Abstract

Pear cv. Punjab Beauty has become quite popular in Punjab. Excessive softening during cold storage leading to low shelf life is the major factor limiting its wider adoption. Studies were, therefore, conducted to determine the firmness and pectin methyl esterase (PME) activity at 4 harvest dates (2nd, 3rd and 4th week of July, and 1st week of August). Various packaging materials i.e. corrugated fiber board boxes and crates with high and low density polyethylene liners, corrugated fiber board boxes, crates and wooden boxes were also evaluated for their role in extending the shelf life of fruits. The enzyme activity and fruit firmness was evaluated periodically after 30, 45, 60 and 75 days of storage at 0–1 °C and 90–95 % RH. The firmness of the fruits decreased with the increase in storage intervals but the enzyme activity increased with the storage period up to 60 days and declined thereafter. Ripening-related changes in all the harvests were characterized mainly by an increase in the solubilization of pectin with a concomitant decrease in the degree of firmness. There was a continuous increase in enzyme activity with the advancement in harvesting dates and then fell sharply in the advanced ripening stages. Highest pectin methyl esterase activity was in fruits packed in crates followed by wooden boxes and corrugated fiber board boxes while the lowest was recorded in fruits packed in corrugated fiber board boxes with high density polyethylene liners. Therefore, high density polyethylene lined CFB boxes proved to be most effective in preventing the loss in firmness.

Keywords: Pear (Pyrus communis), Fruit ripening, Pectin, Pectin methyl esterase, Firmness

Introduction

Fruit ripening is a complex process involving major transitions in fruit development and metabolism. It is a highly coordinated, genetically programmed, and an irreversible phenomenon involving a series of physiological, biochemical, and organoleptic changes, that finally leads to the development of a soft edible ripe fruit with desirable quality attributes. Excessive textural softening during ripening leads to adverse effects/spoilage upon storage. The loss of flesh texture experienced by pome fruits upon ripening is attributable, in part, to dissolution of the ordered arrangement of cell-wall and middle lamella polysaccharides (Knee and Bartley 1981). It is generally believed that textural changes during the ripening of fruits largely arise from the degradation of the primary cell wall whose major component is pectins. During fruit softening, pectin and hemicellulose in walls typically undergo solubilization and depolymerization that are thought to contribute to wall loosening (Fisher and Bennett 1991). Prominent among the enzymes implicated in cell wall changes and softening are pectin methyl esterase and polygalacturonase because striking changes in wall pectin content are observed in ripening fruits (Ahmed and Labavitch 1980; Pressey 1977) and activities of these two enzymes often increase as ripening continues (Carvalho et al. 2009). Further, many storage techniques have been developed over the years to extend the storage life of fruits. Among all the postharvest technologies available for the retention of overall quality of fruit at low temperatures, modified atmosphere packaging has the advantage of low cost and easy implementation at the commercial level. Horticultural products are a main application for MAP, and reduced levels of O2 and increased levels of CO2 in the atmosphere surrounding fresh produce seem to have several positive effects: MA reduces respiration rate, ethylene production and sensitivity and texture losses, improves chlorophyll and other pigment retention, delays ripening and senescence and reduces the rate of microbial growth and spoilage (Rodriguez-Aguilera and Oliveira 2009). The shelf life of MA packaged pears could be extended approximately 0.75 to 1.5 times in comparison to unpacked pears (Mangaraj et al. 2011). Particular aspects of packaging and storage in fruits have been described previously Kader and Watkins (2000), Keditsu et al. (2003), Nath et al. (2010) and Wijewardane and Guleria (2011), but the combined effect of harvesting time as well as the packaging materials on firmness and the enzyme activity has not been studied. Thus, the aim of the present work was to study the relationship between softening and ‘the activity of the enzyme (PME) mainly associated with ripening at different stages of fruit maturity and the corresponding effect of different packaging materials on the pectin methyl esterase activity and the firmness of fruits during ripening of pears, cv. Punjab Beauty.

Materials and methods

The present investigation was carried out in the Department of Horticulture and Punjab Horticultural Post-harvest Technology Centre PAU, Ludhiana for 2 years. In the first experiment fruits of pear (Pyrus communis) cv. Punjab Beauty were harvested on four different dates i.e. 2nd, 3rd and 4th week of July, and 1st week of August. The bruised and diseased fruits were sorted-out and only healthy ones were selected for present studies. The fruits were washed with chlorinated water (100 ppm), air-dried and packed in corrugated fiberboard (CFB) boxes and stored at 0–1 °C and 90–95%RH in walk-in-cool chambers. The observations for firmness and pectin methyl esterase activity were recorded at 30, 45, 60 and 75 days of storage. In the second experiment, uniform sized and disease free fruits of pear cv. Punjab Beauty were harvested in 3rd week of July randomly from all sides of the tree. The fruits were collected in crates, kept in shade and immediately shifted to laboratory for further studies. The fruits were thoroughly washed with tap water and air dried. These fruits were then packed in CFB boxes with low density polyethylene (LDPE) liners, CFB boxes with high density polyethylene (HDPE) liners, crates with low density polyethylene (LDPE) liners, crates with high density polyethylene (HDPE) liners, CFB boxes, crates and wooden boxes and stored in walk-in-cool chamber at 0–1 °C and 90–95 % relative humidity. The observations for pectin methyl esterase activity and firmness were recorded at 30, 45, 60 and 75 days storage interval. The firmness of the fruit was measured with hand held penetrometer (Model FT-327) made in Italy and supplied by Elixir Technologies, Bangalore having plunger diameter of 8 mm, and expressed in terms of kg/cm2.

For enzyme extraction, fruit samples were stored immediately after harvest in the cool chamber. Twenty grams of fruit pulp was blended in 60–100 ml 0.15 M NaCl solution, filtered through two layers of cheese-cloth, centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C. The pH of the titration was constantly maintained at 7.0 for 0.15 M of NaCl solution for maximum PME activity considering the results of Castaldo et al. 1989; Denes et al. 2000 and Contreras-Esquivel et al. 1999 as there is direct correlation between pH and salt concentration used. The supernatant was used as an enzyme source. The activity of PME was determined by measuring the increase in acidity after the hydrolysis of pectin by the enzyme. For PME essay 20 ml of the per cent solution was taken in 50 ml beaker, pH was adjusted to 7.0 by adding 1 N NaOH. This was the zero time. Then, the beaker was placed in a water bath at 30 °C for 15 min and pH was checked and adjusted up to 7.0 after every 15 min by using 0.02 N NaOH, while stirring the contents and noted the volume of alkali used at each interval (Mahadevan and Sridhar 1982). Pectin methyl esterase units were expressed by the symbols PME (units/ml juice) which represents the milli equivalents of esters hydrolyzed per min per ml of juice. The units per milliliter were multiplied by 1,000 for easy interpretation and were calculated by the following formula (Balaban et al. 1991):

|

Statistical analysis

The study was conducted for two seasons (2006 and 2007) and data were pooled and analyzed statistically as per completely randomized block design with factorial arrangement having three replications, each replication comprising of 2 kg fruits. Analysis of variance was done using SPSS software (SPSS INC 2007) to statistically differentiate the differences among various treatments. Each observation is a mean of six replications for 2 years.

Results and discussion

Harvesting dates and firmness

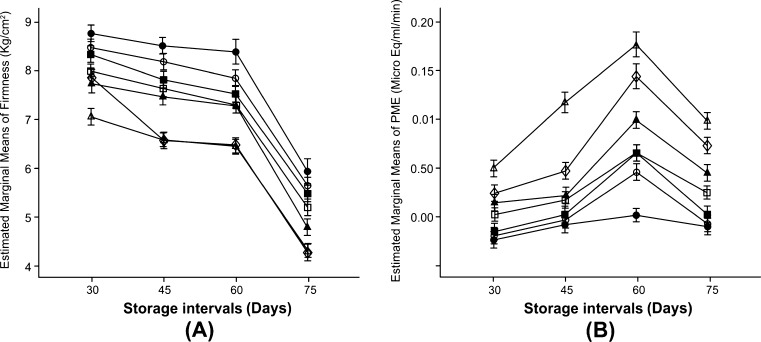

The firmness of fruits harvested in 2nd and 3rd week of July (Fig. 1a and Table 1) had little decline from 30 to 60 days, and finally dropped to 5.49 and 5.10 kg/cm2, respectively after 75 days which was still in the acceptable range (Dhillon and Mahajan 2011). The firmness of fruits harvested in 4th week of July decreased linearly from 5.71 kg/cm2 after 45 days of storage to 4.09 kg/cm2 after 75 days. The firmness of fruits harvested on last harvest date declined to 5.06 kg/cm2 after 30 days of storage and decreased substantially to 3.33 kg/cm2 at the end of 75 days. Thus, the fruits harvested in 1st week of August maintained the acceptable level of firmness up to 45 days of storage period and thereafter a dramatic loss of firmness was observed. The firmness of pear fruits followed a declining trend commensurating with advancement in storage period. The reduction in firmness observed as fruits ripen is mostly a consequence of modifications on cell wall carbohydrate metabolism and on its structure (Ali et al. 2004). Fruit firmness is considered one of the main quality attributes and often limits post-harvest shelf life. The softening process is thought to be a consequence of de-esterification of pectin catalyzed by PME followed by pectin depolymerization catalyzed by PG, thus PG activity is dependent on PME for making substrate available (Abu-Goukh and Bashir 2003).

Fig. 1.

Effect of different harvesting times ( 2nd week of July,

2nd week of July,  3rd week of July,

3rd week of July,  4th week of July,

4th week of July,  1st week of August) and storage intervals on (a) Firmness and (b) pectin methyl esterase activity of pear fruits. Error bars represent standard deviation of means of six replicate samples

1st week of August) and storage intervals on (a) Firmness and (b) pectin methyl esterase activity of pear fruits. Error bars represent standard deviation of means of six replicate samples

Table 1.

ANOVA of harvesting dates and storage intervals for firmness and pectin methyl esterase (PME) activity of pear fruits

| Source | d.f. | F value (Firmness) | F value (PME) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harvesting dates(HD) | 3 | 2.513 | 11.123 |

| Storage Intervals(SI) | 3 | 1.529 | 13.068 |

| HD * SI | 9 | 234.354 | 0.576 |

Abbreviation: ANOVA analysis of variance

Significance terms: P < 0.001

Harvesting dates and pectin methyl esterase activity

The enzyme activity increased with the storage period up to 60 days and declined thereafter (Fig. 1b). Fruits developed more at picking time showed a steeper decline in PME activity. The fruit PME activity increased with the delay in harvesting dates (Fig. 1b and Table 1). The earliest harvested fruits exhibited a significantly lower PME activity than the fruits harvested later in the season. Thus, the maximum PME activity was noted in fruits harvested in 1st week of August. The enzyme activity in fruits after 75 days of storage exhibited a significant decline under all the harvesting dates. The juice of ripe fruit is rich in dissolved pectin which is solublized protopectin dissolved partly in cell sap and partly in middle lamella. Protopectin is the mother substance of pectin compounds which is hydrolyzed by the enzyme protopectinase into soluble product pectin (Hulme 1970). Pectins are likely to be the key substances involved in the mechanical strength of the primary cell wall and are important to the physical structure of the plant (Sirisomboon et al. 2000). The increased enzyme activity might be because of increase in pectin content due to the conversion of insoluble proto-pectin into soluble pectin and this soluble pectin acts as a substrate for PME enzyme as a result of which its activity increased. PME catalyses the hydrolysis of pectin methyl ester groups, resulting in deesterification. They de-esterify the esterified pectic substances, making them vulnerable for PG action (Wong 1995). Its action may be a pre-requisite for the action of PG during ripening. PME activity was found to increase with the prolongation of storage period up to 60 days and thereafter decline in enzyme activity was recorded. This decline in PME activity after 75 days of storage might be attributed to the fact that pectin is the substrate on which enzyme PME acts. After solubilization of pectin, no further increase in activity is observed. Koslamund et al. (2005) reported highest PME activity at the green stage when the fruit firmness was high and it decreased as ripening progressed.

Packaging materials and firmness

The firmness of fruits decreased with the increase in storage intervals (Fig. 2a and Table 2). There was slight decrease in firmness in fruits after 30 days of storage whereas loss in firmness was significant after 75 days. Various packaging materials also exerted a significant influence on the fruit firmness (Kaur et al. 2011). The maximum fruit firmness was noted in fruits packed in CFB boxes with HDPE liners, followed by fruits packed in CFB boxes with LDPE liners. The minimum fruit firmness was recorded in fruits packed in crates. The higher loss of firmness in fruits packed in crates and wooden boxes might be due to the increased metabolic activities of fruits in these containers resulting in breakdown of insoluble protopectin to soluble pectin and pectic acid. The maintenance of higher firmness in HDPE and LDPE lined CFB boxes might be due to the fact that these films create modified atmosphere conditions around the fresh fruits as observed by Roy and Pal (1993). Further, the high humidity maintained inside these films, helps in reducing the transpiration loss and respiration activity and thus retained turgidity of the cells.

Fig. 2.

Effect of different packaging materials ( CFB boxes + LDPE Liners,

CFB boxes + LDPE Liners,  CFB boxes + HDPE Liners,

CFB boxes + HDPE Liners,  Crates + LDPE Liners,

Crates + LDPE Liners,  Crates + HDPE Liners,

Crates + HDPE Liners,  CFB boxes,

CFB boxes,  Crates,

Crates,  Wooden boxes) and storage intervals on (a) Firmness and (b) pectin methyl esterase activity of Pear fruits. Error bars represent standard deviation of means of six replicate samples

Wooden boxes) and storage intervals on (a) Firmness and (b) pectin methyl esterase activity of Pear fruits. Error bars represent standard deviation of means of six replicate samples

Table 2.

ANOVA of packaging materials and storage intervals for firmness and pectin methyl esterase (PME) activity of pear fruits

| Source | d.f. | F value (Firmness) | F value (PME) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Packaging Materials(PM) | 6 | 8.045 | 1.363 |

| Storage Intervals(SI) | 3 | 5.680 | 1.567 |

| PM * SI | 18 | 155.767 | 529.738 |

Abbreviation: ANOVA analysis of variance

Significance terms: P < 0.001

Packaging materials and pectin methyl esterase activity

Packaging materials had a significant influence on the PME activity. This was due to the difference in conditions generated inside the various packages. The lower levels of O2 and increased levels of CO2 maintained inside the CFB boxes with liners reduced the physiological loss in weight, spoilage and texture losses. However, the maximum PME activity was observed in fruits packed in crates which was significantly higher than other packaging treatments. It is apparent from (Fig. 2b and Table 2) that after 30 days of storage, maximum PME activity was in fruits packed in crates followed by wooden boxes and CFB boxes, which were significantly higher than other packaging materials. Minimum PME activity was recorded in fruits packed in CFB boxes with HDPE liners. After 45 and 60 days of storage, an overall increase in PME activity was noted. However, in CFB boxes with HDPE liners, least enzyme activity was noticed while the maximum enzyme activity was recorded in fruits packed in crates. The PME activity after 75 days of storage followed a declining trend commensurating with the advancement in storage period but the decrease was more pronounced in crates and wooden boxes. Pectin methyl esterase removes the methyl groups of the galacturonic acid polymers. De-esterification of polygalacturonic chains by pectin methyl esterase (PME) may make the chains more susceptible to polygalacturonase degradation (Carpita and Gibeaut 1993) facilitating rapid loss of cell wall structure. However, under high CO2 storage the increase in activity of these enzymes was inhibited (Sanchez et al. 1998). Thus, the PME activity inside the polyethylene packaging was less as compared to crates, wooden boxes and CFB boxes.

Conclusion

The fruits of pear cv. Punjab Beauty packed in CFB boxes lined with HDPE liners proved to be the best in storing the fruits for 60 days at 0–1 °C and 90–95 % RH. The fruits maintained textural properties as well. The values obtained in this study show that, with the advancement in harvesting dates there is a decrease in the degree of firmness and increase in the values of PME activity. However, PME activity was lowest at the early stage of harvesting when the fruit firmness was high then reached the maximum levels at physiologically mature stage and thereafter declined as the ripening progressed.

References

- Abu-Goukh ABA, Bashir HA. Changes in pectic enzymes and cellulase activity during guava fruit ripening. Food Chem. 2003;83:213–218. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(03)00067-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed AE, Labavitch JM. Cell wall metabolism in ripening fruits. I. Cell wall changes in ripening ‘Bartlett pears. Plant Physiol. 1980;65:1009–1013. doi: 10.1104/pp.65.5.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali ZM, Chin LH, Lazan H. A comparative study on wall degrading enzymes, pectin modifications and softening during ripening of selected tropical fruits. Plant Sci. 2004;167:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.03.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban MO, Arreola AG, Marshall M, Peplow A, Wei CI, Cornel J. Inactivation of pectinesterase in orange juice by supercritical carbon dioxide. J Food Sci. 1991;56:743–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1991.tb05372.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita NC, Gibeaut DM. Structural models of the primary cell walls in flowering plants: Consistency of molecular structure with physical properties of walls during growth. Plant J. 1993;3:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.1993.tb00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho AB, Assis SA, Leite KC, Bach EE, Oliveira MM. Pectin ethylesterase activity and ascorbic acid content from guava fruit, cv. Predilecta, in different phases of development. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2009;60:255–265. doi: 10.1080/09637480701752244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaldo D, Quagliuolo L, Servillo L, Balestrieri C, Giovanne A. Isolation and characterization of pectinmethylesterase from apple fruit. J Food Sci. 1989;54(653–655):673. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Esquivel JC, Correa-Robles C, Aguilar CN, Rodriguez J, Romero J, Hours RA. Pectinesterase extraction from Mexican lime (Citrus aurantifolia Swingle) and prickly pear (Opuntia ficus indica L.) peels. Food Chem. 1999;65:153–156. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(98)00012-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denes JM, Baron A, Drilleau JF. Purification, properties and heat inactivation of pectinmethylesterase from apple (cv Golden Delicious) J Sci Food Agr. 2000;80:1503–1509. doi: 10.1002/1097-0010(200008)80:10<1503::AID-JSFA676>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon WS, Mahajan BVC. Ethylene and ethephon induced fruit ripening in pear. J Stored Prod Res. 2011;2:45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RL, Bennett AB. Role of cell wall hydrolases in fruit ripening. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1991;42:675–703. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.42.060191.003331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme AC. The biochemistry of fruits and their products. London and New York: Academic; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Kader AA, Watkins CB. Modified atmosphere packaging toward 2000 and beyond. Hortic Technol. 2000;10:483–486. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur K, Dhillon WS, Mahajan BVC (2011) Effect of different packaging materials and storage intervals on physical and biochemical characteristics of pear. J Food Sci Tech doi:10.1007/s13197-011-0317-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Keditsu R, Sema A, Maiti CS. Effect of modified packaging and low temperature on post harvest life of ‘Khasi’ mandarin. J Food Sci Tech. 2003;40:646–651. [Google Scholar]

- Knee M, Bartley IM. Composition and metabolism of cell wall polysaccharides in ripening fruits. In: Friend J, Rhodes M, editors. Recent advances in the biochemistry of fruits and vegetables. London: Academic; 1981. pp. 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Koslamind R, Archbold DD, Pomper KW. Pawpaw fruits II. Acidity of selected cell-wall degrading enzyme. Amer J Hort Sci. 2005;130:643–648. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan A, Sridhar R. Methods in physiological plant pathology. Madras: Sivagami Pub; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Mangaraj S, Sadawarti MJ, Prasad S. Assessment of quality of pears stored in laminated modified atmosphere packages. Int J Food Prop. 2011;14:1110–1123. doi: 10.1080/10942910903582559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nath A, Deka BC, Singh A, Patel RK, Paul D, Misra LK, Ojha H (2010) Extension of shelf life of pear fruits using different packaging materials. J Food Sci Tech. doi:10.1007/s13197-011-0305-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pressey R (1977) Enzymes involved in fruit softening. In: Ory RL, St. Angelo AJ (eds) Enzymes in food and beverage processing. A.C.S. Symp. Ser 47. Amer Chem Soc, Washington, D.C., pp 172–191

- Rodriguez-Aguilera R, Oliveira JC. Review of design engineering methods and applications of active and modified atmosphere packaging systems. Food Eng Rev. 2009;1:66–83. doi: 10.1007/s12393-009-9001-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy SK, Pal RK. Use of plastics in post-harvest technology of fruits and vegetables- a review. Indian Food Packer. 1993;47:27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez JA, Zamorano JP, Alique R. Polygalacturonase, cellulase and invertase activities during Cherimoya fruit ripening. Hort Sci Biol. 1998;73:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sirisomboon P, Tanaka M, Fujita S, Kojima T. Relationship between the texture and pectin constituents of Japanese pear. J Texture Stud. 2000;31:679–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4603.2000.tb01028.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc . SPSS Base 16.0 for windows user’s guide. Chicago: SPSS Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wijewardane RMNA, Guleria SPS (2011) Effect of pre-cooling, fruit coating and packaging on postharvest quality of apple. J Food Sci Tech. doi:10.1007/s13197-011-0322-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wong DWS. Pectic enzymes. Food enzymes. Structure and mechanisms. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1995. pp. 212–236. [Google Scholar]