Abstract

Context:

Denosumab 60 mg sc injection every 6 months for 36 months was well tolerated and effective in reducing the incidence of vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fracture in predominantly Caucasian postmenopausal women with osteoporosis.

Objective:

The objective of this phase 3 fracture study was to examine the antifracture efficacy and safety of denosumab 60 mg in Japanese women and men with osteoporosis compared with placebo.

Design and Setting:

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with an open-label active comparator as a referential arm was conducted.

Patients:

Subjects were 1262 Japanese patients with osteoporosis aged 50 years or older, who had one to four prevalent vertebral fractures.

Intervention:

Subjects were randomly assigned to receive denosumab 60 mg sc every 6 months (n = 500), placebo for denosumab (n = 511), or oral alendronate 35 mg weekly (n = 251). All subjects received daily supplements of calcium and vitamin D.

Main Outcome Measure:

The primary endpoint was the 24-month incidence of new or worsening vertebral fracture for denosumab vs placebo.

Results:

Denosumab significantly reduced the risk of new or worsening vertebral fracture by 65.7%, with incidences of 3.6% in denosumab and 10.3% in placebo at 24 months (hazard ratio 0.343; 95% confidence interval 0.194–0.606, P = .0001). No apparent difference in adverse events was found between denosumab and placebo during the first 24 months of the study.

Conclusion:

These results provide evidence of the efficacy and safety of denosumab 60 mg sc every 6 months in Japanese subjects with osteoporosis.

Denosumab, a fully human monoclonal IgG2 antibody against the receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand, given as a sc at a dose of 60 mg every 6 months increased bone mineral density (BMD) at the lumbar spine and total hip and reduced the incidence of new vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fractures in predominantly Caucasian postmenopausal women with osteoporosis in the Fracture REduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis every 6 Months (FREEDOM) study (1). However, the subgroup analyses did not show significant reduction in the incidence of new vertebral fracture in nonwhites and subjects living in North and Latin America, presumably due to the small number of subjects and/or the low incidence of fracture in these subgroups (2).

Biannual sc of denosumab 60 mg was selected as an optimum dose in Japanese postmenopausal women with osteoporosis in the dose-response study (3). The objective of this study was to assess the efficacy of denosumab on fracture risk reduction and safety in Japanese subjects with osteoporosis compared with placebo for 24 months. The exploratory objective was set to consider the clinical positioning of denosumab for the osteoporosis treatment in Japanese patients comparing the data of BMD and bone turnover markers (BTMs) with alendronate 35 mg weekly as the recommended dosage in the prescribing information in Japan. Fracture and safety data were also collected in the alendronate group.

Subjects and Methods

Study design

Denosumab fracture Intervention RandomizEd placebo Controlled Trial (DIRECT) was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial with an open-label active comparator as a referential arm. Subjects were randomly assigned in a 2:2:1 ratio to receive one of the following three treatments for 24 months: denosumab 60 mg sc every 6 months, placebo for denosumab, or open-label oral alendronate 35 mg weekly. Randomization was stratified by gender. All subjects who received the investigational product (IP) were administered daily supplements containing at least 600 mg calcium and 400 IU vitamin D throughout the study period.

The study was designed by the Steering Committee (T.Nakam., T.Matsu., T.Su., and T.H.) and sponsor (H.T., K.W., and T.O). The sponsor had responsibility for data collection and quality control. The Safety Monitoring Board (T.M., I.G., H.Y., Y.T., S.T., S.M., and T.Y.) met semiannually to monitor subject safety, based on blinded data. Radiographs were assessed by the Central Committee (T.Nakan., M.I., T.So., and M.F.). The oral events reported from the local investigators were reviewed by the dental expert (T.Y.). M.S. oversaw the study conduct. Analyses for publication were the responsibility of the sponsor. The manuscript was contributed to and approved by all authors.

Subjects

Japanese subjects with osteoporosis including postmenopausal women and men aged 50 years or older were eligible for the study if they had one to four prevalent vertebral fractures with a BMD T-score of less than −1.7 (Young Adult Mean in Japan 80%) at the lumbar spine or −1.6 (Young Adult Mean in Japan 80%) at the total hip by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry based on the diagnostic criteria of primary osteoporosis in Japan (4). Subjects were excluded if they had more than two moderate and/or any severe vertebral fractures on lateral spine radiographs by semiquantitative (SQ) grading (5) or if they had evidence of the conditions such as hyperparathyroidism, hypoparathyroidism, hypercalcemia, hypocalcemia, rheumatoid arthritis, or Paget's disease of the bone. The subjects were ineligible if they had taken oral bisphosphonates for more than 3 years. Those who had taken bisphosphonates for less than 3 years were eligible if they had received bisphosphonates for less than 2 weeks or had no dosing before 6 months prior to the study enrollment. Subjects were excluded if they had taken selective estrogen receptor modulators, calcitonin, hormone replacement therapy, or teriparatide within 6 weeks before the study enrollment. Additional exclusion criteria included evidence of 2.0 mg/dL or greater serum creatinine, 80 IU/L or greater aspartate aminotransferase, 90 IU/L or greater alanine aminotransferase, or other conditions judged to be inadequate for participation in the study.

The institutional review boards at all study sites approved the protocol and consent process for this study, and all subjects provided written informed consent before participation. This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with good clinical practice.

Efficacy endpoints

The primary endpoint was the 24-month incidence of radiographically determined morphometrical new or worsening vertebral fracture for denosumab vs placebo. The secondary end points included the incidence of new vertebral fracture and nonvertebral fracture; the percentage change from baseline in BMD at the lumbar spine (L1-L4), total hip, femoral neck, and distal one third radius; and the percentage change from baseline in serum concentrations of the BTMs, C-telopeptide of type 1 collagen (CTX-1), and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP). The exploratory endpoint included the incidence of major nonvertebral fracture known to be significantly associated with decreased BMD (6), consisting of the proximal humerus, forearm, ribs/clavicle, pelvis, hip, distal femur, and proximal tibia. The incidence of nonmajor nonvertebral fracture, which included all nonvertebral fracture except for major nonvertebral fracture, was assessed as a post hoc analysis. Fractures of the skull, face, metacarpus, finger, and toe phalanges as well as pathological fractures and those that were associated with severe trauma defined as a fall from a height higher than a stool, chair, or first rung of a ladder or severe trauma other than a fall were excluded (7).

Efficacy measures

Spine radiographs, antero-posterior and lateral, were taken at baseline and every 6 months over 24 months. To identify morphometrical vertebral fracture, the vertebral bodies of the lateral projection from Th4 to L4 were assessed using both the SQ and quantitative morphometry (QM) methods by the experts of the Central Committee who were blinded to treatment as previously reported (4, 5). Both SQ and QM requirements had to be met for prevalent vertebral fractures at baseline. A new vertebral fracture was defined as an increase of at least 1 SQ grading scale in a vertebral body that was normal at baseline and showing loss of height at the anterior, posterior, or central vertebra by at least 20% from baseline. A worsening fracture was defined in the same manner as a new vertebral fracture, with the above criteria applied to a vertebral body with a prevalent fracture. In cases of disagreement between SQ and QM methodologies, a binary SQ assessment was made to adjudicate the discordant results by the committee.

For assessment of nonvertebral fracture, investigators took radiographs at any time during the study to identify the fracture in a subject reporting clinical symptoms. The committee reviewed the radiographs in a blinded manner.

BMD as evaluated by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry was measured at the above-mentioned four sites at baseline and 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months except for the distal one third radius at 3 months. The QDR instrument (Hologic) was used in this study. Quality control and BMD scan analysis were performed centrally (Synarc).

Concentrations of the above two BTMs were measured from fasting serum samples collected in the morning around the same time at baseline and 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months before the administration of the IP. Serum CTX-1 and BSAP were evaluated by the central laboratory using an ELISA and chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay, respectively (Mitsubishi Chemical Medience Corp).

Adverse events (AEs)

All subjects were questioned concerning AEs at each visit, and all AEs were assessed, regardless of the determinations of causality by the investigators. The Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA, version 14.0) was used to categorize reported AEs. Safety laboratory tests including serum chemistry, hematology, and urinalysis were assessed at baseline and 1, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. Safety was assessed by recording all AEs, serious AEs, fatal AEs, AEs leading to study discontinuation, and AEs leading to discontinuation of IP. AEs of interests, such as hypocalcemia, bacterial cellulitis, infection, eczema, events potentially related to hypersensitivity, cardiovascular disorder, malignant or unspecified tumors, fracture healing complication, atypical fracture of femur, and osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), were prespecified. A dental expert in this study (T.Y.) reviewed each potential case of ONJ in a blinded manner. Study investigators clinically assessed the healing of nonvertebral fractures within 6 months after their occurrence. Antidenosumab binding antibodies were assessed in those samples of subjects randomized in the denosumab or placebo group.

Statistical analyses

This study had 90% power to detect a 50% reduction in new or worsening vertebral fracture in the denosumab group as compared with the placebo group, assuming a 16% incidence in the placebo group at 24 months and 20% subject discontinuation rate. The study was planned to enroll 440 subjects per double-blind treatment group (denosumab or placebo). The number of subjects for the alendronate group was set to be 220. Comparisons for alendronate vs. denosumab or placebo were post hoc analyses and not prespecified in the protocol.

Efficacy analyses were performed using the full analysis set, which includes all randomized subjects except for those who did not have osteoporosis at screening, did not receive the IP or had no available efficacy data after the first dose of the IP. All tests were performed at a two-sided 5% significant level, and all confidence intervals (CIs) are given as two-sided 95% CIs (α = .05).

The 24-month incidence of subjects with new or worsening vertebral, new vertebral, nonvertebral, major nonvertebral, and nonmajor nonvertebral fracture was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method with 95% CIs. A log-rank test was used to compare the incidence between the denosumab and placebo groups. A proportional hazard model was used to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs). The grouped survival data approach (8) was applied to the log-rank test and the estimation of the HR for the statistical analysis of vertebral fracture because most vertebral fractures were observed at the scheduled visits. The subgroup analyses in the women and men were conducted for new or worsening vertebral fracture and new vertebral fracture.

A Student's t test was used to compare the percentage changes from baseline in BMD between the denosumab and placebo groups. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the percentage changes from baseline in the BTMs between the denosumab and placebo groups.

The safety analysis set included all subjects who received at least one dose of IP, and AEs were summarized by the randomized treatment groups.

For the exploratory objective, the referential comparisons for the alendronate vs the denosumab or placebo group were conducted for fractures, BMD and BTMs using the same method as mentioned above.

Results

Subjects

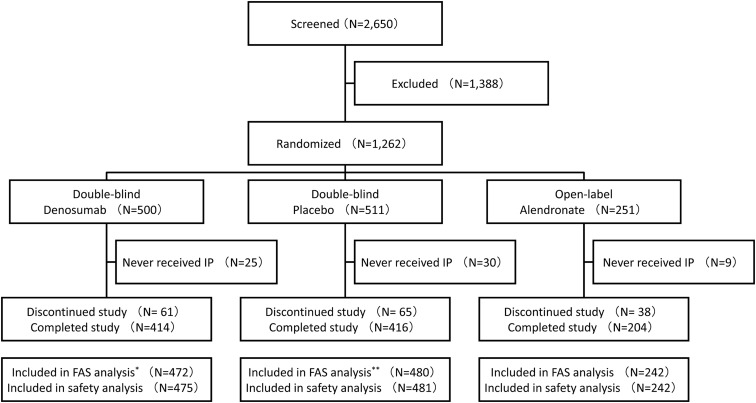

A total of 1262 subjects were randomized at 119 study sites, 500, 511, and 251 in the denosumab, placebo, and alendronate groups, respectively (Figure 1). The numbers of subjects who completed the study at 24 months were 414 (82.8%), 416 (81.4%), and 204 (81.3%), respectively.

Figure 1.

Disposition of study subjects. *, Three subjects were excluded due to lack of efficacy data after IP administration; **, one subject was excluded due to lack of efficacy data after IP administration. FAS, full analysis set.

Baseline characteristics of the subjects were similar across the three groups (Table 1). The proportion of subjects with at least one vertebral fracture at baseline was 98.3%. The mean BMD T-score at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck was −2.74, −1.98 and −2.32, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Subjects

| Double Blind |

Open Label |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Denosumab (n = 472) | Placebo (n = 480) | Alendronate (n = 242) | |

| Gender, n, % | |||

| Female | 449 (95.1) | 456 (95.0) | 230 (95.0) |

| Male | 23 (4.9) | 24 (5.0) | 12 (5.0) |

| Age, y | |||

| Mean-yeara | 69.9 ± 7.36 | 69.0 ± 7.67 | 70.2 ± 7.31 |

| Group, n, % | |||

| <65 | 99 (21.0) | 126 (26.3) | 56 (23.1) |

| 65–74 | 246 (52.1) | 231 (48.1) | 112 (46.3) |

| ≥75 | 127 (26.9) | 123 (25.6) | 74 (30.6) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2a | 22.6 ± 2.9 | 22.4 ± 3.1 | 22.3 ± 3.0 |

| Prevalent vertebral fractures, n, % | |||

| 0 | 6 (1.3) | 9 (1.9) | 5 (2.1) |

| 1 | 315 (66.7) | 319 (66.5) | 157 (64.9) |

| 2 | 113 (23.9) | 105 (21.9) | 62 (25.6) |

| ≥3 | 38 (8.1) | 47 (9.8) | 18 (7.4) |

| T-scorea | |||

| Lumbar spine (L1-L4) | −2.78 ± 0.89 | −2.73 ± 0.88 | −2.69 ± 0.94 |

| Total hip | −2.01 ± 0.79 | −1.95 ± 0.73 | −1.96 ± 0.79 |

| Femoral neck | −2.38 ± 0.70 | −2.29 ± 0.71 | −2.29 ± 0.69 |

| Serum CTX-1, ng/mLb | 0.64 (0.44, 0.78) | 0.63 (0.43, 0.78) | 0.61 (0.42, 0.77) |

| Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, ng/mLa | 20.97 ± 6.08 | 20.63 ± 5.91 | 21.10 ± 6.30 |

Twenty subjects were originally assessed as having one or more vertebral fractures during an initial single reviewer assessment, and subsequent blinded adjudication by the committee determined that no prevalent vertebral fracture was present at baseline. Subjects were excluded if they had less than 12 ng/mL serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration at screening.

Data are mean ± SD.

Data are mean (quartiles 1 and 3).

Consequently, five subjects (two, one, and two in the denosumab, placebo, and alendronate groups, respectively) were not classified as osteoporosis based on the diagnostic criteria in Japan.

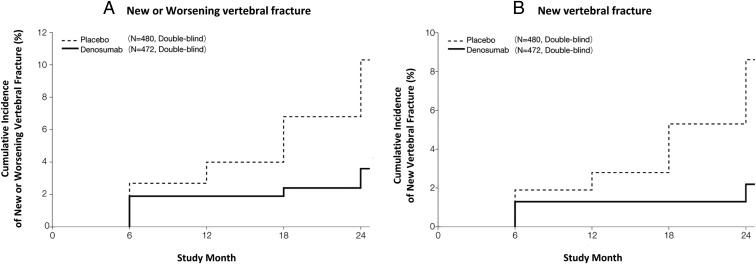

Fractures

The 24-month incidence of new or worsening vertebral fracture was 3.6% in the denosumab group and 10.3% in the placebo group, with the reduction in risk by 65.7% (P = .0001) (Figure 2A and Supplemental Table 1). In the subgroup analysis in women, the risk of new or worsening vertebral fracture at 24 months was reduced by 63.2% in the denosumab group compared with the placebo group (HR 0.368, 95% CI 0.207–0.653, P = .0004). The 24-month incidence of new vertebral fracture was 2.2% in the denosumab group and 8.6% in the placebo group, with the reduction in risk by 74.0% (P < .0001) (Figure 2B). In the subgroup analysis in women, the risk of new vertebral fracture at 24 months was reduced by 72.6% in the denosumab group compared with the placebo group (HR 0.274, 95% CI 0.136–0.553, P = .0001).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of vertebral fracture. The cumulative incidence of new or worsening vertebral fracture (A) and new vertebral fracture (B) in all subjects in the denosumab and placebo groups. For panels A and B, the percentages given were incidence by the Kaplan-Meier estimate over a 24-month treatment period. The HR (95% CI) and P value of new or worsening vertebral fracture (A) for the denosumab vs the placebo group was 0.343 (0.194, 0.606) and P = .0001. The HR (95% CI) and P value of a new vertebral fracture (B) for the denosumab vs placebo group was 0.260 (0.129, 0.521) and P < .0001. In the subgroup analysis in men at 24 months, the incidence of new or worsening vertebral fracture in the denosumab and placebo groups was 0% and 12.5%, respectively, and that of new vertebral fracture in the denosumab and placebo groups was 0% and 8.3%, respectively. The P value of a new or worsening vertebral fracture and new vertebral fracture for the denosumab vs placebo group was P = .0748 and P = .1478, respectively. The HRs (95% CI) were not estimated because there were no subjects with a vertebral fracture in the denosumab group.

The 24-month incidence of nonvertebral fracture was 4.1% in both the denosumab and placebo groups (P = .9951). The 24-month incidence of major nonvertebral fracture was 1.6% and 3.7% in the denosumab and placebo groups, respectively (P = .0577). The 24-month incidence of nonmajor nonvertebral fracture was 2.5% and 0.4% in the denosumab and placebo groups, respectively (P = .0120).

In the alendronate group, the 24-month incidence of new or worsening vertebral, new vertebral, nonvertebral, major nonvertebral, and nonmajor nonvertebral fracture was 7.2%, 5.1%, 2.7%, 2.3%, and 0.4%, respectively. As the referential comparison, the HR (95% CI) and the P value of new vertebral fracture for the alendronate vs placebo group was 0.641 (0.335, 1.226) and P = .1749, and for the denosumab vs alendronate group was 0.416 (0.180, 0.962) and P = .0344.

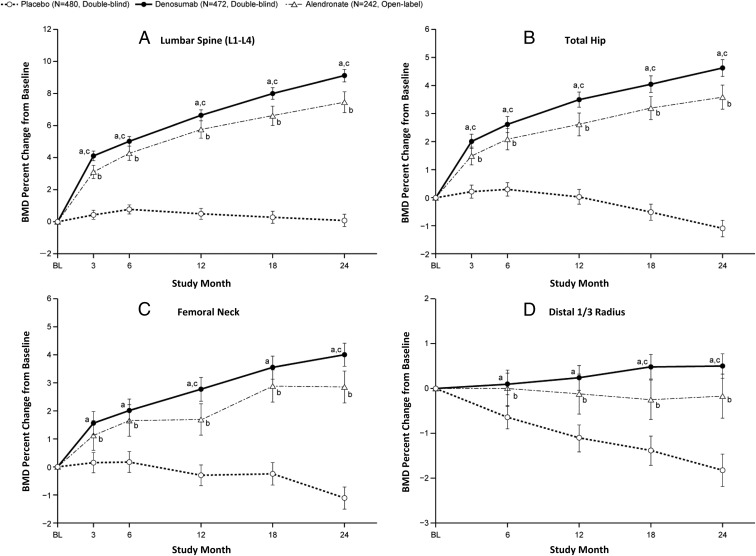

Bone mineral density

Mean BMD percentage change from baseline at 24 months was 9.1% and 0.1% at the lumbar spine in the denosumab and placebo groups, 4.6% and −1.1% at the total hip, 4.0% and −1.1% at the femoral neck, and 0.5% and −1.8% at distal one third radius, respectively (Figure 3, A–D). The difference between the two groups was significant as early as 3 months at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck (P < .0001) and 6 months at the distal one third radius (P < .0001).

Figure 3.

Mean BMD percentage changes from baseline. Mean BMD percentage changes from baseline over a 24-month treatment period at the lumbar spine (L1–L4) (A), total hip (B), femoral neck (C), and distal one third radius (D) are shown. a, P < .0001 based on the Student's t test at each time point for the denosumab vs placebo group; b, a referential comparison, P < .01 based on the Student's t test at each time point for the alendronate vs placebo group; c, P < .05 based on the Student's t test at each time point for the denosumab vs alendronate group. The bars show 95% CIs of the mean values at each time point. A central vender performed all BMD analyses. Abnormal vertebrae, such as those with an abnormality, fracture, or artifact, were excluded from analyses.

In the alendronate group, the mean BMD percentage change from baseline at 24 months was 7.5%, 3.6%, 2.9%, and −0.2% at the lumbar spine, total hip, femoral neck, and distal one third radius, respectively. As the referential comparison, the difference between the alendronate and placebo groups was significant as early as 3 months at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck (P < .01) and 6 months at the distal one third radius (P < .01). The difference between the denosumab and alendronate groups was significant as early as 3 months at the lumbar spine and total hip (P < .05), at 12 and 24 months at the femoral neck (P < .05), and from 18 months at the distal one third radius (P < .05).

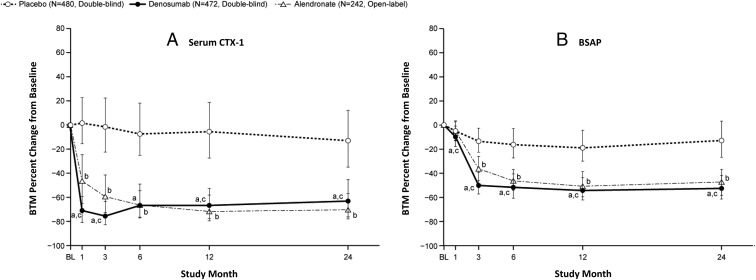

Bone turnover markers

The median percentage change from baseline in serum CTX-1 and BSAP in the denosumab group was reduced by 70.9% at 1 month and 50.2% at 3 months, respectively, and maintained significant reduction levels thereafter (Figure 4, A and B). The difference in serum CTX-1 and BSAP between the denosumab and placebo groups was significant as early as 1 month (P < .0001).

Figure 4.

Median BTM percentage changes from baseline. Median BTM changes from baseline over a 24-month treatment period for serum CTX-1 (A) and serum BSAP (B) are shown. a, P < .0001 based on the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for the denosumab vs placebo group; b, as a referential comparison, P < .01 based on the Wilcoxon rank-sum test at each time point for the alendronate vs placebo group; c, P < .05 based on the Wilcoxon rank-sum test at each time point for the denosumab vs alendronate group. The bars show the interquartile range of the percentage changes from baseline at each time point.

In the alendronate group, the median percentage change from baseline in serum CTX-1 and BSAP was reduced by 66.3% and 46.4%, respectively, at 6 months and maintained these reduction levels after 6 months. As the referential comparison, the difference between the alendronate and placebo groups was significant as early as 1 month in serum CTX-1 (P < .01) and as early as 3 months in serum BSAP (P < .05), respectively. The difference in serum CTX-1 and BSAP between the denosumab and alendronate groups was significant as early as 1 month (P < .05), except at 6 months in serum CTX-1.

Safety

No differences were found in all AEs, serious AEs, fatal AEs, or AEs leading to discontinuation among the denosumab, placebo and alendronate groups during the first 24 months of the study (Table 2). The incidences of AEs of interest and serious AEs including hypocalcemia, bacterial cellulitis, infection, eczema, malignant or unspecified tumors, hypersensitivity, or cardiovascular disorder were not different among the groups. The most frequent infections were nasopharyngitis (44.4%, 42.2%, and 38.4% in the denosumab, placebo, and alendronate groups, respectively) and cystitis (5.9%, 6.0%, and 3.7%, respectively). These infections were all mild in severity. Two subjects in both the denosumab and alendronate groups experienced biochemical hypocalcemia without clinical symptoms. No cases of delayed fracture healing, ONJ, or atypical fracture of the femur were reported in any of the treatment groups. No subjects developed neutralizing antibodies to denosumab in the denosumab or placebo groups.

Table 2.

Summary of Adverse Events

| Adverse event | Double blind |

Open label |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Denosumab (n = 475), n, % | Placebo (n = 481), n, % | Alendronate (n = 242), n, % | |

| All | 448 (94.3) | 446 (92.7) | 229 (94.6) |

| Serious | 66 (13.9) | 68 (14.1) | 30 (12.4) |

| Fatal | 5 (1.1) | 5 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Leading to study discontinuation | 5 (1.1) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.8) |

| Leading to discontinuation of IP | 23 (4.8) | 31 (6.4) | 18 (7.4) |

| AEs of interest | |||

| Hypocalcemia | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.8) |

| Bacterial cellulitis | 6 (1.3) | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Infection | 286 (60.2) | 269 (55.9) | 131 (54.1) |

| Eczema | 70 (14.7) | 81 (16.8) | 31 (12.8) |

| Potentially related to hypersensitivity | 90 (18.9) | 105 (21.8) | 45 (18.6) |

| Cardiovascular disorder | 68 (14.3) | 63 (13.1) | 21 (8.7) |

| Malignant or unspecified tumors | 9 (1.9) | 11 (2.3) | 2 (0.8) |

| Fracture healing complication | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| ONJ | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Atypical femoral fracture | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Serious AEs of interest | |||

| Hypocalcemia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Bacterial cellulitis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Infection | 5 (1.1) | 7 (1.5) | 3 (1.2) |

| Eczema | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Potentially related to hypersensitivity | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Cardiovascular disorder | 6 (1.3) | 7 (1.5) | 2 (0.8) |

| Malignant or unspecified tumors | 7 (1.5) | 10 (2.1) | 2 (0.8) |

The analysis of AEs included those of all subjects who received at least one dose of IP. Reported AEs were coded by using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 14.0.

Discussion

Denosumab 60 mg sc every 6 months for 24 months significantly decreased the risk of new or worsening vertebral fractures by 65.7% compared with placebo in Japanese subjects with osteoporosis. Subsequent post hoc sensitivity analyses showed that these results were not affected by the presence of a small number of subjects who were not classified as osteoporosis (data not shown). The reduction in the risk of vertebral fracture in postmenopausal women was significant and similar to that observed in the overall population. The incidence of new or worsening vertebral and new vertebral fracture in older men in the denosumab group was lower than that in the placebo group, although the difference in these incidences did not reach statistical significance, possibly due to the small sample size (Figure 2).

The risk reduction of denosumab on vertebral fracture to placebo in Japanese women with postmenopausal osteoporosis is similar to that observed in FREEDOM, including predominantly Caucasian postmenopausal women (1, 2). The HR (95% CI) for new or worsening vertebral fracture (denosumab vs placebo) in postmenopausal women in DIRECT was 0.37 (0.21–0.65) at 24 months. The risk ratio (95% CI) for the new or worsening vertebral fracture (denosumab vs placebo) in postmenopausal women in FREEDOM was 0.29 (0.21–0.39) at 24 months (9). The 95% CI was narrower in FREEDOM due to the larger sample size than DIRECT, but the range of CIs of the two studies overlap considerably. Thus, the efficacy of denosumab on the relative risk reduction of vertebral fracture in postmenopausal osteoporosis is consistent between Japanese and predominantly Caucasian women.

Results of the analysis on the incidence of nonvertebral fractures were complex: the incidence of total nonvertebral fracture was similar between the denosumab and placebo groups; there was a trend for a lower incidence of major nonvertebral fracture in the denosumab group compared with the placebo group; and the incidence of nonmajor nonvertebral fracture was higher in the denosumab group compared with the placebo group. The risk of nonvertebral fracture was consistently lower in the denosumab group compared with the placebo group at 2 and 3 years in FREEDOM (1). The incidence of nonvertebral fracture in the denosumab group in DIRECT (4.1%) was apparently similar to that in FREEDOM. Therefore, the difference in the effect of denosumab on the risk of nonvertebral fracture between DIRECT and FREEDOM is unlikely due to the low incidence of nonvertebral fracture in Japanese subjects, but it may be related to the smaller sample size of DIRECT, as compared with FREEDOM.

The gains of BMD from baseline at the lumbar spine, total hip, and femoral neck in this study were comparable with those in FREEDOM and other studies (1, 10). In DIRECT, however, the BMD gain from baseline at the distal one third radius with denosumab was 0.5% on average at 24 months, smaller than the gains of 1.0%–2.0% on average observed in other studies. At the distal one third radius, the BMD loss in the placebo group was −1.8% on average at 24 months in DIRECT. Thus, the difference in the mean values at the distal one third radius between the denosumab and placebo groups was 2.3%, which is comparable with the gains obtained by denosumab compared with placebo in the trials of predominantly Caucasian women during the period of 2 years (10). Changes in BTMs in this study were similar to the effects of denosumab reported in previous studies in Caucasians postmenopausal women with low bone mass (10) and Japanese postmenopausal women with osteoporosis (3).

The 24-month treatment with denosumab was well tolerated. No apparent differences in the AEs of the interest were observed between the denosumab and placebo groups.

The results of the BMD and BTMs as a referential comparison for the alendronate vs denosumab or placebo group were consistent with previous studies (11–13). The HR for new vertebral fracture between the alendronate and placebo groups in DIRECT (0.641) was within the range of 95% CI (0.41–0.68) observed in the Fracture Intervention Trial (14). The apparent lower incidence of vertebral fracture in the denosumab group compared with the alendronate group may be related to the earlier spine BMD increase and stronger inhibition of bone resorption by denosumab but also to use of the alendronate dosage approved in Japan, which is half the dosage used in the United States. The incidence of nonmajor nonvertebral fracture was numerically higher in the denosumab group than the alendronate group. This difference may be caused by the relatively small sample size, and is unlikely to be clinically significant due to inconsistency of the results of the vertebral fracture, BMD, and BTMs. No apparent difference in the safety profile was observed between the denosumab and alendronate groups. Therefore, denosumab could be used safely in the treatment of osteoporosis for Japanese patients, as is alendronate.

This study included a relatively small number of subjects, and the study duration was only 24 months, which may have limited the ability to detect rare AEs such as hypocalcemia, bacterial cellulitis, and ONJ. The study was also underpowered to test the efficacy of denosumab on the prevention of nonvertebral and hip fracture. The interpretation of the results of the referential comparison for alendronate vs denosumab or placebo is limited by the fact that this study was not designed to assess the difference in fracture incidence between the alendronate and denosumab or placebo groups. In addition, the alendronate dosage that was used in this study, ie, 35 mg weekly, which is approved in Japan, is different from the globally approved dose of 70 mg weekly.

In conclusion, denosumab 60 mg every 6 months significantly reduced the risk of vertebral fracture in Japanese subjects with osteoporosis who had existing mild or moderate vertebral fractures. These results provide evidence for the efficacy and safety of denosumab 60 mg sc every 6 months in the treatment of Japanese subjects with osteoporosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank the investigators of the study. We also acknowledge the assistance of Amgen for editorial assistance on the manuscript.

The clinical trial registration number identifier (clinicaltrials.gov) is NCT00680953.

This work was supported by Daiichi-Sankyo Co Ltd, Tokyo, Japan.

Disclosure Summary: T.Nakam. has received consulting fees from Teijin Pharma, Daiichi-Sankyo Co, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co, Asahi-Kasei Pharma Co, MSD K.K., and Amgen Inc. T.Matsu. has received consulting fees from Daiichi-Sankyo Co, Ono Pharmaceutical Co, Asahi-Kasei Pharma Co, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co, and Teijin Pharma and research grants from MSD, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Astellas Pharma. T.Su. has received consulting fees from Asahi-Kasei Pharma Co, and Daiichi-Sankyo Co. T.H. and T.Mi. have received consulting fees from Daiichi-Sankyo Co. I.G. has received consulting fees from Daiichi-Sankyo Co and speaker's bureau from MSD, Eli Lilly Japan, Pfizer, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co, Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical Co, and Ono Pharmaceutical Co. H.Y. has received consulting fees from Ono Pharmaceutical Co, Asahi-Kasei Pharma Co, and Eisai; he has also received speaker's bureau from Asahi-Kasei Pharma Co, Ono Pharmaceutical Co, Astellas Pharma, and Eli Lilly Japan. Y.T. has received consulting fees from Mitsubishi-Tanabe Pharma, Otsuka Pharma, Pfizer, Eli Lilly Japan, Astellas Pharma, Janssen Pharma, Astra-Zeneca, Mitsubishi-Tanabe Pharma, Abbott Japan, MSD, Daiichi-Sankyo Co, GlaxoSmithKline, Actelion Pharma Japan, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co, Eisai, and Santen Pharma; he has also received research grants from Eisai, Pfizer, Janssen Pharma, Astellas Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Abbott Japan, and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. S.T. has received speaker's bureau from Eli Lilly Japan, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Eisai, Santen Pharmaceutical, Teijin Pharma, Nippon Zoki, Johnson & Johnson, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co, Daiichi-Sankyo Co, Ono Pharmaceutical Co, GSK, Pfizer, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Hisamitsu Pharmaceutical, Asahi Kasei Pharma, Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical, Astellas Pharma, and Otsuka Pharmaceutical; he has also received consulting fees from Eisai, Astellas Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Asashi Kasei Pharma, Ono Pharmaceutical Co, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, and Kaken Pharmaceutical and research grants from Sanofi Aventis, Daiichi-Sankyo Co, and MSD. T.So. has received research grants from Daiichi-Sankyo Co, Astellas Pharma, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical Co, and Pfizer and speaker's bureau from Daiichi-Sankyo Co, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co, MSD, Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical Co, Pfizer, and Eli Lilly Japan. T.Nakan. has received consulting fees from Asahi-Kasei Pharma, Teijin Pharma, Daiichi-Sankyo Co, and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. M.I. has received consulting fees from Asahi-Kasei Pharma, Daiichi-Sankyo Co, and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. T.Y. has received consulting fees from Daiichi-Sankyo Co. S.M. has received consulting fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co, Daiichi-Sankyo Co, Eisai Co, and Takada Pharmaceutical. H.T., K.W., and T.O. are Daiichi-Sankyo's employee and own Daiichi-Sankyo Co stock. M.S. has received consulting fees from Daiichi-Sankyo Co, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co, Teijin Pharma, Asahi-Kasei Pharma Co, and MSD. M.F. has received consulting fees from Asahi-Kasei Pharma Co and Astellas Pharma Co.

Footnotes

- AE

- adverse event

- BMD

- bone mineral density

- BSAP

- bone-specific alkaline phosphatase

- BTM

- bone turnover marker

- CI

- confidence interval

- CTX-1

- C-telopeptide of type 1 collagen

- DIRECT

- Denosumab fracture Intervention RandomizEd placebo Controlled Trial

- FREEDOM

- Fracture REduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis every 6 Months

- HR

- hazard ratio

- IP

- investigational product

- ONJ

- osteonecrosis of the jaw

- QM

- quantitative morphometry

- SQ

- semiquantitative.

References

- 1. Cummings SR, Martin JS, McClung MR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:756–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McClung MR, Boonen S, Torring O, et al. Effect of denosumab treatment on the risk of fractures in subgroups of women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:211–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nakamura T, Matsumoto T, Sugimoto T, Shiraki M. Dose-response study of denosumab on bone mineral density and bone turnover markers in Japanese postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Osteoporosis Int. 2012;23:1131–1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Orimo H, Sugioka Y, Fukunaga M, et al. The Committee of the Japanese Society for Bone and Mineral Research for Development of Diagnostic Criteria of Osteoporosis. Diagnostic criteria of primary osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Metab. 1998;16:139–150 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Genant HK, Jergas M, Palermo L, et al. Comparison of semiquantitative visual and quantitative morphometric assessment of prevalent and incident vertebral fractures in osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:984–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kanis JA, on behalf of the World Health Organization Scientific Group. Assessment of osteoporosis at the primary health-care level. Technical report. World Health Organization Collaborating Centre. Sheffield, UK: University of Sheffield; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stone KL, Seeley DG, Lui LY, et al. BMD at multiple sites and risk of fracture of multiple types: long-term results from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1947–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prentice RL, Gloeckler LA. Regression analysis of grouped survival data with application to breast cancer data. Biometrics. 1978;34:57–67 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Austin M, Yang Y-C, Vittinghoff E, et al. Relationship between bone mineral density changes with denosumab treatment and risk reduction for vertebral and nonvertebral fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:687–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lewieck EM, Miller PD, McClung MR, et al. Two-year treatment with denosumab (AMG162) in a randomized phase 2 study of postmenopausal women with low BMD. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1832–1841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brown JP, Prince RL, Deal C, et al. Comparison of the effect of denosumab and alendronate on BMD and biochemical markers of bone turnover in postmenopausal women with low bone mass: a randomized, blinded, phase 3 trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:153–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Uchida S, Taniguchi T, Shimizu T, et al. Therapeutic effects of alendronate 35 mg once weekly and 5 mg once daily in Japanese patients with osteoporosis: a double-blind, randomized study. J Bone Miner Metab. 2005;23:382–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kushida K, Shiraki M, Nakamura T, et al. Alendronate/Alfacalcidol Fracture Intervention Study Group. The efficacy of alendronate in reducing the risk for vertebral fracture in Japanese patients with osteoporosis: a randomized, double-blind, active-controlled, double-dummy trial. Curr Ther Res. 2002;606–620 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, et al. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Lancet. 1996;1535–1541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]