Abstract

African Americans are admixed with genetic contributions from European and African ancestral populations. Admixture mapping leverages this information to map genes influencing differential disease risk across populations. We performed admixture and association mapping in 3300 African American current or former smokers from the COPDGene Study. We analyzed estimated local ancestry and SNP genotype information to identify regions associated with FEV1/FVC, the ratio of forced expiratory volume in one second to forced vital capacity, measured by spirometry performed after bronchodilator administration. Global African ancestry inversely associated with FEV1/FVC (p = 0.035). Genome-wide admixture analysis, controlling for age, gender, body mass index, current smoking status, pack-years smoked, and four principal components summarizing the genetic background of African Americans in the COPDGene Study, identified a region on chromosome 12q14.1 associated with FEV1/FVC (p = 2.1 × 10-6) when regressed on local ancestry. Allelic association in this region of chromosome 12 identified an intronic variant in FAM19A2 (rs348644) as associated with FEV1/FVC (p=1.76 × 10-6). By combining admixture and association mapping, a marker on chromosome 12q14.1 was identified as being associated with reduced FEV1/FVC ratio among African-Americans in the COPDGene Study.

Keywords: admixture mapping, lung function, COPD, African Americans

Introduction

Differences in spirometric measures of lung function between European Americans and African Americans are well documented. For example, spirometric reference values for lung function were derived for European Americans, African Americans, and Mexican Americans from more than 7,000 asymptomatic, lifelong non-smoking participants in the third National Health and Nutrition National Survey (NHANES III) [Hankinson, et al. 1999]. European Americans had higher mean FEV1 and FVC than the other racial/ethnic groups. It has been suggested that body habitus, particularly the smaller trunk - leg ratio in African Americans, could be partially responsible for these differences. Others have found “childhood disadvantage factors” during early life development, such as parental asthma, childhood asthma, respiratory infections during childhood, and maternal smoking to be significantly associated with lower FEV1 [Svanes, et al. 2010]. Svanes et al. also found lower lung function levels from childhood to be permanent, associated with a slightly larger decline in lung function with age, and greater risk for COPD. Similarly, our analysis of early-onset COPD in the first 2500 subjects from the COPDGene Study showed severe early-onset COPD was proportionally more frequent among African Americans compared to European Americans: 42% vs. 14%, (p < 0.0001) [Foreman, et al. 2011]. African American race, maternal COPD, female gender, and increasing pack-years of smoking all predicted early-onset COPD in these data.

Socio-environmental influences are important determinants of lung function, but there is also compelling evidence to suggest genetic contributions. Kumar et al. found African ancestry was inversely related to FEV1 and FVC in two population-based cohorts [Kumar, et al. 2010]. These investigators found adding genetically measured ancestry to the standard lung function prediction equations, rather than relying on self-identified race, reduced misclassification and resulted in the re-classification of asthma severity by ∼5%. Higher vs. lower proportion of African ancestry, categorized as above or below the median value, has also been shown to be associated with greater decline in lung function per pack-year of smoking (-5.7 vs. -4.6 ml FEV1 per pack-year) in contrast to the -3.9 ml FEV1 per pack-year smoked seen among European Americans [Aldrich, et al. 2012]. Additionally, African Americans with higher proportions of African ancestry had greater risk of losing lung function while smoking.

Admixture mapping can identify novel genetic loci absent or not easily identifiable in Europeans due to low marker allele frequencies, which reduce the statistical power to detect associations [Shriner, et al. 2011]. Genetic admixture has been assessed and exploited analytically in studies of complex respiratory disorders such as lung cancer, sarcoidosis, and asthma [Choudhry, et al. 2008;Murray, et al. 2010; Rybicki, et al. 2011; Schwartz, et al. 2011;Torgerson, et al. 2012a;Torgerson, et al. 2012b; Vergara, et al. 2009]. Groundbreaking findings have resulted from admixture mapping followed by fine mapping or functional studies in chronic renal disease, prostate cancer, and systemic lupus erythematosus [Amundadottir, et al. 2006; Freedman, et al. 2006; Gudmundsson, et al. 2007; Haiman, et al. 2007; Kao, et al. 2008; Kopp, et al. 2008; Molineros, et al. 2013]. Some of these loci, originally detected via admixture mapping, have been shown to confer risk to multiple disorders or to suggest some selection pressure[Ahmadiyeh, et al. 2010; Genovese, et al. 2010; Pomerantz, et al. 2009]. Due to racial differences in lung function, racial differences in the prevalence of COPD between African and European Americans, and data suggesting African Americans develop COPD at younger ages with less cumulative smoking exposure [Chatila, et al. 2006; Chatila, et al. 2004], we hypothesized admixture mapping could identify novel markers related to the spirometric lung function phenotypes defining COPD.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

We analyzed phenotypic and genetic data from 3300 African-American research volunteers participating in the Genetic Epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) Study. The study protocol for COPDGene has been described elsewhere [Regan, et al.]. Briefly, self-identified non-Hispanic African-Americans and non-Hispanic European Americans between the ages of 45 and 80 years with a minimum history of 10 pack-years of smoking were enrolled in this multi-site study to investigate the genetic and environmental etiology of COPD. Subjects completed detailed questionnaires, pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry, volumetric computed tomography (CT) of the chest, and provided a DNA sample for genotyping. All participants provided written informed consent as approved by local institutional review boards.

Phenotypes

The following quantitative phenotypes related to clinical COPD were analyzed for admixture association: 1) the ratio of forced expiratory volume in one second to forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC), and 2) forced expiratory volume in one second as a percent of predicted (FEV1 % predicted). After taking in a maximal deep breath, FEV1 is the amount of air forcefully exhaled in one second. FEV1 % predicted is calculated using race and gender-specific regression models based on age, age2, and height2 [Hankinson, et al. 1999]. Forced vital capacity (FVC) is calculated from the same maneuver, but the maximal exhalation is expected to last 6 seconds or greater. The ratio of these two measurements, FEV1/FVC, defines airflow obstruction when values are <0.7. FEV1 % predicted is used to gauge the severity of airflow obstruction [Vestbo, et al. 2013]. Spirometric measurements were obtained in a standardized fashion before and after administration of inhaled albuterol, a bronchodilator medication. Spirometry was performed using the ndd EasyOne Spirometer (Zurich, Switzerland). Post-bronchodilator measurements of FEV1 and FEV1/FVC were used in these analyses. Final analyses were performed on 3260 study participants meeting spirometric quality control.

Genotyping and quality control

COPDGene subjects were genotyped using the Illumina Omni Express BeadChip containing 733,200 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Ninety samples were excluded from the analysis for the following reasons: genotyping call rate <98.5% (n = 2), subject relatedness determined by estimated IBD sharing in PLINK (>0.125) (n = 76), mismatched gender and/or race (n = 7), and sample duplication (n = 5). Principal components analysis revealed none of the 3300 African-American subjects fell more than 6 standard deviations from the mean of principal component 1 or 2. We excluded SNPs with minor allele frequencies (MAF) <1%, missingness >5% if the MAF was >5%, or missingness >2% if MAF <5%, p<0.0001 in a test for deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium within racial group, and concordance <99% in duplicate samples. After quality control, 608,923 autosomal SNPs remained available for admixture association analysis. The COPDGene genotyping quality control protocol is described at http://www.copdgene.org/sites/default/files/GWAS_QC_Methodology_20121115.pdf.

Local Ancestry Estimation

We inferred locus-specific genetic ancestry using the Local Ancestry in Admixed Populations (LAMP-LD) program [Baran, et al. 2012]. This program estimates local ancestry using a hidden Markov model (HMM) algorithm comparing observed genotypes to haplotypes of pre-specified ancestral reference populations. We specified 15 HMM states and a window size of 50 SNPs to estimate admixture blocks. We modeled two-way admixture using 60 Hapmap CEU and 60 Hapmap YRI as reference ancestral populations. This procedure generated estimates of having 0, 1, or 2 African chromosomes at each SNP position. These local estimates were used in a genome-wide admixture analysis and averaged for each individual to give a global estimate of African ancestry for each subject.

Statistical Analysis

We tested for association between global African ancestry and two quantitative traits associated with COPD (FEV1/FVC and FEV1 % predicted) in linear regression models controlling for age, gender, body mass index (BMI), pack-years and current smoking status. Genome-wide ancestry association testing was performed by comparing the estimated number of African chromosomes in each admixture block carried by an individual. Age, gender, BMI, pack-years smoked, current smoking status, and the first four principal components were included as covariates in the regression model:

| (1) |

In addition, we expanded the genome-wide analysis to include the observed marker genotypes by fitting:

| (2) |

This allowed testing for the following: 1) effect of local ancestry adjusting for genotype and covariates, and 2) the effect of genotype adjusted for local ancestry and covariates. The significance threshold for the genome-wide admixture analysis was determined by dividing 0.05 by the number of local ancestry blocks estimated by LAMP-LD. The conventional level of significance for a genome-wide analysis of all SNPs would be 5 × 10-8. All analyses were conducted in R and Plink [2013; Purcell, et al. 2007].

Results

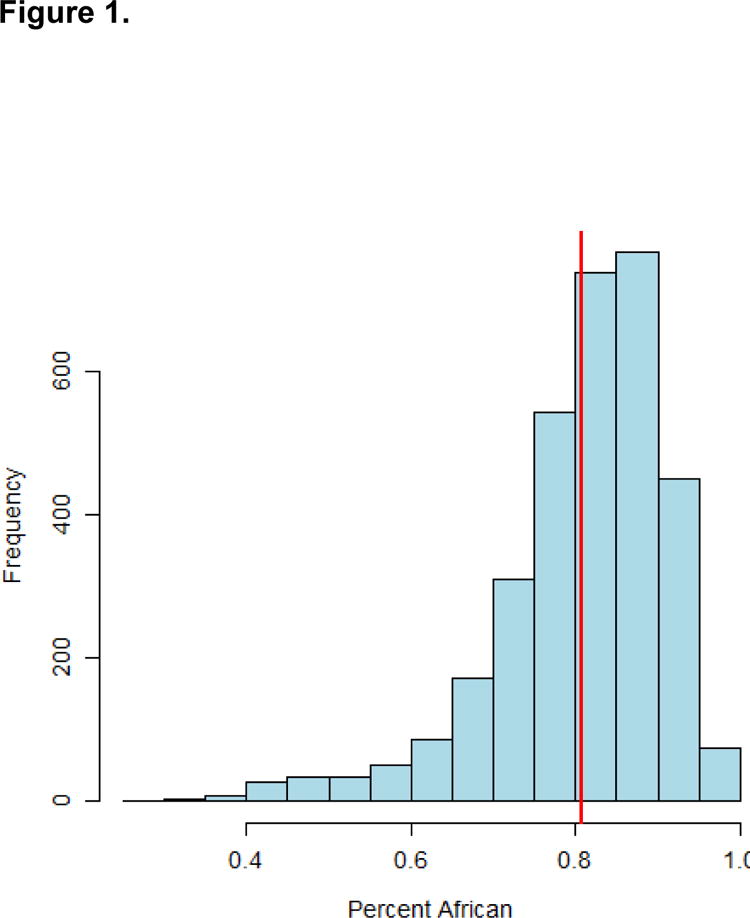

Demographic characteristics of the 3300 African American COPDGene subjects are displayed in Table 1. The average percent African ancestry among all 3300 African-American subjects was 80.8 ± 10.3%, with a range of 29.5 - 99.6% (Figure 1). Higher global African ancestry was significantly associated with lower FEV1/FVC (p=0.035) (Table 2).

Table 1. Characteristics of African-American Participants in the COPDGene Study.

| < 80.8% African(n=1365) | ≥ 80.8% African(n=1935) | Entire Cohort(n=3300) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age enrolled (mean) | 55.04 (0.20) | 54.42 (0.16) | 54.68 (0.13)** |

| Gender (% male) | 55.16 (NA) | 56.49 (NA) | 55.94 (NA) |

| BMI | 29.30 (0.18) | 28.88 (0.15) | 29.05 (0.12) |

| Pack-years smoked | 38.18 (0.56) | 38.42 (0.51) | 38.32 (0.38) |

| Current Smokers | 78.46 (NA) | 81.24 (NA) | 80.09 (NA) |

| FEV1/FVC (mean) | 0.72 (0.01) | 0.72 (0.01) | 0.72 (0.01) |

| FEV1 % predicted (mean) | 84.15 (0.67) | 80.07 (0.54) | 81.76 (0.42)# |

Values are presented as the mean (± sd) for all subjects and for subjects dichotomized by average African ancestry (80.8%)

p = 0.01

p < 0.001

Figure 1.

Distribution of global percent African Ancestry among all African-American COPDGene participants. Range = 29.5 - 99.6% African ancestry, mean ± sd = = 80.8 ± 10.3% (mean African ancestry is indicated with the vertical red line)

Table 2.

| Effect of global African ancestry on spirometric measures of lung function phenotypes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotypes | n | mean (SD) | beta* | p-value* | |

| FEV1/FVC | 3260 | 0.72 (0.14) | -0.04 | 0.035 | |

| FEV1 %predicted | 3260 | 81.77 (23.95) | -25.23 | <0.001 | |

| *Each phenotype was regressed on global ancestry in a linear model including age, gender, BMI, pack-years, and current smoking status as covariates. | |||||

| Table 2B. rs11174267 (FAM19A2), the most significant marker in the genomic region on 12q14.1 associated with local ancestry and FEV1/FVC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-values from linear regression of quantitative measure of pulmonary function on: 1) local ancestry association tests; 2) allelic association tests with correction for local ancestry; 3) allelic association tests in non-Hispanic, European American COPDGene subjects for comparison. | |||||

| Quantitative measure of pulmonary function | SNP | Nearest Gene | p-value for effect of 1) local ancestry | Allelic p-value 2) adjusting for local ancestry | Allelic p-value 3) in NHW |

| FEV1/FVC | rs11174267 | FAM19A2 | 1.81E-05 | 1.91E-06 | 0.76 |

| FEV1 % predicted | rs11174267 | FAM19A2 | 0.05 | 7.75E-05 | 0.88 |

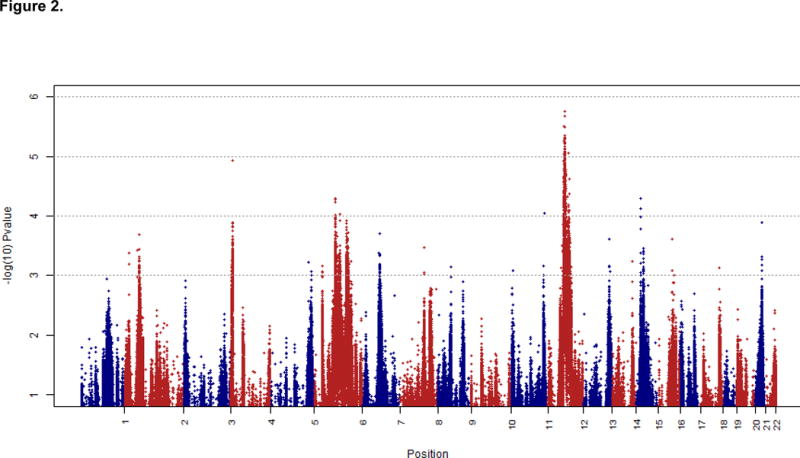

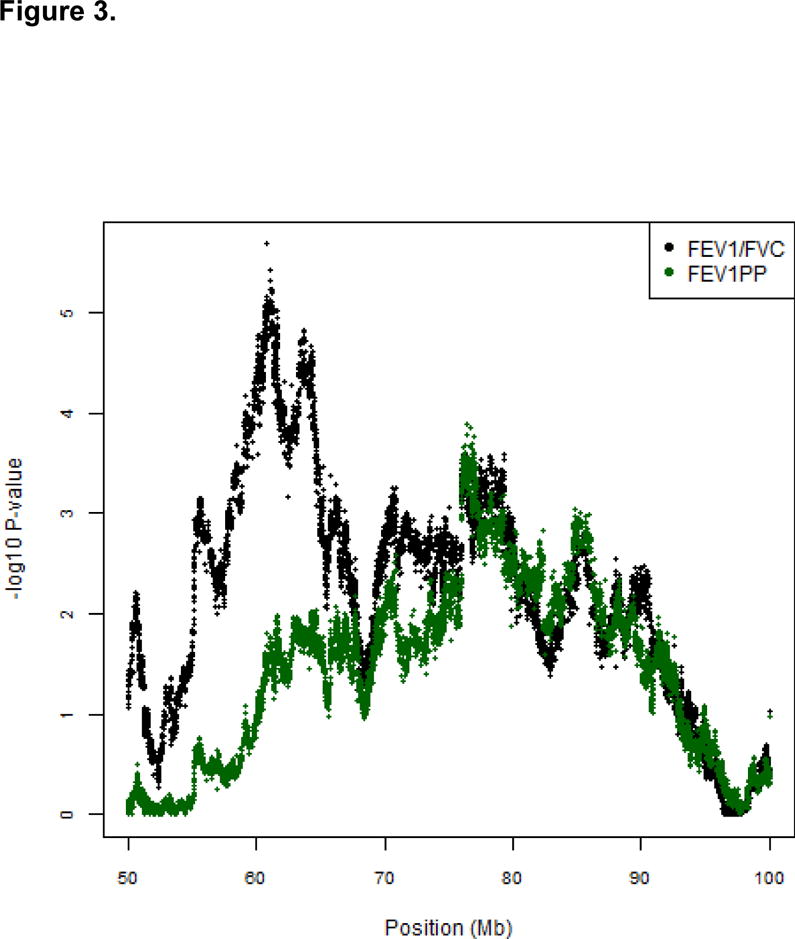

We performed 38,566 genome-wide admixture association tests for FEV1/FVC as displayed in the Manhattan plot in Figure 2. The most significant admixture association signal occurred with FEV1/FVC on chromosome 12q14.1 (p=2.1 × 10-6). After controlling for genotype (β2 from equation 2), the most significant individual SNP (rs348644) gave a p=1.76 × 10-6. Local African ancestry at this SNP was associated with a modest increase in FEV1/FVC (β=0.04 ± 0.0083). Near this admixture signal for FEV1/FVC, we also found an ancestry association with FEV1 % predicted (p=1.3×10-4). (Figure 3)

Figure 2.

Genome-wide admixture association analysis for FEV1/FVC. The X-axis represents genomic position by chromosome. The Y-axis represents –log10(p-value) for association between a quantitative measure of pulmonary function and local ancestry estimated from a linear regression controlling for age, gender, BMI, pack-years smoked, current smoking status, and the first four principal components (PC1-PC4).

Figure 3.

Admixture association results on chromosome 12 for FEV1/FVC and FEV1 % predicted based equation 1. The X-axis represents genomic position on chromosome 12 in megabases. The Y-axis represents −log10(p-value) for association between local ancestry estimated from a linear regression of FEV1/FVC (green) and FEV1 % predicted (black).

Because the threshold for statistical significance in admixture mapping is highly dependent on sample size and population, we performed genome-wide permutation testing, as an alternative evaluation of statistical significance, maintaining the haplotype structure while randomly shuffling the phenotypes. The empiric p-value from 10,000 permutations for the association between rs348644 and FEV1/FVC was 0.0611 (95% CI 0.056 – 0.066), consistent with a family-wise error rate of approximately 6%.

We checked allelic associations from genome-wide analysis in and near this admixture signal. Controlling for local ancestry, age, gender, pack-years of smoking, current smoking, and four principal components, a nearby SNP (rs11174267), an intronic variant in FAM19A2 was associated with both FEV1/FVC (p=1.9 × 10-6) and FEV1 % predicted (p=7.9 × 10-5). The frequency of the G allele at this SNP in European-derived HapMap populations was 0.41 compared to 0.075 in Africans. Having one copy of the G allele reduced the mean FEV1/FVC by 0.02% (and reduced mean FEV1 % predicted by 3%). The frequency of this G allele increased with severity of COPD, as measured by GOLD stage (Table 3). This SNP was not associated with lung function in non-Hispanic white participants from the COPDGene study (FEV1/FVC, p=0.64; FEV1 % predicted, p=0.88).

Table 3. Distribution of the G allele for rs11174267 by COPD Severity.

| GOLD Stage | n | frequency |

|---|---|---|

| GOLD U | 501 | 0.24 |

| GOLD 0 (normal lung function) | 1796 | 0.25 |

| GOLD 1 (mild) | 178 | 0.32 |

| GOLD 2 (moderate) | 472 | 0.33 |

| GOLD 3 (severe) | 235 | 0.36 |

| GOLD 4 (very severe) | 111 | 0.39 |

GOLD = Global Initiative in Obstructive Lung Disease [Vestbo, et al. 2013]

GOLD U = unclassified (FEV1 < 0.8, FEV1/FVC > 0.7) [Wan, et al. 2011]

Similar to Zhu et al., we determined whether the most significant SNP in our region of interest accounted for the observed admixture signal by adjusting for this SNP in the linear regression equation modeling local ancestry association [Zhu, et al. 2011]. For FEV1/FVC, adjusting for rs11174267 (the most significantly associated SNP) ameliorated the statistical evidence for ancestry association. Specifically, β = 0.0353 (s.e. = 0.0082) in the model with local ancestry alone, but in the model with local ancestry adjusting for rs11174267 genotype, β = 0.0234 (s.e. = 0.0086). The estimated effect size for this SNP controlling for local ancestry was β = -0.0219 (s.e. = 0.0046). Additionally, to determine whether the association with lung function was due to differential responsiveness to bronchodilation from albuterol vs. a primary process, we performed the same analyses with pre-bronchodilator spirometric measures. Again, genotype at rs11174267 was significantly associated with pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC, p = 2.52 × 10-8.

Discussion

Using admixture and association mapping, we found association between quantitative, spirometric measures of lung function and a novel region on chromosome 12q14.1. Our strongest admixture association was seen with post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC, which is part of the definition of COPD under the widely accepted GOLD criteria, where post bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.7 defines chronic airflow obstruction [Vestbo, et al. 2013]. Estimated local African ancestry at rs348644, an intronic marker of FAM19A2 was associated with post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC (p = 2.1 × 10-6) when regressed on local ancestry alone and was associated with increased post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC (β = 0.0362). Interestingly, pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC is genome-wide significant (p = 2.52 × 10-8) and post-bronchodilator is only nominally significant (p=1.91×10-6), a difference that is unexplained. Though the use of post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC reduces overestimation of the diagnosis of COPD and may correlate with COPD mortality, differences between pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry generally lessen as severity of COPD increases [Chen, et al. 2012; Mannino, et al. 2011; Tashkin, et al. 2013]. Our findings may have been influenced by the lesser frequency of African Americans with severe COPD in this cohort.

The most appropriate level of genome-wide significance for admixture mapping remains undecided [Sha, et al. 2006; Zhu, et al. 2006], because the number of tests and the correlation between markers and blocks of local ancestry must be considered rather than simply the total number of SNPs. Qin and Zhu suggest a two-stage approach, admixture mapping followed by single SNP association testing, is more powerful than the standard genome-wide association analysis when the allele frequency difference of an unobserved causal variant between the ancestral populations is above 0.4 [Qin and Zhu 2012]. With a simple Bonferroni correction, we conservatively estimated genome-wide significance for local ancestry to be 1.2 × 10-6 (0.05 ÷ 38,566 admixture tests). We would expect the genome-wide significance level for ancestry analysis to be lower than for a traditional genome-wide association analysis of SNPs due to the extensive correlation in estimated local ancestry for adjacent markers reflecting relatively recent admixture (10 – 12 generations among African Americans).

Family with sequence similarity 19 (chemokine (C-C motif)-like, member A2, abbreviated as FAM19A2, is a member of the TAFA family of five homologous genes encoding small, secreted proteins thought to be regulators of immune and nerve cells (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/338811). A SNP in FAM19A2, rs7960162, was one of eleven replicated associations as genetic risk factors for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [Lessard, et al. 2012], though none exceeded genome-wide significance in this study. Lessard et al. chose to replicate 1580 markers with p<0.05 from a prior genome-wide scan of European Americans [Graham, et al. 2008] in a multi-racial replication population. Admixture mapping has been quite fruitful in the study of SLE, as this disorder is more common and more severe in individuals of African ancestry. This approach has led to the identification of several functional variants influencing risk to SLE [Molineros, et al. 2013; Petri 2002].

Several large consortia have performed meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies and identified multiple loci associated with lung function [Hancock, et al. 2012; Hancock, et al. 2010; Repapi, et al. 2010]. These population-based studies of pre-bronchodilator FEV1 and FEV1/FVC were performed in essentially healthy individuals of European ancestry. A SNP (rs4382947, p=3.1 × 10-4) in SLC16A7 was among the top 2000 SNPs reported by Hancock et al.[Hancock, et al. 2010]. This gene is located under our admixture peak for FEV1/FVC on chromosome 12. (Supporting Information, Table 3) Subsequent tests of 6 genetic markers previously associated with lung function were performed to evaluate joint effects on lung function and COPD[Soler Artigas, et al. 2011b]. A more recent meta-analysis of 23 genome-wide lung function studies analyzing approximately 48,000 individuals of European ancestry identified 16 additional loci[Soler Artigas, et al. 2011a]. We accessed data from this study via GWAS Central (http://www.gwascentral.org/index) to identify allelic associations with FEV1/FVC near FAM19A2. The most significantly associated SNP was rs7315138, an intronic variant in FAM19A2 (p= 0.0093). We also identified other allelic associations with FEV1/FVC in the area of our admixture peak, finding association with rs1690139, an intergenic SNP (p= 0.0039) in this European-derived cohort. Though these newly detected variants may lead to the discovery of novel molecular pathways controlling lung function, these studies could have missed variants only detectable in the context of recent admixture. While there is no universal consensus on the most efficient strategy for admixture mapping, and several groups have suggested a two-stage approach where peak regions associated with estimated local ancestry become the primary focus[Qin and Zhu 2012; Torgerson, et al. 2012a]. Here we adopted a comprehensive search strategy where local ancestry effects were first fit followed by the full model (equation 2) with both local ancestry and SNP effects were considered.

Determinants of lung function in African Americans most likely represent complex interactions of genetic and environmental factors. Kalhan et al. confirmed lung function among young adults was predictive of lung function in later life [Kalhan, et al. 2010]. Van Sickle et al. evaluated socioeconomic status and lung function in a population based sample from NHANES III [Van Sickle, et al. 2011]. These authors found higher education to be associated with reduced risk for airflow obstruction in later life. High school completion was associated with greater improvement in lung function among European Americans compared to African Americans. There was a nearly 0.5L increase in FEV1 for European American males who completed high school compared to African Americans. College completion was associated with additional incremental improvement in FEV1 among European Americans. However, high school completion resulted in minimal improvement in lung function among African Americans. This study found socioeconomic status (measured by high school graduation) independently affected lung function, but race had even a greater effect on FEV1 [Wagner 2011].

Though we identified a novel locus associated with spirometric measures of lung function using admixture and association mapping in a well-characterized cohort of 3300 African Americans, our analysis has limitations. Our cohort is cross-sectional and ascertainment was limited to individuals with a history of heavy tobacco smoking (> 10 pack-years). This recruitment strategy, enriched for COPD cases, makes the generalizing from our findings difficult. Lacking functional data, inferences about causality are also not possible from these data alone. Additionally, these data require replication in an independent sample, an option limited by the lack of other large African American cohorts with lung function data derived specifically for the study of tobacco smoking and risk of COPD. Yet, here we demonstrate gene level replication for association between a marker in FAM19A2 and FEV1/FVC in Europeans and our study conclusions are based on two analytic approaches, admixture mapping and association mapping. Our findings suggest the potential for formal subsequent studies of autoimmunity, lung function, and COPD among African Americans [Leidinger, et al. 2009; Packard, et al. 2013].

Here, we report a quantitative trait locus for lung function phenotypes on chromosome 12q14.1 detected through combined use of ancestry and association mapping among African Americans from the COPDGene Study. The COPDGene Study was designed to identify genetic determinants of COPD in European Americans and African Americans; the latter group not having received sufficient attention in the past. Our findings are intriguing, but hypothesis generating. Given the paucity of data on African Americans with COPD, these findings are important and may be translatable to other groups. Further refinement of our findings will require fine mapping of this region, replication, and functional studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

NIH Grant Support and Disclaimer

The project described was supported by Award Number R01HL089897, R01HL089856, and K01HL092601 from the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Genome-wide permutation testing was performed by Ingo Ruczinski of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

References

- R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadiyeh N, Pomerantz MM, Grisanzio C, Herman P, Jia L, Almendro V, He HH, Brown M, Liu XS, Davis M, et al. 8q24 prostate, breast, and colon cancer risk loci show tissue-specific long-range interaction with MYC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(21):9742–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910668107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich MC, Kumar R, Colangelo LA, Williams LK, Sen S, Kritchevsky SB, Meibohm B, Galanter J, Hu D, Gignoux CR, et al. Genetic ancestry-smoking interactions and lung function in African Americans: a cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amundadottir LT, Sulem P, Gudmundsson J, Helgason A, Baker A, Agnarsson BA, Sigurdsson A, Benediktsdottir KR, Cazier JB, Sainz J, et al. A common variant associated with prostate cancer in European and African populations. Nature genetics. 2006;38(6):652–8. doi: 10.1038/ng1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baran Y, Pasaniuc B, Sankararaman S, Torgerson DG, Gignoux C, Eng C, Rodriguez-Cintron W, Chapela R, Ford JG, Avila PC, et al. Fast and accurate inference of local ancestry in Latino populations. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(10):1359–67. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatila WM, Hoffman EA, Gaughan J, Robinswood GB, Criner GJ. Advanced emphysema in African-American and white patients: do differences exist? Chest. 2006;130(1):108–18. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatila WM, Wynkoop WA, Vance G, Criner GJ. Smoking patterns in African Americans and whites with advanced COPD. Chest. 2004;125(1):15–21. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CZ, Ou CY, Wang WL, Lee CH, Lin CC, Chang HY, Hsiue TR. Using post-bronchodilator FEV(1) is better than pre-bronchodilator FEV(1) in evaluation of COPD severity. COPD. 2012;9(3):276–80. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2012.654529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry S, Taub M, Mei R, Rodriguez-Santana J, Rodriguez-Cintron W, Shriver MD, Ziv E, Risch NJ, Burchard EG. Genome-wide screen for asthma in Puerto Ricans: evidence for association with 5q23 region. Hum Genet. 2008;123(5):455–68. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0495-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman MG, Zhang L, Murphy J, Hansel NN, Make B, Hokanson JE, Washko G, Regan EA, Crapo JD, Silverman EK, et al. Early-onset chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with female sex, maternal factors, and African American race in the COPDGene Study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2011;184(4):414–20. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1928OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman ML, Haiman CA, Patterson N, McDonald GJ, Tandon A, Waliszewska A, Penney K, Steen RG, Ardlie K, John EM, et al. Admixture mapping identifies 8q24 as a prostate cancer risk locus in African-American men. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(38):14068–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605832103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, Lecordier L, Uzureau P, Freedman BI, Bowden DW, Langefeld CD, Oleksyk TK, Uscinski Knob AL, et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010;329(5993):841–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1193032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham RR, Cotsapas C, Davies L, Hackett R, Lessard CJ, Leon JM, Burtt NP, Guiducci C, Parkin M, Gates C, et al. Genetic variants near TNFAIP3 on 6q23 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2008;40(9):1059–61. doi: 10.1038/ng.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Manolescu A, Amundadottir LT, Gudbjartsson D, Helgason A, Rafnar T, Bergthorsson JT, Agnarsson BA, Baker A, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a second prostate cancer susceptibility variant at 8q24. Nat Genet. 2007;39(5):631–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haiman CA, Le Marchand L, Yamamato J, Stram DO, Sheng X, Kolonel LN, Wu AH, Reich D, Henderson BE. A common genetic risk factor for colorectal and prostate cancer. Nature Genetics. 2007;39(8):954–6. doi: 10.1038/ng2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock DB, Artigas MS, Gharib SA, Henry A, Manichaikul A, Ramasamy A, Loth DW, Imboden M, Koch B, McArdle WL, et al. Genome-wide joint meta-analysis of SNP and SNP-by-smoking interaction identifies novel loci for pulmonary function. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(12):e1003098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock DB, Eijgelsheim M, Wilk JB, Gharib SA, Loehr LR, Marciante KD, Franceschini N, van Durme YM, Chen TH, Barr RG, et al. Meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies identify multiple loci associated with pulmonary function. Nat Genet. 2010;42(1):45–52. doi: 10.1038/ng.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(1):179–87. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalhan R, Arynchyn A, Colangelo LA, Dransfield MT, Gerald LB, Smith LJ. Lung function in young adults predicts airflow obstruction 20 years later. Am J Med. 2010;123(5):468 e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao WH, Klag MJ, Meoni LA, Reich D, Berthier-Schaad Y, Li M, Coresh J, Patterson N, Tandon A, Powe NR, et al. MYH9 is associated with nondiabetic end-stage renal disease in African Americans. Nature Genetics. 2008;40(10):1185–92. doi: 10.1038/ng.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp JB, Smith MW, Nelson GW, Johnson RC, Freedman BI, Bowden DW, Oleksyk T, McKenzie LM, Kajiyama H, Ahuja TS, et al. MYH9 is a major-effect risk gene for focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nature Genetics. 2008;40(10):1175–84. doi: 10.1038/ng.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Seibold MA, Aldrich MC, Williams LK, Reiner AP, Colangelo L, Galanter J, Gignoux C, Hu D, Sen S, et al. Genetic ancestry in lung-function predictions. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(4):321–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leidinger P, Keller A, Heisel S, Ludwig N, Rheinheimer S, Klein V, Andres C, Hamacher J, Huwer H, Stephan B, et al. Novel autoantigens immunogenic in COPD patients. Respir Res. 2009;10:20. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessard CJ, Adrianto I, Ice JA, Wiley GB, Kelly JA, Glenn SB, Adler AJ, Li H, Rasmussen A, Williams AH, et al. Identification of IRF8, TMEM39A, and IKZF3-ZPBP2 as susceptibility loci for systemic lupus erythematosus in a large-scale multiracial replication study. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(4):648–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannino DM, Diaz-Guzman E, Buist S. Pre- and post-bronchodilator lung function as predictors of mortality in the Lung Health Study. Respir Res. 2011;12:136. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molineros JE, Maiti AK, Sun C, Looger LL, Han S, Kim-Howard X, Glenn S, Adler A, Kelly JA, Niewold TB, et al. Admixture mapping in lupus identifies multiple functional variants within IFIH1 associated with apoptosis, inflammation, and autoantibody production. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(2):e1003222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray T, Beaty TH, Mathias RA, Rafaels N, Grant AV, Faruque MU, Watson HR, Ruczinski I, Dunston GM, Barnes KC. African and non-African admixture components in African Americans and an African Caribbean population. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34(6):561–8. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard TA, Li QZ, Cosgrove GP, Bowler RP, Cambier JC. COPD is associated with production of autoantibodies to a broad spectrum of self-antigens, correlative with disease phenotype. Immunol Res. 2013;55(1-3):48–57. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8347-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petri M. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2002;16(5):847–58. doi: 10.1053/berh.2002.0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz MM, Ahmadiyeh N, Jia L, Herman P, Verzi MP, Doddapaneni H, Beckwith CA, Chan JA, Hills A, Davis M, et al. The 8q24 cancer risk variant rs6983267 shows long-range interaction with MYC in colorectal cancer. Nature Genetics. 2009;41(8):882–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H, Zhu X. Power comparison of admixture mapping and direct association analysis in genome-wide association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2012;36(3):235–43. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan EA, Hokanson JE, Murphy JR, Make B, Lynch DA, Beaty TH, Curran-Everett D, Silverman EK, Crapo JD. Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD. 7(1):32–43. doi: 10.3109/15412550903499522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repapi E, Sayers I, Wain LV, Burton PR, Johnson T, Obeidat M, Zhao JH, Ramasamy A, Zhai G, Vitart V, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies five loci associated with lung function. Nat Genet. 2010;42(1):36–44. doi: 10.1038/ng.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybicki BA, Levin AM, McKeigue P, Datta I, Gray-McGuire C, Colombo M, Reich D, Burke RR, Iannuzzi MC. A genome-wide admixture scan for ancestry-linked genes predisposing to sarcoidosis in African-Americans. Genes Immun. 2011;12(2):67–77. doi: 10.1038/gene.2010.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz AG, Wenzlaff AS, Bock CH, Ruterbusch JJ, Chen W, Cote ML, Artis AS, Van Dyke AL, Land SJ, Harris CC, et al. Admixture mapping of lung cancer in 1812 African-Americans. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(3):312–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha Q, Zhang X, Zhu X, Zhang S. Analytical correction for multiple testing in admixture mapping. Hum Hered. 2006;62(2):55–63. doi: 10.1159/000096094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shriner D, Adeyemo A, Ramos E, Chen G, Rotimi CN. Mapping of disease-associated variants in admixed populations. Genome Biology. 2011;12(5):223. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-5-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler Artigas M, Loth DW, Wain LV, Gharib SA, Obeidat M, Tang W, Zhai G, Zhao JH, Smith AV, Huffman JE, et al. Genome-wide association and large-scale follow up identifies 16 new loci influencing lung function. Nat Genet. 2011a;43(11):1082–90. doi: 10.1038/ng.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler Artigas M, Wain LV, Repapi E, Obeidat M, Sayers I, Burton PR, Johnson T, Zhao JH, Albrecht E, Dominiczak AF, et al. Effect of five genetic variants associated with lung function on the risk of chronic obstructive lung disease, and their joint effects on lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011b;184(7):786–95. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201102-0192OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svanes C, Sunyer J, Plana E, Dharmage S, Heinrich J, Jarvis D, de Marco R, Norback D, Raherison C, Villani S, et al. Early life origins of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2010;65(1):14–20. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.112136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashkin DP, Li N, Halpin D, Kleerup E, Decramer M, Celli B, Elashoff R. Annual rates of change in pre- vs. post-bronchodilator FEV1 and FVC over 4 years in moderate to very severe COPD. Respir Med. 2013;107(12):1904–11. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgerson DG, Capurso D, Ampleford EJ, Li X, Moore WC, Gignoux CR, Hu D, Eng C, Mathias RA, Busse WW, et al. Genome-wide ancestry association testing identifies a common European variant on 6q14.1 as a risk factor for asthma in African American subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012a;130(3):622–629 e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgerson DG, Gignoux CR, Galanter JM, Drake KA, Roth LA, Eng C, Huntsman S, Torres R, Avila PC, Chapela R, et al. Case-control admixture mapping in Latino populations enriches for known asthma-associated genes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012b;130(1):76–82 e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sickle D, Magzamen S, Mullahy J. Understanding socioeconomic and racial differences in adult lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(5):521–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201012-2095OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara C, Caraballo L, Mercado D, Jimenez S, Rojas W, Rafaels N, Hand T, Campbell M, Tsai YJ, Gao L, et al. African ancestry is associated with risk of asthma and high total serum IgE in a population from the Caribbean Coast of Colombia. Hum Genet. 2009;125(5-6):565–79. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0649-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agusti AG, Jones PW, Vogelmeier C, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Fabbri LM, Martinez FJ, Nishimura M, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(4):347–65. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0596PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner PD. FEV(1) in the suburbs: choose your research subjects wisely. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(5):495–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201105-0896ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan ES, Hokanson JE, Murphy JR, Regan EA, Make BJ, Lynch DA, Crapo JD, Silverman EK Investigators CO. Clinical and radiographic predictors of GOLD-unclassified smokers in the COPDGene study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(1):57–63. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201101-0021OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Young JH, Fox E, Keating BJ, Franceschini N, Kang S, Tayo B, Adeyemo A, Sun YV, Li Y, et al. Combined admixture mapping and association analysis identifies a novel blood pressure genetic locus on 5p13: contributions from the CARe consortium. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(11):2285–95. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Zhang S, Tang H, Cooper R. A classical likelihood based approach for admixture mapping using EM algorithm. Hum Genet. 2006;120(3):431–45. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0224-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.