Abstract

This study reports on the use of services by Medicare enrollees who died in 1978. Decedents comprised 5.9 percent of the study group but accounted for 28 percent of Medicare expenditures. The use of services became more intense as death approached. Despite the idea that heroic efforts to prolong life are common, only 6 percent of persons who died had more than $15,000 in Medicare expenses in their last year of life. As shown here, the unique patterns of health care use by decedents and survivors should be fully understood and considered when contemplating changes in the Medicare program.

Introduction

The types and costs of health care services rendered to the dying are currently issues of widespread concern. The concern stems from a belief that care for the dying centers too much around highly technical, cure-oriented services provided in the hospital. Critics hold that insufficient attention is paid to the psychosocial needs of the dying and their families.

Concern also stems from the belief that the cost of care provided in conventional settings may be high, especially when compared with alternatives such as hospice programs (Bloom and Kissick, 1980; Fletcher, 1980; Krant, 1978; Mount, 1976; Ryder and Ross, 1977). Cost concerns are reinforced by studies showing the large proportion of deaths among high-cost hospital patients. Interest has focused on such high-cost users of health care, both because such persons are most in need of protection against costs for catastrophic illness, and because of the belief that their experiences may help to provide an understanding of the nature of the continuing escalation of health costs (Birnbaum, 1978; Cullen et al., 1976; Schroeder, Showstack, and Roberts, 1979; Schroeder, Showstack, and Schwartz, 1981; Zook and Moore 1980; Zook, Moore, and Zeckhauser, 1981).

One result of concern about appropriate health care for the dying has been the passage of the Medicare hospice benefit, which took effect in November 1983. Since many advocates of the hospice concept believe that hospice care may be less costly as well as more emotionally and medically beneficial, there is interest in comparing patterns of use of health care in hospices and in conventional settings. The data presented in this article are one source of information about the use of conventional care before death.

Studies of health care expenses in the period before death have differed in methods and populations studied but have found that total expenses (Piro and Lutins, 1973; McCall, to be published) or hospital expenses (Timmer and Kovar, 1971; Scotto and Chiazze, 1976) are much greater for dying persons than for others. Other studies have examined the relationships of age to hospital and nursing home use by dying persons. These studies found that hospital use, as measured by days of care, was greatest among persons 45-64 years of age who died, and that nursing home use was greatest among persons 65 years of age or over who died (Wunderlich and Sutton, 1966). The percent of deaths occurring in hospitals was highest among patients who were under 45 years of age; the percent occurring in nursing homes was highest among individuals 65 years of age or over (Sutton, 1965).

A study of the use of services in the last year of life by cancer patients covered by Blue Cross and Blue Shield found that hospital expenses made up a high proportion of total expenses and that the use of services was especially intense during the last 2 months of life (Gibbs and Newman, 1982). A study of the use of Medicare services by enrollees in the last year of life in Colorado also found intense use of services in the last few months of life (McCall, to be published). Additionally, this study found that persons who died had 6.4 times the average charges per enrollee in their last year as persons who did not die.

An earlier study of the Medicare population found that people who died during 1967 comprised 5 percent of enrollees but accounted for 22 percent of program expenditures (Piro and Lutins, 1973). That study examined services only for the calendar year in which the enrollee died. A later study with 1979 Medicare data also examined services only in the calendar year in which the enrollee died (Helbing, 1983). It found that 21 percent of Medicare expenditures were for persons who died—almost exactly the same figure found in the Piro and Lutins paper.

This article differs from earlier works on the use of health care in the period before death because it:

Traces back the use of services for 2 full years before death.

Presents national population-based data (for example, rates per 1,000 enrollees) for both decedents and survivors.

Presents data on the use of physicians', and other types of services in addition to hospital services.

This article reports on the use of and Medicare payments for services in the last and second-to-last years of life for aged enrollees who died in 1978 (decedents). It contrasts the use of services by decedents with the use by persons who did not die (survivors) to focus on the added use of Medicare services associated with dying. It describes the types, numbers, and costs of services received before death and explores the relationships of such characteristics as age, time before death, and hospital diagnosis, to the use of services. It describes the cost-sharing liabilities for Medicare enrollees in their last year. Finally, it examines trends over time in the relationship of the relative proportion of Medicare expenditures for decedents compared to survivors.

In 1978, of all persons who died in the United States, 1.3 million or 67 percent were Medicare enrollees 65 years of age or over. Since its beginning in July 1966, Medicare has insured about 95 percent of all persons 65 years of age or over against the costs of hospital and medical care. The vast majority of Medicare enrollees become entitled at age 65 and remain covered until death. Thus, the experience of Medicare enrollees offers an optimal opportunity to study the costs of care before death.

Methods

Data source

Data for this study come from a longitudinal file of Medicare enrollees known as the Continuous Medicare History Sample (CMHS). The file—which begins with 1974 data—records the continuing experience of a 5-percent probability sample of Medicare enrollees selected by their Medicare identification numbers. The file is part of the Medicare Statistical System, which collects information from Medicare claims for services submitted by physicians, hospitals, and other providers. New enrollees whose identification numbers place them in the CMHS are added to the sample, and the records of enrollees who die are retained in the file. Information on the use of Medicare services (and on the month of death for decedents) is appended to enrollees' records in periodic updates. Because the data are based on a sample of enrollees, there are sampling errors associated with the estimates. Sampling error tables are available from the authors.

The data are limited to the use of Medicare-covered services and Medicare reimbursements for these services. Medicare covers the following services:

Hospital inpatient.

Skilled nursing facility (SNF).

Home health agency (HHA).

Physicians' and other medical.

Hospital outpatient.

Services of importance to the aged not covered by Medicare are nursing home care below the skilled level and drugs for outpatients.

The enrollee is responsible for deductibles and coinsurance for Medicare-covered services. In 1978, Medicare paid an estimated 44 percent of personal health care expenditures for persons 65 years of age or over, including 75 percent of expenditures for hospital care (both inpatient and outpatient), 56 percent of expenditures for physicians' services, and 3 percent of expenditures for nursing home care (Fisher, 1980). Thus, the data in this article reflect most hospital costs, about half of physician expenses, but only a small percent of nursing home costs for Medicare enrollees.

The reliability of the hospital diagnosis in the Medicare Statistical System was studied by the Institute of Medicine (Institute of Medicine, 1977). For some conditions, the study found large rates of disagreement between the diagnosis in the Medicare record and the diagnosis in the hospital medical record for the same case. Thus, when examining data by diagnosis, emphasis should be given to large differences in broad diagnostic groups, rather than small differences in individual diagnoses.

Study design

Medicare enrollees who died in 1978 (decedents) were identified and their use of services was traced back 2 years from the month of death. Their experience is compared with that of enrollees who survived through 1978 (survivors). Specifically, use of Medicare-covered services in the last year of life by decedents is compared with the 1978 Medicare use by survivors. Medicare use in the second-to-last year of life by decedents is compared with the 1977 experience of survivors. The study is restricted to enrollees 65 years of age or over; disabled enrollees under 65 years of age are not included.

Because the experience of decedents is traced back 2 years from 1978, the study population was confined to persons who were also enrolled in 1977 and 1976. Consequently, no persons 65 or 66 years of age are in the study group.

To simplify analyses, the study was restricted to persons enrolled for both the Hospital Insurance and Supplementary Medical Insurance parts of Medicare. Such persons make up about 95 percent of all aged enrollees. As a result of exclusion of persons 65 and 66 years of age and of persons not enrolled in both parts of Medicare, the study group represents 80 percent of the 25.8 million aged ever enrolled in Medicare in 1978 including 88 percent of the 1.3 million decedents, and 75 percent of the 24.5 million survivors.

The numbers of persons in the study group by age and survival status are shown in Table 1. Of the 19.5 million total Medicare enrollees 67 years of age or over, 1.1 million or 5.9 percent died in 1978. The percent of decedents was higher for successively older age groups; decedents represented 2.8 percent of the 67-69 age group and 14.7 percent of the 85 or over group.

Table 1. Number of enrollees in study group, by age and survival status: 1978.

| Decedents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Age | Total | Survivors | Number | Percent |

| 67 years or over | 19,483,600 | 18,342,040 | 1,141,560 | 5.9 |

| 67-69 years | 3,643,340 | 3,541,560 | 101,780 | 2.8 |

| 70-74 years | 6,115,340 | 5,892,860 | 222,480 | 3.6 |

| 75-79 years | 4,496,120 | 4,250,400 | 245,720 | 5.5 |

| 80-84 years | 2,992,120 | 2,748,420 | 243,700 | 8.1 |

| 85 years or over | 2,236,680 | 1,908,800 | 327,880 | 14.7 |

NOTE: Data are from a 5-percent sample of Medicare enrollees. Counts have been multiplied by 20 to estimate totals.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration: Data from the Medicare Statistical System.

Data on 1978 Medicare reimbursements for survivors reflect expenses from January to December 1978. However, reimbursements for the last 12 months of life for 1978 decedents extend back into 1977 and represent, on the average, expenses from July 1977 to June 1978. To make reimbursement data comparable for each group, data for decedents were adjusted for 6 months of inflation by using the Medical Care Component of the Consumer Price Index. Data for survivors for 1977 and for the second-to-last year of life for decedents were also adjusted to 1978 to account for inflation.

Other studies (Piro and Lutins, 1973; Helbing, 1983) on the use of Medicare services in the last year of life analyzed Medicare reimbursements in a calendar year, thereby including only those services in the calendar year in which the enrollee died. This study includes all services in the month of death and in the 11 preceding months (or the 12th through the 24th preceding months for data on the second-to-last year of life). Hospital stays with a discharge date within 12 months of death are included in the last year as are SNF stays in which the admission date occurred within 12 months of death. For other services—physicians' and other medical, home health, and outpatient hospital—the CMHS does not record the date of service but maintains only a calendar year total of services. For these, all services in the calendar year in which the enrollee died were included. Then a simple algorithm was used to include a proportion of services used in the preceding calendar year. For instance, if an enrollee died in June 1978, the 6th month, then or of services and reimbursements in 1977 would be included in the last year of life in addition to all 1978 services. For the next-to-the-last year of life, the preceding 12 months of data were used. Data on survivors are for calendar years 1978 and 1977.

Findings

Overall patterns of use

A large percent of Medicare funds is devoted to enrollees in their last year of life. The 1.1 million decedents were 5.9 percent of the study group, but they accounted for 27.9 percent of expenditures. Survivors were 94.1 percent of the study group, and they accounted for 72.1 percent of expenditures.

Examination of rates of use of services by decedents and survivors illustrates the wide differences in the experience of the two groups (Table 2). Of decedents, 92 percent used some Medicare-reimbursed service in their last year of life, and 80 percent were users 1 in the second-to-last year. Of survivors, 58 percent were users in 1978 and 55 percent were users in 1977. Little is known about the enrollees with no Medicare reimbursement in their last year of life. That group might include persons who died suddenly or persons in Federal hospitals, such as Veterans hospitals, who are not eligible for Medicare reimbursement. Medicare users who died in 1978 were reimbursed an average of $4,909 for services in their last year and $1,842 for services in their second-to-last year, compared with $1,253 in 1978 and $1,147 in 1977 for survivors.

Table 2. Selected measures of use of Medicare benefits by decedents in their last and second-to-last years of life, and survivors in 1977 and 1978.

| Period | Survival status | Decedents-to-survivors ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Decedents | Survivors | ||

| Persons served 1 as a percent of enrollees | |||

| Last year (1978) | 92 | 58 | 1.6 |

| Second-to-last year (1977) | 80 | 55 | 1.4 |

| Average reimbursement per person served | |||

| Last year (1978) | $4,909 | $1,253 | 3.9 |

| Second-to-last year (1977) | 1,842 | 1,147 | 1.6 |

| Average reimbursement per enrollee | |||

| Last year (1978) | $4,527 | $729 | 6.2 |

| Second-to-last year (1977) | 1,481 | 635 | 2.3 |

Persons served are enrollees with some Medicare reimbursement.

NOTES: Data for the last year of life for decedents in 1978 are compared with the 1978 experience of survivors. Data for the second-to-last year of life are compared to the 1977 experience of survivors. Data are expressed in 1978 dollars.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration: Data from the Medicare Statistical System.

The large differences between decedents and survivors in the proportion of users and in average reimbursement per user are reflected in the differences found in average reimbursements per enrollee (Table 2). Reimbursement per enrollee is the product of the proportion of persons served and average reimbursement per user. The Medicare program spent an average of $4,527 on behalf of enrollees in their last year of life, a figure 6.2 times greater than the $729 spent per enrollee for survivors in 1978. In the decedents' second-to-last year of life, the difference was not as great; but expenditures per enrollee were still 2.3 times greater for decedents than for survivors in 1977 ($1,481 versus $635). Thus, the greater use of health services associated with mortality extends back at least into the second-to-last year of life.

Patterns in the use of Medicare benefits differed by age between decedents in their last year and survivors in 1978 (Table 3). Persons served as a percent of enrollees varied little by age for decedents and increased moderately with age for survivors. However, the two groups showed opposite patterns by age in reimbursement per person served. For decedents, Medicare reimbursement per person served was lower for successively older age groups. Reimbursement per person served for decedents 85 years of age or over ($3,598) was only 57 percent of the amount for decedents 67-69 years of age ($6,354). In contrast, for survivors, reimbursement per person served increased for successively older age groups with survivors 85 years of age or over receiving 28 percent more reimbursement per person served than those 67-69 years of age ($1,421 versus $1,109).

Table 3. Selected measures of use of Medicare benefits by decedents in their last year of life, and survivors in 1978, by age.

| Age | Survival status | Decedents-to-survivors ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Decedents | Survivors | ||

| Persons served1 as a percent of enrollees | |||

| 67 years or over | 92 | 58 | 1.6 |

| 67-69 years | 91 | 53 | 1.7 |

| 70-74 years | 93 | 56 | 1.6 |

| 75-79 years | 93 | 60 | 1.5 |

| 80-84 years | 93 | 62 | 1.5 |

| 85 years or over | 91 | 63 | 1.5 |

| Average reimbursement per person served | |||

| 67 years or over | $4,909 | $1,253 | 3.9 |

| 67-69 years | 6,354 | 1,109 | 5.7 |

| 70-74 years | 5,897 | 1,181 | 5.0 |

| 75-79 years | 5,433 | 1,285 | 4.2 |

| 80-84 years | 4,617 | 1,391 | 3.3 |

| 85 years or over | 3,598 | 1,421 | 2.5 |

| Average reimbursement per enrollee | |||

| 67 years or over | $4,527 | $729 | 6.2 |

| 67-69 years | 5,801 | 592 | 9.8 |

| 70-74 years | 5,466 | 668 | 8.2 |

| 75-79 years | 5,056 | 771 | 6.5 |

| 80-84 years | 4,274 | 859 | 5.0 |

| 85 years or over | 3,285 | 889 | 3.7 |

Persons served are enrollees with some Medicare reimbursement.

NOTE: Data are expressed in 1978 dollars.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration: Data from the Medicare Statistical System.

Reimbursement per enrollee followed the same pattern as reimbursement per user. It decreased for successively older age groups for decedents and increased for successively older age groups for survivors (Table 3). Reimbursement per enrollee for decedents 85 years of age or over ($3,285) was only 57 percent of the amount for decedents 67-69 years of age ($5,801). Reimbursement per enrollee for survivors 85 years of age or over ($889) was 50 percent greater than the amount for survivors 67-69 years of age ($592). As discussed later, total expenditures per enrollee from all sources may not be lower for older age groups. Older age groups of decedents seemed to use more nursing home care, but Medicare pays for only a small portion of such care.

Impact of mortality on age-specific reimbursement rates

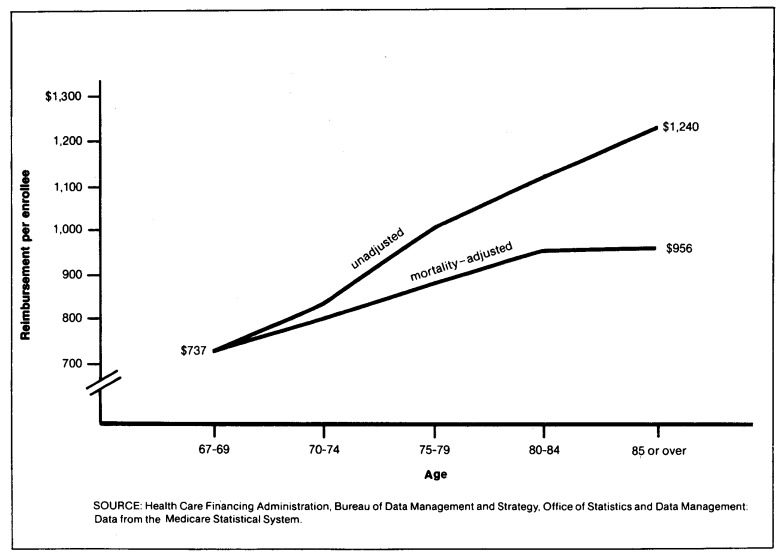

Data from the Medicare program have long shown that average Medicare reimbursement per enrollee is higher for older age groups. To what extent does this reflect higher mortality rates among the older aged rather than increased Medicare use with age, per se? To answer this question “mortality-adjusted” rates of reimbursement per enrollee were computed.2 The mortality adjustment used the age-specific reimbursement rates for decedents and survivors found in this study (Table 3) and weighted them by the mortality rate of 28 deaths per 1,000 persons for the youngest group, persons 67 to 69 years of age (Table 1). This procedure gave age-specific reimbursement rates under the assumption that all age groups had the same death rate as the youngest group of the aged.

The unadjusted rate of reimbursement per enrollee increased from $737 per enrollee for persons 67 to 69 years of age to $1,240 per enrollee for persons 85 or over (Figure 1). However, the mortality-adjusted rate increased only from $737 for persons 67 to 69 years of age to $956 per enrollee for persons 85 years of age or over. Thus, much of the higher average reimbursement per enrollee at older ages is due to higher mortality.

Figure 1. Unadjusted and mortality-adjusted rates of reimbursement per enrollee: 1978.

Distribution of Medicare reimbursements

As expected, an examination of the distribution of enrollees by amounts reimbursed shows that a much higher proportion of decedents than survivors had high Medicare reimbursements (Table 4). Among decedents, 7 percent had from $10,000 to $14,000 in Medicare reimbursement in their last year of life and another 3 percent had from $15,000 to $19,000 in reimbursement. Two percent of decedents, had very high reimbursements of $20,000 to $29,999 and 1 percent had $30,000 or more. Reimbursements for decedents in these four highest reimbursement intervals accounted for 45 percent of all reimbursements for decedents. In contrast, only 1 percent of survivors had reimbursements of $10,000 or more. Such persons accounted for 21 percent of all reimbursements for survivors.

Table 4. Distribution of Medicare enrollees and Medicare reimbursements by decedents in their last year of life, and survivors in 1978, by reimbursement interval.

| Reimbursement Interval | Survival status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Decedents | Survivors | |||

|

|

|

|||

| Number of enrollees in thousands | Amount of reimbursements in millions | Number of enrollees in thousands | Amount of reimbursements in millions | |

| Total | 1,142 | $4,969 | 18,342 | $13,365 |

| No reimbursement | 89 | 0 | 7,679 | 0 |

| Less than $100 | 86 | 4 | 3,597 | 159 |

| $100 to $1,999 | 336 | 279 | 5,111 | 2,917 |

| $2,000 to $4,999 | 274 | 919 | 1,252 | 3,984 |

| $5,000 to $9,999 | 217 | 1,546 | 516 | 3,540 |

| $10,000 to $14,999 | 84 | 1,024 | 124 | 1,485 |

| $15,000 to $19,999 | 32 | 552 | 37 | 627 |

| $20,000 to $29,999 | 19 | 439 | 20 | 479 |

| $30,000 and over | 5 | 205 | 5 | 173 |

| Percent distribution | ||||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| No reimbursement | 8 | 0 | 42 | 0 |

| Less than $100 | 8 | (1) | 20 | 1 |

| $100 to $1,999 | 29 | 6 | 28 | 22 |

| $2,000 to $4,999 | 24 | 18 | 7 | 30 |

| $5,000 to $9,999 | 19 | 31 | 3 | 26 |

| $10,000 to $14,999 | 7 | 21 | 1 | 11 |

| $15,000 to $19,999 | 3 | 11 | (1) | 5 |

| $20,000 to $29,999 | 2 | 9 | (1) | 4 |

| $30,000 and over | 1 | 4 | (1) | 1 |

Less than 1 percent.

NOTES: Unlike other reimbursement data in this article, dollar figures for decedents in this table could not be adjusted for the 6-month difference in data for decedents and survivors. Thus, the concentration of decedents in the higher reimbursement intervals as compared to survivors is slightly understated. Parts may not add to totals because of rounding.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration: Data from the Medicare Statistical System.

Also, a much smaller proportion of decedents than survivors had low reimbursements. Among decedents, 8 percent had no reimbursement and another 8 percent had less than $100. Among survivors, 42 percent had no reimbursement and 20 percent had less than $100.

These differences are reflected in the proportion of decedents found among very high users of Medicare benefits. In 1978, about one of every two enrollees with $20,000 or more in reimbursements died that year, and about one out of two survived through the year. As noted earlier, decedents were 5.9 percent and survivors were 94.1 percent of the study population.

Beneficiary liability

High expenses for decedents raise the question of the amount of their liability for Medicare deductibles and coinsurance. Under Part A (Hospital Insurance) of Medicare, for each benefit period the patient is liable for payment of an inpatient hospital deductible ($144 in 1978). The beneficiary is also responsible for coinsurance for the 61st to the 90th day of hospital care, for all lifetime reserve hospital days, and for the 21st to the 100th day of skilled nursing care. Under Part B (Supplementary Medical Insurance) there is a yearly deductible ($60 in 1978) and coinsurance of 20 percent of allowed charges. Many enrollees buy “Medigap” policies to cover deductibles and coinsurance. Concern about out-of-pocket expenses for deductibles and coinsurance and about the costs of Medigap policies has given rise to studies of ways to restructure Medicare and place a limit on beneficiary liability (Gornick et al., 1983; Advisory Council on Social Security, 1983).

As would be expected from their higher use of services, a much larger percent of decedents than survivors have high amounts of liability for deductibles and coinsurance. Among decedents, 25 percent had from $500 to $999 in liability and another 9 percent had $1,000 or more in liability (Table 5). The corresponding figures for survivors were only 5 and 1 percent. Conversely, only 13 percent of the decedents, but fully 56 percent of the survivors, had less than $100 in liability.

Table 5. Distribution of Medicare enrollees and amounts of liability for coinsurance and deductibles by decedents in their last year of life, and survivors in 1978, by liability interval.

| Amount of liability | Survival status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Decedents | Survivors | |||

|

|

|

|||

| Number of enrollees in thousands | Amount of liability in millions | Number of enrollees in thousands | Amount of liability in millions | |

| Total | 1,142 | $507 | 18,320 | $1,994 |

| Less than $100 | 154 | 1 | 10,351 | 62 |

| $100 to $199 | 102 | 8 | 3,731 | 273 |

| $200 to $499 | 493 | 137 | 3,127 | 825 |

| $500 to $999 | 285 | 77 | 941 | 564 |

| $1,000 and over | 107 | 183 | 170 | 269 |

| Percent distribution | ||||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Less than $100 | 13 | (1) | 56 | 3 |

| $100 to $199 | 9 | 2 | 20 | 14 |

| $200 to $499 | 43 | 27 | 17 | 41 |

| $500 to $999 | 25 | 35 | 5 | 28 |

| $1,000 and over | 9 | 36 | 1 | 14 |

Less than 1 percent.

NOTES: Unlike other financial data in this article, dollar figures for decedents in this table could not be adjusted for the 6-month difference in data for decedents and survivors. Thus, the concentration of decedents in the higher liability intervals as compared to survivors is slightly understated. Parts may not add to totals because of rounding.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration: Data from the Medicare Statistical System.

Intensity of use of services

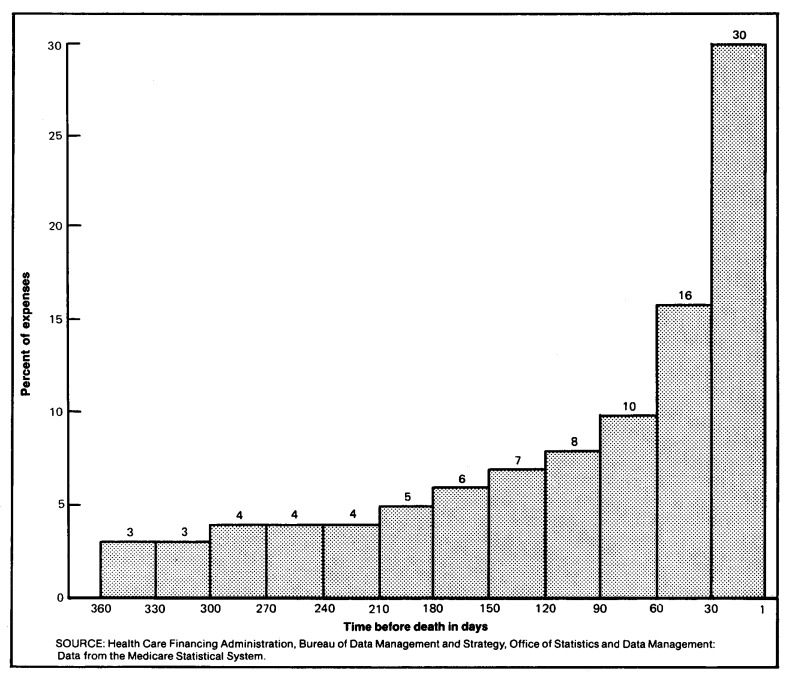

The use of Medicare services becomes much more intense as death approaches. Data from 1976 show that of all expenses in the last year of life, 30 percent was spent in the last 30 days and another 16 percent in the 60th to the 31st day before death (Figure 2). To a large extent, this reflects the intense use of expensive hospital care in the final months. For example, hospital reimbursements in the last 60 days of life accounted for about 50 percent of all hospital expenses in the last year.

Figure 2. Percent of Medicare expenses in the last year of life, according to selected time intervals before death: United States, 1976.

Data like those in Figure 2 also were calculated for patients with hospital stays for cancer because of the interest in hospice care for cancer patients. Hospice care became a Medicare-covered benefit beginning November 1983. An estimated 93 percent of patients in hospices suffer from cancer (Duzor, 1983). It was found that the percent distribution of expenses by month in the last year of life for cancer patients was virtually identical to that for all decedents shown in Figure 2.

Expenses in the last months of life are a significant part of total Medicare expenses. In 1976, reimbursements for the last 180 days of life for decedents equalled 21 percent of total Medicare expenses for all persons (decedents and survivors), and reimbursements in just the last 30 days of life made up 8 percent of total Medicare expenditures.

Use by type of service

For each type of service, average Medicare reimbursement per enrollee was higher for decedents in their last and second-to-last years than for the comparison group of survivors (Table 6). The highest rates of reimbursement for both decedents and survivors were found for hospital and physicians' services. Average reimbursement per decedent for hospital care was 7.3 times higher in the last year and 2.4 times higher in the second-to-last year than for the comparison group of survivors. Reimbursements for hospital care comprised 77 percent of the total reimbursements for decedents in their last year and 66 percent for survivors in 1978. Reimbursement per decedent for physicians' and other medical services was 3.9 times higher in the last year than reimbursement per survivor in 1978, and 1.9 times higher in the second-to-last year than for survivors in 1977.

Table 6. Reimbursement per enrollee and percent distribution of total reimbursements by decedents in their last and second-to-last years of life, and survivors in 1977 and 1978, by type of service.

| Year and type of service | Survival status | Ratio of reimbursement per enrollee of decedents to survivors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Decedents | Survivors | ||||

|

|

|

||||

| Amount | Percent distribution | Amount | Percent distribution | ||

| Last year (1978) | |||||

| All services | $4,527 | 100 | $729 | 100 | 6.2 |

| Hospital | 3,484 | 77 | 478 | 66 | 7.3 |

| Physician and other medical | 769 | 17 | 198 | 27 | 3.9 |

| Skilled nursing facility | 89 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 12.7 |

| Hospital outpatient | 101 | 2 | 30 | 4 | 3.4 |

| Home health agency | 83 | 2 | 16 | 2 | 5.2 |

| Second-to-last year (1977) | |||||

| All services | $1,481 | 100 | $635 | 100 | 2.3 |

| Hospital | 1,008 | 68 | 416 | 65 | 2.4 |

| Physician and other medical | 338 | 23 | 176 | 28 | 1.9 |

| Skilled nursing facility | 33 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 4.1 |

| Hospital outpatient | 59 | 4 | 24 | 4 | 2.5 |

| Home health agency | 43 | 3 | 12 | 2 | 3.6 |

NOTES: Data for the last year of life for decedents in 1978 are compared with the 1978 experience of survivors. Data for the second-to-last year of life are compared to the 1977 experience of survivors. Data are expressed in 1978 dollars.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration: Data from the Medicare Statistical System.

The largest relative difference in Medicare reimbursement per enrollee between decedents and survivors was found for skilled nursing facility (SNF) care, for which decedents had 12.7 times more reimbursement per enrollee in the last year of life than survivors had in 1978, and 4.1 times more in the second-to-last year of life than survivors had in 1977. Despite the large relative difference, the absolute level of use of Medicare SNF benefits by decedents was low when compared with hospital or physicians' services. Reimbursement per decedent for SNF care in the last year of life was only 2 percent of total reimbursements.

The low reimbursements for Medicare SNF care do not necessarily mean that nursing home use, of which SNF care is a part, is low in the last year of life. Rather, these low reimbursements reflect the fact that the Medicare SNF benefit is designed to provide short-term, post-hospital skilled nursing or rehabilitative services, not long-term nursing home care. For this reason, the law sets a number of conditions for coverage, such as need for skilled care and a limit of 100 days in each benefit period. Because of the nature of the benefit, Medicare SNF expenditures for all beneficiaries are 1 percent of all Medicare expenditures. In contrast, studies not confined to covered Medicare services suggest that nursing home care may be used extensively by aged persons in their last years (Wunderlich and Sutton, 1966; Zappolo, 1981). These studies show that among the aged, nursing home use by persons in their last year increases with age, as does the percent of deaths occurring in nursing homes. The low reimbursement level for home health agency services in the last year of life (2 percent of the total) also might reflect statutory Medicare program requirements, such as the restriction that the enrollee must require skilled nursing care or physical or speech therapy.

Use of hospital care

Decedents in both the last and second-to-last years of life greatly exceeded survivors on all measures of hospital use (Table 7). For example, the discharge rate for decedents in their last year was 1,537 per 1,000 enrollees, a figure 5.2 times the rate for survivors of 294 discharges per 1,000 enrollees in 1978. In the second-to-last year decedents had a discharge rate 2.1 times that of survivors in 1977 (556 versus 267 discharges per 1,000). The differences in the days-of-care rate were even larger. Decedents had 6.8 times as many days of care per 1,000 enrollees in their last year as did survivors in 1978 (20,607 versus 3,033), and they had 2.5 as many days of care in their second-to-last year as did survivors in 1977 (6,605 versus 2,682).

Table 7. Hospital use rates by decedents in their last and second-to-last years of life, and survivors in 1977 and 1978.

| Measure and period | Survival status | Decedents-to-survivors ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Decedents | Survivors | ||

| Persons hospitalized | Per 1,000 enrollees | ||

| Last year (1978) | 739 | 202 | 3.7 |

| Second-to-last year (1977) | 336 | 189 | 1.8 |

| Discharges | |||

| Last year (1978) | 1,537 | 294 | 5.2 |

| Second-to-last year (1977) | 556 | 267 | 2.1 |

| Days of care | |||

| Last year (1978) | 20,607 | 3,033 | 6.8 |

| Second-to-last year (1977) | 6,605 | 2,682 | 2.5 |

NOTE: Data for the last year of life for decedents in 1978 are compared with the 1978 experience of survivors. Data for the second-to-last year of life are compared to the 1977 experience of survivors.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration: Data from the Medicare Statistical System.

The rates of discharges and days of care followed the same pattern by age as noted earlier for total Medicare reimbursements, decreasing for older age groups for decedents and increasing for survivors (Table 8). The discharge rate for decedents 67 to 74 years of age was 1,771 per 1,000 enrollees; the rate for decedents age 75 or over was 1,444 per 1,000 enrollees. The decline with age in the discharge rate among decedents was attributed primarily to a decline in the rate of discharges per person hospitalized from 2.3 for persons 67 to 74 years of age to 2.0 for those 75 years of age or over, because the number of persons hospitalized per 1,000 decedents declined very little with age. (The discharge rate is the product of the rate of persons hospitalized per 1,000 enrollees and the rate of discharges per person hospitalized.)

Table 8. Selected measures of short-stay hospital use by decedents in their last year, and survivors in 1978, by age.

| Survival status | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Measure and age | Decedents | Survivors |

| Persons hospitalized | Per 1,000 enrollees | |

| 67 years or over | 739 | 202 |

| 67-74 years | 769 | 179 |

| 75 years or over | 727 | 226 |

| Discharges | Per person hospitalized | |

| 67 years or over | 2.1 | 1.5 |

| 67-74 years | 2.3 | 1.4 |

| 75 years or over | 2.0 | 1.5 |

| Discharges | Per 1,000 enrollees | |

| 67 years or over | 1,537 | 294 |

| 67-74 years | 1,771 | 260 |

| 75 years or over | 1,444 | 330 |

| Days of care | ||

| 67 years or over | 20,607 | 3,033 |

| 67-74 years | 23,795 | 2,530 |

| 75 years or over | 19,342 | 3,566 |

| Average length of stay | In days | |

| 67 years or over | 13.4 | 10.3 |

| 67-74 years | 13.4 | 9.7 |

| 75 years or over | 13.4 | 10.8 |

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration: Data from the Medicare Statistical System.

The decline in the days-of-care rate for decedents from 23,795 days per 1,000 enrollees 67 to 74 years of age to 19,342 days per 1,000 enrollees 75 years of age or over was due in turn to the decline with age in the discharge rate, because average length of stay did not change with age. (The days-of-care rate is the product of the discharge rate and average length of stay.)

The percent of deaths of Medicare enrollees occurring in hospitals also declined with age while the percent occurring in nursing homes increased with age (Table 9). In 1976, 42 percent of Medicare enrollees died in hospitals. The percentage declined from 48 percent among persons 65 to 74 years of age to 33 percent among persons 85 or over. An additional 22 percent of persons 65 years of age or over died in nursing homes. The percentage increased from 9 percent for persons 65 to 74 years of age to 38 percent for persons 85 years of age or over. This increase parallels the increase with age in the proportion of the elderly population living in nursing homes. In 1977, only 1.5 percent of persons 65 to 74 years of age were nursing home residents, but 22 percent of persons 85 years of age or over were nursing home residents (Van Nostrand et al., 1979).

Table 9. Deaths in hospitals and in nursing homes as a percent of total deaths, persons 65 years of age or over. 1976.

| Age | Hospital deaths as a percent of total deaths | Nursing home deaths as a percent of total deaths |

|---|---|---|

| 65 years or over | 42 | 22 |

| 65-74 years | 48 | 9 |

| 75-84 years | 43 | 23 |

| 85 years or over | 33 | 38 |

NOTE: Data on hospital deaths are for Medicare enrollees; data on nursing home deaths are for the entire population.

SOURCE: Data on hospital deaths are from the Medicare Statistical System. Data on the percents of deaths in nursing homes were derived by dividing the number of deaths in nursing homes from Van Nostrand et al. by the total number of deaths from Vital Statistics of the United States, 1976, published by the National Center for Health Statistics.

The percentage of deaths occurring in hospitals has remained fairly constant since Medicare began. In 1967, 44 percent of Medicare enrollees died in hospitals; in 1973, 41 percent died in hospitals, and in 1980, 41 percent also died in hospitals.

One goal of hospice care is to offer terminal patients an alternative to the hospital or nursing home as a place to live and to die. Thus, it will be interesting to see if there has been a change in the percentage of the aged dying in hospitals and nursing homes since the passage of the Medicare hospice benefit.

The relative incidence of various hospital diagnoses differs between decedents and survivors (Table 10). Diseases of the circulatory system were the leading causes of hospitalization for both decedents and survivors, making up 34 percent of discharges for decedents and 25 percent for survivors. Malignant neoplasms (cancer) made up 18 percent of discharges for persons in their last year of life but only 6 percent of discharges for survivors. On the other hand, discharges for diseases of the nervous system and sense organs, of the digestive system, of the genitourinary system, of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue, and for accidents, poisonings, and violence were relatively more common among survivors. These diagnostic categories include diseases such as cataract, inguinal hernia, and gall bladder disease, which have lower mortality than cancer or heart disease.

Table 10. Number and percent distribution of short-stay hospital discharges by decedents in their last year of life, and survivors in 1978, by selected principal diagnosis.

| Principal diagnosis and ICDA-8 codes | Decedents | Survivors | Discharges for decedents as a percent of total discharges | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Number of discharges in thousands | Percent distribution | Number of discharges in thousands | Percent distribution | ||

| Total | 1,755 | 100 | 5,391 | 100 | 25 |

| Malignant neoplasms (140-209) | 318 | 18 | 335 | 6 | 49 |

| Digestive organs and peritoneum (150-159) | 70 | 4 | 63 | 1 | 53 |

| Respiratory system (160-163) | 56 | 3 | 29 | 1 | 66 |

| Diseases of the nervous system and sense organs (320-389) | 32 | 2 | 349 | 6 | 8 |

| Diseases of circulatory system (390-458) | 604 | 34 | 1,362 | 25 | 31 |

| Diseases of heart (390-398, 402, 404, 410-429) | 387 | 22 | 833 | 15 | 32 |

| Ischemic heart disease (410-414) | 231 | 13 | 535 | 10 | 30 |

| Acute myocardial infarction (410) | 71 | 4 | 103 | 2 | 41 |

| Chronic ischemic heart disease (412) | 148 | 8 | 363 | 7 | 29 |

| Other forms of heart disease (420-429) | 144 | 8 | 261 | 5 | 36 |

| Congestive heart failure (427.0) | 82 | 5 | 117 | 2 | 41 |

| Cerebrovascular disease (430-438) | 142 | 8 | 282 | 5 | 34 |

| Diseases of respiratory system (460-519) | 180 | 10 | 482 | 9 | 27 |

| Pneumonia (480-486) | 74 | 4 | 149 | 3 | 33 |

| Diseases of digestive system (520-577) | 112 | 6 | 625 | 12 | 15 |

| Diseases of genitourinary system (580-629) | 72 | 4 | 378 | 7 | 16 |

| Diseases of musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (710-738) | 24 | 1 | 227 | 4 | 10 |

| Accidents, poisonings, and violence (800-999) | 84 | 5 | 433 | 8 | 16 |

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration: Data from the Medicare Statistical System.

Discharges for decedents account for 25 percent of all discharges but for a much larger proportion of some diagnostic categories, reflecting the high mortality for some diseases. Nearly one-half (49 percent) of cancer discharges were for decedents, and for cancers of the respiratory system the percent was even higher—66 percent. Discharges for decedents accounted for 31 percent of all discharges for diseases of the circulatory system. Within the circulatory disease category, discharges for decedents made up 41 percent of discharges for acute myocardial infarction, 29 percent of discharges for chronic ischemic heart disease, 41 percent of discharges for congestive heart failure, and 34 percent of discharges for cerebrovascular disease (stroke).

Of the three major disease categories of heart disease, cerebrovascular disease (stroke), and cancer, decedents hospitalized for cancer had the highest hospital use and highest total Medicare reimbursements.3 In 1978, cancer patients used an average of 36 days and had reimbursements of $8,297 in their last year of life. Decedents hospitalized for diseases of the heart used an average of 28 hospital days and had $5,878 in Medicare reimbursements. Decedents hospitalized for cerebrovascular disease also used an average of 28 hospital days and had $5,608 in Medicare reimbursements.

Trends in the use of services by decedents

This article shows that a large proportion of Medicare funds are spent for persons in their last year. In view of concern about the continual increase in Medicare costs, the question is often raised whether decedents account for an increasing share of Medicare expenses. Data from two studies (Piro and Lutins, 1973; Helbing, 1983) for 1967 and 1979 can be used to answer that question because they both examined calendar year expenses for decedents (rather than tracing expenses back 12 months from death as this article does.) Data from the studies indicate that the ratio of reimbursement per enrollee for decedents compared to survivors changed little from 1967 to 1979 (Table 11). For all Medicare services, the ratio was 4.9 in 1967 and 5.1 in 1979. For Part A of Medicare (Hospital Insurance) the ratio increased slightly from 5.8 to 6.0, and for Part B (Supplementary Medical Insurance) the ratio decreased slightly from 3.0 to 2.8.

Table 11. Reimbursement per enrollee, by type of service and survival status: 1967 and 1979.

| Year and type of service | Survival status | Decedents-to-survivors ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Decedents | Survivors | ||

| All services | |||

| 1967 | $823 | $169 | 4.9 |

| 1979 | $3,904 | $770 | 5.1 |

| Part A | |||

| 1967 | $658 | $114 | 5.8 |

| 1979 | $3,201 | $530 | 6.0 |

| Part B | |||

| 1967 | $165 | $55 | 3.0 |

| 1979 | $761 | $268 | 2.8 |

NOTE: Unlike the other data in this article, the data in this table for decedents are based on reimbursements in a calendar year rather than on a full 12 months before death.

SOURCE: Data for 1967 are from Piro and Lutins, 1973. Data for 1979 are from Helbing, 1983.

Conclusion

This study found that the rate of use of Medicare benefits by decedents greatly exceeds that of survivors. Fully 28 percent of Medicare reimbursements were for enrollees in their last year of life. The differences were greater than those found in some other studies of Medicare use by decedents (Piro and Lutins, 1973; Helbing, 1983) because the experience of decedents was traced back 12 full months rather than being limited to only calendar year data. The amount of Medicare expenditures for persons in the last year of life demonstrates the reality that Medicare, by its nature, is a program involved in insuring for the acute care needs of the aged, including their needs before death. As mentioned earlier, the vast majority of Medicare enrollees join at age 65 and remain covered until death. While this article does not analyze options in the way care is provided to the dying, it shows the services used and amounts of money expended. Clearly, it is difficult to know the appropriate amount of resources that society should expend for persons in their last year. Any analysis of this question would have to consider not only the amount and type of services devoted to the dying but also the persons with large expenses who might have died but for the care they received.

In spite of popular concern about the costs of heroic, life-sustaining treatments for the terminally ill, there is no evidence that expenditures for the dying have made a disproportionate contribution to the increase in Medicare expenditures. The available evidence indicates that large expenses for the dying are not a recent development. The relationship of per capita expenses for decedents to survivors has changed little from the start of Medicare to 1979. Nor has the percent of enrollees dying in hospitals changed since the beginning of Medicare. Additionally, only a small proportion of decedents had extremely high Medicare reimbursements. One percent of decedents had $30,000 or more in reimbursements, and these persons accounted for only 4 percent of expenses for decedents. Thus, it appears that the factors causing the increase in Medicare expenditures, such as price inflation and the introduction and use of advanced and expensive procedures have affected expenditures for decedents and survivors equally.4

Because they have high expenses, decedents also have high liability for Medicare deductibles and coinsurance. In 1978, 34 percent of decedents, but only 6 percent of survivors had more than $500 in cost-sharing liability. Proposed changes in the structure of Medicare to limit cost-sharing liability and to reduce the need to purchase “Medigap” policies would seem, therefore, to be particularly worthwhile. Such changes would relieve many dying persons and their families of at least one financial worry during a very stressful time.

The effect of mortality on age-specific patterns of Medicare expenses is large. When reimbursements are adjusted for mortality, the increase in per capita reimbursements with advancing age is greatly reduced. Thus, projections of health expenditures into the future must consider both the changing age structure of the population and changing mortality rates. If mortality rates for the 65 or over age group continue to fall, this may offset to some degree the increase in health care expenditures resulting from an increased proportion of the aged in our population.5

The large hospital care expenses for decedents reflect the large quantity of hospital care the dying receive. In some cases, the appropriateness of using hospitals to render care to the dying has been questioned. These data cannot be used to evaluate whether appropriate care was received. However, the data do show that the vast majority of decedents are hospitalized, suggesting the role hospitals have in the social as well as medical aspects of death and bereavement.

The use of Medicare services, especially hospital care, decreases with age for decedents but increases for survivors. In addition, the percent of enrollee deaths occurring in acute care hospitals declines with age. Other studies of the use of services by the dying also found these patterns. Since use of nursing homes increases with age, nursing home care very likely substitutes, in part, for hospital care for the dying as they advance in age. Medicare pays for only a small part of nursing home care. Thus, while Medicare expenses in the last year decrease with age, the relation of age to total health expenses may be different. Another possible explanation for the decline in Medicare reimbursements with age among decedents may be that very old, frail persons are less able to benefit from large amounts of treatment. Also, the time between onset of illness and death may be shorter for older decedents, resulting in lower hospital use.

Medicare plays a vital role in paying for the health care of the majority of persons who die in the United States. The highly skewed distribution of Medicare payments and the large amount of payments on behalf of the dying also show that Medicare functions to spread the risk of health care expenses over the total aged population. Decedents account for a high proportion of enrollees with extreme or catastrophic illness expenses. Much concern exists about the necessity and appropriateness of health services, particularly for the small percent of persons whose high costs account for a large share of total costs. The significant amount of Medicare expenditures for enrollees in their last year of life, and even the last month, means that a large part of Medicare funds is spent for persons who are severely ill.

The high use of hospital care and the relatively low use of the Medicare skilled nursing facility and home health benefits in the last year of life suggest examining the possibility of cost-saving through substitution of carefully targeted skilled nursing and home health services for hospital care. Such targeting would require knowledge of the nature of illnesses in the last year of life and the most appropriate methods of providing care. Part of the answer to the question of effective care may be provided by demonstration projects, sponsored by the Health Care Financing Administration, to test the hospice concept, and by evaluation of the new Medicare hospice benefit. These studies will measure whether health care costs for the dying are reduced when hospice care is made available. If costs are reduced, it may be possible to adopt measures that make care for the dying less costly and more humane at the same time.

This study found that a high proportion (46 percent) of costs in the last year of life are spent in the last 60 days. Also, costs for hospitalized cancer patients are higher than for patients hospitalized for other major diagnostic categories. Thus, hospice care could potentially have an impact on a large amount of costs. This is because data from hospice programs show that the average hospice stay is about 67 days and that most hospice patients suffer from cancer (Duzor, 1983).

The amount and kind of resources used at the end of life raise complex ethical, economic, and medical issues which must be considered within the context of the health care system and its financing mechanism, and in the context of societal expectations. These issues clearly indicate the need to consider a variety of feasible alternatives that would provide appropriate and humane care to the dying.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Marian Gornick, Allen Dobson, and Herbert Silverman of HCFA, Professor Stephen H. Long of Syracuse University, and Lillian Guralnick for their many helpful suggestions. We would like to thank Elvira Fussell for her help in the preparation of this article. We also wish to acknowledge the contribution of the Office of Statistics and Data Management of HCFA which manages the Medicare Statistical System, and especially the contribution of Eugene Stickler, Acting Director, who suggested the creation of the Continuous Medicare History Sample. The authors appreciate the contributions of Ronald Hillman, Malcolm Sneen, and James Welsh who maintain that file. Janet O'Leary and Lynne Rabey provided excellent computer programming support.

Special thanks is given to James Beebe, mathematical statistician, Office of Research and Demonstrations, for his patient assistance with the statistical and methodological aspects of this study.

Footnotes

Reprint requests: James Lubitz, Health Care Financing Administration, 2-C-11 Oak Meadows Building, 6325 Security Boulevard, Baltimore, MD 21207

“Users” or “persons served” are enrollees who receive some Medicare reimbursement.

The idea for this analysis comes from Fuchs, to be published.

Decedents were counted in a particular disease category if they had at least one hospital stay in that category in their last year. A person with two or more hospital stays, each in a different category, would be counted more than once.

The idea for this conclusion comes from Scitovsky, 1983.

This idea was first developed in Fuchs, to be published.

References

- Advisory Council on Social Security. Staff Summary of Recommendations of Meeting on Nov 3 and 4, 1983. Processed Nov. 8, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum H. The Cost of Catastrophic Illness. Toronto: Lexington Books; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom B, Kissick P. Home and hospital cost of terminal illness. Med Care. 1980 May;18(5):560–564. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198005000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen D, Ferrara L, Briggs B, et al. Survival, hospitalization charges, and followup results in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 1976;294(18):982–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197604292941805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duzor, L.: Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration Personal communication. Baltimore, 1983.

- Fisher CR. Health Care Financing Review. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Spring. 1980. Differences by age groups in health care spending. HCFA Pub. No. 03045. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher J.Ethics and the costs of dying inMilunsky A, Annas G.Genetics and the Law II New York: Plenum Publishing Corp.1980 [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs V. Though much is taken—Reflections on aging, health, and medical care. Millbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. To be published. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs J, Newman J. Study of Health Services Used and Costs Incurred During the Last Six Months of a Terminal Illness. Chicago, Ill: Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association; Nov, 1982. Contract No. HEW-100-79-0110. [Google Scholar]

- Gornick M, Beebe J, Prihoda R. Health Care Financing Review. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Sep, 1983. Options for change under Medicare: Impact of a cap on catastrophic illness expense. HCFA Pub. No. 03154. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helbing C. Health Care Financing Notes. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Nov, 1983. Medicare: Use and reimbursement for aged persons by survival status, 1979. HCFA Pub. No. 03166. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Reliability of Medicare Hospital Discharge Records. Washington, D.C.: Nov, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Krant M. The hospice movement. N Engl J Med. 1978;299(10):546–549. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197809072991012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall N. Utilization and costs of Medicare services by beneficiaries in their last year of life. Med Care. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198404000-00004. To be published. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mount B. The problem of caring for the dying in a general hospital, the palliative care unit as a possible solution. Can Med Assoc J. 1976 Jul;115(2):119–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piro PA, Lutins T. Health Insurance Statistics. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Oct. 1973. Utilization and reimbursement under Medicare for persons who died in 1967 and 1968. HI 51. DHEW Pub. No. (SSA) 74-11702. Office of Research and Statistics, Social Security Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder C, Ross D. Terminal care issues and alternatives. Public Health Rep. 1977 Jan-Feb;92(1):20–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder S, Showstack J, Roberts H. Frequency and clinical description of high-cost patients in 17 acute-care hospitals. N Engl J Med. 1979 Jun 7;300(23):1306–1309. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197906073002304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder S, Showstack J, Schwartz J. Survival of adult high-cost patients, Report of a followup study from nine acute-care hospitals. JAMA. 1981 Apr.245(14):1446–1449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scitovsky A. The High Cost of Dying—Some Economic Aspects. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association; Dallas, Tex.. Nov. 15, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Scotto J, Chiazze L., Jr . Third National Cancer Survey, Hospitalizations and Payments to Hospitals, Part A, Summary. National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Md.: Mar. 1976. DHEW Pub. No. (NIH) 76-1094. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton GF. Vital and Health Statistics. No. 1. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Sept. 1965. Hospitalization in the last year of life, United States, 1961. (22). PHS Pub. No. 1000. Public Health Service. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmer EJ, Kovar MG. Vital and Health Statistics. No. 11. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Mar. 1971. Expenses for hospital and institutional care during the last year of life for adults who died in 1964 or 1965, United States. (22). PHS Pub. No. 1000. National Center for Health Statistics, Public Health Service. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Nostrand JF, Zappolo A, Hing E, et al. Vital and Health Statistics. No. 43. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Jul, 1979. The National Nursing Home Survey, 1977 summary for the United States. (13). DHEW Pub. No. (PHS) 79-1794. National Center for Health Statistics, Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich GS, Sutton GF. Vital and Health Statistics. No. 2. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Jun, 1966. Episodes and duration of hospitalization in the last year of life, United States, 1961. (22). PHS Pub. No. 1000. Public Health Service. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zappolo A. Vital and Health Statistics. No. 54. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Aug. 1981. Discharges from nursing homes: 1977 National Nursing Home Survey. (13). DHHS Pub. No. (PHS) 81-1715. National Center for Health Statistics, Public Health Service. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zook C, Moore F. High cost users of medical care. N Engl J Med. 1980 May;302(18):996–1002. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198005013021804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zook C, Moore F, Zeckhauser R. Catastrophic health insurance—A misguided prescription? The Public Interest. 1981 Winter;62:66–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]