Abstract

Health expenditure growth is projected to moderate considerably during 1983-90, reaching $660 billion in 1990 and consuming over 11 percent of the gross national product. During 1973-83, spending for health care more than tripled, increasing from $103 billion to $355 billion and moving from 7.8 percent to 10.8 percent of the gross national product. Government spending for health care is projected to reach $284 billion by 1990, with the Federal Government paying 73 percent. The Medicare Prospective Payment System, private sector initiatives, and State and local government actions are providing incentives to substantially increase competition and cost effectiveness in health care provision.

Introduction

Economic forces are limiting the ability of buyers to pay for increasingly costly health care. Major buyers of care such as the Federal Government, State and local governments, and corporate businesses, are putting mounting pressures on health care providers to reduce the rate of increase in health care costs without lowering the quality of care. Competition among providers will intensify, providing additional incentives to integrate clinical practice styles with improved management practices. The entire health sector is affected by this increasing emphasis on financial incentives, cost effectiveness, and competition: long-term and short-term care, inpatient and ambulatory care, medical supplies and equipment industry, pharmaceutical industry, biomedical research, insurance industry, and medical facilities construction. Many of the factors shaping the future of the health sector can be anticipated, but not quantified in terms of magnitude or timing.

The implementation by the Health Care Financing Administration of the Medicare Prospective Payment System (PPS) for hospital inpatient services, has provided an incentive to merge clinical medicine and quality of care issues with management, finance, and information support systems. Under PPS, payment per case for hospital inpatient services is fixed in advance through diagnostic-related groups (DRG's) pricing. Every major part of our health care system is likely to be affected by the direct and secondary effects of the PPS as it evolves into the late 1980's.

The following questions are likely to surface with increasing frequency in the 1980's: What is good health? What is good quality health care? What is cost-effective health care? What can we (individual households, firms, State and local governments, Federal Government) afford to pay, given other demands on resources? The Prospective Payment Assessment Commission (ProPAC), will focus on some of these clinical and financial questions for hospital inpatient services covered under the Medicare PPS. Analyses, discussions, and revised regulations derived from ProPAC initiatives are expected to have indirect effects on other health care sectors as well.

Managers, policymakers and providers in the health sector, as in all sectors, must incorporate estimates of future trends into today's decisions. Inflation, economic shocks, changes in Government regulations, and unanticipated outcomes of policies over the last decade have intensified the need for periodic assessments of individual industries and their relationship to the larger economy. This article provides such an assessment for the health care industry by providing baseline current-law projections of national health expenditures through 1990. For more indepth analysis of the Medicare PPS program and spending for individual health services, see Freeland and Schendler (1984).

Highlights

The 1980's will be marked by a period of adjustment as health care markets and institutions adapt to innovative reimbursement reforms and increasing competition.

Under the projection assumptions, the rate of economy-wide inflation will moderate substantially in the late 1980's, resulting in a deceleration of health expenditure growth.

Growth in real gross national product (GNP) is projected to increase at twice the rate of the 1973-1983 period, resulting in upward pressure for growth in real health spending as the ability to finance care increases.

The population 75 years of age or over is projected to increase four times as fast as the average annual rate for persons under age 65. Since this group consumes a disproportionate amount of health care, this will lead to upward pressure on expenditure growth, especially for long-term care.

National health expenditures are projected to increase at an average annual rate of 9 percent for the period 1983-90, a significant decline from the 13 percent average annual growth in the 1973-83 period. This lower rate of increase reflects the net effect of projected economy-wide forces and projected effects of health-industry-specific factors such as the PPS, private sector initiatives, and increasing competition.

Growth in personal health expenditures per capita is projected to slow to an average annual rate of approximately 8 percent for the period 1983-90, a significant decline from the 12 percent growth rate for 1973-83.

Per capita expenditures for 1990 are projected to be approximately $2,550 for total health care, $ 1,070 for hospital care, and $500 for physicians' services.

All Government spending for health care is projected to reach $284 billion by 1990, three-fourths of which the Federal Government will finance.

Private spending is estimated to reach $376 billion in 1990, or 57 percent of all health care expenditures.

Medicare is projected to fund a higher proportion of health spending, even with the deceleration resulting from implementation of PPS.

Evolution of health care delivery and finance

The projections contained in this article are an evolution of past trends and tendencies (Gibson et al., 1984) and assume no substantial departure from current health care delivery or payment systems. The key assumption is that the present extensive third-party payment system will remain in place, including the PPS for Medicare hospital inpatient services. However, trends and relationships are modified to reflect current-law reimbursement incentives, such as those associated with the Medicare PPS, where such shifts can be discerned by the authors.

Other evolving patterns significant to the health care sector for the 1980's are:

Continued growth in expensive, product-innovative diagnostic and therapeutic technologies, and an increased development and use of process-innovative technologies associated with increased productivity and decreased costs.

Reduced rate of growth of Government financing for health programs.

Increased rivalry and competition within and among various segments of the health care industry, resulting in: improved quality of services and products; expanded and intensified catchment area analyses1 to ascertain needs of potential patients and characteristics of competing providers; increased responsiveness to patients; more emphasis on clinical competence and personal effectiveness (“bedside manner”); improved management information systems that merge clinical (patient and provider) and financial data; greater use of medical records specialists, cost accountants, industrial engineers, and strategic planners; increased consumer health education and advertising; and greater use of cost-effective services and supplies (Hillestad and Berkowitz, 1984; Miller, 1984; and Sheldon, 1984).

Substantial variation in the viability of individual health care providers and of medical equipment and supply firms will become evident as the rate of growth in aggregate spending for health care slows. Providers and suppliers who respond effectively and timely to the new realities will find many opportunities in the late 1980's. Providers and suppliers who do not respond effectively to the more intense competition will experience declines in market share.

Projection scenario

Increases in national health care spending have varied in the past according to policy factors, economic conditions, and other variables. It is likely that volatility and spurts in spending will also occur in the projected period 1983-90. As it is not possible to accurately forecast the timing of turning points in health sector activity, trend projections that reflect average tendencies are used in this article. We focus on average annual rates of change. This projection scenario assumes no unanticipated events and can be used as a baseline from which alternative scenarios can be constructed.

The model incorporates economic, actuarial, statistical, demographic, and judgmental factors into a single, integrated framework. There are four major interrelated components of the model: 1) a five-factor model of expenditure growth, 2) supply variables, 3) a channel of finance module; and 4) a net cost of private health insurance/program administration cost module.2

Assumptions for current-law projections

These current-law projections are based on a set of assumptions relating to the health care sector and to the economy as a whole. The fundamental assumption is that historical trends and relationships will continue into the future. Adjustments are made to trends and relationships to reflect current-law reimbursement incentives such as those associated with the Medicare PPS. Further, it is assumed that:

The competitive structure, conduct, and performance of the health care delivery system will continue to evolve along patterns followed during the historical period (1965–83).

No major technological breakthrough in treatment of acute and chronic illnesses that would significantly alter evolving patterns of morbidity and mortality or health care delivery will occur.

Use of medical care, including intensity of services per case, will continue to grow in accordance with historical relationships and trends, reflecting clinical practice patterns and demand factors. As mentioned previously, historical trends are modified to reflect current-law reimbursement incentives, where such shifts can be discerned.

Population will grow as projected by the Office of the Actuary, Social Security Administration (Tables 1 and 2).

Health manpower will increase as projected by the Bureau of Health Professions (Table 3).

The GNP and the implicit price deflator for the GNP will grow as projected in economic assumptions incorporated in the Midsession Review of the 1985 Budget (Table 1)3.

Medical care prices will vary with the implicit price deflator for the GNP, according to relationships established in the historical period studied (1965-83), but modified to reflect projected incentives and constraints.

Benefit outlays and administrative expenses for Medicare and aggregate Federal Medicaid outlays will grow as projected in the Midsession Review of the 1985 Budget (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 1. Historical estimates and projections of gross national product inflation, and population: Selected years, 1950-90.

| Calendar year | Gross national product (GNP)1 | Consumer Price1,

2 Index (CPI)—all items wage earners (1967 = 100.0) |

Total3 population July 1 in thousands | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Current dollars in billions | 1972 dollars in billions | Implicit price deflator (1972 = 100.0) |

|||

| Historical estimates | |||||

| 1950 | $286.5 | $534.8 | 53.5 | 72.1 | 157,313 |

| 1955 | 400.0 | 657.5 | 60.8 | 80.3 | 174,028 |

| 1960 | 506.5 | 737.2 | 68.7 | 88.6 | 188,943 |

| 1965 | 691.0 | 929.3 | 74.4 | 94.4 | 203,032 |

| 1970 | 992.7 | 1,085.6 | 91.4 | 116.3 | 214,024 |

| 1973 | 1,326.4 | 1,254.3 | 105.7 | 133.1 | 220,779 |

| 1975 | 1,549.2 | 1,231.7 | 125.7 | 161.3 | 224,761 |

| 1979 | 2,417.8 | 1,479.4 | 163.4 | 217.6 | 233,770 |

| 1980 | 2,631.7 | 1,475.0 | 178.4 | 246.9 | 236,415 |

| 1981 | 2,957.8 | 1,512.2 | 195.6 | 272.2 | 238,705 |

| 1982 | 3,069.2 | 1,480.0 | 207.4 | 288.5 | 241,053 |

| 1983 | 3,304.8 | 1,534.7 | 215.3 | 297.3 | 243,297 |

| Projections | |||||

| 1985 | 3,994.0 | 1,707.0 | 234.0 | 321.9 | 247,810 |

| 1988 | 5,084.4 | 1,920.2 | 264.8 | 364.4 | 254,499 |

| 1990 | 5,857.8 | 2,066.7 | 283.4 | 390.0 | 258,811 |

| Selected periods | Average annual percent change | ||||

| 1950-55 | 6.9 | 4.2 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.0 |

| 1955-60 | 4.8 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 1.7 |

| 1960-65 | 6.4 | 4.7 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| 1965-70 | 7.5 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 1.1 |

| 1970-75 | 9.3 | 2.6 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 1.0 |

| 1975-80 | 11.2 | 3.7 | 7.3 | 8.9 | 1.0 |

| 1980-85 | 8.7 | 3.0 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 0.9 |

| 1985-90 | 8.0 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 0.9 |

| 1979-83 | 8.1 | 0.9 | 7.1 | 8.1 | 1.0 |

| 1983-85 | 9.9 | 5.5 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 0.9 |

| 1985-88 | 8.4 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 0.9 |

| 1988-90 | 7.3 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 0.8 |

| 1983-88 | 9.0 | 4.6 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 0.9 |

| 1973-83 | 9.6 | 2.0 | 7.4 | 8.4 | 1.0 |

| 1983-90 | 8.5 | 4.3 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 0.9 |

Historical estimates are reported in Economic Report of the President February 1984. Projection growth rates are from Executive Office of the President, Office of Management and Budget, Midsession Review of the 1985 Budget August 15, 1984. The average annual rate of growth in GNP for 1983-90 used in this projection is within 0.2 percentage point of the rate used by the private consulting firm of Data Resources, Inc. See U.S. Long-Term Review Fall 1984 (Forecast: TREND25YR0984).

The CPI is shown for comparison only. The implicit price deflator for GNP is used in the projection process to reflect cost pressures external to health care industry.

Historical estimates and projections of population are from Wade (1984). Alternative II (intermediate) assumptions for population growth were used.

Table 2. Number of persons and proportions of the population under 65 years of age, 65 years of age or over, and 75 years of age or over: Selected years, 1960-901.

| Year | All ages | Under 65 years | 65 years or over | 75 years or over | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Number of persons2 | Percent distribution | Number of persons2 | Percent distribution | Number of persons2 | Percent distribution | Number of persons2 | Percent distribution | |

| Historical | ||||||||

| 1960 | 188,943 | 100.0 | 171,796 | 90.9 | 17,147 | 9.1 | 5,775 | 3.1 |

| 1965 | 203.032 | 100.0 | 184,080 | 90.7 | 18,952 | 9.3 | 6,879 | 3.4 |

| 1970 | 214,024 | 100.0 | 193,343 | 90.3 | 20,681 | 9.7 | 8,133 | 3.8 |

| 1973 | 220,779 | 100.0 | 198,652 | 90.0 | 22,127 | 10.0 | 8,805 | 4.0 |

| 1975 | 224,761 | 100.0 | 201,452 | 89.6 | 23,309 | 10.4 | 9,308 | 4.1 |

| 1979 | 233,770 | 100.0 | 207,990 | 89.0 | 25,780 | 11.0 | 10,324 | 4.4 |

| 1980 | 236,415 | 100.0 | 210,051 | 88.8 | 26,364 | 11.2 | 10,585 | 4.5 |

| 1981 | 238,705 | 100.0 | 211,777 | 88.7 | 26,928 | 11.3 | 10,900 | 4.6 |

| 1982 | 241,053 | 100.0 | 213,550 | 88.6 | 27,503 | 11.4 | 11,238 | 4.7 |

| 1983 | 243,297 | 100.0 | 215,219 | 88.5 | 28,078 | 11.5 | 11,558 | 4.8 |

| Projections | ||||||||

| 1985 | 247,810 | 100.0 | 218,491 | 88.2 | 29,319 | 11.8 | 12,226 | 4.9 |

| 1988 | 254,499 | 100.0 | 223,174 | 87.7 | 31,325 | 12.3 | 13,325 | 5.2 |

| 1990 | 258,811 | 100.0 | 226,241 | 87.4 | 32,570 | 12.6 | 14,054 | 5.4 |

| Selected periods | Average annual percent change | |||||||

| 1973-83 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 2.4 | 2.8 | ||||

| 1983-85 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 2.8 | ||||

| 1983-88 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 2.9 | ||||

| 1983-90 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 2.8 | ||||

Derived from Wade (1984). Alternative II (intermediate) assumptions for population growth were used.

Number in thousands as of July 1.

Table 3. Historical estimates and projections of active physicians and dentists: Selected years, 1950-901.

| Year | Number of active physicians is as of December 31 | Number of active dentists as of December 31 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Total | M.D.'s | D.O.'S | |||

| Historical estimates | |||||

| 1950 | 219,900 | 209,000 | 10,900 | 79,190 | |

| 1955 | 240,200 | 228,600 | 11,600 | 84,370 | |

| 1960 | 259,400 | 247,300 | 12,200 | 90,120 | |

| 1965 | 288,700 | 277,600 | 211,100 | 95,990 | |

| 1970 | 326,500 | 314,200 | 12,300 | 102,220 | |

| 1973 | 355,700 | 342,400 | 13,300 | 108,360 | |

| 1975 | 384,400 | 370,400 | 14,000 | 112,450 | |

| 1979 | 440,400 | 424,000 | 16,400 | 123,500 | |

| 1980 | 457,500 | 440,400 | 17,100 | 126,240 | |

| 1981 | 466,700 | 448,700 | 18,000 | 129,180 | |

| 1982 | 481,700 | 463,000 | 18,700 | 132,010 | |

| 1983 | 496,500 | 476,800 | 19,700 | 135,120 | |

| Projections | |||||

| 1985 | 527,900 | 506,000 | 21,900 | 140,920 | |

| 1988 | 569,100 | 543,600 | 25,500 | 147,730 | |

| 1990 | 594,600 | 566,800 | 27,800 | 151,320 | |

| Selected periods | Average annual percent change | ||||

| 1950-55 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.3 | |

| 1955-60 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.3 | |

| 1960-65 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2−1.9 | 1.3 | |

| 1965-70 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.3 | |

| 1970-75 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 2.6 | 1.9 | |

| 1975-80 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 2.3 | |

| 1980-85 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 5.1 | 2.2 | |

| 1985-90 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 4.9 | 1.4 | |

| 1983-85 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 5.4 | 2.1 | |

| 1985-88 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 5.2 | 1.6 | |

| 1988-90 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 4.4 | 1.2 | |

| 1983-88 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 5.3 | 1.8 | |

| 1965-83 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 1.9 | |

| 1973-83 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 2.2 | |

| 1983-90 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 5.0 | 1.6 | |

The decline in the number of active D.O.'s between 1960 and 1965 reflects the granting of approximately 2,400 M.D. degrees to osteopathic physicians who had graduated from the University of California College of Medicine at Irvine. These physicians are included with active M.D.'s beginning in 1962.

NOTE:

M.D. = medical doctors.

D.O. = doctors of osteopathy.

Table 4. Medicare benefit payments, by type of service and administrative expenses: Selected years, 1970-901.

| Calendar year | Medicare benefits and administrative expenses | Total Medicare benefits | Hospital care | Physicians' services | Other professional services2 | Eyeglasses and appliances | Nursing home care | Other personal health care | Medicare administrative expenses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in billions | |||||||||

| Historical3 | |||||||||

| 1970 | $7.5 | $7.1 | $5.1 | $1.6 | $0.1 | (5) | $0.3 | (5) | $0.4 |

| 1973 | 10.1 | 9.6 | 7.1 | 2.1 | 0.1 | $0.1 | 0.2 | (5) | 0.6 |

| 1975 | 16.3 | 15.6 | 11.5 | 3.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | $0.1 | 0.7 |

| 1979 | 30.3 | 29.3 | 21.2 | 6.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.0 |

| 1980 | 36.8 | 35.7 | 25.9 | 7.9 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.1 |

| 1981 | 44.8 | 43.5 | 31.3 | 9.7 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.3 |

| 1982 | 52.4 | 51.1 | 36.7 | 11.4 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.3 |

| 1983 | 58.8 | 57.4 | 40.4 | 13.4 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.4 |

| Projected4 | |||||||||

| 1985 | 75.7 | 74.1 | 52.4 | 16.6 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.6 |

| 1988 | 105.0 | 103.3 | 71.8 | 24.6 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| 1990 | 131.3 | 129.5 | 89.5 | 31.5 | 3.2 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| Selected periods | Average annual percent Change | ||||||||

| 1973-83 | 19.2 | 19.6 | 19.0 | 20.2 | 32.9 | 28.4 | 10.7 | 38.1 | 9.7 |

| 1979-83 | 18.0 | 18.3 | 17.5 | 19.8 | 28.7 | 30.0 | 9.5 | 20.3 | 8.3 |

| 1983-85 | 13.4 | 13.6 | 13.9 | 11.4 | 23.8 | 22.2 | 6.1 | 11.9 | 7.6 |

| 1983-88 | 12.3 | 12.5 | 12.2 | 12.9 | 12.7 | 19.1 | 8.1 | 11.7 | 3.9 |

| 1983-90 | 12.1 | 12.3 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 11.9 | 17.5 | 8.5 | 11.3 | 3.1 |

Service categories used in this table differ from those used in the annual reports of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds. For example, hospital-based home health services appear as hospital care rather than as home health services (which are included in other professional services).

Hospice benefits are included with other professional services. The benefit provision was effective November 1, 1983, and expires October 1, 1986.

Historical data are from Gibson, et al. (1984).

Projections are derived from Midsession Review of the 1985 Budget August 15, 1984. However, growth rates for 1984 were modified by the Medicare actuaries to reflect partial year experience. Projections of Medicare outlays are updated periodically through the year to reflect changes in regulations, revised forecasts of the economy, and program experience.

Less than $50 million.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 5. Federal share of Medicaid benefits and administrative expenses: Selected years, 1970-90.

| Calendar year | Total | Benefits | Administrative expenses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in billions | |||

| Historical1 | |||

| 1970 | $3.0 | $2.9 | $0.1 |

| 1973 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 0.2 |

| 1975 | 7.9 | 7.6 | 0.4 |

| 1979 | 13.0 | 12.2 | 0.8 |

| 1980 | 14.5 | 13.6 | 0.8 |

| 1981 | 17.3 | 16.2 | 1.1 |

| 1982 | 18.0 | 17.0 | 1.0 |

| 1983 | 19.2 | 18.1 | 1.1 |

| Projected2, 3 | |||

| 1985 | 23.4 | 22.1 | 1.3 |

| 1988 | 29.9 | 28.5 | 1.5 |

| 1990 | 35.6 | 34.0 | 1.5 |

| Average annual percent change | |||

| 1973-83 | 13.4 | 13.3 | 15.9 |

| 1979-83 | 10.2 | 10.4 | 7.2 |

| 1983-85 | 10.2 | 10.2 | 10.3 |

| 1983-88 | 9.3 | 9.4 | 6.3 |

| 1983-90 | 9.2 | 9.4 | 5.2 |

Historical Medicaid financial data on outlays reflect changes in services incurred and cash flow adjustments (Gibson, et al., 1984).

The projections are derived from changes in Medicaid benefits and administrative expenses prepared for Midsession Review of the 1985 Budget August 15, 1984. The Midsession Review projections extend through fiscal year 1990. Projections through calendar year 1990 were prepared for this report.

Projections of the Federal share of Medicaid vendor payments are updated periodically through the year to reflect changes in regulations, revised forecasts of the economy, and current program experience.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Division of National Cost Estimates.

The short-term economic outlook for 1983-85, compared to 1981-83, can be characterized by a deceleration in inflation accompanied by strong real growth in the economy. The GNP deflator is projected to increase at an average annual rate of about 4 percent for the period 1983-85, compared to a 5 percent annual rate for the 1981-83 period.

Real GNP increased at an average annual rate of less than 1 percent during 1981 -83, compared to the short-term projection of more than 5 percent. The faster growth in real GNP implies a greater ability of the economy to finance spending increases for all types of goods and services, including health.

For the mid-term period 1985-88, current dollar GNP is projected to increase at an average annual rate of about 8 percent with economy-wide prices and real GNP each increasing at approximately half that rate. For the last years of the projection period, 1988-90, the growth rates of the GNP deflator and real GNP are each expected to slow to between 3 and 4 percent.

For the long-term or overall projection period, 1983-90, the GNP deflator is expected to slow significantly to a projected 4 percent rate of growth, or half the rate of growth during 1973-83. Real GNP is assumed to increase at an average annual rate of 4 percent for the 1983-90 period, twice as fast as the 1973-83 interval. Thus, for the projection period (1983-90), prices are assumed to grow at a substantially slower rate and real GNP to rise significantly faster. This deceleration in economy-wide inflation has a significant impact on health care spending since approximately 60 percent of the growth in health care spending can be accounted for by economy-wide inflation. Thus, projections of health care spending are sensitive to relatively small errors in forecasting economy-wide inflation.

Shifts in the age composition of the population is a factor which will tend to cause health expenditures to rise in the 1980's. Use of medical care by the elderly population is disproportionate to their numbers (Fisher, 1980; Waldo and Lazenby, 1984). The number of persons 75 years of age or over is projected to increase at an average rate of almost 3 percent in the period 1983-90, compared to less than 1 percent for the population under 65 years of age (Table 2). The projected growth rates are essentially the same as for 1973-83. The proportion of the total population 65 years of age or over will rise from 11.5 percent in 1983 to 12.6 percent in 1990. Total population is projected to increase at an average annual rate of 0.9 percent from 1983-90.

The number of active physicians is projected to grow from 496,000 in 1983 to 595,000 in 1990 (Table 3), an aggregate increase of 20 percent, or nearly three times the projected aggregate population growth. The number of active dentists is projected to increase from 135,000 in 1983 to 151,000 in 1990, a 12 percent increase (Table 3). This increase is twice as fast as aggregate population growth. However, over the long run, the growth in the number of physicians and dentists is projected to decelerate during the last half of the 1980's, declining from the peak growth rate of the last half of the 1970's.

Overview of projections

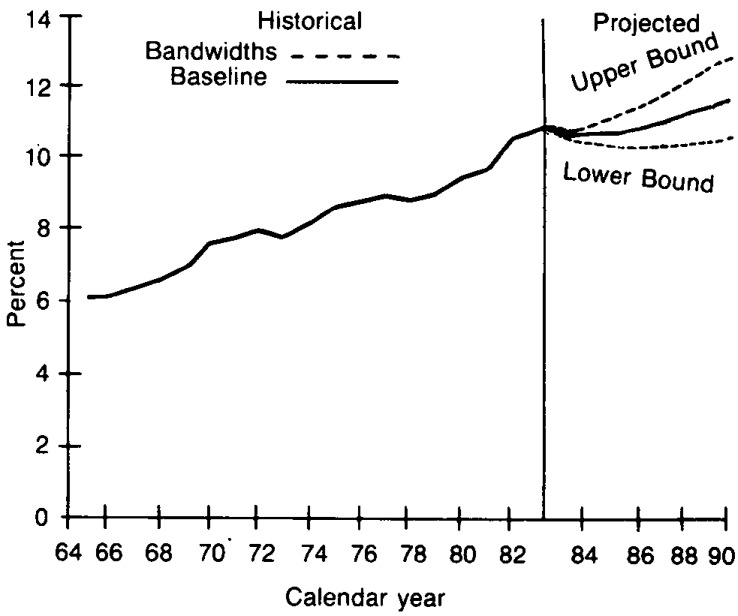

Outlays for total national health expenditures are expected to increase at substantially lower rates in the projected period (1983-90), both absolutely and in relation to the GNP (Figure 1 and Table 6). Projected outlays are:

Figure 1. National health expenditures as percent of gross national product with bandwidths: 1965-901.

1The conditional bandwidths around (he baseline projection scenario provide one indicator 0(variability. The standard error associated with annual percent increases in the ratio of national health expenditures to gross national product for 1966-83 was multiplied by a t-distribution value of 2.11 to derive the conditional “95 percent” bandwidths. The calculated bandwidfhs are approx-imate and are used as a rough guide in assessing variability and uncertainty. It is important to keep in mind the potential dangers of exfrapolating historical measures of variability into the future; that is, there can be no assurance that future variability will replicate historical variability.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 6. National health expenditures, by source of funds and percent of gross national product (GNP): Selected calendar years, 1950-90.

| Calendar year | Gross national product in billions | Total | Private | Public | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Amount in billions | Per capita | Percent of GNP | Amount in billions | Percent of total | Total | Federal | State and local | |||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Amount in billions | Percent of total | Amount in billions | Percent of total | Amount in billions | Percent of total | |||||||

| Historical estimates1 | ||||||||||||

| 1950 | $286.5 | $12.7 | $82 | 4.4 | $9.2 | 72.8 | $3.4 | 27.2 | $1.6 | 12.8 | $1.8 | 14.4 |

| 1955 | 400.1 | 17.7 | 105 | 4.4 | 13.2 | 74.3 | 4.6 | 25.7 | 2.0 | 11.3 | 2.6 | 14.4 |

| 1960 | 506.5 | 26.9 | 146 | 5.3 | 20.3 | 75.3 | 6.6 | 24.7 | 3.0 | 11.2 | 3.6 | 13.5 |

| 1965 | 691.0 | 41.9 | 207 | 6.1 | 30.9 | 73.8 | 11.0 | 26.2 | 5.5 | 13.2 | 5.5 | 13.0 |

| 1970 | 992.7 | 75.0 | 350 | 7.6 | 47.2 | 63.0 | 27.8 | 37.1 | 17.7 | 23.6 | 10.1 | 13.5 |

| 1973 | 1,326.4 | 103.4 | 468 | 7.8 | 64.0 | 61.9 | 39.4 | 38.1 | 25.2 | 24.4 | 14.2 | 13.7 |

| 1975 | 1,549.2 | 132.7 | 590 | 8.6 | 76.3 | 57.5 | 56.4 | 42.4 | 37.1 | 27.9 | 19.3 | 14.5 |

| 1979 | 2,417.8 | 215.1 | 920 | 8.9 | 124.2 | 57.7 | 90.8 | 42.3 | 61.0 | 28.4 | 29.8 | 13.9 |

| 1980 | 2,631.7 | 248.0 | 1,049 | 9.4 | 142.2 | 57.3 | 105.9 | 42.7 | 71.1 | 28.7 | 34.8 | 14.0 |

| 1981 | 2,957.8 | 285.8 | 1,197 | 9.7 | 164.2 | 57.4 | 121.6 | 42.5 | 83.5 | 29.2 | 38.1 | 13.3 |

| 1982 | 3,069.2 | 322.3 | 1,337 | 10.5 | 186.5 | 57.9 | 135.9 | 42.1 | 93.3 | 28.9 | 42.6 | 13.2 |

| 1983 | 3,304.8 | 355.4 | 1,461 | 10.8 | 206.6 | 58.1 | 148.8 | 41.9 | 102.7 | 28.9 | 46.1 | 13.0 |

| Projections | ||||||||||||

| 1985 | 3,994.0 | 419.5 | 1,693 | 10.5 | 240.0 | 57.2 | 179.6 | 42.8 | 127.6 | 30.4 | 51.9 | 12.4 |

| 1988 | 5,084.4 | 552.4 | 2,171 | 10.9 | 316.7 | 57.3 | 235.7 | 42.6 | 170.8 | 30.9 | 64.9 | 11.7 |

| 1990 | 5,857.8 | 660.1 | 2,551 | 11.3 | 375.7 | 56.9 | 284.5 | 43.1 | 208.6 | 31.6 | 75.9 | 11.5 |

| Selected periods | Average annual percent change | |||||||||||

| 1950-55 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 5.2 | — | 7.4 | — | 5.8 | — | 4.6 | — | 7.6 | — |

| 1955-60 | 4.8 | 8.7 | 6.8 | — | 9.0 | — | 7.8 | — | 8.5 | — | 6.7 | — |

| 1960-65 | 6.4 | 9.2 | 7.6 | — | 8.8 | — | 10.2 | — | 12.9 | — | 7.6 | — |

| 1965-70 | 7.5 | 12.3 | 11.2 | — | 8.8 | — | 20.4 | — | 26.1 | — | 13.1 | — |

| 1970-75 | 9.3 | 12.1 | 11.0 | — | 10.1 | — | 15.2 | — | 16.0 | — | 13.8 | — |

| 1975-80 | 11.2 | 13.3 | 12.2 | — | 13.3 | — | 13.4 | — | 13.9 | — | 12.5 | — |

| 1980-85 | 8.7 | 11.1 | 10.0 | — | 11.0 | — | 11.2 | — | 12.4 | — | 8.4 | — |

| 1985-90 | 8.0 | 9.4 | 8.5 | — | 9.4 | — | 9.6 | — | 10.3 | — | 7.9 | — |

| 1979-83 | 8.1 | 13.4 | 12.3 | — | 13.6 | — | 13.1 | — | 13.9 | — | 11.5 | — |

| 1983-85 | 9.9 | 8.7 | 7.7 | — | 7.8 | — | 9.9 | — | 11.5 | — | 6.2 | — |

| 1985-88 | 8.4 | 9.6 | 8.6 | — | 9.7 | — | 9.5 | — | 10.2 | — | 7.7 | — |

| 1988-90 | 7.3 | 9.3 | 8.4 | — | 8.9 | — | 9.9 | — | 10.5 | — | 8.2 | — |

| 1965-83 | 9.1 | 12.6 | 11.5 | — | 11.1 | — | 15.6 | — | 17.6 | — | 12.6 | — |

| 1983-88 | 9.0 | 9.2 | 8.2 | — | 8.9 | — | 9.6 | — | 10.7 | — | 7.1 | — |

| 1973-83 | 9.6 | 13.1 | 12.0 | — | 12.4 | — | 14.2 | — | 15.1 | — | 12.5 | — |

| 1983-90 | 8.5 | 9.2 | 8.4 | — | 8.9 | — | 9.7 | — | 10.7 | — | 7.4 | — |

Historical estimates are from Gibson, et al. (1984).

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Division of National Cost Estimates.

$420 billion by 1985, or $ 1,693 per capita;

$552 billion by 1988, or $2,171 per capita;

$660 billion by 1990, or $2,551 per capita.

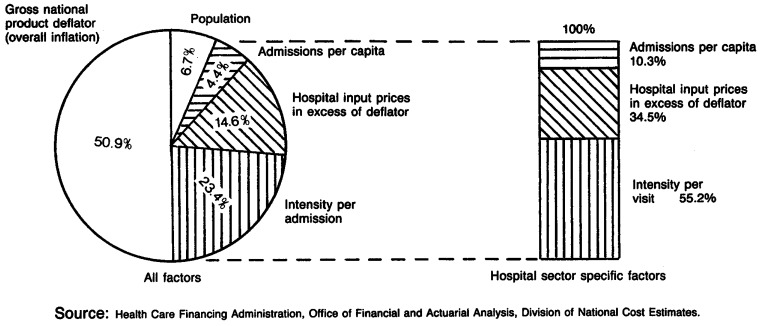

Total spending is projected to increase at an average annual rate of close to 9 percent for the projected period (1983-90), down substantially from the 13 percent rate for the historical period 1973-83 (Table 6). The four factors accounting for the historical growth rate are: growth in economy-wide inflation (as measured by GNP deflator), 58 percent; health sector prices in excess of economy-wide inflation, 11 percent; population, 8 percent; and real expense per capita (“intensity”), 23 percent (Table 7).

Table 7. Factors accounting for growth in expenditures for selected categories of national health expenditures, 1973-831, 2.

| Factors accounting for how medical care expenditures rise | Community hospital care | Physicians' services | Dentists' services | Nursing home care excluding ICFMR | Total personal health care | Total national health expenditures | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Inpatient expenses2 | Outpatient expenses2 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Inpatient days | Admissions | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Percent distribution | ||||||||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Economy-wide factors | ||||||||

| General inflation | 50.9 | 50.9 | 42.3 | 55.8 | 59.7 | 54.7 | 57.1 | 58.2 |

| Aggregate population growth | 6.7 | 6.7 | 5.6 | 7.4 | 7.9 | 7.2 | 7.6 | 7.7 |

| Health-sector specific factors | ||||||||

| Growth in per capita visits or patient days | 0.3 | 4.4 | 12.5 | -6.1 | 5.1 | 13.6 | N/A | N/A |

| Growth in real services per visit or per day (intensity) | 27.5 | 23.4 | 27.5 | 25.7 | 20.3 | 15.8 | 322.5 | 23.5 |

| Medical care price increases in excess of general price inflation (GNP deflator) | 14.6 | 14.6 | 12.1 | 17.2 | 7.0 | 8.7 | 12.8 | 10.6 |

For derivation of the method used to allocate factors, see Klarman, et al. (1970).

Community hospital expenses are split into inpatient and outpatient expenses using the American Hospital Association procedure.

Due to data limitations, this is growth in real services per capita.

NOTES:

N/A = Not available.

ICFMR = Intermediate care facility for the mentally retarded.

GNP = Gross national product.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Division of National Cost Estimates.

A projected significant decline in the general inflation rate leading to lower health care price increases will exert substantial downward pressure on health spending for the remainder of the 1980's. However, assumed robust increases in real GNP will exert an upward pressure, as will the aging population and the introduction of new cost-increasing, health-enhancing technologies. Restrained growth in Government financing of health care, including the Medicare PPS, will exert downward pressure. The net effect of these pressures and constraints will be a deceleration in the growth of health spending.

For the long-term, the ratio of health spending to GNP is projected to increase at an average annual rate of only 0.6 percent or one-fifth as fast as in the 1965-83 period.

As the economy rebounds in 1984, and as the effect of current-law reimbursement reform (e.g., the Medicare PPS) and private sector initiatives take hold, we expect the health sector's share of GNP to decline from 10.8 percent in 1983 to 10.5 percent in 1985. A relatively gradual increase in this share is projected for the remainder of the 1980's, reaching over 11 percent in 1990. Health care can be expected to be a higher percent of GNP if the relatively fast growth in projected real GNP (Table 1) does not materialize.

Over the period 1979-83, current dollar GNP increased nearly 37 percent; whereas, national health expenditures increased 65 percent (Table 8). This rapid growth in spending for health care, relative to our ability to pay, was a factor which prompted Congress, States, and private industry to develop cost-containment initiatives. Health care markets and institutions are adjusting to these revised financial incentives in the 1980's.

Table 8. Annual percent change in current dollar gross national product, health care spending, and Medicare benefit payments, 1980-83.

| Item | Percent change from previous year | Cumulative percent growth 1979-83 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | ||

| Gross national product | 8.8 | 12.4 | 3.8 | 7.7 | 36.7 |

| National health expenditures | 15.3 | 15.2 | 12.8 | 10.3 | 65.3 |

| Community hospital inpatient services | 17.5 | 18.5 | 16.1 | 9.6 | 77.3 |

| Total Medicare benefit payments | 21.7 | 21.7 | 17.6 | 12.4 | 95.9 |

| Medicare hospital benefit payments | 21.9 | 21.2 | 17.1 | 10.0 | 90.3 |

| Medicare physician benefit payments | 21.4 | 23.0 | 17.1 | 17.6 | 105.7 |

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Division of National Cost Estimates.

Shifts from the historical trends for relative shares of health spending going to various types of goods and services will occur. Reforms in payment systems for hospital care and increasing competition from ambulatory services will result in deceleration of spending growth for hospital care relative to other services. The hospital share is projected to remain relatively constant rather than to grow, as was historically the case. In 1985, the hospital share of spending is projected to be below its 1983 position.

Government financing

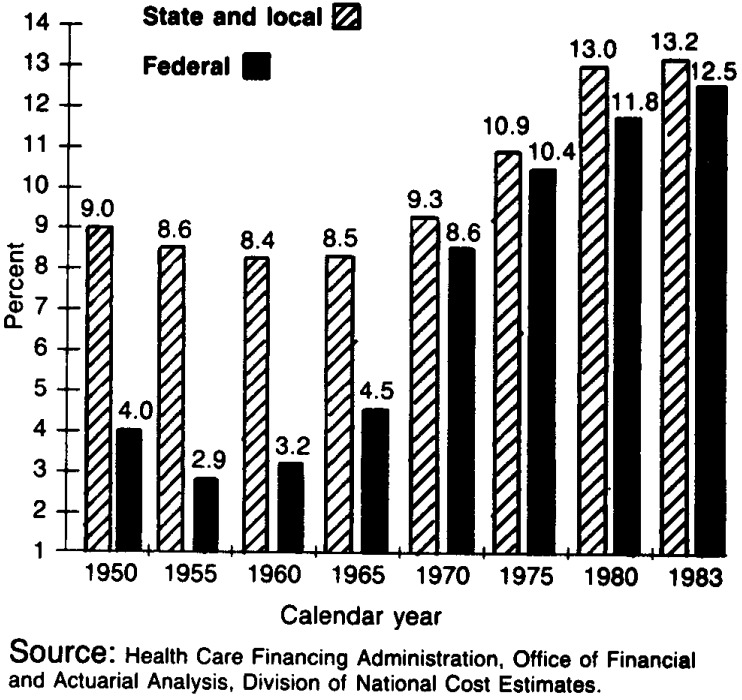

In 1983, the Federal share of health spending was 29 percent (Table 6), having increased more than 4 percentage points since 1973. The Federal share is projected to be more than 30 percent in 1985, and almost 32 percent in 1990. The gradual rise in Federal share reflects primarily the aging of the population and private sector initiatives to restrain growth in private spending. Federal outlays for national health expenditures, which were $1.6 billion in 1950, increased to $25 billion in 1973 and $ 103 billion in 1983 (Table 6). Health care outlays are becoming a larger portion of Federal spending. Federally-financed health expenditures comprised between 4 and 5 percent of total Federal Government expenditures in 1965 (pre-Medicare and Medicaid); by 1983, this percentage rose to over 12 percent (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Government expenditures for health as a percent of total government expenditures: Selected years 1950-83.

The near-term outlook has Federal expenditures rising to $128 billion in 1985, an increase of 24 percent over 1983. Federal outlays for national health expenditures are estimated to increase at an average annual rate of 11 percent from 1983-90, a rate substantially below the 15 percent rate for the 1973-83 period, but above the growth rate for total national health expenditures (Table 6). We project that Federal expenditures will reach $ 171 billion by 1988 and $209 billion by 1990.

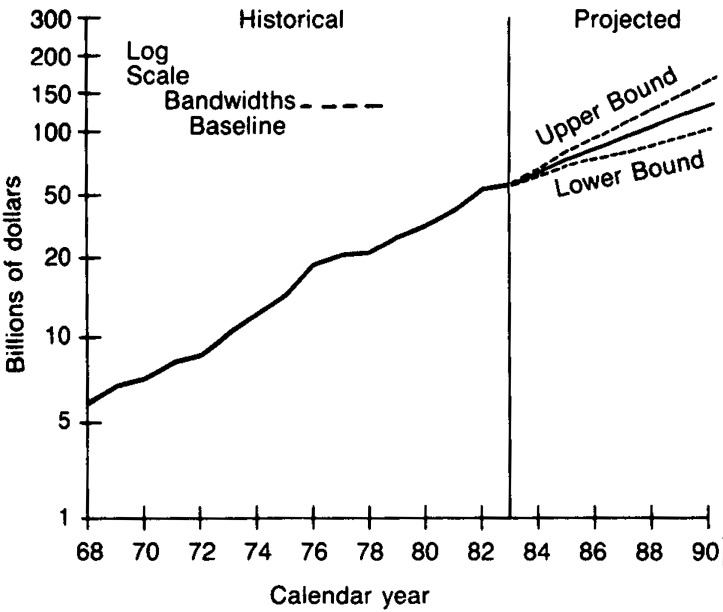

Medicare expenditures of $59 billion in 1983 (Table 4) comprised 57 percent of total Federal outlays for health care in 1983, compared to 40 percent in 1973. By 1990, Medicare is projected to account for 63 percent of Federal outlays for health care. In 1967 (the first full year of the Medicare program), total Medicare outlays were $4.7 billion, and these outlays increased at an average annual rate of 17 percent between 1967 and 1983, compared to an average annual increase of 13 percent for national health expenditures. By 1990, Medicare outlays are expected to reach $ 131 billion (Figure 3 and Table 4), increasing at an average annual rate of 12 percent for the 1983-90 period. The GNP is projected to increase at an average annual rate of between 8 and 9 percent during this interval (Table 6). Thus, Medicare outlays represent an ever-increasing share of the real resources in the economy, and will finance an increasing share of national health expenditures, even under the PPS. This is expected, since the elderly population is growing three times faster than the population under 65 years of age (Table 2).

Figure 3. Medicare outlays with bandwidths: 1968-90 1 2.

1Outlays include benefits plus administrative expenses.

2The conditional bandwidths around the baseline projection scenario provide one indicator of variability. The standard error associated with annual percent increases in Medicare outlays (for 1969-83 was multiplied by a t-distribution value of 2.145 to derive the conditional “95 percent” bandwidths. The calculated bandwidths are approximate and are used as a rough guide in assessing variability and uncertainty. It is important to keep in mind the potential dangers of extrapolating historical measures of variability into the future; that is, there can be no assurance that future variability will replicate historical variability.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of Financial and Acuarial Analysis, vision of National Cost Estimates.

Total Medicare outlays (including administrative expenses) are projected to reach $76 billion by 1985, $105 billion by 1988, and $131 billion by 1990.

Under the Midsession Review assumptions incorporated in this projection, the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund is expected to be able to finance total outlays until approximately 1990.

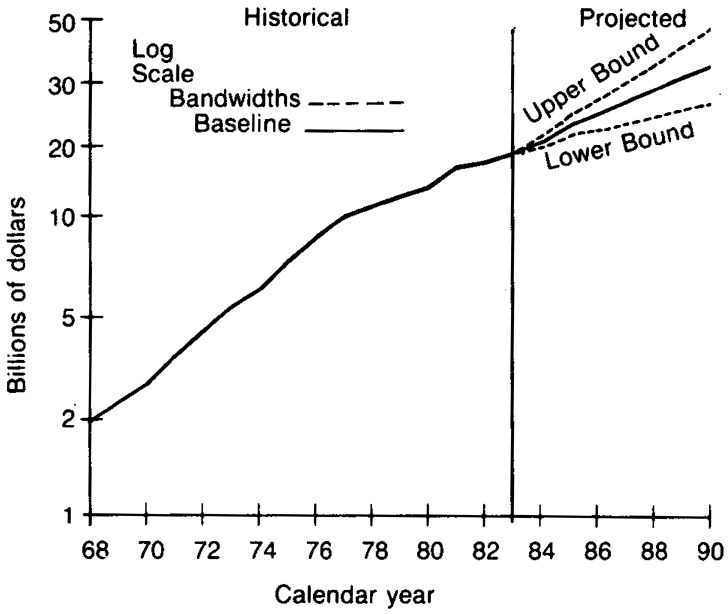

Federal Medicaid outlays (benefits plus administrative expenses) were $19 billion in 1983, compared to $5.5 billion in 1973 (Table 5), having increased at an average annual rate of increase of more than 13 percent. Federal Medicaid outlays are projected to reach $23 billion in 1985, $30 billion in 1988, and $36 billion in 1990 (Figure 4 and Table 5). These outlays are projected to increase at an average annual rate of approximately 9 percent over the period 1983-90, a rate approximately one-third lower than the 13 percent rate for the 1973-83 period. This is principally due to the assumption of lower inflation.

Figure 4. Federal Medicaid outlays with bandwidths: 1968-90 1,2.

1Outlays include benefits plus administrative expenses.

2The conditional bandwidths around the baseline projection scenario provide one indicator of variability. The standard error associated with annual percent increases in Medicare outlays (for 1969-83 was multiplied by a t-distribution value of 2.145 to derive the conditional “95 percent” bandwidths. The calculated bandwidths are approximate and are used as a rough guide in assessing variability and uncertainty. It is important to keep in mind the potential dangers of extrapolating historical measures of variability into the future; that is, there can be no assurance that future variability will replicate historical variability.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of Financial and Acuarial Analysis, vision of National Cost Estimates.

State and locally financed health expenditures were 8 to 9 percent of total State and local government expenditures for the years 1950-70 (Figure 3). By 1983, this percent had risen to over 13 percent, forcing States to economize and reorder priorities. State and local government expenditures as a percent of national health expenditures reached a peak of 14.5 percent in 1975, and declined to a 13 percent share in 1983. The State and local share of spending is projected to drop slightly between 1983 and 1990 to approximately 12 percent.

Private financing

The private sector financed 58 percent of expenditures in 1983, and this share is projected to be relatively stable over the projection interval (1983-90). Private expenditures for health care are projected to reach $240 billion by 1985 and $376 billion by 1990. For the period 1983-90, private expenditures are estimated to increase at an average annual rate of approximately 9 percent, down substantially from the 12 percent rate for the 1973-83 period.

Private health insurance premiums comprise 58 percent of total private funding for national health care.4 Premiums have risen from $25 billion in 1973 to $111 billion in 1983, more than a four-fold increase in only 10 years (Table 9). Premiums are projected to increase to $128 billion in 1985, $170 billion in 1988, and $207 billion in 1990.

Table 9. National health expenditures, by type of expenditure and source of funds: Selected years, 1973-90.

| Type of expenditure | Total | Private | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Total | Consumer | Other1 | Public | ||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

| Total | Patient direct | Health insurance | Total | Federal | State and local | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Amount in billions | |||||||||

| 1973 Total | $103.4 | $64.0 | $58.0 | $33.3 | $24.7 | $6.0 | $39.4 | $25.2 | $14.2 |

| Health services and supplies | 96.5 | 60.7 | 58.0 | 33.3 | 24.7 | 2.7 | 35.8 | 22.8 | 13.0 |

| Personal health care | 89.0 | 56.8 | 54.7 | 33.3 | 21.4 | 2.2 | 32.1 | 21.1 | 11.1 |

| Hospital care | 38.9 | 18.4 | 17.0 | 3.9 | 13.1 | 1.4 | 20.6 | 13.7 | 6.9 |

| Physicians' services | 19.1 | 14.6 | 14.7 | 7.8 | 6.9 | (3) | 4.5 | 3.1 | 1.4 |

| Dentists' services | 6.5 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 5.7 | .5 | — | .3 | .2 | .1 |

| Other professional services | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.3 | .4 | (3) | .3 | .2 | .1 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 10.1 | 9.3 | 9.3 | 8.8 | .5 | — | .8 | .4 | .4 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.3 | (3) | — | .1 | .1 | (3) |

| Nursing home care | 7.2 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.5 | (3) | (3) | 3.6 | 2.0 | 1.6 |

| Other health services | 2.7 | .7 | — | — | — | .7 | 1.9 | 1.3 | .6 |

| Program administration and net cost of insurance | 5.3 | 3.9 | 3.4 | — | 3.4 | .5 | 1.5 | .9 | .6 |

| Government public health activities | 2.2 | — | — | — | — | — | 2.2 | .9 | 1.3 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 6.8 | 3.2 | — | — | — | 3.2 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 1.1 |

| Research2 | 2.5 | .2 | — | — | — | .2 | 2.2 | 2.0 | .2 |

| Construction | 4.3 | 3.0 | — | — | — | 3.0 | 1.3 | .3 | .9 |

| 1983 Total | 355.4 | 206.6 | 195.7 | 85.2 | 110.5 | 10.9 | 148.8 | 102.7 | 46.1 |

| Health services and supplies | 340.1 | 199.8 | 195.7 | 85.2 | 110.5 | 4.1 | 140.3 | 96.8 | 43.5 |

| Personal health care | 313.3 | 188.8 | 185.2 | 85.2 | 100.0 | 3.6 | 124.5 | 93.0 | 31.5 |

| Hospital care | 147.2 | 68.8 | 67.3 | 11.1 | 56.2 | 1.5 | 78.4 | 60.6 | 17.8 |

| Physicians' services | 69.0 | 49.7 | 49.7 | 19.6 | 30.1 | (3) | 19.3 | 15.6 | 3.7 |

| Dentists' services | 21.8 | 21.2 | 21.3 | 13.9 | 7.4 | — | .6 | .3 | .3 |

| Other professional services | 8.0 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 3.3 | 2.1 | .1 | 2.4 | 1.9 | .5 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 23.7 | 21.6 | 21.6 | 18.4 | 3.2 | — | 2.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 6.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 4.5 | .7 | — | 1.0 | .9 | .1 |

| Nursing home care | 28.8 | 14.9 | 14.7 | 14.4 | .3 | .2 | 14.0 | 8.1 | 5.9 |

| Other health services | 8.5 | 1.8 | — | — | — | 1.8 | 6.6 | 4.5 | 2.1 |

| Program administration and net cost of insurance | 15.6 | 10.9 | 10.5 | — | 10.5 | .5 | 4.6 | 2.6 | 2.0 |

| Government public health activities | 11.2 | — | — | — | — | — | 11.2 | 1.2 | 10.0 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 15.3 | 6.9 | — | — | — | 6.9 | 8.5 | 5.9 | 2.6 |

| Research2 | 6.2 | .4 | — | — | — | .4 | 5.8 | 5.2 | .6 |

| Construction | 9.1 | 6.5 | — | — | — | 6.5 | 2.7 | .7 | 2.0 |

| 1985 Total | $419.5 | $240.0 | $227.6 | $99.9 | $127.6 | $12.4 | $179.6 | $127.6 | $51.9 |

| Health services and supplies | 402.4 | 232.3 | 227.6 | 99.9 | 127.6 | 4.8 | 170.0 | 120.6 | 49.5 |

| Personal health care | 372.8 | 221.8 | 217.6 | 99.9 | 117.7 | 4.3 | 150.9 | 116.2 | 34.7 |

| Hospital care | 170.6 | 76.2 | 74.5 | 11.0 | 63.4 | 1.8 | 94.4 | 75.6 | 18.8 |

| Physicians' services | 83.9 | 60.4 | 60.4 | 23.9 | 36.5 | .1 | 23.5 | 19.3 | 4.2 |

| Dentists' services | 27.3 | 26.6 | 26.6 | 17.2 | 9.4 | — | .7 | .4 | .3 |

| Other professional services | 9.8 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 3.3 | 2.7 | (3) | 3.7 | 3.0 | .7 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 28.1 | 25.6 | 25.6 | 21.3 | 4.3 | — | 2.5 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 7.6 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 5.2 | 1.0 | — | 1.5 | 1.4 | .1 |

| Nursing home care | 34.6 | 18.7 | 18.5 | 18.1 | .4 | .2 | 15.9 | 9.4 | 6.5 |

| Other health services | 10.8 | 2.1 | — | — | — | 2.1 | 8.7 | 5.9 | 2.8 |

| Program administration and net cost of insurance | 15.8 | 10.5 | 10.0 | — | 10.0 | .5 | 5.3 | 3.1 | 2.2 |

| Government public health activities | 13.8 | — | — | — | — | — | 13.8 | 1.3 | 12.5 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 17.2 | 7.7 | — | — | — | 7.7 | 9.5 | 7.0 | 2.5 |

| Research2 | 7.3 | .4 | — | — | — | .4 | 6.9 | 6.2 | .7 |

| Construction | 9.9 | 7.3 | — | — | — | 7.3 | 2.6 | .8 | 1.8 |

| 1988 Total | 552.4 | 316.7 | 301.0 | 131.1 | 169.9 | 15.7 | 235.7 | 170.8 | 64.8 |

| Health services and supplies | 531.5 | 307.2 | 301.0 | 131.1 | 169.9 | 6.2 | 224.3 | 162.4 | 61.9 |

| Personal health care | 493.3 | 293.3 | 287.7 | 131.1 | 156.7 | 5.5 | 200.0 | 157.7 | 42.3 |

| Hospital care | 228.8 | 104.3 | 102.0 | 17.3 | 84.6 | 2.4 | 124.5 | 102.1 | 22.3 |

| Physicians' services | 110.0 | 77.1 | 77.0 | 29.5 | 47.6 | (3) | 32.9 | 27.9 | 5.0 |

| Dentists' services | 35.2 | 34.5 | 34.5 | 22.1 | 12.3 | — | .7 | .4 | .3 |

| Other professional services | 12.9 | 8.4 | 8.3 | 4.5 | 3.9 | .1 | 4.5 | 3.6 | .9 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 36.2 | 33.2 | 33.2 | 26.9 | 6.3 | — | 3.0 | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 9.7 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 6.0 | 1.4 | — | 2.3 | 2.1 | .1 |

| Nursing home care | 46.2 | 25.7 | 25.3 | 24.8 | .5 | .3 | 20.6 | 12.3 | 8.2 |

| Other health services | 14.1 | 2.7 | — | — | — | 2.7 | 11.4 | 7.7 | 3.7 |

| Program administration and net cost of insurance | 19.9 | 13.9 | 13.3 | — | 13.3 | .7 | 5.9 | 3.3 | 2.5 |

| Government public health activities | 18.4 | — | — | — | — | — | 18.4 | 1.4 | 17.0 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 20.9 | 9.4 | — | — | — | 9.4 | 11.4 | 8.4 | 2.9 |

| Research2 | 8.8 | .4 | — | — | — | .4 | 8.3 | 7.5 | .8 |

| Construction | 12.1 | 9.0 | — | — | — | 9.0 | 3.1 | .9 | 2.1 |

| 1990 Total | $660.1 | $375.7 | $357.9 | $150.6 | $207.3 | $17.9 | $284.5 | $208.6 | $75.9 |

| Health services and supplies | 637.0 | 365.1 | 357.8 | 150.6 | 207.3 | 7.3 | 271.9 | 199.2 | 72.7 |

| Personal health care | 588.5 | 344.7 | 338.2 | 150.6 | 187.7 | 6.5 | 243.8 | 194.3 | 49.5 |

| Hospital care | 277.4 | 126.5 | 123.7 | 21.1 | 102.6 | 2.9 | 150.9 | 125.3 | 25.6 |

| Physicians' services | 129.1 | 88.0 | 87.9 | 32.1 | 55.9 | .1 | 41.1 | 35.3 | 5.8 |

| Dentists' services | 40.5 | 39.7 | 39.7 | 25.4 | 14.3 | — | .8 | .4 | .4 |

| Other professional services | 15.3 | 9.7 | 9.6 | 4.9 | 4.7 | .1 | 5.6 | 4.4 | 1.2 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 42.4 | 39.0 | 39.0 | 31.2 | 7.8 | — | 3.4 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 11.3 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 6.6 | 1.8 | — | 2.9 | 2.7 | .2 |

| Nursing home care | 55.1 | 30.3 | 30.0 | 29.3 | .7 | .4 | 24.7 | 14.8 | 9.9 |

| Other health services | 17.4 | 3.1 | — | — | — | 3.1 | 14.3 | 9.6 | 4.7 |

| Program administration and net cost of insurance | 26.8 | 20.4 | 19.6 | — | 19.6 | .8 | 6.4 | 3.5 | 2.9 |

| Government public health activities | 21.7 | — | — | — | — | — | 21.7 | 1.4 | 20.3 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 23.1 | 10.6 | — | — | — | 10.6 | 12.6 | 9.3 | 3.2 |

| Research2 | 9.7 | .5 | — | — | — | .5 | 9.3 | 8.4 | .9 |

| Construction | 13.4 | 10.1 | — | — | — | 10.1 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 2.3 |

Spending by philanthropic organizations, industrial in-plant health services and privately financed construction.

Research and development expenditures of drug companies and other manufacturers and providers of medical equipment and supplies are excluded from “research expenditures,” but are included in the expenditure class in which the product falls.

Less than $50 million.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Division of National Cost Estimates.

The employer share of private health insurance premiums has been increasing as a portion of employee compensation. Such premiums have risen at an average annual rate of 16 percent over the period 1973-83, reaching $82 billion in 1983 (Table 10). Employers also make contributions to the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund and these contributions have risen from $5.3 billion in 1973 to $18.5 billion in 1983, an average annual rate of increase of over 13 percent. During this same period, total employee compensation increased at an average rate of between 9 and 10 percent, with an increased share allocated to health insurance. In 1950, the employer contribution to group health insurance was one half of one percent of total employee compensation. By 1973, this share, adjusted to include the contributions to the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, was 2.9 percent, and in 1983, the share had risen to 5.1 percent (Table 10).

Table 10. Employer contributions for health insurance and total employee compensation: Selected years, 1950-83.

| Calendar year | Employer contributions for health insurance | Employee compensation | Contributions for health insurance as percent of total compensation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| Private health insurance premiums | Federal hospital insurance, Medicare | Total | Wages and salaries | Supplements to wages and salaries | Total | ||

| Amount in billions | |||||||

| 1950 | $0.7 | (1) | $0.7 | $147.0 | $7.8 | $154.8 | 0.5 |

| 1955 | 1.7 | (1) | 1.7 | 211.7 | 13.2 | 224.9 | 0.8 |

| 1960 | 3.4 | (1) | 3.4 | 271.9 | 23.0 | 294.9 | 1.2 |

| 1965 | 5.9 | (1) | 5.9 | 362.0 | 34.5 | 396.5 | 1.5 |

| 1970 | 12.1 | $2.3 | 14.4 | 548.7 | 63.2 | 612.0 | 2.4 |

| 1973 | 18.0 | 5.3 | 23.3 | 702.6 | 98.7 | 801.3 | 2.9 |

| 1975 | 24.0 | 5.6 | 29.6 | 806.4 | 125.0 | 931.4 | 3.2 |

| 1979 | 44.2 | 10.6 | 54.8 | 1,237.4 | 220.7 | 1,458.1 | 3.8 |

| 1980 | 49.8 | 11.6 | 61.4 | 1,356.6 | 243.0 | 1,599.6 | 3.8 |

| 1981 | 58.9 | 15.9 | 74.8 | 1,493.2 | 272.2 | 1,765.4 | 4.2 |

| 1982 | 69.7 | 16.6 | 86.3 | 1,568.7 | 295.5 | 1,864.2 | 4.6 |

| 1983 | 82.0 | 18.5 | 100.5 | 1,658.8 | 326.2 | 1,984.9 | 5.1 |

| Average annual percent change | |||||||

| 1973-83 | 16.4 | 13.4 | 15.8 | 9.0 | 12.7 | 9.5 | 5.8 |

Not applicable.

SOURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis (1981, 1984).

The increasing cost of employer-paid health costs relative to total compensation has led to numerous private sector initiatives to reduce the rate of increase of health care costs. Employers increasingly include cost-containment features in their group coverages (Tell, Falik, and Fox, 1984). In one recent survey of new group policies, 79 percent of the employees had provision for reimbursing for prescriptions on generic basis, 76 percent had coverage for second opinions on surgery, 85 percent provided for preadmission testing and for outpatient surgery (Health Insurance Association of America, 1983). Employers are also increasing use of HMO's and self-funding of health benefits (Arnett and Trapnell, 1984; Cain, 1983; Harker, 1981). Major reasons for self-funding are: elimination of State premium taxes averaging 2 to 3 percent of premiums; improved cash flow (a one shot, temporary factor); higher interest rate earned on reserves held to pay benefits; and the availability of third-party administrators, many of whom claim to be able to monitor and control costs more effectively than traditional insurers (Moore, 1984).

International experience

Relatively high rates of growth in health care expenditures, historical and projected, are not unique to the United States (Predicasts, Inc., 1983). Economy-wide inflation, growth in real income, demographic shifts, and cost-increasing product-innovative technologies, have been associated with rising health care costs in selected western industrialized countries that have been studied (Poullier, 1985; Sandier, 1983; Simanis, 1985; Simanis and Coleman, 1980; Smith, 1984). The pervasiveness and extensiveness of the worldwide rises in health care spending relative to GNP have implications for understanding historical increases in U.S. spending and for anticipating future spending patterns.

In a recent study (Simanis, 1985) in which the latest data available were for 1980, the United States is among the highest when ranked according to the percent of GNP spent on health care, following Sweden and the Federal Republic of Germany (Table 11). Another study (Poullier, 1985) indicates that by 1982, the United States spent a higher proportion of its income on health than any country in the western industrialized world.

Table 11. National health expenditures in seven industrialized countries as a percent of gross national product: Selected years, 1960-801.

| Country | National health expenditures as percent of gross national product | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 1960 | 1965 | 1970 | 1975 | 1980 | |

| Sweden | 3.5 | 5.8 | 7.5 | 8.7 | 9.7 |

| Federal Republic of Germany | 4.4 | 5.2 | 6.1 | 9.7 | 9.6 |

| United States2 | 5.3 | 6.1 | 7.6 | 8.6 | 9.4 |

| France | 5.0 | 5.9 | 6.6 | 8.1 | 8.9 |

| Netherlands | N/A | 5.0 | 6.3 | 8.6 | 8.9 |

| Canada | 5.6 | 6.1 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 7.4 |

| United Kingdom | 3.8 | 3.9 | 4.9 | 5.6 | 5.8 |

Simanis and Coleman (1980) for 1960-75. Simanis (1985) for 1980. Data for 1980 are preliminary and subject to revision.

In the United Kingdom, the percent of GNP attributed to health is significantly lower than the other countries in the Simanis study (Table 11). This has been accomplished, in part, through rationing of services and paying relatively lower wages to health sector personnel than some other countries (Aaron and Schwartz, 1984).

International growth in health care spending is highly correlated with increases in income (Newhouse, 1977; Poullier, 1985), and income appears to be a more important determinant of growth than sources of funding (Government vs. private) (Kleiman, 1974). Nations have financed these spending increases with different mixes of private and Government spending, but the result has generally been the same. Higher incomes typically result in additional spending on health relative to the GNP. As health care garners an ever-increasing share of national incomes around the world, the nature of care appears to be shifting toward care that emphasizes the “caring” function, rather than the “curing” function (Newhouse, 1977).

The international diffusion of medical equipment, supplies and drugs (Bandy, 1984; Mclntyre, 1984; Poullier, 1985), combined with diffusion of biomedical research results and reimbursement methodologies, leads to potential linkages in medical practice styles and expenditure patterns in the western industrialized world and Japan. The extent to which convergence among nations in medical practice styles is occurring because of this diffusion is difficult to ascertain, however. In this regard, it is noteworthy that in Europe and Japan, as in the United States, there does seem to be substantial interest in using diagnosis related groups as a management tool (Fetter and Freeman, 1984; Ohmich, 1984; and Sanderson, 1984).

Some analysts of international health care spending suggest that health spending as a proportion of GNP tends to grow in spurts. Nations implicitly or explicitly make judgments as to the “correct” ratio of GNP or public expenditures allocated to health care (Perspective, 1982). Several western industrialized countries have recently modified and restricted social programs covering the health sector due to the excessive burden on public sector financing during sluggish economic growth (Poullier, 1985). One study forecasts that health-spending increases in the developed world will slow in the 1980's as cost-effective changes in health delivery systems and finance are incorporated (Predicasts, Inc., 1983).

Projection trends by type of health expenditure

Hospital care

The financial incentives for hospitals are changing more significantly now than at any time since the enactment of Medicare, because both public– and private-sector payers are instituting mechanisms to control the rise of health care costs. In the private sector, insurers and benefit administrators are more closely examining hospital bills and procedures. Cost-saving provider arrangements such as Preferred Provider Organizations (PPO), copayment on more services, higher deductibles, payment for second opinions, outpatient testing, and the use of ambulatory surgery are all being encouraged.

In the public sector, the prospective payment system (PPS) is having direct implications for community hospital inpatient services, and indirect effects on health care services other than Medicare inpatient. The PPS changed inpatient hospital service reimbursement from a cost-based retrospective system to a prospectively set payment, based on 467 diagnostically-related groups. The intent of the law was to restructure hospital economic incentives, associate a fixed payment with product/service purchase, and limit growth in outflows from the Medicare Trust Funds.

The changing hospital environment is characterized by increasing pressure by public and private payers to reduce the rate of increase of hospital costs, and an increasingly competitive marketplace. Hospitals have increasingly diversified by forward integration into ambulatory care and a backward integration into aftercare, such as nursing-home care and home-health services.

The PPS severs the relationship between Medicare revenues to hospitals and the expenses incurred to treat Medicare patients. With this revised financial incentive, Medicare outlays are projected to increase at a slower rate than would otherwise be expected. Increases in input intensity of services per admission have been an important factor in accounting for the growth in inpatient expenditures. For example, more than 23 percent of inpatient expenditure growth and more than 52 percent of hospital-specific expenditure growth in the period 1973-83 were accounted for by the rise in input intensity per admission. (Figure 5 and Table 8). Growth in input intensity–per–dis-charge of approximately 3 percent annually pre-PPS is significantly slowed in the projection period (1983–90). Also, under PPS hospitals have an incentive to increase productivity and to adopt more cost–effective practice patterns. Under increased productivity, real output intensity per admission rises faster than real input intensity.

Figure 5. Factors accounting for growth in expenditures for community hospital inpatient care: 1973-83.

Highlights of projections for hospital care follow:

Total hospital expenditures are projected to rise from $147 billion in 1983 to $171 billion in 1985, $229 billion in 1988, and $277 billion in 1990 (Table 12).

Substantially lower rates of increase are projected for Medicare benefit payments (inpatient and outpatient) through the remainder of the 1980's; 12 percent in the projected period, compared to 19 percent during 1973-83.

Spending for community hospital inpatient services is projected to decelerate significantly in the projected period, increasing at an average annual rate of less than 10 percent, compared to 15 percent or more for the period 1973-83.

Revenue for community inpatient services is expected to exceed $200 billion in 1990, rising from $109 billion in 1983 to $125 billion in 1985, $168 billion in 1988, and $204 billion in 1990.

The deceleration in hospital growth results primarily from slowing of economy-wide inflation, restraints in inpatient reimbursement under PPS, intensified competition, and increasing use of nonhospital alternate sites for delivery of care. Countervailing forces which result in growth in this sector include an aging population, new technology, and increased ability to pay. The net result is that this sector, while slowing, is still projected to grow at a faster rate than the gross national product for the period as a whole.

Expenses per inpatient stay tripled from $784 in 1973 to $2,742 in 1983, and are projected to double by 1990 to more than $5,100.

Increasing alternate sites for delivery of care and the changing hospital marketplace result in the projection of declining average annual growth in admissions of-0.2 percent over the 1983-90 interval, compared to an average annual increase of 1.6 percent in the 1973-83 period.

Intensity of services per admission is projected to grow at an average annual rate of 2-3 percent. This is substantially slower than for the historical period 1973-83.

Length of stay is projected to shorten under PPS. This tends to increase average intensity per day, because most ancillary services are provided near the beginning of an admission.

Table 12. National health expenditures, by type of expenditure: Selected years, 1950-90.

| Type of expenditure | 1950 | 1955 | 1960 | 1965 | 1970 | 1973 | 1975 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1985 | 1988 | 1990 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Amount in billions | |||||||||||||||

| Total | $12.7 | $17.7 | $26.9 | $41.9 | $75.0 | $103.4 | $132.7 | $215.1 | $248.0 | $285.8 | $322.3 | $355.4 | $419.5 | $552.4 | $660.1 |

| Health services and supplies | 11.7 | 16.9 | 25.2 | 38.4 | 69.6 | 96.5 | 124.3 | 204.6 | 236.1 | 272.7 | 308.1 | 340.1 | 402.4 | 531.5 | 637.0 |

| Personal health care | 10.9 | 15.7 | 23.7 | 35.9 | 65.4 | 89.0 | 117.1 | 189.6 | 219.1 | 253.4 | 284.7 | 313.3 | 372.8 | 493.3 | 588.5 |

| Hospital care | 3.9 | 5.9 | 9.1 | 14.0 | 28.0 | 38.9 | 52.4 | 87.0 | 101.3 | 117.9 | 134.9 | 147.2 | 170.6 | 228.8 | 277.4 |

| Physicians' services | 2.7 | 3.7 | 5.7 | 8.5 | 14.3 | 19.1 | 24.9 | 40.2 | 46.8 | 54.8 | 61.8 | 69.0 | 83.9 | 110.0 | 129.1 |

| Dentists' services | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 4.7 | 6.5 | 8.2 | 13.3 | 15.4 | 17.3 | 19.5 | 21.8 | 27.3 | 35.2 | 40.5 |

| Other professional services | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 4.7 | 5.6 | 6.4 | 7.1 | 8.0 | 9.8 | 12.9 | 15.3 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 1.7 | 2.4 | 3.7 | 5.2 | 8.0 | 10.1 | 11.9 | 17.1 | 18.5 | 20.5 | 21.8 | 23.7 | 28.1 | 36.2 | 42.4 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 6.2 | 7.6 | 9.7 | 11.3 |

| Nursing home care | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 4.7 | 7.2 | 10.1 | 17.4 | 20.4 | 23.9 | 26.5 | 28.8 | 34.6 | 46.2 | 55.1 |

| Other health services | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 3.8 | 5.1 | 5.9 | 7.0 | 7.6 | 8.5 | 10.8 | 14.1 | 17.4 |

| Program administration and net cost of insurance | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 5.3 | 4.0 | 8.6 | 9.2 | 10.6 | 13.4 | 15.6 | 15.8 | 19.9 | 26.8 |

| Government public health activities | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 6.4 | 7.7 | 8.6 | 10.0 | 11.2 | 13.8 | 18.4 | 21.7 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 3.5 | 5.4 | 6.8 | 8.4 | 10.4 | 11.9 | 13.2 | 14.2 | 15.3 | 17.2 | 20.9 | 23.1 |

| Research | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.3 | 4.7 | 5.4 | 5.6 | 5.9 | 6.2 | 7.3 | 8.8 | 9.7 |

| Construction | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 4.3 | 5.1 | 5.7 | 6.5 | 7.6 | 8.3 | 9.1 | 9.9 | 12.1 | 13.4 |

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Division of National Cost Estimates.

Community outpatient hospital services

Substantial growth in services and revenues for outpatient services is expected to continue in the projected period (1983-90). Several factors may dampen this growth, including the influence of increasing competition in the ambulatory services sector, an increasing supply of office-based physicians relative to the population, and more stringent payment associated with increased scrutiny into case-mix complexity of hospital outpatient services.

The projection outlook for outpatient services is for inflation-adjusted (real) output to increase at substantially higher rates (about 6 percent) than for community hospital inpatient services (less than 3 percent) or physicians' services (about 4 percent). Still, this is only three-fourths its rate of increase for the period 1973-83.

Federal hospital

Slower growth in Federal hospital spending is projected for 1983-90, with expenditures growing from $11 billion in 1983 to $19 billion in 1990, because of lower economy-wide inflation, more Federal hospital closures, Federal budget constraints, and the more effective linkage of payments to case-mix complexity.

Physicians' services

Physicians influence the health care industry to a greater extent than the 22 percent share of personal health spending consumed by the physicians' services sector. Blumberg (1979) estimates that physicians influence approximately 70 percent of personal health spending.

The long-term projection is for expenditures of physicians' services to increase at a substantially slower rate of less than 10 percent annually, compared to 14 percent in the last decade, 1973-83.

Physicians' fees as measured by the CPI, are projected to grow at an average annual rate of 5-6 percent for the 1983-90 period. This dampening of prices accounts, in part, for the substantial slowing in the projected growth rate of expenditures for physicians' services for the 1983-90 period.

Expenditures for physicians' services are estimated to grow from $69 billion in 1983 to $129 billion in 1990, and from approximately $285 per capita to $500 per capita.

Other factors which account for the dampening of growth rates include cost containment efforts; intensified competition between office-based physicians and alternate delivery systems, such as hospital outpatient department, HMO's, and preferred provider organizations; and increased influence of financial management on physician clinical practice patterns. Factors which contribute to projected growth for this service include growth of real income per capita; unbundling services, since total charges are usually higher when summing costs of individual services or procedures than for the bundle of services or procedures priced as a whole; and increased case-mix complexity, due, in part, to shifts in some services from the hospital to the office setting.

Dentists' services

The prevention and control of dental disease cost $22 billion in 1983. Compared to most other health services, dentists' services are subject to more consumer cost-sharing, competitive forces in the industry, and better productivity performance.

Growth in dentists' services is projected to moderate, growing at an average annual rate of 9 percent from 1983-90, compared to 13 percent for 1973-83 (Table 13).

Expenses per capita are projected to rise from $90 in 1983 to $156 in 1990, with expenditures projected at $27 billion in 1985 and $40 billion in 1990.

Table 13. National health expenditures average annual percent change, by type of expenditure: Selected periods, 1950-90.

| Type of expenditure | 1950-55 | 1955-60 | 1960-65 | 1965-70 | 1970-75 | 1975-80 | 1980-85 | 1985-90 | 1965-83 | 1973-83 | 1979-83 | 1983-90 | 1983-85 | 1983-88 | 1985-88 | 1988-90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 7.0 | 8.7 | 9.2 | 12.3 | 12.1 | 13.3 | 11.1 | 9.5 | 12.6 | 13.1 | 13.4 | 9.2 | 8.7 | 9.2 | 9.6 | 9.3 |

| Health services and supplies | 7.6 | 8.3 | 8.7 | 12.6 | 12.3 | 13.7 | 11.3 | 9.6 | 12.9 | 13.4 | 13.5 | 9.4 | 8.8 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 9.5 |

| Personal health care | 7.6 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 12.8 | 12.4 | 13.3 | 11.2 | 9.6 | 12.8 | 13.4 | 13.4 | 9.4 | 9.1 | 9.5 | 9.8 | 9.2 |

| Hospital care | 8.9 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 14.9 | 13.4 | 14.1 | 11.0 | 10.2 | 14.0 | 14.2 | 14.1 | 9.5 | 7.7 | 9.2 | 10.3 | 10.1 |

| Physicians' services | 6.1 | 9.0 | 8.3 | 11.1 | 11.7 | 13.4 | 12.4 | 9.0 | 12.4 | 13.7 | 14.4 | 9.4 | 10.3 | 9.8 | 9.4 | 8.4 |

| Dentists' services | 9.4 | 5.6 | 7.3 | 11.1 | 11.6 | 13.3 | 12.1 | 8.2 | 12.1 | 12.8 | 13.1 | 9.3 | 11.9 | 10.1 | 8.9 | 7.2 |

| Other professional services | 7.3 | 8.9 | 3.7 | 9.1 | 10.4 | 16.5 | 11.7 | 9.4 | 12.1 | 15.1 | 14.0 | 9.6 | 10.4 | 10.0 | 9.8 | 8.8 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 6.7 | 8.9 | 7.2 | 9.1 | 8.3 | 9.2 | 8.7 | 8.5 | 8.8 | 9.0 | 8.5 | 8.6 | 8.9 | 8.8 | 8.8 | 8.1 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 4.2 | 5.1 | 8.6 | 10.7 | 10.1 | 10.2 | 8.2 | 8.3 | 9.7 | 9.5 | 7.4 | 8.9 | 10.4 | 9.3 | 8.6 | 7.8 |

| Nursing home care | 10.8 | 11.0 | 31.5 | 17.8 | 16.4 | 15.2 | 11.2 | 9.8 | 15.8 | 14.9 | 13.5 | 9.7 | 9.5 | 9.9 | 10.2 | 9.2 |

| Other health services | 11.9 | 3.7 | 0.7 | 12.5 | 12.8 | 9.5 | 12.8 | 9.9 | 11.7 | 12.1 | 13.4 | 10.8 | 13.1 | 10.7 | 9.2 | 11.0 |

| Program administration and net cost of insurance | 14.6 | 6.7 | 15.1 | 10.1 | 7.2 | 18.3 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 12.9 | 11.3 | 15.9 | 8.1 | .7 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 16.1 |

| Government public health activities | 0.9 | 1.9 | 14.5 | 11.8 | 17.3 | 19.6 | 12.4 | 9.5 | 15.7 | 17.5 | 15.3 | 9.9 | 10.9 | 10.4 | 10.0 | 8.7 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | -2.2 | 14.7 | 15.0 | 9.0 | 9.2 | 7.3 | 7.6 | 6.1 | 8.5 | 8.4 | 10.0 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 5.3 |

| Research | 12.4 | 25.8 | 18.0 | 5.4 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 8.1 | 9.3 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 8.8 | 7.3 | 6.4 | 5.2 |

| Construction | -5.0 | 10.0 | 13.8 | 11.4 | 8.1 | 5.1 | 8.8 | 6.3 | 8.8 | 7.7 | 12.3 | 5.7 | 4.3 | 5.8 | 6.9 | 5.4 |

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of Financial and Actuarial Analysis, Division of National Cost Estimates.

The rate of growth in dentists' services will slow substantially, due to a slow down in economy-wide inflation and the moderating rate of increase projected for dental insurance.

Other professional services

Expenditures for other professional services (freestanding home health agencies; and optometrists, podiatrists, chiropractors, nurse practitioners, occupational and physical therapists, clinical psychologists, and the like, who are engaged in independent practice) increased at an average annual rate of 15 percent, from $2 billion to $8 billion, during the 1973-83 period.

Expenditures for other professional services are expected to rise to $ 10 billion in 1985, $ 13 billion in 1988, and $ 15 billion in 1990, with rates of real expenditures significantly exceeding both GNP and national health expenditures.

The projected long-term outlook is for other professional services to increase at an average annual rate of 9 to 10 percent. Utilization of home health services is expected to increase at relatively high rates since the Medicare PPS provides an incentive for early discharge of patients from hospitals. Some of these discharged patients will need more home health services than was previously the case.

Drugs and medical sundries

Drugs (prescription and over-the-counter) and medical sundries dispensed in retail channels comprised 8 percent of personal health spending in 1983. For recent historical periods, prices of drugs have been rising substantially faster than economy-wide inflation. In the 12 months ending October 1984, prices rose nearly 10 percent for the CPI for prescription drugs; about 7 percent for the CPI for medical care commodities (mostly drugs); about 6 percent for the CPI for internal and respiratory over-the-counter drugs; and 4 percent for overall inflation (CPI-all items). The short-term outlook is for expenditures for drugs and medical sundries to rise from $24 billion in 1983 to $28 billion in 1985, an average annual rate of increase of about 9 percent.

The long-term outlook is for drugs and medical sundries spending to increase at an average annual growth rate of nearly 9 percent. Factors leading to this growth include the aging of the population with the elderly using more prescriptions per capita, and requiring higher dosage per prescription, thus paying higher prices per prescription, the increase in real income per capita, and the introduction of new product lines of prescription drugs.

Eyeglasses and appliances

Expenditures for ophthalmic products and durable medical equipment (primarily ophthalmic products) rose at an average annual growth rate of nearly 10 percent for 1973-83, rising from less than $3 billion to more than $6 billion. Relative to most services and supply sectors, the market for ophthalmic goods is quite competitive (Benham, 1972; Feldman and Began, 1978). Direct out-of-pocket payments have accounted for most of the outlays, with third-party payers exercising a relatively small role in consumer demand. During the recession in the early 1980's, consumption of eyeglasses and durable equipment was sharply curtailed as consumers delayed purchases.

Expenditures for eyeglasses and durable medical equipment are expected to grow from about $6 billion in 1983 to nearly $8 billion in 1985.

Long-term projections assume that real consumption will rise substantially faster than real GNP, and that consumer prices for eyeglasses will continue to rise at a slower rate than economy-wide prices, based on a competitive market.

The durable medical equipment component is expected to experience robust growth as hospitals respond to the Medicare PPS by discharging patients earlier. There should be greater demand for durable medical equipment for home use, as services previously performed in the hospital setting are performed at other sites.

Nursing-home care

Nursing-home care (including intermediate care facilities for the mentally retarded (ICFMR)) has risen dramatically, from less than 2 percent of personal health care costs in 1950 to over 9 percent in 1983, reflecting expenditure growth at an average annual rate of 16 percent. This fast growth of nursing home care is due to a demographic shift toward the elderly; increases in real income; expanded Medicaid benefits, especially the addition of the ICFMR benefit in 1973 (the fastest growing component of nursing home care); increases in the number of nursing-home beds; and increases in prices paid for inputs used in the production of care.

The short-term outlook is for total nursing-home care expenditures to rise from $29 billion to $35 billion, an average annual rate of nearly 10 percent, a substantial deceleration from the 15 percent rate experienced in 1973-83.

For the longer-term, expenditures for nursing-home care are projected to rise to $46 billion in 1988 and $55 billion in 1990.

Accounting for most of the projected increase in spending is the aging of the population, with the elderly spending more than 30 times as much per capita for nursing-home care than persons under 65 years of age (Fisher, 1980). Both the development of substitute and complementary care networks (e.g., home health care services, domiciliary care, congregate housing, continuing–care retirement homes, and personal care by relatives and friends) (Freeland and Schendler, 1984; Lane, 1981) and cost–containment initiatives by all levels of Government5 contribute to projected substantial slowing in the growth of expenditures for nursing home care.

Other personal health care

Other personal health care expenditures are projected to increase at an average annual rate of growth of 11 percent from 1983 to 1990, increasing from $8.5 billion to $ 17 billion.

Program administration and net cost of insurance