Abstract

Although growing more slowly than in recent years, spending for health continued to account for an increasing share of the Nation's gross national product. In 1983, spending for health amounted to 10.8 percent of the gross national product, or $1,459 per person. Public programs financed 40 percent of all personal health care spending. Medicare and Medicaid expended $91 billion in benefits, 29 percent of all spending for personal health. New estimates of spending in calendar year 1983, along with revised measures of the benefits paid by private health insurers, are presented here.

The United States spent an estimated $355 billion for health in 1983, an amount equal to 10.8 percent of the gross national product. Highlights of the figures that underly this estimate include the following:

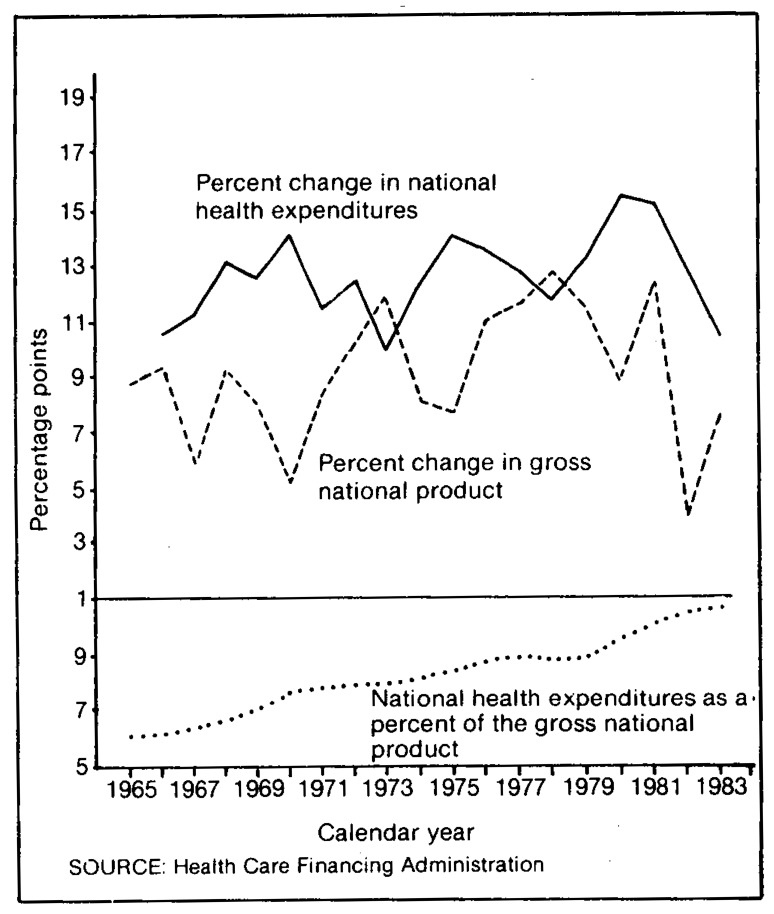

Health expenditures grew 10.3 percent between 1982 and 1983 (Figure 1).

Health expenditures amounted to $1,459 per person in 1983, $122 more than 1982. Of that amount, $611 came from public funds.

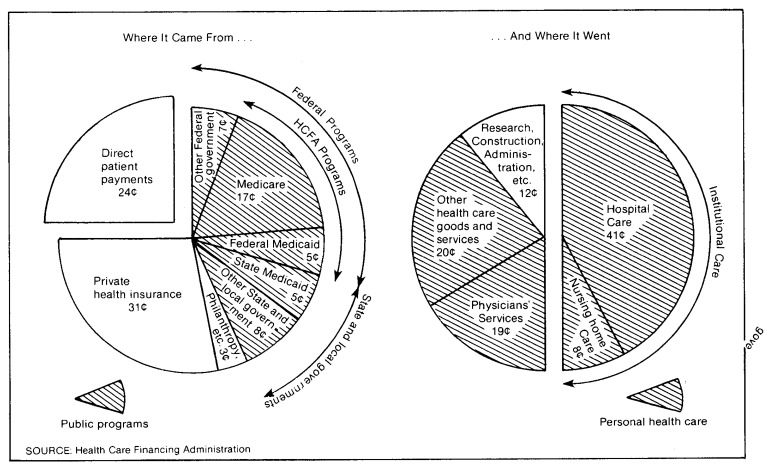

Hospital care accounted for 41 percent of total health care spending in 1983 (Figure 2). These expenditures rose to a level of $147 billion—an increase of 9.1 percent from 1982.

Spending for the services of physicians increased 11.7 percent to $69 billion—19 percent of all health care spending.

Public sources provided 42 cents of every dollar spent on health in 1983. Federal payments amounted to $103 billion, and $46 billion came from State and local governments.

Consumers paid $196 billion for health care in 1983, either directly or (together with employers) in the form of health insurance premiums.

All third parties combined—private health insurers, Government, private charities, and industry—financed 73 percent of the $313 billion spent for personal health care in 1983, covering 92 percent of hospital care services, 72 percent of physicians' services, and 44 percent of the remainder.

Outlays for health care benefits by the Medicare and Medicaid programs totaled $91 billion, including $54 billion for hospital care. The two programs combined paid for 29 percent of all personal health care in the Nation.

Figure 1. National health expenditures and gross national product and national health expenditures as a percent of the gross national product: 1965-1983.

Figure 2. The Nation's health dollar in 1983.

Overview

As shown in Table 1, expenditures for health reached $355 billion in 1983, an increase of 10.3 percent from 1982 and an amount equal to 10.8 percent of the gross national product (GNP). Although real growth—exclusive of price inflation—lagged behind the rest of the economy by a small margin, price inflation for health-related goods and services was much more rapid than that for other goods and services. The inflation effect being dominant, the share of our Nation's production accounted for by health increased from 10.5 percent in 1982 to 10.8 percent in 1983. Rapid growth of health costs, which places increasing financial strain on Federal programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, and the Veterans' Administration, as well as upon purchasers of private health insurance, has sparked a national debate of the philosophy and direction of health care financing.

Table 1. Aggregate and per capita national health expenditures, by source of funds and percent of gross national product: Selected calendar years, 1929-83.

| Item | 1983 | 1982 | 1981 | 1980 | 1979 | 1978 | 1977 | 1976 | 1975 | 1974 | 1973 | 1972 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National health expenditures in billions | $355.4 | $322.3 | $285.8 | $248.0 | $215.1 | $190.0 | $170.2 | $150.8 | $132.7 | $116.3 | $103.4 | $93.9 |

| Percent of the Gross National Product | 10.8 | 10.5 | 9.7 | 9.4 | 8.9 | 8.8 | 8.9 | 8.8 | 8.6 | 8.1 | 7.8 | 7.9 |

| Source of funds in billions | ||||||||||||

| Private expenditures | $206.6 | $186.5 | $164.2 | $142.2 | $124.2 | $110.1 | $100.1 | $87.9 | $76.3 | $68.8 | $64.0 | $58.5 |

| Public expenditures | 148.8 | 135.8 | 121.7 | 105.8 | 90.9 | 79.9 | 70.1 | 62.8 | 56.4 | 47.6 | 39.4 | 35.4 |

| Federal expenditures | 102.7 | 93.3 | 83.5 | 71.1 | 61.0 | 53.8 | 47.4 | 42.6 | 37.1 | 31.0 | 25.2 | 22.9 |

| State and local expenditures | 46.1 | 42.6 | 38.1 | 34.8 | 29.8 | 26.1 | 22.7 | 20.3 | 19.3 | 16.6 | 14.2 | 12.5 |

| Per capita expenditures1 | $1,459 | $1,337 | $1,197 | $1,049 | $920 | $822 | $743 | $665 | $590 | $522 | $468 | $429 |

| Private expenditures | 848 | 774 | 688 | 601 | 531 | 476 | 437 | 388 | 340 | 309 | 290 | 268 |

| Public expenditures | 611 | 564 | 510 | 448 | 389 | 346 | 306 | 277 | 251 | 214 | 178 | 162 |

| Federal expenditures | 422 | 387 | 350 | 301 | 261 | 233 | 207 | 188 | 165 | 139 | 114 | 105 |

| State and local expenditures | 189 | 177 | 160 | 147 | 128 | 113 | 99 | 89 | 86 | 75 | 64 | 57 |

| Percent distribution of funds | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Private funds | 58.1 | 57.9 | 57.4 | 57.3 | 57.7 | 57.9 | 58.8 | 58.3 | 57.5 | 59.1 | 61.9 | 62.3 |

| Public funds | 41.9 | 42.1 | 42.6 | 42.7 | 42.3 | 42.1 | 41.2 | 41.7 | 42.5 | 40.9 | 38.1 | 37.7 |

| Federal funds | 28.9 | 28.9 | 29.3 | 28.7 | 28.4 | 28.4 | 27.9 | 28.2 | 28.0 | 26.6 | 24.4 | 24.4 |

| State and local funds | 13.0 | 13.2 | 13.3 | 14.0 | 13.9 | 13.7 | 13.3 | 13.5 | 14.5 | 14.3 | 13.7 | 13.3 |

| Addenda | ||||||||||||

| Gross national product (billions) | $3,304.8 | $3,069.2 | $2,957.8 | $2,631.7 | $2,417.8 | $2,163.9 | $1,918.3 | $1,718.0 | $1,549.2 | $1,434.2 | $1,326.4 | $1,185.9 |

| Population in millions | 243.6 | 241.1 | 238.7 | 236.4 | 233.8 | 231.3 | 228.9 | 226.8 | 224.8 | 222.7 | 220.8 | 218.8 |

| Annual percent changes | ||||||||||||

| National health expenditures | 10.3 | 12.8 | 15.2 | 15.3 | 13.2 | 11.7 | 12.9 | 13.6 | 14.0 | 12.5 | 10.0 | 12.5 |

| Private expenditures | 10.8 | 13.6 | 15.5 | 14.5 | 12.8 | 10.0 | 13.8 | 15.2 | 11.0 | 7.4 | 9.3 | 12.9 |

| Public expenditures | 9.5 | 11.7 | 15.0 | 16.5 | 13.7 | 14.0 | 11.6 | 11.5 | 18.5 | 20.8 | 11.2 | 11.8 |

| Federal expenditures | 10.1 | 11.7 | 17.5 | 16.5 | 13.3 | 13.5 | 11.4 | 14.8 | 19.8 | 22.9 | 10.0 | 12.6 |

| State and local expenditures | 8.2 | 11.6 | 9.7 | 16.5 | 14.3 | 15.1 | 11.8 | 5.2 | 16.1 | 17.0 | 13.3 | 10.3 |

| Gross national product | 7.7 | 3.8 | 12.4 | 8.8 | 11.7 | 12.8 | 11.7 | 10.9 | 8.0 | 8.1 | 11.8 | 10.1 |

| Population | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | .9 | .9 | .9 | .8 | .9 | 1.0 |

| National health expenditures in billions | $83.5 | $75.0 | $65.6 | $58.2 | $51.5 | $46.3 | $41.9 | $26.9 | $17.7 | $12.7 | $4.0 | $3.6 |

| Percent of the Gross National Product | 7.7 | 7.6 | 7.0 | 6.7 | 6.4 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 5.3 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 3.5 |

| Sources of funds in billions | ||||||||||||

| Private expenditures | $51.8 | $47.2 | $40.7 | $36.1 | $32.5 | $32.7 | $30.9 | $20.3 | $13.2 | $9.2 | $3.2 | $3.2 |

| Public expenditures | 31.7 | 27.8 | 24.9 | 22.1 | 19.0 | 13.6 | 11.0 | 6.6 | 4.6 | 3.4 | .8 | .5 |

| Federal expenditures | 20.3 | 17.7 | 16.1 | 14.1 | 11.9 | 7.4 | 5.5 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.6 | NA | NA |

| State and local expenditures | 11.4 | 10.1 | 8.9 | 8.0 | 7.0 | 6.1 | 5.5 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 1.8 | NA | NA |

| Per capita expenditures1 | $386 | $350 | $310 | $278 | $248 | $225 | $207 | $146 | $105 | $82 | $30 | $29 |

| Private expenditures | 239 | 221 | 192 | 172 | 157 | 159 | 152 | 110 | 78 | 60 | 24 | 25 |

| Public expenditures | 146 | 130 | 118 | 105 | 91 | 66 | 54 | 36 | 27 | 22 | 6 | 4 |

| Federal expenditures | 94 | 83 | 76 | 67 | 57 | 36 | 27 | 16 | 12 | 10 | NA | NA |

| State and local expenditures | 52 | 47 | 42 | 38 | 34 | 30 | 27 | 20 | 15 | 12 | NA | NA |

| Percent distribution of funds | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Private funds | 62.1 | 63.0 | 62.0 | 62.0 | 63.2 | 70.7 | 73.8 | 75.3 | 74.3 | 72.8 | 79.7 | 86.4 |

| Public funds | 37.9 | 37.0 | 38.0 | 38.0 | 36.8 | 29.3 | 26.2 | 24.7 | 25.7 | 27.2 | 20.3 | 13.6 |

| Federal funds | 24.3 | 23.5 | 24.5 | 24.3 | 23.1 | 16.1 | 13.2 | 11.2 | 11.3 | 12.8 | NA | NA |

| State and local funds | 13.6 | 13.5 | 13.5 | 13.7 | 13.7 | 13.2 | 13.0 | 13.5 | 14.4 | 14.4 | NA | NA |

| Addenda | ||||||||||||

| Gross national product (billions) | $1,077.6 | $992.7 | $944.0 | $873.4 | $799.6 | $756.0 | $691.0 | $506.5 | $400.0 | $286.5 | $100.0 | $103.4 |

| Population in millions | 216.6 | 214.0 | 211.7 | 209.6 | 207.6 | 205.6 | 203.0 | 183.8 | 168.4 | 154.7 | 134.6 | 123.7 |

| Annual percent changes | ||||||||||||

| National health expenditures | 11.4 | 14.2 | 12.7 | 13.1 | 11.2 | 10.3 | 9.3 | 8.7 | 7.0 | 12.2 | .8 | NA |

| Private expenditures | 9.8 | 16.0 | 12.7 | 11.1 | .6 | 5.7 | 8.8 | 9.0 | 7.4 | 11.2 | .1 | NA |

| Public expenditures | 14.1 | 11.3 | 12.8 | 16.6 | 39.8 | 23.4 | 10.6 | 7.8 | 5.8 | 15.5 | 4.6 | NA |

| Federal expenditures | 15.0 | 9.8 | 14.0 | 18.4 | 60.1 | 34.5 | 12.9 | 8.5 | 4.3 | .0 | NA | NA |

| State and local expenditures | 12.5 | 14.0 | 10.8 | 13.6 | 15.1 | 12.1 | 8.5 | 7.2 | 7.0 | 8.4 | NA | NA |

| Gross national product | 8.6 | 5.2 | 8.1 | 9.2 | 5.8 | 9.4 | 6.4 | 4.8 | 6.9 | 11.1 | −.3 | NA |

| Population | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.4 | .8 | NA |

Based on July 1 social security area population estimates.

NA = Data not available.

SOURCE: Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, Health Care Financing Administration.

The estimates presented in this article contain several revisions. Revisions to private health insurance benefit and premium levels and to the distribution of those benefits, discussed elsewhere in this issue (Arnett and Trapnell, 1984), have resulted in a substantially larger share of personal health care expenditures paid for by private health insurance. Estimates of total spending for hospital care have been revised upward as well, reflecting a more accurate method of converting fiscal year data to calendar year data. Minor changes have been made in the way public program benefit data are allocated to the types of services consumed. The net effect of these changes has been an overall decrease in the estimated level of direct patient payments, which is calculated as the remainder of total spending after all known third-party payments are deducted, and in the size of direct patient payments in each service category. Finally, official social security area population estimates have been used to calculate spending per capita. Because the figures in this report are based on provider and program aggregate data, per capita figures are an output of, rather than an input to, the estimates. The new population figures differ in concept from those used previously because of the addition of an estimate of the number of people missed by the census of population (Wade, 1984).

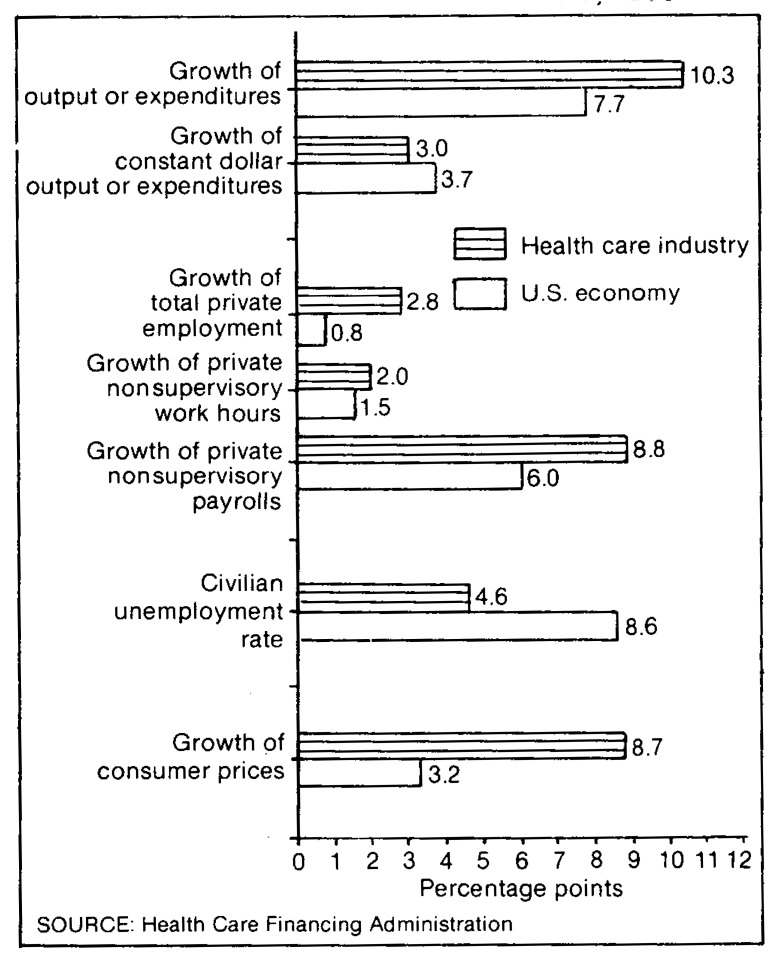

The health delivery industry is among the largest and strongest in the Nation (Figure 3). With over 7.2 million employees in 1983, it ranked second among industries — 1 in the United States in terms of employment or payroll. Output, measured by price-adjusted (“real”) personal health care expenditures, grew slightly less than real GNP, but for only the fourth time since 1966. The dollar value of output, including the effects of inflation, increased more rapidly than the GNP because consumer medical prices grew over 2½ times as fast as general consumer prices did. Employment in the private health industry grew three times as fast as that of the total private nonfarm economy, nonsupervisory work hours grew 1⅓ times as fast, and nonsupervisory payroll grew 1½ times as fast. The unemployment rate for health workers was lower than rates for comparably skilled workers in other areas, averaging somewhat more than half the rate of all experienced workers. All of these details point to a large and strong industry. When viewed over time, the data mentioned above described an industry that has been relatively insulated from the business cycle. Since 1972, nonsupervisory work hours in private health establishments have grown an average of 4.9 percent per year. Except for 1983, growth in a single year varied by no more than 1.7 percentage points from the average. In contrast, growth of non-supervisory work hours in all private nonagricultural establishments averaged 1.2 percent per year, varying in response to the business cycle by as much as 5.7 percentage points in a single year. A similar pattern can be seen in growth of nonsupervisory employment and average weekly earnings: Growth for the private health industry has been higher and has varied less than growth for the aggregate private nonfarm economy since 1972.

Figure 3. Measures of economic activity in the health care industry and in the United States as a whole, 1983.

There are a number of explanations for the difference in growth between health spending and the output of the general economy. First, it is generally accepted that, as an economy matures, consumers desire an increasing proportion of services, such as travel, health care, and dining. Second, economists theorize that industries with slower growing productivity may experience more rapid price inflation than industries with faster growing productivity. Health care, despite recent advances in technology, is still quite labor intensive; productivity growth is low, or even negative by some measures. Third, rapid development and dissemination of medical technology have expanded the treatment of disease to previously unattainable breadth and depth. This has resulted in more consumption of health care per capita, and it may also stimulate price inflation. Competition among providers in local medical markets to offer the latest technology can oversaturate the market and create excess capacity, thus raising costs. Fourth, the population of the United States gradually is aging. Although each age group is healthier than its counterparts in previous decades, one consequence of more older Americans is a need for more health care, because older people require more hospital and nursing-home care, for example, than younger people do (Waldo and Lazenby, 1984).

There are other reasons, financial in nature, for increases in the share of GNP going to health care. Two such reasons are the nature of third-party reimbursement and Government subsidies of health care spending.

Third-party reimbursement, as it has been practiced historically, leads to greater consumption of health care for two reasons. The first reason is that when a third party pays for a service, the act of consumption and the act of paying are separated in time and place: The consumer may not perceive the true cost of the service. Because the perceived price of consumption is lower than the actual price, consumers tend to use more health care services than they would otherwise use. Second, a great deal of third-party reimbursement is “cost based” or “retrospective” in nature. When the insurer pays a large proportion of costs, whatever those costs may be, there is little incentive for consumers or providers of care to be cost conscious. This feature reflects directly the original intent of health insurance, which was to guarantee access to health care regardless of cost. However, with consumption growing more rapidly than the supply of funds from which care is paid for, increasing pressure for reform of the cost-based aspect of third-party reimbursement has culminated in the conversion of part of Medicare to a prospective payment system.

Another important force acting on the financing of health care is the tax treatment of health insurance premiums and out-of-pocket payments for health care. Under current law, employer contributions for health insurance policies (more than three-quarters of the premiums earned by insurance companies in 1983) are excluded from employees' taxable income and from earnings subject to payroll taxes. In addition, until 1983 up to $150 of an employee's share of health insurance premiums could be deducted directly from taxable income. Today, only that part of health insurance premiums and other consumer medical expenses that exceeds 5 percent of adjusted gross income is tax deductible. The tax treatment of premiums alone cost the Federal Government $26 billion in foregone revenue in fiscal year 1983 (Congressional Budget Office, 1982). The tax-exempt status of health insurance premiums encourages employees, and does not discourage employers, to substitute more comprehensive insurance coverage for higher money wages. Many consumers view such expanded coverage as a “use-or-lose” benefit, and they tend to overconsume health care services, despite the fact that overconsumption raises the price of health insurance in the long run. The extensive third-party coverage of health care and the tax treatment of health care spending can be considered financial causes of rising health expenditures.

The broadest Government response to increasing health care expenditures, which comprised 11.9 percent of Federal outlays in 1983, was begun with the introduction of diagnosis-related hospital payments under Medicare, to take effect in stages between fiscal years 1984 and 1986. A hospital knows at the time of admission how much Medicare will pay for treatment of the patient. This form of prospective payment is expected to encourage providers of care to become more cost conscious. Evidence available at this time indicates that Medicare's prospective payment system has resulted in slower growth of spending for hospital care.

Goods and services purchased in 1983

“National health expenditures” are defined to include all spending for health care of individuals, the administrative costs of nonprofit and Government health programs, the net cost to enrollees of private health insurance, Government expenditures through public health programs, noncommercial health research, and construction of medical facilities. The definition excludes spending for environmental improvement and for subsidies and grants for health professional's education, categories which often are categorized with health in Federal budget documents.

National health expenditures are divided into two categories: Health services and supplies—expenditures related to current health—and research and construction of medical facilities—expenditures related to future health (Table 2). Health services and supplies, in turn, consist of personal health care (the direct provision of care), program administration and the net cost of insurance, and Government public health activities.

Table 2. National health expenditures, by type of expenditure: Selected years, 1929-83.

| Type of expenditure | 1983 | 1982 | 1981 | 1980 | 1979 | 1978 | 1977 | 1976 | 1975 | 1974 | 1973 | 1972 | 1971 | 1970 | 1969 | 1968 | 1967 | 1966 | 1965 | 1960 | 1955 | 1950 | 1940 | 1929 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total | $355.4 | $322.3 | $285.8 | $248.0 | $215.1 | $190.0 | $170.2 | $150.8 | $132.7 | $116.3 | $103.4 | $93.9 | $83.5 | $75.0 | $65.6 | $58.2 | $51.5 | $46.3 | $41.9 | $26.9 | $17.7 | $12.7 | $4.0 | $3.6 |

| Health services and supplies | 340.1 | 308.1 | 272.7 | 236.1 | 204.6 | 180.2 | 161.0 | 141.8 | 124.3 | 108.9 | 96.5 | 87.4 | 77.4 | 69.6 | 60.8 | 54.1 | 47.6 | 42.6 | 38.4 | 25.2 | 16.9 | 11.7 | 3.9 | 3.4 |

| Personal health care | 313.3 | 284.7 | 253.4 | 219.1 | 189.6 | 167.4 | 149.1 | 132.8 | 117.1 | 101.5 | 89.0 | 80.5 | 72.2 | 65.4 | 57.1 | 50.3 | 44.5 | 39.7 | 35.9 | 23.7 | 15.7 | 10.9 | 3.5 | 3.2 |

| Hospital care | 147.2 | 134.9 | 117.9 | 101.3 | 87.0 | 76.2 | 68.1 | 60.9 | 52.4 | 45.0 | 38.9 | 35.2 | 31.0 | 28.0 | 24.2 | 21.1 | 18.4 | 15.8 | 14.0 | 9.1 | 5.9 | 3.9 | 1.0 | .7 |

| Physicians' services | 69.0 | 61.8 | 54.8 | 46.8 | 40.2 | 35.8 | 31.9 | 27.6 | 24.9 | 21.2 | 19.1 | 17.2 | 15.9 | 14.3 | 12.6 | 11.1 | 10.1 | 9.2 | 8.5 | 5.7 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Dentists' services | 21.8 | 19.5 | 17.3 | 15.4 | 13.3 | 11.8 | 10.5 | 9.4 | 8.2 | 7.4 | 6.5 | 5.6 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | .4 | .5 |

| Other professional services | 8.0 | 7.1 | 6.4 | 5.6 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.0 | .9 | .6 | .4 | .2 | .3 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 23.7 | 21.8 | 20.5 | 18.5 | 17.1 | 15.4 | 14.1 | 13.0 | 11.9 | 11.0 | 10.1 | 9.3 | 8.6 | 8.0 | 7.1 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 3.7 | 2.4 | 1.7 | .6 | .6 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 6.2 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 | .8 | .6 | .5 | .2 | .1 |

| Nursing home care | 28.8 | 26.5 | 23.9 | 20.4 | 17.4 | 15.1 | 13.0 | 11.3 | 10.1 | 8.5 | 7.2 | 6.5 | 5.6 | 4.7 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 2.1 | .5 | .3 | .2 | .0 | .0 |

| Other health services | 8.5 | 7.6 | 7.0 | 5.9 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.1 | .7 | .5 | .1 | .1 |

| Expenses for prepayment and administration | 15.6 | 13.4 | 10.6 | 9.2 | 8.6 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 5.1 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 4.8 | 3.5 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.1 | .8 | .5 | .2 | .1 |

| Government public health activities | 11.2 | 10.0 | 8.6 | 7.7 | 6.4 | 5.3 | 4.3 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.0 | .9 | .8 | .8 | .4 | .4 | .4 | .2 | .1 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 15.3 | 14.2 | 13.2 | 11.9 | 10.4 | 9.8 | 9.2 | 9.0 | 8.4 | 7.5 | 6.8 | 6.6 | 6.1 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 4.1 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 1.7 | .9 | 1.0 | .1 | .2 |

| Research1 | 6.2 | 5.9 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.5 | .7 | .2 | .1 | .0 | .0 |

| Construction | 9.1 | 8.3 | 7.6 | 6.5 | 5.7 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 3.4 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | .7 | .8 | .1 | .2 |

Research and development expenditures of drug companies and other manufacturers and providers of medical equipment and supplies are excluded from “research expenditures,” but they are included in the expenditure class in which the product falls.

SOURCE: Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, Health Care Financing Administration.

Personal health care

A total of $313 billion was spent for personal health care in 1983 (Table 3), up 10.1 percent from the amount spent in 1982. In 1983, $1,286 was spent per capita for personal health care—an increase of 8.9 percent from the 1982 level.

Table 3. National health expenditures, by type of expenditure and source of funds: Calendar years 1981-83.

| Type of expenditure | Total | Private | Public | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Total | Consumer | Other 1 | Total | Federal | State and local | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Total | Direct | Insurance | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Amount in billions | |||||||||

| 1983 | |||||||||

| Total | $355.4 | $206.6 | $195.7 | $85.2 | $110.5 | $10.9 | $148.8 | $102.7 | $46.1 |

| Health services and supplies | 340.1 | 199.8 | 195.7 | 85.2 | 110.5 | 4.1 | 140.3 | 96.8 | 43.5 |

| Personal health care | 313.3 | 188.8 | 185.2 | 85.2 | 100.0 | 3.7 | 124.5 | 93.0 | 31.5 |

| Hospital care | 147.2 | 68.8 | 67.3 | 11.1 | 56.2 | 1.5 | 78.4 | 60.6 | 17.8 |

| Physicians' services | 69.0 | 49.7 | 49.7 | 19.6 | 30.1 | 3 | 19.3 | 15.6 | 3.7 |

| Dentists' services | 21.8 | 21.2 | 21.2 | 13.9 | 7.4 | --- | .6 | .3 | .3 |

| Other professional services | 8.0 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 3.3 | 2.1 | .1 | 2.5 | 1.9 | .5 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 23.7 | 21.6 | 21.6 | 18.4 | 3.2 | --- | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 6.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 4.5 | .7 | --- | 1.0 | .9 | .1 |

| Nursing home care | 28.8 | 14.9 | 14.7 | 14.4 | .3 | .2 | 14.0 | 8.1 | 5.9 |

| Other health services | 8.5 | 1.8 | --- | --- | --- | 1.8 | 6.6 | 4.5 | 2.1 |

| Program administration and net cost of insurance | 15.6 | 10.9 | 10.5 | --- | 10.5 | .5 | 4.6 | 2.6 | 2.0 |

| Government public health activities | 11.2 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 11.2 | 1.2 | 10.0 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 15.3 | 6.8 | --- | --- | --- | 6.8 | 8.4 | 5.9 | 2.6 |

| Research2 | 6.2 | .4 | --- | --- | --- | .4 | 5.8 | 5.2 | .6 |

| Construction | 9.1 | 6.5 | --- | --- | --- | 6.5 | 2.6 | .7 | 2.0 |

| 1982 | |||||||||

| Total | $322.3 | $186.5 | $176.6 | $77.2 | $99.3 | $9.9 | $135.8 | $93.3 | $42.6 |

| Health services and supplies | 308.1 | 180.4 | 176.6 | 77.2 | 99.3 | 3.8 | 127.8 | 87.6 | 40.1 |

| Personal health care | 284.7 | 171.4 | 168.0 | 77.2 | 90.8 | 3.4 | 113.4 | 84.0 | 29.4 |

| Hospital care | 134.9 | 63.2 | 61.8 | 10.3 | 51.4 | 1.4 | 71.8 | 55.3 | 16.4 |

| Physicians' services | 61.8 | 44.9 | 44.9 | 17.8 | 27.1 | 3 | 16.9 | 13.4 | 3.5 |

| Dentists' services | 19.5 | 18.9 | 18.9 | 12.4 | 6.5 | --- | .6 | .3 | .3 |

| Other professional services | 7.1 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 3.1 | 2.0 | .1 | 2.0 | 1.5 | .5 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 21.8 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 16.9 | 2.9 | --- | 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 5.5 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.1 | .6 | --- | .8 | .7 | .1 |

| Nursing home care | 26.5 | 13.1 | 12.9 | 12.7 | .2 | .2 | 13.4 | 7.7 | 5.7 |

| Other health services | 7.6 | 1.7 | --- | --- | --- | 1.7 | 5.9 | 4.1 | 1.8 |

| Program administration and net cost of insurance | 13.4 | 9.0 | 8.6 | --- | 8.6 | .4 | 4.4 | 2.4 | 1.9 |

| Government public health activities | 10.0 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 10.0 | 1.2 | 8.8 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 14.2 | 6.1 | --- | --- | --- | 6.1 | 8.1 | 5.6 | 2.5 |

| Research2 | 5.9 | .3 | --- | --- | --- | .3 | 5.5 | 5.0 | .6 |

| Construction | 8.3 | 5.8 | --- | --- | --- | 5.8 | 2.5 | .6 | 1.9 |

| 1981 | |||||||||

| Total | $285.8 | $164.2 | $155.6 | $70.8 | $84.8 | $8.6 | $121.7 | $83.5 | $38.1 |

| Health services and supplies | 272.7 | 159.0 | 155.6 | 70.8 | 84.8 | 3.4 | 113.7 | 78.1 | 35.6 |

| Personal health care | 253.4 | 152.6 | 149.5 | 70.8 | 78.8 | 3.0 | 100.8 | 74.3 | 26.5 |

| Hospital care | 117.9 | 55.2 | 53.9 | 9.2 | 44.7 | 1.3 | 62.7 | 48.6 | 14.1 |

| Physicians' services | 54.8 | 39.7 | 39.7 | 16.3 | 23.4 | 3 | 15.0 | 11.7 | 3.3 |

| Dentists' services | 17.3 | 16.6 | 16.6 | 10.9 | 5.8 | --- | .7 | .4 | .3 |

| Other professional services | 6.4 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 3.1 | 1.6 | .1 | 1.6 | 1.2 | .4 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 20.5 | 18.7 | 18.7 | 16.2 | 2.5 | --- | 1.9 | .9 | .9 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 5.6 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 4.5 | .5 | --- | .7 | 1.6 | .1 |

| Nursing home care | 23.9 | 11.1 | 10.9 | 10.7 | .2 | .2 | 12.8 | 7.2 | 5.7 |

| Other health services | 7.0 | 1.6 | --- | --- | --- | 1.6 | 5.4 | 3.7 | 1.7 |

| Program administration and net cost of insurance | 10.6 | 6.4 | 6.0 | --- | 6.0 | .4 | 4.2 | 2.5 | 1.7 |

| Government public health activities | 8.6 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 8.6 | 1.3 | 7.3 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 13.2 | 5.2 | --- | --- | --- | 5.2 | 8.0 | 5.4 | 2.6 |

| Research2 | 5.6 | .3 | --- | --- | --- | .3 | 5.3 | 4.8 | .5 |

| Construction | 7.6 | 4.8 | --- | --- | --- | 4.8 | 2.7 | .7 | 2.1 |

Spending by philanthropic organizations, industrial inplant health services, and privately financed construction.

Research and development expenditures of drug companies and other manufacturers and providers of medical equipment and supplies are excluded from “research expenditures,” but they are included in the expenditure class in which the product falls.

Less than $50 million.

SOURCE: Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, Health Care Financing Administration.

Third parties account for almost three-quarters of spending for personal health care. Private health insurance benefits amounted to $100 billion in 1983, and other private third-party benefits (philanthropy and industrial inplant health programs) amounted to $4 billion. The Federal Government expended $93 billion, most of it through Medicare and Medicaid; and State and local governments spent $32 billion, about half of which was channeled through Medicaid.

Although price inflation has been moderating, it still accounts for most of the growth in spending for personal health care. As shown in Figure 4, 70 percent of the increase in spending between 1982 and 1983 was due to price inflation; another 11 percent was due to population growth. The remainder was due to a variety of influences, among them the aging of the population, increased consumption per capita, and changes in the types of services provided.

Figure 4. Factors in the increase of personal health care expenditures, 1982-1983.

Personal health care consists of a number of different goods and services.

Physicians' services

Physicians are the most influential group in determining the size and shape of the health care sector. They affect personal health care expenditures much more than is indicated by the 22-percent share of spending devoted to their services. By some estimates, they influence 70 to 80 percent of health care spending (Blumberg, 1979; Somers and Somers, 1977). Physicians play a dominant role in determining who will be hospitalized and what type and quantity of services the hospital patient will receive; expenditures for prescription drugs are influenced similarly.

Expenditures for physicians' services reached $69 billion in 1983—an increase of 11.7 percent from the previous year. This spending accounted for 22.0 percent of personal health care expenditures and for 19.4 percent of all national health expenditures.

Third parties play a large role in the financing of physicians' services. The Federal Government financed slightly less than a quarter of such spending, 23 percent, and private health insurance benefits financed 44 percent of the total. State and local governments paid for 5 percent of the total; and the balance, some 28 percent, is assumed to have been paid by patients or their families.

Price inflation was a significant contributor to the growth of expenditures for physicians' services. Measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) physicians' fees rose 7.7 percent in 1983, compared with an increase of 3.2 percent in the CPI for all items.

Existing data convey differing implications concerning growth in the use of physicians' services. Physician visit data, available through 1981, indicate a slight long-run decline in visits per capita (National Center for Health Statistics: data from the Health Interview Survey). The number of surgical operations performed in community hospitals rose very little—0.5 percent in 1983, half the rate of growth of the population—and the number of inpatient days—presumably correlated with physician inpatient contacts—dropped 2.5 percent (American Hospital Association: data from the National Hospital Panel Survey). On the other hand, the decline in inpatient contacts probably has been offset by an increase in office-based contacts. As evidence, nonsupervisory work hours in offices of physicians and surgeons rose 5.7 percent in 1983 (Bureau of Labor Statistics: data from the Establishment Survey), data consistent with greater office activity. Part of the work hours growth may be due to the activity of physician-operated freestanding emergency and outpatient surgery centers; but the data suggest, nonetheless, a strong increase in physician contact outside the hospital.

In the National Health Accounts—the framework within which these estimates fit—expenditures for physician's services encompass the cost of all services and supplies provided in physicians' offices, the cost for services of private practitioners in hospitals and other institutions, and the cost of diagnostic work performed in independent clinical laboratories. The salaries of staff physicians are counted with expenditures for the services of the employing institution.

Hospital care

Expenditures for hospital care in 1983 were $147 billion—an increase of 9.1 percent from 1982. Hospital care accounted for 47.0 percent of the total personal health care expenditures and for 41.4 percent of the national health expenditures. The Federal Government paid for 41.1 percent of hospital care in 1983, private health insurance paid for 38.2 percent, and State and local governments paid for 12.1 percent. Thus, patients paid just 7.5 percent of the cost of hospital care directly.

Data on use of community hospitals (which account for over 80 percent of hospital spending) show a shift from inpatient to outpatient settings. Admissions were 0.5 percent lower in 1983 than in 1982, and inpatient days dropped 2.5 percent. By contrast, clinic visits rose 6.1 percent from 1982 to 1933, and other nonemergency outpatient visits increased 4.1 percent (American Hospital Association: data from the National Hospital Panel Survey).

Three-quarters of the increase in hospital spending between 1982 and 1983 was due to price inflation. General (economy-wide) inflation measured by the gross national product fixed-weight price index accounted for half of the increase; hospital price inflation over and above the general rate accounted for another quarter. Hospital-specific inflation measured by Health Care Financing Administration's National Hospital Input Price Index (Freeland, Anderson, and Schendler, 1979) dropped to 6.4 percent in 1983, the lowest rate in the last 10 years but still higher than the general rate of inflation.

The remaining quarter of the increase in hospital spending is attributable to population growth and to residual factors. The latter category—which includes such effects as the aging of the population, changes in the mix of hospital services provided, and changes in the amounts and mix of goods and services used to provide those services—accounted for 16 percent of the growth in spending.

In the National Health Accounts, hospital care includes all inpatient and outpatient care in public and private hospitals and all services and supplies provided by hospitals. Except for the services of hospital staff physicians, expenditures for physician care provided in hospitals are included in the physician category described above.

Nursing home care

In 1983, $29 billion was spent for nursing home care—an increase of 8.8 percent from the previous year. Such care amounted to 8.1 percent of total health spending and to 9.2 percent of personal health care expenditures.

In the National Health Accounts, nursing home services are those provided in skilled nursing facilities, in intermediate care facilities, and in personal care homes that provide nursing care. In addition, a majority of the care for mentally retarded Medicaid recipients provided in what are designated “intermediate care facilities for the mentally retarded” (ICFMR) is included as nursing home care. Nursing type care provided in hospitals (including ICFMR care) is included with expenditures for hospital care.

Part of the growth in spending for nursing home care is due to the rapid expansion in intermediate care facilities for the mentally retarded, a Medicaid benefit first offered in 1972. Currently, about $2.4 billion (60 percent of the total expenditures for ICFMR) is spent in nursing homes. ICFMR growth has been very rapid, averaging almost 40 percent per year since its inception. Despite its relatively small size and a slowing of growth in recent years, it continues to raise the growth rate of the total nursing home aggregate.

Growth in spending for nursing home care other than ICFMR has slowed considerably in recent years. Part of this slowdown is due to a deceleration of prices paid by nursing home: Health Care Financing Administration's National Nursing Home Input Price Index rose 5.8 percent in 1983, the smallest increase in the last 10 years. The share of nursing home care financed by public programs has declined since 1979, from 56 percent to 48 percent. Almost all of that decline was in Medicaid and Medicare shares. Reduced utilization of nursing home care by Medicaid and Medicare patients has been occurring. The explanation for this reduction is twofold. First, the shortage of nursing home beds in some areas allows nursing homes to selectively admit patients (Feder and Scanlon, 1981). Higher-paying private patients will be admitted before Medicaid or Medicare patients. This results in a large number of days spent in hospitals while patients await discharge to nursing homes. Second, the shortage of beds may be purposely induced in some States in order to minimize Medicaid expenditures. Tactics used by States include tightening of certificate of need requirements and keeping reimbursement rates low (Weissert, et al., 1984). Potential investors in the nursing home business may be discouraged by the low profitability of the industry, due primarily to these reimbursement policies. However, despite the reduction in spending by the public sector, and even excluding the effects of price inflation, constant dollar expenditures grew 2.9 percent in 1983; this was about the same rate of growth as for the population aged 75 years or over.

Drugs and medical sundries

This category, for which $24 billion was spent in 1983 (accounting for 7.6 percent of personal health care expenditures), includes spending for prescription drugs, over-the-counter drugs, and medical sundries dispensed through retail channels. Expenditures for drugs purchased or dispensed by hospitals, physicians, nursing homes, and other institutions and practitioners are counted elsewhere.

Spending for drugs and sundries is financed mostly by consumers directly: Of the $24 billion spent in 1983, $18 billion (or three-quarters of the total) was financed that way. Private health insurance paid approximately $3 billion, and Federal and State or local governments each paid about $1 billion.

Drug therapy constitutes a significant factor in the treatment of illness. An estimated 58 percent of the noninstitutionalized population received at least one prescription for medication in 1977 (Kasper, 1982). About 57 percent of all dollars spent for drugs and medical sundries is estimated to be spent for prescription drugs alone, and 31 percent is estimated to be spent for over-the-counter drug products.

Historically, spending for drugs and sundries has increased at a rate significantly below that of other health care goods and services. Over the last 10 years, for example, such spending increased 9.0 percent per year, compared with an annual growth of 13.4 percent in total personal health care spending.

Part of this phenomenon is due to a relatively low rate of price inflation for drugs. From 1964 to 1968, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for prescription drugs actually declined, and it was not until 1974 that it recovered its 1964 level. From 1974 to 1980, the CPI for prescription drugs rose 7.0 percent per year, and from 1980 to 1983 it rose 11.4 percent annually.

Another reason drug spending has grown more slowly than spending for other forms of health care is that the amount of third-party coverage is much lower in this area. Private health insurance covered 13.6 percent of drug and sundry expenditures in 1983, and Government covered another 9 percent. These figures are far less than the 31.9 and 39.7 percent, respectively, of total personal health care spending financed by private insurance and by Government. One consequence of this greater reliance upon direct consumer financing is that spending varies with consumer purchasing power. Price-adjusted spending for drugs and sundries declined during the recent recession, and it has not yet returned to its 1979 level.

Other personal health care goods and services

Expenditures for all other types of personal health care goods and services were $44.5 billion in 1983—an increase of 12.1 percent. That spending amounted to 14 percent of all personal health care expenditures and to 13 percent of national health expenditures. Almost equal proportions of this group of services were financed through Government programs (24 percent) and private health insurance (23 percent) in 1983; consumers paid for 49 percent directly. Almost half of the expenditures in this category were for dentist's services, but the category also includes spending for services of other health professionals (including most home health agencies), for eyeglasses and orthopedic appliances, and for other health services (including the provision of care in industrial settings and school health). Growth of this composite component was influenced significantly by the growth of spending for dentists' services and, to some extent, by the growth of spending for other professional services.

Spending for dentists' services, which reached $22 billion in 1983, increased not only because of price inflation but also because of recent increases in the extent of third-party dental coverage. Traditionally, use of dental services fluctuated with the business cycle. However, despite a 12-percent increase in the CPI for dental care in 1980 and the recent economic recession, “price-deflated” expenditures per capita for dental services increased 4 percent per year between 1978 and 1983. This departure from tradition reflects the increased extent of third-party dental coverage. For example, private health insurance, which covered 1 percent of dental services in 1965, paid for one-third of all services received in 1983.

Other health services and supplies

The cost of operating third-party programs in 1983 rose 16.6 percent, to $15.6 billion. This estimate includes $4.6 billion in administrative expenses for those public programs that identified administrative expenses. Administrative costs associated with operating the Medicare and Medicaid programs amounted to $3.1 billion in 1983. Administrative expenses also included a small amount estimated to be the fundraising and administrative expenses of philanthropic organizations. The largest part of the component is the net cost of private health insurance, the difference between earned premiums and incurred claims. Estimated at $10.5 billion for 1983, net cost reflects administrative expenses, additions to loss reserves, and profits or losses of Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans, mutual and stock carriers, and prepaid and self-insured health plans.

Public health activities of various levels of Government amounted to $11.2 billion in 1983. Public health activities are those functions carried out by Federal, State, and local governments to support community health, in contrast with care delivered to individuals. Federal expenditures of $1.2 billion included the services of the Centers for Disease Control and the Food and Drug Administration, as well as grants to States.

Other National health expenditures

National health expenditures devoted to nonprofit research and to construction of medical facilities were $15 billion in 1983, an amount equal to 4.3 percent of total health spending.

Expenditures for noncommercial health care research and development were $6.2 billion in 1983. The Federal Government financed by far the largest amount for research, with funds totaling $5.2 billion, most of which was spent by the National Institutes of Health. Expenditures by State and local governments, exclusive of Federal grants, were $588 million, and private philanthropy funded an even smaller amount.

The $6.2 billion in spending for research in the National Health Accounts excludes research performed by drug companies and by other manufacturers and suppliers of health care goods and services, estimated to be $4 billion in 1983. As this type of research is treated as a business expense and is financed through sales of goods or services, its dollar value is implicitly included in personal health care expenditures; to include it again in this line would result in double counting.

Of the $9.1 billion spent on construction of medical facilities in 1983, 29 percent was funded from public sources. Grants from philanthropic organizations funded 4 percent, and the remainder came from internal funds or from the private capital market. This estimate does not include spending for capital equipment, because there is no source of data to yield a reliable, consistent time series of data on spending for equipment.

Financing health care

Health care can be financed directly by the consumer through out-of-pocket payments. Alternatively, consumers can reduce the risk of incurring major medical costs by acquiring third-party coverage. The third party may act as the financial intermediary between the health provider and the consumer of health care, or may reimburse the consumer for the cost of care, or may hire the provider of care. In any case, an insured consumer pays less or none of the cost of care at the time of service.

The health care market differs from the perfect market for goods and services depicted in standard economic theory. First, it is dominated by third-party payers: In 1983, 73 percent of personal health care expenditures were made by the Government or by private health insurance. Second, unlike most other markets, the consumers of health care lack full information when decisions are made to purchase health care. For example, hospital admission is usually made on the decision of a seller of health care (a physician) rather than by the consumer of hospital services (the patient), or by the purchaser of the service (the Government, private health insurers, or the patient). Whether the patient with complete information would choose the same types and quantities of care is an issue yet to be answered empirically. To the extent that the patient would not make the same choices, the industry plays a role in determining its “sales.”

A corollary to these theories is that the absence of the “usual” market forces that limit health care expenditures may generate political (nonmarket) bargaining between payers and providers. Where the Government is the payer, this takes the form of regulations or ratesetting (Feder and Spitz, 1980). In practice, those parts of the health care sector for which Government pays the highest proportion of costs (hospitals, for example) are also parts of the sector with the greatest degree of cost regulation.

Third-party financing

Unlike other goods or services for which the consumer pays the provider directly, health care payments often are handled by a financial agent—a “third party.” The details of the payment method may vary: The consumer may pay the provider and apply for reimbursement from the third party, or the provider may bill the third party directly, or the provider may be employed by the third party (as in the case of U.S. Department of Defense hospitals or industrial inplant services, for example). In the case of Medicare, institutional providers bill “financial intermediaries”—private health insurers acting as agents for the Federal Government—and physicians may bill either the financial intermediary or the patient.

The existing third-party coverage of health care may have contributed to a healthier population, but it has exacted a price as well. Insurance has increased access to care, resulting in treatment of patients who had been shut out of the orthodox medical market by price considerations. However, the historical structure of insurance benefits encourages use of inpatient rather than outpatient facilities, and it encourages overuse of tests and procedures rather than underuse. The financial incentives embedded in traditional reimbursement structures may encourage effective medical care, but not necessarily at the lowest cost.

Private health insurance

Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans, commercial insurance companies, and prepaid and self-insured plans paid an estimated $100 billion in medical benefits in 1983, an amount equal to 31.9 percent of personal health care expenditures. These benefit payments were 10.2 percent higher than the 1982 payments of $91 billion. Insurers received an estimated $110 billion in premiums, 56.5 percent of all consumer spending for health, resulting in a net cost to enrollees over $10.5 billion. The 1982 premiums and net cost were $99 billion and $8.6 billion, respectively.

The 1982 levels for insurance are substantially higher than those previously published (Table 4). The major source of revision stems from a new treatment of self-insured and insurance company data. New information, particularly new preliminary estimates of third-party administrator business, has also been incorporated. These revisions are discussed in detail elsewhere in this issue (Arnett and Trapnell, 1984).

Table 4. Revisions to private health insurance estimates.

| Year | Current estimates | Previously published | Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Premiums | Benefits | Premiums | Benefits | Premiums | Benefits | |

|

| ||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||

| 1965 | $10.0 | $8.7 | $10.0 | $8.7 | $ 0.0 | $0.0 |

| 1970 | 16.9 | 15.3 | 17.1 | 15.6 | −.2 | −.3 |

| 1975 | 33.2 | 31.2 | 32.4 | 30.1 | .8 | 1.1 |

| 1976 | 40.4 | 37.6 | 38.2 | 35.5 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| 1977 | 48.0 | 43.0 | 44.6 | 40.0 | 3.4 | 3.0 |

| 1978 | 53.6 | 49.1 | 49.7 | 45.0 | 3.9 | 4.1 |

| 1979 | 62.0 | 56.9 | 55.9 | 50.2 | 6.1 | 6.7 |

| 1980 | 72.5 | 67.3 | 63.6 | 57.0 | 8.9 | 10.3 |

| 1981 | 84.8 | 78.8 | 73.2 | 66.8 | 11.6 | 12.0 |

| 1982 | 99.3 | 90.8 | 84.2 | 76.6 | 15.1 | 14.2 |

| 1983 | 110.5 | 100.0 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

SOURCE: Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, Health Care Financing Administration.

The size of the private health insurance industry has been growing, reflecting the perceived desire for its services. By 1983, 53 percent of private expenditures for personal health care—the amount not covered by public programs—was reimbursed by private insurance. In 1982, three-quarters of the U.S. population was covered by private health insurance for hospital care, compared with one-half in 1950. The relatively rapid rate of growth of insurance premiums—14 percent per year since 1950, compared with an increase of 11 percent in total personal health care expenditures—reflects the desire for the prepayment and risk-sharing offered by private health insurance. Only a handful of the population has the financial resources to pay directly and fully for the medical costs of a major illness (Falk, et al., 1933).

Self-insured plans have been growing during the latter half of the seventies (Table 5). This growth has been stimulated by tax and other financial advantages to employers. Insurance companies have also contributed to this growth by providing administrative and stop-loss services that aid and protect self-insured plans. The prepaid plans category, comprised of health maintenance organizations and single-service plans, has also grown significantly in recent years, but it still remains a small part of overall insurance.

Table 5. Private health insurance benefits and percent distribution by type of insurer: United States, selected years 1965-83 (Amount in billions).

| Year | Total private health insurance1 | Insurance companies2 | Blue Cross and Blue Shield | Self-insured plans3 | Prepaid plans4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Amount | Percent | Amount | Percent | Amount | Percent | Amount | Percent | Amount | Percent | |

| 1965 | $ 8.7 | 100.0 | $4.2 | 48.4 | $3.9 | 45.2 | $.3 | 3.9 | $.2 | 2.6 |

| 1970 | 15.3 | 100.0 | 7.1 | 46.4 | 7.0 | 46.1 | .7 | 4.3 | .5 | 3.2 |

| 1975 | 31.2 | 100.0 | 12.8 | 41.1 | 14.2 | 45.5 | 3.0 | 9.6 | 1.2 | 3.8 |

| 1976 | 37.6 | 100.0 | 15.0 | 39.8 | 16.2 | 43.2 | 4.9 | 13.2 | 1.5 | 3.9 |

| 1977 | 43.0 | 100.0 | 16.4 | 38.3 | 17.8 | 41.5 | 6.8 | 15.9 | 1.9 | 4.3 |

| 1978 | 49.1 | 100.0 | 19.1 | 38.8 | 19.5 | 39.7 | 8.3 | 16.9 | 2.3 | 4.6 |

| 1979 | 56.9 | 100.0 | 21.8 | 38.4 | 21.7 | 38.2 | 10.5 | 18.5 | 2.8 | 5.0 |

| 1980 | 67.3 | 100.0 | 25.6 | 38.0 | 25.5 | 37.8 | 12.7 | 18.8 | 4.4 | 5.6 |

| 1981 | 78.8 | 100.0 | 30.6 | 38.8 | 29.2 | 37.1 | 14.5 | 18.5 | 4.4 | 5.6 |

| 1982 | 90.8 | 100.0 | 37.1 | 40.9 | 32.1 | 35.4 | 16.2 | 17.8 | 5.3 | 5.9 |

| 1983 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 41.3 | 41.3 | 35.2 | 35.2 | 17.4 | 17.4 | 6.1 | 6.1 |

Detail may not add to totals because of rounding.

Includes minimum premium plans (MPP).

Includes administrative service only (ASO) plans.

Includes health maintenance organizations and other prepaid plans such as dental and vision.

SOURCE: Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, Health Care Financing Administration.

The advent of Medicare and Medicaid slowed the growth of the private health insurance share of personal health care expenditures. Private health insurance share of spending doubled between 1950 and 1965, reaching 24 percent (Table 6). Since 1967, this share has grown gradually, increasing to 32 percent in 1983. The change results from an increased breadth of services covered and an increasing depth of coverage in hospital and physician services, as well as increasing enrollment through 1977. By 1983, private health insurance was paying $100 billion in health benefits.

Table 6. Aggregate and per capita amount and percent distribution of personal health care expenditures, by source of funds: Selected years 1929-83.

| Year | Total | Patient direct payments | All third parties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Total | Private | Public | ||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| Health Insurance | Other | Total | Federal | State and local | ||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||

| 1929 | $3.2 | $2.8 | $.4 | 1 | $.1 | $.3 | $.1 | $.2 |

| 1935 | 2.7 | 2.2 | .5 | 1 | .1 | .4 | .1 | .3 |

| 1940 | 3.5 | 2.9 | .7 | 1 | .1 | .6 | .1 | .4 |

| 1950 | 10.9 | 7.1 | 3.8 | $.9 | .3 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| 1955 | 15.7 | 9.1 | 6.6 | 2.5 | .4 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 2.0 |

| 1960 | 23.7 | 13.0 | 10.7 | 5.0 | .5 | 5.2 | 2.2 | 3.0 |

| 1965 | 35.9 | 18.5 | 17.3 | 8.7 | .8 | 7.9 | 3.6 | 4.3 |

| 1966 | 39.7 | 19.6 | 20.0 | 9.1 | .8 | 10.1 | 5.3 | 4.9 |

| 1967 | 44.5 | 19.0 | 25.5 | 9.6 | .8 | 15.1 | 9.5 | 5.6 |

| 1968 | 50.3 | 20.7 | 29.6 | 10.9 | .9 | 17.8 | 11.4 | 6.4 |

| 1969 | 57.1 | 23.0 | 34.0 | 12.9 | .9 | 20.2 | 13.2 | 7.0 |

| 1970 | 65.4 | 26.5 | 38.9 | 15.3 | 1.1 | 22.4 | 14.5 | 7.9 |

| 1971 | 72.2 | 28.1 | 44.1 | 17.2 | 1.3 | 25.6 | 16.8 | 8.8 |

| 1972 | 80.5 | 30.6 | 49.9 | 19.0 | 2.0 | 28.8 | 18.9 | 9.9 |

| 1973 | 89.0 | 33.3 | 55.7 | 21.4 | 2.2 | 32.1 | 21.1 | 11.1 |

| 1974 | 101.5 | 35.8 | 65.6 | 25.1 | 1.5 | 39.0 | 26.3 | 12.7 |

| 1975 | 117.1 | 38.0 | 79.1 | 31.2 | 1.6 | 46.3 | 31.4 | 14.9 |

| 1976 | 132.8 | 42.0 | 90.8 | 37.6 | 1.8 | 51.4 | 36.1 | 15.3 |

| 1977 | 149.1 | 46.4 | 102.7 | 43.0 | 2.0 | 57.8 | 41.0 | 16.8 |

| 1978 | 167.4 | 50.6 | 116.7 | 49.1 | 2.1 | 65.6 | 46.4 | 19.2 |

| 1979 | 189.6 | 55.8 | 133.8 | 56.9 | 2.3 | 74.6 | 53.3 | 21.2 |

| 1980 | 219.1 | 62.5 | 156.7 | 67.3 | 2.6 | 86.7 | 62.5 | 24.2 |

| 1981 | 253.4 | 70.8 | 182.6 | 78.8 | 3.0 | 100.8 | 74.3 | 26.5 |

| 1982 | 284.7 | 77.2 | 207.5 | 90.8 | 3.4 | 113.4 | 84.0 | 29.4 |

| 1983 | 313.3 | 85.2 | 228.1 | 100.0 | 3.7 | 124.5 | 93.0 | 31.5 |

| Per capita amount2 | ||||||||

| 1929 | $26 | $23 | $3 | 1 | $1 | $2 | $1 | $2 |

| 1935 | 21 | 17 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| 1940 | 26 | 21 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| 1950 | 70 | 46 | 24 | $6 | 2 | 16 | 7 | 8 |

| 1955 | 93 | 54 | 39 | 15 | 3 | 21 | 10 | 12 |

| 1960 | 129 | 71 | 58 | 27 | 3 | 28 | 12 | 16 |

| 1965 | 177 | 91 | 85 | 43 | 4 | 39 | 18 | 21 |

| 1966 | 193 | 95 | 98 | 44 | 4 | 49 | 26 | 24 |

| 1967 | 214 | 91 | 123 | 46 | 4 | 73 | 46 | 27 |

| 1968 | 240 | 99 | 141 | 52 | 4 | 85 | 54 | 30 |

| 1969 | 270 | 109 | 161 | 61 | 4 | 95 | 62 | 33 |

| 1970 | 305 | 124 | 182 | 72 | 5 | 105 | 68 | 37 |

| 1971 | 333 | 130 | 203 | 79 | 6 | 118 | 77 | 41 |

| 1972 | 368 | 140 | 228 | 87 | 9 | 132 | 87 | 45 |

| 1973 | 403 | 151 | 252 | 97 | 10 | 146 | 95 | 50 |

| 1974 | 456 | 161 | 295 | 113 | 7 | 175 | 118 | 57 |

| 1975 | 521 | 169 | 352 | 139 | 7 | 206 | 140 | 66 |

| 1976 | 586 | 185 | 400 | 166 | 8 | 227 | 159 | 67 |

| 1977 | 651 | 203 | 449 | 188 | 9 | 253 | 179 | 74 |

| 1978 | 724 | 219 | 505 | 212 | 9 | 283 | 201 | 83 |

| 1979 | 811 | 239 | 572 | 243 | 10 | 319 | 228 | 91 |

| 1980 | 927 | 264 | 663 | 285 | 11 | 367 | 265 | 102 |

| 1981 | 1062 | 297 | 765 | 330 | 13 | 422 | 311 | 111 |

| 1982 | 1181 | 320 | 861 | 377 | 14 | 470 | 348 | 122 |

| 1983 | 1286 | 350 | 936 | 410 | 15 | 511 | 382 | 129 |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||

| 1929 | 100.0 | 88.4 | 11.6 | 1 | 2.6 | 9.0 | 2.7 | 6.3 |

| 1935 | 100.0 | 82.4 | 17.6 | 1 | 2.8 | 14.7 | 3.4 | 11.3 |

| 1940 | 100.0 | 81.3 | 18.7 | 1 | 2.6 | 16.1 | 4.1 | 12.0 |

| 1950 | 100.0 | 65.5 | 34.5 | 9.1 | 2.9 | 22.4 | 10.4 | 12.0 |

| 1955 | 100.0 | 58.1 | 41.9 | 16.1 | 2.8 | 23.0 | 10.5 | 12.5 |

| 1960 | 100.0 | 54.9 | 45.1 | 21.1 | 2.3 | 21.8 | 9.3 | 12.5 |

| 1965 | 100.0 | 51.6 | 48.4 | 24.2 | 2.2 | 22.0 | 10.1 | 11.9 |

| 1966 | 100.0 | 49.5 | 50.5 | 22.9 | 2.1 | 25.5 | 13.2 | 12.3 |

| 1967 | 100.0 | 42.6 | 57.4 | 21.6 | 1.9 | 33.9 | 21.3 | 12.6 |

| 1968 | 100.0 | 41.2 | 58.8 | 21.7 | 1.8 | 35.3 | 22.6 | 12.7 |

| 1969 | 100.0 | 40.4 | 59.6 | 22.7 | 1.6 | 35.3 | 23.1 | 12.3 |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 40.5 | 59.5 | 23.4 | 1.7 | 34.3 | 22.2 | 12.1 |

| 1971 | 100.0 | 38.9 | 61.1 | 23.8 | 1.8 | 35.5 | 23.2 | 12.3 |

| 1972 | 100.0 | 38.0 | 62.0 | 23.6 | 2.5 | 35.8 | 23.5 | 12.3 |

| 1973 | 100.0 | 37.4 | 62.6 | 24.0 | 2.5 | 36.1 | 23.7 | 12.4 |

| 1974 | 100.0 | 35.3 | 64.7 | 24.8 | 1.5 | 38.4 | 25.9 | 12.6 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 32.5 | 67.5 | 26.7 | 1.3 | 39.5 | 26.8 | 12.7 |

| 1976 | 100.0 | 31.6 | 68.4 | 28.3 | 1.4 | 38.7 | 27.2 | 11.5 |

| 1977 | 100.0 | 31.1 | 68.9 | 28.8 | 1.3 | 38.8 | 27.5 | 11.3 |

| 1978 | 100.0 | 30.3 | 69.7 | 29.3 | 1.2 | 39.2 | 27.7 | 11.5 |

| 1979 | 100.0 | 29.4 | 70.6 | 30.0 | 1.2 | 39.3 | 28.1 | 11.2 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 28.5 | 71.5 | 30.7 | 1.2 | 39.6 | 28.5 | 11.0 |

| 1981 | 100.0 | 27.9 | 72.1 | 31.1 | 1.2 | 39.8 | 29.3 | 10.4 |

| 1982 | 100.0 | 27.1 | 72.9 | 31.9 | 1.2 | 39.8 | 29.5 | 10.3 |

| 1983 | 100.0 | 27.2 | 72.8 | 31.9 | 1.2 | 39.7 | 29.7 | 10.1 |

Included with direct payments; separate data not available.

Based on July 1 social security area population estimates.

SOURCE: Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, Health Care Financing Administration.

A large proportion of spending for hospital care and physicians' services is paid by private health insurance. In 1960, private insurance paid for 36 percent of hospital care, the first type of service to be covered extensively; that share reached 41 percent by 1965 (Table 7). When Medicare and Medicaid were established in 1966, hospital care spending increased dramatically, and the portion paid by private insurance, while growing in dollar terms, dropped to less than 34 percent by 1967. Since 1967, the insurance share of hospital financing has grown to 38 percent because consumers have sought more depth in their hospital coverage. In 1967, patient direct payments financed 10.6 percent of all hospital expenditures. By 1983, however, these payments had declined to 7.5 percent because private insurance picked up an increasing proportion of the expenditures. Extension of coverage beyond surgical procedures in recent years has led to a higher share of physicians' services being reimbursed by private insurance. This share rose from 31 percent in 1965 to 44 percent in 1983 (Table 8).

Table 7. Aggregate and per capita amount and percent distribution of expenditures for hospital care, by source of funds: Selected years 1950-83.

| Year | Total | Patient direct payments | All third parties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Total | Private | Public | ||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| Health insurance | Other | Total | Federal | State and local | ||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||

| 1950 | $ 3.9 | $ 1.2 | $ 2.7 | $ .7 | $ .1 | $ 1.9 | 1 | 1 |

| 1955 | 5.9 | 1.3 | 4.6 | 1.7 | .2 | 2.7 | 1 | 1 |

| 1960 | 9.1 | 1.8 | 7.3 | 3.3 | .2 | 3.8 | 1 | 1 |

| 1965 | 14.0 | 2.3 | 11.6 | 5.7 | .3 | 5.6 | $ 2.4 | $ 3.1 |

| 1966 | 15.8 | 2.6 | 13.2 | 6.0 | .3 | 6.9 | 3.5 | 3.4 |

| 1967 | 18.4 | 1.9 | 16.4 | 6.2 | .3 | 10.0 | 6.3 | 3.7 |

| 1968 | 21.1 | 2.3 | 18.8 | 7.0 | .4 | 11.5 | 7.3 | 4.1 |

| 1969 | 24.2 | 2.6 | 21.6 | 8.2 | .3 | 13.1 | 8.5 | 4.6 |

| 1970 | 28.0 | 3.2 | 24.8 | 9.7 | .4 | 14.7 | 9.5 | 5.1 |

| 1971 | 31.0 | 3.1 | 27.9 | 10.9 | .5 | 16.5 | 10.9 | 5.6 |

| 1972 | 35.2 | 3.5 | 31.7 | 11.8 | 1.2 | 18.6 | 12.4 | 6.2 |

| 1973 | 38.9 | 3.9 | 35.0 | 13.1 | 1.4 | 20.6 | 13.7 | 6.9 |

| 1974 | 45.0 | 4.6 | 40.5 | 15.1 | .6 | 24.7 | 17.0 | 7.7 |

| 1975 | 52.4 | 4.1 | 48.3 | 18.8 | .6 | 28.9 | 20.2 | 8.8 |

| 1976 | 60.9 | 5.1 | 55.7 | 22.5 | .7 | 32.5 | 23.7 | 8.8 |

| 1977 | 68.1 | 5.4 | 62.8 | 25.5 | .7 | 36.6 | 27.0 | 9.6 |

| 1978 | 76.2 | 5.5 | 70.7 | 28.6 | .8 | 41.3 | 30.4 | 10.9 |

| 1979 | 87.0 | 6.4 | 80.6 | 33.0 | .9 | 46.7 | 34.9 | 11.8 |

| 1980 | 101.3 | 7.5 | 93.8 | 38.6 | 1.0 | 54.2 | 41.1 | 13.1 |

| 1981 | 117.9 | 9.2 | 108.7 | 44.7 | 1.3 | 62.7 | 48.6 | 14.1 |

| 1982 | 134.9 | 10.3 | 124.6 | 51.4 | 1.4 | 71.8 | 55.3 | 16.4 |

| 1983 | 147.2 | 11.1 | 136.1 | 56.2 | 1.5 | 78.4 | 60.6 | 17.8 |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||

| 1950 | 100.0 | 29.9 | 70.1 | 17.7 | 3.5 | 48.9 | 1 | 1 |

| 1955 | 100.0 | 22.3 | 77.7 | 28.5 | 3.0 | 46.2 | 1 | 1 |

| 1960 | 100.0 | 19.8 | 80.2 | 36.3 | 2.5 | 41.3 | 1 | 1 |

| 1965 | 100.0 | 16.8 | 83.2 | 41.1 | 2.2 | 39.9 | 17.4 | 22.5 |

| 1966 | 100.0 | 16.4 | 83.6 | 37.7 | 2.0 | 43.8 | 22.4 | 21.4 |

| 1967 | 100.0 | 10.6 | 89.4 | 33.5 | 1.6 | 54.3 | 34.2 | 20.1 |

| 1968 | 100.0 | 10.9 | 89.1 | 33.2 | 1.7 | 54.2 | 34.7 | 19.5 |

| 1969 | 100.0 | 10.7 | 89.3 | 33.9 | 1.3 | 54.0 | 35.2 | 18.8 |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 11.4 | 88.6 | 34.6 | 1.6 | 52.4 | 34.1 | 18.4 |

| 1971 | 100.0 | 10.1 | 89.9 | 35.0 | 1.7 | 53.1 | 35.0 | 18.1 |

| 1972 | 100.0 | 10.0 | 90.0 | 33.7 | 3.5 | 52.8 | 35.2 | 17.6 |

| 1973 | 100.0 | 10.1 | 89.9 | 33.5 | 3.5 | 52.9 | 35.3 | 17.6 |

| 1974 | 100.0 | 10.1 | 89.9 | 33.6 | 1.4 | 54.9 | 37.8 | 17.1 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 7.9 | 92.1 | 35.9 | 1.1 | 55.2 | 38.5 | 16.7 |

| 1976 | 100.0 | 8.5 | 91.5 | 37.0 | 1.2 | 53.4 | 39.0 | 14.4 |

| 1977 | 100.0 | 7.9 | 92.1 | 37.4 | 1.1 | 53.7 | 39.6 | 14.0 |

| 1978 | 100.0 | 7.3 | 92.7 | 37.6 | 1.0 | 54.2 | 39.9 | 14.3 |

| 1979 | 100.0 | 7.3 | 92.7 | 38.0 | 1.0 | 53.7 | 40.1 | 13.6 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 7.4 | 92.6 | 38.1 | 1.0 | 53.5 | 40.6 | 13.0 |

| 1981 | 100.0 | 7.8 | 92.2 | 37.9 | 1.1 | 53.2 | 41.2 | 12.0 |

| 1982 | 100.0 | 7.6 | 92.4 | 38.1 | 1.0 | 53.2 | 41.0 | 12.2 |

| 1983 | 100.0 | 7.5 | 92.5 | 38.2 | 1.0 | 53.3 | 41.1 | 12.1 |

Disaggregation not available.

SOURCE: Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, Health Care Financing Administration.

Table 8. Aggregate and per capita amount and percent distribution of expenditures for physicians' services, by source of funds: Selected years 1950-83.

| Year | Total | Patient direct payments | All third parties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Total | Private | Public | ||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| Health insurance | Other | Total | Federal | State and local | ||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||

| 1950 | $ 2.7 | $ 2.3 | $ .5 | $ .3 | 2 | $ .1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1955 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 1.1 | .9 | 2 | .2 | 1 | 1 |

| 1960 | 5.7 | 3.7 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 2 | .4 | 1 | 1 |

| 1965 | 8.5 | 5.2 | 3.3 | 2.7 | 2 | .6 | $ .2 | $ .4 |

| 1966 | 9.2 | 5.5 | 3.7 | 2.8 | 2 | .8 | .3 | .5 |

| 1967 | 10.1 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 2 | 2.0 | 1.4 | .7 |

| 1968 | 11.1 | 5.2 | 5.9 | 3.4 | 2 | 2.5 | 1.8 | .7 |

| 1969 | 12.6 | 5.8 | 6.8 | 4.0 | 2 | 2.8 | 2.0 | .7 |

| 1970 | 14.3 | 6.5 | 7.8 | 4.8 | 2 | 3.0 | 2.1 | .9 |

| 1971 | 15.9 | 7.1 | 8.8 | 5.3 | 2 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 1.0 |

| 1972 | 17.2 | 7.2 | 10.0 | 6.0 | 2 | 3.9 | 2.8 | 1.2 |

| 1973 | 19.1 | 7.8 | 11.3 | 6.9 | 2 | 4.4 | 3.1 | 1.4 |

| 1974 | 21.2 | 7.7 | 13.5 | 8.1 | 2 | 5.4 | 3.8 | 1.6 |

| 1975 | 24.9 | 8.5 | 16.4 | 9.9 | 2 | 6.6 | 4.7 | 1.9 |

| 1976 | 27.6 | 9.0 | 18.5 | 11.4 | 2 | 7.1 | 5.2 | 1.9 |

| 1977 | 31.9 | 10.8 | 21.1 | 13.0 | 2 | 8.1 | 6.0 | 2.1 |

| 1978 | 35.8 | 11.5 | 24.3 | 15.0 | 2 | 9.3 | 6.9 | 2.3 |

| 1979 | 40.2 | 12.4 | 27.8 | 17.1 | 2 | 10.7 | 8.1 | 2.6 |

| 1980 | 46.8 | 14.3 | 32.6 | 19.9 | 2 | 12.6 | 9.7 | 3.0 |

| 1981 | 54.8 | 16.3 | 38.5 | 23.4 | 2 | 15.0 | 11.7 | 3.3 |

| 1982 | 61.8 | 17.8 | 44.0 | 27.1 | 2 | 16.9 | 13.4 | 3.5 |

| 1983 | 69.0 | 19.6 | 49.5 | 30.1 | 2 | 19.3 | 15.6 | 3.7 |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||

| 1950 | 100.0 | 83.2 | 16.8 | 11.4 | 3 | 5.2 | 1 | 1 |

| 1955 | 100.0 | 69.8 | 30.2 | 23.2 | 2 | 6.7 | 1 | 1 |

| 1960 | 100.0 | 65.4 | 34.6 | 28.0 | 2 | 6.4 | 1 | 1 |

| 1965 | 100.0 | 61.6 | 38.4 | 31.4 | .1 | 6.9 | 1.8 | 5.1 |

| 1966 | 100.0 | 60.0 | 40.0 | 30.7 | .1 | 9.3 | 3.4 | 5.9 |

| 1967 | 100.0 | 50.3 | 49.7 | 29.4 | .1 | 20.2 | 13.6 | 6.6 |

| 1968 | 100.0 | 46.9 | 53.1 | 30.5 | .1 | 22.5 | 15.8 | 6.7 |

| 1969 | 100.0 | 46.2 | 53.8 | 31.8 | .1 | 21.9 | 16.2 | 5.8 |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 45.4 | 54.6 | 33.6 | .1 | 20.9 | 14.9 | 6.0 |

| 1971 | 100.0 | 44.8 | 55.2 | 33.4 | .1 | 21.7 | 15.5 | 6.3 |

| 1972 | 100.0 | 41.9 | 58.1 | 35.1 | .1 | 22.9 | 16.2 | 6.7 |

| 1973 | 100.0 | 40.7 | 59.3 | 36.0 | .1 | 23.3 | 16.1 | 7.1 |

| 1974 | 100.0 | 36.4 | 63.6 | 38.4 | .1 | 25.2 | 17.8 | 7.4 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 34.1 | 65.9 | 39.5 | .1 | 26.4 | 18.8 | 7.6 |

| 1976 | 100.0 | 32.7 | 67.3 | 41.5 | .1 | 25.7 | 18.7 | 7.0 |

| 1977 | 100.0 | 33.8 | 66.2 | 40.8 | .1 | 25.4 | 18.7 | 6.7 |

| 1978 | 100.0 | 32.1 | 67.9 | 41.9 | .1 | 25.9 | 19.3 | 6.5 |

| 1979 | 100.0 | 30.9 | 69.1 | 42.4 | 3 | 26.6 | 20.2 | 6.5 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 30.5 | 69.5 | 42.5 | 3 | 26.9 | 20.6 | 6.3 |

| 1981 | 100.0 | 29.7 | 70.3 | 42.8 | 3 | 27.4 | 21.4 | 6.0 |

| 1982 | 100.0 | 28.8 | 71.2 | 43.8 | 3 | 27.4 | 21.7 | 5.7 |

| 1983 | 100.0 | 28.3 | 71.7 | 43.7 | 3 | 28.0 | 22.6 | 5.3 |

Disaggregation not available.

Less than $50 million.

Less than 0.5 percent.

SOURCE: Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, Health Care Financing Administration.

Insurance coverage for other health care services, while growing, has been more limited (Table 9). Dental care is one example. Enrollment for dental benefits rose over 50 percent between 1976 and 1979 to a total of 60.3 million persons (Carroll and Arnett, 1981). Insurance paid for about 34 percent of all dental expenditures in 1983. Vision care benefits, although not large in dollar terms, also has experienced significant growth in recent years.

Table 9. Aggregate and per capita amount and percent distribution of other personal health care expenditures,1 by source of funds: Selected years 1950-83.

| Year | Total | Patient direct payments | All third parties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Total | Private | Public | ||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| Health insurance | Other | Total | Federal | State and local | ||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||

| 1950 | $ 4.3 | $ 3.7 | $ .6 | 2 | $ .2 | $ .4 | 3 | 3 |

| 1955 | 6.1 | 5.2 | .9 | 2 | .2 | .6 | 3 | 3 |

| 1960 | 8.9 | 7.5 | 1.4 | $ .1 | .3 | 1.0 | 3 | 3 |

| 1965 | 13.4 | 10.9 | 2.5 | .3 | .5 | 1.7 | $ 1.0 | $ .7 |

| 1966 | 14.7 | 11.5 | 3.2 | .3 | .5 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| 1967 | 16.0 | 11.9 | 4.1 | .5 | .5 | 3.0 | 1.8 | 1.2 |

| 1968 | 18.1 | 13.2 | 4.9 | .5 | .6 | 3.8 | 2.3 | 1.5 |

| 1969 | 20.2 | 14.6 | 5.6 | .7 | .6 | 4.3 | 2.6 | 1.7 |

| 1970 | 23.1 | 16.8 | 6.3 | .8 | .6 | 4.8 | 2.9 | 1.9 |

| 1971 | 25.2 | 17.8 | 7.4 | 1.0 | .7 | 5.7 | 3.4 | 2.2 |

| 1972 | 28.2 | 19.9 | 8.2 | 1.2 | .8 | 6.3 | 3.8 | 2.5 |

| 1973 | 31.0 | 21.6 | 9.4 | 1.4 | .8 | 7.1 | 4.3 | 2.8 |

| 1974 | 35.2 | 23.6 | 11.6 | 1.9 | .9 | 8.9 | 5.4 | 3.5 |

| 1975 | 39.8 | 25.4 | 14.4 | 2.6 | 1.0 | 10.8 | 6.6 | 4.2 |

| 1976 | 44.4 | 27.8 | 16.6 | 3.7 | 1.1 | 11.8 | 7.2 | 4.6 |

| 1977 | 49.2 | 30.3 | 18.9 | 4.5 | 1.2 | 13.2 | 8.0 | 5.2 |

| 1978 | 55.3 | 33.6 | 21.7 | 5.4 | 1.3 | 15.0 | 9.0 | 6.0 |

| 1979 | 62.4 | 37.0 | 25.4 | 6.8 | 1.4 | 17.2 | 10.3 | 6.8 |

| 1980 | 71.0 | 40.7 | 30.3 | 8.8 | 1.6 | 19.9 | 11.8 | 8.1 |

| 1981 | 80.7 | 45.3 | 35.4 | 10.6 | 1.8 | 23.0 | 14.0 | 9.1 |

| 1982 | 88.0 | 49.1 | 38.9 | 12.2 | 1.9 | 24.7 | 15.3 | 9.4 |

| 1983 | 97.1 | 54.5 | 42.6 | 13.7 | 2.1 | 26.8 | 16.8 | 10.0 |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||

| 1950 | 100.0 | 86.2 | 13.8 | 2 | 4.2 | 9.6 | 3 | 3 |

| 1955 | 100.0 | 85.6 | 14.4 | 2 | 4.1 | 10.3 | 3 | 3 |

| 1960 | 100.0 | 83.9 | 16.1 | 1.1 | 3.3 | 11.6 | 3 | 3 |

| 1965 | 100.0 | 81.6 | 18.4 | 1.9 | 3.5 | 13.0 | 7.8 | 5.2 |

| 1966 | 100.0 | 78.4 | 21.6 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 16.1 | 9.6 | 6.5 |

| 1967 | 100.0 | 74.5 | 25.5 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 19.1 | 11.3 | 7.7 |

| 1968 | 100.0 | 73.1 | 26.9 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 21.0 | 12.6 | 8.3 |

| 1969 | 100.0 | 72.3 | 27.7 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 21.4 | 12.8 | 8.5 |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 72.9 | 27.1 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 20.8 | 12.4 | 8.3 |

| 1971 | 100.0 | 70.7 | 29.3 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 22.5 | 13.6 | 8.8 |

| 1972 | 100.0 | 70.7 | 29.3 | 4.1 | 2.8 | 22.4 | 13.4 | 9.0 |

| 1973 | 100.0 | 69.7 | 30.3 | 4.7 | 2.6 | 23.0 | 13.8 | 9.2 |

| 1974 | 100.0 | 66.9 | 33.1 | 5.3 | 2.5 | 25.3 | 15.5 | 9.8 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 63.9 | 36.1 | 6.5 | 2.5 | 27.1 | 16.5 | 10.6 |

| 1976 | 100.0 | 62.7 | 37.3 | 8.2 | 2.5 | 26.6 | 16.3 | 10.3 |

| 1977 | 100.0 | 61.6 | 38.4 | 9.2 | 2.4 | 26.8 | 16.3 | 10.5 |

| 1978 | 100.0 | 60.7 | 39.3 | 9.8 | 2.4 | 27.1 | 16.3 | 10.8 |

| 1979 | 100.0 | 59.3 | 40.7 | 10.9 | 2.3 | 27.5 | 16.6 | 10.9 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 57.3 | 42.7 | 12.4 | 2.2 | 28.0 | 16.6 | 11.4 |

| 1981 | 100.0 | 56.1 | 43.9 | 13.1 | 2.2 | 28.5 | 17.3 | 11.2 |

| 1982 | 100.0 | 55.8 | 44.2 | 13.9 | 2.2 | 28.1 | 17.3 | 10.7 |

| 1983 | 100.0 | 56.2 | 43.8 | 14.1 | 2.2 | 27.6 | 17.3 | 10.3 |

Dentists' services, other professional services, drugs and medical sundries, eyeglasses and appliances, nursing home care, and other personal health care.

Included with direct payments; separate data not available.

Disaggregation not available.

SOURCE: Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Bureau of Data Management and Strategy, Health Care Financing Administration.

Public expenditures

Government programs spent $124 billion for personal health care services in 1983, a 9.8 percent increase over 1982. Public programs financed almost 40 percent of all personal health care expenditures, including 53 percent of all hospital care, 28 percent of all physician services, and 48 percent of all nursing home care.

Federal expenditures of $93 billion for personal health care accounted for three-quarters of the public outlay and 30 percent of the total funding for personal health. Sixty-five percent of these Federal funds went towards purchases of hospital care; 17 percent, for physician services; and 9 percent, for nursing home care.

State and local governments financed $32 billion (10 percent) of personal health care services in 1983. Purchases of hospital services accounted for over half of the State and local expenditures; physician services, 12 percent; and nursing home care, 19 percent.

Public funding of personal health care changed dramatically with the advent of the Medicare and Medicaid programs. In 1965, 22 percent of all personal health care spending was publicly financed. Implementation of the Medicare and Medicaid programs rapidly boosted the proportion of public funding of personal health care to 34 percent in 1967. By 1980, public expenditures reached 40 percent and remained at that level through 1983. Federal funding has accounted for all of the growth in the proportion of public funds financing personal health care; the proportion of State and local funds actually declined over the period 1967 to 1983, from 13 percent to 10 percent.

From 1967 to 1983, the proportion of public funding to hospitals has remained stable (between 52 and 55 percent), with Federal funds (the Medicare program, specifically) accounting for a steadily increasing proportion of those public funds. During the same period, the proportion of public funding for physicians' services grew from 20 percent in 1967 to 28 percent in 1983. Once again, most of that increase can be attributed to the Medicare program.

Public financing of nursing home care grew from 34 percent in 1965 to 49 percent in 1967, peaked at 56 percent in 1975, and declined to 48 percent in 1983. Public financing for nursing home care comes predominantly through the Medicaid program, where costs are shared between the Federal and State and local governments.

Public financing for health care services comes from a number of Federal, State, and local programs (Table 10). Some, such as the Veterans' Administration and the U.S. Department of Defense, provide services directly through networks of hospitals, clinics, and nursing homes. The same agencies also pay public and private facilities to provide services. In the Medicare program, the Federal Government acts as an insurer, providing funds for medical care for eligible aged and disabled people. In other programs, Federal funds flow to State governments, which contribute additional funds. States may administer a medical program, as in the case of Medicaid, or may let funds flow through to local government agencies, as is done with maternal and child health and other community-related grants. States also fund health programs independently in State-run hospitals or through public assistance vendor payments for individuals not covered by Medicaid.

Table 10. Expenditures for health services and supplies under public programs, by program, type of expenditure, and source of funds: Calendar years 1982-83.

| Program area | Health services and supplies | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total | Personal health care | Administration | Public health activities | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total | Hospital care | Physicians' services | Dentists' services | Other professional services- | Drugs etc. | Eye glasses etc. | Nursing home care | Other care | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||||

| 1983 | ||||||||||||

| Total health services and supplies | $340.1 | $313.3 | $147.2 | $69.0 | $21.8 | $8.0 | $23.7 | $6.2 | $28.8 | $8.5 | $15.6 | $11.2 |

| All public programs | 140.3 | 124.5 | 78.4 | 19.3 | .6 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 14.0 | 6.6 | 4.6 | 11.2 |

| Total Federal expenditures | 96.8 | 93.0 | 60.6 | 15.6 | .3 | 1.9 | 1.1 | .9 | 8.1 | 4.5 | 2.6 | 1.2 |

| Total State and local expenditures | 43.5 | 31.5 | 17.8 | 3.7 | .3 | .5 | 1.1 | .1 | 5.9 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 10.0 |

| Medicare1 (Federal) | 58.8 | 57.4 | 40.4 | 13.4 | --- | 1.5 | --- | .8 | .5 | .9 | 1.4 | --- |

| Medicaid2 | 35.6 | 34.0 | 13.6 | 2.9 | .5 | .8 | 1.9 | --- | 12.4 | 2.0 | 1.7 | --- |

| Federal expenditures | 19.2 | 18.1 | 6.9 | 1.6 | .3 | .4 | 1.0 | --- | 7.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | --- |

| State and local expenditures | 16.4 | 15.8 | 6.7 | 1.4 | .2 | .4 | .9 | --- | 5.4 | .9 | .6 | --- |

| Other public assistance payments for medical care | 1.6 | 1.6 | .7 | .2 | .0 | .0 | .1 | --- | .5 | .1 | --- | --- |

| Federal | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| State and local | 1.6 | 1.6 | .7 | .2 | .0 | .0 | .1 | --- | .5 | .1 | --- | --- |

| Veterans' medical care | 7.7 | 7.6 | 6.3 | .1 | .0 | --- | .0 | .1 | .5 | .6 | .1 | --- |

| Department of defense medical care3 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 5.3 | .2 | .0 | --- | .0 | --- | --- | 1.0 | .1 | --- |

| Workers compensation | 6.4 | 5.0 | 2.6 | 2.1 | --- | .2 | .1 | .1 | --- | 1.4 | --- | |

| Federal employees | .3 | .3 | .2 | .1 | --- | .0 | .0 | .0 | --- | --- | .0 | --- |

| State and local programs | 6.1 | 4.8 | 2.4 | 2.0 | --- | .1 | .1 | .1 | --- | --- | 1.4 | --- |

| State and local hospitals4 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 7.9 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Other public expenditures for personal health care5 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 1.7 | .3 | .0 | .1 | .0 | .1 | --- | 2.2 | .1 | --- |

| Federal | 3.0 | 3.0 | 1.6 | .2 | .0 | .0 | .0 | .0 | --- | 1.1 | .0 | --- |

| State and local | 1.5 | 1.4 | .2 | .1 | .0 | .0 | .0 | .0 | --- | 1.1 | .1 | --- |

| Government public health activities | 11.2 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 11.2 |

| Federal | 1.2 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.2 |

| State and local | 10.0 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 10.0 |

| Addenda: Medicare and Medicaid | 94.0 | 91.0 | 53.9 | 16.3 | .5 | 2.2 | 1.9 | .8 | 12.9 | 2.4 | 3.1 | --- |

| 1982 | ||||||||||||

| Total health services and supplies | $308.1 | $284.7 | $134.9 | $61.8 | $19.5 | $7.1 | $21.8 | $5.5 | $26.5 | $7.6 | $13.4 | $10.0 |