Significance

Bacteria coordinate behavior through production, release, and detection of chemical signals called autoinducers. While most are species-specific, autoinducer-2 is used by many species and facilitates interspecies communication. Because many important behaviors, including virulence and biofilm formation, are thus regulated, methods for interfering with this communication are regarded as promising alternatives to antibiotics. Some bacteria can manipulate levels of autoinducer-2 in the environment, interfering with the communication of other species. Here we characterize the terminal step in the pathway that Escherichia coli uses to destroy this signal via a novel catalytic mechanism, and identify products that link quorum sensing and primary cell metabolism.

Keywords: cell–cell signaling, quorum quenching, bacterial communication, metabolic flux

Abstract

The quorum sensing signal autoinducer-2 (AI-2) regulates important bacterial behaviors, including biofilm formation and the production of virulence factors. Some bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, can quench the AI-2 signal produced by a variety of species present in the environment, and thus can influence AI-2–dependent bacterial behaviors. This process involves uptake of AI-2 via the Lsr transporter, followed by phosphorylation and consequent intracellular sequestration. Here we determine the metabolic fate of intracellular AI-2 by characterizing LsrF, the terminal protein in the Lsr AI-2 processing pathway. We identify the substrates of LsrF as 3-hydroxy-2,4-pentadione-5-phosphate (P-HPD, an isomer of AI-2-phosphate) and coenzyme A, determine the crystal structure of an LsrF catalytic mutant bound to P-HPD, and identify the reaction products. We show that LsrF catalyzes the transfer of an acetyl group from P-HPD to coenzyme A yielding dihydroxyacetone phosphate and acetyl-CoA, two key central metabolites. We further propose that LsrF, despite strong structural homology to aldolases, acts as a thiolase, an activity previously undescribed for this family of enzymes. With this work, we have fully characterized the biological pathway for AI-2 processing in E. coli, a pathway that can be used to quench AI-2 and control quorum-sensing–regulated bacterial behaviors.

Cell–cell communication is widespread in the bacterial world. In a process called quorum sensing, bacteria produce, secrete, and accumulate small signal molecules called autoinducers that, upon detection, trigger a response at the level of gene expression. This process enables bacteria in a population to synchronize their actions and engage in group behaviors. Many bacteria use quorum sensing to regulate important behaviors, such as the formation of biofilms and production of virulence factors, which are often essential processes in bacteria–host interactions (1, 2). Given the number of pathogenic bacteria that are known to use quorum sensing to regulate virulence, strategies to interfere with quorum sensing are considered promising alternatives to traditional antibiotics (3, 4).

Most quorum-sensing systems are species-specific, mediated by N-acyl-homoserine lactones in Gram-negative bacteria and modified oligopeptides in Gram-positive species (5, 6). A third quorum-sensing system, mediated by autoinducer-2 (AI-2, 1 in Fig. 1), is present in both Gram-negative and -positive bacteria (7–9) and has been shown to facilitate interspecies communication, as evidenced by changes in gene expression of one species in response to signal produced by another in coculture (10). For this reason, we expect that, in environments where multiple species of bacteria coexist and interact, interfering with AI-2–mediated signaling is likely to be more effective in controlling bacterial behaviors than targeting species-specific signals (9). One strategy for controlling AI-2–regulated bacterial behaviors is to manipulate the concentration (or availability) of this molecule. A number of bacteria, including Escherichia coli, have a system (named Lsr) that internalizes and processes AI-2 (11–16). These bacteria use the Lsr system to remove AI-2 from the environment, eliminating the ability of others to use this signal to regulate their behaviors (10, 17).

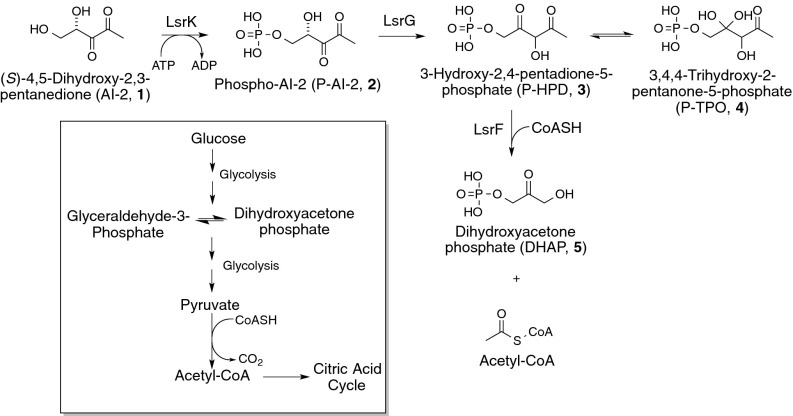

Fig. 1.

Processing and fate of AI-2 in E. coli. Once internalized, AI-2 (1) is phosphorylated to P-AI-2 (2) by LsrK. LsrG then catalyzes the isomerization of P-AI-2 to P-HPD (3) [which exists in equilibrium with its hydrated form, P-TPO (4)]. In the terminal step of processing, LsrF catalyzes the transfer of an acetyl group from P-HPD to CoASH, yielding acetyl-CoA and DHAP. These products are both key central metabolites (Inset) and are used by the cell in a variety of pathways such as glycolysis and the citric acid cycle.

We have shown that once AI-2 is internalized by the Lsr transporter it is phosphorylated to AI-2-phosphate (P-AI-2, 2 in Fig. 1) by the kinase LsrK (18). Phosphorylation is essential for sequestration of the signal in the cytoplasm and consequent depletion from the extracellular medium (18, 19). P-AI-2 can induce further transcription of the lsr operon by inhibiting the repressor LsrR and consequently increasing the expression of the transporter and the kinase (18, 20–24). Termination of lsr expression is caused by LsrG, an enzyme that catalyzes the isomerization of P-AI-2 to 3-hydroxy-2,4-pentadione-5-phosphate (P-HPD, 3 in Fig. 1), which exists in equilibrium with its hydrated form 3,4,4-trihydroxy-2-pentanone-5-phosphate (P-TPO, 4 in Fig. 1) (25). Previous genetic studies in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium demonstrated that mutants in lsrF, another gene in the lsr operon, also show increased expression of the lsr operon, thus indicating that LsrF is involved in processing P-AI-2 or the products of the LsrG reaction (26). Additionally, analysis of a crystal structure of LsrF revealed strong structural homology with class I aldolases (27) (which cleave C–C bonds in a variety of phosphorylated carbohydrates); no activity toward P-AI-2 was detected in in vitro LsrF assays, however, and the function of LsrF, as well as the metabolic fate of P-AI-2, remained unknown.

Here we present genetic, biochemical, and structural evidence that LsrF is involved in the pathway of P-AI-2 processing. We show that LsrF, despite having strong structural homology with class I aldolases, does not simply cleave P-AI-2 as would an aldolase but rather catalyzes the transfer of an acetyl group from the P-AI-2 isomer P-HPD to the obligate second substrate coenzyme A (CoASH), producing dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and acetyl-CoA. This thiolase activity, in which bond cleavage is mediated by nucleophilic attack by a -SH group, has not, to our knowledge, previously been reported for homologs to class I aldolases.

The products of the LsrF reaction, DHAP and acetyl-CoA, play a number of key cellular roles, most notably as intermediates of central metabolism [glycolysis and the Krebs cycle, respectively (Fig. 1)]. The identification of these products completes the characterization of the metabolic pathway involved in processing AI-2 in E. coli, a pathway that provides a biological means for quenching AI-2–mediated interspecies signaling (10, 17).

Results

LsrF Is Involved in the Pathway of P-AI-2 Processing.

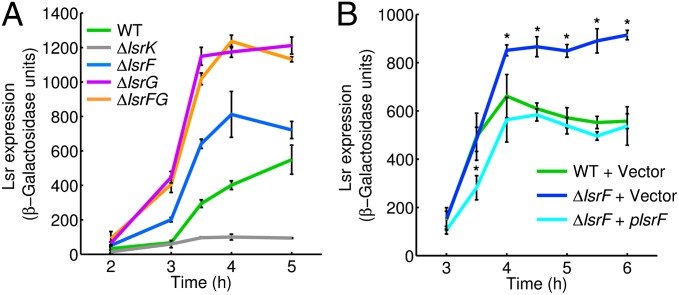

The lsr promoter is activated by P-AI-2, and thus transcription from this promoter (determined using a chromosomal lsr–lacZ promoter reporter fusion) can be used as a measure of accumulation of intracellular P-AI-2 (19, 25). As shown in Fig. 2A, the E. coli lsrF mutant shows higher lsr-lacZ transcription than the WT strain. This increase is also observed with the lsrG mutant, which accumulates high levels of intracellular P-AI-2, as we previously demonstrated (25). No expression is detected in the kinase mutant (ΔlsrK) that cannot make P-AI-2. Additionally, complementation of the lsrF mutant with an isopropyl-1-thio-d-galactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible multicopy plasmid expressing the lsrF-WT gene causes reduction of lsr-lacZ expression (ΔlsrF + plsrF in comparison with the vector control; cyan and blue lines, respectively, in Fig. 2B). lsr-lacZ expression in the complemented strain is similar to the WT, except at early time points, when LsrF expression is induced by IPTG in the ΔlsrF + plsrF strain but AI-2 levels are too low to induce it in the WT. These results provide strong evidence that deletion of the lsrF gene leads directly or indirectly to the accumulation of P-AI-2. Additionally, because expression in the lsrG single or lsrFG double mutants is higher than in the lsrF single mutant (Fig. 2A), we predicted that LsrF would act downstream of LsrG.

Fig. 2.

Expression of the lsr operon in E. coli is increased in the lsrF mutant. Time-course β-galactosidase activity of the lsr-lacZ transcription reporter fusion were determined at the indicated times. (A) WT (KX1123, green line), ΔlsrF (JCM22, blue line), ΔlsrG (JCM23, pink line), ΔlsrFG (KX1464, orange line), and ΔlsrK (KX1186, gray line). (B) For complementation studies, lsr-lacZ expression was measured in WT (JCM101, green line) and ΔlsrF (JCM102, blue line) carrying the empty vector ptrc99a and ΔlsrF containing the vector carrying WT lsrF (JCM119, cyan line). The error bars indicate SDs (Mann–Whitney test, *P < 0.05, n = 6).

In agreement with these expectations, we also observed that cell lysates from WT E. coli metabolize P-AI-2, whereas this metabolite accumulates in lysates from either the lsrG or lsrFG mutants. In ΔlsrF cell lysates P-AI-2 is consumed and the products of LsrG (P-HPD and its hydrated form P-TPO) accumulate (Fig. S1). These results strongly suggest that LsrF functions in the pathway for processing of P-AI-2 downstream of LsrG.

LsrF Catalyzes the Transfer of the Acetyl Group of P-HPD to CoASH.

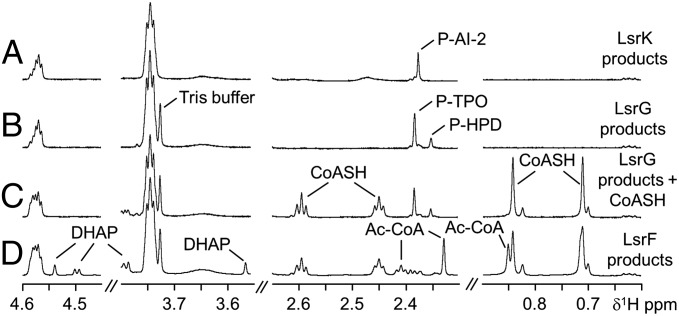

Given the high sequence and structural homology between LsrF and class I aldolases (27), we predicted that LsrF would cleave metabolites in the pathway of AI-2 processing. To characterize the reaction catalyzed by LsrF, we tested the ability of LsrF to act on AI-2, P-AI-2, P-HPD, and P-TPO. NMR was used to detect changes in these substrates or the appearance of reaction products. Incubation of purified LsrF with any of these substrates resulted in no spectral changes, even when tested in the presence of different metal ions and cofactors (Table S1). To explore the possibility that LsrF instead has transaldolase activity, we next tested the activity of LsrF in the presence of AI-2 (or its phosphorylated adducts) and a variety of potential additional cosubstrates, including aldehydes that are frequent substrates in transaldolase reactions (Table S1). Surprisingly, we found that only when CoASH was added to the reaction mixture could LsrF act on the products of the LsrG-catalyzed reaction (P-HPD/P-TPO); activity was not observed for any other of the substrates tested. 1H-NMR spectra of the relevant reaction mixtures are shown in Fig. 3. Trace A in Fig. 3 shows the spectra of P-AI-2 obtained upon incubation of chemically synthesized AI-2 with LsrK and ATP. Addition of LsrG (trace B in Fig. 3) leads to the conversion of P-AI-2 into P-HPD, which is in equilibrium with its hydrated form P-TPO. Trace C in Fig. 3 shows the resonances after addition of CoASH at time 0, and trace D shows the appearance of new resonances upon incubation (for 4 min) of the reaction mixture with LsrF, as well as the commensurate decrease of the resonances from P-HPD, P-TPO, and CoASH. The new resonances were assigned to DHAP and acetyl-CoA by spiking this reaction mixture with commercially obtained DHAP and acetyl-CoA as standards (Fig. S2). We conclude that LsrF catalyzes the transfer of an acetyl group from the P-AI-2 isomer produced by LsrG to CoASH, yielding DHAP and acetyl-CoA (Fig. 1).

Fig. 3.

1H-NMR spectra of the substrates and products of the LsrF reaction. Trace A shows the proton resonances of P-AI-2 resulting from incubation of AI-2 with purified LsrK and ATP. Addition of LsrG to this reaction mixture resulted in the production of P-HPD and its hydrated form P-TPO (resonances shown in trace B). Trace C shows the spectrum of the same mixture after addition of CoASH. Trace D is the spectrum after incubating the mixture in C with the LsrF protein for 4 min. The new resonances detected in trace D were assigned to DHAP and acetyl-CoA (Ac-CoA), which were thus identified as the products of the LsrF reaction. Resonances for the methyl groups of P-AI-2, P-TPO, and P-HPD, as well as the resonances of CoASH, acetyl-CoA and DHAP are highlighted.

In Vitro Assay to Measure LsrF Activity and Kinetic Parameters.

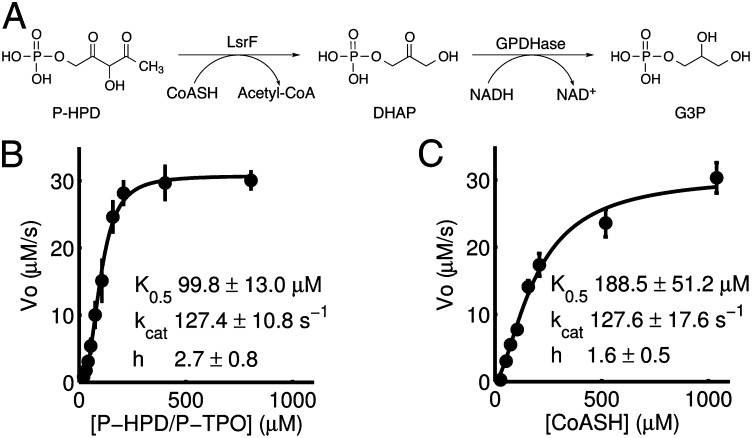

To determine the kinetic constants of the LsrF catalyzed reaction, we established a continuous assay to monitor its activity. In this assay, DHAP production was coupled to the oxidation of NADH via glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDHase) as shown in Fig. 4A. The consumption of NADH, measured at 340 nm, was thus used to calculate the initial velocity of the LsrF reaction, a method similar to that used by Janda and colleagues (28) to quantify LsrK activity. The specific activity of LsrF was 0.76 ± 0.01 U/mg (1 U = 1 μmol⋅min−1 DHAP produced) (Table S2). To determine the apparent kinetic constants for P-HPD/P-TPO and CoASH, the initial velocities were determined at varied concentrations of each of the substrates in the presence of saturating concentrations of the other (Fig. 4 B and C). The Michaelis–Menten and Hill equations were fitted to the data and the goodness of fit was evaluated by the Bayesian information criteria, Akaike information criteria, and adjusted coefficient of determination (29). In all cases the Hill equation showed a better fit (Table S3). As shown in Fig. 4 B and C, LsrF possesses a positive Hill constant (h) for both CoASH and P-HPD, indicating positive cooperativity, a common feature of multimeric enzymes such as LsrF (27). The obtained kinetic constants for the reaction (Fig. 4 B and C) are in agreement with the reported range of E. coli type I aldolases (30).

Fig. 4.

Kinetics of LsrF with P-HPD and CoASH as substrates. (A) The LsrF catalyzed acylation of CoASH and the coupled GPDHase reaction was used to measure DHAP production. G3P, glycerol-3-phosphate. (B and C) Velocity curves of DHAP production at varying concentration of P-HPD/P-TPO and CoASH. Kinetic constants for P-HPD (B) and CoASH (C) were determined by fitting initial velocities to the Hill equation (solid line). Error bars represent SD (n = 5).

Structure of LsrF in Complex with P-HPD.

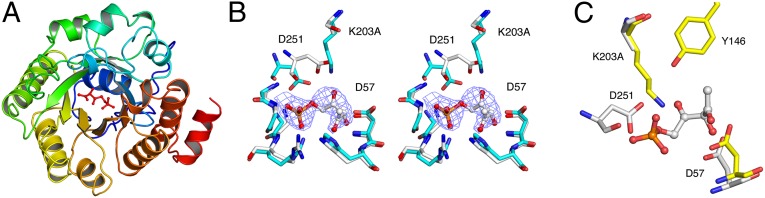

We previously determined the crystal structure of LsrF and showed that it is a decamer, arranged with two pentameric disks stacked on each other (27). Each monomer has the very common (αβ)8-barrel fold seen in many protein families, including class I aldolases, with fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase (FBPA) from Thermoproteus tenax (31) being the most closely related structure. Class I aldolases are defined by the presence of a catalytically essential Schiff base-forming lysine, and structural alignments of LsrF with T. tenax FBPA and other class I aldolases showed structural conservation of the catalytic lysine with LsrF K203 (27). To test this lysine for a role in catalysis, we expressed and purified the K203A LsrF mutant and measured its activity in vitro with P-AI-2 and CoASH. We detected no activity in this mutant, a strong indication that K203 is catalytically essential (Table S2).

We grew crystals of the catalytically inactive LsrF mutant K203A in the presence of P-AI-2, LsrG (which rapidly converts P-AI-2 to P-HPD/P-TPO), and CoASH. The resulting structure (Fig. 5A and Table S4) shows nonprotein electron density in the putative active site (Fig. 5B). Based on the LsrG-dependence of the LsrF reaction, the ligand density was modeled as P-HPD. To reduce bias, the position of the ligand was determined by the LigandFit module of Phenix (32). The density allowed definitive placement of the phosphate group, well-positioned to form hydrogen bonds with a number of structurally conserved residues, and clearly illustrated the path of the carbon chain (Fig. 5B). No obvious density corresponding to CoASH was observed, although a 10-fold noncrystallographic symmetry averaged map shows a small amount of excess density extending from the end of P-HPD toward the solvent, the expected location for CoASH.

Fig. 5.

Structure of LsrF K203A in complex with P-HPD. (A) Cartoon representation of a single LsrF subunit with the bound substrate (P-HPD) shown as ball and stick. The monomer has the ubiquitous (α/β)8-barrel subunit, and the fold and substrate position are the same as in class I aldolases. (B) Stereoview of the LsrF K203A (white) active site superposed with WT LsrF (Blue, PDB ID code 3GKF). Also shown is the P-HPD model and electron density. (C) Comparison of LsrF K203A (white) and T. tenax FBPA (yellow) active sites with P-HPD shown. Structural alignments of entire LsrF and T. tenax FBPA monomers were calculated in Coot.

Comparison of the ligand-bound K203A LsrF to the unliganded WT structure revealed only one substantial change, a shift in the position of D251 (Fig. 5B). In the P-HPD–bound mutant structure, D251 moves toward the position occupied by K203 in the unliganded WT structure, with the γ-carbon moving 2.9 Å. We interpreted this shift to be a consequence of ligand binding rather than a shift into the space created by the K203A mutation because a similar, although less-pronounced, shift is seen in WT LsrF bound to the P-AI-2 mimics ribose-5-phosphate and ribulose-5-phosphate with, in these cases, the γ-carbons moving 1.7 Å and 2.5 Å, respectively (27). This ligand-dependent positional shift, coupled with proximity to the Schiff base-forming lysine, suggested a catalytic role for this residue, so we tested the activity of a D251A mutant. As with the K203A, no activity was detected with our in vitro assay with purified D251A mutant protein (Table S2).

The structure also showed that residue D57 is positioned close enough to the P-HPD chain to play a role in catalysis (Fig. 5B). This residue is structurally conserved in class I aldolases [e.g., rabbit muscle and T. tenax FBPA (Fig. 5C)], where it acts as general base facilitating the C–C cleavage. Activity assays with a D57A mutant showed that this mutant was indeed catalytically inactive in LsrF (Table S2). The positioning of the K203, D251, and D57 in proximity to P-HPD, and the observation that alanine mutants of these residues are inactive, supports their role in catalysis. These results allow us to propose a mechanism for the LsrF-catalyzed transfer of an acetyl group to CoASH (see below), which uses the same mechanistic tropes as class I aldolases to catalyze a thiolytic cleavage that, to our knowledge, has not previously been observed with these enzymes.

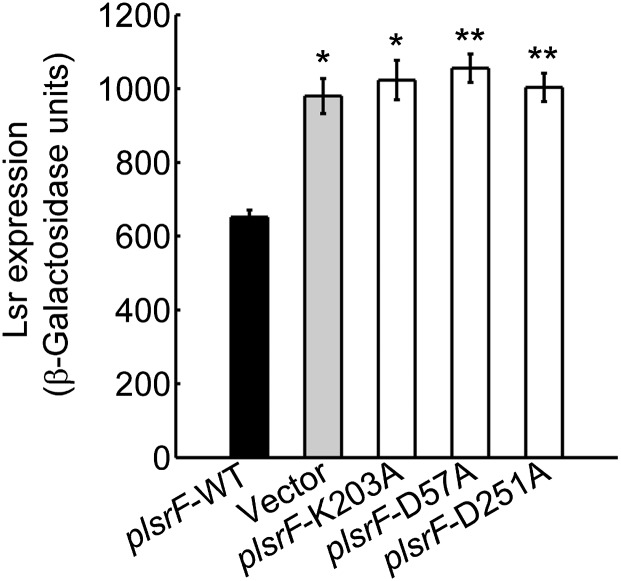

Activity of LsrF Mutants in Vivo.

To determine if the three residues identified above (D57, K203, and D251) play a functional role in vivo, alanine substitution mutants were expressed in multicopy plasmids and tested in the lsr-lacZ reporter E. coli assay. The results showed that these single-residue substitution mutants were unable to complement the lsrF deletion mutant (Fig. 6), and thus that K203, D57, and D251 are essential for LsrF activity in vivo. This finding supports the proposal that LsrF acts in the pathway that degrades AI-2 via a mechanism analogous to that of class I aldolases. In summary, our results show that mutants in the residues K203 and D57, which are structurally conserved with the catalytic mutants in the other aldolases, and D251, which is not conserved but shifts in response to ligand binding and is positioned adjacent to K203, are inactive in vitro and functionally impaired in vivo.

Fig. 6.

In vivo effect of vector-borne LsrF-WT and mutants on the expression of the lsr operon. β-galactosidase activity of the lsr-lacZ transcription reporter fusion was measured in ΔlsrF strains carrying ptrc99a with WT lsrF (plsrF-WT, black bar), empty vector (vector, gray bar), and lsrF single amino acid substitutions mutants K203A, D57A, and D251A (white bars). Cells were collected when cultures reached Abs600 = 4 (5 h postinoculation, consistent with that time point in Fig. 2). The error bars indicate SDs (Mann–Whitney test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, n = 6).

Discussion

The lsr operon, which is strongly up-regulated in response to high levels of environmental AI-2, has been shown to encode proteins involved in recognizing AI-2, transporting it into the cell, and quenching the response by processing the signal molecule. We have previously characterized the role of LsrK and LsrG in this process: catalysis of the phosphorylation of AI-2 and subsequent isomerization of P-AI-2 to an equilibrium mixture of P-HPD and its hydrated form P-TPO. Here, we show that LsrF catalyzes the transfer of an acetyl group from the P-AI-2 isomer produced by LsrG to CoASH, yielding DHAP and acetyl-CoA. This result was surprising; based on strong structural homology between LsrF and class I aldolases, we had expected LsrF to cleave a C–C bond on a phosphorylated substrate rather than catalyze an acetyl transfer between two substrates. The structure of a catalytically inactive LsrF mutant (K203A) in complex with its substrate showed strong ligand electron density in, essentially, the same position as the ligand in T. tenax FBPA, the closest structural homolog to LsrF. The strong structural homology between LsrF and FBPA, coupled with in vitro and in vivo assays identifying catalytically impaired mutants, suggests a mechanism for this process in which LsrF acts as a thiolase, an activity not previously seen for class I aldolase-like enzymes.

In the canonical FBPA reaction, the catalytic lysine attacks carbonyl C2 of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate forming a covalent intermediate. Subsequently, a proton is donated to the carbinolamine, facilitating dehydration and formation of the Schiff base. The residue that donates the proton differs between species; in most aldolases it is a glutamate adjacent to the lysine, but in T. tenax and other archaea the proton donor is a tyrosine (31, 33). A proton is then removed from the hydroxyl on C4 by an aspartic acid, leading to cleavage of the C3–C4 bond and release of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate. The remaining product, DHAP, is subsequently released by hydrolysis of the Schiff base (33). Thus, there are three key catalytic residues in FBPA, and the crystal structure of the LsrF/ligand complex allowed us to identify the functionally equivalent residues in LsrF.

Comparison of the ligand-bound LsrF K203A structure with the structure of a catalytically inactive, ligand-bound T. tenax FBPA mutant (Y146F) shows that carbonyl C4 of P-HPD occupies a very similar location to carbonyl C2 in fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (the position of Schiff base formation), indicating that it is well-positioned for attack by the structurally conserved catalytic lysine (K203) and supporting the proposal that LsrF will form a Schiff base with P-HPD. Although neither the Tyr nor the Glu that act as an acid in the dehydration of the carbinolamine (in T. tenax and rabbit muscle, respectively) are conserved in LsrF, an Asp (251) is well positioned to act as the acid, as it is less than 3 Å from the catalytic lysine [although on the other side of the lysine than the acidic glutamate in some FPBAs (Fig. 5 B and C)]. D251 shifts by 1–3 Å in response to ligand binding, and in vivo and in vitro assays showed that the D251A mutant is catalytically inactive (Fig. 6 and Table S2). The final key catalytic residue in the FBPA mechanism, the Asp responsible for removing the proton from the C4 oxygen of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate and thus initiating bond cleavage, is structurally conserved in LsrF (D57). Our data show that a D57A mutant is inactive, consistent with a catalytic role for this aspartate.

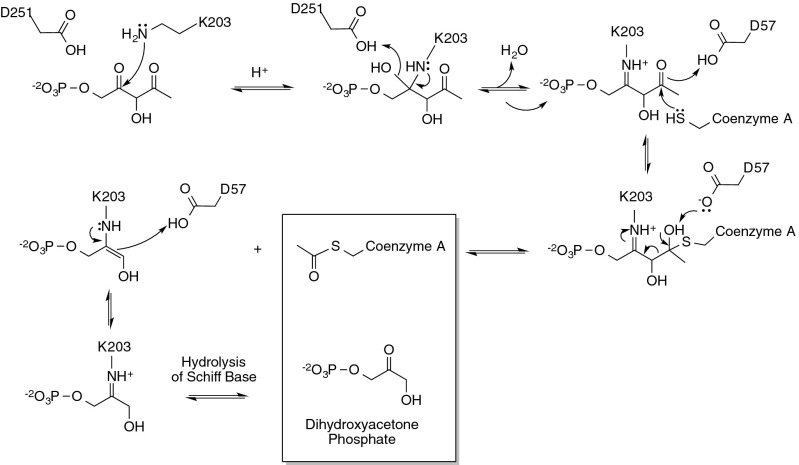

Based on the identification and characterization of these catalytic residues, we propose a mechanism for the LsrF-catalyzed reaction (Fig. 7), in which K203 forms a Schiff base by attacking the C4 keto-group on the P-AI-2 isomer P-HPD produced by LsrG. This keto group is adjacent to the carbon bearing the phosphate, just as in the FBPA mechanism, and the crystal structure shows that P-HPD C4 is well positioned to interact with K203. D251 then plays the role of an acid in the dehydration of the carbinolamine leading to Schiff base formation. Subsequently, the thiol of CoASH attacks the carbonyl carbon at C2, resulting in either an intermediate in which the oxygen at C2 is protonated to a hydroxyl by D57 or, potentially, a transient tetrahedral intermediate. In a canonical class I aldolase reaction this carbon would have a hydroxyl rather than a carbonyl, but the nucleophilic attack of the thiol would be expected to be more favorable at the carbon of a carbonyl group. D57 then withdraws a proton from the oxygen, leading to the reformation of the carbonyl group and cleavage of the C2–C3 bond in a step analogous to the bond-breaking step in an aldolase, with the Schiff base playing an essential catalytic role via an enamine. Acetyl-CoA is thus released, leaving DHAP bound to LsrF (the same covalently bound product as in the FBPA reaction). Finally, DHAP is released by hydrolysis of the Schiff base, with LsrF restored to its initial state. Thus, we propose that using the same catalytic “tricks” as a class I aldolase, LsrF effectively works as a thiolase, catalyzing the cleavage of a carbon–carbon bond (C2–C3) in P-HPD by attack of the sulfur group of CoASH.

Fig. 7.

Mechanism of LsrF-catalyzed acylation of CoASH. Catalysis is initiated by the attack of LsrF K203 on the keto-group at C4 of P-HPD and subsequent formation of a Schiff base. Nucleophilic attack of the thiol of CoASH at C2 follows, resulting in either a transient tetrahedral intermediate or (as shown) a longer-lived intermediate in which the oxygen at C2 is protonated. D57 then acts as a base, withdrawing a proton from the hydroxyl at C2, leading to cleavage of the C2–C3 bond and formation of an enamine. Acetyl-CoA is released, leaving DHAP bound to LsrF until it is released by hydrolysis of the Schiff base.

The requirement for the P-AI-2 isomerization catalyzed by LsrG (Fig. 1) is consistent with the Schiff base-type mechanism proposed here: in class I aldolases bond cleavage occurs one position removed from the site of the Schiff base formation (C4 here, with bond cleavage between C3 and C2). Because P-AI-2 has a carbonyl on C3 rather than C4, the LsrG-catalyzed isomerization to P-HPD is needed to correctly position the carbonyl for the reaction to proceed. For this same reason, we conclude that P-HPD, rather than P-TPO [which has two hydroxyl groups at C4 and thus could not form the Schiff base (Fig. 1)], is the substrate for the LsrF reaction. It is possible that LsrF could also act on other phosphorylated substrates; certainly LsrK has been shown to act on synthetic AI-2 analogs (28, 34, 35). Future work should involve studies of LsrG as well, as it plays a crucial role in generating the arrangement of carbonyls required for LsrF catalysis.

Overall, our results led to the conclusion that AI-2 is ultimately processed to DHAP and acetyl-CoA, metabolites used by the bacterium in key pathways associated with central metabolism (glycolysis and the citric acid cycle) (Fig. 1). Coupled with previous studies, our results show that the lsr operon encodes the proteins necessary for recognizing and transporting AI-2 and for converting the internalized signal into common metabolites. Although these results complete the characterization of the processing of AI-2 by the lsr operon in E. coli, they open up many questions about the interplay between AI-2–mediated quorum sensing and metabolism. Most directly, it raises the possibility that E. coli could use AI-2 as a sole carbon source by metabolizing the DHAP and acetyl-CoA produced by the LsrF reaction. To test this theory, we grew E. coli in minimal media with AI-2, glucose, or ribose. The bacteria were able to grow robustly with glucose or ribose (like AI-2, a five carbon compound) but relatively poorly with AI-2 [the growth rate on AI-2 was six- and fourfold lower than glucose and ribose, respectively (Fig. S3)]. This result is likely because of an imbalance in the CoA/acetyl-CoA ratio created by the LsrF catalyzed reaction; similar growth inhibition has been observed in several E. coli mutants as a result of oversupply of acetyl-CoA (36, 37). Nonetheless, our results suggest that E. coli can gain a metabolic benefit from metabolizing AI-2 and that LsrF-mediated processing of AI-2 influences cellular levels of acetyl-CoA and thus metabolic flux in cells.

The other metabolite produced by the LsrF reaction, DHAP, may mediate an additional connection between quorum sensing and metabolism. It has been shown that E. coli mutants that accumulate DHAP have reduced levels of lsr transcription (12). In this way, LsrF and LsrG act to control lsr transcription not only by reducing levels of P-AI-2 (thus increasing lsr repression via LsrR) but also by catalyzing the formation of a metabolite that inhibits lsr transcription. Thus, AI-2 processing is sensitive to flux through DHAP while at the same time contributing to the cellular pool of DHAP available for central metabolism. Additional studies on how DHAP and acetyl-CoA concentrations and metabolic fluxes change in response to AI-2 levels will be necessary, but our results provide evidence for a previously unidentified connection between AI-2 and metabolic flux. Thus, processing of AI-2 by LsrF and LsrG could act as both a natural mechanism for quenching AI-2–mediated signaling and a means to impact central metabolism in response to community conditions. This finding opens the door to future work studying the response and regulation of these responses, particularly in mixed-species environments.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Growth Conditions.

All strains and plasmids used are listed in Table S5. These strains are all E. coli MG1655 derivatives of KX1123 (ΔlacZYA, lsr-lacZ) (12). The ΔlsrF::Cm and ΔlsrFG::Cm mutants were constructed by replacing the lsrF and lsrFG genes in KX1123 by a chloramphenicol (Cm) resistance cassette using the red swap protocol (38). Antibiotic resistance cassettes were removed using the FLP recombinase expressing plasmid pcp20, as described previously (38). Except where otherwise stated, strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with 100 mM of Mops, pH 7, at 37 °C with shaking. Growth was monitored by optical density at 600 nm (Abs600).

In Vivo Expression of Transcription of the lsr Operon.

In vivo expression of the lsr operon was determined by measuring the β-galactosidase activity of the lsr-lacZ promoter fusion, as previously described (12, 25). β-Galactosidase units are defined as (Abs420 min−1 × dilution factor × 104)/(Abs600). Strains containing the pTrc99a plasmid and derivatives were cultured in LB medium with ampicillin (100 mg/L) and IPTG (1 μg/L), added 2.5 h postinoculation.

NMR Analysis.

Unless otherwise stated, all spectra were acquired on a Bruker AVANCE II 500 spectrometer (Bruker) at a proton operating frequency of 500.43 MHz, equipped with a 5-mm broadband inverse detection probe head using standard Bruker pulse programs (see SI Materials and Methods for details).

AI-2 and P-AI-2 and P-TPO/P-HPD Synthesis.

AI-2 was synthesized and prepared as previously reported (25, 39). P-AI-2 was produced enzymatically by the phosphorylation of AI-2 by LsrK as previously described (25). The products of LsrG (P-TPO and P-HPD) were produced enzymatically by incubating 10 µg/mL of LsrG with 4 mM of P-AI-2 at room temperature for 2 min (25). Because of instability, P-TPO/P-HPD was produced in situ before use. Quantitative 1H-NMR was used to determine the final concentration of AI-2, P-AI-2, and P-TPO/P-HPD.

LsrF in Vitro NMR Assays.

To identify potential substrates of LsrF we tested different combinations of AI-2 analogs (AI-2, P-AI-2, P-TPO/P-HPD and ribulose-5-phosphate) (2–3 mM) with an array of E. coli metabolites and cofactors (3–5 mM) (Table S1). To identify the products of the LsrF the reaction mixture containing enzymatically prepared P-TPO/P-HPD (1.5 mM/0.5 mM) and 2.5 mM of CoASH was incubated with 60 µg/mL of purified LsrF at 30 °C; 4 min were sufficient to ensure the complete consumption of P-TPO/P-HPD. The identity of the products was confirmed by adding 6 mM of acetyl-CoA and DHAP (Sigma). The substrates and products were quantified by 1H NMR before and after spiking with synthetic standards.

Statistical Analysis.

For comparison of two independent groups, significance of difference was tested with the Mann–Whitney test corrected for multiple comparisons. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistic Toolbox (MathWorks). Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05. In all figures, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Measurement of LsrF Activity.

Initial velocity measurements were performed in a 96-well plate on a Nicolet Evolution 300 spectrophotometer (Thermo Industries) plate reader using a continuous assay at 30 °C. The production of DHAP by LsrF was coupled to the oxidation of NADH catalyzed by GPDHase using a method similar to ref. 28 (see SI Materials and Methods for details).

Protein Production, Crystallization, and Structure Determination.

LsrF and all mutants were expressed and purified using the His6-MBP-LsrF fusion procedure as described previously (27). Crystals were grown via the hanging-drop method with a well solution of 21% (wt/vol) PEG 400, 110 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, and 100 mM Tris pH 8.0. The drop consisted of 1 μL K203A LsrF (7.3 mg/mL), 1 μL well solution, and 1 μL LsrG reaction mix (5 mM CoASH, ∼1 mM P-AI-2, and 10 μg/mL LsrG). LsrG was prepared as described previously (25). Crystals were soaked in 100 mM Tris pH 8.0, 25 mM MgCl2, 27.5% (wt/vol) PEG 400 for 4 min, and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Data (Table S4) were collected at 100K at the National Synchrotron Light Source X29 beamline, processed using XDS (40) and CCP4 (41), and the structure determined via molecular replacement using PHENIX (32). The structure was built using Coot (42), refined using PHENIX and REFMAC (43), and has been deposited in the PDB under ID code 4P2V.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Judith Voet (Swarthmore College), Joshua Rabinowitz and Frederick Hughson (both from Princeton University), and Ligia Martins and Helena Santos (both from Instituto de Tecnologia Química e Biológica) for helpful discussion and suggestions; Jessica Thompson and Pol Nadal for critically reading the manuscript; Joana Amaro (Instituto de Gulbenkian de Ciência) for technical assistance; and the staff of the National Synchrotron Light Source X29 beamline for assistance with X-ray data collection. This work was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (PTDC/QUI-BIQ/113880/2009); the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (International Early Career Scientist grant, HHMI 55007436); and the National Institutes of Health (Grant R15GM096478-01A1). The NMR spectrometers are part of The National NMR Facility, supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (RECI/BBB-BQB/0230/2012).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 4P2V).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1408691111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rutherford ST, Bassler BL. Bacterial quorum sensing: Its role in virulence and possibilities for its control. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(11):pii a012427. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuqua WC, Winans SC, Greenberg EP. Quorum sensing in bacteria: The LuxR-LuxI family of cell density-responsive transcriptional regulators. J Bacteriol. 1994;176(2):269–275. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.2.269-275.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LaSarre B, Federle MJ. Exploiting quorum sensing to confuse bacterial pathogens. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013;77(1):73–111. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00046-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong YH, Wang LY, Zhang LH. Quorum-quenching microbial infections: Mechanisms and implications. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007;362(1483):1201–1211. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ng WL, Bassler BL. Bacterial quorum-sensing network architectures. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:197–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowery CA, Dickerson TJ, Janda KD. Interspecies and interkingdom communication mediated by bacterial quorum sensing. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37(7):1337–1346. doi: 10.1039/b702781h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Surette MG, Miller MB, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing in Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, and Vibrio harveyi: A new family of genes responsible for autoinducer production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(4):1639–1644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, et al. Structural identification of a bacterial quorum-sensing signal containing boron. Nature. 2002;415(6871):545–549. doi: 10.1038/415545a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira CS, Thompson JA, Xavier KB. AI-2–mediated signalling in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37(2):156–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xavier KB, Bassler BL. Interference with AI-2-mediated bacterial cell-cell communication. Nature. 2005b;437(7059):750–753. doi: 10.1038/nature03960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taga ME, Semmelhack JL, Bassler BL. The LuxS-dependent autoinducer AI-2 controls the expression of an ABC transporter that functions in AI-2 uptake in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42(3):777–793. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xavier KB, Bassler BL. Regulation of uptake and processing of the quorum-sensing autoinducer AI-2 in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2005a;187(1):238–248. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.1.238-248.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller ST, et al. Salmonella typhimurium recognizes a chemically distinct form of the bacterial quorum-sensing signal AI-2. Mol Cell. 2004;15(5):677–687. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pereira CS, McAuley JR, Taga ME, Xavier KB, Miller ST. Sinorhizobium meliloti, a bacterium lacking the autoinducer-2 (AI-2) synthase, responds to AI-2 supplied by other bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 2008;70(5):1223–1235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06477.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereira CS, de Regt AK, Brito PH, Miller ST, Xavier KB. Identification of functional LsrB-like autoinducer-2 receptors. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(22):6975–6987. doi: 10.1128/JB.00976-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torres-Escobar A, Juárez-Rodríguez MD, Demuth DR. Differential transcriptional regulation of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans lsrACDBFG and lsrRK operons by integration host factor protein. J Bacteriol. 2014;196(8):1597–1607. doi: 10.1128/JB.00006-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roy V, Fernandes R, Tsao CY, Bentley WE. Cross species quorum quenching using a native AI-2 processing enzyme. ACS Chem Biol. 2010a;5(2):223–232. doi: 10.1021/cb9002738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xavier KB, et al. Phosphorylation and processing of the quorum-sensing molecule autoinducer-2 in enteric bacteria. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2(2):128–136. doi: 10.1021/cb600444h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pereira CS, et al. Phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system regulates detection and processing of the quorum sensing signal autoinducer-2. Mol Microbiol. 2012;84(1):93–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L, Hashimoto Y, Tsao CY, Valdes JJ, Bentley WE. Cyclic AMP (cAMP) and cAMP receptor protein influence both synthesis and uptake of extracellular autoinducer 2 in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2005a;187(6):2066–2076. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.6.2066-2076.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L, Li J, March JC, Valdes JJ, Bentley WE. luxS-dependent gene regulation in Escherichia coli K-12 revealed by genomic expression profiling. J Bacteriol. 2005b;187(24):8350–8360. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.24.8350-8360.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xue T, Zhao L, Sun H, Zhou X, Sun B. LsrR-binding site recognition and regulatory characteristics in Escherichia coli AI-2 quorum sensing. Cell Res. 2009;19(11):1258–1268. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu M, Tao Y, Liu X, Zang J. Structural basis for phosphorylated autoinducer-2 modulation of the oligomerization state of the global transcription regulator LsrR from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(22):15878–15887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.417634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ha JH, et al. Crystal structures of the LsrR proteins complexed with phospho-AI-2 and two signal-interrupting analogues reveal distinct mechanisms for ligand recognition. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(41):15526–15535. doi: 10.1021/ja407068v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marques JC, et al. Processing the interspecies quorum-sensing signal autoinducer-2 (AI-2): Characterization of phospho-(S)-4,5-dihydroxy-2,3-pentanedione isomerization by LsrG protein. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(20):18331–18343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.230227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taga ME, Miller ST, Bassler BL. Lsr-mediated transport and processing of AI-2 in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50(4):1411–1427. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diaz Z, Xavier KB, Miller ST. The crystal structure of the Escherichia coli autoinducer-2 processing protein LsrF. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(8):e6820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu J, Hixon MS, Globisch D, Kaufmann GF, Janda KD. Mechanistic insights into the LsrK kinase required for autoinducer-2 quorum sensing activation. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(21):7827–7830. doi: 10.1021/ja4024989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spiess AN, Neumeyer N. An evaluation of R2 as an inadequate measure for nonlinear models in pharmacological and biochemical research: A Monte Carlo approach. BMC Pharmacol. 2010;10:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bennett BD, et al. Absolute metabolite concentrations and implied enzyme active site occupancy in Escherichia coli. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5(8):593–599. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorentzen E, Siebers B, Hensel R, Pohl E. Mechanism of the Schiff base forming fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase: Structural analysis of reaction intermediates. Biochemistry. 2005;44(11):4222–4229. doi: 10.1021/bi048192o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi KH, Shi J, Hopkins CE, Tolan DR, Allen KN. Snapshots of catalysis: The structure of fructose-1,6-(bis)phosphate aldolase covalently bound to the substrate dihydroxyacetone phosphate. Biochemistry. 2001;40(46):13868–13875. doi: 10.1021/bi0114877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roy V, et al. Synthetic analogs tailor native AI-2 signaling across bacterial species. J Am Chem Soc. 2010b;132(32):11141–11150. doi: 10.1021/ja102587w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gamby S, et al. Altering the communication networks of multispecies microbial systems using a diverse toolbox of AI-2 analogues. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7(6):1023–1030. doi: 10.1021/cb200524y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.El-Mansi M, Cozzone AJ, Shiloach J, Eikmanns BJ. Control of carbon flux through enzymes of central and intermediary metabolism during growth of Escherichia coli on acetate. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9(2):173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolfe AJ. The acetate switch. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69(1):12–50. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.1.12-50.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(12):6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ascenso OS, et al. An efficient synthesis of the precursor of AI-2, the signalling molecule for inter-species quorum sensing. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19(3):1236–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67(Pt 4):235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 4):486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53(Pt 3):240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.