Abstract

The use of the tripodal ligands tris[(N'-tert-butylureaylato)-N-ethyl]aminato ([H3buea]3−) and the sulfonamide-based N,N',N"-[2,2',2"-nitrilotris(ethane-2,1-diyl)]tris(2,4,6-trimethylbenzene-sulfonamidato) ([MST]3−) has led to the synthesis of two structurally distinct In(III)–OH complexes. The first example of a five-coordinate indium(III) complex with a terminal hydroxide ligand, K[InIIIH3buea(OH)], was prepared by addition of In(OAc)3 and water to a deprotonated solution of H6buea. X-ray diffraction analysis, as well as FTIR and 1H NMR spectroscopic methods, provided evidence for the formation of a monomeric In(III)–OH complex. The complex contains an intramolecular hydrogen bonding (H-bonding) network involving the In(III)–OH unit and [H3buea]3− ligand, which aided in isolation of the complex. Isotope labeling studies verified the source of the hydroxo ligand as water. Treatment of the [InIIIMST] complex with a mixture of 15-crown-5 ether and NaOH led to isolation of the complex [15-crown-5⊃NaI-(μ-OH)-InIIIMST], whose solid-state structure was confirmed using X-ray diffraction methods. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies on this complex suggest it retains its heterobimetallic structure in solution.

Introduction

Group 13 metal complexes with hydroxo ligands have been implicated as the competent species in several polymerization and hydrolytic reactions [1–4]. Much effort has gone into the development of Al(III)–OH complexes [5–7], yet less is known of the properties for other M(III)–OH complexes of this group. In particular, crystallographically characterized indium complexes bearing terminal hydroxo ligands are uncommon; a survey of the Cambridge Crystallographic Database found only six examples, most of which are contained within metalorganic frameworks [8–12]. The isolation of discrete In(III)–OH complexes is much rarer, with only two examples, suggesting that methods toward their preparation are still necessary. The scarcity of terminal hydroxo indium complexes is due in part to the tendency of hydroxide ions to bridge between metal centers [13–17], and there are many examples of systems containing bridging In(III)–(μ-OH)–In(III) units [17–21]. Far fewer examples of heterometallic systems involving In(III)–OH are known, with only 9 crystallographically characterized species [22–26].

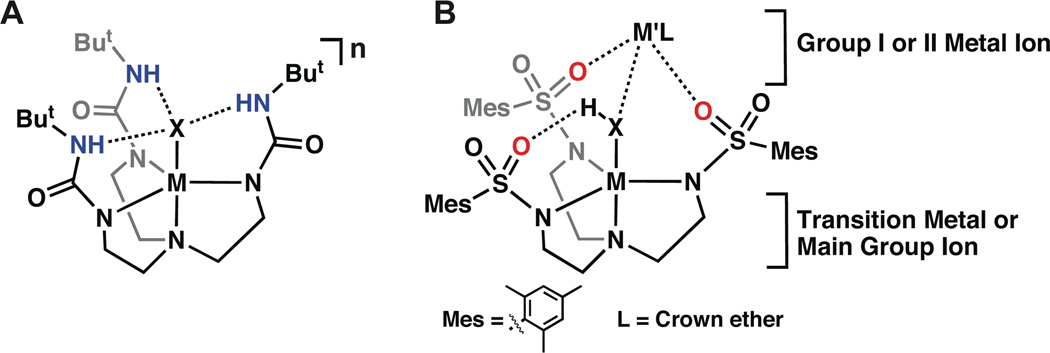

One method toward stabilizing discrete metal-bound hydroxide units is to regulate the secondary coordination sphere around the M–OH [27–31]. In particular, the utilization of non-covalent interactions has been shown to effectively stabilize transition metal-oxo and hydroxo species. Several types of systems have been used to probe these effects, with intramolecular hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) being one of the most common [32]. Our group has developed several tetradentate ligands that position hydrogen bond donors or acceptors proximal to a M–OH unit to promote the formation of intramolecular H-bonds [28–29,33–37]. These ligands form C3-symmetric complexes containing cavities in which an exogenous ligand can coordinate. Indium complexes with ligand scaffolds enforcing trigonal bipyramidal geometries are unusual, and five-coordinate indium complexes containing a terminal hydroxo ligand are to our knowledge unknown. In this report we describe the preparation and properties of a monomeric In(III)–OH complex with an intramolecular H-bonding network that stabilized the In(III)–OH unit (Fig. 1A). A second complex is also described that contains an InIII(μ-OH)NaI core, whose bimetallic structure is present in both the solution and the solid-state (Fig. 1B). These two complexes illustrate different approaches to stabilize In(III)–OH units within coordination complexes.

Fig. 1.

General diagram of metal complexes derived from the ligands [H3buea]3− (A) and [MST]3− (B).

Experimental

General Methods

All reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used as received, unless otherwise noted. Sodium hydride (NaH) and potassium hydride (KH) reagents were each purchased as 30% dispersions in mineral oil; both were filtered with a medium-porosity glass frit, washed with five charges each of Et2O and pentane, and dried in vacuo prior to use. Solvents were sparged with argon and dried over columns containing Q-5 and molecular sieves. The syntheses of H6buea and H3MST were carried out according to literature procedures [37–38]. The syntheses of metal complexes were conducted in a Vacuum Atmospheres Co. (Hawthorne, CA) drybox under an argon atmosphere.

Physical Methods

Elemental analyses were obtained from Desert Analytics (Tucson, AZ) or on a Perkin–Elmer 2400 CHNS analyzer. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were collected on a Varian 800 Scimitar Series FTIR spectrometer with values reported in wavenumbers. 1H NMR and 13C{1H} NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker DRX500 (500 MHz) spectrometer equipped with Silicon Graphics workstations. Chemical shifts were referenced to the residual solvent peak.

Preparation of the Complexes

K[InIIIH3buea(OH)]

H6buea (200 mg, 0.453 mmol) in 4 mL of dimethylacetamide (DMA) was treated with solid KH (7.4 mg, 1.8 mmol) and allowed to stir for 2 h. Solid In(OAc)3 (132 mg, 0.452 mmol) was then added to the solution and stirred for an additional 30 min. The reaction was filtered with a medium-porosity glass fritted funnel to remove insoluble KOAc (116 mg, 1.18 mmol). The filtrate was treated with 1 equiv of water (8.2 µL, 0.45 mmol), stirred for additional 30 min, and filtered. Colorless crystals were obtained by vapor diffusion of Et2O into the DMA filtrate. The crystals were isolated, washed with Et2O, and dried in vacuo to yield 56 mg (20%) of the product. 1H NMR (500MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm): 1.19 (br s, 27H), 2.45 (br s, 6H), 2.99 (br s, 6H),. 13C{1H} NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm): 29.8, 37.2, 37.5, 49.4, 50.3, 157.8. FTIR (Nujol, selected bands, cm−1) ν(16OH) 3646; ν(18OH) 3635; ν(NH) 3298; 1612, 1593, 1527, 1318. Anal. Calcd for K[InIIIH3buea(OH)]·Et2O, C25H53InKN7O5: C, 43.79; H, 7.79; N, 14.30. Found: C, 43.38; H, 7.09; N, 14.94. The same preparation was followed for the preparation of K[InIIIH3buea(18OH)] substituting H218O for H216O.

[15-crown-5⊃NaI-(μ-OH)-InIIIMST]

A suspension of H3MST (323 mg, 0.467 mmol) and NaH (34.7 mg, 1.45 mmol) in 5 mL of DMA was allowed to stir for 45 min. After H2 evolution ceased, In(OAc)3 (137 mg, 0.469 mmol) was added and the solution stirred vigorously. After 2 h, 5 mL of Et2O was added and the solution stirred for an additional 30 min, followed by filtration (see Note). The filtrate was concentrated to dryness under reduced pressure, then the residue was triturated with Et2O and dried to afford a white precipitate. The solid was collected in a medium-porosity glass fritted funnel, washed with Et2O and pentane, and dried in vacuo to yield 356 mg (~90 %) of a white powder, which was used without further purification. 1H NMR (500MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm): 2.22 (s, 9H), 2.52 (br t, 6H), 2.58 (s, 18H), 2.80 (br t, 6H), 6.87 (s, 6H). A suspension of this white powder that was assumed to be [InMST] (117 mg, 0.145 mmol), NaOH (6.3 mg, 0.16 mmol) and 15-crown-5 (46 µL, 0.23 mmol) in 4 mL THF was allowed to stir for 8 h, after which the mixture was filtered with a medium-porosity glass fritted funnel into a vial. Diethyl ether was slowly allowed to diffuse into the vial and within 1 d a white powdery residue formed, which was removed via filtration and the filtrate was again exposed to Et2O vapor. Over the next 5 days colorless crystals formed, which were collected, washed with Et2O, and dried in vacuo to yield 65 mg (40%) of the product. 1H NMR (500MHz, CDCl3, ppm): 1.79 (s, OH), 2.26 (s, 9H), 2.58 (t, 6H), 2.72 (s, 18H), 2.92 (t, 6H), 3.62 (m, 20H), 6.87 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, ppm): 21.0, 23.6, 40.2, 52.9, 69.4, 131.4, 136.5, 139.4, 140.0. FTIR (Nujol, selected bands, cm−1) ν(OH) 2 3561; 1602, 1563, 1113, 975, 817, 653. Anal. Calcd for [15-crown-5⊃NaI-(μ-OH)-InIIIMST], C47H76InN4NaO13S3: C, 49.24; H, 6.64; N, 5.10. Found: C, 49.56; H, 6.72; N, 4.92.

Crystallographic Methods

Pertinent crystallographic data are contained in Table 1, and full crystallographic details have been included in the supporting information. For K[InIIIH3buea(OH)], the hydrogen atoms H1, H5, H6 and H7 were located and refined from a difference-Fourier map, and all others were included using a riding model. One molecule of Et2O was present in the structure. For [InIII(μ-OH)NaI], the hydrogen atom H1 was located on a difference-Fourier map and refined with d(O-H) = 0.85Å. The remaining hydrogen atoms were included using a riding model. There was one-half molecule of Et2O solvent present, which was located on a two-fold rotation axis. There were several disordered carbon and oxygen atoms within both the 15-crown-5 ether and the ethylene arms of the tren backbone. These atoms were included using multiple components with partial site-occupancy-factors.

Table 1.

Crystallographic Collection Data for K[InH3buea(OH)] and ([InIII(μ-OH)NaI]).

| K[InH3buea(OH)]•Et2O | [InIII(μ-OH)NaI]·½ Et2O | |

|---|---|---|

| formula | C25H53InKN7O5 | C435H71InN4NaO12.5S3 |

| fw | 685.66 | 1102.05 |

| T (K) | 153(2) | 198(2) |

| space group | P-1 | C2/c |

| a (Å) | 10.451(3) | 32.4319(12) |

| b (Å) | 12.023(3) | 13.6329(5) |

| c (Å) | 13.577(3) | 26.3748(10) |

| a (deg) | 82.766(4) | 90 |

| b (deg) | 84.880(4) | 116.8822(1) |

| g (deg) | 80.609(4) | 90 |

| Z | 2 | 8 |

| V (Å3) | 3621.4(3) | 10401.2(7) |

| dcalcd (Mg/m3) | 1.367 | 1.408 |

| R1a | 0.0322 | 0.0259 |

| wR2b | 0.0845 | 0.0647 |

| GOFc | 1.066 | 1.022 |

R1 = Σ||Fo|−|Fc|| / Σ|Fo|;

wR2 = [Σ[w(Fo2−Fc2)2] / Σ[w(Fo2)2] ]1/2;

GOF = S = [Σ[w(Fo2−Fc2)2] / (n−p)]1/2 where n = number of reflections and p = total number of parameters refined.

Results and Discussion

General Ligand Considerations

This study utilized the urea-based compound tris[(N'-tert-butylureayl)-N-ethyl]amine (H6buea) [35–37] and the sulfonamide-based N,N',N"-[2,2',2"-nitrilotris(ethane-2,1-diyl)]tris(2,4,6-tri-methylbenzenesulfonamide) (H3MST) [38]. Thrice deprotonation of both compounds formed trianionic N4 ligands, which after metal ion binding formed cavities around vacant coordination sites (Figure 1). Both systems have cavity architectures that provided additional stabilization through the use of non-covalent interactions with the In(III)–OH units. Our group and others, including Millar, have previously used this approach in stabilizing related transition metal complexes [30–31,34,36,39–40]. Transition metal complexes with [H3buea]3− can stabilize M–OH and M–oxo units through the establishment of intramolecular H-bonding networks. The sulfonamido ligand, [MST]3− (Figure 1B) binds a metal ion to produce a cavity in which three of the sulfonamide oxygen atoms are poised to form the scaffolding of a cavity. The SO2R groups in transition metal complexes of [MST]3− have been shown to accept H-bonds from M–OH units. We have also shown that the sulfonamide oxygen atoms can bind an additional metal ion, to form heterobimetallic complexes, whereby the hydroxo ligand bridges between two different metal ions [38]. We demonstrate in this report that [InIIIH3buea(OH)]− is a monomeric complex containing the expected intramolecular H-bonding network, whereas the In(III)–OH complex with [MST]3− was isolated as a heterobimetallic complex having a InIII(μ-OH)NaI core.

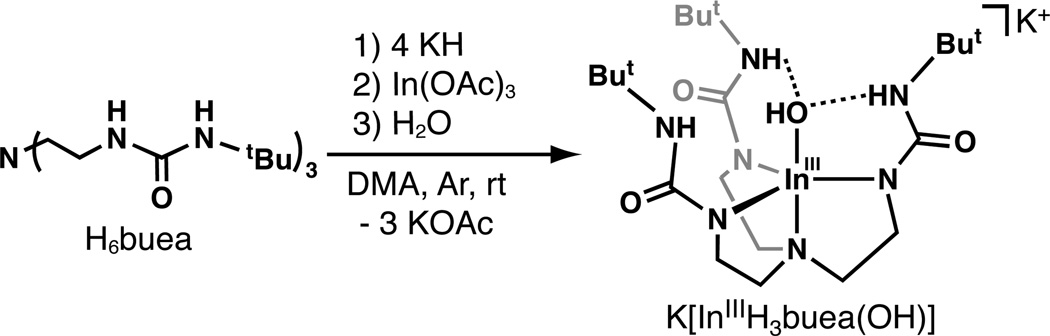

Synthesis and Properties of [InIIIH3buea(OH)]−

The preparation [InIIIH3buea(OH)]− followed the procedure outlined in Scheme 1. Deprotonation of H6buea was accomplished using KH suspended in dimethylacetamide (DMA), which then treated with In(OAc)3. Removal of insoluble KOAc (87%) and subsequent addition of an equivalent of H2O afforded K[InIIIH3buea(OH)], which was obtained as pure colorless crystals by vapor diffusion of Et2O into a concentrated DMA solution. Note that in our hands, In(OAc)3 appeared to contain an impurity, which from Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) experiments appear to consist of an In(III)–OH unit that we were unable to remove upon purification: the presence of this impurity could account for the lower than expected amount of KOAc isolated.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of K[InIIIH3buea(OH)]

The vibrational properties of K[InIIIH3buea(OH)] were probed using FTIR spectroscopy. The solid-state FTIR spectrum displays a sharp peak at 3646 cm−1, indicative of a metal-bound hydroxo ligand. An isotopic labeling study was performed to verify this assignment and show that water was the source of the hydroxo ligand. Using H218O to prepare the complex led to a red-shift of the ν(OH) band from 3646 to 3635 cm−1. This shift of 11 cm−1 agrees with that predicted for a simple harmonic O–H oscillator (ν(16OH)/ν(18OH) = 1.003; calcd 1.003). In addition, a broad band at 3298 cm−1 was observed and assigned to the ν(NH) vibration. The energy and shape of this signal is similar to features found in other M(III)–OH complexes with [H3buea]3− and suggests the presence of H-bonding interactions between the urea moieties and the bound hydroxo ligand.

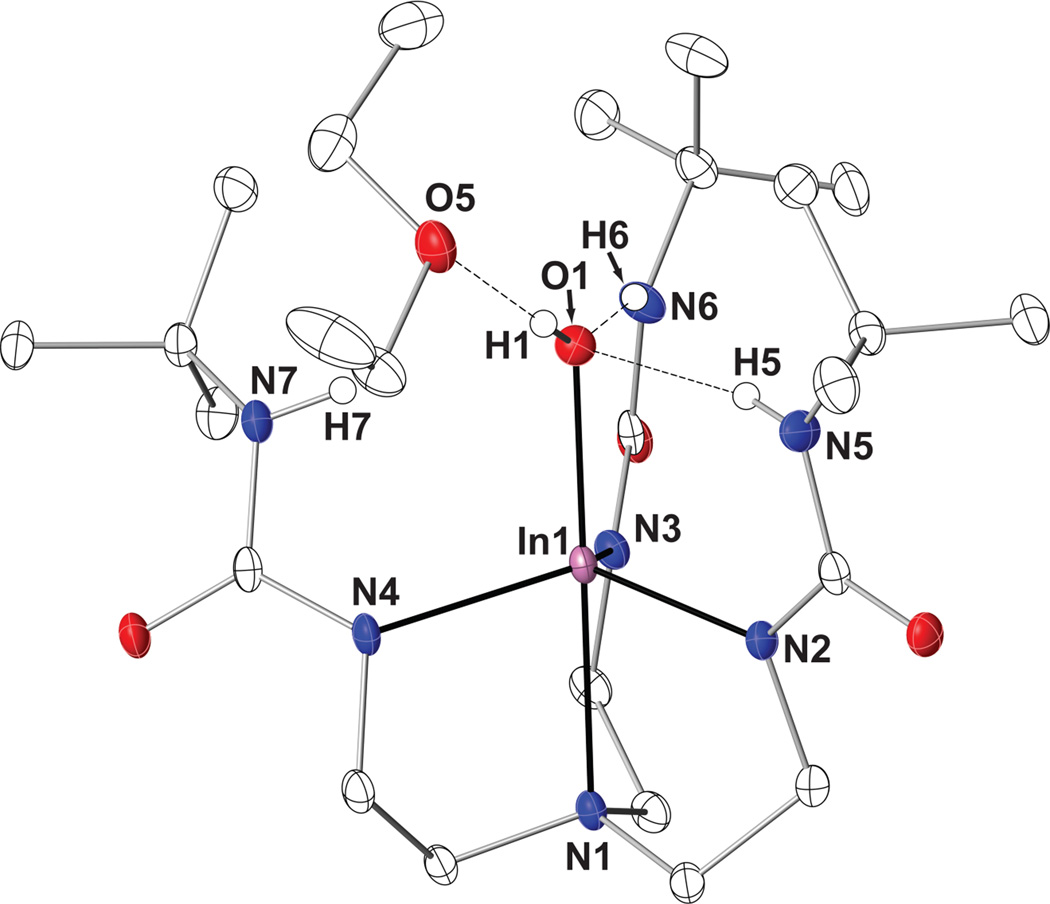

Molecular Structure of [InIIIH3buea(OH)]−

The molecular structure of [InIIIH3buea(OH)]− was determined by X-ray diffraction methods and found to contain a slightly distorted trigonal bipyramidal In(III) center (τ = 0.95) [41] with a N4O primary coordination sphere (Fig. 2, Table 2). The In1–O1 bond length is 2.073(2) Å, with an O1-In1-N1 bond angle of 177.26(6)°. The three anionic nitrogen donors N2, N3, and N4 form the equatorial plane, having an average In–Neq bond length of 2.145(6) Å. The apical nitrogen atom N1 completes the primary coordination sphere, having an In1–N1 bond distance of 2.353(2) Å. The indium center is displaced out of the equatorial plane by 0.434 Å. To our knowledge, this is the first example of a five-coordinate indium compound with a terminal hydroxo unit.

Fig. 2.

Thermal ellipsoid plot for [InIIIH3buea(OH)]−·Et2O with thermal ellipsoids shown at 50% probability. Only the urea and hydroxo hydrogen atoms are shown clarity.

Table 2.

Selected Bond Distances and Angles for K[InIIIH3buea(OH)]·Et2O and [15-crown-5⊃NaI-(μ-OH)-InIIIMST].

| K[InIIIH3buea(OH)] | [InIII(μ-OH)NaI] | |

|---|---|---|

| Distance (Å) | ||

| In1–N1 | 2.3533(18) | 2.4056(14) |

| In1–N2 | 2.1315(18) | 2.1615(15) |

| In1–N3 | 2.1469(17) | 2.1650(14) |

| In1–N4 | 2.1592(17) | 2.1851(14) |

| In1–O1 | 2.0729(17) | 2.0096(12) |

| O1–Na1 | – | 2.2636(14) |

| Angle (deg) | ||

| N1-In1-O1 | 177.26(6) | 176.94(5) |

| N2-In1-N3 | 117.27(7) | 114.60(6) |

| N2-In1-N4 | 120.46(7) | 112.46(6) |

| N3-In1-N4 | 110.23(7) | 113.30(6) |

| N1-In1-N2 | 78.24(6) | 74.97(5) |

| N1-In1-N3 | 78.59(6) | 75.36(5) |

| N1-In1-N4 | 78.16(6) | 74.32(5) |

| N5⋯O1 | 3.102(5) | – |

| N6⋯O1 | 2.827(5) | – |

| N7⋯O1 | 2.933(5) | – |

| O5⋯O1 | 2.916(5) | – |

| O6⋯O1 | – | 2.863(5) |

| d(In–pNeq) | 0.434(4) | 0.566(4) |

Binding of a hydroxo ligand within the cavity formed by [H3buea]3− established an intramolecular H-bonding network. According to the molecular structure, N6–H6 and N5–H5 form intramolecular H-bonds to the bound hydroxo anion, with N…O1 distances of 2.827 Å and 2.933 Å, respectively. Of note is a slight elongation of N7–H7 from O1 (N7…O1 distance of 3.102 Å), which is just out of the range normally associated with H-bonds (less than 3 Å). In addition, a solvated Et2O molecule was found in the crystal that is within H-bonding distance to the hydroxo ligand (O1…O5 distance of 2.916 Å.)

NMR Spectroscopy

The solution properties of K[In(III)H3buea] were further explored via nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. The 1H NMR spectrum of K[InIIIH3buea(OH)] in DMSO-d6 at 298 K contains several broadened resonances. Signals at 2.45 and 2.99 ppm were identified as protons from the methylene groups in the tren backbone of the ligand. Two large singlets at 1.19 and 1.21 ppm comprised the proton resonances from the tert-butyl groups. Variable temperature analysis on the solution revealed that coalescence of these resonances occurs around 323 K, suggesting that at room temperature the ethylene and tert-butyl groups exist in at least two major conformations. Based on this limited information, it is not certain as to the cause of this dynamic behavior. The poor solubility of K[InIIIH3buea(OH)] in solvents other than DMSO-d6 prevented low-temperature NMR analyses. Neither the signal from the NH nor the OH proton could be located in the NMR spectrum.

Synthesis and Structure of [15-crown-5⊃NaI-(μ-OH)-InIIIMST]

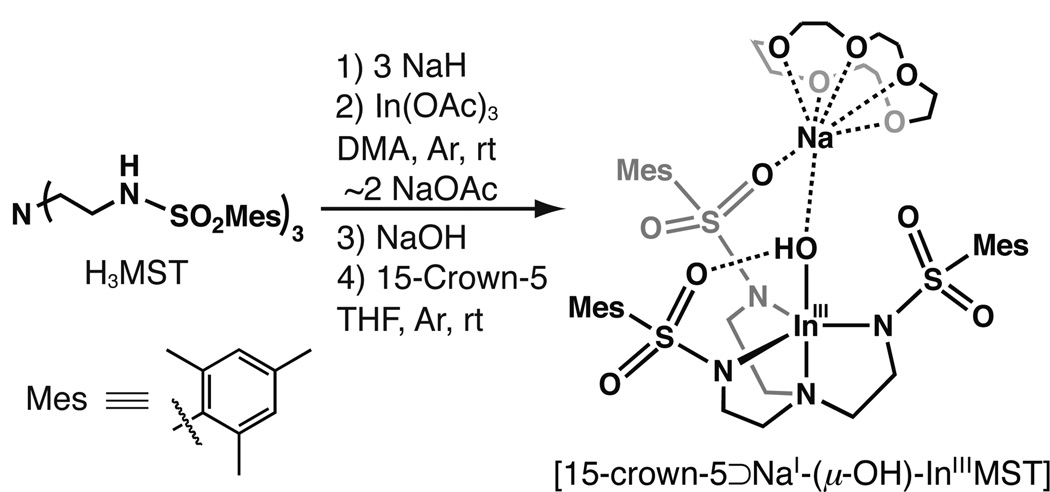

The deprotonation of H3MST was also conducted in DMA with 3 equiv of NaH, after which In(OAc)3 was added (Scheme 2). Following metal ion binding and subsequent removal of NaOAc from the reaction mixture, a white solid was isolated in good yield. Treating this putative [InMST] precursor with NaOH and 15-crown-5 in THF afforded the heterobimetallic complex [15-crown-5⊃NaI-(μ-OH)-InIIIMST] ([InIII(μ-OH)NaI]), which could be obtained as colorless crystals from vapor diffusion of Et2O into a concentrated THF solution.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of [15-crown-5⊃NaI-(μ-OH)-InIIIMST]

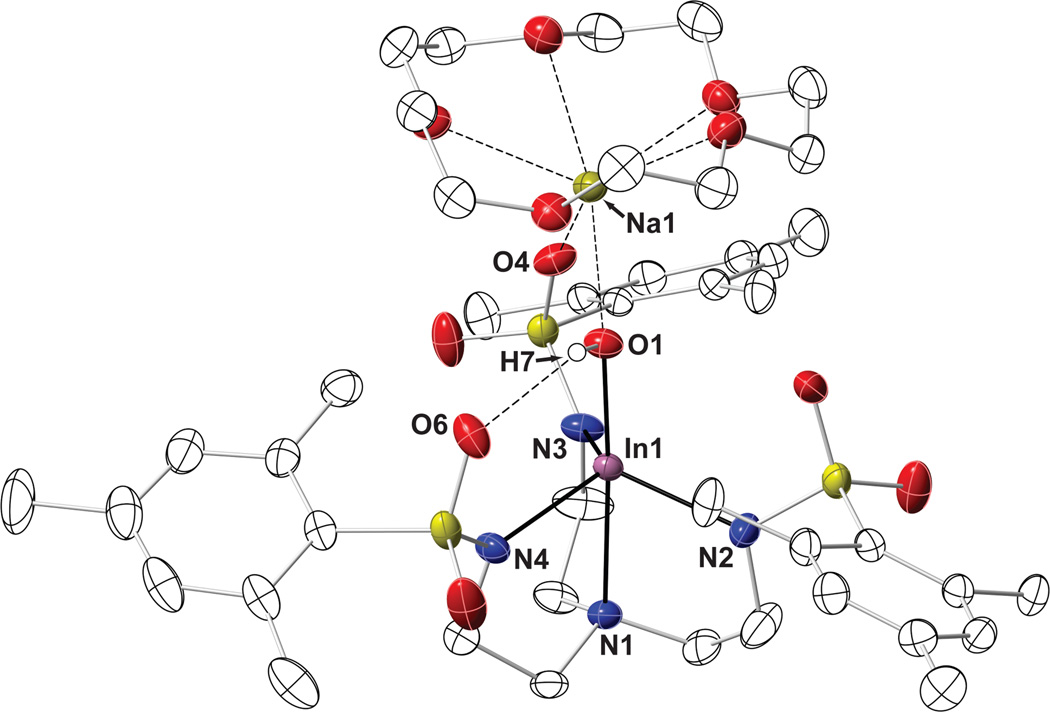

The solid-state structure of [15-crown-5⊃NaI-(μ-OH)-InIIIMST] revealed the expected five-coordinate In(III) center with a N4O primary coordination environment (Figure 3) that is similar to what was observed in [In(III)H3buea(OH)]−. The apical nitrogen atom (N1) and the equatorial sulfonamido nitrogen groups (Neq) bind to the indium center with In1–N1 and average In–Neq distances of 2.406(1) Å and 2.171(3) Å, respectively. The remaining coordination site is occupied by a hydroxo ligand, having an In1–O1 bond length of 2.010(1) Å and a N1-In1-O1 bond angle of 176.94(5)°. This complex exhibited a distorted trigonal bipyramidal geometry, with an average Neq-In-Neq angle of 113.45(9)°. The indium center is positioned 0.566(4) Å from the equatorial plane toward the hydroxo ligand.

Fig. 3.

Thermal ellipsoid plot for [15-crown-5⊃NaI-(μ-OH)-InIIIMST] with thermal ellipsoids drawn at 50% probability. Non-hydroxo protons, disordered atoms, and solvent molecules have been omitted for clarity.

The molecular structure of [InIII(μ-OH)NaI] also showed that the hydroxo ligand forms an intramolecular H-bond with O6 of the [MST]3− ligand (O1…O6 distance is 2.863(3) Å), a premise that is supported by solid-state FTIR studies that found a broadened ν(OH) peak at 3561 cm−1. The hydroxo ligand, along with O4, is also coordinated to a Na+ ion, with Na–O1 and Na–O4 bond distances of 2.264(1) Å and 2.455(1) Å, respectively. The five oxygen atoms of the 15-crown-5 occupy the remaining ion coordination sites on the sodium ion (avg. Na–O15C5 = 2.527(7) Å). The structure of [InIII(μ-OH)NaI] resembles that recently found for the related heterobimetallic complex, [15-crown-5⊃CaII-(μ-OH)-MnIIIMST], which has an MnIII(μ-OH)CaII core [38]. These structural findings further illustrate the ability of the [MST]3− ligand to bind two dissimilar metal ions.

NMR Spectroscopy of [InIII(μ-OH)NaI]

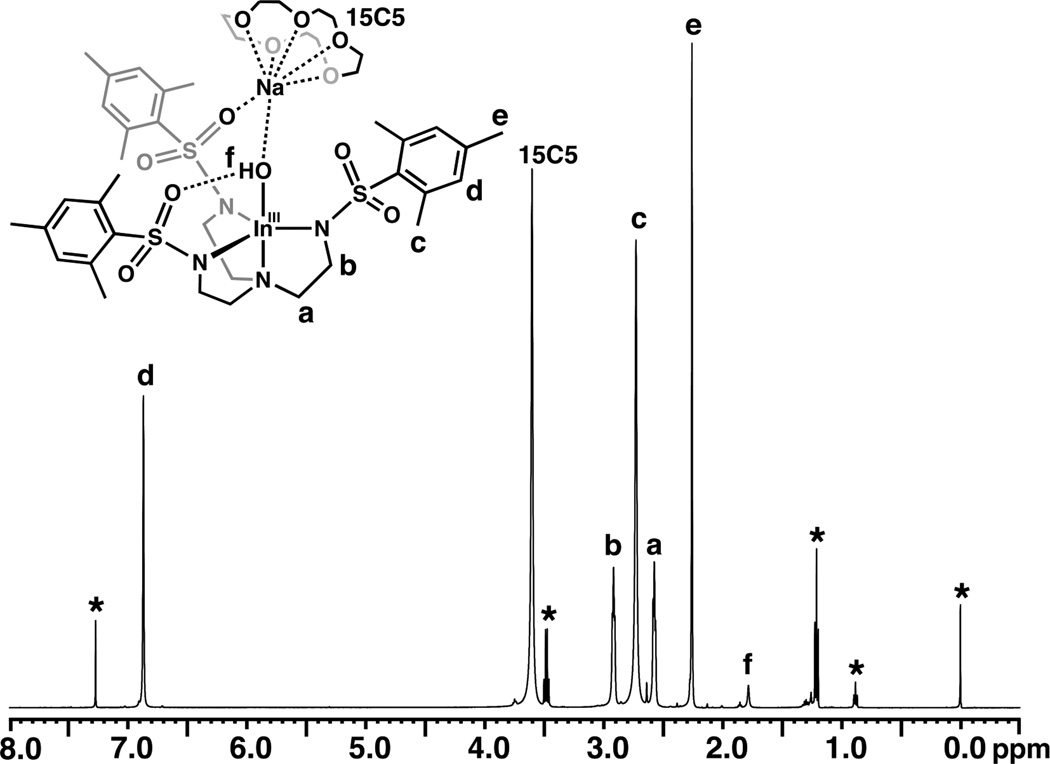

The structure of [InIII(μ-OH)NaI] in solution was probed with 1H NMR spectroscopy. At 298 K in CDCl3, the complex has C3 symmetry, as gauged by the single set of resonances observed for each type of protons. The methylene protons in the tren backbone appear as triplets at 2.58 and 2.92 ppm, and signals appearing as singlets at 2.26, 2.72, and 6.87 ppm are attributed to the mesityl protons (Fig. 4). The 15-crown-5 protons are at 3.16 ppm and are a singlet at room temperature. The hydroxo proton was found at a chemical shift of 1.79 ppm and can be readily exchanged upon the addition of D2O.

Fig. 4.

1H NMR spectrum of [15-crown-5⊃NaI-(μ-OH)-InIIIMST] at 298 K in CDCl3. The asterisks denote residual solvent peaks.

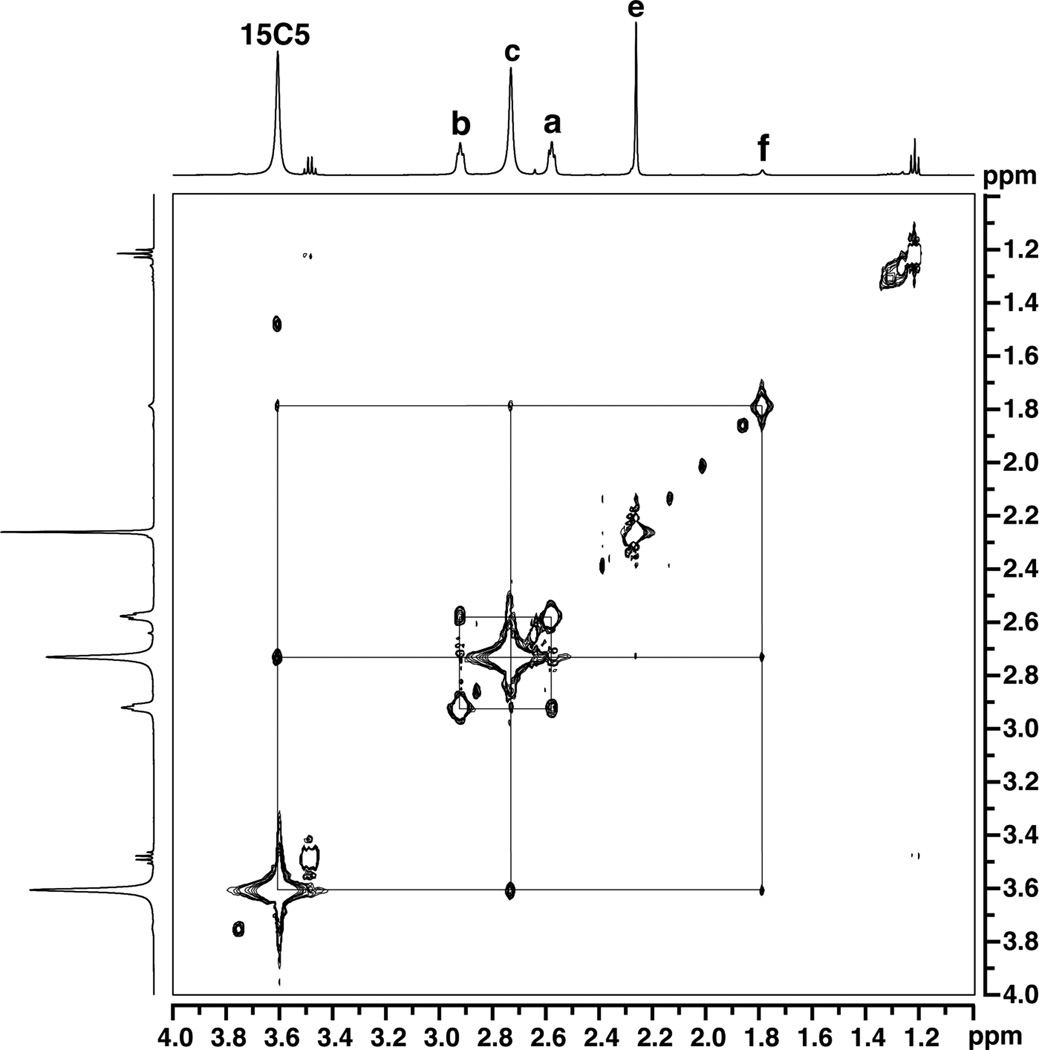

To elucidate the solution structure of [InIII(μ-OH)NaI], spectra using the Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOESY) were obtained. From the NOESY spectrum in CDCl3 at 298 K, several through-space interactions were observed (Figs. 5 and S1). The 15-crown-5 signal showed cross peaks corresponding to each of the three mesityl resonances from the [MST]3− ligand, indicative of the spatial proximity of these groups in solution. Furthermore, the hydroxo proton resonance showed NOE enhancements with both the 15-crown-5 methylene groups and the ortho methyl groups from the mesityl units. These observations resemble those found for the solid-state structure of the complex, which illustrated that the hydroxo ligand proton lies within 4 Å of the crown ether and ortho-methyl protons of [MST]3−. Taken together, these data suggest that the [InIII(μ-OH)NaI] complex remains intact in solution.

Fig. 5.

1H NOESY spectrum of [15-crown-5⊃NaI-(μ-OH)-InIIIMST] in CDCl3 at 298 K. The NOE cross peaks are indicated by the drawn lines. The labeling convention is the same as Fig. 4. A full view of the spectrum can be found in Fig. S1.

Variable temperature NMR experiments were performed to further probe the dynamic nature of the system. When the solution was cooled, the 15-crown-5 singlet split into a doublet of broadened multiplets, with a coalescence temperature of 258 K (Fig. S2). The splitting of these signals is suggestive of a diastereotopic differentiation of the methylene protons. Based on the solid-state structure of [InIII(μ-OH)NaI], the 15-crown-5 protons indeed seem to be in two distinct chemical environments, half positioned toward the cavity and half exposed to the solvent. This observation further supports the premise that the InIII(μ-OH)NaI core persists in the solution state.

4. Conclusions

By utilizing tripodal N4 donor ligands to bind indium(III) ions, new types of In(IIII)–OH complexes could be obtained. The ligands [H3buea]3− and [MST]3− can bind metal ions to enforce similar primary coordination spheres, and both establish cavities in which secondary coordination sphere effects aid in stabilizing a fifth hydroxo ligand. However, complexes derived from H6buea and H3MST exhibit distinct intramolecular noncovalent interactions in the secondary sphere, as demonstrated in this report. For K[InIIIH3buea(OH)], ureayl NH groups stabilize the first example of a terminal In(III)–OH complex in trigonal bipyramidal coordination geometry. Isotopic labeling studies confirmed that the hydroxo ligand was derived from water. The complex [15-crown-5⊃NaI-(μ-OH)-InIIIMST] was also synthesized and crystallographically characterized, a rare example of a monomeric heterobimetallic system containing an InIII(μ-OH)NaI core. Furthermore, 1H NMR spectroscopic studies demonstrated that the core structure remained assembled in solution.

CCDC 884598 and 884599 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for K[InIIIH3buea(OH)]·Et2O and [15-crown-5⊃NaI-(μ-OH)-InIIIMST]. These data can be obtained free of charge via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/conts/retrieving.html, or from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: (+44) 1223-336-033; or deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank the NSF (0738252) and the University of California-Irvine for support of this work.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Variable temperature 1H (Fig. S1) and NOESY spectra for [15-crown-5⊃NaI-(μ-OH)-InIIIMST] (Fig. S2).

References

- 1.Yang Y, Gurubasavaraj PM, Ye H, Zhang Z, Roesky HW, Jones PG. J. Organomet. Chem. 2008;693:1455–1461. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kissounko DA, Zabalov MV, Brusova GP, Dmitrii AL. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2006;75:351. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roesky HW, Walawalkar MG, Murugavel R. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001;34:201–211. doi: 10.1021/ar0001158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen EY-X, Marks TJ. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:1391–1434. doi: 10.1021/cr980462j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bai G, Singh S, Roesky HW, Noltemeyer M, Schmidt H-G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:3449–3455. doi: 10.1021/ja043585w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Müller E, Bürgi H-B. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1987;70:520–533. [Google Scholar]

- 7.González-Gallardo S, Jancik V, Cea-Olivares R, Toscano RA, Moya-Cabrera M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:2895–2898. doi: 10.1002/anie.200605081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu X, Lu Z-H, Xu Q. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:7400–7402. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02808h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samanamú CR, Richards AF. Polyhedron. 2007;26:923–928. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samanamú CR, Lococo PM, Richards AF. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2007;360:4037–4043. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Shi S, Ye J, Fang Q, Fan Y, Li D, Xu J, Song T. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2005;8:271–273. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abram S, Maichle-Mössmer C, Abram U. Polyhedron. 1998;17:131–143. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu AJ, Penner-Hahn JE, Pecoraro VL. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:903–938. doi: 10.1021/cr020627v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mirica LM, Ottenwaelder X, Stack TDP. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:1013–1045. doi: 10.1021/cr020632z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis EA, Tolman WB. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:1047–1076. doi: 10.1021/cr020633r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurtz DM., Jr Chem. Rev. 1990;90:585–606. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Junk PC, Skelton BW, White AH. Aust. J. Chem. 2006;59:147–154. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gómez-Lor B, Gutiérrez-Puebla E, Iglesias M, Monge MA, Ruiz-Valero C, Snejko N. Chem. Mater. 2005;17:2568–2573. doi: 10.1021/ic0111482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acosta-Ramírez A, Douglas AF, Yu I, Patrick BO, Diaconescu PL, Mehrkhodavandi P. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:5444–5452. doi: 10.1021/ic100185m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin Z-z, Jiang F-l, Yuan D-q, Chen L, Zhou Y-f, Hong M-c. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2005;2005:1927–1931. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wieghardt K, Kleine-Boymann M, Nuber B, Weiss J. Inorg. Chem. 1986;25:1654–1659. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linti G, Buhler M, Monakhov KY, Zessin T. Dalton Trans. 2009:8071–8078. doi: 10.1039/b908450a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mensinger ZL, Gatlin JT, Meyers ST, Zakharov LN, Keszler DA, Johnson DW. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:9484–9486. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanudo EC, Muryn CA, Helliwell MA, Timco GA, Wernsdorfer W, Winpenny REP. Chem. Commun. 2007:801–803. doi: 10.1039/b613877b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bühler M, Linti G, Anorg Z. Allg. Chem. 2006;632:2453–2460. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rominger F, Müller A, Thewalt U. Chem. Ber. 1994;127:797–804. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allred RA, Huefner SA, Rudzka K, Arif AM, Berreau LM. Dalton Trans. 2007:351–357. doi: 10.1039/b612748g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucas RL, Zart MK, Murkerjee J, Sorrell TN, Powell DR, Borovik AS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:15476–15489. doi: 10.1021/ja063935+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borovik AS. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005;38:54–61. doi: 10.1021/ar030160q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rivas JCM, Prabaharan R, Torres Martin de Rosales R, Metteau L, Parsons S. Dalton Trans. 2004:2800–2807. doi: 10.1039/B407790C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wada A, Honda Y, Yamaguchi S, Nagatomo S, Kitagawa T, Jitsukawa K, Masuda H. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:5725–5735. doi: 10.1021/ic0496572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shook RL, Peterson SM, Greaves J, Moore C, Rheingold AL, Borovik AS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:5810–5817. doi: 10.1021/ja106564a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shook RL, Borovik AS. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:3646–3660. doi: 10.1021/ic901550k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng GKY, Ziller JW, Borovik AS. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:7922–7924. doi: 10.1021/ic200881t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacBeth CE, Gupta R, Mitchell-Koch KR, Young VG, Jr, Lushington GH, Thompson WH, Hendrich MP, Borovik AS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:2556–2567. doi: 10.1021/ja0305151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacBeth CE, Hammes BS, Young VG, Jr, Borovik AS. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:4733–4741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacBeth CE, Golombek AP, Young VG, Jr, Yang C, Kuczera K, Hendrich MP, Borovik AS. Science. 2000;289:938–941. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park YJ, Ziller JW, Borovik AS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:9258–9261. doi: 10.1021/ja203458d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Millar M, Nguyen D, Voorhies H, Beatty S, Haff J, Dejean F. Book of Abstracts, 216th ACS National Meeting, Boston, August 23–27, 1998. Washington DC: American Chemical Society; 1998. INOR-351. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szajna-Fuller E, Chambers BM, Arif AM, Berreau LM. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:5486–5498. doi: 10.1021/ic061316w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Addison AW, Rao TN, Reedijk J, Van RJ, Verschoor GC, Chem J. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1984:1349–1356. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.