Abstract

Growth in health care expenditures slowed to 9.1 percent in 1984, the smallest increase in expenditures in 19 years. Economic forces and emerging structural changes within the health sector played a role in slowing growth.

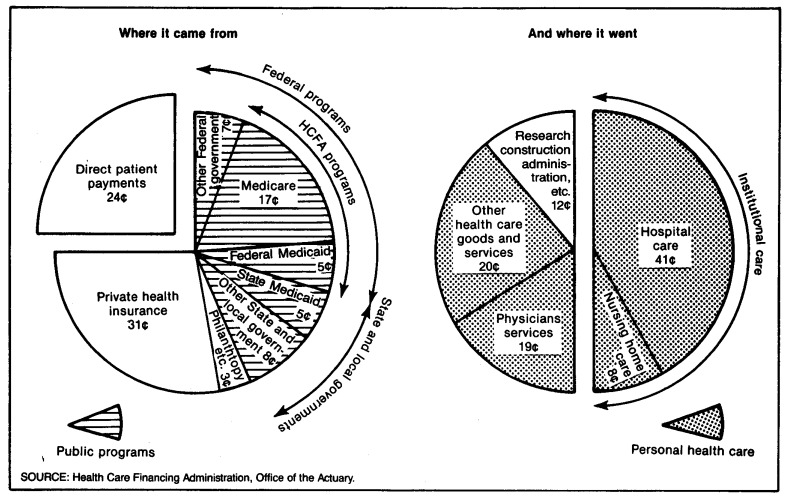

Of the $1,580 per person spent for health care in 1984, 41 percent was financed by public programs; 31 percent by private health insurance; and the remainder by other private sources. Together, Medicare and Medicaid accounted for 27 percent of all health spending.

Highlights

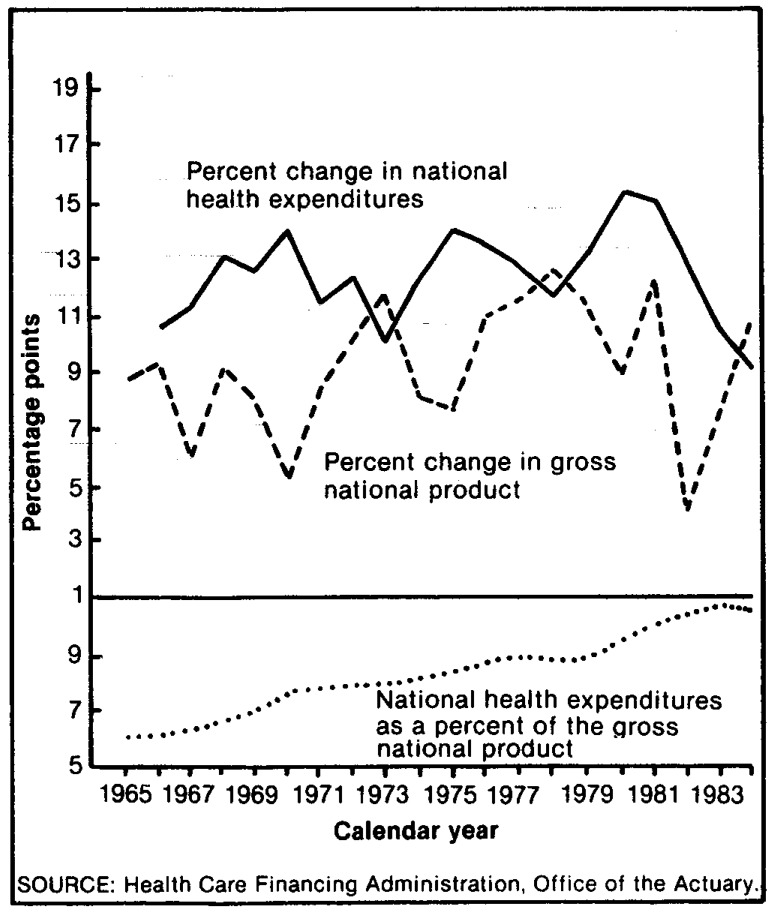

Spending for health in the United States reached $387 billion in 1984, amounting to 10.6 percent of the gross national product, down from 10.7 percent in 1983 (Table 1). Increases in expenditures slowed to 9.1 percent in 1984—the first time in 19 years that the increase has been less than 10 percent (Figure 1). Highlights of the figures that underly these statistics include the following:

Table 1. Aggregate and per capita amounts and percent distribution of national health expenditures, by source of funds: Selected calendar years 1929-84.

| Item | 1984 | 1983 | 1982 | 1980 | 1975 | 1970 | 1967 | 1965 | 1960 | 1950 | 1940 | 1929 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National health expenditures: | ||||||||||||

| In billions | $387.4 | $355.1 | $321.2 | $247.5 | $132.7 | $75.0 | $51.5 | $41.9 | $26.9 | $12.7 | $4.0 | $3.6 |

| Percent of gross national product | 10.6 | 10.7 | 10.5 | 9.4 | 8.6 | 7.6 | 6.4 | 6.1 | 5.3 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 3.5 |

| Sources of funds in billions: | ||||||||||||

| Private expenditures | $227.1 | $207.0 | $186.1 | $142.2 | $76.4 | $47.2 | 32.5 | 30.9 | 20.3 | 9.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| Public expenditures | 160.3 | 148.1 | 135.1 | 105.3 | 56.3 | 27.8 | 19.0 | 11.0 | 6.6 | 3.4 | .8 | .5 |

| Federal expenditures | 111.9 | 102.7 | 93.2 | 71.0 | 37.0 | 17.7 | 11.9 | 5.5 | 3.0 | 1.6 | (2) | (2) |

| State and local expenditures | 48.3 | 45.4 | 41.9 | 34.3 | 19.3 | 10.1 | 7.0 | 5.5 | 3.6 | 1.8 | (2) | (2) |

| Expenditures per capita1 | 1,580 | 1,461 | 1,334 | 1,049 | 591 | 350 | 248 | 207 | 146 | 82 | 30 | 29 |

| Private expenditures | 926 | 852 | 773 | 603 | 340 | 221 | 157 | 152 | 110 | 60 | 24 | 25 |

| Public expenditures | 654 | 609 | 561 | 447 | 251 | 130 | 91 | 54 | 36 | 22 | 6 | 4 |

| Federal expenditures | 457 | 423 | 387 | 301 | 165 | 83 | 57 | 27 | 16 | 10 | (2) | (2) |

| State and local expenditures | 197 | 187 | 174 | 146 | 87 | 47 | 34 | 27 | 20 | 12 | (2) | (2) |

| Percent distribution of funds | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Private funds | 58.6 | 58.3 | 57.9 | 57.4 | 57.5 | 63.0 | 63.2 | 73.8 | 75.3 | 72.8 | 79.7 | 86.4 |

| Public funds | 41.4 | 41.7 | 42.1 | 42.6 | 42.5 | 37.0 | 36.8 | 26.2 | 24.7 | 27.2 | 20.3 | 13.6 |

| Federal funds | 28.9 | 28.9 | 29.0 | 28.7 | 27.9 | 23.6 | 23.2 | 13.2 | 11.2 | 12.8 | (2) | (2) |

| State and local funds | 12.5 | 12.8 | 13.0 | 13.9 | 14.5 | 13.5 | 13.7 | 13.0 | 13.5 | 14.4 | (2) | (2) |

| Addenda: | ||||||||||||

| Gross national product in billions | $3,662.8 | $3,304.8 | $3,069.2 | $2,631.7 | $1,549.2 | $992.7 | 799.6 | 691.0 | 506.5 | 286.5 | 100.0 | 103.4 |

| July 1 population in millions | 245.2 | 243.1 | 240.7 | 235.9 | 224.5 | 214.0 | 207.6 | 203.0 | 183.8 | 154.7 | 134.6 | 123.7 |

| Annualized percent change from the previous period shown: | ||||||||||||

| National health expenditures | 9.1 | 10.6 | 13.9 | 13.3 | 12.1 | 13.4 | ||||||

| Private expenditures | 9.7 | 11.2 | 14.4 | 13.2 | 10.1 | 13.3 | 10.8 | 9.3 | 7.8 | 12.2 | .8 | (2) |

| Public expenditures | 8.2 | 9.6 | 13.2 | 13.3 | 15.2 | 13.6 | 2.5 | 8.8 | 8.2 | 11.2 | .1 | (2) |

| Federal expenditures | 9.0 | 10.2 | 14.6 | 13.9 | 16.0 | 14.0 | 31.3 | 10.6 | 6.8 | 15.5 | 4.6 | (2) |

| State and local expenditures | 6.5 | 8.4 | 10.4 | 12.2 | 13.8 | 12.8 | 46.7 | 12.9 | 6.5 | (2) | (2) | (2) |

| Gross national product | 10.8 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 11.2 | 9.3 | 7.5 | 13.6 | 8.5 | 7.2 | (2) | (2) | (2) |

| Population | .9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 7.6 | 6.4 | 5.9 | 11.1 | −.3 | (2) |

| 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.4 | .8 | (2) | |||||||

Based on July 1 social security area population estimates.

Data are not available.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary.

Figure 1. Growth in national health expenditures and in the gross national product, and national health expenditures as a percent of the gross national product: Calendar years 1965-84.

Almost one-half of the dollars spent for health went for institutional (hospital and nursing home) care and another fifth purchased services of health professionals (Figure 2).

Forty percent of the expenditures for health in 1984 was made by all levels of government, and 30 percent was channeled through private health insurance.

Health expenditures per person grew $119 in 1984 to a level of $1,580—8.1 percent more than in 1983.

Spending for personal health care rose to $342 billion (up 8.5 percent from 1983), averaging $1,394 for every man, woman, and child in the United States.

Growth in hospital spending, at 6.1 percent, was the slowest in 19 years. Hospital expenditures totaling $158 billion accounted for 46 percent of all personal health care spending in 1984.

Physician expenditures grew 10.2 percent in 1984 to $75 billion.

The proportion of personal health care financed by private health insurance dropped slightly in 1984 to 31 percent. Direct patient payments offset that decline.

Medicare spent $63 billion for health care in 1984 (18 percent of total personal health care expenditures); Medicare continued to finance an increasing share of all personal health care.

Medicaid (Federal and State shares combined) financed $37 billion in personal care. With program outlays growing 8 percent in 1984, States appeared to be controlling the more than 15-percent growth that plagued the program in 1979-81.

Despite the increasing share of personal health care expenditures accounted for by Medicare, the proportion funded by all public programs remained virtually unchanged over the past 5 years at 40 percent.

Figure 2. The Nation's health dollar, 1984.

Overview

Expenditures for health in 1984 reached $387 billion, increasing 9.1 percent between 1983 and 1984. This rate of growth was much slower than the 12.7 percent averaged between 1970 and 1983. Health spending amounted to 10.6 percent of the gross national product (GNP). Slower growth in health spending, coupled with the rapid recovery of the general economy from the 1981-82 recession, resulted in a drop in the health expenditure share of the GNP for only the third time in 20 years.

Although part of the slowdown in growth of health spending is attributable to a reduction in the general rate of inflation, other, more fundamental changes have occurred in the delivery of services and in the financing of care. All indications suggest that the future of the health industry will be markedly different from the past.

Changes in the delivery of health care

Mounting pressures on the traditional health system forced changes to occur in the delivery of health care goods and services. The rapid growth of health care prices and the attendant drain on financial resources caused increasing cost consciousness on the part of consumers, employers, and government. Changes in the family structure and mobility of the population affected the traditional delivery system as well. The gradual disappearance of the extended family, a major source of nursing-type health care for the elderly, forced more of that care to come from the “official” health system. Also, the increased mobility of the population eroded the traditional concept of a personal physician because persons may not reside in one location long enough to develop a relationship with a physician. Finally, increased competition for patients manifested itself in changes in the traditional modes of care. The response within the health industry to these pressures has been the development of new providers and services and dramatic growth of some existing ones.

Health maintenance organizations

Health maintenance organizations (HMO's) deliver comprehensive, coordinated medical services to voluntarily enrolled members on a prepaid basis. There are three basic types of HMO's. “A group/staff HMO delivers services at one or more locations through a group of physicians that contracts with the HMO to provide care or through its own physicians who are employees of the HMO. An individual practice association (IPA) makes contractual arrangements with doctors in the community, who treat HMO members out of their own offices. A network HMO contracts with two or more group practices to provide health services” (Office of Health Maintenance Organizations, 1985).

HMO's appeal to health care funding authorities because an HMO contract provides enrollees with a specified package of benefits for a fixed, prepaid, per capita premium. The HMO accepts the financial risk for providing its services, and the funding authority has a predictable cost. Hospital use in HMO's and, consequently, health care costs generally are lower than in the fee-for-service sector. However, this may be in part the result of biased selection of healthy enrollees (Beebe, Lubitz, and Eggers, 1985), as people with chronic conditions have established relationships with individual physicians and may be less likely to join an HMO (DesHarnais, 1985).

HMO's are growing rapidly. As of December 1984, 17 million people were enrolled, up 22 percent from 1983 and double the enrollment of 6 years ago.

“The greatest gains in enrollment were made by plans less than 5 years old, by IPA and network model HMO's, and by plans with more than 50,000 members. The growth of IPA's and networks is particularly significant, according to InterStudy president Paul M. Ellwood, M.D.: ‘The rapid proliferation of nongroup models indicates that the explosive growth of alternative delivery systems has outpaced the service capacity of existing medical groups. The new physicians that are being drawn into HMO's are coming from solo and small group fee-for-service practices. The number of physicians in health plans exceeded 80,000 this year, which is a sufficient number to serve about 30 percent of the U.S. population,’” (InterStudy, 1985).

In the National Health Accounts, HMO hospital care is included with hospital expenditures. Other HMO expenditures are included with physicians' services or with other professional services, depending on the organization of the HMO.

Ambulatory care

Freestanding ambulatory care centers (also known as emergi-or urgi-centers) provide episodic care on a walk-in basis. Typically, these centers feature extended hours and prefer to operate on a pay-as-you-go basis.

Ambulatory care centers offer advantages to certain groups of patients and physicians. These facilities provide services to those people who do not have an established family physician. Most “… are centered in western and sun belt States, where the population is growing, people are mobile, and fewer have private physicians…” (Horwitz, 1985). For physicians who lack the time and/or financial resources to establish a private practice, these facilities offer a setting in which they can deliver services.

Hospitals, on the other hand, view these facilities as “skimming” the least sick of the walk-in patient load, leaving the acute and critical cases for hospital emergency rooms. Hospitals then must spread the fixed costs of maintaining a fully equipped hospital emergency room over fewer cases, raising the average cost of treating those cases.

This type of provider has demonstrated rapid growth in recent years. The number of ambulatory care centers increased from 80 in 1978 to 2,300 in 1984, generating revenue of about $1 billion a year (Jaggar, 1985).

In the National Health Accounts, freestanding ambulatory care centers not owned by health providers are included in other professional services. Those owned by health providers are included with those providers.

Preferred provider organizations

Another type of provider that developed in response to pressures faced by funders of health care was the preferred provider organization (PPO). Generally, a PPO agrees to provide services to a specific population on a discounted fee-for-service basis; some PPO's offer utilization review services as well.

The PPO offers advantages to the employer and insurer, to the consumer, and to the provider. The employer pays less for fee-for-service benefits than would otherwise be the case. The employee has a greater choice of providers than in the case of an HMO, but has a financial incentive (such as reduced coinsurance or deductibles) to use the PPO. The provider is assured access to a pool of patients.

Although PPO's have been widely discussed in the literature, they have yet to become a significant portion of the national health care picture. The number of such groups increased from 33 in 1982 to 115 in 1984; about one-half of them are located in California (Gable and Erman, 1985). Roughly 1.3 million people (or one-half of 1 percent of the U.S. population) are covered by PPO agreements.

In the National Health Accounts, PPO's are treated as though they were individual providers.

Home health care

In the National Health Accounts, home health care covers preventive, supportive, therapeutic, or rehabilitative medical care provided in a home setting. A broader industry definition includes supportive social services such as homemaker, choreworker, home delivered meals, friendly visits, and telephone reassurance. Regardless of definition, the area has been one of rapid growth.

Home health care has a number of advantages for the patient. As a substitute for institutional care, home health services allow patients to remain in their own homes which adds to the psychological wellbeing of the patient, and can involve less cost.

Home health agencies (HHA's) also play an important role in hospitals' efforts to maintain revenue. The home health department's most important function is to serve as “feeders” for the hospital, identifying potential patients and directing them to the hospital. Under pressure through the prospective payment system (PPS) to reduce inpatient costs, hospital-based home health care also allows the hospital to discharge patients and continue to generate revenue from the patient's care. Such departments offer a wider base over which to spread overhead costs and serve as a marketing tool as well. Further, home health care reduces the hospital's exposure to malpractice suits (Cassak, 1984; Ginzberg, Balinsky, and Ostow, 1984).

Hospitals are moving into home health care in increasing numbers. In 1984, 42 percent of the Nation's hospitals offered home health services; that fraction is expected to reach 65 percent in 1985 (Glenn, 1985a).

Home health care is a small but rapidly growing segment of the health care delivery system, increasing at an estimated average annual rate of 20 percent to 25 percent in recent years. Current estimates of total industry spending project growth from $9 billion in 1985 to $16 billion in 1990 for home health products and services; 70 percent of the total is for services (Frost and Sullivan, 1983).

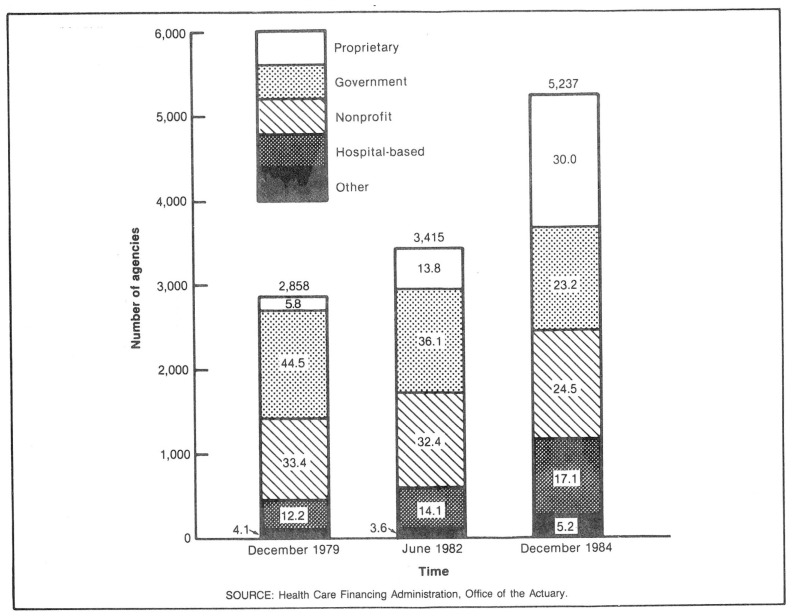

The home health care industry has changed dramatically. From delivery of nursing care by family and friends or Visiting Nurse Associations (VNA's), the industry has evolved into a complex health delivery system that involves Government; VNA's; private nonprofit, proprietary, and facility-based providers; and a variety of services (Figure 3). The most significant change in the home health industry has been the emergence of proprietary agencies, particularly chains, as the largest single form of organization. Studies indicate that HHA chains, perceiving home health to be a lucrative market, have been growing rapidly. Corporations controlling the large HHA chains appear to be closely related to other primary health industries such as pharmaceuticals, nursing care facilities, and freelance medical staffing agencies (Williams, Gaumer, and Cella, 1984).

Figure 3. Number and percent distribution of Medicare-certified home health agencies, by type of agency, selected points in time.

A major reason for the rapid growth of proprietary HHA's was a legislative change in 1980 that eased Medicare certification requirements for proprietary HHA's in States without licensure laws. The number of certified proprietary HHA's, currently 1,570 or 30 percent of all agencies, increased threefold between 1982 and 1984.

Because it has been estimated that people 65 years of age or over receive 85-90 percent of home health care furnished (Ginzberg, Balinsky, and Ostow, 1984; Frost and Sullivan, 1983; Cassak, 1984), the aging of the population is an important factor for industry growth. The population 65 years of age or over is projected to increase from 28.4 million people (or 11.6 percent of the population) in 1984, to 32.4 million (or 12.6 percent of the population) in 1990 (Social Security Administration, 1985). The average annual rate of growth of the aged population is expected to be 2½ times faster than the rate of growth of the overall population between 1984 and 1990.

Changes in the financing of health care

The second major force affecting the health care industry has been changes in the nature of financing health care. Those changes resulted from pressure building up on traditional sources of funds. The Government found itself faced with increased demands for health care dollars at the same time that growth of the flow of revenues to fund those programs slowed. The Federal Medicare program, in particular, was projected to become insolvent as early as 1987 in the absence of changes to entitlement, reimbursement, or coverage.

Business, too, felt the pressure of rising health expenditures. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce's Employee Benefits Survey noted increases in health insurance costs as a percentage of payroll costs: from 4.5 percent in 1980 to 6.1 percent in 1983. These costs can put a company at a competitive disadvantage both domestically and internationally. Regionally, “… for example, McDonnell Douglas Corporation pays double the hospital room rate in St. Louis that Boeing Company pays in Seattle….” (Business Week, 1984). Further, in a period when U.S. firms face stiff competition from foreign manufacturers, anything that adds to costs of American goods threatens market position.

The response to these pressures has been to modify the method by which funders of health care pay for that care. In the case of Medicare PPS, implemented during 1983 and 1984, replaced a system of cost-based reimbursement with set prices for the treatment of each of 467 different diagnosis-related groups (DRG's).

Employers also have reacted to financial pressures. Coalitions have been formed to study the response to rising health care costs and to put pressure on providers and insurers to assure efficient use of health care goods and services. Many businesses are addressing the cost-control issue head on by self-funding their health benefits. Some are placing pressure on their insurance carriers to redefine benefits packages to increase employee cost sharing and to increase the incentives for use of such things as second opinions and outpatient, rather than inpatient, surgery. Others have negotiated with PPO's and HMO's or they have built and staffed their own facilities.

Consumers also have become more involved in the use and financing of health care. Part of this is because of increased coinsurance and deductibles in insurance packages; part is because of the general rise in consumer activism; and part is because patients are better educated regarding the implications of and alternatives to various medical procedures.

Effects of changes in health care delivery and financing

The effects of changes in the traditional health care delivery system and changes in the methods of financing have rippled throughout the industry.

The institution of the Medicare prospective payment system (PPS) may have had an information effect on physician practice patterns. Researchers have contended that variations in physician practice patterns cause wide variations in lengths of stay. Variations translate into significant differences in the cost of treating similar illnesses. Local area studies show that physicians will alter practices once information becomes available showing that shorter hospitalizations are used by their colleagues without adverse effects on their patients' health (Wennberg, 1984).

PPS may have provided the necessary information to allow admitting physicians to identify practice patterns (specifically hospital length of stay) that exceed national norms. In light of this comparison, practice patterns were altered, resulting in shorter hospitalizations. Although PPS applies primarily to the aged, drops in lengths of stay are apparent for the population under 65 years of age as well. From 1975 to 1983, lengths of hospital stays for those 65 years of age or older declined at an average annual rate of 1.8 percent; in 1984, the lengths of hospital stays declined 7.5 percent. For the population under 65 years of age, lengths of stays dropped at an average annual rate of .8 percent between 1975 and 1983; in 1984, it dropped 3.5 percent (Hospital Data Center, 1985).

Reimbursement change resulting in the reduction of hospital utilization and in the increased competition for patients has forced hospitals to specialize in delivery of certain services and to diversify their role in the provision of care. Hospitals are creating freestanding outpatient clinics and developing home health care service departments. Some find it advantageous to purchase other links in the health service production chain, such as hospital supply companies or nursing homes. Other strategies include the specialization of services by an individual hospital in a market area so that the purchase of efficient and effective technology can be cost justified.

Increasingly, hospitals are turning to professional managers to direct their operations as businesses. Extensive cost savings are being realized through such basic operations as centralized, coordinated purchasing, either within a single hospital or among a group of facilities. Marketing and advertising are becoming important aspects of a hospitals's business (Glenn, 1985b). Each hospital is attempting to differentiate its product from its competitors in an effort to attract patients. For instance, one hospital in Washington, D.C., discovered a market for high-cost, luxury hospital suites, complete with penthouse balconies and gourmet meals available 24 hours a day (Washington Hospital Center, no date).

Changes in the delivery of care and the sources of financing have effected shifts in power within the health industry. Third parties have assumed a more active role in determining which services will be consumed and how many. Private health insurers are instituting mandatory second and third opinions and paying fully for these evaluations. Medicare's PPS encouraged shorter lengths of stay per admission. Scrutiny of hospital admissions by Medicare peer review organizations (PRO's) will probably contribute to slower growth of admissions in the future.

In addition to the more active role of third parties, the power structure within the hospital setting is changing. Hospitals have been exerting influence on admitting physicians to curb excess use of services. Physicians will no longer be an asset to a hospital if patients cannot be handled economically. In addition, physician influence in hospital decisionmaking is being tempered by the authority of nonmedical hospital managers.

Health industry indicators

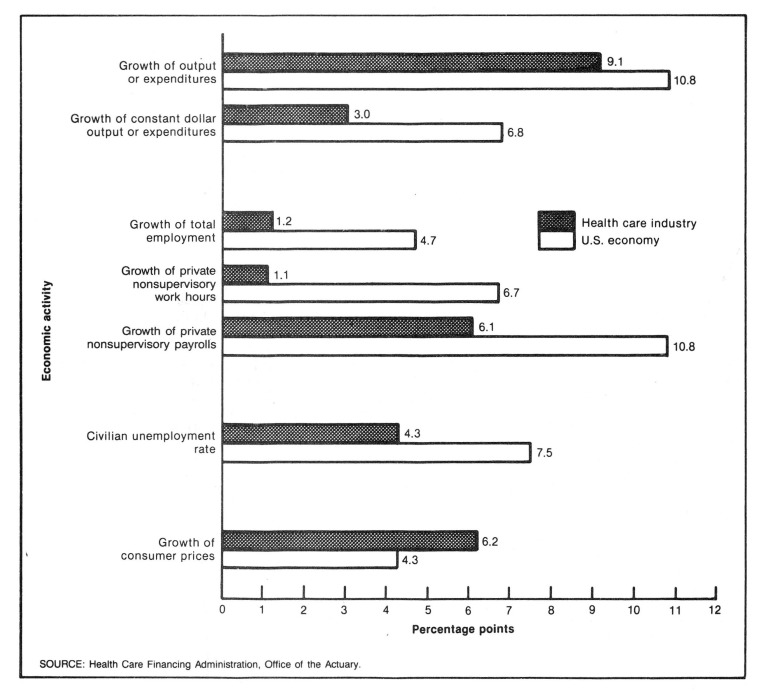

The changes mentioned above and the effects they created are reflected in data on the health care sector (Figure 4). Growth of input and output measures slowed, and the gap in price inflation narrowed. However, the basic strength of the industry remains.

Figure 4. Measures of economic activity in the health care industry and in the United States as a whole: 1984.

Growth of input measures has slowed. Total employment decelerated in 1983 and again in 1984, rising 1.2 percent from the 1983 levels. Work hours and average weekly earnings also decelerated, growing 1.1 percent and 6.1 percent, respectively one-half the historic rates.

Output growth slowed as well. After adjustment for price inflation, personal health care expenditures grew 2.1 percent in 1984, well below the 4.9 percent average between 1965 and 1983.

Price inflation for medical care is still greater than that for other consumer prices. The Consumer Price Index for medical care increased 6.2 percent in 1984, compared with 4.3 percent for all consumer goods and services. This difference is not unexpected. Economic theory suggests that service industries are more prone to output price inflation than manufacturing industries are (Baumol, 1967). However, as evidence of the pressure on the health industry, the relative gap between the two inflation rates was reduced from a factor of 2 in 1982 and 1983 to about 1½ in 1984.

Despite its slower growth, the industry is still strong. With over 7.4 million employees in 1984, it was among the largest in the Nation in terms of employment or earnings. The unemployment rate for health workers was almost one-half the rate for workers in all industries.

Goods and services purchased in 1984

“National health expenditures” are defined to include all spending for health care of individuals, the administrative costs of nonprofit and Government health programs, the net cost to enrollees of private health insurance, Government expenditures through public health programs, noncommercial health research, and construction of medical facilities. The definition excludes spending for environmental improvement and for subsidies and grants for health professionals' education, categories that often are included with health in Federal budget documents.

National health expenditures are divided into two categories: health services and supplies (expenditures related to current health) and research and construction of medical facilities (expenditures related to future health) (Table 2). Health services and supplies, in turn, consist of personal health care (the direct provision of care), program administration and the net cost of insurance, and Government public health activities.

Table 2. National health expenditures, by type of expenditure: Selected calendar years 1929-84.

| Type of expenditure | 1984 | 1983 | 1982 | 1980 | 1975 | 1970 | 1967 | 1965 | 1960 | 1950 | 1940 | 1929 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||||

| National health expenditures | $387.4 | $355.1 | $321.2 | $247.5 | $132.7 | $75.0 | $51.5 | $41.9 | $26.9 | $12.7 | $4.0 | $3.6 |

| Health services and supplies | 371.6 | 339.8 | 307.0 | 235.6 | 124.3 | 69.6 | 47.6 | 38.4 | 25.2 | 11.7 | 3.9 | 3.4 |

| Personal health care | 341.8 | 315.2 | 284.9 | 219.1 | 117.1 | 65.4 | 44.5 | 35.9 | 23.7 | 10.9 | 3.5 | 3.2 |

| Hospital care | 157.9 | 148.8 | 134.7 | 101.3 | 52.4 | 28.0 | 18.4 | 14.0 | 9.1 | 3.9 | 1.0 | .7 |

| Physicians' services | 75.4 | 68.4 | 61.8 | 46.8 | 24.9 | 14.3 | 10.1 | 8.5 | 5.7 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Dentists' services | 25.1 | 21.8 | 19.5 | 15.4 | 8.2 | 4.7 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 2.0 | 1.0 | .4 | .5 |

| Other professional services | 8.8 | 8.0 | 7.1 | 5.6 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.0 | .9 | .4 | .2 | .3 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 25.8 | 23.6 | 21.8 | 18.5 | 11.9 | 8.0 | 5.8 | 5.2 | 3.7 | 1.7 | .6 | .6 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 7.4 | 6.5 | 5.6 | 5.1 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.2 | .8 | .5 | .2 | .1 |

| Nursing home care | 32.0 | 29.4 | 26.9 | 20.4 | 10.1 | 4.7 | 2.8 | 2.1 | .5 | .2 | (1) | (1) |

| Other personal health care | 9.4 | 8.6 | 7.6 | 5.9 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.1 | .5 | .1 | .1 |

| Program administration and net cost of health insurance | 19.1 | 14.5 | 12.8 | 9.2 | 4.0 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1.1 | .5 | .2 | .1 |

| Government public health activities | 10.7 | 10.1 | 9.3 | 7.2 | 3.2 | 1.4 | .9 | .8 | .4 | .4 | .2 | .1 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 15.8 | 15.3 | 14.2 | 11.9 | 8.4 | 5.4 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 1.7 | 1.0 | .1 | .2 |

| Noncommercial research2 | 6.8 | 6.2 | 5.9 | 5.4 | 3.3 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.5 | .7 | .1 | (1) | (1) |

| Construction | 9.0 | 9.1 | 8.3 | 6.5 | 5.1 | 3.4 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | .8 | .1 | .2 |

Less than $50 million.

Research and development expenditures of drug companies and other manufacturers and providers of medical equipment and supplies are excluded from “research expenditures,” but they are included in the expenditure class in which the product falls.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary.

Personal health care

A total of $342 billion was spent for personal health care in 1984, up 8.5 percent from the amount spent in 1983. In 1984, $1,394 was spent per capita for personal health care—an increase of 7.5 percent from the 1983 level.

Growth in personal health care is at the lowest level recorded since 1965—the first period covered in the current National Health Accounts. Reduced growth can be attributed to lower price inflation in the general economy and in the medical sector and to changes in third-party reimbursement policy which have altered utilization patterns.

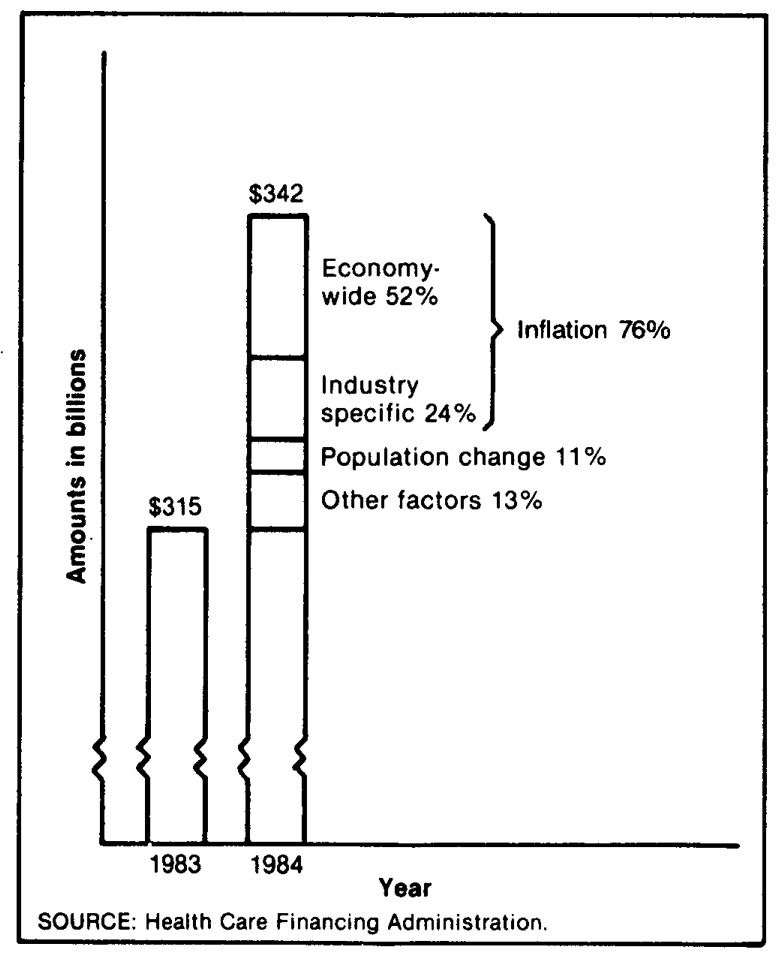

Although price inflation has been moderating, it still accounts for most of the growth in spending for personal health care. In Figure 5, 76 percent of the increase in spending between 1983 and 1984 was the result of price inflation; another 11 percent was the result of population growth. The remainder was the result of the interaction of a variety of influences, among them the aging of the population, changes in consumption per capita, and changes in the types of services provided.

Figure 5. Factors in the increase of personal health care expenditures: 1983-84.

Third parties account for almost three-quarters of the spending for personal health care (Table 3). Private health insurance benefits amounted to $107 billion in 1984, and other private third-party benefits (philanthropy and industrial inplant health programs) amounted to $4 billion. The Federal Government spent $101 billion, most of it through Medicare and Medicaid, and State and local governments spent $34 billion, about one-half of which was channeled through Medicaid.

Table 3. National health expenditures, by type of expenditure and source of funds: Calendar years 1982-84.

| Type of expenditure | All sources of funds | Private | All public funds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| All private funds | Consumer | Other1 | Total | Federal | State and local | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Total | Direct | Insurance | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Amount in billions | |||||||||

| 1984 National health expenditures | $387.4 | $227.1 | $215.9 | $95.4 | $120.5 | $11.2 | $160.3 | $111.9 | $48.3 |

| Health services and supplies | 371.6 | 220.3 | 215.9 | 95.4 | 120.5 | 4.4 | 151.2 | 105.4 | 45.9 |

| Personal health care | 341.8 | 206.5 | 202.5 | 95.4 | 107.2 | 3.9 | 135.4 | 101.1 | 34.3 |

| Hospital care | 157.9 | 73.5 | 71.9 | 13.7 | 58.2 | 1.6 | 84.3 | 65.6 | 18.7 |

| Physicians' services | 75.4 | 54.5 | 54.4 | 21.0 | 33.5 | (3) | 20.9 | 16.9 | 4.0 |

| Dentists' services | 25.1 | 24.5 | 24.5 | 16.3 | 8.3 | — | .5 | .3 | .3 |

| Other professional services | 8.8 | 6.0 | 5.9 | 3.5 | 2.4 | .1 | 2.8 | 2.2 | .6 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 25.8 | 23.5 | 23.5 | 19.7 | 3.8 | — | 2.4 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 7.4 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 5.5 | .8 | — | 1.2 | 1.1 | .1 |

| Nursing home care | 32.0 | 16.3 | 16.1 | 15.8 | .3 | .2 | 15.7 | 8.8 | 6.9 |

| Other personal health care | 9.4 | 2.0 | — | — | — | 2.0 | 7.5 | 5.1 | 2.4 |

| Program administration and net cost of health insurance | 19.1 | 13.9 | 13.4 | — | 13.4 | .5 | 5.2 | 2.9 | 2.3 |

| Government public health activities | 10.7 | — | — | — | — | — | 10.7 | 1.4 | 9.3 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 15.8 | 6.7 | — | — | — | 6.7 | 9.0 | 6.6 | 2.5 |

| Noncommercial research2 | 6.8 | .4 | — | — | — | .4 | 6.4 | 5.8 | .6 |

| Construction | 9.0 | 6.4 | — | — | — | 6.4 | 2.6 | .7 | 1.9 |

| 1983 National health expenditures | 355.1 | 207.0 | 196.0 | 86.4 | 109.7 | 11.0 | 148.1 | 102.7 | 45.4 |

| Health services and supplies | 339.8 | 200.2 | 196.0 | 86.4 | 109.7 | 4.2 | 139.6 | 96.8 | 42.8 |

| Personal health care | 315.2 | 190.4 | 186.7 | 86.4 | 100.3 | 3.7 | 124.8 | 92.9 | 31.9 |

| Hospital care | 148.8 | 71.0 | 69.4 | 12.8 | 56.6 | 1.6 | 77.8 | 60.6 | 17.2 |

| Physicians' service | 68.4 | 49.1 | 49.1 | 18.9 | 30.1 | (3) | 19.3 | 15.6 | 3.8 |

| Dentists'services | 21.8 | 21.2 | 21.2 | 13.9 | 7.3 | — | .6 | .3 | .3 |

| Other professional services | 8.0 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 3.6 | 2.0 | .1 | 2.4 | 1.8 | .5 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 23.6 | 21.5 | 21.5 | 18.2 | 3.3 | — | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 6.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 4.8 | .7 | — | 1.0 | .9 | .1 |

| Nursing home care | 29.4 | 14.6 | 14.4 | 14.2 | .2 | .2 | 14.8 | 8.1 | 6.7 |

| Other personal health care | 8.6 | 1.8 | — | — | — | 1.8 | 6.7 | 4.5 | 2.2 |

| Program administration and net cost of health insurance | 14.5 | 9.8 | 9.4 | — | 9.4 | .5 | 4.7 | 2.7 | 2.0 |

| Government public health activities | 10.1 | — | — | — | — | — | 10.1 | 1.3 | 8.8 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 15.3 | 6.8 | — | — | — | 6.8 | 8.5 | 5.9 | 2.6 |

| Noncommercial research2 | 6.2 | .4 | — | — | — | .4 | 5.8 | 5.2 | .6 |

| Construction | 9.1 | 6.5 | — | — | — | 6.5 | 2.7 | .7 | 2.0 |

| 1982 National health expenditures | $321.2 | $186.1 | $176.2 | $77.2 | $99.0 | $9.9 | $135.1 | $93.2 | $41.9 |

| Health services and supplies | 307.0 | 180.0 | 176.2 | 77.2 | 99.0 | 3.8 | 127.0 | 87.6 | 39.4 |

| Personal health care | 284.9 | 171.5 | 168.2 | 77.2 | 91.0 | 3.4 | 113.4 | 83.9 | 29.5 |

| Hospital care | 134.7 | 63.5 | 62.1 | 10.3 | 51.8 | 1.4 | 71.2 | 55.4 | 15.8 |

| Physicians' services | 61.8 | 44.8 | 44.8 | 17.7 | 27.1 | (3) | 16.9 | 13.4 | 3.6 |

| Dentists' services | 19.5 | 18.9 | 18.9 | 12.4 | 6.5 | — | .6 | .3 | .3 |

| Other professional services | 7.1 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 3.3 | 1.8 | .1 | 2.0 | 1.5 | .5 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 21.8 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 16.9 | 2.9 | — | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 5.6 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.2 | .6 | — | .8 | .7 | .1 |

| Nursing home care | 26.9 | 12.9 | 12.7 | 12.4 | .3 | .2 | 14.0 | 7.7 | 6.4 |

| Other personal health care | 7.6 | 1.7 | — | — | — | 1.7 | 5.9 | 4.0 | 1.9 |

| Program administration and net cost of health insurance | 12.8 | 8.4 | 8.0 | — | 8.0 | .4 | 4.3 | 2.4 | 1.9 |

| Government public health activities | 9.3 | — | — | — | — | — | 9.3 | 1.2 | 8.1 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 14.2 | 6.1 | — | — | — | 6.1 | 8.1 | 5.6 | 2.5 |

| Noncommercial research2 | 5.9 | .3 | — | — | — | .3 | 5.5 | 5.0 | .6 |

| Construction | 8.3 | 5.8 | — | — | — | 5.8 | 2.5 | .6 | 1.9 |

Spending by philanthropic organizations, industrial inplant health services, and privately financed construction.

Research and development expenditures of drug companies and other manufacturers and providers of medical equipment and supplies are excluded from “research expenditures,” but they are included in the expenditure class in which the product falls.

Less than $50 million.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary.

Personal health care consists of a number of different goods and services.

Physicians' services

Expenditures for physicians' services reached $75 billion in 1984—an increase of 10.2 percent from the previous year. This spending accounted for 22 percent of personal health care expenditures.

Third parties play a large role in the financing of physicians' services. The Federal Government financed 22 percent, and private health insurance benefits financed 44 percent of the total. State and local governments paid for 5 percent of the total; and the balance, some 28 percent, was paid by patients or their families.

Price inflation was a significant contributor to the growth of expenditures for physicians' services. Measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), physicians' fees rose 7.0 percent in 1984, compared with an increase of 4.3 percent in the CPI for all items.

Physicians are major players in determining the size and shape of the health care sector. In determining who will be hospitalized, what type and quantity of services the hospital patient will receive, and what drugs will be prescribed, physicians' influence extends far beyond the 22 percent share of spending devoted to their services.

Traditional relationships within the medical sector are in transition, and the physician sector is at the forefront of this change.

The supply of physicians is increasing faster than the population, leading to increased competition for patients and for hospital practice privileges. More and more young physicians are opting for employment in alternative care sites such as health maintenance organizations and ambulatory care centers, rather than opening a solo practice. Established physicians are creating physician groups to share overhead costs. Sharing costs permit practices to purchase the latest technology, which can keep a practice attractive to patients. Another strategy used by physicians to increase their patient load is to become part of preferred provider organizations or primary care networks. By negotiating fee reductions with employers and insurers, physicians access a captive supply of patients who could choose to use their services.

The changing relationship between physicians and hospitals is precipitated by changing third-party reimbursement policy. Hospitals must be operated as businesses since their financial viability is at stake. Increasingly, professional managers are replacing physicians as administrators and decisionmakers in hospitals. Physicians are beginning to see hospitals as competitors for patients. Hospitals are promoting their services by expanding their organized outpatient departments and opening clinics and ambulatory care centers. They are restructuring their emergency room fee schedules to make charges for nonemergency care more competitive with physician office visit fees.

The changing age composition of the population will necessitate changes in physician specialization. Low birth rates limit the need for growth of pediatric and obstetric specialists. Conversely, the growing proportion of elderly persons will increase demand for geriatric and other specialists whose practices serve large numbers of individuals over the age of 65 years.

Competition from nonphysician personnel—physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and other health professionals—is growing. As costs increasingly become a factor in the provision of care, demand for these allied health professionals will grow (American Medical Association, 1985).

In the National Health Accounts, expenditures for physicians' services encompass the cost of all services and supplies provided in physicians' offices, the cost for services of private practitioners in hospitals and other institutions, and the cost of diagnostic work performed in independent clinical laboratories. The salaries of staff physicians are counted with expenditures for the services of the employing institution.

Hospital care

Expenditures for hospital care services in 1984 reached $158 billion, representing 46 percent of all personal health care spending. Expenditures grew 6.1 percent over the 1983 level, the slowest increase experienced in the last 19 years.

Declines in utilization of hospital services impact on the growth in hospital expenditures. Factors other than reduced admissions contributing to increased community hospital expenditures can be determined by examining the growth in revenues per admission as reported in the American Hospital Association's Panel Survey. Economy-wide inflation, as measured by the gross national product fixed-weight price index, accounted for 44 percent of the increase; 16 percent of the growth can be attributed to inflation in hospital input prices in excess of enonomy-wide inflation as measured by the Health Care Financing Administration's National Hospital Input Price Index (Freeland, Anderson, and Schendler, 1979). The remaining 40 percent of the increase in hospital spending results from the interaction of a variety of factors, including changes in length of stay, changes in the mix of services provided per hospitalization (outputs), and changes in the mix of goods and services used to provide those hospital services (inputs).

The proportion of hospital expenditures financed by public programs continued to increase in 1984, reaching 53 percent. The Federal Medicare program alone paid for 28 percent of all hospital services, up from 27 percent in 1983. Medicaid financed another 9 percent.

Consumers paid for 37 percent of hospital care through their coverage with private health insurance. They financed another 9 percent by directly paying for services.

In the National Health Accounts, hospital care includes all inpatient and outpatient care in public and private hospitals and all services and supplies provided by hospitals. Except for services of hospital staff physicians, expenditures for physician care provided in hospitals are included in the physician category described previously.

Dramatic changes in the hospital industry that began to take place in 1983 are being confirmed in 1984. Growth in input prices as measured by the Health Care Financing Administration's Input Price Index (Freeland, Anderson, and Schendler, 1979) dropped to 5.9 percent in 1984, well below the double-digit growth experienced between 1979 and 1982. Data on use of community hospital services in 1984 provide further evidence of those changes (Hospital Data Center, 1985): Admissions declined 1.4 million (down 3.7 percent); inpatient days were off 22.7 million (down 8.6 percent). Length of stay declined to 6.7 days—the lowest level ever recorded. To some extent, decreased inpatient utilization was offset by overall outpatient hospital visits, increases that were in line with historical trends. Community hospitals responded to decreased inpatient utilization in 1984 by reducing the number of beds (a 1.1 percent decline) and reducing staff (a 2.3 percent decline in full-time equivalent personnel).

Community hospitals made record profits in 1984. Despite the slowest growth of revenue ever recorded by the American Hospital Association (6 percent), profits were up 27.6 percent from 1983, reaching $8.3 billion. Some of the increase in the operating margin may be attributable to diagnosis-related group (DRG) prices that may have been set too high (General Accounting Office, 1985b). Part of this growth is attributed to a rapid response to the prospective payment system, as hospitals moved to eliminate ineffective practices. In that sense, high profit rates may be a short-run phenomenon. However, the trend over the past 10 years has been that operating margins have increased each year.

Reimbursement changes have forced hospitals to diversify their role in the provision of care. Reduced occupancy levels make hospitals more conscious of the places where patients enter the health care system. These points of entry are becoming essential links in attracting patients and directing them to specific hospital facilities. Strategies employed by hospitals to increase patient flow include offering office space to admitting physicians at attractive rates; restructuring emergency room fees for nonemergency cases to make services more competitive with those performed in a physician's office; opening ambulatory clinics in shopping centers and metropolitan locations; and conducting marketing surveys to determine services which could be offered to attract patients (Parker, 1985).

Beyond seeking sources for additional patients, hospitals are being restructured to deal with earlier discharging of patients. Currently, hospitals are reimbursed for services to Medicare patients under the DRG system. In order to keep expenses down, hospitals must discharge Medicare patients as quickly as possible. Hospitals are establishing relationships with, or directly purchasing, nursing homes to insure their ability to discharge patients as soon as it is medically indicated. Protracted hospital stays by Medicare patients cut into the hospital's operating margin.

Frequently, discharged patients need less intense care than that which a nursing home provides, but they still require assistance beyond that which is available at home. To meet this need, hospitals are expanding into the home health service business.

Nursing home care

In 1984, $32 billion was spent for nursing home care—an increase of 8.9 percent from the previous year. Such care amounted to 8 percent of total health spending and to 9 percent of personal health care expenditures.

In the National Health Accounts, nursing home services are those provided in skilled nursing facilities, in intermediate care facilities, and in personal care homes that provide nursing care. In addition, a majority of the care for mentally retarded Medicaid recipients provided in intermediate care facilities for the mentally retarded (ICFMR) is included as nursing home care. Nursing-type care provided in hospitals (including ICFMR care) is included with expenditures for hospital care.

Part of the growth in spending for nursing home care over the last decade has been the result of rapid expansion in intermediate care facilities for the mentally retarded, a Medicaid benefit first offered in 1973. Currently, about $2.6 billion (60 percent of the total expenditures for ICFMR) is spent in nursing homes. Despite its relatively small size, growth in spending for ICFMR raised the growth rate of total nursing home spending in every year through 1981. This rate of growth decelerated in 1982 and slowed to 8.1 percent in 1984, slightly lowering the growth rate in aggregate spending for nursing home care.

Growth in spending for nursing home care other than ICFMR also slowed considerably in recent years. Part of this slowdown is the result of a deceleration of prices paid by nursing homes: Health Care Financing Administration's National Nursing Home Input Price Index rose 4.7 percent in 1984, the smallest increase since this measure was developed. One-half of the increase between 1983 and 1984 in expenditures for nursing home care other than ICFMR was attributable to general inflation measured by the gross national product fixed-weight price index; 5 percent was the result of inflation specific to the nursing home industry. The aged population increased 2 percent in 1984; that increase accounted for one-quarter of the growth in nursing home spending. The residual can be accounted for by changes in the amounts and mix of nursing home goods and services provided.

The share of nursing home care financed by public programs has declined since 1979, from 56 percent to 49 percent. Almost all of that decline was in Medicaid and Medicare shares. Reduced utilization of nursing home care by Medicaid and Medicare patients has been occurring. The explanation for this reduction is twofold. First, the shortage of nursing home beds in some areas allows nursing homes to selectively admit patients (Feder and Scanlon, 1981). Higher paying private patients will be admitted before Medicaid or Medicare patients. Second, the shortage of beds may be induced in some States in order to minimize Medicaid expenditures. Tactics used by States include tightening certificate-of-need requirements and keeping reimbursement rates low (Weissert, et al., 1984). Potential investors in the nursing home business may be discouraged by the low profitability of the industry, because of these reimbursement policies.

However, as a result of public program policies, structural changes within the nursing home industry may be occurring. Hospitals, under pressure from Medicare's predetermined per case payment system, are striving to control costs and utilization. There is anecdotal evidence that reductions achieved in hospital length of stay for Medicare patients increased demand for post-hospital nursing home care and/or the intensity of services these patients require (Chelimsky, 1985). To guarantee availability of post-hospital care, hospitals have responded by entering into reserve bed agreements with nursing homes, i.e., an agreement to pay a nursing home to reserve a specific number of beds whether or not they are used by the hospital's discharged patients; purchasing or building nursing facilities; or by converting excess acute care beds to in-house, long-term care units.

Drugs and medical sundries

Twenty-six billion dollars was spent for drugs and medical sundries in 1984, 9.4 percent more than in 1983. This figure reflects the retail purchase of prescription and nonprescription drugs and medical sundries. (The dollar value of drugs purchased and dispensed in hospitals, nursing homes, practitioners' offices, and so on is included with expenditures for the dispensers' services).

Nine-tenths of the 1984 spending for drugs and sundries came from private funds. Most of that, in turn, came directly from consumers: $20 billion, or three-quarters of total expenditures in the category. Private health insurance benefits amounted to $4 billion; and Federal, State, and local governments each paid a little over $1 billion, mostly through Medicaid. There has been very little change in the public or private distribution of expenditures since 1965. However, there has been a rapid expansion in the private health insurance share and a corresponding decline in the direct-payment share of spending, particularly since 1977.

“Real” growth in the purchases of drugs and sundries has been slower than that for other health care goods and services in the 1965 to 1984 period. Price-adjusted growth for drugs and sundries averaged 5.8 percent annually between 1965 and 1978, compared with an average price-adjusted growth of 5.5 percent for all personal health care. However, all of the growth in spending for drugs and medical sundries since 1978 has been the result of price inflation. Some of the recent slowdown in growth is attributable to changes in physician and patient perceptions of drug use, with particular drops in the prescription of psychotherapeutic drugs (Hilts, 1982).

Other personal health care goods and services

Expenditures for all other types of personal health care goods and services were $51 billion in 1984—an increase of 12.9 percent. That spending amounted to 15 percent of all personal health care expenditures. Almost equal proportions of this group of services were financed through Government programs (24 percent) and private health insurance (23 percent) in 1984; consumers paid for 50 percent directly. Almost one-half of the expenditures in this category were for dentists' services, but the category also includes spending for services of other health professionals (including most home health agencies), for eyeglasses and orthopedic appliances, and for other health services (including the provision of care in industrial settings and school health). Growth of this composite component was influenced significantly by the growth of spending for dentists' services, which grew 15 percent over the 1983 level.

Spending for dental services reached $25 billion in 1984. Price inflation for dental services coupled with strong demand for services by consumers (evidenced by continued steady growth in employment and expansion in the number of hours worked each week in dental offices) has produced increases in dental expenditures of 15.0 percent in 1984. Use of dental services fluctuates with the business cycle, because the consumer directly paid for a large portion of the services. Since 1980, however, private health insurance has been financing one-third of all dental services, somewhat dampening the effects of the business cycle.

Other health services and supplies

The cost of operating third-party programs in 1984 rose 31.2 percent, to $19 billion. This estimate includes $5.2 billion in administrative expenses for those public programs that identified administrative expenses. It also includes a small amount estimated to be the fundraising and administrative expenses of philanthropic organizations. The largest part of the component is the net cost of private health insurance—i.e., the difference between earned premiums and incurred claims. Estimated at $13 billion for 1984, net cost reflects administrative expenses; additions to loss reserves; and profits or losses of Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans, mutual and stock carriers, and prepaid and self-insured health plans.

Public health activities of various levels of Government amounted to $11 billion in 1984. Public health activities are those functions carried out by Federal, State, and local governments to support community health, in contrast to care delivered to individuals. Federal expenditures of $1.4 billion included the services of the Centers for Disease Control and the Food and Drug Administration, as well as grants to States.

Other national health expenditures

National health expenditures devoted to nonprofit research and to construction of medical facilities were $16 billion in 1984, an amount equal to 4 percent of total health spending.

Expenditures for noncommercial health care research and development were $6.8 billion in 1984. The Federal Government financed by far the largest amount for research, with funds totalling $5.8 billion, most of which was spent by the National Institutes of Health. Expenditures by State and local governments, exclusive of Federal grants, were $616 million; private philanthropy funded an even smaller amount.

The $6.8 billion in spending for research in the National Health Accounts excludes research performed by drug companies and by other manufacturers and suppliers of health care goods and services, estimated to be $4.5 billion in 1984. As this type of research is treated as a business expense and is financed through sales of goods or services, its value is included in personal health care expenditures; to include it again in research would result in double counting.

Of the $9.0 billion spent on construction of medical facilities in 1984, 29 percent was funded from public sources. Grants from philanthropic organizations funded 5 percent, and the remainder came from internal funds or from the private capital market. This estimate does not include spending for capital equipment, because there is no source of data to yield a reliable, consistent timeseries of data on spending for equipment.

Financing health care

Third-party financing

Unlike other goods or services for which the consumer pays the provider directly, health care payments often are handled by a financial agent—a “third party.” The details of the payment method may vary: The consumer may pay the provider and apply for reimbursement from the third party, or the provider may bill the third party directly, or the provider may be employed by the third party (as in the case of U.S. Department of Defense hospitals or industrial inplant services, for example). In the case of Medicare, institutional providers bill “fiscal intermediaries,” private health insurers acting as agents for the Federal Government, and physicians may bill either the fiscal intermediary or the patient.

The existing third-party coverage of health care has contributed to a healthier population, but it has exacted a price as well. Insurance has increased access to care, resulting in treatment of patients who otherwise would have been priced out of the medical care market. However, the historical structure of insurance benefits encouraged use of inpatient rather than outpatient facilities, and encouraged overuse of tests and procedures rather than underuse. The financial incentives embedded in traditional reimbursement structures have encouraged increased use of medical care, but not at the lowest cost.

Private health insurance

Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans, commercial insurance companies, and prepaid and self-insured plans incurred claims estimated at $107 billion in 1984, an amount equal to 31 percent of personal health care expenditures. These benefit payments were 6.9 percent higher than in 1983. Insurers earned an estimated $121 billion in premiums, 56 percent of all nonpublic spending for health, resulting in a net cost to enrollees of $13 billion.

The size of the private health insurance industry has been growing, induced by the perceived desire for its services and by the preferential tax treatment of premiums. By 1984, 52 percent of private expenditures for personal health care—the amount not covered by public programs—was reimbursed by private insurance. In 1984, approximately three-quarters of the U.S. population was covered by private health insurance for hospital care, compared with one-half in 1950. The relatively rapid rate of growth of insurance premiums—14 percent per year since 1950, compared with an increase of 11 percent in total personal health care expenditures—reflects the desire for the prepayment and risk-sharing offered by private health insurance and the subsidy that tax treatment of health premiums afford.

Self-insured plans have been growing since the latter half of the seventies. This growth has been stimulated by tax and other financial advantages to employers. Insurance companies have also contributed to this growth by providing administrative and stop-loss services that aid and protect self-insured plans. The prepaid plans category, comprised of health maintenance organizations and single-service plans, has also grown significantly in recent years, but it still remains a small part of overall insurance.

The advent of Medicare and Medicaid slowed the growth of the private health insurance share of personal health care expenditures. Private health insurance's share of spending doubled between 1950 and 1965, reaching 24 percent (Table 4). Since 1967, this share has grown gradually, increasing to 31 percent in 1984.

Table 4. Aggregate and per capita amounts and percent distribution of personal health care expenditures, by source of funds: Selected calendar years 1929-84.

| Year | Total | Direct patient payments | Third parties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| All third parties | Private health insurance | Other private funds | Government | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Total | Federal | State and local | ||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||

| 1929 | $3.2 | $2.8 | $.4 | (1) | $.1 | $.3 | $.1 | $.2 |

| 1935 | 2.7 | 2.2 | .5 | (1) | .1 | .4 | .1 | .3 |

| 1940 | 3.5 | 2.9 | .7 | (1) | .1 | .6 | .1 | .4 |

| 1950 | 10.9 | 7.1 | 3.8 | $.9 | .3 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| 1955 | 15.7 | 9.1 | 6.6 | 2.5 | .4 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 2.0 |

| 1960 | 23.7 | 13.0 | 10.7 | 5.0 | .5 | 5.2 | 2.2 | 3.0 |

| 1965 | 35.9 | 18.5 | 17.3 | 8.7 | .8 | 7.9 | 3.6 | 4.3 |

| 1967 | 44.5 | 19.0 | 25.5 | 9.6 | .8 | 15.1 | 9.5 | 5.6 |

| 1970 | 65.4 | 26.5 | 38.9 | 15.3 | 1.1 | 22.4 | 14.5 | 7.9 |

| 1975 | 117.1 | 38.1 | 79.0 | 31.2 | 1.6 | 46.3 | 31.4 | 14.9 |

| 1980 | 219.1 | 62.5 | 156.7 | 67.3 | 2.6 | 86.7 | 62.5 | 24.3 |

| 1981 | 253.4 | 70.8 | 182.6 | 78.8 | 3.0 | 100.8 | 74.2 | 26.5 |

| 1982 | 284.9 | 77.2 | 207.7 | 91.0 | 3.4 | 113.4 | 83.9 | 29.5 |

| 1983 | 315.2 | 86.4 | 228.8 | 100.3 | 3.7 | 124.8 | 92.9 | 31.9 |

| 1984 | 341.8 | 95.4 | 246.5 | 107.2 | 3.9 | 135.4 | 101.1 | 34.3 |

| Per capita amount | ||||||||

| 1929 | 26 | 23 | 3 | (1) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 1935 | 21 | 17 | 4 | (1) | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| 1940 | 26 | 21 | 5 | (1) | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| 1950 | 70 | 46 | 24 | 6 | 2 | 16 | 7 | 8 |

| 1955 | 93 | 54 | 39 | 15 | 3 | 21 | 10 | 12 |

| 1960 | 129 | 71 | 58 | 27 | 3 | 28 | 12 | 16 |

| 1965 | 177 | 91 | 85 | 43 | 4 | 39 | 18 | 21 |

| 1967 | 214 | 91 | 123 | 46 | 4 | 73 | 46 | 27 |

| 1970 | 305 | 124 | 182 | 72 | 5 | 105 | 68 | 37 |

| 1975 | 522 | 170 | 352 | 139 | 7 | 206 | 140 | 66 |

| 1980 | 929 | 265 | 664 | 285 | 11 | 368 | 265 | 103 |

| 1981 | 1,063 | 297 | 766 | 331 | 13 | 423 | 311 | 111 |

| 1982 | 1,184 | 321 | 863 | 378 | 14 | 471 | 349 | 122 |

| 1983 | 1,297 | 355 | 941 | 413 | 15 | 514 | 382 | 131 |

| 1984 | 1,394 | 389 | 1,005 | 437 | 16 | 552 | 412 | 140 |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||

| 1929 | 100.0 | 88.4 | 11.6 | (1) | 2.6 | 9.0 | 2.7 | 6.3 |

| 1935 | 100.0 | 82.4 | 17.6 | (1) | 2.8 | 14.7 | 3.4 | 11.3 |

| 1940 | 100.0 | 81.3 | 18.7 | (1) | 2.6 | 16.1 | 4.1 | 12.0 |

| 1950 | 100.0 | 65.5 | 34.5 | 9.1 | 2.9 | 22.4 | 10.4 | 12.0 |

| 1955 | 100.0 | 58.1 | 41.9 | 16.1 | 2.8 | 23.0 | 10.5 | 12.5 |

| 1960 | 100.0 | 54.9 | 45.1 | 21.1 | 2.3 | 21.8 | 9.3 | 12.5 |

| 1965 | 100.0 | 51.6 | 48.4 | 24.2 | 2.2 | 22.0 | 10.1 | 11.9 |

| 1967 | 100.0 | 42.6 | 57.4 | 21.6 | 1.9 | 33.9 | 21.3 | 12.6 |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 40.5 | 59.5 | 23.4 | 1.7 | 34.3 | 22.2 | 12.1 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 32.5 | 67.5 | 26.7 | 1.3 | 39.5 | 26.8 | 12.7 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 28.5 | 71.5 | 30.7 | 1.2 | 39.6 | 28.5 | 11.1 |

| 1981 | 100.0 | 27.9 | 72.1 | 31.1 | 1.2 | 39.8 | 29.3 | 10.5 |

| 1982 | 100.0 | 27.1 | 72.9 | 31.9 | 1.2 | 39.8 | 29.5 | 10.3 |

| 1983 | 100.0 | 27.4 | 72.6 | 31.8 | 1.2 | 39.6 | 29.5 | 10.1 |

| 1984 | 100.0 | 27.9 | 72.1 | 31.3 | 1.2 | 39.6 | 29.6 | 10.0 |

Included with direct payments; separate data are not available.

NOTE: Based on July 1 social security area population estimates.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary.

A large proportion of spending for hospital care and physicians' services is paid by private health insurance. In 1960, private insurance paid for 36 percent of hospital care, the first type of service to be covered extensively; that share reached 41 percent by 1965 (Table 5). When Medicare and Medicaid were established in 1966, hospital care spending increased dramatically, and the portion paid by private insurance, although growing in dollar terms, dropped to less than 34 percent by 1967. Between 1967 and 1983, the insurance share of hospital expenditures grew to 38 percent, because consumers sought more depth in their hospital coverage. This share dropped slightly in 1984 to 37 percent. Extension of coverage beyond surgical procedures in recent years has led to a higher share of physicians' services being reimbursed by private insurance. This share rose from 31 percent in 1965 to 44 percent in 1984 (Table 6).

Table 5. Aggregate and per capita amounts and percent distribution of expenditures for hospital care, by source of funds: Selected calendar years 1950-84.

| Year | Total | Direct patient payments | Third parties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| All third parties | Private health insurance | Other private funds | Government | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Total | Federal | State and local | ||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||

| 1950 | $3.9 | $1.2 | $2.7 | $.7 | $.1 | $1.9 | (1) | (1) |

| 1955 | 5.9 | 1.3 | 4.6 | 1.7 | .2 | 2.7 | (1) | (1) |

| 1960 | 9.1 | 1.8 | 7.3 | 3.3 | .2 | 3.8 | (1) | (1) |

| 1965 | 14.0 | 2.3 | 11.6 | 5.7 | .3 | 5.6 | $2.4 | $3.1 |

| 1967 | 18.4 | 1.9 | 16.4 | 6.2 | .3 | 10.0 | 6.3 | 3.7 |

| 1970 | 28.0 | 3.2 | 24.8 | 9.7 | .4 | 14.7 | 9.5 | 5.1 |

| 1975 | 52.4 | 4.2 | 48.2 | 18.8 | .6 | 28.9 | 20.1 | 8.8 |

| 1980 | 101.3 | 7.5 | 93.8 | 38.6 | 1.0 | 54.2 | 41.1 | 13.1 |

| 1981 | 117.9 | 9.2 | 108.7 | 44.7 | 1.3 | 62.8 | 48.6 | 14.1 |

| 1982 | 134.7 | 10.3 | 124.4 | 51.8 | 1.4 | 71.2 | 55.4 | 15.8 |

| 1983 | 148.8 | 12.8 | 136.1 | 56.6 | 1.6 | 77.8 | 60.6 | 17.2 |

| 1984 | 157.9 | 13.7 | 144.2 | 58.2 | 1.6 | 84.3 | 65.6 | 18.7 |

| Per capita amount | ||||||||

| 1950 | 25 | 7 | 17 | 4 | 1 | 12 | (1) | (1) |

| 1955 | 35 | 8 | 27 | 10 | 1 | 16 | (1) | (1) |

| 1960 | 49 | 10 | 40 | 18 | 1 | 20 | (1) | (1) |

| 1965 | 69 | 12 | 57 | 28 | 2 | 27 | 12 | 16 |

| 1967 | 89 | 9 | 79 | 30 | 1 | 48 | 30 | 18 |

| 1970 | 131 | 15 | 116 | 45 | 2 | 68 | 45 | 24 |

| 1975 | 233 | 19 | 215 | 84 | 3 | 129 | 90 | 39 |

| 1980 | 429 | 32 | 398 | 163 | 4 | 230 | 174 | 56 |

| 1981 | 495 | 38 | 456 | 188 | 5 | 263 | 204 | 59 |

| 1982 | 560 | 43 | 517 | 215 | 6 | 296 | 230 | 66 |

| 1983 | 612 | 53 | 560 | 233 | 6 | 320 | 249 | 71 |

| 1984 | 644 | 56 | 588 | 237 | 7 | 344 | 268 | 76 |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||

| 1950 | 100.0 | 29.9 | 70.1 | 17.7 | 3.5 | 48.9 | (1) | (1) |

| 1955 | 100.0 | 22.3 | 77.7 | 28.5 | 3.0 | 46.2 | (1) | (1) |

| 1960 | 100.0 | 19.8 | 80.2 | 36.3 | 2.5 | 41.3 | (1) | (1) |

| 1965 | 100.0 | 16.8 | 83.2 | 41.1 | 2.2 | 39.9 | 17.4 | 22.5 |

| 1967 | 100.0 | 10.6 | 89.4 | 33.5 | 1.6 | 54.3 | 34.2 | 20.1 |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 11.4 | 88.6 | 34.6 | 1.6 | 52.4 | 34.1 | 18.4 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 7.9 | 92.1 | 35.9 | 1.1 | 55.1 | 38.4 | 16.7 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 7.4 | 92.6 | 38.1 | 1.0 | 53.5 | 40.6 | 13.0 |

| 1981 | 100.0 | 7.8 | 92.2 | 37.9 | 1.1 | 53.2 | 41.3, | 12.0 |

| 1982 | 100.0 | 7.6 | 92.4 | 38.5 | 1.0 | 52.8 | 41.1 | 11.7 |

| 1983 | 100.0 | 8.6 | 91.4 | 38.1 | 1.1 | 52.3 | 40.7 | 11.6 |

| 1984 | 100.0 | 8.7 | 91.3 | 36.9 | 1.0 | 53.4 | 41.6 | 11.9 |

Separate data are not available.

NOTE: Based on July 1 social security area population estimates.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary.

Table 6. Aggregate and per capita amounts and percent distribution of expenditures for physicians' services, by source of funds: Selected calendar years 1950-84.

| Year | Total | Direct patient payments | Third parties | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| All third parties | Private health insurance | Other private funds | Government | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Total | Federal | State and local | ||||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||

| 1950 | $2.7 | $2.3 | $.5 | $.3 |

|

(1) |

|

$.1 | (2) | (2) |

| 1955 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 1.1 | .9 | .2 | (2) | (2) | |||

| 1960 | 5.7 | 3.7 | 2.0 | 1.6 | .4 | (2) | (2) | |||

| 1965 | 8.5 | 5.2 | 3.3 | 2.7 | .6 | $.2 | $.4 | |||

| 1967 | 10.1 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.4 | .7 | |||

| 1970 | 14.3 | 6.5 | 7.8 | 4.8 | 3.0 | 2.1 | .9 | |||

| 1975 | 24.9 | 8.5 | 16.4 | 9.9 | 6.6 | 4.7 | 1.9 | |||

| 1980 | 46.8 | 14.3 | 32.6 | 19.9 | 12.6 | 9.6 | 3.0 | |||

| 1981 | 54.8 | 16.3 | 38.5 | 23.4 | 15.0 | 11.7 | 3.3 | |||

| 1982 | 61.8 | 17.7 | 44.1 | 27.1 | 16.9 | 13.4 | 3.6 | |||

| 1983 | 68.4 | 18.9 | 49.5 | 30.1 | 19.3 | 15.6 | 3.8 | |||

| 1984 | 75.4 | 21.0 | 54.4 | 33.5 | 20.9 | 16.9 | 4.0 | |||

| Per capita amount | ||||||||||

| 1950 | 18 | 15 | 3 | 2 |

|

(1) |

|

1 | (2) | (2) |

| 1955 | 22 | 15 | 7 | 5 | 1 | (2) | (2) | |||

| 1960 | 31 | 20 | 11 | 9 | 2 | (2) | (2) | |||

| 1965 | 42 | 26 | 16 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 1967 | 49 | 25 | 24 | 14 | 10 | 7 | 3 | |||

| 1970 | 67 | 30 | 37 | 23 | 14 | 10 | 4 | |||

| 1975 | 111 | 38 | 73 | 44 | 29 | 21 | 8 | |||

| 1980 | 199 | 61 | 138 | 84 | 53 | 41 | 13 | |||

| 1981 | 230 | 68 | 162 | 98 | 63 | 49 | 14 | |||

| 1982 | 257 | 74 | 183 | 113 | 70 | 56 | 15 | |||

| 1983 | 282 | 78 | 204 | 124 | 80 | 64 | 15 | |||

| 1984 | 307 | 86 | 222 | 136 | 85 | 69 | 16 | |||

| Percent distribution | ||||||||||

| 1950 | 100.0 | 83.2 | 16.8 | 11.4 | .3 | 5.2 | (2) | (2) | ||

| 1955 | 100.0 | 69.8 | 30.2 | 23.2 | .2 | 6.7 | (2) | (2) | ||

| 1960 | 100.0 | 65.4 | 34.6 | 28.0 | .2 | 6.4 | (2) | (2) | ||

| 1965 | 100.0 | 61.6 | 38.4 | 31.4 | .1 | 6.9 | 1.8 | 5.1 | ||

| 1967 | 100.0 | 50.3 | 49.7 | 29.4 | .1 | 20.2 | 13.6 | 6.6 | ||

| 1970 | 100.0 | 45.4 | 54.6 | 33.6 | .1 | 20.9 | 14.9 | 6.0 | ||

| 1975 | 100.0 | 34.1 | 65.9 | 39.5 | .1 | 26.3 | 18.8 | 7.6 | ||

| 1980 | 100.0 | 30.5 | 69.5 | 42.5 | (1) | 26.9 | 20.6 | 6.3 | ||

| 1981 | 100.0 | 29.7 | 70.3 | 42.8 | (1) | 27.4 | 21.4 | 6.1 | ||

| 1982 | 100.0 | 28.7 | 71.3 | 43.8 | .1 | 27.4 | 21.7 | 5.7 | ||

| 1983 | 100.0 | 27.7 | 72.3 | 44.0 | .1 | 28.3 | 22.8 | 5.5 | ||

| 1984 | 100.0 | 27.8 | 72.2 | 44.4 | .1 | 27.8 | 22.4 | 5.3 | ||

Expenditures amount to less than $50 million, less than $.50 per capita, or less than .5 percent of the total.

Separate data are not available.

NOTE: Based on July 1 social security area population estimates.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary.

Although insurance coverage for other health care services is growing, it has been more limited (Table 7). Dental care is one example. Enrollment for dental benefits rose over 50 percent between 1976 and 1979 to a total of 60.3 million persons (Carroll and Arnett, 1981). Insurance paid for about 33 percent of all dental expenditures in 1984. Vision care benefits, although not large in dollar terms, also has experienced significant growth in recent years.

Table 7. Aggregate and per capita amounts and percent distribution of personal health care other than hospital care and physicians' services, by source of funds: Selected calendar years 1950-84.

| Year | Total | Direct patient payments | Third parties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| All third parties | Private health insurance | Other private funds | Government | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Total | Federal | State and local | ||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||

| 1950 | $4.3 | $3.7 | $.6 | (1) | $.2 | $.4 | (2) | (2) |

| 1955 | 6.1 | 5.2 | .9 | (1) | .2 | .6 | (2) | (2) |

| 1960 | 8.9 | 7.5 | 1.4 | $.1 | .3 | 1.0 | (2) | (2) |

| 1965 | 13.4 | 10.9 | 2.5 | .3 | .5 | 1.7 | $1.0 | $.7 |

| 1967 | 16.0 | 11.9 | 4.1 | .5 | .5 | 3.0 | 1.8 | 1.2 |

| 1970 | 23.1 | 16.8 | 6.3 | .8 | .6 | 4.8 | 2.9 | 1.9 |

| 1975 | 39.8 | 25.4 | 14.4 | 2.6 | 1.0 | 10.8 | 6.6 | 4.2 |

| 1980 | 71.0 | 40.7 | 30.3 | 8.8 | 1.6 | 19.9 | 11.7 | 8.2 |

| 1981 | 80.7 | 45.3 | 35.3 | 10.6 | 1.8 | 23.0 | 13.9 | 9.1 |

| 1982 | 88.4 | 49.2 | 39.3 | 12.1 | 1.9 | 25.3 | 15.1 | 10.1 |

| 1983 | 97.9 | 54.6 | 43.3 | 13.5 | 2.1 | 27.6 | 16.7 | 10.9 |

| 1984 | 108.6 | 60.7 | 47.9 | 15.5 | 2.3 | 30.1 | 18.6 | 11.5 |

| Per capita amount | ||||||||

| 1950 | 28 | 24 | 4 | (1) | 1 | 3 | (2) | (2) |

| 1955 | 36 | 31 | 5 | (1) | 1 | 4 | (2) | (2) |

| 1960 | 48 | 41 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| 1965 | 66 | 54 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 5 | 3 |

| 1967 | 77 | 57 | 20 | 2 | 3 | 15 | 9 | 6 |

| 1970 | 108 | 78 | 29 | 4 | 3 | 22 | 13 | 9 |

| 1975 | 177 | 113 | 64 | 11 | 4 | 48 | 29 | 19 |

| 1980 | 301 | 173 | 128 | 37 | 7 | 84 | 50 | 35 |

| 1981 | 338 | 190 | 148 | 44 | 7 | 96 | 58 | 38 |

| 1982 | 367 | 204 | 163 | 50 | 8 | 105 | 63 | 42 |

| 1983 | 403 | 225 | 178 | 56 | 9 | 114 | 69 | 45 |

| 1984 | 443 | 248 | 195 | 63 | 9 | 123 | 76 | 47 |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||

| 1950 | 100.0 | 86.2 | 13.8 | (1) | 4.2 | 9.6 | (2) | (2) |

| 1955 | 100.0 | 85.6 | 14.4 | (1) | 4.1 | 10.3 | (2) | (2) |

| 1960 | 100.0 | 83.9 | 16.1 | 1.1 | 3.3 | 11.6 | (2) | (2) |

| 1965 | 100.0 | 81.6 | 18.4 | 1.9 | 3.5 | 13.0 | 7.8 | 5.2 |

| 1967 | 100.0 | 74.5 | 25.5 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 19.1 | 11.3 | 7.7 |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 72.9 | 27.1 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 20.8 | 12.4 | 8.3 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 63.9 | 36.1 | 6.5 | 2.5 | 27.1 | 16.5 | 10.6 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 57.3 | 42.7 | 12.4 | 2.2 | 28.0 | 16.5 | 11.5 |

| 1981 | 100.0 | 56.2 | 43.8 | 13.1 | 2.2 | 28.5 | 17.2 | 11.3 |

| 1982 | 100.0 | 55.6 | 44.4 | 13.6 | 2.2 | 28.6 | 17.1 | 11.4 |

| 1983 | 100.0 | 55.8 | 44.2 | 13.8 | 2.1 | 28.2 | 17.1 | 11.2 |

| 1984 | 100.0 | 55.9 | 44.1 | 14.3 | 2.1 | 27.7 | 17.1 | 10.6 |

Included with direct payments; separate data are not available.

Disaggregated data not available.

NOTE: Based on July 1 social security area population estimates.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary.

Public expenditures

Government programs spent $135 billion for personal health care services in 1984, an 8.5 percent increase over 1983. Public programs financed almost 40 percent of all personal health care expenditures, including 53 percent of all hospital care, 28 percent of all physician services, and 49 percent of all nursing home care.

Federal expenditures of $101 billion for personal health care accounted for three-quarters of the public outlay and 30 percent of the total funding for personal health. Sixty-five percent of these Federal funds went toward purchases of hospital care; 17 percent, for physician services; and 9 percent, for nursing home care.

State and local governments financed $34 billion (10 percent) of personal health care services in 1984. Purchases of hospital services accounted for 55 percent of State and local expenditures; physician services, 12 percent; and nursing home care, 20 percent.

Public funding of personal health care changed dramatically with the advent of the Medicare and Medicaid programs. In 1965, 22 percent of all personal health care spending was publicly financed. Implementation of the Medicare and Medicaid programs rapidly boosted the proportion of public funding of personal health care to 34 percent in 1967. By 1980, public expenditures reached 40 percent and remained at that level through 1984. Federal funding has accounted for all of the growth in the proportion of public funds financing personal health care; the proportion of State and local funds actually declined over the period 1967-84, from 13 percent to 10 percent.

From 1967 to 1984, the proportion of public funding to hospitals has remained stable (between 52 and 55 percent), with Federal funds (the Medicare program, specifically) accounting for a steadily increasing proportion of those public funds. During the same period, the proportion of public funding for physicians' services grew from 20 percent in 1967 to 28 percent in 1984. Once again, most of that increase can be attributed to the Medicare program.

Public financing of nursing home care grew from 34 percent in 1965 to 49 percent in 1967, peaked at 56 percent in 1975 and 1979, and declined to 49 percent in 1984. Public financing for nursing home care comes predominantly through the Medicaid program, where costs are shared between the Federal, State and local governments.

Public financing for health care services comes from a number of Federal, State, and local programs (Table 8). Some, such as the Veterans' Administration and the U.S. Department of Defense, provide services directly through networks of hospitals, clinics, and nursing homes. The same agencies also pay public and private facilities to provide services. In the Medicare program, the Federal Government acts as an insurer, providing funds for medical care for eligible aged and disabled people. In other programs, Federal funds flow to State governments, which contribute additional funds. States may administer a medical program, as in the case of Medicaid, or may let funds flow through to local government agencies, as is done with maternal and child health and other community-related grants. States also fund health programs independently in State-run hospitals, or through public assistance vendor payments for individuals not covered by Medicaid.

Table 8. Expenditures for health services and supplies under public programs, by program and type of expenditure: Calendar year 1984.

| Program area | Total | Personal health care | Administration | Public health activities | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total | Hospital care | Physicians' services | Dentists' services | Other professional services | Drugs and sundries | Eyeglasses and appliances | Nursing home care | Other personal health care | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||||

| Public and private spending | $371.6 | $341.8 | $157.9 | $75.4 | $25.1 | $8.8 | $25.8 | $7.4 | $32.0 | $9.4 | $19.1 | $10.7 |

| All public programs | 151.2 | 135.4 | 84.3 | 20.9 | .5 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 15.7 | 7.5 | 5.2 | 10.7 |

| Federal programs | 105.4 | 101.1 | 65.6 | 16.9 | .3 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 8.8 | 5.1 | 2.9 | 1.4 |

| State and local programs | 45.9 | 34.3 | 18.7 | 4.0 | .3 | .6 | 1.2 | .1 | 6.9 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 9.3 |

| Medicare1 (Federal) | 64.6 | 63.1 | 44.4 | 14.6 | — | 1.7 | — | 1.0 | .6 | .9 | 1.6 | — |

| Medicaid2 | 38.7 | 36.7 | 14.1 | 3.1 | .5 | .9 | 2.1 | — | 13.9 | 2.3 | 2.0 | — |

| Federal | 20.9 | 19.7 | 7.4 | 1.7 | .2 | .5 | 1.2 | — | 7.5 | 1.2 | 1.2 | — |

| State and local | 17.8 | 17.0 | 6.7 | 1.4 | .2 | .4 | .9 | — | 6.4 | 1.1 | .8 | — |

| Other public assistance programs | 2.0 | 2.0 | .9 | .2 | .0 | .0 | .1 | — | .6 | .1 | — | — |

| Federal | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| State and local | 2.0 | 2.0 | .9 | .2 | .0 | .0 | .1 | — | .6 | .1 | — | — |

| Veterans medical care | 8.3 | 8.2 | 6.7 | .1 | .0 | — | .0 | .1 | .7 | .7 | .1 | — |

| Defense Department medical care3 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 5.4 | .3 | .0 | — | .0 | — | — | 1.1 | .1 | — |

| Workers compensation | 7.1 | 5.7 | 2.9 | 2.4 | — | .2 | .1 | .1 | — | — | 1.5 | — |

| Federal | .3 | .3 | .2 | .1 | — | .0 | .0 | .0 | — | — | .0 | — |

| State and local | 6.8 | 5.4 | 2.7 | 2.3 | — | .2 | .1 | .1 | — | — | 1.5 | — |

| State and local hospitals4 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 8.4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |