Abstract

The volatile compounds and protein profiles of Lighvan cheese, (raw traditional sheep cheese) were investigated over a 90-days ripening period. Solid-phase microextraction–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry [SPME–GC–MS] and sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis [SDS-PAGE] were used to identify volatile compounds and assess proteolysis assessment, respectively. Ripening breakdown products viz., acids (butanoic acid, 3 methyl butanoic acid, hexanoic acid, octanoic acid, decanoic acid,…) comprised of the highest number of detected individual compounds (10) followed by esters (9), alcohols (7), cyclic aromatic compounds (6), ketones (5) and aldehydes (4). Carboxylic acids were the dominant identified group; their levels increased during ripening and involved 48.22 % of the total volatile compounds at the end (90 days) of ripening. Esters, ketones, cyclic aromatic compounds and aldehydes also increased, whereas the alcohol content slightly decreased towards the end of the ripening. Degradation of β- and αS- casein was higher during the initial stage of ripening (1st month) of ripening than at later stages, which could be related to the inhibitory effect of salt on some bacteria and proteolytic enzymes.

Keywords: Lighvan cheese, Proteolysis, Ripening, Volatile compounds

Introduction

Lighvan cheese is a traditional, semi-hard, starter-free cheese from the Azerbaijan region, in the northwest of Iran, and made from raw Moghani sheep's milk. It is one of the most popular Iranian traditional cheeses, and its unique flavour is appreciated by consumers. Ripening of Lighvan cheese plays an important role in its characteristics.

Cheese flavour, a much sought after characteristic for the consumer, is determined by the equilibrium between numerous volatile and non-volatile components released during ripening (Fox and Wallace 1997). Flavour formation during cheese aging results from several biochemical pathways such as glycolysis, proteolysis of casein and lipolysis. Fat-derived compounds, such as free fatty acids, esters, lactones and ketones, are formed by lipolysis and lipid oxidation (Siek et al. 1971). Finally, free amino acids produced by proteolysis contribute to the taste of ripened cheese or can be converted into cheese flavour compounds.

Gas chromatography [GC] coupled to mass spectrometry [MS] is commonly used to analyze volatile compounds. Extraction and pre-concentration of the volatile fraction is a necessary step prior to GC-MS; for this purpose, solid-phase microextraction [SPME] is recommended. SPME is usually used for the extraction of volatile compounds from cheese (Delgado et al. 2010). The volatile profiles of some types of cheeses i.e. for Torta del Casar (Delgado et al. 2010), Idizabel (Barron et al. 2007) and Roncal (Izco and Torre 2000) cheeses have been previously studied.

Proteolysis is the major and the most complex biochemical pathway that occurs during the ripening of most types of cheeses. Electrophoretic methods such as SDS-PAGE are extensively used to assess primary proteolysis in cheeses. The difference in protein profiles produced during cheese ripening has been previously studied in some types of cheeses such as Cheddar cheese (Fox et al. 1993) and Grana Padano cheese (Gaiaschi et al. 2001).

In spite of the popularity of Lighvan cheese and its ever-growing consumption, there are only a few studies on its chemical composition and microbial profile (Abdi et al. 2006; Kafili et al. 2009; Aminifar et al. 2010). However, there are no studies on the biochemical changes and flavor formation of Lighvan cheese during ripening. The aim of this study is to investigate changes in volatile compounds and primary proteolysis during Lighvan cheese ripening. Precise recognition of these changes during aging provides crucial data for biochemical events that occur during aging, allowing for future intervention for eventual improvement of the cheese quality and reducing ripening time.

Materials and methods

Cheese making and sampling

Lighvan cheeses were prepared from raw Moghani sheep's milk (7.93 % fat, 19.7 % total solids, pH = 6.58) according to the method of Kafili et al. (2009). Lamb rennet was added to milk at 28 to 32 °C (depending on the season- from March to middle of May) to coagulate it. Then the coagulum was cut into walnut-sized pieces and they were transferred to rectangular cotton bags for whey drainage. After 4 hours, cotton bags were compressed under 4 kg weight for 2–4 h (depending on season) for better drainage of whey. Curd mass was cut into 25 × 25 × 25 cm3 cubes and the cubes were placed in a 22 % brine stream (8–10 °C) for 6 hours. Afterwards, the curd cubes were transferred to a basin. Sodium chloride crystals were strewn on its surface and they were stored for 3–5 days. In this stage, the cubes were turned upside down nine up to fifteen times for further removal of whey. The cubes were kept in 12 % salt brine (10 °C) for 3 months at an average temperature of 10 ± 2 °C.

Physiochemical properties

Physiochemical properties of cheese samples were analyzed at the beginning (day 1) and the end (day 90) of the ripening. The moisture content was measured according to the standard (4A) FIL-IDF (1982). Kirk and Sawyer's method (1991) was used to determine salt content. The pH of cheese samples was measured using a Knick 766 calimatic pH-meter (Niels, Bohrweg, Utrecht, The Netherlands). Total nitrogen and fat content of cheese samples were determined according to the Kjeldahl method (FIL-IDF 1993) and Gerber method (BSI 1969), respectively. All physicochemical properties were measured in triplicate, and SAS statistical software (version 8.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was applied for the statistical analysis of the experimental data. Multifactor analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the least significant difference (LSD) test (p < 0.05) was used to evaluate the effect of time on the physicochemical characteristics of cheese samples.

SPME–GC/MS

Seven Lighvan cheese samples were analyzed in triplicate at four different stages of ripening: 1, 30, 60 and 90 days. Extraction of volatile compounds during the ripening period was performed using the static headspace solid-phase microextraction [HS-SPME] method, and the compounds were analyzed by gas chromatography (Frank et al. 2004). The extraction of volatile compounds and their determination were performed as per the method of Condurso et al. (2008) with some modification for optimizing the technique. These modifications included changes in equilibrium and extraction temperatures and times which were at 40 °C for 20 min and 30 min, respectively.

DVB/CAR/PDMS [divinylbenzene/carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane] fiber, 50/30 μm film thickness bonded to a flexible fused silica core (Supelco), was selected for all extractions. SPME was carried out with a commercially accessible fiber housed in its manual holder (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA).

Six grams of finely grated cheese was dissolved in 12 mL water in a 40 mL vial and fitted with a self-sealing septum. SPME syringe (bearing a fiber) was introduced and maintained in the headspace. The samples were equilibrated for 10 min at 50 °C. Then the fiber coating was exposed to the headspace for 1 h at 60 °C. During the extraction period, the sample was stirred with a magnetic stir bar on a stir-plate rotating at 750 rpm. Finally, the fiber was inserted for 5 min into the injection port of the GC (splitless mode) adjusted to 250 °C for volatile-compounds desorption. The absorbed volatile compounds were analyzed by an Agilent HP 6890 N gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) equipped with an Agilent 5973 N mass-selective detector operating in electron impact mode (ionization voltage, 70 eV). The mass-selective detector was operated in the total ion current [TIC] mode, scanning from 20 to 500 m/z. Chromatographic data were recorded with HP Chemstation software using the Wiley 275 mass spectral library. A DB-Wax column capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm I.D., 0.5 μm film thickness) was used (Supelco). Helium (>99.999 % pure) was used as a carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.2 ml/min. The GC oven temperature program was as follows: initial temperature 45 °C for 1 min, then up to 250 °C with a heating rate of 5 °C/min and then was maintained for 5 min at that temperature. The GC-MS transfer line temperature was at 260 °C. n-Alkanes (Sigma R-8769) were examined under identical conditions to determine retention indices [RI] for the volatile compounds. Identification of compounds was performed by three methods: (1) comparison with commercial reference compounds produced by Sigma-Aldrich (France); (2) comparison of RI with those depicted in the literature; and (3) comparison of their mass spectra with those mentioned in the National institute of standards and technology [NIST] and Wiley 275 mass spectral libraries.

Proteolysis assessment

SDS-PAGE was carried out in accordance with the Kuchroo and Fox (1982) method to evaluate proteolysis during ripening after 1, 30, 60 and 90 days.

The Vertical System Hoefer SE 600 SERIES (Pharmacia Biotech, San Francisco, USA), along with 15 % acrylamide-bisacrylamide running gel and 5 % acrylamide-bisacrylamide stacking gel, were applied.

Extraction of proteins and peptides was performed following the method previously used by Vannini et al. (2008) for proteolysis assessment of Pecorino cheese: 5 g of Lighvan cheese was blended with 20 mL water for 3 min at 20 °C and stored at pH 4.6 (low pH was brought with HCl in water) at 40 °C for 1 h. The prepared samples were centrifuged at 3000 × g for 20 min at 5 °C. The pellets were mixed with 5 mL of 7 M urea and transferred to a freezer (−18 °C) until the SDS-PAGE analysis. Before the experiment, 2.5 mL 0.166 M Tris–1 mM ethylene-diamine-tetra-acetic acid [EDTA], pH 8 and 2.5 mL 7 % sodium dodecyl sulphate [SDS] were added to 150 mg of each prepared solution and centrifuged at 5000 × g at 4 °C for 20 min; then 1 mL of supernatant was heated for 5 min at 95 °C and 0.2 mL β-mercaptoethanol was added to it. This was followed by addition of 0.2 mL glycerol and 0.2 mL 0.02 % bromophenol to the prepared sample before injection into the gel. SDS-PAGE Molecular Weight Standards were used as standards (BioRad Laboratories, Munchen, Germany).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were carried out in triplicate and the analysis of variance [ANOVA] procedure of the SAS system software, Version 6, (1990, SAS Institute Inc., Cory, NJ, USA) was used to evaluate the differences in the volatile profiles during ripening. Mean values of the volatile compounds for different days of ripening were compared with Duncan's test. Evaluation was based on a significance level of p < 0.05. Microsoft Excel 2007 was used for drawing figures.

Results and discussion

Physiochemical properties

Physiochemical properties of Lighvan cheese at the beginning and the end of the ripening were shown in Table 1. pH value decreased from the beginning to the end of the ripening due to the lactose fermentation (Waagner-Nielsen 1993). Decrease in moisture content and increase in salt content of Lighvan cheese from day 1 to 90 could be related to the movement of water and salt from cheese texture and brine to brine and cheese blocks, respectively (Guinee and Fox 1993). Significant decrease of total nitrogen/dry matter [TN/DM] from day 1 to 90 is due to the diffusion of soluble nitrogenous compounds to brine which were produced as a result of proteolysis (Abd El-Salam et al. 1993). Increase in the fat percentage (%) from the beginning to the end of the ripening could be related to the moisture reduction during this period.

Table 1.

Physiochemical properties of Lighvan cheese at the beginning and the end of the ripening (n = 21)

| Physicochemical Characteristics | Ripening time(days) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 90 | |

| pH | 5.1a | 4.7b |

| Moisture content (%, w/w) | 69.4a | 62.1b |

| Salt (%, w/w) | 5.1b | 8.0a |

| TN/DM1 (%, w/w) | 5.7a | 4.5b |

| Fat (%, w/w) | 13.1b | 21.5a |

Means within the same row with different superscripts differ significantly (P < 0.05)

1 Total Nitrogen/Dry Matter

Identification of volatile compounds

Forty-one major volatile compounds were identified in ripened Lighvan cheese. Table 2 shows the development of Lighvan cheese volatile compounds (area units, AU × 105) during the ripening period (p < 0.05). Acids detected were predominant compounds (10) followed by esters (9), alcohols (7), cyclic aromatic compounds (6), ketones (5) and aldehydes (4). There was a considerable increase in total area units [AU] during cheese ripening (day 1: 113 × 105 AU, day 30: 254 × 105 AU, day 60: 320 × 105 AU, day 90: 464 × 105 AU). It is obvious that ripening time had a significant effect on the production of volatile compounds (p < 0.05). Trend of changes in volatile compounds during aging was not identical for different chemical groups as shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Means of volatile compounds (AU1 × 105) isolated from Lighvan cheese during ripening period (n = 21)

| RI2 | Id.3 Method | Compounds | Day 1 | Day 30 | Day 60 | Day 90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Acids | ||||||

| 1468 | 1, 2, 3 | Acetic acid | 0.56 d | 1.51 c | 6.87 b | 10.52 a |

| 1523 | 1, 2, 3 | Propanoic acid | 0.00 c | 0.02 c | 1.04 b | 1.81 a |

| 1649 | 1, 2, 3 | Butanoic acid | 0.69 d | 4.92 c | 7.82 b | 32.1 a |

| 1690 | 1, 2, 3 | 3-methyl butanoic acid | 0.77 c | 2.44 b | 4.86 b | 22.05 a |

| 1760 | 1, 3 | Pentanoic acid | 0.41 b | 0.55 b | 1.27 a | 0.56 b |

| 1870 | 1, 2, 3 | Hexanoic acid | 2.53 c | 3.69 c | 12.81b | 23.12 a |

| 1979 | 1, 3 | Heptanoic acid | 2.03 a | 1.06 b | 0.89 bc | 0.52 c |

| 2044 | 1, 3 | Octanoic acid | 10.92 d | 14.74 c | 24.05 b | 51.05 a |

| 2291 | 1, 3 | Decanoic acid | 25.14 d | 38.92 c | 64.67 a | 51.04 b |

| 2504 | 3 | Dodecanoic acid | 20.03 b | 54.47 a | 6.11 c | 30.73 b |

| %4 Esters | 55.33 | 48.07 | 40.76 | 48.22 | ||

| 892 | 1, 2, 3 | Acetic acid ethyl ester | 0.00 b | 5.44 a | 7.86 a | 3.55 a |

| 967 | 1, 3 | propanoic acid ethyl ester | 0.00 b | 0.11 b | 0.38 b | 1.35 a |

| 1057 | 1, 2, 3 | Butanoic acid, ethyl ester | 0.21 c | 1.52 c | 5.51 b | 10.39 a |

| 1133 | 3 | Acetic acid, 3-methylbutyl ester | 1.01 b | 3.05 ab | 2.29 ab | 4.78 a |

| 1247 | 1, 2, 3 | Hexanoic acid ethyl ester | 0.05b | 1.02 b | 6.03 a | 8.03 a |

| 1449 | 1, 2, 3 | Octanoic acid ethyl ester | 0.15 b | 1.58 b | 3.76 a | 6.34 a |

| 1535 | 1, 3 | Octanoic acid propyl ester | 0.00 b | 0.61 a | 1.75 a | 2.58 a |

| 1655 | 1, 2, 3 | Decanoic acid, ethyl ester | 2.02b | 3.96 b | 4.04 b | 28.47 a |

| 2352 | 3 | 9-Decenoic acid, ethyl ester | 0.00 c | 3.43 b | 5.51 ab | 10.57 a |

| % Ketones | 3.05 | 8.03 | 11.51 | 16.28 | ||

| 823 | 1, 2, 3 | 2-Propan-one | 0.79 b | 0.61 b | 2.9 a | 3.3 a |

| 911 | 2, 3 | 2-Butan-one | 0.52 c | 0.62 c | 11.0 b | 16.6 a |

| 1358 | 2, 3 | 3-Hydroxy-2-butan-one | 0.11 b | 1.4 a | 2.0 a | 1.9 a |

| 1404 | 3 | 2-Decanone | 0.00b | 0.80 a | 1.2 a | 2.2 a |

| 2001 | 3 | 4-octen-3-one | 0.57 b | 30.4 a | 28.7 a | 29.3 a |

| % Alcohols | 1.72 | 13.31 | 14.37 | 11.50 | ||

| 947 | 3 | ethanol | 3.3 b | 3.7 b | 15.5 a | 16.6 a |

| 1064 | 2, 3 | 1-propanol | 0.00 b | 0.00 b | 4.4 a | 4.4 a |

| 1140 | 1, 2, 3 | 1-butanol | 0.17 b | 0.11 b | 0.14 b | 0.56 a |

| 1224 | 1, 2, 3 | 3-Methyl-1-butan-ol | 22.3 a | 22.2 a | 20.4 a | 3.8 b |

| 1255 | 2, 3 | 1-pentanol | 0.50 b | 0.55 b | 0.63 b | 2.8 a |

| 1369 | 2, 3 | 1-hexanol | 1.3 ab | 1.6 a | 0.90 ab | 0.25 b |

| – | 3 | 1-Tetradecanol | 2.0 a | 1.0 a | 0.50 c | 0.00 d |

| % Aromatic | 26.01 | 11.52 | 13.38 | 6.10 | ||

| 1156 | 2, 3 | 1,3-di methyl benzene | 0.26 c | 2.5 a | 0.98 b | 0.72 b |

| 1213 | 2, 3 | limonene | 0.35 c | 1.4 b | 3.5 ab | 5.2 a |

| 1535 | 2, 3 | Benzaldehyde | 0.00 b | 0.00 b | 1.1 a | 1.2 a |

| 1792 | 2, 3 | 4-isopropyl benzaldehyde | 2. 7 b | 24.4 a | 24.3 a | 25.7 a |

| 1936 | 1, 2, 3 | 2-Phenylethanol | 0.71 c | 5.1 b | 13.5 a | 12.4a |

| – | 3 | Phenol | 0.57 b | 2.3 b | 4.2 ab | 9.6 a |

| % Aldehydes | 4.01 | 14.04 | 14.96 | 11.88 | ||

| 500 | 2, 3 | Acetaldehyde | 9.5 b | 11.7 b | 11.6 b | 19.0 a |

| 912 | 2, 3 | 3-Methylbutanal | 1.2 a | 0.62 b | 0.59 b | 0.47 b |

| 1415 | 3 | 2,4-Hexa-dienal | 0.38 | 0.66 | 0.23 | 0.31 |

| 1935 | 2, 3 | tetradecanal | 0.00 b | 0.00 b | 4.8 b | 8.3 a |

| 9.82 | 5.13 | 5.46 | 6.02 | |||

a–d: Means within a row with different superscripts differ significantly (P < 0.05)

1 AU: Area Unit, 2RI: Retention Index, 3Id: Identification, 4Percentage (%) = Percentage of volatile compounds of each chemical group during maturation

Identification method: 1 = Retention time and mass spectrum same with a reference compound; 2: retention index and mass spectrum are identical with a literature; 3, tentative identification by mass spectrum

Table 3.

Means of the important volatile compounds groups (AU × 105) extracted from Lighvan cheese during aging (n = 21)

| Day1 | Day30 | Day60 | Day90 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acids | 62.9c | 122.0b | 130.2b | 223.6a |

| Esters | 3.4d | 20.4c | 36.8b | 75.3a |

| Ketones | 2.0c | 33.8b | 45.7ab | 53.3a |

| Alcohols | 29.6b | 32.2b | 42.5a | 28.4b |

| Aromatic | 4.5c | 35.7b | 47.7ab | 54.8a |

| Aldehydes | 11.1b | 13.0b | 17.2b | 28.1a |

a–d: Mean with different superscripts were significantly different from each other during ripening (P < 0.05)

Total carboxylic acid content increased significantly during cheese ripening. Their quantity was more considerable (40.66 to 55.38 % of total compounds) than other identified chemical groups (Table 2). Ester level had considerably increased during ripening from day 1 (3.44 × 105 AU) to 90 day (75.29 × 105 AU). Their quantity in the headspace of ripened Lighvan cheese was also significant. Likewise, ketones changed similarly from day 1 (1.99 × 105 AU) to 90 day (53.32 × 105 AU) in Lighvan cheese, responsible for its aroma (Table 3).

The pattern of changes in various alcohols was different during ripening. Ethanol, 1-propanol, 1-butanol and 1-pentanol increased during Lighvan cheese ripening, but 1-hexanol, 1-tetradecanol and 3-methyl-1-butanol decreased with progress of ripening. Most aromatic compounds increased during Lighvan cheese ripening. Thus, the levels of limonene, benzaldehyde, 4-isopropyl benzaldehyde, 2-phenylethanol and phenol at day 90 were significantly higher than at the start of ripening. Level of 1, 3-di methyl benzene was the highest at 30th days of ripening, which decreased on further ripening. Aldehydes levels were in low concentrations in ripe Lighvan cheese compared to other volatile compounds. Their level, in general, increased from day 1 to 90th (Table 3). Acetaldehyde increased from day 1 till the end of the ripening. Tetradecanal was only identified after 60 days of ripening and reached its highest level at 90th day. The level of 2, 4-hexa-dienal did not change whereas 3-methylbutanal decreased during Lighvan cheese aging (Table 2).

Carboxylic acids

Table 2 shows that short and medium-chain carboxylic acids play an important role in Lighvan cheese aroma. They not only are typical odorant compounds with low thresholds but can convert other aromatic compounds such as alcohols, methyl ketones, lactones, aldehydes and esters (Collins et al. 2003). Butanoic, hexanoic and octanoic acids are the most abundant volatile acids in a wide variety of cheeses (Barbieri et al. 1994).

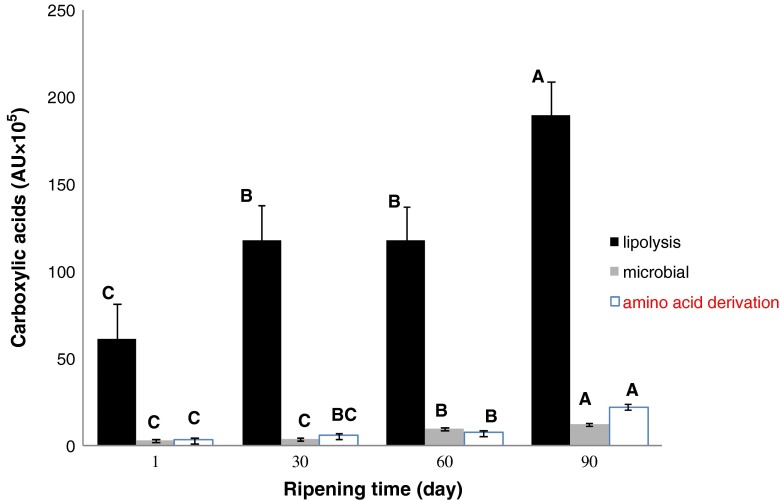

Lipolysis, proteolysis and lactose fermentation are three main pathways in carboxylic acids formation (Curioni and Bosset 2002). During cheese ripening, depending on processing, micro flora and ripening conditions, one of these pathways will be dominant. Figure 1 shows the development of carboxylic acids according to their source. On day 1, lipolysis was the main source of acids (butanoic, pentanoic, hexanoic, heptanoic, octanoic, decanoic and dodecanoic acids) in Lighvan cheese, whereas those derived from amino acids or microbial origin (as a result from fermentative activity of microorganisms-acetic and propanoic acid-) were negligible. Acids originating from lipolysis showed an increasing trend in the first month of ripening; thereafter it remained constant till 60th day and then again increased. The amino acid-derived 3-methyl butanoic acid was insignificant in first month of ripening, and then increased until day 90. The amount of acids resulting from microbial activity was negligible in the first month, and then tended to increase until 90th day. Previously Delgado et al. (2010) showed that while carboxylic acids originating through lipolysis were dominant on day 1, microbial originated acids were dominant after ripening (90th day). Formation of linear chain carboxylic acids (butanoic, pentanoic, hexanoic, heptanoic, octanoic, decanoic and dodecanoic acids) could be related to lipases and esterases activity during maturation (Barbieri et al. 1994). Because Lighvan cheese is made from raw milk and starter is not used in its production, indigenous milk lipases and lipases from natural microbial flora are responsible for lipolysis. High amounts of these acids contributed to vinegar odour and slight acid taste of cheese.

Fig. 1.

Change in carboxylic acids originating from microbial activity, lipolysis and amino acid derivation during ripening (n = 21). Means with the same color with different superscripts differ significantly (P < 0.05) during ripening

Because carboxylic acids can get transformed into other compounds such as methyl ketones, lactones, alcohols, aldehydes and esters (Collins et al. 2003), the constancy in lipolysis-derived acids between day 30 and day 60 could be related to the equilibrium between the production of carboxylic acids by lipolytic enzymes and their conversion to other compounds. Branched-chain, 3-methyl butanoic acid increase could be related to deamination of leucine during proteolysis (Barbieri et al. 1994). Fermentative activity of microorganisms is responsible for increased production of acetic and propanoic acids (Di Cagno et al. 2003). This may be due to the increase in lactobacilli population during ripening of Lighvan cheese (Kafili et al. 2009).

Esters

Nine esters were identified in Lighvan cheese, particularly those produced by butanoic acid and decanoic acid with ethanol. Presence of ethyl esters of even-numbered fatty acids is reported in different kinds of cheeses. Esters such as butanoic acid ethyl ester and hexanoic acid ethyl ester are important odorants in Cheddar, Emmental, and Torta del Casar cheeses (Curioni and Bosset 2002; Delgado et al. 2010). The aroma of Lighvan cheese is affected by the presence of ethyl esters, because of their high amount and low detection threshold values.

Ester formation during cheese ripening is probably related to the esterase activity of lactic acid bacteria. Production of esters via alcoholysis in aqueous systems occurs as a result of lactic acid bacteria esterase activity (Liu et al. 2003). It has been demonstrated that esterase activity of Lactobacillus helveticus, Lactobacillus casei and Lactococcus lactis is responsible for the accumulation of esters during ripening of a simulated Parmesan cheese (Fenster et al. 2003). Levels of esters were insignificant at day 1 and increased until the end of ripening. Such an increase could be associated with an increase in the population of LAB during ripening (Kafili et al. 2009).

The increase of some esters, such as decanoic acid ethyl ester, could be related to the reduction in decanoic acid towards the end of ripening. Furthermore, the decrease of 3-methyl 1-butanol towards the end of ripening could be associated with an increase in acetic acid, 3-methylbutyl ester content. The increasing trend in the concentration of acetic acid, 3-methylbutyl ester has been reported for Torta del Casar (raw ewe’s milk cheese) (Delgado et al. 2010). An increase in the hexanoic acid ethyl ester and butanoic acid ethyl ester during ripening has been reported in few types of ewe’s milk cheeses (Barron et al. 2007; Delgado et al. 2010). Some researchers believe that esters had a positive effect on cheese flavour because the rancid flavour from excessive amounts of carboxylic acids is masked by fruity notes provided by ethyl esters (de Frutos et al. 1991).

Ketones

Ketones are considered an important constituent of the volatile profile of most cheeses (Barbieri et al. 1994). Ketones are basically odorant compounds with low perception thresholds. Two-butan-one and 4-octen-3-one were the most abundant ketones in ripened Lighvan cheese. Negligible at day 1, they increased during ripening indicating that they have a considerable role in the aroma of ripened Lighvan cheese. The compound 4-octen-3-one has not been previously isolated in other ewe’s milk cheeses. Hence, it could be associated with the Lighvan cheese flavour. The increasing trend of 2-butan-one during ripening has been reported for raw ewe’s milk cheeses such as Torta del Casar cheeses (Delgado et al. 2010). 2-propan-one, 2-decanone and 3-hydroxy-2-butan-one (acetoin) increased during cheese ripening. At day 1, 2-propan-one was the dominant ketone; and it is probably produced in the sheep's mammary gland and transferred to the milk (Castillo et al. 2007) but its further increase during ripening could be associated with butanoic acid derivation. Production of 3-hydroxy-2-butan-one (acetoin) during cheese aging could be related to reduction in diacetyl content (Izco and Torre 2000), which resulted from lactose and citrate metabolism by lactococci bacteria (Yvon 2006).

Alcohols

Seven alcohols were found in ripened Lighvan cheese: ethanol, 1-propanol, 1-butanol, 1-pentanol, 1-hexanol, 1-tetradecanol and 3-methyl-1-butanol. Production of ethanol could be associated with lactose or citrate fermentation (Marilley and Casey 2004). 1-propanol, 1-butanol, 1-pentanol, 1-hexanol and tetradecanol are supposed to be derived from the corresponding aldehydes that originated from fatty acids and amino acids metabolism (Barbieri et al. 1994). Finally, production of 3-methyl-1-butanol could be related to the reduction in 3-methyl butanal produced from leucine by Strecker degradation (Mc Sweeney and Sousa 2000).

It seems that diversity in the metabolic pathways involved in alcohol formation in cheese is responsible for different patterns of alcohol changes during ripening (Molimard and Spinnler 1996).

Cyclic aromatic compounds

1,3-Di methyl benzene, limonene, benzaldehyde, 4-isopropyl benzaldehyde, 2-phenylethanol and phenol are six aromatic compounds which were identified in Lighvan cheese and their levels increased during ripening. Among aromatic compounds, presence of limonene (terpene) in cheeses is probably related to animal feed, and not to the ripening process (Di Cagno et al. 2003). limonene has been detected in other cheese, such as Parmigiano Reggiano (Barbieri et al. 1994). The benzaldehyde formation, which is responsible for bitter almond notes in cheese (Molimard and Spinnler 1996), may be related to α-oxidation of phenyl acetaldehyde derived from phenylalanine, via Strecker reaction (Sieber et al. 1995). On the other hand, yeast metabolism is responsible for the production of 2-phenylethanol (Correa Lelles Nogueira et al. 2005). The presence of some yeasts during Lighvan cheese ripening has been previously reported (Kafili et al. 2009) and they could play an important role in production of 2-phenylethanol.

Aldehydes

Acetaldehyde, 3-methylbutanal, 2, 4-Hexa-dienal and tetradecanal were identified in ripened Lighvan cheese. Among them, acetaldehyde and tetradecanal increase during ripening time, but 2, 4-Hexa-dienal did not change and 3-methylbutanal decreased during this time. Presence of aldehydes at low level compared to other volatile compounds could be an indicator of optimal maturation of cheeses. Acetaldehyde, 3-methylbutanal, 2, 4-hexa-dienal and tetradecanal gets converted to their corresponding acids or alcohols, and hence are not found at high levels in cheese (Lemieux and Simard 1992). Acetaldehyde, a product of lactose metabolism or ethanol oxidation (Mc Sweeney and Sousa 2000) is responsible for a sharp, penetrating and fruity note in some types of cheeses (Barbieri et al. 1994). Tetra-decanal and 2, 4-hexa-dienal could be generated from oxidation of their respective alcohols. Consequently, oxidation of 1-tetradecan-ol is responsible for tetra-decanal production. 3-methyl butanal is formed from leucine metabolism (Urbach 1995).

Assessment of proteolysis

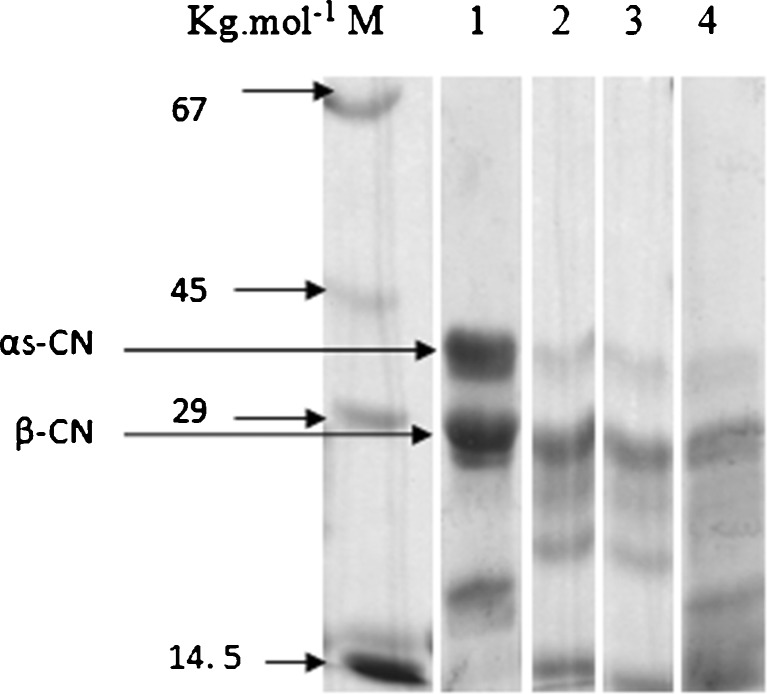

Figure 2 shows electrophoretograms of Lighvan cheese samples at 1 (fresh), 30, 60 and 90 days of ripening. Comparison among electrophoretograms showed that the protein profile changed considerably during the first month of ripening than at later stages. During the first month, β- and αS- caseins degraded significantly and hence lower intensities of their bands were observed.

Fig. 2.

SDS-PAGE profiles of Lighvan cheese. Protein profiles after 1, 30, 60 and 90 days of ripening are shown in lanes 1, 2, 3, 4 respectively. Lane M: Molecular mass marker

The β- and αS- caseins breakdown is commonly related to proteolytic activity of rennet and plasmin – they are residual enzymes in the curd – and to the proteolytic enzymes of non-starter bacteria. Enterococcus faecalis and Streptococcus parauberis, identified in the first month of Lighvan cheese ripening (Kafili et al. 2009), could play an important role in casein degradation. As ripening time continued from 30 to 60 days, the intensities of bands did not change considerably; this may be related to the inhibitory effect of salt on proteolytic bacteria (Kafili et al. 2009) and proteolysis (Guinee and Fox 1993). Salt in the moisture of curd – which varies with ripening time and reached to its maximum level after 30 days (Aminifar et al. 2010) – affects the activity of proteolytic enzymes (Gaiaschi et al. 2001) and growth of some bacteria such as E. faecalis and S. parauberis (Kafili et al. 2009). There was absence of E. faecalis and S. parauberis reported after 45 and 75 days of Lighvan cheese ripening, respectively (Kafili et al. 2009). From 60 to 90 days the former bands became fainter and bands corresponding to β- and αS- casein degradation products were apparent. According to Kafili et al. (2009), although most of proteolytic bacteria were inhibited after 75 days, but some of lactobacilli like Lb. plantarum and lactococci like L. lactis were reported after 75 and 90 days which were responsible for limited proteolysis from 60 to 90-days. Previously, Fox et al. (1993) reported the contribution of Lb. plantarum and L. lactis to proteolysis.

Conclusion

This study was aimed to monitor the proteolysis of Lighvan cheese during ripening and characterize the volatile fraction produced, responsible for the flavor of cheese. The results showed that carboxylic acids, esters, ketones, cyclic aromatic compounds and aldehydes increased during the ripening.

Carboxylic acids were the dominant volatile compounds in ripened Lighvan cheese (48.22 % of total compounds). The carboxylic acids derived from lipolysis had a greater role in flavour production than those that originated from microbial fermentative activity and amino-acid degradation. Degradation of β- and αS- casein during the initial period (i.e. first month) of Lighvan cheese ripening was greater than at other stages of ripening. The inhibitory effect of salt on some bacteria and proteolytic enzymes could be related to decrease in the proteolysis rate after 30 days of ripening.

References

- Abd El-Salam MH, Alichanidis E, Zerfiridis GK. Domiati and Feta-type cheese. In: Fox PF, editor. Cheese: chemistry, physics and microbiology. London: Chapman and Hall; 1993. pp. 301–335. [Google Scholar]

- Abdi R, Sheikh-Zeinoddin M, Soleimanian-Zad Z. Identification of lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditional Iranian Lighvan cheese. Pak J Biol Sci. 2006;9:99–103. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2006.99.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aminifar M, Hamedi M, Emam-Djomeh Z, Mehdinia A. Microstructural, compositional and textural properties during ripening of Lighvan cheese, a traditional raw sheep cheese. J Texture Stud. 2010;41:579–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4603.2010.00244.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri G, Bolzoni L, Careri M, Mangia A, Parolari G, Spagnoli S, Virgili R. Study of the volatile fraction of Parmesan cheese. J Agric Food Chem. 1994;42:1170–1176. doi: 10.1021/jf00041a023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barron LJR, Redondo Y, Aramburu M, Gil P, Pérez-Elortondo FJ, Albisu M, Nájera AI, de Renobales M, Fernández-García E. Volatile composition and sensory properties of industrially produced Idiazabal cheese. Int Dairy J. 2007;17:1401–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2007.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- BSI Standard 696, part 2 (1969) Gerber method for the determination of fat in milk and milk products. BSI 969–2:180–187

- Castillo I, Calvo M, Alonso L, Juárez M, Fontecha J. Changes in lipolysis and volatile fraction of a goat cheese manufactured employing a hygienized rennet paste and a defined strain starter. Food Chem. 2007;100:590–598. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.09.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins Y, Mc Sweeney P, Wilkinson M. Lipolysis and free fatty acid catabolism in cheese: a review of current knowledge. Int Dairy J. 2003;13:841–866. doi: 10.1016/S0958-6946(03)00109-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Condurso C, Verzera A, Romeo V, Ziino M, Conte F. Solid-phase microextraction and gas chromatography mass spectrometry analysis of dairy product volatiles for the determination of shelf-life. Int Dairy J. 2008;18:819–825. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2007.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Correa Lelles Nogueira M, Luachevsky G, Rankin SA. A study of volatile composition of Minas cheese. Lebensm Wiss Technol. 2005;38:555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2004.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curioni P, Bosset J. Review: Key odorants in various cheese types as determined by gas chromatography–olfactometry. Int Dairy J. 2002;12:959–984. doi: 10.1016/S0958-6946(02)00124-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Frutos M, Sanz J, Martinez-Castro J. Characterization of Artisanal cheeses by GC/MS analysis of their medium volatile (SDE) fraction. J Agric Food Chem. 1991;39:524–530. doi: 10.1021/jf00003a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado FJ, González-Crespo J, Cava R, García-Parra J, Ramírez R. Characterisation by SPME–GC–MS of the volatile profile of a Spanish soft cheese P.D.O. Torta del Casar during ripening. Food Chem. 2010;118:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.04.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cagno R, Banks J, Sheehan L, Fox PF, Brechany EY, Corsetti A, Gobbetti M. Comparison of the microbiological, compositional, biochemical, volatile profile and sensory characteristics of three Italian PDO ewes’ milk cheeses. Int Dairy J. 2003;13:961–972. doi: 10.1016/S0958-6946(03)00145-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fenster K, Rankin S, Steele J. Accumulation of short n-chain ethyl esters by esterases of lactic acid bacteria under conditions simulating ripening Parmesan cheese. J Dairy Sci. 2003;86:2818–2825. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)73879-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FIL-IDF Standard 20A (1993) Milk. Determination of nitrogen content, protein-nitrogen content, and non-protein-nitrogen content (Kjeldahl method). Int Dairy Fed 20A:83–102

- FIL-IDF Standard 4A (1982) Cheese and processed cheese. Determination of the total solids content (reference method). Int Dairy Fed 4A:110–115

- Fox PF, Law J, Mc Sweeney PLH, Wallace J. Biochemistry of cheese ripening. In: Fox PF, editor. Cheese: chemistry, physics and microbiology. 2. London: Chapman and Hall; 1993. pp. 389–421. [Google Scholar]

- Fox PF, Wallace JM. Formation of flavour compounds in cheese. Adv Appl Microbiol. 1997;45:17–85. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(08)70261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank DC, Owen CM, Patterson J. Solid phase microextraction (SPME) combined with gas-chromatography and oflactometry-mass spectrometry for characterization of cheese aroma compounds. LWT. 2004;37(2):139–154. doi: 10.1016/S0023-6438(03)00144-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaiaschi A, Beretta B, Poiesi C, Conti A, Giuffrida MG, Galli CL, Restani P. Proteolysis of β-casein as a marker of Grana Padano cheese ripening. J Dairy Sci. 2001;84:60–65. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(01)74452-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinee TP, Fox PF. Salt in cheese: physical, chemical and biological aspects. In: Fox PF, editor. Cheese: chemistry, physics and microbiology. 2. London: Chapman and Hall; 1993. pp. 257–302. [Google Scholar]

- Izco JM, Torre P. Characterisation of volatile flavour compounds in Roncal cheese extracted by the purge and trap method and analyzed by GC–MS. Food Chem. 2000;70:409–417. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(00)00100-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kafili T, Razavi SH, Emam-Djomeh Z, Naghavi MR, Alvarez-Martin P, Mayo B. Microbial characterization of Iranian traditional Lighvan cheese over manufacturing and ripening via culturing and PCR-DGGE analysis: identification and typing of dominant lactobacilli. Eur Food Res. 2009;229:83–92. doi: 10.1007/s00217-009-1028-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk RS, Sawyer R (1991) Pearson's composition and analysis of foods (9th ed.). Longman Science and Technical, Harlow, Essex

- Kuchroo CN, Fox PF. Soluble nitrogen in Cheddar cheese: comparison of extraction procedures. Milchwiss. 1982;37:331–335. [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux L, Simard RE. Bitter flavour in dairy products. A review of bitter peptides from caseins: their formation, isolation and identification, structure masking and inhibition. Le Lait. 1992;72:335–382. doi: 10.1051/lait:1992426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SQ, Holland R, Crow VL. Ester synthesis in an aqueous environment by Streptococcus thermophilus and other dairy lactic acid bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003;63:81–88. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1355-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marilley L, Casey MG. Review: flavours of cheese products: metabolic pathways, analytical tools and identification of producing strains. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;90:139–159. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mc Sweeney P, Sousa M. Review: biochemical pathways for the production of flavour compounds in cheeses during ripening. Le Lait. 2000;80:293–324. doi: 10.1051/lait:2000127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molimard P, Spinnler H. Review: compounds involved in the flavour of surface mold-ripened cheeses: origins and properties. J Dairy Sci. 1996;79:169–184. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(96)76348-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber R, Buetikofer U, Bosset JO. Benzoic acid as a natural compound in cultured dairy products and cheese. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:227–246. [Google Scholar]

- Siek TJ, Albin IA, Sather LA, Lindsay RC. Comparison of flavour thresholds of aliphatic lactones with those of fatty acids, esters, aldehydes, alcohols, and ketones. J Dairy Sci. 1971;54:1–4. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(71)85770-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Urbach G. Contribution of lactic acid bacteria to flavour compound formation in dairy products. Int Dairy J. 1995;5:877–903. doi: 10.1016/0958-6946(95)00037-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vannini L, Patrignani F, Iucci L, Ndagijimana M, Vallicelli M, Lanciotti R, Guerzoni ME. Effect of a pre-treatment of milk with high pressure homogenization on yield as well as on microbiological, lipolytic and proteolytic patterns of “Pecorino” cheese. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;128:329–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waagner-Nielsen E. North European varieties of cheese. In: Fox PF, editor. Cheese: chemistry, physics and microbiology. London: Chapman and Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Yvon M. Key enzymes for flavour formation by lactic acid bacteria. Aust J Dairy Technol. 2006;61:16–24. [Google Scholar]