Abstract

This paper examines use of physicians' services by Medicare beneficiaries according to the specialty of the physician providing care. The major objectives of this study were to determine which types of physicians are most frequently used, the average charge per service by specialty, the mix of physicians (by specialty) that patients saw during the year, and the amount Medicare reimburses in relation to total physician income. Data were studied for the total Medicare population and by age, sex, race, and geographic area.

Claims data for 1975 and 1977 were used from the Part B Bill Summary System. This system collects information from bills for a 5 percent sample of Medicare enrollees.

Major findings from this study indicate: (1) Physicians in general practice and internal medicine provided about the same number of services and each far outranked all other types of physicians in numbers of Medicare beneficiaries with reimbursed services. (2) There were marked differences by census region in the use of certain specialists, particularly pathologists, podiatrists, dermatologists, and the specialty group otology, laryngology, rhinology. (3) Average charges per service varied considerably by specialty. Internists' charges averaged 35 percent higher per service than charges by general practitioners. Charges submitted by the surgical specialties far outranked all others and showed the greatest increase during the period under study. (4) Of the total persons with reimbursed physicians' services in 1977, 85 percent saw a primary care physician during the year, while the remaining 15 percent received services from specialists only. (5) Of the total reimbursements made by Medicare, internists received 20 percent, general practitioners received 14 percent, and general surgeons 12 percent. Medicare's payments were estimated to be 21 percent of total gross income for internists, 20 percent for anesthesiologists, and 18 percent for surgical specialties.

Introduction

Knowledge about the specialty of physicians providing services is important in gaining a greater understanding of the complex health care delivery system in the United States. This paper is the third in a series using data from the Medicare claims payment system to study physician use in the Medicare program. Medicare's payment mechanism requires that each physician (or supplier of service) be identified by specialty. Thus, claims data can be examined by the types of physicians being reimbursed under the program and the proportion of beneficiaries who use any type of physician's care. This paper focuses on the most frequently used types of providers: general practice, family practice; internal medicine; cardiovascular disease; dermatology; general surgery; otology, laryngology, rhinology; ophthalmology; orthopedic surgery; urology; anesthesiology; pathology; radiology; chiropractic; podiatry; and multi-specialty group.

The paper first provides a descriptive account of the number of persons reimbursed for physicians' care, the number of services they received, and the reimbursements made in 1975 and 1977, according to the specialty of the physician providing care. The data are also analyzed by age, sex, race, and census region of the beneficiaries to determine how specialty use varies by characteristics of the population and by geographic area.

The scope of this paper is limited by the fact that reliable information is not available about the number and characteristics of individual physicians serving Medicare beneficiaries. Although the Medicare claim form requires a physician identifying number (ID), one physician may bill under more than one ID number. Solo practitioners with more than one practice site may be using different ID numbers for each site. In other cases, one physician may be billing under a solo number for certain services and under a group number for other services.1

Because of this limitation, the number and characteristics of physicians who participate in Medicare are not known from central records. Consequently, this study cannot directly follow up other studies that have related physician characteristics to such variables as participation in Medicare, acceptance of assignment, charges, and reimbursements.

Despite the fact that the data used in this study cannot provide solid information on the number of general practitioners and specialists serving Medicare beneficiaries, it can be used to investigate the specialty mix of physicians that patients see in any given year. By linking all claims for each Medicare beneficiary, it is possible to determine the mix of physicians seen by specialty type for every person in the sample (See Sources of the Data) who received Medicare benefits.

The second part of the paper uses these linked claims to analyze the patterns of the mix of physicians used by Medicare beneficiaries, identifying the combinations used most frequently in 1977. This work was suggested by a recent study by Aiken, et al. (1979) that analyzed the practice patterns of a nationwide sample of 10,000 physicians in 24 specialties. In that study diaries were kept by physicians to record their activities. The diaries were used to analyze the physician specialty in relation to the kinds of services provided. The authors concluded that many specialists provide a significant amount of principal care. The requirement for principal care in their study was “an assumption by the physician of continuing responsibility for the patient and a commitment to meeting the majority of the patient's medical needs, irrespective of their nature.”

They found also that the age of the patient was an important variable for certain specialist groups. For example, cardiologists were more likely to meet the majority of medical needs of older patients than they were of younger patients, and obstetricians and gynecologists provided principal care to more younger women than to older women.

From our own general experience and perceptions, several hypotheses were made about the mix of physicians Medicare beneficiaries would use: (1) relatively few patients would see both a physician in general practice and one in internal medicine; (2) the most dominant pattern would be the combination of general practitioners (or internists) with the specialty care physicians; and (3) because some general surgeons provide primary care, one dominant pattern for Medicare patients would be care from general surgeons not in combination with general practitioners or internists. The findings from this part of the study should help in understanding the current practice patterns of care by specialty and in the projection of future medical manpower needs.

Finally, the paper estimates the impact of Medicare on total physician income by specialty. To do this, total physicians' charges from Medicare billings were compared to total physicians' income as reported by the American Medical Association.

Sources of the Data

To obtain detailed information on physicians' services, the Office of Research, Demonstrations, and Statistics (ORDS) in HCFA designed the 5-percent Bill Summary Record System—hereafter referred to as the “Bill Summary.” The Bill Summary was implemented in 1975 and provides detailed data on type of service (for example, medical care, surgery, laboratory, etc.) and site of service (office, hospital, etc.). The Bill Summary record also contains both the physicians' submitted charges and allowed charges under Medicare.

The information contained in the Bill Summary record is based on data submitted on specific HCFA claims forms: the 1490, the basic Part B claims form used by either the patient or physician for billing, and the 1556. For this study, claims submitted on the 1556—used by Group Practice Prepayment Plans (GPPPs) that deal directly with HCFA—were eliminated. Payments to GPPPs account for an estimated 1.5 percent of total reimbursements. Claims for services submitted on the 1554 (by hospital-based physicians) were not included in the Bill Summary system, because reimbursement mechanisms for these services differ from the system generally used (see the section on the Provisions of the Laws). Reimbursements for claims submitted on the 1554 account for an estimated 3 percent of total reimbursements.

The Bill Summary system is based upon a 5-percent sample of Medicare beneficiaries. For ease of data processing, a 1-percent sample of Medicare beneficiaries was selected for this study. For each beneficiary whose health insurance claim number fell into the sample, carriers were instructed to prepare a Bill Summary for all claims. The record includes the Medicare ID number of the beneficiary, the physician's submitted charges, and whether or not the claim was assigned.

It is important to note that neither the diagnosis nor the specific medical or surgical services received have been coded. Thus, the kind of services, for example, visits, injections, cataract operations, were not analyzed for this study. Rather, the only utilization data available were counts of “services.” A service is defined as a procedure having a separate reasonable charge determination. For each type of service and site of service, the record includes the number of services, the physician's charges, and the amount Medicare allowed.

The carrier assigns a 2-digit code for the physician specialty in transmitting payment information to central records. When an association of physicians has the same specialty, it is given a group identification number and assigned the code for its particular specialty group. When an association of physicians has more than one specialty it is given a group identification number and assigned the code meaning “multispecialty” group.

Data from the master health insurance enrollment file, which contains the age, sex, race, and residence of the beneficiary, are incorporated into the Bill Summary record to provide characteristics about the users. At the end of each year, the data base is refined to include only beneficiaries who exceeded the $60 deductible and received Medicare benefits. This was done because some individuals who have not exceeded the deductible do not submit claims. Thus, data for all persons who did not receive reimbursement are deleted from the data base.

Limitations of Data for Hospital-Based Physicians

As noted previously, claims for services submitted on the 1554 (for hospital-based physicians) were not included in the Bill Summary system, because reimbursement mechanisms for these services differ from the payment system generally used. Reimbursements for claims submitted on the 1554 by all types of physicians account for an estimated 3 percent of total reimbursements. However, radiology, pathology, and anesthesiology specialists are more likely to be hospital-based physicians.

Also, bills for the services of some radiologists and pathologists who are hospital-based physicians are included under Part A billings (Form 1483). Later, the Part B trust fund reimburses the Part A trust fund for these physician services. In 1975, the actuary estimated that $69.7 million were paid out of the Part B trust fund for these hospital-based physician services for radiology and pathology; these payments cannot be separated for each type.

Reimbursements from the 1554s ($15.9 million) plus reimbursements from Part A billings ($69.7 million) sum to $85.6 million or 21 percent of the $385.6 million total reimbursements to radiologists, pathologists, and anesthesiologists. Thus, 21 percent of the reimbursements for these specialties cannot be included in the data used in this paper.

The Technical Note following this report provides a discussion of the sampling and non-sampling errors associated with this study.

Provisions of the Law Relating to Physicians' Services

The Supplementary Medical Insurance Program, Part B of Medicare, provides coverage for a variety of medical services and supplies furnished by physicians. For the beneficiary population age 65 years and over, approximately 82 percent of all Part B reimbursements in 1975 were for physicians and related care. The remaining Part B reimbursements were for outpatient hospital and home health services. In 1975, of the 82 percent reimbursed for physicians' and related care, 76 percent of the reimbursements were for physicians' services. The remaining 6 percent was for related services which included surgical and medical equipment, drugs and biologicals administered by the physician, prostheses, ambulance services, and independent laboratory services.

The Part B Program is designed to operate throughout the nation with a uniform set of benefits and a uniform set of cost-sharing requirements in the form of deductibles and coinsurance. Also, there is a uniform monthly premium required for participation in Part B. After the beneficiary has met a deductible of $60, the program reimburses 80 percent of allowed charges and the beneficiary is responsible for 20 percent of allowed charges.

Under Part B, the physician can accept or reject assignment of payment. If assignment is accepted, the physician agrees to accept the allowed charge as full payment, and the physician is paid directly by the program. If assignment is not accepted, the program reimburses the beneficiary directly, and the beneficiary is liable for the difference between the submitted and the allowed charge.

To determine allowed charges, Medicare uses the customary, prevailing, and reasonable charge (CPR) method. Under Medicare the “reasonable” or “allowed” charge is the lowest of (1) the actual charge made by the physician for that service, (2) the physician's customary charge (the physician's 50th percentile) for that service, or (3) the prevailing charge (set at the 75th percentile of weighted customaries) in the locality for that service.

In response to concern about the continuing rise in physicians' charges—and the fact that under the CPR method submitting higher charges one year raises the basis for reimbursement the next year—legislation was enacted to control the rate of increase in Medicare reimbursements. Starting with fiscal year 1976, prevailing charges (the maximum Medicare allows) have been limited by an economic index. The index parallels the rate of increase in certain economic indicators that relate to the cost of maintaining an office practice and to the earnings level in the general economy.

Findings

Specialties of Physicians Serving Medicare Beneficiaries

Aged

As noted previously, twelve specialties or specialty groups, general practice, and two commonly used non-physician providers, chiropractors and podiatrists, were chosen for this study. Using the criteria of the number of reimbursed users, these 15 groups along with the “multi-specialty” category were the most frequent categories. In 1975, the selected specialties accounted for 89 percent of total reimbursements from the Bill Summary data system. These categories and their rank according to the number of persons reimbursed and the number of services used are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Rank Order by Specialty of Number of Aged Persons Reimbursed by Medicare and Rank Order of Number of Services Used, U.S., 1975 and 1977.

| Specialty | Persons Reimbursed | Number of Services | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| 1975 | 1977 | 1975 | 1977 | |

| General Practice (GP) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 14 | 8 | 8 | 4 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | 13 | 14 | 10 | 9 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 11 | 13 | 15 | 15 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 5 | 4 | 6 | 8 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 9 | 10 | 11 | 11 |

| Urology (U) | 8 | 9 | 7 | 10 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | 7 | 7 | NA | NA |

| Pathology (P) | 15 | 15 | 9 | 7 |

| Radiology (R) | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 16 | 16 | 14 | 14 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 10 | 11 | 12 | 12 |

| Multi-Specialty Group (M) | 6 | 6 | 4 | 6 |

Note: Data for anesthesiology, pathology, and radiology are biased downward throughout the present study since all forms of reimbursement to them are not included in this data base. Groups of physicians with mixed specialties are designated as “multi-specialty” in the Medicare Statistical System and, therefore, may further bias downwards the estimates in this study for each specialty (see “Sources of the Data” section).

As indicated in Table 2, general practice, internal medicine, and radiology had the greatest number of Medicare beneficiaries reimbursed in 1975 and 1977, ranking 1, 2, or 3 each year. For the other specialties, the rankings for the number of beneficiaries with reimbursements in 1977 were similar to those in 1975 except for family practice which rose in rank order from fourteenth to eighth. With regard to the number of services used, internal medicine, general practice and general surgery ranked 1, 2, and 3 for 1975. In 1977, internal medicine and general practice remained first and second in rank and radiology rose from the rank of 5 to 3. Also, family practice changed in ranking from eighth to fourth for the number of services received.2

Disabled

In 1973, Medicare coverage was extended to disabled persons receiving cash benefits under the Social Security Act for 24 consecutive months. Nearly 80 percent of the disabled are between 45 and 64 and nearly two-thirds are men.

The rank order of the number of persons reimbursed and the number of services received by the disabled Medicare population by physician specialty are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Rank Order by Specialty of Number of Disabled Persons Reimbursed by Medicare and Rank Order of Number of Services Used, U.S., 1975 and 1977.

| Specialty | Persons Reimbursed | Number of Services | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| 1975 | 1977 | 1975 | 1977 | |

| General Practice (GP) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 11 | 9 | 10 | 6 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | 10 | 10 | 9 | 8 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 15 | 15 | 15 | 14 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 13 | 14 | 14 | 15 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 8 | 8 | 12 | 13 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 9 |

| Urology (U) | 9 | 11 | 8 | 10 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | 6 | 6 | NA | NA |

| Pathology (P) | 12 | 12 | 6 | 7 |

| Radiology (R) | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 16 | 16 | 11 | 11 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 14 | 13 | 13 | 12 |

| Multi-Specialty Group (M) | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

For the disabled population, general practice, internal medicine, and radiology were the most frequently used specialties in 1975 and 1977, and ranked 1, 2, or 3 each year. For the other specialties, the rankings for the number of beneficiaries with reimbursements in 1977 were similar to those in 1975. In both years, the greatest number of services were provided by physicians in internal medicine, general practice, and multi-specialty groups—ranking 1, 2 and 3. For the other specialties, the rankings for the number of services received in 1977 were similar to those in 1975 except for family practice which rose in rank order from tenth to sixth.

These data indicate that several differences exist between the aged and disabled with regard to the importance of particular physician specialties. Comparing rankings for 1977, ophthalmology ranked fourth in importance for aged persons compared to eighth for the disabled; and for the number of services there was an even wider spread between rankings. Also, notably more aged persons were served by dermatologists. On the other hand, a higher percent of disabled persons were served by cardiologists, orthopedic surgeons, and pathologists. This is related to the fact that cardiovascular and musculoskeletal conditions are leading causes of disability under Social Security. (Krute and Burdette, 1978)

No other results are reported for the disabled in this paper because the one-percent sample selected for this study is too small to report use rates of the disabled. A future study is planned based on the full 5 percent Part B Bill Summary.

Use and Reimbursement Rates by Specialty

Rate of Aged Persons Receiving Reimbursement for Physicians' Services

In 1975 there were 21,945,301 persons enrolled in Part B. Of these persons enrolled, 10.7 million persons or 492 persons per 1,000 enrollees received reimbursement for physicians' services, for all specialties combined. (See Table 4.) General practitioners and internists far exceeded all other types of physicians in the rate of reimbursed users. The rate of reimbursed users in 1975 ranged from a low of 10 reimbursed beneficiaries per 1,000 enrollees for services of chiropractors to a high of 219 reimbursed beneficiaries per 1,000 enrollees for services by general practitioners. The rate for internists (217) nearly matched the rate for general practitioners.

Table 4. Number of Aged Persons Reimbursed Per 1,000 Enrolled in Medicare, by Specialty, U.S., 1975 and 1977.

| Specialty | Number of Persons Per 1,000 Enrolled | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| 1975 | 1977 | |

| All Specialties | 492 | 523 |

| General Practice (GP) | 219 | 189 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 27 | 52 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 217 | 228 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | 31 | 33 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 31 | 35 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 95 | 92 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 32 | 33 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 94 | 106 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 44 | 46 |

| Urology (U) | 45 | 47 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | 50 | 53 |

| Pathology (P) | 22 | 23 |

| Radiology (R) | 133 | 155 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 10 | 11 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 39 | 46 |

| Multi-Specialty Group (M) | 57 | 59 |

In 1977, the rate of reimbursed users increased to 523 per 1,000 enrollees. Since the deductible remained constant during this period, the increase in the total number of reimbursed users between 1975 and 1977 very likely reflects the increase in physicians' prices. The medical care component of the consumer price index (CPI) was 169.4 in 1975 and 206.0 in 1977. Therefore, even with no change in use, more persons would exceed the deductible amount and receive reimbursement.

From 1975 to 1977 the rate of reimbursed beneficiaries per 1,000 enrollees decreased somewhat for general practitioners while the rate nearly doubled for family practitioners (27 to 52) no doubt accounting for much of the decline in general practitioner users. Figure 1 summarizes these findings and illustrates the relative importance of each specialty.

Figure 1. Number of Part B Beneficiaries Reimbursed by Physician Specialty (per 1,000 Enrollees).

General Table I (end of text) shows the number of persons per 1,000 enrolled in Part B who received reimbursement for physicians' services, by physician specialty, and by age, sex, race, and census region. The data indicate that for nearly all specialties, the number of aged persons per 1,000 enrollees who received reimbursements generally was higher for increasingly older age groups.

General Table I. Medicare Beneficiaries: Number of Persons Reimbursed and Persons Reimbursed Per 1,000 Enrollees, by Physician Specialty, and by Age, Sex, Race, and Census Region, 1975 and 1977.

| Number of Persons (thousands) | Persons Receiving Reimbursements Per 1,000 Enrollees | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| Specialty | U.S. Total | Age | Sex | Race | Census Region | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| 65-69 | 70-74 | 75-79 | 80-84 | 85 + | Men | Women | White | Other | NE | NC | South | West | |||

| 1975 | |||||||||||||||

| All Specialties | 10,729 | 492 | 409 | 497 | 531 | 571 | 609 | 468 | 508 | 504 | 419 | 515 | 448 | 476 | 567 |

| General Practice (GP) | 4,769 | 219 | 170 | 217 | 240 | 268 | 301 | 201 | 231 | 223 | 202 | 187 | 191 | 244 | 267 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 585 | 27 | 21 | 27 | 29 | 33 | 37 | 25 | 28 | 27 | 26 | 34 | 30 | 25 | 13 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 4,740 | 217 | 178 | 225 | 240 | 251 | 252 | 208 | 224 | 224 | 168 | 263 | 180 | 202 | 242 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | 674 | 31 | 27 | 31 | 33 | 35 | 35 | 34 | 29 | 32 | 25 | 34 | 30 | 25 | 38 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 675 | 31 | 27 | 34 | 34 | 33 | 29 | 32 | 30 | 33 | 12 | 30 | 18 | 33 | 49 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 2,076 | 95 | 82 | 99 | 100 | 106 | 112 | 94 | 96 | 98 | 75 | 103 | 90 | 95 | 94 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 688 | 32 | 27 | 35 | 34 | 35 | 28 | 31 | 32 | 34 | 14 | 36 | 21 | 28 | 49 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 2,050 | 94 | 66 | 100 | 116 | 120 | 97 | 79 | 104 | 99 | 56 | 123 | 62 | 83 | 126 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 960 | 44 | 37 | 44 | 47 | 51 | 55 | 32 | 52 | 47 | 20 | 50 | 33 | 43 | 56 |

| Urology (U) | 990 | 45 | 36 | 51 | 51 | 50 | 46 | 72 | 27 | 47 | 32 | 47 | 36 | 48 | 54 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | 1,087 | 50 | 44 | 52 | 52 | 56 | 53 | 58 | 45 | 52 | 32 | 54 | 45 | 43 | 66 |

| Pathology (P) | 485 | 22 | 19 | 23 | 24 | 26 | 25 | 23 | 22 | 23 | 17 | 9 | 20 | 37 | 18 |

| Radiology (R) | 2,905 | 133 | 113 | 138 | 144 | 147 | 155 | 131 | 135 | 137 | 109 | 109 | 122 | 155 | 149 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 220 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 18 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 855 | 39 | 22 | 34 | 46 | 59 | 82 | 26 | 48 | 40 | 30 | 73 | 21 | 25 | 46 |

| Multi-Specialty Group (M) | 1,249 | 57 | 49 | 59 | 63 | 63 | 65 | 57 | 57 | 59 | 51 | 28 | 70 | 54 | 86 |

| Unknown | 623 | 29 | 21 | 27 | 32 | 37 | 43 | 29 | 28 | 30 | 15 | 44 | 40 | 12 | 18 |

| All other (residual) | 1,914 | 88 | 81 | 92 | 94 | 93 | 82 | 78 | 94 | 91 | 68 | 107 | 70 | 85 | 95 |

| 1977 | |||||||||||||||

| All Specialties | 11,934 | 523 | 470 | 518 | 557 | 571 | 603 | 500 | 539 | 533 | 434 | 552 | 486 | 490 | 607 |

| General Practice (GP) | 4,322 | 189 | 158 | 183 | 206 | 220 | 251 | 175 | 199 | 192 | 165 | 162 | 184 | 184 | 253 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 1,181 | 52 | 44 | 50 | 56 | 58 | 67 | 47 | 55 | 53 | 44 | 51 | 43 | 67 | 37 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 5,212 | 228 | 199 | 232 | 250 | 251 | 253 | 220 | 234 | 235 | 173 | 276 | 193 | 209 | 256 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | 742 | 33 | 29 | 33 | 36 | 36 | 32 | 37 | 29 | 33 | 27 | 43 | 24 | 28 | 41 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 804 | 35 | 33 | 38 | 37 | 34 | 32 | 37 | 34 | 38 | 11 | 34 | 22 | 36 | 58 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 2,109 | 92 | 84 | 92 | 98 | 101 | 99 | 93 | 92 | 95 | 71 | 102 | 88 | 88 | 95 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 761 | 33 | 31 | 36 | 36 | 33 | 28 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 13 | 38 | 24 | 28 | 52 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 2,414 | 106 | 80 | 113 | 129 | 128 | 104 | 87 | 118 | 111 | 57 | 136 | 74 | 88 | 147 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 1,056 | 46 | 41 | 45 | 49 | 51 | 57 | 32 | 56 | 49 | 20 | 53 | 37 | 43 | 60 |

| Urology (U) | 1,072 | 47 | 40 | 50 | 53 | 51 | 45 | 77 | 27 | 49 | 32 | 50 | 38 | 48 | 57 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | 1,215 | 53 | 49 | 54 | 56 | 56 | 59 | 63 | 47 | 55 | 36 | 59 | 46 | 43 | 75 |

| Pathology (P) | 532 | 23 | 21 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 24 | 23 | 24 | 16 | 9 | 18 | 40 | 20 |

| Radiology (R) | 3,538 | 155 | 140 | 154 | 167 | 167 | 175 | 155 | 155 | 159 | 122 | 136 | 147 | 163 | 182 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 261 | 11 | 14 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 5 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 3 | 8 | 12 | 8 | 22 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 1,047 | 46 | 26 | 39 | 52 | 70 | 94 | 30 | 56 | 47 | 33 | 86 | 26 | 26 | 57 |

| Multi-Specialty Group (M) | 1,338 | 59 | 53 | 59 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 58 | 59 | 59 | 50 | 35 | 83 | 34 | 101 |

| Unknown | 484 | 21 | 17 | 20 | 23 | 25 | 31 | 21 | 21 | 23 | 11 | 20 | 36 | 11 | 18 |

| All other (residual) | 2,230 | 98 | 94 | 102 | 103 | 99 | 88 | 90 | 103 | 101 | 70 | 124 | 77 | 87 | 115 |

For most specialties, the rate was higher for women than men. For general practice in 1975, the rates were 231 women and 201 men reimbursed per 1,000 enrollees, and for internal medicine, the rates were 224 for women and 208 for men. Reversals to the pattern of higher rates for women compared to men occurred for services of specialists in cardiovascular disease, urology, and anesthesiology.

For every specialty and specialty group, the rate for white persons reimbursed per 1,000 enrollees was higher than for all other races. Differences by race in average reimbursements for physicians' services are offset, in part, by differences in use and reimbursement for hospital outpatient care. Data from the Medicare Statistical System for the United States indicate that 17 percent of white beneficiaries compared with 20 percent of non-white beneficiaries received Medicare reimbursement for hospital outpatient care in 1975.

With regard to regional variations, the rate of reimbursed users in 1975 for all specialities combined ranged from a low of 448 persons reimbursed per 1,000 enrollees in the North Central region to a high of 567 in the West—representing a difference of 27 percent between the highest and lowest region. The Northeast ranked below the West, followed by the South and the North Central regions. These variations by region are explained, in part, by regional differences in price levels. Frequently, it has been reported that physicians' charges for the same service vary substantially by geographic area, with the Northeast and the West having the highest Medicare charges, followed by the South and North Central regions (Burney, 1978). The rankings of the regions on the rate of reimbursed users for all specialties combined remained the same in 1977, but the difference in the range between the highest and lowest region decreased to 24 percent.

The moderate range across regions in the rate of reimbursed users for all specialties combined is in striking contrast to the often very large range across regions for certain specialties (Table 5). For example, the range for ophthalmology in 1977 was 74 persons reimbursed per 1,000 enrollees in the North Central region and 147 persons reimbursed per 1,000 enrollees in the West, representing nearly a 100 percent difference. Of the specialties studied, the range between the highest and lowest region in the rate of reimbursed persons was even higher for dermatology (164 percent), otology, laryngology, rhinology (117 percent), pathology (344 percent), chiropractic (175 percent), and podiatry (231 percent). It may also be noted that for each specialty the West most frequently ranked first and the North Central region most frequently ranked fourth in the percent of reimbursed persons, with the other two regions occupying positions two and three. However, there is a fair amount of shifting in the regional rankings by specialty.

Table 5. U.S. Census Regions Ranked According to Number of Reimbursed Aged Persons Per 1,000 Enrolled in Medicare, and Percent Difference in Range between the Highest and Lowest Region, by Specialty, 1977.

| Specialty | Rank | Percent Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| NE | NC | South | West | ||

| All Specialties | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 24 |

| General Practice (GP) | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 56 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 81 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 43 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 79 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 164 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 16 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 117 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 99 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 62 |

| Urology (U) | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 50 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 74 |

| Pathology (P) | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 344 |

| Radiology (R) | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 34 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 175 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 231 |

| Multi-Specialty Group (M) | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 197 |

Variations in use by specialty and by geographic area very likely reflect, in part, differences in the supply of physicians. Table 6 shows the rate of non-federal physicians per 100,000 Medicare Part B enrollees by specialty and by U.S. Census Region for 1975. The table also shows the ratio of the rate in the region to the rate in the U.S.

Table 6. Number and Ratio of Non-Federal Physicians Per 100,000 Medicare Enrollees by Specialty, by U.S. Census Region, 1975.

| Rate (physicians per 100,000 enrollees) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Region | Total | GP & FP | IM | CD | DER | GS | OLR | OPH | OR | U | A | P | R | |

| U.S. | 1637 | 237 | 220 | 29 | 19 | 134 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 28 | 55 | 48 | 48 | |

| Northeast | 1934 | 206 | 308 | 39 | 22 | 159 | 26 | 54 | 49 | 29 | 66 | 57 | 54 | |

| North Central | 1382 | 237 | 185 | 22 | 15 | 121 | 20 | 40 | 38 | 24 | 46 | 45 | 44 | |

| South | 1404 | 218 | 167 | 25 | 17 | 120 | 22 | 44 | 43 | 28 | 42 | 39 | 41 | |

| West | 2072 | 320 | 249 | 35 | 28 | 143 | 31 | 63 | 72 | 35 | 80 | 55 | 60 | |

| Ratio (Rate in region to U.S.) | ||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| U.S. | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Northeast | 1.18 | 0.87 | 1.40 | 1.34 | 1.16 | 1.19 | 1.08 | 1.13 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 1.20 | 1.19 | 1.13 | |

| North Central | 0.84 | 1.00 | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.79 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 0.92 | |

| South | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.76 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.85 | |

| West | 1.27 | 1.35 | 1.13 | 1.21 | 1.47 | 1.07 | 1.29 | 1.31 | 1.50 | 1.25 | 1.45 | 1.15 | 1.25 | |

| Percent difference between highest and lowest region | 50 | 55 | 84 | 77 | 87 | 33 | 55 | 58 | 89 | 46 | 90 | 46 | 46 | |

Source: Number of physicians from “Physician Distribution and Medical Licensure in U.S., 1975,” American Medical Association 1976.

The data indicate that for the U.S. the supply of general practitioners combined with family practitioners was the highest (237 physicians per 100,000 enrollees). Internal medicine follows close behind (220), and then general surgeons (134).

It can be observed that the ratio of the supply of physicians in a region to the U.S. was greater than 1.00 for the West in every specialty. The ratio was also greater than 1.00 in the Northeast for every speciality except general and family practice combined. In contrast, the ratios for the North Central and South were below the national average for every specialty except general and family practice combined in the North Central region, where the supply of general and family practice combined was at the U.S. average.

The percent difference between the highest and the lowest region in the number of physicians per 100,000 Medicare enrollees for each specialty is also shown in Table 6. This percent difference ranged from a high of 90 percent for anesthesiology to a low of 33 percent for general surgery. As shown earlier, some specialties had much larger percent differences between the highest and lowest regions in the number of reimbursed persons per 1,000 enrolled.

For dermatology, the percent difference between the West and North Central regions in the number of reimbursed persons was 164 percent compared to an 87 percent difference in the rate of physicians. For otology, laryngology, rhinology, the percent difference between the West and the North Central regions in the number of reimbursed persons was 117 percent compared to a 55 percent difference in the rate of physicians. For pathology, the data are very perplexing with the South having the highest rate of reimbursed persons but the lowest ratio of pathologists to population. This finding requires further study.

Number of Reimbursed Services Per User

In 1975 an average of 21.9 services were received per reimbursed user for all types of physicians combined, with a range of from 2.9 ophthalmology services per reimbursed user to 12.9 internal medicine services per reimbursed user. In 1977, the overall rate was 20.7 services per user for all types of physicians with the rate by specialty relatively the same as in 1975, except for general practice—which decreased from 12.7 to 11.8 services per user; family practice—which increased from 9.8 to 11.4 services per user; and pathology—which increased from 11.8 to 13.3 services per user (Table 7).

Table 7. Average Number of Services Per Reimbursed User Under Medicare, by Specialty, U.S., 1975 and 1977.

| Specialty | Number of Services Per Reimbursed User | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 1975 | 1977 | |

| All Specialties | 21.9 | 20.7 |

| General Practice (GP) | 12.7 | 11.8 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 9.8 | 11.4 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 12.9 | 12.8 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | 8.5 | 8.3 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 4.3 | 4.1 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 6.5 | 6.2 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 3.3 | 3.0 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 2.9 | 2.6 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 5.1 | 4.9 |

| Urology (U) | 5.8 | 5.6 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | NA | NA |

| Pathology (P) | 11.8 | 13.3 |

| Radiology (R) | 4.4 | 4.1 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 12.5 | 12.0 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 4.8 | 4.5 |

| Multi-Specialty Group (M) | 10.2 | 9.2 |

General Table II shows the number of services per reimbursed user by physician specialty and by age, sex, race, and census region. For nearly all specialties, the number of services per reimbursed user was generally higher for older age groups. The number of services received per reimbursed user for all specialties combined was nearly the same for men and women.

General Table II. Medicare Beneficiaries: Number of Services Reimbursed and the Number of Services per Reimbursed User, by Physician Specialty, and by Age, Sex, Race and Census Region, 1975 and 1977.

| Number of Services (thousands) | Services Per Reimbursed User | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| Specialty | U.S. Total | Age | Sex | Race | Census Region | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| 65-69 | 70-74 | 75-79 | 80-84 | 85 + | Men | Women | White | Other | NE | NC | South | West | |||

| 1975 | |||||||||||||||

| All Specialties | 234,931 | 21.9 | 20.7 | 22.1 | 22.6 | 22.9 | 21.8 | 22.6 | 21.5 | 22.0 | 21.2 | 21.5 | 21.1 | 23.5 | 21.0 |

| General Practice (GP) | 60.644 | 12.7 | 11.8 | 12.4 | 13.2 | 13.6 | 13.7 | 12.4 | 12.9 | 12.6 | 13.8 | 11.7 | 12.9 | 13.8 | 11.7 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 5,752 | 9.8 | 9.0 | 9.8 | 10.2 | 10.3 | 10.5 | 10.1 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 11.2 | 10.4 | 9.4 | 10.1 | 8.5 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 60,946 | 12.9 | 12.1 | 12.8 | 13.2 | 13.8 | 13.1 | 13.1 | 12.7 | 12.9 | 12.5 | 14.0 | 12.2 | 12.4 | 12.5 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | 5,726 | 8.5 | 8.3 | 8.5 | 8.6 | 9.4 | 7.6 | 8.7 | 8.3 | 8.6 | 7.2 | 10.3 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 8.1 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 2,897 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 6.7 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 5.0 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 13,546 | 6.5 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 7.1 | 6.4 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 7.1 | 6.1 | 7.0 | 6.8 | 5.8 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 2,236 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 5,979 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 2.9 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 4,926 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 5.8 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 5.1 |

| Urology (U) | 5,774 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 5.6 | 6.0 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 6.7 | 5.4 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 6.6 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pathology (P) | 5,740 | 11.8 | 11.2 | 12.2 | 12.2 | 11.9 | 11.6 | 12.9 | 11.0 | 11.8 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 13.6 | 12.1 | 9.2 |

| Radiology (R) | 12,678 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 3.7 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 2,758 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 12.4 | 12.5 | 12.3 | 10.6 | 11.8 | 13.0 | 12.8 | 12.3 | 14.1 | 12.0 | 12.9 | 11.5 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 4,081 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 4.5 | 3.9 |

| Multi-Specialty Group (M) | 12,774 | 10.2 | 10.5 | 10.3 | 10.2 | 9.7 | 10.3 | 10.5 | 10.1 | 10.3 | 10.1 | 8.3 | 9.1 | 11.7 | 11.0 |

| Unknown | 5,346 | 8.6 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 9.1 | 9.0 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 8.3 | 8.7 | 6.2 | 8.1 | 11.3 | 6.4 | 3.1 |

| All other (residual) | 13,306 | 7.0 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 6.5 | 6.8 | 6.4 | 7.5 | 6.7 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 6.8 | 6.6 | 7.5 | 6.6 |

| 1977 | |||||||||||||||

| All Specialties | 247,133 | 20.7 | 19.2 | 20.7 | 21.8 | 21.7 | 21.7 | 21.4 | 20.3 | 20.8 | 20.2 | 19.7 | 20.7 | 21.3 | 21.1 |

| General Practice (GP) | 50,883 | 11.8 | 10.8 | 11.4 | 12.2 | 12.6 | 13.1 | 11.6 | 11.9 | 11.7 | 13.3 | 10.4 | 12.7 | 12.5 | 11.0 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 13,418 | 11.4 | 10.6 | 11.2 | 11.8 | 12.2 | 11.8 | 11.2 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 13.0 | 10.2 | 10.7 | 13.1 | 8.9 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 66,837 | 12.8 | 12.0 | 12.6 | 13.4 | 13.6 | 13.6 | 12.8 | 12.8 | 12.8 | 13.5 | 13.1 | 13.0 | 12.7 | 12.4 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | 6,195 | 8.3 | 8.0 | 8.5 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 8.3 | 8.4 | 7.7 | 9.3 | 7.3 | 7.8 | 8.4 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 3,289 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 5.0 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 4.9 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 13,174 | 6.2 | 5.6 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 7.0 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 6.2 | 7.0 | 5.7 | 6.5 | 6.6 | 6.0 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 2,270 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 6,240 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 5,121 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 5.2 | 5.2 |

| Urology (U) | 5,980 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 5.7 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 6.1 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 5.8 | 6.3 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pathology (P) | 7,058 | 13.3 | 11.9 | 12.7 | 14.5 | 14.0 | 15.3 | 14.9 | 12.1 | 13.2 | 14.3 | 7.8 | 14.6 | 14.2 | 11.5 |

| Radiology (R) | 14,540 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 3.7 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 3,138 | 12.0 | 12.5 | 12.0 | 11.6 | 11.4 | 10.4 | 11.3 | 12.5 | 12.1 | 11.1 | 13.0 | 12.6 | 11.9 | 11.0 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 4,709 | 4.5 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 5.6 | 4.8 | 4.1 | 4.6 | 4.0 |

| Multi-Specialty Group (M) | 12,325 | 9.2 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 9.3 | 9.4 | 8.7 | 9.4 | 9.1 | 9.2 | 9.5 | 7.6 | 8.9 | 8.7 | 10.8 |

| Unknown | 4,810 | 9.9 | 9.4 | 9.5 | 9.8 | 9.9 | 12.0 | 10.5 | 9.5 | 10.2 | 5.5 | 11.1 | 13.8 | 3.3 | 2.9 |

| All other (residual) | 15,308 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 6.6 | 7.3 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 7.5 | 6.8 | 6.7 | 7.1 | 6.7 |

The number of reimbursed services per user by speciality can be misleading if it is not kept in mind that the number of users varies greatly by speciality. For example, the number of services per user is similar for chiropractors, general practitioners, and internists. But there are far fewer users of chiropractors. Thus, the number of reimbursed services per enrollee takes both factors into account.

Number of Reimbursed Services Per Enrollee

In both 1975 and 1977, there were approximately 11 reimbursed services per aged enrollee for all types of physicians (Table 8). It is interesting to note that in 1975, about half the total number of reimbursed services per enrollee were supplied by general practitioners and internal medicine specialists.

Table 8. Average Number of Reimbursed Services Per Aged Enrollee Under Medicare, by Specialty, U.S., 1975 and 1977.

| Specialty | Average Number of Reimbursed Services Per Enrollee | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| 1975 | 1977 | |

| All Specialties | 10.78 | 10.83 |

| General Practice (GP) | 2.78 | 2.23 |

| Family Practice (FP) | .26 | .59 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 2.80 | 2.93 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | .26 | .27 |

| Dermatology (DER) | .13 | .14 |

| General Surgery (GS) | .62 | .58 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | .10 | .10 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | .27 | .27 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | .23 | .22 |

| Urology (U) | .27 | .26 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | NA | NA |

| Pathology (P) | .26 | .31 |

| Radiology (R) | .58 | .64 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | .13 | .14 |

| Podiatry (POD) | .19 | .21 |

| Multi-Specialty Group (M) | .59 | .54 |

As shown in Table 8, there was a decrease in the annual rate of services per beneficiary from general practitioners from 1975 to 1977. All other specialties had similar rates both years except family practice, which more than doubled its rate. As observed earlier, the rise in family practice no doubt accounts for much of the decline in the rate for general practitioners.

Average Total and Allowed Charges Per Service

In 1975, average total charge per service was $19.47 (Table 9). The range was from a low of $6.76 for pathology services to a high of $50.30 for orthopedic surgery services. Average charges for surgical specialties (GS, OLR, OPH, ORS and U) were considerably greater than all other categories, ranging from $25 to $50. It can be observed that charges for general practitioners and family practitioners were similar ($11.35 and $11.50, respectively) whereas the average charge for internal medicine ($15.48) was about 35 percent higher than either general or family practice.

Table 9. Average Submitted Charge Per Service and Percent Reduction in Charge for Aged Medicare Users, U.S., 1975 and 1977.

| 1975 | 1977 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Specialty | Average Submitted Charge Per Service | Percent Reduction | Average Submitted Charge Per Service | Percent Reduction | Percent Increase in Charge |

| All Specialties | $19.47 | 18.7 | $24.06 | 19.5 | 19.1 |

| General Practice (GP) | 11.35 | 18.6 | 13.25 | 18.2 | 13.6 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 11.50 | 19.2 | 12.79 | 19.4 | 10.1 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 15.48 | 18.2 | 17.92 | 19.4 | 14.3 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | 22.00 | 19.0 | 26.70 | 18.6 | 17.6 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 19.58 | 17.1 | 24.67 | 17.2 | 20.6 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 38.44 | 18.8 | 51.61 | 20.1 | 25.5 |

| Otology, Laryngology, Rhinology (OLR) | 25.67 | 21.0 | 34.32 | 21.4 | 25.2 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 48.85 | 17.3 | 64.87 | 16.9 | 24.7 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 50.30 | 19.6 | 68.90 | 20.7 | 27.0 |

| Urology (U) | 40.71 | 18.4 | 53.19 | 19.1 | 24.5 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pathology (P) | 6.76 | 16.3 | 5.80 | 16.0 | 16.6 |

| Radiology (R) | 18.27 | 15.0 | 20.89 | 15.8 | 12.5 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 9.13 | 13.3 | 10.44 | 16.0 | 12.6 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 18.57 | 20.0 | 21.98 | 21.7 | 15.5 |

| Multi-Specialty Group (M) | 20.30 | 18.3 | 27.29 | 18.4 | 25.6 |

By 1977, average charge per service rose to $24.06, which represents an increase of 19.1 percent between 1975 and 1977. Average charges during this period rose for all specialties except pathology, which decreased. Although the average charge decreased for pathology, there was an increased rate of pathology services per user in 1977. Perhaps batteries of tests are more frequently reported now as single services. More study is required to understand the observed decrease in average pathology charges.

The percent increase in average charges from 1975 to 1977 ranged from a low of 10 percent for family practice to 27 percent for orthopedic surgery, with all the surgical specialties having the largest percent differences.

Under Medicare's Customary, Prevailing, and Reasonable Charge (CPR) mechanism, physicians' charges are passed through screens to determine the “reasonable” or “allowed” charge for each service. In 1975, total charges for all physicians were reduced 18.7 percent as a result of the CPR mechanism.

The average percent reduction ranged from a low of 13.3 percent for chiropractors to a high of 21.0 percent for otology, laryngology, and rhinology. In 1977, the percent reduction by specialty was similar or slightly larger than in 1975 (Table 9).

General Table III shows the average submitted charge per service, average allowed charge per service, and percent reduction by physician specialty and census region for the years 1975 and 1977.

General Table III. Medicare Beneficiaries: Average Submitted Charge Per Service, Average Allowed Charge Per Service and Percent Reduction by Physician Specialty, and Census Region, 1975 and 1977.

| United States | Northeast | North Central | South | West | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Specialty | Average Submit. Charge | Average Allowed Charge | Percent Reduction | Average Submit. Charge | Average Allowed Charge | Percent Reduction | Average Submit. Charge | Average Allowed Charge | Percent Reduction | Average Submit. Charge | Average Allowed Charge | Percent Reduction | Average Submit. Charge | Average Allowed Charge | Percent Reduction |

| 1975 | |||||||||||||||

| All Specialties | $19.47 | $15.83 | 18.7 | $21.42 | $17.09 | 20.2 | $18.46 | $15.29 | 17.2 | $17.00 | $13.89 | 18.3 | $22.53 | $18.27 | 18.9 |

| General Practice (GP) | 11.35 | 9.24 | 18.6 | 11.79 | 9.61 | 18.5 | 10.96 | 9.02 | 17.7 | 10.30 | 8.35 | 18.9 | 13.63 | 11.04 | 19.0 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 11.50 | 9.29 | 19.2 | 11.47 | 9.32 | 18.7 | 12.00 | 9.56 | 20.3 | 10.29 | 8.40 | 18.4 | 14.81 | 11.86 | 19.9 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 15.48 | 12.66 | 18.2 | 16.27 | 13.13 | 19.3 | 14.63 | 12.16 | 16.9 | 14.51 | 11.89 | 18.1 | 16.65 | 13.63 | 18.1 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | 22.00 | 17.83 | 19.0 | 20.74 | 16.67 | 19.6 | 22.84 | 18.71 | 18.1 | 19.72 | 16.05 | 18.6 | 25.98 | 20.98 | 19.2 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 19.58 | 16.24 | 17.1 | 23.52 | 18.88 | 19.7 | 18.65 | 15.53 | 16.7 | 17.78 | 15.06 | 15.3 | 18.99 | 15.85 | 16.5 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 38.44 | 31.20 | 18.8 | 46.00 | 35.96 | 21.8 | 33.39 | 27.92 | 16.4 | 32.41 | 26.61 | 17.9 | 48.91 | 39.83 | 18.6 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 25.67 | 20.28 | 21.0 | 26.37 | 21.15 | 19.8 | 25.28 | 20.64 | 18.4 | 24.39 | 18.89 | 22.6 | 26.59 | 20.63 | 22.4 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 48.85 | 40.38 | 17.3 | 51.55 | 41.53 | 19.4 | 47.85 | 40.17 | 16.1 | 45.76 | 38.14 | 16.7 | 50.08 | 41.97 | 16.2 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 50.30 | 40.44 | 19.6 | 51.58 | 40.07 | 22.3 | 56.49 | 46.05 | 18.5 | 40.02 | 32.64 | 18.4 | 59.16 | 48.10 | 18.7 |

| Urology (U) | 40.71 | 33.22 | 18.4 | 51.13 | 40.77 | 20.3 | 41.50 | 34.61 | 16.6 | 32.73 | 26.94 | 17.7 | 41.26 | 33.63 | 18.5 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pathology (P) | 6.76 | 5.66 | 16.3 | 9.20 | 7.61 | 17.3 | 6.30 | 5.47 | 13.2 | 6.50 | 5.34 | 17.8 | 7.45 | 6.32 | 15.2 |

| Radiology (R) | 18.27 | 15.53 | 15.0 | 21.24 | 17.80 | 16.2 | 15.75 | 13.59 | 13.7 | 16.93 | 14.34 | 15.3 | 22.96 | 19.55 | 14.9 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 9.13 | 7.92 | 13.3 | 8.91 | 7.93 | 11.0 | 8.41 | 7.23 | 14.0 | 8.82 | 7.64 | 13.4 | 10.27 | 8.80 | 14.3 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 18.57 | 14.85 | 20.0 | 16.57 | 12.94 | 21.9 | 21.57 | 17.10 | 20.7 | 20.16 | 16.71 | 17.1 | 21.09 | 17.33 | 17.8 |

| Multi-Specialty (M) | 20.30 | 16.59 | 18.3 | 18.93 | 14.95 | 21.0 | 24.10 | 19.90 | 17.4 | 16.37 | 13.48 | 17.7 | 21.48 | 17.39 | 19.0 |

| Unknown | 17.06 | 14.37 | 15.8 | 22.14 | 18.33 | 17.2 | 12.85 | 11.12 | 13.5 | 19.43 | 15.93 | 18.0 | 18.46 | 15.75 | 14.7 |

| All other (residual) | 30.89 | 24.37 | 21.1 | 32.18 | 24.57 | 23.6 | 28.65 | 23.39 | 18.4 | 27.76 | 22.19 | 20.1 | 37.48 | 29.47 | 21.3 |

| 1977 | |||||||||||||||

| All Specialties | $24.06 | $19.38 | 19.5 | $26.63 | $21.29 | 20.0 | $22.29 | $17.97 | 19.4 | $20.71 | $16.75 | 19.1 | $28.46 | $23.02 | 19.1 |

| General Practice (GP) | 13.25 | 10.68 | 19.4 | 13.97 | 11.35 | 18.8 | 12.46 | 9.96 | 20.0 | 11.84 | 9.53 | 19.5 | 15.98 | 12.92 | 19.1 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 12.79 | 10.31 | 19.4 | 13.60 | 11.04 | 18.8 | 12.80 | 10.32 | 19.4 | 11.50 | 9.21 | 19.9 | 17.61 | 14.24 | 19.1 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 17.92 | 14.65 | 18.2 | 18.94 | 15.49 | 18.2 | 16.39 | 13.36 | 18.5 | 16.75 | 13.62 | 18.7 | 20.09 | 16.61 | 17.3 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | 26.70 | 21.73 | 18.6 | 24.85 | 20.32 | 18.2 | 27.01 | 21.50 | 20.4 | 22.85 | 18.37 | 19.6 | 34.07 | 28.39 | 16.7 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 24.67 | 20.42 | 17.2 | 31.64 | 25.13 | 20.6 | 22.57 | 18.32 | 18.8 | 21.94 | 18.36 | 16.3 | 23.88 | 20.41 | 14.5 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 51.61 | 41.26 | 20.1 | 60.77 | 47.44 | 21.9 | 46.41 | 37.49 | 19.2 | 42.89 | 34.62 | 19.3 | 63.68 | 51.37 | 19.3 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 34.32 | 26.99 | 21.4 | 37.73 | 29.23 | 22.5 | 37.02 | 28.28 | 23.6 | 30.13 | 23.50 | 22.0 | 33.80 | 27.73 | 18.0 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 64.87 | 53.92 | 16.9 | 61.41 | 49.88 | 18.8 | 69.31 | 57.73 | 16.7 | 63.92 | 53.31 | 16.6 | 66.99 | 56.94 | 15.0 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 68.90 | 54.67 | 20.7 | 69.54 | 54.70 | 21.3 | 80.11 | 63.38 | 20.9 | 56.32 | 45.07 | 20.0 | 76.54 | 60.90 | 20.4 |

| Urology (U) | 53.19 | 43.04 | 19.1 | 60.84 | 48.25 | 20.7 | 57.14 | 46.60 | 18.4 | 44.33 | 36.01 | 18.8 | 54.85 | 44.92 | 18.1 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pathology (P) | 5.80 | 4.87 | 16.0 | 8.85 | 7.35 | 16.9 | 4.82 | 4.18 | 13.3 | 5.72 | 4.76 | 16.8 | 6.56 | 5.51 | 16.0 |

| Radiology (R) | 20.89 | 17.58 | 15.8 | 24.36 | 20.13 | 17.4 | 17.52 | 14.90 | 15.0 | 19.47 | 16.32 | 16.2 | 25.32 | 21.58 | 14.8 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 10.44 | 8.77 | 16.0 | 10.00 | 8.59 | 14.1 | 9.27 | 7.88 | 15.0 | 10.18 | 8.61 | 15.4 | 12.13 | 9.94 | 18.1 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 21.98 | 17.21 | 21.7 | 19.48 | 15.36 | 21.1 | 26.42 | 19.25 | 27.1 | 23.15 | 18.75 | 19.0 | 24.09 | 19.10 | 20.7 |

| Multi-Specialty (M) | 27.29 | 22.27 | 18.4 | 24.75 | 20.11 | 18.7 | 30.38 | 24.75 | 18.5 | 23.82 | 19.31 | 18.9 | 26.53 | 21.81 | 17.8 |

| Unknown | 18.03 | 15.10 | 16.3 | 24.60 | 21.11 | 14.2 | 15.01 | 12.24 | 18.5 | 12.89 | 10.97 | 14.9 | 31.68 | 28.22 | 10.9 |

| All other (residual) | 40.57 | 31.91 | 21.3 | 41.01 | 31.88 | 22.3 | 37.40 | 29.49 | 21.1 | 35.23 | 27.75 | 21.2 | 51.84 | 41.25 | 20.4 |

For each specialty in both years, the West generally had the highest average submitted charge per service and the South the lowest. For example, in 1975 the average submitted charge per service for general surgeons was highest in the West ($49) and lowest in the South ($32); in 1977 the average submitted charge was again highest in the West ($64) and lowest in the South ($43). The pattern in the ranking of the regions by average submitted charge per service for each specialty did not change significantly from 1975 to 1977 except for ophthalmology, where the Northeast ranked first for average submitted charge in 1975 and fourth in 1977 (Table 10).

Table 10. U.S. Census Regions Ranked According to Average Submitted Charge Per Service for Aged Medicare Users, by Specialty, U.S., 1975 and 1977.

| Specialty | 1975 | 1977 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| NE | NC | South | West | NE | NC | South | West | |

| General Practice (GP) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Urology (U) | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pathology (P) | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Radiology (R) | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Multi-Specialty Group (M) | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

Reimbursements Per User

Reimbursement per user for all types of physicians' specialties combined was $247 in 1975 and $293 in 1977. As shown in Table 11, reimbursements per user each year were highest for persons who used services of general surgeons, orthopedic surgeons, and urologists. Lowest reimbursements per user were for services by podiatrists, dermatologists, and otologists/laryngologists/rhinologists.

Table 11. Average Reimbursement Per Aged User Under Medicare, by Specialty, U.S., 1975 and 1977.

| Specialty | Average Reimbursements Per User | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 1975 | 1977 | |

| All Specialties | $247 | $293 |

| General Practice (GP) | 76 | 83 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 60 | 76 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 113 | 133 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | 109 | 134 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 44 | 55 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 151 | 195 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 45 | 56 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 85 | 101 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 157 | 203 |

| Urology (U) | 145 | 182 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | 109 | 135 |

| Pathology (P) | 57 | 58 |

| Radiology (R) | 53 | 60 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 64 | 69 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 47 | 52 |

| Multi-Specialty Group (M) | 123 | 153 |

As observed earlier, user rates by specialty need to be interpreted with some care. For example, although reimbursements for users of chiropractic services were relatively substantial ($64 in 1975 and $69 in 1977), there were comparatively few such users. Consequently, reimbursements for chiropractors comprise a smaller fraction of total reimbursements than any other specialty, as will be discussed in the next section.

Reimbursement Per Enrollee

In 1975, a total of $122 per enrollee were reimbursed and in 1977, $153 per enrollee. Average reimbursement per enrollee and per user increased from 1975 to 1977 for every specialty except for general practitioners (Table 12).

Table 12. Average Reimbursement Per Aged Medicare Enrollee, by Specialty, U.S., 1975 and 1977.

| Specialty | Average Reimbursement Per Enrollee | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 1975 | 1977 | |

| All Specialties | $121.67 | $153.09 |

| General Practice (GP) | 16.62 | 15.66 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 1.61 | 3.95 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 24.63 | 30.31 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | 3.37 | 4.36 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 1.38 | 1.94 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 14.43 | 17.99 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 1.41 | 1.88 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 7.95 | 10.71 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 6.90 | 9.39 |

| Urology (U) | 6.59 | 8.55 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | 5.43 | 7.18 |

| Pathology (P) | 1.28 | 1.36 |

| Radiology (R) | 7.09 | 9.33 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 0.65 | 0.79 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 1.83 | 2.39 |

| Multi-Specialty Group (M) | 7.03 | 8.96 |

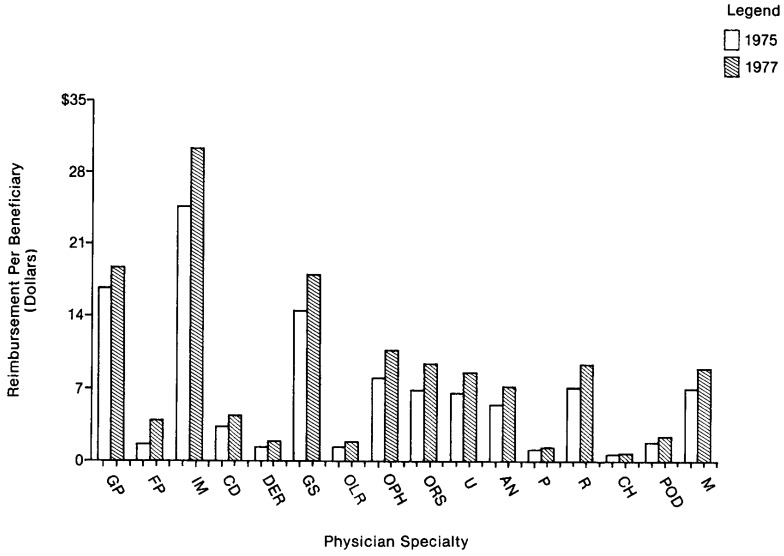

Analysis of the distribution of reimbursements per enrollee shows that the highest amount of reimbursements was for services by internists, at $24.63 in 1975 and $30.31 in 1977, and the lowest amount of reimbursements was for services by chiropractors, at $0.65 in 1975 and $0.79 in 1977. Figure 2 summarizes these data, showing the average reimbursement per enrollee for each specialty.

Figure 2. Reimbursement Per Beneficiary by Physician Specialty.

General Table IV gives total reimbursement and reimbursement per enrollee by physician specialty, and by age, sex, race, and census region. For all specialties combined, the amount of reimbursement per enrollee was generally higher for older age groups. In both 1975 and 1977 reimbursement per enrollee was about 15 percent higher for men than for women. With regard to race, in both years the rate of reimbursement for white persons was about 40 percent higher than for persons of all other races.

General Table IV. Medicare Beneficiaries: Total Reimbursements and Reimbursement per Enrollee by Physician Specialty, and by Age, Sex, Race and Census Region, 1975 and 1977.

| Reimbursements Per Enrollee | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| Specialty | Total (thousands) | U.S. Total | Age | Sex | Race | Census Region | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| 65-69 | 70-74 | 75-79 | 80-84 | 85 + | Men | Women | White | Other | NE | NC | South | West | |||

| 1975 | |||||||||||||||

| All Specialties | $2,651,834 | $121.67 | $99.64 | $124.01 | $133.18 | $145.70 | $141.40 | $130.47 | $115.72 | $126.28 | $89.49 | $135.00 | $103.24 | $109.72 | $156.34 |

| General Practice (GP) | 362,139 | 16.62 | 11.90 | 15.97 | 18.78 | 22.06 | 24.77 | 15.55 | 17.34 | 16.99 | 14.83 | 13.64 | 14.38 | 17.93 | 22.59 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 35,005 | 1.61 | 1.18 | 1.51 | 1.77 | 2.12 | 2.51 | 1.63 | 1.59 | 1.64 | 1.55 | 2.16 | 1.78 | 1.38 | 0.89 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 536,649 | 24.62 | 18.73 | 25.46 | 27.54 | 31.36 | 29.14 | 25.19 | 24.24 | 25.47 | 18.96 | 33.82 | 18.53 | 20.46 | 29.03 |

| Cardiovascular Disease | |||||||||||||||

| (CD) | 73,546 | 3.37 | 3.17 | 3.43 | 3.48 | 3.94 | 2.95 | 4.08 | 2.89 | 3.48 | 2.51 | 4.15 | 3.07 | 2.27 | 4.87 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 30,004 | 1.38 | 1.13 | 1.58 | 1.42 | 1.52 | 1.42 | 1.61 | 1.22 | 1.46 | 0.61 | 1.52 | 0.69 | 1.26 | 2.56 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 314,422 | 14.43 | 12.86 | 15.02 | 14.90 | 16.03 | 15.39 | 16.10 | 13.30 | 15.00 | 10.25 | 16.88 | 13.10 | 12.60 | 16.51 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 30,821 | 1.41 | 1.49 | 1.58 | 1.32 | 1.25 | 1.01 | 1.60 | 1.29 | 1.49 | 0.86 | 1.68 | 0.91 | 1.23 | 2.25 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 173,250 | 7.95 | 5.40 | 8.10 | 9.52 | 11.29 | 9.21 | 7.11 | 8.52 | 8.29 | 5.43 | 9.88 | 5.66 | 6.81 | 11.15 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 150,351 | 6.90 | 5.00 | 5.75 | 7.64 | 9.44 | 12.88 | 4.33 | 8.64 | 7.33 | 2.69 | 7.44 | 5.69 | 5.75 | 10.37 |

| Urology (U) | 143,579 | 6.59 | 5.07 | 7.07 | 7.64 | 8.01 | 6.67 | 13.20 | 2.11 | 6.85 | 5.13 | 7.71 | 5.07 | 5.76 | 9.10 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | 118,426 | 5.43 | 4.84 | 5.74 | 5.69 | 5.85 | 5.65 | 6.59 | 4.65 | 5.63 | 4.06 | 5.67 | 4.42 | 4.65 | 8.36 |

| Pathology (P) | 27,788 | 1.28 | 1.02 | 1.31 | 1.39 | 1.64 | 1.38 | 1.57 | 1.08 | 1.29 | 1.35 | 0.52 | 1.24 | 2.11 | 0.88 |

| Radiology (R) | 154,602 | 7.09 | 6.38 | 7.30 | 7.74 | 7.72 | 6.91 | 7.67 | 6.71 | 7.31 | 6.07 | 5.56 | 6.43 | 8.48 | 7.93 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 14,049 | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.21 | 0.64 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 1.18 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 39,878 | 1.83 | 1.25 | 1.76 | 2.19 | 2.46 | 2.62 | 1.08 | 2.34 | 1.87 | 1.69 | 3.38 | 0.93 | 1.26 | 2.10 |

| Multi-Specialty Group (M) | 153,101 | 7.03 | 6.40 | 7.20 | 7.85 | 6.91 | 7.27 | 7.96 | 6.39 | 7.30 | 5.07 | 2.44 | 9.54 | 5.93 | 12.01 |

| Unknown | 53,352 | 2.45 | 1.95 | 2.26 | 2.77 | 3.25 | 3.16 | 2.69 | 2.29 | 2.59 | 1.17 | 4.61 | 3.33 | 0.88 | 0.65 |

| All other (residual) | 240,874 | 11.05 | 11.17 | 12.25 | 10.93 | 10.30 | 8.11 | 11.91 | 10.47 | 11.60 | 7.06 | 13.31 | 8.04 | 10.44 | 13.91 |

| 1977 | |||||||||||||||

| All Specialties | 3,492,446 | 153.09 | 131.76 | 153.04 | 168.23 | 172.02 | 175.93 | 166.37 | 144.19 | 157.74 | 112.05 | 167.47 | 132.58 | 126.99 | 217.01 |

| General Practice (GP) | 357,279 | 15.66 | 11.78 | 14.43 | 17.47 | 20.10 | 24.22 | 14.97 | 16.12 | 15.99 | 13.00 | 12.70 | 15.28 | 14.09 | 23.87 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 90,009 | 3.95 | 3.12 | 3.54 | 4.48 | 5.16 | 5.49 | 3.63 | 4.16 | 4.05 | 3.11 | 3.81 | 3.24 | 5.02 | 3.23 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 691,452 | 30.31 | 24.51 | 29.76 | 34.10 | 36.52 | 37.39 | 30.38 | 30.26 | 30.98 | 25.20 | 39.33 | 23.58 | 25.22 | 37.95 |

| Cardiovascular Disease | |||||||||||||||

| (CD) | 99,443 | 4.36 | 4.05 | 4.58 | 4.50 | 4.83 | 3.90 | 5.45 | 3.63 | 4.47 | 3.01 | 5.95 | 2.76 | 2.88 | 7.48 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 44,291 | 1.94 | 1.69 | 1.95 | 2.17 | 2.21 | 2.01 | 2.37 | 1.65 | 2.08 | 0.52 | 2.05 | 0.94 | 1.69 | 3.95 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 410,401 | 17.99 | 16.38 | 18.29 | 19.49 | 19.24 | 18.25 | 20.33 | 16.43 | 18.49 | 13.27 | 21.08 | 16.20 | 14.96 | 22.30 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 42,952 | 1.88 | 2.19 | 2.07 | 1.78 | 1.34 | 1.15 | 2.35 | 1.57 | 1.96 | 1.04 | 2.13 | 1.31 | 1.48 | 3.27 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 244,210 | 10.71 | 7.70 | 10.60 | 13.47 | 13.55 | 12.61 | 10.01 | 11.17 | 11.13 | 6.99 | 12.17 | 8.17 | 9.10 | 15.92 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 214,185 | 9.39 | 7.14 | 8.36 | 10.08 | 11.56 | 16.70 | 6.23 | 11.50 | 9.98 | 3.88 | 10.25 | 7.62 | 7.68 | 14.39 |

| Urology (U) | 195,109 | 8.55 | 7.40 | 9.13 | 9.74 | 8.89 | 8.19 | 17.38 | 2.64 | 8.77 | 7.13 | 9.59 | 6.57 | 7.51 | 12.39 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | 163,844 | 7.18 | 6.74 | 7.52 | 7.40 | 7.02 | 7.64 | 8.85 | 6.07 | 7.43 | 4.83 | 7.86 | 5.62 | 5.44 | 12.20 |

| Pathology (P) | 31,054 | 1.36 | 1.18 | 1.33 | 1.54 | 1.46 | 1.64 | 1.61 | 1.19 | 1.39 | 1.13 | 0.43 | 0.98 | 2.50 | 1.19 |

| Radiology (R) | 212,798 | 9.33 | 8.67 | 9.57 | 10.19 | 9.59 | 8.88 | 10.44 | 8.58 | 9.54 | 7.55 | 8.01 | 8.55 | 9.84 | 11.66 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 18,006 | 0.79 | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0.73 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.22 | 0.59 | 0.76 | 0.56 | 1.59 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 54,491 | 2.39 | 1.78 | 2.25 | 2.65 | 3.11 | 3.56 | 1.43 | 3.03 | 2.42 | 2.12 | 4.18 | 1.37 | 1.58 | 2.98 |

| Multi-Specialty Group (M) | 204,449 | 8.96 | 8.05 | 9.53 | 9.85 | 9.41 | 8.19 | 10.05 | 8.24 | 9.13 | 7.44 | 3.85 | 14.02 | 4.12 | 17.68 |

| Unknown | 49,035 | 2.15 | 1.70 | 2.03 | 2.28 | 2.53 | 3.41 | 2.36 | 2.01 | 2.28 | 0.98 | 3.35 | 4.18 | 0.26 | 0.66 |

| All other (residual) | 369,441 | 16.19 | 16.75 | 17.25 | 16.23 | 14.99 | 12.44 | 17.81 | 15.11 | 16.81 | 10.62 | 20.15 | 11.46 | 13.06 | 24.31 |

In 1975 and 1977, the West had the highest rate of reimbursement per enrollee ($156 and $217) reflecting the high number of reimbursed users and the high reimbursement per user. The North Central region had the lowest reimbursement per enrollee in 1975 ($103) and the South had the lowest in 1977 ($127).

Total Reimbursements by Specialty

For all physicians' specialties combined, total Medicare reimbursements were $2,652 million in 1975 and $3,492 million in 1977 as reported in the Bill Summary System (Table 13). Of the total Medicare reimbursements, about 20 percent went for services of internists each year. Reimbursements for services by general practitioners comprised 14 percent in 1975; they comprised 10 percent in 1977, with services by family practitioners accounting for almost 3 percent. Reimbursements to general surgeons comprised about 12 percent each year. Internal medicine, general practice and general surgery shared ranks 1, 2, and 3 in the percent of total reimbursements each year. As noted earlier, estimates of reimbursements for anesthesiology, pathology, and radiology are biased downward, especially so for pathology and radiology, but we cannot provide total reimbursement for either specialty. The percent distribution and rankings of total amounts of reimbursements by specialty were similar for 1975 and 1977 except for family practice, which doubled in percent of reimbursement (Table 13).

Table 13. Reimbursements for Aged Medicare Users, Percent Distribution, and Rank Order by Specialty, U.S., 1975 and 1977.

| 1975 | 1977 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Specialty | Total Reimbursement (millions) | Percent Distribution | Rank | Total Reimbursement (millions) | Percent Distribution | Rank |

| All Specialties | $2,652 | 100.0 | — | $3,492 | 100.0 | — |

| General Practices (GP) | 362 | 13.7 | 2 | 357 | 10.2 | 3 |

| Family Practice (FP) | 35 | 1.3 | 12 | 90 | 2.6 | 11 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) | 537 | 20.3 | 1 | 691 | 19.8 | 1 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | 74 | 2.8 | 10 | 99 | 2.8 | 10 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 30 | 1.1 | 14 | 44 | 1.3 | 13 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 314 | 11.8 | 3 | 410 | 11.7 | 2 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 31 | 1.2 | 13 | 43 | 1.2 | 14 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 173 | 6.5 | 4 | 244 | 7.0 | 4 |

| Orthopedic Surgery (ORS) | 150 | 5.7 | 7 | 214 | 6.1 | 5 |

| Urology (U) | 144 | 5.4 | 8 | 195 | 5.6 | 8 |

| Anesthesiology (AN) | 118 | 4.5 | 9 | 164 | 4.7 | 9 |

| Pathology (P) | 28 | 1.1 | 15 | 31 | 0.9 | 15 |

| Radiology (R) | 154 | 5.8 | 5 | 213 | 6.1 | 6 |

| Chiropractic (CH) | 14 | 0.5 | 16 | 18 | 0.5 | 16 |

| Podiatry (POD) | 40 | 1.5 | 11 | 54 | 1.6 | 12 |

| Multi-specialty Group (M) | 153 | 5.8 | 6 | 204 | 5.8 | 7 |

Six specialties, although not among those with the greatest number of reimbursed users or services, received reimbursements that were greater than the reimbursements of some of the specialties shown in Table 13. The average submitted charge per service was relatively high for these selected specialties (Table 14).

Table 14. Reimbursements for Aged Medicare Users, Percent Distribution, and Average Submitted Charge Per Service for Six Selected Specialties, U.S., 1975 and 1977.

| Specialty | 1975 | 1977 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Total Reimbursement (million) | Percent Distribution | Average Submitted Charge per Service | Total Reimbursement (millions) | Percent Distribution | Average Submitted Charge per Service | |

| All Specialties | $2,652 | 100.0 | $19.47 | $3,492 | 100.0 | $24.06 |

| Thoracic Surgery | 63 | 2.4 | 96.53 | 102 | 2.9 | 140.03 |

| Neurological Surgery | 25 | 0.9 | 61.89 | 36 | 1.0 | 89.32 |

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 25 | 0.9 | 25.47 | 31 | 0.9 | 32.52 |

| Neurology | 22 | 0.8 | 27.13 | 32 | 0.9 | 33.79 |

| Psychiatry | 20 | 0.8 | 23.97 | 27 | 0.8 | 29.76 |

| Gastroenterology | 16 | 0.6 | 25.01 | 30 | 0.9 | 33.03 |

Combinations of Physicians Seen By Medicare Enrollees

As noted earlier, a study was undertaken by Aiken et al. (1979) from log diaries kept by physicians to determine the extent to which specialist physicians participated in principal care. The key requirement for principal care in that study was “an assumption by the physician of continuing responsibility for the patient and a commitment to meeting the majority of the patient's medical needs, irrespective of their nature.” Each specialty group was studied to determine what percentage of encounters were for principal care. They found that about 80 percent of encounters with general and family practitioners were for principal care. They also observed that there was a surprisingly high percentage of specialist physician encounters providing principal care, ranging from about 20 percent to 72 percent. The percentage was high for pediatrics (72 percent), internal medicine (62 percent), obstetrics and gynecology (65 percent), and cardiovascular disease (58 percent).

In this study, we were interested in determining the mix of physicians serving each Medicare user in the sample. Counts were made of the number of reimbursed persons in 1977, using each possible combination of general practice, eleven selected specialties, and the multi-specialty category.3 Table 15 shows the 50 most frequent combinations, ranked in order of frequency. These 50 combinations accounted for 64.8 percent of the users. The two most common patterns, far exceeding all others, were the use of physicians in general practice only (11.2 percent of the enrollees) or the use of internists only (10.1 percent of the enrollees). Use of family practitioners only ranked fourth (2.8 percent of the enrollees).

Table 15. The Fifty Most Frequent Combinations of Physicians Seen by Medicare Users, U.S., 1977.

| Rank | Physician Combination | Number of Persons Using Physician Combination | Percent Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| All possible combinations | 11,934,000 | 100.0 | |

| Fifty most frequent | 7,732,200 | 64.8 | |

| 1 | GP only | 1,330,200 | 11.2 |

| 2 | IM only | 1,199,300 | 10.1 |

| 3 | IM w R | 403,500 | 3.4 |

| 4 | FP only | 334,700 | 2.8 |

| 5 | IM w OPH | 333,900 | 2.8 |

| 6 | M only | 328,100 | 2.8 |

| 7 | GS only | 280,900 | 2.3 |

| 8 | GP w R | 280,400 | 2.3 |

| 9 | GP w OPH | 250,700 | 2.1 |

| 10 | GP w IM | 231,500 | 1.9 |

| 11 | OPH only | 202,900 | 1.7 |

| 12 | R only | 186,000 | 1.6 |

| 13 | IM w GS | 138,300 | 1.2 |

| 14 | GP w IM w R | 121,400 | 1.0 |

| 15 | GP w GS | 118,200 | 1.0 |

| 16 | IM w OPH w R | 99,800 | 0.8 |

| 17 | GS w R | 83,600 | 0.7 |

| 18 | ORS only | 83,300 | 0.7 |

| 19 | CD only | 82,400 | 0.7 |

| 20 | GP w M | 82,100 | 0.7 |

| 21 | IM w R | 81,400 | 0.7 |

| 22 | IM w ORS | 81,200 | 0.7 |

| 23 | IM w GS w R | 78,800 | 0.7 |

| 24 | GP w FP | 76,600 | 0.6 |

| 25 | IM w U | 72,600 | 0.6 |

| 26 | IM w OLR | 69,100 | 0.6 |

| 27 | GP w IM w OPH | 67,500 | 0.6 |

| 28 | FP w R | 67,100 | 0.6 |

| 29 | FP w OPH | 63,700 | 0.5 |

| 30 | U only | 63,100 | 0.5 |

| 31 | R w M | 54,400 | 0.4 |

| 32 | GP w OPH w R | 51,200 | 0.4 |

| 33 | GP w ORS | 50,100 | 0.4 |

| 34 | GP w U | 49,900 | 0.4 |

| 35 | IM w ORS w R | 49,500 | 0.4 |

| 36 | OPH w M | 47,300 | 0.4 |

| 37 | GP w GS w R | 46,700 | 0.4 |

| 38 | GS w OPH | 45,900 | 0.4 |

| 39 | GP w OLR | 45,500 | 0.4 |

| 40 | FP w IM | 41,800 | 0.3 |

| 41 | OLR only | 41,100 | 0.3 |

| 42 | GP w IM w GS | 38,500 | 0.3 |

| 43 | IM w OLR w OPH | 37,700 | 0.3 |

| 44 | IM w U w R | 37,000 | 0.3 |

| 45 | IM w GS w A w R | 36,200 | 0.3 |

| 46 | IM w GS w OPH | 35,700 | 0.3 |

| 47 | IM w R w M | 33,700 | 0.3 |

| 48 | IM w GS w A | 33,400 | 0.3 |

| 49 | IM w CD | 33,300 | 0.3 |

| 50 | ORS w R | 33,000 | 0.3 |

NOTE: Abbreviations used are: general practice (GP); family practice (FP); internal medicine (IM); cardiovascular disease (CD); general surgery (GS); otology, laryngology, rhinology (OLR); ophthalmology (OPH); orthopedic surgery (ORS); urology (U); anesthesiology (A); radiology (R); multispecialty group (M). w = with.

Of all the combinations with cardiologists the most dominant pattern (ranking 19th) was the one in which the enrollee saw only the cardiologist. This was also true of those who saw general surgeons (ranking 7th), and orthopedic surgeons (ranking 18th).

Unexpectedly, the twelfth most common pattern was enrollees using the services of only radiologists during the year. More information is needed to understand this finding. One possible explanation is the continuing use of the services of a radiologist for therapeutic radiologic treatment of cancer.

The pattern of using the services of only ophthalmologists was the eleventh most frequent; the pattern of using the services of only urologists was the 30th most frequent, and using the services of only the specialty group otology, laryngology, rhinology was the 41st most frequent. It is interesting to note that enrollees using only one type of physician accounted for 33 percent of the total beneficiaries. It should be pointed out that data shown in Table 15 are for a 12-month service period (January 1, 1977-December 31, 1977). Some enrollees who are included here as seeing only a specialist may have seen a primary care physician in the month or two preceding or following this period under study.

As expected, frequent patterns of care were enrollees seeing internists in combination with another speciality or general practitioners in combination with a speciality. For example, frequent patterns were internal medicine with radiology (ranking 3rd), and general practice with ophthalmology (ranking 9th).

The combination of general practice with family practice (ranking 24th) is very likely due to the switchover during the year of the physician's designation from general practice to family practice. Also, the pattern of using a “multi-specialty” group only which is a mix of more than one physician specialty caused it to rank very high (6th).

In Table 16, all possible combinations are grouped to show what percentage of reimbursed Medicare persons used the services of specialists during the year without seeing a primary care physician, that is, without seeing a physician in general practice, family practice, or internal medicine.

Table 16. Number of Aged Persons Reimbursed Under Medicare, by Combination of Specialty Used, U.S., 1977.

| Combinations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Specialty | Total Persons Reimbursed | Users of Specialty Only or in Combination with Other Specialties | All Other Users | |||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |

| All Specialties | 11,934,000 | 100.0 | 1,823,300 | 15.3 | 10,100,700 | 84.7 |

| Cardiovascular Disease (CD) | 742,300 | 100.0 | 257,000 | 34.6 | 485,300 | 65.4 |

| Dermatology (DER) | 804,400 | 100.0 | 197,700 | 24.6 | 606,700 | 75.4 |

| General Surgery (GS) | 2,108,700 | 100.0 | 683,400 | 32.4 | 1,425,300 | 67.6 |

| Oto/Laryn/Rhin (OLR) | 761,000 | 100.0 | 165,800 | 21.8 | 595,200 | 78.2 |

| Ophthalmology (OPH) | 2,414,100 | 100.0 | 542,300 | 22.5 | 1,871,800 | 77.5 |