Abstract

Context:

Familial dysalbuminemic hyperthyroxinemia, characterized by abnormal circulating albumin with increased T4 affinity, causes artefactual elevation of free T4 concentrations in euthyroid individuals.

Objective:

Four unrelated index cases with discordant thyroid function tests in different assay platforms were investigated.

Design and Results:

Laboratory biochemical assessment, radiolabeled T4 binding studies, and ALB sequencing were undertaken. 125I-T4 binding to both serum and albumin in affected individuals was markedly increased, comparable with known familial dysalbuminemic hyperthyroxinemia cases. Sequencing showed heterozygosity for a novel ALB mutation (arginine to isoleucine at codon 222, R222I) in all four cases and segregation of the genetic defect with abnormal biochemical phenotype in one family. Molecular modeling indicates that arginine 222 is located within a high-affinity T4 binding site in albumin, with substitution by isoleucine, which has a smaller side chain predicted to reduce steric hindrance, thereby facilitating T4 and rT3 binding. When tested in current immunoassays, serum free T4 values from R222I heterozygotes were more measurably abnormal in one-step vs two-step assay architectures. Total rT3 measurements were also abnormally elevated.

Conclusions:

A novel mutation (R222I) in the ALB gene mediates dominantly inherited dysalbuminemic hyperthyroxinemia. Susceptibility of current free T4 immunoassays to interference by this mutant albumin suggests likely future identification of individuals with this variant binding protein.

Familial dysalbuminemic hyperthyroxinemia (FDH), the most common heritable cause of elevated total T4 levels in euthyroid subjects, has an estimated prevalence of 1 in 10 000 individuals (1). Consistent with its dominant inheritance, the disorder is associated with heterozygous albumin (ALB) gene defects, generating mutant proteins with enhanced T4 binding affinity. An arginine-to-histidine mutation at residue 218 (R218H) was first described (2, 3) and is the most common causal variant in Caucasians but also recognized in Hispanic/Puerto Rican (4) and Chinese (5) cases. Substitution of proline for arginine at the same codon (R218P), resulting in markedly elevated T4 concentrations, has been described in Japanese and Swiss subjects (6, 7). A third albumin mutation (L66P), identified in a Thai kindred, is associated with predominant elevation of T3 concentrations (8).

Here we describe a novel, heterozygous ALB defect, with substitution of isoleucine for arginine at codon 222 (R222I) in three African (Somali) subjects and one East European (Croatian) family, identified on the basis of discrepant thyroid function tests, with hyperthyroxinemia. Enhanced T4 binding to this albumin variant correlates with molecular modeling showing that this amino acid change likely reduces steric hindrance within its high-affinity T4 binding pocket. Elevated free T4 measurements in most commonly used immunoassay platforms suggests that additional cases harboring this novel FDH variant will be identified.

Patients and Methods

Methods

All investigations were part of an ethically approved protocol and/or clinically indicated, being undertaken with the consent from patients and/or next of kin.

Biochemical measurements

Thyroid hormones [free T4 (FT4) and free T3] and TSH were measured using automated immunoassay systems (Advia Centaur; Siemens; Wallac DELFIA Ultr; PerkinElmer; Access; Beckman-Coulter; Elecsys; Roche Diagnostics; Architect; Abbott Diagnostics). T4 binding globulin (TBG) was measured by immunoassay (Siemens Immulite). Equilibrium dialysis FT4 was measured by RIA (Quest Diagnostics). Total T3 and rT3 were measured in deproteinized samples by separation using C18 column chromatography followed by electrospray mass spectrometry or (rT3 in a subset of cases) by competitive RIA (Quest Diagnostics).

Radiolabeled T4 binding studies and gel electrophoresis

Serum binding of 125I-T4 was assayed with excess cold T4 to saturate binding sites on TBG as described previously (9); inclusion of cold rT3 in this assay enabled comparison of its binding with R218H and R222I albumin mutants. 125I-T4 binding to serum proteins was analyzed by gel electrophoresis (Mayo Medical Laboratories) as described previously (10).

Albumin gene sequencing

Exons of the human albumin gene were PCR amplified from genomic DNA using specific primers (listed in Supplemental Material) and analyzed by Sanger sequencing.

Molecular modeling

The R222I mutant albumin was modeled (Pymol) using previously described wild-type albumin (1bm0) albumin-T4 (1hk1), R218H FDH mutant albumin-T4 (1hk2), and R218P FDH mutant albumin-T4 (1hk3) crystal structures (11), selecting the rotamer with the fewest clashes.

Results

Clinical and biochemical features

Proband 1 was a 2.5-year-old, Somalian boy (P1), investigated for low weight, was found to have elevated FT4 but unsuppressed TSH (Table 1). His mother and two siblings exhibited similarly abnormal thyroid function tests [mother: FT4 36.9 pmol/L, (reference range) [RR] 10–24), TSH 1.57 mU/L (0.5–5.0); sibling 1: FT4 30.9 pmol/L (RR 11–22), TSH 2.01 mU/L (RR 0.4–3.5); sibling 2: FT4 48.5 (12–25), TSH 3 mU/L (RR 0.4–3.5)]. Proband 2 was an unrelated 41-year-old Somali male (P2) and was referred with a similar biochemistry (Table 1). Proband 3 was a 20-year-old Somali female (P3), investigated for fatigue and weight gain, and showed hyperthyroxinemia with nonsuppressed TSH (Table 1). Proband 4 was a 22-year-old Caucasian female (P4) from Croatia, investigated for asthenia and anxiety, and was found to have hyperthyroxinemia with nonsuppressed TSH. Her sibling and father exhibited similar thyroid function tests [father: FT4 41.2 pmol/L (RR 10–22), TSH 3.2 mU/L (RR 0.28–4.3); sibling: FT4 33.5 pmol/L (RR10–22), TSH 3.0 mU/L (RR 0.28–4.3)].

Table 1.

Biochemical Measurements in Index Cases

| Proband 1 | Proband 2 | Proband 3 | Proband 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSH, mU/L | 1.89 | 1.4 | 1.71 | 3.6 |

| Platform | Immulite 2000 | Roche Elecsys | Roche Elecsys | Roche Elecsys |

| Reference rangea | 0.3–4.0 | 0.27–4.2 | 0.3–4.0 | 0.28–4.3 |

| FT4, pmol/L | 35.3 | 50.9 | 39.3 | 37 |

| Platform | Immulite 2000 | Roche Elecsys | Roche Elecsys | Roche Elecsys |

| Reference rangea | 12–25 | 12–22 | 9–20 | 10–22 |

| FT4, pmol/L | 21.8 | 22 | 20.7 | 16 |

| Platform | DELFIA | DELFIA | DELFIA | DELFIA |

| Reference range | 9–20 | 9–20 | 9–20 | 9–20 |

| FT4 by equilibrium dialysis, ng/dL | 2.2 | ND | 2.1 | 1.7 |

| Platform | Quest | ND | Quest | Quest |

| Reference rangea | 0.8–2.7 | ND | 1.0–2.4 | 0.8–2.7 |

| Total T4, nmol/L | 303 | 273 | 275 | 204 |

| Platform | DELFIA | DELFIA | DELFIA | DELFIA |

| Reference range | 69–141 | 69–141 | 69–141 | 69–141 |

| TBG, μg/mL | 20.3 | 20.5 | 20.6 | 16.5 |

| Platform | Immulite | Cisbio | Immulite | Immulite |

| Reference range | 14–31 | 11.3–28.9 | 14–31 | 14–31 |

| Radiolabeled T4 binding to serum | 37% | Increasedb | 38% | 49% |

| Reference range | <20% | <20% | <20% | <20% |

Numbers in bold denote that they are outside the reference range. Abbreviation: ND, not done.

Varying reference data for the same assay platform reflect differing normal ranges used by local laboratories.

Exact percentage binding unavailable.

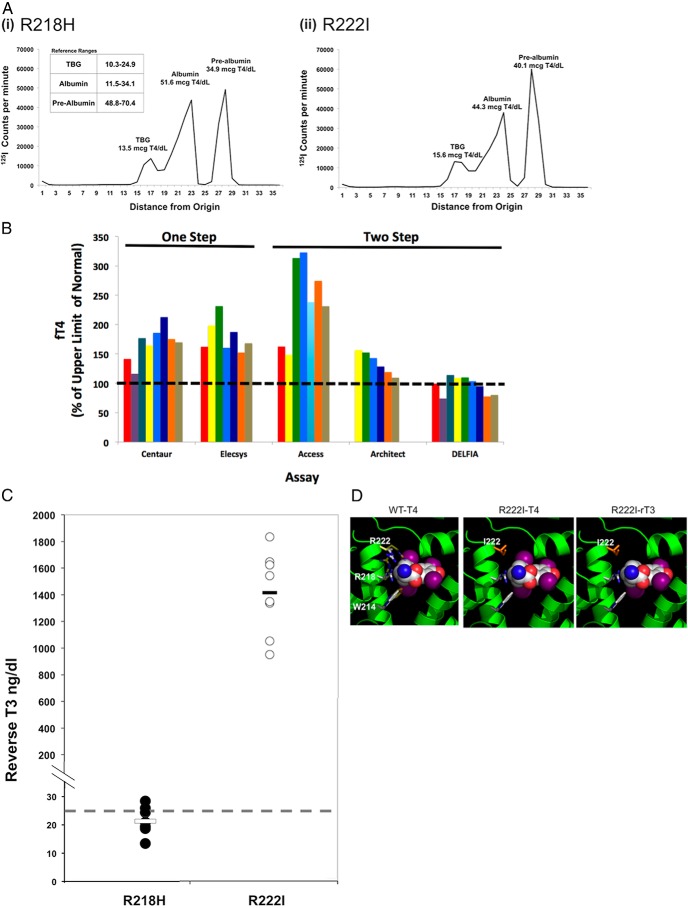

Although local testing in all probands showed markedly raised FT4 concentrations, FT4 measurements using the two-step DELFIA method were quite discordant, being near normal; furthermore, FT4 measured by equilibrium dialysis was normal (Table 1). These observations suggested analytical interference with FT4 measurement, with diagnostic possibilities including abnormal circulating thyroid hormone binding proteins. Although total T4 was raised in each proband, the TBG levels were normal (Table 1). Hence, an albumin protein abnormality was considered. Serum binding of 125I-T4 in each proband was markedly raised (Table 1), comparable with values (28%–44%) in sera from known FDH cases, harboring the R218H albumin mutation. Gel electrophoresis of serum from an affected individual identified excess 125I-T4 binding to albumin [Figure 1A, panel (ii)]. The abnormal electrophoretic profile was similar to the pattern of 125I-T4 binding in serum from a known FDH case, harboring the R218H albumin mutation [Figure 1A, panel (i)].

Figure 1.

Biochemical studies in FDH cases and molecular modeling of albumin mutation. A, Electrophoregrams showing binding of 125I-T4 to serum proteins in serum containing an albumin mutation (R218H) known to confer FDH [left panel, (i)] and an individual with hyperthyroxinemia and elevated radiolabeled T4 binding to serum containing an R222I albumin mutation [right panel, (ii)]. B, FT4 measured by various one-step or two-step immunoassays in sera from different cases containing the R222I mutant albumin protein. C, rT3 measured by liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry in sera from R218H and R222I mutation cases. D, Crystallographic modeling of T4, bound to the high-affinity T4-binding site in subdomain IIA of the albumin molecule, illustrating the steric constraints imposed on T4 binding. The left panel is a composite, showing the positions (in yellow) of the side chains of W214, R218, and R222 in the albumin structure not bound to T4, superimposed on these displaced side chains (white) in the structure of albumin bound to T4. When R222 is replaced by isoleucine (middle panel, in orange), the shorter side chain presents less steric hindrance to T4 binding. rT3 binding to R222I mutant albumin is also likely to be enhanced (right panel) because the loss of the inner iodine will further relieve steric hindrance with side chains of residues at positions 222 and 214.

Molecular genetic studies

ALB sequencing of probands (P1-P4) revealed heterozygosity for a single-nucleotide substitution (AGA to ATA), corresponding to an arginine to isoleucine change at codon 222 in the predicted protein sequence, with no other coding region changes. The mutation is not present in 100 control DNA samples and normal genome data sets (dBSNP, 1000 Genomes) including more than 2000 African-American alleles (Exome Variant Server, NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project, Seattle, WA, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/, May 11, 2013). Genotyping for single-nucleotide polymorphisms around ALB indicates that the Somali cases share an extended haplotype, suggesting common ancestry, whereas the mutation occurs on a different haplotype background in Caucasian proband 4 (Supplemental Figure 1).

The mother and siblings of P1, with abnormal thyroid function tests, were also heterozygous for this nucleotide change. The ALB mutation cosegregated with phenotype in family members of P4, being present in individuals (father and brother) with elevated FT4 results and serum 125I-T4 binding and absent in her unaffected mother with normal FT4 concentrations and radiolabeled hormone binding (Supplemental Figure 2).

FT4, T3, and rT3 measurements in affected cases

The index cases were identified on the basis of discordant FT4 results using one-step (Roche Elecsys or Siemens Immulite) hormone assays. To investigate the performance of commonly used assay platforms, FT4 concentrations were measured using sera from ALB R222I heterozygotes in different two-step [(DELFIA Ultra (PerkinElmer), Architect (Abbot Diagnostics), Access (Beckman Coulter)] and one-step [Advia Centaur (Siemens Medical Diagnostics); Elecsys E170 (Roche)] immunoassays (Figure 1B). Affected individuals exhibited a similar pattern, with FT4 measurements being more elevated in one-step (Centaur, Elecsys) than two-step (Architect, Delfia) platforms; exceptionally, FT4 values were most markedly raised with the two-step Beckman Access method.

We assayed total T3 and rT3 by tandem mass spectrometry using ALB R222I heterozygote sera and compared concentrations with R218H ALB FDH cases. Total T3 concentrations were slightly raised in two R222I ALB cases but normal in all other subjects with either variant albumin (Supplemental Figure 3). In contrast, rT3 concentrations were markedly elevated in ALB R222I sera, being 40- to 70-fold elevated, but were normal or only marginally raised (1.1-fold) in R218H ALB FDH cases (Figure 1C). Such elevation was also seen when rT3 was measured by immunoassay in sera from R222I FDH cases (rT3 > 2 ng/mL, normal range 0.11–0.32 ng/mL). rT3 displaced 125I-T4 binding to R222I ALB sera much more readily than in control or R218H FDH cases (Supplemental Figure 4).

Molecular modeling of R222I mutant albumin

In the T4-albumin crystal structure, T4 interacts with side chains of three residues (R218, W214, and R222) within a high-affinity binding site. Comparison with an unoccupied protein structure shows that T4 binding requires significant rearrangement of these three side chains (Figure 1D, left panel). Substitution of arginine at codon 222 by isoleucine reduces steric hindrance, enhancing T4 binding (Figure 1D, middle panel). Iodines in the inner ring of T4 are in close contact with side chains of R222 and W214. Superimposition of rT3 (Figure 1D, right panel) with T4, reveals that the absence of an inner ring iodine would provide more space in the pocket, with both the isoleucine 222 and tryptophan 214 imposing less steric hindrance; in contrast, substitutions at R218 are not predicted to influence rT3 binding.

Discussion

Six individuals from three unrelated families of East African and three subjects of Caucasian East European origin were found to have euthyroid hyperthyroxinemia and nonsuppressed TSH concentrations, with assay-dependent discordant FT4 measurements suggesting analytical interference. Normal circulating TBG concentrations together with increased radiolabeled 125I-T4 binding to serum or albumin from these cases suggested an ALB abnormality. Affected individuals are heterozygous for a missense ALB mutation (R222I); in one kindred, in which family members were available, heterozygosity for this ALB mutation segregates with both abnormal thyroid biochemical and 125I-T4 binding phenotypes.

The high-affinity binding site for T4 in albumin contains three residues (R218, R222, and W214) whose side chains undergo marked displacement to accommodate T4 binding (11). Consistent with this structural observation, substitution of histidine or proline with smaller side chains for arginine 218 likely reduces steric hindrance, explaining enhanced T4 binding of these mutant proteins (11, 12). Likewise, modeling predicts that substitution of isoleucine for arginine 222, as occurs in our cases, also reduces steric hindrance. Indeed, an artificial albumin mutant (R222M), with a methionine residue with smaller side chain replacing R222, exhibits increased T4 binding (13).

Our results suggest that, in general, one-step FT4 immunoassay methods are more susceptible to interference by R222I FDH sera than two-step designs. This pattern resembles differential susceptibility of such assays with R218H FDH sera (14), presumably reflecting the interaction of labeled T4 analogs with albumin in one-step assays, which does not occur in two-step or back-titration methods. It has been suggested that incubation buffer composition in the Beckman Access assay promotes T4-albumin interaction, making this two-step method unexpectedly susceptible to interference (15).

Total T3 concentrations were raised in two R222I FDH sera and normal in R218H FDH cases; this finding is in accord with T3 concentrations being raised in only 12% of R218H FDH (3). In contrast, total rT3 concentrations were uniformly and more strikingly elevated in R222I sera than R218H FDH cases. Previously, raised rT3 was documented in 50% of R218H FDH cases (8) and the R218H mutant albumin binds rT3 with increased affinity (13). Because total hormone levels likely reflect hormone interaction with albumin in subjects with otherwise normal TH binding proteins, we hypothesized that rT3 binding to R222I mutant albumin is enhanced, and competition assays with radiolabeled T4 confirmed this. Structural modeling suggests a basis for this, with the absence of an inner ring iodine in rT3, likely to further diminish steric hindrance from side chains of residues (Ile 222, Trp 214) which are in closest proximity to the inner ring iodines. The biochemical pattern of raised T4, normal T3, and elevated rT3 concentrations in R222I FDH resembles that seen in patients after amiodarone exposure (16), raising the possibility that this genetic form of FDH might be confused with other clinical diagnostic possibilities.

In summary, we have identified a novel, heterozygous ALB mutation (R222I) in subjects of both East African and Caucasian Eastern European origin. R222I heterozygote sera exhibit a biochemical profile of elevated FT4 concentrations in many current immunoassay platforms, suggesting that this genetic cause of dysalbuminemic hyperthyroxinemia will be readily identified, perhaps in other populations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Michael Caulfield (Quest Diagnostics) for liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry T3 and rT3 measurement and Dr Larry Dodge (Mayo Medical Laboratories) for 125I- T4 binding protein electrophoresis.

This work was supported by funding from the Wellcome Trust (Grant 100585/Z/12/Z, to N.S., Grant 095564/Z/11/Z, to K.C.) and National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (to C.M., and M.G.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ALB

- albumin

- FDH

- familial dysalbuminemic hyperthyroxinemia

- FT4

- free T4

- RR

- reference range

- TBG

- T4 binding globulin.

References

- 1. Jensen IW, Faber J. Familial dysalbuminaemic hyperthyroxinaemia: a review. J R Soc Med. 1988;81:34–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Petersen CE, Scottolini AG, Cody LR, Mandel M, Reimer N, Bhagavan NV. A point mutation in the human serum albumin gene results in familial dysalbuminaemic hyperthyroxinaemia. J Med Genet. 1994;31:355–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sunthornthepvarakul T, Angkeow P, Weiss RE, Hayashi Y, Refetoff S. An identical missense mutation in the albumin gene results in familial dysalbuminaemic hyperthyroxinaemia in 8 unrelated families. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;202:781–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. DeCosimo DR, Fang SL, Braverman LE. Prevalence of familial dysalbuminemic hyperthyroxinemia in Hispanics. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107(5):780–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tiu SC, Choi KL, Shek CC, Lau TC. A Chinese family with familial dysalbuminaemic hyperthyroxinaemia. Hong Kong Med J. 2003;9(6):464–446 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wada N, Chiba H, Shimizu C, Kijima H, Kubo M, Koike T. A novel missense mutation in codon 218 of the albumin gene in a distinct phenotype of familial dysalbuminaemic hyperthyroxinemia in a Japanese kindred. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:3246–3250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pannain S, Feldman M, Eiholzer U, Weiss RE, Scherberg NH, Refetoff S. Familial dysalbuminaemic hyperthyroxinaemia in a Swiss family caused by a mutant albumin (R218P) shows an apparent discrepancy between serum concentration and affinity for thyroxine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2786–2792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sunthornthepvarakul T, Likitmaskul S, Ngowngarmratana S, et al. Familial dysalbuminaemic hypertriiodothyroninemia: a new, dominantly inherited albumin defect. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1448–1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stewart MF, Ratcliffe WA, Roberts I. Thyroid function tests in patients with familial dysalbuminaemic hyperthyroxinaemia (FDH). Ann Clin Biochem. 1986;23:59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hay I, Klee GG. Thyroid dysfunction. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1988;17:473–509 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Petitpas I, Petersen CE, Ha C-E, et al. Structural basis of albumin-thyroxine interactions and familial dysalbuminaemic hyperthyroxinemia. PNAS. 2003;100:6440–6445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Petersen CE, Ha C-E, Harohalli K, et al. Structural investigations of a new familial dysalbuminaemic hyperthyroxinaemia genotype. Clin Chem. 1999;45:1248–1254 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Petersen CE, Ha C-E, Jameson DM, Bhagavan NV. Mutations in a specific human serum albumin thyroxine binding site define the structural basis of familial dysalbuminemia hyperthyroxinemia. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19110–19117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cartwright D, O'Shea P, Rajanayagam O, et al. Familial dysalbuminemic hyperthyroxinemia: a persistent diagnostic challenge. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1044–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ross HA, de Rijke YB, Sweep FCGJ. Spuriously high free thyroxine values in familial dysalbuminemia hyperthyroxinaemia. Clin Chem. 2011;57:524–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eskes S, Wiersinga W. Amiodarone and thyroid. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;23:735–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]