Abstract

Providers and recipients of nursing home care under Medicaid are currently classified into two levels of care to facilitate appropriate placement, care, and reimbursement. The inherent imprecision of the two level system leads to problems of increased cost to Medicaid, lowered quality of care, and inadequate access to care for Medicaid recipients. However, a more refined system is likely to encounter difficulties in carrying out the functions performed by the broad two-level system, including assessment of residents, prescription of needed services, and implementation of service plans. The service type-service intensity classification proposed here can work in combination with a three-part reimbursement rate to encourage more accurate matching of resident needs, services, and Medicaid payment, while avoiding disruption of care.

Introduction

Nursing homes vary widely in the amount and type of care they provide and in their average costs. Residents of long-term care facilities vary in the type and severity of their disabilities and chronic conditions. It is important that public policy recognize these variations across facilities and residents so that residents can be placed where they will receive appropriate care, facilities can be reimbursed according to the type and amount of care they provide, and regulators can set standards that differ appropriately across providers. Classifying both facilities and residents into levels of care is an administratively attractive way to recognize differences among them. Current policy uses two levels of care for three purposes: placing residents, setting Medicaid reimbursement rates, and regulating service delivery.

However, the results of these three regulatory activities are often criticized: Medicaid beneficiaries appear to have inadequate access to care or to be placed inappropriately; public cost is believed to be excessive; and the quality of nursing home care is seen as inadequate. This paper was written in response to a concern that current level of care policy contributes to these problems.

One idea that has emerged as a policy response to nursing home problems is a refined resident classification scheme that would allow facilities to be reimbursed for each resident's care on an individual basis. At the same time, level of care as a facility designation would be abolished, so that nursing homes could serve residents with a broad range of conditions. Increased precision of resident classification under such a system would make placement and reimbursement more exact.

A long-term care task force convened by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (now Health and Human Services) in 1978 considered these issues and recommended consideration of a policy shift away from two levels of care. The Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) asked the University Health Policy Consortium to reconsider these problems later in that year. This paper and the paper by Thomas Willemain that follows it are the result of that request. Rather than look once more at the confusing array of problems apparently related to level of care policy,1 we attempted to carry out a more comprehensive analysis.

The paper begins with a description of current level of care policy and its contributions to problems of cost, quality, and access. The second section reviews the generic tasks that level of care policy is supposed to facilitate (resident assessment, service planning, and service delivery). Then an alternative system distinguishing service types and service intensity is presented. Such a system could more effectively match resident needs to provider services and to reimbursement, thus controlling cost, enhancing quality assurance, and improving access.

Levels of Care: Intentions and Problems

Purposes of Level of Care Classification

The current two-level classification system for residents and services serves three important functions: it identifies each resident as needing either of two types of care, it identifies each provider as able to produce either of the two types of care, and it allows payment to providers to vary according to the service they provide and the residents they serve.

First, Federal regulations mandate that residents cared for under Medicaid programs be divided into two broad level of care groups, with their need for skilled nursing care the major discriminating variable. Residents requiring licensed nursing care because of the nature of their medical conditions are classified as skilled nursing facility (SNF) residents, while those with some nursing needs and personal care needs are classified as intermediate care facility (ICF) residents.

Second, these designations are used to classify and certify facilities in order to monitor the care they provide. Federal regulation for Medicaid providers specifies two levels of care, SNF and ICF, with standards for each level set by States within Federal guidelines. Availability of skilled nursing services in the facility is the major discriminating variable.

Third, levels of care are used not only to classify and certify residents and providers but also to group facilities for rate-setting purposes. Since it is assumed that more complex or input-intensive services, like SNF care, will be provided only at prices higher than those offered for less complex care, rate-setting methods generally recognize that rates should vary by level of care. Some States follow a uniform class rate system, setting a single rate for all SNF and ICF care at a certain percentile of the average cost distribution for that type of care, or at the mean plus a percentage amount. Other States base Medicaid rates on each facility's own average cost, after screening costs for reasonableness based on the cost experience of like facilities. Under both methods, grouping by levels of care allows more complex services to be paid for at higher prices. While variation across facilities is recognized, variation of resident costs within a facility is not: under most systems, care for dissimilar Medicaid residents in the same facility is paid for at the same rate, since each facility is assigned a single rate.

Because a two-level system applied to dissimilar residents and diverse providers is inherently unable to reflect all relevant variations, there is growing interest in developing a system that would make finer distinctions. A number of problems with costs, quality assurance, and access to care for high-need Medicaid residents can be traced to current level of care policy. It is important to consider these problems in light of the functions served by level of care classification so that we may understand how a change in policy might be expected to ameliorate them.

Problems of Cost to Medicaid Budgets

Cost problems attributable to using two levels of care arise in two instances: when individuals who should receive ICF care are “overplaced” in SNFs and when residents at either level of care are less costly to care for than average. The magnitude of the overplacement problem has been variously estimated at 10 to 40 percent of SNF residents (Congressional Budget Office, 1977). The range of these estimates makes the extent of the problem unclear, as does the fact that judgments of misplacement are highly influenced by context (Allison-Cook and Thornberry, 1977). Still, some funds are certainly being expended for inappropriately intensive services in SNFs. In theory, the overplacement problem could be reduced by more careful initial placement and by judicious resident transfer, but transfer is disruptive and there will always be “borderline” cases to confound classification.

The more subtle cost problem of variation in resident mix among facilities at the same level of care is more directly attributable to the inherent imprecision of a two-level classification system. Any system of grouping residents and paying an average rate for an average “care bundle” can lead to overpayment for those needing less than the average care intensity. If facilities cared for an average mix of residents, such fine distinctions would be of no concern; the facility would be paid an average rate and would provide more than average care intensity to some residents and less to others. However, residents are not admitted and discharged as a group, but one by one. If a nursing home operator has a pool of potential residents from which to choose, he is likely to select those whose care is less costly. Thus, there are forces in the system that increase the discrepancy between the rate paid to a facility and the value of the services provided to its residents. In theory, neither cost problem will occur where rates respond to individual facility costs and costs respond to resident characteristics. Under rate-setting systems based on expended cost, variation among facilities in services provided is presumably recognized through full reimbursement of the varying cost of services. If services (and costs) adjust to resident mix, SNFs serving misclassified ICF residents would be paid only the lower cost of ICF care. SNFs or ICFs serving residents who are appropriately placed but less costly than average would again be paid for the lesser care they provide. Since in many States public rates are based on expended cost, subject only to group ceilings, the significance of the cost problem due to level of care policy per se might be questioned.

However, even in States where rates respond to actual facility costs, three effects can lead to excessive public expenditures for care. First, the facility may not be able to alter certain costly fixed resources in response to resident mix. For example, if it is designated as an SNF, a facility must still provide 24-hour licensed nursing supervision and certain other services. Second, a facility may choose not to reduce variable inputs into care when its case mix becomes less difficult. It may be staffed and equipped to provide a certain style and intensity of care and may choose to continue doing so. Third, under cost-related prospective systems, rates respond to expended cost only with a lag; thus an operator may profit from serving relatively light-care residents while being paid at a rate reflecting the cost of his previous heavy-care mix.

Problems of Quality

Quality suffers when residents receive too few services in relation to their conditions. As with the cost problem, it appears that the incentives of providers under an imprecise two-level classification system tend to encourage “underservice,” especially in facilities largely dependent on Medicaid. (Under-service may also arise when public programs fail to enforce standards for care, when Medicaid payment is too low to support standards, or when standards are low.)

Imprecise level of care distinctions can lead to underservice in the following manner. Assume that the standards for each level are set on the basis of the average resident classified in that level and that only the average required services are paid for. A facility which actually has a Medicaid case-mix requiring care of above-average intensity is nevertheless only expected to provide care of average intensity. This implies that residents may not receive appropriate services even in a facility where input standards are satisfied and residents are correctly classified.

Clearly, such underservice to heavy-care residents does not always occur; many facilities provide more than minimum input levels when their case-mix is needier than average. However, level of care policy may still be held responsible for some underservice to patients, since one cannot expect nursing home operators to purchase in excess of the minimum care inputs for their designated level unless there is a return to them.

The basic problem in regulating care inputs is that a system with only two sets of standards for care cannot respond well to variation in resident mix. Thus, standards applied to a SNF or an ICF serving a relatively heavy case-mix are no different in many States from the standards applied to SNFs or ICFs serving a relatively light mix. A system that required facilities serving more difficult residents to meet higher standards and compensated them accordingly might more effectively ensure quality of care.2

Problems of Access

The imprecision of two levels of care also impedes the access of Medicaid beneficiaries to care. When a rate is assigned to each facility and responds slowly, if at all, to resident mix, the cost of caring properly for a Medicaid resident with above-average needs is not fully reimbursed. Providers are unlikely to welcome heavy-care Medicaid residents under such circumstances. Reimbursement which is insensitive to cost variations within levels of care thus creates incentives that reduce access for the more disabled Medicaid residents within each level. If these people must wait in hospitals for admission to nursing homes, the cost to the public budget is high; if they wait at home, their quality of life may be seriously affected.

If all the additional costs of heavy-care residents were immediately reimbursed by public programs, providers should in theory be equally willing to admit any applicant. However, the following realities must be considered:

Some residents appear to put strains on the care delivery system beyond dollar costs. The stress placed upon staff and other residents by those with behavioral problems or highly unstable medical conditions is difficult to compensate through increased expenditure. The result is that providers will try to avoid such individuals.

Most reimbursement systems do not compensate immediately for the increased dollar cost of heavy-care residents, leading to cash-flow problems for providers. Retrospective cost-based systems reimburse costs after they are incurred, and full reimbursement may not be made for several years. Cost-based prospective rates also adjust to increased costs only with a lag. It is not surprising that providers try to keep costs at or below interim or prospective rates under such systems and are therefore not anxious to admit or provide additional care for heavier care residents.

Finally, under many reimbursement systems, costs are disallowed if they exceed certain ceilings for any reason. Thus a facility with high costs due to a heavy-care resident mix would be penalized in the same way as a facility providing overly intensive or inefficient services to a light-care mix. Providers understandably avoid exceeding cost ceilings by avoiding heavy-care residents.

The Level of Care Problem

While the problems attributed to level of care policy all stem from the inherent imprecision of using two broad levels to classify facilities and residents, the problems take different forms under different circumstances. For example, a State Medicaid program that enforces high input standards for each level is less likely to experience problems of underservice to more disabled residents, but may have access and cost problems. A program offering relatively generous rates for each level is less likely to encounter access problems, but budget control may suffer as a result. Rates that tighten control over Medicaid nursing home expenditures may encourage underservice to relatively needy residents at each level and impede access. It is therefore not surprising that policymakers identify different problems as “the” level of care problem and propose different solutions. However, a basic reform could address the fundamental issue of the imprecision of two levels for resident classification, facility regulation, and reimbursement. By delineating the functions of level of care classification, we can consider alternatives to current level of care policy.

Functions of Level of Care Classification

Any level of care policy has the function of matching residents with appropriate services. Its effectiveness in doing this depends on the successful execution of three basic tasks:

Resident Assessment—Residents' conditions must be accurately assessed.

Service Planning—A determination must be made about what types and quantities of care are to be provided to residents with specific characteristics; standards must be set for care.

Service Delivery—The service plan must be implemented through proper placement, rate incentives, and monitoring of facilities.

In this section, we consider problems involved in carrying out each of these tasks.

Resident Assessment: Uses and Difficulties

Assessment of resident status provides the basis for determining which services to authorize. Assessment is therefore critical for placement decisions, service planning, utilization and quality review, and appropriate reimbursement. However, assessment methods must confront several conceptual and operational difficulties that are critical to the choice of a new policy for resident classification.

Various methods of assessment have been developed, ranging from highly complex, theoretical approaches aimed at operationally defining health and functional status with an elaborate survey instrument to “quick and dirty” evaluations that are sketchy but easy to use.3 None is entirely satisfactory for the purposes at hand.

The description of chronic disease and disability in an elderly, institutionalized population presents a difficult problem. The characterization of multisystem chronic illness in the elderly (strokes, sensory-motor diseases, senile dementia, and so on) is not easily accomplished using clinical criteria. Even more difficult to characterize are the functional and psycho-social disabilities of the elderly. It is a formidable task to develop an instrument to assess the combined effects of chronic illness and disability in a population in which there is high variability among individuals compounded by high individual variation over time.

First consider the uncertainty of assessments of health status at one particular time and the relationship of health status to disability. There are no clear-cut clinical indications to assess the health status associated with stable chronic illness. Typically, indications for medical care and supervision depend also on the expected future course of illness, but little epidemiological information is available to predict the natural history of chronic illness. To compound the problem, most nursing home residents have two or more serious chronic illnesses (Bright, 1966), which may have interacting effects on health status and medical need. Worse, this diversity in medical need given disease conditions is only part of the picture; needs are also determined by disability level. Since individuals with similar diagnoses are known to experience widely differing disabilities, a simple tally of disease conditions will not provide a clinically useful patient description.

The variability in the health status of elderly nursing home residents over time creates further problems. Even those suffering from the same illness quite often vary substantially in their clinical course. Disabling conditions also change over time, affected by the course of a chronic illness, by aging, and by rehabilitation efforts. Studies of long-term care populations have attempted to evaluate this variability focusing on functional status, measured primarily by the Katz Index of the Activities of Daily Living, (Katz et al, 1972; Densen et al, 1976; Plough, 1977). Densen et al found a high degree of variability of patient status over time, raising the question of the appropriate time interval between assessments.

Another practical issue that affects the accuracy both of initial assessment and assessment over time is the dependence of most assessment systems on medical records kept by nursing homes. When the quality of the recordkeeping is low (incomplete records, missing entries, recording errors, and so on) the data abstracted by the assessment instrument will not be valid. Individual resident information must be used more intensively in any system that makes fine distinctions for purposes of placement, service planning, and reimbursement. Inaccuracy of recorded medical and psycho-social data would be an important obstacle to the implementation of more “patient-centered” or individualized systems.

To be superior to the current system, a new level of care policy must allow classification of residents in a way that better reflects relevant variation in their conditions and disabilities, while confronting practical problems of assessment cost and timing. Whatever bias and unreliability exist in patient assessment will critically limit-the implementation of more refined classification schemes.

Service Planning: Linking Resident Assessment to Service Needs

If residents were assessed more finely, service planning could conceivably be fine-tuned to match. Standards for providers could then deter over-service to those with light-care needs and help assure that heavy-care residents receive adequate attention. Yet, translating resident characteristics into prescriptions for appropriate services is not straightforward.

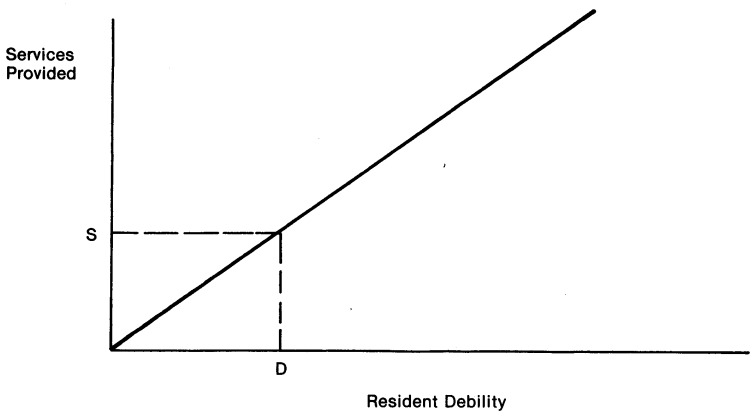

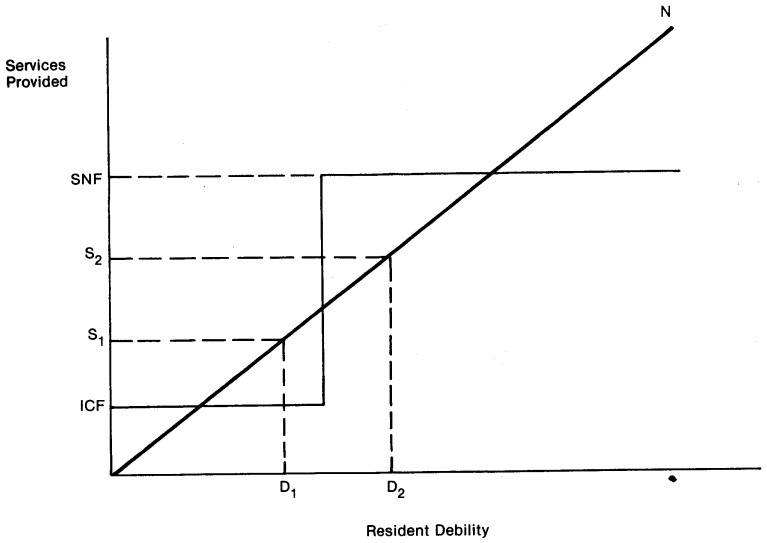

One assumption of level of care policy is that each resident has a measurable “need” for care and can be appropriately placed so that the “right” amount of care is provided. It may be useful to display this idea graphically, since it underlies much of the discussion about levels of care. In Figure 1, a debility-need line shows the amount of service presumably required for each level of debility. For instance, a resident with debility level D would need a level of services equal to S. Using this approach, the quality and cost problems of the current level of care policy are summarized graphically in Figure 2. Need for services given resident status is again indicated by the line, but services provided are at two levels only, SNF and ICF. A resident with debility level D1 is seen in need of service level S1 but only receives ICF care. This resident receives less care than needed, so the quality of care is below the standard represented by the straight line. In contrast, a resident with debility D2 needs service level S2 but receives SNF care, a level higher than S2. The second resident receives more care than needed, meaning that care resources are being wasted and dependencies may be fostered.

Figure 1. Presumed Ideal Relationship Between Debility and Services.

Figure 2. Distortions Introduced By Two Levels Of Care.

Improving the match between resident condition and service provided is central to the design of a new level of care policy. However, it is much more difficult to assign care resources than implied in Figures 1 and 2. Most important is determining what services are to be authorized by public programs as a function of resident condition. We would stress that, although this resource allocation involves technical information, it is fundamentally dependent on policy decisions that are difficult to make explicitly: What is “need” for care? How much care is enough?

Problems With Defining “Need”

It is critically important to recognize that there is technically no “correct” set of services to be provided to an individual with a given set of conditions and disabilities. The conventional wisdom, as expressed in the debility-need line of Figures 1 and 2, holds that services should be related to resident characteristics, but no clear norms relating resident characteristics to service needs have emerged from statistical or judgmental studies. Professionals, providers, and regulators disagree among themselves about what similar residents should receive, and studies of provider behavior indicate variations in what similar residents actually do receive.

First, professionals have not arrived at clear standards for needed services. For example, a study by Sager (1979) comparing the costs of home and institutional care documented large variations among long-term care professionals in their assessment of care needs. Patients being discharged to nursing homes from hospitals were each evaluated by 18 professionals, and hypothetical home care plans developed. These care plans revealed major differences, both within and across professions, especially at the level of the individual client.

Second, best-practice providers apparently follow different rules for prescribing services to residents. In search of a common link between resident status and care inputs, McCaffree, Winn, and Bennett (1976) recorded staff contact time with each patient in facilities identified by State regulators and industry as “effective and efficient.” When staff time was related to a 192 item description of each resident, 50 to 70 percent of the variation in aide/orderly time within each nursing home was explained. This implies that facilities do to some extent allocate care resources on the basis of resident characteristics. However, pooled analysis of care provided to residents in all 12 facilities failed to reveal agreement about how much aide/orderly time should be spent with residents having certain debilities and diagnoses, suggesting large differences across facilities. Thus it appears that an absolute standard of need for care, given patient characteristics, is not widely applied.

Third, the standards for care for SNF and ICF residents differ widely across States (National Geriatrics Society, 1976; Holmes et al, 1976). Medicaid policymakers have clearly not reached a consensus about the needs of various types of patients.

Finally, studies of the determinants of nursing home costs indicate a similar lack of consensus across providers about the amount of care to be supplied to residents with certain conditions and disabilities. Researchers have used statistical analysis of the relationship between operating cost per patient day and resident characteristics to reveal whether providers tend to purchase more care resources for certain types of residents. However, case-mix has not performed well as a predictor of cost in most cost analyses.4 While there are problems with measuring case-mix for such analyses, this indicates that providers respond differently to residents with similar characteristics.

In sum, there appears to be significant disagreement among providers, professionals, and States about how staff and other care inputs should respond to variations in resident characteristics. Some of this disagreement may be due to lack of knowledge, since there are no clinical studies that assess the effect of various care resources on residents of various types. Such studies could focus on care outcomes, including resident satisfaction and quality of life, as well as morbidity and mortality. They could also add substance to the discussion of the value of recreational therapy, registered nursing supervisors, psychological counseling, and personal care in keeping patients functioning at their highest potential level.

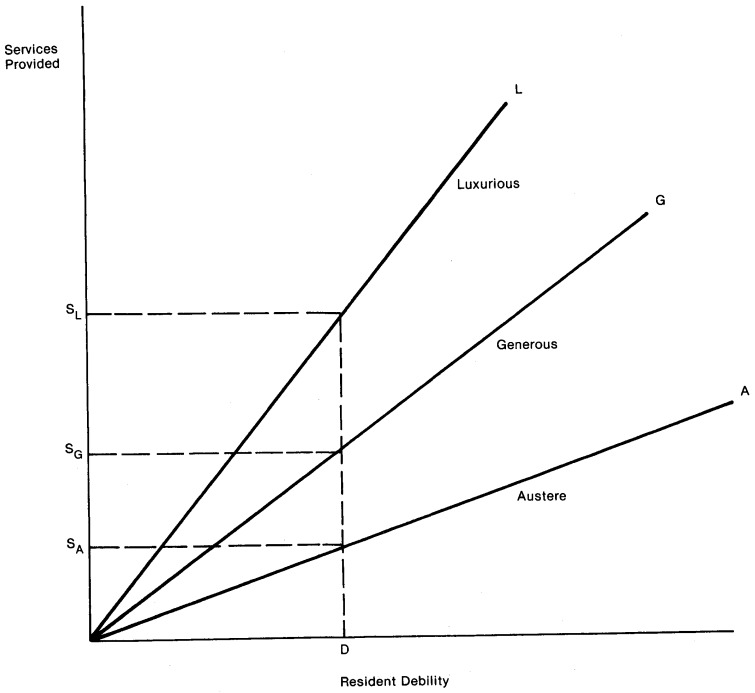

The Value of Imprecise Standards

Even if certain care inputs benefit certain types of residents, choices may still be open about the level of service to be provided. Extending the oversimplified presentation of Figure 1, we show public programs in Figure 3 as choosing either to meet needs in an austere fashion, as along line A, to meet needs more generously, as along line G, or to provide “luxury” care including everything that a wealthy private patient might buy and everything professionals recommend, as along line L Under these three rules of need determination, a resident with debility level D would be deemed to need either service level SA, SG, or SL. The choice among service levels will be made based on choices about the quality of life and health care to be purchased for Medicaid beneficiaries and the adequacy of public funds. Currently, public choice of care inputs appropriate for different resident conditions is made only in a general way, by using, broad resident categories and setting minimum care inputs based on average needs for each category. Increased precision in matching resources to resident condition would highlight the compromise between high care standards and cost containment. A more refined system would have to confront the technical and political problems of specifying care needs by precisely defined resident type.

Figure 3. Illustrating Three Different Approaches To Relating Debility to Services.

Service Delivery: Implementing Service Plans

Once residents' needs are accurately assessed and translated into care plans, it is necessary to ensure that the plans are carried out so that residents receive needed care and public programs do not pay for excess care. Residents must be placed in facilities that have the capacity to deliver the services; then the providers must respond to individuals' needs, and to changing needs over time, by adjusting the care resources provided to each resident. Assuring the appropriateness of placement, both initially and over time, is the task of preadmission screening and utilization review activities, while licensure and certification inspection assure that care meets specified standards. In addition, reimbursement methods play an indirect but important role in determining whether placement and ongoing service delivery are appropriate to resident needs.

Certification and licensure inspections and placement review organized around two levels of care assure, at least in a general way, that Medicaid patients receive the services they are determined to need. Reimbursement by level of care makes appropriate service delivery possible by allowing higher rates for the more expensive service type.

Any alternative to current level of care policy must also ensure that appropriate services are actually provided to residents, in other words, that service plans are implemented. A more precise classification system for residents and services might facilitate a better match between conditions and care, but we can foresee problems in carrying out this more precise matching. First, identifying facilities as able to provide only a precisely defined type of care would enable more accurate initial placement, but would also cause more frictional vacancies as the mix of new residents changed. For example, beds for stroke victims might be empty in one month while residents with other conditions had to wait for initial placement; next month, a different “mismatch” of supply and need might occur. A more refined approach to facility classification might also imply that not all types of care could be offered in each locality, so that more beneficiaries would have to leave their home areas to find appropriate placement. Appropriateness of placement over time might become more elusive, since changing resident needs would be hard to satisfy in a facility offering only a precisely defined type of care; more frequent transfers among facilities would be detrimental to residents, as well as costly to Medicaid programs. In the extreme, an individualized system, in an attempt to achieve a near-perfect match between residents and services, could require very frequent resident assessment and day-to-day monitoring of the services a particular resident actually receives; the administrative cost of such a system is likely to exceed any gain in program effectiveness.

To focus discussion of these issues, we now consider a proposal for a more refined level of care system that attempts to address these problems while working for efficiency in provision of care, appropriate matching of services to needs, and access of high-need Medicaid recipients.

A Service Type—Service Intensity Level of Care System

A new system for classifying residents and facilities might better focus placement decisions on the match between resident need and the capacity of facilities to meet needs by designating facilities as capable of providing particular “service clusters.” Under such a system, one component of a facility's licensure standards and of its rate would depend on its service cluster designation. At the same time, facilities would be encouraged to accept and care for heavy-care residents through a rate component that varied with intensity of need for nursing and personal care; a parallel component of the standards applied to a particular facility would depend on the nursing and other variable care needs of its current resident mix. A facility's rate would also include a component reflecting unavoidable cost differences across facilities that are due to features only indirectly related to resident care (such as age of physical plant).

Since the proposed system highlights the difference between fixed service capability and the intensity of variable services actually provided, this distinction is discussed first.

Distinguishing Needs for Fixed and Variable Resources

A better match between residents and providers could be facilitated by a classification system for residents and facilities based on fixed and variable care resources. Residents differ along many dimensions of need. Some of these needs are for variable amounts of care resources, for example, hours of nursing and personal care per day. But other needs are for particular types of service, like physical therapy, diet planning, and medical supervision, that are most efficiently provided to many residents with similar needs. When prospective residents differ significantly by type of service needed, the matching of residents with care must take place through appropriate placement in facilities with these relatively fixed care resources. Facilities should thus be classified according to the specialized cluster of services they are prepared to provide, and residents should be identified according to the specific types of services they need.

The variation in the type of care that residents need has entered previous discussions of levels of care in proposals to designate facilities as either “comprehensive” or “specialized.” The comprehensive facilities would be capable of providing all types of care, while the specialized facilities would care for certain types of residents only. In most areas, facilities could target their services to various segments of the population. This specialization in providing a set of services could increase efficiency, while comprehensive facilities could serve residents whose needs were expected to change or residents in areas that could not support an array of facility types.

While the concept of comprehensive and specialized facilities is a useful one, it alone cannot replace current level of care policy, since it focuses on types of services only. Once in a facility that can provide the needed types of service, a resident must also receive the appropriate amount of care. The intensity of nursing and personal care can be varied in response to changing resident mix, and should be paid for and monitored for appropriateness.

The relative importance of variation in both type and amount of services for describing resident needs and for efficiency in the provision of care should be investigated empirically, since it has major implications for level of care policy. If residents differ mainly in the amount of service they need, then most facilities should be comprehensive; regulation should then revolve around the differences in the intensity of care required by different residents and reimbursement should be geared toward the individual resident. On the other hand, if residents differ mainly in the type of services they require, then most facilities should specialize in the provision of a particular service cluster, and regulation and reimbursement should focus on characteristics of facilities, appropriateness of placement, and facility-oriented payment. The truth probably lies in between, so that reimbursement and regulation should consider differences in both type and intensity of care.

Operationally, the first challenge would be to define a manageable number of service clusters that reflect real differences in the types of service that residents need. While the classification of facilities as providing perhaps 10 or 12 service clusters would be more complex than the current SNF/ICF distinction, it would be an honest recognition of the fact that the presence of and need for skilled nursing is not the sole basis for distinguishing nursing homes and residents. The second task would be to specify the variable services to be supplied to residents with differing needs, so that facilities could be required to provide the staff resources to meet resident need, and would be paid appropriately for these variable inputs.

“Split-Rate” Reimbursement for Fixed and Variable Care Resources

The distinction between types and amounts of needed services has a counterpart in the fixed and variable costs of service provision. Some costs (like nursing hours) can respond to a facility's case-mix, allowing rather continuous variation. Other costs, supporting the provision of fixed resources available to all patients, depend more on the type than the amount of resident needs. Still other ongoing costs, like financing and energy costs, depend less on resident needs than on facility characteristics such as type and age of construction.

We propose a “split-rate” approach to rate-setting that recognizes these three types of costs in different ways. Consider first the cost of maintaining a specific service cluster. Specialized shared services, like physical therapy and diet planning, continue to add to overhead cost whether or not residents are actually using them. If Medicaid wishes these capacities to be available to beneficiaries placed in the home, the rate must include their overhead costs. Second, the cost of providing the nursing and personal care hours to meet residents' individual needs must be reimbursed appropriately; Medicaid must pay more for needier residents, or it will be unable to assure that they can be placed and served appropriately.

Reimbursement of facility-specific costs not directly associated with care requires more consideration. Some facilities will have high overhead costs, while other facilities can provide similar care for less. For example, a facility with electric heat, an outmoded physical plant, or costly financing will have higher average costs. In private competitive markets, costly mistakes or bad luck in capital investment decisions are not tolerated; an all-electric hotel would necessarily have lower profit, all else the same, than the hotel with more foresighted management that heats with gas. However, while some economists may not agree, many long-term care planners apparently believe that such market discipline should not be allowed to work in the nursing home market because of the disruption that would occur if high cost homes went out of business. For this reason, some rate-setting methods group facilities by characteristics which providers cannot easily change, like size and ownership, and pay higher rates to groups of facilities with higher costs. In addition, many rate-setting systems use full cost reimbursement methods for depreciation and interest expenses (up to ceilings), so that older facilities with lower construction and financing costs receive lower rates than newer facilities providing the same service. Although it may work against long-run efficiency, reimbursement of the cost of characteristics that providers cannot change supports industry stability by keeping higher cost facilities in business, and prevents what might be seen as windfall gains to lower cost facilities.

A three-part rate could pay for service intensity, for the capacity to provide certain types of service, and for ongoing overhead. Part of the rate would be based on the intensity of care needed by the facility's case-mix; a second part would cover the average fixed cost of the cluster of services shared across all residents; and a third component would vary with unavoidable overhead expenses due to facility characteristics.

Assuring that Care is Delivered

After assessment, service planning, and admission to a nursing home, the resident must actually receive the needed care. Monitoring care delivery under the proposed split rate system is especially important, since providers would be paid more for needier residents, and they should not profit from under-service to residents.5

Three approaches could be used to ensure delivery of appropriate care. First, process-oriented review might be used to verify service delivery. An outcome approach is a second option.6 Third, inputs might be monitored directly, as under current licensure and certification, but input standards for each facility could be tied to the disabilities and conditions of its actual patient census. This could be done by monitoring the care inputs actually received by each Medicaid beneficiary, but a case-mix approach to input standards would probably be more effective.

This third option would be viable if regulators could trust each provider to allocate services according to need within a facility. Evidence of such behavior is provided by McCaffree, Winn, and Bennett (1976), who found that services provided in “best practice” facilities were to some extent allocated across residents according to variation in condition. This implies that resource endowment for a facility as a whole might be assessed in relation to total case-mix to determine if needs are being appropriately met. (Private-pay residents must be included in such case-mix measures, because similar Medicaid residents in facilities with equal services may receive different care if the private-pay residents in one home are very much more disabled than in another.) More exploration of the way providers allocate services among residents is necessary before input standards adjusted for case-mix can accompany a similarly adjusted rate,7 but the approach has potential.

Contrast With Alternative Systems

It is interesting to contrast this service type-service intensity approach with proposals for fully individualized (or “patient-centered”) levels under a patient-centered rate. Medicaid residents would be assigned individual “price tags” based on their condition upon admission to a nursing home. The rate paid for a given resident would be the same no matter where he or she was placed. This pricing method would make the market for nursing home services similar to some other markets in our economy, in that the purchaser (Medicaid) would specify what it wants to buy and how much it is willing to pay for the service. A nursing home owner who can provide the care for less would admit the resident and make a profit; a provider whose costs are greater than the “price tag” will not offer care.8 Assuming that the care delivered could be monitored to ensure that purchased services are actually delivered, such a system would make provision of care more efficient, since specified care would eventually be provided in appropriately specialized facilities at least cost. Inefficient high cost providers, or those who choose to provide unnecessarily complex or luxurious care, would leave the public care market.

In contrast, the facility components of the split rate would pay for overhead costs of patient care and ongoing facility related expenditures and thus may not promote efficiency as actively as a fully patient-centered rate. Nevertheless, a rate-setting system that recognizes the ongoing, unavoidable costs of providing needed service yields valuable continuity. A fully patient-centered rate would be less effective in sparse market areas that could not support many specialized facilities, because many individuals would have to leave their communities to find appropriate nursing home care. It would also tend to drive inefficient facilities out of business, causing disruption of patient care.

Comparison of the service type-service intensity system to the current system is also instructive. Current level of care policy distinguishes two types of service, and residents are seen as needing one of only two types of care. Properly classified SNF residents in facilities that meet SNF standards receive more variable services and different fixed services from ICF residents, and SNF providers are reimbursed at a higher rate. However, providers are not required to provide a higher intensity of services to residents, whether SNF or ICF, who need more of the variable services, such as nursing hours, than licensure and certification minimums require. If appropriate services above minimum requirements are supplied, providers risk financial losses, since facilities providing appropriately complex services to heavy-care residents may be penalized by rate ceilings based on average costs. The associated rate-setting systems miss some opportunities to encourage efficiency, since costs that fall below ceilings tend to be reimbursed even if they are excessive in relation to resident need. Potentially efficient specialization is consequently not encouraged.

Summary and Conclusions

This paper has indicated how the imprecision of a two-level system can lead to excess cost, inadequate quality, and insufficient access for high-need Medicaid beneficiaries. Any alternative to current level of care policy must perform the same functions, assisting in assessing residents, prescribing the services they need, and implementing appropriate service plans. As discussed earlier, a more precise level of care policy will encounter difficulties in making each of these functions more exact, so a recommendation to replace the broad two-level system cannot be made lightly. The alternative policy suggested here reflects more of the variation in resident need and facility services so that placement, reimbursement, and regulation of services can work for a more accurate match between resident needs, services provided, and payment by Medicaid programs. Some aspects of the service cluster-service intensity approaches to level of care are simulated in a companion paper in this Review (Willemain, 1980). Further simulations and experiments should explore the implications for cost control, quality of care, and access to services of this and other alternative policies.

Acknowledgments

A number of individuals have contributed to the development of this paper and its companion piece, “Nursing Home Levels of Care: Reimbursement of Resident-Specific Costs” by Thomas R. Willemain, Ph.D. Diane Rowland, Judith Williams, and Wilhelmine Miller helped to frame the initial questions posed here. They and other Health Care Financing Administration staff members provided helpful comments and suggestions, as did our colleagues at the University Health Policy Consortium, especially Stanley Wallack, Leonard Gruenberg, Dennis Beatrice, and James Callahan. Participants in the UHPC review process, including Ann MacEachron, Deborah Stone, and long-term care professionals from Massachusetts State government, also commented on earlier drafts. Barbara Skydell, Katherine Raskin, Natalie Andrews, and Mary Smith supplied editorial and technical assistance. We are grateful to them all.

Footnotes

In 1978, the University Health Policy Consortium (UHPC), composed of Boston University, Brandeis University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, established the Center for Health Policy Analysis and Research for the purpose of conducting relevant health policy analysis and short-term research projects for the Health Care Financing Administration.

This Major Issue Paper was prepared by the University Health Policy Consortium as part of Grant #18-97038/1-02 for the Health Care Financing Administration, Department of Health and Human Services.

These are well documented in Vladeck (1980), especially Chapter 6

Some States' regulations specify that care shall be “appropriate to patient mix” rather than specifying a particular minimum ratio of nursing staff to patients. Such regulations, if enforceable, could respond to variations in case-mix and solve the problem of heterogeneous need within a two-level system of providers.

See Stewart et al (1978) and Plough and Rosenfeld (1980) for review and evaluation of assessment methods.

See Bishop, 1980, for a review of nursing home cost studies.

A related concern is that a more patient-oriented system paying higher rates for more dependent patients may involve incentives to keep patients dependent. (See, for example, Kane and Kane, 1978.) Such incentives are diminished insofar as facilities are required to meet patient needs.

However, the suggestion that outcome incentives replace the bulk of input and process approaches to quality assurance appears to be misguided for several reasons: the anticipated market response would probably not occur, the most vulnerable would be at a disadvantage in the “futures market” for nursing home residents, and the normative, political, and technical problems of implementation would be formidable (Willemain, 1979). Outcome information might well be used in other ways, however, with less direct and detailed linkages to reimbursement.

Specifically, it is important to find out whether the distribution of resources by need found by McCaffree et al is common to all nursing homes, as well as “best practice” homes. It is also important that allocation of services within a facility is not affected by source of payment.

A theoretically appealing extension is that beneficiaries' conditions could be evaluated, and they could be given vouchers good for long-term care services. The face value of the vouchers would depend on their conditions and perhaps their income. They could then seek the mix of services, in an institution, sheltered living situation, or their own homes, that best meets their own self-evaluated needs and tastes. This would lead to maximum consumer satisfaction. (See Gruenberg and Pillemer, 1980)

References

- Allison-Cook S, Thornberry H. Factors Affecting Nursing Home Medical Review. Medical Care. 1977 Jun;15(No. 6):494–504. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197706000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop CE. Nursing Home Cost Studies and Reimbursement Issues. Health Care Financing Review. 1980 Spring;1(No. 3):47–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bright M. Demographic Background for Programing for Chronic Diseases in the United States. In: Lilienfeld Abraham, Gifford Alice J., editors. Chronic Diseases and Public Health. John Hopkins Press; Baltimore, Maryland: 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office. Budget Issue Paper Appendix B. Washington: Congressional Budget Office; 1977. Long-Term Care for the Elderly and Disabled. [Google Scholar]

- Densen P, Jones E, McNitt B. An Approach to the Assessment of Long-Term Care. Final Report, DHEW Research Grant HS-01162. 1976 Dec 13; [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg L, Pillemer K. Disability Allowance for Long-Term Care. In: Wallack Stanley, Callahan James., Jr, editors. Reforming the Long-Term Care System: Financial and Organizational Options. Lexington, Massachusetts: Lexington Books; 1980. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes D, Hudson E, Steinbach L, Zitin D. A National Study of Levels of Care in Intermediate Care Facilities (ICF's) Final Report, DHEW Contract No HSA-105-74-176. 1976 Apr; [Google Scholar]

- Kane R, Kane R. Care of the Aged: Old Problems in Need of New Solutions. Science. 1978;200:913–919. doi: 10.1126/science.417403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford A, Downs T, Rusby D. National Center for Health Services Research. Washington: Government Printing Office; 1972. Effect of Continued Care: A Study of Chronic Illness in the Home. [Google Scholar]

- McCaffree, Winn KS, Bennett C. Final Report, Grant Nos HS 0114-01A1 and HS 0115-01A1. Battelle Human Affairs Research Center; Oct 1, 1976. Cost Data Reporting System for Nursing Home Care. [Google Scholar]

- National Geriatrics Society. Survey of Nursing Care Requirements in Nursing Homes in the States of the Union. 1976 Apr; Update to. [Google Scholar]

- Plough A. Co-morbidity and Causes of Death in a Population of End-Stage Renal Disease Patients. Veterans Administration Health Services Research Program; West Haven, Connecticut: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Plough A, Rosenfeld A. University Health Policy Consortium, Discussion Paper DP-18. 1980. Quality Assurance and Long-Term Care Policy: Expanding the Institutional Perspective. [Google Scholar]

- Sager A. Learning the Home Care Needs of the Elderly: Patient, Family, and Professional Views of an Alternative to Institutionalization. Levinson Policy Institute, Brandeis University; Nov, 1979. Estimating the Costs of Diverting Patients from Nursing Homes to Home Care. Final Report to U.S. Administration on Aging, AOA Grant No. 90-A-1026. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A, Ware J, Brook R, Davies-Avery A. Conceptualization and Measurement of Health for Adults in the Health Insurance Study: Vol. II, Physical Health in Terms of Functioning. Prepared under a grant from the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. 1978 Jul; R-1987/2-HEW. [Google Scholar]

- Vladeck B. Unloving Care. New York: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Willemain T. Nursing Home Levels of Care: Reimbursement of Resident-Specific Costs. Health Care Financing Review. 1980 Fall;:47–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemain T. University Health Policy Consortium Discussion Paper DP-15. Aug, 1979. Second Thoughts About Outcome Incentives for Nursing Homes. [Google Scholar]