Abstract

The enantioselective synthesis of two novel cyclopropane-fused diazabicyclooctanones is reported here. Starting from butadiene monoxide, the key enone intermediate 7 was prepared in six steps. Subsequent stereoselective introduction of the cyclopropane group and further transformation led to compounds 1a and 1b as their corresponding sodium salt. The great disparity regarding their hydrolytic stability was rationalized by the steric interaction between the cyclopropyl methylene and urea carbonyl. These two novel β-lactamase inhibitors were active against class A, C, and D enzymes.

Keywords: β-lactamase inhibitor, asymmetric synthesis, hydrolytic stability

Since the discovery of penicillin in the 1920s, β-lactam antibiotics have become one of the most important groups of antibiotics. The worldwide usage of these antibiotics has rapidly led to the development of bacterial resistance, mainly by the production and evolution of β-lactamases, which are enzymes responsible for efficiently catalyzing the hydrolysis of the β-lactam warheads. According to the Ambler classification,1−3 β-lactamases are divided into four subfamilies: class A, C, and D enzymes have a key serine residue in the active site, whereas class B enzymes (also called metallo-β-lactamases) employ either one or two zinc ions.

The combination use of several mechanism-based β-lactamase inhibitors (clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and tazobactam) with β-lactam antibiotics is currently one of the most successful strategies in combating such resistance,4−6 as evident by the wide clinical application of products such as Augmentin, Timentin, Unasyn, Sulperazone, and Zosyn. However, these β-lactamase inhibitors only have activity against class A β-lactamases and weak or no activity against class C and D enzymes.4 In addition, β-lactamases are rapidly evolving, as evident by the rising number of new β-lactamases reported each year (over 1400 to date).7 Therefore, this urgent medical need calls for firm commitment to the discovery and development of novel and more efficient inhibitors with broader coverage of β-lactamases.

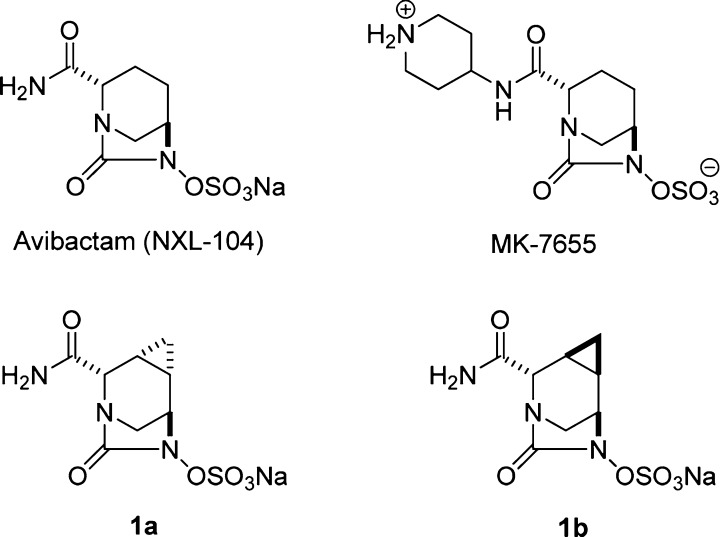

Recently a novel series of β-lactamase inhibitors based on the diazabicyclooctanone (DBO) scaffold was reported.8−10 Avibactam (NXL104)11−13 and MK-7655,14−16 with their common bicyclic urea structure (Figure 1), were reported to have limited intrinsic antibiotic activity, but are capable of inhibiting classes A and C and a limited number of class D β-lactamases.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of selected examples of diazabicyclooctanones (DBO).

This letter describes our efforts toward the enantioselective synthesis of two new cyclopropane-fused diazabicyclooctanones 1a and 1b aiming to explore whether the introduction of additional ring strain can lead to higher reactivity of the urea carbonyl and broader β-lactamase coverage, while hoping to maintain sufficient hydrolytic stability.

As shown in Scheme 1, the synthesis started with the Pd-catalyzed dynamic kinetic asymmetric transformation (DYKAT) of racemic butadiene monoxide 2 employing phthalimide, Pd(allyl)2Cl2, and the (R,R)-DACH-naphthyl ligand.17 This reaction was highly reproducible and scalable, and alcohol 3 was consistently obtained in >90% yield and >95% ee on >100 g scale. Subsequent TBS protection and treatment with hydrazine in methanol gave amine 4 in high yield. Over reduction of the alkene by hydrazine was sometimes observed but could be controlled by limiting the reaction time. Monoalkylation of the primary amine, followed by Boc protection, afforded the Weinreb amide 5 in 66% yield. It is noteworthy that numerous attempts (various bases, solvents, additives, and temperatures) to alkylate the Boc carbamate of amine 4 led to low conversion. The addition of propenylmagnesium bromide to Weinreb amide 5 gave vinyl ketone 6, which was then treated with 2 mol % of the second generation Hoveyda–Grubbs catalyst18 in hot toluene to form the enone ring in good yield. The use of propenylmagnesium bromide led to higher yields in both the vinyl ketone formation and metathesis steps relative to vinylmagnesium bromide.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Key Enone Intermediate 7.

With enone intermediate 7 in hand, we next explored the introduction of the cis-cyclopropane ring (Scheme 2). Stereoselective Luche reduction19 of the enone gave allylic alcohol 8 as a single diastereomer in 65% yield. The stereochemical outcome of this transformation was confirmed by an observed nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) from the TBS ether methylene group to the axial proton H6a (Figure 2). In addition, proton H6a was determined to be axial due to its large trans diaxial coupling constant with proton H5a (10.5 Hz). Hydroxyl-directed cyclopropanation of allylic alcohol 8 under Denmark’s modified conditions20 afforded compound 9 as a single diastereomer in 77% yield. The cyclopropanation of the double bond occurred on the same face of the alcohol group as confirmed by the presence of NOEs observed in compound 9 (Figure 2). Alcohol 9 was then converted to compound 10 under Mitsunobu conditions using dinitrobenzenesulfonyl protected O-benzylhydroxylamine.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Compound 1a.

Figure 2.

Assignment of relative stereochemistry by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). Each double arrow indicates a signal observed in the NOE experiments.

Selective deprotection of the Boc group in the presence of the TBS ether was achieved employing either TBSOTf21 or ZnBr222,23 in comparable yields. Subsequent removal of the nitrobenzenesulfonyl group gave free diamine 11 in 50% yield over 2 steps.

The bicyclic urea ring was formed via slow addition of a triphosgene solution to a dilute solution of diamine and Hünig’s base in CH3CN at 0 °C. The TBS ether was removed with TBAF. The resulting alcohol 13 (relative stereochemistry confirmed by X-ray analysis, see Supporting Information) was oxidized to the corresponding carboxylic acid 14 under mild conditions using catalytic CrO3,24 which was then converted to primary amide 15. NOE experiments confirmed the stereochemistry at C2 remained intact through the oxidation and amide coupling steps (Figure 2). This could be explained by the rigid nature of the DBO scaffold where the highly strained system prevents the formation of the required tautomer to allow the epimerization to occur. Next the benzyl group was removed under catalytic hydrogenolysis conditions. After filtration and concentration, the N-hydroxide intermediate was treated with excess SO3–pyridine complex in pyridine to drive the sulfate formation. Finally target compound 1a was isolated as its sodium salt after treatment with NaOH preconditioned Dowex ion-exchange resin.

Next we turned our attention to the preparation of the other cyclopropane diastereomer 1b. We reasoned that this could be accomplished by carrying out the cyclopropanation before formation of the alcohol, thus relying on steric hindrance to direct the stereochemical outcome of the reaction. As shown in Scheme 3, slow addition of enone 7 to a dilute solution (∼0.05 M) of preformed sulfoxonium ylide25,26 in THF resulted in the formation of the cyclopropane 16 in good yield. The trans stereochemistry was established by NOE experiments (Figure 2). We hypothesized that the reduction of an oxime derived from ketone 16 would stereoselectively provide the desired trans-isomer due to the steric hindrance of the cyclopropane ring. To this end, ketone 16 was readily converted to the O-benzyl oxime, which was subsequently reduced to hydroxylamine 17 using a large excess of NaBH3CN and boron trifluoride-diethyl etherate, albeit in moderate yield. Selective removal of the Boc group, followed by urea formation, led to the formation of the bicyclic urea 19. The relative stereochemistry of the rigid bicyclic urea 19 was readily determined by NOE experiments to be the undesired cis isomer (Figure 2). It is therefore clear that the presence or absence of the cyclopropane did not play a role in the stereoselectivity of the ketone reduction. As in the stereoselective reduction of enone 7 (Scheme 2), the large TBS ether group in its pseudoaxial position directed the axial attack of the hydride on the carbonyl/oxime group.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Urea 19.

Alternatively, cyclopropanone 16 was reduced with a sterically undemanding NaBH4 at 0 °C to provide the cis alcohol 20 in excellent yield and greater than 10 to 1 diastereoselectivity (Scheme 4). Following the previously established synthetic sequence used for the preparation of compound 1a, alcohol 20 was converted to primary amide 25. Catalytic hydrogenolysis of 25 to remove the benzyl protective group, sulfate formation, ion exchange, and RP-HPLC purification furnished the final compound 1b as its sodium salt in 45% yield over the final 3 steps. As shown in Figure 3, confirmation of the structure of 1b was obtained via a small molecule crystal structure.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of compound 1b.

Figure 3.

X-ray crystal structure of 1b.

With diastereomeric cyclopropane analogues 1a and 1b in hand, we examined their hydrolytic stability in pH 7.4 (aqueous phosphate buffer). Compound 1a was stable with a half-life of 112 h at 37 °C. As expected, at elevated temperature (70 °C), the half-life of 1a was significantly shorter (8.2 h). Compound 1b was remarkably more stable, as evident by its long half-life (>264 h) even at 70 °C in pH 7.4 aqueous phosphate buffer. As a reference, the half-life of the known β-lactamase inhibitor tazobactam in the same conditions was measured at 7.7 h, a value very similar to that of compound 1a.

The exceptional stability of 1b may be rationalized by its concave conformation (Figure 3). The rigid tricyclic structure and particular stereochemistry places the cyclopropane methylene group of 1b in close proximity (C2–C7 distance = 2.48 Å) to the carbonyl group of the cyclic urea. This may provide a strong steric protection from the addition of water and also destabilize the tetrahedral intermediate that would be formed during hydrolysis.

Furthermore, the two novel cyclopropane-containing DBOs 1a and 1b, together with tazobactam were profiled for their inhibitory activities against a series of β-lactamases. As presented in Table 1, both analogues showed activity against class A, C, and D β-lactamases. This suggests that the measurement of hydrolytic stability is not enough to predict reactivity with β-lactamases. Additional factors like molecular recognition and acylation rates come into play in the stepwise mechanism of covalent inhibition.27,28 While the levels of inhibition were variable across the 3 families of β-lactamases, the structure–activity relationship (SAR) between the two new analogues and tazobactam represents useful information to design the next generation of DBO-based β-lactamase inhibitors. The increased hydrolytic stability for those new inhibitors will also represent an advantage in terms of formulation development and manufacturing.

Table 1. Enzyme Inhibition against Different Classes of β-Lactamases.

| class

A IC50 (μM) |

class C IC50 (μM) | class D IC50 (μM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | CTX-M-15 K. pneumoniae | KPC-2 E. cloacae | AmpC P. aeruginosa | OXA-48 K. pneumoniae |

| Tazobactam | <0.007 | 39 | 3.4 | 3.6 |

| 1a | 0.14 | 0.85 | 4.5 | 1.3 |

| 1b | 0.48 | 6.7 | 2.0 | 28 |

In summary, the enantioselective synthesis of two novel tricyclic DBO analogues was accomplished in 17 linear steps (1.8% and 0.6% overall yield, respectively). Compound 1b has demonstrated excellent aqueous stability at physiological pH, demonstrating the fundamental differences between ring strain and stability. Additionally, the biochemical data presented herein further illustrates the lack of direct correlation between reactivity and enzymatic activity for covalent inhibitors. Additional SAR exploration will be required to better understand the stability and improve the enzymatic activity of this exciting new class of β-lactamase inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nancy DeGrace for assistance with the NMR experiments, Lise Gauthier for the RP-HPLC purification, Ying Liu for the HRMS studies, and Tiffany Palmer for generating the β-lactamase inhibition data.

Supporting Information Available

Representative assay protocols, experimental procedures, and spectroscopic data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): The authors are all current or former employees of AstraZeneca and may possess AstraZeneca stock.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ambler R. P. The structure of β-lactamases. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London, Ser. B 1980, 289, 321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall B. G.; Barlow M. J. Revised Ambler classification of β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005, 55, 1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K.; Jacoby G. A. Updated functional classification of β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drawz S. M.; Bonomo R. A. Three decades of β-lactamase inhibitors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 160.and references therein.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebrone A.; Lassaux P.; Vercheval L.; Sohier J.-S.; Jehaes A.; Sauvage E.; Galleni M. Current challenges in antimicrobial chemotherapy: focus on ß-lactamase inhibition. Drugs 2010, 70, 651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K.; Macielag M. J. New β-lactam antibiotics and β-lactamase inhibitors. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2010, 20, 1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://www.lahey.org/studies/.

- Stachyra T.; Pechereau M. C.; Bruneau J. M.; Claudon M.; Frère J. M.; Miossec C.; Coleman K.; Black M. T. Mechanistic studies of the inactivation of TEM-1 and P99 by NXL104, a novel non-β-lactam β-lactamase inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 5132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livermore D. M.; Mushtaq S.; Warner M.; Zhang J.; Maharjan S.; Doumith M.; Woodford N. Activity of NXL104 in combination with β-lactams against genetically characterized Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates producing class A extended-spectrum β-lactamases and class C β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman K. Diazabicyclooctanes (DBOs): a potent new class of non-β-lactam β-lactamase inhibitors. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011, 14, 550.and references therein.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnefoy A.; Dupuis-Hamelin C.; Steier V.; Delachaume C.; Seys C.; Stachyra T.; Fairley M.; Guitton M.; Lampilas M. In vitro activity of AVE1330A, an innovative broad-spectrum non-β-lactam β-lactamase inhibitor. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 54, 410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J. A.; Cherryman J. H.; Golden M.; Kalyan Y. B.; Lawton G. R.; Milne D.; Phillips A. J.; Racha S.; Ronsheim M. S.; Telford A.. Process for preparing heterocyclic compounds including trans-7-oxo-6-(sulphooxy)-1,6-diazabicyclo[3,2,1]octane-2-carboxamide and salts thereof. Patent WO2012172368, 2012.

- Ehmann D. E.; Jahic H.; Ross P. L.; Gu R. F.; Hu J.; Kern G.; Walkup G. K.; Fisher S. L. Avibactam is a covalent, reversible, non-β-lactam β-lactamase inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 11663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangion I. K.; Ruck R. T.; Rivera N.; Huffman M. A.; Shevlin M. A concise synthesis of a β-lactamase inhibitor. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 5480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. P.; Zhong Y.-L.; Liu Z.; Simeone M.; Yasuda N.; Limanto J.; Chen Z.; Lynch J.; Capodanno V. Practical and cost-effective manufacturing route for the synthesis of a β-lactamase inhibitor. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blizzard T. A.; Chen H.; Kim S.; Wu J.; Bodner R.; Gude C.; Imbriglio J.; Young K.; Park Y.-W.; Ogawa A.; Raghoobar S.; Hairston N.; Painter R. E.; Wisniewski D.; Fitzgerald P.; Sharma N.; Lu J.; Ha S.; Hermes J.; Hammond M. L. Discovery of MK-7655, a β-lactamase inhibitor for combination with Primaxin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trost B. M.; Horne D. B.; Woltering M. J. Palladium-catalyzed DYKAT of vinyl epoxides: enantioselective total synthesis and assignment of the configuration of (+)-Broussonetine G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 5987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber S. B.; Kingsbury J. S.; Gray B. L.; Hoveyda A. H. Efficient and recyclable monomeric and dendritic Ru-based metathesis catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 8168. [Google Scholar]

- Gemal A. L.; Luche J. L. Lanthanoids in organic synthesis. 6. Reduction of alpha-enones by sodium borohydride in the presence of lanthanoid chlorides: synthetic and mechanistic aspects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 5454. [Google Scholar]

- Denmark S. E.; Edwards J. P. A comparison of (chloromethyl)- and (iodomethyl)zinc cyclopropanation reagents. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 6974. [Google Scholar]

- Grieco P. A.; Hon Y. S.; Perez-Medrano A. Convergent, enantiospecific total synthesis of the novel cyclodepsipeptide (+)-jasplakinolide (jaspamide). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 1630. [Google Scholar]

- Nigam S. C.; Mann A.; Taddei M.; Wermuth C.-G. Selective removal of the tert-butoxycarbonyl group from secondary amines: ZnBr2 as the deprotecting reagent. Synth. Commun. 1989, 19, 3139. [Google Scholar]

- Murray A. J.; Parsons P. J.; Hitchcock P. The combined use of stereoelectronic control and ring closing metathesis for the synthesis of (−)-8-epi-swainsonine. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 6485. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M.; Li J.; Song Z.; Desmond R.; Tschaen D. M.; Grabowski E. J. J.; Reider P. J. A novel chromium trioxide catalyzed oxidation of primary alcohols to the carboxylic acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 5323. [Google Scholar]

- Corey E. J.; Chakovsky M. Dimethyloxosulfonium methylide ((CH3)2SOCH2) and dimethylsulfonium methylide ((CH3)2SCH2). Formation and application to organic synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 1353. [Google Scholar]

- Gololobov Y. G.; Nesmeyanov A. N.; lysenko V. P.; Boldeskul I. E. Twenty-five years of dimethylsulfoxonium ethylide (Corey’s reagent). Tetrahedron 1987, 43, 2609. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes N. O.; Macdonald S. J. F.; Page M. I. Acylating agents as enzyme inhibitors and understanding their reactivity for drug design. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J.; Petter R. C.; Baillie T. A.; Whitty A. The resurgence of covalent drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2011, 10, 307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.