Abstract

Objective

To estimate the prevalence of common mental disorders (CMDs) and examine the association of sleep disorders with presence of CMDs.

Methods

A self-administered questionnaire was used to ascertain demographic information and behavioral characteristics among 2,645 undergraduate students in Ethiopia. Standard questionnaires were used to assess CMDs, evening chronotype, sleep quality and daytime sleepiness.

Results

A total of 716 students (26.6%) were characterized as having CMDs. Female students had higher prevalence of CMDs (30.6%) compared to male students (25.4%). After adjusting for potential confounders, daytime sleepiness (OR=2.02; 95% CI 1.64-2.49) and poor sleep quality (OR=2.36; 95% CI 1.91-2.93) were associated with increased odds of CMDs.

Conclusion

There is a high prevalence of CMDs comorbid with sleep disorders among college students.

Keywords: sleep, mental disorders, college, Ethiopia, Africa

Sleep is an essential physiological function regulated by both circadian rhythms and sleep-wake homeostatic systems that determine duration and timing.1 Circadian rhythms —the physical, mental, and behavioral fluctuations during a 24-hour period—have been reported in recent studies to influence sleep quality and daytime sleepiness in adolescents.2 Circadian rhythms include individual preferences for morningness and eveningness (ME), a set of chronotypes indicating preference for physical and mental activities during a specific time of the day.3 A number of studies have demonstrated that evening types are more likely to experience circadian rhythm alterations, other sleep disorders, mood disturbances, suicidal behavior and substance use.4-6

People who experience irregular sleep patterns and poor sleep quality have reported increased levels of daytime sleepiness.7 College students are particularly susceptible to patterns of sleep disturbance and poor sleep quality due to increased physiologic changes, academic workload and psychosocial concerns.8, 9 Behavioral characteristics, such as alcoholic beverage consumption, substance use, and stimulant drink consumption have also been shown to increase the odds of excessive daytime sleepiness and various mental health disorders.10

An accumulating body of epidemiologic literature documents that mental health disorders among sub-Saharan Africans are the leading causes of morbidity and premature mortality.11 A recent survey conducted in Ethiopia showed a high prevalence of common mental disorders among adults.11 Furthermore, mental disorders were shown to account for 11% of the total burden of diseases in Ethiopia.12 Common mental disorders (CMDs), defined usually by depression, anxiety and somatoform disorders, are now recognized as important public health problems in low- and middle--income countries (LMICs). They particularly impact young adults; since the incidence of diagnosed mental health disorders tend to peak during early adulthood.13 Documented relationships between shortened sleep and excessive drowsiness, tension, and poor mood have been reported in university students and other young adult populations in several developed countries.14 Gau et al 15 in Taiwan reported that evening type individuals had higher frequencies of trouble sleeping, more frequent daytime napping, and greater tendencies for social withdrawal.15

Little is known about the relationship between sleep disorders and CMDs among young adults, particularly among sub-Saharan Africans. In the present study, therefore, we examined the extent to which biological chronotype, sleep quality, and daytime sleepiness are associated with presence of CMDs among Ethiopian college students. We expect that the findings of this study will provide a more thorough and comprehensive understanding of circadian rhythm preferences and sleep patterns as risk factors of mental health in LMICs.

Methods

Study Setting and Sample

A cross-sectional survey was conducted at the Universities of Gondar and Haramaya, Ethiopia. The study procedures have been described in detail elsewhere16. Briefly, a multistage sampling design by means of probability proportional to size (PPS) was used to select departments and all students from those departments were invited to participate. Students who expressed an interest in participating in the study were invited to meet in a large classroom or an auditorium where they were informed about the purpose of the study and asked to participate in the survey. There was no set time limit for completing the survey. Students who could not read the survey (i.e., were blind) were excluded, as were those students enrolled in correspondence, extension, or night school program. A total of 2,817 undergraduate students consented and participated in the study. For the study described here, after excluding participants with incomplete questionnaires on sleep disorders, the final analyzed sample consisted of 2,645 students. Based on the information provided, students excluded from analysis had similar characteristics as those considered for analysis.

Data Collection and Variables

A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect information for this study. The questionnaire ascertained demographic information including age, sex, and education level. Questions regarding behavioral risk factors such as caffeinated beverages, tobacco, alcohol, and Khat (Catha edulis Forsk) - psycho-stimulant substance grown in East Africa - consumption were also included. Participants' anthropometric measurements were taken by research nurses using standard protocols. Height and weight were measured without shoes or outerwear. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm and weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg. All anthropometric values consisted of the mean of three measurements.

General health questionnaire (GHQ-12)

The 12-item version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) was used to screen for non-pathological common mental disorders.17 The GHQ-12 has been commonly used worldwide, including sub-Saharan Africa 18 for studies of various clinical and non-clinical populations. The GHQ-12 asks respondents to report how they felt during last four weeks on a range of variables including problems with sleep and appetite, subjective experiences of stress, tension, or sadness, mastering of daily problems, decision making and self-esteem. Response choices included: less than usual, no more than usual, more than usual and much more than usual. Scoring was 0 for the first two choices and 1 for the next two. The maximum possible score was 12 with higher scores suggesting higher mental distress. In this study, CMDs was defined using previously established cut off points in other study populations. Those students who scored ≥5 on the GHQ-12 scale were considered as having CMDs.19,20

Morningness-eveningness questionnaire (MEQ)

Morningness/eveningness chronotype were assessed using the MEQ.21 The MEQ 21 is a 19-item questionnaire that identifies morningness-eveningness preference. The scores range from 16 to 86 and participants can be classified in five categories: definite and moderate E-type, neutral type, and moderate and definite M-type. Higher values on MEQ indicate stronger morningness preference. For this study we used the following cut offs: (1) 16 to 30 for evening; (2) 31 to 41 for moderate evening; (3) 42 to 58 for intermediate; (4) 59 to 69 for moderate morning, and (5) 70 to 86 for morning.

Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI)

Sleep quality was assessed using the previously validated Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).22 The PSQI has been validated among college students in sub-Saharan Africa.23 The PSQI is a 19-item self-reported questionnaire that evaluates sleep quality over the past month. It has seven sleep components including duration of sleep, sleep disturbance, sleep latency, habitual sleep efficiency, use of sleep medicine, daytime dysfunction, and overall sleep quality. Each sleep component yields a score ranging from 0 to 3, with three indicating the greatest dysfunction.22 The sleep component scores are summed to yield a total score ranging from 0 to 21 with higher total scores (referred to as global scores) indicating poor sleep quality. On the basis of prior studies,22 participants with a global score of >5 were classified as poor sleepers. Those students with a score ≤5 were classified as good sleepers.

Epworth sleep scale (ESS)

The ESS is a measure of individual's general level of daytime sleepiness 24. It is an 8-item questionnaire capturing an individual's propensity to fall asleep during commonly encountered situations on a scale from 0 to 3. The scores for the eight questions are added together to obtain a single total score ranging from 0 to 24. In adults, an ESS score ≥10 is taken to indicate increased daytime sleepiness.24 The ESS has been widely used globally among different study populations including college students in South East Asia and adults in sub-Saharan Africa.25, 26

Other Covariates

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height squared (m2). BMI thresholds were set according to the World Health Organization (WHO) protocol (underweight: <18.5 kg/m2; normal: 18.5–24.9 kg/m2; overweight: 25.0–29.9 kg/m2; obese ≥30 kg/m2).27 We defined alcohol consumption as none (<1 alcoholic beverage a week), moderate (1–19 alcoholic beverages a week), and high to excessive consumption (>19 alcoholic beverages a week).16, 28 The other covariates considered are: age (years), sex, smoking history (never versus ever), and regular participation in moderate or vigorous physical activity (no versus yes).

Statistical Analysis

We examined frequency distributions of demographic and lifestyle characteristics. Characteristics of those participants with and without CMDs were compared using Student's t tests, Wilcoxon's rank-sum tests, or Chi-square tests. Sex-specific prevalence of CMDs and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) across age groups were also estimated29. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to assess associations of sleep quality and daytime sleepiness (based on total PSQI and ESS scores, respectively) with total GHQ score. Logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (OR) 95% CI for the association of sleep disorders (evening chronotype, poor sleep quality and daytime sleepiness) with CMDs. The distribution of PSQI scores among students characterized as having CMDs and those students without CMDs was determined. All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistical Software (IBM SPSS Version 21, Chicago, IL, USA). All reported p-values are two-sided and deemed statistically significant at α=0.05.

Results

Nearly half (46.6%) of participants were age 22 or older, and more than three fourths (76.4%) were male students. Current smoking was reported by approximately 3% of participants while 14% of students reported consuming at least one alcoholic beverage per month. Approximately 9% of participants reported Khat usage. The majority of students (59.5%) were found to have a normal BMI (18.5-24.9) and 68.3% were physically active.

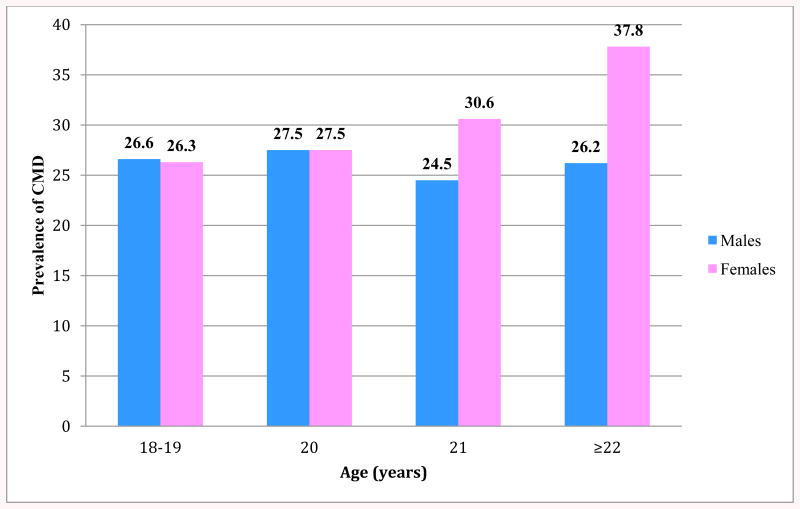

Behavioral and demographic characteristics of the study samples in relation to the presence of CMDs are reported in Table 1. Overall, of the 2,645 college students who completed the survey, a total of 716 (26.6%) students were characterized as having CMDs. Within the sample population, sex and alcohol consumption exhibited statistically significant associations with CMDs. Approximately 25% of male students were characterized as having CMDwhile 30.6% of female students had CMD (p value= 0.020). Those participants who consumed at least one alcoholic beverage per month (32.6%) had significantly higher prevalence of CMDs compared to those students who did not consume alcoholic beverages (26.1% p-value = 0.023). Other lifestyle and behavioral characteristics, such as cigarette smoking, Khat consumption, BMI, and physical activity, showed no statistically significant association with the presence of CMDs. The prevalence of CMDs grouped by age and sex is presented in Figure 1. Among female students, the prevalence of CMDs tended to increase with age, with 37.8% of female students aged 22 and older exhibiting characteristics of CMDs versus 26.2% of male students within the same age group.

Table 1. Common Mental Disorders by Demographic and Lifestyle Characteristics.

| All | Common Mental Disorders | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Yes (N=716) | No (N=1,929) | |||

| Age (years) | N=2,645 | n (%)* | n (%)* | |

|

|

||||

| 18-19 | 5.1 | 37 (26.8) | 101 (73.2) | 0.922 |

| 20 | 20.5 | 148 (27.2) | 397 (72.8) | |

| 21 | 27.6 | 191 (26.2) | 539 (73.8) | |

| ≥22 | 46.8 | 340 (27.6) | 892 (72.4) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 77.6 | 183 (30.7) | 413 (69.3) | 0.022 |

| Male | 22.4 | 521 (25.9) | 1,486 (74.0) | |

| Cigarette smoking status | ||||

| Never | 96.4 | 683 (24.8) | 1,865 (73.2) | 0.291 |

| Former | 0.5 | 5 (33.3) | 10 (66.7) | |

| Current | 3.1 | 28 (34.2) | 54 (65.8) | |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| <1 drink/month | 86.1 | 593 (26.1) | 1,676 (73.9) | 0.020 |

| 1-19 drinks/month | 12.6 | 114 (33.2) | 229 (66.8) | |

| ≥ 20 drinks/month | 1.3 | 9 (27.3) | 24 (72.7) | |

| Khat use | ||||

| No | 89.5 | 558 (27.0) | 1,507 (73.0) | 0.813 |

| Yes | 10.5 | 65 (26.3) | 182 (73.7) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)** | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 39.0 | 293 (38.6) | 733 (71.4) | 0.266 |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 59.6 | 411 (26.1) | 1,165 (73.9) | |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 1.4 | 7 (20.6) | 27 (79.4) | |

| Any physical activity | ||||

| No | 27.9 | 188 (26.9) | 510 (73.1) | 0.903 |

| Yes | 72.1 | 487 (27.2) | 1,305 (72.8) | |

Row percentages;

There were no obese (≥30 kg/m2) individuals in the study

Figure 1. Prevalence of CMDs According to Age and Sex.

As shown in Table 2, total GHQ score, an indicator of CMDs, showed significant correlations with sleep quality (r(GHQ,PSQI)= 0.337) and with daytime sleepiness (r(GHQ,ESS)=0.227; all p-values < 0.01). Total PSQI score exhibited a stronger correlation with individual GHQ-12 items than did total ESS score. Total PSQI score showed the highest correlation with item seven of the GHQ-12 (r =0.283), which captures participants' enjoyment of normal day-to-day activities. A comparison of the distribution of PSQI score by CMDs status is presented in Figure 1. The median PSQI score among those students without CMDs was 5, while the median PSQI score among students with CMDs was reported as 7 (p<0.001).

Table 2. Correlations of Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Total Score and Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) Score with General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)-12 Items.

| GHQ-12 Items | Spearman Correlation Coefficients* | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| PSQI score | ESS score | |

| Able to concentrate | 0.182 | 0.110 |

| Lost much sleep | 0.159 | 0.098 |

| Playing useful part | 0.152 | 0.070 |

| Capable of making decisions | 0.209 | 0.126 |

| Under stress | 0.188 | 0.115 |

| Could not overcome difficulties | 0.166 | 0.130 |

| Enjoy normal activities | 0.283 | 0.127 |

| Face up to problems | 0.221 | 0.151 |

| Feeling unhappy and depressed | 0.187 | 0.120 |

| Losing confidence | 0.233 | 0.127 |

| Thinking of self as worthless | 0.167 | 0.091 |

| Feeling reasonably happy | 0.179 | 0.119 |

| Total GHQ-12 Score | 0.337 | 0.227 |

All p<0.01

In Table 3, results from multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for demographic and behavioral covariates are presented. There was no evidence of an association between eveningness chronotype and CMDs (OR=1.22; 95% CI 0.33-4.41); however, it should be noted that few students from the sample were characterized as evening-type (1.2%), leading to limited statistical power to detect significant association. Students who exhibited daytime sleepiness had a two-fold increase odds of CMDs compared to those students who did not experience daytime sleepiness (OR=2.02; 95% CI 1.64-2.49). Additionally, students who experienced poor sleep quality had nearly 2.4-fold higher odds of CMDs than those students with good sleep quality (OR=2.36; 95% CI 1.91-2.93).

Table 3. Eveningness Chronotype, Poor Sleep Quality, and Daytime Sleepiness in Relation to Common Mental Disorders.

| Characteristic | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Age and sex adjusted OR (95% CI) | Multivariate adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronotype* | |||

| Morning type | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Evening type | 1.63 (0.47-5.63) | 1.61 (0.47-5.55) | 1.22 (0.34-4.41) |

| Sleep quality* | |||

| Good | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Poor | 2.47 (2.02-3.03) | 2.43 (1.98-2.99) | 2.36 (1.91-2.93) |

| Daytime sleepiness** | |||

| No | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Yes | 2.04 (1.69-2.48) | 2.04 (1.68-2.48) | 2.02 (1.64-2.49) |

Adjusted for age, sex, smoking, caffeinated beverages consumption, body mass index, Khat consumption and physical activity

Adjusted for age, sex, Khat use, alcohol consumption and body mass index;

Presence of common mental disorder was defined as having GHQ total score ≥5

Discussion

In this large survey of Ethiopian college students, we found that approximately one fourth of the sample population (26.6%) was classified as having CMDs. The study revealed that alcohol consumption had a statistically significant association with prevalence of CMDs. Our results also demonstrated that female students are at greater risk for CMDs (30.7%) than their male counterparts (25.9%). In the multivariate analysis, poor sleep quality and daytime sleepiness increased the odds of CMDs. To the best of our knowledge, our study is one of the first to examine associations of circadian preference, sleep quality and daytime sleepiness with CMDs among young adults in sub-Saharan Africa.

Our finding documenting higher prevalence estimates of CMDs among female students than their male counterparts is in agreement with most 30, 31 prior studies. For instance in their study of Brazilian undergraduate students, Falvigna et al32 noted that female students had a higher prevalence of sleep problems (65.7%) compared to males (54.1%). Our study results corroborate these findings as we observed a higher prevalence of poor sleep quality (56.8%) among female students, as compared with male students (52.0%). Investigators have shown that mental health problems particularly depression, anxiety and somatic complaints are more common among women than men across diverse societies and social contexts.33, 34 In LMICs pressures created by women's multiple roles and responsibilities, gender discrimination and associated factors, such as gender based violence, may be contributing to an increased burden of CMDs among female students.33-35

The results of our study support previous findings that indicate associations between poor sleep quality and daytime sleepiness with increased risk of CMDs. In a study of Mexican university students, Moo-Estrella et al36 found that students with depressive symptoms had more severe sleep disturbances and poorer sleep quality than those students without depressive symptoms (p <0.001). Depression, the most common mood disorder, is one of the leading causes of disability and the largest contributor to the global burden of disease37. In a study conducted among female college students in the United States, investigators reported that greater daytime sleepiness increased the odds of increased depressive symptoms (OR=8.0; p-value=0.005).38 Similarly Wong et al,39 in their study among Chinese undergraduates, found that poor sleep quality, particularly daytime dysfunction, was a predictor of feelings of depression and anxiety (standardized regression coefficient β=0.121, p=0.024). Our findings, indicating that daytime sleepiness and poor sleep quality increase the odds of CMDs among Ethiopian college students, are consistent with prior literature despite geographical, racial, ethnic and cultural differences in the populations considered.40, 41 Findings of a bidirectional relationship between sleep and CMDs suggest a common pathologic mechanism between the two disorders.

In previous studies, evening chronotypes have been shown to be statistically significantly associated with mental distress. In a study of university students, Digdon and Howell,42 documented a statistically significant association between eveningness chronotype and poor mental and emotional responses. Similarly, in Israel Tzischinsky and Shochat2 reported that evening chronotype individuals exhibited more sleep problem behaviors and depressed mood than intermediate and morning chronotype individuals. In the current study, we found no evidence of an association between evening chronotype and CMDs. We do not have clear explanation for these findings but we speculate that the small percentage of evening types (1.2%) in this study population might have contributed to the lack of statistical significance. Nevertheless, a higher percentage of evening-type individuals were characterized as having CMDs (26.7%) in comparison to the percentage of morning-type individuals (21.5%) with CMDs.

Potential biological mechanisms that may explain the observed associations in the study include physiological differences in the actions of tryptophan and regulation of the serotonergic system. Tryptophan has been shown to exhibit direct and indirect effects on sleep 43 and regulation of mood,44, 45 with sex differences being reported in some studies. Depletion of tryptophan reduces the synthesis of serotonin,46 a neurotransmitter associated with human feelings of well-being. In previous studies, reduced synthesis and uptake of serotonin have resulted in greater mood-altering effects in women compared to men.44 Regulation of the serotonergic system is also implicated in the regulation of sleep and maintenance of good sleep quality.43 Therefore, regulation of the serotonergic system may underlie observed relationships between sex, sleep parameters, and CMDs.

Our study has several limitations. First, because of the cross-sectional study design we cannot infer temporality from our results. It is difficult to establish whether CMDs are a result of sleep disorders or whether these sleep disorders are manifestations of prevalent mental disorders. Second, our use of a self-administered survey that relied on subjective measures of chronotype, sleep quality, and daytime sleepiness might have led to some degree of misclassification. However, the instruments used to assess these traits have shown to have good internal consistency and face validity in previous cross-cultural studies.23, 47, 48 Third, our study could be subjected to volunteer bias, because the data were collected from willing participants instead of a random sample Finally, classification of GHQ-12, MEQ, PSQI and ESS total scores into binary categories may have further introduced heterogeneity within groups and masked significant associations.

Implciations for Health Behavior and Plicy

The co-occurrence of sleep disorders and CMDs among college students is increasingly becoming an important global health issue due to the increased social demands and academic expectations placed on university students. Our study provides evidence that poor sleep quality—a predictor of daytime sleepiness—and evening chronotype demonstrate significant associations with increased risk of CMDs in Ethiopian college students. Female students and students who report regular alcohol consumption had higher odds of CMDs. In light of these findings, health promotion programs that seek to promote good sleep habits during the college years are needed. Future research with objective measures of sleep disorders and diagnostic assessments of CMDs are also needed to confirm and expand upon our findings. An enhanced research agenda should also address the pathophysiologic impact of sleep disorders on mental disorders and identify resilience factors that mitigate the influences of sleep deprivation, poor sleep quality and circadian misalignment on mental health. Such research may contribute to more effective means of preventing, diagnosing, and treating co-morbid sleep and mental health disorders among young adults globally.

Acknowledgments

Kia L. Byrd was a research training fellow with the Harvard School of Public Health Multidisciplinary International Research Training (HSPH MIRT) program when this research study was completed. The HSPH MIRT Program is supported by an award from the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities (T37-MD000149). The authors thank Addis Continental Institute of Public Health (ACIPH) for providing facilities and logistic support throughout the research process.

Footnotes

Human Subjects Approval Statement: All completed questionnaires were anonymous, and no personal identifier was used. The procedures used in this study were approved by the institutional review boards of Addis Continental Institute of Public Health and Gondar University, Ethiopia and the University of Washington, USA. The Harvard School of Public Health Office of Human Research Administration, USA, granted approval to use the de-identified data for analysis.

References

- 1.Crowley SJ, Acebo C, Fallone G, Carskadon MA. Estimating dim light melatonin onset (DLMO) phase in adolescents using summer or school-year sleep/wake schedules. Sleep. 2006;29(12):1632–1641. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.12.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tzischinsky O, Shochat T. Eveningness, sleep patterns, daytime functioning, and quality of life in Israeli adolescents. Chronobiol Int. 2011;28(4):338–343. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2011.560698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Randler C. Association between morningness-eveningness and mental and physical health in adolescents. Psychol Health Med. 2011;16(1):29–38. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2010.521564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang CK, Kim JK, Patel SR, Lee JH. Age-related changes in sleep/wake patterns among Korean teenagers. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1 Suppl):250–256. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0815G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koffel E, Watson D. The two-factor structure of sleep complaints and its relation to depression and anxiety. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118(1):183–194. doi: 10.1037/a0013945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts RE, Duong HT. Depression and insomnia among adolescents: a prospective perspective. J Affect Disord. 2013 May 15;148(1):66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pilcher JJ, Ginter DR, Sadowsky B. Sleep quality versus sleep quantity: relationships between sleep and measures of health, well-being and sleepiness in college students. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42(6):583–596. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lemma S, Gelaye B, Berhane Y, et al. Sleep quality and its psychological correlates among university students in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:237. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lohsoonthorn V, Khidir H, Casillas G, et al. Sleep quality and sleep patterns in relation to consumption of energy drinks, caffeinated beverages, and other stimulants among Thai college students. Sleep Breath. 2012;17(3):1017–1028. doi: 10.1007/s11325-012-0792-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singleton RA, Jr, Wolfson AR. Alcohol consumption, sleep, and academic performance among college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70(3):355–363. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gelaye B, Lemma S, Deyassa N, et al. Prevalence and correlates of mental distress among working adults in ethiopia. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2012;8:126–133. doi: 10.2174/1745017901208010126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdulahi H, Mariam DH, Kebede D. Burden of disease analysis in rural Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2001;39(4):271–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans DL, Charney DS. Mood disorders and medical illness: a major public health problem. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):177–180. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00639-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lund HG, Reider BD, Whiting AB, Prichard JR. Sleep patterns and predictors of disturbed sleep in a large population of college students. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(2):124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gau SS, Shang CY, Merikangas KR, et al. Association between morningness-eveningness and behavioral/emotional problems among adolescents. J Biol Rhythms. 2007;22(3):268–274. doi: 10.1177/0748730406298447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemma S, Patel SV, Tarekegn YA, et al. The Epidemiology of Sleep Quality, Sleep Patterns, Consumption of Caffeinated Beverages, and Khat Use among Ethiopian College Students. Sleep Disord. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/583510. 583510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius N, et al. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med. 1997;27(1):191–197. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abubakar A, Fischer R. The factor structure of the 12-item General Health Questionnaire in a literate Kenyan population. Stress Health. 2012;28(3):248–254. doi: 10.1002/smi.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandes AC, Hayes RD, Patel V. Abuse and other correlates of common mental disorders in youth: a cross-sectional study in Goa, India. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(4):515–523. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0614-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel V, Araya R, Chowdhary N, et al. Detecting common mental disorders in primary care in India: a comparison of five screening questionnaires. Psychol Med. 2008;38(2):221–228. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horne JA, Ostberg O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int J Chronobiol. 1976;4(2):97–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aloba OO, Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Mapayi BM. Validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) among Nigerian university students. Sleep Med. 2007;8(3):266–270. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giri P, Baviskar M, Phalke D. Study of sleep habits and sleep problems among medical students of pravara institute of medical sciences loni, Western maharashtra, India. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3(1):51–54. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.109488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akintunde AA, Okunola OO, Oluyombo R, et al. Snoring and obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome among hypertensive Nigerians: prevalence and clinical correlates. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;11:75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. [Accessed on 09/13/2013];1995 Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/trs/WHO_TRS_854.pdf. [PubMed]

- 28.WHO. Global status report on alcohol. [Acccessed on 09/13/2013];World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse. 2004 Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2004/9241562722.

- 29.Brown LD, Cai TT, DasGupta A. Interval Estimation for a Binomial Proportion Statistical Science. 2001;16(2):101–133. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patten CA, Choi WS, Vickers KS, Pierce JP. Persistence of depressive symptoms in adolescents. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(5 Suppl):S89–91. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suarez EC. Self-reported symptoms of sleep disturbance and inflammation, coagulation, insulin resistance and psychosocial distress: evidence for gender disparity. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22(6):960–968. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Falavigna A, de Souza Bezerra ML, Teles AR, et al. Sleep disorders among undergraduate students in Southern Brazil. Sleep Breath. 2011;15(3):519–524. doi: 10.1007/s11325-010-0396-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.WHO. Gender disparities in mental health. World Health Organization. Department of Mental Health, and Substance Dependence; Geneva, Switzerland: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gelaye B, Arnold D, Williams MA, et al. Depressive symptoms among female college students experiencing gender-based violence in Awassa, Ethiopia. J Interpers Violence. 2008;24(3):464–81. doi: 10.1177/0886260508317173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krieger N, Waterman PD, Hartman C, et al. Social hazards on the job: workplace abuse, sexual harassment, and racial discrimination--a study of Black, Latino, and White low-income women and men workers in the United States. Int J Health Serv. 2006;36(1):51–85. doi: 10.2190/3EMB-YKRH-EDJ2-0H19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moo-Estrella J, Perez-Benitez H, Solis-Rodriguez F, Arankowsky-Sandoval G. Evaluation of depressive symptoms and sleep alterations in college students. Arch Med Res. 2005;36(4):393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michaud CM, Murray CJ, Bloom BR. Burden of disease--implications for future research. JAMA. 2001;285(5):535–539. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.5.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Regestein Q, Natarajan V, Pavlova M, et al. Sleep debt and depression in female college students. Psychiatry Res. 2010;176(1):34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong ML, Lau EY, Wan JH, et al. The interplay between sleep and mood in predicting academic functioning, physical health and psychological health: a longitudinal study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(4):271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bower B, Bylsma LM, Morris BH, Rottenberg J. Poor reported sleep quality predicts low positive affect in daily life among healthy and mood-disordered persons. J Sleep Res. 2010;19(2):323–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, Andreski P. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39(6):411–418. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Digdon NL, Howell AJ. College students who have an eveningness preference report lower self-control and greater procrastination. Chronobiol Int. 2008;25(6):1029–1046. doi: 10.1080/07420520802553671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Voderholzer U, Hornyak M, Thiel B, et al. Impact of experimentally induced serotonin deficiency by tryptophan depletion on sleep EEG in healthy subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;18(2):112–124. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Booij L, Van der Does W, Benkelfat C, et al. Predictors of mood response to acute tryptophan depletion. A reanalysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(5):852–861. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00361-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jans LA, Riedel WJ, Markus CR, Blokland A. Serotonergic vulnerability and depression: assumptions, experimental evidence and implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12(6):522–543. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Delgado PL, Charney DS, Price LH, et al. Neuroendocrine and behavioral effects of dietary tryptophan restriction in healthy subjects. Life Sci. 1989;45(24):2323–2332. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(89)90114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adewole OO, Hakeem A, Fola A, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea among adults in Nigeria. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(7):720–725. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30983-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taoudi Benchekroun M, Roky R, Toufiq J, et al. Epidemiological study: chronotype and daytime sleepiness before and during Ramadan. Therapie. 1999;54(5):567–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]