Fire and conversation are two things that have been of crucial importance for our evolutionary story, yet they have received only rather casual attention. Yes, we know that fire was used for cooking (probably casually at first, but later as a matter of regularity), and, yes, we know that language evolved at some point and has been important for human culture. However, there has been a longstanding tendency to take these two phenomena for granted as something self-evidently useful and hence presumably of ancient origin. In PNAS, Wiessner (1) brings these two phenomena together in a way that has significant implications for our understanding of both why they evolved and when they did so. In the first such study of its kind, she recorded the topics of conversation during the day and around the campfire at night among a group of Ju’/hoansi (or !Kung) Bushman in Botswana, a people whose living hunter-gatherer ecology is similar to that which characterized most of our evolutionary history. In this sample, most daytime conversations were functional (discussions of land rights, economic matters, norm regulation), but most evening conversations were social (more than 80% were stories). Stories are important in all societies because they provide the framework that holds the community together: we share this a set of cultural knowledge because we are who we are, and that is why we are different from the folks that live over the hill.

The longstanding assumption, dating back at least a century, has been to assume that language evolved to facilitate the transmission of technical knowledge (“this is how you make an arrowhead”), a view that has been generalized more recently to encompass the social transmission of cultural knowledge (again, mainly with a directly ecological purpose) (2, 3). An alternative view has been that language evolved, at least in the first instance, to facilitate community bonding (to allow more effective communal solutions to ecological problems) (4). Similarly, control of fire has often been assumed to have been driven by ecology and the need to cook food to render it more digestible (5) or to keep warm at night. These were largely unrelated phenomena, connected only by virtue of being part of the grand scheme of human culture.

In fact, Wiessner’s data suggest that fire and language may be more closely related than conventional views assume. Whatever may have been the original reason why humans acquired control over fire, it seems that it came to play a central role in two crucial respects. First, it effectively extended the active day (6). Monkeys and apes are forced to be inactive at night because their relatively poor nighttime vision renders them (and us) especially susceptible to predators at night (all of the major predators of terrestrial primates, including humans, are nocturnal) (7–9). Fire potentially allowed us to remain active into the evening, thus adding as much as 4 h to the working day. Second, it provided a venue in which social interaction, and pretty much only social interaction, could take place. Those extra evening hours could not be used for foraging, and the lighting isn’t that good for making tools; although the evening can be used for cooking and eating, these only take up the whole evening on very special occasions (feasts). There is considerable “empty” time that can only be devoted to conversation (dyadic bonding) and storytelling (communal bonding) or other social bonding activities such as singing and dancing (10).

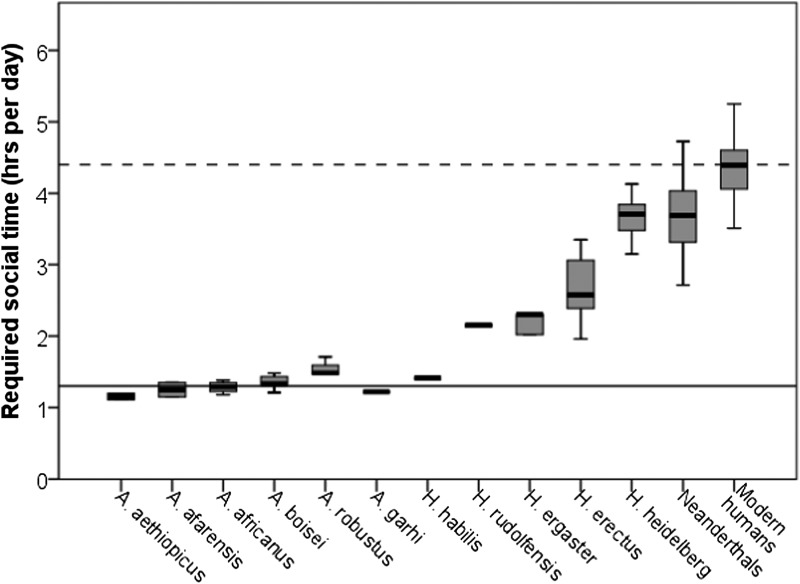

The scale of the problem faced by later Homo is illustrated in Fig. 1. This plots the number of hours of social time required to bond the social groups of different hominin species, given a 12-h tropical day. The estimates are based on a generic equation linking required social time to group size for monkeys and apes (11) and group sizes predicted by their cranial volumes using the generic social brain equation for apes (4, 12). The increase in social time is purely a reflection of each taxon’s increasing community size, as predicted by its brain size. A time budget model for australopithecines that takes their value into consideration along with predicted requirements for feeding, moving, and resting given their habitat-specific climatic parameters (13) shows that their time budgets were at their limit in all habitats (i.e., they had no spare capacity to devote to increases in social time), so the difference between australopithecine social time requirements (Fig. 1: on average 1.3 h, solid line) and that for fossil anatomically modern humans (AMHs; 4.4 h, dashed line) represents the time budget deficit that later hominins were under if they were to maintain coherent social groups of the size predicted by their brains and still balance their time budgets during a 12-h day. The difference for early Homo is modest and likely easily achievable by savings elsewhere. However, those for archaic Homo (2.3 h/d) and AMH (3.1 h/d) are too large. The only way they could possibly have coped is by extending day length into the evening. Increasing the length of the active day by 2–3 h would have instantly solved their time budget crisis.

Fig. 1.

Median (±50% and 95% ranges) required social time for individual hominin species. Required social time is determined from a generic equation for monkeys and apes relating grooming time to group size (10), with group (i.e., community) size for hominins calculated from mean population cranial capacity (16) using the ape regression equation relating social group size to neocortex volume (4, 17). A population is defined as all of the fossils at a particular location dated to within a 50,000-y time span. Neanderthal community sizes are corrected to take account of the effect of latitude on their visual system, following ref. 18. “Modern humans” refers to fossil populations of anatomically modern humans. A, australopithecines; H, Homo.

However, it is all very well having extra time: the issue is what you do with it. Social interaction is unique among the elements of a time budget in being the one thing you can do at night. [Resting time demand is driven by daytime temperatures and heat load (14), so using the evening to absorb a heavy resting time demand is not an option.] Shifting one’s social bonding time to the evening frees off the whole of the day for foraging, thereby greatly increasing the time available for food-finding. Language provides the perfect medium because speech can be heard across the hearth, or even the whole camp, without necessarily being able to see the speaker. The popular suggestion that language evolved from some form of gesture-based communication

Wiessner's data suggest that fire and language may be more closely related than conventional views assume.

(3) would be much less practical: for gestural conversations, you need to be able to see the speaker face to face, and the lighting from fires is both imperfect and very limited in its range. Audiences for stories would of necessity be tiny. With speech, a single storyteller can hold court with a lecture hall even in dim lighting.

Wiessner’s findings contribute directly to this debate in three important respects. First, she shows that social conversations (those essentially about community building as opposed to more immediate practical concerns) are almost entirely confined to the evening hours. Ju’/hoansi conversations around the campfire contain little information about the environment or matters of economic relevance. This is compelling evidence as to why language and hearths might have coevolved, thereby neatly filling the gap that has been overlooked for so long. Second, her analysis of story content reveals that these often involve accounts of neighbors or religious experiences, stories of the ancestors, myths and folktales—just the kinds of topics that create a sense of community and bind individuals into a functional social group (15). One significant feature of such stories was accounts of travel to distant exchange partners, allowing other band members to learn about the extended community on the tribal scale whom one is otherwise likely to meet only very occasionally. Such information becomes crucial in knowing how to deal with, and more importantly whether or not to trust, the strangers one meets. Third, and most intriguingly, it provides direct evidence for the importance of charismatic storytellers—those skilled in the art of entertainment—as core foci around whom community bonding revolves.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 14027.

References

- 1.Wiessner PW. Embers of society: Firelight talk among the Ju/'hoansi Bushmen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:14027–14035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404212111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Schaik CP, Isler K, Burkart JM. Explaining brain size variation: From social to cultural brain. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16(5):277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomasello M. Origins of Human Communication. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunbar RIM. Coevolution of neocortex size, group size and language in humans. Behav Brain Sci. 1993;16(4):681–735. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gowlett JAJ, Wrangham RW. Earliest fire in Africa: Towards convergence of archaeological evidence and the cooking hypothesis. Azania. 2013;48(1):5–30. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunbar RIM, Gowlett JAJ. Fireside chat: The impact of fire on hominin socioecology. In: Dunbar RIM, Gamble C, Gowlett JAJ, editors. Lucy to Language: The Benchmark Papers. Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ Press; 2014. pp. 277–296. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cowlishaw G. Vulnerability to predation in baboon populations. Behaviour. 1994;131(3-4):293–304. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shultz S, Noë R, McGraw WS, Dunbar RIM. A community-level evaluation of the impact of prey behavioural and ecological characteristics on predator diet composition. Proc R Soc Biol Sci. 2004;271(1540):725–732. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehmann J, Dunbar RIM. Implications of body mass and predation for ape social system and biogeographical distribution. Oikos. 2009;118(3):379–390. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunbar RIM, Kaskatis K, MacDonald I, Barra V. Performance of music elevates pain threshold and positive affect: Implications for the evolutionary function of music. Evol Psychol. 2012;10(4):688–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehmann J, Korstjens A, Dunbar R. Group size, grooming and social cohesion in primates. Anim Behav. 2007;74(6):1617–1629. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dunbar (2011) Evolutionary basis of the social brain. Oxford Handbook of Social Neuroscience, eds Decety J, Cacioppo J (Oxford Univ Press, Oxford, UK), pp 28–38.

- 13.Bettridge CM. 2010. Reconstructing Australopithecine socioecology using strategic modelling based on modern primates. DPhil thesis (Univ of Oxford, Oxford, UK)

- 14.Korstjens A, Lehmann J, Dunbar RIM. Resting time as an ecological constraint on primate biogeography. Anim Behav. 2010;79(2):361–374. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunbar RIM. Mind the gap: Or why humans aren’t just great apes. Proc Br Acad. 2008;154:403–423. [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Miguel C, Henneberg M. Variation in hominid brain size: How much is due to method? Homo. 2001;52(1):3–58. doi: 10.1078/0018-442x-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gowlett JAJ, Gamble C, Dunbar RIM. Human evolution and the archaeology of the social brain. Curr Anthropol. 2012;53(6):693–722. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pearce E, Stringer C, Dunbar RIM. New insights into differences in brain organisation between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans. Proc R Soc Lond. 2013;280B:1471–1481. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]