Abstract

National health expenditures are projected to grow to $640 billion by 1990, 11.3 percent of the gross national product. Growth in health spending is expected to moderate to an 8.7 percent average annual rate from 1984 to 1990, compared with a 12.6 percent rate from 1978 to 1984. These projections assume lower estimates of overall economic price growth, lower use of hospital care, and increased use of less expensive types of care. A preliminary analysis of demographic factors reveals that the aging of the population has almost as great an impact as the growth in total population on projected expenditures for many types of health care services.

Introduction

The health care system continues to change in the delivery, utilization, and financing of health care in response to public and private cost-containment efforts. Pressures are being placed on the health industry to minimize costs by moving to less intensive and less expensive modes of care. Added to this is an increased awareness and cost consciousness on the part of the consumer. The impact of these factors is most evident in the inpatient hospital sector where use continues to decline, attributable in part to a shift in services to less costly alternative sites, but also attributable to the elimination of unnecessary services. As competition for the health dollar intensifies, both within and among the various segments of the health care industry, new marketing strategies are appearing (Coddington, Palmquist, and Trollinger, 1985). Prepayment plans which are combinations of providers (frequently hospitals) and payers (frequently insurers), are an example of these strategies. These responses by providers and payers alike are expected to bring down health care expenditure growth.

Another downward pressure affecting health expenditure growth is a projected moderation in economy-wide price increases. However, health expenditures as a percent of gross national product (GNP) will continue to grow. A force likely to put upward pressure on health care spending is the aging of the population. In the future, demographic factors are expected to have an increasing impact on health spending. These and other emerging trends have been incorporated into the projections. The net result of all these effects is a slowing of expenditure growth during the period 1984-90 to an average annual rate of 8.7 percent (Table 1).

Table 1. Highlights of national health expenditures, by type of expenditure: Selected years 1984-90.

| Type of expenditure | 1984 | 1986 | 1988 | 1990 | Average annual growth rates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 1978-84 | 1984-90 | |||||

| Amount in billions | Percent | |||||

| Total health expenditures | $387 | $454 | $540 | $640 | 12.8 | 8.7 |

| Public share | 160 | 187 | 224 | 267 | 13.0 | 8.9 |

| Private share | 227 | 267 | 316 | 372 | 12.8 | 8.6 |

| Hospital care | 158 | 181 | 214 | 254 | 13.4 | 8.2 |

| Community | 134 | 154 | 184 | 220 | 14.9 | 8.6 |

| Inpatient | 114 | 126 | 148 | 174 | 14.4 | 7.3 |

| Outpatient | 20 | 28 | 36 | 46 | 18.4 | 14.5 |

| Physicians' services | 75 | 90 | 110 | 132 | 13.5 | 9.8 |

| Dentists' services | 25 | 31 | 37 | 42 | 13.0 | 9.0 |

| Prescription drugs and medical sundries | 26 | 31 | 37 | 44 | 8.9 | 9.1 |

| Nursing home care | 32 | 39 | 47 | 56 | 14.2 | 9.8 |

| Per capita amount | ||||||

| Total health expenditures | $1,580 | $1,812 | $2,119 | $2,459 | 11.7 | 7.7 |

| Percent of gross national product | ||||||

| Total health expenditures | 10.6 | 10.8 | 10.9 | 11.3 | 2.7 | 1.1 |

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Projection scenario

These projections are based on past trends and relationships observed in the historical estimates of national health expenditures (Levit, Lazenby, Waldo et al., 1985). Variation in national health care spending is attributable to many factors, including economic conditions, sociodemographic changes, and public and private policy shifts. Trend forecasts that reflect average tendencies are used in these projections. The model incorporates economic, actuarial, statistical, demographic, and judgmental factors into a single, integrated framework. It consists of four interrelated components: a five-factor model of expenditure growth, supply variables, a source-of-funds module, and a module for net cost of insurance and program administration costs.

Estimates of health expenditure growth are projected on the basis of the five-factor model. The five factors are population, general price level as measured by the GNP deflator, price relatives that measure the difference between medical service prices and the general inflation rate, units of service consumed per capita, and a residual interpreted as real inputs per unit of service. As a prelude to projecting expenditures to future years, historical expenditures since 1965 are modeled on these five factors, with the residual term accounting for any change not explained by the other four factors. For the projection to future years, predictions of many of the five factors are taken from other forecasters, for example, the economic, population, and manpower assumptions. Other factors such as utilization and the residual are based on analytical judgment which, in turn, is based in part on historical experience. These components are explained in more detail in the “Projection methodology” section.

Economic assumptions

These projections are based on assumptions in the Board of Trustees: 1985 Annual Report of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance Trust Fund. Under these assumptions, the economy will grow at a constant rate of about 3.0 percent per year throughout the projection period 1984-90 (Table 2).

Table 2. Historical estimates and projections of gross national product, inflation, and population: Selected years 1950-90.

| Calendar year | Gross national product (GNP) | Consumer Price Index1,2 (CPI)—all items wage earners (1967 = 100.0) |

Total3 population in thousands July 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Current dollars in billions | 1972 dollars in billions | Implicit price deflator (1972 = 100.0) |

|||

| Historical estimates | |||||

| 1950 | $286.5 | $534.8 | 53.5 | 72.1 | 157,313 |

| 1955 | 400.1 | 657.5 | 60.8 | 80.3 | 174,028 |

| 1960 | 506.5 | 737.2 | 68.7 | 88.6 | 188,943 |

| 1965 | 691.0 | 929.3 | 74.4 | 94.4 | 203,032 |

| 1970 | 992.7 | 1,085.6 | 91.4 | 116.3 | 214,034 |

| 1974 | 1,434.2 | 1,246.3 | 115.1 | 147.8 | 222,435 |

| 1975 | 1,549.2 | 1,231.7 | 125.7 | 161.3 | 224,484 |

| 1978 | 2,163.8 | 1,438.5 | 150.4 | 195.3 | 230,835 |

| 1980 | 2,631.7 | 1,475.0 | 178.4 | 246.9 | 235,885 |

| 1981 | 2,957.8 | 1,512.2 | 195.6 | 272.2 | 238,299 |

| 1982 | 3,069.2 | 1,480.0 | 207.4 | 288.5 | 240,743 |

| 1983 | 3,304.8 | 1,534.7 | 215.3 | 297.3 | 243,066 |

| 1984 | 3,662.8 | 1,639.3 | 223.4 | 307.6 | 245,226 |

| Projections | |||||

| 1986 | 4,207.8 | 1,737.6 | 242.2 | 334.6 | 249,624 |

| 1988 | 4,934.8 | 1,842.8 | 267.8 | 370.0 | 253,997 |

| 1990 | 5,671.8 | 1,943.2 | 291.9 | 403.3 | 258,277 |

| Average annual percent change | |||||

| Selected periods | |||||

| 1950-55 | 6.9 | 4.2 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.0 |

| 1955-60 | 4.8 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 1.7 |

| 1960-65 | 6.4 | 4.7 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| 1965-70 | 7.5 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 1.1 |

| 1970-75 | 9.3 | 2.6 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 1.0 |

| 1975-80 | 11.2 | 3.7 | 7.3 | 8.9 | 1.0 |

| 1980-85 | 8.2 | 2.8 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 1.0 |

| 1985-90 | 7.7 | 2.8 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 0.9 |

| 1974-84 | 9.8 | 2.8 | 6.9 | 7.6 | 1.0 |

| 1978-84 | 9.2 | 2.2 | 6.8 | 7.9 | 1.0 |

| 1984-88 | 7.7 | 3.0 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 0.9 |

| 1984-90 | 7.6 | 2.9 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 0.9 |

| 1982-84 | 9.2 | 5.2 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 0.9 |

| 1984-86 | 7.2 | 3.0 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 0.9 |

| 1986-88 | 8.3 | 3.0 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 0.9 |

| 1988-90 | 7.2 | 2.7 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 0.8 |

Historical estimates are reported in the Economic Report of the President, (1985). Projection growth rates are from Board of Trustees, Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance Trust Fund, Mar. 1985. Il-B assumptions were used. The average annual rate of growth in GNP for 1984-90 used in this projection is within 0.3 percentage points of the rate used by the private consulting firm of Data Resources, Inc.: U.S. Long-Term Review. Lexington, Mass., Fall 1985.

The CPI is shown for comparison only. The implicit price deflator for GNP is used in the projection process to reflect cost pressures external to health care industry.

Historical estimates and projections of population are from Wade (1985). Alternative II (intermediate) assumptions for population growth were used.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

One of the most important factors explaining growth in national health expenditures is movement in economy-wide price levels as measured by the GNP implicit price deflator. Inflation is expected to recede to a 4.6-percent average annual growth, one-third slower than the rate experienced during the period 1974-84. Expressed in other terms, prices are assumed to increase from their present levels, but at a rate two-thirds of that experienced from 1974 to 1984. The forecasted deceleration in economy-wide inflation is significant because approximately 60 percent of growth in health care spending can be accounted for by growth in the overall price level (Table 3).

Table 3. Factors accounting for growth in expenditures in selected categories of national health expenditures: 1974-841.

| Factor | Community hospital care2 | Physicians' services | Dentists' services | Nursing home care excluding ICFMR | Total personal Health care | Total national health expenditures | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Inpatient expenses | Outpatient expenses | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Inpatient days | Admissions | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Percent distribution | ||||||||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Economy-wide factors | ||||||||

| General inflation (GNP deflator) | 51.2 | 51.5 | 40.8 | 52.8 | 54.8 | 53.2 | 55.2 | 55.6 |

| Aggregate population growth | 7.3 | 7.5 | 5.8 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 7.6 | 7.9 | 7.9 |

| Health-sector specific factors | ||||||||

| Growth in per capita visits or patient days | -8.5 | -.8 | 10.9 | -7.5 | 4.2 | 15.0 | — | — |

| Growth in real services per visit or per day (intensity) | 33.4 | 25.4 | 29.3 | 27.5 | 22.1 | 15.4 | 321.3 | 322.9 |

| Medical care price increases in excess of general price inflation | 16.6 | 16.4 | 13.2 | 19.7 | 11.1 | 8.8 | 15.6 | 13.6 |

For derivation of the method used to allocate factors, see “Projection methodology” section.

Community hospital expenses are split into inpatient and outpatient expenses using the American Hospital Association procedure.

Because of data limitations, this is growth in real services per capita.

NOTES: ICFMR is intermediate care facility for the mentally retarded. GNP is gross national product.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

In the short-term, to 1986, the economy's growth rate will slow significantly and inflation will move moderately upward (Table 2). Real GNP, national output after adjusting for price change, is projected to slow to a 3.0 percent rate of growth. In 1984, real GNP exhibited its strongest performance since 1951, reaching almost a 7.0 percent rate of growth. The projected deceleration of real GNP by 1986 implies a contraction in the economy's ability to finance increases for all types of goods and services, including health care. Although real growth is predicted to slow dramatically, inflation is expected to increase, but at less than one-half of 1 percent faster than the rate of 3.8 percent for 1982-84.

For the period 1986-88, current dollar GNP is projected to increase at an average annual rate of 8.3 percent. Real GNP growth is predicted to stabilize at an average annual growth rate of 3.0 percent, and inflation to increase modestly to 5.2 percent. For the last years of the projection, 1988 to 1990, growth in GNP, real GNP, and inflation are all forecasted to slow to average annual rates of growth of 7.2, 2.7, and 4.4 percents, respectively.

Population assumptions

Shifts in the composition of the population have been associated with faster growth in health care expenditures. In 1965, 9.3 percent of the Nation's population was 65 years of age or over (Wade, 1985). By 1984, that age group accounted for 11.6 percent of the population, having an annual growth of more than twice that of the population overall, 2.2 percent compared with 1.0 percent. During the same period, the cohorts of persons 75 years of age or over grew at an average annual rate of 2.8 percent. As discussed in more detail in the “Demographics” section, the aging of the population was accompanied by higher use of health services contributing to rapid health expenditure growth.

In the future, the number of persons 75 years of age or over is projected to continue to grow at 3.0 percent annually, compared to less than 0.9 percent for the overall population and less than 0.7 percent for the population under age 65. The portion of the population 65 years of age or over will rise from 11.6 percent in 1984 to 12.6 in 1990. Those 75 years of age or over are predicted to move from a 1984-level of 4.8 percent to 5.4 percent in 1990. The continued shifts in the age composition assumed in these projections will tend to put upward pressure on health expenditure growth for the remainder of the eighties because of the disproportionate use of health care by the elderly (Fisher, 1980; Waldo and Lazenby, 1984).

Health professional assumptions

The number of active physicians is projected to grow from approximately 506,000 in 1984 to 588,000 in 1990, an annual average increase of 2.5 percent, or almost three times the growth in population for the same period (Table 4). The number of active dentists is projected to increase from almost 138,000 in 1984 to more than 150,000 in 1990, a growth rate almost twice that of population growth. All other factors being equal, the increased number of physicians and dentists per capita will tend to cause an increase in use of health services and thus an increase in health expenditures. Price competition may offset some of the potential increases.

Table 4. Historical estimates and projections of active physicians and dentists as of December 31: Selected years 1950-90.

| Year | Number of active physicians | Number of active dentists | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Total | M.D.'s1 | D.O.'s2 | ||

| Historical estimates | ||||

| 1950 | 219,900 | 209,000 | 10,900 | 79,190 |

| 1955 | 240,200 | 228,600 | 11,600 | 84,370 |

| 1960 | 259,400 | 247,300 | 12,200 | 90,120 |

| 1965 | 288,700 | 277,600 | 211,100 | 95,990 |

| 1970 | 326,500 | 314,200 | 12,300 | 102,220 |

| 1974 | 369,900 | 356,200 | 13,700 | 110,400 |

| 1975 | 384,400 | 370,400 | 14,000 | 112,450 |

| 1978 | 424,000 | 408,300 | 15,700 | 120,620 |

| 1980 | 457,500 | 440,400 | 17,100 | 126,240 |

| 1981 | 466,700 | 448,700 | 18,000 | 129,180 |

| 1982 | 479,900 | 461,200 | 18,700 | 132,010 |

| 1983 | 492,900 | 473,200 | 19,700 | 135,120 |

| 1984 | 506,500 | 485,700 | 20,800 | 137,950 |

| Projections | ||||

| 1986 | 534,800 | 511,600 | 23,200 | 143,320 |

| 1988 | 562,000 | 536,300 | 25,700 | 147,410 |

| 1990 | 587,700 | 559,500 | 28,200 | 150,760 |

| Average annual percent change | ||||

| Selected periods | ||||

| 1950-55 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| 1955-60 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| 1960-65 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 3-1.9 | 1.3 |

| 1965-70 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.3 |

| 1970-75 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 2.6 | 1.9 |

| 1975-80 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 2.3 |

| 1980-85 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 5.1 | 2.2 |

| 1985-90 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 5.2 | 1.4 |

| 1984-86 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 5.6 | 1.9 |

| 1986-88 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 5.3 | 1.4 |

| 1988-90 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 4.8 | 1.1 |

| 1984-88 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 5.4 | 1.7 |

| 1965-84 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 1.9 |

| 1974-84 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 4.3 | 2.3 |

| 1984-90 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 5.2 | 1.5 |

Medical doctors.

Doctors of osteopathy.

The decline in the number of active D.O.'s from 1960 to 1965 reflects the granting of approximately 2,400 M.D. degrees to osteopathic physicians who had graduated from the University of California College of Medicine at Irvine. These physicians are included with active M.D.'s beginning in 1962.

SOURCES: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates; (Bureau of Health Professions 1985).

Overview

Outlays for national health expenditures are expected to increase at significantly slower rates from 1984 to 1990 than in the past, both absolutely and in relation to GNP (Table 5). Total spending is projected to increase at an 8.7-percent average annual rate, or at two-thirds of the 12.6 percent rate from 1978 to 1984.

Table 5. National health expenditures and average annual percent change, by source of funds and percent of gross national product (GNP): Selected calendar years 1950-90.

| Calendar year | Gross national product in billions | Total national health expenditures | Private | Public | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Amount in billions | Per capita | Percent of GNP | Amount in billions | Percent of total | Total | Federal | State and local | |||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Amount in billions | Percent of total | Amount in billions | Percent of total | Amount in billions | Percent of total | |||||||

| Historical estimates | ||||||||||||

| 1950 | $286.5 | $12.7 | $82 | 4.4 | $9.2 | 72.8 | $3.4 | 27.2 | $1.6 | 12.8 | $1.8 | 14.4 |

| 1955 | 400.1 | 17.7 | 105 | 4.4 | 13.2 | 74.3 | 4.6 | 25.7 | 2.0 | 11.3 | 2.6 | 14.4 |

| 1960 | 506.5 | 26.9 | 146 | 5.3 | 20.3 | 75.3 | 6.6 | 24.7 | 3.0 | 11.2 | 3.6 | 13.5 |

| 1965 | 691.0 | 41.9 | 207 | 6.1 | 30.9 | 73.8 | 11.0 | 26.2 | 5.5 | 13.2 | 5.5 | 13.0 |

| 1970 | 992.7 | 75.0 | 350 | 7.6 | 47.2 | 63.0 | 27.8 | 37.0 | 17.7 | 23.6 | 10.1 | 13.5 |

| 1974 | 1,434.2 | 116.1 | 522 | 8.1 | 69.1 | 59.5 | 47.0 | 40.5 | 30.4 | 26.2 | 16.6 | 14.3 |

| 1975 | 1,549.2 | 132.7 | 591 | 8.6 | 76.4 | 57.5 | 56.3 | 42.5 | 37.0 | 27.9 | 19.3 | 14.5 |

| 1978 | 2,163.8 | 189.7 | 822 | 8.8 | 110.1 | 58.0 | 79.6 | 42.0 | 53.8 | 28.4 | 25.8 | 13.6 |

| 1980 | 2,631.7 | 247.5 | 1,049 | 9.4 | 142.2 | 57.4 | 105.3 | 42.6 | 71.0 | 28.7 | 34.3 | 13.9 |

| 1981 | 2,957.8 | 285.2 | 1,197 | 9.6 | 164.2 | 57.6 | 121.1 | 42.4 | 83.4 | 29.2 | 37.7 | 13.2 |

| 1982 | 3,069.2 | 321.2 | 1,334 | 10.5 | 186.1 | 57.9 | 135.1 | 42.1 | 93.2 | 29.0 | 41.9 | 13.0 |

| 1983 | 3,304.8 | 355.1 | 1,461 | 10.7 | 207.0 | 58.3 | 148.1 | 41.7 | 102.7 | 28.9 | 45.4 | 12.8 |

| 1984 | 3,662.8 | 387.4 | 1,580 | 10.6 | 227.1 | 58.6 | 160.3 | 41.4 | 111.9 | 28.9 | 48.3 | 12.5 |

| Projections | ||||||||||||

| 1986 | 4,207.8 | 454.2 | 1,820 | 10.8 | 266.9 | 58.8 | 187.3 | 41.2 | 132.1 | 29.1 | 55.2 | 12.2 |

| 1988 | 4,934.8 | 539.9 | 2,126 | 10.9 | 316.0 | 58.5 | 223.8 | 41.5 | 159.7 | 29.6 | 64.1 | 11.9 |

| 1990 | 5,671.8 | 639.6 | 2,476 | 11.3 | 372.4 | 58.2 | 267.2 | 41.8 | 193.4 | 30.2 | 73.8 | 11.5 |

| Average annual percent change | ||||||||||||

| Selected periods | ||||||||||||

| 1950-55 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 5.2 | — | 7.4 | — | 5.8 | — | 4.6 | — | 7.6 | — |

| 1955-60 | 4.8 | 8.7 | 6.8 | — | 9.0 | — | 7.8 | — | 8.5 | — | 6.7 | — |

| 1960-65 | 6.4 | 9.2 | 7.6 | — | 8.8 | — | 10.2 | — | 12.9 | — | 7.6 | — |

| 1965-70 | 7.5 | 12.3 | 11.2 | — | 8.8 | — | 20.4 | — | 26.1 | — | 13.1 | — |

| 1970-75 | 9.3 | 12.1 | 11.0 | — | 10.1 | — | 15.2 | — | 16.0 | — | 13.8 | — |

| 1975-80 | 11.2 | 13.3 | 12.2 | — | 13.2 | — | 13.3 | — | 13.9 | — | 12.2 | — |

| 1980-85 | 8.2 | 11.0 | 10.0 | — | 11.4 | — | 10.6 | — | 11.6 | — | 8.5 | — |

| 1985-90 | 7.7 | 8.9 | 8.0 | — | 8.9 | — | 8.9 | — | 9.5 | — | 7.5 | — |

| 1978-84 | 9.2 | 12.6 | 11.5 | — | 12.8 | — | 12.4 | — | 13.0 | — | 11.0 | — |

| 1984-88 | 7.7 | 8.7 | 7.7 | — | 8.6 | — | 8.7 | — | 9.3 | — | 7.3 | — |

| 1984-86 | 7.2 | 8.3 | 7.3 | — | 8.4 | — | 8.1 | — | 8.6 | — | 6.9 | — |

| 1986-88 | 8.3 | 9.0 | 8.1 | — | 8.8 | — | 9.3 | — | 9.9 | — | 7.8 | — |

| 1988-90 | 7.2 | 8.8 | 7.9 | — | 8.5 | — | 9.3 | — | 10.1 | — | 7.3 | — |

| 1965-84 | 9.2 | 12.4 | 11.3 | — | 11.1 | — | 15.1 | — | 17.1 | — | 12.2 | — |

| 1974-84 | 9.8 | 12.8 | 11.7 | — | 12.6 | — | 13.0 | — | 13.9 | — | 11.3 | — |

| 1984-90 | 7.6 | 8.7 | 7.8 | — | 8.6 | — | 8.9 | — | 9.5 | — | 7.3 | — |

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates; (Levit et al. 1985.)

The four factors accounting for historical growth are economy-wide inflation (56 percent), growth in real services expense per use (23 percent), medical care price increases in excess of overall inflation (13 percent), and population growth (8 percent), (Table 3). The projected decline in general inflation and the likely subsequent impact on health sector specific prices, along with continued restrained growth in government financing and private sector cost-containment efforts should exert substantial downward pressure on health spending for the remainder of the eighties. However, the aging of the population and continued introduction of health-enhancing technologies should cause upward pressure on health spending. The net effect of these pressures and constraints should result in a deceleration in the growth of health spending, especially when one considers that the two price measures alone account for about 70 percent of the growth, and both are predicted to slow in the projection period.

Over the projection period, the ratio of health spending to GNP is projected to increase at an average annual rate of 1.1 percent, or only one-third of that for the period 1978-84. In the short-term, as the economy continues to expand, and the effects of both current law reimbursement reform (for example, the Medicare prospective payment system) and the strong private sector initiatives continue to contain costs, the health care sector's share of GNP should remain fairly stable, increasing slowly from 10.6 percent in 1984 to 10.8 in 1986. A gradual increase in this share is projected for the remainder of the eighties, reaching 11.3 percent in 1990. This proportion can be expected to be higher if the assumption for a relatively strong real GNP growth does not materialize.

During the period 1978 to 1984, current dollar or nominal GNP increased at a 9.2 percent average annual rate, and national health expenditures increased at a 12.6 percent rate (Table 5). This rapid growth in health care spending relative to the Nation's ability to pay for it was a factor that prompted Congress, States, and private industry to develop cost-containment initiatives. Health care markets and institutions are adjusting to these new incentives and constraints, and a new health care environment is emerging. Thus, for the projection period, GNP is predicted to grow at a 7.6 percent average annual rate, and health spending is projected to grow at an 8.7 percent rate. This reflects a narrowing of the differential between growth in health care costs and growth in the overall economy.

Shifts from the historical trend in relative shares of spending going to the various types of health services are occurring (Table 6). They reflect changes in the health care delivery system. The hospital share of personal health care expenditures, which historically had been increasing, decreased from 47.3 percent in 1982 to 46.2 percent in 1984. The hospital share is projected to continue to decline slowly to a 44.4-percent share of the health dollar by 1990. Reforms in the payment systems for hospital care and increasing competition from ambulatory services will result in the deceleration of spending growth for hospital care relative to other services. The reduced demand for inpatient services will be partially offset by increases in both the physician and nursing home shares.

Table 6. Percent distribution of personal health care costs, by type of service: Selected years 1950-90.

| Calendar year | Total | Type of personal health care expenditure | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Hospital care | Physicians' services | Dentists' services | Other professional services | Drugs and medical sundries | Eyeglasses and appliances | Nursing home care | Other health services | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Percent distribution | |||||||||

| Historical estimates | |||||||||

| 1950 | 100.0 | 35.4 | 25.2 | 8.8 | 3.6 | 15.9 | 4.5 | 1.7 | 4.8 |

| 1960 | 100.0 | 38.4 | 24.0 | 8.3 | 3.6 | 15.4 | 3.3 | 2.2 | 4.7 |

| 1965 | 100.0 | 39.0 | 23.6 | 7.8 | 2.9 | 14.4 | 3.3 | 5.8 | 3.2 |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 42.8 | 21.9 | 7.3 | 2.4 | 12.2 | 3.0 | 7.2 | 3.2 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 44.8 | 21.3 | 7.0 | 2.2 | 10.2 | 2.7 | 8.6 | 3.2 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 46.2 | 21.4 | 7.0 | 2.6 | 8.5 | 2.3 | 9.3 | 2.7 |

| 1982 | 100.0 | 47.3 | 21.7 | 6.8 | 2.5 | 7.7 | 2.0 | 9.4 | 2.7 |

| 1984 | 100.0 | 46.2 | 22.1 | 7.3 | 2.6 | 7.6 | 2.2 | 9.4 | 2.8 |

| Projections | |||||||||

| 1986 | 100.0 | 44.9 | 22.5 | 7.6 | 2.7 | 7.7 | 2.2 | 9.7 | 2.8 |

| 1988 | 100.0 | 44.4 | 22.8 | 7.6 | 2.8 | 7.7 | 2.1 | 9.8 | 2.9 |

| 1990 | 100.0 | 44.4 | 23.1 | 7.3 | 2.8 | 7.6 | 2.1 | 9.8 | 2.9 |

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Government financing

The Federal share of total health expenditures has grown slowly but continuously from 23.2 percent in 1967, the first full year of Medicare and Medicaid, to 29.2 percent in 1981, then declined slightly to 28.9 percent in 1984 (Table 5). Medicare's share, the largest single component of Federal health care spending, grew continuously from 1968 to 1984, except for the period of wage and price controls in the early 1970's. Federal Medicaid spending has declined as a share of the total of Federal spending since about 1980, partly because of budget constraints. Other Federal spending, consisting mostly of Federal hospitals, has declined as a share of the total for the last two decades. Continued modest declines in Federal Medicaid and other Federal spending are projected through 1990. Total Federal Medicare costs are projected to be almost $119 billion in 1990 (Table 7); Federal Medicaid costs for 1990 will be nearly $34 billion (Table 8).1

Table 7. Medicare benefit payments, by type of service and administrative expenses: Selected years 1970-901.

| Calendar year | Medicare benefits and administrative expenses | Benefits | Administrate expenses | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Total | Hospital care | Physicians' services | Other professional services2 | Eyeglasses and appliances | Nursing home care | Other personal health care | |||

| Amount in billions | |||||||||

| Historical estimates3 | |||||||||

| 1970 | $7.5 | $7.1 | $5.1 | $1.6 | $0.1 | (5) | $0.3 | (5) | $0.4 |

| 1974 | 13.1 | 12.4 | 9.2 | 2.7 | 0.1 | $0.1 | 0.2 | $0.1 | 0.7 |

| 1975 | 16.3 | 15.6 | 11.5 | 3.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| 1978 | 25.9 | 24.9 | 18.2 | 5.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.0 |

| 1980 | 36.8 | 35.7 | 25.9 | 7.9 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.1 |

| 1981 | 44.7 | 43.5 | 31.4 | 9.7 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.3 |

| 1982 | 52.4 | 51.1 | 36.8 | 11.4 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.3 |

| 1983 | 58.8 | 57.4 | 40.5 | 13.4 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.4 |

| 1984 | 64.6 | 63.1 | 44.4 | 14.6 | 1.7 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.6 |

| Projections4 | |||||||||

| 1986 | 77.5 | 75.7 | 51.9 | 18.7 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.8 |

| 1988 | 95.8 | 93.6 | 64.4 | 22.9 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 2.1 |

| 1990 | 118.6 | 116.2 | 79.6 | 29.0 | 3.2 | 2.0 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 2.5 |

| Average annual percent change | |||||||||

| Selected periods | |||||||||

| 1974-84 | 17.3 | 17.6 | 17.0 | 18.5 | 29.1 | 27.0 | 8.6 | 27.9 | 8.7 |

| 1978-84 | 16.4 | 16.7 | 16.0 | 17.8 | 25.3 | 27.1 | 8.4 | 17.5 | 8.0 |

| 1984-86 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 8.1 | 13.2 | 12.6 | 15.6 | 9.0 | 8.8 | 8.4 |

| 1984-88 | 10.3 | 10.4 | 9.7 | 12.0 | 11.9 | 14.5 | 9.1 | 8.9 | 8.0 |

| 1984-90 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 10.2 | 12.1 | 11.6 | 13 4 | 9.0 | 8.6 | 7.7 |

Service categories used in this table differ from those used in the annual reports of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds. For example, hospital-based home health services appear as hospital care rather than as home health services (which are included in other professional services).

Hospice benefits are included with other professional services. The benefit provision was effective November 1, 1983, and expires October 1, 1986.

Historical data are from Levit et al. (1985).

Projections are derived from Board of Trustees, Federal Hospital Insurance and Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund, Mar. 1985.

Less than $50 million.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 8. Federal share of Medicaid benefits, administrative expenses, and average annual percent change: Selected years 1970-90.

| Calendar year | Total | Benefits | Administrative expenses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in billions | |||

| Historical estimates1 | |||

| 1970 | $3.0 | $2.9 | $0.1 |

| 1974 | 6.4 | 6.1 | 0.3 |

| 1975 | 7.9 | 7.6 | 0.4 |

| 1978 | 11.2 | 10.4 | 0.7 |

| 1980 | 14.5 | 13.6 | 0.8 |

| 1981 | 17.3 | 16.2 | 1.1 |

| 1982 | 18.0 | 17.0 | 1.0 |

| 1983 | 19.3 | 18.3 | 1.1 |

| 1984 | 20.9 | 19.7 | 1.2 |

| Projections | |||

| 1986 | 24.4 | 23.0 | 1.4 |

| 1988 | 28.5 | 27.0 | 1.5 |

| 1990 | 33.7 | 32.0 | 1.6 |

| Average annual percent change | |||

| 1974-84 | 12.6 | 12.4 | 15.4 |

| 1978-84 | 11.0 | 11.2 | 8.7 |

| 1984-86 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 8.5 |

| 1984-88 | 8.1 | 8.2 | 6.4 |

| 1984-90 | 8.3 | 8.5 | 5.6 |

Historical Medicaid financial data on outlays reflect changes in services incurred and cash flow adjustments (Levit et al., 1985).

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Medicare is projected to grow as a fraction of all health care spending largely because the Medicare population is growing faster than the population as a whole, and because longevity is increasing in the Medicare population. A temporary moderation in the rise should occur in 1986 as a result of the freeze on the payments for diagnosis-related groups under part A of Medicare. In this projection scenario, Federal payments for health will rise from almost $112 billion in 1984, just under 13 percent of total Federal budget, to more than $193 billion in 1990, almost 15 percent of the Federal budget.

State and local governments have funded about 13 percent of total health care for the last two decades. A modest decline in the State and local share over the past 4 years is projected to continue through the projection period, resulting in State and local governments paying for 11.5 percent of health care costs.

Private financing

After years of steady decline, the portion of health care financed by the private sector seems to have stabilized at just under 60 percent (Table 5). Prior to the Medicare and Medicaid programs, the private sector financed three-quarters of national health expenditures. Also stabilizing are the components of private financing: patient direct payments, private insurance, and other private payments (philanthropy and industrial inplant health facilities). At first glance, this stability is somewhat surprising in what otherwise might be characterized as a rather tumultuous time in the health care industry. However, the number of persons with private insurance has been reasonably constant for several years, especially for the big expenditure items such as hospital care and physicians' services. Even the movement in the late 1970's to insure for dental and vision care has waned. The cost-containment effort leading to increases in deductibles and coinsurance seems to have had some impact on use of services, but does not seem to have had much net effect on the proportion of health expenditures financed by patient direct payments.

New forms of insurance arrangements have been developed recently, in part as a response to the competitive pressures of cost containment. Health maintenance organizations are a long-standing example of a provider/insurance arrangement. New versions of this type of organization have grown out of the preferred provider movement. Preferred provider organizations (PPO's) are basically a discount system which, in principle, benefits both the purchaser and the provider, one receiving lower cost health services and the other increasing its potential market share. Some of the arrangements have now added an element of prepayment. A growing number of these PPO's are assuming the insurance risk by providing care in return for a set prepaid amount. Examples of this form are Humana's Care Plus and the Managed Premium Preferred Provider Organization (MPPPO), Partners, set up by the Voluntary Hospitals of America and Aetna (Cassak, 1985).

Projections by type of service

Presented here is a discussion of national health expenditures by type of expenditure and sources of payment. Data are presented showing both expenditure and payment levels and the distribution of payment sources (Tables 9 and 10).

Table 9. National health expenditures, by type of expenditure and source of funds: Selected years 1974-90.

| Type of expenditure | Total | Private | Public | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Total | Consumer | Other | |||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

| Total | Patient direct | Health insurance | Total | Federal | State and local | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Amount in billions | |||||||||

| 1974 Total | $116.1 | $69.1 | $64.0 | $36.2 | $27.9 | $5.0 | $47.0 | $30.4 | $16.6 |

| Health services and supplies | 108.6 | 65.8 | 64.0 | 36.2 | 27.9 | 1.7 | 42.9 | 27.8 | 15.1 |

| Personal health care | 101.3 | 62.8 | 61.3 | 36.2 | 25.1 | 1.5 | 38.5 | 25.7 | 12.8 |

| Hospital care | 45.0 | 20.6 | 20.0 | 4.9 | 15.1 | 0.6 | 24.4 | 16.7 | 7.7 |

| Physicians' services | 21.2 | 15.9 | 15.9 | 7.7 | 8.1 | (3) | 5.4 | 3.8 | 1.6 |

| Dentists' services | 7.4 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 6.3 | 0.6 | — | .4 | .2 | .2 |

| Other professional services | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.4 | .4 | (3) | .4 | .2 | .1 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 11.0 | 10.1 | 10.1 | 9.5 | .6 | — | .9 | .4 | .4 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.5 | .1 | — | .2 | .1 | (3) |

| Nursing home care | 8.5 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.8 | .1 | .1 | 4.6 | 2.6 | 2.0 |

| Other health services | 3.1 | .8 | — | — | — | .8 | 2.3 | 1.6 | .7 |

| Program administration and net cost of insurance | 4.7 | 3.0 | 2.8 | — | 2.8 | .2 | 1.7 | 1.0 | .6 |

| Government public health activities | 2.7 | — | — | — | — | — | 2.7 | 1.1 | 1.7 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 7.5 | 3.3 | — | — | — | 3.3 | 4.2 | 2.6 | 1.6 |

| Research2 | 2.8 | .3 | — | — | — | .3 | 2.5 | 2.3 | .3 |

| Construction | 4.7 | 3.1 | — | — | — | 3.1 | 1.6 | .3 | 1.3 |

| 1984 Total | 387.4 | 227.1 | 215.9 | 95.4 | 120.5 | 11.2 | 160.3 | 111.9 | 48.3 |

| Health services and supplies | 371.6 | 220.3 | 215.9 | 95.4 | 120.5 | 4.4 | 151.2 | 105.4 | 45.9 |

| Personal health care | 341.8 | 206.5 | 202.5 | 95.4 | 107.2 | 3.9 | 135.4 | 101.1 | 34.3 |

| Hospital care | 157.9 | 73.5 | 71.9 | 13.7 | 58.2 | 1.6 | 84.3 | 65.6 | 18.7 |

| Physicians' services | 75.4 | 54.5 | 54.4 | 21.0 | 33.5 | (3) | 20.9 | 16.9 | 4.0 |

| Dentists' services | 25.1 | 24.5 | 24.5 | 16.3 | 8.3 | — | .5 | .3 | .3 |

| Other professional services | 8.8 | 6.0 | 5.9 | 3.5 | 2.4 | .1 | 2.8 | 2.2 | .6 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 25.8 | 23.5 | 23.5 | 19.7 | 3.8 | — | 2.4 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 7.4 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 5.5 | .8 | — | 1.2 | 1.1 | .1 |

| Nursing home care | 32.0 | 16.3 | 16.1 | 15.8 | .3 | .2 | 15.7 | 8.8 | 6.9 |

| Other health services | 9.4 | 2.0 | — | — | — | 2.0 | 7.5 | 5.1 | 2.4 |

| Program administration and net cost of insurance | 19.1 | 13.9 | 13.4 | — | 13.4 | .5 | 5.2 | 2.9 | 2.3 |

| Government public health activities | 10.7 | — | — | — | — | — | 10.7 | 1.4 | 9.3 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 15.8 | 6.7 | — | — | — | 6.7 | 9.0 | 6.6 | 2.5 |

| Research2 | 6.8 | .4 | — | — | — | .4 | 6.4 | 5.8 | .6 |

| Construction | 9.0 | 6.4 | — | — | — | 6.4 | 2.6 | .7 | 1.9 |

| 1986 Total | $454.2 | $266.9 | $254.8 | $112.9 | $141.9 | $12.1 | $187.3 | $132.1 | $55.2 |

| Health services and supplies | 437.2 | 260.0 | 254.8 | 112.9 | 141.9 | 5.1 | 177.2 | 124.5 | 52.7 |

| Personal health care | 402.9 | 244.1 | 239.5 | 112.9 | 126.6 | 4.6 | 158.8 | 119.6 | 39.2 |

| Hospital care | 180.8 | 84.4 | 82.5 | 15.7 | 66.8 | 1.9 | 96.4 | 75.7 | 20.6 |

| Physicians' services | 90.5 | 64.4 | 64.4 | 24.4 | 40.0 | (3) | 26.0 | 21.4 | 4.6 |

| Dentists' services | 30.7 | 30.1 | 30.1 | 19.8 | 10.2 | — | .6 | .3 | .3 |

| Other professional services | 10.9 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 4.1 | 3.1 | .1 | 3.6 | 2.8 | .8 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 31.0 | 28.1 | 28.1 | 23.2 | 4.9 | — | 2.9 | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 8.8 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 6.2 | 1.0 | — | 1.6 | 1.4 | .1 |

| Nursing home care | 38.9 | 20.3 | 20.0 | 19.5 | .5 | .3 | 18.6 | 10.4 | 8.2 |

| Other health services | 11.4 | 2.3 | — | — | — | 2.3 | 9.1 | 6.1 | 3.0 |

| Program administration and net cost of insurance | 21.9 | 15.9 | 15.3 | — | 15.3 | .6 | 6.0 | 3.4 | 2.6 |

| Government public health activities | 12.3 | — | — | — | — | — | 12.3 | 1.5 | 10.9 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 17.0 | 6.9 | — | — | — | 6.9 | 10.1 | 7.6 | 2.5 |

| Research | 7.8 | .4 | — | — | — | .4 | 7.4 | 6.7 | .7 |

| Construction | 9.2 | 6.5 | — | — | — | 6.5 | 2.7 | .9 | 1.8 |

| 1988 Total | 539.9 | 316.0 | 302.4 | 133.9 | 168.4 | 13.7 | 223.8 | 159.7 | 64.1 |

| Health services and supplies | 520.8 | 308.4 | 302.4 | 133.9 | 168.4 | 6.0 | 212.4 | 151.1 | 61.3 |

| Personal health care | 481.3 | 290.4 | 285.0 | 133.9 | 151.1 | 5.3 | 191.0 | 145.6 | 45.3 |

| Hospital care | 213.7 | 98.1 | 95.9 | 17.5 | 78.4 | 2.2 | 115.6 | 92.4 | 23.1 |

| Physicians' services | 109.8 | 78.1 | 78.0 | 29.8 | 48.3 | .1 | 31.7 | 26.1 | 5.6 |

| Dentists' services | 36.5 | 35.8 | 35.8 | 23.5 | 12.3 | — | .7 | .3 | .3 |

| Other professional services | 13.3 | 8.8 | 8.7 | 4.8 | 3.9 | .1 | 4.5 | 3.5 | 1.0 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 37.1 | 33.8 | 33.8 | 27.6 | 6.2 | — | 3.3 | 1.7 | 1.6 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 10.3 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 7.1 | 1.2 | — | 2.0 | 1.8 | .2 |

| Nursing home care | 47.0 | 24.8 | 24.5 | 23.7 | .8 | .3 | 22.2 | 12.4 | 9.8 |

| Other health services | 13.7 | 2.6 | — | — | — | 2.6 | 11.1 | 7.4 | 3.7 |

| Program administration and net cost of insurance | 24.8 | 18.0 | 17.3 | — | 17.3 | .7 | 6.8 | 3.9 | 3.0 |

| Government public health activities | 14.6 | — | — | — | — | — | 14.6 | 1.6 | 13.0 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 19.1 | 7.7 | — | — | — | 7.7 | 11.4 | 8.6 | 2.8 |

| Research | 8.9 | .4 | — | — | — | .4 | 8.4 | 7.6 | .8 |

| Construction | 10.2 | 7.2 | — | — | — | 7.2 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| 1990 Total | $639.6 | $372.4 | $356.8 | $156.6 | $200.2 | $15.6 | $267.2 | $193.4 | $73.8 |

| Health services and supplies | 618.0 | 363.6 | 356.8 | 156.6 | 200.2 | 6.9 | 254.3 | 183.6 | 70.7 |

| Personal health care | 571.3 | 342.0 | 335.9 | 156.6 | 179.3 | 6.1 | 229.4 | 177.6 | 51.8 |

| Hospital care | 253.5 | 116.0 | 113.4 | 20.9 | 92.5 | 2.6 | 137.6 | 112.3 | 25.2 |

| Physicians'services | 131.8 | 92.5 | 92.4 | 34.7 | 57.7 | .1 | 39.3 | 32.7 | 6.6 |

| Dentists'services | 41.9 | 41.2 | 41.2 | 27.0 | 14.3 | — | .7 | .4 | .4 |

| Other professional services | 16.0 | 10.4 | 10.3 | 5.5 | 4.8 | .1 | 5.6 | 4.3 | 1.3 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 43.6 | 39.9 | 39.9 | 32.4 | 7.5 | — | 3.7 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 11.9 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 8.0 | 1.4 | — | 2.4 | 2.2 | .2 |

| Nursing home care | 56.3 | 29.6 | 29.2 | 28.1 | 1.1 | .4 | 26.6 | 14.8 | 11.8 |

| Other health services | 16.3 | 2.8 | — | — | — | 2.8 | 13.5 | 8.9 | 4.6 |

| Program administration and net cost of insurance | 29.2 | 21.6 | 20.8 | — | 20.8 | .8 | 7.6 | 4.3 | 3.2 |

| Government public health activities | 17.4 | — | — | — | — | — | 17.4 | 1.7 | 15.7 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 21.6 | 8.7 | — | — | — | 8.7 | 12.9 | 9.8 | 3.1 |

| Research2 | 10.1 | .5 | — | — | — | .5 | 9.7 | 8.7 | .9 |

| Construction | 11.5 | 8.2 | — | — | — | 8.2 | 3.2 | 1.0 | 2.2 |

Spending by philanthropic organizations, industrial in-plant health services, and privately financed construction.

Research and development expenditures of drug companies and other manufacturers and providers of medical equipment and supplies are excluded from “research expenditures,” but are included in the expenditure class in which the product falls.

Less than $50 million.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 10. Percent distribution of national health expenditures, by source of funds and type of expenditure: Selected years 1965-90.

| Type of expenditure and year | Total | Private | Public | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Total | Patient direct | Health insurance | Other | Total | Federal | State and local | ||

| Hospital care Historical | ||||||||

| 1965 | 100.0 | 60.1 | 16.8 | 41.1 | 2.2 | 39.9 | 17.4 | 22.5 |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 47.6 | 11.4 | 34.6 | 1.6 | 52.5 | 34.1 | 18.4 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 44.9 | 7.9 | 35.9 | 1.1 | 55.1 | 38.4 | 16.7 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 46.5 | 7.4 | 38.1 | 1.0 | 53.6 | 40.6 | 13.0 |

| 1982 | 100.0 | 47.2 | 7.6 | 38.5 | 1.0 | 52.8 | 41.1 | 11.7 |

| 1984 | 100.0 | 46.6 | 8.7 | 36.9 | 1.0 | 53.5 | 41.6 | 11.9 |

| Projected | ||||||||

| 1986 | 100.0 | 46.7 | 8.7 | 37.0 | 1.0 | 53.3 | 41.9 | 11.4 |

| 1988 | 100.0 | 45.9 | 8.2 | 36.7 | 1.0 | 54.1 | 43.3 | 10.8 |

| 1990 | 100.0 | 45.7 | 8.2 | 36.5 | 1.0 | 54.2 | 44.3 | 9.9 |

| Physicians' services Historical | ||||||||

| 1965 | 100.0 | 93.1 | 61.6 | 31.4 | .1 | 6.9 | 1.8 | 5.1 |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 79.1 | 45.4 | 33.6 | .1 | 20.9 | 14.9 | 6.0 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 73.7 | 34.1 | 39.5 | .1 | 26.4 | 18.8 | 7.6 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 73.1 | 30.5 | 42.5 | .1 | 26.9 | 20.6 | 6.3 |

| 1982 | 100.0 | 72.6 | 28.7 | 43.8 | .1 | 27.4 | 21.7 | 5.7 |

| 1984 | 100.0 | 72.2 | 27.8 | 44.4 | .1 | 27.7 | 22.4 | 5.3 |

| Projected | ||||||||

| 1986 | 100.0 | 71.2 | 27.0 | 44.2 | .1 | 28.7 | 23.6 | 5.1 |

| 1988 | 100.0 | 71.2 | 27.1 | 44.0 | .1 | 28.8 | 23.8 | 5.1 |

| 1990 | 100.0 | 70.2 | 26.4 | 43.8 | .1 | 29.8 | 24.8 | 5.0 |

| Dentists' services Historical | ||||||||

| 1965 | 100.0 | 98.3 | 97.1 | 1.2 | — | 1.7 | 1.1 | .6 |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 95.3 | 90.2 | 5.1 | — | 4.7 | 2.7 | 2.0 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 94.3 | 80.5 | 13.9 | — | 5.6 | 3.3 | 2.3 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 96.1 | 65.6 | 30.5 | — | 3.9 | 2.2 | 1.7 |

| 1982 | 100.0 | 97.1 | 63.5 | 33.6 | — | 2.9 | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| 1984 | 100.0 | 97.8 | 64.8 | 33.0 | — | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| Projected | ||||||||

| 1986 | 100.0 | 98.0 | 64.6 | 33.4 | — | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 1988 | 100.0 | 98.2 | 64.4 | 33.8 | — | 1.8 | .9 | .9 |

| 1990 | 100.0 | 98.3 | 64.3 | 34.0 | — | 1.7 | .9 | .8 |

| Drugs and medical sundries Historical | ||||||||

| 1965 | 100.0 | 96.2 | 93.6 | 2.6 | — | 3.8 | 2.3 | 1.5 |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 93.9 | 90.2 | 3.8 | — | 6.1 | 3.0 | 3.1 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 91.4 | 84.9 | 6.5 | — | 8.6 | 4.4 | 4.2 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 91.3 | 79.6 | 11.7 | — | 8.7 | 4.3 | 4.4 |

| 1982 | 100.0 | 91.1 | 77.6 | 13.5 | — | 8.9 | 4.4 | 4.5 |

| 1984 | 100.0 | 90.8 | 76.2 | 14.6 | — | 9.2 | 4.7 | 4.5 |

| Projected | ||||||||

| 1986 | 100.0 | 90.7 | 74.8 | 15.9 | — | 9.4 | 4.8 | 4.6 |

| 1988 | 100.0 | 91.2 | 74.5 | 16.7 | — | 8.8 | 4.5 | 4.3 |

| 1990 | 100.0 | 91.6 | 74.4 | 17.2 | — | 8.4 | 4.2 | 4.2 |

| Nursing home care Historical | ||||||||

| 1965 | 100.0 | 65.7 | 64.5 | .1 | 1.0 | 34.3 | 22.2 | 12.1 |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 51.4 | 50.3 | .4 | .7 | 48.6 | 28.6 | 20.0 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 44.0 | 42.7 | .7 | .6 | 56.0 | 31.4 | 24.6 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 45.1 | 43.6 | .9 | .6 | 54.9 | 29.6 | 25.3 |

| 1982 | 100.0 | 47.8 | 46.2 | .9 | .7 | 52.1 | 28.4 | 23.7 |

| 1984 | 100.0 | 51.0 | 49.4 | .8 | .7 | 49.0 | 27.3 | 21.7 |

| Projected | ||||||||

| 1986 | 100.0 | 52.2 | 50.2 | 1.2 | .7 | 47.9 | 26.7 | 21.2 |

| 1988 | 100.0 | 52.8 | 50.4 | 1.6 | .7 | 47.2 | 26.3 | 20.9 |

| 1990 | 100.0 | 52.7 | 49.9 | 2.0 | .7 | 47.4 | 26.4 | 21.0 |

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Hospital care

Hospital care accounts for more than 46 percent of personal health care spending and, thus, during the recent period of rapidly rising health care costs, has been the focus of much national attention. Both the public and private sectors have instituted extensive cost-containment programs. The public initiatives such as the Medicare prospective payment system (PPS), and an increased emphasis on peer review organizations are well known. The private sector has developed a variety of approaches to control costs, such as second opinions, increased deductibles and coinsurance, preferred provider organizations, health maintenance organizations (HMO's), coordination of benefits, and utilization review and audit of provider bills. An examination of recent hospital data reveals that the efforts of both sectors seem to have had the desired effect on costs.

Total hospital expenditures are projected to grow from their 1984 level of $158 billion to almost $254 billion in 1990 (Table 11). Hospital expenditures during the period 1984-90 are projected to grow at an 8.2 percent rate, compared with a 12.9 percent rate during the period 1978-84 (Table 12). The slowest growth, 7.0 percent, occurs during the period 1984-86, a time of significant declines in utilization.

Table 11. National health expenditures, by type of expenditure: Selected years 1950-90.

| Type of expenditure | 1950 | 1955 | 1960 | 1965 | 1970 | 1974 | 1975 | 1978 | 1980 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1986 | 1988 | 1990 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Amount in billions | |||||||||||||||

| Total | $12.7 | $17.7 | $26.9 | $41.9 | $75.0 | $116.1 | $132.7 | $189.7 | $247.5 | $321.2 | $355.1 | $387.4 | $454.2 | $539.9 | $639.6 |

| Health services and supplies | 11.7 | 16.9 | 25.2 | 38.4 | 69.6 | 108.6 | 124.3 | 179.9 | 235.6 | 307.0 | 339.8 | 371.6 | 437.2 | 520.8 | 618.0 |

| Personal health care | 10.9 | 15.7 | 23.7 | 35.9 | 65.4 | 101.3 | 117.1 | 167.4 | 219.1 | 284.9 | 315.2 | 341.8 | 402.9 | 481.3 | 571.3 |

| Hospital care | 3.9 | 5.9 | 9.1 | 14.0 | 28.0 | 45.0 | 52.4 | 76.2 | 101.3 | 134.7 | 148.8 | 157.9 | 180.8 | 213.7 | 253.5 |

| Physicians' services | 2.7 | 3.7 | 5.7 | 8.5 | 14.3 | 21.2 | 24.9 | 35.8 | 46.8 | 61.8 | 68.4 | 75.4 | 90.5 | 109.8 | 131.8 |

| Dentists' services | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 4.7 | 7.4 | 8.2 | 11.8 | 15.4 | 19.5 | 21.8 | 25.1 | 30.7 | 36.5 | 41.9 |

| Other professional services | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 5.6 | 7.1 | 8.0 | 8.8 | 10.9 | 13.3 | 16.0 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 1.7 | 2.4 | 3.7 | . 5.2 | 8.0 | 11.0 | 11.9 | 15.4 | 18.5 | 21.8 | 23.6 | 25.8 | 31.0 | 37.1 | 43.6 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 5.1 | 5.6 | 6.5 | 7.4 | 8.8 | 10.3 | 1.9 |

| Nursing home care | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 4.7 | 8.5 | 10.1 | 15.1 | 20.4 | 26.9 | 29.4 | 32.0 | 38.9 | 47.0 | 56.3 |

| Other health services | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 3.8 | 4.8 | 5.9 | 7.6 | 8.6 | 9.4 | 11.4 | 13.7 | 16.3 |

| Program administration and net cost of insurance | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 4.7 | 4.0 | 7.5 | 9.2 | 12.8 | 14.5 | 19.1 | 21.9 | 24.8 | 29.2 |

| Government public health activities | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 5.0 | 7.2 | 9.3 | 10.1 | 10.7 | 12.3 | 14.6 | 17.4 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 3.5 | 5.4 | 7.5 | 8.4 | 9.7 | 11.9 | 14.2 | 15.3 | 15.8 | 17.0 | 19.1 | 21.6 |

| Research | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 4.4 | 5.4 | 5.9 | 6.2 | 6.8 | 7.8 | 8.9 | 10.1 |

| Construction | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 5.3 | 6.5 | 8.3 | 9.1 | 9.0 | 9.2 | 10.2 | 11.5 |

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 12. National health expenditures average annual percent change, by type of expenditure: Selected periods 1950-90.

| Type of expenditure | 1950-55 | 1955-60 | 1960-65 | 1965-70 | 1970-75 | 1975-80 | 1980-85 | 1985-90 | 1965-84 | 1974-84 | 1978-84 | 1984-90 | 1984-86 | 1984-88 | 1986-88 | 1988-90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Average annual percent change | ||||||||||||||||

| Total | 7.0 | 8.7 | 9.2 | 12.3 | 12.1 | 13.3 | 11.0 | 8.9 | 12.4 | 12.8 | 12.6 | 8.7 | 8.3 | 8.7 | 9.0 | 8.8 |

| Health services and supplies | 7.6 | 8.3 | 8.7 | 12.6 | 12.3 | 13.7 | 11.3 | 9.0 | 12.7 | 13.1 | 12.9 | 8.8 | 8.5 | 8.8 | 9.1 | 8.9 |

| Personal health care | 7.6 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 12.8 | 12.4 | 13.3 | 11.0 | 9.1 | 12.6 | 12.9 | 12.6 | 8.9 | 8.6 | 8.9 | 9.3 | 9.0 |

| Hospital care | 8.9 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 14.9 | 13.4 | 14.1 | 10.6 | 8.6 | 13.6 | 13.4 | 12.9 | 8.2 | 7.0 | 7.9 | 8.7 | 8.9 |

| Physicians' services | 6.1 | 9.0 | 8.3 | 11.1 | 11.7 | 13.4 | 11.9 | 9.9 | 12.2 | 13.5 | 13.2 | 9.8 | 9.6 | 9.8 | 10.1 | 9.6 |

| Dentists' services | 9.4 | 5.6 | 7.3 | 11.1 | 11.6 | 13.3 | 12.5 | 8.5 | 12.2 | 13.0 | 13.4 | 9.0 | 10.6 | 9.9 | 9.1 | 7.2 |

| Other professional services | 7.3 | 8.9 | 3.7 | 9.1 | 10.4 | 16.5 | 11.7 | 10.4 | 11.9 | 14.7 | 13.4 | 10.6 | 11.5 | 11.1 | 10.7 | 9.7 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 6.7 | 8.9 | 7.2 | 9.1 | 8.3 | 9.2 | 8.8 | 9.0 | 8.8 | 8.9 | 9.0 | 9.1 | 9.6 | 9.4 | 9.3 | 8.4 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 4.2 | 5.1 | 8.6 | 10.7 | 10.1 | 10.2 | 9.5 | 8.0 | 10.2 | 10.3 | 10.2 | 8.1 | 8.5 | 8.4 | 8.3 | 7.5 |

| Nursing home care | 10.8 | 11.0 | 31.5 | 17.8 | 16.4 | 15.2 | 11.7 | 9.7 | 15.5 | 14.2 | 13.4 | 9.8 | 10.2 | 10.0 | 9.9 | 9.4 |

| Other health services | 11.9 | 3.7 | 0.7 | 12.5 | 12.8 | 9.5 | 11.9 | 9.4 | 11.7 | 11.8 | 12.1 | 9.5 | 9.9 | 9.8 | 9.8 | 8.9 |

| Program administration and net cost of insurance | 14.6 | 6.7 | 15.1 | 10.1 | 7.2 | 18.3 | 17.3 | 7.3 | 13.4 | 15.2 | 16.7 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 6.4 | 8.5 |

| Government public health activities | 0.9 | 1.9 | 14.5 | 11.8 | 17.3 | 19.6 | 9.6 | 8.8 | 14.5 | 14.6 | 13.5 | 8.5 | 7.6 | 8.2 | 8.8 | 9.2 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | -2.2 | 14.7 | 15.0 | 9.0 | 9.2 | 7.3 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 8.2 | 7.8 | 8.3 | 5.4 | 3.9 | 4.9 | 5.9 | 6.4 |

| Research | 12.4 | 25.8 | 18.0 | 5.4 | 11.1 | 10.2 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 8.2 | 9.3 | 7.4 | 6.9 | 7.1 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 6.9 |

| Construction | -5.0 | 10.0 | 13.8 | 11.4 | 8.1 | 5.1 | 6.7 | 5.1 | 8.2 | 6.7 | 9.0 | 4.2 | 1.4 | 3.3 | 5.3 | 6.0 |

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Community hospital inpatient

Expenditures for community hospital inpatient services are projected to increase from $114 billion in 1984 to more than $174 billion in 1990. This reflects an average annual rate of growth of 7.3 percent, down from the 14.4 percent growth rate during the period 1978-84. Community hospital costs per day and stay are projected to increase from 1984 levels of $443 and $2,947, respectively to $747 and $4,781 in 1990. These estimates also represent a decrease in the overall growth rate compared with the period 1978-84. To some extent, these declines are offset by increases in outpatient care and care in nonhospital settings. However, to a large degree, the hospital reductions seem to represent reductions in overall health care spending.

Preliminary data for 1985 suggest that hospital admissions will decline about 5.5 percent and total days by about 7.5 percent. The comparable decreases for 1984 were 3.7 and 8.7 percent for admissions and days, respectively. Because the number of days dropped faster than did admissions, the average length of stay declined. At some point, one would expect this drop in length of stay to stabilize or even reverse, because the patients admitted will be sicker, on average, than those admitted prior to cost-containment efforts (Barkholz, 1985).

The decline in admissions may be attributed to several factors. Cost-containment efforts such as second opinions and new nonsurgical treatment modalities are having an impact, but there are also reports of new consumer awareness and concern. Many consumers are demanding outpatient treatment when possible. To some extent, this phenomenon may be in response to employer incentives such as increased deductibles and coinsurance, but there also seems to be a new consumer inclination to question the health care they are receiving and a desire to try less invasive and less expensive alternatives before entering the hospital (Goldsmith, 1984).

Most industry analysts still express uncertainty as to how long the hospital inpatient declines will continue (Davis, Anderson, Renn, et al., 1985). Many predict that we are at or near the bottom of the declines, and that forces such as the aging of the population and limits as to how much more cost containment efforts can affect the system will cause a turnaround in the inpatient hospital utilization. The approach used in these projections follows this line of thinking. The estimates show a significant reduction in the rate of decline in utilization in 1986 and modest growth after 1988.

Community hospital outpatient

In contrast to the inpatient experience, outpatient care is growing strongly with average annual growth in expenditures from 1984 to 1990 projected to be twice as high as inpatient at 14.5 percent (Jensen and Miklovic, 1985). Growth in outpatient care makes sense in many respects. Some concern has been expressed that under Medicare's PPS, hospitals would admit patients, but shift as many services as possible to an outpatient setting, which is not covered by PPS, thus maximizing income from both settings. One of the factors that allows these shifts is that more technology has been adapted to the outpatient setting. Significant shifts to outpatient surgery have occurred, as well as the performance of many tests and medical workups formerly done on an inpatient basis (Anderson, 1985). In addition, many hospitals are expanding or reemphasizing their outpatient services by extensive marketing. These trends are consistent with government and business initiatives to have more services performed in a less costly setting.

As cost containment shortens stays and eliminates admissions, hospitals are seeking alternative sources of revenue and ways to employ their underutilized resources. Partial year data from the American Hospital Association Panel Survey, 1985 show outpatient visits to be growing at about a 3.7 percent rate in 1985, compared with a 1.6 percent average annual growth rate for the period 1978 to 1984. Many hospitals are aggressively marketing their outpatient services in forms to be competitive with HMO's, surgi-centers, emergi-centers, and the like.

Expenditures for outpatient care are predicted to be almost $46 billion by 1990, rising by an average annual growth rate of 14.5 percent from the 1984 level of more than $20 billion. Outpatient visits per capita for the same two periods grew at a 0.6 percent rate from 1978 to 1984, compared with a 2.0 percent rate from 1984 to 1990. Showing an opposite trend in growth rates, prices, after adjusting for overall inflation, dropped from 2.4 percent to 1.6 percent, and intensity per visit dropped from 5.2 percent to 4.7 percent. The net result is that even this strong growth is a decline from earlier periods such as 1978 to 1984 when expenditures grew at a 16.9 percent average annual rate.

Community hospitals maybe losing some business to nonhospital settings such as physicians' offices or surgi-centers and emergi-centers. In an attempt to offset these losses, one of the more recent initiatives in the hospital sector is the alliance between hospitals and insurers. In some cases, hospital chains are purchasing insurance companies, but in most cases major insurers and large hospital groups are uniting to create new kinds of competitive insurance packages. One example mentioned earlier is the MPPPO venture formed by the Voluntary Hospitals of America and Aetna Insurance Company. These alliances of providers and payers are attempts to lock in a set of clients to guarantee both partners a share of the market. Along these same lines, hospitals are also acquiring and setting up their own HMO's. Again, the attempt is to compete and maintain or increase a share of the market.

Federal hospitals

Federal hospitals spending is projected to experience slower growth than it has in the past, with expenditures rising from a 1984 level of less than $11 billion to more than $18 billion in 1990, a 7.9 percent rate of average annual increase. The rate of growth from 1978 to 1984 was 9.4 percent. The slow-down is attributed to Federal budget constraints, lower inflation rates, and Federal hospital closures. Federal hospitals are somewhat isolated from the forces affecting community hospitals because most are paid by appropriation rather than by reimbursement on a patient basis. Thus, they have not experienced as much of a slowing in growth as the community hospitals.

Other hospitals

The almost 800 non-Federal psychiatric, tuberculosis and other respiratory disease, chronic disease, and alcoholism and chemical-dependency hospitals that make up “other hospitals” are projected to grow at a 4.4 percent average annual rate from 1984 to 1990. Expenditures at these hospitals are estimated to be $12 billion in 1984 and to grow to more than $15 billion in 1990. Growth in the projected period is down slightly from the 1978 to 1984 growth of 5.3 percent, a difference accounted for by the estimate of lower inflation upon which these forecasts are predicated.

Physicians' services

Physicians have traditionally exerted far more influence on the health care sector than their 22-percent share of personal health care indicates. This is attributable to the fact that they are the primary decisionmakers in what kinds of health care patients receive, such as hospital care or drugs. However, although physicians' share of health care expenditures is growing, their role in decisionmaking may be lessening. The impact cost-containment policies such as second opinions means that often a single physician cannot decide a patient's course of treatment. But, the roots of the declines in physician influence go much deeper than the effects of second-opinion programs. Hospitals have been put under pressure by private and public cost-containment efforts. Previously, in an effort to attract and hold physicians, hospitals were almost forced to acquire the newest and best of technologies and supplies. Now, they must face tighter budget constraints. An example of these constraints is the fixed-price prospective payment system under Medicare. Perhaps even more effective are private sector programs such as hospital bill audits, more cost sharing between the insurer and the insured, coordination of benefits, preferred provider organizations, and increased competition from HMO's. These programs put downward pressure on hospital revenue sources by reducing double or overpayments, discouraging hospital use, or conversely, by encouraging use in nonhospital settings, or requiring discounted prices.

Physicians now know that their practice privileges in an institution could be jeopardized if they are not cost efficient. Computer audits of patient stays, based on diagnosis, enable hospitals to identify physicians who tend to overutilize services. As hospital resources decrease, there will be increased competition among physicans for access to those resources. The result is that hospital administrators will play a much larger role in hospital management and, hence, physicians a lesser role (American Medical Association, 1985).

Expenditures for physicians' services are projected to grow at an annual average rate of 9.8 percent from the 1984 level of more than $75 billion, reaching almost $132 billion by 1990. The growth rate from 1978 to 1984 was 13.2 percent. The slower projected growth rate is a result of many factors, including lower average inflation during the projection period than from 1978 to 1984. Competition from hospital outpatient departments may also limit the growth in expenditures for physicians' services. How the decline in inpatient hospital use will affect physicians is still to be seen. To the extent that physicians' services are complementary to hospital care, one would expect physicians' services to be restrained; to the extent that physicians' services can substitute for inpatient care, a physician's role in health care delivery may grow. In the projection presented here, the physician portion of personal health services is projected to increase slightly from a 1984 share of 22.1 percent to a 1990 level of 23.2 percent. Per capita expenditures for physician care are projected to increase from $307 in 1984 to $510 in 1990. The average annual growth rate for the period 1984 to 1990 is 8.8 percent, down from 12.1 percent for the period 1978-84.

Dentists' services

After years of reasonably strong growth, dental expenditures are projected to moderate somewhat, remaining at an essentially constant percent of total personal health care. Amalgam sales, after adjusting for the price of silver, are down in the current period. This suggests a decline in restorative work because of the combined effects of improved dental hygiene, fluoridation, and a slackening in the growth in insurance coverage for dental care (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1985). With regard to the latter, many employees gave up dental and vision benefits during the recession period in exchange for wages. This phenomenon was particularly true in the heavy industries, where emphasis has shifted from maintaining fringe benefits to keeping jobs. In addition, many dental plans have added or increased deductibles and coinsurance.

Dental expenditures are estimated to be $25 billion in 1984 and are projected to be $42 billion by 1990. The annual average growth rate in dental expenditures for the period 1984 to 1990 is projected to be 9.0 percent, compared with the 13.4 percent rate from 1978 to 1984. The lower rate is reflected in all five projection factors, but moderation of economy-wide inflation has the most impact on the slowing of the rate of increase in dental expenditures.

Other professional services

Other professional services include the services of freestanding home health agencies (HHA's), optometrists, podiatrists, chiropractors, private duty nurses, occupational, speech, and physical therapists, clinical psychologists, and others who are engaged in independent practice. In 1990, a projected $16 billion will be expended on the services of these other professionals, almost double the 1984 level of less than $9 billion. These services are projected to experience a faster rate of growth than most other personal health services, although the growth from 1984 to 1990 is 10.6 percent compared with a growth of 13.4 percent from 1978 to 1984 because of lower projected overall price levels. As this category includes nonhospital-based home health agencies, one might expect increasing rates of growth in the projected period as is also projected for other substitutes for hospital inpatient care. However, a significant portion of home health agency growth is hospital based and is included in expenditures for hospital care.

Drugs and medical sundries

Drugs and medical sundries dispensed through retail channels are projected to grow from 1984 level of less than $26 billion dollars to a 1990 level of almost $44 billion. Drug prices are projected to grow slightly faster than economy-wide prices. This forecast is consistent with reports that new and expensive drugs are being developed, including biogenetically created drugs (Business Week, 1985).

Eyeglasses and appliances

After a surge of purchases following the recent recession, expenditures for eyeglasses and appliances are projected to grow at an average annual rate of 8.1 percent from 1984 to 1990. The 1984 expenditure level for this category (more formally and perhaps descriptively named ophthalmic products, orthopedic appliances, and durable medical equipment) is more than $7 billion. The projected 1990 level is $12 billion. Although ophthalmic products comprise the majority of these expenditures, durable medical equipment is an area where more future growth may occur. The rationale for this speculation is based on the notion that earlier discharges from or nonadmission into hospitals may cause significant increases in the amount of self or family health care. This will result in the purchase of more durable medical equipment and supplies.

Nursing home care

Nursing homes, including intermediate care facilities for the mentally retarded is the third largest component of personal health care (after hospitals and physicians). Nursing home care, along with physician expenditures, are the only significant categories of personal health care expected to increase as a share of the total (Table 6). Nursing home care expenditures are projected to be more than $56 billion in 1990, growing at an average annual rate of 9.8 percent from the 1984 level of $32 billion. The average annual growth rate from 1978 to 1984 is 13.4 percent. The nursing home growth, which is strong in relation to the growth rate projected for most other components of personal health care, is supported by demographic shifts towards the elderly and especially the extremely elderly. Also, as with home health care, some expenditures for nursing home care will be precipitated by the shorter hospital stays expected under continued cost-containment efforts.

Other personal health care

The other health services category consists primarily of care provided in Federal units other than hospitals, school health services, and industrial in-plant services. This category is projected to account for more than $16 billion in expenditures in 1990, compared with a 1984 level of more than $9 billion, an average annual growth rate of 9.5 percent per annum.

Program administration and net cost of health insurance

Expenses for program administration and net cost of health insurance include the administrative costs of public programs and private voluntary health organizations for lobbying, fundraising, and similar activities. It also includes the difference between private health insurance benefits and premiums, that is, the net cost of purchasing health insurance. The total for this category will rise from $19 billion dollars in 1984 to a projected level of more than $29 billion in 1990. Insurance comprised 70.2 percent of the 1984 total for program administration and net cost of insurance and is projected to be 71.4 percent in 1990. Nevertheless, growth in this category and especially in insurance has slowed considerably because of competition in the insurance industry and increased awareness on the part of employee benefit specialists. This trend should continue as employers become purchasers of health care instead of payers and as the options available to them, such as PPO's and HMO's, continue to expand.

Government public health activities

The current budgetary constraints and concerns are having a considerable impact on expenditures for public health. State and local expenditures account for almost 90 percent of these activities. Their expenditures will grow at an average annual rate of 9.1 percent from 1984 to 1990, at less than one-half the 18.7 percent growth rate from 1974 to 1984. The 1990 level for public health is projected to be more than $17 billion, which is still a considerable increase over the almost $11 billion level in 1984.

Research

Research is another area affected by budget considerations, although it may not be to the same extent as public health. One factor supporting increases in research is public concern over a variety of diseases, such as cancer and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Federal research comprises about 85 percent of the total and has, on average, grown at a constant 7.5-percent rate. Overall research expenditures are projected to grow from a 1984 level of a little less than $7 billion to a 1990 level of $10 billion, a 6.9 percent average annual rate of growth.

Construction of medical facilities

As might be expected from the declines in utilization, budget constraints, and general uncertainty, growth in construction has slowed to a pace consistent with replacement needs. These declines reflect reductions in hospital building. Construction of nursing homes and other less expensive facilities are continuing to grow (Punch, 1985). The rate of private construction, which represents 70 percent of the total, declines from an 11.8 percent growth from 1978 to 1984 to a projected 4.4 percent growth from 1984 to 1990. The change for construction for the last historical year was − 1.9 percent. The projections in the out-years represent an assumption of a return to more normal growth patterns.

Demographics of health expenditures

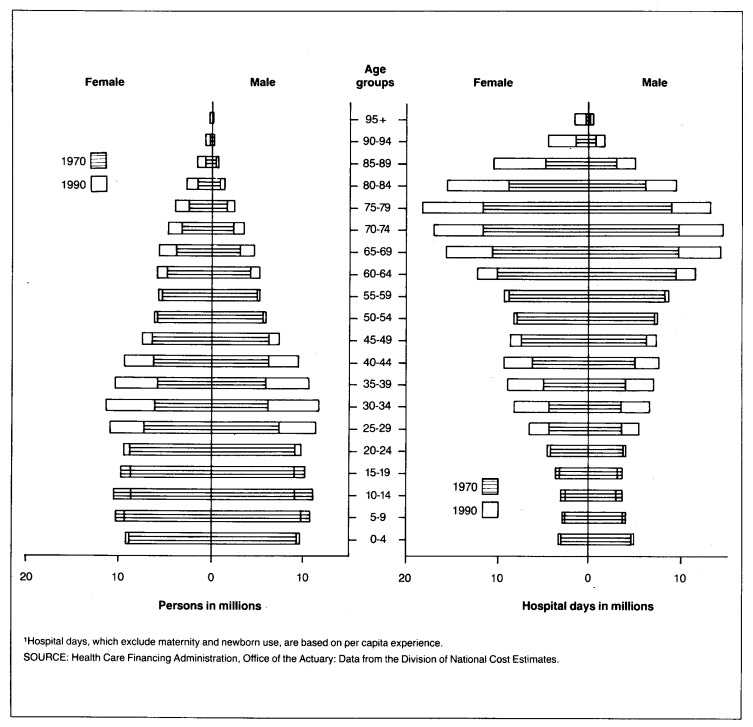

In the past, the projections have implicitly recognized the effects of population aging in the selection of forecast assumptions, considering the work of several researchers. Analyses are now being prepared to explicitly recognize the effects of changes in age structure on average use and average price per service. Some preliminary results of these studies are summarized here. The U.S. population in 1970 and 1990 and the corresponding number of hospital days of care are charted in the typical format of a population pyramid (Figure 1). The hospital days, which exclude maternity and newborn utilization, are based on the per capita experience reported in the National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS) of 1981. The shape of the population pyramid is determined largely by the fertility history of the United States and the mortality patterns by age and sex. Of particular importance to this analysis are the indentations corresponding to the low birth rates of the 1930's depression, the bulge of the post-World War II baby boom, followed by the baby bust of the 1970's. These demographic features will influence demand for medical services into the next century.

Figure 1. Population and days of hospital care, by age and sex: 1970 and 1990.

The area under the population pyramid represents total population, and the area under the hospital utilization pyramid represents total hospital days of care used per year. Although the areas are roughly equal, the distribution by age is almost exactly reversed. As the proportion of the population in the older age groups increase from 1970 to 1990, the effects on utilization are magnified by the sharply higher use of services among the aged. This is the phenomenon of the effect of aging on the demand for medical care. The effects of aging depend on the relative use of services by age. Because hospital use generally increases with age, population aging tends to drive up hospital use faster than the growth in population. For services where use declines with age, such as dentistry, use will tend to increase more slowly than population growth.

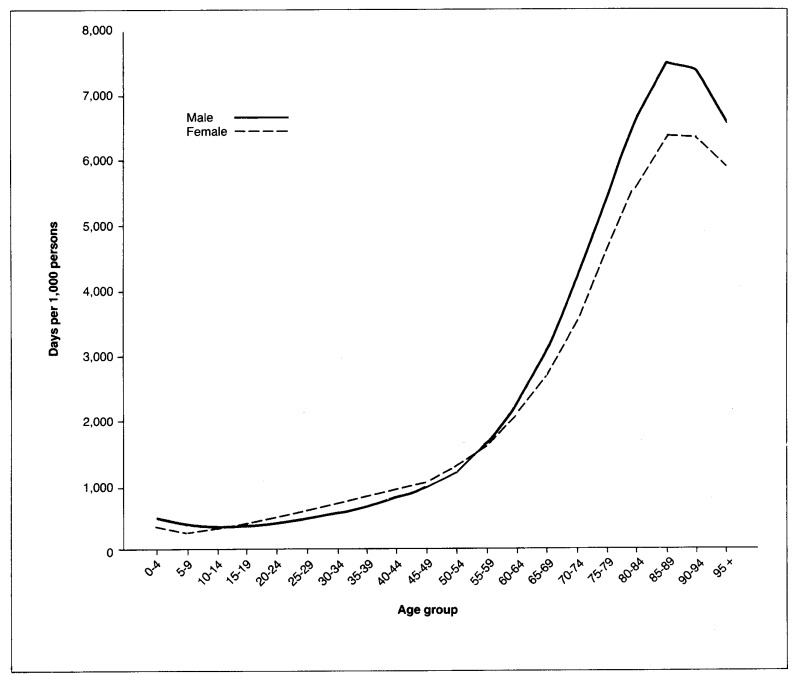

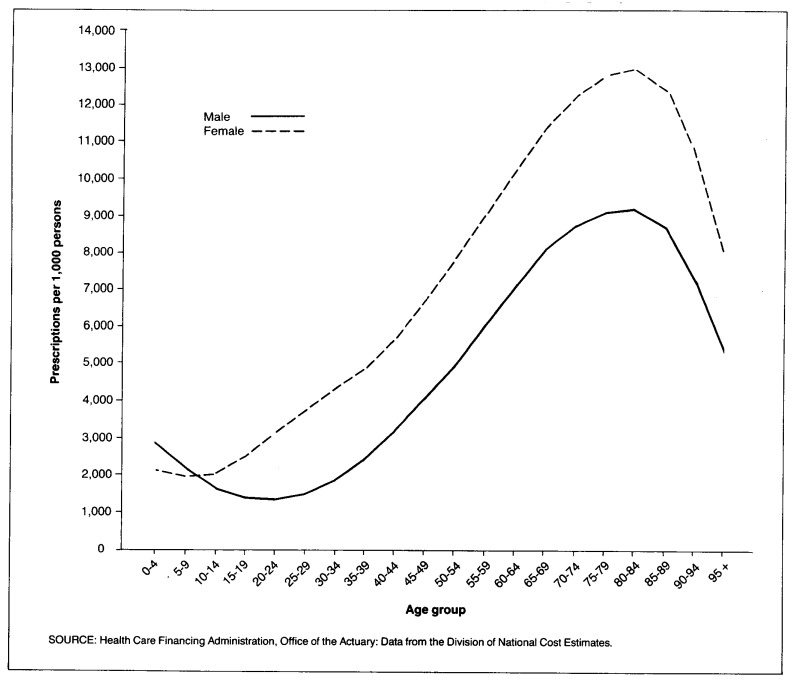

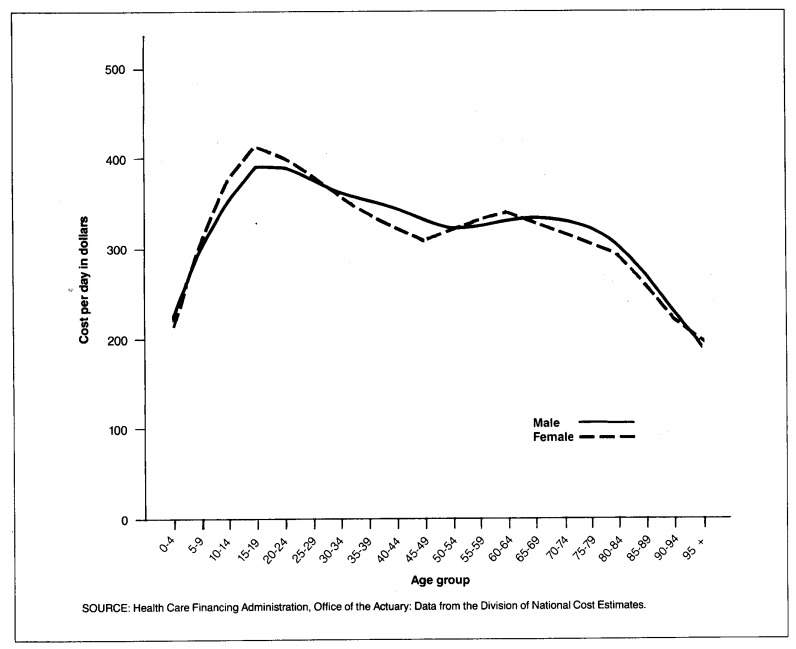

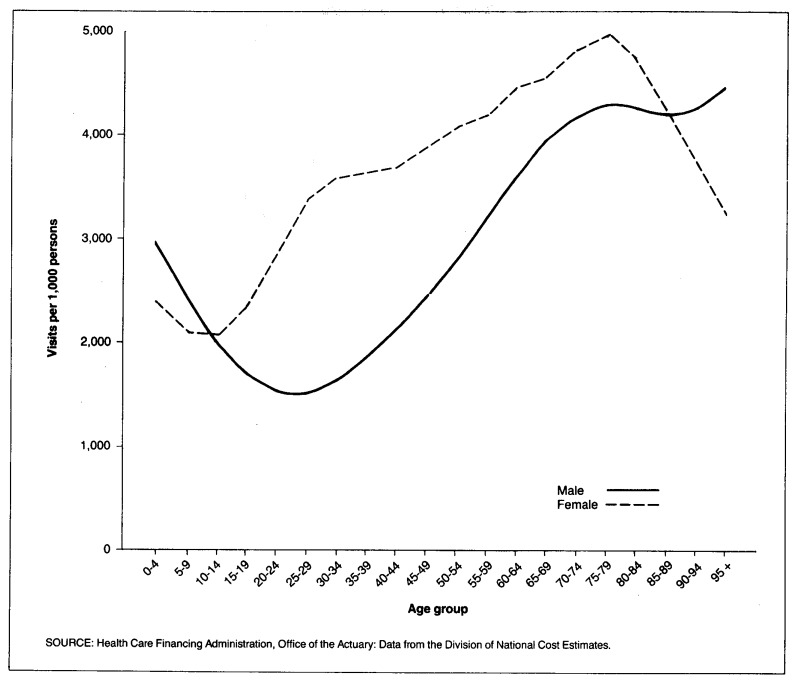

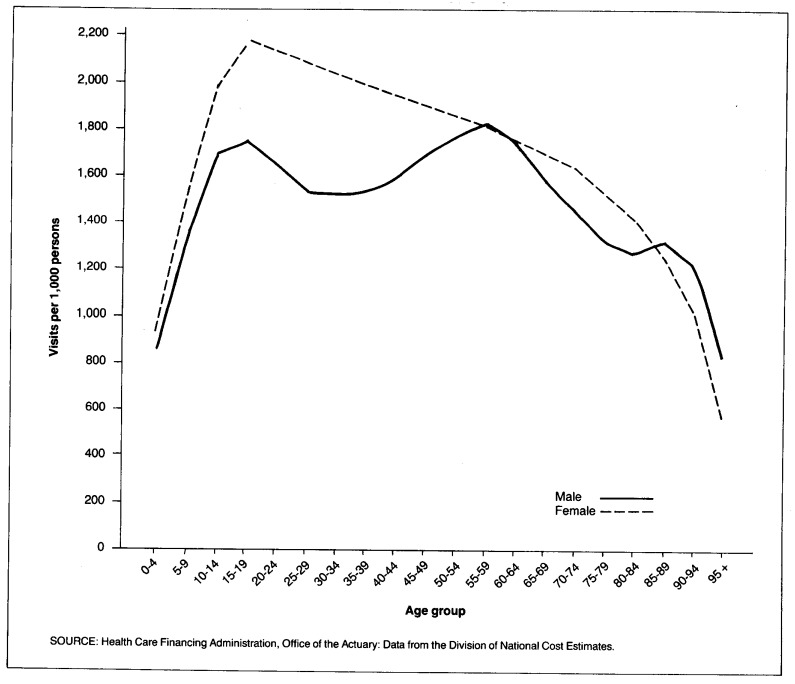

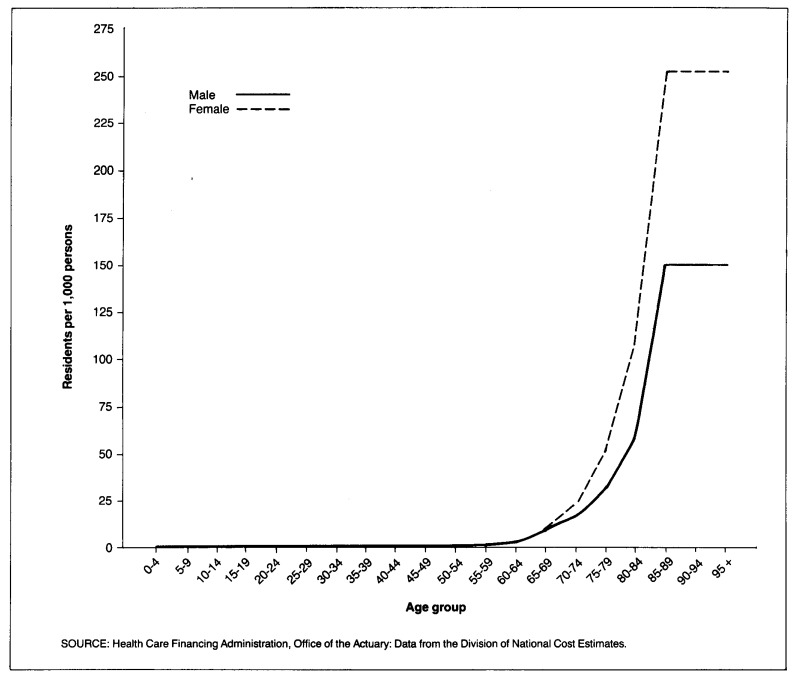

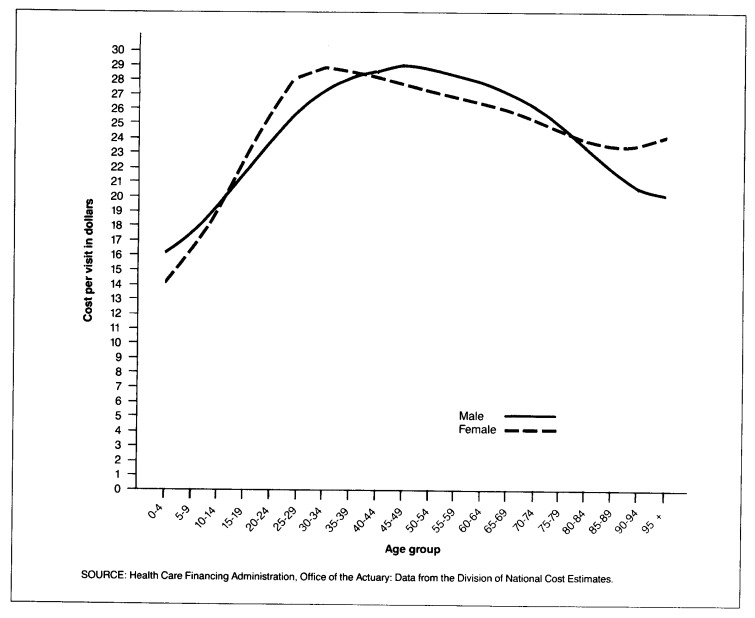

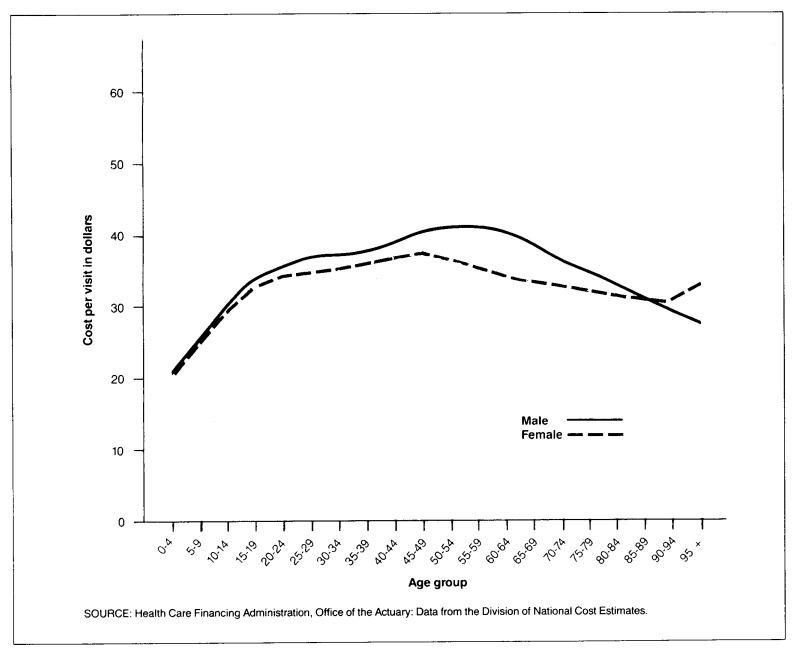

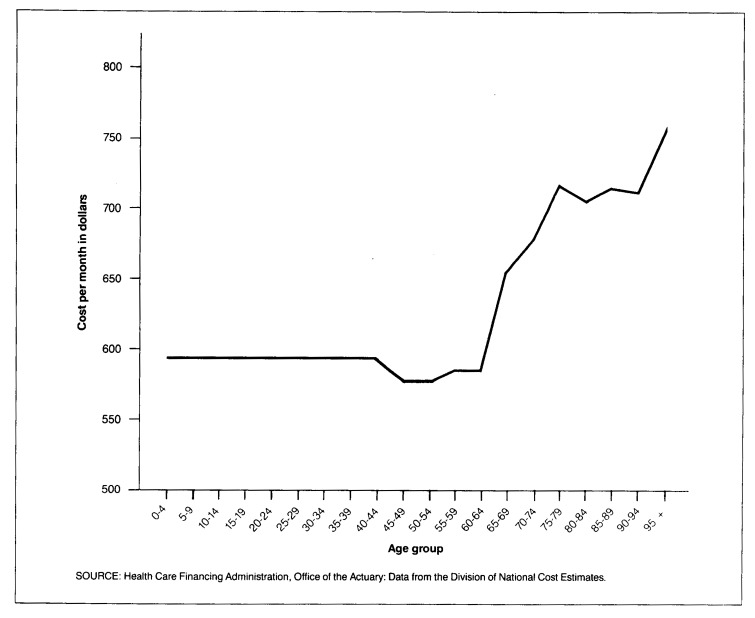

Actual utilization patterns by age and sex are shown for five commonly used services (Figure 2 through 6). Hospital utilization is from the NHDS of 1981 referred to earlier. Physician office visits and prescribed drug utilization for the noninstitutionalized are from the National Medical Care Expenditure Survey (NMCES) of 1977. Dental visits are from the Health Interview Survey of 1981. Nursing home residency rates were taken from the 1980 census. All rates except nursing homes have been smoothed by using the Whittaker-Henderson graduation technique.

Figure 2. Hospital days1 per 1,000 persons, by age group and sex: 1981.

1Hospital days exclude maternity and newborn use.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Figure 6. Number of prescriptions per 1,000 noninstitutionalized persons, by age group and sex: 1977.

Except for the dental services, use rates generally increase with age, except perhaps at the very oldest ages. Although the sample sizes are usually small at extreme old ages, it appears that use of most services (except nursing homes) plateaus or even decreases after about age 85. Medicare data also suggest a similar pattern. It has been observed that mortality rates also tend to stabilize at very old ages, perhaps because survival to these ages produces a super select population. Utilization is also very different by sex. The higher use of nursing homes by older females is probably not because of higher morbidity (their hospital use is lower than that of males) but to the fact that females are more likely than males to be alone at old ages because of their lower mortality rates.

Prices per unit of service also vary by age and sex (Figures 7 through 11). Hospital costs are from the National Medical Care Utilization and Expenditure Survey (NMCUES) of 1980. Nursing home charges are from the 1977 National Nursing Home Survey. Prices for the other services are from NMCES (1977). Most prices per measured unit increase with age augmenting the impact of aging on utilization. Hospital costs per day, however, decrease with age because the longer stays of the aged spread out costs. This somewhat offsets the effects of aging.

Figure 7. Hospital cost per day, by age group and sex: 1980.

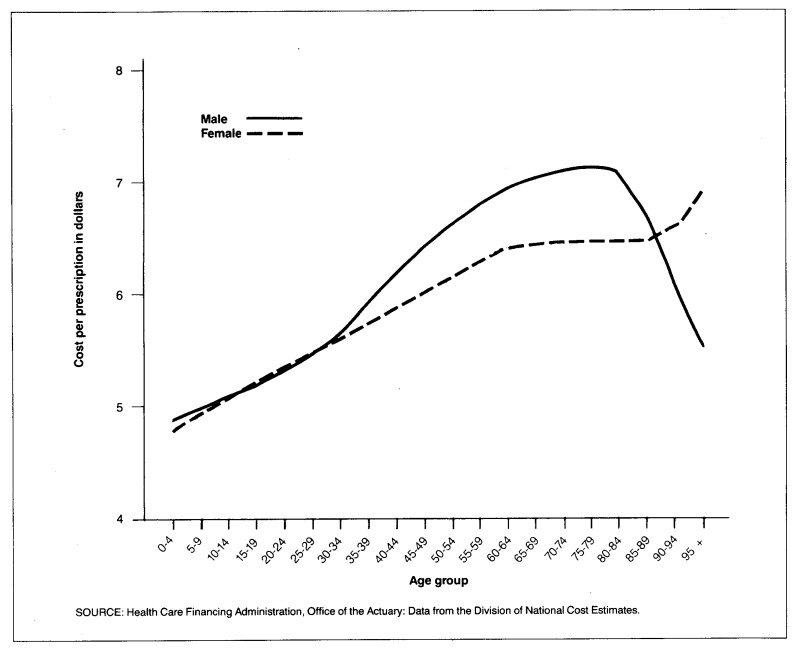

Figure 11. Cost per prescription, by age group and sex: 1977.

The effects of changes in population composition on aggregate utilization rates were calculated by multiplying a fixed set of age-sex specific utilization rates by population in each group for each year from 1965 to 1990. The population data and projections were provided by the Office of the Actuary of the Social Security Administration (Wade, 1985). The methodology is essentially the same as used by several other researchers (Russell, 1981). The average aggregate use per capita was then computed for each year. The result shows changes generated solely by population mix, exclusive of population growth (Table 13).

Table 13. National health expenditures average annual change per capita, by type of service and demographic factors: Selected periods 1965-90.

| Type of service and period | Actual change | Demographically induced change | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Utilization change | Price change | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Total | Male | Female | Under age 65 | Age 65 or over | |||

| Hospital days (excluding maternity) | |||||||

| 1965-70 | 1.9 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.5 | .01 |

| 1970-75 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | -.06 |

| 1975-80 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.1 | -.10 |

| 1980-85 | -4.6 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | -.15 |

| 1985-90 | -1.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.3 | -.14 |

| Physician office visits | |||||||

| 1965-70 | 0.4 | 0.0 | -0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.14 |

| 1970-75 | 2.7 | 0.1 | -0.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.19 |

| 1975-80 | -1.2 | 0.2 | -0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.17 |

| 1980-85 | -1.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.09 |

| 1985-90 | -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.08 |

| Nursing home days | |||||||

| 1965-70 | 9.3 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 2.8 | 0.5 | 1.9 | — |

| 1970-75 | 4.9 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 0.4 | 0.9 | — |

| 1975-80 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 0.3 | 0.7 | — |

| 1980-85 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | — |

| 1985-90 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 2.2 | -0.1 | 0.9 | — |

| Prescriptions | |||||||

| 1965-70 | — | 0.2 | -0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.05 |

| 1970-75 | — | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.06 |

| 1975-80 | — | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.05 |

| 1980-85 | — | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.03 |

| 1985-90 | — | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.05 |

| Dentists | |||||||

| 1965-70 | -0.8 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | -0.1 | 0.10 |

| 1970-75 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.13 |

| 1975-80 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 0.11 |

| 1980-85 | 0.9 | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 | 0.05 |

| 1985-90 | 0.2 | -0.1 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 0.0 | -0.1 | 0.05 |