq to yield ∼6.4 ± 0.25 giga-base pairs (Gbp)/sample. Normalized read counts (aligned to the reference mm10/NCBIM37 genome) were used to assess the statistical significance of the interaction between IL-22 treatment and Il22ra1 genotype, as described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures. At p < 10−12, 364 genes were identified as upregulated and 197 genes were identified as downregulated by IL-22/IL-22RA1 signaling.

Statistical Analysis

We applied nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests for pairwise statistical comparisons and two-way ANOVA for comparisons of grouped data using the Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Wellcome Trust, the Medical Research Council UK, and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute Mouse Genetics Programme. We are grateful to F. Powrie (Oxford University) for providing Il22 knockout mice; C. Brandt and G. Notley for assistance with colony maintenance; E. Ryder for genotyping; A. Walker for microbiota analysis and interpretation; L. Barquist for genome visualization; J. Estabel and the MGP for histology; and N. Smerdon for assistance with RNA-seq. We also thank J. Parkhill, S. Mukhopadhyay, M. Duque (WTSI), K. Maloy (Oxford), and A. Kaser (Cambridge University) for their critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/).

Accession Numbers

The European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) accession numbers for the E. faecalis genome data, microbiota sequencing data, and RNA-seq data reported in this paper are ERR225616, ERP002393, and ERR247358–ERR247389, respectively.

Supplemental Information

References

- Arias C.A., Murray B.E. The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:266–278. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aujla S.J., Chan Y.R., Zheng M., Fei M., Askew D.J., Pociask D.A., Reinhart T.A., McAllister F., Edeal J., Gaus K. IL-22 mediates mucosal host defense against Gram-negative bacterial pneumonia. Nat. Med. 2008;14:275–281. doi: 10.1038/nm1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker D.J., Lowe J.B. Fucose: biosynthesis and biological function in mammals. Glycobiology. 2003;13:41R–53R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnsen J., Jellbauer S., Wong C.P., Edwards R.A., George M.D., Ouyang W., Raffatellu M. The cytokine IL-22 promotes pathogen colonization by suppressing related commensal bacteria. Immunity. 2014;40:262–273. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin J.L., Sumpter R., Jr., Levine B., Hooper L.V. Intestinal epithelial autophagy is essential for host defense against invasive bacteria. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:723–734. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgogne A., Garsin D.A., Qin X., Singh K.V., Sillanpaa J., Yerrapragada S., Ding Y., Dugan-Rocha S., Buhay C., Shen H. Large scale variation in Enterococcus faecalis illustrated by the genome analysis of strain OG1RF. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R110. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-7-r110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bry L., Falk P.G., Midtvedt T., Gordon J.I. A model of host-microbial interactions in an open mammalian ecosystem. Science. 1996;273:1380–1383. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5280.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash H.L., Whitham C.V., Behrendt C.L., Hooper L.V. Symbiotic bacteria direct expression of an intestinal bactericidal lectin. Science. 2006;313:1126–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.1127119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare S., Goldin R., Hale C., Aspinall R., Simmons C., Mastroeni P., Dougan G. Intracellular adhesion molecule 1 plays a key role in acquired immunity to salmonellosis. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:5881–5891. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5881-5891.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deatherage Kaiser B.L., Li J., Sanford J.A., Kim Y.M., Kronewitter S.R., Jones M.B., Peterson C.T., Peterson S.N., Frank B.C., Purvine S.O. A Multi-Omic View of Host-Pathogen-Commensal Interplay in Salmonella-Mediated Intestinal Infection. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre S., Bowes J., Diogo D., Lee A., Barton A., Martin P., Zhernakova A., Stahl E., Viatte S., McAllister K., Biologics in Rheumatoid Arthritis Genetics and Genomics Study Syndicate. Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium High-density genetic mapping identifies new susceptibility loci for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:1336–1340. doi: 10.1038/ng.2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinen B., Russell M.W. Contrasting Roles of IL-22 and IL-17 in Murine Genital Tract Infection by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Front Immunol. 2012;3:11. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham A.C., Carr K.D., Sieve A.N., Indramohan M., Break T.J., Berg R.E. IL-22 production is regulated by IL-23 during Listeria monocytogenes infection but is not required for bacterial clearance or tissue protection. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper L.V., Gordon J.I. Glycans as legislators of host-microbial interactions: spanning the spectrum from symbiosis to pathogenicity. Glycobiology. 2001;11:1R–10R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/11.2.1r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huycke M.M., Spiegel C.A., Gilmore M.S. Bacteremia caused by hemolytic, high-level gentamicin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1626–1634. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.8.1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilver D., Arnqvist A., Ogren J., Frick I.M., Kersulyte D., Incecik E.T., Berg D.E., Covacci A., Engstrand L., Borén T. Helicobacter pylori adhesin binding fucosylated histo-blood group antigens revealed by retagging. Science. 1998;279:373–377. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jett B.D., Huycke M.M., Gilmore M.S. Virulence of enterococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1994;7:462–478. doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.4.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jostins L., Ripke S., Weersma R.K., Duerr R.H., McGovern D.P., Hui K.Y., Lee J.C., Schumm L.P., Sharma Y., Anderson C.A., International IBD Genetics Consortium (IIBDGC) Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491:119–124. doi: 10.1038/nature11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap P.C., Marcobal A., Ursell L.K., Smits S.A., Sonnenburg E.D., Costello E.K., Higginbottom S.K., Domino S.E., Holmes S.P., Relman D.A. Genetically dictated change in host mucus carbohydrate landscape exerts a diet-dependent effect on the gut microbiota. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:17059–17064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306070110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly R.J., Rouquier S., Giorgi D., Lennon G.G., Lowe J.B. Sequence and expression of a candidate for the human Secretor blood group alpha(1,2)fucosyltransferase gene (FUT2). Homozygosity for an enzyme-inactivating nonsense mutation commonly correlates with the non-secretor phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:4640–4649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnebrew M.A., Ubeda C., Zenewicz L.A., Smith N., Flavell R.A., Pamer E.G. Bacterial flagellin stimulates Toll-like receptor 5-dependent defense against vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;201:534–543. doi: 10.1086/650203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawley T.D., Clare S., Walker A.W., Stares M.D., Connor T.R., Raisen C., Goulding D., Rad R., Schreiber F., Brandt C. Targeted restoration of the intestinal microbiota with a simple, defined bacteriotherapy resolves relapsing Clostridium difficile disease in mice. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002995. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindesmith L., Moe C., Marionneau S., Ruvoen N., Jiang X., Lindblad L., Stewart P., LePendu J., Baric R. Human susceptibility and resistance to Norwalk virus infection. Nat. Med. 2003;9:548–553. doi: 10.1038/nm860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupp C., Robertson M.L., Wickham M.E., Sekirov I., Champion O.L., Gaynor E.C., Finlay B.B. Host-mediated inflammation disrupts the intestinal microbiota and promotes the overgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:204. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcobal A., Barboza M., Sonnenburg E.D., Pudlo N., Martens E.C., Desai P., Lebrilla C.B., Weimer B.C., Mills D.A., German J.B., Sonnenburg J.L. Bacteroides in the infant gut consume milk oligosaccharides via mucus-utilization pathways. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:507–514. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens E.C., Chiang H.C., Gordon J.I. Mucosal glycan foraging enhances fitness and transmission of a saccharolytic human gut bacterial symbiont. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride S.M., Fischetti V.A., Leblanc D.J., Moellering R.C., Jr., Gilmore M.S. Genetic diversity among Enterococcus faecalis. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern D.P., Jones M.R., Taylor K.D., Marciante K., Yan X., Dubinsky M., Ippoliti A., Vasiliauskas E., Berel D., Derkowski C., International IBD Genetics Consortium Fucosyltransferase 2 (FUT2) non-secretor status is associated with Crohn’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:3468–3476. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng K.M., Ferreyra J.A., Higginbottom S.K., Lynch J.B., Kashyap P.C., Gopinath S., Naidu N., Choudhury B., Weimer B.C., Monack D.M., Sonnenburg J.L. Microbiota-liberated host sugars facilitate post-antibiotic expansion of enteric pathogens. Nature. 2013;502:96–99. doi: 10.1038/nature12503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen I.T., Banerjei L., Myers G.S., Nelson K.E., Seshadri R., Read T.D., Fouts D.E., Eisen J.A., Gill S.R., Heidelberg J.F. Role of mobile DNA in the evolution of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Science. 2003;299:2071–2074. doi: 10.1126/science.1080613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffatellu M., Santos R.L., Verhoeven D.E., George M.D., Wilson R.P., Winter S.E., Godinez I., Sankaran S., Paixao T.A., Gordon M.A. Simian immunodeficiency virus-induced mucosal interleukin-17 deficiency promotes Salmonella dissemination from the gut. Nat. Med. 2008;14:421–428. doi: 10.1038/nm1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Palacios G.M., Cervantes L.E., Ramos P., Chavez-Munguia B., Newburg D.S. Campylobacter jejuni binds intestinal H(O) antigen (Fuc alpha 1, 2Gal beta 1, 4GlcNAc), and fucosyloligosaccharides of human milk inhibit its binding and infection. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:14112–14120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207744200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabat R., Ouyang W., Wolk K. Therapeutic opportunities of the IL-22-IL-22R1 system. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:21–38. doi: 10.1038/nrd4176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., Stange D.E., Ferrante M., Vries R.G., Van Es J.H., Van den Brink S., Van Houdt W.J., Pronk A., Van Gorp J., Siersema P.D., Clevers H. Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1762–1772. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schloss P.D., Westcott S.L., Ryabin T., Hall J.R., Hartmann M., Hollister E.B., Lesniewski R.A., Oakley B.B., Parks D.H., Robinson C.J. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar N., Baghdayan A.S., Gilmore M.S. Modulation of virulence within a pathogenicity island in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Nature. 2002;417:746–750. doi: 10.1038/nature00802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarnes W.C., Rosen B., West A.P., Koutsourakis M., Bushell W., Iyer V., Mujica A.O., Thomas M., Harrow J., Cox T. A conditional knockout resource for the genome-wide study of mouse gene function. Nature. 2011;474:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenberg G.F., Fouser L.A., Artis D. Border patrol: regulation of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis at barrier surfaces by IL-22. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:383–390. doi: 10.1038/ni.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecher B., Hardt W.D. The role of microbiota in infectious disease. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecher B., Hardt W.D. Mechanisms controlling pathogen colonization of the gut. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011;14:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecher B., Robbiani R., Walker A.W., Westendorf A.M., Barthel M., Kremer M., Chaffron S., Macpherson A.J., Buer J., Parkhill J. Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium exploits inflammation to compete with the intestinal microbiota. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:2177–2189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubeda C., Bucci V., Caballero S., Djukovic A., Toussaint N.C., Equinda M., Lipuma L., Ling L., Gobourne A., No D. Intestinal microbiota containing Barnesiella species cures vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium colonization. Infect. Immun. 2013;81:965–973. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01197-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaishnava S., Yamamoto M., Severson K.M., Ruhn K.A., Yu X., Koren O., Ley R., Wakeland E.K., Hooper L.V. The antibacterial lectin RegIIIgamma promotes the spatial segregation of microbiota and host in the intestine. Science. 2011;334:255–258. doi: 10.1126/science.1209791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J.K., Gerdin A.K., Karp N.A., Ryder E., Buljan M., Bussell J.N., Salisbury J., Clare S., Ingham N.J., Podrini C., Sanger Institute Mouse Genetics Project Genome-wide generation and systematic phenotyping of knockout mice reveals new roles for many genes. Cell. 2013;154:452–464. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles S., Pickard K.M., Peng K., MacDonald T.T., Frankel G. In vivo bioluminescence imaging of the murine pathogen Citrobacter rodentium. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:5391–5396. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00848-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M.S., Feng C.G., Barber D.L., Yarovinsky F., Cheever A.W., Sher A., Grigg M., Collins M., Fouser L., Wynn T.A. Redundant and pathogenic roles for IL-22 in mycobacterial, protozoan, and helminth infections. J. Immunol. 2010;184:4378–4390. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter S.E., Winter M.G., Xavier M.N., Thiennimitr P., Poon V., Keestra A.M., Laughlin R.C., Gomez G., Wu J., Lawhon S.D. Host-derived nitrate boosts growth of E. coli in the inflamed gut. Science. 2013;339:708–711. doi: 10.1126/science.1232467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk K., Kunz S., Witte E., Friedrich M., Asadullah K., Sabat R. IL-22 increases the innate immunity of tissues. Immunity. 2004;21:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenewicz L.A., Yin X., Wang G., Elinav E., Hao L., Zhao L., Flavell R.A. IL-22 deficiency alters colonic microbiota to be transmissible and colitogenic. J. Immunol. 2013;190:5306–5312. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Valdez P.A., Danilenko D.M., Hu Y., Sa S.M., Gong Q., Abbas A.R., Modrusan Z., Ghilardi N., de Sauvage F.J., Ouyang W. Interleukin-22 mediates early host defense against attaching and effacing bacterial pathogens. Nat. Med. 2008;14:282–289. doi: 10.1038/nm1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.