Abstract

Details of the pathophysiologic mechanisms that underlie complex disorders, such as the thrombo-occlusive events associated with myocardial infarction, stroke, and venous thromboembolism, are challenging to address. Recent advances have been made through the application of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to identify genetic loci associated with plasma levels of procoagulant proteins and risk of thrombotic disease. GWAS have consistently identified the gene encoding syntaxin-binding protein 5 (STXBP5) in this context. STXBP5 is expressed in both endothelium and platelets, and SNPs within the STXBP5 locus have been associated with plasma levels of vWF and increased venous thrombosis risk. In this issue of the JCI, two complementary reports from the laboratories of Charles Lowenstein and Sidney Whiteheart describe studies that highlight the complexity of the function of STXBP5 in control of storage granule development and exocytosis in platelets and endothelium. Together, these studies demonstrate that STXBP5 differentially regulates exocytosis in these two cell types. While STXBP5 facilitates granule release from platelets, it inhibits secretion from the Weibel-Palade bodies (WPBs) of endothelial cells.

Background

Thrombo-occlusive cardiovascular disease remains a major cause of death globally. It is well documented that the mechanisms that coordinate these pathologies are multifactorial and involve both genetic and acquired risk factors (1). Key players in thrombo-occlusive events are the vascular endothelium and platelets, both of which are involved in maintaining vascular integrity and normal hemostatic responses (2). However, under pathophysiologic circumstances, activation of the endothelium and platelets can trigger the release of procoagulant and cellular-adhesive molecules that can interact to promote the development of thrombotic events (3, 4).

STXBP5 as a regulator of cardiovascular homeostasis

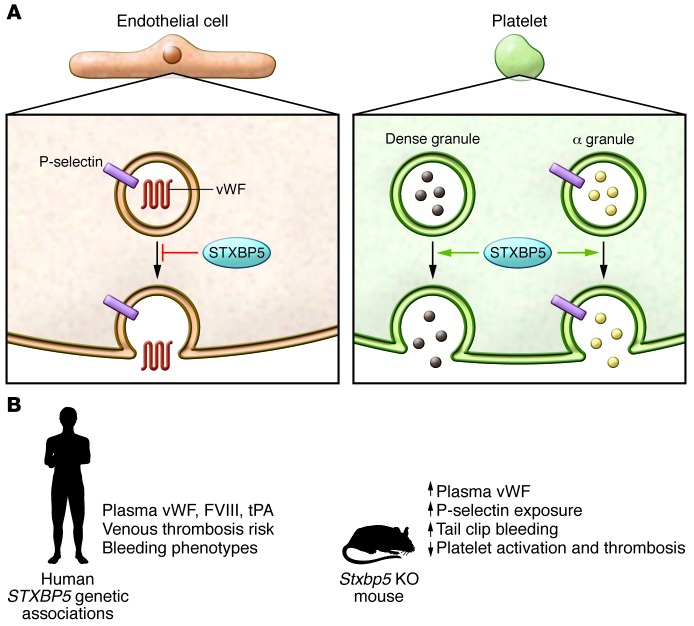

It is not completely understood how the secretory status of platelets and endothelium is regulated. Various agonists are known to promote the secretion of granular contents from platelets (including thrombin, ADP, and collagen; ref. 5) and endothelial cells (such as histamine and shear flow; ref. 6); however, it is not clear how these inducers mediate exocytosis. Two studies in this issue directly address the role of syntaxin-binding protein 5 (STXBP5; also known as Tomosyn-1) in this process. The studies by Ye et al. (7) and Zhu et al. (8) build upon the consistent identification of STXBP5 as a contributor to the regulation of plasma vWF levels (9–11) and as a risk factor for venous thrombosis (12), which suggests that STXBP5 function is important for maintaining normal hemostatic balance (Figure 1). In further support of this notion, a nonsynonymous STXBP5 SNP, N436S, is associated with a decreased incidence of venous thromboembolism (9) and an increased bleeding phenotype in females (13).

Figure 1. STXBP5 differentially influences exocytosis in platelets and endothelial cells.

(A) STXBP5 inhibits regulated exocytosis from endothelial cells, but promotes granule secretion from platelets. In both cell types, STXBP5 interacts with components of the SNARE machinery, but the details of these interactions appear distinct. In endothelial cells, there is no colocalization with WPBs, and the number, size, and morphology of these organelles is not influenced by STXBP5. In platelets, there is no colocalization of STXBP5 with α, dense, and lysosomal granules, but the granule cargo composition is altered. (B) Genetic associations and effects of STXBP5 deficiency. In humans, STXBP5 has consistently been identified in GWAS to be associated with the regulation the plasma levels of several coagulation factors, with bleeding, and with the risk of venous thrombosis. Stxbp5 KO mice exhibit a spectrum of hemostatic phenotypes that are consistent with the role of STXBP5 function in endothelial cells and platelets. FVIII, factor VIII; tPA, tissue plasminogen activator.

STXBP5 expression in endothelium and platelets

STXBP5 is expressed in both endothelial cells and platelets as an approximately 130-kDa protein. Multiple isoforms have been identified that derive from differential splicing of the STXBP5 transcript. Ye et al. and Zhu et al. both report that the pattern of isoform expression appears similar in these two cell types. Ye and colleagues isolated STXBP5 as a t-SNARE–binding protein from platelet extracts (7), whereas Zhu and colleagues identified STXBP5 in endothelial cells through its interaction with syntaxin-4, a component of SNARE complexes, and synaptotagmin, the sensor for mediating calcium-induced exocytosis (8). These findings confirmed prior observations in neurons (14) and pancreatic β cells (15) that STXBP5 can form complexes with SNARE proteins and is thus well situated to regulate the exocytic process. In endothelial cells, STXBP5 was located in cytoplasmic granules, and colocalization with vWF in Weibel-Palade bodies (WPBs) was minimal. Additionally, STXBP5 did not appear to influence WPB number, size, or morphology.

STXBP5 inhibits exocytosis in endothelial cells

In neurons and pancreatic β cells, STXBP5 inhibits neurotransmitter release and insulin secretion, respectively (14, 15). Zhu and colleagues demonstrated that STXBP5 also inhibits exocytosis in endothelial cells (8). STXBP5 knockdown in endothelial cells resulted in increased histamine- and calcium ionophore–mediated secretion of vWF and increased externalization of the adhesion molecule P-selectin. In contrast, STXBP5 knockdown did not affect constitutive vWF release. Interestingly, the N436S STXBP5 variant, which is associated with reduced plasma vWF levels and increased bleeding tendency in females (13), inhibited endothelial vWF secretion more efficiently than did WT STXBP5.

In Stxbp5 KO mice, plasma levels of vWF were increased, consistent with the demonstrated STXBP5-dependent inhibition of endothelial vWF exocytosis. In this Stxbp5 KO mouse model, calcium ionophore–mediated WPB release also resulted in increased platelet adhesion to the walls of venules and increased exposure of P-selectin. Despite these apparent signs of hypercoagulability resulting from uninhibited endothelial exocytosis, tail bleeding was increased in Stxbp5 KO mice. Moreover, Stxbp5 KO mice also exhibited delayed thrombus development after mesenteric and carotid artery injury. These unexpected results suggested that STXBP5 deficiency might induce a platelet function defect.

STXBP5 facilitates exocytosis in platelets

Contrary to the findings in endothelial cells, both groups showed that in platelets, STXBP5 promotes exocytosis (platelet secretion; refs. 7, 8). Both demonstrated reduced release of α and dense granule contents and impaired surface exposure of P-selectin in the absence of STXBP5 (Figure 1). In addition, platelets from Stxbp5 KO mice exhibited a complex granule cargo defect that included reduced levels of some constituents, including platelet factor 4 and factor V, but only modest changes in other proteins, such as fibrinogen and vWF. Numbers of α and dense granules in Stxbp5 KO mice were normal, as were platelet counts.

Both Ye et al. and Zhu et al. observed an increase in tail bleeding and defective thrombus generation in Stxbp5 KO mice (7, 8). To test whether this defect was the result of a platelet-specific influence, bone marrow transplant experiments were performed. Transfer of Stxbp5 KO hematopoietic cells into WT animals resulted in defective hemostasis, whereas transfer of WT hematopoietic cells corrected the hemostatic defect in Stxbp5 KO mice. Together, these results highlight the importance of platelet-specific STXBP5 in mediating granule secretion and generating a normal hemostatic response.

Conclusions

The reports by Ye et al. and Zhu et al. (7, 8) extend previous observations of a genetic association among STXBP5, plasma levels of vWF, and venous thrombosis risk. These two studies revealed that STXBP5 regulates exocytosis from endothelial cells and platelets, but the influence is distinct in these two cell types, with STXBP5 inhibiting endothelial cell exocytosis, but promoting secretion from platelets. Why the difference in effect? STXBP5 transcript variants are similarly expressed in the two cell types; however, the STXBP5 binding partners within SNARE complexes appear to be cell type–specific and may provide clues as to the differential functional outcomes. Overall, these studies demonstrate the power of GWAS to identify previously unrecognized contributors to key cardiovascular functions. Furthermore, these reports highlight the need for additional dissection of the cell-specific functions of STXBP5 to unravel the subtle but critical differences among different cell types.

Acknowledgments

D. Lillicrap is the recipient of a Canada Research Chair in Molecular Hemostasis. Grant support from CIHR (MOP 97849) and NHLBI (HL081588) is acknowledged.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Croce K, Libby P. Intertwining of thrombosis and inflammation in atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14(1):55–61. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200701000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackman N. Triggers, targets and treatments for thrombosis. Nature. 2008;451(7181):914–918. doi: 10.1038/nature06797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jennings LK. Role of platelets in atherothrombosis. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103(3 suppl):4A–10A. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otsuka F, et al. The importance of the endothelium in atherothrombosis and coronary stenting. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9(8):439–453. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flaumenhaft R. Molecular basis of platelet granule secretion. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(7):1152–1160. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000075965.88456.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Mourik JA, Romani de WT, Voorberg J. Biogenesis and exocytosis of Weibel-Palade bodies. Histochem Biol. 2002;117(2):113–122. doi: 10.1007/s00418-001-0368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ye S, et al. Platelet secretion and hemostasis require syntaxin-binding protein STXBP5. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(10):4517–4528. doi: 10.1172/JCI75572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu Q, et al. Syntaxin-binding protein STXBP5 inhibits endothelial exocytosis and promotes platelet secretion. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(10):4503–4516. doi: 10.1172/JCI71245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith NL, et al. Novel associations of multiple genetic loci with plasma levels of factor VII, factor VIII, and von Willebrand factor: The CHARGE (Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genome Epidemiology) Consortium. Circulation. 2010;121(12):1382–1392. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.869156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Loon JE, et al. Effect of genetic variations in syntaxin-binding protein-5 and syntaxin-2 on von Willebrand factor concentration and cardiovascular risk. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3(6):507–512. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.957407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antoni G, et al. Combined analysis of three genome-wide association studies on vWF and FVIII plasma levels. BMC Med Genet. 2011;12(1):102. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-12-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith NL, et al. Genetic variation associated with plasma von Willebrand factor levels and the risk of incident venous thrombosis. Blood. 2011;117(22):6007–6011. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-315473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Loon JE, et al. Effect of genetic variation in STXBP5 and STX2 on von Willebrand factor and bleeding phenotype in type 1 von Willebrand disease patients. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujita Y, et al. Tomosyn: a syntaxin-1-binding protein that forms a novel complex in the neurotransmitter release process. Neuron. 1998;20(5):905–915. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80472-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang W, et al. Tomosyn is expressed in beta-cells and negatively regulates insulin exocytosis. Diabetes. 2006;55(3):574–581. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.03.06.db05-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]