Abstract

Health care spending in the United States more than tripled between 1971 and 1981, increasing from $83 billion to $287 billion. This growth in health sector spending substantially outpaced overall growth in the economy, averaging 13.2 percent per year compared to 10.5 percent for the gross national product (GNP). By 1981, one out of every ten dollars of GNP was spent on health care, compared to one out of every thirteen dollars of GNP in 1971. If current trends continue and if present health care financing arrangements remain basically unchanged, national health expenditures are projected to reach approximately $756 billion in 1990 and consume roughly 12 percent of GNP.

The focal issue in health care today is cost and cost Increases. The outlook for the 1980's is for continued rapid growth but at a diminished rate. The primary force behind this moderating growth is projected lower inflation. However, real growth rates are also expected to moderate slightly. The chief factors influencing the growth of health expenditures in the eighties are expected to be aging of the population, new medical technologies, increasing competition, restrained public funding, growth in real income, increased health manpower, and a deceleration in economy-wide inflation.

Managers, policy makers and providers in the health sector, as in all sectors, must include in today's decisions probable future trends. Inflation, economic shocks, and unanticipated outcomes of policies over the last decade have intensified the need for periodic assessments of individual industries and their relationship to the macro economy. This article provides such an assessment for the health care industry. Baseline current-law projections of national health expenditures are made to 1990.

Highlights

Highlights from this study include:

Economy-wide inflation is assumed to moderate in the 1980's resulting in a deceleration in health expenditure growth.

National health expenditures are projected to increase at an average annual rate of 11 to 12 percent for the period 1981-1990, a decline from the 13.2 percent average annual growth in the 1971-1981 interval.

Real GNP is assumed to increase faster in the 1982-1990 period than in the previous 8-year interval resulting in upward pressure for growth in real health spending.

Growth in total systems cost (personal health expenditures) per capita is projected to slow to an average annual rate of 10.6 percent for the period 1981-1990, a 1.7 percentage point decline in the growth rate from 1971 to 1981 (12.3 percent).

Per capita expenditures for 1990 are projected to be approximately $3000 for total health care, $1340 for hospital care, and $560 for physician services.

Total public spending for health care is projected to reach $325 billion by 1990, of which the Federal government will finance approximately 71 percent. Total private spending is expected to reach $431 billion in 1990 or approximately 57 percent of all health expenditures.

The population 75 years of age and over is projected to increase four times faster than the population of persons under age 65, leading to upward pressure on expenditure growth.

The institutional care share of personal health expenditures will increase and by 1990 hospital and nursing home care are expected to consume approximately 60 percent of personal health care spending.

The number of active physicians is projected to increase at an average annual rate of 2.7 percent in the projection period, a rate of increase triple that of population growth.

These projections are an evolution of historical trends and assume no abrupt or significant departure from current law. The key assumption is that the present extensive third party payment system will remain in place.

Other evolving patterns significant to the health care sector for the 1980's are:

Continued growth in new and expensive diagnostic and therapeutic technologies.

Slackening in growth of public financing for social programs.

Increased rivalry and competition within and among various segments of the health industry, taking many forms of price and nonprice competition such as: improved quality of services and products, expanded markets, increased advertising and greater substitution of services and goods (Porter, 1980). This increases the need to plan and adapt to changes in the health care sector.

The purpose of this baseline projection is to provide an evolution of health care spending under current law. This is a trend, or smooth growth projection scenario with focus on average annual rates of change.

Historical patterns in health spending are studied over three basic time intervals: 1950 to 1981, 1965 to 1981, and 1971 to 1981. The projection intervals are the short term, 1981 to 1983; the midterm, 1983 to 1985; and the long term, 1985 to 1990. The entire projection horizon, 1981 to 1990, is also examined.

We have developed a model which incorporates economic, actuarial, statistical, demographic and judgmental factors into a single integrated framework. There are four major interrelated components of the model: 1) a five-factor model of expenditures, 2) supply variables, 3) a channel of finance module and 4) a net cost of private health insurance/program administration cost module.

First, the assumptions upon which the projections are based are presented. An overview of projections for total health costs and sources of financing is given. We then examine health care expenditure growth from an international vantage point. Some theories on the causes of health expenditure growth are discussed. Projections of total systems cost per capita are presented. Finally, projections for particular health care sectors are presented. In addition, there are technical notes on methodology and data sources available from the author.

Assumptions for Current-Law Projections

These current-law projections are based on the fundamental assumption that historical trends and relationships will continue into the future. Further, it is assumed that:

The competitive structure, conduct, and performance of the health care delivery system will continue to evolve along patterns followed during the historical period 1965 through 1981.

No Federally mandated pro-competition health insurance plan or cost containment program, including prospective payment for all payers, will be in effect. This is an assumption of the current law projection, not a prediction.

No major, new, publicly-financed program of medical care such as catastrophic national health insurance will be legislated. This is an assumption of the current law projection, not a prediction.

No major technological breakthrough in treatment of acute and chronic illnesses that would significantly alter evolving patterns of morbidity and mortality will occur.

Use of medical care, including intensity of services per case (derived in part from new technologies) will continue to grow in accordance with historical relationships and trends.

Medical care prices will vary with the implicit price deflator for the GNP1 according to relationships established in the historical period studied.

Population will grow as projected by the Office of the Actuary, Social Security Administration (Tables A-1 through A-3).

Health manpower will increase as projected by the Bureau of Health Professions (Table A-4).

The GNP and the implicit price deflator for the Gross National Product will grow as projected in economic assumptions incorporated in the Board of Trustees, Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Trust Funds, 1982 Annual Report, alternative II-B (intermediate) economic assumptions (Table A-1).

Benefit outlays for Medicare and total community hospital inpatient expenses and use will grow as projected in the 1982 Annual Report of the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund and the 1982 Annual Report of the Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund. Projected growth rates were modified by the Medicare actuaries to account for factors and trends evident as of mid-1982.

Aggregate Federal Medicaid benefit outlay increases are consistent with the Health Care Financing Administration projections.

Provisional estimates of the effects of the Tax and Equity Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982 (P.L. 92-248)(Health Care Financing Administration, September 13, 1982) have been factored into the projection estimates.

Table A-1. Historical Estimates and Projections of Gross National Product, Inflation, and Population, Selected Years, 1950-1990.

| Calendar Year | Gross National1 Product (billions) | Real Gross1 National Product (1972 dollars, billions) | Implicit1 Price Deflator, Gross National Product (1972= 100.0) | Consumer Price1 2 Index-All Items Wage Earners (1967=100.0) | Total3 Population (Thousands, July 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Historical Estimates | |||||

|

|

|||||

| 1950 | $ 286.5 | $ 534.8 | 53.5 | 72.1 | 154,675 |

| 1955 | 400.0 | 657.5 | 60.8 | 80.2 | 168,385 |

| 1960 | 506.5 | 737.2 | 68.7 | 88.7 | 183,834 |

| 1965 | 691.0 | 929.3 | 74.4 | 94.5 | 197,876 |

| 1966 | 756.0 | 984.8 | 76.8 | 97.2 | 200,149 |

| 1967 | 799.6 | 1,011.4 | 79.0 | 100.0 | 202,334 |

| 1968 | 873.4 | 1,058.1 | 82.5 | 104.2 | 204,362 |

| 1969 | 944.0 | 1,087.6 | 86.8 | 109.8 | 206,369 |

| 1970 | 992.7 | 1,085.6 | 91.4 | 116.3 | 208,612 |

| 1971 | 1,077.6 | 1,122.4 | 96.0 | 121.3 | 211,256 |

| 1972 | 1,185.9 | 1,185.9 | 100.0 | 125.3 | 213,569 |

| 1973 | 1,326.4 | 1,254.3 | 105.7 | 133.1 | 215,665 |

| 1974 | 1,434.2 | 1,246.3 | 115.1 | 147.7 | 217,683 |

| 1975 | 1,549.2 | 1,231.7 | 125.7 | 161.2 | 219,890 |

| 1976 | 1,718.0 | 1,298.2 | 132.3 | 170.5 | 221,993 |

| 1977 | 1,918.3 | 1,369.7 | 140.0 | 181.5 | 224,225 |

| 1978 | 2,163.8 | 1,438.5 | 150.4 | 195.4 | 226,583 |

| 1979 | 2,417.8 | 1,479.4 | 163.4 | 217.7 | 229,061 |

| 1980 | 2,633.1 | 1,474.0 | 178.6 | 247.0 | 231,679 |

| 1981 | 2,937.7 | 1,502.6 | 195.5 | 272.3 | 233,988 |

| Projections | |||||

|

|

|||||

| 1983 | 3,468.9 | 1,555.2 | 223.0 | 311.2 | 238,219 |

| 1985 | 4,207.4 | 1,654.8 | 254.3 | 356.2 | 242,526 |

| 1990 | 6,304.1 | 1,918.5 | 328.6 | 458.9 | 253,387 |

| Selected Periods | Average Annual Rates of Increase | ||||

|

|

|

||||

| 1950-1955 | 6.9% | 4.2% | 2.6% | 2.2% | 1.7% |

| 1955-1960 | 4.8 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 1.8 |

| 1960-1965 | 6.4 | 4.7 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.5 |

| 1965-1970 | 7.5 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 1.1 |

| 1970-1975 | 9.3 | 2.6 | 6.5 | 6.3 | 1.1 |

| 1975-1980 | 11.2 | 3.7 | 7.3 | 8.9 | 1.0 |

| 1980-1985 | 9.8 | 2.3 | 7.3 | 7.6 | 0.9 |

| 1985-1990 | 8.4 | 3.0 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 0.9 |

| 1981-1983 | 8.7 | 1.7 | 6.8 | 6.9 | 0.9 |

| 1983-1985 | 10.1 | 3.2 | 6.8 | 7.0 | 0.9 |

| 1970-1980 | 10.2 | 3.1 | 6.9 | 7.8 | 1.1 |

| 1980-1990 | 9.1 | 2.7 | 6.3 | 6.4 | 0.9 |

| 1971-1981 | 10.5 | 3.0 | 7.4 | 8.4 | 1.0 |

| 1981-1990 | 8.9 | 2.8 | 5.9 | 6.0 | 0.9 |

Historical estimates are reported in Economic Report of the President, February 1982. Projection growth rates are from Board of Trustees Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance Trust Funds, 1982 Annual Report, Washington, April 1, 1982. II-B assumptions were used. The growth rates for 1982 for GNP and inflation were slightly modified to reflect partial year data available as of mid 1982. The 1990 GNP used in this projection is within 3 percent of the GNP forecast by the private consulting firm of Data Resources, Inc. See Review of the U.S. Economy, October 1982 (forecast: TREND LONG 1082).

The CPI is shown for comparison only. The implicit price deflator for GNP is used in the projection process to reflect cost pressures external to health care industry.

Historical estimates of population are based on data from the Bureau of Census. The estimates are reported in Robert M. Gibson and Daniel R. Waldo, “National Health Expenditures, 1981,” Health Care Financing Review, September 1982, pp. 1-36. Projected growth rates in population are from the Office of the Actuary, Social Security Area Population Projections, 1981, Actuarial Study No. 85, SSA Pub. No. 11-11532, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, July 1981. Alternative II (intermediate) assumptions for population growth were used.

Table A-3. Proportions of the Population Ages Less than 65, 65 +, and 75 +, Selected Years, 1960-1990.

| Calendar Year | Total All Ages | Less than 65 | Equal to or Greater Than Age 65 | Equal to or Greater Than Age 75 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Historical Estimates | ||||

|

|

||||

| 1960 | 100.0% | 90.9% | 9.1% | 3.1% |

| 1965 | 100.0 | 90.7 | 9.3 | 3.4 |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 90.3 | 9.7 | 3.8 |

| 1971 | 100.0 | 90.2 | 9.8 | 3.9 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 89.6 | 10.4 | 4.1 |

| 1979 | 100.0 | 89.0 | 11.0 | 4.3 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 88.9 | 11.1 | 4.4 |

| 1981 | 100.0 | 88.7 | 11.3 | 4.5 |

| Projections | ||||

|

|

||||

| 1983 | 100.0 | 88.5 | 11.5 | 4.7 |

| 1985 | 100.0 | 88.1 | 11.9 | 4.9 |

| 1990 | 100.0 | 87.4 | 12.6 | 5.4 |

Derived from data in Office of the Actuary (1981). Alternative II (intermediate) assumptions for population growth were used.

Table A-4. Historical Estimates and Projections of Active Physicians and Dentists, Selected Years, 1950-19901.

| Year | Number of Active Physicians (as of December 31) |

Number of Active Dentists (as of December 31) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||

| Historical Estimates | Total | M.D.'s | D.O.'s | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1950 | 219,900 | 209,000 | 10,900 | 79,190 |

| 1955 | 240,200 | 228,600 | 11,600 | 84,370 |

| 1960 | 259,400 | 247,300 | 12,200 | 90,120 |

| 1965 | 288,700 | 277,600 | 11,1002 | 95,900 |

| 1970 | 323,200 | 311,200 | 12,000 | 102,220 |

| 1971 | 334,400 | 322,000 | 12,400 | 103,350 |

| 1975 | 378,600 | 364,500 | 14,100 | 112,020 |

| 1980 | 449,500 | 432,400 | 17,100 | 126,240 |

| 1981 | 464,000 | 446,000 | 18,000 | 129,330 |

| Projections | ||||

|

|

||||

| 1983 | 493,100 | 473,500 | 19,700 | 135,670 |

| 1985 | 523,900 | 502,000 | 21,900 | 141,500 |

| 1990 | 591,200 | 563,300 | 27,900 | 154,760 |

| Selected Periods | Average Annual Percent Increases | |||

|

|

|

|||

| 1950-1955 | 1.8% | 1.8% | 1.3% | 1.3% |

| 1955-1960 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| 1960-1965 | 2.2 | 2.3 | −1.92 | 1.3 |

| 1965-1970 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 1.3 |

| 1970-1975 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 1.9 |

| 1975-1980 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 2.4 |

| 1980-1985 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 5.1 | 2.3 |

| 1985-1990 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 5.0 | 1.8 |

| 1970-1980 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 2.1 |

| 1980-1990 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 5.0 | 2.1 |

| 1981-1983 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 4.6 | 2.4 |

| 1983-1985 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 5.4 | 2.1 |

| 1981-1990 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 5.0 | 2.0 |

| 1971-1981 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 2.3 |

Division of Health Professions Analysis, Bureau of Health Professions, Third Report to the President and Congress on the Status of Health Professions Personnel in the United States, Health Resources Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, January 1982.

The decline in the number of active D.O.'s between 1960 and 1965 reflects the granting of approximately 2,400 M.D. degrees to osteopathic physicians who had graduated from the University of California College of Medicine at Irvine. These physicians are included with active M.D.'s beginning in 1962.

The short-term outlook for the economy for the period 1981 to 1983, compared to the period 1979 to 1981, can be characterized by a substantial deceleration in inflation and a rebound in real growth in the economy in 1983 (Table 1). Real GNP increased at an average annual rate of 0.8 percent for the period 1979 to 1981. It is expected to increase at an average annual rate of 1.7 percent for the period 1981-1983 reflecting negative growth in 1982, but a 4.2 percent increase in 1983. The GNP deflator, an economy-wide measure of inflation, is expected to increase at an average annual rate of 6.8 percent for the period 1981 to 1983, compared to a 9.4 percent annual rate for the 1979-1981 period.

Table 1. National Health Expenditures by Source of Funds and Percent of Gross National Product, Selected Calendar Years, 1950-1990.

| National Health Expenditures | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Calendar Year | Gross National Product (billions) | Total | Private | Public | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Amount (billions) | Per Capita | Percent of GNP | Amount (billions) | Percent of Total | Total | Federal | State & Local | |||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Amount (billions) | Percent of Total | Amount (billions) | Percent of Total | Amount (billions) | Percent of Total | |||||||

| Historical1 | ||||||||||||

| 1950 | $ 286.5 | $ 12.7 | $ 82 | 4.4% | $ 9.2 | 72.8% | $ 3.4 | 27.2% | $ 1.6 | 12.8% | $ 1.8 | 14.4% |

| 1960 | 506.5 | 26.9 | 146 | 5.3 | 20.3 | 75.3 | 6.6 | 24.7 | 3.0 | 11.2 | 3.6 | 13.5 |

| 1970 | 992.7 | 74.7 | 358 | 7.5 | 46.9 | 62.8 | 27.8 | 37.2 | 17.7 | 23.7 | 10.1 | 13.6 |

| 1971 | 1,077.7 | 83.3 | 394 | 7.7 | 51.6 | 62.0 | 31.7 | 38.0 | 20.3 | 24.4 | 11.3 | 13.6 |

| 1975 | 1,549.2 | 132.7 | 604 | 8.6 | 76.5 | 57.7 | 56.2 | 42.3 | 37.1 | 27.9 | 19.1 | 14.4 |

| 1979 | 2,417.8 | 215.0 | 938 | 8.9 | 124.4 | 57.9 | 90.6 | 42.1 | 61.0 | 28.4 | 29.5 | 13.7 |

| 1980 | 2,633.1 | 249.0 | 1,075 | 9.5 | 143.6 | 57.7 | 105.4 | 42.3 | 71.1 | 28.5 | 34.3 | 13.8 |

| 1981 | 2,937.7 | 286.6 | 1,225 | 9.8 | 164.1 | 57.3 | 122.5 | 42.7 | 83.9 | 29.3 | 38.6 | 13.5 |

| Projected | ||||||||||||

| 1983 | 3,468.9 | 362.3 | 1,521 | 10.4 | 211.2 | 58.3 | 151.1 | 41.7 | 104.2 | 28.8 | 46.9 | 12.9 |

| 1985 | 4,207.4 | 456.4 | 1,882 | 10.8 | 268.2 | 58.8 | 188.1 | 41.2 | 131.5 | 28.8 | 56.6 | 12.4 |

| 1990 | 6,304.1 | 755.6 | 2,982 | 12.0 | 430.9 | 57.0 | 324.7 | 43.0 | 231.6 | 30.7 | 93.1 | 12.3 |

Historical estimates are from Robert M. Gibson and Daniel R. Waldo, “National Health Expenditures, 1981,” Health Care Financing Review, September, 1982.

For the midterm period 1983-1985, GNP is projected to increase at an average annual rate of 10.1 percent, with economy-wide prices increasing at an average rate of 6.8 percent and real GNP increasing at an average rate of 3.2 percent. The GNP deflator is expected to increase at an average annual rate of 5.3 percent, and real GNP at a 3.0 percent rate for the 1985-1990 interval.

For the entire projection period 1981-1990, the GNP deflator is expected to increase at an average annual rate of 5.9 percent. During the last decade, 1971-1981, the GNP deflator increased at an average annual rate of 7.4 percent. Thus significant deceleration of inflation is assumed. Real GNP is expected to increase at an average annual rate of 2.8 percent for the 1981-1990 period. Nominal GNP is expected to increase at an average annual rate of 8.9 percent over the 1981-1990 horizon, reflecting the deceleration in inflation.

A shift in the age composition of the population is one factor which will cause health expenditures to rise in the 1980's. Use of medical care by the aged population is disproportionate to their numbers. The number of persons 75 years of age and over is projected to increase at an average rate of 3.1 percent in the period 1981-1990 compared to an increase of .7 for the nonaged population (Table A-2). During the 1971-1981 period, the growth rates were 2.4 percent and 0.7 percent respectively. The proportion of the total population 65 years of age and over will rise from 11.3 percent in 1981 to 12.6 percent in 1990 (Table A-3). Total population is projected to increase at an average annual rate of 0.9 percent from 1981 to 1990.

Table A-2. Average Annual Percent Increases in Numbers of Persons of Ages Less than 65,65 +, and 75 +, Selected Periods, 1960-19901.

| Selected Periods | Less Than Age 65 | Equal to or Greater Than Age 65 | Equal to or Greater Than Age 75 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1960-1965 | 1.4% | 2.0% | 3.6% |

| 1965-1970 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 3.4 |

| 1970-1975 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| 1975-1980 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| 1980-1985 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 3.1 |

| 1985-1990 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 3.0 |

| 1960-1981 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 2.9 |

| 1965-1981 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 2.7 |

| 1971-1981 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| 1981-1983 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| 1983-1985 | 0.7 | 2.4 | 3.5 |

| 1981-1990 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 3.1 |

Derived from data in Office of the Actuary (1981). Alternative II (intermediate) assumptions for population growth were used.

Physicians are the key decision makers in the health sector. The number of active physicians is projected to grow from 464,000 in 1981 to 591,000 in 1990 (Table A-4), an aggregate increase of 27 percent, or more than three times the projected aggregate population growth.

The number of active dentists is projected to increase from 129,000 in 1981 to 155,000 in 1990, a 20-percent increase (Table A-4). This increase is approximately 2.5 times faster than aggregate population growth. As is the case with physicians, the growth in the number of dentists will decelerate during the 1980's declining from the peak growth rate years of 1975-1980 (Table A-4).

Overview of Projections

Total national health expenditures rose from $42 billion in 1965 to $287 billion in 1981, an average annual rate of growth of 12.8 percent (Table 1 and Table A-5). This rate implies a doubling of health spending every 5.8 years. There is variation around this average rate of increase. The lowest annual percent increase in this period was 10.3 percent in 1973, during the Economic Stabilization Program (ESP). The highest annual percent increase in this period was 15.8 percent in 1980.

Table A-5. National Health Expenditures by Source of Funds and Percent of Gross National Product, Selected Calendar Years, 1950-1990.

| Calendar Year | Gross National Product (billions) | National Health Expenditures | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total | Private | Public | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Total | Federal | State & Local | ||||||||||

| Amount (billions) | Per Capita | Percent of GNP | Amount (billions) | Percent of Total | Amount (billions) | Percent of Total | Amount (billions) | Percent of Total | Amount (billions) | Percent of Total | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Historical1 | ||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| 1950 | $286.5 | $ 12.7 | $ 82 | 4.4% | $ 9.2 | 72.8% | $ 3.4 | 27.2% | $1.6 | 12.8% | $1.8 | 14.4% |

| 1955 | 400.0 | 17.7 | 105 | 4.4 | 13.2 | 74.3 | 4.6 | 25.7 | 2.0 | 11.3 | 2.6 | 14.4 |

| 1960 | 506.5 | 26.9 | 146 | 5.3 | 20.3 | 75.3 | 6.6 | 24.7 | 3.0 | 11.2 | 3.6 | 13.5 |

| 1965 | 691.0 | 41.7 | 211 | 6.0 | 30.9 | 74.1 | 10.8 | 25.9 | 5.5 | 13.3 | 5.2 | 12.6 |

| 1966 | 756.0 | 46.1 | 230 | 6.1 | 32.5 | 70.6 | 13.6 | 29.4 | 7.4 | 16.1 | 6.1 | 13.3 |

| 1967 | 799.6 | 51.3 | 254 | 6.4 | 32.4 | 63.1 | 19.0 | 36.9 | 11.9 | 23.2 | 7.0 | 13.7 |

| 1968 | 873.4 | 58.2 | 285 | 6.7 | 36.1 | 62.0 | 22.1 | 38.0 | 14.1 | 24.3 | 8.0 | 13.7 |

| 1969 | 944.0 | 65.7 | 318 | 7.0 | 40.8 | 62.1 | 24.9 | 37.9 | 16.1 | 24.5 | 8.8 | 13.4 |

| 1970 | 992.7 | 74.7 | 358 | 7.5 | 46.9 | 62.8 | 27.8 | 37.2 | 17.7 | 23.7 | 10.1 | 13.6 |

| 1971 | 1,077.6 | 83.3 | 394 | 7.7 | 51.6 | 62.0 | 31.7 | 38.0 | 20.3 | 24.4 | 11.3 | 13.6 |

| 1972 | 1,185.9 | 93.5 | 438 | 7.9 | 58.1 | 62.1 | 35.4 | 37.9 | 22.9 | 24.5 | 12.5 | 13.4 |

| 1973 | 1,326.4 | 103.2 | 478 | 7.8 | 63.9 | 61.9 | 39.3 | 38.1 | 25.2 | 24.5 | 14.1 | 13.7 |

| 1974 | 1,434.2 | 116.4 | 535 | 8.1 | 69.3 | 59.5 | 47.1 | 40.5 | 30.4 | 26.2 | 16.6 | 14.3 |

| 1975 | 1,549.2 | 132.7 | 604 | 8.6 | 76.5 | 57.7 | 56.2 | 42.3 | 37.1 | 27.9 | 19.1 | 14.4 |

| 1976 | 1,718.0 | 149.7 | 674 | 8.7 | 86.7 | 57.9 | 62.9 | 42.1 | 42.6 | 28.5 | 20.3 | 13.6 |

| 1977 | 1,918.3 | 169.2 | 755 | 8.8 | 99.1 | 58.6 | 70.1 | 41.4 | 47.4 | 28.0 | 22.7 | 13.4 |

| 1978 | 2,163.8 | 189.3 | 836 | 8.8 | 109.8 | 58.0 | 79.5 | 42.0 | 53.9 | 28.4 | 25.7 | 13.6 |

| 1979 | 2,417.8 | 215.0 | 938 | 8.9 | 124.4 | 57.9 | 90.6 | 42.1 | 61.0 | 28.4 | 29.5 | 13.7 |

| 1980 | 2,633.1 | 249.0 | 1,075 | 9.5 | 143.6 | 57.7 | 105.4 | 42.3 | 71.1 | 28.5 | 34.3 | 13.8 |

| 1981 | 2,937.7 | 286.6 | 1,225 | 9.8 | 164.1 | 57.3 | 122.5 | 42.7 | 83.9 | 29.2 | 38.6 | 13.5 |

| Projections | ||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| 1983 | 3,468.9 | 362.3 | 1,521 | 10.4 | 211.2 | 58.3 | 151.1 | 41.7 | 104.2 | 28.8 | 46.9 | 12.9 |

| 1985 | 4,207.4 | 456.4 | 1,882 | 10.8 | 268.2 | 58.8 | 188.1 | 41.2 | 131.5 | 28.8 | 56.6 | 12.4 |

| 1990 | 6,304.1 | 755.6 | 2,982 | 12.0 | 430.9 | 57.0 | 324.7 | 43.0 | 231.6 | 30.7 | 93.1 | 12.3 |

| Selected Periods | Average Annual Percent Increases | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| 1950-1955 | 6.9% | 6.9% | 5.2% | — | 7.4% | — | 5.8% | — | 4.6% | — | 7.6% | — |

| 1955-1960 | 4.8 | 8.7 | 6.8 | — | 9.0 | — | 7.8 | — | 8.5 | — | 6.7 | — |

| 1960-1965 | 6.4 | 9.2 | 7.6 | — | 8.8 | — | 10.2 | — | 12.9 | — | 7.6 | — |

| 1965-1970 | 7.5 | 12.4 | 11.2 | — | 8.7 | — | 20.8 | — | 26.1 | — | 14.0 | — |

| 1970-1975 | 9.3 | 12.2 | 11.0 | — | 10.3 | — | 15.1 | — | 16.0 | — | 13.6 | — |

| 1975-1980 | 11.2 | 13.4 | 12.2 | — | 13.4 | — | 13.4 | — | 13.9 | — | 12.5 | — |

| 1950-1980 | 7.7 | 10.4 | 8.9 | — | 9.6 | — | 12.1 | — | 13.5 | — | 10.2 | — |

| 1970-1980 | 10.2 | 12.8 | 11.6 | — | 11.8 | — | 14.3 | — | 14.9 | — | 13.0 | — |

| 1980-1990 | 9.1 | 11.7 | 10.7 | — | 11.6 | — | 11.9 | — | 12.5 | — | 10.5 | — |

| 1981-1983 | 8.7 | 12.4 | 11.4 | — | 13.4 | — | 11.1 | — | 11.4 | — | 10.3 | — |

| 1983-1985 | 10.1 | 12.2 | 11.2 | — | 12.7 | — | 11.6 | — | 12.3 | — | 9.9 | — |

| 1980-1985 | 9.8 | 12.9 | 11.9 | — | 13.3 | — | 12.3 | — | 13.1 | — | 10.5 | — |

| 1985-1990 | 8.4 | 10.6 | 9.6 | — | 9.9 | — | 11.5 | — | 12.0 | — | 10.4 | — |

| 1971-1981 | 10.5 | 13.2 | 12.0 | — | 12.3 | — | 14.5 | — | 15.2 | — | 13.1 | — |

| 1981-1990 | 8.9 | 11.4 | 10.4 | — | 11.3 | — | 11.4 | — | 11.9 | — | 10.3 | — |

Historical estimates are from Robert M. Gibson and Daniel R. Waldo, “National Health Expenditures, 1981,” Health Care Financing Review, September 1982, pp. 1-36.

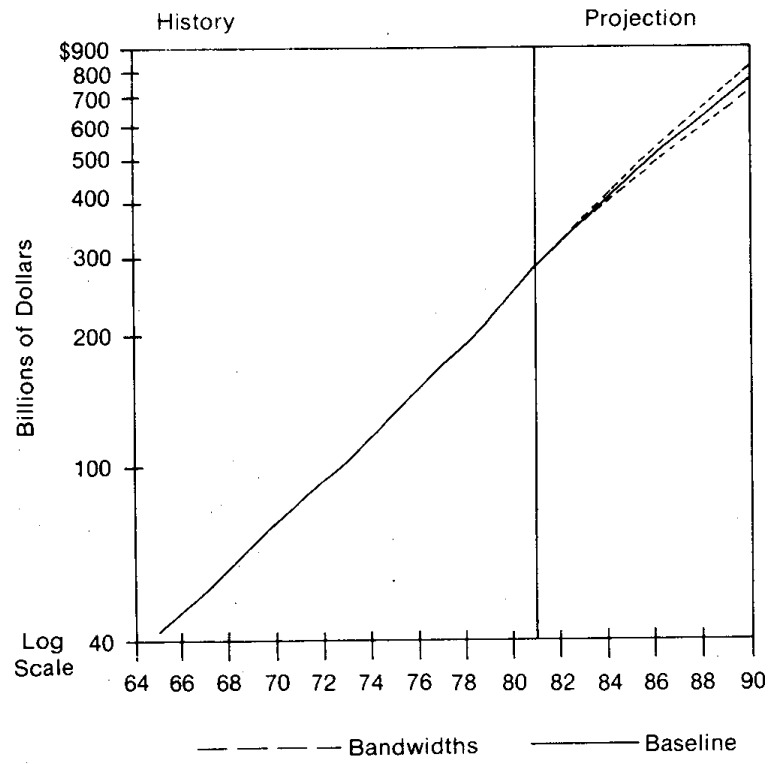

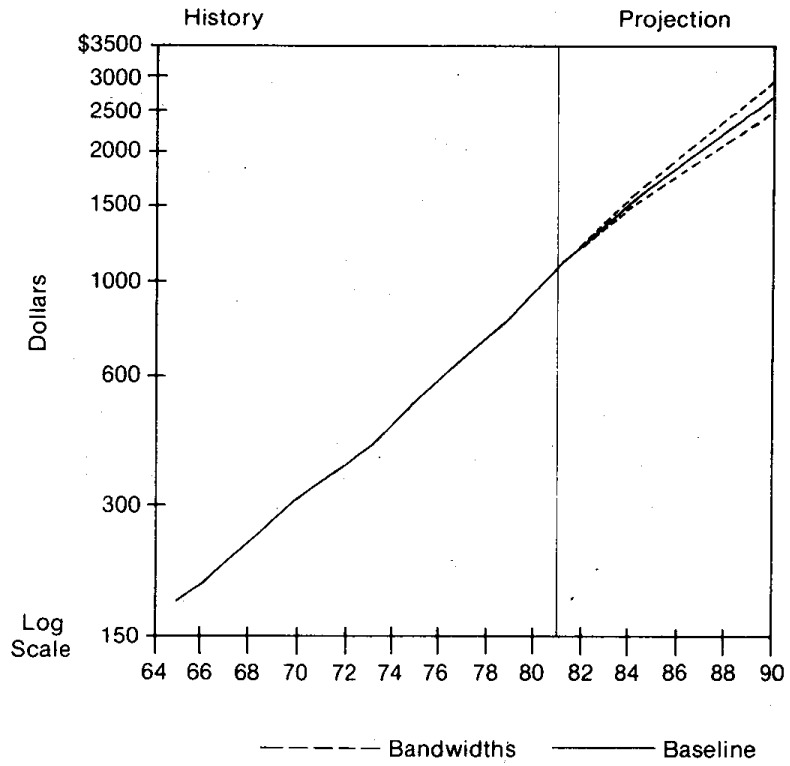

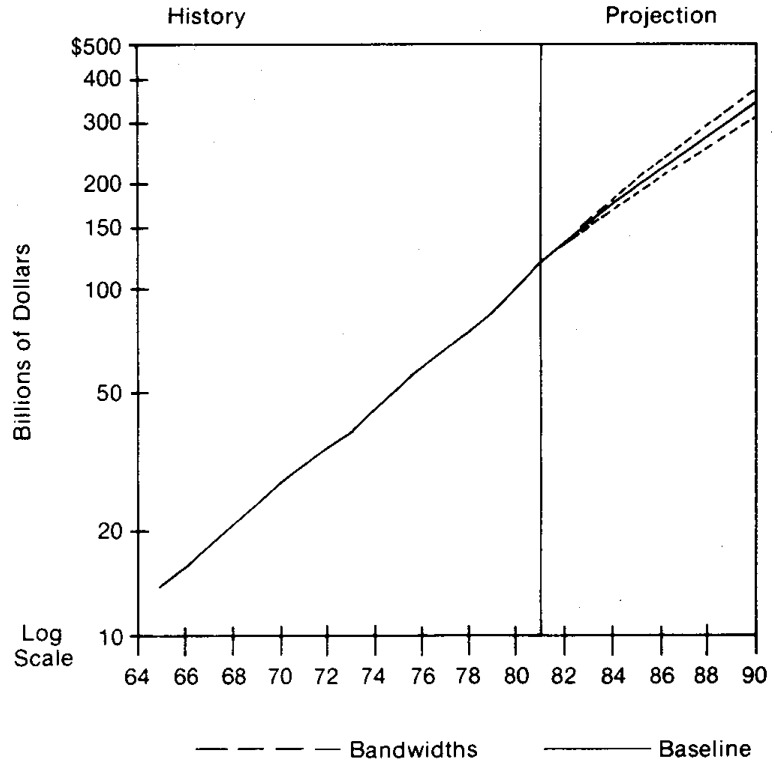

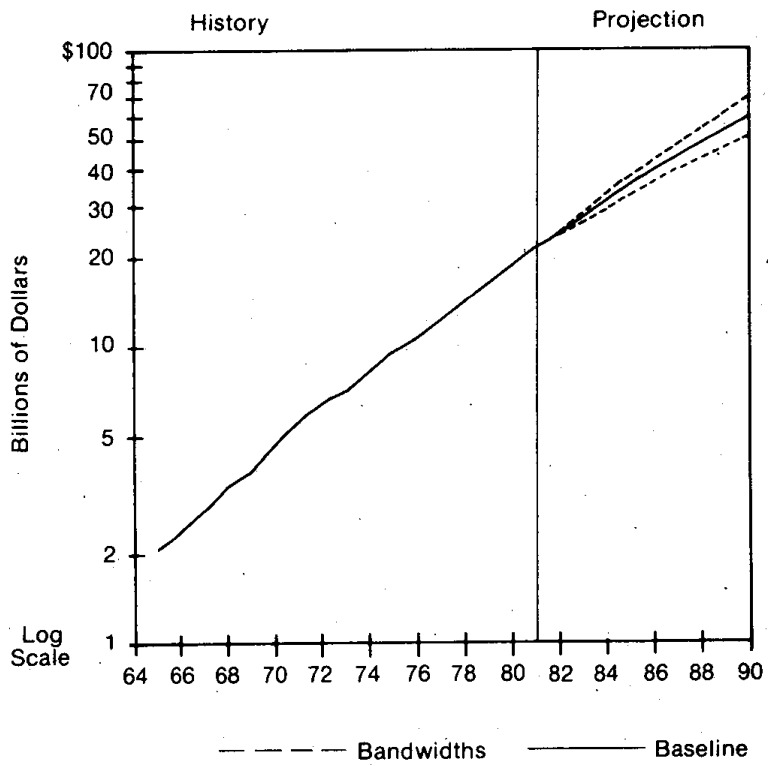

National health expenditures increased 33.3 percent and the GNP 21.5 percent during the 2-year period 1979-1981. Projected outlays for national health expenditures (Table 1 and Figure 1) are:

Figure 1. Total National Health Expenditures 1965 to 1990, with Bandwidth Intervals1.

1The bandwidth intervals around the baseline projection scenario provide one indicator of variability. The standard error associated with annual percent increases in total national health expenditures for 1966-1981 (see Table A-12) was multiplied by a t-distribution value of 2.131 to derive the bandwidth intervals. The calculated bandwidth intervals are approximate and are used as a rough guide in assessing variability and uncertainty.

$362 billion by 1983 or $1,521 per capita;

$456 billion by 1985 or $1,882 per capita;

$756 billion by 1990 or $2,982 per capita.

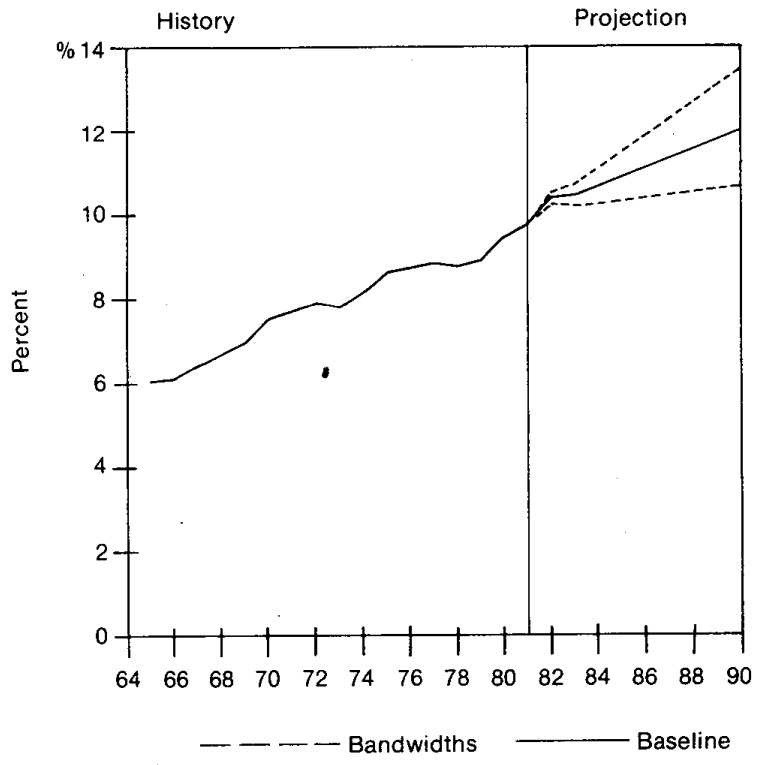

These projections reflect a gradual deceleration in expenditure growth, but the increases in health care spending are expected to continue to outpace growth in the Gross National Product (GNP). By 1983, the health sector share of the GNP is projected to increase to about 10.4 percent (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Share National Health Expenditures are of GNP 1965 to 1990, with Bandwidth Intervals1.

1The bandwidth intervals around the baseline projection scenario provide one indicator of variability. The standard error associated with annual percent increases in the ratio of national health expenditures to GNP for 1966-1981 (see Table A-11) was multiplied by a t-distribution value of 2.131 to derive the bandwidth intervals. The calculated bandwidth intervals are approximate and are used as a rough guide in assessing variability and uncertainty.

The projected negative growth in real GNP in 1982 and the relatively fast growth in health care spending account for the rapid projected increase in the ratio of health spending to GNP for the period 1981-1983. Extensive third-party payments for health care and the necessary nature of much care, insulate growth in aggregate health care expenditures from short-term fluctuations in real GNP. On the other hand, some services which have shallow insurance coverage such as eyeglasses, drugs, and other professional services appear to be adversely affected by the recession.

We expect the upward trend in the health care sector's share of GNP to slow as the economy rebounds in 1983. A gradual increase in this share is projected for the remainder of the 1980's, reaching roughly 12.0 percent in 1990. Between 1965 and 1982, health's share of GNP increased at an average annual rate of 3.3 percent per year (partial year data were available for 1982 estimate). From 1982 to 1990 it is expected to increase at an average annual rate of 1.8 percent. From 1981 to 1990, health expenditure growth is expected to rise slower (average annual rate of 11.4 percent) than in the post-Medicare historical period 1971-1981 (average annual rate of 1.3.2 percent).

A projected decline in the general inflation rate leading to lower health care price increases will exert a downward pressure on health spending in the 1980s. Restrained growth in public financing of health care will exert further downward pressure. However, projected increases in real GNP, beginning in 1983, will exert an upward pressure as will aging of the population and new technologies. As the economy expands the fiscal tightness affecting government programs may tend to ease. We project that the net effect of these pressures will be a deceleration in the growth of health spending.

Government Funding of National Health Expenditures

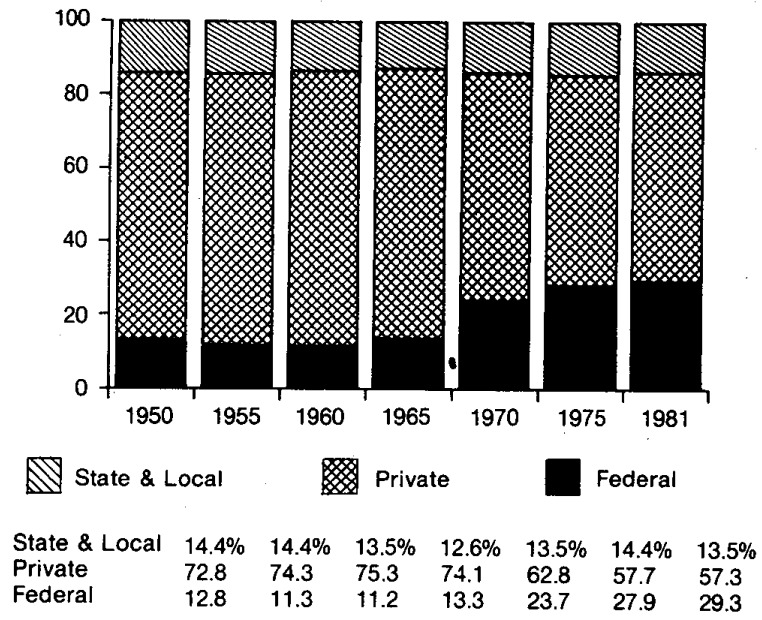

In 1981 the Federal share of spending was 29.3 percent (Figure 3 and Table 1), having increased its share 5 percentage points since 1973 (Table A-5). Due to a maturing of Federal health programs and the tight fiscal situation, the Federal share stabilizes at approximately 29 percent for 1983 and 1985. It rises to 31 percent by 1990 due to the aging of the population and the expanding revenue base accompanying the more robust economic growth.

Figure 3. Percent Distribution of Total National Health Expenditures by Source of Funds for Selected Years, 1950 to 1981.

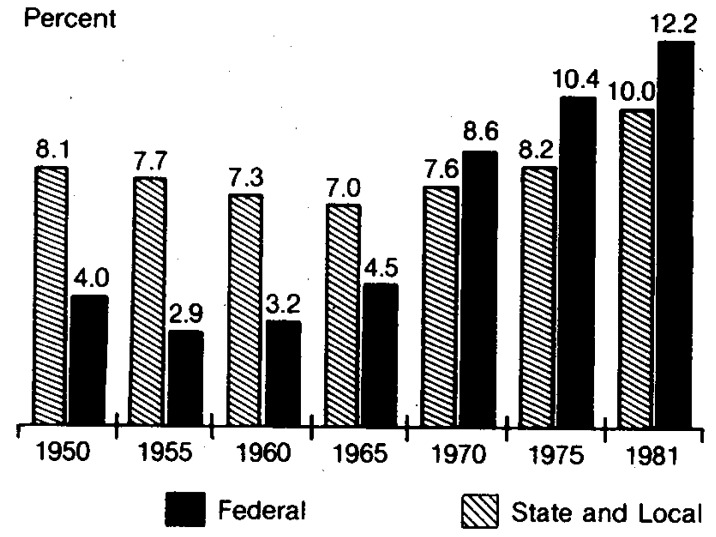

Federal outlays for national health expenditures, which were $1.6 billion in 1950, increased to $5.5 billion in 1965 and $83.9 billion in 1981 (Table A-5). Federal expenditures increased at an average annual rate of 18.5 percent for the period 1965-1981 (Table A-5). Federally financed health expenditures were 4.5 percent of total Federal government expenditures in 1965 and this percentage has risen to 12.2 percent in 1981 (Figure 4 and Table A-18).

Figure 4. National Health Expenditures as a Percent of Government Expenditures for Selected Years, 1950 to 1981.

Table A-18. Federally Financed Health Expenditures Relative to Total Federal Government Expenditures, and to Gross National Product, Selected Years, 1950-1981.

| Year | Health1 Expenditures Federally, Financed (Amounts in billions of dollars) |

Federal Government2 Expenditures (Amounts in billions of dollars) |

Health Expenditures Federally Financed As Percent of Federal Gov't Expenditures | Gross National Product2 (Amounts in billions of dollars) |

Federal Gov't Expenditures As Percent of Gross National Product | Health Expenditures Federally Financed As Percent of Gross National Product |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| 1950 | $1.6 | $40.8 | 3.9% | $286.5 | 14.2% | 0.6% |

| 1955 | 2.0 | 68.1 | 2.9 | 400.0 | 17.0 | 0.5 |

| 1960 | 3.0 | 93.8 | 3.2 | 506.5 | 18.4 | 0.6 |

| 1965 | 5.5 | 123.8 | 4.4 | 691.0 | 17.9 | 0.8 |

| 1966 | 7.4 | 143.8 | 5.2 | 756.0 | 19.0 | 1.0 |

| 1967 | 11.9 | 163.7 | 7.3 | 799.6 | 20.5 | 1.5 |

| 1968 | 14.9 | 180.5 | 7.8 | 873.4 | 20.7 | 1.6 |

| 1969 | 16.1 | 188.4 | 8.5 | 944.0 | 20.0 | 1.7 |

| 1970 | 17.7 | 204.3 | 8.7 | 992.7 | 20.6 | 1.8 |

| 1971 | 20.3 | 220.6 | 9.2 | 1,077.6 | 20.5 | 1.9 |

| 1972 | 22.9 | 244.3 | 9.4 | 1,185.9 | 20.6 | 1.9 |

| 1973 | 25.2 | 264.3 | 9.5 | 1,326.4 | 19.9 | 1.9 |

| 1974 | 30.4 | 299.4 | 10.2 | 1,434.2 | 20.9 | 2.1 |

| 1975 | 37.1 | 356.6 | 10.4 | 1,549.2 | 23.0 | 2.4 |

| 1976 | 42.6 | 384.8 | 11.1 | 1,718.0 | 22.4 | 2.5 |

| 1977 | 47.4 | 421.1 | 11.3 | 1,918.3 | 22.0 | 2.5 |

| 1978 | 53.9 | 461.1 | 11.7 | 2,163.8 | 21.3 | 2.5 |

| 1979 | 61.0 | 509.7 | 12.0 | 2,417.8 | 21.3 | 2.5 |

| 1980 | 71.1 | 602.1 | 11.8 | 2,633.1 | 22.9 | 2.7 |

| 1981 | 83.9 | 688.2 | 12.2 | 2,937.7 | 23.4 | 2.9 |

Robert M. Gibson and Daniel R. Waldo, “National Health Expenditures, 1981,” Health Care Financing Review, September 1982.

Bureau of Economic Analysis, Survey of Current Business, U.S. Department of Commerce.

The short-term outlook is for Federal expenditures to rise to $104 billion in 1983, an increase of $20 billion over 1981. We project that Federal expenditures will reach $131 billion by 1985 and $232 billion by 1990. Federal outlays for national health expenditures are expected to increase at an average annual rate of 11.9 percent, a rate substantially below the 15.2 percent rate for the 1971-1981 period.

For the period 1950 to the mid-1970's State and locally financed health expenditures were 7-8 percent of total State and local government expenditures. By 1981 this ratio had risen to 10 percent (Figure 4 and Table A-19). State and local governments have consistently financed 13-14 percent of national health expenditures (Table 1 and Figure 3). The State and local share of spending is projected to drop slightly between 1981 and 1985 and then stabilize at 12-13 percent for the period 1985-1990.

Table A-19. State and Local Financed Health Expenditures Relative to Total State and Local Government Expenditures, and to Gross National Product, Selected Years, 1950-1981.

| Year | Health Expenditures State & Local Financed (Amount in billions of dollars)1 |

State & Local Gov't Expenditures (Amount in billions of dollars)2 |

Health Expenditures State and Local Financed As Percent of State and Local Gov't Expenditures | Gross National Product (Amount in billions of dollars) |

State and Local Expenditures as Percent of Gross National Product | Health Expenditures State & Local Financed as Percent of Gross National Product |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| 1950 | $1.8 | $22.5 | 8.1% | $286.5 | 7.9% | 0.6% |

| 1955 | 2.6 | 32.9 | 7.7 | 400.0 | 8.2 | 0.7 |

| 1960 | 3.6 | 49.8 | 7.3 | 506.5 | 9.8 | 0.7 |

| 1965 | 5.2 | 75.1 | 7.0 | 691.0 | 10.9 | 0.8 |

| 1966 | 6.1 | 84.3 | 7.2 | 756.0 | 11.2 | 0.8 |

| 1967 | 7.0 | 94.7 | 7.4 | 799.6 | 11.8 | 0.9 |

| 1968 | 8.0 | 107.2 | 7.5 | 873.4 | 12.3 | 0.9 |

| 1969 | 8.8 | 118.7 | 7.4 | 944.0 | 12.6 | 0.9 |

| 1970 | 10.1 | 133.5 | 7.6 | 992.7 | 13.5 | 1.0 |

| 1971 | 11.3 | 150.5 | 7.5 | 1,077.6 | 14.0 | 1.0 |

| 1972 | 12.5 | 164.8 | 7.6 | 1,185.9 | 13.9 | 1.1 |

| 1973 | 14.1 | 181.6 | 7.8 | 1,326.4 | 13.7 | 1.1 |

| 1974 | 16.7 | 204.5 | 8.2 | 1,434.2 | 14.3 | 1.2 |

| 1975 | 19.1 | 232.1 | 8.2 | 1,549.2 | 15.0 | 1.2 |

| 1976 | 20.4 | 251.3 | 8.1 | 1,718.0 | 14.6 | 1.2 |

| 1977 | 22.7 | 269.7 | 8.4 | 1,918.3 | 14.1 | 1.2 |

| 1978 | 25.7 | 297.4 | 8.6 | 2,163.8 | 13.7 | 1.2 |

| 1979 | 29.5 | 321.5 | 9.2 | 2,417.8 | 13.3 | 1.2 |

| 1980 | 34.3 | 357.8 | 9.6 | 2,633.1 | 13.6 | 1.3 |

| 1981 | 38.6 | 385.0 | 10.0 | 2,937.7 | 13.1 | 1.3 |

Robert M. Gibson and Daniel R. Waldo, “National Health Expenditures, 1981,” Health Care Financing Review, September 1982.

Bureau of Economic Analysis, Survey of Current Business, U.S. Department of Commerce.

We project that State and local outlays will be $47 billion in 1983, $57 billion in 1985, and $93 billion in 1990. The average annual growth rate for health expenditures State and locally financed during 1981-1990 is 10.3 percent, a rate substantially below the 13.1-percent rate for the period 1971-1981.

Private Funding

The private sector financed 57.3 percent of expenditures in 1981, a decline from 62.8 percent in 1970 (Table 1 and Figure 3). The private share is projected to increase over the period 1981-1985 and drop slightly over the period 1985-1990 as the aging population and more robust economy contribute to a slightly larger share of public financing derived from an expanding revenue base.

Private expenditures for health care are expected to reach $211 billion by 1983 and $431 billion by 1990. For the period 1981-1990 private expenditures are expected to increase at an average annual rate of 11.3 percent, close to the 1965-1981 rate of 11.0 percent.

World-Wide Burgeoning Cost of Health Care

Relatively high rates of growth in health care expenditures are not unique to the United States. Economy-wide inflation, growth in real income, demographic shifts, and product-innovative technologies have been associated with rising health care costs in the western industrialized countries.

In one study of the rising cost of health care among nine industrialized countries, expenditures increased during 1969 to 1976 at average annual rates from a low of 12.5% (United States) to a high of 20.5% (Australia) (Table 2). In all nine countries health expenditures increased as a proportion of GNP. While the United States is among the highest, when ranked according to percent spent on health care, the Federal Republic of Germany topped the list with 9.7 percent of GNP spent on health care for the year 1975 (the latest available data in the study).

Table 2. National Health Expenditures in Nine Industrialized Countries, Average Annual Percent Increases, and as Percent of Gross National Product, 1969 and 19761.

| National Health Expenditures | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Country (ranked by 1969-1976 increase in health expenditures) | Average Annual Rate of Increase, 1969-1976 | As Percent of GNP | |

|

| |||

| 1969 | 1976 | ||

| Australia | 20.5% | 5.6% | 7.7% |

| Finland | 18.9 | 6.0 | 7.2 |

| Netherlands | 18.4 | 6.0 | 8.5 |

| United Kingdom | 18.2 | 4.5 | 5.8 |

| Federal Republic of Germany | 17.7 | 6.3 | 9.72 |

| France | 16.5 | 6.3 | 8.2 |

| Sweden | 14.6 | 7.2 | 8.72 |

| Canada | 14.3 | 6.8 | 7.1 |

| United States3 | 12.5 | 7.0 | 8.7 |

Simanis and Coleman (1980).

National health expenditures as percent of gross national product were not available for 1976. The 1975 ratios are given. See Simanis and Coleman (1980).

Some analysts suggest that health spending as a proportion of GNP tends to grow in spurts. Countries appear to have relatively effective methods to stem the rise in health spending relative to GNP, then slippage in the system results in health spending escalating relative to GNP.

Nations implicitly or explicitly make judgments about the “correct” ratio of GNP allocated to health care. For example, Finland is reported to have earmarked 15 percent of GNP for health care under the assumptions that health care is socially desirable and that employment in the health sector is as good as any other type of employment (Perspective, 1982).

Why Health Expenditures Are Rising

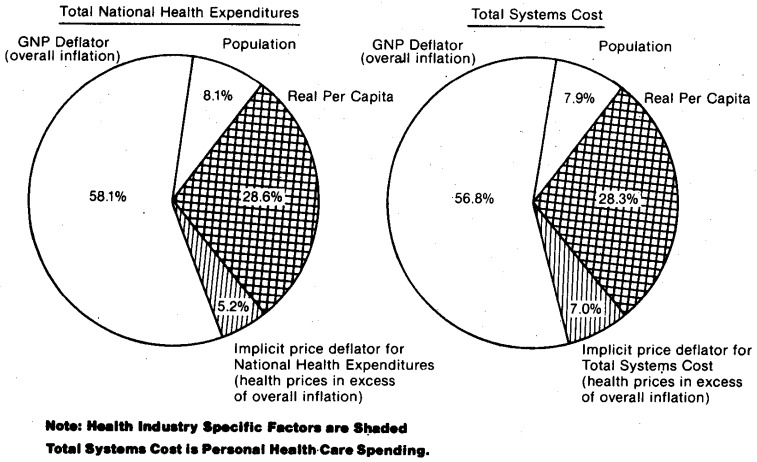

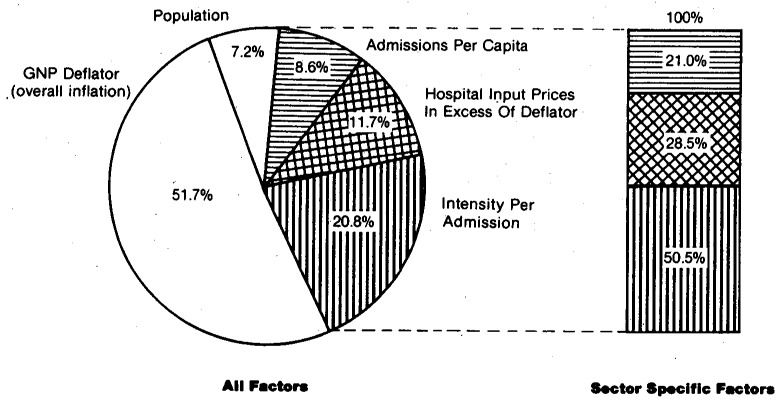

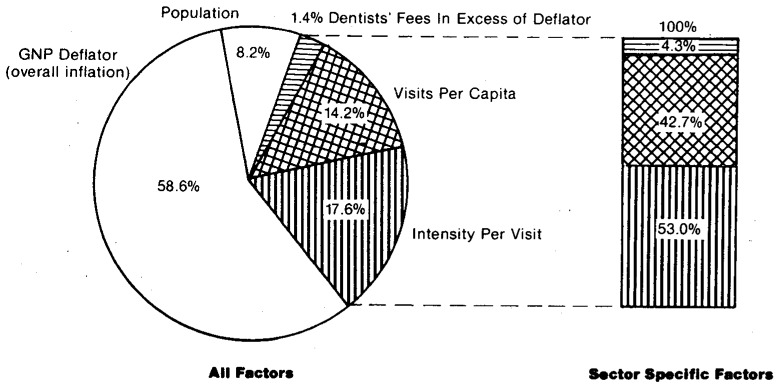

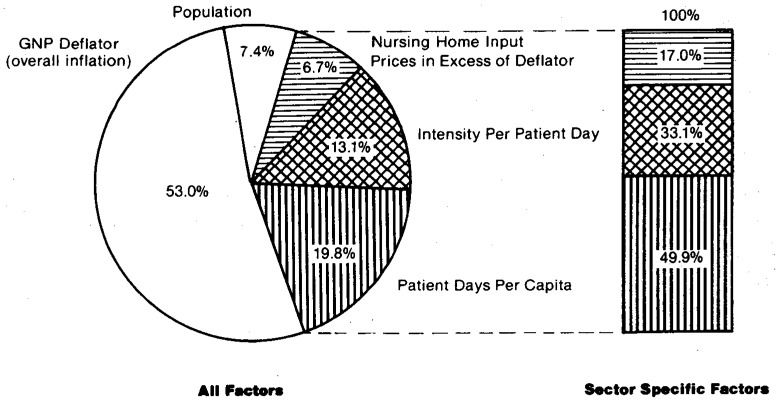

Many factors account for the rising cost of health care. The projection process uses a five-factor formula which accounts for how expenditures rise. The five components are changes in: (1) general inflation, (2) aggregate population, (3) medical-care prices in excess of overall price inflation (4) per capita visits and per capita patient days and (5) the mix and content of services and supplies per visit or per day. These five “how” factors (see Tables 3 and 4), two relating to the general economy and three specific to the health sector, account for all increases in expenditure growth since one factor (changes in the mix and content of services and supplies per visit or per patient day) is calculated as a residual. The five factors combine to form an accounting identity in the historical period.

Table 3. “How” Versus “Why” Medical Care Expenditures Rise1.

| “How” Medical Care Expenditures Rise | “Why” Medical Care Expenditures Rise | |

|---|---|---|

| Economy-Wide Factors | ||

| 1. | General Inflation | Montetary policies; fiscal policies relating to taxing, spending, and debt management; supply-side shocks such as energy price increases, food price increases caused by world-wide droughts, Social Security tax rate increases, and minimum wage increases; productivity changes; and monopoly powers of firms and unions over prices and wages. |

| 2. | Aggregate population growth | Birth rates, death rates, in migration, out migration. |

| “Health-Sector Specific” Factors | ||

|

| ||

| 3. | Growth in per capita patient visits and per capita patient days | Factors influencing the demand for and supply of medical care services such as: |

| ||

| 4. | Changes in the nature of services and supplies provided per visit or per patient day (product innovation, intensity of service, amenities, etc.)2 | Generally the same factors as in 3 above, however, the relative importance of particular factors may differ. |

| 5. | Medical care price increases relative to general price inflation | Generally the same factors as in 3 above, however, the relative importance of particular factors may differ and in some cases the sign of the factor may differ. For example, increasing the number of dentists relative to population in a given geographic area may cause dental prices to rise slower than would otherwise be the case and to expand utilization of dental services in the geographic area. In other words, expanding the supply of dentists, all other things constant, may have a negative impact on price increases but a positive impact on visits and intensity of services per visit. |

Martin Feldstein (1971) has made this distinction between “how” versus “why” medical care expenditures have risen. For analyses accounting for expenditure growth using the “how” approach, see M. Feldstein (1971,1981), P. Feldstein (1979), Klarman, Rice, Cooper, and Stettler (1970), and Mushkin (1979).

This factor is calculated as a residual by deflating current dollar expenditures per visit or per patient day by a relevant price index. This yields growth in “real services” per visit or per day.

Table 4. Factors Accounting for Growth in Expenditures for Selected Categories of Total Systems Cost, 1971 to 19811.

| Factors Accounting for “How” Medical Care Expenditures Rose | Community Hospital Care | Physicians' Services | Dentists' Services | Nursing Home Care Excluding ICF-MR | Total Systems Cost (Personal Health Care) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| inpatient Expenses2 | Outpatient Expenses2 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Inpatient Days | Admissions | |||||||

| Economy-Wide factors | ||||||||

| 1. | General inflation | 51.7% | 51.7% | 41.6% | 58.1% | 58.6% | 53.0% | 56.8% |

| 2. | Aggregate population growth | 7.2 | 7.2 | 5.6 | 8.1 | 8.2 | 7.4 | 7.9 |

| “Health-Sector Specific” Factors | ||||||||

| 3. | Growth in per capita visits or patient days | 4.2 | 8.6 | 17.9 | −3.4 | 14.2 | 19.8 | NA |

| 4. | Growth in real services per visit or per day (intensity) | 25.2 | 20.8 | 25.3 | 27.4 | 17.6 | 13.1 | NA |

| 5. | Medical care price increases relative to general price inflation3 | 11.7 | 11.7 | 9.6 | 9.8 | 1.4 | 6.7 | 7.0 |

| Addenda: Growth in real services per capita | — | — | — | — | — | — | 28.3 | |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

NA = Not available

Total systems cost is called personal health care in Gibson and Waldo (1982).

Community hospital expenses are split into inpatient and outpatient expenses using the American Hospital Association (1982) procedure.

See Table A-13 for price variables.

From a behavioral or “why” point of view, the causal factors for each of the five “how” factors are analyzed (Table 3). During the projection process we determine our growth rates for the “how” factors by analyzing and evaluating the effects of the “why” factors. For example, in the nursing-home sector, we examine increases in the age 75 and over population, (a “why” factor) as one determinant of growth in nursing home days per capita (a “how” factor).

Understanding Health Care Expenditure Growth

General inflation, a “how” factor, accounted for approximately 57 percent of the increase in total systems cost (personal health care cost) for the period 1971-1981 (Table 4 and Figure 6). General inflation, a complex and volatile phenomenon, is caused by many factors including monetary policy, fiscal policy, supply-side shocks such as energy price increases, productivity changes, etc. (Table 3).

Figure 6. Factors Accounting for Growth in Total Health Costs 1971 to 1981.

While overall inflation is clearly the single most important factor accounting for expenditure growth, lowering the overall inflation rate will not reduce the ever-increasing amount of real resources flowing into the health sector. Health sector-specific factors relating to the demand for and supply of medical care services must be examined to understand the flow of real resources into the health sector relative to the rest of the economy.

Factors contributing to the rapid growth in health spending are numerous and interrelated (National Commission on the Cost of Medical Care, 1978). The interplay of demand pressures and supply incentives contribute to the growth in specific types of medical expenditures. Two factors are particularly note-worthy: first, a demand-side factor, the role of third party payments in increasing consumer demand for services, and second, a supply-side factor, the fee-for-service and cost-based reimbursement systems which lack incentives to provide medical care in the least expensive manner.

The third-party financing of medical care increases demand for services and incorporates cost-increasing incentives. Studies correlate increases in medical care prices and expenditures not only to increased insurance coverage, but also to the level of such coverage (National Commission on the Cost of Medical Care, 1978; Newhouse, 1978). As we approach the point where third parties finance 100 percent of the consumers' cost, providers and consumers of medical care appear to increasingly treat medical care as a free service at the time of decision-making, resulting in increased consumer demand for services. For example, in the hospital sector the proportion paid out of pocket has remained at roughly 10 percent from 1967 through 1981, yet community hospital revenues during this period have increased at an average annual rate of almost 16 percent. In the 2-year period 1979 to 1981, community hospital revenues rose 40 percent while a broad-based measure to finance such care, the GNP, rose 22 percent. Third-party payments play a very significant role in increasing access to quality care, but they also have the effect of divorcing utilization and price from ability to pay at the individual level and to a lesser extent at the aggregate level.

Third-party payment growth is stimulated by the provision of tax subsidies for private health insurance. These subsidies provide incentives to purchase more insurance (Congressional Budget Office, 1980; Feldstein 1981; Greenspan and Vogel, 1980). The additional insurance then encourages further use of medical care.

Third-party reimbursement systems incorporate incentives to increase costs (Enthoven, 1980). Retrospective cost-based reimbursement for hospitals and fee-for-service reimbursement for physicians reward those providers who supply larger quantities and more costly services with more revenues. An incentive is therefore provided to adopt new diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and techniques (product-innovative technologies) rather than to adopt new processes to more efficiently produce existing procedures and techniques (process-innovative technologies). (Altman and Blendon, 1979; Feldstein, 1981).

The diffusion of information relating to new techniques, procedures, and supplies (such as: implants, transplants, CT scans, life-saving drugs, etc.) can push up demand. First, as persons become aware of techniques, procedures, and supplies through the mass media they may pressure providers to make them available. Second, the consumer population purchases more comprehensive insurance at higher premium rates to reimburse for more expensive procedures and techniques (Feldstein, 1981). Political pressure may be applied to cover such innovations under public programs. Third, increased awareness can be associated with greater utilization of health services. Detailed physical examinations may diagnose conditions that cannot be cured with today's state-of-the-art medicine, but which may result in expensive maintenance programs.

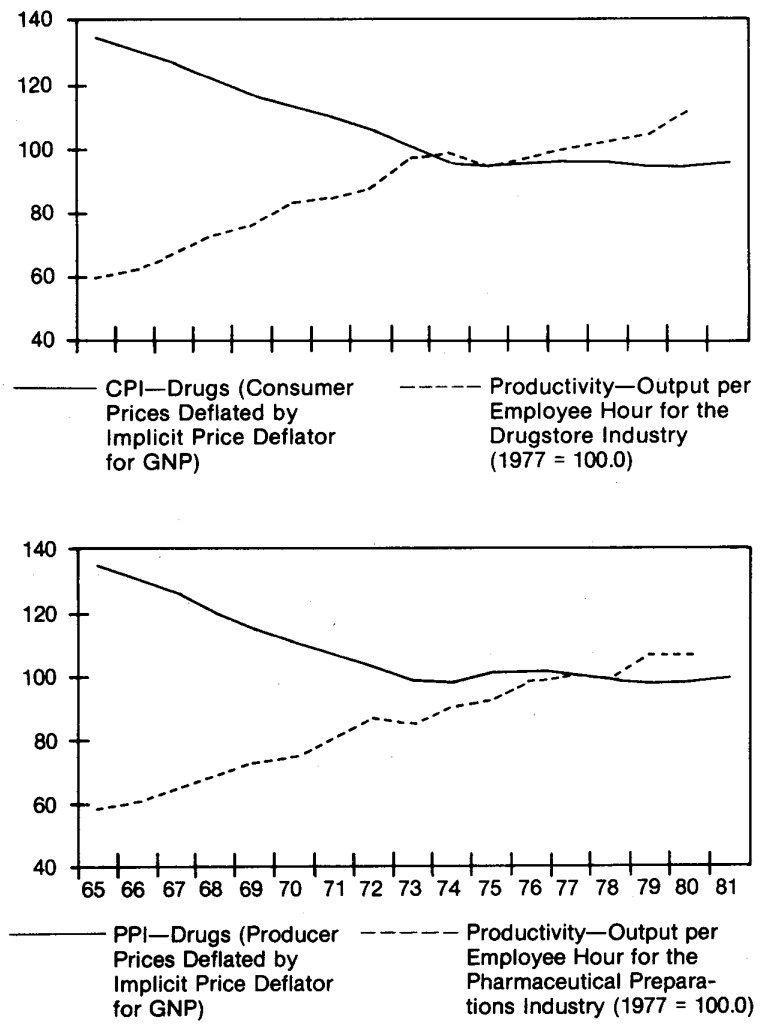

It has been suggested that productivity levels in the health-services sector are lower than in the overall economy; that the rate of increase in productivity is slower than in the private sector; and that significant increases can be made in current productivity levels. Baumol's model of unbalanced economic growth (1967) may have relevance for the health services sector (Mushkin et al., 1978).

Applying this to the health sector: If productivity or output per manhour increases faster in the nonhealth sector than in the health sector, and wages increase at the same rate in both sectors, then unit costs in the health sector must increase faster than in the nonhealth sector. Fragmentary evidence on wages, prices, and productivity is consistent with such an application of Baumol's model.

Between 1972 and 19812 wages in the health sector increased at an average annual rate of 8.3 percent compared to 7.8 percent in the total private economy (Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment and Earnings). During the period 1969 to 1979, productivity in the health services industry is reported to have declined at an average annual rate of −1.4 percent per year while productivity in the private nonfarm economy increased at an average annual rate of 1.7 percent (Table A-24).3 For the same period as for wage increases above (1972-1981), the medical care services component of the Consumer Price Index rose at an average annual rate of 9.7 percent compared to the 8.1 percent rate for the fixed-weight personal consumption expenditure price index (Bureau of Economic Analysis, Survey of Current Business). Thus, medical care service prices increased at an average annual rate 20 percent faster than overall consumer prices. Price data were used, rather than unit-cost data, since cost data were not available for either the health-services sector or for the total private economy. If the percent mark-up of unit prices over unit costs is constant over time, the growth in both prices and unit costs will be the same. The difficulty in measuring output in the health services sector (Reder, 1969) has hampered efforts to measure price changes for a fixed unit of service over time. Some factors, such as the increasing sophistication of care that cannot be separated from a “fixed” unit of service over time, may result in medical care price statistics being biased upward over time. Other factors, such as separating services and procedures into finer components and billing individually for each service or procedure, may result in medical care price statistics being biased downward over time (Ginsberg, 1978; Showstack et al., 1979; Sobaski et al., 1975).

Table A-24. Average Annual Rate of Change in Productivity, Selected Industries, 1969-19791.

| Selected Industries | Productivity2 |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Health Services | −1.4% |

| All Industries | 1.7 |

| Private Nonfarm Economy3 | 1.7 |

| Manufacturing | 2.7 |

| Transportation | 2.1 |

| Wholesale and Retail Trade | 1.4 |

| Finance, Insurance and Real Estate | 0.7 |

| All Services | 0.6 |

| Business Services | 0.7 |

| Other Services | 1.1 |

| Government and Government Enterprises | 0.7 |

Bureau of Industrial Economics (January 1982, p. 424).

Productivity is defined as gross product originating per hour worked. “Gross productivity originating” is constant dollar value added and represents that industry's contribution to real gross national product. “Productivity” is calculated by dividing gross product originating by hours worked. These measures differ from the Bureau of Labor Statistics' measures of productivity in the private nonfarm business sector, because of differences in coverage. See Bureau of Industrial Economics (January 1982, p. 424).

Excludes government and farms.

Relatively high price increases in the health services sector may be partially explained by lower productivity increases in the health care industry.4 The relatively high price increases, combined with an inelastic demand for medical care (Newhouse and Phelps, 1976; Newhouse et al., 1981), contributes to the increase in expenditures for health care relative to the GNP.

Another hypothesis relating to increasing costs is that physicians may be able to induce some demand for their service (Cotterill, 1979; Reinhardt, 1978). The patient's dependence upon the physician for technical decisions and the existence of third-party payments may provide the means for physicians to raise fees and increase intensity of services. According to the physician-induced demand and target-income models, increases in the number of physicians are associated with increases in expenditures for their services. This relationship becomes more important when the interaction of physicians' services and other related health services is noted (Blumberg, 1979; Pauly, 1980; Pauly and Redisch, 1973; Redisch, 1978). Blumberg estimates that the physician influences approximately 70 percent of total systems cost (personal health care expenditures). Thus, according to this hypothesis, the number of physicians is correlated not only with expenditures for physicians' services, but also with expenditures for hospital care, other professional services, drugs, and so forth.

Between 1965 and 1981, the number of active physicians increased at an average annual rate of 3.0 percent, triple the average annual rate for the population, 1.1 percent. For the period 1981 to 1990, the Bureau of Health Professions projects that the number of active physicians will increase at an average annual rate of 2.7 percent (Table A-4). This increase in the number of physicians is likely to be associated with increases in per capita and aggregate medical expenditures, especially for services significantly covered by third-party payments. If insurance pays all costs, a provider's pricing behavior has little effect on market shares (Congressional Budget Office, May 1982A). For example, if a market area has full insurance coverage (no consumer cost sharing), an individual physician can raise his fees without his services becoming less attractive (from a price point of view) at the time of purchase.

Increases in real income and shifts in the age distribution of the population toward the more aged segment expands demand (Denton and Spencer, 1975; Dresch et al., 1981; Fisher, 1980; Russell, 1981; Torrey, 1981; Torrey, 1982).

An Important factor that is sometimes overlooked is that achieving satisfaction in all areas of life is conditioned on and affected by one's subjective feeling of health status. If one does not feel well, other satisfactions (material and nonmaterial) are typically diminished and in some cases eliminated.

Psychological factors (expectations, motivations, past experiences, etc.) are important in understanding most all economic behavior (Alhadeff, 1982; Katona, 1975; Maital, 1982; Scitovsky, 1976), but such factors are especially important in understanding consumer and provider behavior in medical care markets. Pain, guilt, uncertainty, and subjective well-being (experienced in some cases by the patient, families, and physician) can put significant pressures on patients, their families, and providers to utilize quantities and qualities of medical care that may appear excessive when viewed from a strictly cost-benefit point of view.

A last theory is that some services once provided free by household members are now provided by health professionals (Fuchs, 1979). This factor contributes to growth in the health sector and is of particular importance for one of the fastest growing services, long-term care (Chiswick, 1976). The increasing proportion of females 16 years of age and over who are in the labor force, contributes to the shift in providing services. This proportion has increased from 39 percent in 1965 to 52 percent in 1981 (Council of Economic Advisors, 1982) resulting in a smaller number of persons available for productive, nonpaying work in the household. Because more women are working, the opportunity cost of providing unpaid personal-care services for relatives and friends has increased. In addition, the size of the average household decreased from 3.3 persons in 1965 to 2.7 in 1981, a decline of 18 percent (Bureau of Census, 1981). As average household size decreases due to social, economic and demographic forces, there are fewer household members to provide personal care.

As more women join the labor force and as the average household size decreases, some long-term care activities have been “pushed” out of the household and into the for-pay health sector. It is also likely that increased third-party payments for coverage of health services have increased this trend.

Total Systems Cost Per Capita (TSCPC)

The net effect of all the causal factors on spending for health care can be summarized in personal health care cost per capita. It is important to have a comprehensive definition of costs when evaluating a public program, regulatory policy, insurance benefit package or marketing strategy since each of these is likely to have direct and indirect effects on medical care utilization, quality, and price. Total systems cost per capita (TSCPC) provides such a measure.

Total systems cost per capita includes all medical care costs related to direct patient care: long-term and short-term, inpatient and ambulatory, covered and uncovered by third-party reimbursement. It includes all services and supplies included in personal health care (Gibson and Waldo, 1982) such as hospital care, physicians' services, drugs, nursing-home care, etc. (Table 5).

Table 5. Percentage Distribution of Total Systems Cost, by Type of Service, Selected Years, 1950-19901.

| Calendar Year | Total Systems Cost Per Capita Current Dollars | Total Systems Cost Current Dollars | Total Systems Cost | Hospital Care | Physicians' Services | Dentists' Services | Other Professional Services | Drugs and Medical Sundries | Eyeglasses and Appliances | Nursing-Home Care | Other Health Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Historical Estimates | (Amount in (dollars) | (Amount in (billions) | Percentage Distribution | ||||||||

| 1950 | $ 70 | $ 10.9 | 100.0% | 35.4% | 25.2% | 8.8% | 3.6% | 15.9% | 4.5% | 1.7% | 4.8% |

| 1960 | 129 | 23.7 | 100.0 | 38.4 | 24.0 | 8.3 | 3.6 | 15.4 | 3.3 | 2.2 | 4.7 |

| 1965 | 181 | 35.8 | 100.0 | 38.8 | 23.7 | 7.9 | 2.9 | 14.5 | 3.3 | 5.8 | 3.2 |

| 1970 | 312 | 65.1 | 100.0 | 42.6 | 22.0 | 7.3 | 2.4 | 12.3 | 3.0 | 7.2 | 3.2 |

| 1971 | 341 | 72.0 | 100.0 | 42.8 | 22.1 | 7.0 | 2.3 | 11.9 | 2.8 | 7.8 | 3.2 |

| 1975 | 531 | 116.8 | 100.0 | 44.6 | 21.4 | 7.1 | 2.2 | 10.2 | 2.7 | 8.6 | 3.2 |

| 1979 | 825 | 188.9 | 100.0 | 45.6 | 21.3 | 7.1 | 2.5 | 9.1 | 2.4 | 9.3 | 2.7 |

| 1980 | 947 | 219.4 | 100.0 | 45.8 | 21.4 | 7.0 | 2.6 | 8.8 | 2.3 | 9.4 | 2.7 |

| 1981 | 1090 | 255.0 | 100.0 | 46.3 | 21.5 | 6.8 | 2.5 | 8.4 | 2.2 | 9.5 | 2.8 |

| Projections | |||||||||||

| 1983 | 1359 | 323.6 | 100.0 | 47.8 | 21.6 | 6.7 | 2.4 | 7.7 | 1.8 | 9.4 | 2.6 |

| 1985 | 1683 | 408.2 | 100.0 | 48.2 | 21.5 | 6.6 | 2.5 | 7.4 | 1.8 | 9.5 | 2.5 |

| 1990 | 2701 | 684.4 | 100.0 | 49.7 | 20.7 | 6.2 | 2.5 | 6.9 | 1.6 | 9.8 | 2.5 |

Total systems cost is called personal health care expenditures in Gibson and Waldo (1982).

The TSCPC concept captures indirect effects and leakages. If, for example, hospital rate setting restrains hospital inpatient costs, but implicitly provides pressures to substitute ambulatory and nursing-home care, TSCPC will capture the leakage from one health sector to another health sector. There can be both leakage from one sector and significant savings when the total net effect is considered.

Some questions relating to TSCPC are:

What is the magnitude of the leakage?

Is the nature of the leakage socially desirable? That is, what services and payers are affected, and what happens to prices, utilization, quality, and access for various socioeconomic groups?

Does TSCPC increase or decrease as it is related to the specific policy, regulation, or marketing strategy?

To provide further insight on leakage and indirect effects, we examine the relationship of substitutes and complements to TSCPC. There are significant substitute and complement relationships among various components of TSCPC (Davis and Russell, 1972; Feldstein, 1970; Hellinger, 1977; Russell, 1973). An example of a complementary relationship occurs when a patient incurs a physician expense to obtain a prescription drug, to be admitted to a hospital, or to purchase orthopedic appliances covered by third-party reimbursements.

To some extent hospital care and nursing-home care are both substitutes and complements. Due to medical, family, and/or financial reasons some segments of the patient population may receive institutional care in a hospital rather than a nursing-home setting or vice versa. Hospital care and nursing-home care are substitutes in the above example. On the other hand, patients may consecutively stay in a hospital, a nursing home, and at home (with home health care) depending upon the level of care needed. This switching of modalities of care reflects the complementary nature of hospital care, nursing home care, and home care.

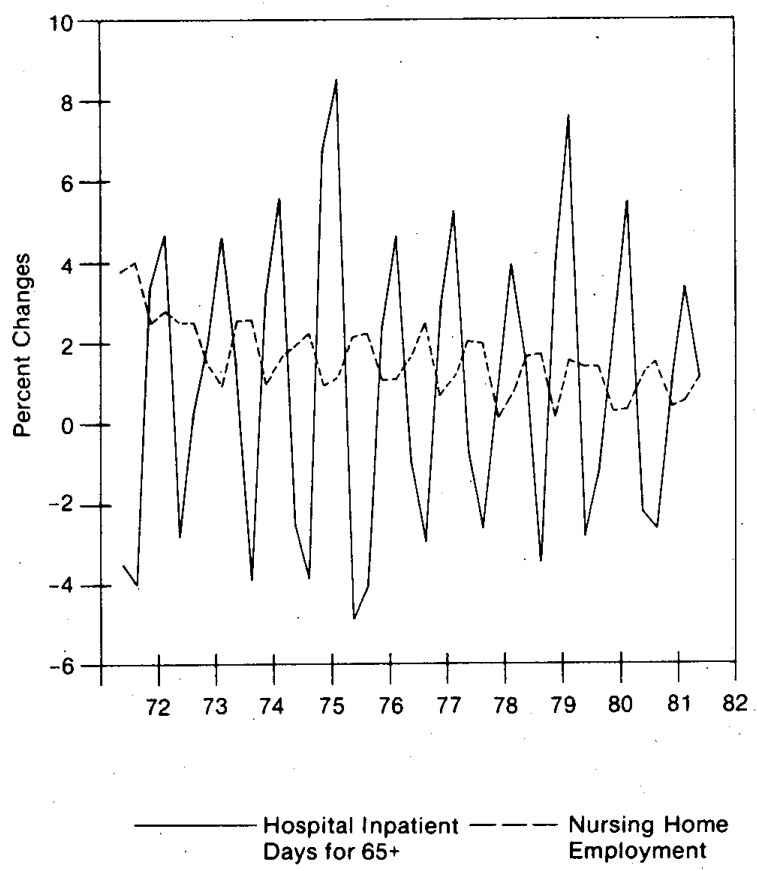

An inverse association between the nursing home sector and hospital care is illustrated in Figure 15. Over the period 1972 to mid-year 1982, quarter-to-quarter percent changes in community hospital inpatient days for the aged are negatively associated with quarter-to-quarter percent changes in total employment in the nursing-home sector.5 Quarterly nursing employment was used as a rough indicator of utilization of nursing home days (in the absence of utilization data). The causal factors (seasonal and nonseasonal) leading to this negative association need to be studied. Since a day in a community hospital costs 7 to 8 times as much as a day in a nursing home, it is important that patients be placed in the proper continuum of care.6

Figure 15. Quarterly Percent Changes in Community Hospital Inpatient Days for Aged and Nursing Home Employment, 1972 to 19821.

1Quarter-to-quarter percent changes are graphed, not percent changes from same quarter a year ago.

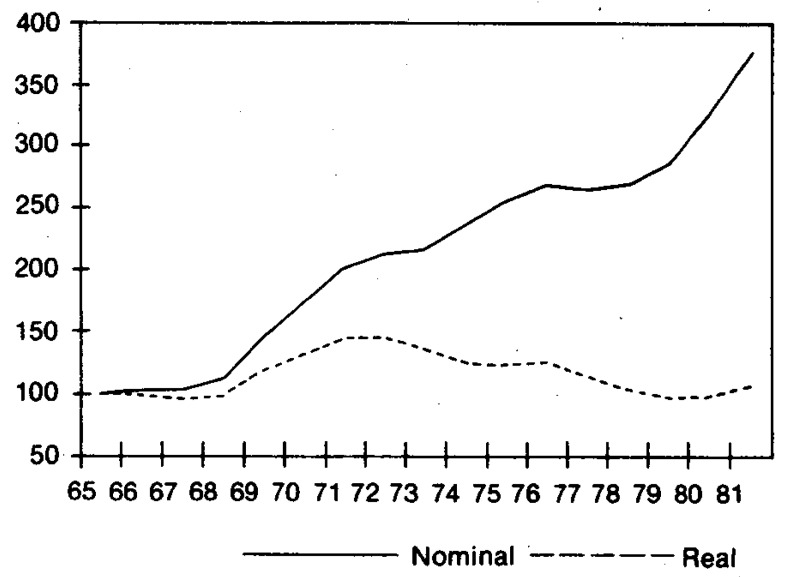

TSCPC: Historical Perspective

TSCPC has grown from $70 in 1950 to $1090 in 1981, an average annual rate of increase of 9.2 percent (Tables 5 and A-8). For the last decade (1971 to 1981) TSCPC increased at an average annual rate of 12.3 percent.

Table A-8. Average Annual Percent Increases in Per Capita Total Systems Cost and Per Capita GNP, Current Dollars and Constant Dollars, Selected Periods, 1950-1990.

| Selected Periods | Her capita Total Systems Cost1 | Per Capita GNP | Implicit Price Deflator for GNP | CPI-W3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Current Dollars | Constant Dollars2 | Current Dollars | Constant Dollars2 | |||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Average Annual Rates of Increase | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| 1950-1955 | 5.8% | 3.1% | 5.1 % | 2.5% | 2.6% | 2.2% |

| 1955-1960 | 6.7 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 2.0 |

| 1960-1965 | 7.0 | 5.3 | 4.9 | 3.2 | 1.6 | 1.3 |

| 1965-1970 | 11.6 | 7.0 | 6.4 | 2.1 | 4.2 | 4.3 |

| 1970-1975 | 11.2 | 4.3 | 8.2 | 1.5 | 6.6 | 6.8 |

| 1975-1980 | 12.3 | 4.7 | 10.0 | 2.6 | 7.3 | 8.9 |

| 1980-1985 | 12.2 | 4.5 | 8.8 | 1.4 | 7.3 | 7.6 |

| 1985-1990 | 9.9 | 4.4 | 7.5 | 2.1 | 5.3 | 5.2 |

| 1950-1981 | 9.2 | 4.8 | 6.4 | 2.0 | 4.3 | 4.4 |

| 1950-1965 | 6.5 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 1.8 |

| 1965-1981 | 11.9 | 5.3 | 8.3 | 2.0 | 6.2 | 6.8 |

| 1971-1981 | 12.3 | 4.6 | 9.4 | 1.9 | 7.4 | 8.4 |

| 1979-1981 | 14.9 | 5.1 | 9.1 | −0.3 | 9.4 | 11.8 |

| 1981-1983 | 11.7 | 4.5 | 7.7 | 0.8 | 6.8 | 6.9 |

| 1983-1985 | 11.3 | 4.3 | 9.1 | 2.2 | 6.8 | 7.0 |

| 1981-1990 | 10.6 | 4.4 | 7.9 | 1.8 | 5.9 | 6.0 |

Per capita total systems cost is called per capita personal health care expenditures in Gibson and Waldo (1982).

Per capita total systems cost and GNP were each deflated by the implicit price deflator for GNP (1972 = 100.0).

“Consumer Price Index—all items, wage earners” is shown for comparison only.

The composition of TSCPC has significantly shifted over time. Two institutional services, hospital care7 and nursing-home care, have significantly increased their relative shares over the period 1950-1981 rising from a combined share of 37 percent in 1950 to 56 percent in 1981 (Table 5). All ambulatory services and medical supplies have decreased their relative shares and noninstitutional services and medical supplies as a share of TSCPC have dropped from 63 percent to 44 percent during this period. In the last decade expenditures for services of physicians, dentists, and other professionals have maintained their relative shares of TSCPC. Drugs and medical sundries, eyeglasses and appliances, and other health services have declined in relative importance during this decade.

Sources funding TSCPC have also shifted substantially during the 1950 to 1981 period (Table 6). In 1950, patient direct payments accounted for nearly two-thirds of the financing. The Federal government, private health insurance, and State and local governments financed roughly 10 percent each (Table 6). During the period 1950 to 1965 Federal and State and local shares were fairly constant, but private health insurance grew very rapidly. In 1950, private insurance paid 9 percent, in 1965 that share had almost tripled to 24 percent. By 1981, the share reached 26 percent.

Table 6. Percentage Distribution of Total Systems Cost, by Source of Funds, Selected Years, 1950-19901.

| Calendar Year | Total Systems Cost Per Capita, Current Dollars | Total Systems Cost, Current Dollars | Total Systems Cost | Patient Direct Payments | All Third Parties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Total Private and Public | Private Health Insurance | Other Private | Public | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Total | Federal | State and Local | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Historical Estimates | (Amount in dollars) | (Amount in billions) | Percentage Distribution | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| 1950 | $ 70 | $ 10.9 | 100.0% | 65.5% | 34.5% | 9.1 % | 2.9% | 22.4% | 10.4% | 12.0% |

| 1960 | 129 | 23.7 | 100.0 | 54.9 | 45.1 | 21.1 | 2.3 | 21.8 | 9.3 | 12.5 |

| 1965 | 181 | 35.8 | 100.0 | 51.8 | 48.2 | 24.4 | 2.2 | 21.6 | 10.1 | 11.4 |

| 1970 | 312 | 65.1 | 100.0 | 39.9 | 60.1 | 24.0 | 1.6 | 34.5 | 22.3 | 12.2 |

| 1971 | 341 | 72.0 | 100.0 | 38.6 | 61.4 | 24.1 | 1.7 | 35.6 | 23.3 | 12.3 |

| 1975 | 531 | 116.8 | 100.0 | 33.4 | 66.6 | 25.8 | 1.4 | 39.5 | 26.9 | 12.6 |

| 1979 | 825 | 188.9 | 100.0 | 32.7 | 67.3 | 26.6 | 1.4 | 39.3 | 28.2 | 11.1 |

| 1980 | 947 | 219.4 | 100.0 | 32.9 | 67.1 | 26.0 | 1.4 | 39.7 | 28.6 | 11.2 |

| 1981 | 1090 | 255.0 | 100.0 | 32.1 | 67.9 | 26.2 | 1.4 | 40.4 | 29.3 | 11.1 |

| Projections | ||||||||||

| 1983 | 1359 | 323.6 | 100.0 | 32.1 | 67.9 | 26.3 | 1.4 | 40.2 | 29.2 | 11.0 |

| 1985 | 1683 | 408.2 | 100.0 | 32.2 | 67.8 | 26.4 | 1.4 | 40.0 | 29.5 | 10.5 |

| 1990 | 2701 | 684.4 | 100.0 | 30.9 | 69.0 | 26.1 | 1.3 | 41.6 | 31.5 | 10.1 |

Total systems cost is called personal health care expenditures in Gibson and Waldo (1982).

Medicare and Medicaid took effect in mid-1966 and by 1967 the Federal government's share of TSCPC advanced to 21 percent; the State and local government share stayed roughly constant at 13 percent; and patient direct payments dropped to 43 percent.

By 1981 the percentages paid by the major payers were as follows: patient direct payments, 32 percent; private health insurance, 26 percent; Federal government, 29 percent; and State and local governments, 11 percent (Table 6).

Inflation-adjusted8 TSCPC increased at an average annual rate of 4.8 percent for the period, 1950 to 1981 (Tables A-7 and A-8) and during the last ten years at a 4.6-percent rate. A higher annual rate of 5.1 was experienced in the period 1979 to 1981 while inflation-adjusted GNP per capita had a —0.3 average annual rate of change (Table A-8).

Table A-7. Per Capita Total Systems Cost, Nominal and Constant Dollar, Selected Years, 1950-1990.

| Calendar Year | Total Systems Cost Per Capita1 Current Dollars | Total Systems Cost Per Capita Constant Dollars2 | Gross National Product Per Capita, Current Dollars | Total Systems Cost as Percent of GNP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Historical Estimates | ||||

|

|

||||

| 1950 | $ 70 | $131 | $1,852 | 3.8% |

| 1960 | 129 | 187 | 2,755 | 4.7 |

| 1965 | 181 | 243 | 3,492 | 5.2 |

| 1970 | 312 | 342 | 4,759 | 6.6 |

| 1971 | 341 | 355 | 5,100 | 6.7 |

| 1975 | 531 | 422 | 7,045 | 7.5 |

| 1979 | 825 | 505 | 10,555 | 7.8 |

| 1980 | 947 | 530 | 11,365 | 8.3 |

| 1981 | 1,090 | 557 | 12,555 | 8.7 |

| Projections | ||||

|

|

||||

| 1983 | 1,359 | 609 | 14,562 | 9.3 |

| 1985 | 1,683 | 662 | 17,348 | 9.7 |

| 1990 | 2,701 | 822 | 24,879 | 10.9 |

Total systems cost per capita is called per capita personal health care expenditures in Gibson and Waldo (1982).

Per capita total systems cost was deflated by the implicit price deflator for GNP (1972= 100.0). See Table 1 for values of the deflator.

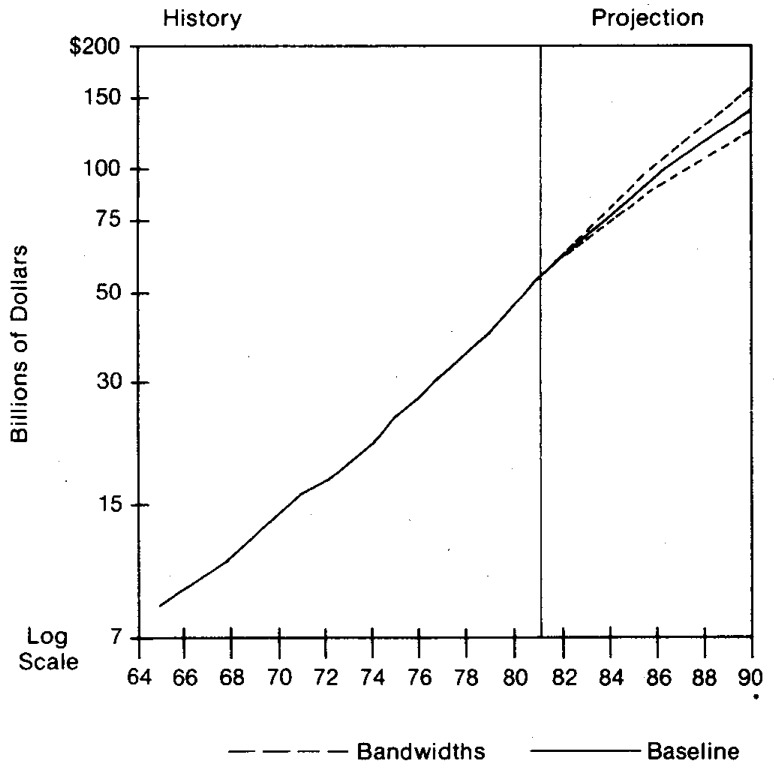

TSCPC Projections

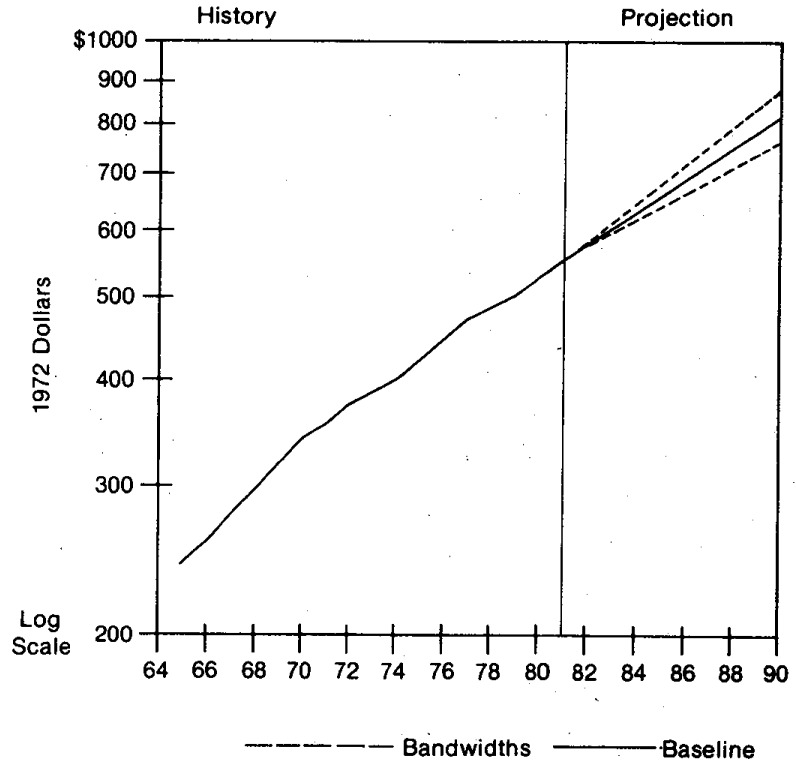

In the baseline projections current dollar TSCPC rises at an average annual rate of 10.6 percent from 1981 to 1990 (Table A-8 and Figure 7), substantially below the 1971-1981 rate of 12.3 percent and reflecting significant deceleration of inflation. Inflation-adjusted TSCPC is expected to increase at an average annual rate of 4.4 percent during the 1981 to 1990 period with a range of approximately 3.6 percent to 5.2 percent. This range of estimates reflects historical variability in the growth of inflation-adjusted TSCPC (Table A-15 and Figure 8).

Figure 7. Total Systems Cost Per Capita 1965 to 1990, with Bandwidth Intervals1 2.

1The bandwidth intervals around the baseline projection scenario provide one indicator of variability. The standard error associated with annual percent increases in total systems cost per capita for 1966-1981 (see Table A-15) was multiplied by a t-distribution value of 2.131 to derive the bandwidth intervals. The calculated bandwidth intervals are approximate and are used as a rough guide in assessing variability and uncertainty.

2Total systems cost per capita is also referred to as personal health care spending per capita.

Table A-15. Measures of Central Tendency and Variability for Year-to-Year Changes in Total Systems Cost Per Capita and GNP Per Capita, 1966-19811.

| Variable | Measures of Variability2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Measures of Central Tendency | Standard Deviation | Standard Error | Coefficient of Variation of Mean3 | ||

|

| |||||

| Mean | MEDIAN | ||||

| Total Systems Cost Per Capita, Current Dollars | 11.9% | 11.9% | 1.8% | 0.470% | 0.039 |

| Implicit Price Deflator for GNP | 6.3 | 5.6 | 2.2 | 0.560 | 0.090 |

| Total Systems Cost Per Capita Deflated by Implicit Price Deflator for GNP | 5.3 | 5.4 | 1.5 | 0.383 | 0.072 |

| Per Capita GNP, Current Dollars | 8.3 | 8.2 | 2.1 | 0.550 | 0.066 |

| Per Capita GNP, Constant Dollars | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 0.625 | 0.312 |

| Total Systems Cost as a Percent of GNP | 3.3 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 0.732 | 0.222 |

There are 16 annual percent changes for the period 1966-1981.

ln textbook examples, measures of variability typically measure sampling variability, that is, variations that might occur by chance because a sample of the population is surveyed. As calculated in this paper (and for typical applied time-series analyses) measures of variability also reflect variability associated with evolving causal structures and variability associated with various types of nonsampling errors such as data processing mistakes, nonresponse, misreporting by respondents, etc. The calculated measures are approximate and are meant as a general guide. It is important to keep in mind the potential dangers of extrapolating historical measures of variability into the future. That is, there can be no guarantee that future variability will replicate historical variability.

For cautions in using the coefficient of variation when the mean of the variable measures change, see Kish (1965, pp. 47-49).

Figure 8. Constant Dollar Total Systems Cost Per Capita 1965 to 1990, with Bandwidth Intervals1 (Inflation-Adjusted to 1972 Dollars)2.

1The bandwidth intervals around the baseline projection scenario provide one indicator of variability. The standard error associated with annual percent increases in constant dollar (inflation adjusted) total systems cost per capita for 1966-1981 (see Table A-15) was multiplied by a t-distribution value of 2.131 to derive the bandwidth intervals. The calculated bandwidth intervals are approximate and are used as a rough guide in assessing variability and uncertainty.

2Total systems cost per capita (personal health care spending per capita) was deflated by the implicit price deflator for the GNP.

In the 1980's we expect to see a continuation of the historical pattern of institutional care increasing its share of TSCPC. We do expect some modifications in light of the underlying fiscal pressures, demographic shifts and new technologies.

Demographic shifts in the age composition of the population, fiscal pressures of the Federal and State and local governments, changes in the mix of services (see Table 5), and pressures on employers and individuals to increase deductibles and coinsurance on private health insurance plans (Lawson, 1982) all contribute to shifts in the expected sources of financing for TSCPC in the 1980's (Table 6).

In the following section, we will explore the impact of these factors on the various individual sectors of the health care industry.

Projection Trends by Type of Health Expenditures

In this section, we present highlights relating to projection trends for each of the 12 types of expenditures. First, we provide a historical perspective with commentary on factors influencing expenditure growth. Second, we present a synopsis of the short-term outlook and the long-term projections. Third, we include highlights of projections of sources of funds.

Hospital Care

Total Hospital Care: Historical Perspective

In this age of complex technologies and procedures, hospitals have become the focal point of the health industry. Hospital care as a percent of total system costs, increased from 35 percent in 1950 to 46 percent in 1981 and is expected to garner an increased share by 1990 (Table 5). The $118 billion spent on hospital care in 1981 (Table 7) comprises 4 percent of GNP. To put this expenditure amount into perspective, as it relates to services provided: in 1981 6,933 hospitals with 1.4 million beds handled 39.2 million admissions and provided 387 million patient days of service. In addition, 265 million outpatient visits were provided (American Hospital Association, 1982). Although the 10-percent proportion of the population with one or more hospital episodes has not changed in the last decade (Table A-20), the intensity and sophistication of care has increased substantially (Figure 5). We first examine total hospital costs and then present synopses of spending patterns in the major hospital components.

Table 7. National Health Expenditures by Type of Expenditure, Selected Years, 1950-1990.

| Historical Estimates | Projections | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1971 | 1975 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1983 | 1985 | 1990 | |

| (amount in billions) | |||||||||||

| Total | $12.7 | $26.9 | $74.7 | $83.3 | $132.7 | $215.0 | $249.0 | $286.6 | $362.3 | $465.4 | $755.6 |

| Health Services and Supplies | 11.7 | 25.2 | 69.3 | 77.2 | 124.3 | 204.5 | 237.1 | 273.5 | 347.4 | 438.4 | 728.9 |

| Personal Health Care | 10.9 | 23.7 | 65.1 | 72.0 | 116.8 | 188.9 | 219.4 | 255.0 | 323.6 | 408.2 | 684.4 |