Abstract

The ‘hitchhiker’ mechanism of the bacterial twin-arginine translocation pathway has previously been adapted as a genetic selection for detecting pairwise protein interactions in the cytoplasm of living Escherichia coli cells. Here, we extended this method, called FLI-TRAP, for rapid isolation of intracellular antibodies (intrabodies) in the single-chain Fv format that possess superior traits simply by demanding bacterial growth on high concentrations of antibiotic. Following just a single round of survival-based enrichment using FLI-TRAP, variants of an intrabody against the dimerization domain of the yeast Gcn4p transcription factor were isolated having significantly greater intracellular stability that translated to yield enhancements of >10-fold. Likewise, an intrabody specific for the non-amyloid component region of α-synuclein was isolated that has ∼8-fold improved antigen-binding affinity. Collectively, our results illustrate the potential of the FLI-TRAP method for intracellular stabilization and affinity maturation of intrabodies, all without the need for purification or immobilization of the antigen.

Keywords: antigen-binding affinity, directed evolution, intracellular antibody engineering, protein folding and stability, twin-arginine translocation

Introduction

In all organisms, surveillance of the various steps in protein biosynthesis is carried out by diverse quality control (QC) mechanisms that preserve proteome integrity (proteostasis) by ensuring proper folding, assembly and localization of cellular proteins, and, when necessary, eliminating any aberrant products (Balch et al., 2008). Even in simple organisms, such as Escherichia coli, a sophisticated protein QC system orchestrates protein synthesis, folding, degradation, and trafficking (Hartl and Hayer-Hartl, 2009). As the details of these mechanisms emerge, protein engineers have demonstrated a keen ability to harness QC networks for the isolation of foldable sequences from random libraries (Hagihara and Kim, 2002; Hagihara et al., 2005) and the creation of designer proteins with improved traits, such as faster folding (Ribnicky et al., 2007; Fisher and DeLisa, 2008), increased stability (Shusta et al., 1999, 2000; Fisher and DeLisa, 2009; Pavoor et al., 2009) and resistance to aggregation/degradation/unfolding (Fisher et al., 2006).

The QC checkpoints associated with protein translocation have proven particularly useful for engineering the fitness and function of target proteins. For example, the QC system of the yeast secretory pathway permits the secretion of native or correctly folded proteins while preventing the release of misfolded or incompletely folded proteins. As a result, secretion efficiency of a given protein often correlates with its structural status (Hong et al., 1996; Kowalski et al., 1998a,b). In bacteria, the twin-arginine translocation (Tat) pathway has the unique ability to transport structurally diverse proteins that have already folded in the cytoplasm prior to membrane translocation (Lee et al., 2006; Palmer and Berks, 2012). In fact, only folded proteins are exported by the Tat translocase whereas mis/unfolded substrate proteins are rejected (Rodrigue et al., 1999; Sanders et al., 2001; Bruser et al., 2003; DeLisa et al., 2003; Fisher et al., 2006; Rocco et al., 2012) with only a few rare exceptions reported in plant thylakoids (Hynds et al., 1998; Cline and McCaffery, 2007) or in bacteria where the levels of the TatABC proteins are artificially increased by 50-fold (Richter et al., 2007). Suppressor mutations in the TatABC translocase components were recently isolated that inactivate QC and permit export of misfolded proteins, suggesting that the Tat translocase directly participates in structural proofreading of its substrate proteins (Rocco et al., 2012). At present, however, the details of how the Tat QC system discriminates the folding status of substrate proteins remain unclear. Nonetheless, the opportunistic use of this mechanism to engineer proteins in living cells has been repeatedly demonstrated. For instance, the Tat QC mechanism can be used to rapidly quantify protein folding and solubility for a wide array of prokaryotic and eukaryotic test proteins (Fisher et al., 2006; Gushchina et al., 2009). Tat QC has also been used to isolate mutations or small molecules that reduce protein aggregation (Fisher et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2009; Waraho-Zhmayev et al., 2013) and to select for more stable variants of virtually any protein-of-interest, including intracellular antibodies (intrabodies) and proteins associated with aggregation diseases (e.g. α-synuclein, amyloid-β protein) (Fisher and DeLisa, 2009; Fisher et al., 2011; Karlsson et al., 2012; Waraho-Zhmayev et al., 2013).

By simultaneously leveraging Tat QC with the known ‘hitchhiker’ mechanism (Rodrigue et al., 1999), it is possible to select for protein–protein interactions (Waraho and DeLisa, 2009, 2012, Waraho-Zhmayev et al., 2013). This strategy, termed FLI-TRAP (functional ligand-binding identification by Tat-based recognition of associating proteins), is based on the unique ability of the Tat translocase to efficiently co-localize non-covalent complexes of two correctly folded polypeptides to the periplasmic space of E. coli (Rodrigue et al., 1999). The design principle for this genetic assay involves two engineered fusion proteins: an N-terminal Tat signal peptide fused to a receptor protein, and the corresponding ligand fused to TEM-1 β-lactamase (Bla). Co-localization of the ligand-Bla fusion by the Tat-targeted receptor enables semiquantitative, high-throughput selection of interacting pairs that are stably expressed, and interact with high affinity in the bacterial cytoplasm. Thus, antibiotic resistance can be used as a phenotypic readout for identifying and optimizing receptor-ligand interactions in living E. coli cells.

Because the FLI-TRAP assay involves pairwise interactions between cytoplasmically expressed proteins, this method has proven especially useful for the selection of single-chain Fv (scFv) antibodies that can fold and function in an intracellular compartment (Waraho and DeLisa, 2009, 2012; Waraho-Zhmayev et al., 2013). This is significant because the generation of intrabodies is normally quite challenging due to the fact that the reducing environment of the cytoplasmic compartment, where intrabodies are designed to function, disfavors the formation of disulfide bonds such as those connecting the two β-sheets in each of an scFv intrabody′s VH and VL domains. The absence of these bonds causes a large decrease in the ΔG of folding (∼4–5 kcal/mol) (Frisch et al., 1996) and a concomitant loss of antigen-binding activity, susceptibility to proteolysis, and aggregation (Proba et al., 1997; Cattaneo and Biocca, 1999). This challenge can be overcome by using the FLI-TRAP method to isolate scFv antibodies that can tolerate the loss of disulfide bridge formation and, as a result, are functional in the intracellular environment. Here, we present a powerful adaptation of FLI-TRAP for optimizing the intracellular stability and antigen-binding affinity of intrabodies simply by selecting resistant bacterial clones on high concentrations of antibiotic.

Materials and methods

Strains and growth conditions

Wild-type (wt) E. coli strain MC4100 was used for all growth selection experiments. Selective plating of bacteria was performed as described (Fisher et al., 2006, 2011). Briefly, MC4100 cells were co-transformed with plasmids pDD322-TatABC for increasing the copy number of TatABC translocases (Waraho and DeLisa, 2009) and pDD18-ssTorA-scFv-GCN4-FLAG::GCN4(7P14P)-Bla (Waraho and DeLisa, 2009) that co-expresses the ssTorA-scFv fusion along with GCN4(7P14P)-Bla. For the α-syn experiments, MC4100 cells were co-transformed with pDD322-TatABC :: α-syn(A53T)-Bla and pDD18-ssTorA-NAC32-FLAG. Transformed bacteria were grown overnight at 37°C in Luria Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with 25 μg/ml chloramphenicol (Cm) and 10 μg/ml tetracycline (Tet). The next day, drug resistance of bacteria was evaluated by spot plating 5 µl of serially diluted overnight cells that had been normalized in fresh LB to OD600 = 2.5 onto LB agar plates supplemented with 1.0% arabinose and 25 μg/ml Cm as a control or varying amounts of carbenicillin (Carb; 100–1000 μg/ml). Plated bacteria were incubated at 30°C for ∼48 h. Strain BL21(DE3) was used for cytoplasmic expression of proteins from pET-28a plasmids. Cultures were grown in LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin (Kan), and protein expression was induced with isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (0.1 mM).

Plasmid construction

For the α-syn (A53T) intrabody–antigen system, the intrabody and antigen were subcloned into an updated version of FLI-TRAP system in which the intrabody and antigen were cloned in two different vectors. Specifically, the GCN4(7P14P)-Bla construct together with a ribosome-binding site was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from the original pDD18-ssTorA-scFv-GCN4-FLAG :: GCN4(7P14P)-Bla and cloned after the tatC gene in pDD322-TatABC (Waraho and DeLisa, 2009), resulting in pDD322-TatABC :: GCN4(7P14P)-Bla. Next, the DNA-encoding GCN4(7P14P) and its original linker were excised and replaced with PCR-amplified DNA-encoding α-syn(A53T) with a C-terminal (Gly4Ser)3 introduced via primer extension, resulting in plasmid pDD322-TatABC :: α-syn(A53T)-Bla. For the NAC32 intrabody, the DNA encoding GCN4(7P14P)-Bla was first removed from pDD18-ssTorA-scFv-GCN4-FLAG::GCN4(7P14P)-Bla and the plasmid was re-ligated to create pDD18-ssTorA-scFv-GCN4-FLAG. Next, the gene encoding the scFv-GCN4 intrabody was excised and replaced with PCR-amplified DNA-encoding NAC32 (GenScript, GenBank EU079027.1), resulting in plasmid pDD18-ssTorA-NAC32-FLAG. For cytoplasmic expression of scFv-GCN4 and its variants (m1, m2 and m3) without the ssTorA signal peptide, the pET28a-scFv-GCN4 plasmid was constructed by PCR amplification of intrabody genes including the C-terminal FLAG tag from the respective pDD18-Cm-ssTorA-scFv-GCN4-FLAG :: GCN4(7P14P)Bla vectors. The resulting PCR products were ligated into pET-28a, introducing a C-terminal 6x-His tag. A similar cloning strategy was used to make pET-28a plasmids encoding NAC32 and its variants (NAC32.R1 and NAC32.R2) lacking the ssTorA signal peptide. However, due to degradation at the C-terminus of NAC32, the FLAG tag was introduced at the N-terminus of the intrabody during PCR amplification. The resulting PCR products were ligated into pET28a, introducing an N-terminal 6x-His tag in the process. The pET28a-MBP-TEV-GCN4 was constructed by overlap extension PCR amplification of the genes encoding E. coli maltose-binding protein (MBP) and GCN4 using primers that introduced a TEV protease cleavage site between the genes. The final PCR product was cloned into pET28a, introducing a 6x-His tag at the N-terminus of the construct.

Subcellular fractionation and Western blot analysis

To prepare subcellular fractions for western blot analysis, 20–25 ml of induced culture was pelleted. Cells were resuspended in 1 ml subcellular fractionation buffer (30 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.6 M sucrose) and then incubated for 8 min at room temperature. After adding 220 μl of 5 mM MgSO4 (resulting in a normalized final OD600 = 75), cells were incubated for 8 min on ice. Cells were spun down, and the supernatant was taken as the periplasmic fraction. The pellet was resuspended in 220 μl phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and sonicated on ice. Following centrifugation at 16 000 rcf for 20 min at 4°C, the second supernatant was taken as the cytoplasmic soluble fraction, and the pellet was the insoluble fraction. To prepare samples for analysis of cytoplasmic solubility, 3–5 ml of induced culture was pelleted and resuspended in 500 μl PBS (final OD600 = 20). Samples were sonicated on ice and then spun down at 16 000 rcf for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was taken as the soluble cytoplasmic fraction. For pET28a constructs, samples were prepared as soluble whole cell lysate and insoluble fractions. For preparation of whole cell lysate, 20–25 ml of induced cell culture was pelleted and resuspended in 500 μl PBS to achieve normalized final OD600 ≈ 75. The sample was sonicated on ice and then spun down at 16 000 rcf for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was taken as the soluble whole cell lysate fraction. The pellet was washed twice with 1 ml Tris–HCl (50 mM) with EDTA (1 mM) and resuspended in 500 μl PBS with 2% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS). After boiling for 10 min, the resuspended pellets were centrifuged for 10 min at 16 000 rcf. The supernatant was taken as the insoluble fraction. Proteins were separated by Precise Tris-HEPES 4–20% SDS polyacrylamide gels (Thermo Scientific), and western blotting was performed according to standard protocols. Briefly, proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, and membranes were probed with the following antibodies: mouse anti-FLAG M2-HRP (Sigma-Aldrich) to detect intrabodies, mouse anti-Bla (Abcam) to detect the GCN4(7P14P)-Bla fusion, and rabbit anti-GroEL (Abcam) to detect housekeeping proteins in E. coli cells.

Library construction and selection

A random mutagenesis library was generated from scFv-GCN4(GLF) using the Genemorph II random mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). PCRs were performed with 1 ng pDD18-ssTorA-scFv-GCN4(GLF)-FLAG::GCN4(7P14P)-Bla (containing scFv-GCN4(GLF) template) in each reaction. The resulting PCR products were digested, purified by gel electrophoresis and cloned into pDD18-ssTorA-scFv-GCN4(GFA)-FLAG::GCN4(7P14P)-Bla that had been digested with the same enzymes. The library was transformed into electrocompetent DH5α cells and selected on LB agar containing Cm to recover clones containing the plasmid. The library size and error rate were determined to be 1.6 × 106 members and ∼3 mutations per gene, respectively. The plasmid library was miniprepped from DH5α and used to transform electrocompetent MC4100 cells already harboring the pDD322-TatABC plasmid. Transformed cells were incubated at 37°C for 1 h without any antibiotics then were subcultured overnight into fresh LB containing 25 µg/ml Cm and 10 µg/ml Tet to ensure that cells contained both plasmids. After ∼16 h, cells were spun down and normalized in fresh LB to OD600 = 2.5 followed by direct plating of 100 µl of diluted cells (to the dilution previously determined by spot plating) onto LB agar supplemented with 1% arabinose and 500–600 μg/ml Carb. Hits were randomly picked after incubation at 30°C for ∼48 h. An identical selection of cells carrying the pDD18-ssTorA-scFv-GCN4(GLF)-FLAG::GCN4(7P14P)-Bla plasmid was performed as negative control. Randomly chosen positive clones were screened by spot plating to confirm Carb resistance and then sequenced. The same protocols were performed for error-prone NAC32 library construction and selection. The library size and error rate were determined to be 2.0 × 106 members and ∼3 mutations per gene, respectively. Library selection was performed by plating diluted cells onto LB agar supplemented with 1% arabinose and 50–100 μg/ml Carb at 30°C for ∼48 h. In this case, wt NAC32 was used as the negative control.

Protein purification

For intrabody purification, bacterial cell pellets, harvested by centrifugation, were resuspended in binding buffer: 20 mM sodium phosphate, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, pH 7.4. The cell suspensions were then passed five times through an EmulsiFlex™-C5 cell homogenizer (Avestin; 15 000 psi/4°C) and centrifuged at 48 300 g for 20 min at 4°C. The clarified lysate was filtered through a 0.2-μm-syringe filter prior to sample loading. The sample was initially loaded through a 1-ml HisTrap™ HP column (GE Healthcare). The captured protein was eluted with buffer containing 20 mM sodium phosphate, 500 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, pH 7.4. The pooled eluent was injected onto a HiPrep 26/10 desalting column (GE Healthcare) to exchange the protein into 20 mM Tris–HCl, and then concentrated using a 3-kDa molecular weight cut off ultrafiltration spin column (Vivaspin; Sartorius Stedim). Final purity of proteins was confirmed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and Coomassie staining. Purity of all proteins was typically >95%. Representative intrabody yields were determined by total protein assay and are provided in Table I. For enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) experiments, the full-length MBP-TEV-GCN4 construct was first purified using Ni-NTA His Bind® Resin (Novagen). The soluble lysate containing MBP-GCN4 was diluted with binding/washing buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 100 mM sodium chloride, and 10 mM imidazole (pH 7.4)) then loaded onto the equilibrated pre-charged column through which the lysate flowed through via gravity. The column was washed twice with washing buffer. Purified fusion protein was eluted using elution buffer containing 50 mM NaH2PO4, 100 mM sodium chloride, and 180 mM imidazole (pH 7.4). After purification, the elutions were pooled, buffer-exchanged with PBS, partially purified to remove low molecular weight impurity, and concentrated using 3-kDa molecular weight cut off column (Vivaspin ultrafiltration spin column, Sartorius Stedim). To remove the MBP domain, purified MBP-TEV-GCN4 was proteolytically cleaved using TEV protease in a reaction performed according to manufacturer′s protocol, except that the reaction was carried out overnight at room temperature in ProTEV buffer with 1 mM DTT. The cleaved GCN4 was recovered by subjecting the TEV reaction mix to 30-kDa MWCO column where the filtrate was collected as GCN4. Both concentrate and filtrate were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie staining to confirm only the presence of GCN4. For surface plasmon resonance (SPR) experiments, full-length MBP-GCN4 was purified using amylose resin (NEB). The soluble lysate was first diluted 5 times with column buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, 200 mM sodium chloride, 1 mM EDTA). The diluted crude extract was loaded onto the equilibrated amylose resin column and allowed to flow through by gravity. The column was washed with 14 column volumes of column buffer. Finally, the purified fusion protein was eluted with column buffer containing 10 mM maltose and analyzed for purity by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie staining.

Table I.

Characterization of scFv-GCN4 and isolated variants

| Clone | VL mutationsa |

Linker | VH mutationsa |

Yieldb (mg/l) | Kdc (nM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDR (#) | FR (#) | (G4S)3 | CDR (#) | FR (#) | |||

| scFv-GCN4(GLF) | – | – | – | – | – | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| m1 | – | S76N (3) | (G4S)2GSGGS | – | Q81E (3) | 1.7 | ND |

| m2 | Y92N (3) | R108H (4) | – | – | – | 1.3 | ND |

| m3 | – | F87Y (3) | – | I56T (2) | – | 8.5 | 0.6 |

aKabat numbering is used for VH and VL amino acids. Values in parentheses refer to CDR or framework number. See Supplementary Fig. S1A for complete sequences.

bYields of purified scFv intrabodies from a representative experiment determined by total protein assay.

cEquilibrium dissociation constants determined by SPR using Biacore 3000.

ND, not determined.

Antigen-binding activity

To evaluate the binding of purified anti-GCN4 intrabodies, ELISA plates were coated overnight at 4°C with 50 μl/well of purified GCN4 in ELISA coating buffer (0.05 M NaCO3 buffer, pH 9.6) (10 μg/ml). Plates were then blocked at room temperature for 2 h with 5% non-fat milk in tris-buffered saline (TBS). After washing plates using TBS supplemented with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST), purified protein samples serially diluted in TBS with 10 μg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) were added to the plates (50 μl/well). Plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature and then washed with TBST. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-6x-His antibody (Abcam) in TBS-BSA was added to the plates (50 μl/well). After 1 h of incubation at room temperature, plates were washed and then incubated with SigmaFast OPD HRP substrate (Sigma) for 30 min in the dark. The reaction was quenched with 3 M H2SO4, and the absorbance of the wells was measured at 492 nm. A similar protocol was performed for NAC32. Briefly, ELISA plates were coated with 50 μl/well of purified α-Syn(A53T) peptide (1 µg/ml; GenWay Biotech Inc.) overnight at 4°C. Whole cell lysates derived from BL21(DE3) cells expressing 6x-His-FLAG-NAC32 were applied as intrabody samples and anti-FLAG-HRP conjugated antibody in TBS-BSA was used to detect bound proteins. SPR experiments were carried out using a Biacore 3000 instrument with CM-5 sensor chips that had been activated with N-hydroxysuccinimide/N-ethyl-N′(dimethyl-aminopropyl) (NHS–EDC). For kinetic analysis of scFv-GCN4(GLF) and clone m3, 20 μg/ml purified MBP-GCN4 in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.0 was coupled to activated CM5 chips using NHS–EDC chemistry to a level of ∼1500 RU. Ethanolamine hydrochloride was used to block the remaining activated groups. The injection buffer and the reservoir buffer were the same throughout: 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 3mM EDTA, 0.005% polysorbate-20 (GE Healthcare). Serial dilutions of scFv-GCN4(GLF) or clone m3 were injected at 30 μl/min, 25°C starting at 32 nM unless otherwise noted. For kinetic analysis of NAC32 and NAC32.R2, 0.15 mg/ml of α-syn(A53 T) peptide in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.0 was coupled to CM5 chips using NHS–EDC chemistry to a level of ∼1500 RU. Serial dilutions of NAC32 (1.125–18 μM) and NAC32.R2 (23–375 nM) were injected at 30 μl/min, 25°C. The BIAevaluation software (GE Healthcare) was used for the calculation of ka, kd, and KD by curve fitting the data with a Langmuir 1 : 1 binding model.

Results

Intrabodies co-localize their antigens to the periplasm

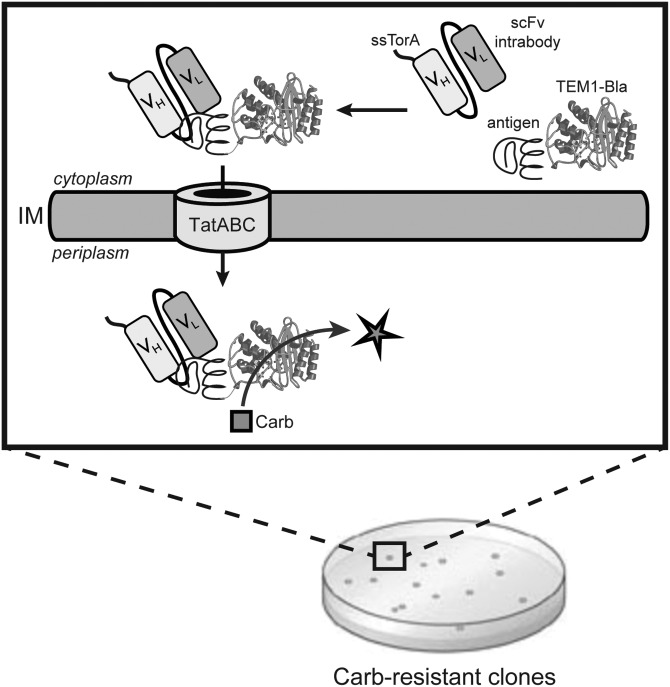

We sought to use FLI-TRAP for evolving intrabodies with superior properties. To this end, we focused our attention on scFv-GCN4 (Ω-graft variant) that binds the 47-residue bZIP domain of the yeast transcription factor Gcn4p. This scFv was previously developed for stable intracellular expression (der Maur et al., 2002) and is compatible with the FLI-TRAP assay (Waraho and DeLisa, 2009). To incorporate this receptor–ligand pair in the FLI-TRAP, assay involves two engineered fusion proteins: an N-terminal Tat signal peptide (ssTorA) fused to scFv-GCN4, and the corresponding Gcn4p bZIP domain fused to Bla (Fig. 1). We used a variant of the Gcn4p bZIP domain called GCN4(7P14P), which contains 2 helix-breaking proline mutations that disrupt the helical structure of the zipper and prevent its coiled-coil-mediated homodimerization (Berger et al., 1999). Thus, this mutant simplifies the selection process because antigen–antibody binding does not have to compete with the homodimerization process. The antibiotic resistance of strains expressing these fusion proteins was measured by spotting dilutions of cells onto plates containing increasing concentrations of the β-lactam antibiotic Carb. Fig. 2A shows one such experiment: using plates containing 500 μg/ml Carb, we compared the growth of cells expressing the ssTorA-scFv-GCN4 fusion containing wt scFv intrabody with the residues GLF in the complementarity-determining region 3 of the heavy chain (CDR-H3) to that of a low-affinity scFv-GCN4 variant with the residues GFA in CDR-H3 (der Maur et al., 2002). Consistent with our earlier studies, the low-affinity scFv-GCN4(GFA) conferred significantly lower resistance toward Carb over a wide range of antibiotic concentrations compared with the higher affinity scFv-GCN4(GLF) clone (Fig. 2A). Western blot analysis revealed that the significant growth advantage conferred by scFv-GCN4(GLF) was the result of its ability to co-localize the GCN4(7P14P)-Bla antigen to the periplasm (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 1.

Optimizing recombinant intrabodies using FLI-TRAP. Schematic representation of engineered assay for co-translocation of interacting receptor-ligand pairs via the Tat translocase. By simply demanding bacterial growth on high concentrations of antibiotic, the intracellular stability and/or antigen-binding affinity can be enhanced. The Tat signal peptide chosen was ssTorA, the reporter enzyme was Bla, the receptor was either scFv-GCN4(GLF) or NAC32, and the ligands were GCN4(7P14P) or α-syn(A53T).

Fig. 2.

Direct selection of improved scFv-GCN4 variants. (A) Representative spot titers for serially diluted Escherichia coli MC4100 cells co-expressing TatABC along with GCN4(7P14P)-Bla and one of the following: ssTorA-scFv-GCN4(GLF), the low-affinity ssTorA-scFv-GCN4(GFA) variant, or library-selected clones m1–m3 derived from scFv-GCN4(GLF). Overnight cultures were serially diluted in liquid LB and plated on LB agar supplemented with Carb. Maximal cell dilution that allowed growth is plotted versus Carb concentration. Arrow indicates Carb concentration depicted in the panel above the graph (500 μg/ml). (B) Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic (cyt) and periplasmic (per) fractions prepared from the same cells as in (A). An equivalent number of cells were loaded in each lane. Blots were probed with an anti-Bla antibody to detect GCN4(7P14P)-Bla and an anti-FLAG antibody to detect scFv-GCN4 intrabodies. Quality of fractions was confirmed by probing membranes with an anti-GroEL antibody.

Direct selection of improved scFv-GCN4 variants using FLI-TRAP

Based on the above results, we hypothesized that the efficiency with which a Tat-targeted receptor co-localizes a cognate ligand-Bla fusion to the periplasm is linked to both the in vivo stability of the receptor and its affinity for the ligand. If this interpretation is correct, then isolation of intrabody variants that have enhanced stability and/or that bind their target antigens with greater affinity should be possible by demanding growth on Carb concentrations that would otherwise inhibit the growth of cells expressing the parental intrabody clone. To test this idea, we generated an error-prone PCR library of scFv-GCN4(GLF) sequences and selected this library on 500–600 μg/ml Carb. This amount of Carb was chosen because it was found to inhibit the outgrowth of individual colonies expressing scFv-GCN4(GLF). Following one round of mutagenesis and selection, clones m1, m2 and m3 were isolated, all of which conferred greater drug resistance compared with the parental scFv-GCN4(GLF) clone (Fig. 2A). To confirm that the greater resistance conferred by these clones was due to mutations in scFv-GCN4(GLF) and not elsewhere in the plasmid, all isolated scFv sequences were back cloned into the original vector, containing unmutated copies of the antigen and Bla genes. Cells expressing these back-cloned constructs all exhibited the same resistance phenotype as the originally isolated mutants (data not shown). Importantly, this enhanced resistance correlated directly to a significant enhancement in GCN4(7P14P)-Bla co-localization to the periplasm and to a greater accumulation of each intrabody in the periplasm (Fig. 2B). The enhancements in resistance and protein localization to the periplasm were most dramatic in the case of clone m3. While the mutations in clone m1 were in the framework and linker regions, clones m2 and m3 carried mutations in CDR-L3 and CDR-H2, respectively, in addition to a framework mutation in the VL domain of each (Table I and Supplementary Fig. S1A).

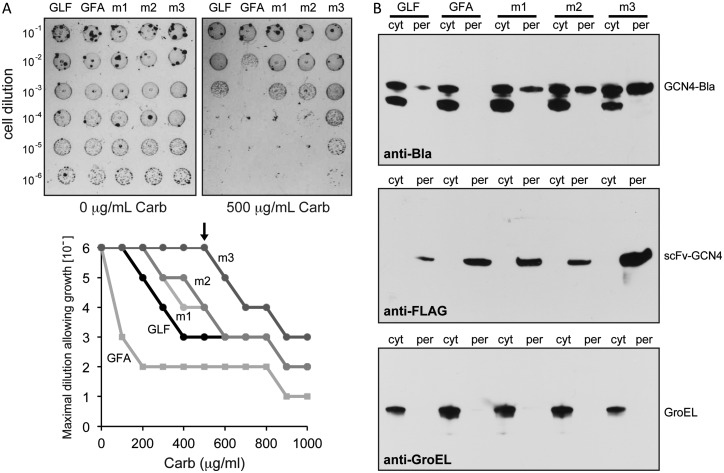

Intracellular stability of FLI-TRAP-selected variants

Given the greater accumulation of clones m1–m3 in the periplasm, we suspected that the in vivo stability of these clones was increased. To test this, we examined the soluble accumulation of the intrabodies following high-level expression without the N-terminal Tat signal peptide. Specifically, each intrabody was subcloned into plasmid pET-28a and expressed in BL21(DE3) cells. As expected, the soluble expression of clones m1-m3 was increased compared with scFv-GCN4(GLF) (Fig. 3A) in a manner that coincided directly with the Carb resistance conferred by each clone: m3 >> m2 ≈ m1 > scFv-GCN4(GLF) ≈ scFv-GCN4(GFA). We suspectthat the poorly folded/less stable scFv-GCN4(GLF) proteins were subject to rapid proteolysis, which likely explains their low levels in the soluble fraction without a concomitant increase in the insoluble fractions. The greater soluble accumulation of the isolated clones corresponded to yield enhancements of ∼2-fold for clones m1 and m2 and greater than 10-fold for clone m3, which reached nearly 10 mg per liter of cell culture (Table I). Given the frequency of mutations (three out of seven total) in the framework region of the VL domain (Table I and Supplementary Fig. S1A), we speculate that this chain was limiting the stability of scFv-GCN4(GLF) in the reducing cytoplasms of bacteria.

Fig. 3.

Intracellular accumulation and antigen binding of scFv-GCN4 variants. (A) Western blot analysis of soluble and insoluble fractions from BL21(DE3) cells expressing scFv intrabodies without signal peptides from pET-28a. Clone m1, m2 and m3 were isolated using a single round of mutagenesis and FLI-TRAP selection. scFv-GCN4(GLF) was the starting sequence for the library, and scFv-GCN4(GFA) was a low-affinity derivative of scFv-GCN4(GLF) used here as a control. Samples were normalized by total protein concentration in the soluble fraction, and blot was probed with an anti-FLAG antibody. (B) ELISA data for binding of isolated clones to GCN4. Intrabodies were purified from cell lysate, and their binding to GCN4-coated ELISA plates was measured. Bound scFv intrabodies were detected with an anti-FLAG antibody. ELISA data are normalized to the signal for clone m3 at ∼5 μg/ml and expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean of six biological replicates.

Antigen-binding activity of FLI-TRAP-selected variants

In addition to improved fitness in vivo, the increased resistance conferred by the selected clones could also be due to higher affinity for the bZIP domain of Gcn4p. To test this notion, we compared the binding activity of clones m1–m3 with that of scFv-GCN4(GLF) by indirect ELISA using purified GCN4 as antigen. In line with the drug resistance and intracellular stability results, clone m3 exhibited the highest binding activity, showing a nearly 3-fold increase over scFv-GCN4(GLF) (Fig. 3B). Clones m1 and m2 also showed improved binding activity, albeit to a lesser extent than clone m3. To quantitate binding affinity, the equilibrium dissociation constant, KD, for some of the intrabodies was measured using purified MBP-GCN4 as the immobilized antigen. The parental scFv-GCN4(GLF) and clone m3 had nearly identical Kd values in the low nanomolar range (0.5 and 0.6 nM, respectively; Table I and Supplementary Fig. S1B). Neither of these clones showed any measureable binding signal when MBP alone was immobilized as antigen (data not shown). Thus, we conclude that the dramatic intracellular stabilization of m3 was achieved without compromising its antigen-binding activity. Moreover, despite the similar apparent affinities, the on- and off-rates (ka and kd, respectively) for clone m3 were both nearly three times faster than those measured for scFv-GCN4(GLF) (Supplementary Fig. S1B), indicating that the FLI-TRAP-selected mutations in m3 have changed the way the intrabody associates with and dissociates from its antigen.

Engineering an intrabody specific for α-synuclein

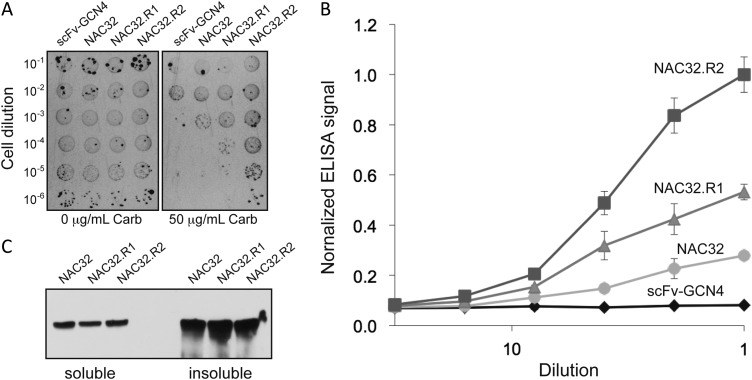

To determine whether the above approach could be generalized to other scFv intrabodies, we attempted to improve the properties of an scFv intrabody called NAC32 (Lynch et al., 2008), which recognizes the non-amyloid component (NAC) region of α-synuclein (α-syn) that shows strong tendencies to form β-sheet structures. We chose this target because intrabody-mediated prevention of abnormal misfolding and aggregation of α-syn in vulnerable neurons has been proposed as a viable therapeutic strategy for reducing pathogenesis in Parkinson′s disease. To configure this intrabody for FLI-TRAP, we generated two chimeras: the first was a fusion between the ssTorA signal peptide and NAC32 and the second was a fusion between Bla and α-syn(A53T), a highly toxic version of α-syn (Lynch et al., 2008). Co-expression of these chimeras in E. coli cells conferred a low level of antibiotic resistance, which was only slightly above the background resistance conferred by co-expression of the non-specific scFv-GCN4 intrabody (Fig. 4A). To identify mutations that improved either the intracellular stability or the antigen-binding affinity of NAC32, we screened an error-prone PCR library of wt NAC32 sequences for clones that conferred greater antibiotic resistance to cells. Following one round of mutagenesis and selection, clone NAC32.R1 was isolated which carried three mutations (C24S/G141D/S207I; Table II and Supplementary Fig. S2A). A second round of mutagenesis and selection yielded clone NAC32.R2, which acquired four additional mutations (V119S/S143T/Q186L/T200S; Table II and Supplementary Fig. S2A) and as a result, conferred significantly greater resistance to cells. Cells expressing back-cloned versions of these intrabody genes exhibited the same resistance phenotype as the originally isolated mutants (data not shown), confirming that the greater resistance conferred by these clones was due to mutations in scFv-NAC32 and not elsewhere in the plasmid. Like clone m3 above, NAC32.R2 exhibited a >3-fold improvement in antigen-binding activity (Fig. 4B). However, unlike m3, soluble expression for NAC32.R2 was nearly identical to that observed for the parental NAC32 intrabody (Fig. 4C). Based on these results, we hypothesized that the increased resistance conferred by clone NAC32.R2 was the result of affinity enhancement. To test this notion, we measured the equilibrium dissociation constant, KD, for NAC32 and NAC32.R2. Indeed, clone NAC32.R2 had ∼8-fold increased affinity for α-syn(A53T) compared with the parental NAC32 clone (KD values of 5.8 versus 46 nM, respectively; Table II and Supplementary Fig. S2B). Hence, FLI-TRAP selection can yield both stability-enhanced and affinity-matured intrabodies in as few as one to two rounds of mutagenesis and selection.

Fig. 4.

Direct selection of improved NAC32 variants. (A) Selective plating of Escherichia coli MC4100 cells co-expressing α-syn(A53T)-Bla with ssTorA-NAC32 or FLI-TRAP-selected NAC32 variants. Overnight cultures were serially diluted in liquid LB and plated on LB agar supplemented with Carb. Clone NAC32.R1 was derived from wt NAC32 following an initial round of error-prone PCR mutagenesis and selection on 50 μg/ml Carb. A second round of error-prone PCR mutagenesis, using NAC32.R1 as template, and selection on 100 μg/ml Carb was used to isolate NAC32.R2. (B) Antigen binding activity and (C) western blot analysis of NAC32 and FLI-TRAP-selected variants. NAC32 and its derivatives were expressed from plasmid pET-28a without the ssTorA signal peptide and with a C-terminal FLAG epitope tag. Binding activity in cell lysates was measured by ELISA with microtiter plates coated with α-syn(A53T) as antigen. Western blot analysis of soluble and insoluble fractions was according to standard protocols. Detection was with anti-FLAG antibodies. ELISA data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean of six biological replicates.

Table II.

Characterization of NAC32 and isolated variants

| Clone | VH mutationsa |

Linker | VL mutationsa |

Yieldb (mg/l) | Kdc (nM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDR (#) | FR (#) | (G4S)3 | CDR (#) | FR (#) | |||

| NAC32 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.5 | 46 |

| NAC32.R1 | – | C24S (1) | G141D | – | S207I (3) | ND | ND |

| NAC32.R2 | – | C24S (1), V119S (4) | G141D, S143T | T200S (2) | Q186L (2), S207I (3) | 0.2 | 5.8 |

aValues in parentheses refer to CDR or framework number. See Supplementary Fig. S2A for complete sequences.

bYields of purified scFv intrabodies from a representative experiment determined by total protein assay.

cEquilibrium dissociation constants determined by SPR using Biacore 3000.

ND, not determined.

Discussion

Intrabodies have shown great potential as therapeutics for infectious diseases, neurodegenerative disorders and cancer (Marasco et al., 1999; Miller and Messer, 2005; Williams and Zhu, 2006), and they are even being tested in cancer clinical trials (Alvarez et al., 2000). To support their continued development, we attempted to adapt the previously described FLI-TRAP method (Waraho and DeLisa, 2009), which directly links receptor–ligand interactions with antibiotic resistance. We hypothesized that increasing the antibiotic selection pressure could be used to optimize the intracellular stability and/or affinity of intrabodies in cases where the starting sequence already had moderate levels of both (i.e. conferred low but measurable resistance to cells). To test this hypothesis, cells expressing combinatorial intrabody libraries in the FLI-TRAP framework were challenged to grow on high concentrations of antibiotic (i.e. above the minimum inhibitory concentration, MIC, for the interaction of the parental antibody with its antigen). Isolated clones exhibited intracellular stability and antigen-binding affinity that greatly exceeded that of their progenitor clones. In all cases reported here, enhancement of intrabody traits resulted from just a handful of mutations that were acquired in just one or two rounds of laboratory evolution. It should be pointed out that additional cycles of mutagenesis and selection could be performed to further enhance stability and affinity as desired, although whether there is a ceiling that limits the affinities or stabilities achievable is an open question. Alternatively, FLI-TRAP could also be used to facilitate the conversion of traditional scFv antibodies into functional intrabodies for use as possible therapeutic leads or in the development of small molecules toward relevant epitopes, most importantly when there are no specific small-molecule lead candidates available.

A unique aspect of this method is the natural incorporation of the Tat folding QC mechanism, which precludes export of aggregated proteins and protein complexes (Rodrigue et al., 1999; Sanders et al., 2001; Bruser et al., 2003; DeLisa et al., 2003; Fisher et al., 2006; Rocco et al., 2012). In the FLI-TRAP context, folding QC effectively eliminates poorly folded scFv clones and allows screening for intracellular stability and antigen binding in a single step. It is noteworthy that previous attempts to use the Tat QC mechanism for optimizing intrabody folding and stability have been reported (Fisher and DeLisa, 2009; Fisher et al., 2011). In these earlier reports, an antigen-independent selection strategy was used to evolve anti-β-galactosidase scFv antibodies with greatly increased intracellular stability (Fisher et al., 2006). However, to obtain functional clones required the sequential application of a second screening step to recover clones with antigen-binding activity.

The power of the FLI-TRAP selection is that intracellular stability and binding affinity are assayed simultaneously in a single experiment, thereby ensuring both properties are, at a minimum, maintained in all isolated intrabodies. For example, antigen-dependent FLI-TRAP selection yielded a variant of scFv-GCN4, whose greatly increased intracellular stability was achieved while retaining binding affinity that rivaled that of its parental clone. Interestingly, despite the similar affinities, the on- and off-rates for m3 were both faster, suggesting that the way m3 binds its antigen has changed and that this change is somehow favorable in the context of Tat hitchhiker export. Likewise, antigen-dependent FLI-TRAP selection also yielded a NAC32 variant whose binding affinity was significantly increased without compromising intracellular fitness. In light of the generally accepted principle of stability–function tradeoffs (Meiering et al., 1992; Beadle and Shoichet, 2002; Wang et al., 2002), it is significant that our strategy effectively optimizes one trait (e.g. protein stability) while minimizing its constraining effects in a manner that does not impair another trait (e.g. protein function) and, although not observed here, may even facilitate the simultaneous optimization of both traits.

Supplementary data

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation Career Award (grant number CBET-0449080 (to M.P.D.)), the National Cancer Institute at National Institutes of Health (grant number CA132223A (to M.P.D.)) New York State Office of Science, Technology and Academic Research Distinguished Faculty Award (to M.P.D.), a Thai Royal Government Fellowship (to D.W. and B.M.), a National Institutes of Health Chemical Biology Interface Training Grant (grant number T32 GM008500 (to A.D.P.)), and a National Science Foundation GK12 Fellowship (to A.D.P.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Andreas Pluckthun and Anne Messer for plasmid DNA used in these studies.

References

- Alvarez R.D., Barnes M.N., Gomez-Navarro J., et al. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000;6:3081–3087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balch W.E., Morimoto R.I., Dillin A., Kelly J.W. Science. 2008;319:916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.1141448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beadle B.M., Shoichet B.K. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;321:285–296. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00599-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger C., Weber-Bornhauser S., Eggenberger J., Hanes J., Pluckthun A., Bosshard H.R. FEBS Lett. 1999;450:149–153. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00458-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruser T., Yano T., Brune D.C., Daldal F. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003;270:1211–1221. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo A., Biocca S. Trends Biotechnol. 1999;17:115–121. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(98)01268-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline K., McCaffery M. EMBO J. 2007;26:3039–3049. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisa M.P., Tullman D., Georgiou G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:6115–6120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937838100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- der Maur A.A., Zahnd C., Fischer F., Spinelli S., Honegger A., Cambillau C., Escher D., Pluckthun A., Barberis A. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:45075–45085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher A.C., DeLisa M.P. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher A.C., DeLisa M.P. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;385:299–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher A.C., Kim W., DeLisa M.P. Protein Sci. 2006;15:449–458. doi: 10.1110/ps.051902606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher A.C., Rocco M.A., DeLisa M.P. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011;705:53–67. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-967-3_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch C., Kolmar H., Schmidt A., Kleemann G., Reinhardt A., Pohl E., Uson I., Schneider T.R., Fritz H.J. Fold Des. 1996;1:431–440. doi: 10.1016/s1359-0278(96)00059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gushchina L.V., Gabdulkhakov A.G., Filimonov V.V. Mol. Biol. (Mosk) 2009;43:483–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagihara Y., Kim P.S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:6619–6624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102172099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagihara Y., Matsuda T., Yumoto N. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:24752–24758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503963200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl F.U., Hayer-Hartl M. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:574–581. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong E., Davidson A.R., Kaiser C.A. J. Cell Biol. 1996;135:623–633. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.3.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynds P.J., Robinson D., Robinson C. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:34868–34874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.34868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson A.J., Lim H.K., Xu H., Rocco M.A., Bratkowski M.A., Ke A., DeLisa M.P. J. Mol. Biol. 2012;416:94–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski J.M., Parekh R.N., Mao J., Wittrup K.D. J. Biol. Chem. 1998a;273:19453–19458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski J.M., Parekh R.N., Wittrup K.D. Biochemistry. 1998b;37:1264–1273. doi: 10.1021/bi9722397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L.L., Ha H., Chang Y.T., DeLisa M.P. Protein Sci. 2009;18:277–286. doi: 10.1002/pro.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P.A., Tullman-Ercek D., Georgiou G. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;60:373–395. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch S.M., Zhou C., Messer A. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;377:136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marasco W.A., LaVecchio J., Winkler A. J. Immunol. Methods. 1999;231:223–238. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiering E.M., Serrano L., Fersht A.R. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;225:585–589. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90387-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller T.W., Messer A. Mol. Ther. 2005;12:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer T., Berks B.C. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:483–496. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavoor T.V., Cho Y.K., Shusta E.V. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:11895–11900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902828106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proba K., Honegger A., Pluckthun A. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;265:161–172. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribnicky B., Van Blarcom T., Georgiou G. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:631–639. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter S., Lindenstrauss U., Lucke C., Bayliss R., Bruser T. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:33257–33264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703303200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocco M.A., Waraho-Zhmayev D., DeLisa M.P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:13392–13397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210140109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigue A., Chanal A., Beck K., Muller M., Wu L.F. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:13223–13228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders C., Wethkamp N., Lill H. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;41:241–246. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shusta E.V., Kieke M.C., Parke E., Kranz D.M., Wittrup K.D. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;292:949–956. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shusta E.V., Holler P.D., Kieke M.C., Kranz D.M., Wittrup K.D. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:754–759. doi: 10.1038/77325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Minasov G., Shoichet B.K. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;320:85–95. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00400-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waraho D., DeLisa M.P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:3692–3697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704048106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waraho D., DeLisa M.P. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;813:125–143. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-412-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waraho-Zhmayev D., Gkogka L., Yu T.Y., Delisa M.P. Prion. 2013;7:151–156. doi: 10.4161/pri.23328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B.R., Zhu Z. Curr. Med. Chem. 2006;13:1473–1480. doi: 10.2174/092986706776872899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.