Abstract

Background

Peer victimization is ubiquitous across schools and cultures, and has been suggested as one developmental pathway to anxiety disorders. However, there is a dearth of prospective studies examining this relationship. The purpose of this cohort study was to examine the association between peer victimization during adolescence and subsequent anxiety diagnoses in adulthood. A secondary aim was to investigate whether victimization increases risk for severe anxiety presentations involving diagnostic comorbidity.

Methods

The sample comprised 6,208 adolescents from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children who were interviewed about experiences of peer victimization at age 13. Maternal report of her child's victimization was also assessed. Anxiety disorders at age 18 were assessed with the Clinical Interview Schedule–Revised. Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the association between victimization and anxiety diagnoses adjusted for potentially confounding individual and family factors. Sensitivity analyses explored whether the association was independent of diagnostic comorbidity with depression.

Results

Frequently victimized adolescents were two to three times more likely to develop an anxiety disorder than nonvictimized adolescents (OR = 2.49, 95% CI: 1.62–3.85). The association remained after adjustment for potentially confounding individual and family factors, and was not attributable to diagnostic overlap with depression. Frequently victimized adolescents were also more likely to develop multiple internalizing diagnoses in adulthood.

Conclusions

Victimized adolescents are at increased risk of anxiety disorders in later life. Interventions to reduce peer victimization and provide support for victims may be an effective strategy for reducing the burden associated with these disorders.

Keywords: anxiety, peer victimization, bullying, adolescence, ALSPAC, longitudinal, comorbidity

Introduction

Anxiety disorders are among the most prevalent psychiatric disorders. In 2011, an estimated 69.1 million people in Europe were affected by anxiety disorders, more than those affected by depression and alcohol dependence combined.1 With a relatively early age of onset, and typically chronic course, anxiety disorders account for a large proportion of the burden of disease in Western countries.2,3 Early preventative interventions have the potential to greatly reduce the burden of these disorders at the societal level and alleviate suffering at the individual level. Thus, research has increasingly attempted to detect early markers or risk factors for the development of anxiety disorders.

Peer victimization is one potentially modifiable risk factor linked to the development of psychological disorders. The term peer victimization is a broad label encompassing multiple aspects of intentional harm doing including physical (e.g., hitting), verbal (e.g., name calling), and relational means (e.g., rejection, ostracism). Research suggests that peer victimization is ubiquitous across schools, cultures, and countries, with an estimated 10–30% of children reporting experiences of being bullied.4–6 Cross-sectional studies have consistently linked peer victimization to psychological problems, including symptoms of anxiety (see7); however the direction of causality is difficult to establish, as anxious children may be at greater risk of being targeted by bullies.8 Prospective data are needed to clarify whether anxiety symptoms precede or are a consequence of peer victimization.

Few prospective studies have specifically examined the relationship between peer victimization and anxiety. There is some evidence linking peer victimization during adolescence with elevated symptoms of social anxiety up to 12 months later.9,10 Only two studies have examined the relationship between peer victimization and adult anxiety disorders. The first study within a sample of 2,540 boys in Finland revealed that frequent victimization at age 8 was associated with a threefold increase in the risk of an anxiety diagnosis 10 to 15 years later.11 The second comprehensively examined psychiatric outcomes for a sample of 1,420 participants in the United States.12 Controlling for childhood psychiatric disorders and family hardships, victimization between the ages of 9 and 16 was associated with elevated rates of agoraphobia, generalized anxiety, and panic disorder in adulthood.

In this study, we used data collected from a large U.K. cohort to examine the association between peer victimization during adolescence and anxiety diagnosis at age 18. Our study builds on the existing literature in several ways. First, we focus on the impact of peer victimization occurring during early adolescence (age 13). This age marks the beginning of an elevated risk period for anxiety disorders,13 as well as a time during which peer relationships and approval become increasingly important.14 Second, our study examines the specific relationship between adolescent peer victimization and adulthood anxiety disorders while taking into account the high comorbidity that is typical between anxiety and depressive disorders.15 Peer victimization has been linked to the development of depression symptoms and diagnosis in a number of studies (including two using data from this same cohort16–19), and yet no previous study has examined whether the association between victimization and anxiety is independent of diagnostic comorbidity with depression. Third, the wealth of background information available for this cohort means that we are able to adjust for a comprehensive range of potentially confounding variables including concurrent victimization of others (e.g., bully perpetration), socioeconomic variables, parental anxiety and depression, child maltreatment, and preadolescent levels of anxiety and depression.

We specified a number of hypotheses a priori based on previous research. Our primary hypothesis was that peer victimization during early adolescence would be associated with anxiety disorders in adulthood, adjusting for potential confounders. Moreover, we hypothesized that this relationship would be independent of the diagnostic comorbidity between anxiety and depression. Finally, we hypothesized that peer victimization would place adolescents at risk for the development of complex presentations involving diagnostic comorbidity.

Method

Participants

The sample comprised participants from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), an ongoing population-based study. The study website contains details of all data that are available through a searchable data dictionary (http://www.bris.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/data-access/data-dictionary). Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ALSPAC Ethics and Law Committee and the Local Research Ethics Committees. In total, 15,247 pregnant mothers residing in the former Avon Health Authority in the southwest of England with expected dates of delivery between April 1, 1991 and December 31, 1992 were recruited to the study. These pregnancies resulted in 14,775 live births, of which 14,701 were alive at 1 year of age. See20 for further details on the cohort profile, representativeness, and phases of recruitment.

In this study, we used data from the subsample of Phase I ALSPAC singleton offspring (n = 13,617) who attended the age 13 research clinic and provided valid peer victimization data (n = 6,208). Of these, 3,629 participants (58.5%) completed the Clinical Interview Schedule–Revised (CIS-R) at 18 years. Complete data for the exposure, outcome, and all covariates were available for 2,363 participants (response attrition was examined using multiply imputed data).

Measures

Peer Victimization

A modified version of the Bullying and Friendship Interview Schedule21 was administered during the age 13 clinic to assess self-reported peer victimization. Frequency of peer victimization and perpetration (i.e., bullying others) was rated on a 4-point scale (0 = never, 1 = seldom, 2 = frequently, 3 = very frequently) across five different types of overt victimization (theft, threats or blackmail, physical violence, nasty names, nasty tricks), and four types of relational victimization (social exclusion, spreading lies or rumors, coercive behavior, deliberately spoiling games). Total scores were calculated separately for victimization and perpetration from the sum of frequency scores for all items (see16). The range of scores was 0–25 for victimization (mean = 1.85, SD = 2.78), and 0–21 for perpetration (mean = 0.75, SD = 1.62). The victimization score was of principal interest for this study; a three-level ordinal variable was derived from this score in order to investigate a possible dose–response pattern. Adolescents scoring 0 were classified never victimized (n = 2,845), those scoring 1–3 were classified occasionally victimized (n = 2,247), and those who scored 4 or more were classified frequently victimized (n = 1,116).

Maternal report of peer victimization was also assessed when adolescents were 13 years old. Mothers rated on a 3-point scale the extent her child was “picked on or bullied by other children.” Due to small cell count in the highest category, data were collapsed to form a binary variable indicating not true or somewhat/certainly true.

Anxiety Disorders

Participants completed a self-administered computerized version of the CIS-R (22) at the age 18 research clinic. This interview assesses symptoms across multiple domains, and computer algorithms are used to identify current psychiatric disorders according to ICD-10 diagnostic criteria. This computerized version demonstrates good agreement with interviewer assessment.22 The primary outcome for this study was a binary variable indicating presence versus absence of any of the following five anxiety disorders: generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific (isolated) phobia, panic disorder, or agoraphobia. Diagnoses of depression were also identified using the CIS-R, and we derived a three-category variable to indicate the presence of diagnostic comorbidity: participants were classified as having no anxiety diagnosis, single anxiety diagnosis, or comorbid diagnoses. The comorbid category included participants with multiple anxiety diagnoses and/or comorbid anxiety and depression diagnoses.

Potential Confounders

Analyses were adjusted for the following sociodemographic and family factors (assessed by maternal report during pregnancy unless otherwise stated) that have been previously associated with victimization and anxiety: (i) major financial problems (yes/no) and home ownership (yes/no); (ii) maternal education (ordinal-level secondary school qualification and below versus advanced-level or above); (iii) parental social class ranked from high to low at five intervals using standard occupational classification23; (iv) domestic violence (yes/no) defined as any maternal report of partner cruelty (emotional or physical) or violence assessed yearly up until child age 3 (see24); (v) child maltreatment (yes/no) defined as any maternal report of the child being sexually abused, physically hurt, or taken into care assessed yearly until child age 9; (vi) a parental hostility score derived from the sum of six items assessing hitting (smacking or slapping the child) or hostility (e.g., irritated by the child) up until child age 4 (see25); (vii) maternal and paternal self-reported anxiety (Crown–Crisp Experiential Index anxiety subscale26) and depression (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale27) derived from mean scores across three assessments (antenatal, child age 8 weeks and 8 months); and (viii) child's preexisting anxiety and depression symptoms at age 10 as assessed by the five items of the Strengths and Difficulties questionnaire Emotional symptoms subscale (maternal report28).

Data Scoring and Analysis

All analyses were conducted using STATA 12.0. Missing responses on multi-item scales were imputed using mean substitution provided valid items were present for at least 80% of items.29 Due to small cell count for specific anxiety disorders, the primary outcome was a binary variable indicating diagnosis of any anxiety disorder. A series of logistic regressions examined associations between victimization at age 13 and any anxiety disorder at age 18, adjusted for potentially confounding variables (individual and family factors). We then used multinomial logistic regression to examine the association between victimization and single versus comorbid anxiety diagnoses. Sensitivity analyses examined the robustness of the principal analysis (i) within a subgroup excluding participants with diagnosed depression at age 18 (n = 277), and (ii) using mother-reported victimization status.

Missing Data

Participants with complete data came from more socially advantaged families with fewer mental health symptoms as compared to the rest of the ALSPAC sample (see Supporting Information Table S2). However, partial responding was not associated with victimization reports at age 13. Complete-case analyses can be biased if data are not missing completely at random, thus we imputed 100 datasets, each entailing 20 cycles of regression switching, using multiple imputation by chained equations.30 This is a recommended procedure for missing data,31 and assumes data are missing at random (MAR) conditional on the variables in the imputation model. To ensure plausibility of the MAR assumption, our imputation model included a number of auxiliary sociodemographic and mental health variables predictive of incomplete variables and/or missingness (full list available on request). Estimates were combined according to Rubin's rules using the Stata mim command.32

Results

Descriptive Data

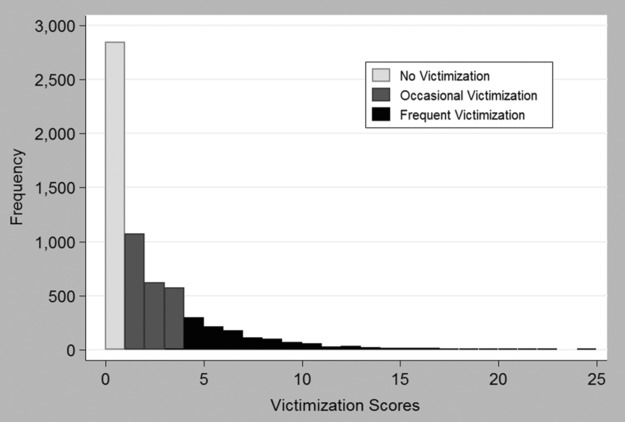

Peer victimization was reported by 3,363 adolescents (54% of the total sample); of these 1,116 adolescents were classified as frequently victimized. Figure1 illustrates the composition of the three victimization groups according to raw victimization scores on the Bullying and Friendship Interview Schedule. Table1 displays descriptive characteristics for the sample by victimization status. Victimized adolescents were more likely to be female, and had more severe emotional symptoms at age 10. Peer victimization was also associated with the following family characteristics: financial problems, higher maternal education, domestic violence, child maltreatment, parental hostility, and maternal and paternal symptoms of anxiety and depression. Victimized adolescents also had higher perpetration scores; with frequently victimized adolescents most likely to bully others.

Figure 1.

Histogram illustrating composition of the three victimization groups (never, occasionally, and frequently victimized) according to raw victimization scores on the Bullying and Friendship Interview Schedule.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the sample according to self-reported victimization at age 13

| No victimization | Occasional victimization | Frequent victimization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 2,845) | (n = 2,247) | (n = 1,116) | Difference testa | ||||

| Female | 1,392 | (48.9%) | 1,181 | (52.6%) | 582 | (52.5%) | P = .018 |

| Financial problems | 409 | (14.6%) | 378 | (17.0%) | 216 | (19.6%) | P < .001 |

| Parental homeownership | 2,316 | (83.8%) | 1,832 | (84.0%) | 891 | (82.4%) | P = .486 |

| Parental social class | |||||||

| I Professional | 400 | (16.0%) | 334 | (16.6%) | 171 | (17.2%) | P = .825 |

| II Managerial/technical | 1,134 | (45.3%) | 934 | (46.5%) | 454 | (45.7%) | |

| III Skilled non-manual | 634 | (25.3%) | 466 | (23.2%) | 239 | (24.1%) | |

| IV Skilled manual | 251 | (10.0%) | 197 | (9.8%) | 96 | (9.7%) | |

| IV & V: Partly skilled/unskilled | 84 | (3.4%) | 78 | (3.9%) | 33 | (3.3%) | |

| Maternal education (A-levels or above) | 1,128 | (42.8%) | 978 | (46.3%) | 492 | (47.0%) | P = .017 |

| Child maltreatment | 337 | (12.9%) | 302 | (14.7%) | 189 | (18.5%) | P < .001 |

| Domestic violence | 522 | (21.8%) | 480 | (25.4%) | 283 | (30.0%) | P < .001 |

| Continuous measures | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Victimization (age 13) | 0 | n/a | 1.8 | (0.8) | 6.7 | (3.0) | P < .001 |

| Perpetration (age 13) | 0.2 | (0.8) | 0.8 | (1.5) | 2.1 | (2.5) | P < .001 |

| Emotional symptoms (age 10) | 1.4 | (1.6) | 1.5 | (1.7) | 1.7 | (1.8) | P < .001 |

| Maternal anxiety | 3.7 | (2.8) | 4.0 | (2.9) | 4.2 | (2.9) | P < .001 |

| Maternal depression | 5.6 | (3.9) | 6.1 | (4.1) | 6.2 | (4.2) | P < .001 |

| Paternal anxiety | 2.5 | (2.3) | 2.7 | (2.4) | 2.9 | (2.4) | P < .001 |

| Paternal depression | 3.7 | (3.4) | 3.8 | (3.4) | 4.1 | (3.3) | P < .001 |

| Parental hostility | 1.7 | (1.5) | 1.8 | (1.5) | 2.1 | (1.6) | P < .001 |

Differences in sample characteristics according to victimization status at age 13 were examined using chi-square tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables.

Association Between Peer Victimization and Anxiety Disorders in Adulthood

One or more anxiety diagnoses were present for 350 of those 3,629 who completed the CIS-R at 18 years. Table2 shows the frequency of diagnosis by disorder type and extent of diagnostic comorbidity. Among those adolescents who reported frequent victimization at age 13, 15% went on to develop an anxiety disorder, as compared to 11% of adolescents who reported some victimization, and 6% of adolescents who were not victimized.

Table 2.

Incidence of anxiety disorder subtypes and comorbidity at age 18 by self-reported victimization status at age 13

| Total sample | No victimization | Occasional victimization | Frequent victimization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 3,629) |

(n = 1,638) |

(n = 1,345) |

(n = 646) |

|||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | s | % | |

| Anxiety disorders | ||||||||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 199 | (5.5%) | 60 | (3.7%) | 78 | (5.8%) | 61 | (9.4%) |

| Social phobia | 69 | (1.9%) | 22 | (1.3%) | 20 | (1.5%) | 27 | (4.2%) |

| Specific phobia | 126 | (3.5%) | 26 | (1.6%) | 65 | (4.8%) | 35 | (5.4%) |

| Panic disorder | 25 | (0.7%) | 8 | (0.5%) | 9 | (0.7%) | 8 | (1.2%) |

| Agoraphobia | 16 | (0.4%) | 3 | (0.2%) | 8 | (0.6%) | 5 | (0.8%) |

| Any anxiety disorder | 350 | (9.6%) | 99 | (6.0%) | 152 | (11.3%) | 99 | (15.3%) |

| Depression | ||||||||

| Any depression diagnosis | 277 | (7.6%) | 87 | (5.3%) | 96 | (7.1%) | 94 | (14.6%) |

| Comorbidity | ||||||||

| Comorbid anxiety & depression diagnoses | 120 | (3.3%) | 31 | (1.9%) | 46 | (3.4%) | 43 | (6.7%) |

| Multiple anxiety disorder diagnoses | 76 | (2.1%) | 17 | (1.0%) | 26 | (1.9%) | 33 | (5.1%) |

| Any co-morbid disordera (depression or anxiety) | 159 | (4.4%) | 40 | (2.4%) | 60 | (4.5%) | 59 | (9.1%) |

This row indicates participants with an anxiety disorder who were diagnosed with an additional anxiety and/or depression diagnosis.

Although victimization was more common in females, there was no evidence for an interaction between sex and peer victimization (χ2(2) = 2.74, P = .254), and thus analyses were not stratified by sex but conducted within the total sample. There was evidence of a linear relationship between peer victimization and risk for adult anxiety (see Table3). A dose–response pattern was evident: compared with nonvictimized peers, adolescents who reported occasional victimization were two times as likely to be diagnosed with anxiety at 18 (OR: 1.98, 95% CI: 1.52–2.58), and frequent victimization was associated with a threefold increase in the likelihood of an anxiety diagnosis (OR: 2.81, 95% CI: 2.09–3.78). Adjustment for sociodemographic and family characteristics made very little difference to these associations. The greatest reduction in effect size was observed after adjustment for individual characteristics (gender, perpetration score, and anxiety and depression symptoms at age 10). Within the full multivariate model, adjusted odds ratios associated with occasional and frequent victimization were 1.79 (95% CI: 1.27–2.54) and 2.49 (95% CI: 1.62–3.85), respectively.

Table 3.

Association between self-reported peer victimization at age 13 and any anxiety disorder at age 18

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted 1a |

Adjusted 2b |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Full sample | (n = 3,629) | (n = 3,222) | (n = 2,363) | ||||||

| No victimization | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Occasional victimization | 1.98 | (1.52–2.58) | <.001 | 1.86 | (1.39–2.49) | <.001 | 1.79 | (1.27–2.54) | .001 |

| Frequent victimization | 2.81 | (2.09–3.78) | <.001 | 2.52 | (1.75–3.63) | <.001 | 2.49 | (1.62–3.85) | <.001 |

| Linear trend | 1.12 | (1.09–1.16) | <.001 | 1.12 | (1.07–1.17) | <.001 | 1.11 | (1.05–1.17) | <.001 |

| Subsample excluding diagnosed depressionc | (n = 3,352) | (n = 2,986) | (n = 2,195) | ||||||

| No victimization | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Occasional victimization | 2.02 | (1.48–2.77) | <.001 | 2.05 | (1.45–2.91) | <.001 | 2.00 | (1.32–3.04) | .001 |

| Frequent victimization | 2.46 | (1.70–3.56) | <.001 | 2.50 | (1.59–3.93) | <.001 | 2.72 | (1.59–4.63) | <.001 |

| Linear trend | 1.11 | (1.06–1.15) | <.001 | 1.12 | (1.06–1.18) | <.001 | 1.12 | (1.05–1.20) | .001 |

Adjusted 1: Adjusted for child's individual characteristics: gender, perpetration score at age 13, anxiety and depression symptom score at age 10.

Adjusted 2: Additionally adjusted for family characteristics: financial problems, home ownership, parental social class, maternal education, child maltreatment, parental hostility, domestic violence, maternal and paternal symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Sensitivity analyses examined the robustness of the principal analysis within a subgroup that excluded participants with a diagnosis of depression at age 18 (n = 277).

Subgroup analyses examined the robustness of the results when participants who met diagnostic criteria for depression at age 18 were excluded from the analysis (see Table3). A similar pattern of results was observed: within the fully adjusted model frequently victimized adolescents were 2.72 (95% CI: 1.59–4.63) times at risk of adult anxiety compared to nonvictimized peers.

A consistent pattern of results was also observed when maternal report of her child's victimization was examined (see Table4). Mother-reported victimization at age 13 was associated with increased risk of adulthood anxiety (OR: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.18–2.04, P = .002); however the size of effect was smaller than models examining adolescent report. Adjustment for family characteristics further reduced the effect size (OR: 1.46, 95% CI: 1.02–2.09, P = .040).

Table 4.

Association between adolescent mother-reported peer victimization at age 13 and any anxiety disorder at age 18

| Exposed | Outcome | Unadjusted (n = 3,308) |

Adjusted 1a (n = 3,067) |

Adjusted 2b (n = 2,287) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (all available data) | % | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Mother-reported victimization | |||||||||||

| No | 3,002 | 8.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 306 | 12.6 | 1.55 | (1.18–2.04) | .002 | 1.58 | (1.17–2.12) | .003 | 1.46 | (1.02–2.09) | .040 |

Adjusted 1: Adjusted for child's individual characteristics: gender, and anxiety and depression symptom score at age 10.

Adjusted 2: Additionally adjusted for family characteristics: financial problems, home ownership, parental social class, maternal education, child maltreatment, parental hostility, domestic violence, maternal and paternal symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Association Between Peer Victimization and Diagnostic Comorbidity

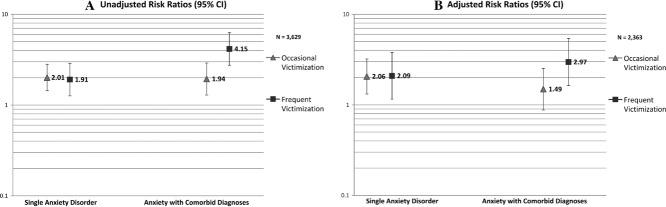

Adolescents who reported frequent victimization were at greater risk of diagnostic comorbidity compared with those who were not victimized (OR: 4.15, 95% CI: 2.74–6.27, P < .001). The size of these associations was reduced after controlling for potential confounders (see Fig.2). Within the fully adjusted model, frequent victimization was associated with almost a threefold increased risk of having multiple anxiety diagnoses and/or comorbid anxiety and depression in adulthood (OR: 2.97, 95% CI: 1.63–5.41, P < .001). Adolescents who reported occasional victimization were more likely than nonvictimized peers to develop a single anxiety disorder (OR: 2.06, 95% CI: 1.32–3.21, P = .002), but adjusted estimates did not indicate increased risk for comorbid presentations (OR: 1.49, 95% CI: 0.88–2.53, P = .142).

Figure 2.

Association between self-reported peer victimization at age 13 and anxiety disorders with and without diagnostic comorbidity at age 18. (A) Unadjusted multinomial regression results. (B) Adjusted for child's individual characteristics: gender, and anxiety and depression symptom score at age 10, and family characteristics: financial problems, home ownership, parental social class, maternal education, child maltreatment, parental hostility, domestic violence, maternal and paternal symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Missing Data

The principal analyses were repeated using datasets imputed through two different procedures: (i) imputation of missing covariate data in the sample of 3,629 with complete outcome data; (ii) imputation of missing covariate and outcome data for the entire starting sample of 6,208 adolescents (see Supporting Information Table S2). Analyses with imputed data confirmed our findings; there was no material difference to the pattern of results derived from either imputation procedure compared to complete-case analyses.

Discussion

Peer victimization at age 13 was associated with increased risk of anxiety disorders in early adulthood. A dose–response relationship was evident, with the risk of an anxiety diagnosis at age 18 increasing as the frequency of victimization increased. The associations persisted after controlling for a range of individual, sociodemographic, and family factors including parental anxiety and depression, domestic violence, child maltreatment, concurrent bully perpetration, and pre-existing anxiety and depression symptoms at age 10. Within the fully adjusted model, frequently victimized adolescents were two to three times more likely to develop an anxiety disorder compared with those who were not victimized. We found no evidence to suggest the impact of victimization was moderated by gender. The relationship between victimization and anxiety was also apparent when maternal report was examined, although using this single question resulted in lower estimates of the association that could be attributable to random misclassification.

Our findings are consistent with the growing number of longitudinal studies suggesting a relationship between peer victimization and anxiety.9–12 This study extends the existing evidence by showing this association was not attributable to diagnostic overlap between anxiety and depression, as results were replicated in subgroup analyses excluding participants with diagnosed depression. Furthermore, our study shows that frequent victimization is a risk factor for complex presentations involving diagnostic comorbidity. After adjustment for confounders, frequently victimized adolescents were three times more likely than nonvictimized adolescents to be diagnosed with multiple anxiety disorders or comorbid anxiety and depression in early adulthood.

When interpreting the association between victimization and anxiety, it is important to consider the possibility of reverse causation, since anxious children may be more prone to victimization by their peers.8 However, for three reasons this explanation is unlikely to account for the current pattern of results. First, the longitudinal design of this study and length of the follow-up period from age 13 to age 18 provide support for the hypothesis that peer victimization may be causally related to anxiety disorders. Second, we found evidence to suggest this relationship is independent of inherited risk for anxiety, as the association between victimization and anxiety disorders was unaffected by adjustment for maternal and paternal symptoms of anxiety and depression. This is consistent with a previous report that victimized monozygotic twins had more internalizing problems at follow-up compared to nonvictimized co-twins, suggesting that peer victimization is a potent environmental risk factor.33 Third, the association remained after adjustment for severity of prior anxiety and depression symptoms (assessed at age 10), which together with additional individual factors (gender and perpetration score) resulted in only a slight reduction compared to the unadjusted odds ratio.

To date, the mechanisms that underlie the association between peer victimization and anxiety disorders are not well understood. From a contemporary fear learning perspective, victimization experiences may lead to a conditioned fear response to social and other stimuli associated with the victimization context (see34). These early learning experiences in combination with individual vulnerabilities (such as low coping self-efficacy) are thought to contribute to a heightened expectation of threat and danger.35,36 Preliminary evidence from cross-sectional data supports the mediating role of coping self-efficacy,37 and threat appraisal38 in the relationship between peer victimization and anxiety disorders. However, the cross-sectional nature of these studies limits the conclusions that can be drawn, and prospective investigations are needed to clarify the mechanisms underlying this association.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include the large sample size, and extended follow-up period from assessment of victimization in early adolescence to assessment of clinical outcomes in adulthood. Our assessment of victimization involved a detailed interview with adolescents that probed for episodes of peer victimization across a range of different situations. Prior research suggests self-report is the most sensitive and reliable method for assessing victimization16,39; however this method is limited by its subjective nature and may be affected by response bias. Thus we supplemented our assessment of victimization with information obtained from mothers in order to corroborate findings based on adolescent report. Furthermore, we adjusted for a comprehensive range of potentially confounding sociodemographic and family factors. Finally, to our knowledge this study is the first to examine whether the relationship between peer victimization and anxiety disorders exists independently of diagnostic comorbidity with depression.

We also note some potential limitations. First, response attrition in longitudinal studies can result in biased or underestimated associations. Adolescents who attended the research clinics came from more socially advantaged families with fewer mental health symptoms compared to those lost to followup. Thus, our study may underestimate the prevalence of peer victimization and/or anxiety disorders, which are associated with social disadvantage.40,41 Nonetheless, response attrition is unlikely to affect our conclusions as victimized adolescents were no more or less likely to provide anxiety outcome data, and analyses using imputed data revealed a pattern of results consistent with the complete-case analyses. Furthermore, empirical simulations demonstrate that even when dropout is associated with predictor/confounder variables, the relationship between predictors and outcome is unlikely to be substantially altered by selective dropout processes.42 Second, we were unable to examine associations between victimization and specific anxiety subdiagnoses due to small cell numbers. Nonetheless, our analysis suggested victimization as a general risk factor for anxiety disorders, and showed that frequently victimized adolescents are at increased risk of multiple internalizing diagnoses.

Conclusion

Adolescence is a period of elevated risk for the onset of anxiety disorders,13 and thus a key period for understanding the developmental origins of these disorders. Taken together with previous work, the current findings indicate that peer victimization is one potentially modifiable risk factor for the development of anxiety disorders. Moreover, our study suggests that frequent victimization in particular increases risk for the development of multiple psychiatric diagnoses. Anxiety disorders are associated with considerable functional impairment and reduced quality of life; this is especially true for comorbid presentations that are characterized by more severe impairment and poorer response to treatment.43,44 Policies designed to reduce the incidence or impact of victimization during adolescence may produce tangible benefits in the long term by reducing the burden associated with these disorders. It is important that health professionals and educators are aware of the potential psychological impact of peer victimization and equipped to provide information and support as needed.

These findings also suggest a number of important directions for future research. First, it will be important to identify the psychological mechanisms that underlie the relationship between victimization and development of anxiety disorders. Second, there is considerable heterogeneity in outcomes for victimized adolescents, and not all develop psychological disorders in adulthood. Therefore, it will be useful to identify individual or environmental characteristics that may help to minimize the psychological impact on victims. For example, there is some evidence that adolescents with protective family factors (maternal warmth, sibling warmth, and a positive atmosphere at home) are less susceptible to the adverse psychological effects of victimization.45 Finally, little is known about the potential benefits of anti-bullying interventions in terms of mental health outcomes. Over the past decade, evidence has accrued to suggest that school-based interventions can effectively reduce the incidence of peer victimization (for a review, see46,47). However, it is not yet known whether universal anti-bullying interventions are sufficient to improve mental health outcomes, or whether targeted interventions to identify and support victims within school or primary health care settings would be a more effective measure. This is a promising area for future research given the potential public health benefits.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted at the School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol. We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists, and nurses. The UK Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust, and University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. This publication is the work of the authors, who will serve as guarantors for the contents of this paper. This research was specifically funded by a Wellcome Trust grant held by Prof. Lewis.

References

- Wittchen H-U, Jacobi F, Rehm J. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21(9):655–679. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H-U, Jacobi F. Size and burden of mental disorders in Europe—a critical review and appraisal of 27 studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15(4):357–376. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers CD, Vos ET, Stevenson CE, Begg SJ. The burden of disease and injury in Australia. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79(11):1076–1084. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig W, Harel-Fisch Y, Fogel-Grinvald H. A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. Int J Public Health. 2009;54(0):216–224. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-5413-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Analitis F, Velderman MK, Ravens-Sieberer U. Being bullied: associated factors in children and adolescents 8 to 18 years old in 11 European countries. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):569–577. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nansel T, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan W, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among us youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond L, Carlin JB, Thomas L, Rubin K, Patton G. Does bullying cause emotional problems? A prospective study of young teenagers. BMJ. 2001;323(7311):480–484. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7311.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Dodge KA, Coie JD. The emergence of chronic peer vicitimization in boys’ play groups. Child Dev. 1993;64(6):1755–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb04211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RS, La Greca AM, Harrison HM. Peer victimization and social anxiety in adolescents: prospective and reciprocal relationships. J Youth Adolesc. 2009;38(8):1096–1109. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Masia-Warner C, Crisp H, Klein RG. Peer victimization and social anxiety in adolescence: a prospective study. Aggress Behav. 2005;31(5):437–452. [Google Scholar]

- Sourander A, Jensen P, Ronning JA. What is the early adulthood outcome of boys who bully or are bullied in childhood? The Finnish “From a Boy to a Man” study. Pediatrics. 2007;120(2):397–404. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Wolke D, Angold A, Costello EJ. Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(4):419–426. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Holt MK. Bullying and victimization during early adolescence. J Emotio Abuse. 2001;2(2–3):123–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowes L, Joinson C, Wolke D, Lewis G. Depression in early adulthood: the role of peer victimization during adolescence, a prospective cohort study. (in preparation)

- Zwierzynska K, Wolke D, Lereya T. Peer victimization in childhood and internalizing problems in adolescence: a prospective longitudinal study. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013;41(2):309–323. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9678-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeting H, Young R, West P, Der G. Peer victimization and depression in early-mid adolescence: a longitudinal study. Br J Educ Psychol. 2006;76(3):577–594. doi: 10.1348/000709905X49890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klomek AB, Sourander A, Kumpulainen K. Childhood bullying as a risk for later depression and suicidal ideation among Finnish males. J Affect Disord. 2008;109(1–2):47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.12.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd A, Golding J, Macleod J. Cohort profile: the ‘children of the 90s’—the index offspring of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(1):111–127. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolke D, Woods S, Stanford K, Schulz H. Bullying and victimization of primary school children in England and Germany: prevalence and school factors. Br J Psychol. 2001;92(4):673–696. doi: 10.1348/000712601162419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis G. Assessing psychiatric disorder with a human interviewer or a computer. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1994;48(2):207–210. doi: 10.1136/jech.48.2.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Population Censuses and Surveys. Standard Occupational Classification. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen E, Heron J, Waylen A, Wolke D. Domestic violence risk during and after pregnancy: findings from a British longitudinal study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;112(8):1083–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winsper C, Zanarini M, Wolke D. Prospective study of family adversity and maladaptive parenting in childhood and borderline personality disorder symptoms in a non-clinical population at 11 years. Psychol Med. 2012;42(11):2405–2420. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crown S, Crisp AH. Manual of the Crown-Crisp Experiental Index. London: Hodder & Stoughton; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Holden J, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A, Goodman R. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a dimensional measure of child mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(4):400–403. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181985068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrive FM, Stuart H, Quan H, Ghali WA. Dealing with missing data in a multi-question depression scale: a comparison of imputation methods. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: further update of ice, with an emphasis on categorical variables. Stata J. 2009;9(3):466–477. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royston P, Carlin JB, White IR. Multiple imputation of missing values: new features for mim. Stata J. 2009;9(2):252–264. [Google Scholar]

- Arseneault L, Milne BJ, Taylor A. Being bullied as an environmentally mediated contributing factor to children's internalizing problems: a study of twins discordant for victimization. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(2):145–150. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dygdon JA, Conger AJ, Strahan EY. Multimodal classical conditioning of fear: contributions of direct, observational, and verbal experiences to current fears. Psychol Rep. 2004;95(1):133–153. doi: 10.2466/pr0.95.1.133-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Unraveling the mysteries of anxiety and its disorders from the perspective of emotion theory. Am Psychol. 2000;55(11):1247–1263. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.11.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineka S, Oehlberg K. The relevance of recent developments in classical conditioning to understanding the etiology and maintenance of anxiety disorders. Acta Psychol (Amst) 2008;127(3):567–580. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P, Bussey K. Peer victimization and psychological maladjustment: the mediating role of coping self-efficacy. J Res Adolesc. 2011;21(2):420–433. [Google Scholar]

- Giannotta F, Settanni M, Kliewer W, Ciairano S. The role of threat appraisal in the relation between peer victimization and adjustment problems in early Italian adolescents. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2012;42(9):2077–2095. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini AD. Sampling instances of victimization in middle school: a methodological comparison. In: Juvonen J, Graham S, editors. Peer Harassment in School: The Plight of the Vulnerable and Victimized. New York: Guilford Press; 2001. pp. 125–144. In:, editors. [Google Scholar]

- Bowes L, Arseneault L, Maughan B, Taylor A, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. School, neighborhood, and family factors are associated with children's bullying involvement: a nationally representative longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(5):545–553. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819cb017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryers T, Melzer D, Jenkins R. Social inequalities and the common mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38(5):229–237. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolke D, Waylen A, Samara M. Selective drop-out in longitudinal studies and non-biased prediction of behaviour disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(3):249–256. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.053751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeijer-Sevink M Klein, Batelaan NM, van Megen HJ. Clinical relevance of comorbidity in anxiety disorders: a report from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) J Affect Disord. 2012;137(1–3):106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce SE, Yonkers KA, Otto MW. Influence of psychiatric comorbidity on recovery and recurrence in generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder: a 12-year prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1179–1187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowes L, Maughan B, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L. Families promote emotional and behavioural resilience to bullying: evidence of an environmental effect. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(7):809–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez Barbero JA, Ruiz Hernandez JA, Esteban BL, Garcia MP. Effectiveness of antibullying school programmes: a systematic review by evidence levels. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2012;34(9):1646–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Ttofi MM, Farrington DP, Lösel F, Loeber R. The predictive efficiency of school bullying versus later offending: a systematic/meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2011;21(2):80–89. doi: 10.1002/cbm.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.