Summary

Mammalian messenger and long non-coding RNA contain tens of thousands of post-transcriptional chemical modifications. Among these, the N6-methyl-adenosine (m6A) modification is the most abundant and can be removed by specific mammalian enzymes. M6A modification is recognized by families of RNA binding proteins that affect many aspects of mRNA function. mRNA/lncRNA modification represents another layer of epigenetic regulation of gene expression, analogous to DNA methylation and histone modification.

Keywords: RNA, modification, N6-methyl, m6A, demodification

Introduction

Over 100 types of post-transcriptional modifications have been identified in cellular RNA starting in the 1950s (http://mods.rna.albany.edu/). For example, the human ribosomal RNA (rRNA) contains over 200 modifications consisting of three major types 1: ∼100 2′-O-methylated nucleotides (Nm), ∼100 pseudouridines (Ψ), and ∼10 base methylations (e.g. 5-methyl-cytosine, m5C). Each human transfer RNA (tRNA) contains on average 14 modifications consisting of various base methylations, Ψ, Nm and chemically elaborate, modified wobble bases that require catalysis by multiple enzymes 2, 3. rRNA modifications are generally used as quality control checkpoints in ribosome assembly 4. tRNA modifications outside the anticodon loop are generally used to maintain tRNA stability or modulate tRNA folding, whereas modifications in the anticodon loop are generally used to tune decoding capacity and to control decoding accuracy 5.

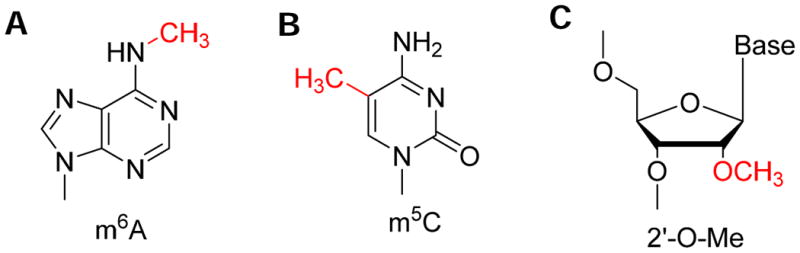

Up until two years ago, internal modifications in mRNA and long non-coding RNA were very much neglected. Discovered in the 1970s 6-9, the most abundant internal mRNA/lncRNA modification is made of N6-methyl adenosine (m6A), present on average in over 3 sites per mRNA molecule (10-13, Fig. 1A). Other types of modifications such as m5C or 2′O-methylated nucleotides have also been indicated to occur internally in mRNA (9, 14 Fig. 1B, 1C), and many m5C modification sites have now been identified 15, 16. A common feature of these modifications is that their presence cannot be detected by the commonly used reverse transcriptases in cDNA synthesis. It was therefore extremely difficult to map these modifications at single nucleotide resolution. Global m6A modification was shown to be functionally important as siRNA knockdown of a known human m6A-methyltransferase (METTL3) led to apoptosis in cell culture17. Suggested functions for m6A modification include effects on mRNA splicing, transport, stability, and immune tolerance 17, 18.

Fig. 1. Chemical structure of internal mRNA/lncRNA modifications.

(A) m6A; (B) m5C; (C) Nm.

Interest in mRNA/lncRNA modification was revived in 2011 upon the discovery that m6A modification is the cellular substrate for the human enzyme FTO 19. FTO belongs to a family of human genes that are homologous to the E. coli AlkB protein which catalyzes oxidative reversal of methylated DNA and RNA bases 20, 21. In genome-wide association studies, the human FTO gene is highly associated with diabetes and obesity in the human population 22, 23. FTO knockout mice are much leaner than the wild-type mice, presumably due to perturbations in controlling cellular metabolism 24. The discovery of FTO acting on m6A in mRNA/lncRNA indicates that m6A modification is subject to sophisticated cellular control.

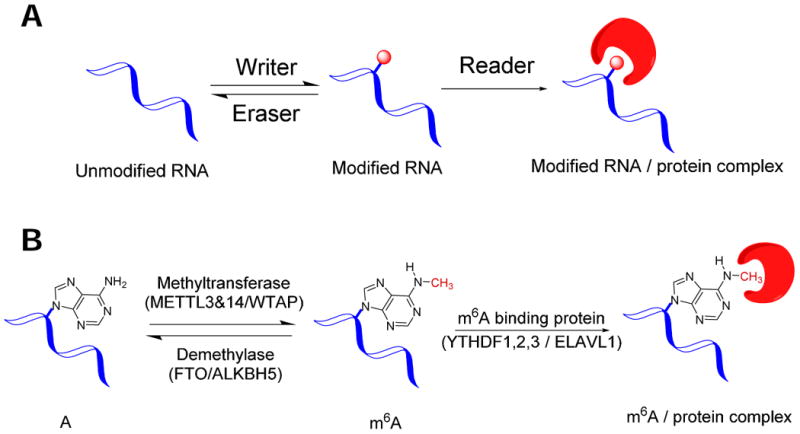

The discovery of this first RNA demodification enzyme also highlights the idea that RNA modification may act as epigenetic markers and controls akin to DNA methylation and histone modification 25, 26. Three groups of proteins are needed for epigenetic control that maintains specific modification patterns in cell type and cell state dependent manners. “Writers” catalyze chemical modification at specific sites; “erasers” remove modification at specific sites; and “readers” recognize the modified sites in DNA or histones (Fig. 2A). For m6A in mRNA/lncRNA, members in all three groups of proteins have now been found in mammalian cells (Fig. 2B). However, the current list of these proteins likely represents just the beginning. In particular, the number of reader proteins that recognize m6A modified mRNA/lncRNA sites will certainly expand greatly in the coming years. As of today, only the m6A modification has been shown to exhibit all signatures of epigenetic regulation. This review therefore focuses on m6A modifications in mRNA/lncRNA with an emphasis on its effect on human health and disease.

Fig. 2. RNA epigenetic marking and control requires three groups of proteins.

(A) Schematic plot for general RNA modification. Writer = modification enzymes; eraser = demodification enzymes; reader = RNA binding proteins that recognize specific sites in the modified mRNA/lncRNA. (B) Schematic plot for the m6A modification.

Techniques used to study m6A in mRNA/lncRNA

A pre-requisite for mRNA/lncRNA transcriptome studies is the copying of RNA into cDNA by reverse transcriptase (RT). M6A modification does not affect Watson-Crick base pairing, and it behaves like an unmodified adenosine for the commonly used RTs. A widely applied method for m6A study is to use immunoprecipitation (IP) with a commercial m6A-antibody followed by high throughput sequencing (m6A-seq or MeRIP-seq, 27, 28). The mRNA/lncRNA mixture is first chemically fragmented to produce suitably sized RNA segments for deep sequencing and to increase the resolution of m6A detection. The fragmented RNA is split in two: one is used for m6A-antibody IP to enrich RNA segments that contain m6A, and the other is used as the reference. The location of m6A modification is obtained by comparing the sequencing read profiles of both samples. This method could readily identify tens of thousands of candidate m6A modification sites in mammalian mRNA/lncRNA at an average resolution of ∼100 nucleotides 27, 28. Studies prior to the advent of high throughput sequencing have determined a consensus sequence for mammalian m6A modification consisting of RRACH (R=A,G, H=A,C,U, m6A site underlined, 13). Indeed, this consensus sequence is present in a majority of m6A/MeRIP-seq peaks. Peaks without this consensus sequence are likely m6A-antibody binding artifacts as demonstrated in a yeast m6A study 29.

To map transcriptome-wide m6A sites at or near single nucleotide resolution, a combination of high coverage sequencing and bioinformatics was used in the yeast m6A study for ∼1,300 m6A sites 29. This approach may not be readily applicable to mammalian RNA where the number of m6A sites is at least one order of magnitude greater and the context of m6A modification is much more diverse. It was shown recently that the HIV RT is sensitive to the presence of m6A in RNA using the single molecule real time sequencing method by Pacific Biosciences 30. The Thermus thermophilus DNA polymerase I can work as a reverse transcriptase in the presence of Mn2+; this RT activity is sensitive to the presence of m6A modification in the RNA template 31. It remains to be seen whether these particular RT activities will be further developed for high resolution, transcriptome-wide identification of m6A sites.

Liu et al developed a low throughput method that can directly determine the presence and the modification fraction of candidate m6A site at single nucleotide resolution (termed SCARLET, 32). The SCARLET method starts with total polyA+ RNA. Hybridization of a specific 2′-O-Me-2′-deoxy oligonucleotide enables a single, site-specific cut by RNase H at the 5′ of the candidate site which is first identified from the m6A/MeRIP-seq data. The cut site is radio-labeled with 32P, followed by targeted ligation with a long, single-stranded DNA oligo. The sample is then digested with ribonucleases to completion; the only remaining nucleic acid is the 32P-labeled candidate adenosine nucleotide linked to the DNA oligo. This 32P-labeled product is purified on denaturing gels, and digested with another nuclease to obtain two 32P-labeled products, 5′p-A and 5′p-m6A which are separated by thin-layer chromatography and visualized by phosphorimaging. SCARLET not only can detect the presence of m6A, it also determines the modification fraction of that site which has not been possible using m6A-antibody based techniques.

M6A writers

The first m6A-methyltransferase identified is the protein encoded by the METTL3 gene 33. This gene is conserved from mammals to yeast. Knockdown or deletion of METTL3 led to a wide range of phenotypes such as apoptosis in human cell lines, viability in plants and drosophila, or sporulation defects in yeast 17, 34-36.

Recent studies discovered another human methyltransferase-like 14 (METTL14) protein that can also catalyze m6A RNA methylation, and the METTL14 protein forms a stable heterodimer complex with METTL3 37. Both METTL3 and METTL14 belong to the same methyltransferase superfamily; they are 43% identical in their primary sequences. Knockdown of either METTL3 or METTL14 leads to a marked decrease of m6A content in mRNA and causes mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) to lose their self-renewal capability 38. Both METTL3 and METTL14 are catalytically active in vitro in the methylation of single stranded RNA oligo substrates. These results indicate that both proteins are catalytic subunits of the complex. Each enzyme may methylate a distinct and overlapping set of m6A sites.

The METTL3-METTL14 core complex has been found to interact with WTAP 37, 39. WTAP is a protein known to be involved in mRNA splicing 40. siRNA knockdown of WTAP also leads to a significant decrease of m6A content, but WTAP protein itself does not show any methyltransferase activity in vitro 37. These results indicate that WTAP acts as an accessory protein that may be needed to enhance the methyltransferase selectivity or for sub-nuclear localization of the methyltransferases 37, 39.

M6A erasers

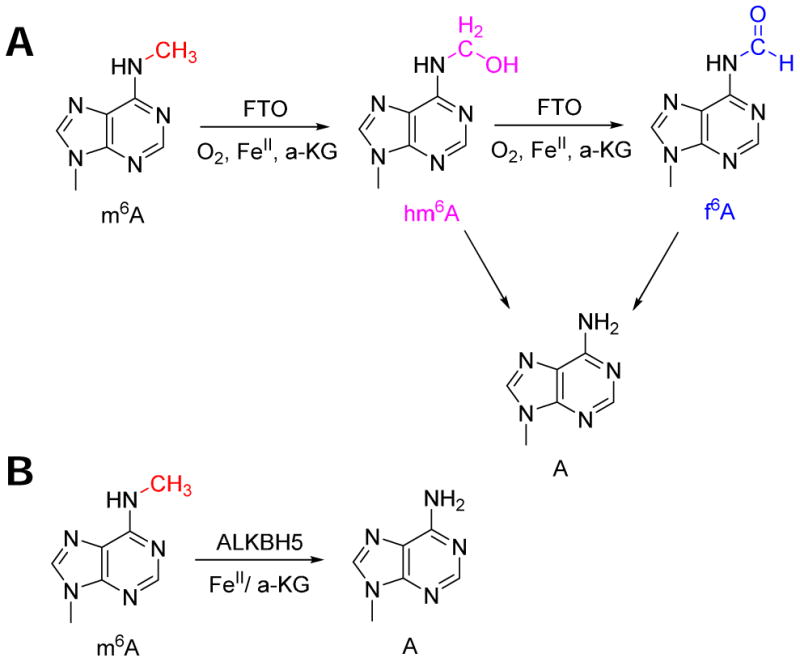

The first m6A eraser identified is the protein encoded by the FTO gene 19. FTO belongs to the family of Fe2+-α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenases and removes the methyl-group of m6A through successive oxidation (41, Fig. 3A). FTO overexpression led to a ∼15-20% reduction of m6A content, whereas siRNA knockdown of FTO lead to ∼20% increase of m6A content in human cell lines. FTO reaction generates two intermediate products, N6-hydroxymethyladenosine and N6-formyladenosine that are stable for several hours in the mammalian cell 41. These intermediates may be used to recruit specific proteins that recognize this particular chemical feature.

Fig. 3. Reaction mechanism of m6A erasers.

(A) FTO reaction generates two intermediates that are stable for several hours before its decomposition and reversal to adenosine. (B) ALKBH5 reaction directly removes the methyl-group from m6A.

Another m6A eraser known to date is the protein encoded by the ALKBH5 gene 42. ALKBH5 belongs to the same protein family as FTO. Other members in this family that have known cellular substrates include ALKBH2 for DNA methylation repair, ALKBH3 for RNA methylation repair, and ALKBH8 for hydroxylation of a specific human tRNAGly 43, 44. ALKBH5 directly removes the methyl-group of m6A without the accumulation of any detectable intermediate product (45, Fig. 3B).

M6A readers

Numerous mammalian proteins were found to preferentially bind a synthetic RNA oligo derived from Rous Sarcoma Virus genomic RNA with or without a specific m6A residue as bait 27. The three proteins detected with highest confidence include ELAVL1, YTHDF2 and YTHDF3. ELAVL1 or HuR (human antigen R) belongs to the ELAVL family of RNA binding proteins that contain several RNA-binding domains, and selectively bind cis-acting AU-rich elements (AREs) located in the 3′ UTR regions of mRNA 46. ELAVL1 is known to stabilize ARE-containing mRNAs 47, 48, and RNA-ELAVL1 interactions have been shown to regulate the stability of many mRNAs in embryonic stem cells in a m6A-dependent way 38. Both the YTHDF2 and YTHDF3 proteins belong to a superfamily of RNA binding proteins containing the YTH domain 49. The YTH domain is conserved in eukaryotes and is particularly abundant in plant genomes. Except for YTHDF2, further studies are needed to validate whether these proteins are authentic m6A readers in vivo.

A more recent study shows that the YTHDF2 protein directly recognizes m6A-modified RNA in vitro and in vivo 50. YTHDF2 protein binds a single-stranded RNA oligo containing a single m6A with ∼15-fold higher affinity for the modified RNA in vitro. YTHDF3 and another member of this family, YTHDF1 are also shown to prefer this m6A-containing RNA oligo by 5-20 fold in vitro. In human cell lines, YTHDF2 binds over 3,000 cellular RNA targets, most are located in mRNAs. YTHDF2 directly competes with ribosomes for translatable mRNA molecules in the cytoplasm. YTHDF2 binding results in mRNA localization to mRNA decay sites such as processing bodies. YTHDF2 is basically a triage factor for m6A-containing mRNA. When sufficient amounts of ribosomes are available, these mRNAs are bound by the ribosome for active translation, whereas decreasing amount of available ribosome enables their binding to YTHDF2 protein for targeted re-localization and degradation.

The YTHDF2 protein is made of two functional domains: one directly binds the m6A-modified RNA, and the other is required for mRNA localization within the cytoplasm 50. Among YTHDF1-3, the RNA binding domain is highly conserved, but the conservation of the other domain is far less pronounced. Therefore, these YTHDF proteins may affect mRNA metabolism in different ways, even though they can all interact with m6A-containing RNAs in a similar manner.

Since tens of thousands of m6A-sites have already been found, other m6A-reader proteins are certain to exist. Other m6A binding proteins may directly interact with the modified adenosine like YTHDF2, or they may indirectly sense m6A-modified RNA through changes in the RNA structure 51. The biological function of m6A modification is executed through their reader proteins. As more m6A-readers are identified, we anticipate a rapid growth in our understanding of how m6A affects all aspects of mRNA and lncRNA function.

M6A modification in human health and disease

The current knowledge on the writer, eraser and readers of m6A modification is summarized in Table 1. The m6A modification regulates a variety of biological processes and has been linked to numerous human diseases. Both m6A methyltransferases (METTL3 and METTL14) are crucial for cell development, and their depletion causes cell death. Diseases associated with METTL3 include prostatitis and aicardi syndrome, while diseases associated with METTL14 include alcohol dependence and alcoholism. The WTAP protein, known to affect mRNA splicing, is associated with Wilms tumor, kindney cancer, and other ailments. Variants within introns of m6A demethylase gene FTO have been indicated to increase risk for obesity and diabetes, although recent studies suggest that these variants within FTO introns form long-range functional connections with the homeobox gene IRX3 at the DNA level 52. Another identified m6A demethylases, ALKBH5, has been reported to affect Smith magenis syndrome, hypoxia and others. Except the still unclear biological role of YTHDF3, the three other identified m6A readers (YTHDF1, YTHDF2, ELAVL1) are related to mRNA stability. Diseases associated with the m6A readers include cancer, leukemia, hepatitis, Alzheimer's Disease, arthritis, prostatitis, hypoxia, pancreatitis and others.

Table 1. Human diseases associated with genes involved in m6A modification (Disease information from http://www.malacards.org/).

| Gene | Function | Phenotype | Associated Diseases | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| METTL3 | Methyltransferase | Apoptosis, development | Prostatitis, Aicardi Syndrome | 38, 59, 60 |

| METTL14 | Methyltransferase | Apoptosis, development | Alcohol dependence, Alcoholism | 38, 60 |

| WTAP | Scaffolding or localization | mRNA splicing | Wilms Tumor, Hypospadias, Sarcoma, Malignant Mesothelioma, Synovial Sarcoma | 34, 60-64 |

| FTO | Demethylase | Cellular energy homeostasis | Obesity, diabetes, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, Heart attack, Cancer, Alcoholism, Mental Disorders, Cataract, Hepatitis | 19, 65-71 |

| ALKBH5 | Demethylase | Male fertility | Hypoxia, Smith Magenis Syndrome | 45, 72 |

| YTHDF1 | m6A binding | mRNA stability | Pancreatic Cancer, Pancreatitis, Dermatomyositis | 50 |

| YTHDF2 | m6A binding | mRNA stability | Leukemia, Renal Cell Carcinoma, Breast Cancer | 27, 50, 73, 74 |

| YTHDF3 | m6A binding | N/A | N/A | 27, 50 |

| ELAVL1 | m6A binding | Apoptosis, mRNA stability | Cancer, Leukemia, Hepatitis, Anoxia, Alzheimer's Disease, Arthritis, Endotheliitis, Prostatitis, Hypoxia, Laryngitis, Keratoconus, Pancreatitis | 27, 38, 75-81 |

N/A: no available information.

RNA epigenetics beyond m6A in mRNA/lncRNA

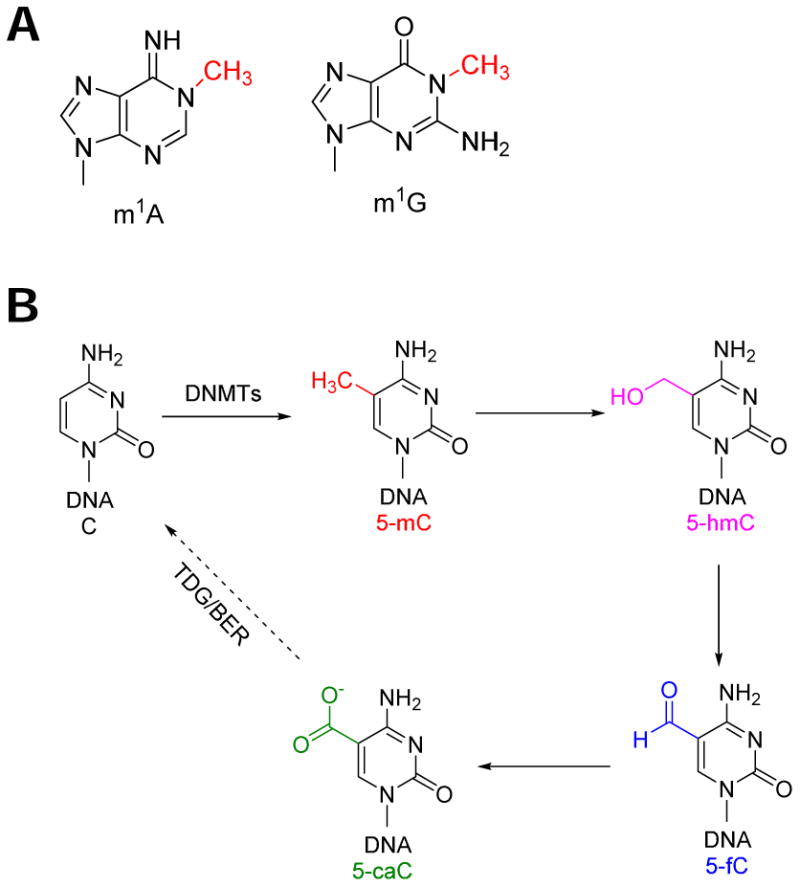

Most RNA methylations can be in principle reversed by another enzyme. In practice, the most likely candidates for reversal include m5C in mRNA and in tRNA 16, N1-methyl-A (m1A) in tRNA, and N1-methyl-G (m1G) in tRNA (Fig. 4A). m5C is the epigenetic marker of DNA and it can be reversed by the Tet1/Tet2 enzymes and the DNA repair enzyme thymine-DNA glycosylase (TDG; Fig. 4B, 53). A similar oxidative reversal pathway may also work for m5C modification in RNA, although the actual enzymes catalyzing such reactions in RNA have not yet been identified. m1A is present in almost every tRNA species in eukaryotes; it is required for the stability of some tRNAs 54, 55. The E. coli AlkB enzyme can reverse m1A in RNA when m1A modification was introduced by chemical methylation agents 56. An AlkB-like enzyme in a human cell may therefore potentially reverse endogenous m1A in some tRNAs to control their stability. m1G is present in about half of tRNA species in eukaryotes; it is needed for accurate decoding or for tRNA stability 57, 58. No natural enzyme is yet known that reverses m1G with high efficiency; however, m1G should be readily reversible based on its chemical feature.

Fig. 4. Other potentially reversible RNA methylations.

(A) m1A and m1G. (B) DNA m5C oxidative reversal pathway.

Finding reader proteins for these other methylatons, however, may be far more challenging. To our knowledge, RNA binding protein that directly recognizes m5C-modified mRNA has not yet been identified. For tRNAs, these modifications are generally used to control decoding accuracy and efficiency and to confer stability. It is unclear whether any reader protein is needed for their direct recognition. For now, m6A modification is clearly the prominent marker of RNA epigenetics.

Concluding remarks

Although mRNA modification has been known since the 1970s, its functional importance in mRNA metabolism and its effect on human biology have not been extensively studied in the past. The discovery of the m6A eraser protein FTO in 2011 directly links m6A modification in mRNA/lncRNA to human health and disease. Subsequent studies show that the m6A modification is connected to many aspects of human biology. The field of RNA epigenetics is still in its infancy. We look forward to many exciting discoveries in the coming years.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by an NIH EUREKA grant (GM88599 to T.P.).

Abbreviations

- m6A

N6-methyl adenosine

- m5C

5-methyl cytosine

- Nm

2′-O-methyl nucleotides

- rRNA

ribosomal RNA

- tRNA

transfer RNA

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- lncRNA

long non-coding RNA

Footnotes

We state that all authors have no potential conflicts of interest, have read the journal's policy on conflicts of interest, and have read the journal's authorship agreement.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Piekna-Przybylska D, et al. The 3D rRNA modification maps database: with interactive tools for ribosome analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D178–183. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El Yacoubi B, et al. Biosynthesis and Function of Posttranscriptional Modifications of Transfer RNAs. Annu Rev Genet. 2012;46:69–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grosjean H, et al. Deciphering synonymous codons in the three domains of life: co-evolution with specific tRNA modification enzymes. FEBS Lett. 2009;584:252–264. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song X, Nazar RN. Modification of rRNA as a 'quality control mechanism' in ribosome biogenesis. FEBS Lett. 2002;523:182–186. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02986-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agris PF. Decoding the genome: a modified view. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:223–238. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desrosiers R, et al. Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from Novikoff hepatoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974;71:3971–3975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams JM, Cory S. Modified nucleosides and bizarre 5'-termini in mouse myeloma mRNA. Nature. 1975;255:28–33. doi: 10.1038/255028a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei CM, et al. 5'-Terminal and internal methylated nucleotide sequences in HeLa cell mRNA. Biochemistry. 1976;15:397–401. doi: 10.1021/bi00647a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perry RP, et al. The methylated constituents of L cell messenger RNA: evidence for an unusual cluster at the 5' terminus. Cell. 1975;4:387–394. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei C, et al. N6, O2'-dimethyladenosine a novel methylated ribonucleoside next to the 5' terminal of animal cell and virus mRNAs. Nature. 1975;257:251–253. doi: 10.1038/257251a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narayan P, Rottman FM. An in vitro system for accurate methylation of internal adenosine residues in messenger RNA. Science. 1988;242:1159–1162. doi: 10.1126/science.3187541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horowitz S, et al. Mapping of N6-methyladenosine residues in bovine prolactin mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:5667–5671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.18.5667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harper JE, et al. Sequence specificity of the human mRNA N6-adenosine methylase in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5735–5741. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.19.5735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubin DT, Taylor RH. The methylation state of poly A-containing messenger RNA from cultured hamster cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1975;2:1653–1668. doi: 10.1093/nar/2.10.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaefer M, et al. RNA cytosine methylation analysis by bisulfite sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Squires JE, et al. Widespread occurrence of 5-methylcytosine in human coding and non-coding RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5023–5033. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bokar JA. The biosynthesis and functional roles of methylated nucleosides in eukaryotic mRNA. In: Grosjean H, editor. Fine-tuning of RNA functions by modification and editing. Springer-Verlag; 2005. pp. 141–178. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kariko K, et al. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity. 2005;23:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia G, et al. N6-Methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:885–887. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trewick SC, et al. Oxidative demethylation by Escherichia coli AlkB directly reverts DNA base damage. Nature. 2002;419:174–178. doi: 10.1038/nature00908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delaney JC, Essigmann JM. Mutagenesis, genotoxicity, and repair of 1-methyladenine, 3-alkylcytosines, 1-methylguanine, and 3-methylthymine in alkB Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14051–14056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403489101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frayling TM, et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science. 2007;316:889–894. doi: 10.1126/science.1141634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerken T, et al. The obesity-associated FTO gene encodes a 2-oxoglutarate-dependent nucleic acid demethylase. Science. 2007;318:1469–1472. doi: 10.1126/science.1151710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Church C, et al. A mouse model for the metabolic effects of the human fat mass and obesity associated FTO gene. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He C. Grand challenge commentary: RNA epigenetics? Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:863–865. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yi C, Pan T. Cellular dynamics of RNA modification. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:1380–1388. doi: 10.1021/ar200057m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dominissini D, et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. 2012;485:201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer KD, et al. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3' UTRs and near stop codons. Cell. 2012;149:1635–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz S, et al. High-resolution mapping reveals a conserved, widespread, dynamic mRNA methylation program in yeast meiosis. Cell. 2013;155:1409–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vilfan ID, et al. Analysis of RNA base modification and structural rearrangement by single-molecule real-time detection of reverse transcription. J Nanobiotechnology. 2013;11:8. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-11-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harcourt EM, et al. Identification of a selective polymerase enables detection of n(6)-methyladenosine in RNA. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:19079–19082. doi: 10.1021/ja4105792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu N, et al. Probing N6-methyladenosine RNA modification status at single nucleotide resolution in mRNA and long noncoding RNA. RNA. 2013;19:1848–1856. doi: 10.1261/rna.041178.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bokar JA, et al. Purification and cDNA cloning of the AdoMet-binding subunit of the human mRNA (N6-adenosine)-methyltransferase. RNA. 1997;3:1233–1247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhong S, et al. MTA is an Arabidopsis messenger RNA adenosine methylase and interacts with a homolog of a sex-specific splicing factor. Plant Cell. 2008;20:1278–1288. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.058883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clancy MJ, et al. Induction of sporulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae leads to the formation of N6-methyladenosine in mRNA: a potential mechanism for the activity of the IME4 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4509–4518. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hongay CF, Orr-Weaver TL. Drosophila Inducer of MEiosis 4 (IME4) is required for Notch signaling during oogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14855–14860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111577108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, et al. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:93–95. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, et al. N-methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:191–198. doi: 10.1038/ncb2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ping XL, et al. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res. 2014;24:177–189. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horiuchi K, et al. Wilms' tumor 1-associating protein regulates G2/M transition through stabilization of cyclin A2 mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17278–17283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608357103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fu Y, et al. FTO-mediated formation of N6-hydroxymethyladenosine and N4-formyladenosine in mammalian RNA. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1798. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng G, et al. ALKBH5 Is a Mammalian RNA Demethylase that Impacts RNA Metabolism and Mouse Fertility. Mol Cell. 2012;49:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang CG, et al. Crystal structures of DNA/RNA repair enzymes AlkB and ABH2 bound to dsDNA. Nature. 2008;452:961–965. doi: 10.1038/nature06889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van den Born E, et al. ALKBH8-mediated formation of a novel diastereomeric pair of wobble nucleosides in mammalian tRNA. Nat Commun. 2011;2:172. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng G, et al. ALKBH5 Is a Mammalian RNA Demethylase that Impacts RNA Metabolism and Mouse Fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma WJ, et al. Cloning and characterization of HuR, a ubiquitously expressed Elav-like protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8144–8151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kedde M, Agami R. Interplay between microRNAs and RNA-binding proteins determines developmental processes. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:899–903. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.7.5644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kundu P, et al. HuR protein attenuates miRNA-mediated repression by promoting miRISC dissociation from the target RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5088–5100. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stoilov P, et al. YTH: a new domain in nuclear proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:495–497. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang X, et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature. 2014;505:117–120. doi: 10.1038/nature12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pan T. N6-methyl-adenosine modification in messenger and long non-coding RNA. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38:204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smemo S, et al. Obesity-associated variants within FTO form long-range functional connections with IRX3. Nature. 2014;507:371–375. doi: 10.1038/nature13138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ito S, et al. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science. 2011;333:1300–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1210597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson J, et al. The Gcd10p/Gcd14p complex is the essential two-subunit tRNA(1-methyladenosine) methyltransferase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5173–5178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090102597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saikia M, et al. Genome-wide analysis of N-1-methyl-adenosine modification in human tRNAs. Rna-a Publication of the Rna Society. 2010;16:1317–1327. doi: 10.1261/rna.2057810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ougland R, et al. AlkB restores the biological function of mRNA and tRNA inactivated by chemical methylation. Mol Cell. 2004;16:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bjork GR, et al. Prevention of translational frameshifting by the modified nucleoside 1-methylguanosine. Science. 1989;244:986–989. doi: 10.1126/science.2471265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jackman JE, et al. Identification of the yeast gene encoding the tRNA m1G methyltransferase responsible for modification at position 9. RNA. 2003;9:574–585. doi: 10.1261/rna.5070303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bujnicki JM, et al. Structure prediction and phylogenetic analysis of a functionally diverse family of proteins homologous to the MT-A70 subunit of the human mRNA:m(6)A methyltransferase. J Mol Evol. 2002;55:431–444. doi: 10.1007/s00239-002-2339-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Niu Y, et al. N6-methyl-adenosine (m6A) in RNA: an old modification with a novel epigenetic function. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2013;11:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ortega A, et al. Biochemical function of female-lethal (2)D/Wilms' tumor suppressor-1-associated proteins in alternative pre-mRNA splicing. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3040–3047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Utsch B, et al. Exclusion of WTAP and HOXA13 as candidate genes for isolated hypospadias. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2003;37:498–501. doi: 10.1080/00365590310014517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Su J, et al. Evaluation of podocyte lesion in patients with diabetic nephropathy: Wilms' tumor-1 protein used as a podocyte marker. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jin DI, et al. Expression and roles of Wilms' tumor 1-associating protein in glioblastoma. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:2102–2109. doi: 10.1111/cas.12022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zeggini E, et al. Replication of genome-wide association signals in UK samples reveals risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Science. 2007;316:1336–1341. doi: 10.1126/science.1142364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kalnina I, et al. Polymorphisms in FTO and near TMEM18 associate with type 2 diabetes and predispose to younger age at diagnosis of diabetes. Gene. 2013;527:462–468. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Akilzhanova A, et al. Genetic profile and determinants of homocysteine levels in Kazakhstan patients with breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:4049–4059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reddy SM, et al. Clinical and genetic predictors of weight gain in patients diagnosed with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:872–881. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karra E, et al. A link between FTO, ghrelin, and impaired brain food-cue responsivity. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3539–3551. doi: 10.1172/JCI44403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lin Y, et al. Association between variations in the fat mass and obesity-associated gene and pancreatic cancer risk: a case-control study in Japan. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:337. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang L, et al. Variant rs1421085 in the FTO gene contribute childhood obesity in Chinese children aged 3-6 years. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2013;7:e1–e88. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thalhammer A, et al. Human AlkB homologue 5 is a nuclear 2-oxoglutarate dependent oxygenase and a direct target of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) PLoS One. 2011;6:e16210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cardelli M, et al. A polymorphism of the YTHDF2 gene (1p35) located in an Alu-rich genomic domain is associated with human longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:547–556. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Heiliger KJ, et al. Novel candidate genes of thyroid tumourigenesis identified in Trk-T1 transgenic mice. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2012;19:409–421. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang W, et al. HuR regulates p21 mRNA stabilization by UV light. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:760–769. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.760-769.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li H, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced methylation of HuR, an mRNA-stabilizing protein, by CARM1. Coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44623–44630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206187200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee SJ, et al. Clinicopathological Implications of Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) L1 Capsid Protein Immunoreactivity in HPV16-Positive Cervical Cytology. Int J Med Sci. 2014;11:80–86. doi: 10.7150/ijms.5585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang H, et al. Methionine adenosyltransferase 2B, HuR, and sirtuin 1 protein cross-talk impacts on the effect of resveratrol on apoptosis and growth in liver cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:23161–23170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.487157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhu Z, et al. Cytoplasmic HuR expression correlates with P-gp, HER-2 positivity, and poor outcome in breast cancer. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:2299–2308. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0774-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang F, et al. Retinoic acid-induced HOXA5 expression is co-regulated by HuR and miR-130a. Cell Signal. 2013;25:1476–1485. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pang L, et al. Loss of CARM1 is linked to reduced HuR function in replicative senescence. BMC Mol Biol. 2013;14:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-14-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]