Abstract

Nationwide, 8 percent of all employment-related health plans were self-insured in 1984, which translates into more than 175,000 self-insured plans according to our latest study of independent health plans. The propensity of an organization to self-insure differs primarily by its size, with large establishments more likely to self-insure. In the overwhelming majority of cases, the self-insured benefit was hospital and/or medical. Among employers who self-insure, 23 percent self-administer, and the remaining 77 percent hire a commercial insurance company, Blue Cross/Blue Shield plan, or an independent third-party administrator to administer the health plan.

Introduction

The number of employment-related health plans that are self-insured has increased so dramatically in the past decade that the vast majority of large establishments now use some form of self-insurance, and the practice is growing among smaller establishments. A 1985 study by Towers, Perrin, Forster, and Crosby, employee benefit consultants, cited in Business Insurance (1986), found that 62 percent of large companies self-funded their health plans in 1985, 54 percent self-funded in 1984, and 43 percent self-funded in 1982. It is estimated that 67 percent will have self-funded in 1986.

Self-insurance is attractive to employers because it tends to be less expensive than purchased insurance, and it gives them greater control over plan design. Savings accrue in a variety of ways, which include not having to pay State-levied premium taxes and exemption from offering State-mandated benefits. A potential implication of these savings is a slowdown in the rate of growth of personal health care expenditures, either as a result of organizations providing less extensive health plan benefits or providing equivalent benefits at a lower cost.

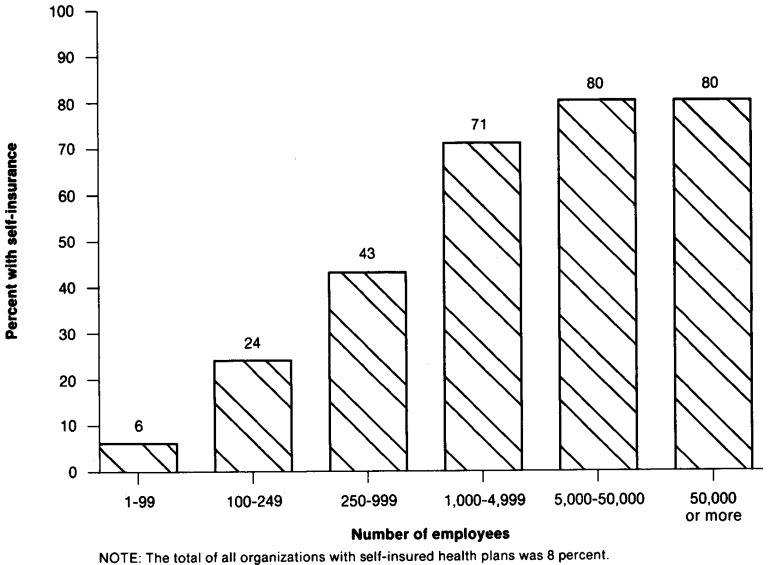

Even though only 8 percent of all employment-related health plans are self-insured, more than 50 percent of all employees with health insurance participate in these self-insured plans. Some reasons employers do not offer health insurance coverage to employees may be because they consider health insurance to be too expensive a benefit, most employees are covered under a relative's plan, or most employees are part-time workers. The low percent of self-insured health plans may be misleading, because more than 90 percent of employers have less than 100 employees and rarely self-insure. However, among the remaining organizations with 100 or more employees in 1984, the proportion of employers who self-insured increased rapidly with organizational size—in 1984, one-third of those with 100 or more employees, more than one-half of those with 250 or more employees, three-fourths of those with 1,000 or more employees, and four-fifths of those with 5,000 or more employees offered at least one health benefit that was self-insured. In the overwhelming majority of cases, the self-insured benefit was hospital and/or medical; in more than one-third of the cases, the self-insured benefits included dental and/or vision.

Employers who self-insure may also self-administer their health plans. In 1984, however, more than three-fourths of employers who self-insured chose instead to enlist the services of a third party to conduct all or some of the administrative functions that relate to offering an insurance plan. The growth in the number of self-insured plans has therefore led to the development and growth of a major new market area for insurance companies and independent third-party administrators (TPA's). Originally, insurance companies dominated this market because of their preexisting client bases and longstanding administrative and claims processing expertise. Recently, independent TPA's have managed to carve out a sizable market niche within specific geographic localities.

Presented in this article are detailed findings of a study conducted by the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), Division of National Cost Estimates. The focus is on exploring the prevalence of self-insurance among employment-related health plans, including those sponsored by business establishments and associations of varying sizes and types, religious organizations, governments, post-secondary educational institutions, and unions. Also provided is information on the kinds of benefits for which organizations of varying sizes and types are likely to be self-insured. In addition, the extent to which organizations self-administer or pay for the services of a third-party administrator is explored. Finally, findings are presented on the percent of organizations of varying characteristics that offer employees a health maintenance organization (HMO) option.

Drawing on a larger, more diverse sample of employers than any previous study of self-insurance, and weighted to obtain a representative national sample, this study provides the most comprehensive data on the topic of self-insurance collected to date. In addition to the survey results, a section on definitions of terms relating to self-insurance and past legislative activities and judicial decisions that have encouraged the increase in self-insured health plans is provided, along with a discussion of the potential implications of an increase in the percent of employees covered by self-insured health plans and a summary of areas in which HCFA expects to conduct further research.

Self-insurance concepts

Private health insurance plans have traditionally been fully insured indemnity or service plans and are commonly referred to as “purchased” insurance. Either Blue Cross/Blue Shield or commercial insurance companies assume the immediate financial risk, and the employer is only responsible for paying premiums. Premiums include an actuarially determined amount earmarked for claim payments and an allowance for reserves, as required by State insurance departments (usually about 20 percent of paid claims per year), that adjusts for the time lag between when claims are incurred and when claims are paid. Premiums also include a retention to cover the insurance company's cost of doing business and provide a margin for safety. These costs include administrative charges, risk charges that protect the carrier should the contract be terminated with insufficient reserves to pay incurred claims, profits (in the case of insurance companies) or surpluses.(in the case of Blue Cross/Blue Shield plans), brokers' commissions, and State premium taxes (2 to 4 percent of premiums) if purchased from commercial insurers.

In response to pressures from employers, insurers have devised such products as retrospective premium arrangements and delayed premium arrangements that improve the employer's financial position while preserving the basic insurance arrangement. In the case of a “retro” arrangement, the insurer sets premiums so that expected claims and expenses (but not margin amounts) are covered. These arrangements require, however, that the employer compensate the insurer with an additional premium should the actual benefit experience be higher than anticipated or if the contract is terminated. In the case of delayed-premium arrangements, insurers may allow employers 2 or 3 months leeway before the first payment comes due.

Even these special arrangements have not satisfactorily allowed all employers to keep up with the rising cost of purchased insurance. In addition, large firms especially have realized that their stable work forces experience relatively minor fluctuations in the volume of claims each year. As a result, they could just as easily predict the annual increase in their experience-rated premium as an insurance company while also retaining funds previously assigned to an insurance company until needed. This would result in improved cash reserves. Further encouraged by the incentives built into the Employee Retirement and Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA), many employers have switched over to self-insuring their health plans.

ERISA, enacted as a pension protection measure, includes a clause (Section 514) that allows States to continue to exercise regulatory authority over the “business of insurance,” but preempts States from classifying employee benefit plans as insurance. This clause has been interpreted in such a way as to allow self-insured health plans to be exempted from State regulations concerning mandated benefits, State premium taxes, and reserve requirements for unpaid and unreported claims. This feature is particularly attractive to multistate employers who would prefer to avoid numerous and conflicting State insurance regulations. The exemption is not to be extended to fully insured plans according to the Supreme Court decision of Metropolitan Life Insurance Company versus Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 1985.1

Single-employer health plans, which are sponsored by one employer for its own employees, almost always qualify under ERISA. Multiple-employer plans, which are Taft-Hartley jointly administered plans (characterized by participation with a union), usually qualify under ERISA and are therefore exempt from State regulation. However, multiple-employer plans—known as MET's or, more recently, as Multiple Employer Welfare Arrangements (MEWA's)—are not qualified for an exemption because they fail various antitrust restrictions.

With self-insurance, the ultimate responsibility for paying health care claims lies with the employer and, consequently, the ultimate cost to the employer may increase as well as decrease. Usually, however, self-insurance allows employers to pay less for the health benefits provided to employees by reducing the difference between the premium paid by the employer and the amount the insurance carrier ultimately pays out in claims. Employers are able to exert more control over benefit design (they need not budget a retention for risk charges and insurance company profits or surpluses), and they can aim to lower claims administration and overhead costs. It is relatively simpler to reduce those premium cost components that are related to administration and not related directly to benefit payments than to reduce the cost of claimed benefit payments. Reducing the cost of benefits would require expensive data collection efforts on patterns of practice and use, claims review, and coordination of benefits.

For the most part, the terms “self-insurance” and “self-funding” mean essentially the same thing and are often substituted for one another. Occasionally, however, there are definitional difficulties in using these terms interchangeably because plans that are self-funded are not necessarily self-insured. For example, employers might self-fund a retrospective premium agreement on a conventional group insurance contract, but there is no effective risk shift because employers are liable for additional premiums. Funding implies setting aside money to pay for future claims. Insurance implies the assumption of risk by accepting responsibility for reimbursing providers for employees' health claims. Plans that self-insure must also self-fund by setting aside money on an unfunded basis through a general asset plan or by establishing a 501(c)(9) trust, also known as a Voluntary Employee Beneficiary Association (VEBA). Substantial growth of VEBA's occurred in the 1950's when jointly administered plans, under the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947, began using tax-exempt trusts. In addition, because VEBA's are able to restrict membership according to “objective conditions reasonably related to employment,” they are able to influence their aggregate claims costs, thereby making them attractive to employers. Currently, however, unfunded plans are more common than funded plans, partly as a result of the 1984 Deficit Reduction Act (DEFRA) that limited the amount of assets that could be held tax free in a trust. The Wyatt Company, employee benefit consultants, found that 27 percent of the employers they surveyed in 1986 were unfunded because they had not established a 501(c)(9) trust for their self-insured medical plans, and 22 percent were funded because they had established a 501(c)(9) trust.

Not all health plans are totally self-insured or totally fully insured. Increasingly, they combine elements of fully-insured and self-insured plans, as in the case of minimum-premium plans, stop-loss coverage, and administrative-services-only agreements. This requires innovative methods for spreading risk and administrative responsibility among employers, insurance companies, and third-party administrators. By so doing, employers minimize inconvenience and the risk of paying out more in benefits than predicted while gaining many of the advantages associated with self-insurance.

Employers who partially self-insure may limit their risk exposure by engaging a third-party insurer to provide stop-loss coverage beyond a certain dollar threshold or by purchasing a minimum-premium plan. Stop-loss coverage is a reinsurance policy in that it protects the self-insured policyholder against excessive claims on either an aggregate-plan basis or specific-individual basis. As with a purely self-insured plan, the employer assumes all responsibility for the financial risk of random claim fluctuations below the stop-loss threshold. Stop-loss coverage, when it is purchased as an accompaniment to self-insurance, is more expensive than pure self-insurance on the average. However, it protects the employer against large unforeseen claims and random claim fluctuations while still minimizing premiums, taxes, and reserves.

Minimum-premium plans were first developed by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company for Caterpillar Tractor in 1964. Responsibility for payment is allocated between the employer and the insurer, with the employer liable for paying up to 90 percent of expected claims and with the insurer liable for paying anything in excess of the 90-percent figure. This arrangement retains for the carrier the full complement of underwriting, claims processing, claims review, and administrative services. In addition, the carrier usually establishes reserves for the full risk of the account. Under a minimum-premium plan arrangement, employers may avoid paying premium taxes on 90 percent of claims funds.

The term “partially self-insured” is sometimes used to describe an employer who self-insures for some benefits and purchases commercial insurance for other benefits. Employers who fully or partially self-insure, unlike employers who purchase insurance coverage, have an opportunity to either self-administer their health plan or purchase administrative services from a third party. The first administrative-services-only (ASO) contract was written in 1970 by the Equitable Life Assurance Society for the 3-M Company. Since that time, third-party administrators have developed a more limited version of ASO known as claims services only (CSO). Third-party administrators include insurance carriers and independent contract administrators. For a fee, they provide any or all of the following services:

Marketing.

Claims processing.

Premium collection.

Claims review.

Accounting.

Computing.

Consulting.

Purchasing ASO or CSO relieves the employer of all or some administrative responsibility but does nothing to relieve the employer of the risk associated with paying health benefits.

Insurers have facilitated the shift to self-insurance to protect themselves from the inevitable. Rapidly rising health care costs in the late 1970's, because they were coincident with economy-wide high interest rates, allowed insurers to temporarily finance the lag between rapidly increasing claims expenses and eventual premium increases through cash flow underwriting. As health care costs continued to rise, the prospect of being able to keep pace with premium increases seemed less likely. Raising premiums caused a certain degree of concern because insurers would then run the risk of losing business. However, by providing administrative services, stop-loss coverage, and minimum-premium plans, insurers could maintain an association with the employer and enhance the possibility of selling them other, more profitable lines of insurance such as life and casualty. In addition, should the employer wish to return to purchased insurance, as some have, the insurer would be readily available.

Self-insurance findings

Findings on the rate of self-insurance among all employer organizations, including business establishments, unions, religious organizations, governments,2 and schools are presented in Figure 1. On a nationwide basis, it was found that 8 percent of all organizations that provide health insurance coverage for their employees did so, in full or in part, through some form of self-insurance. Although only 6 percent of the more than 2.2 million organizations with 1 to 99 employees that offer health plans are self-insured, that percent rises rapidly with organization size.3 This translates into coverage by more than 175,000 self-insured health plans for more than 50 percent of the work force.

Figure 1. Percent of organizations with self-insured health plans, by size: 1984.

Nationwide percents and totals in Table 1 were derived from a random sample, stratified by size and Standard Industrial Code (in the case of business establishments) of approximately 28,500 business establishments, unions, religious organizations, post-secondary schools, and governmental units. (See the Technical Note for additional information on the study design.) The sample findings were then weighted to account for the fact that not all types and sizes of organizations were sampled (or responded) with equal probability. This weighting process removed the potential bias that results when strata with unequal sampling and/or response rates are pooled to produce nationwide estimates.

Table 1. Number and percent of organizations with self-insured health plans, by type of organization and size: 1984.

| Type of organization | Number of employees | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Total | 1-99 | 100-249 | 250-999 | 1,000-4,999 | 5,000-49,999 | 50,000 or more | 0 or missing | |

| All organizations | ||||||||

| Total with health plans | 2,344,335 | 2,234,875 | 59,610 | 30,700 | 12,180 | 4,030 | 230 | 2,710 |

| Number of self-insured | 176,424 | 136,881 | 14,190 | 13,266 | 8,655 | 3,238 | 184 | 10 |

| Percent of self-insurance | 8 | 6 | 24 | 43 | 71 | 80 | 80 | (4) |

| Cumulative percent1 | — | 8 | 36 | 55 | 74 | 80 | — | (4) |

| Business establishments | ||||||||

| Total with health plans | 2,286,810 | 2,197,000 | 48,600 | 24,300 | 10,500 | 3,530 | 180 | 2,700 |

| Number of self-insured | 163,626 | 132,000 | 11,000 | 10,100 | 7,500 | 2,880 | 146 | 0 |

| Percent of self-insurance | 7 | 6 | 23 | 41 | 71 | 82 | 81 | 0 |

| Cumulative percent1 | — | 7 | 36 | 54 | 74 | 82 | — | (1) |

| Unions | ||||||||

| Total with health plans | 3,672 | 620 | 700 | 1,290 | 815 | 220 | 17 | 10 |

| Number of self-insured | 2,227 | 200 | 330 | 810 | 685 | 175 | 17 | 10 |

| Percent of self-insurance | 61 | 32 | 47 | 63 | 84 | 80 | 3100 | (4) |

| Cumulative percent1 | — | 61 | 66 | 72 | 83 | 81 | — | (4) |

| Religious organizations | ||||||||

| Total with health plans | 780 | 470 | 100 | 110 | 70 | 30 | — | — |

| Number of self-insured | 184 | 36 | 25 | 51 | 50 | 22 | — | — |

| Percent of self-insurance | 24 | 8 | 25 | 46 | 71 | 73 | — | — |

| Cumulative percent1 | — | 24 | 51 | 59 | 72 | — | — | — |

| Governmental units2 | ||||||||

| Total with health plans | 49,111 | 35,600 | 9,000 | 3,950 | 440 | 115 | 6 | — |

| Number of self-insured | 9,446 | 4,490 | 2,590 | 2,020 | 265 | 78 | 3 | — |

| Percent of self-insurance | 19 | 13 | 29 | 51 | 60 | 68 | 350 | — |

| Cumulative percent1 | — | 19 | 37 | 52 | 62 | 67 | — | — |

| Post-secondary schools | ||||||||

| Total with health plans | 3,962 | 1,185 | 1,210 | 1,050 | 355 | 135 | 27 | — |

| Number of self-insured | 941 | 155 | 245 | 285 | 155 | 83 | 18 | — |

| Percent of self-insurance | 24 | 13 | 20 | 27 | 44 | 61 | 367 | — |

| Cumulative percent1 | — | 24 | 28 | 35 | 50 | 62 | — | — |

Cumulative percent for a given cell is the percent of organizations of that size or greater that are self-insured.

Governmental units include counties, municipalities, townships, and school districts.

Based on a very limited number of observations (5 or fewer).

Statistically unreliable.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Organization size

In this section, all employees (full-time and part-time) are included in the data. Findings support the theory that the more employees in the organization, the greater the propensity to self-insure. Fewer than 1 out of every 10 organizations with less than 100 employees self-insure compared with 4 out of every 5 organizations with more than 5,000 employees. The most likely explanation for high rates of self-insurance among large establishments is that their risk pools are large and actuarially enable them to better predict their employees' health expenses. The size at which organizations seem to be risk indifferent as to how they insure (self versus purchased) is the 250 to 1,000 employee range. This corresponds with the minimum group size in which health benefits are actuarially predictable with a reasonable degree of confidence. There is currently some movement among smaller firms to self-insure because of the increasing availability of pooling arrangements and specially designed stop-loss and minimum-premium arrangements that help reduce the risk factor.

To assess the quality and validity of our results, we compared the 8-percent self-insurance rate with previously reported findings by other organizations that study self-insurance. At first glance, our results appeared too low. For example, both Coopers and Lybrand (1984), a public accounting firm, and the Wyatt Company (1984), employee benefit consultants, reported self-insurance rates of approximately 60 percent for the organizations in their respective studies. When examined more closely, however, this statistic is wholly consistent with our findings (Table 1) that 53 percent of organizations with more than 250 employees and 74 percent of organizations with more than 1,000 employees self-insure. Wyatt Company's results were further similar to ours in that 75 percent of their respondents with 7,501 to 10,000 employees self-funded their health plans in 1984. The difference in the overall self-insurance rate is because the other surveys were designed to encompass a relatively limited range of firms, most of which had more than 100 employees, including a preponderance of firms with more than 500 employees. In other words, the sampling frame of these studies does not correspond, as does ours, to the actual size distribution of firms with health plans. The large volume of organizations with 1 to 99 employees and their propensity to purchase health insurance from commercial insurance companies or Blue Cross and Blue Shield rather than to self-insure weight the nationwide self-insurance rate downward.

Organization type

When organizations are compared by type, business establishments and unions show the greatest disposition towards self-insurance. Among business establishments, 74 percent of all firms with more than 1,000 employees self-insure. Traditionally, business establishments have chosen self-insurance as a way to avoid costly premium taxes and State mandated benefits, thereby improving their bottom line. Some businesses prefer to maintain as large an operating budget as possible, paying for health claims as they are incurred, rather than to prepay a fixed amount for health insurance. Unions have an even greater penchant for self-insurance. As shown in Table 1, 83 percent of unions with greater than 1,000 employees have some form of self-insurance. Even unions with less than 100 employees are moderately likely to be self-insured. Possible explanations for these high rates among union health plans are that unions have traditionally been involved in employee benefit innovation and their aim to deliver comprehensive benefit packages is bolstered when the same level of benefits can be delivered more economically. As depicted in Table 1, religious organizations, governments, and schools with large numbers of employees are somewhat less likely than either businesses or unions with large numbers of employees to self-insure. These organizations usually have fixed incomes and therefore, in many instances, prefer to purchase insurance with the knowledge that there is no potential for cost overruns.

It is important when comparing self-insurance rates of different types of organizations against one another to compare similar size categories. If one compares only totals, those organizations with a disproportionate number of small establishments will tend to have a lower overall self-insurance rate—17 percent of unions have 1 to 99 plan participants, 32 percent of schools have 1 to 99 plan participants, 61 percent of religious organizations have 1 to 99 plan participants, 85 percent of governmental units have 1 to 99 plan participants, and 96 percent of business establishments have 1 to 99 plan participants.

Self-insured benefits

Findings on those benefits for which an organization is most likely to self-insure are shown in Table 2. Survey respondents were asked to indicate whether they self-insured for hospital and/or medical benefits, dental and/or vision benefits, or both. Organizations that do not self-insure for one or both benefit groups may still provide these benefits through purchased insurance.

Table 2. Percent of self-insured health plans that self-insure for hospital and/or medical, dental and/or vision, or both, by organization type and size: 1984.

| Organizations type and size | Self-insured for— | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Hospital and/or medical | Dental and/or vision | |

|

| ||

| Percent | ||

| All types and sizes combined | 91 | 49 |

| Type | ||

| Business establishments | 91 | 48 |

| Unions | 93 | 77 |

| Religious organizations | 93 | 45 |

| Governmental units1 | 99 | 51 |

| Post-secondary schools | 98 | 30 |

| Size2 | ||

| 1 or more | 91 | 49 |

| 100 or more | 98 | 52 |

| 250 or more | 98 | 59 |

| 1,000 or more | 99 | 74 |

| 5,000 or more | 99 | 81 |

Governmental units include counties, municipalities, townships, and school districts.

Number of employees of that size or greater that are self-insured.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

As shown in the table, business establishments, religious organizations, and governments are approximately twice as likely to self-insure for hospital and/or medical benefits than for dental and/or vision benefits. The propensity of an organization to self-insure for one or both of these benefit groups generally increases as organization size increases. Unions, if they self-insure, are more inclined than other types of organizations to self-insure for dental and/or vision benefits; post-secondary schools are less inclined to self-insure for these benefits.

Plan administration

The rise in popularity of self-insured health plans has not only changed the way in which risk is distributed among employers and insurance companies but it has also changed the way in which employers administer their health plans. No longer is it always the sole responsibility of insurance companies to conduct administrative functions; employers increasingly either purchase these services from independent third-party administrators or process claim payments in-house. This change reflects the general belief that improved control over how claims are paid is potentially as integral an element of cost containment as are lower claims costs.

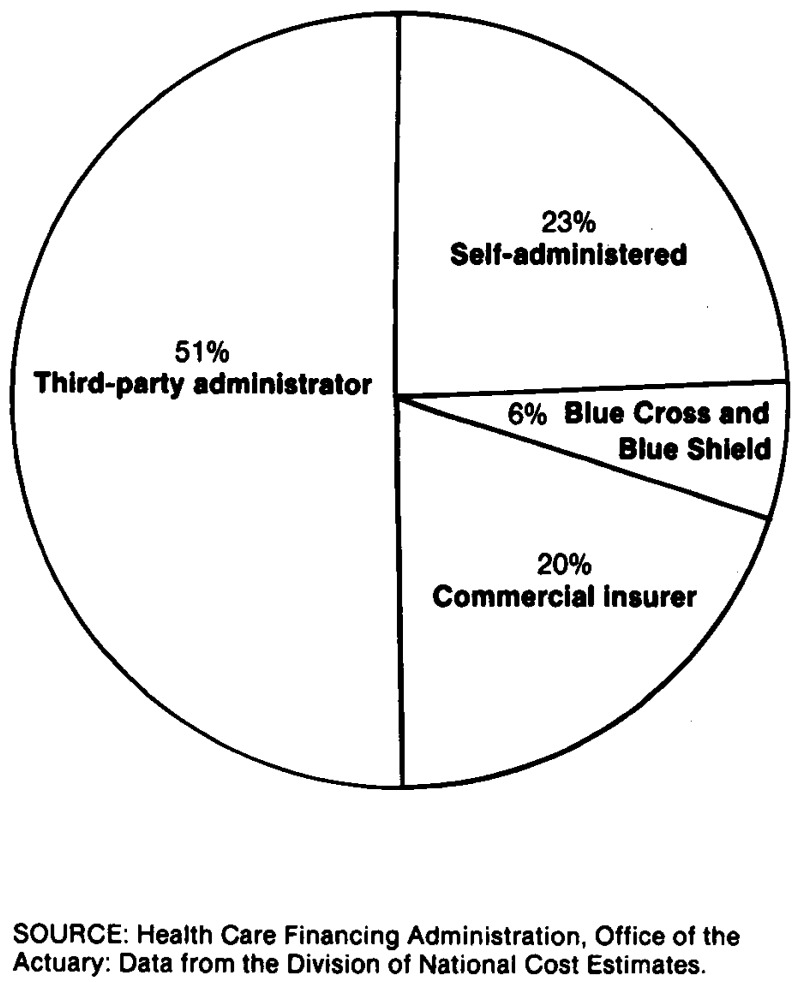

To get a better estimate of the magnitude of these new administrative arrangements and their characteristics, respondents to the survey were asked, among other things, to identify the organization responsible for processing claims and handling other administrative functions as either self-administered or other administered. Those who were other administered were then asked to specifically identify their outside administrator in order for us to determine the extent to which firms choose Blue Cross and Blue Shield, commerical insurance companies, or TPA's. In 1984, 23 percent of self-insured organizations also self-administered, 51 percent hired a TPA, 6 percent contracted with Blue Cross and Blue Shield, and 20 percent enlisted the administrative services of a commerical insurer (Figure 2). Organizations with 250 or more employees sometimes hire multiple administrators to handle the full range of administrative functions.

Figure 2. Percent of organizations with self-insured health plans, by type of administrative arrangement: 1984.

In the marketplace, Blue Cross and Blue Shield administrative services are known as Administrative Services Contracts and Cost Plus Contracts, and commercial insurers' services are known as Administrative Services Only. There is reason to believe that the use of TPA's as health-plan administrators, as opposed to insurance companies' administrative services, will increase. TPA's are the most popular outside administrator choice among small firms, where the growth in self-insurance is expected to grow fastest. In addition, TPA's are thought to be less expensive. Temple, Barker, and Sloane, Inc., in a 1984 study of third-party administrators (Moore, 1984), found that TPA's spent about $1.75 per month per employee on claims processing and $1.75 per month on corporate overhead, and commercial carriers spent $4.75 per month on claims processing and $1.25 per month on corporate overhead.

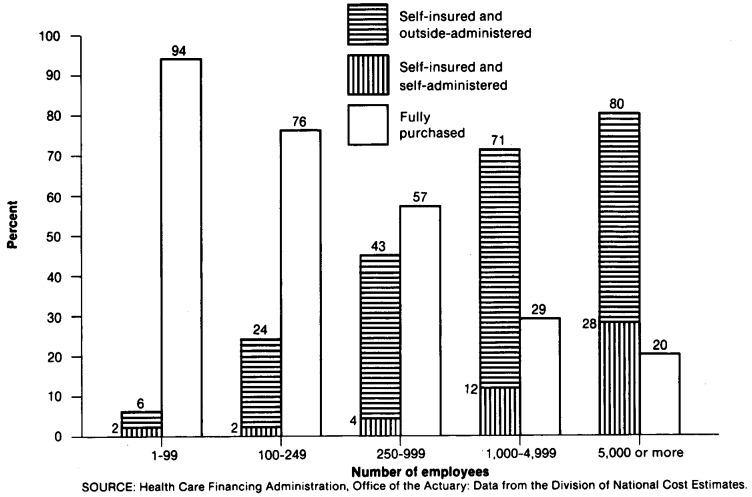

Currently, the potential market for third-party administrative services is limited to, at most, the 8 percent of all employment-related health plans that are either fully or partially self-insured. Furthermore, it is likely that some core percent of self-insured plans will always prefer to self-administer. The remaining 92 percent of employment-related health plans are fully purchased and therefore do not require third-party administrative services. Provided in Figure 3 is a breakdown by organization size of the percent of organizations that purchased insurance, were both self-insured and self-administered, and were self-insured with an outside adminstrator in 1984.

Figure 3. Organizations with health plans, by type of administrative arrangement and size: 1984.

The propensity of employers who self-insure to choose self-administration, administration by an insurance company, or administration by an independent TPA varies tremendously according to the type and size of the organization. It is possible to consider these different characteristics as proxies for the employer's general attitude towards changing established procedures, the availability of sufficient qualified personnel to perform the necessary administrative and claims processing functions, the number of employees covered by the plan, and the complexity of employees' medical problems.

Plan administration

A comparison of the prevalence of self-administration among self-insured business establishments, unions, religious organizations, schools, and governments (Table 3) reveals that business establishments and unions are more likely to self-administer. The rate of self-administration is as follows:

Table 3. Percent of self-insured health plans, by type of organization, size, and administrative arrangement: 1984.

| Organization type and size | Self-administered | Outside administered |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Percent | ||

| All types and sizes combined | 23 | 77 |

| Type | ||

| Business establishments | 24 | 76 |

| Unions | 35 | 65 |

| Religious organizations | 27 | 73 |

| Governmental units1 | 6 | 94 |

| Post-secondary schools | 15 | 85 |

| Size2 | ||

| 1-99 | 31 | 69 |

| 100-249 | 7 | 93 |

| 250-999 | 8 | 92 |

| 1,000-4,999 | 16 | 84 |

| 5,000 or more | 28 | 72 |

Governmental units include counties, municipalities, townships, and school districts.

Number of employees.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

24 percent of business establishments.

35 percent of unions.

27 percent of religious organizations.

15 percent of post-secondary institutions.

6 percent of local governments.

Business establishments and unions, both with relatively high rates of self-administration, tend to seek as much control as possible over their operating expenses. In addition, the management of these organizations is oriented towards finding ways to accommodate innovations that hold potential for improving the bottom line. Unions, moreover, are far more accustomed to working with employee benefits than are, for example, schools and governments. The latter groups prefer to assign this responsibility to an outside administrator because they tend not to have personnel who are experienced with handling insurance administration. In addition, these organizations tend to be less concerned with the financial management of their cash flow.

When self-insured business establishments are stratified by size (Table 3), it was surprising to find that small establishments that are self-insured self-administer to a higher degree than do large establishments. Although self-administration is fairly common among very small firms (31 percent of self-insured establishments with 1 to 99 employees), its popularity declines as firm size increases (7 or 8 percent of those with 100 to 999 employees) before increasing again for very large firms (28 percent of those with 5,000 or more employees). A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that, among small firms, claims administration can be handled on a part-time basis and by a small number of people. Outside administration, which often provides claims review, may not be cost effective for small firms because the in-house administrative staff of these plans often know the covered employees well enough to exert cost-consciousness pressure. Also, self-insurance for smaller organizations tends to involve a lesser range of benefits (hospital and/or medical benefits, for example, are often excluded) and is therefore easier to self-administer. For firms that are larger, outside plan administrators can more easily achieve economies of scale than in-house administrators and therefore provide services at a lower cost. Very large firms, however, have sufficient numbers of employees to support their own cost-effective claims administration units.

Finally, the survey permits a comparison of the marketplace for outside administrators, which includes TPA's, Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans, and commercial insurance companies (Table 4). TPA's, which command a 52-percent market share overall,4 account for only 22 percent of the marketplace for organizations with 1,000 or more employees. Commercial insurance companies, and to a lesser extent Blue Cross and Blue Shield, account for an increasingly greater market share as organization size increases.

Table 4. Percent distribution for administrative arrangements of self-insured health plans, by type of organization and size: 1984.

| Organization type and size | Self-administered | Outside administration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Blue Cross and Blue Shield | Hospital Insurance Association of America | Third-party administrator | ||

|

| ||||

| Percent distribution | ||||

| All types and sizes combined | 23 | 6 | 20 | 52 |

| Type | ||||

| Business establishments | 24 | 5 | 20 | 52 |

| Unions | 35 | 2 | 25 | 39 |

| Religious organizations | 27 | 26 | 10 | 37 |

| Governmental units1 | 6 | 13 | 13 | 68 |

| Post-secondary schools | 15 | 19 | 30 | 36 |

| Size2 | ||||

| 1 or more | 23 | 6 | 20 | 52 |

| 100 or more | 10 | 11 | 32 | 50 |

| 250 or more | 13 | 9 | 32 | 49 |

| 1,000 or more | 20 | 20 | 47 | 22 |

| 5,000 or more | 28 | 14 | 46 | 22 |

Governmental units include counties, municipalities, townships, and school districts.

Number of employees of that size or greater that are self-insured.

NOTE: Percents may sum to more than 100, because some plans use more than one administrator.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Among unions, Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans are a distant third (2 percent) to commercial insurance companies and TPA's; among religious organizations, they are a strong second (26 percent).

A. S. Hansen Inc. (1984), employee benefits specialists, conducted a study in 1984 of 861 companies that also asked self-insured plans how they were administered. Hansen found that 13 percent of self-insured plans were self-administered, 23 percent were administered by other than an insurance company, and 62 percent were administered by an insurance company or Blue Cross and Blue Shield plan. These results are comparable to our findings for organizations with 1,000 or more employees. When the results are normalized to sum to 100 percent, we found that, in 1984, 18 percent of self-insured plans within this size category were self-administered, 20 percent were administered by TPA's, and 61 percent were administered by an insurance company or Blue Cross and Blue Shield plan. Overall, the Hansen findings differ from our results for several reasons. We questioned a greater diversity of employer organizations than Hansen, and we weighted our results in order to generalize to the entire universe of employer organizations.

Health maintenance organizations

Health maintenance organizations (HMO's) are organizations of physicians and other health care professionals who provide a wide range of services to subscribers and their dependents on a prepaid basis. Because HMO's accept the risk of providing covered health care services at a cost that does not exceed subscriber rates, they have an economic incentive for monitoring utilization and costs. Various types of HMO arrangements, which differ primarily according to how physicians are affiliated, have been developed in the past several years. They include staff, group, network, and independent physician association arrangements.

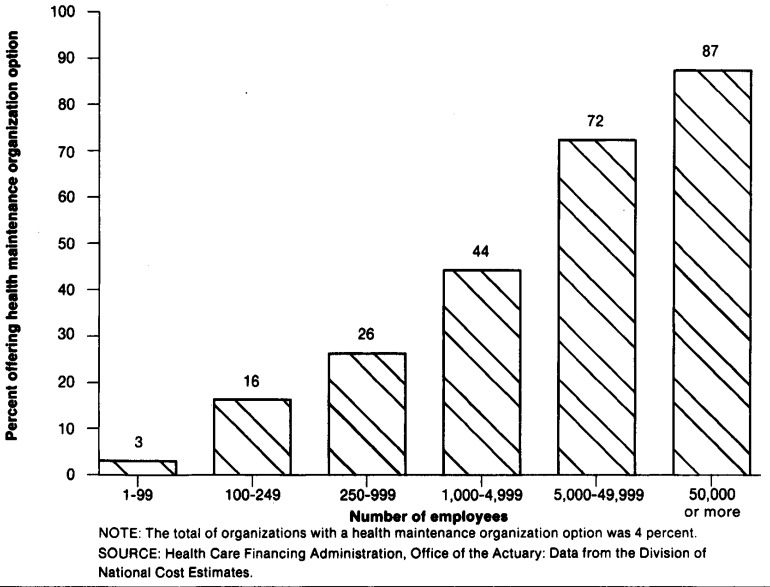

The survey added to our knowledge of changes occurring in the insurance industry by asking all respondents—including both employers who self-insure and those with purchased insurance—whether or not they provide an HMO option. Their responses have allowed us to obtain a more complete perspective of how firms and organizations differ across size and type in their likelihood of offering an HMO option to employees or members. It was found during the survey that an HMO option is offered by 4 percent of all organizations, including 4 percent of business associations, 15 percent of unions, 14 percent of religious organizations, 35 percent of post-secondary schools, and 10 percent of governmental units.

Each of these percents masks the wide variations that occur by group size. For example, as shown in Figure 4, an HMO option is offered by 3 percent of organizations with 1 to 99 employees, 16 percent with 100 to 249 employees, 26 percent with 250 to 999 employees, 44 percent with 1,000 to 4,999 employees, 72 percent with 5,000 to 49,999 employees, and 87 percent with 50,000 or more employees. Variations that occur by organization type and by Standard Industrial Classification are even more apparent as shown by data in Tables 5 and 6.

Figure 4. Percent of organizations that offer a health maintenance organization option, by size: 1984.

Table 5. Number and percent of organizations with health plans that offer a health maintenance organization (HMO) option, by size and type: 1984.

| Type of organization | Number of employees | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Total1 | 1-99 | 100-249 | 250-999 | 1,000-4,999 | 5,000-49,999 | 50,000 or more | |

| Total | 2,341,625 | 2,234,875 | 59,610 | 30,700 | 12,180 | 4,030 | 230 |

| Percent offering HMO option | 4 | 3 | 16 | 26 | 44 | 72 | 87 |

| Business establishments | 2,284,110 | 2,197,000 | 48,600 | 24,300 | 10,500 | 3,530 | 180 |

| Percent offering HMO option | 4 | 3 | 16 | 28 | 47 | 75 | 92 |

| Unions | 3,662 | 620 | 700 | 1,290 | 815 | 220 | 17 |

| Percent offering HMO option | 15 | 17 | 19 | 12 | 14 | 21 | 18 |

| Religious organizations | 780 | 470 | 100 | 110 | 70 | 30 | — |

| Percent offering HMO option | 14 | 5 | 17 | 30 | 38 | 29 | — |

| Governmental units2 | 49,111 | 35,600 | 9,000 | 3,950 | 440 | 115 | 6 |

| Percent offering HMO option | 10 | 8 | 12 | 17 | 25 | 86 | 83 |

| Post-secondary schools | 3,962 | 1,185 | 1,210 | 1,050 | 355 | 135 | 27 |

| Percent offering HMO option | 35 | 18 | 31 | 45 | 58 | 67 | 100 |

Total does not include plans for which organization size is not reported.

Governmental units include counties, municipalities, townships, and school districts.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

Table 6. Number and percent of business establishments with health plans that offer a health maintenance organization (HMO) option, by Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) organization type and size: 1984.

| SIC organization type | Number of employees | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Total | Less than 100 | 100 or more | 1,000 or more1 | |

| Total | ||||

| Number of business establishments2 | 2,284.1 | 2,196.9 | 87.2 | 14.2 |

| Percent offering HMO option | 4 | 3 | 29 | 55 |

| Agriculture, forestry, and fishing | ||||

| Number of business establishments2 | 63.8 | 62.9 | 0.9 | 0.13 |

| Percent offering HMO option | 0.17 | 0.035 | 11 | 17 |

| Mining | ||||

| Number of business establishments2 | 17.4 | 16.0 | 1.4 | 0.26 |

| Percent offering HMO option | 2 | 0.70 | 21 | 58 |

| Construction | ||||

| Number of business establishments2 | 266.7 | 261.5 | 5.2 | 0.39 |

| Percent offering HMO option | 2 | 2 | 16 | 47 |

| Manufacturing | ||||

| Number of business establishments2 | 186.1 | 160.7 | 25.4 | 4.21 |

| Percent offering HMO option | 17 | 14 | 34 | 62 |

| Transportation, communication, and utilities | ||||

| Number of business establishments2 | 66.9 | 62.4 | 4.5 | 1.19 |

| Percent offering HMO option | 7 | 5 | 32 | 58 |

| Wholesale trade | ||||

| Number of business establishments2 | 268.7 | 263.0 | 5.7 | 0.59 |

| Percent offering HMO option | 10.0 | 4.0 | 25 | 51 |

| Retail trade | ||||

| Number of business establishments2 | 515.8 | 503.4 | 12.4 | 2.04 |

| Percent offering HMO option | 2 | 1.5 | 18 | 42 |

| Finance, Insurance, and real estate | ||||

| Number of business establishments2 | 168.3 | 159.2 | 9.1 | 1.77 |

| Percent offering HMO option | 3 | 0.80 | 37 | 68 |

| Services | ||||

| Number of business establishments2 | 730.4 | 707.7 | 22.7 | 3.66 |

| Percent offering HMO option | 4 | 3 | 29 | 49 |

The “1,000 or more” category is included within the “100 or more” category.

The number of business establishments is in thousands.

SOURCE: Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary: Data from the Division of National Cost Estimates.

The extraordinarily low percent of HMO offerings among small firms and organizations, of which there are many, could be a result of the 1973 Health Maintenance Organization Act that requires only employers with 25 or more employees to offer an HMO option if a federally qualified HMO exists in that area. In addition, it does not make good economic or administrative sense for certain small firms or organizations to offer more than one health plan. Among large firms, the HCFA results are consistent with several other studies on the percent of employers offering an HMO option. For example, both Hansen (1984) and Coopers and Lybrand (1984) found that 89 percent of plans with more than 10,000 employees offer an HMO option.

According to InterStudy (1986), a nonprofit health policy research firm, total HMO enrollment increased 25.7 percent from June 1984 to June 1985, the largest growth rate increase in the history of the HMO industry. It is expected that employer and consumer interest in HMO's will continue to increase as businessmen and labor leaders improve their management of HMO's and as hospital administrators and physicians adapt to HMO arrangements. Periodic survey updates should reveal whether or not these expected trends occur.

Conclusions

The 1984 findings presented in this article reveal a high level of self-insurance among large business establishments and unions and among certain industry types. According to insurance industry experts, much of the new activity in self-insurance is taking place among small and medium-sized organizations. This activity is being supported by increased employer acceptance of and adaptability to such innovations as minimum-premium plans, stop-loss coverage, and administrative services only, and by more aggressive marketing on the part of insurance companies and third-party administrators of these options. Insurers are interested in maintaining contact with self-insured employment-related health plans, by charging them for the service of reducing risk or administrative responsibility, so as not to entirely lose the business of establishments that previously purchased health insurance.

As the number of employees and association members covered under self-insured health plans increases, it is likely that State-mandated benefits, as a result of the ERISA exemption, will be offered to fewer plan participants. Proponents view this potential phenomenon negatively because they consider mandated benefits as necessary components of an adequate health plan. We are currently studying this issue to determine the extent to which the benefits provided by self-insured health plans differ from purchased insurance. Among other things, we are examining whether self-insured plans spend less per enrollee than fully insured plans for health benefits, and whether this is a function of efficiency or limiting health benefits. Preliminary data and anecdotal evidence suggests that employees covered by self-insured health plans have less generous medical, surgical, and other benefits, and they are less likely to be offered continuation coverage should they retire, become unemployed, or become disabled.

Other observers point out that the exemption from mandated benefits may encourage more employers to provide health benefits for their employees because the health plan need not be as extensive and therefore not as expensive. A 1985 study by the Federation of Independent Businesses (Business Insurance, 1986) found that 27 percent of small business owners who did not provide health insurance to all full-time employees felt that premiums were too high. Furthermore, employers who self-insure are better able to tailor their health plans to their particular employees' needs. The end result is that employers, by switching to self-insurance, encourage traditional insurers to become more competitive in their rates and practices, thereby leading to a decline in the cost of employer-provided health insurance. The Employee Benefit Research Institute (1984) found that employer contributions in 1984 for health care—which includes premiums paid to insurers and medical claims payments by self-insured employers—equaled 2.57 percent of the gross national product, down from 2.63 percent in 1983. This decline might, however, be attributable to other factors.

Many employers will continue to choose purchased insurance plans over self-insurance. Small employers especially need its risk-pooling and prospective-budgeting aspects. Employers with purchased insurance generally are concerned about assuming administrative responsibility, the financial dangers of self-funding, and potentially unfavorable employee response. Additionally, employers with purchased insurance may object to nondiscrimination rules that they must adhere to if they become self-insured. These rules, set forth by the Internal Revenue Service, state that health benefits shall not be greater for management than for rank and file employees, nor should management personnel have a greater opportunity to participate.5 Finally, if the Federal Government continues to enact legislation that requires similar regulatory treatment for purchased insurance and self-insured plans, thereby negating the advantages of the ERISA exemption, employers may become discouraged from switching over to self-insurance. For example, since August 1986, the Federal Government has required that all businesses with more than 20 employees offer continuation coverage for terminated employees, widows, spouses, and dependents. Additional bills under consideration by Congress would require all employers, including those who purchase insurance and those who self-insure, to offer a wide range of extra benefits, and encourage States to establish risk pools for uninsured people. Legislative staffs are also starting to investigate the need for limiting unfunded liabilities of self-insured health plans.

Further research

This study provides the most comprehensive data on the topic of self-insurance collected to date. It is based on a larger, more diverse sample of employers, weighted to represent the entire universe, than any previous study of self-insurance. Our future work will build on the statistics presented in this article in several ways. We will be evaluating trend data on the growth of self-insurance and comparing in greater detail the differences in benefit provision of purchased and self-insured plans. We will also look at the prevalence of minimum-premium plans, stop-loss agreements, and administrative-service agreements. Most importantly, additional analysis will allow us to determine the number of persons who are covered by self-insured health plans and the size of their health benefits. Knowing this, we should be able to reestimate the share of personal health expenditures paid by self-insured health plans and purchased insurance.

Technical note

The study

Historically, a census of the known universe of independent health plans has been conducted every 4 to 6 years by the Division of National Cost Estimates, Health Care Financing Administration, and its predecessor organizations in the Social Security Administration. Independent health plans are either prepaid (including single service) or self-insured. In the past, the approach taken toward identifying these plans has been to contact organizations of two basic types: those who might know of or be affiliated with prepaid, single-service or self-insured plans (resource organizations) and those that are actually known to sponsor such a plan (sponsoring organizations). Westat Inc. (1978) contacted approximately 607 resource organizations and 1,912 sponsoring organizations, which resulted in the identification of approximately 4,850 plans to whom screeners were then sent to determine their eligibility for inclusion in the universe. In all, a total of 1,799 health plans were identified that met the criteria for being either prepaid or self-insured in 1977. Of these, 1,519 were considered to be self-insured plans, and 280 were considered to be prepaid plans.

Since 1977, the nature of private health insurance in the United States has changed considerably. Within the category of prepaid plans, those that are HMO's have remained relatively easy to identify: The Office of Health Maintenance Organizations, HCFA, publishes a yearly census. Although the universe of single-service plans is more difficult to identify, State insurance commissioners and professional associations (i.e., the American Dental Association) are generally able to provide the names of many of these organizations. With the actual universe being small, it is relatively easy to survey the entire population of known prepaid plans.

The number of self-insured plans has, however, increased so dramatically that past methods of estimating the universe can no longer be applied. Although it might be possible through a massive mailing to identify a large number of organizations that are self-insured, there could be no assurance that the full universe had been reached nor could there be any way of estimating the ratio that these organizations bore to the full universe.

For this reason, the latest survey of self-insured plans, conducted by HCFA in conjunction with Mandex, Inc.,6 was based on a probability sample. Using a variety of sampling frames, screener questionnaires were mailed to a stratified random sample of 28,439 employers, unions, associations, religious organizations, governmental units, and schools. Organizations chosen to receive the screener questionnaires were drawn from four nationwide sampling frames: ERISA-reported welfare plans from the Department of Labor; Dun and Bradstreet files from Dun's Marketing Service; the Census of Government file from the U.S. Bureau of the Census; and a listing of post-secondary educational institutions from the Council on Post-Secondary Accreditation. In addition to the aforementioned data bases, the names of 149 national unions that could not be located in the ERISA file were added. This brought the total number of screeners mailed to 28,588.

Of the 28,588 screeners mailed, 2,292 were ultimately found to be undeliverable or no longer active. Another 1,454 questionnaires were found to be duplicates. Of the remaining 24,842, there were more than 16,000 usable replies for an overall response rate of 65 percent. The response rate for the replies from the individual data bases were as follows: Dun and Bradstreet, 65 percent; ERISA, 62 percent; Census, 75 percent; and post-secondary schools, 56 percent.

Each unit in the sample was asked what type of organization it represented, the number of employees, and whether or not it had sponsored a health plan in 1984 that was fully or partially self-insured. Respondents who stated they were self-insured were in turn asked to identify the type or types of coverage involved, including hospital and medical, dental and vision, disability, accidental death, and dismemberment,7 or other, and the organization responsible for processing claims and other administrative functions, including self-administered or other-administered. In addition, all respondents were asked if they provided any of the following: an HMO option; an on-site health unit or infirmary with one or more holding beds, staffed by a doctor or nurse; free or subsidized health care, other than insurance, provided through contract or other arrangement with one or more provider organizations; or a cafeteria plan.8

Sampling methodology

Different sampling techniques were employed for each of the four data bases. Size stratifications were consistent to all four and comprised 1 to 49, 50 to 99, 100 to 249, 250 to 999, 1,000 to 4,999, 5,000 to 19,999, 20,000 to 49,999, and 50,000 or more employees. In addition, both the ERISA and Dun and Bradstreet data bases were stratified by a business code that followed a two-digit SIC classification. The classifications were the following:

01-09—Agriculture, forestry, and fisheries.

10-14—Mining.

15-17—Contract and construction.

20-39—Manufacturing.

40-49—Transportation, communication, and utilities.

50-51—Wholesale trade.

52-59—Retail trade.

60-69—Finance, insurance, and real estate.

70-89—Services.

90-99—Public administration and tax-exempt organizations.

A brief description of the various data bases and sampling frames follows.

Employee Retirement Income Security Act

Employers and multiple-employer trusts (e.g., unions) must file information relevant to the issue of private health insurance, on Form 5500, under the provisions of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). SysteMetrics, subcontractor to Mandex, Inc., produced a reduced ERISA file consisting of selected information drawn from all benefit plan reports filed between 1977 and 1982. Data elements included were Administrator's employer identification number (EIN) (primary sort); plan number (secondary sort); plan year (tertiary sort); employer name, street address, city, State, and Zip Code; name of plan; sponsor's EIN;9 sponsor's business code; number of active, retired, and separated participants; and funding arrangements.

The file initially contained over 200,000 records that were stripped from the millions of records in the original Department of Labor file, so that only pension or welfare plans that included health insurance remained. The file was then further reduced by unduplicating all records that carried identical EIN's and retaining only the latest record. Records based on Form 5500-G (filed by only government or religious or nonprofit entities) were also retained because any of these groups might sponsor self- or fully-insured health plans.

A classification code was then assigned to each record in the file as follows: employer (E), association (A), union (U), multiple-employer trust other than union (M), schools (S), church or religious organizations (C), and governmental unit (G). Because the sponsor's business code carried in ERISA could not be relied on for purposes of classification,10 the classification process applied was carried out manually through visual examination of an output listing by organizational name and address.

The result of these efforts was a file containing 44,581 plans. Of these, 6,143 governmental units were excluded because they were identified alternatively from the Census file, and 699 schools were excluded because they were identified alternatively from a listing of post-secondary educational institutions. The remaining 37,491 employer, associations, unions, and religious organization plans were stratified on the basis of size and, when appropriate, business code (SIC).

For employers and associations, all classifications with 400 records or more received a sample size of 200, and those with less than 400 were sampled with certainty. Because of the smaller numbers involved, unions were sampled with certainty below 750 records, and those with more than 750 records received a sample of 250. Multiple-employer trusts and churches were sampled with certainty.

The specific records selected for inclusion in the sample were again scanned for duplicates, and the number of ERISA mailings was reduced to 14,192, slightly under 40 percent of the available file.

Dun and Bradstreet

To supplement the ERISA file, a second major source of names was purchased from Dun's Marketing Services. Dun's maintains a directory of firms included in the Dun and Bradstreet national data base. Each firm is identified by name and address, telephone number, SIC, number of employees (total and by establishment), and annual sales volume. Because of economic considerations,11 a different sampling frame was adopted for Dun and Bradstreet. Organizations with 5,000 or more employees were sampled with certainty. All organizations with less than 5,000 employees were divided into three clusters—small, medium, and large—depending on the number of organizations in each cell. Each cluster was then assigned a sampling rate designed to yield a total of 150 to 350 names per cell.12 The sampling rates resulted in a sample of 12,504 organizational names.

Census

The 1982 Census of Government Name and Address File was found to contain 53,889 governmental units. These were divided into county, municipality, township, and school district. Units greater than 30,00013 were sampled with certainty, and those with less than 30,000 had a sample size of 50, for a total of 2,562 governmental units surveyed.

Schools

The Council on Post-Secondary Accreditation provided a list of 4,229 colleges, community colleges, and universities in the form of mailing labels with no stratification by size or other variable. A sampling rate of 1 in 5 was applied, resulting in a sample size of 850 schools.

Examination of the four data bases disclosed an additional 1,690 plans that were in both ERISA and Dun and Bradstreet. Elimination of these duplicates reduced the total number of mailed screeners from more than 30,000 to 28,588.

Statistical weights

This survey used statistical weights as a means to account for the fact that not all cells were sampled with equal probability and not all cells yielded the same response rate. Consequently, each cell in the screener sample is characterized by two weights. W1 represents the sampling weight, and W2 represents the response weight. W1 is the reciprocal of the sampling rate applied to any particular cell, and W2 assigns to the organizations that did not respond the “average” properties of the organizations that did respond for any particular cell. W2 equals the number of useful responses plus the number of nonresponses over the number of useful responses. Excluded from the weighting were plans found to be duplicates or subsidiaries and plans classified as undeliverables.14

As in all weighting processes, there remain some possible biases. For example, although every attempt was made to reach the undeliverables, they may still have been in existence. In addition, many new companies may have come into existence between the sample selection and the actual mailing. The data bases may be missing some organizations, in particular the smaller ones. This may have created some downward bias. In the direction of upward bias, however, all of the data bases contained a number of organizations that were listed more than once. Although every attempt was made to eliminate this duplication, some still remained.

In addition to the sampling frame biases, two examples of response bias emerged. The initial nationwide projections were considerably larger than expected for organizations with small numbers of employees, in particular, those with less than 100 employees. To investigate the possibility that the nonrespondents to the screener document differed significantly from the respondents, a series of randomly sampled telephone calls were made. The groups sampled were screener respondents who had indicated that they were self-insured, screener respondents who indicated that they were not self-insured, and screener nonrespondents. A total of 870 calls were made that provided the evidence that, although there was no response bias among the companies within the 50-99 size category, some bias did exist within the 1-49 cell.

Several conclusions were reached. Within the 1-49 size category, nonrespondents had fewer employees than respondents, were less likely to self-insure than respondents, and they were less likely to have a health plan of any form. Because of these findings, the response weight for W2 needed to be adjusted. This was accomplished by dividing the 1-49 cell into four substrata (1-4, 5-9, 10-19, and 20-49) and two response categories (self-insured, and nonself-insured). For each separate substratum and each response category, the ratio of respondents to nonrespondents was estimated, and a weight based on that ratio was calculated.

The second response bias resulted from plans that had initially reported themselves to be self-insured and self-administered and were in actuality outside administered or not self-insured. A series of random telephone calls were made and, based on these observations, a series of adjustment factors designed to account for the error rates were developed and applied.

After the weighting was completed for all four data bases, the results were post-stratified by their actual reported size. Aggregate totals were then computed consistently over all data bases.

Acknowledgments

The authors particularly want to thank Joel Todd, senior analyst of Mandex, Inc., and Rose Chu, senior analyst of Actuarial Research Corporation. We also wish to thank Gordon Trapnell, President, Actuarial Research Corporation, for providing actuarial and health industry expertise. Clark Miller and Leo Marcus, both of Mandex, provided instrumental computer programming assistance. Frederick Hunt of the Society of Professional Benefit Administrators deserves special mention for providing many helpful suggestions. Jim Beebe of the Office of Research and Statistics provided valuable statistical consultation. The authors wish to give special thanks to Frank Eppig of the Division of National Cost Estimate staff for his survey design expertise and computer assistance. The authors are grateful to George I. Kowalczyk, George Chulis, Mark Freeland, Katie Levit, Larry Schmid, Nate Singer, Dave Skellan, Sally Sonnefield, and Daniel R. Waldo, all of the Division of National Cost Estimates, and Charlie Fisher, Dave McKusick, and Roland King for their many constructive comments on the article. The authors are also grateful to Frances Inman and Eileen Rollman of Mandex, Nancy Smythe of Actuarial Research Corporation and Carol Pearson of the Division of National Cost Estimates for all their administrative assistance. Any errors or omissions are of course strictly the responsibility of the authors.

Footnotes

Reprint requests: Carol Pearson, L1, 1705 Equitable Building, 6325 Security Boulevard, Baltimore, Maryland 21207.

The distinction between purchased insurance and self-insurance is set forth in case law interpreting the McCarran-Ferguson Act of 1948.

Because of the survey characteristics, “governments” refer to townships, counties, municipalities, and school districts. Data on State and Federal governments were obtained separately.

Dun and Bradstreet maintains a complete directory of business establishments, both with health plans and without health plans, in their national data base. Among the 5.4 million firms listed in the directory in 1984, 4,905,600 have 1 to 99 employees, 60,967 have 100 to 249 employees, 29,192 have 250-999 employees, 8,308 have 1,000 to 4,999 employees, 1,948 have 5,000 to 49,999 employees, and 159 have 50,000 or more employees.

Market shares are expressed here as a percent of plans administered. Because TPA's tend to administer smaller plans, they command a smaller market share in terms of dollars.

Beginning in 1989, nondiscrimination rules will be equally applied to all self-insured and purchased health plans. Those who do not comply will face Federal penalties.

Mandex, Inc., subcontracted to the Actuarial Research Corporation for technical expertise in the private health insurance industry.

Disability, accidental death, and dismemberment, although not health benefits, were included as a safeguard. However, organizations that stated they were self-insured but checked this box were excluded from the count of independent health plans.

A cafeteria plan enables an employee to choose from alternate benefits such as more comprehensive insurance, extra disability insurance, and extra vacation days.

Will be identical to the employer EIN unless the sponsor is a subsidiary or parent company.

Professional and other business groups were often assigned the code classification of their industry rather than coded as membership organizations.

The cost of purchasing a sample from Dun's Marketing is a function of the number of separate sampling rates specified.

A table containing the actual sample rates is available upon request from the authors.

Refers to population in the case of governments, enrolled in the case of school districts.

Undeliverables were those plans whose addresses were determined by the Postal Service as nonexistent and could not be located through the use of telephone directory assistance.

References

- Arnett RH, Trapnell GR. Health Care Financing Review. No. 2. Vol. 6. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Dec. 1984. Private health insurance: New measures of a complex and changing industry. HCFA Pub. No. 03195. Office of Research and Demonstrations, Health Care Financing Administration. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self-insurance. Business Insurance. 1986 Jan.20(4) [Google Scholar]

- Coopers and Lybrand. Employee Medical Plan Costs … A Comparative Study. Dallas, Tex.: 1984. Annual Report. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin C. Self-insured employers face legislative scrutiny on ERISA immunity. Business and Health. 1986 Oct.3(61) [Google Scholar]

- Egdahl RD, Walsh DC. Containing Health Benefit Costs: The Self-Insurance Option. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Employee Benefit Research Institute. Fundamentals of Employee Benefit Programs. Washington: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- A. S. Hansen Inc. Employee Benefits, Survey Results. Lake Bluff, Ill.: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Harker C. Self-Funding of Welfare Benefits. Wisconsin: International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Health Policy Project. Focus on ERISA and the States. Washington: Mar. 1986. [Google Scholar]

- InterStudy: Press releases. Excelsior, Minn.: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Markus G. Self-Insured Health Benefits — Trends and Issues. 1981 Apr. Report No. 81-100EPW. Congressional Research Service. [Google Scholar]

- Mandat RA. Self-Insurance. 1985 Tillinghast Health Care Monographs. [Google Scholar]

- Mandex, Inc. Independent Health Plan Survey, Methodological Report. 1985 Oct. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Service. 10th Annual Report to the Congress, Fiscal Year 1984. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Jun, 1985. Office of Health Maintenance Organizations. [Google Scholar]

- Moore CD. A Profile of Leading Third Party Administrators. Lexington, Mass.: Temple, Barker, and Sloane, Inc.; Mar. 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Westat Inc. Report Documenting the Procedures Used to Contact Resource Organizations and Identified Plans for The Nationwide Survey of Independent Prepaid and Self-Insured Health Plans. Rockville, Md.: Sept. 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt Company. 1984 Group Benefits Survey. Washington, D.C.: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt Company. 1986 Group Benefits Survey. Washington, D.C.: 1986. [Google Scholar]