Abstract

The antioxidant activity of bayberry leaf extract determined by DPPH• and FRAP assay was comparable with ascorbic acid. Prodelphinidins in the extract had significant positive correlation with the antioxidant activities of bayberry leaf extract. The correlation coefficients (R) were 0.963 and 0.970 for DPPH• and FRAP assay, respectively. In order to develop a new natural antioxidant, a central composite design was employed and the yield of prodelphinidins was selected as the response value to investigate the extraction. The best possible combination of acetone concentration, time, solid–liquid ratio and temperature was obtained for the maximum extraction of prodelphinidins by using response surface methodology (RSM). The extraction yield of prodelphinidins was affected significantly by process variables. The optimal conditions obtained by RSM include 56.93 % acetone, 31.98 min time, 1: 44.52 solid–liquid ratio, and 50.00 °C temperature. Under the optimum condition, the experimental yield of prodelphinidins was 117.3 ± 5.1 mg/g, which was not different from the predicted value significantly.

Keywords: Antioxidant activity, Bayberry leaf, Extraction, Prodelphinidin, Response Surface Methodology

Introduction

Bayberry (Myria rubra Sieb. et Zucc.), which is cultured in China for more than 2000 years, belongs to the genus Myrica in the family of Myricaceae (Chen et al. 2004). Bayberry fruits are popular to local people and recently the consumption of bayberry fruit products has increased rapidly. Traditionally, bayberry leaves, twigs, barks, and roots are used as stimulants and astringents. It is also recorded in “Compendium of Materia Medica” that bayberry barks have therapeutic effects on intestinal disorders and arthritis (Matsuda et al. 2002). Recently, the co-workers in our laboratory report that the fruits, pomace, kernels, and leaves of bayberry are rich in phenolics and other nutrient components. Their extracts have antioxidant, antimicrobial, and antiviral activities (Cheng et al. 2008; Fang et al. 2009; Yang et al. 2011; Zhou et al. 2009).

Proanthocyanidins, which are widespread in plant kingdom, are natural phenolic compounds with a basic structure of C6•C3•C6. Proanthocyanidins are mainly divided into procyanidins, prodelphinidins (PDs), and propelargonidins. Proanthocyanidins obtained their name from the characteristic oxidative depolymerization reaction in acidic medium, which yields colored anthocyanidins. Proanthocyanidins have received more and more attention in recent years because of their bioactivity (Karthikeyan et al. 2007; Kresty et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2007). Proanthocyanidins are usually extracted by aqueous organic solvents. Ascorbic acid and other antioxidants sometimes are added to the extraction solvents to prevent oxidation (Karonen et al. 2007). Acidic solvents can also be used for extraction of proanthocyanidins. However, the usage of acidified extraction solvents is a double-edged sword because the inter-flavanoid bond is acid sensitive and the structure might be modified. Bayberry leaf proanthocyanidins are of the prodelphinidin type consisting mostly of epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate.

China is the major commercial production area for bayberry. And Zhejiang province is the largest province for bayberry production in China. Bayberry trees flush two or three times a year. Foliar growth is luxuriant and leaves remain green throughout the year. The tree needs to be pruned every year more than once to get high fruit production. Pruning yields a mass of leaves, which are generally discarded and remain underutilized. The flavonoids and antioxidant capacities of bayberry leaves were investigated by some scientists before (Xia et al. 2004; Zou and Li 1998). Our previous work reported that bayberry leaves were rich in proanthocyanidins (Yang et al. 2011). However, little work has been done on the distribution and contents of PDs in bayberry leaves and the contribution of PDs to the antioxidant capacities of bayberry leaves. In order to develop a new natural antioxidant, it was necessary to investigate the antioxidant activity of the extract from different bayberry leaves and to optimize the extraction of the antioxidant.

Reponse surface methodology (RSM) is a useful statistical technique, which combines fractional factorial design and a second-degree polynomial model to investigate complex processes, and it has been widely used in different fields. The original concept was developed by Box and Wilson (1951), and the basic theoretical, fundamental, and biological applications were reviewed by Mead and Pike (1975).

In the present work, the antioxidant activities of different bayberry leaves were investigated. The yield of the compound which was mainly correlative with the antioxidant activity was selected as the response value to investigate the influence of extraction condition on the extraction yield of the compound from bayberry leaves.

Materials and methods

Materials

In order to estimate the antioxidant activity, bayberry leaves of two cultivars, Biqi and Dongkui, growing in Xianju in Zhejiang province in south-eastern China were harvested by hand from randomly chosen plants in July 2009. The age of a leaf can be estimated conventionally by color: immature leaves are bright green; mature leaves are dull and dark green; and the green of intermediate leaves is deeper than that of immature leaves but lighter than that of mature leaves. For optimization of extraction of PDs, immature leaves of cultivar Dongkui, were harvested in Xianju in July 2010. All the collected leaves were washed and then dried under vacuum at 40 °C for 12 h, ground fine, and stored at −20 °C until required.

Catechin, Folin-Ciocalteu phenol reagent, 2, 4, 6-tris (2-pyridyl)-s-triazine (TPTZ), and 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH) were obtained in the form of commercial samples from Sigma (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). Grape seed procyanidins were purchased form Ci Yuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Shaanxi (China). The content of procyanidins is more than 95 %. All other reagents and solvents used were of analytical grade.

Determination of the antioxidant activity of bayberry leaf extracts

Phenolics were extracted from samples (1 g each) of bayberry leaf powder in a conical flask with stopper (100 mL) by mixing them extracted with 10 mL of 70 % aqueous acetone for 15 min at room temperature. The process was repeated three times. Then the extraction solution was recovered, and 70 % aqueous acetone was added to make a final volume of 50 mL. This solution was then diluted with 70 % aqueous acetone to make different sample solutions with lower concentrations.

Radical scavenging activity assay (DPPH). This assay was based on the method of Gorinstein et al. (2004). Briefly, 0.2 mL of sample solutions was added to 2.8 mL of 0.1 mmol/L DPPH radical solution, which was freshly made. After 30 min of incubation at 27 °C without light, the absorbance at 517 nm was measured. The control was prepared as above with 70 % aqueous acetone, and MeOH was used for baseline correction. Radical-scavenging activity was expressed as percentage inhibition and was calculated using the formula

|

1 |

Ferric reducing ability assay (FRAP). The ferric reducing ability of bayberry leaf extract was measured according to a modified protocol developed by Benzie and Strain (1996). To prepare the FRAP reagent, a mixture of 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 3.6), 10 mM TPTZ, and 20 mM ferric chloride (10:1:1, v/v/v) was made. The FRAP reagent (4.9 mL) was added to 0.1 mL of the sample solutions. Readings were recorded on the Shimadzu UV-2550 spectrophotometer at 593 nm, and the reaction was monitored for 10 min. Then the mean absorbance values were plotted against the concentration of sample solutions.

Determination of PDs and total phenolics

The finely ground powder (1 g each) was extracted as described above. After centrifuging at 2,000 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant was rotary-evaporated under vacuum at 40 °C to remove the acetone and the aqueous phase diluted to 1,000 mL with methanol. All samples were prepared and processed in triplicate.

Total phenolics were estimated using the modified Folin-Ciocalteu method (Xu et al. 2008). Briefly, 1 mL of prepared sample solution was added to a 25 mL volumetric flask filled with 9 mL distilled water. A blank sample was prepared using distilled-deionized water. Folin-Ciocalteu phenol reagent (0.5 mL) was added to the mixture and the mixture was shaken vigorously for 5 min; 5 mL of Na2CO3 solution was added to the mixture; the resulting mixture was immediately diluted to 25 mL with distilled water and mixed thoroughly; and then it was allowed to stand for 60 min before measuring its absorbance at 750 nm. The absorbance was compared with that of the prepared blank. Total polyphenol contents were expressed as milligrams per gram of gallic acid equivalent.

The contents of PDs were determined according to the modified vanillin assay (Sun et al. 1998). One milliliter of the prepared sample solution was mixed first with 2.5 mL of 1 % (w/v) vanillin in methanol and then with 2.5 mL of 20 % (v/v) H2SO4 in methanol to undergo vanillin reaction. A blank sample was prepared using methanol. The vanillin reaction was carried out in a 30 °C water bath for 15 min. The absorbance was measured at 500 nm versus the prepared blank. PDs contents were expressed as milligrams per gram of (+)-catechin equivalent.

Design of statistical experiments

The effects of extraction condition on PDs yield including extraction solvent, acetone concentration, extraction time, temperature, and solid–liquid ratio were investigated by the single factor method. On the basis of the single factor experimental results, a central composite design was applied to investigate the effects of four variables, concentration of acetone (X1), time (X2), solid–liquid ratio (X3), and temperature (X4) on the yield of PDs. The variables were coded at five levels (Table 1) according to the following equation:

|

2 |

where Xi is the dimensionless value of an independent variable, xi is the real value of an independent variable, x0 is the real value of an independent variable at the center point, Δxi is the step change. The optimal levels of were selected as center points (all variables were coded as zero) in the designed experiment. The complete design consisted of 30 experimental points including six replications of the center points (Table 2). The 30 sets of experiments were performed in a random order.

Table 1.

Independent variables and their levels employed in a central composite design

| Independent variables | Independent variables level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −2 | −1 | 0a | 1 | 2 | |

| X 1,Concentration of acetone(%) | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 |

| X 2,Extraction time(min) | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 |

| X 3,Solid–liquid ratio (w/v) | 1: 20 | 1: 30 | 1: 40 | 1: 50 | 1: 60 |

| X 4,Temperature(°C) | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 |

aCenter point

Table 2.

Experimental design of the five-level, four-variable central composite and response values

| Run | Concentration of acetone (%) | Extraction time (min) | Solid–liquid ratio (w/v) | Temperature (°C) | Yield of prodelphinidins(mg/g DWa) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted value | Experimental value | |||||

| 1 | 60 (0) | 30 (0) | 1: 40 (0) | 40 (0) | 115.6 | 112.6 |

| 2 | 70 (1) | 20 (−1) | 1: 30 (−1) | 50 (1) | 107.4 | 111.2 |

| 3 | 70 (1) | 40 (1) | 1: 30 (−1) | 30 (−1) | 99.1 | 99.3 |

| 4 | 70 (1) | 20 (−1) | 1: 50 (1) | 30 (−1) | 97.6 | 93.7 |

| 5 | 50 (−1) | 40 (1) | 1: 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 117.1 | 117.0 |

| 6 | 60 (0) | 10 (−2) | 1: 40 (0) | 40 (0) | 96.8 | 95.6 |

| 7 | 70 (1) | 20 (−1) | 1: 30 (−1) | 30 (−1) | 96.1 | 97.9 |

| 8 | 60 (0) | 30 (0) | 1: 20 (−2) | 40 (0) | 101.2 | 94.2 |

| 9 | 50 (−1) | 20 (−1) | 1: 50 (1) | 30 (−1) | 100.9 | 101.0 |

| 10 | 60 (0) | 30 (0) | 1: 40 (0) | 60 (2) | 125.3 | 121.8 |

| 11 | 60 (0) | 30 (0) | 1: 40 (0) | 40 (0) | 115.6 | 116.5 |

| 12 | 50 (−1) | 20 (−1) | 1: 30 (−1) | 30 (−1) | 97.9 | 99.8 |

| 13 | 80 (2) | 30 (0) | 1: 40 (0) | 40 (0) | 97.7 | 97.4 |

| 14 | 50 (−1) | 40 (1) | 1: 50 (1) | 30 (−1) | 109.3 | 106.0 |

| 15 | 70 (1) | 40 (1) | 1: 50 (1) | 30 (−1) | 104.3 | 105.2 |

| 16 | 60 (0) | 30 (0) | 1: 40 (0) | 40 (0) | 115.6 | 113.7 |

| 17 | 40 (−2) | 30 (0) | 1: 40 (0) | 40 (0) | 104.9 | 103.0 |

| 18 | 60 (0) | 30 (0) | 1: 40 (0) | 40 (0) | 115.6 | 112.1 |

| 19 | 70 (1) | 40 (1) | 1: 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 111.7 | 110.4 |

| 20 | 60 (0) | 30 (0) | 1: 40 (0) | 40 (0) | 115.6 | 118.5 |

| 21 | 50 (−1) | 20 (−1) | 1: 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 112.5 | 112.9 |

| 22 | 50 (−1) | 40 (1) | 1: 30 (−1) | 30 (−1) | 102.6 | 104.5 |

| 23 | 70 (1) | 40 (1) | 1: 30 (−1) | 50 (1) | 106.5 | 108.0 |

| 24 | 60 (0) | 30 (0) | 1: 60 (2) | 40 (0) | 109.3 | 114.1 |

| 25 | 50 (−1) | 40 (1) | 1: 30 (−1) | 50 (1) | 110.5 | 114.9 |

| 26 | 60 (0) | 30 (0) | 1: 40 (0) | 20 (−2) | 106.3 | 107.6 |

| 27 | 50 (−1) | 20 (−1) | 1: 30 (−1) | 50 (1) | 109.6 | 110.3 |

| 28 | 60 (0) | 30 (0) | 1: 40 (0) | 40 (0) | 115.6 | 120.1 |

| 29 | 60 (0) | 50 (2) | 1: 40 (0) | 40 (0) | 104.4 | 103.4 |

| 30 | 70 (1) | 20 (−1) | 1: 50 (1) | 50 (1) | 108.8 | 108.6 |

aDW, dry weight

The experimental data were fitted to the following second-order polynomial equation by DPS software [Design-Expert, Version 7.1.3 (Jun. 2007, Stat-Ease, Inc.)] through the response surface regression procedure:

|

3 |

where Y is the response variable, and A0, Ai, Aii, and Aij are regression coefficients of variables for intercept, linear, quadratic, and interaction terms, respectively. Xi and Xj are independent variables.

The model was predicted through regression analysis and analysis of variance (ANOVA). The quality of the fit of the polynomial model was expressed by the coefficient of determination R2, and its statistical significance was checked using an F-test. A numerical optimization was also carried out by the response optimizer using the DPS software to determine the extract optimum level of independent variables leading to the overall optimized condition.

Statistical analysis

All samples were prepared and analyzed in triplicate. To verify the statistical significance of parameters, the values of means ± standard deviation (SD) were calculated. To compare several groups, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. The correlation coefficient (R) and p value were used to show correlation and their significance [SPSS for Windows, Release 16.0.0 (Sep. 2007, SPSS Inc.)]. Probability values of p < 0.01 and p < 0.05 were adopted as the criterion for significant differences.

Results and discussion

Content of PDs, total phenolics, and extracts

Table 3 shows that the content of PDs, total phenolics, and extracts of bayberry leaves was in the range of 38.40~117.54 mg/g DW, 81.38~196.26 mg/g DW, 311.25~328.75 mg/g DW, respectively. The content of PDs and total phenolics showed great variation in different bayberry leaves. The immature leaves had higher content than mature and intermediate leaves. The content of total phenolics from leaves of cultivar Dongkui was higher than that of leaves of cultivar Biqi. Nevertheless, the content of the extracts of different leaves was similar. Compared with some other plant leaves, the contents of total phenolics in bayberry leaves were lower than those of Nelumbo nucifera leaves (358–487 mg/g, DW) (Huang et al. 2010) and Chromolaena odorata leaves (242 mg/g, DW) (Rao et al. 2010), but higher than those of Calpurnia aurea leaves (9.62 mg/g, DW) (Adedapo et al. 2008), and Stevia rebaudiana Bert. leaves (61.50 mg/g, DW) (Shukla et al. 2009). Besides, the content of PDs in leaves of Nelumbo nucifera, Calliandra, and Calpurnia aurea are 124–179 mg/g (Huang et al. 2010), 74.7–106 mg/g (Salawu et al. 1999), and 4.37 mg/g (Adedapo et al. 2008), respectively. The value of PDs content in this study falls within the range of the leaves mentioned above. These observations suggest that bayberry leaves are a considerably useful source of phenolics and PDs.

Table 3.

Content of total phenolics, prodelphinidins, and extract of different bayberry leaves

| No. | Bayberry leaf | Total phenolics (mg/g DWa) | Prodelphinidins (mg/g DW) | Extract (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Biqi | Immature | 194.0 ± 4.11b a | 117.5 ± 1.96 a | 32.3 ± 0.35 a |

| 2 | Intermediate | 81.4 ± 0.43 d | 38.4 ± 0.80 e | 31.1 ± 0.53 b | |

| 3 | Mature | 117.2 ± 0.45 c | 64.2 ± 1.86 d | 32.9 ± 0.53a | |

| 4 | Dongkui | Immature | 196.3 ± 3.26 a | 101.0 ± 6.32 b | 32.4 ± 0.18a |

| 5 | Intermediate | 115.7 ± 4.10 c | 63.7 ± 1.52 d | 32.4 ± 0.18a | |

| 6 | Mature | 131.7 ± 1.91 b | 77.2 ± 1.58 c | 32.6 ± 0.48a | |

aDW, dry weight;

bMean ± SD of three measurements. Means with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Antioxidant activities

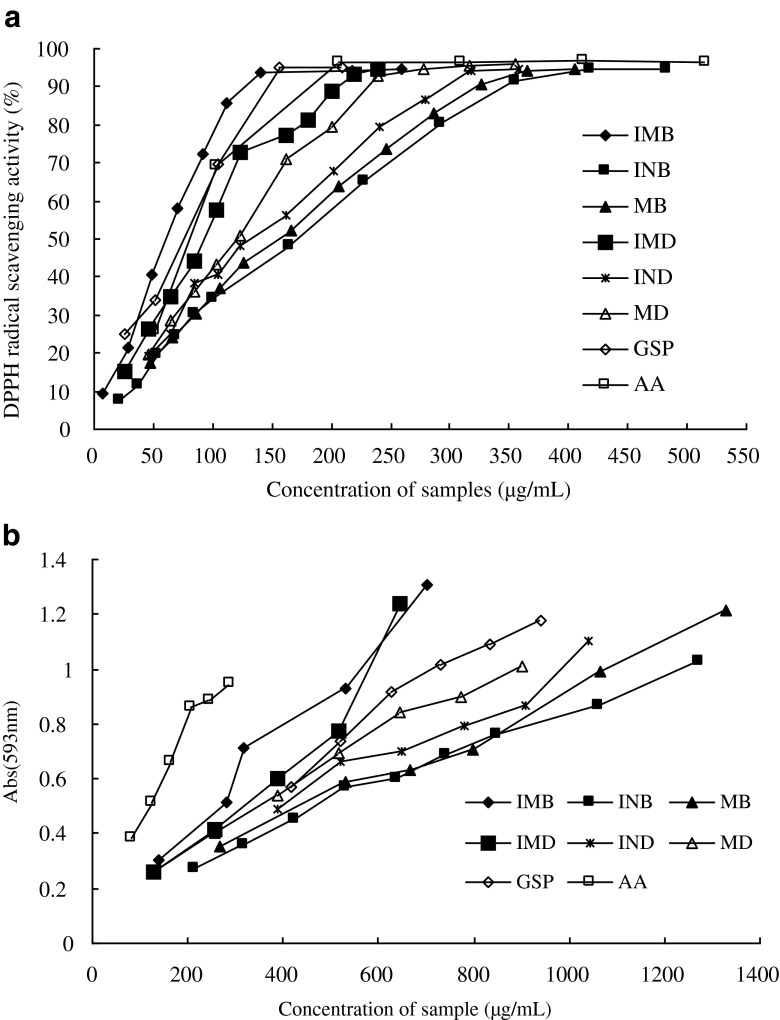

DPPH• scavenging abilities of bayberry leaf extract were compared with grape seed procyanidins and ascorbic acid (Fig. 1a). These test samples all showed excellent scavenging activity. The scavenging effects of the samples increased with their concentrations to similar extents, around 90 % at different concentration. The EC50 values were calculated by extrapolating two plots points adjacent 50 %. The EC50 values indicated that the antioxidant effectiveness decreases in the following order (Table 4): immature leaf of Biqi > grape seed procyanidins > ascorbic acid > immature leaf of Dongkui > mature leaf of Dongkui > intermediate leaf of Dongkui > mature leaf of Biqi > intermediate leaf of Biqi. The results suggested that the scavenging effect of immature leaf extracts of two cultivars, Biqi and Dongkui, were better than extracts of mature and intermediate leaves.

Fig. 1.

Antioxidant activity of samples: a DPPH• assay, b FRAP assay. Each obserbation is a mean of three experiments (n = 3). IMB,immature leaf of cultivar Biqi; INB,intermediate leaf of cultivar Biqi; MB,mature leaf of cultivar Biqi; IMD,immature leaf of cultivar Dongkui; IND,intermediate leaf of cultivar Dongkui; MD,mature leaf of cultivar Dongkui; GSP,grape seed procyanidins;AA,ascorbic acid

Table 4.

The linear equation and EC50 of bayberry leaf extracts, grape seed procyanidins, and ascorbic acid in DPPH radical scavenging

| No. | Sample | Linear equation | EC50(μg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Biqi | Immature |

|

62.25 |

| 2 | Intermediate |

|

170.71 | |

| 3 | Mature |

|

158.45 | |

| 4 | Dongkui | Immature |

|

100.51 |

| 5 | Intermediate |

|

140.53 | |

| 6 | Mature |

|

118.93 | |

| 7 | Grape seed procyanidins |

|

74.02 | |

| 8 | Ascorbic acid |

|

88.06 | |

The results of ferric reducing ability are shown in Fig. 1b. The test samples reduced iron (III) and did so in a linear fashion across the concentration range used in this study. The slope of the line of the samples declined in the following order: ascorbic acid > immature leaf of Biqi > immature leaf of Dongkui > grape seed procyanidins > mature leaf of Dongkui > intermediate leaf of Dongkui > mature leaf of Biqi > intermediate leaf of Biqi. These results indicated that ferric reducing ability of ascorbic acid was strongest and the ability of immature leaf extracts of two cultivars, Biqi and Dongkui, were stronger than extracts of mature and intermediate leaves. The results were slightly different from that of radical scavenging assay. We thought all of the results were reasonable because different reactions were employed (Schlesier et al. 2002). However, results of both assays suggested that the antioxidant activities of immature leaf extracts were highest in all kinds of leaves.

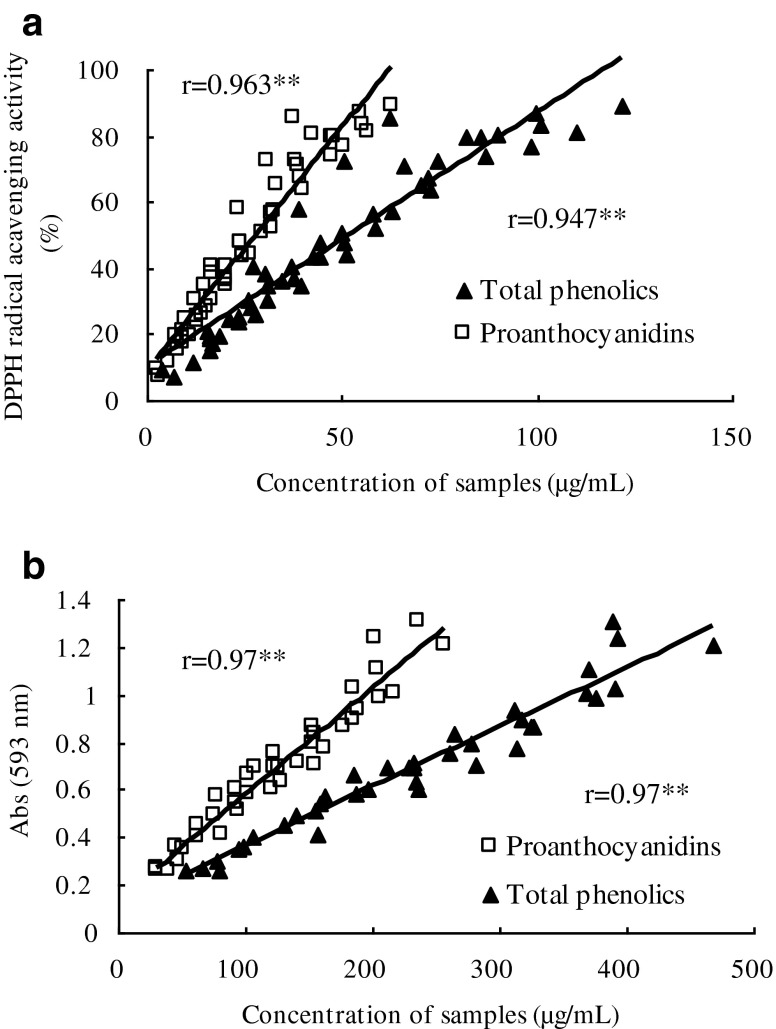

Correlation of PDs, total phenolics, and antioxidant activity

The correlation of PDs, total phenolics, and antioxidant activity was analyzed, and the results are shown in Fig. 2. When all samples were analyzed individually, without grouping in population, a high linear correlation between the antioxidant activity and total phenolics or PDs could be observed as it is shown in Fig. 2. The DPPH radical scavenging activity or absorbance in FRAP assay indicated a positive correlation with total phenolics and PDs. The correlation coefficient of total phenolics was 0.947 in DPPH assay, and 0.97 in FRAP assay, respectively. The correlation coefficient of PDs was 0.963 in DPPH assay, and 0.97 in FRAP assay, respectively. The slope of trendline of PDs in both assays was higher than that of total phenolics.

Fig. 2.

Correlation analysis: a DPPH• assay, b FRAP assay. Each obserbation is a mean of three experiments (n = 3). ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level

The results above suggested that PDs were the major factor accounting for the antioxidant activity of the phenolic extract from bayberry leaves. In fact, the antioxidant activity is not only relative with the content of PDs, but also in relationship with the structure of PDs. Results of our early research showed that PDs in bayberry was prodelphinidins, and the subunits were mainly epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate (Yang et al. 2011). Compared with grape seed procyanidins, which mainly consist of (epi)catechin, the presence of galloyl groups in the structure of bayberry leaf PDs can enhance their antioxidant activities (Aron and Kennedy 2008). Besides, the antioxidant activities are relative with the degree of polymerization.

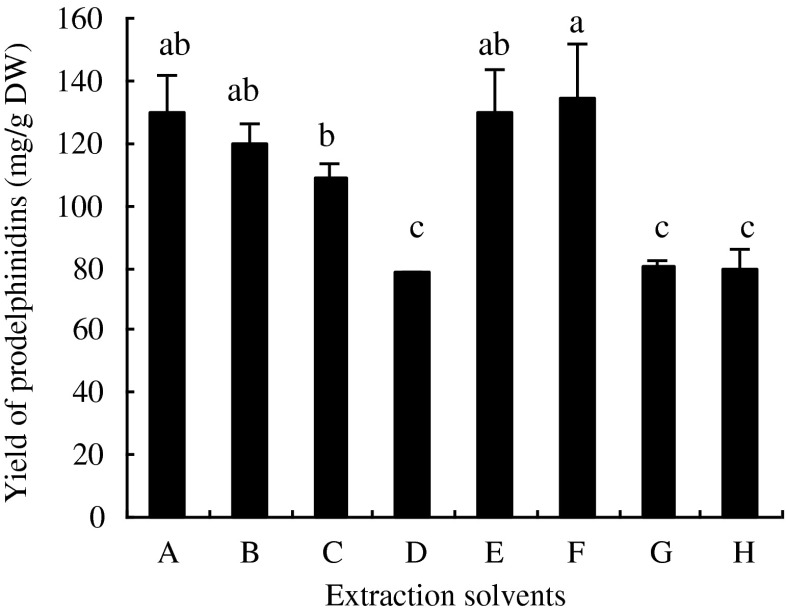

Single factor analysis method

Effect of different extraction solvents, which are commonly used for extraction of PDs, on the yield of PDs were evaluated (Fig. 3). The yield of PDs extracted by different solvents varied significantly (p < 0.05). The yield of PDs extracted by acetone-water was higher than that extracted by methanol- water. Ascorbic acid or acetic acid had no significant affection on the yield of PDs. From the lower-cost point of view, acetone-water was chosen in the present experiment.

Fig. 3.

Effect of different extraction solvents on the yield of prodelphinidins. Each obserbation is a mean of three experiments (n = 3). A, 60 % Acetone; B, 70 % Acetone; C, 80 % Acetone; D, 80 % Methanol; E, 60 % Acetone +0.5 % Acetic acid; F, 60 % Acetone +0.1 % Ascorbic acid; G, 80 % Methanol +0.5 % Acetic acid;F, 80 % Methanol +0.1 % Ascorbic acid. Means in each column with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05)

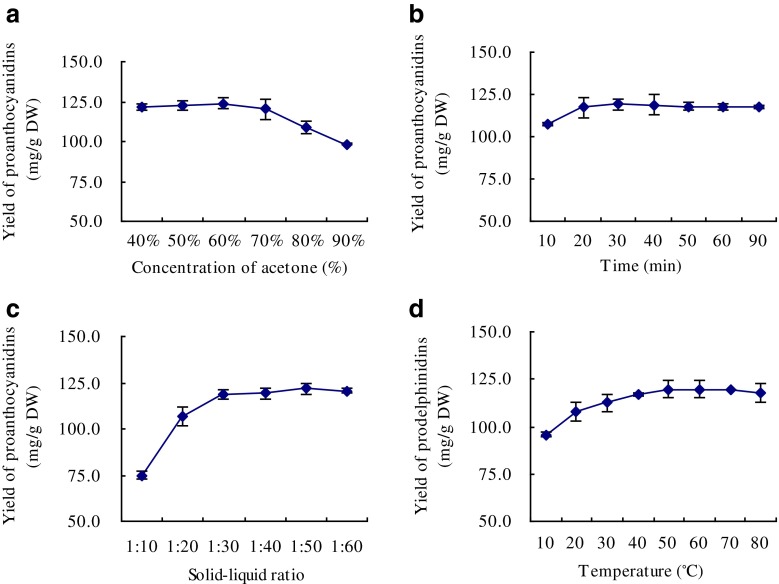

As shown in Fig. 4a, when the concentration of acetone increased from 40 % to 70 %, the variation on the yield of PDs was relative plateau. After the concentration of acetone exceeded 70 %, the variation on the yield of PDs dropped sharply. This phenomenon might be related to the solubility of PDs (Hümmer and Schreier 2008). Figure 4b and c shows a higher yield of PDs on the longer extraction time or at higher solid–liquid ratio, then the yield kept stable after the extraction time exceeded 30 min or the solid–liquid ratio exceeded 1: 30. Figure 4d shows that a higher yield of PDs can be obtained at higher temperature. However, the yield finally dropped when temperature exceeded 60 °C.

Fig. 4.

Effect of different concentrations of acetone (a), time (b), solid–liquid ratio (c), and temperature (d) on the yield of prodelphinidins. Each obserbation is a mean of three experiments (n = 3)

Model fitting

PDs yields of thirty sets of variable combinations were obtained (Table 2) and fitted into two second-order polynomial equations by regression analysis. The equations are as follows:

|

4 |

(4), the equation in terms of coded factors.

|

5 |

(5), the equation in terms of actual factors.

Through performing in the form of analysis of ANOVA for the quadratic model, it was required to test the significance and adequacy of the model. Table 5 shows that the value for the coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.8779, which indicates adequacy of the applied model. The statistical analysis showed that F-value of the model was 7.70, which implied the model was significant and applicable. The analysis of variance also showed that there was a nonsignificant lack of fit, which further validates the model (Kong et al. 2010; Prasad et al. 2012).

Table 5.

Analysis of variance of the regression model

| Source | Sum of squares | Degree of freedom | Mean square | F-value | Prob > F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 1601.47 | 14 | 114.39 | 7.70 | 0.0002 | significant |

| X 1 | 78.12 | 1 | 78.12 | 5.26 | 0.0367 | |

| X 2 | 86.26 | 1 | 86.26 | 5.81 | 0.0292 | |

| X 3 | 98.82 | 1 | 98.82 | 6.66 | 0.0209 | |

| X 4 | 544.35 | 1 | 544.35 | 36.67 | < 0.0001 | |

| X 1 X 2 | 2.98 | 1 | 2.98 | 0.20 | 0.6608 | |

| X 1 X 3 | 2.18 | 1 | 2.18 | 0.15 | 0.7072 | |

| X 1 X 4 | 0.18 | 1 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.9136 | |

| X 2 X 3 | 13.88 | 1 | 13.88 | 0.93 | 0.3490 | |

| X 2 X 4 | 14.63 | 1 | 14.63 | 0.99 | 0.3366 | |

| X 3 X 4 | 6.250E-004 | 1 | 6.250E-004 | 4.210E-005 | 0.9949 | |

|

349.53 | 1 | 349.53 | 23.54 | 0.0002 | |

|

384.64 | 1 | 384.64 | 25.91 | 0.0001 | |

|

182.90 | 1 | 182.90 | 12.32 | 0.0032 | |

|

0.084 | 1 | 0.084 | 5.631E-003 | 0.9412 | |

| Residual | 222.70 | 15 | 14.85 | |||

| Lack of fit | 168.37 | 10 | 16.84 | 1.55 | 0.3285 | not significant |

| Pure error | 54.33 | 5 | 10.87 | |||

| Cor total | 1824.17 | 29 | ||||

| R 2 | 0.8779 |

The significance of each variable effect was also given in Table 5. The corresponding variables were more significant if the p-values are smaller than the confidence level (Amin and Anggoro 2004; Zhang et al. 2011). In this case, X1, X2, and X3 were significant model terms (p < 0.05), X4,  ,

,  and

and  were extremely significant model terms (p < 0.01). The results of statistical analysis indicated that all variables (concentration of acetone, extraction time, solid–liquid ratio, and temperature) had significant effect on yield of PDs. However, the interaction effects of all variables were not significant (p > 0.1) on the extraction of PDs.

were extremely significant model terms (p < 0.01). The results of statistical analysis indicated that all variables (concentration of acetone, extraction time, solid–liquid ratio, and temperature) had significant effect on yield of PDs. However, the interaction effects of all variables were not significant (p > 0.1) on the extraction of PDs.

Optimization and verification

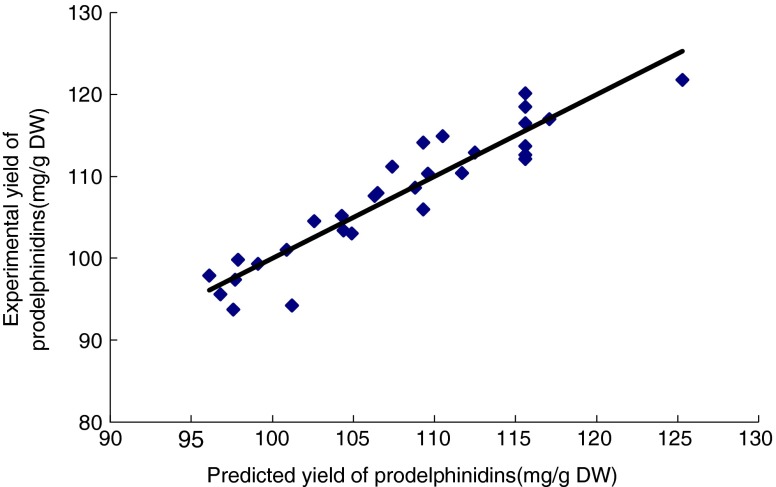

By carrying out parameter optimization on the basis of the built mathematical model, obtained experimental condition were: concentration of acetone (X1) 56.93 %, extraction time (X2) 31.98 min, solid–liquid ratio (X3) 1: 44.52, and extraction temperature (X4) 50 °C. 50 °C was used as the upper limit of temperature in the soft ware. Because extracting at 50 °C was easier and saved more resources than at higher temperature. Stability of PDs was better at lower temperature. The most important thing was that the yield of PDs extracted at 50 °C were comparable with that extracted at 60 °C. This method resulted in 121.2 mg/g yield of PDs. To test the accuracy of the regressive model, experiments under the optimum condition (X1 57 %, X2 32 min, X3 1: 45, X4 50 °C) were repeated, the yield of PDs was 117.3 ± 5.1 mg/g. Based on one-way ANOVA analysis, no significant difference was observed between the response surface model and the verification model (p > 0.05), thus verifying the adequate fitness of the response equations for predicting the yield of PDs. The other predicted values of PDs yield were also calculated by using the predicted regression model and compared with experimental values (Table 2 and Fig. 5). Figure 5 showed that good fitness of the model on the data was confirmed graphically by the scatter plots, in which a high correlation was found between predicted and experimental values. It indicated a close agreement between experimental and predicted values of PDs yield. There was no significant difference between those values, permitting us to validate this model for extraction of PDs again.

Fig. 5.

Scatter plots of experimentally determined yield of prodelphinidins values (mg/g DW) and predicted values (mg/g DW) by the proposed model

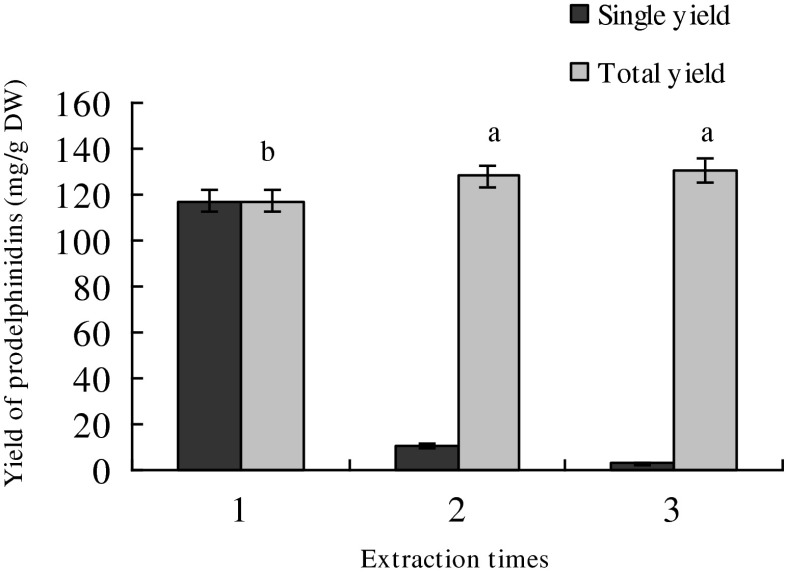

Effect of extraction times

Under the optimal experimental condition, extraction was repeated three times. We can see from Fig. 6 that most PDs were recovered in the first extraction. The yield of PDs extracted twice was significantly higher than that extracted once, and similar with that extracted three times. Therefore, extraction twice was appropriate.

Fig. 6.

Effect of different times of extraction on the yield of prodelphinidins. Each obserbation is a mean of three experiments (n = 3). Means in each column with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Solid–liquid extraction is a mass transport phenomenon in which solids contained in a matrix migrate into solvent brought into contact with the matrix. This mass transport phenomenon can be enhanced with changes in different coefficients included by extraction temperature (). Solvent concentration and extraction time also play a significant role in the extraction of phenolic compounds from plant materials (). Optimization of solvent concentration, time, and temperature is important for the extraction of phenolic compounds from plant material (). Aqueous acetone is the most effective overall extraction solvent for proanthocyanidins because acetone is a strong breaker of hydrogen bonds (Rohr, G. E.; Meier, B.; Sticher, O. Analysis of procyanidins. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem.2000, 21, 497–570.). There is also some evidence that ascorbic acid can be used in the extraction solvent to enhance the recovery of plant proanthocyanidins (Hümmer, W.; Schreier, P. Analysis of proanthocyanidins. Mol. Nutr. Food Res.2008, 52, 1381–1398.). However, our results showed that there was no significant difference between the …

Conclusions

Bayberry leaf is a potential resource for phenolic compounds. The present work estimated the antioxidant activity of bayberry leaf extract. The results indicated that bayberry leaf was endowed with potentially exploitable antioxidant activities. The immature leaves had stronger antioxidant activities than other leaves. The major factor contributed to the antioxidant capacities of bayberry leaf extracts was PDs. Furthermore, the extraction process of PDs from leaves of bayberry was optimized based on response surface model. The response surface model fitted for response variables were highly adequate because of the high coefficient of determination (R2 > 0.85). The optimal conditions based on the model were: concentration of acetone 56.93 %, extraction time 31.98 min, solid–liquid ratio 1: 44.52, and extraction temperature 50 °C. There was no significant difference of PDs yield between the response surface model and the verification model (p > 0.05). Further investigations will concern in-depth analyses of the antioxidant activities of purified PDs.

Acknowledgment

This project was supported by the Key Cultural Project of Innovation of Ministry Education (707034).

References

- Adedapo AA, Jimoh FO, Koduru S, Afolayan AJ, Masika PJ. Antibacterial and antioxidant properties of the methanol extracts of the leaves and stems of Calpurnia aurea. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:53. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin NAS, Anggoro DD. Optimization of direct conversion of methane to liquid fuels over Cu loaded W/ZSM-5 catalyst. Fuel. 2004;83:487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2003.09.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aron PM, Kennedy JA. Flavan-3-ols: nature, occurrence and biological activity. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52:79–104. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzie IFF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Anal Biochem. 1996;239(1):70–76. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Box GEP, Wilson KB. On the experimental attainment of optimal conditions. J R Stat Soc, Ser B. 1951;13:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Chen KS, Xu CJ, Zhang B, Ferguson IB. Red bayberry: botany and horticulture. Hortic Rev. 2004;30:83–114. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng JY, Ye XQ, Chen JC, Liu DH, Zhou SH. Nutritional composition of underutilized bayberry (Myria rubra Sieb. et Zucc.) kernels. Food Chem. 2008;107:1674–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.09.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang ZX, Zhang YH, Lü Y, Ma GP, Chen JC, Liu DH, Ye XQ. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacities of bayberry juices. Food Chem. 2009;113:884–888. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.07.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorinstein S, Haruenkit R, Park YS, Jung ST, Zachwieja Z, Jastrzebski Z, Katrich E, Trakhtenberg S, Belloso OM. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant potential in fresh and dried Jaffa sweeties, a new kind of citrus fruit. J Sci Food Agric. 2004;84(12):1459–1463. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.1800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Ban XQ, He JS, Tong J, Wang YW. Comparative analysis of essential oil components and antioxidant activity of extracts of Nelumbo nucifera from various areas of China. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:441–448. doi: 10.1021/jf902643e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hümmer W, Schreier P. Analysis of proanthocyanidins. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52:1381–1398. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karonen M, Leikas A, Loponen J, Sinkkonen J, Ossipov V, Pihlaja K. Reversed-phase HPLC-ESI/MS analysis of birch leaf proanthocyanidins after their acidic degradation in the presence of nucleophiles. Phytochem Anal. 2007;18:378–386. doi: 10.1002/pca.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan K, Bai BRS, Devaraj SN. Cardioprotective effect of grape seed proanthocyanidins on isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury in rats. Int J Cardiol. 2007;115:326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong KW, Ismail AR, Tan ST, Prasad KMN, Ismail A. Response surface optimization of extraction of phenolics and flavonoids from pink guava puree industry by-product. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2010;45(8):1739–1745. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2010.02335.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kresty LA, Howell AB, Baird M. Cranberry proanthocyanidins induce apoptosis and inhibit acid-induced proliferation of human esophageal adenocarcinoma cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:676–680. doi: 10.1021/jf071997t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Xie BJ, Cao SQ, Yang E, Xu XY, Guo SS. A-type procyanidins from Litchi chinensis pericarp with antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2007;105:1446–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.05.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda H, Morikawa T, Tao J, Ueda K, Yoshikawa M. Bioactive constituents of Chinese natural medicine VII: inhibitors of degranulation in RBL-2H3 cells and absolute sterostructures of three new diarylheptanoid glycosides from the bark of Myrica rubra. Chem Pharm Bull. 2002;50:208–215. doi: 10.1248/cpb.50.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead R, Pike DJ. Review of response surface methodology from a biometric viewpoint. Biometrics. 1975;31:803–851. doi: 10.2307/2529809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad KN, Kong KW, Ramanan RN, Azlan A, Ismail A. Determination and optimization of flavanoid and extract yield from brown mango using response surface methodology. Sep Sci Technol. 2012;47:73–80. doi: 10.1080/01496395.2011.606257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rao KS, Chaudhury PK, Pradhan A. Evaluation of anti-oxidant activities and total phenolic content of Chromolaena odorata. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:729–732. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohr GE, Meier B, Sticher O (2000) Analysis of procyanidins. Stud Nat Prod Chem 21(2):497–570

- Salawu MB, Acamovic T, Stewart CS, Roothaert RL. Composition and degradability of different fractions of Calliandra leaves, pods and seeds. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 1999;77:181–199. doi: 10.1016/S0377-8401(98)00259-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesier K, Harwat M, Boöhm V, Bitsch R. Assessment of antioxidant activity by using different in vitro methods. Free Radic Res. 2002;36(2):177–187. doi: 10.1080/10715760290006411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla S, Mehta A, Bajpai VK, Shukla S. In vitro antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of ethanolic leaf extract of Stevia rebaudiana Bert. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:2338–2343. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun BS, Ricardo-da-Silva JM, Spranger I. Critical factors of vanillin assay for catechins and proanthocyanidins. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:4267–4274. doi: 10.1021/jf980366j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xia QL, Chen JC, Wu D. Study on scavenging efficacy of phenols extraction of Myrica Ruba leaf. Food Sci. 2004;25:80–83. [Google Scholar]

- Xu GH, Liu DH, Chen JC, Ye XQ, Ma YQ, Shi J. Juice components and antioxidant capacity of citrus varieties cultivated in China. Food Chem. 2008;106:545–551. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.06.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HH, Ye XQ, Liu DH, Chen JC, Zhang JJ, Shen Y, Yu D. Characterization of unusual proanthocyanidins in peaves of bayberry (Myrica rubra Sieb. et Zucc.) J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:1622–1629. doi: 10.1021/jf103918v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LL, Wang YM, Wu DM, Xu M, Chen JH. Microwave-assisted extraction of polyphenols from Camellia oleifera fruit hull. Molecules. 2011;16:4428–4437. doi: 10.3390/molecules16064428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SH, Fang ZX, Lü Y, Chen JC, Liu DH, Ye XQ. Phenolics and antioxidant properties of bayberry (Myria rubra Sieb. et Zucc.) pomace. Food Chem. 2009;112:394–399. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.05.104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zou YH, Li GR. Analysis of flavonoid as antioxidant in Myrica Rubra Leaf with reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography. Chin J Anal Chem. 1998;26:531–534. [Google Scholar]