Abstract

Chloroplasts have been reported to generate retrograde immune signals that activate defense gene expression in the nucleus. However, the roles of light and photosynthesis in plant immunity remain largely elusive. In this study, we evaluated the effects of light on the expression of defense genes induced by flg22, a peptide derived from bacterial flagellins which acts as a potent elicitor in plants. Whole-transcriptome analysis of flg22-treated Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings under light and dark conditions for 30 min revealed that a number of (30%) genes strongly induced by flg22 (>4.0) require light for their rapid expression, whereas flg22-repressed genes include a significant number of genes that are down-regulated by light. Furthermore, light is responsible for the flg22-induced accumulation of salicylic acid (SA), indicating that light is indispensable for basal defense responses in plants. To elucidate the role of photosynthesis in defense, we further examined flg22-induced defense gene expression in the presence of specific inhibitors of photosynthetic electron transport: 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea (DCMU) and 2,5-dibromo-3-methyl-6-isopropyl-benzoquinone (DBMIB). Light-dependent expression of defense genes was largely suppressed by DBMIB, but only partially suppressed by DCMU. These findings suggest that photosynthetic electron flow plays a role in controlling the light-dependent expression of flg22-inducible defense genes.

Keywords: photosynthesis, flg22, defense gene, DBMIB, DCMU, retrograde signaling, salicylic acid, CAS

Introduction

Over the course of their evolution, plants have developed defense systems against a broad-spectrum of pathogens. Plant cells recognize pathogens through pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) that recognize common features of microbial pathogens, termed pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). The recognition of PAMPs by PRRs rapidly initiates downstream signaling events that result in the activation of an array of basal defense responses (PAMP-triggered immunity, PTI; Chisholm et al., 2006; Göhre and Robatzek, 2008). Furthermore, effector-triggered immunity (ETI) induces cell death at infection sites to enclose the spread of pathogens, a process also known as the hypersensitive reaction (HR). Plant immunity activates signal transduction pathways such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphorylation cascades, and Ca2+ and reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling pathways, which lead to transcriptional reprogramming and defense responses, including the accumulation of salicylic acid (SA), a critical signaling molecule in plant immunity. There are two distinct pathways that produce SA from chorismate in plants: the isochorismate (ICS) pathway in chloroplasts and the phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) pathway in the cytoplasm. Recently, it was demonstrated that SA is synthesized in chloroplasts via the ICS pathway, but not in the cytoplasm, in Arabidopsis (Fragnière et al., 2011).

PAMPs induce the expression of a specific set of defense genes, a process that is mediated by transcription factors (TFs) such as WRKYs (Rushton et al., 2010; Ishihama et al., 2011). A subset of genes activated by PAMPs is also induced by abiotic stresses such as temperature and drought. Furthermore, plant immune responses are modulated by circadian rhythms as well as abiotic stresses, including light and temperature (Hua, 2013). These facts suggest the presence of crosstalk between biotic and abiotic stress signaling pathways (Fujita et al., 2006).

Light is a fundamental factor in the control of many important biological processes during plant development and environmental responses. There is increasing evidence that light is also required for the appropriate induction of plant defense responses against pathogens (Roberts and Paul, 2006; Kangasjärvi et al., 2012). Zeier et al. (2004) demonstrated that light is responsible for accumulating SA and suppressing bacterial growth. Furthermore, several studies have shown that specific photoreceptors are involved in the regulation of plant immune responses (Griebel and Zeier, 2008; Jeong et al., 2010; Wu and Yang, 2010; Cerrudo et al., 2012). Chloroplasts may also be involved in the light-mediated control of plant immune responses. Göhre et al. (2012) reported that the flg22 peptide derived from bacterial flagellins induces down-regulation of the non-photochemical quenching of excess excitation energy (NPQ) in chloroplasts, suggesting a role for chloroplasts in plant immunity. In fact, it was recently demonstrated that the perception of PAMPs generates a transient Ca2+ increase in the chloroplast stroma within a few minuetes (Manzoor et al., 2012; Nomura et al., 2012). These findings suggest that PAMP signals are rapidly relayed to chloroplasts in the early stage of a plant's immune response, and support the idea that chloroplasts mediate light-dependent defense responses against infection by pathogens (Nomura et al., 2012).

Light is not only the energy source for carbon assimilation in chloroplasts, but also an important regulatory factor for chloroplast functions, such as carbon metabolism and other metabolic processes, as well as the expression of chloroplast-encoded genes. In chloroplasts, ROS are unavoidably generated with photosynthetic electron flow, which is driven by light. Singlet oxygen (1O2) is generated around photosystem II (PS II), and the superoxide anion radical (O−2) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) are generated around photosystem I (PS I). The 1O2 and H2O2 that are photo-produced in the chloroplast mediate retrograde signals to regulate the expression of nuclear-encoded defense genes (Kim et al., 2012; Kangasjärvi et al., 2013; Karpiński et al., 2013; Szechyńska-Hebda and Karpiński, 2013 and the hypersensitive response (Jelenska et al., 2007). CAS has been identified as a thylakoid membrane-localized Ca2+-binding protein that regulates cytoplasmic Ca2+ signals and stomatal closure (Han et al., 2003; Nomura et al., 2008; Vainonen et al., 2008; Weinl et al., 2008). We previously reported that CAS may play a role in the 1O2-mediated retrograde signaling for defense responses (Nomura et al., 2012). Based on our findings, we inferred that CAS is involved in the flg22-induced Ca2+ elevation in chloroplasts and in retrograde signaling from the chloroplast to nucleus to control the expression of nuclear-encoded defense genes, including SA biosynthesis genes. Excess light has been shown to activate defense-related genes, possibly through redox changes of the plastoquinone (PQ) pool (Mühlenbock et al., 2008). Furthermore, it has been suggested that the photosynthetic electron transport chain is involved in plant immune (Mateo et al., 2006; Mühlenbock et al., 2008) and stress (Jung et al., 2013) responses. However, the exact role of photosynthesis in the regulation of plant immunity remains unknown.

A large proportion of the biochemical reactions and molecular regulations occurring in chloroplasts is influenced by light. Thus, we predicted that flg22-induced defense gene expression may also be light-dependent. To elucidate the role of light and photosynthesis in flg22-induced defense gene expression, we examined the effects of light/dark conditions and photosynthesis inhibitors on the flg22-regulated expression of nuclear-encoded defense genes. We found that photosynthetic electron flow plays a key role in controlling the light-dependent expression of flg22-inducible defense genes.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana wild-type (WT) Columbia ecotype was used in this study. Sterilized Arabidopsis seeds were germinated on solid agar medium consisting of 0.8% (w/v) plant tissue culture grade agar supplemented with 0.5 × Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (Wako Chem. Co., Osaka, Japan) and grown at 22°C with 16 h light (80–100 μmol m−2 s−1)/8 h dark cycles for 2 weeks. To avoid mechanical stress when plants were treated with flg22, 2-weeks-old WT plants were floated on 0.5 × strength MS medium for 24 h before flg22 treatment. The dark plants were pre-incubated in the dark for 24 h, while the light plants were illuminated for 4 h before flg22 treatment. Both plants were treated with 1 μM flg22 for 30 min in the dark or light (80–100 μmol m−2 s−1). For treatment with photosynthesis inhibitors, plants were incubated with 5 μM 2,5-dibromo-3-methyl-6-isopropyl-benzoquinone (DBMIB) or 8 μM 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea (DCMU) for 30 min prior to flg22 treatment (1 μM). The flg22 peptide was purchased from BIOLOGICA Co. (Nagoya, Japan). DBMIB and DCMU were purchased from Wako Chem. Co. (Osaka, Japan).

Microarray experiments

The genome-wide microarray analyses were performed using the Arabidopsis V4 2 color microarray (Agilent Technologies). Total RNA was isolated from plants treated with flg22 in the light or dark for 30 min using the Qiagen RNeasy Plant Mini kit following the manufacturer's instructions. Each 200-ng total RNA sample was used to prepare Cy3- or Cy5-labeled target cRNA with the Low Input Quick Amp Labeling Kit (Agilent Technologies, USA) and used in dual color microarray hybridization with the Agilent Arabidopsis v4 oligo microarray slide. A dye-swap experiment was performed with two different RNA populations to eliminate the signal variation caused by the differential labeling efficiency of Cy3 and Cy5 dyes using the SuperScan microarray scanner (Agilent Technologies, USA). The microarray data were normalized by the LOWESS method using Feature Extraction software v. 10.7 (Agilent Technologies) and the expression ratios were analyzed (Non-Uniformity Outlier and Feature Population Outlier). Data with a P-value of >0.01 were eliminated. The genes showing a consistent expression pattern in the light or dark (>2.0 difference) are listed in sData 1.

Microarray data analysis

The genes induced by flg22 for 30 min (Lyons et al., 2013; http://www.nature.com/srep/2013/131009/srep02866/full/srep02866.html#supplementary-information) and by illumination of the flu mutant (Laloi et al., 2007) were obtained from the indicated publications. Light-responsive genes in the absence of flg22 were obtained from a public database (Michael et al., 2008; http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/experiments/E-MEXP-1304/). Gene ontology and MapMan analysis were performed with the Arabidopsis Classification SuperViewer at the BAR of the University of Toronto (http://bar.utoronto.ca/ntools/cgi-bin/ntools_classification_superviewer.cgi). We compared the gene expression profiles from our microarray experiments with available expression data via the expression browser at the BAR. We also searched for overrepresented cis-elements in the 500-bp upstream regions of the down- and up-regulated genes in flg22-treated cas-1 plants using the Regulatory Sequence Analysis tool (RSAT; http://rsat.ulb.ac.be/rsat/).

qRT-PCR experiments

Plants were grown and treated with flg22 and photosynthesis inhibitors as described above in Section Plant Materials and Growth Conditions. RNA was extracted from the leaves using the RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen, USA) and cDNA was generated using SuperScript III (Invitrogen, USA). The Ct values were determined using an iCycler (Bio-Rad, USA) and analyzed with CFX Manager (Bio-Rad, USA). Primers used for qRT-PCR analyses are listed in sTable 1. Expression levels of UBQ10 were constant under flg22 treatments. At least three independent biological replicates were performed for each sample and control. Representative results are shown as the mean ± s.e.m. of at least three technical experiments.

SA analysis by LC/MS

SA was measured using a conventional high-performance liquid chromatography system. A total of 200 mg of seedling samples without roots was homogenized and extracted with 100% methanol containing the internal standard anisic acid. Free and glycosylated SA were separated and analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) (3200QTRAP, AB SCIEX, USA) with a modification of the methods described in Nomura et al. (2012).

Results

Light-dependent expression of flg22-induced defense genes

To identify genes rapidly responsive to flg22 whose expression is controlled by light, we performed microarray analysis of light- and dark-dependent gene expression in Arabidopsis seedlings treated with flg22 for 30 min. In flg22-treated plants, expressions of 3192 and 2860 genes significantly increased and decreased (more than two-fold), respectively, in the light compared to the dark control (sData 1). Under our experimental conditions, plants were illuminated for 4 h before flg22 treatment, whereas dark control plants were kept in the dark. Thus, in order to exclude light-responsive gene sets that are not regulated by flg22, we identified genes that are induced (1612 genes, >2.0) or repressed (1496 genes, <0.5) by 4 h illumination in the absence of flg22 from the public database (Michael et al., 2008). As a result, 616 of 1612 light-induced genes and 699 of 1496 light-repressed genes overlap with the light-dependent and -repressed genes identified in the flg22-treated plants based on our microarray data, respectively. Thus, we removed these genes from our microarray data, and obtained 2576 light-dependent genes and 2161 light-repressed genes in plants treated with flg22 for 30 min. The resultant datasets were used for further analyses.

In order to focus on genes that are rapidly regulated by flg22 in a light-dependent manner, we compared the light-dependent and -repressed genes described above with genes rapidly responsive to flg22 that were identified by Lyons et al. (2013). They showed that flg22 induced the expression of 3579 genes within 30 min (>2.0), whereas it repressed the expression of 4159 genes (<0.5) (Lyons et al., 2013). We identified a large number of genes that are induced by flg22 in a light-dependent manner (sData 2); 536 (14.9%) of 3579 flg22-induced genes overlapped significantly with the light-dependent genes (named flg22-induced light-dependent genes), but less with light-repressed genes [239 (6.7%) genes, named flg22-induced light-repressed genes] (Table 1). We further named the genes that are induced by flg22 but light-insensitive as flg22-induced light-independent genes. As shown in Table 2, the top 25 flg22-induced genes include a large number of light-dependent genes, but not flg22-repressed genes. These results suggest that light is a critical signal for the activation of defense gene expression. Gene ontology analysis revealed that stress-responsive and signal transduction-related genes were overrepresented among the flg22-induced light-dependent genes, but not in the flg22-induced light-repressed genes (sFigure 1). Furthermore, MapMan analysis revealed that functional categories related to stress, signaling, hormone metabolism, and tetrapyrrole synthesis were significantly enriched in the flg22-induced light-dependent genes (sTable 2). It should be noted that the light-induced genes include a number of genes involved in SA biosynthesis, such as EDS1, PAD4, SAG101, EDS5, and PAL1, but include fewer TF-related genes compared with the light-independent genes.

Table 1.

The number of genes up- and down-regulated by flg22 and light.

| Flg22-responsive genes* | Light-responsive genes** | Overlap genes | P-value*** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flg22-induced light-dependent genes | 3579 | (flg22-up) | 2576 | (light-dependent) | 536 | 8.790e-24 |

| Flg22-induced light-repressed genes | 3579 | (flg22-up) | 2161 | (light-repressed) | 239 | 1.084e-05 |

| Flg22-repressed light-dependent genes | 4159 | (flg22-down) | 2576 | (light-dependent) | 359 | 2.599e-04 |

| Flg22-repressed light-repressed genes | 4159 | (flg22-down) | 2161 | (light-repressed) | 370 | 0.15 |

The light-dependent and -repressed genes identified in this study (**) were compared with flg22 rapidly responsive genes identified by Lyons et al. (2013) (*). P-value (

) was calculated using the hypergeometric probability formula.

Table 2.

Top 25 genes induced and repressed by flg22 in 30 min.

| AGI code | Description | flg22-up* fold change | Light-up** fold change |

|---|---|---|---|

| flg22-INDUCED GENES WITHIN 30 MIN | |||

| AT5G24110 | WRKY30;_transcription_factor | 604.357 | 4.08 |

| AT1G06135 | similar_to_unknown_protein_(TAIR:AT2G31345.1) | 229.879 | 2.32 |

| AT3G02840 | immediate_early_fungal_elicitor_family_protein | 220.241 | – |

| AT4G14450 | Identical_to_Uncharacterized_protein_At4g14450 | 206.208 | – |

| AT1G22810 | AP2_domain-containing_transcription_factor,_putative | 179.432 | – |

| ATIG19210 | AP2_domain-containing_transcription_factor,_putative | 175.500 | – |

| AT5G47850 | protein_kinase,_putative | 172.464 | 2.25 |

| AT2G31345 | similar_to_unknown_protein_(TAIR:AT1G06135.1) | 164.362 | – |

| AT3G12910 | transcription_factor | 153.511 | 3.08 |

| AT1G06137 | similar_to_unknown_protein_(TAIR:AT1G06135.1) | 150.495 | – |

| AT2G37430 | zinc_finger_(C2H2_type)_family_protein_(ZAT11) | 149.453 | 3.22 |

| AT1G72520 | lipoxygenase,_putative | 134.598 | 2.79 |

| AT5G11140 | similar_to_unknown_protein_(TAIR:AT4G38560.1) | 130.349 | – |

| AT4G18540 | similar_to_unknown_protein_product_(GB:CAO48082.1) | 129.095 | 4.79 |

| ATIG07160 | protein_phosphatase_2C,_putative | 114.130 | 2.85 |

| ATIG56240 | ATPP2-B13_(Phloem_protein_2-B13) | 106.016 | 4.08 |

| AT5G64905 | PROPEP3_(Elicitor_peptide_3_precursor) | 96.240 | 2.2 |

| AT1G56250 | ATPP2-BI4_(Phloem_protein_2-BI4) | 93.958 | 4.98 |

| AT4G34410 | AP2_domain-containing_transcription_factor,_putative | 93.865 | – |

| AT4G31950 | CYP82C3_(cytochrome_P450) | 93.089 | 6.73 |

| AT5G05300 | similar_to_unknown_protein_(TAIR:AT3G10930.1) | 85.834 | 2.16 |

| AT4G11470 | protein_kinase_family_protein | 83.563 | 3.75 |

| AT4G11070 | WRKY41;_transcription_factor | 80.292 | – |

| AT4G19520 | disease_resistance_protein_(TIR-NBS-LRR_class) | 80.044 | 2.16 |

| AT5G42380 | CML37/CML39;_calcium_ion_binding | 71.672 | 3.03 |

| flg22-REPRESSED GENES WITHIN 30 MIN | |||

| AT3G42550 | aspartyl_protease_family_protein | 0.009 | – |

| AT5G06500 | AGL96;_DNA_binding_/_transcription_factor | 0.015 | – |

| AT2G05350 | unknown_protein | 0.020 | – |

| AT4G05095 | similar_to_unknown_protein (TAIR:AT4G04650.1) | 0.022 | – |

| AT4G30074 | LCR19_(Low-molecular-weight_cysteine-rich_19) | 0.025 | – |

| AT5G59310 | LTP4_(LIPID_TRANSFER_PROTEIN_4);_libid_bin | 0.025 | – |

| AT1G60500 | dynamic_family_protein | 0.027 | – |

| AT5G24440 | CID13_(CTC-Interacting_Domain_13);_RNA_bindir | 0.028 | – |

| AT3G42060 | myosin_heavy_chain-related | 0.031 | – |

| AT1G66855 | similar_to_glycosyl_hydrolase_family_protein_17 | 0.032 | – |

| AT4G05071 | unknown_protein | 0.035 | – |

| AT4G28170 | similar_to_unknown_protein (TAIR:AT1G11120.1) | 0.036 | – |

| AT1G54775 | Encodes_a_Plant_thionin_family_protein | 0.040 | – |

| AT5G33390 | glycine-rich_protein | 0.044 | – |

| AT5G42957 | similar_to_unknown_protein (TAIR:AT5G42955.1) | 0.047 | – |

| AT1G27990 | similar_to_unknown_protein (TAIR:AT5G52420.1) | 0.050 | – |

| AT3G44755 | similar_to_unknown_protein (TAIR:AT3G46360.1) | 0.051 | – |

| AT4G29200 | beta_galactosidase | 0.052 | – |

| AT2G15590 | similar_to_unknown_protein (TAIR:AT4G33985.1) | 0.056 | – |

| AT5G28560 | unknown_protein | 0.060 | – |

| AT4G27415 | unknown_protein | 0.061 | – |

| AT1G34280 | unknown_protein | 0.063 | – |

| AT3G59460 | similar_to_F-box_family_protein_(TAIR:AT3G6004) | 0.068 | – |

| AT1G70944 | unknown_protein | 0.069 | – |

| AT2G36190 | ATCWINV4 | 0.070 | – |

flg22-induced (upper) and -repressed (lower) genes identified by microarray analysis by Lyons et al. (2013).

Fold change represents ratios of mean mRNA abundance in the light to mean mRNA abundance in the dark control. Data are representative for two independent experiments (P < 0.01).

“–” indicates that genes were not induced nor repressed more than two times by light.

Among the 4159 genes suppressed by flg22 within 30 min, 359 were dependent on light (named flg22-repressed light-dependent genes) and 370 genes were repressed by light (named flg22-repressed light-repressed genes). The genes repressed by flg22 and light-insensitive are named flg22-repressed light-independent genes. The genes rapidly suppressed by flg22 include significantly fewer genes involved in stress responses irrespective of light treatment (sFigure 1). Interestingly, the flg22-repressed light-dependent genes include a large number of genes involved with electron transport or energy, structural molecule activity, and chloroplasts; transcription factor TF activity genes were significantly overrepresented among the flg22-repressed light-repressed genes.

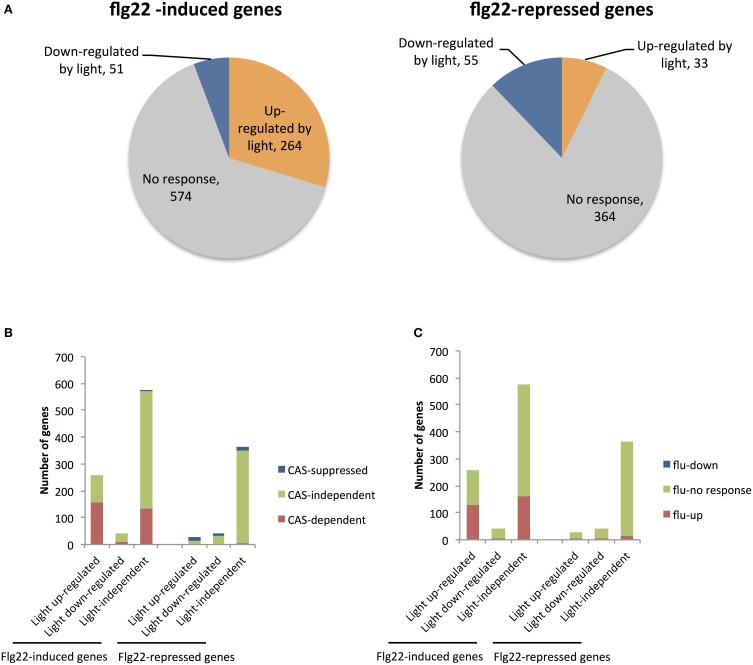

Table 2 shows that 16 of 25 genes (64%) that were markedly induced by flg22 after 30 min were also dependent on light, suggesting that light plays a critical role in the strong induction of flg22-induced genes. Thus, we further analyzed genes that are strongly (>4.0) induced by flg22. We identified 889 flg22-induced (>4.0) and 452 flg22-repressed (<0.25) genes after 30-min treatment with flg22. A comparison of these genes with the light-regulated genes identified in this study revealed that markedly flg22-induced genes include a larger number of light-dependent genes. Approximately 30% of the strongly induced genes (264 genes) were up-regulated in the light, but only 4.9% of those genes (51 genes) were down-regulated by light (Figure 1A), indicating that light plays a more significant role in the expression of genes that are largely induced by flg22.

Figure 1.

Microarray analysis of genes up- and down-regulated by light in flg22-treated seedlings. (A) The number of genes up- and down-regulated by light among sets of genes previously identified as strongly up- (>4.0) or down-regulated (<0.25) by flg22 within 30 min (Lyons et al., 2013). (B) The number of genes previously shown to be CAS-dependent (red) or CAS-suppressed (blue) or CAS-independent (green) (Nomura et al., 2012) among genes that are up- (left) and down-regulated (right) by flg22 treatment. (C) The number of genes previously shown to be induced in illuminated flu mutants (red) or suppressed (blue) (Laloi et al., 2007) among genes that are up- (left) and down-regulated (right) by flg22 treatment. Microarray analysis was performed with seedlings treated with flg22 for 30 min under light or dark conditions.

CAS is a thylakoid membrane-localized Ca2+-binding protein (Han et al., 2003; Nomura et al., 2008; Vainonen et al., 2008; Weinl et al., 2008). We previously demonstrated that CAS mediates retrograde chloroplast signals to regulate flg22-induced nuclear gene expression. We identified 1235 genes that are induced to a lesser extent by flg22 in CAS knockout cas-1 mutants than in WT plants (CAS-dependent genes), as well as 687 genes up-regulated in cas-1 plants (CAS-repressed genes). Here, we found that the CAS-dependent genes also overlapped significantly with the flg22-induced light-dependent genes. The rapidly flg22-induced light-dependent genes include 60.5% CAS-dependent genes, whereas the flg22-induced light-independent genes contain only 23.3% CAS-dependent genes (Figure 1B). On the other hand, the rapidly flg22-induced light down-regulated genes include only one CAS-suppressed gene (Figure 1B). In contrast, the flg22-repressed genes include very few CAS-dependent genes, irrespective of light treatment. These results suggest that chloroplasts and, specifically, CAS are involved in the light-mediated control of flg22-induced nuclear defense gene expression. It has been suggested that CAS is involved in 1O2 mediated retrograde signaling, facilitating chloroplast-mediated transcriptional reprogramming during plant immune responses. As shown in Figure 1C, 127 of 258 rapidly flg22-induced light-dependent genes overlapped significantly with 1565 1O2-responsive genes induced in illuminated flu mutants (fold change >3.0) (Laloi et al., 2007), suggesting that 1O2 signaling plays a role in the light-dependent activation of flg22-induced genes.

Cis-element sequences overrepresented in the light-dependent and -independent flg22-induced genes

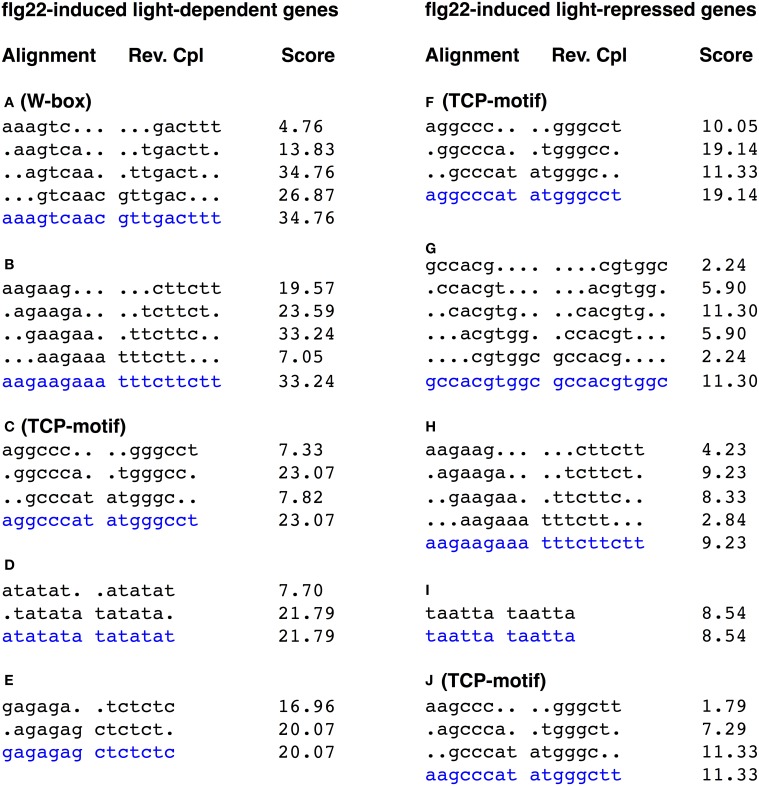

We searched for overrepresented 6-bp motifs within the 500-bp upstream region of the predicted translation start sites of the flg22-induced (>2.0) and -repressed (<0.5) genes using a motif discovery tool (RSAT, http://www.rsat.eu/). Several short sequences were significantly overrepresented in promoter regions of rapidly flg22-induced and -repressed genes (Tables S3, S4). The alignment of hexamers identified two known consensus sequences overrepresented in the promoters of genes rapidly induced by flg22 treatment. The most highly represented motifs in the promoters (500-bp upstream regions) of the light-independent (P-value, 2e-102) and light-repressed (P-value, 3.5e-23) flg22-induced genes were GGCCCA (Figure 2, sTable 3), which are part of the TCP TF-binding motifs (GGNCCCAC or GGNCCC) (Li et al., 2005). The TCP-binding motif sequence GGCCCA is also overrepresented in the light-dependent genes, suggesting that TCP is unlikely to be involved in the light-mediated response of flg22-induced genes. Furthermore, GGCCCA sequences were frequently present in the promoters of the flg22-repressed genes irrespective of light treatment.

Figure 2.

Alignments of hexamer sequences overrepresented in the promoters of genes up- and down-regulated by light in flg22-treated seedlings. The 500 bp upstream regions of 536 flg22 induced light-dependent genes and 239 flg22 induced light-repressed genes were subject to promoter motif analysis using the RSAT. The consensus is taken as the most common base pair in that position, and shown by blue characters. W-box was significantly overrepresented in the promoters of light-dependent genes, whereas TCP-motif was overrepresented in the promoters of both light-dependent and -independent genes. The score is calculated by the oligo analysis tool by default and is equivalent to log10 of the E-value.

The W-box motif (TTGACC/T) was significantly overrepresented in the promoters of the flg22-induced light-dependent genes (agtcaa; P-value, 8.4e-39, gtcaac; P-value, 6.4e-31). In contrast, the W-box was less represented in flg22-induced genes repressed by light (Figure 2). The W-box is the binding motif for WRKY family TFs, which regulate biotic and abiotic stress responses (Rushton et al., 2010). Furthermore, the W-box was not represented in the promoters of flg22-repressed genes irrespective of light treatment. On the other hand, no well-known light-responsive cis-elements, such as GT-elements (GR(T/A)AA(T/A)), G-box elements (CACGTG), or I-box elements (GATAA), were overrepresented in the light-dependent flg22-induced genes. These results suggest that WRKY TFs are involved in the rapid light-dependent expression of flg22-induced defense genes.

qRT-PCR of light-dependent expression of flg22-induced genes

SA is a key signaling molecule in plant immune responses. We found that the expression of several key genes responsible for SA accumulation were up-regulated by light in the presence of flg22. Thus, we selected four genes involved in SA biosynthesis (EDS1, EDS5, ICS1, and PAL1) and seven TF genes that act mainly in the defense response network (ANAC042, CBP60g, WRKY6, 7, 22, 33, and 46) as targets for quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR). According to the microarray data, the flg22-induced expression of the four SA biosynthesis genes (EDS1, × 2.1; EDS5, × 5.79; ICS1, × 3.61; PAL1, × 12.33) and two of the TF genes (WRKY46, × 3.37; ANAC042, × 2.57) was dependent on light, whereas that of the other five TF genes was not. In order to examine the effects of light on the expression of genes that are induced slowly in response to flg22 treatment, we added plants treated with flg22 for 2 h. As shown in Figure 3, the expression of all selected genes was up-regulated by flg22 either transiently (EDS1, ANAC042, CBP60g, WRKY22, 33, and 46) or gradually (EDS5, ICS1, PAL1, WRKY6, and 7). As expected, qRT-PCR analysis revealed that the expression of EDS1 (× 2.84), ICS1 (× 7.78), PAL1 (× 10.67), ANAC042 (× 2.41), and WRKY46 (× 9.33) was largely dependent on light in the Arabidopsis plants treated with flg22 for 30 min. These data are consistent with the microarray data. Although expression of EDS5 was slightly dependent on light based on qRT-PCR analysis (× 1.61), there was a significant difference between light- and dark-treated samples in microarray analysis. On the other hand, flg22-induced expression of CBP60g, WRKY7, and 22 was reduced by half in the dark compared to the light in qRT-PCR experiments (× 2.08, × 2.59, and × 1.77, respectively), whereas their expression was not significantly up-regulated by light in the microarray data. Expression of genes that are induced gradually by flg22, such as EDS5, ICS1, PAL1, and WRKY7, was more significantly dependent on light after 2 h. Furthermore, it should be noted that EDS1, EDS5, ICS1, and PAL1, which are involved in SA biosynthesis, showed reduced expression in the dark even before flg22 treatment, whereas the TF-related genes did not. In contrast, the expression levels of two other genes (WRKY6 and 33) were not markedly decreased in the dark, confirming the microarray data.

Figure 3.

qRT-PCR analysis of flg22-induced gene expression in the dark and light, and in the presence of photosynthesis inhibitors. Plants were treated with 1 μM flg22 in the light (orange) or dark (blue) for 30 min and 2 h, respectively. As indicated, plants were also pretreated with DBMIB (5 μM; red) or DCMU (8 μM; green) for 30 min before flg22 treatment. UBQ10 was used as an internal standard. Results shown are mean + s.e.m. from triplicate technical replicates from one of three representative experiments with similar results. P-values for qRT-PCR data were calculated using t-tests and are indicated by *p < 0.005.

Effect of electron transport inhibitors on flg22-induced gene expression

In order to examine the involvement of photosynthesis in the light-dependent defense gene expression, we analyzed the expression of flg22-induced defense genes in the presence of two specific inhibitors of photosynthetic electron transport. DCMU and DBMIB inhibit electron transport from the PS II complex to the PQ pool and from the PQ pool to the cytochrome b6/f complex, respectively (Trebst, 2007). Arabidopsis seedlings were pretreated with these inhibitors for 30 min before flg22 treatment. Electron transport rates measured using a PAM chlorophyll fluorometer were suppressed by both inhibitors to less than 10% of those in non-treated plants within 30 min (sFigure 2). Importantly, the light-dependent expression of all nine flg22-induced genes examined was significantly suppressed by DBMIB (Figure 3) to levels similar to those observed in the dark after 30 min or 2 h of flg22 treatment. However, flg22-induced gene expression was not significantly suppressed or was only partially suppressed by DCMU. In contrast, WRKY6 and 33, which exhibited light-independent expression, were not significantly suppressed by DBMIB or DCMU, indicating that electron transport inhibitors do not affect the light-independent expression of flg22-induced defense genes. These results suggest that the photosynthetic electron flow plays a key role in regulating the light-dependent expression of flg22-induced defense genes.

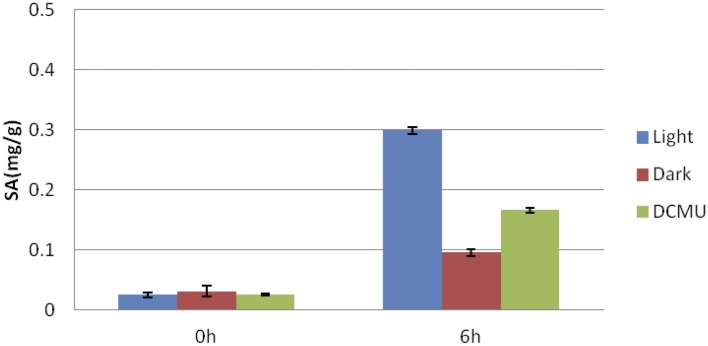

Effects of light on flg22-induced SA accumulation

We found that the flg22-induced expression of a set of genes involved in SA biosynthesis (EDS1, ICS1, EDS5, and PAL1) and regulation (CBP60g, WRKY7, and 46; Kim et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2010; van Verk et al., 2011) was dependent on light (Figure 2). Therefore, to elucidate the role of light in flg22-induced SA biosynthesis, we investigated free SA accumulation in the leaves of Arabidopsis seedlings treated with flg22 under light and dark conditions (Figure 4). Upon flg22 treatment, Arabidopsis accumulated less SA in the dark than in the light. These results indicate that light is involved in the activation of SA biosynthesis by flg22.

Figure 4.

Light-dependent salicylic acid (SA) accumulation. Flg22-induced SA accumulation was measured in leaves in the light or dark. As indicated, some plants were treated with DCMU (8 μM) for 30 min before flg22 treatment. Bars indicate the standard error of the mean (s.e.m.).

Discussion

It has been suggested that light is necessary for robust and precise immune responses in plants (Roden and Ingle, 2009; Wang et al., 2011). Several reports have suggested the involvement of photoreceptors, such as phytochromes (Griebel and Zeier, 2008) and cryptochromes (Jeong et al., 2010; Wu and Yang, 2010), in the plant immune system. It has also been indicated that photosynthesis is involved in the activation of SA biosynthesis, PR1 gene expression, and HR against infection by pathogens (Jelenska et al., 2007; Kangasjärvi et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2012). We previously demonstrated that the chloroplast Ca2+-binding protein CAS plays a role in flg22-induced immune responses through retrograde signals originating in chloroplasts to regulate defense gene expression in the nucleus (Nomura et al., 2012). To learn more about the roles of chloroplasts and photosynthesis in PAMP-induced immunity, we investigated the effects of light and photosynthesis inhibitors on bacterial flagellin peptide flg22-induced expression of nuclear-encoded defense genes in Arabidopsis.

Microarray analysis revealed that a number of the rapidly flg22-induced genes are dependent on light, but not the flg22-repressed genes. These results suggest that light is required for the activation of gene expression induced by flg22. Furthermore, we examined the effects of photosynthesis inhibitors on flg22-induced gene expression in the light. The flg22-induced expression of all light-induced genes examined (EDS1, EDS5, ICS1, ANAC042, PAL1, CBP60g, WRKY7, 22, and 46) was significantly suppressed by DBMIB, and the expression of ICS1 and ANAC042 was partially suppressed by DCMU. However, these photosynthesis inhibitors did not affect flg22-induced expression of light-independent genes (WRKY6 and 33). These results suggest that photosynthesis mediates the light-dependent expression of flg22-induced genes. DCMU and DBMIB inhibit the flow of electrons between PSII and the PQ pool, and between the PQ pool and PSI, respectively. In fact, both inhibitors significantly reduced the electron transport activity between PSII and PSI (sFigure 3), suggesting that the intersystem electron flow between PSII and PSI may be involved in the light-dependent regulation of flg22-induced gene expression.

It should be noted that DBMIB showed more significant effects on light-dependent gene expression induced by flg22 than DCMU. DBMIB reduced the expression of all eight light-dependent defense genes examined to the levels found in dark-adapted plants, while DCMU treatment did not significantly change the expression of defense genes (by more than two-fold) except for two genes, ANAC042 and ICS1. DCMU and DBMIB have opposite effects on the redox state of the PQ pool: the PQ pool is oxidized by DCMU treatment and reduced by DBMIB treatment. Thus, the redox state of the PQ pool may be important as a signal for light-dependent flg22-induced defense gene expression in plant immunity. These findings suggest that modification of the redox state plays a critical role in the generation of chloroplast-derived signals to control nuclear-encoded defense and stress-responsive genes. On the other hand, it is known that DBMIB inhibits not only photosynthetic electron transport in chloroplasts, but also mitochondrial electron transport. Although we used a low concentration of DBMIB, it is possible that it partially affects mitochondrial functions.

Previous reports demonstrated that reduction of the PQ pool by DBMIB and excess light promoted the expression of immune genes. Furthermore, recent transcription analysis of DBMIB-treated plants revealed that PQ pool reduction promoted the expression of 798 stress-responsive genes (Jung et al., 2013). Thus, it has been suggested that the PQ redox state triggers the induction of immunity- and stress-related genes. In accordance with these findings, DBMIB-induced genes were significantly overrepresented among the flg22-induced light-dependent genes (>4.0) (28.0%), but less in the group of flg22-induced genes repressed by light and light–independent genes (16.0%) (sFigure 3). These results suggest that PQ-pool redox signaling is also involved in the light-dependent expression of flg22-induced genes. However, the light-dependent expression of flg22-induced genes was largely suppressed by DBMIB (Figure 3). A mechanism linking the flg22-induced signaling and PQ-pool redox signaling remains elusive. Further studies are needed to explore the discrepancy regarding the effects of DBMIB effects on immunity-related gene expression in the presence and absence of flg22, which may shed lights on the role of PQ-pool redox in retrograde signaling to control nuclear-encoded immunity- and stress-related genes.

Perturbation of photosynthetic electron flow promotes the generation of ROS, including 1O2 in PS II, and O−2 and H2O2 in PS I. 1O2 and H2O2 may be involved in the retrograde signals to activate nuclear-encoded defense gene expression (Kangasjärvi et al., 2013) and the HR (Kim et al., 2012). Thus, ROS are candidate retrograde signals that mediate the photosynthesis-dependent regulation of nuclear-encoded defense genes. Photosynthesis inhibitors and dark conditions may suppress the electron flow-dependent ROS immune signals and subsequent defense gene expression. It is suggested that PAMPs somehow perturb the photosynthetic electron flow that leads to the generation of chloroplast-derived ROS immune signals. Previously, we demonstrated that PAMP signals are rapidly transmitted to chloroplasts to generate a transient increase in Ca2+ in chloroplasts (Nomura et al., 2012). Furthermore, our previous work implicated CAS in the generation of 1O2-mediated signals to activate the flg22-induced expression of several defense genes. Recently, it was also reported that PAMPs cause a rapid decrease in NPQ after 30 min (Manzoor et al., 2012). Thus, chloroplasts may be able to quickly recognize PAMP signals, leading to changes in photosynthesis.

SA biosynthesis induced by pathogenic infection is dependent on light (Zeier et al., 2004); consistent with this, we showed that flg22-induced accumulation of SA is also dependent on light. SA biosynthesis in plants involves two distinct pathways: the ICS and the PAL pathways. Both pathways originate from chorismate, which is the end-product of the shikimate pathway (Dempsey et al., 2011). We found that light-induced genes activated by flg22 include a number of genes involved in SA biosynthesis, including EDS1, PAD4, SAG101, EDS5, PAL1, and PAL2. qRT-PCR analysis revealed that the flg22-induced expression of EDS1, ICS1, EDS5, and PAL1 is suppressed by DBMIB. Light is also required for the flg22-induced expression of two TFs, CBP60g (Zhang et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011) and WRKY46 (van Verk et al., 2011), which are involved in the activation of SA biosynthesis genes. Furthermore, it should be noted that light is responsible for the expression of genes involved in SA biosynthesis even prior to flg22-treatment. Light may be involved in the priming of SA biosynthesis genes. It is known that SA accumulation is elevated in the light (Mateo et al., 2006). Thus, flg22-induced SA accumulation in the light may be partially due to the direct photosynthesis-mediated activation of SA accumulation in chloroplasts. Taken together, these results suggest that light activates the expression of SA biosynthesis genes through photosynthesis-mediated immune signals, leading to SA accumulation.

We found that W-box sequences are significantly enriched in the promoters of the light-dependent flg22-induced genes. The W-box is the binding motif for WRKY family TFs (Rushton et al., 2010). The expression of more than 70% of WRKY gene family members in Arabidopsis is responsive to pathogenic infection and SA treatment (Dong et al., 2003). These findings suggest that WRKY TFs play an important role in the transcription of flg22-induced defense genes in the light. Interestingly, the light-dependent flg22-induced genes (>4.0) include just three WRKY TF genes (WRKY30, 46, and 53), while 12 WRKY TF genes (WRKY6, 11, 22, 26, 33, 40, 41, 55, 62, and 70) were identified among the light-independent or -repressed flg22-induced genes. Further analyses of these three WRKY TFs may shed light on the photosynthesis-mediated immune signals.

Contrastingly, the TCP-binding motif sequences are significantly overrepresented in the promoters of most flg22-regulated genes, except for light- and flg22-repressed genes. TCP family TFs are involved in the transcriptional regulation of genes controlling the cell cycle, growth, development, circadian clock, and jasmonic acid biosynthesis (Trémousaygue et al., 2003; Li et al., 2005; Welchen and Gonzalez, 2005, 2006; Schommer et al., 2008; Hervé et al., 2009; Pruneda-Paz et al., 2009). TCP TFs may also be involved in Ca2+-dependent transcriptional regulation in Arabidopsis (Whalley et al., 2011). Furthermore, the GGCCCA and AGCCCA motifs are also similar to a FORCA promoter element (T/ATGGGC) (Evrard et al., 2009). FORCA-mediated promoter activity is induced by SA under constant light exposure, whereas SA does not activate the FORCA-mediated promoter under constant darkness (Evrard et al., 2009). The further characterization of TCP TFs and FORCA promoter elements may provide insight into the light-mediated control of flg22-repressed genes.

In summary, this study revealed that both the up- and down-regulation of defense-related genes by flg22 is dependent on light to a large extent, and suggested that photosynthesis plays a role in the light-dependent regulation of flg22-responsive genes. It is also suggested that chloroplasts produce light-dependent retrograde signals to regulate flg22-induced nuclear gene expression. Alternatively, photosynthesis may indirectly influence defense responses. Our findings further suggest that ROS and the redox state of the PQ pool are involved in this light-dependent chloroplast-mediated immune signaling. However, the molecular mechanisms linking photosynthesis and defense gene expression remain largely elusive. Further experiments are needed to clarify light-dependent retrograde chloroplast-to-nucleus signaling, which optimizes pathogen-induced defense responses in a fluctuating light environment.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Ishizaki for helpful discussion. We acknowledge Y. Yamamoto (KIST BIC) for technical assistance with the LC/MS/MS. This work was supported by JSPS and MEXT Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research to Takashi Shiina (24657036, 25291065, 25120723) and Hironari Nomura (25870423), a grant from the Mitsubishi Foundation to Takashi Shiina, and a grant for high-priority study from Kyoto Prefectural University. This work was also supported by JSPS-DGHE International grant between Japan and Indonesia.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fpls.2014.00531/abstract

References

- Cerrudo I., Keller M. M., Cargnel M. D., Demkura P. V., de Wit M., Patitucci M. S., et al. (2012). Low red/far-red ratios reduce Arabidopsis resistance to Botrytis cinerea and jasmonate responses via a COI1- JAZ10-dependent, salicylic acid-independent mechanism. Plant Physiol. 158, 2042–2052 10.1104/pp.112.193359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm S. T., Coaker G., Day B., Staskawicz B. J. (2006). Host-microbe interactions: shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell 124, 803–814 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey D. A., Volt A. C., Wildermuth M. C., Klessig D. F. (2011). ‘Salicylic acid biosynthesis and metabolism.’ Arabidopsis Book 9:e0156 10.1199/tab.0156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J., Chen C., Chen Z. (2003). Expression profiles of the Arabidopsis WRKY gene superfamily during plant defense response. Plant Mol. Biol. 51, 21–37 10.1023/A:1020780022549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evrard A., Ndatimana T., Eulgem T. (2009). FORCA, a promoter element that responds to crosstalk between defense and light signaling. BMC Plant Biol. 9:2 10.1186/1471-2229-9-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fragnière C., Serrano M., Abou-Mansour E., Métraux J. P., L'Haridon F. (2011). Salicylic acid and its location in response to biotic and abiotic stress. FEBS Lett. 585, 1847–1852 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.04.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M., Fujita Y., Noutoshi Y., Takahashi F., Narusaka Y., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., et al. (2006). Crosstalk between abiotic and biotic stress responses: a current view from the points of convergence in the stress signaling networks. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9, 1–7 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göhre V., Jones A. M., Sklenáø J., Robatzek S., Weber A. P. (2012). Molecular crosstalk between PAMP-triggered immunity and photosynthesis. Mol. Plant Microb. Interact. 25, 1083–1092 10.1094/MPMI-11-11-0301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göhre V., Robatzek S. (2008). Breaking the barriers: microbial effector molecules subvert plant immunity. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 46, 189–215 10.1146/annurev.phyto.46.120407.110050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griebel T., Zeier J. (2008). Light regulation and daytime dependency of inducible plant defenses in Arabidopsis: phytochrome signaling controls systemic acquired resistance rather than local defense. Plant Physiol. 147, 790–801 10.1104/pp.108.119503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S., Tang R., Anderson L. K., Woerner T. E., Pei Z. M. (2003). A cell surface receptor mediates extracellular Ca(2+) sensing in guard cells. Nature 425, 196–200 10.1038/nature01932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervé C., Dabos P., Bardet C., Jauneau A., Auriac M. C., Ramboer A., et al. (2009). In vivo interference with AtTCP20 function induces severe plant growth alterations and deregulates the expression of many genes important for development. Plant Physiol. 149, 1462–1477 10.1104/pp.108.126136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua J. (2013). Modulation of plant immunity by light, circadian rhythm and temperature. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16, 1–8 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihama N., Yamada R., Yoshioka M., Katou S., Yoshioka H. (2011). Phosphorylation of the Nicotiana benthamiana WRKY8 transcription factor by MAPK functions in the defense response. Plant Cell 23, 1153–1170 10.1105/tpc.110.081794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelenska J., Yao N., Vinatzer B. A., Wright C. M., Brodsky J. L., Greenberg J. T. (2007). A J domain virulence effector of Pseudomonas syringae remodels host chloroplasts and suppresses defenses. Curr. Biol. 17, 499–508 10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong R. D., Chandra-Shekara A. C., Barman S. R., Navarre D., Klessig D. F., Kachroo A., et al. (2010). Cryptochrome 2 and phototropin 2 regulate resistance protein-mediated viral defense by negatively regulating an E3 ubiquitin ligase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 13538–13543 10.1073/pnas.1004529107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H.-S., Crisp P., Estavillo G. M., Cole B., Hong F., Mockler T. C., et al. (2013). Subset of heat-shock transcription factors required for the early response of Arabidopsis to excess light. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 14474–14479 10.1073/pnas.1311632110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangasjärvi S., Neukermans J., Li S., Aro E. M., Noctor G. (2012). Photosynthesis, photorespiration, and light signalling in defense responses. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 1619–1636 10.1093/jxb/err402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangasjärvi S., Tikkanen M., Durian G., Aro E. M. (2013). Photosynthetic light reactions - an adjustable hub in basic production and plant immunity signaling. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 81, 128–134 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpiński S., Szechyńska-Hebda M., Wituszyńska W., Burdiak P. (2013). Light acclimation, retrograde signalling, cell death and immune defences in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 36, 736–744 10.1111/pce.12018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C., Meskauskiene R., Zhang S., Lee K. P., Ashok M. L., Blajecka K., et al. (2012). Chloroplasts of Arabidopsis are the source and a primary target of a plant-specific programmed cell death signaling pathway. Plant Cell. 24, 3026–3039 10.1105/tpc.112.100479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. C., Fan B., Chen Z. (2006). Pathogen-induced Arabidopsis WRKY7 is a transcriptional repressor and enhances plant susceptibility to Pseudomonas syringae. Plant Physiol. 142, 1180–1192 10.1104/pp.106.082487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laloi C., Stachowik M., Pers-Kamczyc E., Warzych E., Murgia I., Apel K. (2007). Cross-talk between singlet oxygen- and hydrogen peroxide- dependent signaling of stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 672–677 10.1073/pnas.0609063103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. X., Potuschak T., Colón-Carmona A., Gutiérrez R. A., Doerner P. (2005). Arabidopsis TCP20 links regulation of growth and cell division control pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 12978–12983 10.1073/pnas.0504039102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons R., Iwase A., Gänsewig T., Sherstnev A., Duc C., Barton G. J., et al. (2013). The RNA-binding protein FPA regulates flg22-triggered defense responses and transcription factor activity by alternative polyadenylation. Sci. Rep. 3, 2866 10.1038/srep02866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor H., Chiltz A., Madani S., Vatsa P., Schoefs B., Pugin A., et al. (2012). Calcium signatures and signaling in cytosol and organelles of tobacco cells induced by plant defense elicitors. Cell Calcium. 51, 434–444 10.1016/j.ceca.2012.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo A., Funck D., Mühlenbock P., Kular B., Mullineaux P. M., Karpinski S. (2006). Controlled levels of salicylic acid are required for optimal photosynthesis and redox homeostasis. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 1795–1807 10.1093/jxb/erj196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael T. P., Mockler T. C., Breton G., McEntee C., Byer A., Trout J. D., et al. (2008). Network discovery pipeline elucidates conserved time-of-day-specific cis-regulatory modules. PLoS Genetics 4:e14 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mühlenbock P., Szechynska-Hebda M., Plaszczyca M., Baudo M., Mateo A., Mullineaux P. M., et al. (2008). Chloroplast signaling and LESION SIMULATING DISEASE1 regulate crosstalk between light acclimation and immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20, 2339–2356 10.1105/tpc.108.059618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura H., Komori T., Kobori M., Nakahira Y., Shiina T. (2008). Evidence for chloroplast control of external Ca2+-induced cytosolic Ca2+ transients and stomatal closure. Plant J. 53, 988–98 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03390.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura H., Komori T., Uemura S., Kanda Y., Shimotani K., Nakai K., et al. (2012). Chloroplast-mediated activation of plant immune signalling in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 3, 926 10.1038/ncomms1926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruneda-Paz J. L., Breton G., Para A., Kay S. A. (2009). A functional genomics approach reveals CHE as a component of the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Science 323, 1481–1485 10.1126/science.1167206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts M. R., Paul N. D. (2006). Seduced by the dark side: integrating molecular and ecological perspectives on the influence of light on plant defence against pests and pathogens. New Phytol. 170, 677–699 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01707.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roden L. C., Ingle R. A. (2009). Lights, rhythms, infection: the role of light and the circadian clock in determining the outcome of plant-pathogen interactions. Plant Cell 21, 2546–2552 10.1105/tpc.109.069922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton P. J., Somssich I. E., Ringler P., Shen Q. J. (2010). WRKY transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 247–258 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schommer C., Palatnik J. F., Aggarwal P., Chételat A., Cubas P., Farmer E. E., et al. (2008). Control of jasmonate biosynthesis and senescence by miR319 targets. PLoS Biol. 6:e230 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szechyńska-Hebda M., Karpiński S. (2013). Light intensity-dependent retrograde signalling in higher plants. J. Plant Physiol. 170, 1501–1516 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trebst A. (2007). Inhibitors in the functional dissection of the photosynthetic electron transport system. Photosynth. Res. 92, 217–224 10.1007/s11120-007-9213-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trémousaygue D., Garnier L., Bardet C., Dabos P., Hervé C., Lescure B. (2003). Internal telomeric repeats and ‘TCP domain’ protein-binding sites cooperate to regulate gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana cycling cells. Plant J. 33, 957–966 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01682.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vainonen J. P., Sakuragi Y., Stael S., Tikkanen M., Allahverdiyeva Y., Paakkarinen V., et al. (2008). Light regulation of CaS, a novel phosphoprotein in the thylakoid membrane of Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS J. 275, 1767–1777 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06335.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Verk M. C., Bol J. F., Linthorst H. J. (2011). WRKY transcription factors involved in activation of SA biosynthesis genes. BMC Plant Biol. 11:89 10.1186/1471-2229-11-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Barnaby J. Y., Tada Y., Li H., Tör M., Caldelari D., et al. (2011). Timing of plant immune responses by a central circadian regulator. Nature 470, 110–114 10.1186/1471-2229-11-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinl S., Held K., Schlücking K., Steinhorst L., Kuhlgert S., Hippler M., et al. (2008). A plastid protein crucial for Ca2+-regulated stomatal responses. New Phytol. 179, 675–686 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02492.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welchen E., Gonzalez D. H. (2005). Differential expression of the Arabidopsis cytochrome c genes Cytc-1 and Cytc-2. Evidence for the involvement of TCP-domain protein-binding elements in anther- and meristem-specific expression of the Cytc-1 gene. Plant Physiol. 139, 88–100 10.1104/pp.105.065920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welchen E., Gonzalez D. H. (2006). Overrepresentation of elements recognized by TCP-domain transcription factors in the upstream regions of nuclear genes encoding components of the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation machinery. Plant Physiol. 141, 540–545 10.1104/pp.105.075366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalley H. J., Sargeant A. W., Steele J. F. C., Lacoere T., Lamb R., Saunders N. J., et al. (2011). Transcriptomic analysis reveales calcium regulation of specific promoter motifs in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23, 4079–4095 10.1105/tpc.111.090480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L., Yang H. Q. (2010). CRYPTOCHROME 1 is implicated in promoting R protein-mediated plant resistance to Pseudomonas syringae in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 3, 539–548 10.1093/mp/ssp107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeier J., Pink B., Mueller M. J., Berger S. (2004). Light conditions influence specific defence responses in incompatible plant-pathogen interactions: uncoupling systemic resistance from salicylic acid and PR-1 accumulation. Planta 219, 673–683 10.1007/s00425-004-1272-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Xu S., Ding P., Wang D., Cheng Y. T., He J., et al. (2010). Control of salicylic acid synthesis and systemic acquired resistance by two members of a plant-specific family of transcription factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 18220–18225 10.1073/pnas.1005225107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.