Abstract

Due to the urgency and seriousness of the loss of biological diversity, scientists from across a range of disciplines are urged to increase the salience and use of their research by policy-makers. Increased policy nuance is needed to address the science–policy gap and overcome divergent views of separate research and policy worlds, a view still relatively common among conservation scientists. Research impact considerations should recognize that policy uptake is dependent on contextual variables operating in the policy sphere. We provide a novel adaptation of existing policy approaches to evidence impact that accounts for non-evidentiary “societal” influences on decision-making. We highlight recent analytical tools from political science that account for the use of evidence by policy-makers. Using the United Kingdom’s recent embrace of the ecosystem approach to environmental management, we advocate analyzing evidence research impact through a narrative lens that accounts for the credibility, legitimacy, and relevance of science for policy.

Keywords: Context, Research impacts, Narrative Policy Framework, Ecosystem services, Converger, Diverger

Introduction

Ecological and environmental sciences are strongly motivated by narratives of the need to take urgent measures to halt environmental damage and conserve at-risk species, habitats, and ecosystems (Alcamo et al. 2005). The scale of potential problems such as biological diversity loss (Barnosky et al. 2011; Rudd 2011a) and catastrophic climate change (Weitzman 2011) puts an obligation on scientists engage in research that helps address the “most urgent needs of society” (Lubchenco 1998, p. 494). The message from within the science community is that scientists must approach research with clarity and direction, and consider its eventual impact on society (Owens 2005; Lawton 2007; Jenkins et al. 2012). Despite calls for scientific engagement in societal decisions, environmental scientists, like in other fields, often express dissatisfaction at their level of impact in the policy sphere (Robinson 2006).

The converse narrative is that policy-makers are saturated by information from multiple sources; traditional civil service advisory services, academic researchers, think-tanks, and social media all contribute to the deluge. Policy-makers juggle advice from social science, natural science, economic analyses, public opinion polls, as well as face pressure from interest groups and other departments. In this context, policy-maker time, attention, and energy are scarce resources that must be manipulated to affect policy change (Zahariadis 1999).

Emerging directions in research impact assessment seek to account for the non-evidentiary factors that influence evidence use in the policy process (Contandriopoulos et al. 2010). The uptake of scientific evidence by policy-makers, for instance, is heavily dependent on contextual variables like the receptivity of decision-makers, timing and problem relevance, and competing societal values that may not be readily shifted by the communication of evidence (Sarewitz 2004; Lawton 2007). Contextual factors can create “non-receptive settings for new ideas” or “more receptive contexts for more developed recognition” (Pettigrew 2011, p. 351). Of course, one could argue that this is a very old approach, going back to John Dewey (e.g., Bromley 2006). The challenge is to “decode the context and understand its impact on knowledge use” (Contandriopoulos et al. 2010, p. 468).

It is commonly assumed that greater connectivity, integration, and crossdisciplinary inclusion increase the likelihood of evidence, knowledge and concepts transferring from conservation science to influence decisions (Wittrock 1991; Gibbons 1994; Frederiksen et al. 2003). It follows that there is an obligation on researchers to increase the impact of conservation science (i.e., that decisions that lead to continued degradation of the environment are caused by incomplete or imperfectly communicated information, and that better provision of factual information leads to better decisions—Owens 2005; Lawton 2007; Daily et al. 2009). A narrow approach to the science–policy process fails to address non-evidentiary barriers in the form of the pre-existing beliefs, vested interests and public attitudes that may be as important as the research produced (Contandriopoulos et al. 2010).

As environmental problems are increasingly identified as socio-ecological in nature (Folke et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2007; Reid et al. 2010), consideration of public policy influences on evidence impact will become more important. We believe that conservation scientists can benefit from concise descriptive tools that map contextual factors that affect the use of their evidence in decision-making. For instance: what strategies do evidence-users adopt in their policy arguments (Radaelli et al. 2013); why can the same body of evidence be used in justification of divergent political positions (e.g., the recent badger-culling debate in the UK; see Woolhouse and Wood 2013); and what role do underlying motivations play in the advocacy of evidence-based narratives (Jones and McBeth 2010; Shanahan et al. 2011)?

We outline one policy approach, the Narrative Policy Framework (NPF) (Jones and McBeth 2010; Shanahan et al. 2011), that accords with recent awareness of the importance of “stories” in science communication (Leslie et al. 2013). We outline a novel adaptation of the NPF for the assessment of non-evidentiary “societal” influences on decision-making. A narrative framework of the effects of evidence on policy provides a foundation for fuller, context-dependent understanding of the knowledge mobilization process.

Background

We draw on the example of “ecosystem-based management” (EBM) in the UK (Lawton and Rudd 2013) to illustrate the development of an approach to evidence impact assessment with the NPF. EBM narratives were central to the Natural Environment White Paper. The White Paper (2011) provided a strategic government response to continued biological diversity loss, habitat fragmentation, and declining ecosystem quality in the UK (Lawton 2010). It took an “integrated approach” aiming for a “resilient ecological network” of well-functioning ecosystems and sustained economic growth within an ecosystem service paradigm.

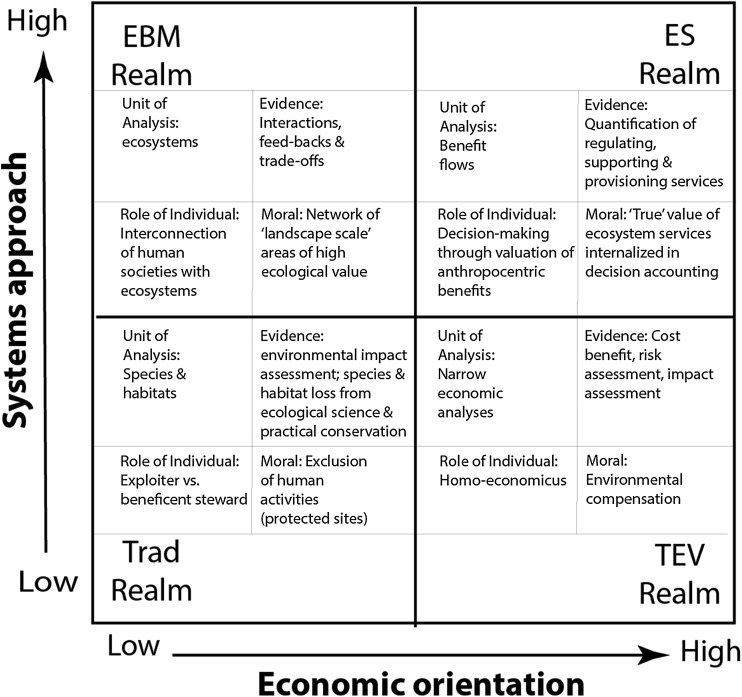

The UK example could point toward two alternative and potentially conflicting policy responses: an EBM narrative that seeks to preserve the natural world by increasing coherence, resilience and integrity of natural systems (e.g., Grumbine 1994); and an “ecosystem services” (ES) narrative that that emphasizes the delivery of anthropogenic benefits flowing from the services natural capital assets that support them (Daily et al. 2009), perhaps at the exclusion of those elements that do not contribute directly to human well-being, such as some aspects of biological diversity (Cardinale et al. 2012).

EBM is premised on the narrative that traditional scientific approaches to species and habitat protection have failed to arrest biological diversity loss (Lawton 2010). Conventional management has omitted the interactions of species as components in an interconnected ecosystem, and of coupled human societies and natural systems. The EBM narrative therefore focuses on evidence of ecosystem interconnections, functioning, and ecology (Lister 1998).

ES narratives aim to identify, catalog, and quantify the services on which natural and human systems rely so that they may be brought into societal decision-making processes. Evidence production focuses on quantifying the stocks and flows of benefits that ecosystems provide (Daily et al. 2009). ES narratives provide a powerful discursive tool in the communication of environmental degradation, driven by a desire for greater policy uptake of evidence leading to better decisions for the preservation of ecosystem features (Lawton and Rudd 2013). Figure 1 outlines differing underlying assumptions about unit of analysis, role of the individual, evidence-base and narrative morals between EBM, ES, traditional conservation, and cost–benefit total economic valuation (TEV) realms (adapted from Lawton and Rudd 2013).

Fig. 1.

Competing environmental management counter-narratives

Research Utilization

There are three main schools of thought within research utilization. One takes a traditional linear approach, where the influence of a piece of evidence can be directly quantified in economic or bibliographic terms (Griliches 1998). A second emphasizes diffuse impact, the gradual saturation of ideas of concept through the “agora” of the research community (Weiss 1979). The third focuses on networks or brokerage models that emphasize the personal bridging connections that individuals create between research and policy institutions (Oldham and McLean 1997).

Implicit in many of these accounts of research uptake are assumptions about the divergent nature of the research and policy worlds. Two important narrative streams within the research utilization literature were identified by Wittrock (1991). “Divergers” emphasize the need to “bridge” the gap between science and policymaking. They see the relational logics of science and politics as “incompatible” and either/or (Hoppe 2009, p. 237). Divergers typically follow linear narratives of instrumental impact, focused on the directly measurable impacts of a single evidence source. This position may be conceptualized as dichotomous, or zero sum, with evidence either having a direct and immediate influence on decision-making or having no impact at all (Beyer 1997). Many scientists that adhere to this logic may be advocates of “aligned research” (Rudd 2011b) if research impacts are viewed from a narrow perspective.

“Convergers” observe no policy gap. They believe science and politics ought to be “natural allies in preparing collective decisions” (Hoppe 2009, p. 235). In line with “Mode-Two” perspectives on research impacts (Gibbons 1994), convergers emphasize the fluid boundaries between research and policy communities, envisaging policy-makers involved from the earliest stages of research design and experts occupying decision-making positions (Frederiksen et al. 2003). The expert themselves may act as a stakeholder or their research output may be used independently by any number of divergent interests within the pluralist policy process.

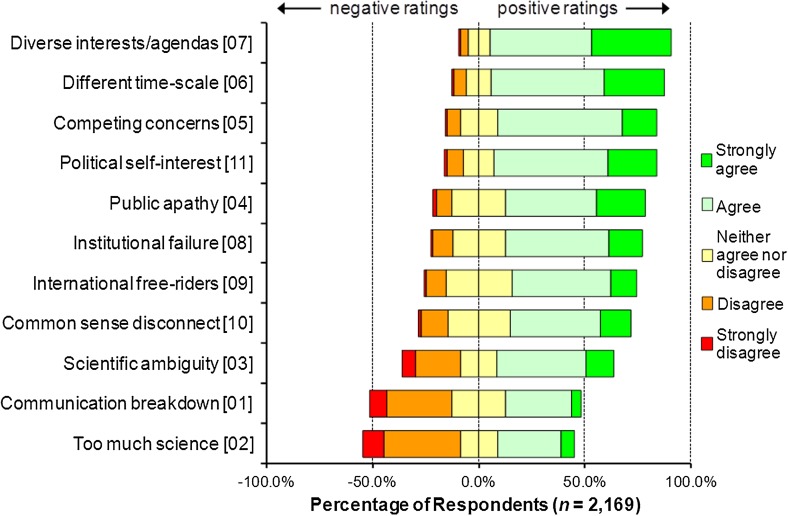

We posit that the diverger viewpoint still prevails in the conservation science community. Academic conferences ring with calls for policy to listen more to the scientific community, as if the role of the researcher is one of passive information supplier. Concurrently, “policy-making” is portrayed as a black-box, many-times removed from the world of research. For example, in a series of surveys of international environmental scientists (Fleishman et al. 2011; Rudd 2011a; Rudd and Lawton 2013 plus four M.Sc. student theses at University of York), we asked scientists’ level of agreement with 11 possible reasons proposed by Lawton (2007) for a lack of science uptake in environmental policy formulation and implementation. Among the 2169 scientists who completed surveys, we found high levels of agreement that the policy world operates on different time-scales, with different interests, and with a disconnect from science (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Level of agreement among journal authors (n = 2169) with a series of 11 possible reasons for a lack of science uptake in environmental policy formulation and implementation. The reasons include: 01 scientists are to blame: we are simply not getting the message across clearly enough; 02 there is too much science out there and politicians do not know where to go for the best or most relevant information; 03 the science is ambiguous and there are no clear answers; politicians use the uncertainty to avoid difficult decisions; 04 there is insufficient public support for what “ought” to be done, or politicians believe that there is insufficient electoral support for necessary actions that may threaten voters’ cherished lifestyles; 05 policy has to be formulated to take into account many other legitimate issues and constraints, not least the cost of various options; 06 scientists and policy-makers work to very different time-scales; 07 politicians are caught between the policy options that emerge from the science, and other powerful interest groups with different agendas; 08 there is “institutional failure”: we have the wrong decision-making bodies, poor (or no) “joined-up” government and contradictory policies in different parts of government; 09 policy solutions require bilateral or multilateral international agreements which are susceptible to free-riding and other types of cheating; 10 the scientific advice flies in the face of received political wisdom, dogma, or other deeply entrenched beliefs; and 11 some politicians are corrupt and out to look after personal interests. The statements were drawn from Lawton (2007)

In practice, decisions are made in a plural setting involving multiple autonomous and quasi-autonomous NGOs, think-tanks, and politically engaged scientists (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1993). While some academic writers show an awareness of the “messy, complex and iterative process” of evidence-based decision-making (Lawton 2007, p. 465), still too many err toward policy “gaps” and research “supply and demand.” Assessing the impact of a single evidence source ignores the additive effects provided by factors not traditionally considered, such as differential resources of time, attention, and network connections (Frederiksen et al. 2003). It also ignores the additive effect of multiple evidence sources acting together.

The challenge of taking a converger approach to the assessment of the effects of research on policy is that societal (political) decisions are multi-criteria in nature, characterized by diverse attributes, complex information, and fluid boundaries between actors (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1993). Impact cannot be attributed to the citations received by a single paper, or the economic returns from an individual invention or concept, since wider impact may be heavily context dependent upon the “receptive contexts” around a body of research (Pettigrew 2011, p. 351).

Narrative Policy Framework

In this paper, we highlight calls for a fourth approach to assessing the effect of research on policy (Contandriopoulos et al. 2010). We illustrate how existing tools from political science can be applied to assessments of research uptake to develop an analytical framework that accounts for non-evidentiary factors.

Work to date has focused on the effect of contextual factors in evidence utilization in the field of health policy. Both case study comparisons and focus groups have been used (e.g., Dobrow et al. 2006). Tummers et al. (2012) analyzed how different contextual factors influenced willingness to implement health policy. They focused on the “what” of policy content, the “where” of organizational context, and the “who” of personality characteristics of the professionals involved in implementation, and found that contextual variables had a significant effect on policy implementation (Tummers et al. 2012). Our approach assesses the “how” of policy development, captured in the strategic use of evidence through policy narrative analysis.

The NPF accounts for policy change by tracking the use of “strategic narratives” (Jones and McBeth 2010). Information is presented as stories in the policy process (Leslie et al. 2013). Dominant narratives are not only shifted by empirical evidence but also as a result of counter-narratives ability to “tell a better story” (Roe 1994, p. 40). Narrative studies provide coding guidance for analysis of policy subsystems (Jones and McBeth 2010; Shanahan et al. 2011). Narratives, stories, and plots are used by actors to structure causal explanations through construction of arguments, dramatic rhetorical devices, characters, and morals (Stone 2001). Standard narrative features can be organized around a set of evidence-specific themes of scientific credibility, societal legitimacy, and policy salience (relevance) (Cash et al. 2002). This provides multiple channels of influence for analysis. This can help make sense of the evidence–policy interface and identify how combinations of strategic narratives may affect policy change.

The influence of evidence-based narratives on policy is also dictated by their credibility, perceived legitimacy, and fairness (Cash et al. 2002). It follows that in multi-actor systems, narratives are accepted by groups depending on the extent to which they accord with their shared beliefs and policy motivations (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1993; Shanahan et al. 2011). This is less likely in conflicting and adversarial policy areas, such as climate change, where debate is driven by values and identity politics (Jasanoff and Wynne 1998). Finally, the relevance of evidence-based narratives depends on their relevance to decision-making bodies (Cash et al. 2002). Timeliness with the political agenda, appropriate technologies, and narrow research focus all influence the likelihood that evidence-based narratives enjoy policy traction (Lawton 2007).

Narrative Setting

In the NPF, the narrative setting is commonly the “policy arena” as perceived by actors within it. Typically this is the substantive or geographical area addressed by the policy (Jones and McBeth 2010). This provides the bounds for discursive analysis and qualitative coding (see below).

For example, in a preliminary analysis of the UK “Natural Environment White Paper” (hereafter “White Paper”) a delineated sample frame (authors of the White Paper, contributors to surrounding documents, and public consultees) provided the starting point for review of a body of evidence that influenced policy development (Lawton and Rudd 2013). This provided insights on evidence used in narratives around EBM and ES, as well as broader issues (e.g., level of government intervention and deficit reduction) salient to policy-makers. It found that difference in evidence-based narratives indicated a difference in underlying motivations between the research and policy communities in their support for EBM and ES outcomes (recall Fig. 1).

Current approaches to the evaluation of research on policy already encourage researchers to think ahead toward the extended societal impacts they expect of their work (Owens 2013). All too often this question asks researchers to stare into the unknown. Foresight and scoping of future potentialities require structure: prior experience and trends shape our expectations and bound the limits of the possible. New challenges, however, constantly arise (Weitzman 2011) and scientists need to creatively use their networks and knowledge to develop new solutions to emerging challenges (Latour 2013). Preliminary scoping of the policy setting to which evidence is destined still, however, serves an important purpose in framing expectations of research impact. It provides important feedback on policy gaps and evidence opportunities, and may help reshape research objectives. This should not be seen as an optional extra, but as an important step in crafting conservation science that meets the needs of society (Lubchenco 1998).

Characters

Actors are partly self-defined by their roles and partly characterized by others within policy narrative discourse (Stone 2001). Humans portray themselves and each other as archetypes: common characters include “heroes,” portrayed as fixers of the problem, “villains” who cause the problem, or “victims” (Jones and McBeth 2010). Empirical analysis of characterization narratives provides an indication of the degree of legitimacy policy narratives hold in the eyes of advocacy coalitions.

In the White Paper setting (2011), heroes differed between groups. Heroes within the academic community included well-connected scientific experts with a record of influencing policy. Conservationist heroes included ENGOs who advocated environmental protection while for centrist policy-makers heroes were pragmatic “fixers” who provided workable and salient solutions. Villains were characterized for blocking progress or the objectives of a particular group. Villains for those with conservation aims for the White Paper included politicians or interest groups with pro-development objectives, while for centrist or landowner groups villains sought to restrict economic growth through conservation interventions. Victims may include those groups suffering as a result of the problem, such as marginalized groups opposed to the commodification of ecosystem services (or indeed non-humans).

We also propose that an additional set of characters are needed specifically for understanding the processes by which evidence influences policy decisions. Entrepreneurs are seen as crucial in many models of policy change (Kingdon 1995). Entrepreneurs act as champions of an idea, evidence report, or policy issue. They apply their personal energy, network connections, and reputational resources in bringing an environmental issue to policy-maker attention (Zahariadis 1999). In the UK, for instance, entrepreneurship gathered around key evidence sources such as the UK National Ecosystem Assessment (2011) and the Lawton Review (Lawton 2010). “Charismatic experts” (Robert Watson, previous chair of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, and John Lawton, both eminent ecologists with a track record of policy success) enhanced the credibility and legitimacy of those reports and, by extension those strategically citing them for policy purposes. The wider expert author base associated with the research behind these reports was also a powerful surrogate for credibility. Concurrently, evidence documents gained extra salience through the industry, political resources, and personal connections provided by the evidence entrepreneur.

We believe that evidence–policy archetypes in the White Paper case are applicable other evidence–policy settings. The development and testing of science–policy “ideal types” drawn from empirical narrative analysis would contribute added nuance to the traditional divergent model of “researchers” and black-box “policy-makers” (Hoppe 2009).

Dramatic Rhetorical Resources

Dramatic narrative strategies are “used by policy actors to expand their power and ultimately win in the policy process” (Jones and McBeth 2010, p. 345). Evidence-based narratives may be “captured” by groups and institutions (Radaelli et al. 2013). Ecological narratives of heightened values from interconnected ecosystems, for instance, were mobilized by conservation groups as justification for “landscape scale” interventions (Lawton 2010). Once co-opted for political use, empirical content may be embedded within the broader body of evidence through “keystone documents” that synthesize and give narrative coherence to assembled facts and evidence.

Broader lessons can be drawn from the interactions of rhetoric, timing, and windows of opportunity with scientific evidence. The scientist rhetorician only became a thing of the past in the last century (Ashley-Smith 2000). At the point of engagement with other sectors of society—whether explained to a friend or formally presented to elected officials—scientific evidence becomes part of a story told to convince, enlighten, or persuade (Roe 1994). The problems faced by conservation scientists are increasingly understood to be interlinked and socio-ecological (Folke et al. 2007; Reid et al. 2010). Understanding rhetorical archetypes underlying societal decision-making is one component of this shift in knowledge production.

Policy Solutions (Moral of the Story)

Narrative morals provide the argumentative logic behind policy actor mobilization of evidence (Jones and McBeth 2010; Shanahan et al. 2011). The moral of the story in a policy narrative is often portrayed to prompt action and as a policy solution (Stone 2001).

Narrative strategies may be employed to increase the apparent concordance of counter-narrative morals to the core beliefs of another coalition. For instance, the “coupling” of ES narratives of economic evidence to EBM narratives of ecosystem value may be seen as a strategy for increasing the relevance of the EBM counter-narrative to government and decision-makers (Lawton and Rudd 2013). In this case, narratives of monetary quantification provide legitimacy for environmental conservation claims within centrist decision-making institutions, where economic narratives hold epistemic authority. Conversely, economic narratives may reduce the legitimacy of coupled EBM–ES solutions, because the objective of “capturing” policy audiences may raise doubts about the credibility of evidence-based narratives.

Robust, testable, repeatable evidence gathering and analysis is the core ontological motivation behind conservation science. However, it is clear that evidence is also used to frame messages behind sweeping narratives that encompass facts, values, interests, and aspirations (Jones and McBeth 2010; Shanahan et al. 2011). Convergent conservation science should operate with an appreciation that information is communicated through simple and memorable stories (Leslie et al. 2013). A divergent approach to science–policy impact makes no attempt to shape these morals (Wittrock 1991). A converger approaches them from a position of deeper knowledge than many other societal actors (Hoppe 2009).

Conclusion

The conservation of biological diversity is increasingly seen within an interconnected socio-ecological sphere (Folke et al. 2007). Evidence about complex ecological systems must be approached in combination with knowledge of human societies (Liu et al. 2007; Reid et al. 2010). Context-dependent understanding of the knowledge mobilization process provides a reflexive approach that accounts for non-scientific factors (Latour 2013). Implementation of the UK White Paper, for example, is likely dependent upon contextual factors like resource availability (financial, organizational, labor), resistance from coalitions with different policy objectives and priorities, and the unanticipated effects of concurrent policy measures being enacted in other sectors.

Existing approaches to understanding the knowledge mobilization process share a common core assumption that evidence content is the “central” input that impacts on research uptake, and that contextual factors are “peripheral” barriers to impact. Underlying this approach is a presumption in favor of evidence as the primary driver of societal decisions. We suggest that the reality, as seen from the “other side” of the science–policy gap, is that evidence is one of a set of equally important inputs into societal decisions. Greater understanding of this alternative perspective on the evidence–policy process can be explored in detail through an analysis of the discourse and narratives of actors involved in the decision-making process (Jones and McBeth 2010; Shanahan et al. 2011).

A converger approach to research impact assessment, on the other hand, places evidence within a broader set of considerations in a pluralist society (Hoppe 2009). Instead of the often intractable goal of aligning policy with research, this approach seeks a more comprehensive understanding of the variables at play in the decision-making process. It suggests that scientists are thoroughly enmeshed in the value adjudication processes needed to establish best practices (Rudd 2011b) where the conservation of biological diversity can be positively influenced (Jenkins et al. 2012). The goal is an empirical understanding of the actual, not imagined, place social and natural science evidence plays in each value-laden decision-making context.

How might we practically quantify converger or diverger propensities among scientists and policy-makers? While we cannot go into great detail in this article, we recently used a selection of significant items from Hoppe’s (2009) list of distinguishing statements as the basis for exploring differences in research orientation among scientists and natural resource management policy-makers in the USA (Lawton and Rudd, unpublished data). In the USA case, Rudd and Fleishman (2014) observed distinct differences in research orientation among scientists and policy-makers but, somewhat surprisingly (recall Lawton 2007), no significant differences in research orientation between the two groups (nor did any other professional or demographic covariates explain the differences). For scientists and policy-makers who participated in Rudd and Fleishman’s survey, we subsequently conducted an in-depth exploration of their attitudes to bridging science–policy interactions on a converger–diverger spectrum and were able to identify significant differences between convergers and divergers. More relevant for future research, however, we retained and modified (for clarity) the Hoppe (2009) items used in the USA survey and supplemented those with additional statements from the Hoppe list; some questions were also edited to remove potential ambiguity. Our abbreviated list of 12 distinguishing statements (Table 1) could be used in future research testing converger–diverger differences among or between scientists and policy-makers; we believe it could be valuable for researchers exploring the importance of political and social context, and decision-maker’s beliefs regarding science–policy interactions on conservation policy decisions.

Table 1.

Amended converger/diverger distinguishing statement list (based on Hoppe (2009) and unpublished data, Lawton and Rudd)

| No. | Statement | Conv./div. |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Worthwhile policy ideas emerge from science, but scientists have no responsibility for disseminating the policy implications of their research among policy-advising bureaucrats and politicians | D |

| 2 | No matter their differences, science and politics eventually serve a similar function creating conditions for cooperation between people. | C |

| 3 | It is admirable that scientists translate political ideas into transparent models, and objectify them into measurable indicators | C |

| 4 | The client or principal defines what knowledge is relevant | C |

| 5 | It is only natural for bureaucrats to collaborate with scientists; after all, research is a link in the chain of policy implementation | C |

| 6 | There will always be a political struggle about values; and correspondingly, types of knowledge that align with, or deviate from political value systems | C |

| 7 | In public policy, learning is limited to instrumental, financial and organizational matters | D |

| 8 | Dealing with uncertainty primarily is a matter of thorough and honest political debate | C |

| 9 | Most of the time it is concepts, models or story lines originating in science that are the glue in agreement on policy development issues | C |

| 10 | It is in the nature of things that politics and science are incompatible activities | D |

| 11 | When the chips are down, lay and practitioners’ knowledge have less value than scientific knowledge; therefore, they deserve no standing at the policy table | D |

| 12 | Scientific experts and advisers are lawyers: their business is advocacy for political positions | D |

Context is important and an NPF approach to account for it through preliminary analyses of policy settings, awareness of narrative archetypes, strategic narratives and rhetorical devices, and a willingness to engage in the currency of compelling stories and morals may help conservation scientists tell their story more effectively (Jones and McBeth 2010; Shanahan et al. 2011). Better decisions about the management and conservation of the natural world can only occur through better targeted, credible, and salient evidence (Cash et al. 2002). The creation of policy narratives and compelling morals is a vital task for conservation scientists (Leslie et al. 2013). We hope this article will both aid those conducting routine research impact assessments and stimulate new lines of thinking about the spectrum of approaches that can be used in conservation science to influence policy-making processes.

Acknowledgments

This research paper was supported by ESRC doctoral funding to RNL. We thank C. Burns and D. Raffaelli for comments on an earlier draft.

Biographies

Ricky N. Lawton

is a doctoral researcher in environmental policy at the University of York. His research explores the ways in which conservation science influences decision-making, with consideration to non-evidentiary contextual variables that exist in any policy-making system. His doctorate, sponsored by the UK Economics and Social Research Council, tests new methodological approaches to capturing research impact through national and international case studies, including natural capital accounting (UK) and natural resource management (USA). His research background is strongly interdisciplinary, including environmental economics, law, and history.

Murray A. Rudd

is a Senior Lecturer in environmental economics at the University of York. His research explores issues of when, where, and how to invest resources and craft policies to achieve ecological and socio-economic sustainability, enhance human well-being, and facilitate adaptation to environmental change. Much of his work is oriented toward the conservation of biological diversity in aquatic and marine realms. From a disciplinary perspective, he works at the intersection of public policy, economics, and ecology, with a focus on the science/policy interface. His doctorate (Wageningen) was in a joint program of rural policy & economics and the economics of consumers & households.

Contributor Information

Ricky N. Lawton, Email: ricky_lawton@hotmail.com

Murray A. Rudd, Phone: +44-1904-324063, FAX: +44-1904-322998, Email: murray.rudd@york.ac.uk

References

- Alcamo, J., D. van Vuuren, and W. Cramer. 2005. Changes in ecosystem services and their drivers across the scenarios. In Millennium ecosystem assessment ecosystems and human well-being: Scenarios (vol. 2, pp. 297–373). Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Ashley-Smith J. Science and art: Separated by a common language? V&A Conservation Journal. 2000;36:4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Barnosky AD, Matzke N, Tomiya S, Wogan GOU, Swartz B, Quental TB, Marshall C, et al. Has the Earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature. 2011;471:51–57. doi: 10.1038/nature09678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer JM. Research utilization: Bridging a cultural gap between communities. Journal of Management Inquiry. 1997;6:17–22. doi: 10.1177/105649269761004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bromley DW. Sufficient reason: Volitional pragmatism and the meaning of economic institutions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale BJ, Duffy JE, Gonzalez A, Hooper DU, Perrings C, Venail P, Narwani A, Mace GM, Tilman D, Wardle DA. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature. 2012;486:59–67. doi: 10.1038/nature11148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash, D, W. C. Clark, F. Alcock, N. M. Dickson, N. Eckley, and J. Jäger. 2002. Salience, credibility, legitimacy and boundaries: Linking research, assessment and decision-making. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 372280. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network.

- Contandriopoulos D, Lemire M, Denis JL, Tremblay É. Knowledge exchange processes in organizations and policy arenas: A narrative systematic review of the literature. Milbank Quarterly. 2010;88:444–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daily, G.C., S. Polasky, J. Goldstein, P.M. Kareiva, H.A. Mooney, L. Pejchar, T.H. Ricketts, J. Salzman, et al. 2009. Ecosystem services in decision-making: Time to deliver. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 7: 21–28. doi:10.1890/080025.

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) The natural choice: Securing the value of nature. London, UK: Natural Environment White Paper; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrow MJ, Goel V, Lemieux-Charles L, Black NA. The impact of context on evidence utilization: A framework for expert groups developing health policy recommendations. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63:1811–1824. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleishman E, Blockstein DE, Hall JA, Mascia MB, Rudd MA, Scott JM, Sutherland WJ, et al. Top 40 priorities for science to inform US conservation and management policy. BioScience. 2011;61:290–300. doi: 10.1525/bio.2011.61.4.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Folke C, Pritchard L, Berkes F, Colding J, Svedin U. The problem of fit between ecosystems and institutions: Ten years later. Ecology and Society. 2007;12:30. [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen F, Hansson F, Wenneberg S. The Agora and the role of research evaluation. Evaluation. 2003;9:149–172. doi: 10.1177/1356389003009002003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons M. The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. London: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Griliches Z. Issues in assessing the contribution of research and development to productivity growth. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Grumbine RE. What is ecosystem management? Conservation Biology. 1994;8:27–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1994.08010027.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe R. Scientific advice and public policy: Expert advisers’ and policymakers’ discourses on boundary work. Poiesis & Praxis. 2009;6:235–263. doi: 10.1007/s10202-008-0053-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasanoff S, Wynne B. Science and decision making. In: Rayner S, Malone EL, editors. Human choice and climate change. Columbus, OH: Battelle Press; 1998. pp. 1–87. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins LD, Maxwell SM, Fisher E. Increasing conservation impact and policy relevance of research through embedded experiences. Conservation Biology. 2012;26:740–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2012.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MD, McBeth MK. A narrative policy framework: Clear enough to be wrong? Policy Studies Journal. 2010;38:329–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00364.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon JW. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. 2. New York, NY: Harper Collins; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Latour B. An inquiry into modes of existence. Harvard, BO: Harvard University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton JH. Ecology, politics and policy. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2007;44:465–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2007.01315.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton JH. Making space for nature: A review of England’s wildlife sites and ecological network. London: Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton RN, Rudd MA. Strange bedfellows: Ecosystem services, conservation science, and central government in the United Kingdom. Resources. 2013;2:114–127. doi: 10.3390/resources2020114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie HM, Goldman E, Mcleod KL, Sievanen L, Balasubramanian H, Cudney-Bueno R, Feuerstein A, et al. How good science and stories can go hand-in-hand. Conservation Biology. 2013;27:1126–1129. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister NE. A systems approach to biodiversity conservation planning. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 1998;49:123–155. doi: 10.1023/A:1005861618009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Dietz T, Carpenter SR, Alberti M, Folke C, Moran E, Pell AN, et al. Complexity of coupled human and natural systems. Science. 2007;317:1513–1516. doi: 10.1126/science.1144004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubchenco J. Entering the century of the environment: A new social contract for science. Science. 1998;279:491. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham G, McLean R. Approaches to knowledge-brokering. International Institute for Sustainable Development. 1997;23:06. [Google Scholar]

- Owens B. Research assessments: Judgement day. Nature. 2013;502:288–290. doi: 10.1038/502288a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens S. Making a difference? Some perspectives on environmental research and policy. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 2005;30:287–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2005.00171.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew AM. Scholarship with impact. British Journal of Management. 2011;22:347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Radaelli CM, Dunlop CA, Fritsch O. Narrating impact assessment in the European Union. European Political Science. 2013;12:500–521. doi: 10.1057/eps.2013.26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reid, W.V., D. Chen, L. Goldfarb, H. Hackmann, Y.T. Lee, K. Mokhele, E. Ostrom, et al. 2010. Earth system science for global sustainability: Grand challenges. Science 330: 916–917. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Robinson JG. Conservation biology and real-world conservation. Conservation Biology. 2006;20:658–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe E. Narrative policy analysis: Theory and practice. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MA. Scientists’ opinions on the global status and management of biological diversity. Conservation Biology. 2011;25:1165–1175. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2011.01772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MA. How research-prioritization exercises affect conservation policy. Conservation Biology. 2011;25:860–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2011.01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd, M.A., and E. Fleishman. 2014. Policymakers’ and scientists’ ranks of the top 40 priorities for science to inform resource-management policy in the United States. BioScience 64: 219–228.

- Rudd MA, Lawton RN. Scientists’ prioritization of global coastal research questions. Marine Policy. 2013;39:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier PA, Jenkins-Smith HC, editors. Policy change and learning: Advocacy coalition approach. Boulder, CO: Westview Press Inc.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sarewitz D. How science makes environmental controversies worse. Environmental Science & Policy. 2004;7:385–403. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2004.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan EA, Jones MD, McBeth MK. Policy narratives and policy processes. Policy Studies Journal. 2011;39:535–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00420.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stone D. Policy paradox: The art of political decision making. 2 Revised. New York: W. W. Norton & Co; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tummers L, Steijn B, Bekkers V. Explaining the willingness of public professionals to implement public policies: Content, context, and personality characteristics. Public Administration. 2012;90:716–736. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.02016.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UK National Ecosystem Assessment. 2011. The UK National Ecosystem Assessment Technical Report. Technical Report: Introduction to the UK National Ecosystem Assessment. UK National Ecosystem Assessment. Cambridge, UK: UNEP-WCMC.

- Weiss CH. The many meanings of research utilization. Public Administration Review. 1979;39:426–431. doi: 10.2307/3109916. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ML. Fat-tailed uncertainty in the economics of catastrophic climate change. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy. 2011;5:275–292. doi: 10.1093/reep/rer006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wittrock B. Social knowledge and public policy: Eight models of interaction. In: Wagner P, editor. Social sciences and modern states: National experiences and theoretical crossroads. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Woolhouse M, Wood J. Tuberculosis: Society should decide on UK badger cull. Nature. 2013;498:434. doi: 10.1038/498434a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahariadis N. The multiple streams framework: Structure, limitations and prospects. In: Sabatier PA 2nd, editor. Theories of the policy process. Boulder, CO: Westview Press Inc.; 1999. pp. 65–93. [Google Scholar]