Abstract

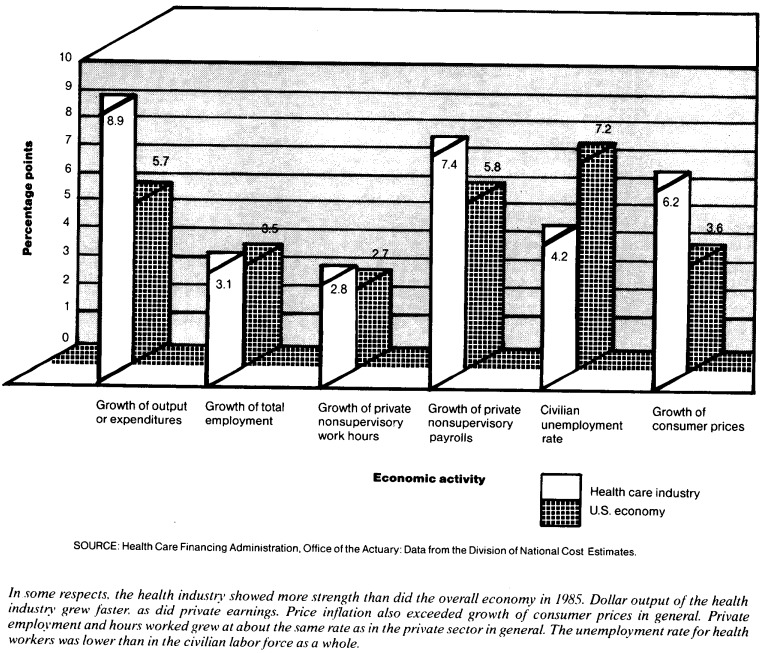

Slower price inflation in 1985 translated into slower growth of national health expenditures, but underlying growth in the use of goods and services continued along historic trends. Coupled with somewhat sluggish growth of the gross national product, this adherence to trends pushed the share of our Nation's output accounted for by health spending to 10.7 percent. Some aspects of health spending changed: Falling use of hospital services was offset by rising hospital profits and increased use of other health care services. Other aspects remained the same: Both the public sector and the private sector continued efforts to contain costs, efforts that have affected and will continue to affect not only the providers of care but the users of care as well.

Overview

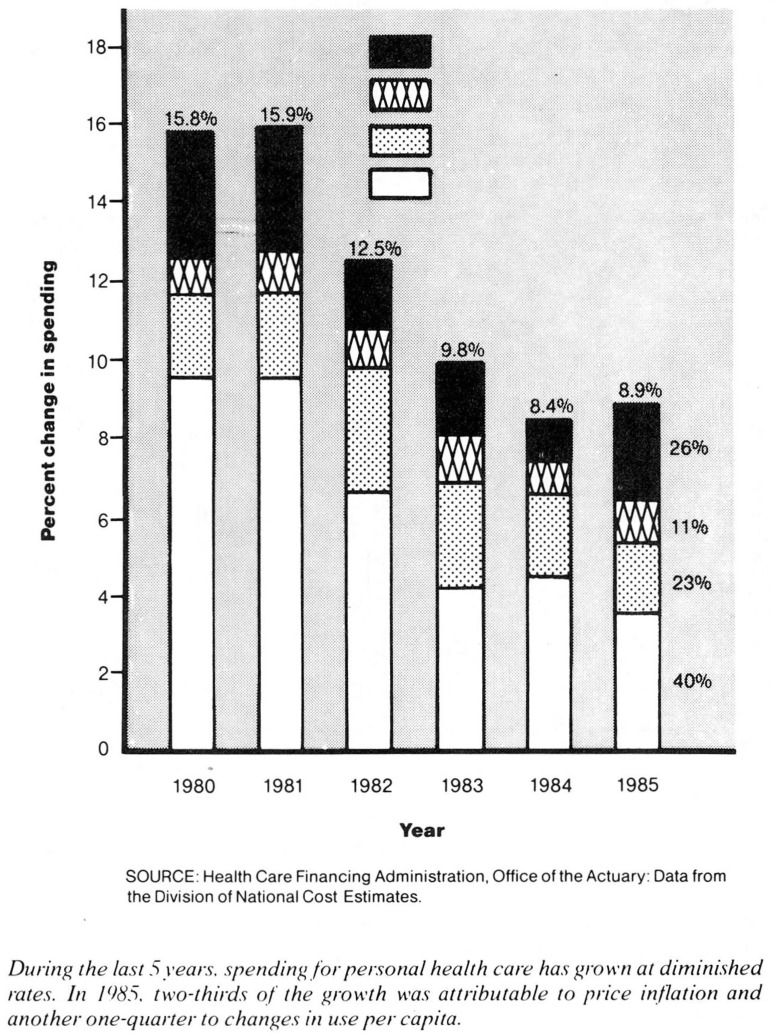

Health spending in the United States reached $425 billion in 1985, up 8.9 percent from the previous year. This growth was the slowest in two decades, but the slowdown was attributable almost entirely to lower growth of prices.

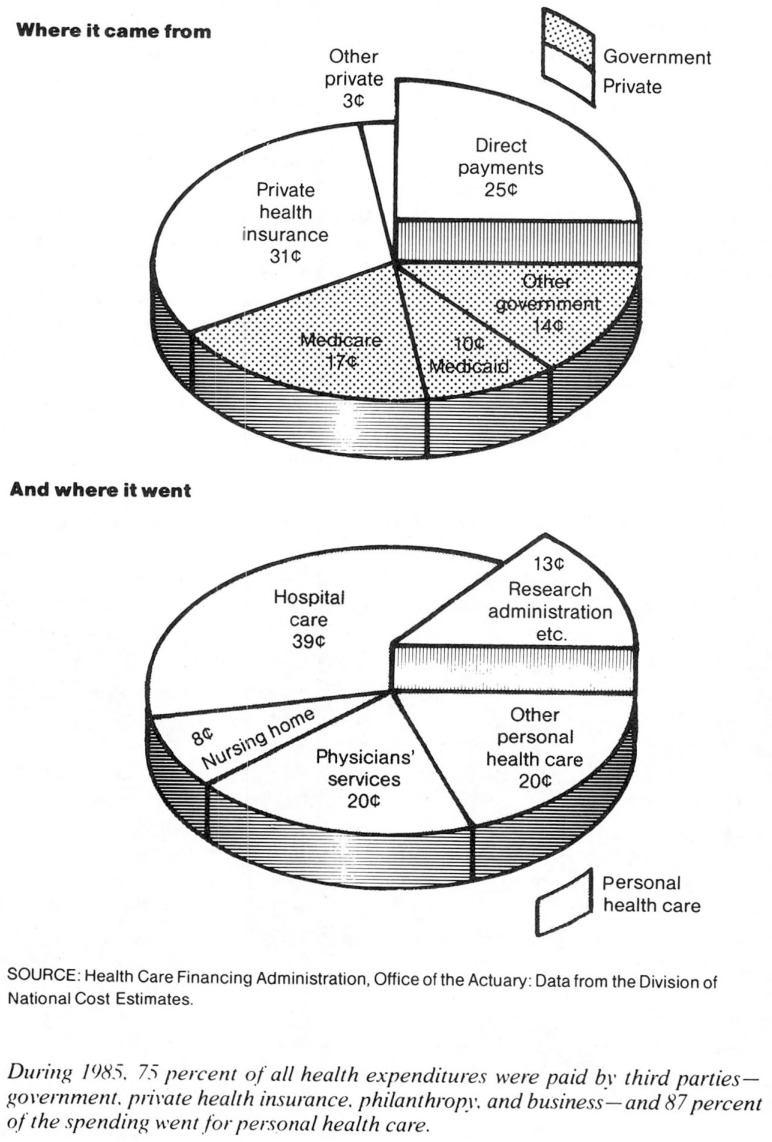

National health expenditures amounted to $1,721 per person in 1985. That figure does not represent the expenditure of a “typical” person, but rather a commitment of resources on a national level. Of the funding for health expenditures, 59 percent came directly from the private sector, mostly through private health insurance and from consumers and their families. The remaining 41 percent was funded through government programs, principally the Medicare and Medicaid programs.

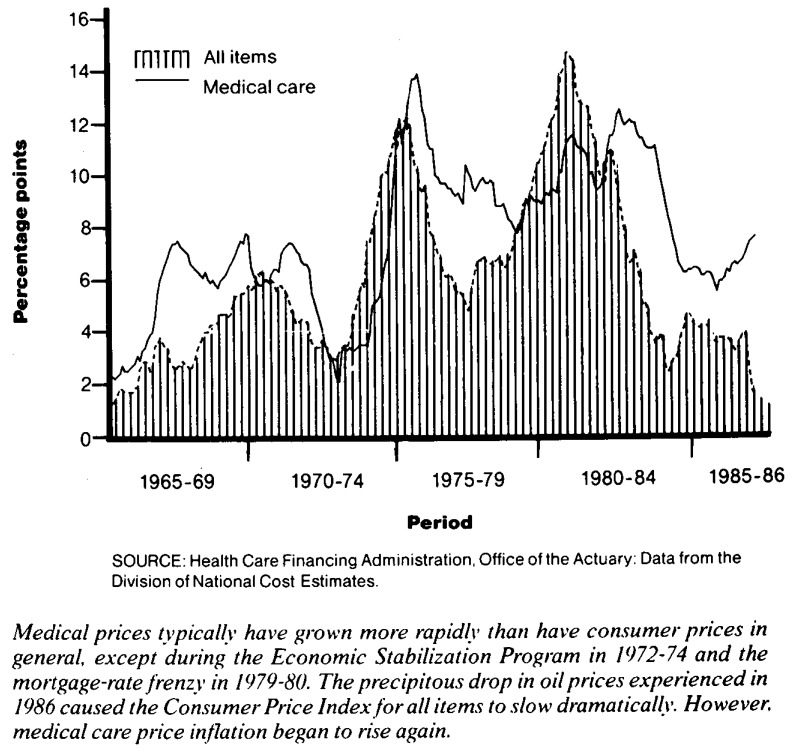

Slower price inflation was the cause of slower growth in health spending. The medical care component of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) was 6.2 percent higher in 1985 than it had been in 1984. It maintained the same rate of growth as from 1983 to 1984. Equally encouraging, at least to purchasers of health care, was a marked trend toward price competition in the health care market. The rapid spread of competition among providers of care for “market share” may have served to moderate the rise of health care prices even beyond the extent indicated by the “list” prices measured in the CPI.

Although a slowdown in the growth of prices was welcome news to consumers and insurers alike, there were at least two troubling signs to be seen. First, despite that slowdown, medical prices still outpaced prices of other goods and services. To a great extent, this type of price behavior is expected. Health care is largely a service, and in a mature economy, service prices tend to rise more rapidly than do commodity prices. However, the inevitability of an economic phenomenon does little to ease the burden it imposes. The burden that relatively high medical care price inflation imposes is that, unless the combined growth of relative prices and of the quantity of goods and services consumed per capita is less than the growth of real income per capita (currently about 2 or 3 percent per year), a larger and larger share of income will be consumed for health care. This clearly has been the case in the United States, as health spending reached 10.7 percent of the gross national product (GNP), a measure of our Nation's income. Little relief appears to be in sight.

The second troubling observation about medical care price inflation is that it seems to be heating up again. Starting in mid-1985, monthly CPI figures began to show more and more growth, suggesting that the deceleration of price inflation experienced in 1985 will not be repeated in 1986.

The amount spent for health in 1985 increased over 1984 levels even after adjustment for the effects of price growth. This can be seen in either of two ways. First, growth of “real” spending for personal health care—expenditure change excluding the effects of health care price inflation—was very much along historical trends. Second, the “opportunity cost” of health care spending—spending deflated by the general price level to measure the amount of other goods and services U.S. consumers had to forgo in order to purchase health care—increased 5.4 percent in 1985. Both measures point to an increase in the share of our Nation's physical consumption devoted to health.

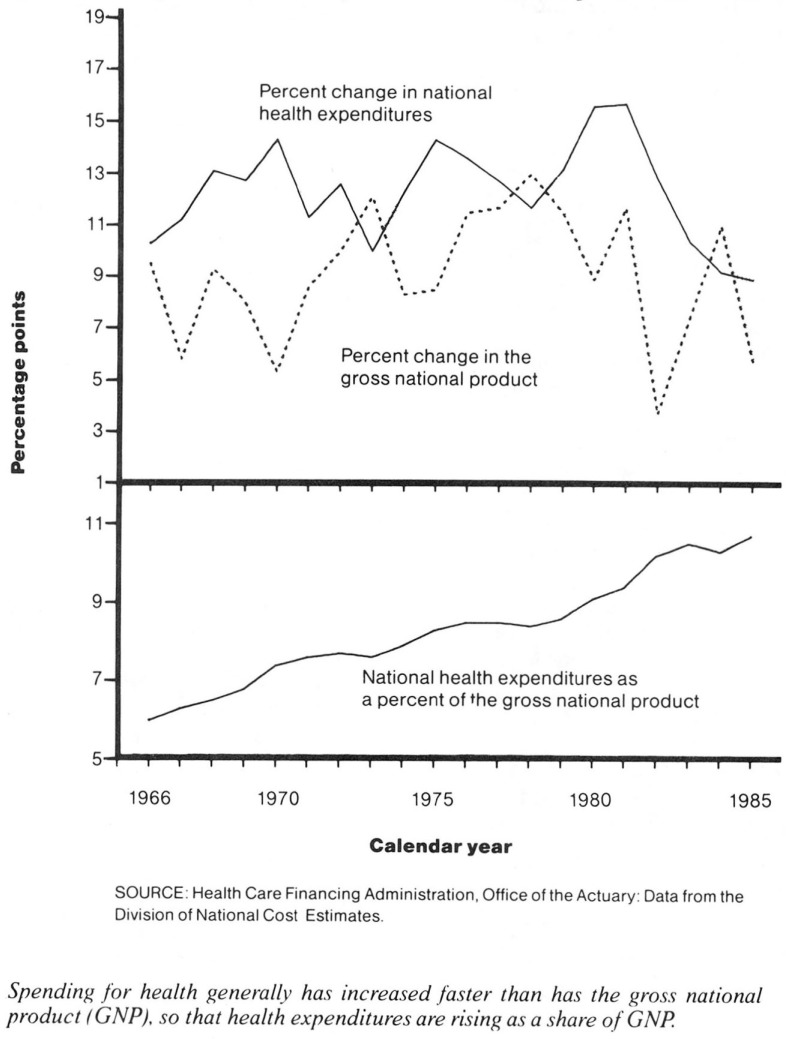

Spending for health has been cutting more and more deeply into the Nation's pocketbook. From about 6 percent of GNP in 1965, national health expenditures grew to equal 10.7 percent of GNP in 1985, nearly doubling the claim on resources in two decades. The relatively rapid change from 1984 to 1985 in the share of GNP going to health can be attributed to two phenomena. In 1984, GNP grew very strongly after a 2-year recession but health spending, and hospital spending in particular, decelerated as providers and consumers accustomed themselves to changes in the financing of such care. In addition, GNP growth in 1985 was one-half of the 1984 growth. Prices and real growth decelerated, but health care price inflation did not decelerate nearly as much, and real growth increased a little. The decline in the share of GNP going to health in 1984 appears to be a one-time blip in the historic trend rather than the start of a new trend.

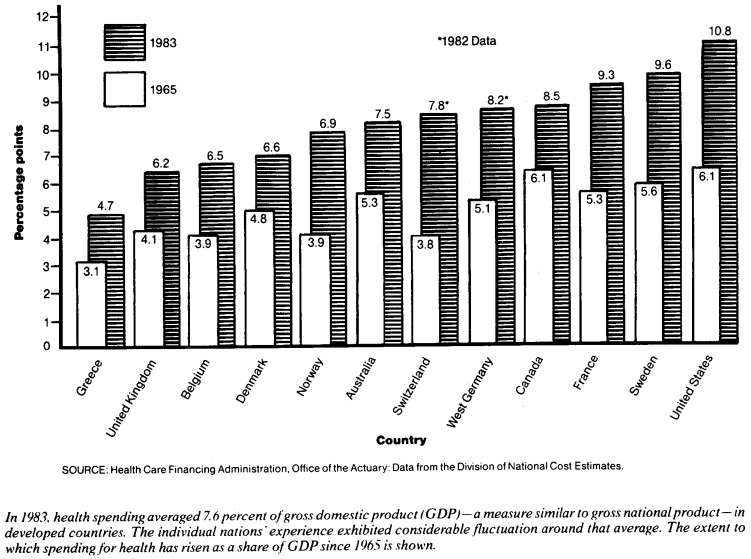

It is perhaps some consolation that the United States is not alone in its struggle to determine the proper level and mix of health care consumption. Most other industrial countries in the world are facing the same issue, adopting different approaches in attempting to find a solution. From Great Britain's nationalized health industry, through the reliance of France and West Germany on the social security system, to U.S. dependence on the private sector, a variety of health delivery and financing models have been developed. Whether they will accomplish the same goal—optimal access to efficiently produced care—is yet to be seen.

That real growth of health spending has followed a fairly even path does not alter the fact that the health care industry has undergone change in the recent past. Although minor in comparison with the structural upheaval of other industries in the United States, such as that faced by the steel and air travel industries, the changes seen in the health industry are remarkable in light of the strong traditional attitudes of health care providers and consumers. Driven by cost considerations, insurers and other third parties have banished, perhaps forever, an unflinching reliance on providers of care to determine not only the correct treatment but the correct cost of that treatment as well. The new “wave” of health care can be seen through changes in the delivery of care (notably, the deemphasis of hospital care) and in the financing of care (a heightened concern with the “bottom line”).

Changes in delivery of care

Following years of unrelenting increases in hospital use, the financial pinch felt by employers and government health program managers early in the 1980's resulted in sharp reversals of historic trends. Growth of expenditures for hospital services, which comprise almost one-half of all spending for personal health care and which had been growing more rapidly than other forms of health spending, slowed dramatically. Preadmission testing in outpatient departments and physicians' offices replaced early admission to the hospital, and the length of hospital stays was reduced. Procedures that had been performed on an inpatient basis were moved to outpatient and office settings. In some cases, financial pressures to move to lower cost settings were coupled with the diffusion of affordable technology that permitted such moves.

Gross national product revisions.

In December 1985, the U.S. Department of Commerce announced the results of their periodic revision of the gross national product (GNP) estimates. The new estimates are substantially higher than previous figures because of three types of changes: definitional changes (none related to health), new methods of adjusting tax return information, and the inclusion of new or revised data. For example, of the $111 billion upward revision to GNP for 1984, $30 billion are attributable to changes in definitions, $44 billion to adjusted tax information, and the remainder to revised data (Bureau of Economic Analysis, 1985).

The effect of these revisions, not yet incorporated in the national health expenditures series, is to lower the share of GNP accounted for by health in the past as well as present. As we undertake our own “benchmark” of national health expenditures estimates, we may well revise spending levels upward for some of the same reasons that the gross national product was increased, returning health's share of GNP to somewhere near its previous levels.

Industry statistics indicate the remarkable turnaround in use of hospital facilities over the last 5 years. After an average growth rate of 2.5 percent from 1967 to 1979, the number of admissions to community hospitals dropped an average of 1.0 percent per year from 1979 to 1985 (Hospital Data Center, 1986). A reversal in the growth trend for inpatient days was just as pronounced, from a pre-1980 average growth of 1.5 percent to a post-1980 average of –2.3 percent. Further, it was the population under 65 years of age for whom admissions and days first began to drop. Use of hospital care by the population 65 years of age or over did not begin to fall until 1984, but admissions and inpatient days for the population under 65 years of age had begun to drop as early as 1982.

What became of the care that would have been provided to those “lost” admissions? To some extent, it never was provided. Second opinions and use reviews eliminated consumption of some services. Other care was provided through nonhospital providers: nursing homes, home health agencies, ambulatory care centers, and traditional practitioner offices. It is clear from the growth of price-deflated spending for personal health care that the U.S. population is not consuming less health care goods and services than before, either in total or per capita.

During the last few years, hospitals have benefited from a slowdown in the growth of prices they paid for inputs. These benefits have been shared with consumers in the form of slower price growth for hospital services. The Consumer Price Index component for hospital care, one measure of output prices, rose 6.4 percent from 1984 to 1985, the smallest change recorded for that component since its creation in 1977.

Price indexes may overstate the actual rate of inflation. Increasing competition in the health care industry has led both distributors and hospitals to engage in price discounting, a phenomenon that is not captured in the CPI or the Producer Price Index. Paying something other than “list” prices is not new: Blue Cross and other insurers (and, until the advent of the prospective payment system, Medicare) based reimbursement on the cost of the service rather than its price. Still, the recent proliferation of preferred provider organizations has extended price discounting to many smaller insurers, including self-insured businesses. Further, heightened competition for customers among product distributors has combined with hospitals' exercise of purchasing power to create widespread discounting of prices paid by hospitals. Thus, even the official estimates of price inflation may overstate the growth of hospital prices.

Despite a drop in the number of admissions and inpatient days during the last few years, hospital profits have increased, at least in the aggregate. Industry statistics for 1985 show that community hospital income was 5.9 percent greater than expenses, part of a 10-year upward trend (Hospital Data Center, 1986). A number of potential explanations for this trend exist. First, the health industry in general has recently become more businesslike in management and decisionmaking in response to cost-containment pressures from insurers and employers alike. Second, hospitals are finding new ways to supplement income from patients. They may do this by entering new enterprises such as freestanding primary care centers. They may also use existing facilities for new purposes. At least one hospital, for example, has begun a commercial flat laundry service to use slack time in its own laundry. Third, large profits have reportedly been made by some types of community hospitals in the first years of Medicare's prospective payment system.

The same pressures that are forcing hospitals to become more businesslike in their operation are also fostering development of alternatives to traditional health care centered around hospitals and family physicians. A new subindustry, the walk-in clinic, has arisen in just a few years. From 150 establishments in 1979, the number of walk-in clinics has grown to 1,850 in 1984, with an annual business of $800 million (Henderson, 1985).

Prepaid health care, usually in the form of a health maintenance organization (HMO), traces its roots back to the Great Depression but did not experience rapid growth until the last decade. In December 1985, 21 million people were enrolled in 480 HMO's across the Nation (InterStudy, 1986). Record-setting enrollment growth, up 25.7 percent from December 1984, laid the groundwork for strong growth in the 1990's, when projections indicate that 25-30 percent of the U.S. population will be enrolled in HMO's.

The appeal of HMO's stems from their ability to manage total patient care by directing patients to and treating them in the appropriate setting (thus reducing hospitalizations), by emphasizing preventive care, and by keeping costs low. The average monthly premium per family for HMO enrollees increased only 4 percent in 1985, to $196 (InterStudy, 1986).

Foreign health spending.

As demonstrated in a study (Schieber, 1985) conducted under the auspices of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), rising levels of per capita national income are associated with higher proportions of that income being spent on health: a 10-percent increase in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita is associated with a 4.4-percent increase in the share of GDP going for health.

The author found “both a fairly consistent pattern of real growth in health spending relative to GDP within countries and greater than proportional spending differentials in countries with higher GDP's .…” He also stated, “Health care price inflation in excess of overall economic inflation continues to be a problem, albeit not the major one, in many, although not all, of the countries. Increases in utilization/intensity of services due to both coverage changes and technological progress, population aging, and large increases in the number of physicians could pose significant new expenditure pressures in most OECD countries in the near future.”

Home health care is another response to cost-containment pressures. Although the exact size—indeed, the exact definition—of the industry is the subject of debate, the rapidity of its growth is not. Medicare and Medicaid benefits alone rose from less than $100 million per year in 1972 to $3 billion per year in 1985.

Changes in financing of care

Like other insurers of health care, the Medicare program has been grappling with the rising cost of health care. It has been seeking ways to protect the access to care not only of current beneficiaries, but also of future retirees.

Medicare's hospital insurance (HI), or Part A, trust fund is still in jeopardy despite the implementation of the hospital prospective payment system. In 1985, 30.6 million people 65 years of age or over, disabled, or suffering from end stage renal disease were covered by the hospital portion of Medicare. This number is expected to increase to 43.4 million 25 years from now. The average couple enrolled in HI can expect to receive more in benefits than they paid into the program (for example, from 7 to 26 times as much for a couple retiring in 1985). Therefore, the program depends on taxes paid by future beneficiaries (current workers) to finance care for current beneficiaries. However, changing demographic conditions will create problems. As stated in the most recent Trustee's report: “There are currently over four covered workers supporting each HI enrollee. This ratio will begin to decline rapidly early in the next century. By the middle of that century, there will be only slightly more than two covered workers supporting each enrollee. Not only are the anticipated reserves and financing of the HI program inadequate to offset this demographic change, but under all but the most optimistic assumptions, the HI trust fund is projected to become exhausted even before the major demographic shift begins to occur. Exhaustion is projected to occur during the late 1990's … and could occur as early as 1993 if the pessimistic assumptions are realized” (Health Care Financing Administration, 1986).

In an effort to extend the life of the HI trust fund, Medicare implemented its prospective payment system (PPS) in stages, beginning in 1983. A primary objective of PPS is to encourage the efficient and effective provision of hospital care by changing the economic incentives of the payment system. PPS controls Medicare payments for inpatient hospital services in about 80 percent of U.S. hospitals and is based on an average cost per case for each of 467 diagnosis related groups. The year-to-year growth in the payment rates is a composite of price inflation and measures of hospital production.

Medicare's supplementary medical insurance (SMI), or Part B, program is financed through enrollee premiums and general tax revenue. Currently, premiums cover about one-quarter of program costs, so considerable tax revenue, $18 billion in 1985, is needed to provide benefits. In 1985, 30.0 million people, most of whom were 65 years of age or over, were enrolled in Medicare Part B; by 1993, that number should reach 34.3 million. SMI benefits are not currently subject to PPS-type reimbursement. However, research is under way to determine methods of introducing cost consciousness into the way in which Part B care is delivered.

Medicare faces problems in establishing cost controls without jeopardizing quality of care. One proposed solution to these problems is to enroll Medicare beneficiaries in HMO's and competitive medical plans (CMP's) on a risk basis. (An HMO or CMP that operates on a risk basis assumes the financial risk of the enrollee's medical care in return for a premium.) Changes in Federal laws regarding reimbursement to HMO's and CMP's, effective February 1985, substantially increased participation in HMO risk enrollment, both by providers and by Medicare enrollees. As of June 1986, 630,000 beneficiaries were enrolled on a risk basis in 132 HMO's and CMP's, 5.8 percent more than in the previous month. (Another 220,000 enrollees were in HMO's reimbursed on a cost basis.) From March 1985 to June 1986, enrollment of Medicare beneficiaries in HMO's operated on a risk basis more than doubled.

The Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of February 1985 allowed HMO's to accept Medicare enrollees on a risk basis. This provided incentives for the government, the industry, and enrollees to participate in such prepaid arrangements. The attraction for the government lies in the ability to control expenditures using the forces of the marketplace—competition and consumer choice. Contracting is more attractive to the industry because of the opportunity for profit and the prospective nature of Medicare payments.

The attractiveness of HMO risk contracts to Medicare beneficiaries stems from the additional benefits available. The Medicare program pays a risk HMO 95 percent of the adjusted average per capita cost (AAPCC) of regular Medicare benefits for enrollees in the HMO's geographic area. However, if the commercial rate charged by the HMO (adjusted for Medicare) is less than the AAPCC, the HMO must do one of four things. It may use the difference to reduce premiums, to provide additional benefits, to offset future premium increases, or it may return the difference to the government. The enrollee continues to pay the Medicare Part B premium, but the reduced HMO premium (as low as zero in some HMO's) and additional benefits, such as prescription drug coverage or unlimited hospitalization, can be an attractive alternative to regular fee-for-service Medicare.

Medicaid authorities also are seeking ways to reduce program costs. After increases of more than 15 percent per year from 1978 to 1981, Medicaid expenditure growth has slowed considerably because of changes initiated by State and Federal Governments in the areas of services, reimbursement, and eligibility.

According to an Intergovernmental Health Policy Project report (1986): “How much of the recent slowdown in the growth of Medicaid expenditures can be attributed to new State initiatives and experimentation in the organization, financing, and reimbursement of services, as opposed to reduced Federal financial participation, or Federal and State policies constricting eligibility and benefits, cannot easily be determined. Nevertheless, several State officials have singled out increased program flexibility, especially with respect to institutional reimbursement and new waiver opportunities, as contributing significantly to their ability to constrain the growth in their programs.”

Among the newest initiatives are competitive bidding programs for inpatient hospital services, which have been implemented in California, Arizona, and Illinois. In States with low hospital occupancy rates, hospitals are willing to bid competitively for the delivery of Medicaid services. In exchange for reduced rates charged to the Medicaid program, hospitals ensure a larger market share and increased patient flow through their facilities.

Hospital profits under prospective payment system.

Despite implementation of the prospective payment system (PPS), Medicare's share of the Nation's hospital bill continues to rise, from 26 percent in 1981 to 29 percent in 1985. In 1985 alone, Medicare expenditures for hospital services rose 10.1 percent, 60 percent faster than the growth in all remaining non-Medicare hospital revenues, which increased 6.2 percent.

The rise in Medicare's share of hospital costs over the past 2 years appears to be inconsistent with the cost-containment aims of PPS. At the same time, persistent claims that PPS had thrust some hospitals into severe financial positions prompted the Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services to investigate the early impact of PPS. The study results indicate that the 2,099 hospitals included in the study earned “a net profit margin of about 15 percent on Medicare revenues and … a return on investment of 25 percent” (Kusserow, 1986). The study highlighted the larger profits recorded by teaching hospitals (47 percent higher than their nonteaching counterparts), by investor-owned facilities (21 percent higher than nonprofit facilities), by urban hospitals (74 percent higher than rural facilities), and by hospitals with greater numbers of Medicare-certified beds. Based on this evidence of high profit margins earned by PPS hospitals, the Office of the Inspector General's report cited the proposed freeze on PPS rates in 1986 as “a positive step.” The report stated that “these Medicare profits resulted, in part, because established PPS rates were based on overstated hospital inpatient operating costs” (Kusserow, 1986).

The Chief Actuary of the Health Care Financing Administration has a different perspective (King, 1986). During the first year of PPS, total expenditures under Medicare for inpatient hospital services were required by law to remain at the same level under PPS as they would have been under the cost-based reimbursement system. When hospitals responded to the incentives of prospective payment by becoming dramatically more cost efficient, profit rates soared.

National health expenditures.

Following are highlights1 of 1985 estimates on national health expenditures:

$425 billion was spent for health in the United States in 1985, an amount equal to 10.7 percent of the gross national product. That figure reflects a commitment of resources equal to $1,721 per person.

Almost one-half of the money spent for health in 1985 was used to purchase hospital and nursing home services. Hospital expenditures, $167 billion in 1985, grew less during the last 2 years than at any other time in the last two decades.

$83 billion, 22 percent of personal health care expenditures, were spent for the services of physicians.

Two-fifths of 1985 health expenditures were made through government programs. This proportion has remained almost unchanged over the last decade despite substantial changes in the size and focus of individual government programs.

Medicare, the Federal program of health insurance for the aged and disabled, spent $71 billion for health care benefits in 1985, 19 percent of all personal health care expenditures. The proportion of spending attributable to Medicare has increased slowly but steadily since the program's inception in 1966.

Medicaid, a joint Federal and State program of health care for certain categories of low-income people, paid $40 billion for health care in 1985. The growth of Medicaid spending since 1981 has been much lower than historical growth rates as State governments have grappled with rising health costs and reduced growth of revenues.

About one-third of health spending was channeled through private health insurance plans. Since 1980, that proportion has remained steady or even fallen a little after years of increase.

Consumers directly paid 28 percent of personal health care expenditures in 1985. The direct pay percentage declined during the 1960's and 1970's with the growth of government programs and private health insurance coverage, but it appears to have leveled off since 1980.

Medicaid also has experimented with HMO's. Enrollment of Medicaid recipients increased substantially over the past year, reaching 561,000 in December 1985, up from 349,000 in June 1984. There are indications, however, that HMO's and Medicaid recipients may not find each other attractive. HMO's find that recipients tend to be high users of services and to have high disenrollment rates (Glenn, 1985b), confounding risk assessment and actuarial ratesetting. For their part, low-income HMO enrollees may need assistance in learning how to use HMO's effectively. The poor may have difficulty securing transportation to single-location medical centers. They may have trouble dealing with the queuing system for appointments and with limitations on emergency room visits. They may lack continuity in care by the same physician or group of physicians and are less likely than others to know how to deal with a medical system that is “predisposed to underserve” (Reichard, 1986).

Employers in the private sector are becoming increasingly aggressive in the pursuit of health care cost containment and are trying a number of paths to this goal (Washington Business Group on Health, 1984). An increasing number are turning to self-insurance in an effort to exert more pressure on providers of care, to benefit from the cash flow advantages of not having to pay premiums, and, in some instances, to avoid State regulation of benefit packages. We estimate that more than one-half of all employees in 1984 were covered by some form of self-insurance, compared with about 10 percent in 1977. The incidence of use review is increasing also as employers, directly or through their insurers, are demanding that uncontrolled use of health care benefits be curtailed.

One development in the area of private sector initiatives is the rise of preferred provider organization (PPO) arrangements. These agreements between providers (groups of physicians, hospitals, and other practitioners) and insurers were originally designed to provide price breaks for the insurer and guaranteed patient loads for the provider. Competition among PPO's, however, has led to variations on that theme: PPO's now offer use review, prepayment options, and other financial and service arrangements (Rice et al., 1985; Cassack, 1985).

Private cost containment.

The National Association of Employers on Health Care recently honored two companies for contributions to health care cost containment. RJR Nabisco, Inc., began operating a prepaid health plan in 1976. It now covers more than 38,000 employees and dependents. In 1978, the company introduced a dental care plan through which employees receive preventive care, endodontia, orthodontia, and oral surgery services. “The company also has implemented other cost-containment measures such as preadmission certification, a preadmission testing requirement, on-site concurrent review in the hospital, and a mandatory second surgical opinion program” (Business Insurance, 1986).

The Xerox Corporation, which “moved from a first-dollar medical benefits plan to a comprehensive plan with copayments and deductibles in 1984, has been able to reduce hospital utilization by about 20 percent as a result of cost-containment efforts… Xerox also offers employees a comprehensive wellness program, which was established in 1978. The company has fitness facilities at 11 of its major offices, and employee-volunteers who coordinate health seminars, contests, and distribution of wellness materials. Xerox is now in the first stages of developing a managed-care system in which the company will negotiate provider contracts with physicians and hospitals” (Business Insurance, 1986).

All of the forces working on the health care industry have a direct effect on consumers of care as well as providers of care. Congressional hearings have been held to determine whether Medicare's prospective payment system, by creating an incentive for hospitals to discharge patients “quicker and sicker,” has caused a deterioration in the health status of the aged population. Health insurance in the aggregate is merely a deferral of payment. The full cost of health care eventually is borne by consumers as a whole in direct costs, higher insurance premiums, higher taxes, or lower wage increases. However, increased coinsurance and deductible requirements present an immediate demand on the individual consumer's pocketbook, a demand that may be difficult to meet if the same illness that requires treatment also reduces income.

Perhaps the most sensitive issue surrounding the effects of current initiatives in health care cost containment is that of indigent care—assuring access to health care for the medically indigent (people with little or no public or private health insurance and without resources to pay for essential services) and assuring the viability of hospitals providing that care. High unemployment has increased the number of people without health insurance coverage. At the same time, public and private health care cost-containment efforts and cutbacks in government spending to aid the indigent have reduced the resources available to finance care for the poor.

Hospitals, affected by these pressures, are seeking ways to control costs and are reluctant to provide care for which they will not be reimbursed. Some hospitals have resorted to economic transfers, “dumping,” in which indigent patients, on arrival, are transferred to public or charity hospitals without first receiving emergency treatment or being stabilized. In some cases, the receiving hospital is not aware of the transfer until the ambulance arrives at the door, often without any medical records or test results on the patients. Dumping has become so prevalent in some areas that State lawmakers are legislating against it. In addition, recently enacted Federal legislation will require Medicare-certified hospitals to provide treatment to or stabilize all emergency patients before transferring them. Violators risk termination or suspension of the hospital's agreement with Medicare, fines of up to $25,000 per violation on both the hospital and the responsible physician, and civil actions.

Dumping adds to the already heavy workloads in hospitals that provide substantial charity care, and patients are faced with long waits in overcrowded clinics and emergency rooms. Transferred patients in emergency rooms tend to be sicker than nontransferred patients because, in some cases, they delay seeking the preventive medical care they cannot afford. Death rates are higher for transferred patients than for nontransferred patients.

“In the past, hospitals paid for charity care by charging private patients more. Today, the ‘Robin Hood’ approach to charity care has started to crumble as … insurers refuse to pay inflated hospital rates” (Fackelmann, 1986). Some hospitals attempt to shift the cost of indigent care by expanding nonpatient services or establishing luxury hospital suites. “ ‘The provision of designer health care for the wealthy may enable some hospitals to serve more poor … ,’ said a report by the Catholic Health Association's task force on health care for the poor” (Fackelmann, 1986).

In 1984, uncompensated care amounted to $9.5 billion, according to industry figures. However, “Not all uncompensated care goes to the poor: About 70 percent is attributable to bad debts. In 1982, investor-owned hospitals classified 97 percent of all uncompensated care as bad debt” (Fackelmann, 1986).

Summary

The health care marketplace in 1985 was a scene of struggle, both among groups and within groups. Although growth of spending slowed, in some cases to 20-year lows, that slowdown was the result of a deceleration of price inflation rather than a fundamental reduction in health care use. The struggle for market share among and between classes of health care providers, the struggle by government to balance social needs with limited resources, and the struggles of providers to resolve the conflict between the ethical and financial aspects of health care all affected the care received by individuals. The industry is in transition, and although transition is healthy, it is not always painless.

Indigent care.

Problems associated with financing indigent care in large, inner-city public hospitals are well publicized, but similar problems permeated America's heartlands in the mid-1980's as hard economic times hit farm communities in the Plains States (Baldwin, 1986). Farmers, unable to make a profit on their crops, moved to cut expenses. They canceled health insurance policies, reduced their coverage, or opted for higher deductibles. As a result, hospital uncompensated care in farm States increased, up 55 percent in Kansas from 1982 to 1984 and up almost 14 percent in Iowa from 1982 to 1985.

Two Iowa hospitals met the problem head on. The Des Moines Charter Community Hospital established a fund to finance free care to indigent farmers and convinced area physicians to donate their services at the same time. The Marshalltown Medical and Surgical Center, in conjunction with independent professionals (physicians, dentists, and podiatrists who receive substantially reduced compensation from a church-sponsored fund) created a similar program for farmers in north-central Iowa. Both hospitals' programs avoid the label of “charity care.” In neither facility are collections of bills from indigent farmers attempted: one hospital indicates that bills can be paid whenever finances permit; the other simply provides a bill, but does not pursue collection.

Although much uncompensated care is provided in urban areas of farm States, the severity of the problem is felt more acutely in rural hospitals. Small rural facilities with few beds and falling admissions find it difficult to absorb an increase in uncompensated care.

Physician unionization.

The impact of the changing structure of the health care industry is vividly illustrated in the physician sector. The number of physicians is growing more rapidly than the population served. Increased competition for patients has forced many physicians, especially new graduates, to consider employment rather than independent practice (Sorian, 1986). High costs of medical education leave most new physicians with substantial debt and little ability to finance the creation of an independent practice. More are turning to employment in hospitals, health maintenance organizations, and other health care groups and institutions.

As employees, some physicians feel they are losing control over the quality of care that they deliver. Pressured by employers and insurers to contain costs, physicians are increasingly concerned that reductions in diagnostic testing and limits on hospitalization may lower the quality of service provided. In addition, the oversupply of physicians in some areas permits employers to hire physicians at relatively low salaries. As a result of these factors, unionization of physicians, although small in numbers, appears to be on the rise.

Home health care.

Home health care, as defined in the National Health Accounts, includes preventive, supportive, therapeutic, or rehabilitative medical care provided in a home setting. A broader industry definition includes supportive social services. Regardless of definition, home health care has been an area of rapid growth that shows little indication of slowing.

For patients and their families, home health care may be an attractive substitute for institutional care. Home care services allow patients to remain in their own homes, which may add to the psychological well-being of the patient and involve less cost. Families tend to be relieved of fears and concerns for an absent family member. They also avoid the stress and physical drain caused by repeated visits to an institution that may be some distance away.

Home health care is a small but rapidly growing segment of the health care delivery system, increasing at an estimated average annual rate of 20-25 percent in recent years. According to projections of total industry spending, the cost of home health products and services will grow from $9 billion in 1985 to $16 billion in 1990, with 70 percent of the total going for services (Frost and Sullivan, 1983).

The home health care industry has changed dramatically. From delivery of nursing care by family and friends, through visiting nurse associations, the industry has evolved into a complex health delivery system that involves government; visiting nurse associations; private nonprofit, proprietary, and facility-based providers; and a variety of services. The most significant change in the home health industry has been the emergence of proprietary agencies, particularly chains, as the largest single form of organization. Studies indicate that home health agency (HHA) chains, perceiving home health to be a lucrative market, have been growing rapidly. Corporations controlling the large HHA chains appear to be closely related to other primary health industries, such as pharmaceutical businesses, nursing care facilities, and freelance medical staffing agencies (Williams, Gaumer, and Cella, 1984).

Hospitals are moving into home health care in increasing numbers. In 1984, 42 percent of the Nation's hospitals offered home health services; that fraction was expected to reach 65 percent in 1985 (Glenn, 1985a). HHA's also play an important role in hospitals' efforts to maintain revenues. The hospital home health department's most important function is to serve as a “feeder” for the hospital, identifying potential patients and directing them to the hospital. Hospital-based home health care also allows the hospital, under pressure from the prospective payment system to reduce inpatient cost, to discharge patients yet continue to generate revenue from their care. Home health departments offer a wider base over which to spread overhead costs, and they serve as a marketing tool as well. Further, home health care reduces the hospital's exposure to malpractice suits (Cassak, 1984; Ginzberg, Balinsky, and Ostow, 1984).

A legislative change in 1980 that eased Medicare certification requirements for proprietary HHA's in States without licensure laws opened the way for the rapid growth of proprietary HHA's. The number of certified proprietary HHA's increased fourfold from 1982 to 1985, reaching 1,943 (32 percent of all HHA's).

Despite its rapid growth, there are indications that the home health industry is not keeping up with demand for home health services. Patients are being discharged “quicker and sicker” as a result of hospitals' cost-containment efforts, and home health agencies are scrambling to take care of these new patients. Meanwhile, other patients, those requiring the social-type home health care, are being cut off from services they had come to depend on, such as nutrition and day-care programs (Grady, 1986).

It has been estimated that people 65 years of age or over receive 85–90 percent of the home health care furnished (Ginzberg, Balinsky, and Ostow, 1984; Frost and Sullivan, 1983; Cassak, 1984). Therefore, the aging of the population is an important factor for industry growth. The population 65 years of age or over is projected to increase from 29 million people (or 11.7 percent of the population) in 1985 to 32 million (or 12.4 percent of the population) in 1990 (Social Security Administration, 1986). The average annual rate of growth of the aged population is expected to be 2 1/3 times faster than the rate of growth of the overall population from 1985 to 1990.

Medicare spending for home health care has grown from $60 million in fiscal year 1968 (1.2 percent of total payments for benefits) to $2.3 billion in 1985 (3.3 percent of benefit payments), an annual growth rate of 24 percent. In 1984, 1.5 million Medicare beneficiaries used 40 million home health visits. Visiting nurse associations served the largest number of people, 31 percent, and had the largest number of visits, 12 million. However, proprietary and hospital-based agencies ranked first and second in the percent of total charges billed to Medicare (27 percent and 16 percent, respectively). The share of total HHA charges billed by proprietary agencies almost doubled from 1982 to 1984.

HHA's certified by Medicare are required to submit annual cost reports. A recent analysis of cost reports for 1982 submitted by home health agencies that were not part of a hospital or nursing home indicates that agency costs for services, medical equipment, and supplies provided to Medicare patients represent approximately 50 percent of total agency costs.

Indian Health Service.

The rapidly rising cost of health care affects government as well as the private sector. Facing future budget reductions and continuing declines in real per capita expenditures, the Indian Health Service (IHS) is finding ways to meet the needs of its growing constituency.

American Indians and Alaskan Natives living on or near reservations rely predominately on IHS for the health services they require. The needs of these people are great. Unemployment rates are high on many reservations, and one out of every three Indians lives at or below the poverty level. Associated with high unemployment and poverty are death and disease rates that are among the highest in the Nation. The death rate for Indians under 65 years of age is 2 1/2 times as great as that in the general population. Lack of sanitation facilities and safe drinking water make infectious disease a persistent problem, especially in newborns. Death rates from injuries and alcoholism are three and four times the U.S. average, respectively.

Despite Federal appropriations of only $800 million in 1985, IHS maintains a network of 45 hospitals and 137 outpatient facilities. These, along with tribally operated facilities and contract care, provide medical care to 980,000 Indians in the IHS service population. A small budget has not deterred IHS from striving for and achieving substantial success in upgrading the health status of Indians. Among IHS accomplishments recorded in States with reservations are a substantial increase from 1970 to 1980 in life expectancy at birth; a 93-percent decrease in the gastrointestinal death rate from 1955 to 1982; and achievement of a mortality rate for Indian infants during the first 28 days of life that is lower than the U.S. rate.

As both provider and financer of medical care, IHS works to identify prevalent health problems and their causes and to design a cost-effective method for implementing a solution. Lifestyle changes have been promoted. In 1986, most IHS facilities are smoke free. The Zuni Diabetes Project succeeded in introducing a fitness program for diabetics in that tribe, resulting in weight reduction and removal from medication of some of the participants. A patient care information system has been implemented that permits more efficient patient processing and retrieval of patient histories. Studies on ambulatory care delivery allowed IHS to develop a method for optimally allocating health practitioners to outpatient care centers, a method adopted by other Federal agencies.

Sometimes, less traditional methods have been developed for dealing with specific Indian health problems:

“A joint tribal-IHS program has substantially reduced gastroenteritis, a summertime killer of Indian babies. In 1971, the Papago tribal health organization and IHS devised a program that identified infants at high risk and prepared tribal workers to train mothers and to screen infants for the disease. Tribal workers made a presentation in English and O'Odham throughout the reservation that wove local settings and legends with the causes and prevention of gastroenteritis. The outreach workers assessed the stage and severity of the problem in the children whom they saw and, as appropriate, gave mothers dietary advice, administered electrolytes, or made referrals. At summer's end, no Papago baby had died from gastroenteritis, and evaluation of the program revealed that the children whom it had reached had 26 percent fewer outpatient visits and 56 percent fewer hospital days related to that condition. Further analysis determined that education of Papago mothers had had the greatest impact. Gastroenteritis control has subsequently become an annual campaign of the Papago tribe, and the program's design has been applied to upper respiratory infections, unwanted pregnancies, and other health problems” (Indian Health Service, 1986).

Figure 1. Percent change in national health expenditures and gross national product, and national health expenditures as a percent of gross national product: Calendar years 1966-85.

Figure 2. Percent change in the Consumer Price Index from the same month of the previous year for all items and medical care: 1965-86.

Figure 3. Factors affecting the growth of personal health care expenditures: Calendar years 1980-85.

Figure 4. Total health expenditures as a share of gross domestic product: Selected countries, 1965 and 1983.

Figure 5. Measures of economic activity in the health care industry and in the overall economy: United States, 1985.

Figure 6. The Nation's health dollar: 1985.

Table 1. National health expenditures aggregate, per capita, percent distribution, and average annual percent change, by source of funds: Selected calendar years 1965-85.

| Item | 1985 | 1984 | 1983 | 1982 | 1981 | 1980 | 1975 | 1970 | 1967 | 1965 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||

| National health expenditures | $425.0 | $390.2 | $357.2 | $323.6 | $287.0 | $248.1 | $132.7 | $75.0 | $51.5 | $41.9 |

| Private | 250.2 | 230.7 | 209.7 | 188.4 | 165.8 | 142.9 | 76.4 | 47.2 | 32.5 | 30.9 |

| Public | 174.8 | 159.5 | 147.5 | 135.3 | 121.2 | 105.2 | 56.3 | 27.8 | 19.0 | 11.0 |

| Federal | 124.4 | 111.7 | 102.7 | 93.2 | 83.3 | 71.0 | 37.0 | 17.7 | 11.9 | 5.5 |

| State and local | 50.4 | 47.8 | 44.8 | 42.1 | 37.9 | 34.2 | 19.3 | 10.1 | 7.0 | 5.5 |

| Per capita amount | ||||||||||

| National health expenditures | $1,721 | $1,595 | $1,473 | $1,348 | $1,207 | $1,054 | $590 | $349 | $247 | $205 |

| Private | 1,013 | 943 | 865 | 784 | 697 | 607 | 340 | 220 | 156 | 152 |

| Public | 708 | 652 | 608 | 563 | 510 | 447 | 250 | 129 | 91 | 54 |

| Federal | 504 | 456 | 424 | 388 | 350 | 302 | 165 | 82 | 57 | 27 |

| State and local | 204 | 195 | 185 | 175 | 159 | 145 | 86 | 47 | 34 | 27 |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||||

| National health expenditures | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Private | 58.9 | 59.1 | 58.7 | 58.2 | 57.8 | 57.6 | 57.5 | 63.0 | 63.2 | 73.8 |

| Public | 41.1 | 40.9 | 41.3 | 41.8 | 42.2 | 42.4 | 42.5 | 37.0 | 36.8 | 26.2 |

| Federal | 29.3 | 28.6 | 28.8 | 28.8 | 29.0 | 28.6 | 27.9 | 23.6 | 23.2 | 13.2 |

| State and local | 11.9 | 12.3 | 12.5 | 13.0 | 13.2 | 13.8 | 14.5 | 13.5 | 13.7 | 13.0 |

| Average annual percent change from previous year shown | ||||||||||

| U.S. population | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.1 | — |

| Gross national product | 5.7 | 11.0 | 7.4 | 3.7 | 11.7 | 8.9 | 9.5 | 7.5 | 7.6 | — |

| National health expenditures | 8.9 | 9.2 | 10.4 | 12.8 | 15.7 | 15.6 | 12.1 | 13.4 | 10.8 | — |

| Private | 8.5 | 10.0 | 11.3 | 13.6 | 16.0 | 15.1 | 10.1 | 13.3 | 2.5 | — |

| Public | 9.6 | 8.1 | 9.1 | 11.6 | 15.2 | 16.2 | 15.2 | 13.6 | 31.3 | — |

| Federal | 11.4 | 8.7 | 10.2 | 11.9 | 17.3 | 16.4 | 16.0 | 14.0 | 46.7 | — |

| State and local | 5.3 | 6.8 | 6.4 | 11.1 | 10.9 | 15.8 | 13.8 | 12.8 | 13.6 | — |

| Number in millions | ||||||||||

| U.S. population1 | 246.9 | 244.7 | 242.5 | 240.2 | 237.8 | 235.3 | 224.9 | 215.1 | 208.6 | 204.1 |

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||

| Gross national product | $3,989 | $3,775 | $3,402 | $3,166 | $3,053 | $2,732 | $1,598 | $1,015 | $816 | $705 |

| Percent of gross national product | ||||||||||

| National health expenditures | 10.7 | 10.3 | 10.5 | 10.2 | 9.4 | 9.1 | 8.3 | 7.4 | 6.3 | 5.9 |

July 1 social security area population estimates.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 2. National health expenditures aggregate and average annual percent change, by type of expenditure: Selected calendar years 1965-85.

| Type of expenditure | 1985 | 1984 | 1983 | 1982 | 1981 | 1980 | 1975 | 1970 | 1967 | 1965 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||

| National health expenditures | $425.0 | $390.2 | $357.2 | $323.6 | $287.0 | $248.1 | $132.7 | $75.0 | $51.5 | $41.9 |

| Health services and supplies | 409.5 | 374.5 | 341.8 | 309.4 | 273.8 | 236.2 | 124.3 | 69.6 | 47.6 | 38.4 |

| Personal health care | 371.4 | 341.1 | 314.7 | 286.5 | 254.7 | 219.7 | 117.1 | 65.4 | 44.5 | 35.9 |

| Hospital care | 166.7 | 155.3 | 146.8 | 135.2 | 119.1 | 101.6 | 52.4 | 28.0 | 18.4 | 14.0 |

| Physicians' services | 82.8 | 75.4 | 68.4 | 61.8 | 54.8 | 46.8 | 24.9 | 14.3 | 10.1 | 8.5 |

| Dentists' services | 27.1 | 24.6 | 21.7 | 19.5 | 17.3 | 15.4 | 8.2 | 4.7 | 3.4 | 2.8 |

| Other professional services | 12.6 | 10.9 | 9.3 | 8.0 | 6.8 | 5.7 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.0 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 28.5 | 26.5 | 24.5 | 22.1 | 20.7 | 18.8 | 11.9 | 8.0 | 5.8 | 5.2 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 7.5 | 7.0 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| Nursing home care | 35.2 | 31.9 | 29.4 | 26.7 | 23.9 | 20.4 | 10.1 | 4.7 | 2.8 | 2.1 |

| Other personal health care | 11.0 | 9.4 | 8.3 | 7.4 | 6.8 | 5.9 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| Program administration and net cost of private health insurance | 26.2 | 22.6 | 17.1 | 13.5 | 10.6 | 9.2 | 4.0 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 1.7 |

| Government public health activities | 11.9 | 10.9 | 9.9 | 9.3 | 8.5 | 7.3 | 3.2 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 15.4 | 15.6 | 15.4 | 14.3 | 13.2 | 11.9 | 8.4 | 5.4 | 3.8 | 3.5 |

| Noncommercial research1 | 7.4 | 6.8 | 6.2 | 5.9 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 3.3 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.5 |

| Construction | 8.1 | 8.9 | 9.2 | 8.4 | 7.6 | 6.5 | 5.1 | 3.4 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| Average annual percent change from previous year shown | ||||||||||

| National health expenditures | 8.9 | 9.2 | 10.4 | 12.8 | 15.7 | 13.3 | 12.1 | 13.4 | 10.8 | — |

| Health services and supplies | 9.3 | 9.6 | 10.5 | 13.0 | 15.9 | 13.7 | 12.3 | 13.5 | 11.3 | — |

| Personal health care | 8.9 | 8.4 | 9.8 | 12.5 | 15.9 | 13.4 | 12.4 | 13.7 | 11.4 | — |

| Hospital care | 7.3 | 5.8 | 8.6 | 13.5 | 17.2 | 14.2 | 13.4 | 15.0 | 14.7 | — |

| Physicians' services | 9.9 | 10.1 | 10.7 | 12.8 | 16.9 | 13.4 | 11.7 | 12.2 | 9.4 | — |

| Dentists' services | 9.9 | 13.3 | 11.6 | 12.5 | 12.3 | 13.3 | 11.6 | 12.2 | 9.4 | — |

| Other professional services | 15.2 | 17.1 | 17.0 | 16.9 | 19.8 | 16.8 | 10.4 | 8.2 | 10.4 | — |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 7.4 | 8.4 | 10.6 | 6.9 | 10.4 | 9.4 | 8.3 | 11.5 | 5.5 | — |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 8.3 | 12.0 | 6.4 | 9.4 | 5.6 | 9.9 | 10.1 | 15.5 | 3.7 | — |

| Nursing home care | 10.6 | 8.5 | 9.9 | 12.0 | 17.1 | 15.2 | 16.4 | 19.2 | 15.7 | — |

| Other personal health care | 16.0 | 13.2 | 13.0 | 9.2 | 14.2 | 9.5 | 12.8 | 10.1 | 16.3 | — |

| Program administration and net cost of private health insurance | 16.1 | 31.7 | 26.8 | 27.1 | 15.9 | 18.1 | 7.2 | 8.0 | 13.3 | — |

| Government public health activities | 9.1 | 9.6 | 6.6 | 10.0 | 16.3 | 18.2 | 17.2 | 17.2 | 4.4 | — |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | −1.2 | 1.6 | 7.7 | 8.4 | 10.3 | 7.3 | 9.2 | 12.1 | 4.5 | — |

| Noncommercial research1 | 8.9 | 10.1 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 3.2 | 10.3 | 11.1 | 3.7 | 7.9 | — |

| Construction | −9.0 | -4.1 | 9.8 | 11.2 | 16.3 | 5.1 | 8.1 | 18.4 | 1.8 | — |

Research and development expenditures of drug companies and other manufacturers and providers of medical equipment and supplies are excluded from “research expenditures,” but they are included in the expenditure class in which the product falls.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 3. National health expenditures, by source of funds and type of expenditure: Calendar years 1980 and 1985.

| Year and type of expenditure | All sources | Private | Government | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| All private funds | Consumer | Other1 | Total | Federal | State and local | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Total | Direct | Private insurance | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Amount in billions | |||||||||

| 1985 | |||||||||

| National health expenditures | $425.0 | $250.2 | $238.9 | $105.6 | $133.3 | $11.3 | $174.8 | $124.4 | $50.4 |

| Health services and supplies | 409.5 | 244.3 | 238.9 | 105.6 | 133.3 | 5.4 | 165.2 | 117.2 | 48.0 |

| Personal health care | 371.4 | 224.0 | 219.1 | 105.6 | 113.5 | 4.9 | 147.5 | 112.6 | 34.8 |

| Hospital care | 166.7 | 76.9 | 74.8 | 15.6 | 59.3 | 2.1 | 89.8 | 71.6 | 18.2 |

| Physicians' services | 82.8 | 58.7 | 58.7 | 21.8 | 36.8 | 0.0 | 24.1 | 19.7 | 4.4 |

| Dentists' services | 27.1 | 26.5 | 26.5 | 17.2 | 9.3 | — | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Other professional services | 12.6 | 9.0 | 8.8 | 6.0 | 2.8 | 0.1 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 0.9 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 28.5 | 25.8 | 25.8 | 21.7 | 4.0 | — | 2.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 7.5 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 5.2 | 0.9 | — | 1.5 | 1.3 | 0.1 |

| Nursing home care | 35.2 | 18.7 | 18.4 | 18.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 16.5 | 9.4 | 7.1 |

| Other personal health care | 11.0 | 2.3 | — | — | — | 2.3 | 8.6 | 6.0 | 2.6 |

| Program administration and net cost of private health insurance | 26.2 | 20.4 | 19.8 | — | 19.8 | 0.6 | 5.8 | 3.2 | 2.7 |

| Government public health activities | 11.9 | — | — | — | — | — | 11.9 | 1.4 | 10.5 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 15.4 | 5.9 | — | — | — | 5.9 | 9.6 | 7.2 | 2.4 |

| Noncommercial research2 | 7.4 | 0.4 | — | — | — | 0.4 | 7.0 | 6.4 | 0.6 |

| Construction | 8.1 | 5.5 | — | — | — | 5.5 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 1.8 |

| 1980 | |||||||||

| National health expenditures | 248.1 | 142.9 | 135.6 | 63.0 | 72.6 | 7.3 | 105.2 | 71.0 | 34.2 |

| Health services and supplies | 236.2 | 138.7 | 135.6 | 63.0 | 72.6 | 3.0 | 97.5 | 65.8 | 31.7 |

| Personal health care | 219.7 | 133.2 | 130.5 | 63.0 | 67.5 | 2.7 | 86.5 | 62.5 | 24.0 |

| Hospital care | 101.6 | 47.7 | 46.6 | 7.9 | 38.7 | 1.1 | 53.9 | 41.1 | 12.8 |

| Physicians' services | 46.8 | 34.2 | 34.2 | 14.2 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 12.6 | 9.6 | 3.0 |

| Dentists' services | 15.4 | 14.8 | 14.8 | 10.1 | 4.7 | — | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Other professional services | 5.7 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.4 |

| Drugs and medical sundries | 18.8 | 17.1 | 17.1 | 15.0 | 2.2 | — | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Eyeglasses and appliances | 5.1 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 0.4 | — | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| Nursing home care | 20.4 | 9.2 | 9.1 | 8.9 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 11.2 | 6.0 | 5.2 |

| Other personal health care | 5.9 | 1.4 | — | — | — | 1.4 | 4.5 | 3.1 | 1.4 |

| Program administration and net cost of private health insurance | 9.2 | 5.4 | 5.1 | — | 5.1 | 0.3 | 3.8 | 2.0 | 1.7 |

| Government public health activities | 7.3 | — | — | — | — | — | 7.3 | 1.3 | 6.0 |

| Research and construction of medical facilities | 11.9 | 4.3 | — | — | — | 4.3 | 7.7 | 5.2 | 2.4 |

| Noncommercial research2 | 5.4 | 0.3 | — | — | — | 0.3 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 0.5 |

| Construction | 6.5 | 4.0 | — | — | — | 4.0 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 2.0 |

Spending by philanthropic organizations, industrial inplant health services, and privately financed construction.

Research and development expenditures of drug companies and other manufacturers and providers of medical equipment and supplies are excluded from “research expenditures,” but they are included in the expenditure class in which the product falls.

NOTE: 0.0 denotes less than $50 million.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 4. Personal health care expenditures aggregate, per capita, and percent distribution, by source of funds: Selected calendar years 1965-85.

| Year | Total | Direct patient payments | Third parties | Medicare1 | Medicaid2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| All third parties | Private health insurance | Other private funds | Government | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Total | Federal | State and local | ||||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||

| 1965 | $35.9 | $18.5 | $17.3 | $8.7 | $0.8 | $7.9 | $3.6 | $4.3 | — | — |

| 1970 | 65.4 | 26.5 | 38.9 | 15.3 | 1.1 | 22.4 | 14.5 | 7.9 | $7.1 | $5.2 |

| 1975 | 117.1 | 38.1 | 79.0 | 31.2 | 1.6 | 46.3 | 31.4 | 14.9 | 15.6 | 13.5 |

| 1980 | 219.7 | 63.0 | 156.7 | 67.5 | 2.7 | 86.5 | 62.5 | 24.0 | 35.7 | 25.2 |

| 1985 | 371.4 | 105.6 | 265.8 | 113.5 | 4.9 | 147.5 | 112.6 | 34.8 | 70.5 | 39.8 |

| Per capita amount | ||||||||||

| 1965 | $176 | $91 | $85 | $42 | $4 | $39 | $18 | $21 | (3) | (3) |

| 1970 | 304 | 123 | 181 | 71 | 5 | 104 | 68 | 37 | (3) | (3) |

| 1975 | 521 | 169 | 351 | 139 | 7 | 206 | 140 | 66 | (3) | (3) |

| 1980 | 934 | 268 | 666 | 287 | 11 | 367 | 266 | 102 | (3) | (3) |

| 1985 | 1,504 | 428 | 1,076 | 460 | 20 | 597 | 456 | 141 | (3) | (3) |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||||

| 1965 | 100.0 | 51.6 | 48.4 | 24.2 | 2.2 | 22.0 | 10.1 | 11.9 | — | — |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 40.5 | 59.5 | 23.4 | 1.7 | 34.3 | 22.2 | 12.1 | 10.9 | 8.0 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 32.5 | 67.5 | 26.7 | 1.3 | 39.5 | 26.8 | 12.7 | 13.3 | 11.6 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 28.7 | 71.3 | 30.7 | 1.2 | 39.4 | 28.4 | 10.9 | 16.2 | 11.5 |

| 1985 | 100.0 | 28.4 | 71.6 | 30.6 | 1.3 | 39.7 | 30.3 | 9.4 | 19.0 | 10.7 |

Subset of Federal funds.

Subset of Federal and State and local funds.

Calculation of per capita estimates is inappropriate.

NOTE: Per capita amounts are based on July 1 social security area population estimates.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 5. Hospital care expenditures aggregate, per capita, and percent distribution, by source of funds: Selected calendar years 1965-85.

| Year | Total | Direct patient payments | Third parties | Medicare1 | Medicaid2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| All third parties | Private health insurance | Other private funds | Government | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Total | Federal | State and local | ||||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||

| 1965 | $14.0 | $2.3 | $11.6 | $5.7 | $0.3 | $5.6 | $2.4 | $3.1 | — | — |

| 1970 | 28.0 | 3.2 | 24.8 | 9.7 | 0.4 | 14.7 | 9.5 | 5.1 | $5.1 | $2.2 |

| 1975 | 52.4 | 4.2 | 48.2 | 18.8 | 0.6 | 28.9 | 20.1 | 8.8 | 11.5 | 4.8 |

| 1980 | 101.6 | 7.9 | 93.7 | 38.7 | 1.1 | 53.9 | 41.1 | 12.8 | 25.9 | 9.6 |

| 1985 | 166.7 | 15.6 | 151.2 | 59.3 | 2.1 | 89.8 | 71.6 | 18.2 | 48.5 | 14.8 |

| Per capita amount | ||||||||||

| 1965 | $68 | $12 | $57 | $28 | $1 | $27 | $12 | $15 | — | — |

| 1970 | 130 | 15 | 115 | 45 | 2 | 68 | 44 | 24 | (3) | (3) |

| 1975 | 233 | 19 | 215 | 84 | 2 | 128 | 90 | 39 | (3) | (3) |

| 1980 | 432 | 34 | 398 | 165 | 5 | 229 | 175 | 55 | (3) | (3) |

| 1985 | 675 | 63 | 612 | 240 | 9 | 364 | 290 | 74 | (3) | (3) |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||||

| 1965 | 100.0 | 16.8 | 83.2 | 41.1 | 2.2 | 39.9 | 17.4 | 22.5 | — | — |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 11.4 | 88.6 | 34.6 | 1.6 | 52.4 | 34.1 | 18.4 | 18.2 | 8.0 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 7.9 | 92.1 | 35.9 | 1.1 | 55.1 | 38.4 | 16.7 | 21.9 | 9.1 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 7.8 | 92.2 | 38.1 | 1.1 | 53.1 | 40.4 | 12.6 | 25.5 | 9.4 |

| 1985 | 100.0 | 9.3 | 90.7 | 35.6 | 1.3 | 53.8 | 43.0 | 10.9 | 29.1 | 8.9 |

Subset of Federal funds.

Subset of Federal and State and local funds.

Calculation of per capita estimates is inappropriate.

NOTE: Per capita amounts are based on July 1 social security area population estimates.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 6. Physician care expenditures aggregate, per capita, and percent distribution, by source of funds: Selected calendar years 1965-85.

| Year | Total | Direct patient payments | Third parties | Medicare1 | Medicaid2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| All third parties | Private health insurance | Other private funds | Government | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Total | Federal | State and local | ||||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||

| 1965 | $8.5 | $5.2 | $3.3 | $2.7 | $0.0 | $0.6 | $0.2 | $0.4 | — | — |

| 1970 | 14.3 | 6.5 | 7.8 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 0.9 | $1.6 | $0.7 |

| 1975 | 24.9 | 8.5 | 16.4 | 9.9 | 0.0 | 6.6 | 4.7 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 1.9 |

| 1980 | 46.8 | 14.2 | 32.6 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 12.6 | 9.6 | 3.0 | 7.9 | 2.4 |

| 1985 | 82.8 | 21.8 | 61.0 | 36.8 | 0.0 | 24.1 | 19.7 | 4.4 | 17.1 | 3.4 |

| Per capita amount | ||||||||||

| 1965 | $42 | $26 | $16 | $13 | $0 | $3 | $1 | $2 | — | — |

| 1970 | 67 | 30 | 36 | 22 | 0 | 14 | 10 | 4 | (3) | (3) |

| 1975 | 111 | 38 | 73 | 44 | 0 | 29 | 21 | 8 | (3) | (3) |

| 1980 | 199 | 61 | 139 | 85 | 0 | 54 | 41 | 13 | (3) | (3) |

| 1985 | 335 | 88 | 247 | 149 | 0 | 98 | 80 | 18 | (3) | (3) |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||||

| 1965 | 100.0 | 61.6 | 38.4 | 31.4 | 0.1 | 6.9 | 1.8 | 5.1 | — | — |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 45.4 | 54.6 | 33.6 | 0.1 | 20.9 | 14.9 | 6.0 | 11.3 | 4.8 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 34.1 | 65.9 | 39.5 | 0.1 | 26.3 | 18.8 | 7.6 | 13.5 | 7.5 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 30.4 | 69.6 | 42.6 | 0.1 | 26.9 | 20.6 | 6.3 | 16.9 | 5.2 |

| 1985 | 100.0 | 26.3 | 73.7 | 44.5 | 0.1 | 29.1 | 23.8 | 5.3 | 20.6 | 4.1 |

Subset of Federal funds.

Subset of Federal and State and local funds.

Calculation of per capita estimate is inappropriate.

NOTES: 0.0 denotes less than $50 million for aggregate amounts, and 0 denotes less than $.50 for per capita amounts. Per capita amounts are based on July 1 social security area population estimates.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 7. Nursing home care expenditures aggregate, per capita, and percent distribution, by source of funds: Selected calendar years 1965-85.

| Year | Total | Direct patient payments | Third parties | Medicare1 | Medicaid2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| All third parties | Private health insurance | Other private funds | Government | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Total | Federal | State and local | ||||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||

| 1965 | $2.1 | $1.3 | $0.7 | $0.0 | $0.0 | $0.7 | $0.5 | $0.3 | — | — |

| 1970 | 4.7 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 0.9 | $0.3 | $1.4 |

| 1975 | 10.1 | 4.3 | 5.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 5.6 | 3.2 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 4.8 |

| 1980 | 20.4 | 8.9 | 11.5 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 11.2 | 6.0 | 5.2 | 0.4 | 9.8 |

| 1985 | 35.2 | 18.1 | 17.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 16.5 | 9.4 | 7.1 | 0.6 | 14.7 |

| Per capita amount | ||||||||||

| 1965 | $10 | $7 | $4 | $0 | $0 | $3 | $2 | $1 | — | — |

| 1970 | 22 | 11 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 6 | 4 | (3) | (3) |

| 1975 | 45 | 19 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 14 | 11 | (3) | (3) |

| 1980 | 87 | 38 | 49 | 1 | 1 | 48 | 26 | 22 | (3) | (3) |

| 1985 | 143 | 73 | 69 | 1 | 1 | 67 | 38 | 29 | (3) | (3) |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||||

| 1965 | 100.0 | 64.5 | 35.5 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 34.3 | 22.2 | 12.1 | – | – |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 50.3 | 49.7 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 48.6 | 28.6 | 20.0 | 5.6 | 30.3 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 42.7 | 57.3 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 56.0 | 31.4 | 24.6 | 2.9 | 47.9 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 43.6 | 56.4 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 54.9 | 29.6 | 25.3 | 1.9 | 48.0 |

| 1985 | 100.0 | 51.4 | 48.6 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 46.9 | 26.8 | 20.2 | 1.7 | 41.8 |

Subset of Federal funds.

Subset of Federal and State and local funds.

Calculation of per capita estimates is inappropriate

NOTES: 0.0 denotes less than $50 million for aggregate amounts, and 0 denotes less than $.50 for per capita amounts. Per capita amounts are based on July 1 social security area population estimates.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 8. Other personal health care expenditures1 aggregate, per capita, and percent distribution, by source of funds: Selected calendar years 1965-85.

| Year | Total | Direct patient payments | Third parties | Medicare2 | Medicaid3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| All third parties | Private health insurance | Other private funds | Government | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Total | Federal | State and local | ||||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||

| 1965 | $11.3 | $9.6 | $1.7 | $0.3 | $0.4 | $1.0 | $0.6 | $0.4 | — | — |

| 1970 | 18.4 | 14.4 | 3.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 1.0 | $0.1 | $0.9 |

| 1975 | 29.7 | 21.1 | 8.6 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 5.2 | 3.4 | 1.8 | 0.4 | 2.1 |

| 1980 | 50.9 | 32.0 | 18.8 | 8.6 | 1.5 | 8.7 | 5.7 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 3.4 |

| 1985 | 86.7 | 50.2 | 36.5 | 17.0 | 2.4 | 17.0 | 11.9 | 5.2 | 4.4 | 6.8 |

| Per capita amount | ||||||||||

| 1965 | $56 | $47 | $8 | $1 | $2 | $5 | $3 | $2 | — | — |

| 1970 | 85 | 67 | 18 | 4 | 3 | 12 | 7 | 5 | (4) | (4) |

| 1975 | 132 | 94 | 38 | 11 | 4 | 23 | 15 | 8 | (4) | (4) |

| 1980 | 216 | 136 | 80 | 37 | 6 | 37 | 24 | 13 | (4) | (4) |

| 1985 | 351 | 203 | 148 | 69 | 10 | 69 | 48 | 21 | (4) | (4) |

| Percent distribution | ||||||||||

| 1965 | 100.0 | 84.7 | 15.3 | 2.3 | 4.0 | 9.1 | 5.1 | 3.9 | — | — |

| 1970 | 100.0 | 78.6 | 21.4 | 4.4 | 3.3 | 13.7 | 8.3 | 5.4 | 0.8 | 4.7 |

| 1975 | 100.0 | 71.1 | 28.9 | 8.4 | 3.1 | 17.4 | 11.5 | 5.9 | 1.5 | 6.9 |

| 1980 | 100.0 | 63.0 | 37.0 | 17.0 | 2.9 | 17.2 | 11.2 | 5.9 | 2.9 | 6.7 |

| 1985 | 100.0 | 57.9 | 42.1 | 19.6 | 2.8 | 19.7 | 13.7 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 7.9 |

Personal health care expenditures other than those for hospital care, physicians' services, and nursing home care.

Subset of Federal funds.

Subset of Federal and State and local funds.

Calculation of per capita estimates is inappropriate

NOTE: Per capita amounts are based on July 1 social security area population estimates.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 9. Expenditures for health services and supplies under public programs, by type of expenditure and program: Calendar year 1985.

| Program area | All expenditures | Personal health care | Administration | Public health activities | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total | Hospital care | Physicians' services | Dentists' services | Other professional services | Drugs and sundries | Eye-glasses and appliances | Nursing home care | Other | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Amount in billions | ||||||||||||

| Public and private spending | $409.5 | $371.4 | $166.7 | $82.8 | $27.1 | $12.6 | $28.5 | $7.5 | $35.2 | $11.0 | $26.2 | $11.9 |

| All public programs | 165.2 | 147.5 | 89.8 | 24.1 | 0.6 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 16.5 | 8.6 | 5.8 | 11.9 |

| Federal | 117.2 | 112.6 | 71.6 | 19.7 | 0.3 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 9.4 | 6.0 | 3.2 | 1.4 |

| State and local | 48.0 | 34.8 | 18.2 | 4.4 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 7.1 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 10.5 |

| Medicare1 | 72.3 | 70.5 | 48.5 | 17.1 | — | 2.0 | — | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.8 | — |

| Medicaid2 | 41.8 | 39.8 | 14.8 | 3.4 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 2.4 | — | 14.7 | 2.7 | 2.0 | — |

| Federal | 23.2 | 21.9 | 8.1 | 1.9 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1.4 | — | 8.1 | 1.5 | 1.3 | — |

| State and local | 18.6 | 17.9 | 6.8 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.0 | — | 6.6 | 1.2 | 0.7 | — |

| Other State and local public assistance programs | 1.9 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | — | 0.5 | 0.1 | — | — |

| Veterans' Administration | 8.7 | 8.7 | 6.9 | 0.1 | 0.0 | — | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.1 | — |

| Defense Department3 | 8.4 | 8.3 | 6.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | — | 0.0 | — | — | 1.4 | 0.1 | — |

| Workers compensation | 8.2 | 6.3 | 3.2 | 2.6 | — | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | — | — | 1.9 | — |

| Federal | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | — | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | — | — | 0.0 | — |

| State and local | 7.9 | 6.0 | 3.0 | 2.6 | — | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | — | — | 1.9 | — |

| State and local hospitals4 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 7.3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Other public programs for personal health care5 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | — | 2.5 | 0.1 | — |

| Federal | 2.9 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | — | 1.2 | 0.0 | — |

| State and local | 1.8 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | — | 1.4 | 0.1 | — |

| Government public health activities | 11.9 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 11.9 |

| Federal | 1.4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.4 |

| State and local | 10.5 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 10.5 |

| Medicare and Medicaid6 | 113.5 | 109.7 | 63.3 | 20.4 | 0.5 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 15.3 | 3.3 | 3.8 | — |

Total Federal expenditures from trust funds for benefits and administration. Trust fund income includes premium payments paid by or on behalf of enrollees.

Includes funds paid into the Medicare trust funds by States under “buy-in” agreements to cover premiums for public assistance recipients and for people who are medically indigent.

Includes care for retirees and military dependents.

Expenditures not offset by revenues.

Includes program spending for maternal and child health; vocational rehabilitation medical payments; temporary disability insurance medical payments; Public Health Service and other Federal hospitals; Indian health services; alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health; and school health.

Excludes “buy-in” premiums paid by Medicaid for supplementary medical insurance coverage of aged and disabled Medicaid recipients eligible for coverage.

NOTE: 0.0 denotes less than $50 million.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 10. Personal health care expenditures, by type of expenditure and selected source of funds: Calendar years 1985 and 1980.

| Source of payment | Total | Hospital care | Physicians' services | Dentists' services | Other professional services | Drugs and sundries | Eyeglasses and appliances | Nursing home care | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Amount in billions | |||||||||

| 1985 | |||||||||

| Personal health care expenditures | $371.4 | $166.7 | $82.8 | $27.1 | $12.6 | $28.5 | $7.5 | $35.2 | $11.0 |

| Direct patient payments | 105.6 | 15.6 | 21.8 | 17.2 | 6.0 | 21.7 | 5.2 | 18.1 | — |

| Third-party payments | 265.8 | 151.2 | 61.0 | 9.8 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 2.4 | 17.1 | 11.0 |

| Private health insurance | 113.5 | 59.3 | 36.8 | 9.3 | 2.8 | 4.0 | 0.9 | 0.3 | — |

| Philanthropy and industrial inplant | 4.9 | 2.1 | 0.0 | — | 0.1 | — | — | 0.3 | 2.3 |

| Government | 147.5 | 89.8 | 24.1 | 0.6 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 16.5 | 8.6 |

| Federal | 112.6 | 71.6 | 19.7 | 0.3 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 9.4 | 6.0 |

| Medicare | 70.5 | 48.5 | 17.1 | — | 2.0 | — | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.1 |

| Medicaid | 21.9 | 8.1 | 1.9 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 1.4 | — | 8.1 | 1.5 |

| Other | 20.2 | 15.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 3.4 |

| State and local | 34.8 | 18.2 | 4.4 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 7.1 | 2.6 |

| Medicaid | 17.9 | 6.8 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.0 | — | 6.6 | 1.2 |

| Other | 17.0 | 11.4 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1.4 |

| 1980 | |||||||||

| Personal health care expenditures | 219.7 | 101.6 | 46.8 | 15.4 | 5.7 | 18.8 | 5.1 | 20.4 | 5.9 |

| Direct patient payments | 63.0 | 7.9 | 14.2 | 10.1 | 2.8 | 15.0 | 4.1 | 8.9 | — |

| Third-party payments | 156.7 | 93.7 | 32.6 | 5.3 | 2.9 | 3.8 | 0.9 | 11.5 | 5.9 |

| Private health insurance | 67.5 | 38.7 | 20.0 | 4.7 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | — |

| Philanthropy and industrial inplant | 2.7 | 1.1 | 0.0 | — | 0.1 | — | — | 0.1 | 1.4 |

| Government | 86.5 | 53.9 | 12.6 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 11.2 | 4.5 |

| Federal | 62.5 | 41.1 | 9.6 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 6.0 | 3.1 |

| Medicare | 35.7 | 25.9 | 7.9 | — | 0.7 | — | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Medicaid | 13.6 | 5.2 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.8 | — | 5.3 | 0.5 |

| Other | 13.1 | 10.0 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 2.1 |

| State and local | 24.0 | 12.8 | 3.0 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 5.2 | 1.4 |

| Medicaid | 11.6 | 4.4 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.6 | — | 4.5 | 0.4 |

| Other | 12.4 | 8.4 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

NOTES: 0.0 denotes less than $50 million. Medicaid expenditures include Part B premium payments to Medicare by States under “buy-in” agreements to cover premiums for eligible Medicaid recipients.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 11. Payments into Medicare trust funds and percent distribution, by type of fund and source of income: Fiscal years 1971 and 1985.

| Year and source of income | Total | Hospital insurance trust fund | Supplementary medical insurance trust fund | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Amount in billions | Percent distribution | Amount in billions | Percent distribution | Amount in billions | Percent distribution | |

| 1985 | ||||||

| Total | $75.5 | 100.0 | $50.9 | 100.0 | $24.6 | 100.0 |

| Payroll taxes | 46.9 | 62.1 | 46.9 | 92.0 | — | — |

| General revenues | 18.8 | 24.8 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 17.9 | 72.8 |

| Premiums | 5.6 | 7.4 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 5.5 | 22.5 |

| Interest | 4.3 | 5.7 | 3.2 | 6.2 | 1.2 | 4.7 |

| 1971 | ||||||

| Total | 8.5 | 100.0 | 6.0 | 100.0 | 2.5 | 100.0 |

| Payroll taxes | 5.0 | 58.2 | 5.0 | 82.5 | — | — |

| General revenues | 2.1 | 24.8 | 0.9 | 14.5 | 1.2 | 49.5 |

| Premiums | 1.3 | 14.7 | — | — | 1.3 | 49.8 |

| Interest | 0.2 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 |

NOTE: 0.0 denotes less than $50 million.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Footnotes

Reprint requests: Carol Pearson, L1, 1705 Equitable Building, 6325 Security Boulevard, Baltimore, Maryland 21207.

An expanded discussion and detailed data are presented in: Lazenby, H., Levit, K. R., and Waldo, D. R.: National health expenditures, 1985. Health Care Financing Notes. HCFA Pub. No. 03232. Office of the Actuary, Health Care Financing Administration. Washington. U.S. Government Printing Office, Sept. 1986. A copy may be obtained from: Publications and Information Resources, Room 1A9 Oak Meadows Building, 6325 Security Boulevard, Baltimore, Md. 21207.

References

- Baldwin M. Farm crisis means indigent care is a rural as well as an urban problem. Modern Healthcare. 1986 Apr.16(8):46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Economic Analysis. Survey of Current Business. No. 12. Vol. 65. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Dec. 1985. Revised estimates of the National Income and Product Accounts, 1929-85: An introduction. Bureau of Economic Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Business Insurance. Cost containment efforts lauded. 1986 Jun 16;20(24):32. Copyright 1986. Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved. [Google Scholar]

- Cassak D. Hospitals in home healthcare, an industry in transition. Health Industry Today. 1984 Jul;47(7):16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cassak D. Preferred Provider Organizations: Creating a new healthcare delivery system. Health Industry Today. 1985 Aug.48(8) [Google Scholar]

- Fackelmann K. Religious hospitals juggle mission. Washington Report on Medicine and Health. 1986 Apr.40(17) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost and Sullivan. Home Healthcare Products and Services: Markets in the US. New York: Frost and Sullivan; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Ginzberg E, Balinsky W, Ostow M. Home Health Care, Its Role in the Changing Health Services Market. Totowa, N.J.: Rowman and Allanheld; 1984. [Google Scholar]