Abstract

In recent years, increasing attention has been given to the use and financing of health care for the aged. The authors of this article summarize much of the data related to that use, and present original estimates of health spending in 1984 on behalf of the aged. The estimates are designed to indicate trends in health expenditures and are tied to aggregate personal health care expenditures from the National Health Accounts.

Overview

Spending for health care has become a source of concern for increasing numbers of Americans. From 1977 through 1982, annual personal health care expenditures for all Americans rose at an annual rate of 14 percent, 1 ½ times the rate of growth of the gross national product (Gibson, Waldo, and Levit, 1983). Over that same period, that part of the gross national product used to provide health care goods and services, research, construction, and administration rose from 8.8 percent to 10.5 percent; despite cost containment measures in both the public and private sectors, this upward trend is expected to continue.

Perhaps no group of Americans has a greater stake in the issues raised by the rapid growth of health care spending than the elderly—those 65 years of age or over. The elderly consume a share of the Nation's health care that is disproportionate to their numbers. They have been growing (and will continue to grow) both in numbers and as a proportion of the total population. In 1977, per capita health care spending for people 65 years of age or over was, on the average, 3½ times that for the total population (Fisher, 1980); that ratio is higher today than it was in 1977. Increased numbers of the elderly and increased spending per capita on their behalf have placed enormous pressure on the Medicare program—the financing mechanism through which almost half of the funds for their care flow. The viability of this program, its cost to American workers and taxpayers, and the effects that potential changes in the program would have upon the beneficiary population have sensitized the aged and the Nation to the future of health care spending as never before in modern history.

Demographic characteristics of the aged population

The aged population has increased both in numbers and as a proportion of the total population. There were 27 million people, or 11.7 percent of the total population, 65 years of age or over in the United States in 1983,1 compared with 23 million, or 10.8 percent of the total population in 1977 (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1982, May 1984).2

The aged are living longer. Life expectancy at age 65 was 16.8 years in 1982, up from 16.4 years in 1977 (Table 1). Despite large increases in the number of “recently aged” people (those 65-69), the median age of the aged population rose from 71.6 in 1977 to 71.9 in 1983, reflecting lower death rates for people over 85 years of age.

Table 1. Life expectancy at birth and at 65 years of age, by sex: United States, selected years 1900-1982.

| Year | At birth | At 65 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Both sexes | Male | Female | Both sexes | Male | Female | |

| 19001, 2 | 47.3 | 46.3 | 48.3 | 11.9 | 11.5 | 12.2 |

| 1950 2 | 68.2 | 65.6 | 71.1 | 13.9 | 12.8 | 15.0 |

| 1960 2 | 69.7 | 66.6 | 73.1 | 14.3 | 12.8 | 15.8 |

| 1970 | 70.9 | 67.1 | 74.8 | 15.2 | 13.1 | 17.0 |

| 1971 | 71.1 | 67.4 | 75.0 | 15.2 | 13.2 | 17.1 |

| 1972 | 71.2 | 67.4 | 75.1 | 15.2 | 13.1 | 17.1 |

| 1973 | 71.4 | 67.6 | 75.3 | 15.3 | 13.2 | 17.2 |

| 1974 | 72.0 | 68.2 | 75.9 | 15.6 | 13.4 | 17.5 |

| 1975 | 72.6 | 68.8 | 76.6 | 16.1 | 13.8 | 18.1 |

| 1976 | 72.9 | 69.1 | 76.8 | 16.1 | 13.8 | 18.1 |

| 1977 | 73.3 | 69.5 | 77.2 | 16.4 | 14.0 | 18.4 |

| 1978 | 73.5 | 69.6 | 77.3 | 16.4 | 14.1 | 18.4 |

| 1979 | 73.9 | 70.0 | 77.8 | 16.7 | 14.3 | 18.7 |

| 1980 | 73.7 | 70.0 | 77.5 | 16.4 | 14.1 | 18.3 |

| 1981 3 | 74.1 | 70.3 | 77.9 | 16.7 | 14.3 | 18.7 |

| 1982 3 | 74.5 | 70.8 | 78.2 | 16.8 | 14.4 | 18.8 |

Death registration area only. The death registration area increased from 10 States and the District of Columbia in 1900 to the coterminous United States in 1933.

Includes deaths of nonresidents of the United States.

Provisional data.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics: Health United States, 1983. DHHS Pub. No. (PHS) 84-1232. Public Health Service. Washington. U.S. Government Printing Office, Dec. 1983.

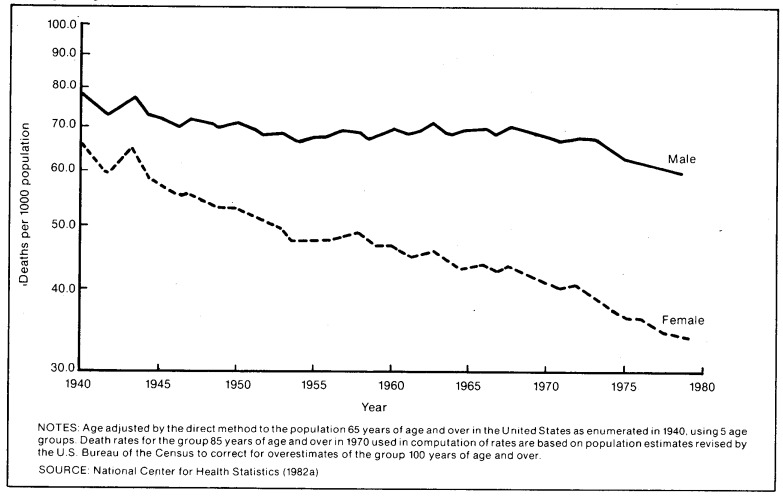

The death rate for the aged has been falling steadily, especially for women (Figure 1). The overall age-adjusted death rate for people 65 years of age or over fell 29 percent during 1950-82.3 The death rate for males in 1980 ranged from 34 deaths per 1,000 men aged 65-69 years to 188 per 1,000 men aged 85 years or over, approximately a quarter less than 1940 rates. Rates for females dropped 35 to 50 percent, ranging from 17 deaths per 1,000 women 65-69 years to 148 per 1,000 women 85 years or over (National Center for Health Statistics, 1984). Some causes of death have become relatively less frequent than others; for example, from 1950 through 1982 the age-adjusted death rate for the aged attributable to diseases of the heart fell 34 percent and that for cerebrovascular diseases dropped 56 percent; however, the rate for malignant neoplasms rose 15 percent (National Center for Health Statistics, 1983a).

Figure 1. Age-adjusted death rates for persons 65 years of age or over, by sex: United States, 1940-78.

During 1977-83, there was little change in the employment status of the aged population. Data from a sample of the U.S. noninstitutional population show a decline in the proportion of the population 65 years of age or over still in the labor force, from 13.1 percent in 1977 to 11.7 percent in 1983 (Table 2). The unemployment rate for this age group was 3.7 percent in 1983, up slightly from previous years but lower than in 1977. As time progressed from 1977 through 1983, the employed elderly were found more frequently in nonagricultural wage and salary jobs, and less frequently in agricultural and household jobs (Table 3). Almost half the employed elderly were part-time workers by choice, and another third held full-time jobs of 40 hours or less per week (Table 4). Reflecting the recent economic recession, slightly fewer of the employed elderly worked more than 40 hours a week in 1983 than in 1977, and slightly more were employed part time. Of the population 60 years of age or over not in the labor force, almost 90 percent were retired or keeping house; there was a decline in the proportion who withdrew from the labor force because of illness or disability, to about 7 percent in 1983 (Table 5).

Table 2. Number and percent distribution of the noninstitutional population 65 years of age or over, by average employment status: United States, 1977-1983.

| Year | Civilian noninstitutional population | Civilian labor force | Total | Not in the labor force | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Total | Employed | Unemployed | |||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Total | Percent of labor force | Keeping house | Going to school | Unable to work | Other reasons | ||||||

| Numbers in thousands | |||||||||||

| 1977 | 22,264 | 2,909 | 2,762 | 147 | 5.1 | 19,355 | 9,832 | 11 | 1,035 | 8,477 | |

| 1978 | 22,789 | 3,043 | 2,919 | 124 | 4.1 | 19,746 | 9,903 | 8 | 1,030 | 8,805 | |

| 1979 | 23,344 | 3,073 | 2,969 | 104 | 3.4 | 20,271 | 9,863 | 14 | 1,079 | 9,315 | |

| 1980 | 23,891 | 3,021 | 2,927 | 94 | 3.1 | 20,870 | 9,896 | 11 | 1,036 | 9,927 | |

| 1981 | 24,379 | 3,007 | 2,910 | 97 | 3.2 | 21,372 | 9,865 | 7 | 1,009 | 10,491 | |

| 1982 | 25,388 | 3,029 | 2,922 | 107 | 3.5 | 22,359 | 10,249 | 6 | 963 | 11,141 | |

| 1983 | 25,893 | 3,041 | 2,927 | 114 | 3.7 | 22,852 | 10,337 | 11 | 961 | 11,543 | |

| Percent distribution | |||||||||||

| 1977 | 100.0 | 13.1 | 12.4 | 0.7 | 86.9 | 44.2 | .0 | 4.6 | 38.1 | ||

| 1978 | 100.0 | 13.4 | 12.8 | 0.5 | 86.6 | 43.5 | .0 | 4.5 | 38.6 | ||

| 1979 | 100.0 | 13.2 | 12.7 | 0.4 | 86.8 | 42.3 | 0.1 | 4.6 | 39.9 | ||

| 1980 | 100.0 | 12.6 | 12.3 | 0.4 | 87.4 | 41.4 | .0 | 4.3 | 41.6 | ||

| 1981 | 100.0 | 12.3 | 11.9 | 0.4 | 87.7 | 40.5 | .0 | 4.1 | 43.0 | ||

| 1982 | 100.0 | 11.9 | 11.5 | 0.4 | 88.1 | 40.4 | .0 | 3.8 | 43.9 | ||

| 1983 | 100.0 | 11.7 | 11.3 | 0.4 | 88.3 | 39.9 | .0 | 3.7 | 44.6 | ||

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics: Household data from the Current Population Survey, 1977-1984.

Table 3. Number and percent distribution of employed persons 65 years of age or over, by class of worker: United States, 1977-1983.

| Year | Total | Nonagricultural industries | Agriculture | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Wage and salary workers | Self employed | Unpaid family workers | Wage and salary workers | Self employed | Unpaid family workers | |||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Total | Private household workers | Government | Other | |||||||

| Number in thousands | ||||||||||

| 1977 | 2,763 | 1,895 | 172 | 302 | 1,421 | 503 | 25 | 63 | 257 | 20 |

| 1978 | 2,919 | 2,018 | 181 | 303 | 1,534 | 522 | 25 | 76 | 262 | 16 |

| 1979 | 2,969 | 2,076 | 173 | 337 | 1,566 | 540 | 26 | 78 | 233 | 16 |

| 1980 | 2,928 | 2,071 | 150 | 358 | 1,564 | 533 | 19 | 59 | 232 | 13 |

| 1981 | 2,913 | 2,044 | 141 | 337 | 1,567 | 547 | 19 | 50 | 237 | 15 |

| 1982 | 2,922 | 2,051 | 140 | 337 | 1,574 | 556 | 19 | 45 | 239 | 12 |

| 1983 | 2,926 | 2,054 | 130 | 337 | 1,587 | 566 | 21 | 45 | 224 | 16 |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||||

| 1977 | 100.0 | 68.6 | 6.2 | 10.9 | 51.4 | 18.2 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 9.3 | 0.7 |

| 1978 | 100.0 | 69.1 | 6.2 | 10.4 | 52.6 | 17.9 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 9.0 | 0.5 |

| 1979 | 100.0 | 69.9 | 5.8 | 11.4 | 52.7 | 18.2 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 7.8 | 0.5 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 70.7 | 5.1 | 12.2 | 53.4 | 18.2 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 7.9 | 0.4 |

| 1981 | 100.0 | 70.2 | 4.8 | 11.6 | 53.8 | 18.8 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 8.1 | 0.5 |

| 1982 | 100.0 | 70.2 | 4.8 | 11.5 | 53.9 | 19.0 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 8.2 | 0.4 |

| 1983 | 100.0 | 70.2 | 4.4 | 11.5 | 54.2 | 19.3 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 7.7 | 0.5 |

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics: Household data from the Current Population Survey, 1977-1984.

Table 4. Number and percent distribution of persons 65 years of age or over at work in nonagricultural industries, by full- or part-time status: United States, 1977-1983.

| Year | Total at work | On part time for economic reasons | On voluntary part time | On full-time schedules | Average hours | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Total | 40 hours or less | 41 hours or more | All workers | Workers on full-time schedules | ||||

| Number in thousands | ||||||||

| 1977 | 2,201 | 87 | 1,071 | 1,043 | 707 | 336 | 29.1 | 43.1 |

| 1978 | 2,334 | 98 | 1,151 | 1,085 | 736 | 349 | 28.6 | 42.8 |

| 1979 | 2,404 | 102 | 1,169 | 1,133 | 798 | 335 | 29.0 | 42.4 |

| 1980 | 2,391 | 99 | 1,164 | 1,128 | 786 | 342 | 29.0 | 42.5 |

| 1981 | 2,377 | 99 | 1,151 | 1,127 | 806 | 321 | 28.9 | 42.0 |

| 1982 | 2,389 | 121 | 1,146 | 1,122 | 801 | 321 | 29.1 | 42.5 |

| 1983 | 2,408 | 118 | 1,154 | 1,136 | 803 | 333 | 29.2 | 42.7 |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||

| 1977 | 100.0 | 4.0 | 48.7 | 47.4 | 32.1 | 15.3 | — | — |

| 1978 | 100.0 | 4.2 | 49.3 | 46.5 | 31.5 | 15.0 | — | — |

| 1979 | 100.0 | 4.2 | 48.6 | 47.1 | 33.2 | 13.9 | — | — |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 4.1 | 48.7 | 47.2 | 32.9 | 14.3 | — | — |

| 1981 | 100.0 | 4.2 | 48.4 | 47.4 | 33.9 | 13.5 | — | — |

| 1982 | 100.0 | 5.1 | 48.0 | 47.0 | 33.5 | 13.4 | — | — |

| 1983 | 100.0 | 4.9 | 47.9 | 47.2 | 33.3 | 13.8 | — | — |

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics: Household data from the Current Population Survey, 1977-1984.

Table 5. Number and percent distribution of persons 60 years of age or over not in the labor force, by job desire and reasons not seeking work: United States, 1977-1983.

| Item | 1977 | 1978 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number in thousands | |||||||

| Total not in labor force | 24,270 | 24,725 | 25,294 | 26,082 | 26,845 | 28,176 | 28,747 |

| Do not want a job now | 23,672 | 24,132 | 24,749 | 25,546 | 26,302 | 27,573 | 28,195 |

| Current activity: Going to school | 18 | 11 | 22 | 15 | 12 | 10 | 21 |

| III, disabled | 2,177 | 2,183 | 2,196 | 2,076 | 2,044 | 1,985 | 1,898 |

| Keeping house | 12,176 | 12,177 | 12,188 | 12,352 | 12,291 | 12,845 | 12,962 |

| Retired | 8,769 | 9,158 | 9,728 | 10,505 | 11,335 | 12,043 | 12,679 |

| Other | 532 | 603 | 615 | 598 | 620 | 690 | 635 |

| Want a job now | 588 | 594 | 544 | 537 | 543 | 601 | 556 |

| Reason for not looking: School attendance | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| III health, disability | 174 | 177 | 170 | 155 | 164 | 168 | 147 |

| Home responsibilities | 38 | 41 | 33 | 38 | 34 | 32 | 37 |

| Think cannot get a job: | 214 | 180 | 152 | 176 | 181 | 238 | 212 |

| Job market factors | 93 | 74 | 68 | 74 | 88 | 131 | 109 |

| Personal factors | 122 | 106 | 83 | 103 | 92 | 107 | 103 |

| Other reasons | 159 | 193 | 185 | 162 | 160 | 160 | 153 |

| Percent distribution | |||||||

| Total not in labor force | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Do not want a job now | 97.5 | 97.6 | 97.8 | 97.9 | 98.0 | 97.9 | 98.1 |

| Current activity: Going to school | 0.1 | .0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | .0 | .0 | 0.1 |

| III, disabled | 9.0 | 8.8 | 8.7 | 8.0 | 7.6 | 7.0 | 6.6 |

| Keeping house | 50.2 | 49.2 | 48.2 | 47.4 | 45.8 | 45.6 | 45.1 |

| Retired | 36.1 | 37.0 | 38.5 | 40.3 | 42.2 | 42.7 | 44.1 |

| Other | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.2 |

| Want a job now | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.9 |

| Reason for not looking: School attendance | .0 | .0 | .0 | .0 | .0 | .0 | .0 |

| III health, disability | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Home responsibilities | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Think cannot get a job: | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| Job market factors | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Personal factors | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Other reasons | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics: Household data from the Current Population Survey, 1977-1984.

From 1977 through 1982, money income of households headed by an elderly person increased faster than the rate of consumer price inflation. During that same period, the median income of these households rose 74 percent, from $6,300 in 1977 to $11,000 in 1982 (Table 6). This increase exceeded substantially the 49-percent increase in the median income of all households and a 59-percent growth in the annual average of the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers.

Table 6. Number and percent distribution of households with an aged head, by total money income: United States, 1977 and 1982.

| Total money income | 1977 | 1982 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Number in thousands | Percent | Number in thousands | Percent | |

| Total | 15,226 | 100.0 | 17,672 | 100.0 |

| Under $5,000 | 5,909 | 38.8 | 2,952 | 16.7 |

| $5,000-9,999 | 4,857 | 31.9 | 5,154 | 29.2 |

| 10,000-14,999 | 2,052 | 13.5 | 3,117 | 17.6 |

| 15,000-17,499 | 598 | 3.9 | 1,123 | 6.4 |

| 17,500-19,999 | 409 | 2.7 | 897 | 5.1 |

| 20,000-24,999 | 557 | 3.7 | 1,480 | 8.4 |

| 25,000-29,999 | 330 | 2.2 | 861 | 4.9 |

| 30,000-49,999 | 377 | 2.5 | 1,426 | 8.1 |

| 50,000 and over | 137 | 0.9 | 662 | 3.7 |

| Median income | $6,347 | — | $11,041 | — |

| Mean income | $9,309 | — | $15,869 | — |

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of the Census (1978, February 1984)

Although employment status and money income influence the ability to finance consumption of health care, the presence of third-party reimbursement reduces the importance of the income-consumption link found in so many other markets. Because enrollees and providers both tend to treat health insurance as a permanent reducer of the cost of health care (rather than as a deferrment or shifting of that cost), more health care tends to be used at any given price or income level or health status than would otherwise be the case. The very high incidence of Medicare enrollment, the availability of Medicaid benefits, and the increasing purchase of individual “Medigap” private health insurance policies have effectively reduced the point-of-purchase price of health care over time, to the extent that it may even be treated by some as a “free” good, divorced from the premiums paid for coverage.

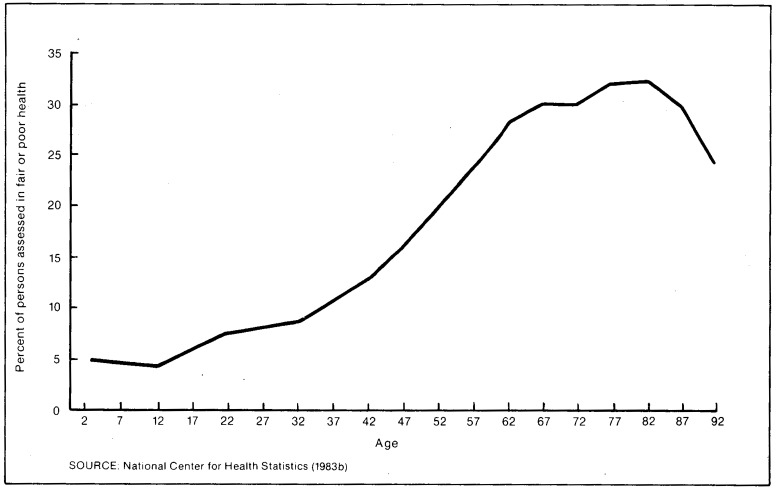

In recent years, there has not been much change in the way aged Americans perceive their health status. The results of a survey of the noninstitutionalized population, in which respondents were asked to assess their own health, showed that in 1981 30 percent of those 65 and over believed themselves to be in “fair” or “poor” health compared with others in their age group, almost unchanged from responses in 1976 (Table 7). By excluding the institutionalized aged, most of whom would assess their health as fair or poor, the survey oversampled the healthy in the aged population, but the results are interesting none the less. In a study of responses for 1978, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) observed that “self-assessed health status has been found to be highly associated with an individual's … utilization of health-care services. For instance, … persons assessed to be in excellent health spent 3.3 days in bed per person per year due to illness or injury and made 2.5 doctor visits per person per year, while the corresponding estimates for persons assessed to be in poor health were 64.2 bed days and 15.3 doctor visits per person per year” (National Center for Health Statistics, Mar. 1983). It should be noted that the direction of causality is both ways: increased doctor visits may induce a low assessment of health status, and a low assessment of health status may induce more doctor visits. Further, the incidence of fair or poor self-assessed health status increases with age, up to age 80, even though respondents were asked to rank themselves in relation to their age cohort (Figure 2 and Table 8). In the NCHS study of 1978 responses, the decline in the percent of people self-assessed in fair or poor health after age 80 was attributed largely to the relatively high rate of institutionalization or death for the group; those who remain uninstitutionalized were much more likely to be in the healthier part of the subgroup than was the case for younger subgroups.

Table 7. Percent of population, by self-assessment of health, limitation of activity, and age: United States, 1976 and 1981.

| Age | Self-assessment of health as fair or poor | With limitation of activity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Total | Limited but not in major activity | Limited in amount or kind of major activity | Unable to carry on major activity | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| 1976 | 1981 | 1976 | 1981 | 1976 | 1981 | 1976 | 1981 | 1976 | 1981 | |

| Percent of population | ||||||||||

| Total1 | 12.1 | 11.8 | 13.9 | 13.7 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 7.0 | 6.8 | 3.4 | 3.6 |

| Under 17 years | 4.3 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Under 6 years | 4.5 | 4.2 | 2.5 | 2.2 | — | — | 2.1 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 6-16 years | 4.2 | 3.8 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 17-44 years | 8.3 | 8.3 | 8.9 | 8.4 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| 45-64 years | 22.2 | 22.0 | 24.3 | 23.9 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 13.1 | 12.4 | 5.9 | 6.8 |

| 65 years or over | 31.3 | 30.1 | 45.4 | 45.7 | 6.0 | 6.6 | 21.8 | 21.7 | 17.6 | 17.5 |

Age adjusted by the direct method to the 1970 civilian noninstitutional population, using 4 age intervals.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics: Health United States, 1983. DHHS Pub. No. (PHS) 84-1232. Public Health Service. Washington. U.S. Government Printing Office, Dec. 1983.

Figure 2. Percent of persons assessed in fair or poor health by age: United States, 1978.

Table 8. Number of persons and percent distribution, by respondent-assessed health status and age: United States, 1978.

| Age | All persons | Respondent-assessed health status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| All health statuses | Excellent or good | Fair or poor | Excellent | Good | Fair | Poor | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Number in thousands | Percent distribution 1 | Percent distribution 2 | ||||||

| All ages | 213,828 | 100.0 | 87.6 | 12.4 | 48.6 | 38.5 | 9.5 | 2.8 |

| Under 5 years | 15,389 | 100.0 | 95.3 | 4.7 | 60.7 | 33.7 | 4.2 | 0.5 |

| 5-9 years | 16,860 | 100.0 | 95.5 | 4.5 | 60.0 | 34.8 | 4.0 | 0.5 |

| 10-14 years | 18,531 | 100.0 | 95.9 | 4.1 | 60.2 | 35.1 | 3.7 | 0.4 |

| 15-19 years | 20,550 | 100.0 | 94.4 | 5.7 | 56.7 | 37.2 | 5.0 | 0.6 |

| 20-24 years | 19,414 | 100.0 | 92.8 | 7.2 | 52.9 | 39.6 | 6.4 | 0.8 |

| 25-29 years | 17,487 | 100.0 | 92.3 | 7.7 | 53.5 | 38.5 | 6.7 | 1.0 |

| 30-34 years | 15,526 | 100.0 | 91.5 | 8.5 | 53.3 | 37.9 | 6.8 | 1.7 |

| 35-39 years | 12,749 | 100.0 | 89.5 | 10.5 | 50.8 | 38.3 | 8.4 | 2.0 |

| 40-44 years | 11,134 | 100.0 | 87.5 | 12.5 | 47.1 | 40.1 | 9.8 | 2.7 |

| 45-49 years | 11,251 | 100.0 | 84.1 | 15.9 | 42.1 | 41.6 | 12.2 | 3.7 |

| 50-54 years | 11,720 | 100.0 | 80.0 | 20.0 | 38.2 | 41.5 | 14.4 | 5.5 |

| 55-59 years | 10,964 | 100.0 | 75.7 | 24.3 | 32.9 | 42.5 | 16.8 | 7.4 |

| 60-64 years | 9,468 | 100.0 | 72.4 | 27.6 | 30.7 | 41.3 | 19.6 | 7.8 |

| 65-69 years | 8,243 | 100.0 | 70.2 | 29.8 | 28.5 | 41.2 | 21.6 | 8.1 |

| 70-74 years | 6,353 | 100.0 | 70.3 | 29.7 | 28.4 | 41.2 | 21.2 | 8.2 |

| 75-79 years | 4,297 | 100.0 | 68.3 | 31.7 | 25.9 | 41.9 | 23.0 | 8.4 |

| 80-84 years | 2,429 | 100.0 | 68.0 | 32.0 | 26.7 | 41.0 | 22.0 | 9.8 |

| 85-89 years | 1,062 | 100.0 | 70.3 | 29.7 | 32.5 | 37.9 | 18.3 | 11.5 |

| 90-94 years | 311 | 100.0 | 76.4 | 23.6 | 35.4 | 39.2 | 16.4 | 36.8 |

| 95 years or over | 93 | 100.0 | 67.7 | 332.3 | 329.0 | 38.7 | 318.3 | 314.0 |

Excludes persons with health status not assessed.

Includes persons with health status not assessed.

Relative standard error of 30 percent or more.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, Mar. 1983.

The aged tend to use more hospital care per capita than the general population does. A survey of non-Federal short-stay hospitals showed 10.7 million elderly patients discharged in 1982, 28 percent of all discharges (National Center for Health Statistics, Dec. 1983). Those estimates imply a discharge rate of 399 per 1,000 population for the aged, up 12.4 percent from a rate of 355 per 1,000 in 1977 (Table 9).4 By comparison, the discharge rate for the entire population (168 per 1,000 in 1982) was essentially unchanged over the period, and it actually declined somewhat if deliveries are excluded from the analysis.

Table 9. Discharges from non-Federal short-stay hospitals, by age: United States, 1977-1982.

| Year | All ages | 65 years of age or over | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Total | Excluding deliveries | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Number in thousands | Percent change | Per 1,000 population | Number in thousands | Percent change | Per 1,000 population | Number in thousands | Percent change | Per 1,000 population | |

| 1977 | 35,902 | — | 167 | 32,570 | — | 152 | 8,344 | — | 355 |

| 1978 | 35,616 | −0.8 | 164 | 32,255 | −1.0 | 149 | 8,708 | 4.4 | 362 |

| 1979 | 36,747 | 3.2 | 168 | 33,101 | 2.6 | 151 | 9,086 | 4.3 | 368 |

| 1980 | 37,832 | 3.0 | 168 | 34,070 | 2.9 | 151 | 9,864 | 8.6 | 384 |

| 1981 | 38,544 | 1.9 | 169 | 34,631 | 1.6 | 152 | 10,408 | 5.5 | 396 |

| 1982 | 38,593 | 0.1 | 168 | 34,648 | .0 | 151 | 10,697 | 2.8 | 399 |

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics: Data from the National Health Survey, 1977-1982.

NOTE: Discharges per 1,000 population have been recalculated using total civilian population rather than civilian noninstitutional population.

The increase in the discharge rate for the aged population runs counter to other evidence of health status—the Constance over time of self-assessed health status and the slight decline in the percent of the noninstitutionalized population that withdrew from the labor force because of illness or disability. The apparent contradiction can be explained by two factors. First, the declining average length of stay for the aged has been accompanied by an increase in the incidence of multiple admissions during the year (Helbing, 1980, especially pp. 32-33), raising the discharge rate even though days of care per 1,000 population may change little. Second, the effect of increased health insurance coverage would be to increase consumption of health care for any given health status.

A listing of discharges by first-listed diagnosis indicates that diseases of the circulatory system (specifically heart disease) were the most frequent reason for hospitalization for the aged, followed by diseases of the digestive system and malignant neoplasms; the most rapidly growing cause of hospitalization was endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases (including diabetes) (Table 10). Although the average length of a hospital stay has been falling, from 11.1 days for an aged patient in 1977 to 10.1 days in 1982, the aged tend to remain in a hospital longer than the general population does (National Center for Health Statistics, March 1979, Dec. 1983b). By first-listed diagnosis, the aged remain 2 to 3 days longer than average, not significantly different from the 1977 relationship.

Table 10. Number of inpatients discharged from short-stay hospitals, by category of first-listed diagnosis and age: United States, 1977 and 1982.

| Category of first-listed diagnosis | 1977 | 1982 | Percent change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| All ages | Ages 65 + | All ages | Ages 65 + | All ages | Ages 65 + | |

| Discharges in thousands | ||||||

| All conditions | 35,902 | 8,343 | 38,594 | 10,698 | 7.5 | 28.2 |

| Infective and parasitic diseases | 837 | 111 | 695 | 135 | −17.0 | 21.6 |

| Neoplasms | 2,549 | 910 | 2,594 | 1,117 | 1.8 | 22.7 |

| Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases | 941 | 271 | 1,161 | 426 | 23.4 | 57.2 |

| Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs | 298 | 101 | 367 | 151 | 23.2 | 49.5 |

| Mental disorders | 1,625 | 193 | 1,746 | 269 | 7.4 | 39.4 |

| Diseases of the nervous system and sense organs | 1,556 | 476 | 1,828 | 739 | 17.5 | 55.3 |

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 4,758 | 2,471 | 5,488 | 3,128 | 15.3 | 26.6 |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 3,454 | 784 | 3,459 | 1,003 | 0.1 | 27.9 |

| Diseases of the digestive system | 4,298 | 1,073 | 4,628 | 1,354 | 7.7 | 26.2 |

| Diseases of the genitourinary system | 3,565 | 627 | 3,411 | 748 | −4.3 | 19.3 |

| Complications of pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperius | 919 | — | 1,018 | — | 10.8 | — |

| Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | 575 | 106 | 566 | 135 | −1.6 | 27.4 |

| Diseases of the musculoskeletal system | 1,895 | 379 | 2,377 | 578 | 25.4 | 52.5 |

| Congenital abnomalities | 333 | 19 | 335 | 25 | 0.6 | 31.6 |

| Certain causes of perinatal morbidity and mortality | 20 | — | 166 | — | 730.0 | — |

| Symptoms and ill-defined conditions | 699 | 92 | 624 | 88 | −10.7 | −4.3 |

| Accidents, poisonings, and violence | 3,752 | 701 | 3,568 | 747 | −4.9 | 6.6 |

| Special conditions and examinations without sickness, or tests with negative findings | 3,828 | 29 | 4,563 | 55 | 19.2 | 89.7 |

| Discharges per 1,000 population | ||||||

| All conditions | 167 | 355 | 168 | 399 | 0.3 | 12.4 |

| Infective and parasitic diseases | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | −22.5 | 6.6 |

| Neoplasms | 12 | 39 | 11 | 42 | −5.0 | 7.6 |

| Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases | 4 | 12 | 5 | 16 | 15.1 | 37.8 |

| Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs | 1 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 14.9 | 31.0 |

| Mental disorders | 8 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 0.3 | 22.2 |

| Diseases of the nervous system and sense organs | 7 | 20 | 8 | 28 | 9.6 | 36.1 |

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 22 | 105 | 24 | 117 | 7.6 | 11.0 |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 16 | 33 | 15 | 37 | −6.5 | 12.1 |

| Diseases of the digestive system | 20 | 46 | 20 | 50 | 0.5 | 10.6 |

| Diseases of the genitourinary system | 17 | 27 | 15 | 28 | −10.7 | 4.6 |

| Complications of pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperius 1 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3.4 | — |

| Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | 3 | 5 | 2 | 5 | −8.1 | 11.6 |

| Diseases of the musculoskeletal system | 9 | 16 | 10 | 22 | 17.1 | 33.7 |

| Congenital abnormalities | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −6.1 | 15.3 |

| Certain causes of perinatal morbidity and mortality | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 674.6 | — |

| Symptoms and ill-defined conditions | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | −16.7 | −16.2 |

| Accidents, poisonings, and violence | 17 | 30 | 16 | 28 | −11.3 | −6.6 |

| Special conditions and examinations without sickness, or tests with negative findings | 18 | 1 | 20 | 2 | 11.2 | 66.2 |

| All conditions except childbirth | 152 | 355 | 151 | 399 | −0.7 | 12.4 |

| Total civilian population | 214,746 | 23,513 | 230,117 | 26,826 | 7.2 | 14.1 |

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics: Data from the National Health Survey.

Females with deliveries have been moved from this category to “special conditions” for 1977, in order to make the data consistent with those for 1982.

Types of services consumed

The estimates of personal health care expenditures presented in this section are tied to several sources. Estimates of spending for the aged in 1977 are based on the work of Fisher (1980), updated to reflect more recent Medicare and Medicaid data and revised aggregate spending estimates. Projections for 1984 are tied, in addition to Fisher's work, to projections of Medicare and Medicaid spending prepared in HCFA's Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis and to Freeland and Schendler's (1984) projections of national health expenditures.

Spending on behalf of the aged for personal health care—the direct provision of goods and services—has nearly tripled over the last 7 years, rising from a level of $43 billion in 1977 to a projected $120 billion in 1984 (Table 11). From 2.3 percent in 1977, the portion of the gross national product used to provide personal health care for the aged is projected to reach 3.3 percent in 1984. Part of the 15.6-percent annual growth in spending is due to an increase in the sheer number of aged people, whose count increased at a rate of 2.3 percent annually from 1977 to 1984. However, spending per capita rose from $1,785 to a projected $4,202 (Table 12), still averaging a 13-percent annual growth.

Table 11. Personal health care expenditures in millions for people 65 years of age or over, by source of funds and type of service: United States, 1984 and 1977.

| Year and source of funds | Type of service | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Total care | Hospital | Physician | Nursing home | Other care | |

| 1984 | |||||

| Total | $119,872 | $54,200 | $24,770 | $25,105 | $15,798 |

| Private | 39,341 | 6,160 | 9,827 | 13,038 | 10,316 |

| Consumer | 38,875 | 5,964 | 9,818 | 12,856 | 10,237 |

| Out-of-pocket | 30,198 | 1,694 | 6,468 | 12,569 | 9,467 |

| Insurance | 8,677 | 4,270 | 3,350 | 287 | 770 |

| Other private | 466 | 196 | 9 | 182 | 79 |

| Government | 80,531 | 48,040 | 14,943 | 12,067 | 5,482 |

| Medicare | 58,519 | 40,524 | 14,314 | 539 | 3,142 |

| Medicaid | 15,288 | 2,595 | 467 | 10,418 | 1,808 |

| Other government | 6,724 | 4,920 | 162 | 1,110 | 532 |

| Exhibit: Population (in millions) | 28.5 | ||||

| 1977 | |||||

| Total | 43,425 | 18,906 | 7,782 | 10,696 | 6,041 |

| Private | 15,669 | 2,319 | 3,323 | 5,424 | 4,603 |

| Consumer | 15,499 | 2,263 | 3,320 | 5,352 | 4,564 |

| Out-of-pocket | 12,706 | 927 | 2,147 | 5,264 | 4,368 |

| Insurance | 2,793 | 1,336 | 1,173 | 88 | 195 |

| Other private | 170 | 56 | 3 | 72 | 39 |

| Government | 27,756 | 16,587 | 4,458 | 5,272 | 1,438 |

| Medicare | 19,171 | 14,087 | 4,158 | 348 | 578 |

| Medicaid | 6,049 | 733 | 232 | 4,453 | 631 |

| Other government | 2,536 | 1,767 | 68 | 470 | 230 |

| Exhibit: Population (in millions) | 24.3 | ||||

SOURCE: Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Health Care Financing Administration

Table 12. Personal health care expenditures per capita for people 65 years of age or over, by source of funds and type of service: United States, 1984 and 1977.

| Year and source of funds | Type of service | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Total care | Hospital | Physician | Nursing home | Other care | |

| 1984 | |||||

| Total | $4,202 | $1,900 | $868 | $880 | $554 |

| Private | 1,379 | 216 | 344 | 457 | 362 |

| Consumer | 1,363 | 209 | 344 | 451 | 359 |

| Out-of-pocket | 1,059 | 59 | 227 | 441 | 332 |

| Insurance | 304 | 150 | 117 | 10 | 27 |

| Other private | 16 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| Government | 2,823 | 1,684 | 524 | 423 | 192 |

| Medicare | 2,051 | 1,420 | 502 | 19 | 110 |

| Medicaid | 536 | 91 | 16 | 365 | 63 |

| Other government | 236 | 172 | 6 | 39 | 19 |

| 1977 | |||||

| Total | 1,785 | 777 | 320 | 440 | 248 |

| Private | 644 | 95 | 137 | 223 | 189 |

| Consumer | 637 | 93 | 136 | 220 | 188 |

| Out-of-pocket | 522 | 38 | 88 | 216 | 180 |

| Insurance | 115 | 55 | 48 | 4 | 8 |

| Other private | 7 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Government | 1,141 | 682 | 183 | 217 | 59 |

| Medicare | 788 | 579 | 171 | 14 | 24 |

| Medicaid | 249 | 30 | 10 | 183 | 26 |

| Other government | 104 | 73 | 3 | 19 | 9 |

Less than $.50.

SOURCE: Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Health Care Financing Administration

Two-thirds of the expenditures in 1984 for personal health care on behalf of the elderly is projected to come from public programs, mostly from Medicare (Table 13). The hospital insurance and supplementary medical insurance trust funds combined to account for nearly half of the aged health bill (including items, such as prescription drugs, not covered by Medicare). Federal and State Medicaid payments will absorb another 13 percent of the total (principally nursing home care), and other Government programs, mainly the Veterans Administration, will pay 5 percent of the bill.

Table 13. Percent distribution of personal health care expenditures per capita for people 65 years of age or over, by source of funds and type of service: United States, 1984 and 1977.

| Year and source of funds | Type of service | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Total care | Hospital | Physician | Nursing home | Other care | |

| 1984 | |||||

| Total per capita | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Private | 32.8 | 11.4 | 39.7 | 51.9 | 65.3 |

| Consumer | 32.4 | 11.0 | 39.6 | 51.2 | 64.8 |

| Out-of-pocket | 25.2 | 3.1 | 26.1 | 50.1 | 59.9 |

| Insurance | 7.2 | 7.9 | 13.5 | 1.1 | 4.9 |

| Other private | 0.4 | 0.4 | .0 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| Government | 67.2 | 88.6 | 60.3 | 48.1 | 34.7 |

| Medicare | 48.8 | 74.8 | 57.8 | 2.1 | 19.9 |

| Medicaid | 12.8 | 4.8 | 1.9 | 41.5 | 11.4 |

| Other government | 5.6 | 9.1 | 0.7 | 4.4 | 3.4 |

| 1977 | |||||

| Total per capita | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Private | 36.1 | 12.3 | 42.7 | 50.7 | 76.2 |

| Consumer | 35.7 | 12.0 | 42.7 | 50.0 | 75.5 |

| Out-of-pocket | 29.3 | 4.9 | 27.6 | 49.2 | 72.3 |

| Insurance | 6.4 | 7.1 | 15.1 | 0.8 | 3.2 |

| Other private | 0.4 | 0.3 | .0 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Government | 63.9 | 87.7 | 57.3 | 49.3 | 23.8 |

| Medicare | 44.1 | 74.5 | 53.4 | 3.3 | 9.6 |

| Medicaid | 13.9 | 3.9 | 3.0 | 41.6 | 10.4 |

| Other government | 5.8 | 9.3 | 0.9 | 4.4 | 3.8 |

SOURCE: Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Health Care Financing Administration

The remaining third of personal health care expenditures for the aged will be paid mostly by consumers of care. About a quarter of the aged health bill in 1984—consisting of coinsurance, deductibles, and noncovered services and goods—is projected to be paid with “out-of-pocket” funds. In addition, private health insurance, including Medigap policies, is projected to cover 7 percent of total spending.

Two-thirds of the money spend on health care for the aged goes for institutional care (Table 14). In 1984, hospital care is projected to account for 45 percent of the total, and nursing home care to absorb another 21 percent. Expenditures for physicians' services will account for 21 percent of the total; of the remaining 13 percent, about half will be for services of dentists and other health practitioners and half for consumer durable and nondurable goods.

Table 14. Percent distribution of personal health care expenditures per capita for people 65 years of age or over by type of service, according to source of funds: United States, 1984 and 1977.

| Year and source of funds | Total per capita | Type of service | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Total | Hospital | Physician | Nursing home | Other Care | ||

| 1984 | ||||||

| Total per capita | $4,202 | 100.0 | 45.2 | 20.7 | 20.9 | 13.2 |

| Private | 1,379 | 100.0 | 15.7 | 25.0 | 33.1 | 26.2 |

| Consumer | 1,363 | 100.0 | 15.3 | 25.3 | 33.1 | 26.3 |

| Out-of-pocket | 1,059 | 100.0 | 5.6 | 21.4 | 41.6 | 31.3 |

| Insurance | 304 | 100.0 | 49.2 | 38.6 | 3.3 | 8.9 |

| Other private | 16 | 100.0 | 42.1 | 1.9 | 39.1 | 17.0 |

| Government | 2,823 | 100.0 | 59.7 | 18.6 | 15.0 | 6.8 |

| Medicare | 2,051 | 100.0 | 69.2 | 24.5 | 0.9 | 5.4 |

| Medicaid | 536 | 100.0 | 17.0 | 3.1 | 68.1 | 11.8 |

| Other government | 236 | 100.0 | 73.2 | 2.4 | 16.5 | 7.9 |

| 1977 | ||||||

| Total per capita | 1,785 | 100.0 | 43.5 | 17.9 | 24.6 | 13.9 |

| Private | 644 | 100.0 | 14.8 | 21.2 | 34.6 | 29.4 |

| Consumer | 637 | 100.0 | 14.6 | 21.4 | 34.5 | 29.4 |

| Out-of-pocket | 522 | 100.0 | 7.3 | 16.9 | 41.4 | 34.4 |

| Insurance | 115 | 100.0 | 47.9 | 42.0 | 3.1 | 7.0 |

| Other private | 7 | 100.0 | 32.7 | 1.9 | 42.5 | 22.9 |

| Government | 1,141 | 100.0 | 59.8 | 16.1 | 19.0 | 5.2 |

| Medicare | 788 | 100.0 | 73.5 | 21.7 | 1.8 | 3.0 |

| Medicaid | 249 | 100.0 | 12.1 | 3.8 | 73.6 | 10.4 |

| Other government | 104 | 100.0 | 69.7 | 2.7 | 18.6 | 9.1 |

SOURCE: Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Health Care Financing Administration

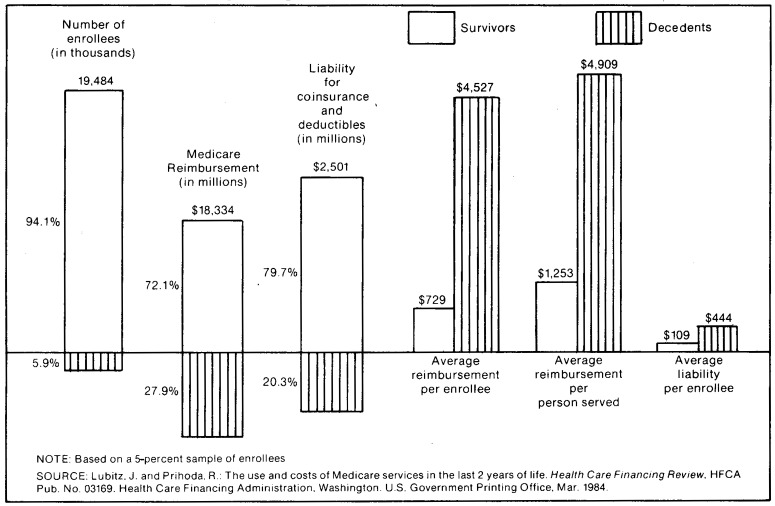

One of the reasons why the aged account for a disproportionate share of spending for health care is that the last year of a person's life tends to be very health care intensive, a factor that weighs more heavily upon the aged population than upon younger cohorts. A recent study of the Medicare population, comparing reimbursement and use of services by enrollees who died in 1978 with those of enrollees who survived the year, illustrates this point (Lubitz and Prihoda, 1984). The study reported that reimbursements per user were four times as great for enrollees who died during the year as for those who did not die (Figure 3). Decedents comprised 6 percent of the group studied and accounted for 28 percent of Medicare reimbursement. Hospital discharges per 1,000 enrollees were five times as great for decedents as for survivors, and days of care per 1,000 enrollees were seven times as high (Table 15). Assuming that the direction, if not the magnitude, of this relation translates to the general population, it is easy to see how the aged, with relatively high death rates, could spend more per capita for health care on this basis alone.

Figure 3. Medicare utilization by the aged: decedents last year of life vs. survivors in 1978.

Table 15. Selected measures of short-stay hospital use by Medicare decedents in their last year, and survivors, by age: All areas, 1978.

| Measure and age | Survival status | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Decedents | Survivors | |

| Persons hospitalized | Per 1,000 enrollees | |

| 67 years or over | 739 | 202 |

| 67-74 years | 769 | 179 |

| 75 years or over | 727 | 226 |

| Discharges | Per person hospitalized | |

| 67 years or over | 2.1 | 1.5 |

| 67-74 years | 2.3 | 1.4 |

| 75 years or over | 2.0 | 1.5 |

| Discharges | Per 1,000 enrollees | |

| 67 years or over | 1,537 | 294 |

| 67-74 years | 1,771 | 260 |

| 75 years or over | 1,444 | 330 |

| Days of care | ||

| 67 years or over | 20,607 | 3,033 |

| 67-74 years | 23,795 | 2,530 |

| 75 years or over | 19,342 | 3,566 |

| Average length of stay | In days | |

| 67 years or over | 13.4 | 10.3 |

| 67-74 years | 13.4 | 9.7 |

| 75 years or over | 13.4 | 10.8 |

NOTE: Based on a 5-percent sample of enrollees.

SOURCE: Lubitz J. and Prihoda R.: The use and costs of Medicare services in the last 2 years of life. Health Care Financing Review. HCFA Pub. No. 03169. Health Care Financing Administration. Washington, U.S. Government Printing Office, Mar. 1984.

The major components of spending for health on behalf of the elderly, as noted earlier, are hospital and nursing home care and physicians' services.

Hospital care

Hospital care for the aged is projected to cost $54 billion in 1984, up an average of 16.2 percent per year since 1977; this is an amount equal to $1,900 per capita. Medicare reimbursement will account for three-quarters of that amount, and Medicaid, the Veterans' Administration, and other Government programs each will pay about 5 percent of the bill. Private health insurance benefits will cover 8 percent of total spending for hospital care, and philanthropic sources will fund another half percent. The remaining 3 percent (for coinsurance, deductibles, and noncovered services) will be paid “out of pocket.” (Further discussion of this type of expenditure can be found later in this article.)

In addition to the hospital discharge data discussed earlier and the Medicare data to be discussed later, there is additional evidence that hospital use among the elderly is increasing. In a survey of community hospitals, the American Hospital Association found that admissions among the elderly reached a level of 11.8 million in 1983, an average increase of 4.8 percent per year since 1977 (Hospital Data Center, 1983). Patient days for the aged rose 3.0 percent annually, to a 1983 level of 114 million, and the length of stay fell, from 10.7 days in 1977 to 9.7 in 1983. (During the same period, admissions for the rest of the population fell 0.4 percent per year, and inpatient days fell 1.1 percent per year.)

Nursing home care

Nursing home care includes services provided in all facilities or parts of facilities that are Medicare- or Medicaid-certified skilled nursing homes, Medicaid-certified intermediate care homes, or any other home providing some level of nursing care, whether certified by either program or not. Facilities that provide only domiciliary care are excluded.

Based on 1984 estimates, spending for nursing home care for the aged is projected to have grown an average of 13 percent per year since 1977; 1984 estimates imply an expenditure of $880 per person. There has not been much change in the way in which this care has been financed; about half of the money comes from patients and their families and most of the rest comes from Government programs. Medicaid paid 42 percent of the bill, and Medicare (which provides limited coverage of nursing home care) paid 2 percent. Private health insurance coverage of nursing home care is minimal, leaving a large out-of-pocket liability for consumers of care.

The growth of expenditure for nursing home services is attributable to price inflation, to increased numbers of aged people, and to changes in the number and types of days of care per capita for the aged.

The most recent national data for nursing home residents showed a wide variety in the monthly charges for nursing home care (National Center for Health Statistics, July 1979). Charges varied by age of resident, ranging from $656 per month in 1977 for residents 65-69 years of age to $755 per month for those 95 years of age or over. Monthly charges also varied by length of stay, with lower monthly charges being associated with longer lengths of stay (and, presumably, more chronic conditions as opposed to acute conditions). Although charge data do not exist for more recent periods, prices paid by nursing homes for goods and services used to provide care increased 8.4 percent per year on average between 1977 and 1983.

The number of aged people in nursing homes has increased, in absolute terms and as a fraction of the aged population. According to the 1970 Decennial Census of Population, 0.8 million people 65 years of age or over were in homes for the aged and dependent; 1.2 million such people were enumerated in the 1980 census, an annual increase of 4.5 percent. The group increased in size from 4.0 percent of the 1970 population to 4.8 percent of the 1980 population. The proportion of the population in nursing homes in 1977 varied with age, from 1 percent of those 65-69 years of age to 22.6 percent of those 85 years or over (National Center for Health Statistics, July 1979, U.S. Bureau of the Census 1982). The percent of residents that required assistance in one or more daily activities (bathing, dressing, etc.) rose from 86 percent of residents 65-74 years of age to 96 percent of those 85 years of age or over.

Length of stay initially falls and then rises with age among the aged population. The median length of stay for people 65-69 years of age discharged in 1976 was 62 days; that median dropped to 47 days for people 70-74 years of age and then rose to 379 days for people 95 years or over (National Center for Health Statistics, July 1979). Further, more of the “elderly aged” end their lives in nursing homes: 1976 discharge data from the same survey show that of those 65-69 years of age at discharge, 82 percent were discharged alive, a rate that diminished steadily to the point that only 48 percent of those 95 years or over were alive when discharged.

Physician services

Spending on behalf of the aged for physicians' services grew an average of 18 percent per year from 1977 to 1984, reaching a projected level of $24.8 billion for 1984. Per capita annual growth of 15.3 percent exceeded the 9-percent growth of the consumer price index for physician services, suggesting a substantial increase in use per capita of physician services by the aged. The Medicare program will pay 58 percent of the $870 projected to be spent per capita by the aged in 1984. Another quarter of the total is estimated to be direct patient payments—liability for coinsurance, deductibles, and services not covered by third parties. Private health insurance benefits will pay 14 percent of the total, bringing the consumer share of the total to 40 percent, and Medicaid and other Government programs will pay 3 percent of the bill.

Existing data support the increased consumption of physician care by the elderly. There was little change in the pattern of per capita visits for physician services among the aged noninstitutionalized population from 1977 to 1981: the number of visits increased 2.1 percent per year, less than the 2.8-percent growth of the noninstitutional population; and the number of visits per person and the average time between visits remained almost unchanged over the 4-year period (National Center for Health Statistics, 1978, October 1982). However, a relatively large portion of physician services for the elderly occurs in a hospital, and patient days, as has been noted already, grew 3.0 percent per year during the period 1977-83, faster than the increase in the total aged civilian population (including the institutionalized); physician visits to hospital inpatients are not included in the visits data above. In addition, the number of surgeries and other procedures performed on aged patients has increased dramatically, in numbers, per hospital discharge, and per 1,000 population (National Center for Health Statistics, March 1979, Dec. 1983b). These trends explain much of the growth in physician expenditure per capita among the aged.

Other health care

Spending for health care other than hospital and nursing home care and physicians' services rose 14.7 percent per year from 1977 to 1984, reaching a projected $554 per person in 1984. About two-thirds of this amount will be paid by private sources, and Medicare and Medicaid will pay most of the rest.

The extent of third-party coverage in this category of consumption varies by type of care. The category includes the services of dentists and other health professionals (including home health care), consumer medical durables and nondurables, and care not identified by type or not classified elsewhere. In general, these goods and services tend to be purchased more with out-of-pocket funds than the other classes mentioned above are: although accounting for 13 percent of total spending, they accounted for 31 percent of out-of-pocket spending (Table 14).

Use of goods and services in this group by the aged varies by service. Table 16 shows data collected during the 1977 National Medical Care Expenditure Survey for four such types: prescription drugs, vision aids, medical equipment and supplies, and dentists visits. Except for dentists' services, the data indicate that a greater proportion of the aged than of the general population consume these types of care and that they consume more of these types of care per user than the general population does.

Table 16. Use of other health services and goods, by age: United States, 1977.

| Other health services and goods | Total population | 65 years or over |

|---|---|---|

| Dental visits | ||

| People with at least one visit | 41.1 | 29.9 |

| Visits per person | 1.3 | 1.0 |

| Visits per user1 | 3.2 | 3.3 |

| Prescribed medicine | ||

| People with at least one prescription | 58.2 | 75.2 |

| Prescribed medicines per person | 4.3 | 10.7 |

| Prescribed medicines per user1 | 7.5 | 14.2 |

| Vision aids | ||

| People with purchase or repair of glasses or contact lenses | 12.4 | 16.6 |

| Purchases or repairs of glasses or contact lenses per thousand population | 143 | 193 |

| Medical equipment and supplies | ||

| People with at least one purchase or rental | 6.2 | 13.3 |

| Purchases or rentals per thousand population | 93 | 245 |

| Purchases or rentals per user1 | 1.5 | 1.8 |

A user is a person with at least one of the items in question (a visit, a prescription, etc).

SOURCES: Hagan, M.: Medical equipment and supplies: purchases and rentals, expenditures, and sources of payment. National Health Care Expenditure Study Data Preview No. 10. DHHS Pub. No. (PHS) 82-3321. Public Health Service. Washington. U.S. Government Printing Office, Oct. 1982.

Kasper, J.: Prescribed medicines: use, expenditures, and sources of payment. National Health Care Expenditures Study Data Preview No. 9. DHHS Pub. No. (PHS) 82-3320. Public Health Service. Washington. U.S. Government Printing Office, Oct. 1982.

Rossiter, L: Dental services: use, expenditures, and sources of payment. National Health Care Expenditure Study Data Preview No. 8. DHHS Pub. No. (PHS) 82-3319. Public Health Service. Washington. U.S. Government Printing Office, Oct. 1982.

Walden, D.: Eyeglasses and contact lenses: purchases, expenditures, and sources of payment. National Health Care Expenditure Study Data Preview No. 11. DHHS Pub. No. (PHS) 82-3322. Public Health Service. Washington. U.S. Government Printing Office, Oct. 1982.

Home health care is a benefit covered by Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers as a lower cost alternative to institutional care. Medicare home health benefits, previously limited to 100 visits per benefit period under hospital insurance and 100 visits per calendar year under supplementary medical insurance, were liberalized over time to provide coverage of an unlimited number of home health visits.

Home health care is a growing segment of the health care delivery system. In 1980, 21 million home health visits were made to the aged under Medicare alone,5 up 12.9 percent per year from 1977, serving 888 thousand aged beneficiaries (Table 17). Use of home health services varies by age: 14 out of every 1,000 Medicare enrollees 65-66 years of age received Medicare-reimbursed home health services in 1980, compared with 74 out of every 1,000 85 years and over. Similar variation existed in the number of visits per 1,000 enrollees. Use among the very elderly increased faster between 1977 and 1980 than among the recently aged.

Table 17. Medicare home health services for the aged: Persons served, visits, and charges by age: 1977 and 1980.

| Year and age | Number of enrollees1 | Users | Visits | Charges | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Number | Per 1,000 enrollees | Number | Per user | Per 1,000 enrollees | Total 2 | Amount | Visit charges Per visit | Per user | ||

| 1980 | ||||||||||

| All ages | 25,515 | 888.2 | 34.8 | 20,621 | 23.2 | 808 | $707,125 | $674,840 | $33 | $760 |

| 65-66 | 3,572 | 48.3 | 13.5 | 1,084 | 22.4 | 303 | 38,416 | 36,533 | 34 | 756 |

| 67-68 | 3,335 | 59.1 | 17.7 | 1,324 | 22.4 | 397 | 46,868 | 44,622 | 34 | 755 |

| 69-70 | 3,050 | 66.1 | 21.7 | 1,515 | 22.9 | 497 | 52,694 | 50,263 | 33 | 761 |

| 71-72 | 2,798 | 72.6 | 25.9 | 1,665 | 22.9 | 595 | 57,826 | 55,185 | 33 | 760 |

| 73-74 | 2,459 | 77.3 | 31.4 | 1,789 | 23.1 | 727 | 62,061 | 59,244 | 33 | 766 |

| 75-79 | 4,809 | 203.1 | 42.2 | 4,758 | 23.4 | 989 | 163,443 | 156,328 | 33 | 770 |

| 80-84 | 3,081 | 183.5 | 59.6 | 4,261 | 23.2 | 1,383 | 144,418 | 138,222 | 32 | 753 |

| 85 or over | 2,410 | 178.1 | 73.9 | 4,226 | 23.7 | 1,753 | 141,399 | 134,442 | 32 | 755 |

| 1977 | ||||||||||

| All ages | 23,838 | 642.9 | 27.0 | 14,332 | 22.3 | 601 | 375,769 | 355,178 | 25 | 552 |

| 65-66 | 3,349 | 36.9 | 11.0 | 782 | 21.2 | 234 | 21,012 | 19,810 | 25 | 537 |

| 67-68 | 3,150 | 44.2 | 14.0 | 976 | 22.1 | 310 | 26,330 | 24,796 | 25 | 561 |

| 69-70 | 2,932 | 49.6 | 16.9 | 1,079 | 21.8 | 368 | 28,771 | 27,796 | 26 | 560 |

| 71-72 | 2,585 | 54.0 | 20.9 | 1,202 | 22.3 | 465 | 31,993 | 30,295 | 25 | 561 |

| 73-74 | 2,310 | 57.2 | 24.8 | 1,267 | 22.2 | 548 | 33,661 | 31,943 | 25 | 558 |

| 75-79 | 4,463 | 146.1 | 32.7 | 3,284 | 22.5 | 736 | 86,208 | 81,736 | 25 | 559 |

| 80-84 | 2,963 | 134.4 | 45.4 | 3,004 | 22.4 | 1,014 | 77,559 | 73,482 | 24 | 547 |

| 85 or over | 2,086 | 117.1 | 56.1 | 2,681 | 22.9 | 1,285 | 68,630 | 64,325 | 24 | 549 |

Counts of aged persons enrolled in the hospital insurance and/or supplementary medical insurance programs as of July 1.

Includes charges for durable medical equipment and supplies in addition to visit charges.

NOTE: Based on a 40-percent sample of enrollees.

SOURCES: Callahan (1981) and unpublished data.

The use of home health services by Medicare enrollees is concentrated among a fairly small group of users. Although visits per user averaged 23 in 1980, the median was 12.5—that is, half the people who used home health services in 1980 received 12 visits or fewer. That the mean of the distribution is so much greater than the median indicates that the bulk of visits is received by users at the high end of the range.

Funding personal health care

Like the general population, the aged in the United States have extensive third-party coverage of their health care costs. About three-quarters of the total to be spent on their behalf in 1984 is projected to come from Government programs or private health insurance, a higher proportion than for the general population and slightly higher than the same share in 1977 (Table 13). The largest single source of funds is Medicare, which will pay an estimated $59 billion in 1984 for health care for the aged; private health insurance, on the other hand, while growing rapidly as a source of funds for the elderly, will not be nearly as large a source for the aged as it will be for the general population. In general, the aged receive far more services from Government programs than younger cohorts do.

In addition to personal health care expenditures, the aged or their agents must pay health insurance premiums in order to obtain coverage. Part of these payments are not included in the estimates presented in this article, as will be explained later.

Medicare

The Medicare program was enacted into law on July 30, 1965, as Title XVIII of the Social Security Act—Health Insurance for the Aged. Benefits under its two parts—hospital insurance (HI) and supplementary medical insurance (SMI)—began July 1, 1966. From 1977 to 1984, Medicare's share of health care spending for the elderly increased from 44 percent to 49 percent of the total. In 1984, Medicare is projected to finance $59 billion of the estimated $120 billion spent on behalf of the elderly, making it the largest public source of funding for personal health care expenditures for the aged.

Hospital insurance covers inpatient care in a hospital or skilled nursing facility and home health visits. Supplementary medical insurance covers a variety of medical services and supplies furnished by physicians or others in connection with physicians' services, outpatient hospital services, and home health services. There are limits on services covered (Health Care Financing Administration, 1983) and cost-sharing features associated with each of these programs.

Enrollment

The number of aged people covered by the Medicare program increased from 23.8 million in 1977 to 27.1 million in 1983, an average annual increase of 2.2 percent (Table 18). The aged population has grown over twice as fast as the total population during this 6-year period due to a number of factors, including improved health status and declining birth rates. Most of the elderly are covered by the Medicare program; the current slight decline in the proportion covered is expected to be reversed as employees of nonprofit organizations and of the Federal Government “age” into the program.

Table 18. Number of aged Medicare enrollees, percent of total population, percent of population 65 years of age or over, and type of coverage: All areas, 1977-1983.

| Year | Hospital insurance and/or supplementary medical insurance in millions | Percent of total population1 | Percent of population 65 years or over1 | Type of coverage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Hospital insurance and supplementary medical insurance in millions | Hospital insurance only in millions | Supplementary medical insurance only in millions | ||||

| 1977 | 23.8 | 10.4 | 97.2 | 22.6 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| 1978 | 24.4 | 10.5 | 96.9 | 23.1 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| 1979 | 24.9 | 10.7 | 96.8 | 23.7 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| 1980 | 25.5 | 10.8 | 96.8 | 24.3 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| 1981 | 26.0 | 10.9 | 96.6 | 24.8 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| 1982 | 26.5 | 11.0 | 96.5 | 25.3 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| 1983 | 27.1 | 11.1 | 96.5 | 25.9 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| Average annual percent change | 2.2 | 1.1 | −0.1 | 2.2 | −0.6 | 3.2 |

Social Security Administration, Social Security Area Population Estimates. Population data for 1983 are projections.

SOURCE: Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, Health Care Financing Administration.

Coverage under this program was extended to Federal employees under the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982; Social Security coverage was mandated for employees of nonprofit organizations under the Social Security Amendments of 1983. (See the 1983 annual HI report (Board of Trustees, 1983) for further details).

The age and sex composition of the aged HI population has changed over time. The median age of the group increased from 73.0 years of age in 1977 to 73.2 years of age in 1983. Also, the number of enrollees 85 years of age or over grew from 9 percent of the aged population in 1977 to over 10 percent in 1983 (Table 19). The HI aged population currently has a slightly higher proportion of women than in 1977. In 1983, there were 3 females for every 2 males 65 years of age or over (Table 20). In the age group 85 years or over, the ratio of females to males was 5 to 2.

Table 19. Aged Medicare hospital insurance enrollees: Number and percent distribution by age, median age, and rate of persons 85 years or over per 100 persons 65-69 years: All areas, July 1, 1966-1983.

| Year | Number in thousands | Percent distribution by age | Median age (years) | Number of persons 85 + per 100 persons age 65-69 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Total | 65-69 | 70-74 | 75-79 | 80-84 | 85 + | ||||

| 1966 | 19,082 | 100.0 | 34.1 | 28.7 | 19.8 | 11.2 | 6.2 | 72.6 | 18 |

| 1970 | 20,361 | 100.0 | 33.3 | 27.2 | 20.3 | 12.0 | 7.2 | 73.0 | 22 |

| 1975 | 22,472 | 100.0 | 33.5 | 26.3 | 19.3 | 12.5 | 8.4 | 73.0 | 25 |

| 1977 | 23,475 | 100.0 | 33.4 | 26.2 | 19.0 | 12.6 | 8.9 | 73.0 | 27 |

| 1980 | 25,104 | 100.0 | 33.1 | 26.3 | 18.8 | 12.2 | 9.6 | 73.0 | 29 |

| 1981 | 25,591 | 100.0 | 32.9 | 26.3 | 18.9 | 12.1 | 9.8 | 73.1 | 30 |

| 1982 | 26,115 | 100.0 | 32.6 | 26.3 | 18.9 | 12.2 | 10.0 | 73.2 | 31 |

| 1983 | 26,670 | 100.0 | 32.4 | 26.2 | 19.0 | 12.2 | 10.1 | 73.2 | 31 |

NOTE: Detail may not add to total due to rounding.

SOURCE: Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, Health Care Financing Administration and unpublished data.

Table 20. Aged Medicare hospital insurance enrollees: Percent distribution by sex and race, and rate of males per 100 females: All areas, 1966-1983.

| Year | Total persons | Male | Female | Number of males per 100 females | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Total | White | All other races | Unknown | Total | White | All other races | Unknown | |||

| 1966 | 100.0 | 42.6 | 38.6 | 3.4 | 0.6 | 57.4 | 50.8 | 4.1 | 2.5 | 74 |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 41.8 | 37.4 | 3.5 | 0.9 | 58.2 | 51.9 | 4.4 | 1.9 | 72 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 40.8 | 36.2 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 59.2 | 52.8 | 4.7 | 1.7 | 69 |

| 1977 | 100.0 | 40.6 | 36.0 | 3.7 | 1.0 | 59.4 | 52.9 | 4.8 | 1.7 | 68 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 40.4 | 35.7 | 3.7 | 1.1 | 59.5 | 52.9 | 4.9 | 1.7 | 68 |

| 1981 | 100.0 | 40.4 | 35.6 | 3.7 | 1.1 | 59.6 | 52.9 | 5.0 | 1.7 | 68 |

| 1982 | 100.0 | 40.4 | 35.6 | 3.7 | 1.1 | 59.6 | 52.9 | 5.0 | 1.7 | 68 |

| 1983 | 100.0 | 40.3 | 35.5 | 3.7 | 1.1 | 59.7 | 52.9 | 5.0 | 1.8 | 68 |

NOTE: Detail may not add to total due to rounding.

SOURCE: Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, Health Care Financing Administration and unpublished data.

Users

In 1982, over 17 million aged enrollees, 641 out of every 1,000 enrolled, were “users,” that is, they received Medicare-reimbursed services after satisfying the program deductible. The number of aged users increased 5.8 percent per year from 1977 through 1981, rising to 65.5 percent of aged enrollees before dropping in 1982. By the end of 1984, it is expected that 66 out of every 100 enrollees will have received reimbursed services during the year (Tables 21 and 22).

Table 21. Number of aged Medicare enrollees served under hospital insurance and/or supplementary medical insurance, rate per 1,000 enrolled, amount reimbursed per person served, and percent change by age: All areas, 1977, 1981, and 19821.

| Age | Persons served | Person served per 1,000 enrolled | Reimbursement per person served | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Number in thousands | Annual percent change | Rate | Annual percent change | Average | Annual percent change | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| 1977 | 1981 | 1982 | 1977-81 | 1981-82 | 1977 | 1981 | 1982 | 1977-81 | 1981-82 | 1977 | 1981 | 1982 | 1977-81 | 1981-82 | |

| Total 65 years and over | 13,584 | 17,036 | 17,023 | 5.8 | −0.1 | 569.8 | 655.0 | 641.4 | 3.5 | −2.1 | $1,332 | $2,024 | $2,439 | 11.0 | 20.5 |

| 65-74 | 7,714 | 9,519 | 9,406 | 5.4 | −1.2 | 538.4 | 615.8 | 600.1 | 3.4 | −2.6 | 1,193 | 1,800 | 2,172 | 10.8 | 20.7 |

| 75-84 | 4,509 | 5,644 | 5,698 | 5.8 | 1.0 | 607.2 | 701.7 | 690.8 | 3.7 | −1.6 | 1,478 | 2,243 | 2,705 | 11.0 | 20.6 |

| 85 or over | 1,361 | 1,873 | 1,919 | 8.3 | 2.4 | 652.5 | 746.3 | 733.0 | 3.4 | −1.8 | 1,636 | 2,507 | 2,960 | 11.3 | 18.1 |

Date include experience for persons who exceeded the annual Medicare deductibles and for whom reimbursements were made. The SMI annual deductible increased from $60 to $75 effective January 1, 1982. For that reason, comparisons of data for periods after 1981 with data for 1981 and earlier may be misleading.

NOTE: Based on a 5-percent sample of enrollees.

SOURCE: Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, Health Care Financing Administration and unpublished data.

Table 22. Number of aged Medicare enrollees served per 1,000 enrolled, by type of coverage: United States, 1977-19841.

| Type of coverage | Calendar year | Average annual percent change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| 1977 | 1978 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 19832 | 1984 2 | 1977-81 | 1982-84 | |

| Hospital insurance and/or supplementary medical insurance | 570 | 594 | 610 | 638 | 655 | 641 | 655 | 660 | 3.5 | 1.5 |

| Hospital insurance | 231 | 232 | 232 | 240 | 243 | 251 | 255 | 260 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| Supplementary medical insurance | 581 | 607 | 624 | 652 | 669 | 654 | 660 | 670 | 3.6 | 1.2 |

Data include experience for persons who exceeded the annual Medicare deductibles and for whom reimbursements were made. The SMI annual deductible increased from $60 to $75 on January 1, 1982. For that reason, comparisons of data for periods after 1981 with data for 1981 and earlier may be misleading.

Estimated.

NOTE: Based on a 5-percent sample of enrollees.

SOURCE: Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, Health Care Financing Administration.

In 1982, the SMI deductible was raised from $60 to $75. Persons incurring allowed charges under SMI in excess of $60 but less than $76 were not included in the 1982 estimate of persons served. However, persons incurring these charges were included in the 1981 estimates and earlier. The effect of the increase in the SMI deductible would be even greater if one were to adjust for the effects of inflation upon medical costs.

User rates vary with age (Table 21). In 1982, 733 enrollees per 1,000 aged 85 years or over received reimbursed services, compared to 600 per 1,000 aged 65-74 years. However, use rates have grown at about the same rate for each of the age cohorts—about 3 ½ percent per year between 1977 and 1981.

Reimbursement per user is not uniform for Medicare enrollees in age groups 65-74, 75-84, and 85 years or over. For example, there is a 36-percent difference between the reimbursement of $2,200 per user 65-74 years of age and that of $3,000 per user 85 years and over (Table 21). Although reimbursement was made for services provided to three-fifths of the enrolled population, about 2 percent of enrollees accounted for a third of the reimbursements and 8 percent accounted for two-thirds (Table 23).

Table 23. Number of aged Medicare enrollees with and without reimbursement under hospital insurance and/or supplementry medical insurance, by reimbursement interval: United States, 1977, 1981, and 1982.

| Enrollees | Reimbursement | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Item | Number in millions | Percent distribution | Cumulative percent | Amount in millions | Percent distribution | Cumulative percent |

| 1982 | ||||||

| All aged persons enrolled | 28.0 | 100.0 | — | $41,526 | 100.0 | — |

| Persons with no reimbursement | 11.0 | 39.2 | 100.0 | — | — | — |

| Persons with reimbursement1 | 17.0 | 60.8 | — | 41,526 | 100.0 | — |

| Reimbursement interval: | ||||||

| Less than $100 | 4.1 | 14.7 | 60.8 | 188 | 0.5 | 100.0 |

| $100-499 | 5.1 | 18.2 | 46.2 | 1,225 | 3.0 | 99.5 |

| 500-1,499 | 2.4 | 8.4 | 27.9 | 2,119 | 5.1 | 96.6 |

| 1,500-2,999 | 1.7 | 6.2 | 19.5 | 3,788 | 9.1 | 91.5 |

| 3,000-4,999 | 1.3 | 4.5 | 13.3 | 4,954 | 11.9 | 82.4 |

| 5,000-9,999 | 1.4 | 4.9 | 8.8 | 9,707 | 23.4 | 70.4 |

| 10,000-14,999 | 0.5 | 1.9 | 3.9 | 6,527 | 15.7 | 47.1 |

| 15,000 or more | 0.5 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 13,017 | 31.3 | 31.3 |

| 1981 | ||||||

| All aged persons enrolled | 27.5 | 100.0 | — | 34,490 | 100.0 | — |

| Persons with no reimbursement | 10.4 | 38.0 | 100.0 | — | — | — |

| Persons with reimbursement1 | 17.0 | 62.0 | — | 34,490 | 100.0 | — |

| Reimbursement interval: | ||||||

| Less than $100 | 4.7 | 17.1 | 62.0 | 214 | 0.6 | 100.0 |

| $100-499 | 5.2 | 18.8 | 44.9 | 1,212 | 3.5 | 99.4 |

| 500-1,499 | 2.3 | 8.2 | 26.1 | 2,042 | 5.9 | 95.9 |

| 1,500-2,999 | 1.7 | 6.2 | 17.9 | 3,699 | 10.7 | 89.9 |

| 3,000-4,999 | 1.2 | 4.3 | 11.7 | 4,569 | 13.2 | 79.2 |

| 5,000-9,999 | 1.2 | 4.5 | 7.5 | 8,635 | 25.0 | 66.0 |

| 10,000-14,999 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 5,340 | 15.5 | 40.9 |

| 15,000 or more | 0.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 8,779 | 25.5 | 25.5 |

| 1977 | ||||||

| All aged persons enrolled | 25.2 | 100.0 | — | 18,098 | 100.0 | — |

| Persons with no reimbursement | 11.6 | 46.1 | 100.0 | — | — | — |

| Persons with reimbursement1 | 13.6 | 53.9 | — | 18,098 | 100.0 | — |

| Reimbursement interval: | ||||||

| Less than $100 | 4.7 | 18.5 | 53.9 | 203 | 1.1 | 100.0 |

| $100-499 | 3.7 | 14.5 | 35.3 | 831 | 4.6 | 98.9 |

| 500-1,499 | 2.0 | 7.8 | 20.8 | 1,854 | 10.2 | 94.3 |

| 1,500-2,999 | 1.4 | 5.7 | 13.0 | 3,085 | 17.0 | 84.0 |

| 3,000-4,999 | 0.9 | 3.4 | 7.3 | 3,362 | 18.6 | 67.0 |

| 5,000 or more | 1.0 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 8,764 | 48.4 | 48.4 |

Data include experience for persons who exceeded the annual Medicare deductibles and for whom reimbursements were made. The SMI annual deductible increased from $60 to $75 effective January 1, 1982. For that reason, comparisons of data for periods after 1981 with data for 1981 and earlier may be misleading.

NOTE: Based on a 5-percent sample of enrollees.

SOURCE: Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, Health Care Financing Administration and unpublished data.

Funding

Two separate trust funds were established under the Social Security Act to pay benefits and administrative expenses for the Medicare program. Two-thirds of Medicare benefit expenditures are paid from the hospital insurance (HI) trust fund, primarily for inpatient hospital care. The other third is paid from the supplementary medical insurance (SMI) trust fund for physician and related care (Table 24).

Table 24. Medicare hospital insurance and supplementary medical insurance disbursements, by type: All areas, fiscal years 1977-1983.

| Fiscal years | Hospital and supplementary medical insurance | Hospital insurance | Supplementary medical insurance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Benefit payments | Administrative expenses | Total | Benefit payments | Administrative expenses1 | Total | Benefit payments | Administrative expenses | Total | |

|

| |||||||||

| Amount in millions | |||||||||

| 1977 | $20,773 | $ 776 | $21,549 | $14,906 | $301 | $15,207 | $ 5,867 | $475 | $ 6,342 |

| 1978 | 24,263 | 955 | 25,218 | 17,411 | 451 | 17,862 | 6,852 | 504 | 7,356 |

| 1979 | 28,150 | 1,007 | 29,157 | 19,891 | 452 | 20,343 | 8,259 | 555 | 8,814 |

| 1980 | 33,934 | 1,090 | 35,025 | 23,790 | 497 | 24,288 | 10,144 | 593 | 10,737 |

| 1981 | 41,252 | 1,236 | 42,488 | 28,907 | 353 | 29,260 | 12,345 | 883 | 13,228 |

| 1982 | 49,149 | 1,275 | 50,424 | 34,343 | 521 | 34,864 | 14,806 | 754 | 15,560 |

| 1983 | 55,589 | 1,346 | 56,935 | 38,102 | 522 | 38,624 | 17,487 | 824 | 18,311 |

Includes costs of experiments, demonstration projects, and Peer Review Organizations.

NOTE: Totals do not necessarily equal the sum of rounded components.

SOURCE: Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, Health Care Financing Administration.

The HI trust fund is financed primarily through a tax on a portion of current earnings in employment covered under Social Security, with a small amount of voluntary premiums and interest income. In 1983, the maximum amount of annual earnings to which the tax applied was $35,700, and the contribution rate was 1.30 percent of taxable earnings. The same rate applied to employers, employees, and self-employed people6. Approximately 90 percent of HI income is from payroll taxes. Employers pay a slightly larger share of payroll taxes than employees do because of the limit on taxes an individual worker must pay. The employers' share of taxes was 49 percent, the employees' share was 48 percent, and that of the self-employed was 3 percent in 1983 (Table 25). In 1983, the working population, employees and self-employed, contributed $18 billion to the HI trust fund through payroll taxes.

Table 25. Medicare: Hospital Insurance Trust Fund income and percent distribution of payroll taxes by type: Fiscal years 1977-1983.

| Fiscal year | Total income | Payroll taxes | Voluntary premiums | Other income | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Total | Employer | Employee | Self-employed | ||||

| Amount in millions | |||||||

| 1977 | $15,374 | $13,649 | $ 6,714 | $ 6,477 | $ 457 | $11 | $1,714 |

| 1978 | 18,543 | 16,677 | 8,235 | 7,949 | 494 | 12 | 1,854 |

| 1979 | 21,910 | 19,927 | 9,815 | 9,482 | 630 | 17 | 1,967 |

| 1980 | 25,415 | 23,244 | 11,420 | 11,084 | 739 | 17 | 2,154 |

| 1981 | 32,863 | 30,425 | 15,023 | 14,603 | 799 | 21 | 2,417 |

| 1982 | 37,611 | 34,390 | 16,872 | 16,405 | 1,113 | 25 | 3,195 |

| 1983 | 43,940 | 36,387 | 18,295 | 17,158 | 934 | 26 | 7,528 |

| Percent distribution of payroll taxes | |||||||

| 1977 | — | 100.0 | 49.2 | 47.5 | 3.3 | — | — |

| 1978 | — | 100.0 | 49.4 | 47.7 | 3.0 | — | — |

| 1979 | — | 100.0 | 49.3 | 47.6 | 3.2 | — | — |

| 1980 | — | 100.0 | 49.1 | 47.7 | 3.2 | — | — |

| 1981 | — | 100.0 | 49.4 | 48.0 | 2.6 | — | — |

| 1982 | — | 100.0 | 49.1 | 47.7 | 3.2 | — | — |

| 1983 | — | 100.0 | 50.3 | 47.2 | 2.6 | — | — |

1984 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund and unpublished data.

NOTE: Totals do not necessarily equal the sum of rounded components.

SOURCE: Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, Health Care Financing Administration.

Aged people who are not eligible for Medicare hospital insurance coverage through Social Security are permitted to enroll in HI voluntarily by paying a monthly premium. The HI premium was $45 per month in the first half of 1977 and $54 per month in the second half of the year. During 1983, the monthly premium was $113, and it is set at $155 currently in 1984. Only a small percent of HI enrollees purchase HI coverage each year. In 1977, 22,000 aged people paid the HI premium for 1 month or more, and in 1981, 25,000 paid the premium. Trust fund income from voluntary premiums paid by aged HI enrollees increased from $11 million in fiscal year 1977 to $26 million in fiscal year 1983. (Estimates of consumer payments for personal health care for the aged in this report do not include these nor SMI premiums.)

The SMI trust fund is financed from two sources—monthly premiums paid by or on behalf of enrollees and Federal general tax revenue.

Over time, the proportion of trust fund income accounted for by individual premiums has fallen, leaving taxpayers to foot an increasing share of SMI expenditures. Originally, the monthly SMI premium was designed to cover one-half of program costs, so that enrollees and Government would share the bill equally. By law, however, the premium could be raised by no more than the percentage increase in social security benefits, while SMI costs increased at a much faster rate. Consequently, increased infusions of general revenues were needed to pay program obligations. In 1983, Federal revenue contributions for the aged amounted to $12 billion, three times as much as the $4 billion paid in monthly premiums (Table 26)7.

Table 26. Medicare Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund income: Fiscal years 1977-83.

| Fiscal year | Total income | Premiums | Government contributions | Other Income | Ratio of Government contribution to premiums | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Total | Aged | Disabled | Total1 | Aged | Disabled | Total | Aged | Disabled | |||

| 1977 | $ 7,383 | $2,193 | $1,987 | $206 | $5,053 | $4,026 | $1,009 | $137 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 4.9 |

| 1978 | 9,045 | 2,431 | 2,186 | 245 | 6,386 | 4,965 | 1,398 | 228 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 5.7 |