Abstract

Objective

Palliative care is recognized as an important component of oncologic care. We sought to assess the quality/quantity of palliative care education in gynecologic oncology fellowship.

Methods

A self-administered on-line questionnaire was distributed to current gynecologic oncology fellow and candidate members during the 2013 academic year. Descriptive statistics, bivariate and multivariate analyses were performed.

Results

Of 201 fellow and candidate members, 74.1% (n = 149) responded. Respondents were primarily women (75%) and white (76%). Only 11% of respondents participated in a palliative care rotation. Respondents rated the overall quality of teaching received on management of ovarian cancer significantly higher than management of patients at end of life (EOL), independent of level of training (8.25 vs. 6.23; p < 0.0005). Forty-six percent reported never being observed discussing transition of care from curative to palliative with a patient, and 56% never received feedback about technique regarding discussions on EOL care. When asked to recall their most recent patient who had died, 83% reported enrollment in hospice within 4 weeks of death. Fellows reporting higher quality EOL education were significantly more likely to feel prepared to care for patients at EOL (p < 0.0005). Mean ranking of preparedness increased with the number of times a fellow reported discussing changing goals from curative to palliative and the number of times he/she received feedback from an attending (p < 0.0005).

Conclusions

Gynecologic oncology fellow/candidate members reported insufficient palliative care education. Those respondents reporting higher quality EOL training felt more prepared to care for dying patients and to address complications commonly encountered in this setting.

Keywords: Palliative care, Education, End of life care, Gynecologic cancer, Hospice, Fellowship training

Introduction

In 2013, there were an estimated 91,000 cases of gynecologic cancer in the United States, with slightly over 28,000 deaths [1]. These statistics trail only those for lung, breast and colon cancer amongst women. Despite continued advances in surgical management and adjuvant therapy, disease progression and recurrence continue to plague women suffering from ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancer [2]. Therefore, palliative care is an integral component of practice.

Following publication of the landmark trial in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer, the importance of palliative care on quality and quantity of life in the non-curable setting became evident [3]. Palliative care services focus on symptom management, psychosocial support and assistance with decision-making. Currently, the Accreditation Counsel of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires that oncology fellowship training programs include education regarding pain assessment and management, psychosocial care, and knowledge of hospice [4]. Despite the importance of palliative care, hematology oncology fellows reported palliative care training to be inferior to overall oncology training [5]. Furthermore, despite giving bad news to patients on average 35 times per month, oncologists reported little training on giving patients information regarding prognosis [6,7].

Over the past two decades significant inroads have been made into the molecular cascades that govern carcinogenesis and tumor progression. In addition, the introduction of molecularly targeted therapy for the treatment of many solid tumors has transformed the therapeutic landscape in oncology. Unfortunately, this progress has not been matched with a similar availability of efficacious supportive care interventions designed to relieve debilitating symptoms due to treatment-related adverse events and disease progression. The introduction of palliative care services at the time of diagnosis of advanced cancer has been shown to result in meaningful improvement in the experiences of patients and caregivers by not only emphasizing symptom management and quality of life, but also treatment planning.

Within the specialty of gynecologic oncology, the symptom burden for patients with advanced disease is extensive, and includes pain, nausea, intestinal obstruction, ascites, constipation, nausea/emesis, anorexia, diarrhea, dyspnea and hypercalcemia [8]. Gynecologic oncologists have an obligation to care for such women at the end of life (EOL), and should understand appropriate symptom management, developing basic knowledge pertaining to EOL care. Importantly, failure to understand and address issues surrounding EOL has been shown to result in unnecessary medical interventions, and hospital admissions [9].

To date, limited data exist describing palliative care education during gynecologic oncology fellowship training. Prior investigators have reported a lack of comfort and knowledge with EOL counseling, care and hospice referral and timing [9]. More recently, Lesnock et al. reported that the quantity and quality of training in palliative care were lower compared to other common procedural and oncological issues [10]. The objective of this study was to determine the self-assessed adequacy of palliative care training in gynecologic oncology amongst senior fellows as well as junior faculty, in order to better understand preparedness for EOL care and perceptions regarding palliative care education.

Methods

Survey design

Following institutional review board approval, a validated survey was distributed using Survey Monkey® online software. The self-administered, 103-item on-line questionnaire was distributed to current gynecologic oncology fellow and candidate members of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO), during the 2013 academic year. The survey was adapted from prior hematology–oncology research, and focused on 7 domains in end-of-life (EOL) training [11]. The domains included 1) respondent characteristics, 2) quality and quantity of teaching, 3) curriculum, 4) observation and feedback, 5) end-of-life clinical practice, 6) self rated preparation and 7) attitudes. Additional details are provided in Table 1. Approval for use of the survey tool was obtained from MB [11]. Modifications were made to allow for the comparison of palliative care and non-palliative care topics specific to gynecologic oncology. In this article, we assessed gynecologic oncology fellow and junior faculty perceptions regarding palliative care training/education as well as preparedness to care for patients at the end of life. A copy of the instrument is available on request.

Table 1.

Domains of survey on gynecologic oncology fellow training in end of life adapted from Buss et al.

| Respondent characteristics | Eleven questions about demographics, respondent characteristics, and career plans |

| Quality & quantity of teaching | Four items on quantity of oncology and EOL education, as well as quality of teaching in fellowship |

| Curriculum | Eight items on explicit teaching, six items on implicit messages conveyed by faculty and other fellows |

| Observation & feedback | Three items; fellows reported the number of times they performed, observed, and received feedback on EOL topics (discussing goals of care) |

| EOL clinical practice | Fifteen items regarding the care respondent provided for their patient who died most recently |

| Self rated preparation | Thirteen items regarding respondent’s preparation with respect to specific tasks related to EOL |

| Attitudes | Nine items assessing respondent’s and faculty attitudes toward providing EOL care |

Sample

The survey was electronically distributed to Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) fellow-in-training members and candidate members (defined as having completed an American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ABOG) approved fellowship program in gynecologic oncology). The decision to include fellow and candidate members was made in an effort to enrich the number of senior fellows and junior faculty with adequate clinical exposure/experience.

The SGO is a 1600 member medical specialty, whose mission is to provide and improve the care of women with gynecologic cancers by encouraging research, dissemination of knowledge, improving standards of practice and professional collaboration. A total of 189 candidate members and 219 fellow-in-training members were identified.

In order to incentivize participation, respondents were compensated with a twenty-dollar Amazon gift card. This study was generously supported by a grant from the Foundation for Gynecologic Oncology Research Institute. The available funds necessitated limitation of the total sample size to approximately 200 respondents. In total, 230 sequential individuals were selected from a list provided by the SGO, 150 fellows-in-training and 80 candidate members. Ten subjects were excluded as they lived outside of the United States, and 19 e-mail addresses were invalid.

In July 2013, eligible subjects received an e-mail with a link to the online survey. Non-respondents received up to 3 additional reminder e-mails in 1–2 week intervals, with completion of recruitment in September 2013. Information regarding individual programs was not collected and all data was anonymously recorded.

Statistical assessment

Descriptive analysis was conducted for all responses. All returned surveys, including those with incomplete responses, were included in the analysis. Statistical tests were evaluated at the 2-sided 0.05 level of significance. Responses on end-of-life (EOL) topics were compared with responses on general gynecologic oncology topics using chisquare or Fisher exact tests for dichotomous variables. Analysis of continuous variables was performed using Student t test when the data was normally distributed, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for data with non-normal distribution. Demographic characteristics including sex, race, age, marital status, and religiosity were collected. All analysis was conducted using Stata V11.2 (Stata Corp., College station, Texas).

Results

Respondent characteristics

We received a total of 149 responses (74.1% response rate), all of which were electronically submitted. Table 2 displays the respondents’ characteristics. Median age was 34 years (range 29–36), and approximately 75% were female. The majority of respondents were white (75.5%), of Christian faith (55.9%) and married or living with a partner (77.6%). Importantly, 85% (n = 126) of respondents were in their second year or greater of fellowship training, suggesting clinical exposure and experience in end-of-life care and counseling.

Table 2.

Patient demographics.

| Characteristic | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age (range) | 34 (29–36) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 36 (25.2) |

| Female | 107 (74.8) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 108 (75.5) |

| Asian | 21 (14.7) |

| Black or African American | 6 (4.2) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 7 (4.9) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 (0.7) |

| Other | 8 (5.6) |

| Religion | |

| Christian | 80 (55.9) |

| Muslim | 2 (1.4) |

| Hindu | 1 (0.7) |

| Jewish | 10 (7.0) |

| Budhist | 1 (0.7) |

| Other | 5 (3.5) |

| Not religious | 44 (30.8) |

| Importance of religious beliefs | |

| Very | 51 (35.7) |

| Somewhat | 29 (20.3) |

| A little | 33 (23.0) |

| Not at all | 30 (21.0) |

| Year of fellowship | |

| 1 | 25 (27.8) |

| 2 | 33 (36.7) |

| 3 | 27 (30.0) |

| 4 | 5 (5.6) |

| Year post-fellowship | |

| 0–1 | 37 (60.7) |

| 2–3 | 21 (34.4) |

| >3 | 3 (4.9) |

| Marital status | |

| Single/never married | 28 (19.6) |

| Married/living with partner | 111 (77.6) |

| Divorced/separated | 4 (2.8) |

| Type of career planned | |

| Basic science | 1 (0.7) |

| Academic patient care | 116 (81.1) |

| Clinical research | 5 (3.5) |

| Community patient care | 21 (14.7) |

| Palliative care rotation | |

| Mandatory | 16 (11.2) |

| Elective | 0 (0.0) |

| None | 127 (88.8) |

| Access to a palliative care specialty during fellowship | |

| Yes | 130 (90.9) |

| No | 13 (9.1) |

Quality and quantity of teaching

Ninety-seven percent of respondents indicated that learning how to provide care for dying patients was important to very important in their clinical education, while only 34% reported that EOL education was very important to their attending physicians.

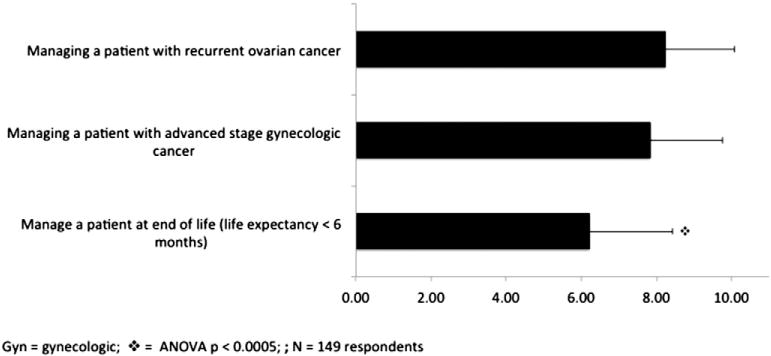

On 3 items designed to compare the nature of gynecologic oncology cancer care teaching to end-of-life education, respondents reported inferior teaching in EOL care (Fig. 1). Specifically, on a 10-point Likert scale (1 = no teaching and 10 = a lot of teaching), fellows-in-training and candidate members reported a mean ± standard deviation (SD) of 8.25 ± 1.8 for managing a patient with recurrent ovarian cancer, 7.85 ± 1.9 for managing a patient with advanced stage gynecologic cancer, and 6.23 ± 2.2 for managing a patient at end-of life (life expectancy less than 6 months). The amount of EOL education was significantly less than education regarding management of advanced stage gynecologic cancers in general and the management of recurrent ovarian cancer (P < 0.0005). Importantly, this difference did not vary by level of training.

Fig. 1.

Fellow and Junior faculty evaluation of education regarding EOL care and complex gynecologic cancer scenarios. Likert scale (1 = no teaching; 10 = extensive teaching).

Additionally respondents were asked to rate their gynecologic oncology attending physicians on their ability to discuss side effects of chemotherapy with patients, discuss the decision to stop chemotherapy and focus on QOL, and manage pain in terminally ill patients. Using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = poor and 5 = excellent), respondents indicated a significantly superior ability to address chemotherapy side effects when compared to transition of care at EOL, and pain management (P < 0.0005). Conversely, when specifically queried regarding quality of teaching as it pertained to discussion of code status, hospice care referral, and transition of care from treatment to comfort, 60% of respondents reported adequate to superior education.

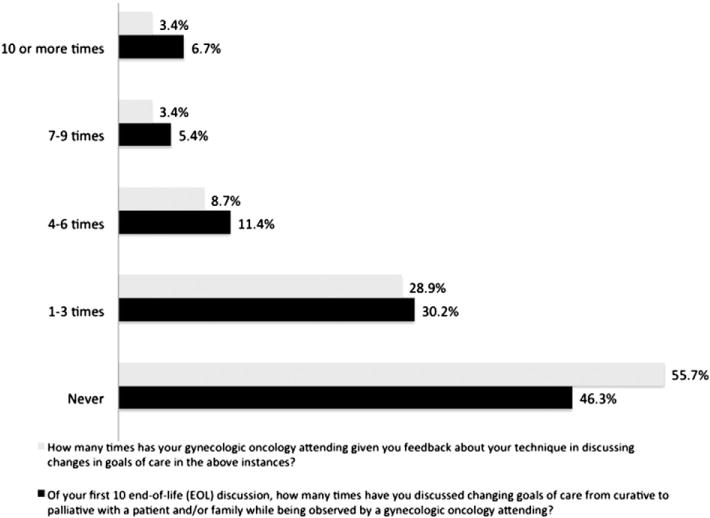

Perceptions regarding direct observation and feedback between fellows and their attending physicians were evaluated in order to assess the importance of communication on palliative care and EOL education. Fifty-six percent of respondents reported never receiving feedback about technique in discussing changing goals of care, while 46% reported never being observed by an attending in their first 10 EOL conversations focused on transition of care from treatment to comfort (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Reported observation and feedback specific to end-of life discussions. Scale indicates the number of end-of-life conversations per respondent.

Additionally, respondents were queried regarding EOL education with respect to pain management, psychosocial care and communication skills (supplementary Table 1). Only 19.7% of fellows received direct education on when to rotate opioids, while 27.2% reported education on how to assess and treat neuropathic vs. visceral pain. Importantly, only 15% were explicitly taught how to manage depression in patients at end of life. Conversely, the majority of respondents reported receiving explicit education on how to determine when to refer patients to hospice (50.3%) and discussing the decision to stop chemotherapy (57.1%).

End-of-life care and hospice referral

Both current fellows-in-training and candidate SGO members were questioned regarding assessment and management of common EOL symptoms. Fewer than 50% of respondents reported assessing delirium, depression and discussing bereavement needs with family and friends. Conversely, over 97% assessed and managed pain.

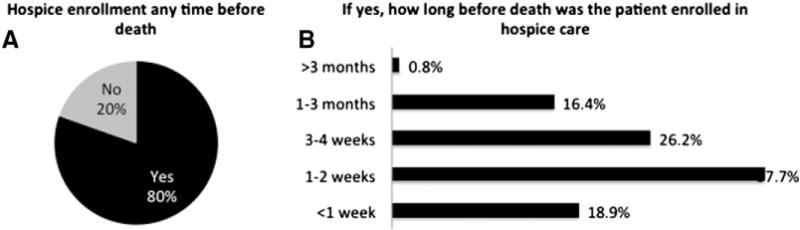

In order to understand patterns of hospice referral, utilization and timing of hospice enrollment were assessed. Of 148 respondents, 80% indicated that their patients were enrolled in hospice prior to death. Nearly 57% reported enrollment within 2 weeks of death, while 82.8% reported patient enrollment in hospice 1 month prior to death (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Recalling the most recent patient death, respondents were asked about hospice enrollment and time of enrollment before death. A) Percent of patients enrolled in hospice any time before death; B) time interval before death that the patient was enrolled in hospice.

Preparedness

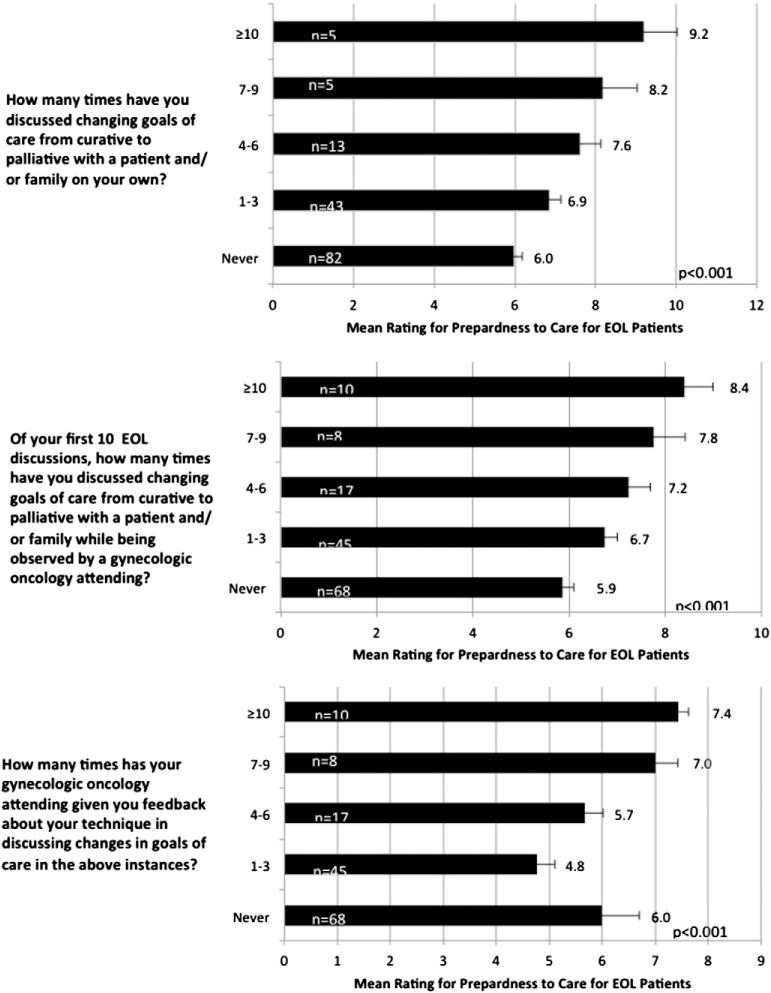

Fellow-in-training and candidate members were questioned regarding the management of common EOL symptoms. The majority of respondents felt moderately well prepared in the management of pain, family member bereavement, as well as dyspnea and hypercalcemia. Conversely, respondents reported being very well prepared in the management of nausea, vomiting, intestinal obstruction and ascites. Higher overall preparedness in the care of patients at EOL was strongly associated with the number of discussions regarding transition of goals of care, attending observation of discussion as well as direct feedback/education (P < 0.0005; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Association between preparedness and experience/education.

Discussion

Among the surgical subspecialists in the field of oncology, gynecologic oncologists are unique in that they typically perform surgery and administer multiple lines of chemotherapy over time. Patients with ovarian, uterine and cervical cancers begin their journey with their gynecologic oncologists, who remain actively involved with end-of-life issues and terminal care when appropriate. Accordingly, many feel that incorporating palliative care in the management of patients with advanced stage gynecologic cancers is implicit, and its integration in fellow education is essential. The principles of palliative care, focusing on medical, emotional and spiritual needs, have been shown to result in improvements in patient reported QOL and mood [3,12].

In this study, gynecologic oncology fellows-in-training and candidate members expressed a strong interest in EOL care and palliative care education, while reporting a lack of attending led teaching. Notably, the majority of respondents never received feedback regarding technique in discussing goals of care. The reason for this lack of communication is unclear, and may be related to conflicting obligations and lack of direct observation, as many of these discussions occur at the time of hospitalization [13].

Alternatively, the belief may exist that conversations regarding goals of care and EOL education occur in conjunction with a palliative care service, and the gynecologic oncology attending might defer feedback to the specialists. This hypothesis may be supported by the fact that approximately 90% of respondents indicated access to a palliative care specialty during fellowship. Furthermore, respondents reported an associated perception that attending physicians were better at discussing chemotherapy side effects as compared to pain, and transitions in goals of care.

The above findings are not unique to gynecologic oncology [10]. In the fields of medical oncology and nephrology, deficiencies in EOL education have been identified [11,14]. Given the high mortality rate of end-stage renal disease, second year nephrology fellows were surveyed regarding the quality and quantity of teaching they received in palliative medicine. Only 22% reported being taught how to tell a patient he or she was dying [14]. In a larger population of medical oncology fellows, overall quality of teaching was rated more highly than palliative care teaching [11,15].

In addition to palliative care, hospice has been identified as a valuable resource in the management of patients at EOL. Experts recommend at least a three-month hospice stay in order for both patients and families to derive adequate benefit from hospice services [9,16]. In our study, nearly 83% of respondents reported enrolling their patients in hospice within one month of death, and 19% within one week. This is consistent with prior publications in gynecologic oncology, showing a median time between hospice enrollment and death of 22 days [9]. The reasons behind delayed enrollment are undoubtedly multi factorial, and related to both physician and patient based factors [17].

It is important to note, however, that education and clinical experience can impact preparedness for EOL care. There was a significant improvement in self-reported preparedness with an increase in EOL discussions as well as attending observation/feedback. These findings support the institution of a palliative care based competency assessment during fellowship training. Ensuring both sufficient volume and documenting performance based on established guidelines may help ensure that graduating fellows are ready to manage the complexities of symptom palliation and EOL care [18]. As a component of the above, direct communication between trainees and their faculty mentors should be required. Alternatively, a mandatory in-patient or ambulatory palliative care rotation can be integrated into existing gynecologic oncology fellowship programs. Exposure to experts in palliative care medicine will result in a more comprehensive experience, and may work to transition the responsibility away from gynecologic oncology attending faculty who have competing obligations.

Assessment of palliative care training during fellowship is difficult, and like all survey based studies there are limitations. The survey was distributed to a limited number of fellow and candidate members, in a sequential fashion, based on the funds available to incentivize response. This may have inadvertently biased responses, by incompletely sampling the population. The anonymity of this survey prevented us from collecting institutional data, and the presence of palliative care curriculum at existing ABOG approved fellowships could not be assessed. Additionally, the data represent subjective assessments related to palliative care and EOL education, and are susceptible to recall bias [19]. Conversely, the large sample size, and above average response rate (74.1%) increase the likelihood that the sample was an adequate representation of the target population. Furthermore, inclusion of both fellows-in-training and candidate SGO members helped ensure adequate clinical exposure and experience. Lastly, the survey was conducted and completed in 2013, allowing for a contemporary assessment of palliative care training in gynecologic oncology.

The purpose of this study was to document the subjective experiences of palliative care education during gynecologic oncology fellowship training throughout the United States. This was done to start a dialogue on whether the integration of palliative care into training is necessary, and more importantly, feasible. Our study demonstrates that gynecologic oncology fellows and candidate members reported their palliative care education during fellowship training to be insufficient. Those respondents reporting higher quality EOL training felt significantly more prepared to care for dying patients and to address complications commonly encountered in this setting. Incorporation of a comprehensive palliative care curriculum in fellowship may better equip trainees to care for patients at EOL.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Palliative care education/training is perceived as inadequate during fellowship.

Over 80% of patients are referred to hospice within 4 weeks of death.

With increased experience/feedback respondents reported greater comfort in EOL care.

Incorporation of a palliative care curriculum in fellowship may better equip trainees to care for patients at EOL.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.05.021.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no real or potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rezk Y, Timmins PF, III, Smith HS. Review article: palliative care in gynecologic oncology. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2011;28:356–74. doi: 10.1177/1049909110392204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weissman DE, Block SD. ACGME requirements for end-of-life training in selected residency and fellowship programs: a status report. Acad Med. 2002;77:299–304. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200204000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buss MK, Lessen DS, Sullivan AM, Von Roenn J, Arnold RM, Block SD. Hematology/oncology fellows’ training in palliative care: results of a national survey. Cancer. 2011;5:237–42. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baile WF, Kudelka AP, Beale EA, Glober GA, Myers EG, Greisinger AJ, et al. Communication skills training in oncology. Description and preliminary outcomes of workshops on breaking bad news and managing patient reactions to illness. Cancer. 1999;86:887–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baile WF, Glober GA, Lenzi R, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. Discussing disease progression and end-of-life decisions. Oncology. 1999;13:1021–31. [(Williston Park) discussion 1031–6] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rezk Y, Timmins PF, III, Smith HS. Palliative care in gynecologic oncology. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;28:356–74. doi: 10.1177/1049909110392204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fauci J, Schneider K, Walters C, Boone J, Whitworth J, Killian E, et al. The utilization of palliative care in gynecologic oncology patients near the end of life. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:175–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lesnock JL, Arnold RM, Meyn LA, Buss MK, Quimper M, Krivak TC, et al. Palliative care education in gynecologic oncology: a survey of the fellows. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130:431–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buss MK, Lessen DS, Sullivan AM, Von Roenn J, Arnold RM, Block SD. Hematology/oncology fellows’ training in palliative care: results of a national survey. Cancer. 2011;117:4304–11. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Balan S, Brokaw FC, Seville J, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stiefel F, Barth J, Bensing J, Fallowfield L, Jost L, Razavi D, et al. Communication skills training in oncology: a position paper based on a consensus meeting among European experts in 2009. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:204–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holley JL, Carmody SS, Moss AH, Sullivan AM, Cohen LM, Block SD, et al. The need for end-of-life care training in nephrology: national survey results of nephrology fellows. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:813–20. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00868-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan CX, Carmody S, Leipzig RM, Granieri E, Sullivan A, Block SD, et al. There is hope for the future: national survey results reveal that geriatric medicine fellows are well-educated in end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:705–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ. Impact of individual and market factors on the timing of initiation of hospice terminal care. Med Care. 2000;38:528–41. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200005000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keyser EA, Reed BG, Lowery WJ, Sundborg MJ, Winter WE, III, Ward JA, et al. Hospice enrollment for terminally ill patients with gynecologic malignancies: impact on outcomes and interventions. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;118:274–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Gunten CF, Lupu D. Recognizing palliative medicine as a subspecialty: what does it mean for oncology? J Support Oncol. 2004;2:166–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:1094–102. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.